Abstract

Hispanic patients receive disproportionately fewer living donor kidney transplants (LDKTs) than non-Hispanic Whites (NHW). The Northwestern Medicine Hispanic Kidney Transplant Program (HKTP), designed to increase Hispanic LDKTs, was evaluated as a non-randomized, implementation-effectiveness hybrid trial of patients initiating transplant evaluation at two intervention and two similar control sites. Using a mixed method, observational design, we evaluated the fidelity of the HKTP implementation at the two intervention sites. We tested the impact of the HKTP intervention by evaluating the likelihood of receiving LDKT comparing pre-intervention (1/2011–12/2016) and post-intervention (1/2017–3/2020), across ethnicity and centers. The HKTP study included 2,063 recipients. Intervention Site A exhibited greater implementation fidelity than intervention Site B. For Hispanic recipients at Site A, the likelihood of receiving LDKTs was significantly higher at post-intervention compared to pre-intervention [odds ratio (OR)=3.17 95% confidence interval (1.04, 9.63)], but not at the paired control Site C [OR=1.02 (0.61, 1.71)]. For Hispanic recipients at Site B, the likelihood of receiving a LDKT did not differ between pre- and post-intervention [OR=0.88 (0.40, 1.94)]. The LDKT rate was significantly lower for Hispanics at paired control Site D [OR=0.45 (0.28, 0.90)]. The intervention significantly improved LDKT rates for Hispanic patients at the intervention site that implemented the intervention with greater fidelity.

Registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov registered (retrospectively) on 9–7-17 (NCT03276390).

1. Introduction

Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) because it confers longer patient and graft survival, shorter waiting time, better quality of life than deceased donor kidney transplantation (DDKT) or maintenance hemodialysis, and saves society costs.1–3 However, Hispanics are disproportionately less likely to receive LDKTs than non-Hispanic whites (NHW).4–6 Waitlisted Hispanics received fewer LDKTs than waitlisted NHWs in 2019: 5.0% versus 12.2%.7 Given that this disparity has increased over time,8 and Hispanics are the second largest and second fastest growing minority group in the US,9, 10 reducing LDKT disparities is critically important for increasing equity in care.

LDKT disparities can be attributed to patient, provider, and system-level factors.4 Patient-level factors amongst Hispanics include lack of LDKT knowledge, religious concerns, and cultural concerns about fertility and disability post-donation, financial challenges, and distrust of healthcare providers.11–13 Provider-level factors include discordance of ethnic/racial backgrounds with patients, and Spanish language proficiency. System-level factors include lack of culturally competent transplant education and interpreter availability.14

The prominence of sociocultural factors contributing to LDKT disparities necessitates culturally targeted interventions.11, 15, 16 Culturally targeted interventions aim to reduce LDKT disparities by embracing “A set of values, principles, behaviors, attitudes, policies, and structures that enable organizations and individuals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.”17 Most culturally targeted interventions intervene at the patient-level by improving patient and family knowledge and/or attitudes about LDKT using culturally targeted messaging,18–21 and have targeted predominantly Black19, 20 rather than Hispanic patient populations.18, 21 Few interventions designed to increase LDKT access have intervened at the system levels.22, 23 Interventions across multiple levels are needed to comprehensively redress disparities.

Moreover, few LDKT interventions have evaluated their implementation. However, we identified the barriers and facilitators to the pre-implementation of a multi-level culturally targeted LDKT intervention.14 Implementation evaluation is valuable for understanding why interventions did (not) achieve desired effects.24, 25 Interpretation of treatment effects depends on assessments of intervention fidelity (i.e., the extent to which an intervention is delivered as intended).26 Thus, intervention fidelity increases internal validity because outcomes can be confidently attributed to the intervention, or, non-significant results can be attributed to either an ineffective intervention or a poorly implemented intervention.27

Northwestern Medicine’s™ (NM) Hispanic Kidney Transplant Program (HKTP) delivers complex, multi-level, culturally and linguistically competent and congruent care to Hispanic patients with chronic kidney disease initiating kidney transplant evaluation and their families with the intent of increasing referral to the transplant center, and access to transplantation, particularly LDKT rates.28 The HKTP was associated with a 91% increase in waitlist additions, and a 74% and 62% increase in the number of Hispanic LDKTs and DDKTs, respectively, performed from 2008–2013 compared to 2001–2006. The mean ratio of Hispanic to NHW LDKTs (disparity metric) significantly increased after implementation of the HKTP by 70% (p=0.001).28

The present hybrid study aimed to prospectively evaluate the effectiveness of the HKTP intervention in reducing disparities in LDKT among Hispanics in comparison to NHWs.

Because of the intervention’s multilevel effects, we evaluated the effects on individuals who participated directly and on the center overall. We also prospectively evaluated the implementation fidelity at each intervention site given the HKTP’s complexity.29 We hypothesized that after implementing the HKTP, the ratio of Hispanic to NHW LDKTs would significantly increase, when implemented with fidelity.

2. Methods

2.1. Intervention

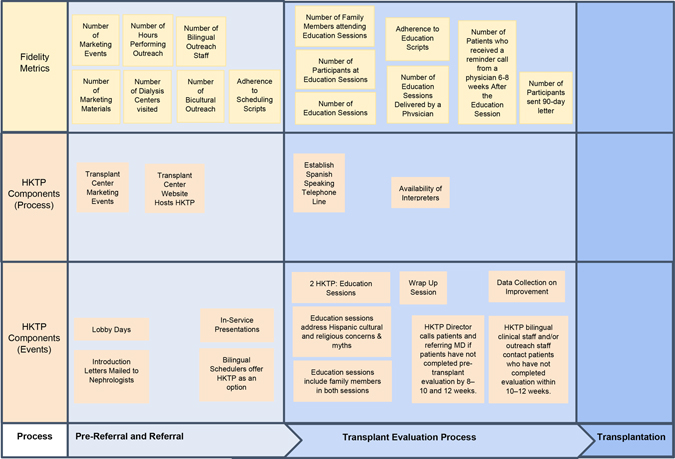

The NM HKTP uses a culturally competent care delivery process involving 16 components, while providing the same standard of care to all patients undergoing transplant evaluation, as described elsewhere.28, 30 As a complex intervention, the HKTP involves many interrelated components, people, and organizational levels.29 Supporting File 1 describes HKTP’s development, components, and modifications. Figure 1 illustrates how the HKTP components serve to funnel patients through the HKTP. While some HKTP intervention components could have a direct effect at the study participant level (e.g., dialysis outreach, culturally targeted education, physician follow-up with referring nephrologists), other components could have a broader effect at the center level (e.g., marketing). Thus, HKTP-driven process changes could have influenced Hispanics beyond those participating directly, which warranted evaluation at both levels.

Figure 1.

HKTP Components and Fidelity Metrics along the Transplant Evaluation Continuum

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted at four actively recruited transplant centers. The HKTP was implemented at two centers that had a Hispanic bilingual transplant physician, LDKT volume >50 per year to accommodate an increase in LDKTs, and served large Hispanic populations (Site A: South, Site B: Southwest). Two control sites were deliberately selected and paired with intervention sites based on comparable county population size, Hispanic proportion of the county population, LDKT volumes, and availability of a bilingual Hispanic transplant physician (Site C: South, Site D: Southwest); eligible sites were identified in a prior analysis.28 Control sites were selected in different counties to avoid contamination. Both control sites had bilingual staff.

2.3. Study Design

Our study entailed a prospective, non-randomized, implementation-effectiveness hybrid trial31 with pre-post intervention sites and a similar set of control sites from 1/1/2011 to 3/15/2020. We conducted process evaluation to explain why the intervention failed or succeeded at the intervention sites.29 The pre-intervention “retrospective” period spanned 1/1/2011–12/31/2016; the intervention “prospective” period spanned 1/1/2017–3/15/2020, and ended early due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We used a mixed-methods complementary design whereby descriptive process data were used to interpret quantitative study outcomes.32 Institutional Review Boards (IRB) approved the study (Northwestern University STU00201331, Mayo Clinic: #16–002328, Houston Methodist: #Pro00014678, Colorado: #16–0962, Baylor: #016–115). The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03276390). We used the Consort 2010 checklist for quality and transparent trial reporting.33 We used the Template for Intervention Description and Replication for quality reporting.34

2.4. Data Sources

2.4.1. Fidelity measures:

To evaluate HKTP implementation fidelity, as an a priori objective, intervention sites’ research staff: a) audio-recorded quarterly scheduler phone calls with patients and HKTP education sessions to document the core content areas covered, and type of clinician, b) documented the outreach staff’s bilingual and bicultural status, c) documented the number of dialysis centers visited and the hours spent on outreach, d) documented whether each potential recipient received a call post education and was sent a reminder letter to complete transplant evaluation, e) documented the number of marketing materials and events promoting the HKTP (Figure 1). All scheduler recordings were de-identified, and NU staff used checklists to evaluate adherence (yes/no) to HKTP protocol components.

2.4.2. Patient level data:

Patient-level data were obtained from medical chart review, and from de-identified, aggregated patient-level data from the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network/United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS). Data from study sites were collected and managed using REDCap, a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, hosted at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.35 Data collected from medical chart review included: demographics (i.e., age, gender, race/ethnicity), clinical characteristics (i.e., kidney disease etiology, comorbidities), date of transplant evaluation, and date and type of kidney transplantation [LDKT/DDKT].

2.5. Participants and Recruitment

2.5.1. Study participants:

Eligible participants included adult (age 18+ years) self-identified (prospective) or medical record-identified (retrospective) Hispanic and NHW patients who initiated transplant evaluation and/or underwent re-evaluation for a kidney transplant (KT) and received a KT between 1/1/2011 and 3/15/2020. It was assumed that all patients initiating transplant evaluation had the intent, at least initially, of getting a DDKT. It was unknown at that time whether patients were interested in pursuing LDKT or had identified a willing living donor. During the prospective period, intervention sites’ scheduling staff offered Hispanic patients the choice of attending the HKTP (in Spanish) or the routine clinic (in English). Hispanic patients participating in the HKTP were included in the study. Hispanics at intervention sites who did not attend the HKTP were not recruited into the study. All Hispanic patients were included at intervention sites in the retrospective period and at control sites in both retrospective and prospective periods. Across all sites and periods, we randomly selected an equivalent number of NHWs to minimize research staff workload. We originally established the equivalent numbers needed for the random sample of NHWs based on the number of Hispanic patients initiating transplant evaluation in 2016 at each site. During the prospective period, Hispanic patients attending the HKTP clinic and NHW patients attending the routine clinic were recruited in person and provided written consent. The IRBs granted a waiver of informed consent at control sites in the prospective period and across all sites in the retrospective period.

2.5.2. OPTN/UNOS data:

Eligible participants included all adult Hispanic and NHW participants who received a kidney transplant between January 2011 and March 2020 at all four sites, regardless of whether Hispanic patients had attended the HKTP at intervention sites.

2.6. Outcome Measures

Likelihood of Receiving LDKTs among Transplant Recipients (patient level):

We compared the change in likelihood of Hispanic transplant recipients receiving LDKT to change in likelihood of NHW transplant recipients receiving LDKT, which provides evidence that any Hispanic increase was not at the expense of NHW patients.

Ratio of Hispanic to NHW Transplant Recipients Receiving LDKTs among Transplant Recipients (center level):

Using 6-month intervals, we computed the ratio of Hispanic LDKT rate to NHW LDKT rate, where LDKT rate is the number of LKDTs over total number of KTs. This ratio takes into account growth in transplant center volume while providing a comparison to NHWs, necessary for assessing disparities in LDKT.36 The ratio provides an index of whether the Hispanic LDKT increase grew over and above the increase observed at a center overall, and accounts for factors related to the center’s infrastructure and capacity to perform additional LDKTs that affect Hispanics and NHWs equally. Institutional commitments to LDKT, which can influence willingness to donate or preferences for LDKT37 and affect both populations equally (e.g., paired donation, and desensitization efforts), were accounted for.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

Due to the complex nature of the intervention, we tested the impact of the intervention on two levels: 1) the effect on Hispanics who participated in the HKTP education using Redcap data, and 2) the effect on all Hispanics post-intervention (an overall center effect) using UNOS data. To measure the effect of participating in the HKTP on Hispanic recipients receiving a LDKT, multivariable logistic regression models with three-way interaction terms (pre- versus post-HKTP, Hispanics versus NHWs, intervention site versus control site) were performed using patient-level REDCap data. That is, our comparisons were performed in the same model as a difference in difference in difference analysis to control for potential biases within a non-randomized RCT. Comparisons were interpreted at the: time level (e.g., Hispanics pre-intervention (control group) versus Hispanics post-intervention (exposed group)); patient level by time (e.g., Hispanics (pre-intervention versus post-intervention) versus Non-Hispanic Whites (pre-intervention versus post-intervention; control group); and center level (e.g., Site A versus Site C, and Site B versus Site D)). Because this study is an implementation-effectiveness hybrid trial, we performed patient-level analyses separately at each pair of intervention and control sites.

The model included binary variables for post intervention (versus pre), Hispanic (versus NHW), intervention (versus control) and two-way (post-versus pre-intervention and Hispanic versus NHW) and three-way (post-versus pre-intervention, Hispanic versus NHW, and intervention versus control) interaction terms to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of receiving a LDKT among transplant recipients comparing post- and pre-intervention period for Hispanics and NHWs by intervention and control sites. The post- versus pre-intervention ORs greater than 1 indicated a higher likelihood of receiving a LDKT among transplant recipients in the post-intervention period compared to the pre-intervention period for Hispanics and NHWs in each intervention and control site. A set of demographic and clinical variables in Table 1, selected based on clinical experience and factors influencing patients’ receipt of LDKT,38–42 were considered as covariates.

Table 1a.

Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Whitea HKTP Study Participants’ Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics by Intervention Site A and Control Site C, n=836

| Characteristicb | Intervention Site A, n=280 |

Control Site C, n=556 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic, n=118 | Non-Hispanic White, n=162 | Hispanic, N=250 | Non-Hispanic White, n=306 | |

| Agec, years, mean ± SDd (range) | 46.01 ± 14.22 (18–75) | 52.97 ± 12.69 (18–76) | 48.14 ± 13.75 (19–80) | 53.76 ± 13.49 (21–81) |

|

| ||||

| Sex, Male, n (%) | 71 (60.17) | 97 (59.88) | 170 (68.00) | 230 (75.16) |

|

| ||||

| Marital status, Married/with Partner, n (%) | 72 (61.02) | 121 (74.69) | 295 (59.84) | 377 (68.55) |

|

| ||||

| Highest Education Level, College degree and above, n (%) | 7 (7.61) | 55 (48.24) | 30 (12.45) | 137 (49.00) |

|

| ||||

| Primary Insurance Coverage, Private, n (%) | 31 (31.00) | 42 (35.90) | 89 (35.89) | 169 (55.96) |

|

| ||||

| Body Mass Indexc, kg/m 2, mean ± SD^ (range) | 28.54±5.60 (16.80–42.86) | 28.38±5.63 (16.98–54.14) | 27.68±5.09 (16.70–53.90) | 27.06±5.13 (14.38–49.03) |

|

| ||||

| History of Hypertension, n (%) | 101 (90.18) | 134 (84.28) | 240 (96.00) | 296 (96.73) |

|

| ||||

| History of Diabetes, n (%) | 55 (47.83) | 65 (40.63) | 104 (41.60) | 83 (27.12) |

|

| ||||

| Primary cause of ESRDe, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 50 (42.37) | 51 (31.48) | 93 (37.20) | 62 (20.26) |

| Hypertension | 30 (25.42) | 24 (14.81) | 47 (18.80) | 33 (10.78) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 13 (11.02) | 25 (15.43) | 19 (7.60) | 54 (17.65) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 3 (2.54) | 21 (12.96) | 10 (4.00) | 46 (15.03) |

| lga nephropathy | 2 (1.69) | 9 (5.56) | 8 (3.20) | 20 (6.54) |

| Tubular and Intersititial | 3 (2.54) | 12 (7.41) | 9 (3.60) | 20 (6.54) |

| Other | 13 (11.02) | 17 (10.49) | 53 (21.20) | 63 (20.59) |

| Unknown | 4 (3.39) | 3 (1.85) | 11 (4.40) | 8 (2.61) |

|

| ||||

| On dialysisf, n (%) | 96 (82.05) | 81 (50.00) | 178 (71.20) | 122 (39.87) |

|

| ||||

| Waiting time (days), median [IQR] (range) | 321 [728] (1–1946) | 319 [744] (0–2827) | 411 [940] (4–3050) | 272 [534] (0–2870) |

|

| ||||

| Number of prior transplants, n (%) | ||||

| 0 transplant | 98 (87.50) | 143 (89.94) | 227 (90.80) | 269 (87.91) |

| 1 transplant | 11(9.82) | 14 (8.81) | 20 (8.00) | 31 (10.13) |

| 2+ transplants | 3 (2.68) | 2 (1.26) | 3 (1.20) | 6 (1.96) |

All study participants in pre-HKTP (Jan 2011- Dec 2016) and post-HKTP (Jan 2017 – Mar 2020). In intervention sites, only participants attending the HKTP are included.

At start of evaluation except age, body mass index (kg/m2), and waiting time (days).

At the time of transplant.

SD = Standard Deviation.

Other includes re-transplantation, congenital kidney disease, and lupus.

At the time of starting transplant evaluation.

To measure center level effects of the intervention, interrupted time series (ITS) with segmented regression analyses were used to evaluate the ratio of Hispanic LDKT rate to NHW LDKT rate in 6-month intervals for each center from 6 years prior to 3.25 years after HKTP implementation using UNOS/OPTN data. (See details in Supporting File 1).

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was conducted to ascertain the likelihood that changes in the volume of LDKTs at study sites were attributable to HKTP implementation. See details in Supporting File 1.

All analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.1.1. HKTP Study Data

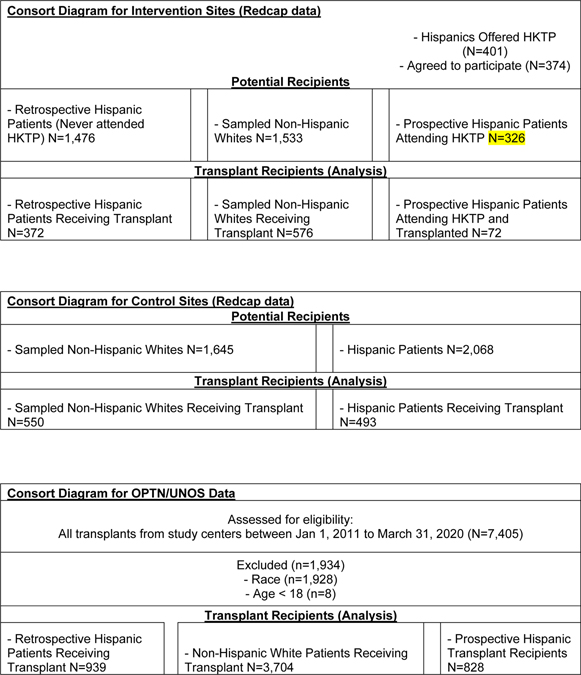

A total of 2,063 recipients were included in the study across all four study sites (Table 1a, Table 1b, Figure 2). The cumulative incidence of transplants (LDKT+DDKT) at Sites A+B was 30.2% and at Sites C+D was 33.8%. Consent rates of Hispanic HKTP attendees and sampled NHW routine English clinic attendees initiating transplant evaluation at intervention sites in the prospective period were high (Site A: 94% Hispanic, 91% NHW, Site B: 92% Hispanic, 72% NHW). Mean age at transplant for Hispanics was slightly younger than NHWs for both intervention (mean age ± SD: 49.66 ± 13.66 vs 55.03 ± 13.65) and control sites (47.21 ± 14.00 vs. 52.47 ± 14.08). Most Hispanics at intervention sites were male (Site A: 60%, Site B: 56%). Among prospective Hispanics who reported their cultural heritage, most were Mexican (Site A: 84%, Site B: 91%). Among prospective Hispanics who reported their preferred language, most preferred Spanish (Site A: 72%, Site B: 66%). See Supporting Table 1 for transplant center characteristics.

Table 1b.

Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Whitea HKTP Study Participants’ Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics by Intervention Site B and Control Site D, n=1,227

| Characteristicb | Intervention Site B, n=740 |

Control Site D, n=487 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic, n=326 | Non-Hispanic White, n=414 | Hispanic, N=243 | Non-Hispanic White, n=244 | |

| Agec, years, mean ± SDd (range) | 50.76 ± 13.42 (19–82) | 50.80 ± 14.70 (20–82) | 46.25 ± 14.25 (19–75) | 50.80 ± 14.70 (20–82) |

|

| ||||

| Sex, Male, n (%) | 183 (56.13) | 257 (62.08) | 148 (60.91) | 150 (61.48) |

|

| ||||

| Marital status, Married/with Partner, n (%) | 217 (66.56) | 279 (67.39) | 125 (51.44) | 147 (60.25) |

|

| ||||

| Highest Education Level, College degree and above, n (%) | 54 (16.62) | 159 (38.68) | 34 (14.60) | 116 (48.94) |

|

| ||||

| Primary Insurance Coverage, Private, n (%) | 127 (39.20) | 194 (48.02) | 82 (34.60) | 108 (45.96) |

|

| ||||

| Body Mass Indexc, kg/m2, mean ± SD^ (range) | 29.68 ± 6.51 (16.26–57.74) | 28.52 ± 6.68 (15.82–59.42) | 27.54 ± 4.92 (17.05–40.74) | 26.67 ± 5.20 (15.82–52.94) |

|

| ||||

| History of Hypertension, n (%) | 265 (81.29) | 311 (75.12) | 233 (95.88) | 227 (93.03) |

|

| ||||

| History of Diabetes, n (%) | 181 (55.52) | 155 (37.44) | 104 (42.80) | 67 (27.46) |

|

| ||||

| Primary cause of ESRDe, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 166 (50.92) | 114 (27.54) | 85 (34.98) | 44 (18.03) |

| Hypertension | 40 (12.27) | 31 (7.49) | 26 (10.70) | 20 (8.20) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 38 (11.66) | 65 (15.70) | 44 (18.11) | 51 (20.90) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 11 (3.37) | 50 (12.08) | 10 (4.12) | 42 (17.21) |

| lga nephropathy | 15 (4.60) | 32 (7.73) | 13 (5.35) | 27 (11.07) |

| Tubular and Intersititial | 5 (1.53) | 35 (8.45) | 12 (4.94) | 22 (9.02) |

| Other | 28 (8.59) | 41 (9.90) | 53 (21.20) | 63 (20.59) |

| Unknown | 23 (7.06) | 46 (11.11) | 9 (3.70) | 8 (3.28) |

|

| ||||

| On dialysisf, n (%) | 244 (74.85) | 195 (47.10) | 162 (66.67) | 111 (45.49) |

|

| ||||

| Waiting time (days), median [IQR] (range) | 237 [481] (1–1721) | 307 [464.5] (1–2718) | 418 [905] (4–3228) | 327.5 [813] (0–2919) |

|

| ||||

| Number of prior transplants, n (%) | ||||

| 0 transplant | 304 (93.25) | 364 (87.92) | 220 (90.53) | 202 (82.79) |

| 1 transplant | 20 (6.13) | 39 (9.42) | 15 (6.17) | 33 (13.52) |

| 2+ transplants | 2 (0.61) | 11 (2.66) | 8 (3.29) | 9 (3.69) |

All study participants in pre-HKTP (Jan 2011- Dec 2016) and post-HKTP (Jan 2017 – Mar 2020). In intervention sites, only participants attending the HKTP are included.

At start of evaluation except age, body mass index (kg/m2), and waiting time (days).

At the time of transplant.

SD = Standard Deviation.

Other includes re-transplantation, congenital kidney disease, and lupus.

At the time of starting transplant evaluation.

Figure 2.

Consort Diagram

3.1.2. OPTN/UNOS Data

Based on OPTN/UNOS data, a total of 5,471 recipients were analyzed for 19 6-month time intervals from January 2011 to March 2020 (Table 1c, Table 1d). Due to COVID, last time period only includes 3 months from January to March 2020. There were 1,767 (32%) Hispanic recipients from January 2011 to March 2020 and the proportion of Hispanic recipients ranged from 26% to 36%.

Table 1c.

Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Whitea OPTN/UNOS Participants’ Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics by Intervention Site A and Control Site C, n=2,055

| Characteristicb | Intervention Site A, n=794 |

Control Site C, n=1,261 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic, n=229 | Non-Hispanic White, n=565 | Hispanic, N=493 | Non-Hispanic White, n=768 | |

| Agec, years, mean ± SDd (range) | 48.81 ± 12.65 (20–75) | 51.88 ± 12.75 (20–83) | 48.15 ± 13.83 (19–81) | 52.81 ± 13.44 (19–78) |

|

| ||||

| Sex, Male, n (%) | 132 (57.64) | 369 (65.31) | 280 (56.80) | 474 (61.72) |

|

| ||||

| Highest Education Level, College degree and above, n (%) | 21 (9.17) | 177 (31.33) | 62 (12.58) | 318 (41.41) |

|

| ||||

| Primary Insurance Coverage, Private, n (%) | 111 (48.47) | 205 (36.28) | 244 (49.49) | 537 (69.92) |

|

| ||||

| Body Mass Indexc, kg/m 2, mean ± SD^ (range) | 28.10±5.02 (16.60–43.13) | 27.61±4.88 (15.78–39.65) | 27.50±4.96 (16.70–50.11) | 27.21±5.19 (15.41–44.62) |

|

| ||||

| History of Diabetese, n (%) | 124 (54.15) | 178 (31.50) | 194 (39.35) | 210 (27.34) |

|

| ||||

| On dialysise, n (%) | 181 (79.04) | 346 (61.24) | 417 (84.58) | 488 (63.54) |

|

| ||||

| Waiting time (days), median [IQR] (range) | 390 [1040] (1–4777) | 243 [740] (0–4775) | 461.5 [991] (0–3050) | 280.5 [710.5] (0–7991) |

|

| ||||

| Number of prior transplants, n (%) | ||||

| 0 transplant | 202 (88.21) | 485 (85.84) | 459 (93.10) | 702 (91.41) |

| 1 transplant | 26 (11.35) | 68 (12.04) | 31 (6.29) | 59 (7.68) |

| 2+ transplants | 1 (0.44) | 12 (2.12) | 3 (0.61) | 7 (0.91) |

All study participants in pre-HKTP (Jan 2011- Dec 2016) and post-HKTP (Jan 2017 – Mar 2020).

At start of evaluation except age, body mass index (kg/m2), and waiting time (days).

At the time of transplant.

SD = Standard Deviation.

At the time of starting transplant evaluation.

Table 1d.

Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Whitea OPTN/UNOS Participants’ Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics by Intervention Site B and Control Site D, n=3,416

| Characteristicb | Intervention Site B, n=2,052 |

Control Site D, n=1,364 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic, n=629 | Non-Hispanic White, n=1,423 | Hispanic, N=416 | Non-Hispanic White, n=948 | |

| Agec, years, mean ± SDd (range) | 52.12 ± 13.75 (18–82) | 56.82 ± 13.69 (18–83) | 48.24 ± 13.77 (19–78) | 50.88 ± 14.86 (19–81) |

|

| ||||

| Sex, Male, n (%) | 361 (57.39) | 868 (61.00) | 262 (62.98) | 568 (59.92) |

|

| ||||

| Highest Education Level, College degree and above, n (%) | 117 (8.60) | 622 (43.71) | 35 (8.41) | 387 (40.82) |

|

| ||||

| Primary Insurance Coverage, Private, n (%) | 272 (43.24) | 699 (49.12) | 159 (38.22) | 544 (57.38) |

|

| ||||

| Body Mass Indexc, kg/m 2, mean ± SD^ (range) | 29.05±5.61 (16.09–44.36) | 27.98±5.50 (15.90–44.16) | 27.51±4.67 (17.36–40.00) | 26.56±4.91 (15.83–42.98) |

|

| ||||

| History of Diabetes, n (%) | 306 (48.65) | 424 (29.80) | 172 (41.35) | 216 (22.78) |

|

| ||||

| On dialysise, n (%) | 534 (84.90) | 985 (69.22) | 370 (88.94) | 647 (68.25) |

|

| ||||

| Waiting time (days), median [IQR] (range) | 349 [722] (1–3468) | 277 [567] (0–2718) | 701 [1254] (3–4077) | 444 [1058] (0–4116) |

|

| ||||

| Number of prior transplants, n (%) | ||||

| 0 transplant | 583 (92.69) | 1255 (88.19) | 385 (92.55) | 802 (84.60) |

| 1 transplant | 40 (6.36) | 43 (10.05) | 25 (6.01) | 124 (13.08) |

| 2+ transplants | 2 (0.32) | 25 (1.76) | 6 (1.44) | 22 (2.32) |

All study participants in pre-HKTP (Jan 2011- Dec 2016) and post-HKTP (Jan 2017 – Mar 2020).

At start of evaluation except age, body mass index (kg/m2), and waiting time (days).

At the time of transplant.

SD = Standard Deviation.

At the time of starting transplant evaluation.

3.2. Fidelity Outcomes

Site A exhibited greater adherence to the protocol than Site B (Table 2). A comparable number of potential recipients attended the HKTP at both intervention sites (Site A: n=165, Site B: n=161). This number slightly increased over time.

Table 2.

Adherence to HKTP Protocol Over Time

| Total | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 20201 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Number of Potential Recipients Attending Education Sessions | |||||

| Site-A | 165 | 43 | 55 | 61 | 6 |

| Site-B | 161 | 50 | 46 | 56 | 9 |

| Number of Hours Performing Outreach to Dialysis Centers and Proportion of Hours that Met Target Goals 2 | |||||

| Site-A | 1486 (55) | 390 (47) | 529 (64) | 536 (64) | 31 (15) |

| Site-B | 729 (27) | 278 (33) | 164 (20) | 247 (30) | 40 (19) |

| Bilingual Outreach Staff 3 | |||||

| Site-A | 1 (50)4 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 05 |

| Site-B | 1 (100)4 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Bicultural Outreach Staff 3 | |||||

| Site-A | 1 (50)4 | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 07 |

| Site-B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Bilingual, non-Bicultural Outreach Staff 3 | |||||

| Site-A | 1 (100)4 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Site-B | 1 (50)4 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Number of Education Sessions Held and Proportion of Sessions that Met Target Goals 6 | |||||

| Site-A | 70 (90) | 21 (88) | 23 (96) | 22 (92) | 4 (67) |

| Site-B | 60 (77) | 21 (88) | 21 (88)7 | 15 (63)7 | 3 (50) |

| Number and Proportion of Education Sessions Delivered by Physician 2 | |||||

| Site-A | 70 (100) | 21 (100) | 23 (100) | 22 (100) | 4 (100) |

| Site-B | 47 (78) | 19 (90) | 16 (76)8 | 12 (80) | 0 |

| Number and Proportion of Patients Sent 90-Day Reminder Letters to Complete Transplant Evaluation | |||||

| Site-A | 34 (21) | 7 (16) | 17 (31) | 10 (16) | 0 |

| Site-B | 2 (1) | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data collection ended March 2020 because of Covid-19.

Sites aimed to conduct 832 hours of outreach per year.

The HKTP protocol required at least one staff member to fit this characteristic.

Number of unique outreach staff who fit this characteristic from 2017 to 2020.

Site-A’s bilingual/bicultural outreach staff was on maternity leave in 2020.

Sites aimed to hold 24 HKTP education sessions per year.

Site-B cancelled 1 HKTP clinic in 2018, and 6 HKTP clinics in 2019 because Site-B's IRB had lapsed.

Four education sessions were initially delivered by a nurse then completed by a physician.

The comparable numbers suggests that fidelity metrics related to getting patients to attend the HKTP sessions did not make a difference in intermediate outcomes. In post-hoc analyses, we focused on differences in fidelity measures occurring during and after the HKTP education sessions to explain where the differences must be arising between the two intervention sites.

As per the HKTP protocol, sites aimed to deliver 24 HKTP education sessions per year, for a total of 78 sessions throughout the intervention period (2.25 yrs) of which a greater number and proportion were delivered at Site A (n=70/78, 90%) than at Site B (n=60/78, 77%). The HKTP protocol called for a bilingual and bicultural transplant physician to deliver all HKTP education sessions held at each site, of which a greater number and proportion were delivered as intended at Site A (n=70/70, 100%) than at Site B (n=47/60, 78%). The physician delivering HKTP education was a transplant surgeon at Site A, and a urologist at Site B. The outreach staff was a bicultural, bilingual nurse at Site A, and a bilingual social worker at Site B. Site A’s outreach staff also followed up with and helped potential recipients complete evaluation appointments. The HKTP protocol called for all potential recipients attending the HKTP at Site A (n=165) and Site B (n=161) to be sent a 90-day reminder letter to complete transplant evaluation of which a greater number and proportion were sent at Site A (n=34, 21%) than at Site B (n=2, 1%).

3.3. Analysis of Likelihood of Receiving Living (versus Deceased) Donor Kidney

3.3.1. Intervention Site A versus Control Site C

For Hispanics at intervention Site A, the likelihood of receiving LDKT was significantly higher at post-intervention compared to pre-intervention (OR=3.17; 95% CI (1.04, 9.63)), while for NHWs, the likelihood of receiving LDKT did not differ between pre- and post-intervention (OR=0.64 (0.30, 1.37)) (Table 3). For Hispanics at control Site C, the likelihood of receiving LDKT did not differ between pre- and post-period (OR=1.02 (0.61, 1.71)), however, for NHWs, the odds of receiving LDKT was significantly higher at post-period compared to pre-HKTP (OR=2.76 (1.62, 4.70)). At intervention Site A, Hispanic versus NHW pre- and post-intervention comparison differed significantly (βA=1.60 (0.26, 2.95), P=0.019), because the LDKT rate for Hispanics increased significantly, but not for NHWs. At control Site C, Hispanic versus NHW pre- and post-intervention comparison also differed significantly (βC=−1.00 (−1.74, −0.25), P=0.009), however, we observed a significant increase in LDKT rate for NHWs, but not for Hispanics. Comparison of difference-in-difference (Hispanics versus NHWs, pre- versus post-intervention) between intervention and control sites (3-way interaction) indicated HKTP implemented at intervention Site A was successful (βA-βC=2.60 (1.06, 4.14), P=0.0009).

Table 3.

Patient-level Analyses for the Effect of the HKTP intervention on the Likelihood of Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Recipients Receiving Living Donor (versus Deceased) Kidney Transplantation Comparing Post- versus Pre-Intervention for Intervention Site A versus Control Site C, and Intervention Site B versus Control Site D, Separately

| Intervention Site A & Control Site C, n=846 |

Intervention Site B & Control Site D, n=1,217 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post- versus Pre-intervention |

Hispanic vs. NHW Post vs Pre-Intervention Comparisonb | Post- versus Pre-intervention |

Hispanic vs. NHW Post vs Pre-Intervention Comparisonc | |||||

| ORa | (95% CI) | P | ORa | (95% CI) | P | |||

| Intervention site | βA (95% CI)= 1.60 (0.26, 2.95), P=0.019 | βB (95% CI)= 0.76 (−0.18, 1.71), P=0.114 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 3.17 | (1.04, 9.63) | 0.042 | 0.88 | (0.40, 1.94) | 0.747 | ||

| NHW | 0.64 | (0.30, 1.37) | 0.247 | 0.41 | (0.24, 0.69) | 0.0007 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Control site | βC (95% CI)= −1.00 (−1.74,−0.25), P=0.009 | βD (95% CI)= −0.48 (−1.29, 0.34), P=0.250 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.02 | (0.61, 1.71) | 0.947 | 0.45 | (0.28, 0.90) | 0.021 | ||

| NHW | 2.76 | (1.62, 4.70) | 0.0002 | 0.80 | (0.46, 1.41) | 0.447 | ||

Odds ratio (OR) comparing post-vs. pre-intervention adjusted for sex (male vs female), age (year) at transplant, body mass index (kg/m2) at transplant.

βA and βC are the regression coefficients of 2-way interaction comparing post- vs. pre-intervention difference between Hispanic and non-Hispanic White for intervention sites A and C, irrespectively. Comparison of βA and βC is βA − βC (95% CI)=2.60 (1.06, 4.14), P=0.0009.

βB and βD are the regression coefficients of 2-way interaction comparing post- vs. pre-intervention difference between Hispanic and non-Hispanic White for intervention sites B and CD, irrespectively. Comparison of βB and βD is βB − βD (95% CI)=1.24 (−0.007, 2.49), P =0.051.

3.3.2. Intervention Site B versus Control Site D

For Hispanics at intervention Site B, the likelihood of receiving LDKT did not differ between pre- and post-intervention (OR=0.88 (0.40, 1.94)), while for NHWs, the likelihood of receiving LDKT was significantly lower at post-intervention compared to pre-intervention (OR=0.41 (0.24, 0.69)) (Table 3). At control Site D, for Hispanics, the likelihood of receiving LDKT was significantly lower at post-period compared to pre-period (OR=0.45 (0.28, 0.90)), however, for NWHs, the likelihood of receiving LDKT did not differ at post-period compared to pre-period (OR=0.80 (0.46, 1.41)). Hispanic versus NHW pre- and post-intervention comparison did not differ for the intervention Site B (βB=0.76 (−0.18, 1.71), P=0.114) and control site D (βD=−0.48 (−1.29, 0.34), P=0.250). This trend was driven largely by the lower LDKT rates for Hispanics at control Site D, rather than by an increase in LDKT rates for Hispanics at Site B (βB-βD=1.24 (−0.007, 2.49), P=0.051).

3.4. Analysis of Ratio of Hispanic LDKT rate to NHW LDKT rate

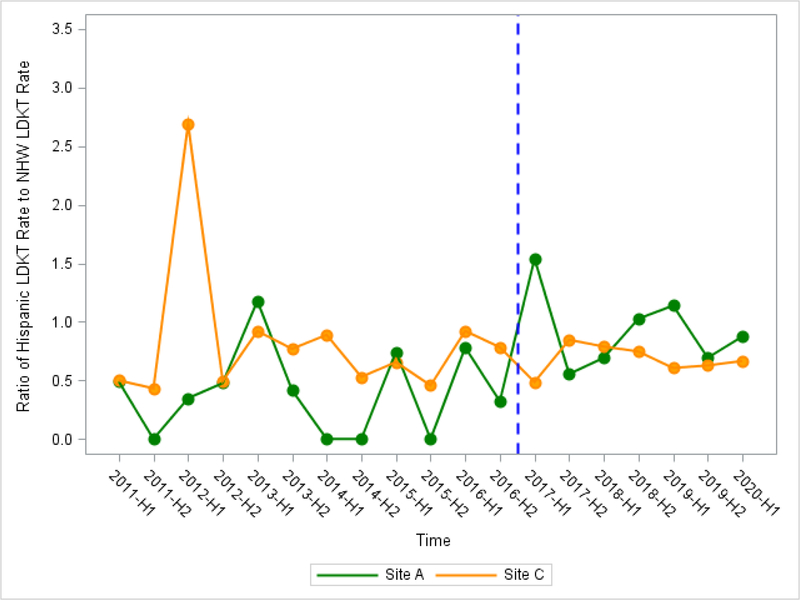

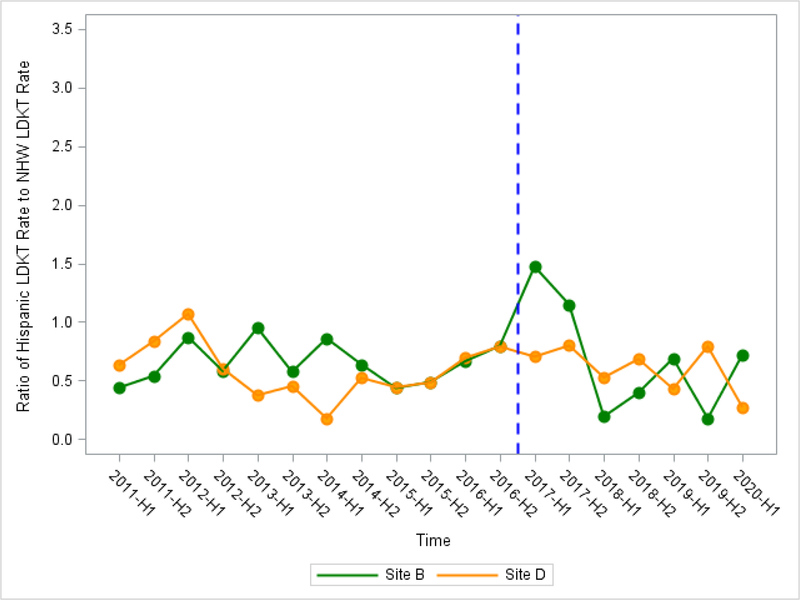

At intervention sites using 6-month interval time-points, mean ratio of Hispanic LDKT rate among all transplant recipients to NHW LDKT rate was higher at post-intervention compared to pre-intervention, however, both sites did not reach statistical significance (Site A: b2=0.63 (−0.07, 1.33), P=0.090; Site B: b2=0.12 (−0.72, 0.95), P=0.78) (Table 4a, Table 4b, Figure 3a, Figure 3b). At control sites, we observed no change in mean ratio of Hispanic LDKT rate to NHW LDKT rate between pre- and post-intervention.

Table 4a.

Interrupted Times Series Analyses for the Effect of HKTP Intervention on Ratio of Hispanic LDKT Rate a to Non-Hispanic White LDKT Ratea Using 19 6-month time intervals for Intervention Site A and Control Site C, Separately

| Intervention Site A, n=794 | Control Site C, n=1,261 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimate | (95 % CI) | P | Parameter Estimate | 95 % CI | P | |

| b0, Baseline level at 2011-H1 | 0.38 | (0.01, 0.74) | 0.054 | 1.06 | (0.63, 1.48) | 0.0002 |

| b1, Pre-intervention trend | 0.005 | (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.864 | −0.04 | (−0.11, 0.03) | 0.248 |

| b2, Level change at post-intervention | 0.63 | (−0.07, 1.33) | 0.090 | 0.12 | (−0.72, 0.95) | 0.777 |

| b3, Post-intervention trend | −0.04 | (−0.18, 0.10) | 0.577 | 0.03 | (−0.14, 0.19) | 0.759 |

Note: 2020-H1 only includes 3 months from January to March 2020.

LDKT rate is computed by number of LDKTs over total KTs.

Table 4b.

Interrupted Times Series Analyses for the Effect of HKTP Intervention on Ratio of Hispanic LDKT Ratea to Non-Hispanic White LDKT Ratea Using 19 6-month time intervals for Intervention Site B and Control Site D, Separately

| Intervention Site B, n=2,052 | Control Site D, n=1,364 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimate | 95 % CI | P | Parameter Estimate | 95 % CI | P | |

| b0, Baseline level at 2011-H1 | 0.63 | (0.31, 0.96) | 0.001 | 0.66 | (0.37, 0.95) | 0.0003 |

| b1, Pre-intervention trend | 0.004 | (−0.05, 0.05) | 0.889 | −0.01 | (−0.06, 0.03) | 0.584 |

| b2, Level change at post-intervention | 0.54 | (−0.10, 1.18) | 0.107 | 0.26 | (−0.26, 0.77) | 0.332 |

| b3, Post-intervention trend | −0.14 | (−0.27, −0.005) | 0.053 | −0.04 | (−0.14, 0.07) | 0.504 |

Note: 2020-H1 only includes 3 months from January to March 2020.

LDKT rate is computed by number of LDKTs over total KTs.

Figure 3a.

Ratio of Hispanic LDKT Rate to Non-Hispanic White LDKT Rate Using 19 6-month time intervals by Intervention Site A and Control Site C (OPTN/UNOS)

Figure 3b.

Ratio of Hispanic LDKT Rate to Non-Hispanic White LDKT Rate Using 19 6-month time intervals by Intervention Site B and Control Site D (OPTN/UNOS)

3.5. Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed and results were robust accounting for different secular trends and allowing for an intervention effect lag (See details in Supporting File 1).

4. Discussion

Through a multi-site evaluation, our complex, culturally targeted intervention effectively increased LDKT in Hispanic patients at one of two intervention sites. Site A was able to achieve a significant increase in Hispanic LDKTs by 47% (from pre-HKTP 20.3% to post-HKTP 29.8% in LDKT rates). The implications for reducing Hispanic LDKT disparities nationally are great if other similar U.S. transplant centers that perform LDKTs and serve a large Hispanic population implemented the HKTP with fidelity and achieved the same rate of LDKT increase.

As Hispanics are amongst the fastest growing minority groups comprising 18.4% of the US population,43 reducing inequities in LDKT is critical to addressing the disproportionate public health problem of kidney disease in this population. Our financial feasibility analysis found that the impact of the HKTP on the total costs of each intervention transplant center was less than 1.0% and could be recoverable by reimbursement of Organ Acquisition costs, underscoring how achieving equity can be financially viable.44 Any gain in health equity is worthwhile given the low cost of HKTP implementation.

Implementation fidelity is associated with intervention effectiveness.45, 46 Based on our analysis of HKTP pre-implementation barriers and facilitators, we identified institutional, provider, and attitudinal factors that may have contributed to implementation fidelity.14 Our implementation evaluation data suggest that Site A had greater implementation fidelity than Site B.

Several contextual factors may have contributed to the HKTP’s effectiveness at Site A, and not at Site B. First, it may be easier to detect improvement if the baseline value is relatively low like Site A, than at centers with relatively high rates of LDKT. Second, the wait time for DDKT was relatively short at Site B compared to Site A, diminishing the need for LDKT. Consistently, DDKT comprised a greater proportion of transplants at Site B (80.2%) than at Site A (66.9%) from 2017–2020.7 Further, social determinants of health may explain receipt of LDKT, including patients’ social support.47

Culturally sensitive components of our intervention entailed the inclusion of family members, particularly elders, in transplant education sessions given their centrality to healthcare decision making. By accompanying patients at evaluation, families could increase their awareness and willingness to be living donors. An intervention directed at the patient and family/friends was more likely to attain donor inquiries and evaluations than the control group directed at the patient alone, highlighting the value of family involvement.20 Other culturally targeted interventions have been effective in increasing LDKT inquiries.20, 37 However, the effectiveness of these interventions in other clinical contexts has been inconclusive.48, 49 Further, the engagement of bilingual and bicultural transplant team members facilitated communication about LDKT and likely better enabled patients to complete transplant evaluation, as our prior research suggested.50, 51 The slight increase over time in number of Hispanic patients who attended the HKTP at both sites suggests that marketing and outreach worked to increase access to transplant evaluation.

A similar number of patients attended HKTP education sessions at each intervention site, suggesting that modifications to the intervention leading to session attendance did not make a difference in the outcome. However, there were key differences in implementation fidelity during and after the education session across both intervention sites, including the availability of a transplant surgeon and bicultural-bilingual nurse. Because the fidelity to the intervention was lower in these areas in the site that did not improve the number of LDKTs, we hypothesize that some or all of these components are critical to the intervention’s success.

As a complex, multi-level intervention, the 16 HTKP intervention components (e.g., outreach, culturally congruent education, and patient follow-up), have been evaluated for effectiveness in aggregate, rather than individually. Thus, it is unknown which intervention component(s) positively affected the outcomes, and to what extent. Additionally, it is unclear whether modifications to any individual components may have affected intervention outcomes. Implementation science data about the factors influencing intervention implementation are valuable to help explain why the intervention did not achieve its desired outcomes. Examining modifications to HKTP components may illuminate which component(s) most directly affected the intended outcomes.52 Future analyses will examine how factors affecting HKTP implementation fidelity over time may explain observed differences in intervention effectiveness between intervention sites.

Resources currently available to help translate our research to the real-world setting include the published study protocol,30 which describes HKTP components in detail; scripts, protocols, and other materials will be made available in an online repository. Intervention complexity is a major barrier to implementing interventions.53 It took 6–9 months to prepare to launch the first HKTP education session. Conducting a large-scale Dissemination and Implementation trial is an appropriate next step before advocating wider adoption of the HKTP. Such research could develop tools, policies, and guidelines that support scaling-up the intervention.

Our study has strengths. The hybrid design enabled the identification of specific implementation factors (e.g., holding more HKTP sessions) factors (e.g., more time spent performing outreach, greater availability of bilingual and bicultural outreach workers, holding more HKTP sessions) associated with LDKT increases. Differences between the two sites in fidelity in delivering these 8 HKTP components suggests these HKTP components explain differences in the resulting LDKT outcomes. The design highlights the essential role of bilingual and bicultural outreach workers and follow-up after the education session. Another strength is that the HKTP intervention is culturally sensitive in design and content, thereby facilitating patient-centered care.

There are study limitations. While an ideal study design would be a randomized controlled trial that randomizes patients within each center, it is laden by contamination effects. Our prospective pre-post design was scientifically and ethically sound, though may be limited by self-selection bias. Approximately 50% of Hispanic potential recipients scheduling their transplant evaluation appointment at each intervention site elected to attend the routine English clinic because they primarily spoke English. Thus, the sample size of Hispanics in the intervention arm was smaller than anticipated. The study site data set was limited by a large degree of missingness; Site A had more missing data than other sites, possibly owing to a change in their electronic medical record system during the study period.

Although the 4 sites did not make any major policy/practice changes during the study period and our analysis adjusted for time changes across centers, we may not have accounted for all possible site changes over time. Site D did change part of their care delivery in 2017 by making a few aspects of care similar to the HKTP. In a sensitivity analysis, we analyzed Site D to see if their changes increased their LDKT rate, but it did not show any significant effect.

Interpretation of findings from OPTN/UNOS must be cautioned because they are based on all Hispanic patients initiating evaluation in the prospective period, not solely on those who elected to partake in the HKTP clinic at intervention sites. The ITS analysis had an insufficient number of time points to enable a large enough model to control for more covariates because the COVID-19 pandemic shortened the study.

The HKTP was originally developed at NM, where most Hispanics were of Mexican nationality, similar to most Hispanic study participants. Because Hispanics are a heterogeneous group and different experiences can influence disparities,54 future research is needed to evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of the HKTP with Hispanics of other nationalities.

Conclusion

Our culturally targeted intervention effectively increased LDKT in Hispanic patients at one of two transplant programs that had greater implementation fidelity. After adjusting implementation processes, future research should evaluate the HKTP intervention implemented broadly, in different hospital systems, to reduce Hispanic LDKT disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the transplant stakeholders from both study sites for their engagement in this study. Special thanks go to Julieta Williams, Jazmin Beccera, Ashanti Smith, Brie Barnes, and Ann Cline, for their excellent research assistance. We are grateful for the guidance provided by Ronald Ackerman and Tara Lagu. REDCap is supported at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science (NUCATS) Institute. Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

NIDDK funded this research (1R01DK104876 to EJ Gordon and JC Caicedo, Co-PIs).

Abbreviations

- CFIR

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- DDKT

Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation

- ESKD

End-Stage Kidney Disease

- HKTP

Hispanic Kidney Transplant Program

- IRB

Institutional Review Boards

- ITS

Interrupted Time Series

- KT

Kidney Transplantation

- LDKT

Living Donor Kidney Transplantation

- NHW

Non-Hispanic White

- NM

Northwestern Medicine®

- OPTN/UNOS

Organ Procurement and Transplant Network/United Network for Organ Sharing

- PI

Principal Investigator

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

Data Available Statement

Aggregate data are available via ClinicalTrials.gov. Otherwise, data are not available.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2019 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axelrod DA, McCullough KP, Brewer ED, Becker BN, Segev DL, Rao PS. Kidney and pancreas transplantation in the United States, 1999–2008: the changing face of living donation. Am J Transplant. Apr 2010;10(4 Pt 2):987–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03022.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. An economic assessment of contemporary kidney transplant practice. Am J Transplant. May 2018;18(5):1168–1176. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purnell TS, Hall YN, Boulware LE. Understanding and overcoming barriers to living kidney donation among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Advances in chronic kidney disease. Jul 2012;19(4):244–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai N, Lora CM, Lash JP, Ricardo AC. CKD and ESRD in US Hispanics. Am J Kidney Dis. Jan 2019;73(1):102–111. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.02.354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Network for Organ Sharing. Transplant trends; 2019. https://unos.org/data/transplant-trends/

- 7.Organ Procurement Transplant Network/United Network for Organ Sharing. Transplants by donor type. U.S. Transplants Performed: January 1, 1988 - March 31, 2021 [https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/] Data as of May 4, 2021. (Accessed May 5, 2021). https://unos.org/data/transplant-trends/

- 8.Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, et al. Association of Race and Ethnicity With Live Donor Kidney Transplantation in the United States From 1995 to 2014. Jama. Jan 2 2018;319(1):49–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noe-Bustamante L, MH L, Krogstad J. U.S. Hispanic population surpassed 60 million in 2019, but growth has slowed [https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/07/u-s-hispanic-population-surpassed-60-million-in-2019-but-growth-has-slowed/] (Accessed 4–11-21). Pew Research Center. 2020. (July 7) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krogstad J, Noe-Bustamante L. Key facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month [https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/10/key-facts-about-u-s-latinos-for-national-hispanic-heritage-month/] (Accessed 4–11-21). Pew Research Center. 2020. (September 10) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon EJ, Mullee JO, Ramirez DI, et al. Hispanic/Latino concerns about living kidney donation: a focus group study. Prog Transplant. Jun 2014;24(2):152–62. doi: 10.7182/pit2014946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel JT, O’Brien EK, Alvaro EM, Poulsen JA. Barriers to living donation among low-resource Hispanics. Qual Health Res. Oct 2014;24(10):1360–7. doi: 10.1177/1049732314546869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ríos Zambudio A, López-Navas AI, Garrido G, et al. Attitudes of Latin American Immigrants Resident in Florida (United States) Toward Related Living Kidney Donation. Prog Transplant. Mar 2019;29(1):11–17. doi: 10.1177/1526924818817073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon EJ, Romo E, Amórtegui D, et al. Implementing culturally competent transplant care and implications for reducing health disparities: A prospective qualitative study. Health Expect. Dec 2020;23(6):1450–1465. doi: 10.1111/hex.13124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shilling LM, Norman ML, Chavin KD, et al. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the barriers to living donor kidney transplantation among African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. Jun 2006;98(6):834–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, et al. Identifying and addressing barriers to African American and non-African American families’ discussions about preemptive living related kidney transplantation. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Prog Transplant. Jun 2011;21(2):97–104; quiz 105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. National Standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate Services in Health Care Final Report. Office of Minority Health U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/checked/finalreport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon EJ, Feinglass J, Carney P, et al. A Culturally Targeted Website for Hispanics/Latinos About Living Kidney Donation and Transplantation: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Increased Knowledge. Transplantation. May 2016;100(5):1149–60. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000000932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arriola KR, Powell CL, Thompson NJ, Perryman JP, Basu M. Living donor transplant education for African American patients with end-stage renal disease. Prog Transplant. Dec 2014;24(4):362–70. doi: 10.7182/pit2014830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodrigue JR, Paek MJ, Egbuna O, et al. Making house calls increases living donor inquiries and evaluations for blacks on the kidney transplant waiting list. Transplantation. Nov 15 2014;98(9):979–86. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvaro EM, Siegel JT, Crano WD, Dominick A. A mass mediated intervention on Hispanic live kidney donation. J Health Commun. Jun 2010;15(4):374–87. doi: 10.1080/10810731003753133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weng FL, Peipert JD, Holland BK, Brown DR, Waterman AD. A Clustered Randomized Trial of an Educational Intervention During Transplant Evaluation to Increase Knowledge of Living Donor Kidney Transplant. Prog Transplant. Dec 2017;27(4):377–385. doi: 10.1177/1526924817732021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Cui Y, et al. Your Path to Transplant: A randomized controlled trial of a tailored expert system intervention to increase knowledge, attitudes, and pursuit of kidney transplant. Am J Transplant. Mar 2021;21(3):1186–1196. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. Aug 7 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. May 17 2016;11:72. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Garvey CA, Hill C, Fogg L, Resnick B. Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Research in nursing & health. Apr 2010;33(2):164–73. doi: 10.1002/nur.20373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. Sep 2004;23(5):443–51. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon EJ, Lee J, Kang R, et al. Hispanic/Latino Disparities in Living Donor Kidney Transplantation: Role of a Culturally Competent Transplant Program. Transplantation direct. Sep 2015;1(8):e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. Sep 29 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon EJ, Lee J, Kang RH, et al. A complex culturally targeted intervention to reduce Hispanic disparities in living kidney donor transplantation: an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study protocol. BMC health services research. May 16 2018;18(1):368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. Mar 2012;50(3):217–26. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caracelli VJ, Greene JC. Data Analysis Strategies for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 1993;15(2):195–207. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Bmj. Mar 23 2010;340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Bmj. Mar 7 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. Apr 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patzer RE, Pastan SO. Measuring the disparity gap: quality improvement to eliminate health disparities in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. Feb 2013;13(2):247–8. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, et al. Effectiveness of educational and social worker interventions to activate patients’ discussion and pursuit of preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. Mar 2013;61(3):476–86. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Segev DL, Gentry SE, Montgomery RA. Association between waiting times for kidney transplantation and rates of live donation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. Oct 2007;7(10):2406–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01922.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu DA, Robb ML, Watson CJE, et al. Barriers to living donor kidney transplantation in the United Kingdom: a national observational study. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. May 1 2017;32(5):890–900. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mustian MN, Kumar V, Stegner K, et al. Mitigating Racial and Sex Disparities in Access to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation: Impact of the Nation’s Longest Single-center Kidney Chain. Ann Surg. Oct 2019;270(4):639–646. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000003484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reeves-Daniel AM, Farney AC, Fletcher AJ, et al. Ethnicity, medical insurance, and living kidney donation. Clinical transplantation. Jul-Aug 2013;27(4):E498–503. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purnell T, Xu P, Leca N, Hall Y. Racial differences in determinants of live donor kidney transplantation in the United States. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2013;13(6):1557–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- 44.Wang A, Caicedo JC, McNatt G, Abecassis M, Gordon EJ. Financial Feasibility Analysis of a Culturally and Linguistically Competent Hispanic Kidney Transplant Program. Transplantation. Mar 1 2021;105(3):628–636. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000003269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beck AK, Baker AL, Carter G, et al. Is fidelity to a complex behaviour change intervention associated with patient outcomes? Exploring the relationship between dietitian adherence and competence and the nutritional status of intervention patients in a successful stepped-wedge randomised clinical trial of eating as treatment (EAT). Implement Sci. Apr 26 2021;16(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01118-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Houston TK, Sadasivam RS, Allison JJ, et al. Evaluating the QUIT-PRIMO clinical practice ePortal to increase smoker engagement with online cessation interventions: a national hybrid type 2 implementation study. Implement Sci. Nov 2 2015;10:154. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0336-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ladin K, Emerson J, Butt Z, et al. How important is social support in determining patients’ suitability for transplantation? Results from a National Survey of Transplant Clinicians. J Med Ethics. Oct 2018;44(10):666–674. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2017-104695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McPheeters ML, Kripalani S, Peterson NB, et al. Closing the quality gap: revisiting the state of the science (vol. 3: quality improvement interventions to address health disparities). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). Aug 2012;(208.3):1–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Improving Cultural Competence To Reduce Health Disparities (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; ) (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gordon E, Romo E, Amortegui D, et al. Implementing Culturally Competent Transplant Care and Implications for Reducing Health Disparities: A Prospective Qualitative Study. Health Expectations. 2020;23(6):1450–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gordon E, Reddy E, Gil S, et al. A Culturally Competent Transplant Program Improves Hispanics’ Knowledge and Attitudes about Live Kidney Donation and Transplantation. Progress in Transplantation. 2014;24(1):56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. Jun 10 2013;8:65. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gäbler G, Coenen M, Fohringer K, Trauner M, Stamm TA. Towards a nationwide implementation of a standardized nutrition and dietetics terminology in clinical practice: a pre-implementation focus group study including a pretest and using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC health services research. Nov 29 2019;19(1):920. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4600-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roth KB, Musci RJ, Eaton WW. Heterogeneity of Latina/os’ acculturative experiences in the National Latino and Asian American Study: a latent profile analysis. Ann Epidemiol. Oct 2019;38:48–56.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Aggregate data are available via ClinicalTrials.gov. Otherwise, data are not available.