Abstract

Objectives

Primary care is well positioned to identify and address loneliness and social isolation in older adults, given its gatekeeper function in many healthcare systems. We aimed to identify and characterise loneliness and social isolation interventions and detect factors influencing implementation in primary care.

Design

Scoping review using the five-step Arksey and O’Malley Framework.

Data sources

MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, COCHRANE databases and grey literature were searched from inception to June 2021.

Eligibility criteria

Empirical studies in English and Spanish focusing on interventions addressing social isolation and loneliness in older adults involving primary care services or professionals.

Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted data on loneliness and social isolation identification strategies and the professionals involved, networks and characteristics of the interventions and barriers to and facilitators of implementation. We conducted a thematic content analysis to integrate the information extracted.

Results

32 documents were included in the review. Only seven articles (22%) reported primary care professionals screening of older adults’ loneliness or social isolation, mainly through questionnaires. Several interventions showed networks between primary care, health and non-healthcare sectors, with a dominance of referral pathways (n=17). Two-thirds of reports did not provide clear theoretical frameworks, and one-third described lengths under 6 months. Workload, lack of interest and ageing-related barriers affected implementation outcomes. In contrast, well-defined pathways, collaborative designs, long-lasting and accessible interventions acted as facilitators.

Conclusions

There is an apparent lack of consistency in strategies to identify lonely and socially isolated older adults. This might lead to conflicts between intervention content and participant needs. We also identified a predominance of schemes linking primary care and non-healthcare sectors. However, although professionals and participants reported the need for long-lasting interventions to create meaningful social networks, durable interventions were scarce. Sustainability should be a core outcome when implementing loneliness and social isolation interventions in primary care.

Keywords: primary care, geriatric medicine, social medicine, organisation of health services, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first scoping review providing an overview of the role and characteristics of primary care-based interventions to identify and address loneliness and social isolation in older adults living in the community.

This study followed rigorous methods, including a comprehensive search of multiple databases and grey literature and systematic study selection, data charting and collation.

Relevant articles might not have been identified during the screening phase if primary care was not labelled according to the key terms contained in the search strategy, under-representing regions without primary care or with differently defined first levels of care.

This scoping review is limited to peer-reviewed empirical studies in Spanish and English and only includes one grey literature record which met eligibility criteria and, therefore, the results are not representative of all countries.

Introduction

Loneliness and social isolation are public health issues that gained global attention during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns.1 The two concepts are closely related yet reflect distinct psychosocial processes. Loneliness is defined as an unpleasant emotional state resulting from the perception of insufficient social relationships, either in quantity or quality.2 Loneliness implies a subjective and negative experience product of a mismatch between the existing and the desired social connections.3 In contrast, social isolation reflects an objective absence or a scant number of social relationships with other people. Thus, socially isolated individuals might not experience loneliness if the lack of relations aligns with their desires and expectations. Similarly, a person can feel lonely independently of the number of connections if this number is not quantitatively or qualitatively desirable.3 Despite being independent constructs, loneliness and social isolation are often studied simultaneously in health research, given their similar detrimental effects on health outcomes.4 5 Recent studies found that adults experiencing loneliness and social isolation have a likelihood of mortality increased by 29% and 26%, respectively,6 and are at higher risk of cardiovascular and mental diseases.7–9

Older adults are especially prone to loneliness and social isolation.10 Estimates of the prevalence vary depending on measurement methods and countries, ranging from >13% in the UK,11 and 18.6% in Canada,12 to 25% in the USA.13 14 Recent reviews indicated that ageing-related events such as the loss of a partner, friends or relatives, or health impairments, including hearing loss and functional limitations, are associated with a decrease in social relationships, leading to a higher risk of loneliness and social isolation.15–17 In addition, income and living conditions influence loneliness and social isolation. The prevalence of loneliness in older adults living in poor households is 10% higher than that of those living in higher-income households, according to a survey of 14 European countries.18 In contrast, living with ≥2 people has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of loneliness (OR: 0.39, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.47).18 Similar patterns have been reported for social isolation, living arrangements and income.19 Other studies linked social isolation with limited availability of social activities or transportation,19 less social support12 and living in less cohesive communities, defined as the extent of connectedness and solidarity among social groups.20 The presence of multiple typologies of risk factors suggests that loneliness and social isolation are social problems that may require comprehensive responses and synergic collaboration between health and non-health sectors. However, theoretical approaches guiding loneliness and social isolation interventions have been claimed to be heterogeneous, with the risk of conveying conceptual inconsistencies.21

Primary care professionals (ie, family physicians, primary community and nurse practitioners and social workers) often provide first-level care and are well situated to reach out to lonely and socially isolated individuals.22 23 In countries with a national healthcare system including primary care, such as Spain or the UK, citizens are registered in primary care centres and have lifelong follow-up,24 25 allowing primary care professionals to identify social, physical and mental factors associated with loneliness and isolation in their assigned population during routine consultations.26 Moreover, long-lasting therapeutic relations with primary care professionals might motivate older adults to continue visiting primary care services despite being socially isolated or lonely, in some cases as a point of social contact.22 However, our preliminary search indicated that primary care professionals' screening for loneliness and social isolation in older adults may be limited,27 28 partially due to uncertainty about how to proceed after lonely and isolated persons are identified.29

While identifying loneliness and social isolation in primary care settings is crucial, clinical and public health interventions must be available after detection.30 Strengthening primary care collaboration with other health and non-healthcare sectors has been widely proposed to address factors leading to social isolation and loneliness.22 23 30 For instance, a recent report from the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine recommended further implementation of evidence-based loneliness and social isolation assessment, prevention and interventions by healthcare professionals, enabled by more robust integration between primary care and community sectors.30 Establishing connections between primary care and other health (ie, specialised care) and non-healthcare sectors (ie, third sector organisations, volunteer groups) could allow primary care professionals to complement medical treatments with additional resources to strengthen older adults’ social networks31 32 or respond to underlying medical problems (ie, hearing loss limiting sociability).33 34 Despite rising interest in these new approaches, the National Academies report emphasised that researchers are at the onset of comprehending how loneliness and social isolation interventions work.30

Primary care interventions to identify and address loneliness and social isolation in older adults may vary between regions. In addition, collaboration configurations between primary care and other health and non-healthcare sectors vary depending on contextual aspects, such as the characteristics of the primary care system or the availability of resources.35 This translates into the use of multiple definitions to refer to these configurations, such as social prescribing pathways36 or asset-based community projects37 in the UK or structured referral pathways in Canada.38 Understanding how primary care professionals identify these social problems and the characteristics of interventions integrating primary and other sectors when addressing loneliness and social isolation is crucial to inform current and future interventions. Previous research synthesis in this field focused on general descriptions of intervention activities and outcomes, with no focus on the role of primary care in addressing them.15 39–44 To fill this research gap, we propose a systematic scoping review of the current research base in primary care-based loneliness and social isolation interventions. In particular, we aim to understand the strategies used by primary care professionals to identify loneliness and social isolation, to describe the characteristics of primary care-based interventions, and to detect facilitators and barriers influencing their implementation. The following research questions guided our review: (1) What is the literature on strategies used to identify loneliness and social isolation among older community dwellers in interventions involving primary care services?; (2) what are the characteristics of existing interventions involving primary care services and other health/non-healthcare sectors to address social isolation and loneliness among older community dwellers? and (3) what facilitators and barriers affect the implementation of loneliness and social isolation interventions in primary care settings?

Methods

We followed the five-step Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework:45 identifying the research questions, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data and collating, summarising and reporting the results. In addition, we used the population, concept and context approach46 when developing the research questions and search strategy, whereby the population refers to older adults, concept to loneliness and social isolation, and context to primary care settings. A protocol containing the rationale, objectives, research questions, and detailed methods of the review was developed between June and August 2020, and prospectively registered in Open Science Framework.

Definitions

We defined primary care based on the UK or Spanish models as the frontline entry to healthcare, such as primary care, community centres, general practice, home care and community pharmacies.47–49 We adopted the generic term non-healthcare sectors to encompass all resources or organisations supporting loneliness and social isolation interventions outside primary care or healthcare systems. Older community-dwellers (hereafter older adults) were defined as non-institutionalised or hospitalised persons aged >60 years.50

To understand how primary care professionals identify loneliness and social isolation in older adults, we focused on determining which primary care professionals are involved in identifying them and the methods used (ie, scales). To study the characteristics of the interventions, we focused on data describing the arrangement of elements within the intervention (hereafter networks), namely, the sectors involved and the pathways used by professionals (ie, referrals from primary care to community organisations). In addition, we studied how stakeholders generated these networks between sectors, and we captured crucial intervention evaluation elements recommended by the National Academies,30 such as the theoretical frameworks underpinning the interventions, sustainability and strategies for data sharing between sectors.

Identifying relevant studies

We searched four databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, COCHRANE reviews) using MeSH terms and keywords related to the components of the research question. First, we detected key terms and synonyms by analysing relevant papers in Yale Mesh Term Analyzer51 to develop an initial search in MEDLINE. A research collaborator from the University of Toronto library verified the comprehensiveness of the search strategy. Next, we adapted the search strategy to the databases following an advanced literature search sheet.52 Finally, we conducted a hand search on Google using the key terms loneliness, social isolation and primary care to identify grey literature. To fully capture the extent of the literature, time restrictions were not applied. The literature search was initially conducted from June to August 2020, with an update in June 2021. The complete search strategy is included in online supplemental material 1.

bmjopen-2021-057729supp001.pdf (61.9KB, pdf)

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were assessed by two reviewers. We included empirical studies in English and Spanish focusing on interventions to address older adults social isolation and loneliness involving primary care services or professionals, exclusively or in coordination with other sectors and workers, such as specialised care, outpatient clinics or Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). We excluded interventions delivered outside these settings or not provided by primary care professionals (ie, solely offered by NGOs, social clubs, or academic researchers), involving institutionalised adults, or theoretical studies and commentaries. To ensure rigour during the screening phase, we screened titles and abstracts, followed by the full text, using COVIDENCE software,53 after carrying out a pilot test to detect potential inconsistencies when applying eligibility criteria. The pilot test comprised (1) an independent screening by two reviewers of a set of one hundred records yielded from the search, (2) an assessment of discrepancies on the number of records included and excluded, (3) a final meeting to discuss potential inconsistencies and doubts concerning eligibility criteria.

Charting the data, collating, summarising and reporting the results

Data extraction followed an iterative process as the charting table was updated if additional unforeseen data was found.46 The charting table included descriptive data including title/authors, year of publication, country of origin, study design/setting/aim, study population and sample size and key findings. The key findings section contained three columns related to (1) loneliness or social isolation identification strategies (ie, tools used and role of primary care professionals involved), (2) intervention characteristics (ie, type of health and non-healthcare sectors, strategies to create connections between sectors, pathways used by primary care professionals, data sharing between sectors, theoretical aspects and intervention duration) and (3) facilitators and barriers (factors promoting or hindering implementation outcomes). We used qualitative content analytical techniques,54 involving transferring the charted data into a database and assigning codes according to distinct units of meaning, grouping data with similar codes into categories, and integrating multiple categories into themes. For instance, data on the type of sectors involved in the interventions coded as ‘only primary care involved’, ‘connection between health and non-health sectors’, and ‘connection between healthcare sectors’, were grouped into a category named ‘sectors and pathways’. Finally, we integrated the categories into themes that addressed the proposed research questions.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or public were involved in the study. No ethical approval was needed because data were collected from previously published studies in which informed consent was obtained.

Results

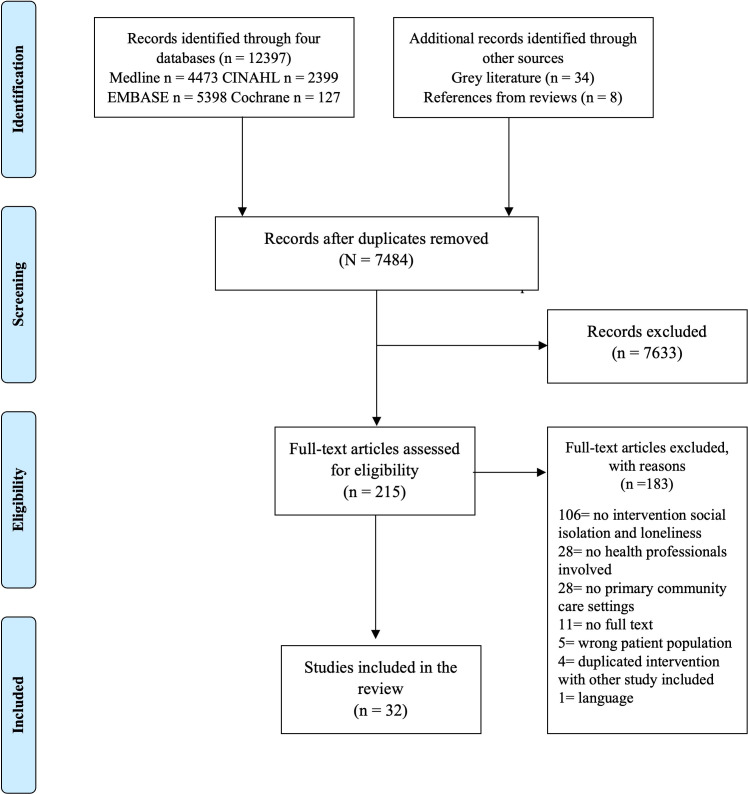

The search strategy yielded 12 397 papers, 34 reports and 8 articles from literature review references. After removing duplicates, 7848 document titles and abstracts were screened, and 215 records were eligible for full-text screening. Finally, we included 32 articles for the reasons shown in figure 1. Twenty-eight per cent of the studies (n=9) were conducted in the UK (table 1). Eighty-eight per cent (n=28) were published between 2014 and 2021. All studies included primary data and mostly followed quantitative, non-Randomized Controlled Trials, and mixed-method methodologies. Twenty studies (63%) exclusively focused on social isolation or loneliness, while the rest addressed these issues in addition to other geriatric conditions (ie, risk of falls, sensory impairments, urinary incontinence).34 A chart with detailed data for each article is available in online supplemental material 2.

Figure 1.

Study inclusion flow chart, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA checklist).

Table 1.

Characteristics of reports included (n=32)

| Characteristics | n of studies included n (%) |

| Country | |

| UK | 9 (28) |

| Spain | 6 (19) |

| USA | 6 (19) |

| Netherlands | 4 (13) |

| Finland | 2 (6) |

| Croatia, Holland, Iran, Sweden, Canada* | 5 (15) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2018–2021 | 20 (63) |

| 2014–2017 | 8 (25) |

| 2009–2013 | 4 (13) |

| Study design | |

| Non-RCT quantitative designs (quasi-experimental, transversal) | 11 (34) |

| Mixed-method | 11 (34) |

| Qualitative designs | 5 (16) |

| RCT | 5 (16) |

*One study per country.

RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial.

bmjopen-2021-057729supp002.pdf (97.4KB, pdf)

Strategies used to identify loneliness and social isolation among older adults in primary care services

Only seven articles (22%) reported strategies to identify loneliness or social isolation in older adults during the recruitment phases of the interventions.55–61 The strategies comprised the administration of questionnaires to potential participants with a single screening loneliness item (n=4), asking individuals ‘do you feel lonely?’ during clinical encounters with primary care professionals (n=1), administering a loneliness scale (n=1), and searching for lonely and socially isolated patients in medical records using keywords (n=1). Most studies (n=26, 81%) did not report loneliness and social isolation assessments to identify potential participants. Instead, in 13 studies (41%), individuals were invited to participate in loneliness and social isolation interventions based on the presence of risk factors (ie, age >65 years, living alone, consultation gaps). Complementary strategies to recruit socially isolated and lonely patients included advertising posters55 and leaflets31 62 63 distributed within primary healthcare facilities.

In contrast, 44% of studies reported using loneliness and social isolation scales and questionnaires after older adults were enrolled for baseline and follow-up measurements. Five validated instruments were used to measure loneliness and two with social isolation as outcomes. The remaining 14 articles described various methods, including semistructured interviews64 and questionnaires.63 The detection method was not reported in seven studies because participants were recruited from existing interventions or for unknown reasons (table 2).

Table 2.

Strategies used to identify loneliness and social isolation among older adults in primary care services

| Detection strategies | Loneliness | Social isolation |

| Scales | UCLA†*31 36 59 60 67 79

71 De Jong Gierveld*65 77 |

DUKE UNC*31 72 Lubben’s Social Network Scale*59 |

| Tilburg Frailty indicator (loneliness sub item)*65 68 | ||

| Campaign to End Loneliness Tool*38 | ||

| INQ-Belong*56 | ||

| Item in a questionnaire | ‘Do you feel lonely nowadays?’ (yes very, yes rather, no I don’t)*63 Feeling lack of companionship†61 ‘I feel lonely (yes/no)’†56 |

Have problems related to social isolation*64 Self-reported involvement in social activities community belonging*38 |

| ‘Do you suffer from loneliness?’†58 59 | ||

| Question during clinical encounter | ‘Do you feel lonely?’†55 | |

| Electronic medical records | Search lonely patients in EMR†57 | Search isolated patients in EMR†57 |

| Indirect strategies | Inviting older adults age >60†26 31 60 65 67 68 74 | Older adults with low mobility, architectural barriers†32 70 |

| Considering at risk older adults living alone†61 74 | Attending mental health services†75 | |

| Consultation gap >3 years†34 | ||

| Physical limitations, low income, mild mental disabilities or recently widowed†62 | ||

| Not disclosed | 33 36 38 66 69 71 73 78 |

*Assessment of loneliness and social isolation as outcome measure of the study during the interventions.

†Identification strategies to recruit older adults for loneliness and social isolation interventions.

EMR, Electronic Medical Record; INQ, Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire; UCLA, University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale.

Family physicians,26 34 55 57 60 65 66 primary care nurses,36 55 59 60 67 68 and social workers,55 69 identified lonely and socially isolated adults in the recruiting phases of the interventions. The nonspecific term ‘primary care teams’ was used in two studies.32 61 63 70–72 Six studies reported that family physicians,36 62 64 73 nurse practitioners,31 64 social workers,31 pharmacists31 and primary care teams74 referred participants from primary care to other settings without providing information about identification strategies.

Characteristics of primary care-based interventions to address social isolation and loneliness among older community dwellers

Sectors and pathways

Sixty-six per cent of the articles (n=21) reported interventions involving multiple health and non-healthcare sectors. The most prevalent pattern (n=17, 53%) consisted of referral pathways, including community referral pathways,55 social prescribing prescribing73 75 and care-pathways65 that linked primary care and non-healthcare interventions (table 3). A range of terms were used to define non-healthcare sectors, such as community resources or community organisations,73 local community assets38 55 71 and social groups.36 Through these pathways, primary care professionals identified and referred older adults experiencing loneliness, social isolation or related risk factors to non-healthcare sectors such as community resources or volunteering (table 4). In five studies (16%), the referral pathways included a proxy, that is, link workers,36 social prescribing coordinators73 and navigators38 who had in-depth knowledge of community resources and connected participants with tailored resources based on their needs, provided follow-up,71 or delivered health education.64 In other instances (n=4, 12%), the studies described alternative non-referral pathways whereby external research or social organisations identified and enrolled lonely and isolated older adults from primary care settings.

Table 3.

Primary care-based loneliness and social isolation intervention pathways

| Referral pathways | Non-referral pathways |

| Primary care professionals refer older adults to a proxy worker, which connect them to non-healthcare sectors.36 38 64 71 73 | External agency recruited older adults from primary care settings, and paired them with volunteers.56 |

| Primary care professionals refer older adults directly to non-healthcare sectors.32 38 55 60 61 65 66 70 74 75 | Teams of community health and social care professionals connect hospital discharged adults to volunteers.78 |

| Primary care professionals refer older adults to an external organisation which connect them to non-healthcare sectors.31 62 68 | External researchers identify lonely older adults and connect them with primary care services that lead the interventions.58 79 |

| Primary care professionals refer older adults to other healthcare services.34 64 76 | No-network interventions, where primary care professionals identified lonely, isolated older adults and delivered the intervention in the same setting.26 57 59 63 69 77 |

Table 4.

Examples of sectors involved in primary care interventions

| Type | Examples |

| Non-healthcare sector | |

| Community resources and activities31 38 55 58 61 64 66 68 73 75 | Culture organisations, nature groups, senior services, sport and walking clubs, yoga groups, cookery lunch clubs, libraries, religious group, museums, neighbourhood associations, art-based and music groups, social and support groups, continuing education centres, welfare rights advice, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). |

| Volunteering32 38 56 61 70 78 | Companions for outdoor walks for low mobility adults, befrienders, peer companions, volunteering instructors on healthy habits and psychosocial aspects, Health Champions |

| Technology services26 33 74 77 | Telephone-based platform, communication platform through television, assessment software to enhance detection complex social needs. |

| Health sector | |

| Medical non-primary care services34 64 76 | Ophthalmologist services, audiometric specialists, adult day healthcare centres, mental health services, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, geriatric health services |

Primary care professionals linked older adults with other health resources in five studies (16%) after assessing high-risk individuals for multiple age-related chronic conditions, including loneliness.76 In the study by Bleijenberg et al primary care nurses conducted holistic geriatric assessments at home and referred lonely or isolated older adults to specialist services to address underlying medical factors (ie, hearing loss, lack of mobility).34 Five studies reported no-network interventions, where primary care professionals identified lonely, isolated older adults and delivered the intervention in the same setting.26 57 59 63 69 77

Theoretical approaches, network generation, sustainability and data sharing

Of the 32 interventions, 66% (n=21) did not provide clear theoretical underpinnings to justify the design of the intervention and the potential effects on lonely and socially isolated individuals. Eight studies (26%) used concepts related to loneliness and social isolation (ie, increase social cohesion or social support) to support their rationale, and only five provided theories (table 5).

Table 5.

Relevant aspects of primary care-based loneliness and social isolation interventions

| #DOC | |

| Intervention theoretical approaches | |

| Loneliness-social isolation related constructs. | |

| 78 | Enhance social network development. |

| 73 | Promote social integration and social reactivation. |

| 55 | Increase social cohesion. |

| 33 36 56 | Increase social connectedness. |

| 61 | Encourage participation in the community. |

| 60 | Increase social support. |

| Theories | |

| 55 | Social capital theory. |

| 62 | Van Tilburg network development theory. |

| 36 | The social cure framework. |

| 79 | Story theory and cognitive restructuring. |

| 38 | Model of health and well-being. |

| Creation of the networks | |

| 34 | Researchers, GPs, RNs, experts, and older persons designed intervention and network. |

| 55 | Coordinated action to strengthen network between primary care centres, senior centres and other community assets. |

| 38 | Community centres created or updated an asset map to compile community resources for social prescriptions. |

| 62 | A group including regional mental health service, regional community health service, local elderly welfare organisation, municipality developed intervention, informed by interviews with older adults, professionals, and policymakers. |

| 71 | Social prescribing space created via consultation with 20 organisations (ie, health, social care and charities working with the target population). |

| 64 | Network generated by consultation with patients and healthcare professionals over an 8 year period. |

| 33 36 65 | Networks between primary care and other settings already existent. |

| Reported intervention duration | |

| 57 | <1 month |

| 31 58 59 71 74 75 78 79 | 1–3 months |

| 60 61 66 | 3–6 months |

| 63 68 76 | 6 months −1 year |

| 34 38 64 72 73 | 1–2 years |

| 26 32 36 55 56 62 65 69 70 | >2 years |

| 33 67 77 | Unknown |

| Data sharing between sectors | |

| 34 38 | In person meetings to coordinate plans between RN, GP and other healthcare professionals. |

| 64 66 | Delivering physical referral forms with patient information link workers or to the coordinator of third sector organisations. |

| 31 65 74 | Healthcare professionals place data/referrals/consultations in shared electronic medical records. |

| 76 | RN Navigators introduce assessment and screening tools data into cloud database. |

GPs, general practitioners; RN, registered nurse.

Nine studies (28%) explained how the stakeholders generated the intervention networks to address social isolation and loneliness in older adults. These articles reported varied approaches, ranging from collaborations between primary care professionals and older adults34 to intersectoral partnerships between regional health services, municipalities, and welfare organisations62 (table 4).

The duration of the interventions ranged from 2 weeks to permanent interventions integrated in clinical practice for >2 years. The span of interventions in 12 studies (37%) was <6 months, with 9 (28%) lasting <3 months. The interventions were mainly pilot studies. In contrast the duration was >2 years in nine interventions (28%), which commonly reported follow-up evaluations. Financial and human resource shortages hindered the continuity of the intervention and their implementation in five studies,38 55 71 77 78 and one intervention was cancelled due to lack of funding.71 Eight studies (25%) reported shared electronic medical records or in-person communication information as data-sharing strategies between primary care professionals and non-healthcare sectors (table 5).

Factors affecting the implementation of loneliness and social isolation interventions in primary care services

Barriers

Primary care professionals’ workload was a barrier in four studies.(12%) Social isolation and loneliness interventions were perceived as time-consuming, given the time required to build trust with participants, design and apply the intervention, or train the people involved.34 65 Two studies reported challenges faced by professionals while taking on new interventions and existing workload amidst fast-paced clinical environments,36 38 prioritising diagnosis-treatment activities. In addition, family physicians experienced uncertainty about how to proceed after identifying loneliness if referral resources were unavailable.36 Similarly, workload-related barriers affected link workers in one study, where a high volume of referrals decreased the quality of social prescribing services.36 Centralising interventions around overburdened professionals endangered continuity due to potential turnover.38 In two studies, primary care professionals reported struggling to incorporate volunteers for social prescribing interventions due to a lack of interest.55 78

Barriers affecting patient participation were reported in nine studies (28%). First, misinformation about the referral process and the role of linking professionals confused patients affecting their engagement.73 Similarly, one study reported worse feedback from participants when primary care professionals lacked a proper understanding of the referral pathways.36 In three studies, socially isolated and lonely older adults expressed reluctance to engage in group activities based on discomfort when joining a group while not knowing anyone.36 57 69 Participating in large groups without facilitating staff hindered socialisation and deterred attendance.69 Age-related factors such as physical and mental health limitations affected participant engagement in five interventions.57 61 65 77 79

Organisational barriers affected intervention implementation in several studies. Two studies described a lack of fit between participant interests, session content and participants, leading to loss of interest and discontinuity in attendance.36 74 In another intervention, the authors acknowledged a lack of standardised or explicit strategies for addressing loneliness, which decreased effectiveness.63 Primary care professionals’ short time of involvement in one intervention hindered the generation of trust with participants, affecting participation rates and outcomes.78 Lack of transportation, intervention prices and lack of interconnected IT resources between sectors were described as barriers for older adults’ participation in one study.38 Two studies reported difficulties in delivering technology-based interventions, either due to user challenges or technology errors, affecting attendance.

Facilitators

Three studies reported that having existing pathways to connect patients with community assets facilitated the intervention’s success and increased early adoption as they gave primary care professionals the tools to address social isolation and loneliness once detected.36 60 65 In addition, interventions relying on existing networks consisting of primary care services, community resources and volunteers lowered costs and favoured sustainability.56 61 74 Other studies based on referral pathways highlighted that having closer access to link workers or programme coordinators (ie, working within primary care) increased their visibility among healthcare professionals and influenced the adoption of the intervention.31 34 36

In four studies, healthcare professionals and patients expressed the need for prolonged programmes to have more time to build social connections and trust relationships with other participants.33 60 64 66 For instance, Voegepoel and Jarrold extended the intervention for longer than the pre-established 12 weeks to promote the effect on social relations.66 Older adults reported benefits and increased participation due to extended sessions with the link workers because they could share their needs and be heard.36 Three studies reported that delivering affordable activities was crucial to ensure equal access to those activities.38 59 69 For example, in the communal table project, the €1 three-course dinner allowed equitable participation independently of socioeconomic position.69

A perceived fit with the activity content and group participants was crucial for older adults’ continuity in two studies. Engagement and outcomes improved when patients’ motivations and interests informed the design of the content.58 69 For instance, Howarth et al reported that collaborative approaches—involving organisation, healthcare professionals and patients—when creating the intervention network led to positive effects because it acknowledged lonely and socially isolated patients’ needs.71 Six studies also reported adapting the intervention to the participants’ physical and mental health conditions to ease access by arranging a place adapted to disabilities and sensory impairment;61 66 79 planning the activities with a proper frequency and duration;61 79 offering transportation or parking accommodation38 58 59 66 79 and sending periodic reminders before the intervention.66 79

In two studies, lonely and isolated older adults’ engagement in interventions increased when primary care nurses, link workers and volunteer neighbours participated, due to pre-established trust relationships.56 61 In addition, programme coordinators, link workers, and primary care professionals accompanied new participants to the groups to facilitate engagement and lessen fear when not knowing anyone.61 64 66 In four studies, participants highlighted how health professionals’ specific attributes, such as being warm, friendly or good listeners, helped build trust and favoured their adaptation to the intervention.38 61 64 79

Discussion

We provide an overview of aspects of primary care-based interventions to address social isolation and loneliness in older people. Loneliness and social isolation interventions with primary care participation have risen over the past 6 years. This may be due to the medicalisation of these social problems, motivated by recent studies linking loneliness and social isolation with higher mortality, worse health outcomes6 and international calls for responses from healthcare systems since 2015.23 30 We found that primary care professionals did not screen older adults’ loneliness and social isolation before enrolling them in most interventions. Instead, there was a significant reliance on risk factors (ie, older age, living alone) as inclusion criteria. We identified a predominant intervention configuration in which primary care networked with one or more health or non-healthcare sectors to deliver the interventions. The interventions reviewed presented heterogeneous configurations, theoretical approaches and duration across studies, partially reflecting a lack of well-established models to address loneliness and social isolation.30

While only seven interventions reported screening older adults’ social isolation and loneliness before joining an intervention, fourteen studies described the use of validated instruments to measure intervention outcomes. These results align with studies highlighting underscreening of these social problems27 29 and a tendency to enrol easy-to-reach adults to ease complications in recruiting isolated and lonely individuals.30 Referring older adults to loneliness intervention groups without an appropriate assessment might lead to confusion and negative experiences, such as a lack of fit with the activities or a clash with preferences to deal with loneliness and social isolation privately.80

We found that primary care professionals might perceive loneliness or social isolation assessments as a secondary duty. Similarly, in a recent qualitative study, family physicians acknowledged prioritising biomedical aspects over loneliness assessments due to work overload and limited time during clinical visits.29 Thus, underscreening of these social problems is seemingly motivated by structural barriers in primary care settings rather than a lack of measurement tools.81 In addition, previous qualitative studies found that older adults using primary care services might be reluctant to label themselves as lonely or isolated due to the associated stigma.80 82 Thus, there is a need to develop efficient identification strategies that do not interfere with clinical practice. Efforts should focus not only on screening, but also on ensuring continued follow-up for lonely and socially isolated older adults. Future strategies might involve identifying individuals at risk using machine-learning natural language processing algorithms that autonomously explore social isolation or loneliness keywords in electronic health records83 or through maps to detect areas with a higher risk of loneliness.84 However, these methods will require further consideration of ethical issues concerning autonomy or privacy before being broadly implemented in clinical practice.30

Two-thirds of the studies reported networks of primary care and one or more health or non-healthcare sectors to deliver the interventions, with referral pathways linking older adults from primary care to community resources, activities, or volunteering as the most common. This model is predominant given the high proportion of UK studies, where social prescribing schemes have been publicly funded since 2017.23 The high number of records adopting this approach aligns with international calls by the WHO and other international organisations to strengthen intersectoral collaborations by primary healthcare and non-health sectors to address population health and social needs.30 85 86 Despite this promising finding, we found that most interventions failed to provide theoretical justifications grounding the interventions. When reported, concepts and theories underpinning loneliness and social isolation varied across interventions. This heterogeneity hinders the interpretation of the results across studies, given the differences in assumptions and mechanisms of action when addressing loneliness and social isolation. Although some theories have been developed,82 87 loneliness and social isolation research in older age has no clear consensual theoretical framework.30 81 Further research might address the gap between theoretical models, clinical practice and public health programmes.

We also found high variability in intervention duration, ranging from 2 weeks to more than 2 years. This conflicts with the need for long-term interventions reported by older adults and professionals.60 Four studies indicated that longer interventions are required to effectively enhance older adults’ social networks, since building social connections and trusting relationships may be slow. Thus, achieving sustainability should be a core outcome of implementation efforts. Our findings align with reports showing that over-reliance on external funds, such as temporary grants, may limit the continuity of the interventions.88 In contrast, intersectoral networks connecting pre-existing resources, such as primary care services, existing community resources, and volunteers, are promising configurations to achieve permanent interventions embedded in clinical practice.61 Recent calls amidst the COVID-19 pandemic sought to strengthen intersectoral collaborations between health and non-health sectors to address complex social problems and ensure health equity,89 90 which indicates a window of opportunity to foster these approaches by influencing health agendas globally. Future evaluations informed by realist epistemologies are required to understand the mechanisms enabling the sustainable implementation of loneliness and social isolation interventions in health and non-healthcare settings.91

We identified several facilitators influencing intervention outcomes and implementation. Well-defined referral pathways, collaborative approaches to design interventions, accessible and long-lasting interventions, and the involvement of professionals with strong interpersonal skills promoted successful intervention implementation. Studies have highlighted the positive effects of involving professionals with solid listening and communication skills to build trust relations with participants and help lessen fears when enrolling in new activities.88 92 In addition, we found that facilitating access to interventions in the form of transportation or affordability is a crucial component, as found by other reports.93 We also found that participants' and professionals' poor understanding of referral pathways, lack of fit between intervention components and participant interest, age-related limitations and the fear of joining new groups, were barriers that affected overall intervention uptake and acceptability. Interventions should be adapted to participants’ age-related physical and mental health conditions and social needs. Thus, adopting participatory or bottom-up approaches engaging the target population is paramount to design interventions tailored to the characteristics and needs of lonely and isolated older adults.94

Limitations

This scoping review provides a broad overview of an unexplored topic and opens new research opportunities on how to involve primary care to tackle social isolation and loneliness in older adults. However, the study had some limitations. First, it only includes peer-reviewed empirical studies in Spanish and English, and despite efforts to incorporate grey literature, we only identified one report which fulfilled the inclusion criteria, limiting the comprehensiveness of the review. Second, we conceptualised the search strategy using terms and synonyms of primary care. Thus, the review does not represent interventions conducted without primary care participation in other sectors such as research institutions, volunteering or NGOs. In addition, we did not capture healthcare sectors not labelled as primary care or their synonyms included in the search strategy, under-representing regions without primary care or with first-level care defined differently. We limited the review to primary care as we were interested in exploring the characteristics of interventions in this healthcare sector to answer the research questions. Finally, we encountered vague definitions relating to primary care, loneliness and social isolation in several articles, which posed a challenge during the eligibility phase of the review. We addressed this limitation by searching for widely used synonyms and excluding reports with a high degree of lack of clarity. A quality appraisal of the articles was not conducted as the scoping review aimed to map the existent literature instead of detecting the best available evidence to answer the proposed exploratory questions.45 46

Conclusion

Older adults are commonly enrolled in interventions to address loneliness and social isolation in primary care based on broad risk factors such as age or living arrangements without an assessment of these social problems. This might lead to undesired outcomes resulting from a lack of fit between older adults’ needs and the content of the intervention. There appears to be an increase in interventions consisting of intersectoral collaborations between primary care and non-healthcare sectors. Although this is a promising approach, widely supported by international organisations, improvement is required in reporting the theoretical underpinnings of the interventions. Long-lasting interventions are necessary to achieve meaningful social networks that can benefit lonely and socially isolated older adults. However, a significant number of interventions reported a duration of <6 months. Achieving sustainability should be a central outcome when designing and implementing loneliness and social isolation interventions in primary care.

bmjopen-2021-057729supp003.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Baumann for his valuable contribution as a second reviewer and Ketan Shankardass for his comments and suggestions on the first draft. We also acknowledge Mikaela Gray (librarian, University of Toronto) for her inputs when designing the search strategy and David Buss for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Twitter: @GalvezPabloH

Contributors: PG-H and CM conceptualised the study; PG-H wrote the study protocol, led the review and drafted the manuscript; LG-dP and CM provided expert input and conducted manuscript review and editing; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. PG-H is the overall guarantor of the study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Berg-Weger M, Morley JE. Editorial: loneliness and social isolation in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for Gerontological social work. J Nutr Health Aging 2020;24:456–8. 10.1007/s12603-020-1366-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perlman D, Peplau LA. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In: Duck SW, Gilmour R, eds. Personal relationships in disorder. London, UK: Academic Press, 1981: 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg T, Dykstra PA. Loneliness and social isolation. In: The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006: 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith KJ, Victor C. Typologies of loneliness, living alone and social isolation, and their associations with physical and mental health. Ageing Soc 2019;39:1709–30. 10.1017/S0144686X18000132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newall NEG, Menec VH. Loneliness and social isolation of older adults: why it is important to examine these social aspects together. J Soc Pers Relat 2019;36:925–39. 10.1177/0265407517749045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015;10:227–37. 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:218–27. 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christiansen J, Lund R, Qualter P, et al. Loneliness, social isolation, and chronic disease outcomes. Ann Behav Med 2021;55:203–15. 10.1093/abm/kaaa044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017;152:157–71. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.d’Hombres B, Schnepf S, Barjakova M. Loneliness – an unequally shared burden in Europe, 2018. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/default/files/fairness_pb2018_loneliness_jrc_i1.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep 2020].

- 11.Griffiths H. Social isolation and loneliness in the UK. With a focus on the use of technology to tacke these conditions, 2017. Available: https://iotuk.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Social-Isolation-and-Loneliness-Landscape-UK.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2020].

- 12.Menec VH, Newall NE, Mackenzie CS, et al. Examining social isolation and loneliness in combination in relation to social support and psychological distress using Canadian longitudinal study of aging (CLSA) data. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230673. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veazie S, Gilbert J, Winchell K. Addressing social isolation to improve the health of older adults: a rapid review, 2019. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537909/ [Accessed 19 Aug 2020]. [PubMed]

- 14.Perissinotto C, Holt-Lunstad J, Periyakoil VS, et al. A practical approach to assessing and mitigating loneliness and isolation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:657–62. 10.1111/jgs.15746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotterell N, Buffel T, Phillipson C. Preventing social isolation in older people. Maturitas 2018;113:80–4. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Age UK . All the lonely people: loneliness in later life, 2018. Available: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/loneliness/loneliness-report.pdf [Accessed 20 Jul 2020].

- 17.Dahlberg L, McKee KJ, Frank A, et al. A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging Ment Health 2021:1–25. 10.1080/13607863.2021.1876638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niedzwiedz CL, Richardson EA, Tunstall H, et al. The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: is social participation protective? Prev Med 2016;91:24–31. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hand C, Retrum J, Ware G, et al. Understanding social isolation among urban aging adults: informing Occupation-Based approaches. OTJR 2017;37:188–98. 10.1177/1539449217727119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu R, Leung G, Chan J, et al. Neighborhood social cohesion associates with loneliness differently among older people according to subjective social status. J Nutr Health Aging 2021;25:41–7. 10.1007/s12603-020-1496-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Rourke HM, Collins L, Sidani S. Interventions to address social connectedness and loneliness for older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 2018;18:214. 10.1186/s12877-018-0897-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freedman A, Nicolle J. Social isolation and loneliness: the new geriatric giants: approach for primary care. Can Fam Physician 2020;66:176–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Age UK Oxfordshire . Safeguarding the convoy. A call to action from the campaign to end loneliness, 2011. Available: https://linkinglives.uk/wp-content/uploads/formidable/6/safeguarding-the-convey_-_a-call-to-action-from-the-campaign-to-end-loneliness-1.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2020].

- 24.NHS . Primary care services, 2021. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/get-involved/get-involved/how/primarycare/ [Accessed 15 Mar 2021].

- 25.Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social . Cartera de servicios comunes de atención primaria, 2021. Available: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/prestacionesSanitarias/CarteraDeServicios/ContenidoCS/2AtencionPrimaria/home.htm [Accessed 9 Aug 2021].

- 26.Walters K, Kharicha K, Goodman C, et al. Promoting independence, health and well-being for older people: a feasibility study of computer-aided health and social risk appraisal system in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18:47. 10.1186/s12875-017-0620-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tung EL, De Marchis EH, Gottlieb LM, et al. Patient experiences with screening and assistance for social isolation in primary care settings. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36:1951–7. 10.1007/s11606-020-06484-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullen RA, Tong S, Sabo RT, et al. Loneliness in primary care patients: a prevalence study. Ann Fam Med 2019;17:108–15. 10.1370/afm.2358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jovicic A, McPherson S. To support and not to cure: general practitioner management of loneliness. Health Soc Care Community 2020;28:376–84. 10.1111/hsc.12869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: opportunities for the health care system. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mays AM, Kim S, Rosales K, et al. The leveraging exercise to age in place (LEAP) study: engaging older adults in community-based exercise classes to impact loneliness and social isolation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021;29:777–88. 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daban F, Garcia-Subirats I, Porthé V, et al. Improving mental health and wellbeing in elderly people isolated at home due to architectural barriers: a community health intervention. Aten Primaria 2021;53:102020. 10.1016/j.aprim.2021.102020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiskittle R, Tsang W, Schwabenbauer A, et al. Feasibility of a COVID-19 rapid response telehealth group addressing older adult worry and social isolation. Clin Gerontol 2021:1–15. 10.1080/07317115.2021.1906812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bleijenberg N, Ten Dam VH, Drubbel I, et al. Treatment fidelity of an evidence-based nurse-led intervention in a proactive primary care program for older people. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016;13:75–84. 10.1111/wvn.12151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wildman JM, Valtorta N, Moffatt S, et al. 'What works here doesn't work there': The significance of local context for a sustainable and replicable asset-based community intervention aimed at promoting social interaction in later life. Health Soc Care Community 2019;27:1102–10. 10.1111/hsc.12735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kellezi B, Wakefield JRH, Stevenson C, et al. The social cure of social prescribing: a mixed-methods study on the benefits of social connectedness on quality and effectiveness of care provision. BMJ Open 2019;9:e033137. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czaja SJ, Boot WR, Charness N, et al. Improving social support for older adults through technology: findings from the prism randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist 2018;58:467–77. 10.1093/geront/gnw249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mulligan K, Hsiung S, Bhatti S. Social prescribing in Ontario. Alliance for Healthier Communities 2020. https://cdn.ymaws.com/aohc.site-ym.com/resource/group/e0802d2e-298a-4d86-8af5-21156f9c057f/rxcommunity_final_report_mar.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sander R, Cattan M, White M. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Nurs Older People 2005;17:40–67. 10.7748/nop.17.1.40.s11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagan R, Manktelow R, Taylor BJ, et al. Reducing loneliness amongst older people: a systematic search and narrative review. Aging Ment Health 2014;18:683–93. 10.1080/13607863.2013.875122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masi CM, Chen H-Y, Hawkley LC, et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2011;15:219–66. 10.1177/1088868310377394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, et al. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011;11:647. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poscia A, Stojanovic J, La Milia DI, et al. Interventions targeting loneliness and social isolation among the older people: an update systematic review. Exp Gerontol 2018;102:133–44. 10.1016/j.exger.2017.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Community 2018;26:147–57. 10.1111/hsc.12367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.NHS . Primary care networks, 2021. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/primary-care-networks/ [Accessed 10 Aug 2021].

- 48.The Department of Health . National primary health care strategic framework. Commonwealth of Australia, 2013. Available: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/6084A04118674329CA257BF0001A349E/$File/NPHCframe.pdf[Accessed 18 Aug 2021].

- 49.Ministerio de Sanidad y Politica Social . Cartera de servicios comunes del Sistema Nacional de Salud Y procedimiento para SU actualización, 2009. Available: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/prestacionesSanitarias/publicaciones/docs/carteraServicios.pdf [Accessed 15 Aug 2021].

- 50.United Nations . World population ageing 2019. Department of Economic Affairs, 2019. Available: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf [Accessed 10 Sep 2021].

- 51.Yale University . Yale mesh analyzer. Cushing/Whitney medical library, 2015. Available: https://mesh.med.yale.edu/ [Accessed 2 Jun 2020].

- 52.Gerstein Science Information Centre . Advanced lit searching: a cheat sheet. In: Searching the literature: a guide to comprehensive searching in the health sciences. University of Toronto Libraries, 2021. https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/comprehensivesearching [Google Scholar]

- 53.Covidence systematic review software. Veritas health innovation Melbourne, Australia. Available: www.covidence.org [Accessed 20 Jun 2020].

- 54.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coll-Planas L, Del Valle Gómez G, Bonilla P, et al. Promoting social capital to alleviate loneliness and improve health among older people in Spain. Health Soc Care Community 2017;25:145–57. 10.1111/hsc.12284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conwell Y, Van Orden KA, Stone DM, et al. Peer companionship for mental health of older adults in primary care: a pragmatic, Nonblinded, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021;29:748–57. 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khan A, Bolina A. Can walking groups help with social isolation: a qualitative study. Educ Prim Care 2020;31:257–9. 10.1080/14739879.2020.1772120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Savikko N, Routasalo P, Tilvis R, et al. Psychosocial group rehabilitation for lonely older people: favourable processes and mediating factors of the intervention leading to alleviated loneliness. Int J Older People Nurs 2010;5:16–24. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2009.00191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Routasalo PE, Tilvis RS, Kautiainen H, et al. Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on social functioning, loneliness and well-being of lonely, older people: randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:297–305. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodríguez-Romero R, Herranz-Rodríguez C, Kostov B, et al. Intervention to reduce perceived loneliness in community-dwelling older people. Scand J Caring Sci 2021;35:366–74. 10.1111/scs.12852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lapena C, Continente X, Sánchez Mascuñano A, et al. Qualitative evaluation of a community-based intervention to reduce social isolation among older people in disadvantaged urban areas of Barcelona. Health Soc Care Community 2020;28:1488–503. 10.1111/hsc.12971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Honigh-de Vlaming R, Haveman-Nies A, Heinrich J, et al. Effect evaluation of a two-year complex intervention to reduce loneliness in non-institutionalised elderly Dutch people. BMC Public Health 2013;13:984. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taube E, Kristensson J, Midlöv P, et al. The use of case management for community-dwelling older people: the effects on loneliness, symptoms of depression and life satisfaction in a randomised controlled trial. Scand J Caring Sci 2018;32:889–901. 10.1111/scs.12520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moffatt S, Steer M, Lawson S, et al. Link worker social prescribing to improve health and well-being for people with long-term conditions: qualitative study of service user perceptions. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015203. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Franse CB, van Grieken A, Alhambra-Borrás T, et al. The effectiveness of a coordinated preventive care approach for healthy ageing (UHCE) among older persons in five European cities: a pre-post controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;88:153–62. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vogelpoel N, Jarrold K. Social prescription and the role of participatory arts programmes for older people with sensory impairments. J Integr Care 2014;22:39–50. 10.1108/JICA-01-2014-0002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borji M, Tarjoman A. Investigating the effect of religious intervention on mental vitality and sense of loneliness among the elderly referring to community healthcare centers. J Relig Health 2020;59:163–72. 10.1007/s10943-018-0708-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ožić S, Vasiljev V, Ivković V, et al. Interventions aimed at loneliness and fall prevention reduce frailty in elderly urban population. Medicine 2020;99:e19145. 10.1097/MD.0000000000019145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kruithof K, Suurmond J, Harting J. Eating together as a social network intervention for people with mild intellectual disabilities: a theory-based evaluation. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2018;13:1516089. 10.1080/17482631.2018.1516089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Díez E, Daban F, Pasarín M, et al. [Evaluation of a community program to reduce isolation in older people due to architectural barriers]. Gac Sanit 2014;28:386–8. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2014.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Howarth M, Griffiths A, da Silva A, et al. Social prescribing: a 'natural' community-based solution. Br J Community Nurs 2020;25:294–8. 10.12968/bjcn.2020.25.6.294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hernández-Ascanio J, Pérula-de Torres Luis Ángel, Roldán-Villalobos A, et al. Effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention to reduce social isolation and loneliness in community-dwelling elders: a randomized clinical trial. study protocol. J Adv Nurs 2020;76:337–46. 10.1111/jan.14230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carnes D, Sohanpal R, Frostick C, et al. The impact of a social prescribing service on patients in primary care: a mixed methods evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:835. 10.1186/s12913-017-2778-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Juang C, Huh JWT, Iyer S, et al. Feasibility, acceptance, and initial evaluation of a telephone-based program designed to increase socialization in older veterans. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2021;34:891988720944242. 10.1177/0891988720944242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomson LJ, Morse N, Elsden E, et al. Art, nature and mental health: assessing the biopsychosocial effects of a 'creative green prescription' museum programme involving horticulture, artmaking and collections. Perspect Public Health 2020;140:277–85. 10.1177/1757913920910443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sadarangani T, Missaelides L, Eilertsen E, et al. A mixed-methods evaluation of a nurse-led community-based health home for ethnically diverse older adults with multimorbidity in the adult day health setting. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 2019;20:131–44. 10.1177/1527154419864301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Der Heide LA, Willems CG, Spreeuwenberg MD. Implementation of CareTV in care for the elderly: the effects on feelings of loneliness and safety and future challenges. Technol Disabil 2012;24:283–91. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bolton E, Dacombe R. "Circles of support": social isolation, targeted assistance, and the value of "ageing in place" for older people. Qual Ageing 2020;21:67–7. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Theeke LA, Mallow JA, Barnes ER, et al. The feasibility and acceptability of listen for loneliness. Open J Nurs 2015;5:416–25. 10.4236/ojn.2015.55045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kharicha K, Iliffe S, Manthorpe J, et al. What do older people experiencing loneliness think about primary care or community based interventions to reduce loneliness? A qualitative study in England. Health Soc Care Community 2017;25:1733–42. 10.1111/hsc.12438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, et al. Loneliness, social isolation and social relationships: what are we measuring? a novel framework for classifying and comparing tools. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010799. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lim MH, Eres R, Vasan S. Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: an update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2020;55:793–810. 10.1007/s00127-020-01889-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu VJ, Lenert LA, Bunnell BE, et al. Automatically identifying social isolation from clinical narratives for patients with prostate cancer. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019;19:43. 10.1186/s12911-019-0795-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Age UK . Loneliness maps, 2011. Available: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/our-impact/policy-research/loneliness-research-and-resources/loneliness-maps/ [Accessed 8 Dec 2020].

- 85.World Health Organization . Primary health care, 2021. Available: https://wwwwhoint/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care [Accessed 24 Mar 2021].

- 86.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. Loneliness in the modern age: an evolutionary theory of loneliness (ETL). Adv Exp Soc Psychol 2018:127–97. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Holding E, Thompson J, Foster A, et al. Connecting communities: a qualitative investigation of the challenges in delivering a national social prescribing service to reduce loneliness. Health Soc Care Community 2020;28:1535–43. 10.1111/hsc.12976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu B. Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: a global challenge. Glob Health Res Policy 2020;5:27. 10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smith ML, Steinman LE, Casey EA. Combatting social isolation among older adults in a time of physical distancing: the COVID-19 social connectivity paradox. Front Public Health 2020;8:403. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shankardass K, Renahy E, Muntaner C, et al. Strengthening the implementation of health in all policies: a methodology for realist explanatory case studies. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:462–73. 10.1093/heapol/czu021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chan AW, Yu DS, Choi KC. Effects of tai chi qigong on psychosocial well-being among hidden elderly, using elderly neighborhood volunteer approach: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging 2017;12:85–96. 10.2147/CIA.S124604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sims-Gould J, Franke T, Lusina-Furst S, et al. Community health promotion programs for older adults: what helps and hinders implementation. Health Sci Rep 2020;3:e144. 10.1002/hsr2.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leask CF, Sandlund M, Skelton DA, et al. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Res Involv Engagem 2019;5:2. 10.1186/s40900-018-0136-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-057729supp001.pdf (61.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-057729supp002.pdf (97.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-057729supp003.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.