Abstract

Background

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ablation (EUS-A) therapy is a minimally invasive procedure for pancreatic-cystic tumors in patients with preoperative comorbidities or in patients who are not indicated for surgical resection. However, histopathologic characteristics of pancreatic cysts after ablation have not been well-elucidated.

Methods

Here, we analyzed pathological findings of 12 surgically resected pancreatic cysts after EUS-A with ethanol and/or paclitaxel injection.

Results

Mean patient age was 49.8 ± 13.6 years with a 0.3 male/female ratio. Clinical impression before EUS-A was predominantly mucinous cystic neoplasms. Mean cyst size before and after ablation therapy was similar (3.7 ± 1.0 cm vs. 3.4 ± 1.6 cm; p = 0.139). Median duration from EUS-A to surgical resection was 18 (range, 1–59) months. Mean percentage of the residual neoplastic lining epithelial cells were 23.1 ± 37.0%. Of the resected cysts, 8 cases (67%) showed no/minimal (<5%) residual lining epithelia, while the remaining 4 cases (33%) showed a wide range of residual mucinous epithelia (20–90%). Ovarian-type stroma was noted in 5 cases (42%). Other histologic features included histiocytic aggregation (67%), stromal hyalinization (67%), diffuse egg shell-like calcification along the cystic wall (58%), and fat necrosis (8%).

Conclusion

Above all, diffuse egg shell-like calcification along the pancreatic cystic walls with residual lining epithelia and/or ovarian-type stroma were characteristics of pancreatic cysts after EUS-A. Therefore, understanding these histologic features will be helpful for precise pathological diagnosis of pancreatic cystic tumor after EUS-A, even without knowing the patient's history of EUS-A.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasonography, Ablation, Pancreas, Mucinous cystic neoplasm, Pseudocyst

Introduction

Pancreatic cysts encompass a wide range of lesions, from nonneoplastic cysts to precursor lesions of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas [1]. Owing to recent technical advances in imaging modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the detection of pancreatic cysts is continuously increasing [2, 3, 4, 5]. Based on the results of a meta-analysis, which included 17 studies and 48,860 patients, the prevalence of incidentally detected pancreatic cysts is 8% [6]. Pancreatic cysts can be classified as nonneoplastic, benign (serous cystadenomas [SCAs]), cyst with malignant-potential, and cystic degeneration of malignant tumors (cystic degeneration of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors, pancreatoblastoma, acinar cell carcinomas, and solid pseudopapillary neoplasms [SPNs]) [6]. Nonneoplastic pancreatic cysts contain pseudocysts, ductal retention cysts, congenital cysts, and endometrioid cysts [6]. Serous cystic neoplasms (also known as SCAs) are benign neoplasms. Pancreatic cysts with malignant-potential can be further classified as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) [4, 7]. In addition, SPNs are, in general, malignant solid neoplasms in which degree of cystic degeneration increases with tumor size [8]. Because they have to balance their risk management of disease progression for cysts with malignant potential and avoid overtreatment for nonneoplastic or benign neoplastic cysts, management of pancreas cysts is complicated for clinicians.

Surgical resection of pancreatic cystic neoplasms is associated with substantially increased morbidity rates of 20–40% and mortality rates up to 2% [9, 10, 11]. In addition, preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic cysts by CT scan may not be correct, since only one-quarter of the surgically resected serous cystic neoplasms s were correctly diagnosed by preoperative CT scan in a large-scale study [12, 13]. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided ablation (EUS-A) therapy was introduced as a promising treatment option for patients with pancreatic cysts using minimally invasive approaches [7, 13, 14, 15]. Ethanol was the most commonly used ablative agent [16]. In addition, booster injections of chemotherapeutic agents improved the ablative effects of ethanol owing to a synergistic effect of lysis of cystic lining epithelial cells by a combination of ethanol lavage and secondary paclitaxel injection [14, 15]. The complete resolution rates after EUS-A therapy ranged from 9% to 85% across several studies [13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. In the literature, a few histologic features of EUS-A therapy were reported after surgical resection [13, 14, 20, 24, 25, 26], including denudation of the epithelial cells, atrophy, and fibrosis [14, 20, 24]. However, histopathologic characteristics of pancreatic cysts after ablation have not been comprehensively evaluated. In this study, we systemically analyzed the histopathologic characteristics of surgically resected pancreatic cysts after EUS-guided ethanol and/or paclitaxel ablation therapy.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved from the Institutional Review Board (approval number, 2013-0618) with waiver of patient's consents. Twelve cases of surgically resected pancreatic cysts after EUS-A with ethanol and/or paclitaxel injection, from 2006 to 2015, were selected from the pathology database. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for EUS-A therapy were the same, as previously reported [14]. In brief, the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) unilocular or oligolocular pancreatic cysts; (2) indeterminate pancreatic cysts for which EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration was indicated to obtain additional information; and/or (3) pancreatic cysts with increased cyst size during the follow-up period. The exclusion criteria for EUS-A therapy were as follows: (1) pancreatic cysts that had typical SCA morphology (honeycomb appearance); (2) a recently identified episode of pancreatitis and parenchymal changes on imaging which suggested a pseudocyst; (3) the presence of communication between the cystic lesion and the main pancreatic duct on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; (4) overt carcinomas with peripancreatic invasion by radiologic imaging; and/or (5) patients with a bleeding tendency (prothrombin time >1.5 times the international normalized ratio or a platelet count <50,000/μL). Clinical characteristics were obtained from the electronic medical records, which included age, sex, imaging findings, CEA levels of serum and cystic fluid, and outcomes after the ablation therapy.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides from pancreatic cysts (mean, 7.3 ± 4.2 slides) were selected and reviewed by 2 pathologists (S.A. and S.-M.H.). Evaluated histopathologic features included the presence of residual lining epithelia of the entire pancreatic cysts, presence of residual ovarian-type stroma, inflammatory cell infiltrations, hyalinization, calcification, hemorrhage, pigmentation, cholesterol cleft, and fat necrosis.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the size of pancreatic cysts on initial and follow-up CT scan images. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the Cases

Patient's clinicopathologic features are summarized in Table 1. Mean patient age was 49.8 ± 13.6 years with a 0.3 male/female ratio. Pretreatment imaging diagnoses before EUS-A included the following: 10 MCNs (84%), one SCA (8%), and one epidermoid cyst (8%). Mean cystic fluid CEA and amylase levels were 1563.8 ± 2682.3 ng/mL (range, 1.4–8,190 ng/mL) and 1186.6 (range, 11–6,005) U/L, respectively. The mean size of pancreatic cysts before ablation therapy was 3.7 ± 1.0 cm. On the first follow-up CT scan imaging after ablation therapy, the mean size of pancreatic cysts was 3.4 ± 1.6 cm. Compared to the mean size before ablation therapy, mean size after ablation was not different (p = 0.139). Median second follow-up time after ablation was 18 (range, 1–59) months. The mean size of pancreatic cysts after ablation therapy at the second follow-up was 3.6 ± 1.7 cm. On the second follow-up CT scan imaging, compared to the size before ablation therapy, partial resolution (at least a 30% decrease in the longest diameter) was observed in 4 cases. Meanwhile, the remaining 8 cases (67%) had persistent cysts. Among those persistent cysts, 2 cases (2/8, 25%) were progressive with at least a 20% increase in the longest diameter of the cyst size. In addition, leakage of cystic fluid was observed in 2 cases (17%). Finally, all 12 patients underwent surgical resection: 9 underwent distal pancreatectomy (75%); 2 (17%) underwent pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy; and 1 (8%) underwent central pancreatectomy.

Table 1.

Summary of clinicopathologic characteristics of 12 cases of pancreatic cysts after EUS-A therapy

| Case No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 26 | 44 | 46 | 70 | 62 | 29 | 48 | 43 | 48 | 60 | 64 | 58 |

| Sex | F | F | F | F | M | M | F | F | F | F | M | F |

| Duration to operation, months | 18 | 14 | 30 | 31 | 15 | 59 | 18 | 33 | 11 | 1 | 26 | 3 |

| Clinical impression | MCN | MCN | MCN | MCN | MCN | Epidermoid cyst | MCN | SCA | MCN | MCN | MCN | MCN |

| Original pathological diagnosis | MCN | MCN | MCN | Pseudocyst | Pseudocyst | Pseudocyst | Pseudocyst | Degenerated cyst | MCN | MCN | Hemorrhagic cyst | Pseudocyst |

| Pre-procedure size,* cm | 2.6 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 5 | 3 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| Post-procedure size,* cm | 2.8 | 3.6 | 2.2 | 3 | 4.6 | 6.6 | 3 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 6.8 |

| Amount of reagent, mL | E (4) + P (2) | E (20) + P (3) | E (14) + P (4) | E (28) + P (5) | E (25) + P (5) | E (28) + P (5) | E (15) + P (5) | E (18) + P (5) | E (25) + P (4) | E (4) | E (4) + P (1) | E (18) + P (1) |

| Lining epithelia, % | MUC (90) | MUC (90) | MUC (70) | No | No | No | No | No | MUC (5) | MUC (20) | Cuboidal (5) | No |

| Ovarian stroma | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| Hyalinization | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Calcification | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Chronic inflammation† | − | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Histiocytic aggregation | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Hemorrhage | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| Pigmentation | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Cholesterol cleft | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Fat necrosis | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

E, ethanol; P, paclitaxel; MUC, mucinous; MCN, mucinous cystic neoplasm; SCA, serous cystadenoma; EUS-A, endoscopic ultrasound-guided ablation.

Pre- and post-procedure sizes were measured on CT or EUS.

Severity of chronic inflammation was evaluated (+, mild; ++, moderate to severe).

Histopathologic Findings

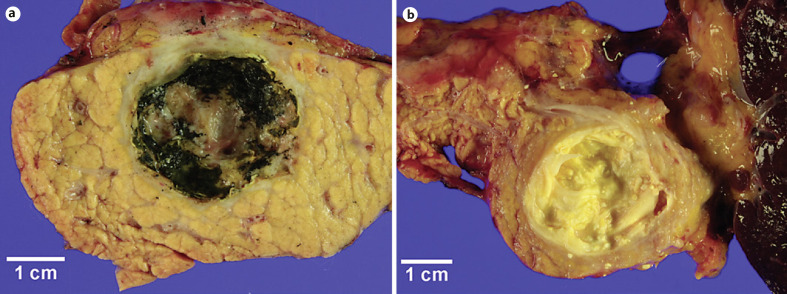

Representative images of surgically resected pancreatic cysts after ablation therapy during gross examination are shown in Figure 1. Median time between ablation therapy and surgical resection of pancreatic cysts was 18 (range, 1–59) months.

Fig. 1.

a, b Representative gross images of pancreatic cysts after endoscopic ultrasound-guided ablation therapy. Yellow diffuse egg shell-like calcifications are along the pancreatic cystic walls.

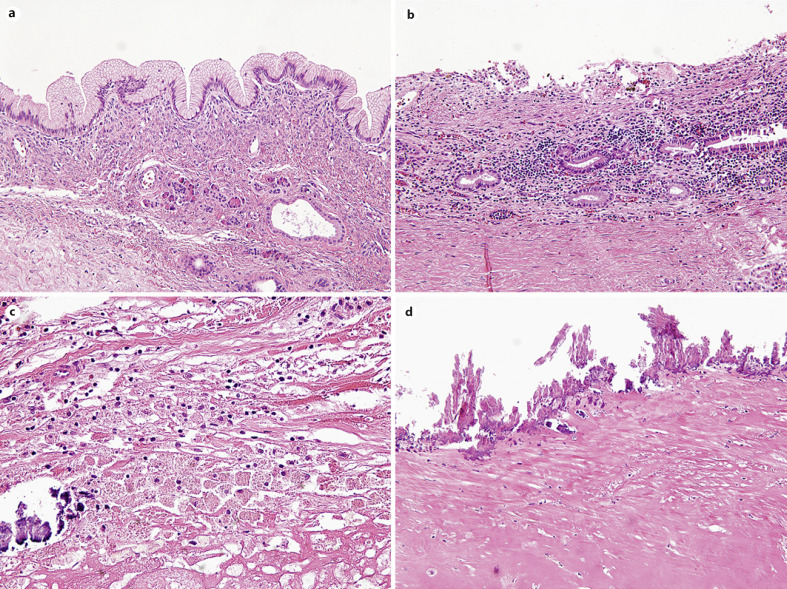

Mean percentage of residual lining epithelial cells of the pancreatic cysts after surgical resection were 23 ± 37% (Fig. 2a). Eight cases (67%) showed either no (n = 6) or <5% (n = 2) residual lining epithelia. In contrast, 4 cases (33%) showed various degrees of residual mucinous epithelium (mean, 67.5 ± 33.0; range, 20–90%). In addition, ovarian-type stroma was observed in 5 cases (42%, Fig. 2a). Five cases had both residual lining mucinous epithelia and ovarian-type stroma, which therefore could be diagnosed as MCNs.

Fig. 2.

Representative microscopic images of commonly observed histologic features of pancreatic cyst after ablation therapy. a Residual mucinous lining epithelium with ovarian-type stroma (×200). b Moderate stromal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration (×200). c Foamy histiocytic aggregation with calcification (×400). d Diffuse calcification and stromal hyalinization along the cystic wall (×200).

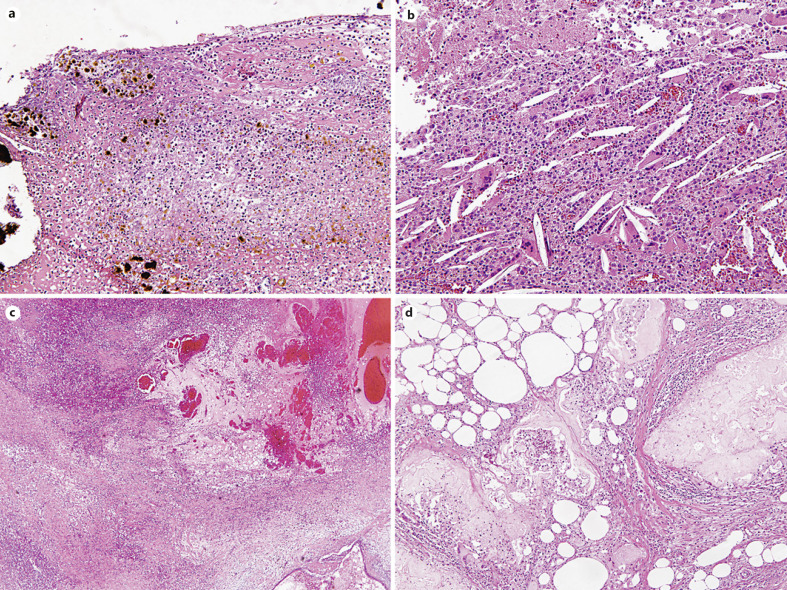

The remaining 7 cases which had no or minimal residual lining epithelia had been diagnosed as a pseudocyst (5/12, 42%), a degenerated cyst (1/12, 8%) or a hemorrhagic cyst (1/12, 8%) in the original pathology reports without providing information about preoperative ablation treatment at the time of pathology diagnoses. Frequently observed histologic features include moderate chronic active stromal inflammation (9/12, 75%, Fig. 2b), aggregation of foamy histiocytes (8/12, 67%, Fig. 2c), marked stromal hyalinization (8/12, 67%), stromal fibrosis (5/12, 42%), and diffuse calcification along the cystic wall (7/12, 58%, Fig. 2d). Less frequently, necrotic tissue with brown pigments and numerous neutrophilic infiltration (3/12, 25%, Fig. 3a), cholesterol clefts (3/12, 25%, Fig. 3b), granulation tissue (2/12, 8%), hemorrhage (2/12, 8%, Fig. 3c), and fat necrosis (2/12, 8%, Fig. 3d) were observed.

Fig. 3.

Representative microscopic images of less commonly observed histologic features pancreatic cyst after ablation therapy. a Necrotic tissue with brown pigments with numerous neutrophils (×200). b Cholesterol left (×200). c Hemorrhage (×40). d Fat necrosis in peripancreatic soft tissue (×200).

Discussion

EUS-A therapy has been developed as a minimally invasive approach, and ethanol injection was the most commonly used ablative agent, which lead to cell death by lysis of cytoplasmic membrane, protein denaturation, and vascular occlusion [16]. In addition, paclitaxel improved the ablative effects of the therapy by inhibiting microtubule function during cell division [27], and increasing the synergistic effect after ethanol injection [14, 15]. The hydrophobic nature of paclitaxel increases its period of action within the pancreatic cysts [15]. Several previous studies have focused on the efficacy and safety of EUS-A therapy of pancreatic cysts using ethanol and/or paclitaxel [13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. In this study, we focused on histopathologic aspects of this ablation therapy.

We quantitatively evaluated residual neoplastic lining epithelial cells and found that about two-thirds (8/12, 67%) had no or minimal residual lining epithelial cells in surgically resected pancreatic cysts after ablation. Similar to our results, Oh and colleagues [14] reported that 75% (3/4) of the cases showed marked epithelial ablation (range, 25–100%) in resected pancreatic cysts after ablation. In contrast, in nontreated MCN cases before surgical resection, approximately half of the neoplastic epithelial lining was eroded [28]. Therefore, pancreatic cysts treated with EUS-guided ablation therapy may have a wider area of the cystic wall without covering lining epithelial cells after ablation.

In present study, 84% (10/12) of cases had a clinical impression of pancreatic cysts, mainly MCNs based on pretreatment imaging studies. As is well-known, ovarian-type stroma is a distinct histologic features of MCNs [28]. As expected, we found ovarian-type stroma in about half (5/12, 42%) of the cases, and all 5 cases with ovarian-type stroma had residual lining mucinous epithelia. On the other hand, among the remaining 7 cases without ovarian-type stroma, 6 cases (6/7, 86%) showed complete epithelial ablation. However, in a study by Gan and colleagues [20], ovarian-type stroma was found in all resected pancreatic cysts after EUS-guided ethanol lavage (n = 5). Moreover, they found ovarian-type stroma even in a totally denuded pancreatic cyst [20]. The discrepancy in these results regarding residual ovarian-type stroma and residual lining epithelia might be caused by different types or injected amounts of ablative agents. Although pre-ablation treatment radiologic imaging diagnoses of the cystic lesions included SCA and epidermoid cyst, we could not find definite histologic evidence of some of the cysts due to lack of lining epithelial cells.

As mentioned earlier, a few histologic features have been identified in resected pancreatic cysts after ablation [13, 14, 20, 24, 25, 26]. Although epithelial denudation, atrophy, and fibrosis have been described in previous studies [14, 20, 24], other features such as histiocytic aggregation, marked stromal hyalinization, and diffuse egg shell-like calcification along the cystic wall have not. Interestingly, except for diffuse egg shell-like calcification along the cystic wall, many histologic findings overlapped with those of pancreatic pseudocysts, including moderate chronic active inflammation, histiocytic aggregation, marked stromal hyalinization, granulation tissue formation, hemorrhage, necrotic tissue with brown pigmentation, cholesterol cleft, and fat necrosis. Therefore, residual lining epithelia, ovarian-type stroma, and diffuse egg shell-like calcification along the cystic wall are the only features that can differentiate pancreatic cysts after EUS-guided ablation therapy from pseudocysts. Indeed, in some cases, the patients' history of ablation therapy was not provided at the time of pathology diagnosis. Therefore, the original pathological diagnosis of those cases was a pancreatic pseudocyst.

In conclusion, diffuse egg shell-like calcification along the pancreatic cystic walls with focal residual lining epithelia and/or ovarian-type stroma were characteristics of pancreatic cysts after ablation therapies with ethanol and/or paclitaxel injection which differentiate them from pseudocysts. Understanding these histologic features will be helpful for a precise pathological diagnosis of pancreatic cystic tumor after ablation therapies, even without knowing the patient's history of cystic ablation therapy.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved from the Institutional Review Board (approval number, 2013-0618) with waiver of patient consents.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (NRF-2012R1A1A2003360).

Author Contributions

Concepts and design: S.-M.H.; definition of intellectual contents: S.-Y.J. and S.-M.H.; literature search and data acquisition: S.A., Y.-N.S., and S.J.K.; clinical studies: D.-W.S.; data analysis: S.A. and S.-Y.J.; statistical analysis: S.A.; manuscript preparation: S.A.; manuscript editing and review: S.-Y.J. and S.-M.H. All authors critically read and approved the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This work was presented in part at the 108th Annual Meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, March 16–21, 2019 in National Harbor, MD, USA.

Sun-Young Jun and Seung-Mo Hong are co-corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Law JK, Hruban RH, Lennon AM. Management of pancreatic cysts: a multidisciplinary approach. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29((5)):509–16. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328363e3b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, Berlanstein B, Siegelman SS, Kawamoto S, et al. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191((3)):802–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jong K, Nio CY, Hermans JJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Gouma DJ, van Eijck CH, et al. High prevalence of pancreatic cysts detected by screening magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8((9)):806–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang YR, Park JK, Jang JY, Kwon W, Yoon JH, Kim SW. Incidental pancreatic cystic neoplasms in an asymptomatic healthy population of 21,745 individuals: large-scale, single-center cohort study. Medicine. 2016;95((51)):e5535. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spinelli KS, Fromwiller TE, Daniel RA, Kiely JM, Nakeeb A, Komorowski RA, et al. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann Surg. 2004;239((5)):651–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124299.57430.ce. discussion 7–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zerboni G, Signoretti M, Crippa S, Falconi M, Arcidiacono PG, Capurso G. Systematic review and meta-analysis: prevalence of incidentally detected pancreatic cystic lesions in asymptomatic individuals. Pancreatology. 2019;19((1)):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attila T, Adsay V, Faigel DO. The efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided ablation of pancreatic cysts with alcohol and paclitaxel: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31((1)):1–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jun SY, Hong SM. Nonductal pancreatic cancers. Surg Pathol Clin. 2016;9((4)):581–93. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goh BK, Tan YM, Cheow PC, Chung YF, Chow PK, Wong WK, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: an appraisal of an aggressive resectional policy adopted at a single institution during 15 years. Am J Surg. 2006;192((2)):148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen PJ, D'Angelica M, Gonen M, Jaques DP, Coit DG, Jarnagin WR, et al. A selective approach to the resection of cystic lesions of the pancreas: results from 539 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244((4)):572–82. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237652.84466.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horvath KD, Chabot JA. An aggressive resectional approach to cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg. 1999;178((4)):269–74. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khashab MA, Shin EJ, Amateau S, Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, et al. Tumor size and location correlate with behavior of pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106((8)):1521–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JK, Song BJ, Ryu JK, Paik WH, Park JM, Kim J, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided pancreatic cyst ablation. Pancreas. 2016;45((6)):889–94. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh HC, Seo DW, Song TJ, Moon SH, Park DH, Soo Lee S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided ethanol lavage with paclitaxel injection treats patients with pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2011;140((1)):172–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh HC, Seo DW, Lee TY, Kim JY, Lee SS, Lee SK, et al. New treatment for cystic tumors of the pancreas: EUS-guided ethanol lavage with paclitaxel injection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67((4)):636–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelczer RK, Charboneau JW, Hussain S, Brown DL. Complications of percutaneous ethanol ablation. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17((8)):531–3. doi: 10.7863/jum.1998.17.8.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caillol F, Poincloux L, Bories E, Cruzille E, Pesenti C, Darcha C, et al. Ethanol lavage of 14 mucinous cysts of the pancreas: a retrospective study in two tertiary centers. Endosc Ultrasound. 2012;1((1)):48–52. doi: 10.7178/eus.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeWitt J, McGreevy K, Schmidt CM, Brugge WR. EUS-guided ethanol versus saline solution lavage for pancreatic cysts: a randomized, double-blind study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70((4)):710–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiMaio CJ, DeWitt JM, Brugge WR. Ablation of pancreatic cystic lesions: the use of multiple endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol lavage sessions. Pancreas. 2011;40((5)):664–8. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182128d06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gan SI, Thompson CC, Lauwers GY, Bounds BC, Brugge WR. Ethanol lavage of pancreatic cystic lesions: initial pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61((6)):746–52. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeWitt JM, Al-Haddad M, Sherman S, LeBlanc J, Schmidt CM, Sandrasegaran K, et al. Alterations in cyst fluid genetics following endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreatic cyst ablation with ethanol and paclitaxel. Endoscopy. 2014;46((6)):457–64. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moyer MT, Dye CE, Sharzehi S, Ancrile B, Mathew A, McGarrity TJ, et al. Is alcohol required for effective pancreatic cyst ablation? The prospective randomized CHARM trial pilot study. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4((5)):E603–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyer MT, Sharzehi S, Mathew A, Levenick JM, Headlee BD, Blandford JT, et al. The safety and efficacy of an alcohol-free pancreatic cyst ablation protocol. Gastroenterology. 2017;153((5)):1295–303. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh HC, Seo DW, Kim SC, Yu E, Kim K, Moon SH, et al. Septated cystic tumors of the pancreas: is it possible to treat them by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided intervention? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44((2)):242–7. doi: 10.1080/00365520802495537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi JH, Seo DW, Song TJ, Park DH, Lee SS, Lee SK, et al. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic ultrasound-guided ablation of pancreatic cysts. Endoscopy. 2017;49((9)):866–73. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-110030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim KH, McGreevy K, La Fortune K, Cramer H, DeWitt J. Sonographic and cyst fluid cytologic changes after EUS-guided pancreatic cyst ablation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85((6)):1233–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowinsky EK, Donehower RC. Paclitaxel (taxol) N Engl J Med. 1995;332((15)):1004–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504133321507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.An S, Kim MJ, Kim SJ, Sung YN, Kim YW, Song KB, et al. Multiple KRAS mutations in the non-mucinous epithelial lining in the majority of mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Histopathology. 2019;75((4)):559–67. doi: 10.1111/his.13897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors.