Abstract

Truncated recombinant nucleocapsid proteins (rNPs) of Hantaan virus (HTNV), Seoul virus (SEOV), and Dobrava virus (DOBV) were expressed by a baculovirus system. The truncated rNPs, which lacked 49 (rNP50) or 154 (rNP155) N-terminal amino acids of the NPs of HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV, were able to differentiate HTNV-, SEOV-, and DOBV-specific immune sera. Recombinant NP50s retained higher reactivities than rNP155s and were proven useful for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISAs based on the rNP50s of HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV successfully differentiated three groups of patient sera, previously defined by neutralization tests: 17 with HTNV infection, 12 with SEOV infection, and 20 with DOBV infection. The entire rNP of Puumala virus (PUUV) distinguished PUUV infection from the other types of hantavirus infection. Serotyping with these rNP50s can be recommended as a rapid and efficient system for hantavirus diagnosis.

Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome are rodent-borne viral zoonoses caused by viruses in the genus Hantavirus, family Bunyaviridae (3). Four antigenically and genetically distinct hantaviruses are known to cause HFRS. They are defined as different serotypes: Hantaan virus (HTNV), Seoul virus (SEOV), Dobrava virus (DOBV), and Puumala virus (PUUV). Sin Nombre virus and related viruses cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. There is a close association between the viruses and their rodent hosts (10, 14, 21). At present, the only serological assay available to define the serotype of a causative hantavirus is the neutralization test (NT) (4, 12, 15). However, the NT needs specialized techniques and equipment, takes 1 to 2 weeks to perform, and requires a containment laboratory for virus manipulation.

Hantavirus nucleocapsid protein (NP) possesses immunodominant, linear, cross-reactive epitopes within the first 100 amino acids (aa) of the N terminus (6, 7, 26). In addition, serotype-specific conformational epitopes have been detected in about half of the C termini of the NPs by serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (20, 28). Recombinant NPs (rNPs) of HTNV and SEOV that were truncated 154 aa from the N termini of the NPs (rNP155s) were previously evaluated as diagnostic antigens with expression by a baculovirus system (13). An indirect immunofluorescent-antibody (IFA) test, using the truncated rNPs HTNV rNP155 and SEOV rNP155 as antigens, was able to differentiate HTNV and SEOV infections serologically. However, at least two problems remained. (i) The IFA titers with the rNP155s were more than 10 times lower than those with authentic viruses or whole rNPs. Therefore, patient sera with low titers could not be differentiated; (ii) The antigenicity of HTNV rNP155 was too low to be applied in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). These problems were probably caused by an alteration of the antigenic structure after removing 154 aa. It was reported that the cross-reactive, immunodominant epitopes of Sin Nombre virus NP were mapped to the segment between aa 17 and 59 and that they lacked reactivity as a result of truncation of the first 32 aa of the N terminus of Sin Nombre virus NP (26).

In this study, to make the antigenic structures of rNPs similar to those of authentic NPs that lack the cross-reactive immunodominant epitopes, we prepared truncated rNPs that lacked 49 aa in the N-terminal regions of the NPs (rNP50s) of HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV and examined their applicabilities as serotyping antigens, particularly for use in ELISA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

HTNV strain 76-118 (11), SEOV strain SR-11 (9), DOBV strain Saaremaa (14), and PUUV strain Bashikiria CG1820 (kindly donated by H.-W. Lee) were used as representative strains of the HTNV, SEOV, DOBV, and PUUV serotypes, respectively. They were propagated in the E6 clone of Vero cells (ATCC C1008; Cell respository line 1586) grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. Recombinant baculoviruses (Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus) containing coding information for the NPs of HTNV strain 76-118 and SEOV strain SR-11 were kindly supplied by C. S. Schmaljohn of the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases, Frederick, Md. (23). The baculovirus-expressing PUUV strain Sotkamo NP was kindly supplied by A. Vaheri of Helsinki University, Helsinki, Finland (25). The cDNA containing coding information for the NP of DOBV strain Saaremaa was kindly supplied by A. Plyusnin of Helsinki University (14). The recombinant baculoviruses were propagated in High Five cells (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands) grown in Grace's insect cell culture medium (Grace's medium; GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Construction of recombinant baculoviruses expressing truncated rNPs.

Primers were designed from previously published sequences (2, 14, 22). The portion of the gene coding for aa 155 to 429 of DOBV NP was amplified from cDNA of the S segment of DOBV strain Saaremaa by PCR with the primers 5′-ACAATGTCGACATGAGGATTCGATTTAAG-3′ and DOB-SalI-429, 5′-GGCCGGTCGACTTAAAGCTTAAGCGGCTC-3′ (the first methionine codon [ATG; underlined] was added as an initiation codon; the SalI sites are shown in italics). The gene encoding aa 50 to 429 of HTNV NP was amplified from cDNA of the S segment by PCR with the primers 5′-GACCGAGAATTCATGGCAGTATCTATCCAGGCAAA-3′ and 5′-TCCGTCGACTTAATTAGAGTTTCAAAGGC-3′ (the EcoRI and SalI sites are shown in italics). To generate the cDNA encoding aa 50 to 429 of SEOV NP by PCR, the primers 5′-CGGAATTCTATGGCAGCTTCAATACAATC-3′ and 5′-TCCGTCGACTTATAATTTCATAGGTTCCT-3′ were used. To generate the cDNA encoding aa 50 to 429 of DOBV NP, the primers 5′-GAGTGGTCGACAAAGCATGGCACAATCAATTCAGGGAAA-3′ and DOB-SalI-429 were used. Each amplified DNA product with added restriction enzyme sites was subcloned into pBluescript II KS (Stratagene), using the restriction enzymes that recognized the restriction sites added by PCR. Then, each subcloned DNA was excised from pBluescript II KS by digestion with the same restriction enzyme and ligated into the donor plasmid pFASTBAC1 (GIBCO BRL). Genes for DOBV whole rNP, DOBV rNP155, DOBV rNP50, HTNV rNP50, and SEOV rNP50 were expressed using the BAC-TO-BAC baculovirus expression system (GIBCO BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Truncated genes encoding aa 155 to 429 of HTNV NP and SEOV NP were generated as previously described (13).

Preparation of whole rNPs and truncated rNPs.

Monolayers of High Five cells cultured in 75-cm2 flasks were inoculated with 1 ml of recombinant baculovirus culture fluid (2.0 × 108 focus-forming units/ml). Three days after incubation at 27°C, the cells were pelleted by low-speed centrifugation (500 × g for 5 min). The cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) and centrifuged again. Finally, the cells were suspended in 2 ml of PBS and sonicated four times for 15 s each time on ice, and the cell extract was stored at −80°C.

MAbs, rabbit immune sera, and patient sera.

Clones producing the MAbs ECO2, ECO1, GBO4, DCO3, and BDO1, directed against the NP of hantavirus, were kindly supplied by J. B. McCormick and C. J. Peters of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. (20). The MAbs E5/G6, C16D11, F23A1, and C24B4, directed against the NP of HTNV, were prepared as previously described (28). Rabbit immune sera against HTNV, SEOV, DOBV, and PUUV were obtained from rabbits infected with live viruses, as previously described (12). A total of 17 convalescent sera from HFRS patients, previously diagnosed as infected by HTNV, were kindly provided by Y.-X. Yu of the National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products, Beijing, China. Convalescent sera from HFRS patients infected by SEOV were kindly provided by Y. Nishimune of the Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University (five specimens); I. Kim of Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea (six specimens); and H.-W. Lee, Seoul, Korea (one specimen). These sera were obtained from patients with laboratory rat-associated SEOV infections. A total of 20 previously characterized sera, of which 7 were acute-phase sera and 13 were convalescent sera, were obtained from DOBV-infected patients from Bosnia and Estonia (12; Å. Lundkvist, V. Vasilenko, I. Golovljova, A. Plyusnin, and A. Vaheri, Letter, Lancet 352:369, 1998). One convalescent-serum specimen from a nephropathia epidemica patient infected by PUUV was kindly provided by B. Niklasson, Stockholm, Sweden.

IFA test.

The IFA test was carried out using previously described methods (13, 27). Acetone-fixed smears of High Five cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses were used as antigens.

Focus reduction NT.

One-hundred microliters of serial twofold dilutions of serum were mixed with an equal volume of virus suspension containing 400 focus-forming units of virus at 37°C for 1 h. Fifty microliters of the mixture was then inoculated onto Vero E6 cell monolayers in 96-well plates for HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV or 8-well glass slides for PUUV and incubated at 37°C for 1 h in a CO2 incubator. After adsorption for 1 h, the wells were overlaid with medium containing 1.5% carboxymethyl cellulose. After incubation for 7 days, the monolayers were fixed with acetone-methanol (1:1) and dried. The 96-well plate monolayers were overlaid with a polyclonal rabbit serum (diluted 1:200 with PBS), made by immunizing a rabbit with truncated rNP of HTNV (aa 1 to 244) with a six-histidine tag expressed in Escherichia coli, using the Xpress express and purification system (Invitrogen), for 1 h at 37°C. After being washed with PBS, the 96-well plate monolayers were incubated with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:500) (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) for 1 h at 37°C. The 96-well plate monolayers were washed three times and subsequently stained with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate (Sigma Chemical Co.) as described in the manufacturer's instructions. The infected cell foci were counted using a stereoscopic microscope. To detect PUUV-infected cells on the eight-well glass slide monolayers, the IFA was carried out using MAb E5/G6. The infected cell foci were counted using a fluorescence microscope. The NT titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution resulting in a reduction of greater than 80% in the number of infected cell foci.

Western blotting.

Western blotting was performed using previously published methods (29). The NP-specific MAb E5/G6 or polyclonal rabbit immune sera were used to detect the antigens on the membrane.

Capture ELISA.

Ninety-six-well plates were coated with MAb E5/G6 (2 μg/ml in PBS) as a capture antibody for 1 h at 37°C. ELISA was performed as described previously (13, 28). The quantities of each antigen were equalized using the density of the band in Western blots with MAb E5/G6. Borna disease virus p24 expressed by the baculovirus system was used as a negative control antigen (16).

RESULTS

Antigenic characterization of rNPs expressed by recombinant baculovirus with MAbs in the IFA test.

The IFA test of High Five cells expressing rNPs was carried out using hantavirus-specific MAbs (Table 1). The reactivity patterns of whole rNPs agreed with the reactivity patterns of Vero E6 cell-cultured authentic viruses (8, 28). This showed that the cross-reactivities of whole rNPs of HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV, like the cross-reactivity of the NPs of authentic hantavirus, were very high. The reactivity pattern of the PUUV whole rNP was different from the reactivity pattern of the whole rNPs of HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV with MAb ECO2.

TABLE 1.

Antigenic characterization of rNPs expressed by recombinant baculovirus with MAbs in the IFA testa

| rNP | Result

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-reactive MAbs

|

MAbs specific for:

|

||||||||

| HTNV

|

SEOV

|

||||||||

| ECO2 | ECO1 | GBO4 | E5/G6 | C16D11 | F23A1 | C24B4 | BDO1 | DCO3 | |

| HTNV whole rNP | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| SEOV whole rNP | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| DOBV whole rNP | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| PUUV whole rNP | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| HTNV rNP50 | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| SEOV rNP50 | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| DOBV rNP50 | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| HTNV rNP155 | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| SEOV rNP155 | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| DOBV rNP155 | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

Data are presented as a positive (+) or negative (−) result by IFA test.

Truncated rNPs that lacked 49 aa of the N terminus of the NP (rNP50) of HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV lacked reactivity to two of the three cross-reactive MAbs (ECO2, ECO1, and GBO4) that recognized immunodominant epitopes of the N terminus of NP (28).

On the other hand, truncated rNPs that lacked 154 aa of the N terminus of the NP (rNP155) of HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV reacted to only one cross-reactive MAb, E5/G6. Moreover, rNP155s reacted with serotype-specific MAbs.

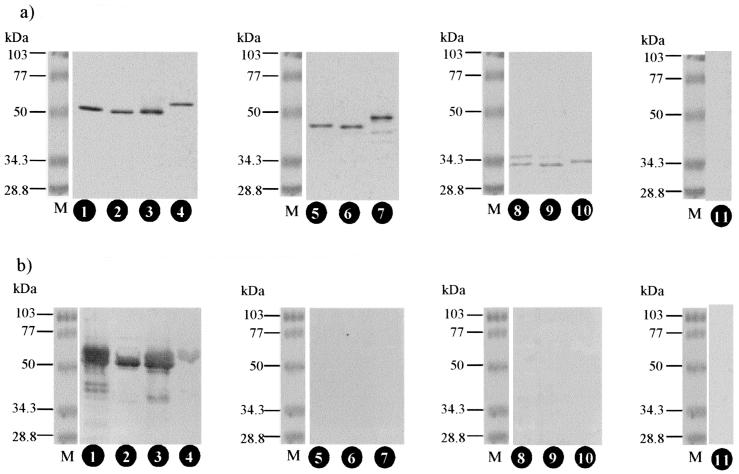

Reactivity of rNPs with rabbit immune sera. (i) Western blotting.

Western blotting analysis confirmed the expression of whole and truncated rNPs by the baculovirus system. Since MAb E5/G6 binds to the linear cross-reactive epitope at aa 166 to 175 of NP (28), it was used as the detecting antibody.

As shown in Fig. 1a, whole and truncated rNPs of HTNV, SEOV, DOBV, and PUUV were expressed at approximately the expected sizes. Although the number of deduced amino acids of DOBV rNP50 was the same as those of HTNV rNP50 and SEOV rNP50, DOBV rNP50 migrated more slowly than HTNV rNP50 or SEOV rNP50. This may have been because of structural differences in DOBV rNP50.

FIG. 1.

Reaction patterns of the rNPs to the MAb E5/G6 and rabbit immune sera in Western blotting. The rNPs were separated by electrophoresis and blotted onto a membrane and were detected with various antibodies. (a) MAb E5/G6; (b) serum from an HTNV-infected rabbit. Lanes 1, HTNV whole rNP; lanes 2, SEOV whole rNP; lanes 3, DOBV whole rNP; lanes 4, PUUV whole rNP; lanes 5, HTNV rNP50; lanes 6, SEOV rNP50; lanes 7, DOBV rNP50; lanes 8, HTNV rNP155; lanes 9, SEOV rNP155; lanes 10, DOBV rNP155; lanes 11, Borna disease virus p24; lanes M, molecular mass markers.

The antigenic characteristics of whole and truncated rNPs were examined by their reactivities with immune serum from an HTNV-infected rabbit (Fig. 1b). The immune serum strongly cross-reacted with the whole rNPs of HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV, because the immunodominant and linear epitopes of NP were cross-reactive epitopes (5). Neither rNP50s nor rNP155s were detected in Western blotting, since the immunodominant and linear epitopes of NP are located at the N terminus of NP (6, 7, 26). The reactivity patterns of immune sera from SEOV- or DOBV-infected rabbits were the same as those of immune serum from HTNV-infected rabbits (data not shown). These results indicated that truncation of 49 aa at the N terminus of the NP reduced cross-reactivity to the same degree as truncation of 154 aa at the N terminus of the NP in Western blotting.

The whole rNP of PUUV showed strong reactivity only with immune serum from a PUUV-infected rabbit (data not shown). Thus, the antigenicity of the PUUV NP was distinct from those of the HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV NPs.

(ii) IFA test.

To examine the usefulness of the truncated rNPs for serotyping the reactivities of the truncated rNPs to rabbit immune sera were compared with the reactivities of whole rNPs by the IFA test (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Reactivities of rabbit immune sera to authentic virus and rNPs

| Antibody measurement and antigen | Value for rabbit immune serumc

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| anti-HTNV | anti-SEOV | anti-DOBV | anti-PUUV | |

| NT titera | ||||

| HTNV | 128 | 32 | 32 | <32 |

| SEOV | 64 | >1,024 | 32 | <32 |

| DOBV | 32 | 128 | 256 | <32 |

| PUUV | <32 | 32 | <32 | 512 |

| IFA titerb | ||||

| HTNV whole rNP | 16,384 | 16,384 | 16,384 | 1,024 |

| SEOV whole rNP | 16,384 | 16,384 | 8,192 | 1,024 |

| DOBV whole rNP | 8,192 | 16,384 | 16,384 | 1,024 |

| PUUV whole rNP | 128 | 2,048 | 2,048 | 4,096 |

| HTNV rNP50 | 2,048 | 4,096 | 1,024 | 128 |

| SEOV rNP50 | 1,024 | 8,192 | 512 | 128 |

| DOBV rNP50 | 512 | 4,096 | 4,096 | 256 |

| HTNV rNP155 | 128 | <32 | 32 | <32 |

| SEOV rNP155 | <32 | 128 | 32 | <32 |

| DOBV rNP155 | 32 | <32 | 512 | <32 |

Reciprocal of the highest serum dilution resulting in >80% reduction in the number of infected foci.

Reciprocal end point titer.

Titers of homologous antigen and antiserum are underlined.

The whole rNPs, except for the PUUV whole rNP, cross-reacted equally with immune sera from HTNV-, SEOV-, and DOBV-infected rabbits. The rNP50s retained one-eighth to one-half as much cross-reactivity to heterologous antibodies as to their homologous titers. Although the cross-reactivity of rNP155s decreased similarly to the NT titer, the homologous IFA titers to rNP155s decreased only to 1/128 to 1/32 compared to the homologous titers to whole rNPs, as previously reported (13). These results show that IFA using truncated rNPs is not a suitable method for serotyping hantavirus infections.

(iii) ELISA.

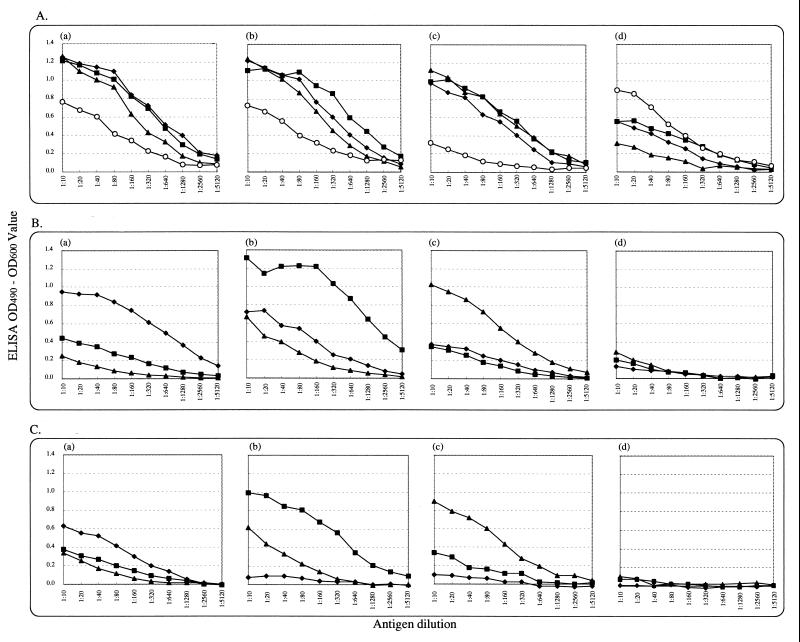

Figure 2 shows the reactivities of twofold dilutions of rNPs to a constant amount (1:200 dilution) of antibodies from HTNV-, SEOV-, DOBV-, or PUUV-infected rabbits. By ELISA, the whole rNP of PUUV showed a significant antigenic difference from the others, while HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV whole rNPs demonstrated high cross-reactivities (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Reaction patterns of rNPs with rabbit immune sera in ELISA. (A) Whole rNPs; (B) rNP50s; (C) rNP155s. HTNV (⧫), SEOV (■), DOBV (▴), and PUUV (○) rNPs were used. Each antigen was diluted from 1:10 to 1:5,120 and subjected to capture ELISA (see Materials and Methods). Capture antigens were detected with various rabbit immune sera: (a) anti-HTNV; (b) anti-SEOV; (c) anti-DOBV; (d) anti-PUUV. All sera were diluted to 1:200.

The optical density (OD) values with homologous antiserum were nearly the same using rNP50s as with whole rNPs, while the reactivities to heterologous sera decreased significantly (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, when using truncated rNP155s, SEOV rNP155 and DOBV rNP155 showed serotype-specific reaction patterns, while the antigenic properties of HTNV rNP155 significantly decreased (Fig. 2C). The low antigenicity of HTNV rNP155 has been reported previously (13). These results indicate that to differentiate PUUV infection from HTNV, SEOV, or DOBV infection, ELISA using whole rNPs is sufficient, and for differentiating HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV infections from each other, ELISA using rNP50s is applicable.

Reactivities of rNP50s with representative patient sera.

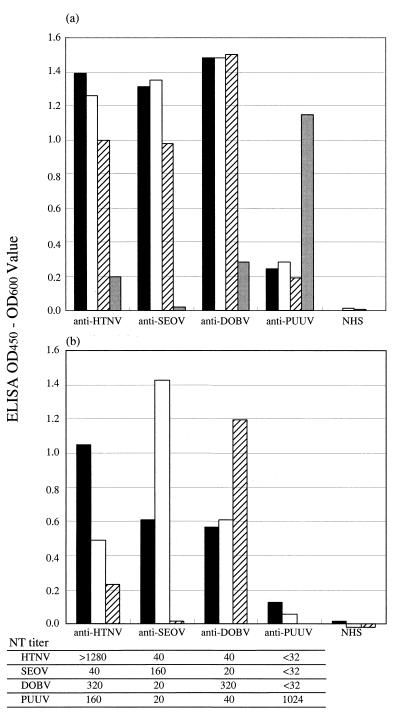

To examine the applicability of the rNP50 ELISAs for differentiating human sera, the reactivities with whole rNPs and rNP50s were compared using a representative patient serum specimen of each serotype. Using whole rNPs, only the PUUV infection was differentiated from HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV infections (Fig. 3a).

FIG. 3.

Reaction patterns of representative HFRS patient sera in ELISA. Anti-HTNV, patient serum obtained from China; anti-SEOV, patient serum obtained from Korea; anti-DOBV, patient serum obtained from Bosnia; anti-PUUV, patient serum obtained from Sweden; NHS, uninfected human serum from Japan. The serotypes of the four representative sera were differentiated by the NT; the results are summarized in the lower table. (a) whole rNP; (b) rNP50. Solid bars, HTNV rNP; open bars, SEOV rNP; hatched bars, DOBV rNP; shaded bars, PUUV rNP. All sera were diluted to 1:200. All antigens were diluted to 1:10. OD450, OD at 450 nm.

Using the rNP50s, serotype-specific reaction patterns were observed. The ELISA ODs were almost twice as high for the homologous reactions as for the heterologous reactions (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that ELISA using rNP50s is applicable for serotyping human HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV infections.

Diagnosis of groups of sera from hantavirus-infected patients.

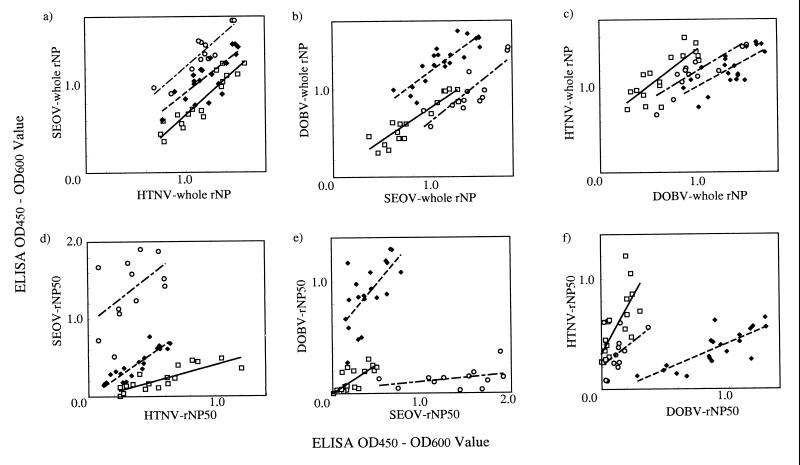

Sera from 49 patients previously diagnosed by the NT (17 HTNV-infected patients from China, 12 SEOV-infected patients from Korea or Japan, and 20 DOBV-infected patients from Bosnia or Estonia) were subjected to ELISA, using whole rNPs or rNP50s. Plots of the ELISA ODs at a serum dilution of 1:200, as determined previously (13), are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Reactivities of groups of sera from hantavirus-infected patients in ELISA. The horizontal and vertical axes show the ODs at 450 to 600 nm (OD450 to OD600) for the sera from HTNV-infected patients (□), SEOV-infected patients (○), and DOBV-infected patients (⧫) for each antigen. ELISA ODs were compared as follows: (a) HTNV whole rNP versus SEOV whole rNP; (b) SEOV whole rNP versus DOBV whole rNP; (c) DOBV whole rNP versus HTNV whole rNP; (d) HTNV rNP50 versus SEOV rNP50; (e) SEOV rNP50 versus DOBV rNP50; and (f) DOBV rNP50 versus HTNV rNP50. The lines are the linear regression for each group of sera: solid line, sera from HTNV-infected patients; dashed line, sera from SEOV-infected patients; broken line, sera from DOBV-infected patients.

With whole rNPs, the ODs of each group of sera correlated well with any combination of antigens, such as HTNV versus SEOV, SEOV versus DOBV, or DOBV versus HTNV (Fig. 4a, b, and c), and the slopes of the regression lines were similar. Furthermore, the areas of distribution of the different groups overlapped.

On the other hand, with the rNP50s, the slopes of the regression lines differed among the groups because each group of sera had higher ODs with the homologous rNP50s. Positive results of serotyping were defined as follows. Tentatively, when the ratio of the OD of a serum to SEOV or DOBV rNP50 to the OD of a serum to HTNV rNP50 was <0.7, the serum was deemed to be from an HTNV-infected human (positive result). Sixteen out of 17 sera (94%) from HTNV-infected patients had positive results. Similarly, when the ratio of the OD of a serum to DOBV or HTNV rNP50 to the OD of a serum to SEOV-rNP50 or the ratio of the OD of a serum to HTNV or SEOV rNP50 to the OD of a serum to DOBV-rNP50 was <0.7, the serum was deemed to be from an SEOV or DOBV-infected human (positive result), respectively. All 12 sera from SEOV-infected patients and 19 out of 20 sera from DOBV-infected patients (100 and 95%, respectively) had positive results. In addition, there were no errors of judgment.

DISCUSSION

At present, the virus neutralization assay is the only method to differentiate the hantavirus serotype specificities of immune sera (4, 12, 15). In this study, we investigated the application of N-terminally truncated rNPs from three related hantavirus species (HTNV, SEOV, and DOBV) as antigens in serodiagnosis. Truncated rNPs lacking 49 aa at their N termini (rNP50) were found to be able to differentiate HTNV-, SEOV-, and DOBV-specific immune sera in ELISA (but not in Western blots or IFA tests). In addition, we confirmed that whole rNPs were able to differentiate only PUUV-immune sera. Therefore, screening by ELISA using whole rNPs followed by serotyping using the truncated rNP50s can be recommended as a rapid and practical system for hantavirus seroepidemiology.

We previously reported that conformation-dependent, serotype-specific epitopes on the NP are located in the 200 aa of the C-terminal end (13, 28). It is thought that HTNV rNP155 lost these conformation-dependent epitopes as a result of truncating 154 aa from the N-terminal region of the NP. Therefore, it seems to be necessary to minimize the truncated region to retain the conformation of the NP and thereby increase the reactivity of these epitopes. The major linear epitopes on the NP are reported to be located at the N terminus (6, 7, 26). Therefore, we tried to apply truncated rNPs that lacked only a minimal region and prepared rNP50s to retain this conformation. As shown in Table 1, the rNP50s retained reactivity with the MAbs C16D11 and F23A1, both of which recognize conformation-dependent, cross-reactive epitopes (13, 28). In addition, since the rNP50s lacked reactivity in Western blotting with rabbit immune serum and reacted in IFA tests with rabbit immune serum, the major epitopes of the rNP50s were considered to be conformation dependent. As expected, compared to the rNP155s, all the rNP50s retained higher reactivity with polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 2). These results indicate that the rNP50s are suitable for ELISA while the rNP155s are not.

The structural heterogeneity of the rNPs was shown by Western blot analysis; the DOBV rNP50 migrated more slowly than the other rNP50s, although it possessed the same number of amino acids. This may have been caused by structural differences in the DOBV rNP50, because the cDNA construct of the DOBV rNP50 was confirmed to be identical to the original sequence. In addition, the HTNV rNP155 showed stronger doublet bands at 35 kDa than the SEOV rNP155 or DOBV rNP155. Since baculovirus-expressed recombinant hantavirus NP is highly sensitive to cellular protease (25), the difference in the doublet bands might have reflected conformational heterogeneity, which influenced the sensitivity to proteases.

This study with selected MAbs indicated that the DOBV NP is antigenically closely related to the NPs of HTNV and SEOV, as previously reported (8, 24). We could not show the existence of a DOBV-specific epitope on the NP directly, because of the absence of a DOBV-specific MAb. However, the DOBV NP obviously possesses certain serotype-specific epitopes, as indicated by the specific reactivity patterns of polyclonal immune sera.

In this study, there were not many acute-phase sera (only 7 of 49 sera). Further studies that include larger panels of acute-phase sera from various HFRS patients are needed to evaluate whether the rNP50s will also be useful for differentiating the causative hantavirus serologically during the early phase of the disease.

Reverse transcriptase PCR using specific primer pairs has been reported as a serotyping method (1). Generally, the specificity of PCR is quite high, and sequencing information provides a definite comparison without isolating the actual virus. However, although highly sensitive nested reverse transcriptase PCR has been established, only about two-thirds of HFRS patients infected with PUUV, and about one-half of HFRS patients infected with DOBV, are viral RNA positive on admission to the hospital (17–19). In addition, serologic diagnosis by ELISA with rNPs is rapid, simple, and inexpensive. Furthermore, it can be used for retrospective analysis. The combination of efficient serologic and genetic procedures will contribute to better control and prevention of hantavirus infections in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports of Japan, the Swedish Medical Research Council (projects 12177 and 12642), and the European Community (contract BMH4-CT97-2499).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn C, Cho J T, Lee J G, Lim C S, Kim Y Y, Han J S, Kim S, Lee J S. Detection of Hantaan and Seoul viruses by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) in renal syndrome patients with hemorrhagic fever. Clin Nephrol. 2000;53:79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arikawa J, Lapenotiere H F, Iacono C L, Wang M L, Schmaljohn C S. Coding properties of the S and the M genome segments of Sapporo rat virus: comparison to other causative agents of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Virology. 1990;176:114–125. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90236-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calisher C H. Bunyaviridae. In: Francki R I B, Fauquet C M, Knudson D L, Brown F, editors. Classification and nomenclature of viruses. Fifth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 273–283. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu Y K, Rossi C, Leduc J W, Lee H W, Schmaljohn C S, Dalrymple J M. Serological relationships among viruses in the Hantavirus genus, family Bunyaviridae. Virology. 1994;198:196–204. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elgh F, Lundkvist Å, Alexeyev O A, Stenlund H, Avsic-Zupanc T, Hjelle B, Lee H W, Smith K J, Vainionpaa R, Wiger D, Wadell G, Juto P. Serological diagnosis of hantavirus infections by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay based on detection of immunoglobulin G and M responses to recombinant nucleocapsid proteins of five viral serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1122–1130. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1122-1130.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elgh F, Lundkvist Å, Alexeyev O A, Wadell G, Juto P. A major antigenic domain for the human humoral response to Puumala virus nucleocapsid protein is located at the amino-terminus. J Virol Methods. 1996;59:161–172. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(96)02042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gott P, Zoller L, Darai G, Bautz E K F. A major antigenic domain of hantaviruses is located on the aminoproximal site of the viral nucleocapsid protein. Virus Genes. 1997;14:31–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1007983306341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kallio-Kokko H, Lundkvist Å, Plyusnin A, Avsic-Zupanc T, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O. Antigenic properties and diagnostic potential of recombinant Dobrava virus nucleocapsid protein. J Med Virol. 2000;61:266–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitamura T, Morita C, Komatsu T, Sugiyama K, Arikawa J, Shiga S, Takeda H, Akao Y, Imaizumi K, Oya A, Hashimoto N, Urasawa S. Isolation of the virus causing hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) using a cell culture system. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1983;36:17–25. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.36.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H W, Tkachenko E A, Ivanidze E A, Zangidullin I, Dekonenko A E, Niklasson B, Lundkvist Å, Avsic-Zupanc T, Childs J E, Bryan R T. Epidemiology and epizoology. In: Lee H W, Calisher C, Schmaljohn C, editors. Manual of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Seoul, Korea: WHO Collaborating Center for Virus Reference and Research (Hantaviruses) Asian Institute for Life Sciences; 1999. pp. 39–73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H W, Lee P W, Johnson K M. Isolation of the etiologic agent of Korean hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 1978;137:298–302. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundkvist Å, Hukic M, Horling J, Gilljam M, Nichol S, Niklasson B. Puumala and Dobrava viruses cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Bosnia-Herzegovina: evidence of highly cross-neutralizing antibody responses in early patient sera. J Med Virol. 1997;53:51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morii M, Yoshimatsu K, Arikawa J, Zhou G-Z, Kariwa H, Takashima I. Antigenic characterization of Hantaan and Seoul virus nucleocapsid proteins expressed by recombinant baculovirus: application of a truncated protein, lacking an antigenic region common to the two viruses, as a serotyping antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2514–2521. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2514-2521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemirov K, Vapalahti O, Lundkvist Å, Vasilenko V, Golovljova I, Plyusnina A, Niemimaa J, Laakkonen J, Henttonen H, Vaheri A, Plyusnin A. Isolation and characterization of Dobrava hantavirus carried by the striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius) in Estonia. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:371–379. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-2-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niklasson B, Jonsson M, Lundkvist Å, Horling J, Tkachenko E. Comparison of European isolates of viruses causing hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome by a neutralization test. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:660–665. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogino M, Yoshimatsu K, Tsujimura K, Mizutani T, Arikawa J, Takashima I. Evaluation of serological diagnosis of Borna disease virus infection using recombinant proteins in experimentally infected rats. J Vet Med Sci. 1998;60:531–534. doi: 10.1292/jvms.60.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papa A, Johnson A M, Stockton P C, Bowen M D, Spiropoulou C F, Alexiou-Daniel S, Ksiazek T G, Nichol S T, Antoniadis A. Retrospective serological and genetic study of the distribution of hantaviruses in Greece. J Med Virol. 1998;55:321–327. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199808)55:4<321::aid-jmv11>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plyusnin A, Horling J, Kanerva M, Mustonen J, Cheng Y, Partanen J, Vapalahti O, Kukkonen S K, Niemimaa J, Henttonen H, Niklasson B, Lundkvist Å, Vaheri A. Puumala hantavirus genome in patients with nephropathia epidemica: correlation of PCR positivity with HLA haplotype and link to viral sequences in local rodents. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1090–1096. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1090-1096.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plyusnin A, Mustonen J, Asikainen K, Plyusnina A, Niemimaa J, Henttonen H, Vaheri A, Horling J, Kanerva M, Cheng Y, Partanen J, Vapalahti O, Kukkonen S K, Niklasson B, Lundkvist Å. Analysis of Puumala hantavirus genome in patients with nephropathia epidemica and rodent carriers from the sites of infection. J Med Virol. 1999;59:397–405. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199911)59:3<397::aid-jmv21>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruo S L, Sanchez A, Elliott L H, Brammer L S, McCormick J B, Fisher H-S. Monoclonal antibodies to three strains of hantaviruses: Hantaan, R22, and Puumala. Arch Virol. 1991;119:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01314318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmaljohn C, Hjelle B. Hantaviruses—a global disease problem. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:95–104. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmaljohn C S, Jennings G B, Hay J, Dalrymple J M. Coding strategy of the S genome segment of Hantaan virus. Virology. 1986;155:633–643. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmaljohn C S, Sugiyama K, Schmaljohn A L, Bishop D H. Baculovirus expression of the small genome segment of Hantaan virus and potential use of the expressed nucleocapsid protein as a diagnostic antigen. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:777–786. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-4-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sjolander K B, Lundkvist Å. Dobrava virus infection: serological diagnosis and cross-reactions to other hantaviruses. J Virol Methods. 1999;80:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(99)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vapalahti O, Lundkvist Å, Kallio-Kokko H, Paukku K, Julkunen I, Lankinen H, Vaheri A. Antigenic properties and diagnostic potential of Puumala virus nucleocapsid protein expressed in insect cells. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:119–125. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.119-125.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada T, Hjelle B, Lanzi R, Morris C, Anderson B, Jenison S. Antibody responses to Four Corners hantavirus infections in the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus): identification of an immunodominant region of the viral nucleocapsid protein. J Virol. 1995;9:1939–1943. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1939-1943.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimatsu K, Arikawa J, Kariwa H. Application of a recombinant baculovirus expressing hantavirus nucleocapsid protein as a diagnostic antigen in IFA test: cross reactivities among 3 serotypes of hantavirus, which causes hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55:1047–1050. doi: 10.1292/jvms.55.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshimatsu K, Arikawa J, Tamura M, Yoshida R, Lundkvist Å, Niklasson B, Kariwa H, Azuma I. Characterization of the nucleocapsid protein of Hantaan virus strain 76–118 using monoclonal antibodies. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:695–704. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-4-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshimatsu K, Arikawa J, Yoshida R, Li H, Yoo Y C, Kariwa H, Hashimoto N, Kakinuma M, Nobunaga T, Azuma I. Production of recombinant hantavirus nucleocapsid protein expressed in silkworm larvae and its use as a diagnostic antigen in detecting antibodies in serum from infected rats. Lab Anim Sci. 1995;45:641–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]