Abstract

Background

Metastatic cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) has poor prognosis and is recalcitrant to the current treatment strategies, which warrants the necessity to identify novel prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Given that CSCC is a virus-induced malignancy, we hypothesized that the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) involved in the innate immune response likely play a critical role in tumor development.

Methods

A bioinformatics analysis, qPCR, IHC, immunofluorescence, and WB were performed to determine the expression of NOD1/NOD2. The biological characteristics of overexpression NOD1 or NOD2 CSCC cells were compared to parental cells: proliferation, migration/invasion and cytokines secretion were examined in vitro through CCK8/colony formation/cell cycle profiling/cell counting, wound healing/transwell, and ELISA assays, respectively. The proliferative and metastatic capacity of overexpression NOD1 or NOD2 CSCC cells were also evaluated in vivo. FCM, mRNA and protein arrays, ELISA, and WB were used to identify the mechanisms involved, while novel pharmacological treatment were evaluated in vitro and in vivo. Quantitative variables between two groups were compared by Student’s t test (normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal distribution), and one-way or two-way ANOVA was used for comparing multiple groups. Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare qualitative variables. Survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

NOD1 was highly expressed in CSCC with lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI, P < 0.01) and lymph node metastasis (LM, P < 0.01) and related to worse overall survival (OS, P = 0.016). In vitro and in vivo functional assays revealed that the upregulation of NOD1 or NOD2 in CSCC cells promoted proliferation, invasion, and migration. Mechanistically, NOD1 and NOD2 exerted their oncogenic effects by activating NF-κb and ERK signaling pathways and enhancing IL-8 secretion. Inhibition of the IL-8 receptor partially abrogated the effects of NOD1/2 on CSCC cells.

Conclusions

NOD1/2-NF-κb/ERK and IL-8 axis may be involved in the progression of CSCC; the NOD1 significantly enhanced the progression of proliferation and metastasis, which leads to a poor prognosis. Anti-IL-8 was identified as a potential therapeutic target for patients with NOD1high tumor.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-022-02248-w.

Keywords: Cervical squamous cell carcinoma, NOD1/2, Tumorigenicity, Metastasis, IL-8

Background

Cervix carcinoma is the most common malignancy of the reproductive tract in females [1, 2], and developing countries account for 85–90% of the newly diagnosed cases and deaths every year [1, 3]. The WHO Cervical Cancer Elimination Modelling Consortium (CCEMC) has been established to eliminate cervical cancer in the low-income and lower middle-income countries through regular screening and human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination [4–6]. The burden of cervical cancer is especially high in China, and over 106,000 new cases and 48,000 deaths have been reported in 2018 [2, 7, 8]. HPV infection-induced cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) is the predominant pathological subtype of cervical cancer [3, 9]. Since vaccination is estimated to achieve only a 0.1–0.5% reduction in mortality rates until 2030 [5, 10], there is an urgent need for novel treatment strategies. Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in the progression of CSCC in order to identify potential therapeutic targets. Given the vital role of HPV in cervical carcinogenesis, the correlation between immunological factors and cancer progression needs to be investigated.

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are host sensors that detect pathogen-specific molecules and act as the first line of defense against infections. The toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain receptors (NODs) are the two major PRRs expressed on/in the cells that recognize invading pathogens and mediate the inflammatory response [11–13]. NOD1 and NOD2 recognize pathogens that express meso-diaminopimelic acid (meso-DAP) and muramyl dipeptide (MDP) respectively [11, 14, 15]. Recent studies have implicated PRRs in the carcinogenesis of multiple tissues. TLR4 and TLR2 enhance metastasis of colon cancers [16–18], whereas NOD1 promotes several gastrointestinal malignancies [19] such as colon cancer [20], as well as head and neck and oral squamous cell carcinoma [21, 22]. In addition, higher baseline levels of TLR2 and TLR7 are associated with prior clearance of HPV in women with cervical intra-epithelial (CIN) 2 lesions [23]. TLR5 is overexpressed in high-grade cervical dysplasia and invasive cancers but is commonly absent in the normal cervix [24]. TLR2 and TLR9 show significant variation in their expression levels in CSCC [25]. Furthermore, the TLR9 agonist CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG ODN) can effectively treat solid tumors in combination with rlipo-E7m [26]. In contrast, the role of NODs in cervical cancer progression is unclear. A recent study showed that downregulation of NOD1 promoted CIN progression to cervical cancer [27]. In this study, we examined the expression of the NOD family of proteins in CSCC tissues and cell lines to gain further insights into their role in advanced cervical malignancies.

Results

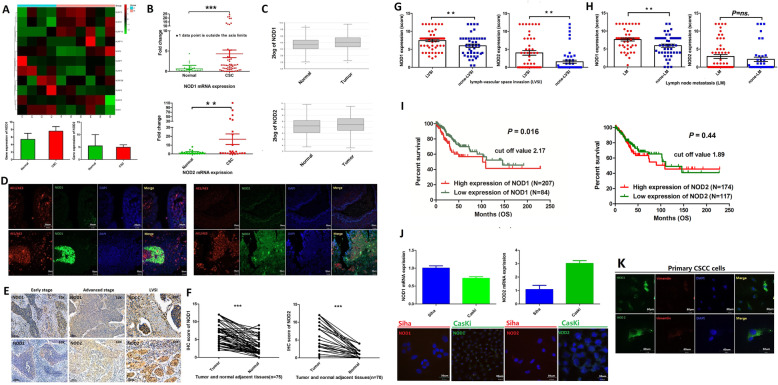

NOD1 is overexpressed in CSCC tissues and associated with poor prognosis

The CSCC tissues were confirmed by histopathological examination and immunostaining for specific markers (Additional file 1: Fig.S1A). Bioinformatics analysis identified 5140 upregulated genes in the CSCC samples, including NOD1 and NOD2 (Additional file 1: Fig.S1B). Preliminary RNA-Seq analysis confirmed that NOD1 and NOD2 were upregulated in the CSCC relative to normal cervix tissues (Fig. 1A), which was further confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1B) and analysis of TCGA data (Fig. 1C). Consistent with this, the NOD1 and NOD2 protein levels were significantly higher in the CSCC tissues compared to the paired adjacent normal cervix tissues (Fig. 1D–F). Furthermore, both NOD1 and NOD2 were overexpressed in embolic tumor cells resulting from lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI) compared to the primary tumors without LVSI (P < 0.05, Fig. 1G), whereas significantly higher expression of NOD1 was detected in the CSCC tissues of patients with lymph node metastasis (LM) relative to the non-LM samples (P < 0.05, Fig. 1H). Although the tumor stage was not associated with NOD1/NOD2 expression, both were overexpressed in tumors with poorer differentiation (Additional file 1: Fig.S1C and S1D). In clinic practice, LVSI and LM were risk factors for un-promising survival trend. In agreement with the above findings, TCGA data showed that overexpression of NOD1 predicted a worse prognosis in CSCC patients (Fig. 1I, left panel), whereas NOD2 expression level did not show significantly correlation with the overall survival (Fig. 1I, right panel). Interestingly, while the NOD1 and NOD2 mRNA levels showed a positive correlation (Additional file 1: Fig.S1E); the TCGA data showed that both overexpression of NOD1 and NOD2 predicted a worse prognosis trend in CSCC patients but not reached significance. These results maybe according to the small cohort group (Additional file 1: Fig.S1F). Consistent with the patient samples, NOD1/NOD2 mRNA and protein levels were intrinsically expressed in the CSCC cell lines (Fig. 1J) and primary CSCC cells (Fig. 1K). In conclusion, NOD1 may play an important role in the progression of CSCC patients.

Fig. 1.

NOD1 and NOD2 are upregulated in human CSCC tissues and associated with poor survival. A Partial heat map showing differentially expressed NLR genes including NOD1 and NOD2 in the CSCC (n = 4) and normal cervix (n = 6) tissues. B NOD1 and NOD2 mRNA copy numbers in unpaired CSCC tissues (NOD1, n = 59; NOD2, n = 24) and normal cervix (NOD1, n = 33; NOD2, n = 31). C NOD1 and NOD2 mRNA expression in the CSCC (NOD1, n = 75; NOD2 n = 75) and normal cervix samples (non-tumoral adjacent tissue, NOD1, n = 188; NOD2 n = 188) extracted from TCGA database. D Representative immunofluorescence images showing co-staining of AE1/AE3 and NOD1/NOD2 in paired CSCC tumors and normal cervix tissues (data were from two independent experiments with eight samples). E Representative IHC images showing in situ expression of NOD1and NOD2 in paired human CSCC tissues of different pathological stages (early and late stages and LVSI) and adjacent non-tumor tissues (scale bar = 100 μm and magnification—× 10 or × 20). F–H IHC scores of NOD1 and NOD2 in F paired tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues (NOD1, n = 75; NOD2, n = 70), G tumors with and without LVSI (NOD1: LVSI = 58, non-LVSI = 45; NOD2: LVSI = 48, non-LVSI = 49), and H tumors with and without LM (NOD1: LM = 48, non-LM = 48; NOD2: LM = 55, non-LM = 39). I Kaplan-Meier curves showing overall survival of CSCC patients demarcated on the basis of in situ NOD1 expression (http://www.proteinatlas.org). J NOD1 and NOD2 mRNA levels and representative immunofluorescence images showing respective protein levels in Siha and CasKi cell lines. K Immunofluorescence images showing respective NOD1 and NOD2 protein levels in primary CSC cells. For cell lines, the experiments were performed in two wells with three replicates; for primary cells, the experiments were performed by two independent experiments with four samples; the picture is a representative one. *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

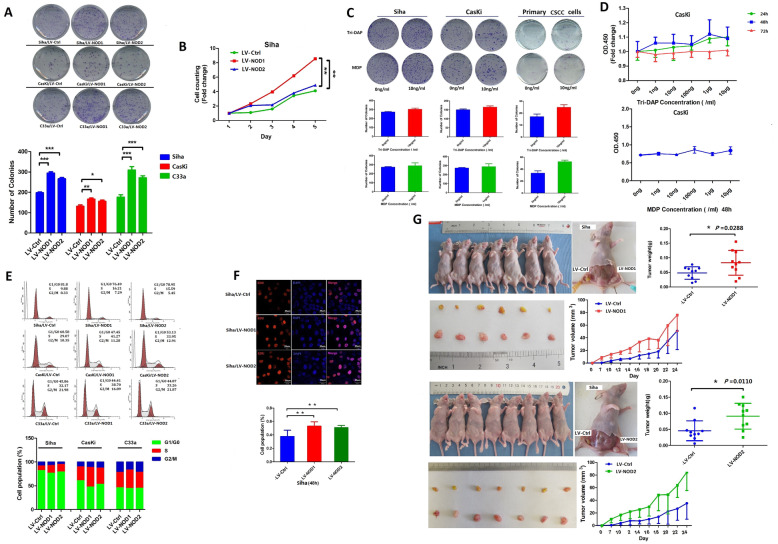

NOD1 and NOD2 promoted CSCC cell proliferation and enhanced metastatic potential

The primary cells were purified and identified as previously described (Additional file 2: Fig.S2A). NOD1 and NOD2 were stably upregulated in the primary cells and cell lines with Tri-DAP and MDP stimulation, respectively (Additional file 2: Fig.S2B). In addition, the cell lines were transduced with NOD1/2-overexpressing lentiviruses (Additional file 2: Fig.S2C). Ectopic expression of NOD1 or NOD2 significantly enhanced the colony-forming potential of the CSCC cell lines (Fig. 2A, P < 0.05), which was consistent with their increased viability and proliferation rates in Siha cells (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, the NOD1 and NOD2 ligands only slightly enhanced the proliferative capacity of the CSCC cells (Fig. 2C, D). Consistent with the above, a significantly higher proportion of Siha/LV-NOD1/NOD2 cells were observed in the S phase compared to the Siha/LV-ctrl cells (Fig. 2E, F; P < 0.01). Likewise, the Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells resulted in significantly larger tumors in vivo compared to the control cells (Fig. 2G).

Fig. 2.

NOD1 and NOD2 enhanced the proliferation of CSCC cells. A Number of colonies formed by Siha, CasKi, and C33a cells overexpressing NOD1 or NOD2 (each group was performed triplicate wells, reproducible in three independent experiments). B Time-dependent increase in the number of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells (results were highly reproducible triplicate: representative data of triplicate). C Number of colonies formed by cell lines and primary CSCC cells treated with Trip-DAP or MDP (10 ng/mL). D Proliferation of cell lines treated with various concentrations of NOD1 or NOD2 ligands. The assay of C and D was repeated thrice for the cell lines and twice for the primary cells using three independent samples. E Cell cycle distribution of control and NOD1/NOD2 overexpressing Siha, CasKi, and C33a cells. The percentage of cells in each phase is shown on the right. F Representative images of EDU-stained Siha/LV-NOD1, Siha/LV-NOD2, and Siha/LV-Ctrl cells (scale bar—30 μm, triplicate independent experiments). G Representative images of tumors in BALB/C nude mice subcutaneously injected with Siha/LV-NOD1, Siha/LV-NOD2 (right), and respective control cells (left). The tumor volume and weight of the indicated groups are shown on the right. All data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 10 for each group). *** P < 0.001; ** P < 0.01; * P < 0.05

The impact of NOD1 and NOD2 expression on the metastatic potential of CSCC cells was analyzed by in vitro and in vivo assays [28]. NOD1 and NOD2 overexpression significantly increased the extent of wound closure, as well the number of cells that migrated or invaded into the bottom surface of the transwell insert membranes (Fig. 3A–C, Additional file 3: Fig.S3A). The metastatic effect of NOD1/2 was also verified on the primary CSCC cells (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the number of pulmonary metastatic nodules was markedly higher in the mice injected intravenously with Siha/LV-NOD1/NOD2 cells as opposed to the control Siha cells (Fig. 3E). Although the weight of the tumor-bearing mice was similar across the three groups (Additional file 3: Fig.S3B), the animals harboring Siha/LV-NOD1 or Siha/LV-NOD2 tumors had worse survival rates (Fig. 3F). Taken together, NOD1 and NOD2 significantly promoted CSCC proliferation by accelerating transition into the S phase of the cell cycle, and increased their metastatic potential.

Fig. 3.

NOD1 and NOD2 promoted migration and invasion of CSCC cells. A Representative images showing wound closure of control and NOD1/2-overexpressing Siha and CasKi cells at 24 h after scratching. The percentage of wound healing is shown on the right. Data represent triplicates of one representative experiment. B, C The representative images indicating migration (panel B) (Siha, CasKi and C33a) and invasion (panel C) (Siha and CasKi) ability of NOD1/NOD2-overexpressing cell lines by transwell assay (reproducible in three independent experiments in triplicate wells). D Representative migration and invasion images of the primary CSCC cells by transwell members (The cells were pretreated with 10 ng/mL Tri-DAP or MDP at 24 h) (three independent experiments with three primary CSCC cells, triplicate wells; magnification × 100). E Number of lung metastatic nodules (The yellow arrows indicate representatively metastatic nodes in fresh lung; the red arrows indicate the nodes in fixed lung) in mice injected with Siha/LV-Ctrl, Siha/LV-NOD1, and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells (mouse harboring Siha/LV-Ctrl: n = 6, mouse harboring Siha/LV-NOD1: n = 6, mouse harboring Siha/LV-NOD2: n = 6). F Kaplan-Meier curves showing OS of the above tumor-bearing groups (n = 10 for each group). All data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001

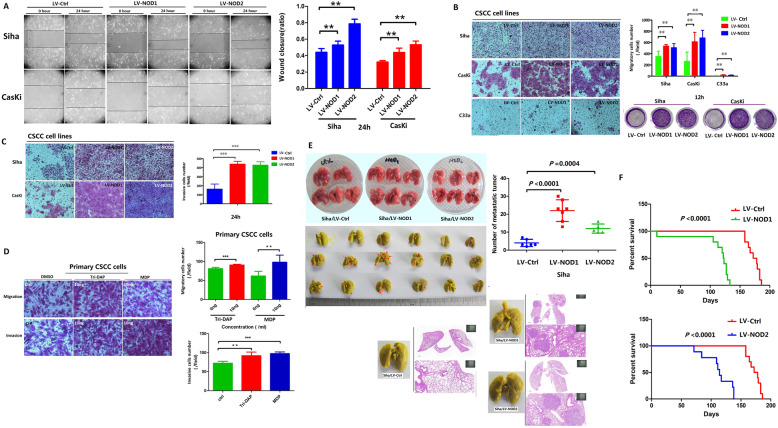

NOD1 and NOD2 enhanced the tumorigenic and metastatic potential of CSCC cells through multiple pathways

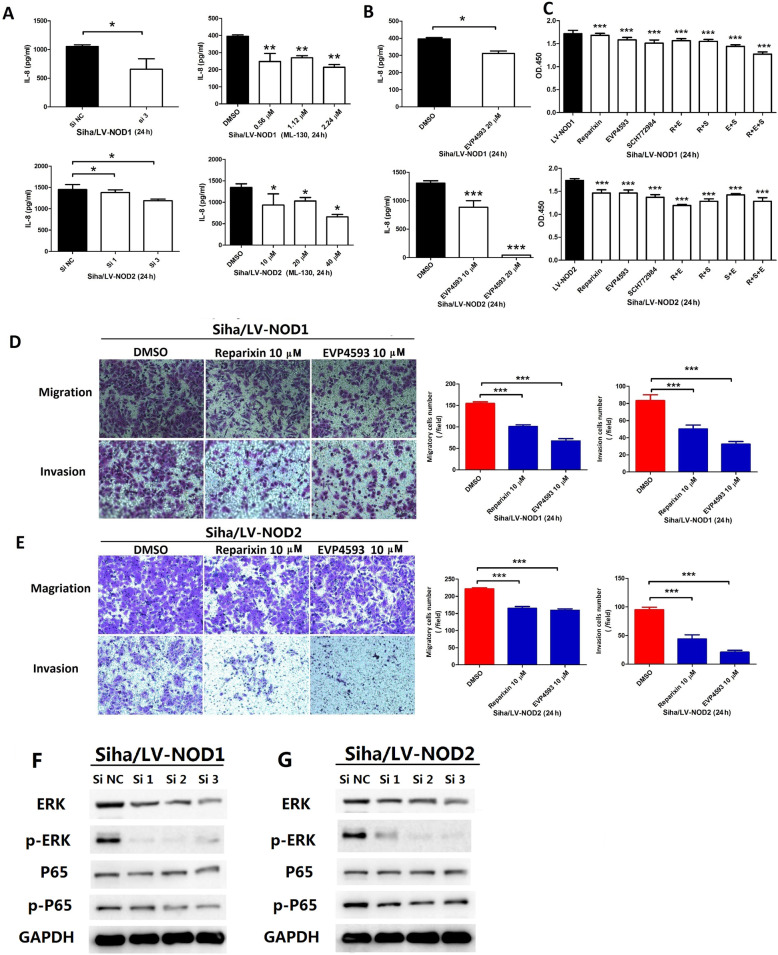

The mechanisms underlying the oncogenic effects of NOD1/NOD2 were further elucidated via pharmacological inhibition with ML-130 as well as siRNA-mediated gene knockdown (Additional file 4: Fig.S4). Inhibition of NOD1 or NOD2 significantly decreased the proliferative capacity (Fig. 4A, B), and the migration and invasion rates of Siha/LV-NOD1 or Siha/LV-NOD2 respectively (Fig. 4C) compared to the vehicle controls. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses further showed that the genes and proteins correlated with the upregulation of NOD1 or NOD2 were involved in cell proliferation, cytokines, and pathways in cancer such as ERK, NF-κB, and IL-8 (Fig. 4D–G). As shown in Fig. 4F, the ERK and NF-κB pathway proteins were also upregulated in the LV-NOD1 and LV-NOD2 cells. The quantity of cytokine in-cell array indicated that IL-6 and IL-8 were upregulated by NOD1 or NOD2 increasing (Fig. 4G upper panels); however, only significant higher IL-8 secretion by Siha/LV-NOD1 or Siha/LV-NOD2 was identified (Fig. 4G, down panels). NOD1/NOD2 increased the secretion of IL-8 but not of IL-6 (Fig. 4G, down panels), which was abrogated by their respective siRNAs (Fig. 5A, left panels) as well as ML-130 (Fig. 5A, right panels) and the NF-κB inhibitor (Fig. 5B). In addition, the proliferation ability of Siha/LV-NOD1 or Siha/LV-NOD2 was significantly inhibited by selective inhibitors of the IL-8 receptor CXCR1/2 (Reparixin), NF-κB (EVP4593), or ERK (SCH772984) (Fig. 5C), and the combination of all three showed a cumulative inhibitory effect (Fig. 5C). Reparixin and EVP4593 also decreased the metastatic potential of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells (Fig. 5D, E).

Fig. 4.

NOD1/NOD2 promote CSCC tumorigenesis by activating the ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways. A Proliferation rates of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 treated with 0.56 μM (upper) and 25 μM (lower) ML-130. B Proliferation of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells transfected with the NOD1 and NOD2 siRNAs. C Representative images of transwell assay showing the migration and invasion of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells with NOD1 or NOD2 knockdown. D Protein arrays showing the molecules and signaling pathways involved in the upregulation of NOD1 and NOD2 (data was merged with Siha and CasKi cells)—viral protein interactions (left), bacterial response (right), MAPK, and NF-κB signaling pathways (left) and ERK cascade (right). E GO analysis showing enriched proteins in Siha and CasKi cells transfected with LV-NOD1 or LV-NOD2 compared to LV-Ctrl. F Immunoblots showing expression of ERK/p-ERK and NF-κB/p-NF-κB in LV-NOD1 or LV-NOD2 CSCC cell lines (Siha and CasKi). G Representative cytokine array panels for Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells (upper panel) and cytokine levels validated by ELISA (lower panel). Data of CSCC cell lines represent triplicate independent experiment of representative one. The data of C and G were performed with triplicate wells. All data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

Fig. 5.

Reparixin inhibits NOD1/2-induced tumorigenesis of CSCC cells by inhibiting the secretion of IL-8. A IL-8 levels secreted by Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells with NOD1 and NOD2 knockdown (left panels), or ML-130 pretreatment (right panels). B IL-8 levels secreted by Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 treated with EVP4593 (NF-κB inhibitor). C Proliferation rates of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells treated with Reparixin (R), EVP4593 (E), SCH772984 (S), and their combination. D, E Representative images of transwell assays showing migration and invasion of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells treated with Reparixin or EVP4593. The percentages are shown on the right. ELISA and transwell assays were performed in triplicates and CCK8 assay in five replicates. F, G Immunoblot showing expression of ERK/p-ERK and NF-κB/p-NF-κB in the Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 CSCC cells (data are from three independent experiment) transfected with siRNAs. All data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

The enhanced IL-8 secretion by NOD1/NOD2-overexpressing Siha cells upregulated the adhesion molecule FN1 (Additional file 5: Fig.S5A), and knocking down FN1 inhibited metastasis of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells (Additional file 5: Fig.S5B). In addition, the elevated FN1 in Siha/LV-NOD1 or Siha/LV-NOD2 cells was downregulated by Reparixin (Additional file 5C). To summarize, the oncogenic effects of NOD1 and NOD2 in CSCC are mediated through multiple pathways; and knocking down either NOD1 or NOD2 in Siha cells downregulated P65/p-P65and ERK/p-ERK significantly (Fig. 5F, G).

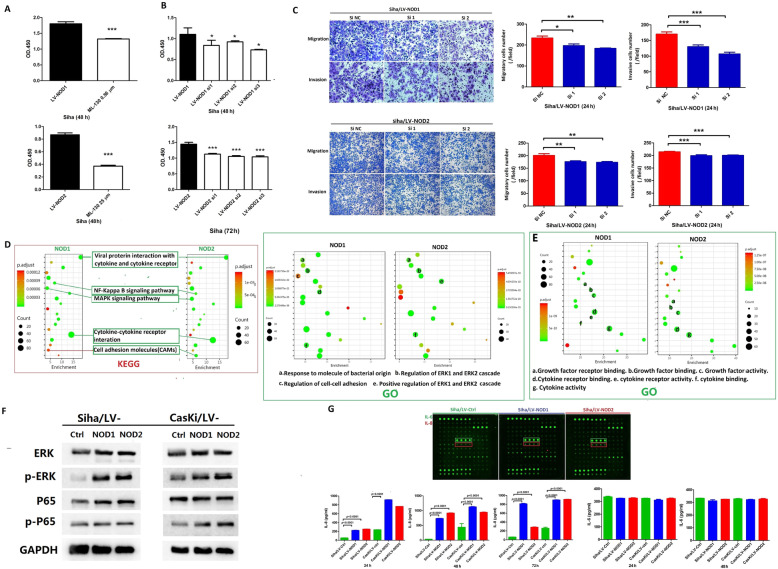

Reparixin prolonged the survival of mice harboring NOD1high tumors

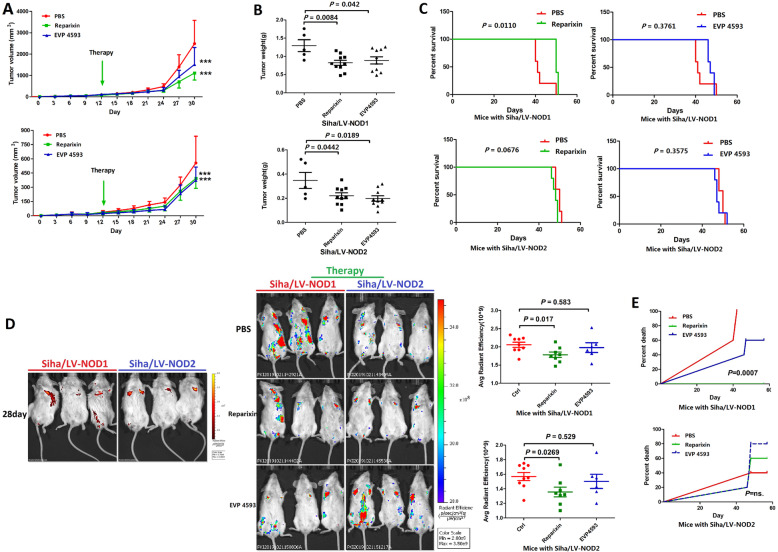

Consistent with the in vitro findings, Reparixin or EVP4593 markedly decreased the volume and weight (Fig. 6A, B) of tumors derived from mice with subcutaneous Siha/LV-NOD1 or Siha/LV-NOD2 cells compared to the untreated controls. Reparixin significantly improved the OS of mice bearing Siha/LV-NOD1 tumors subcutaneously (Fig. 6C). In the metastasis models induced by tail vein injection with Siha/LV-NOD1 or Siha/LV-NOD2 cells, Reparixin inhibited the growth of metastatic nodules compared to the placebo controls (Fig. 6D). Finally, Reparixin significantly improved the OS of mice with metastatic Siha/LV-NOD1 nodule xenografts (Fig. 6E). Taken together, the NOD1/ NF-κB/IL-8 axis is a promising therapeutic target in CSCC.

Fig. 6.

Reparixin inhibited growth of NOD1high and NOD2high CSCC tumors in vivo. A Volume of Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 tumors in the untreated (n = 5), Reparixin (n = 10), and EVP4593 (n = 10) groups. B Tumor weight in the Reparixin (n = 10), EVP4593 (n = 10), and PBS (n = 5) groups. C OS Kaplan-Meier curves of mice in the above groups. D Representative fluorescence images showing metastasis of GFP+ Siha/LV-NOD1 or Siha/LV-NOD2 cells in the indicated groups (mouse harboring GFP+ Siha/LV-NOD1: Group treated by PBS: n = 9; group treated by Reparixin: n = 8; group treated by EVP4593: n = 6. mouse harboring GFP+ Siha/LV-NOD2: Group treated by PBS: n = 9; group treated by Reparixin: n = 8; group treated by EVP4593: n = 6). Quantification of GFP intensity is shown on the right. E Survival curves of the above tumor-bearing mice treated with PBS, Reparixin, or EVP4593. The results are presented as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; * P < 0.05

Discussion

Metastatic and recurrent CSCC are highly recalcitrant tumors and challenging to treat. Previous study indicated several PRRs have been implicated in the progression of cervical cancer [23], the NLR family of PRRs has been identified in host immune defense [11, 29], and its members NOD1 and NOD2 are widely expressed in the female reproductive organs including endometrium, fallopian tubes, cervix, and ecto-cervix [27, 30, 31]. NOD1 plays an important role in the development of colon cancer and breast cancer [11, 20, 32, 33], and its dysregulation drives the progression of CIN to cervical cancer [27]. The correlation between NOD2 expression and tumorigenesis varies across different cancer types [33–36]. We detected higher levels of NOD1 and NOD2 in the CSCC tissues compared to the normal cervix. Furthermore, NOD1 was particularly overexpressed in tumors with LVSI, LM, and poor differentiation and associated with worse survival. NOD2 was elevated in the tumors with LVSI and poor differentiation, although its association with LM and survival was not as significant as observed with NOD1. In clinical characteristics, LVSI and LM associate with higher metastatic rate. The higher risk for worse prognosis is LM, and the Sedlis criteria include risk factor of LVSI for worse prognosis [37]. Our results also indicated that higher NOD1 or NOD2 expression was not associated with advanced tumor stages. As we know, advanced stage cervical cancer means worse OS; poor differentiation is not a definitely middle/high-risk factor for prognosis in patients with CSCC [38]. From the above results, we can predict that CSCC patients in the same stage with the higher NOD1 expression have worse prognosis. However, we collected the CSCC tissue from “Oct 2017 to Dec 2019” and most of these samples were from patients at early stages (IB1-IIA, FIGO 2009 staging system), and we could not get the powerful survival data from our enrolled patients (OS and DFS (disease free survival)) because of the relatively short follow-up period. Therefore, we abstracted the clinical characteristics from “TCGA” database and calculated the OS.

Furthermore, in a functional experiment, the ectopic expression of NOD1 or NOD2 in CSCC cell lines enhanced their proliferative and metastatic capacities in vitro and in vivo. Besides, we isolated and cultured primary CSCC cells for counterpart experiments of CSCC cell lines since there is a limited source of cell lines in the world. The upregulation of NOD1 in primary CSCC cells also increased the metastatic capacity in vitro as cell lines showed. This is consistent with the increased expression of NOD1 observed in colon cancer metastasis and breast cancer cell lines [33, 39]. However, Liu et al reported a suppressive role of NOD1 in CSCC [27], which might point to a differential function depending on the disease stage.

NOD1 and NOD2 stimulation by their respective ligand activates the ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways [33, 40, 41], and several studies have demonstrated NOD1/2-mediated phosphorylation of ERK and P65 [11, 12, 33, 36, 42, 43]. The activation of NF-κB and ERK pathways culminates in the upregulation in multiple downstream targets, such as IL-8 and fibronectin (FN1) [44–47]. FN1 is extravasated from the bloodstream into tissues and promotes tumor adhesion [39, 48] in response to increased IL-8 secretion [49]. Both TLRs and NODs are involved in CSCC progression [50], and upregulation of TLRs (such as TLR8) may also induce IL8 secretion [51]. Additionally, previous studies have demonstrated that the IL-8-CXCR1/2 axis is involved in the tumorigenesis and metastasis of multiple cancers [44, 52, 53] and the safety of ML-130 has not been examined by any clinical trial; we surmised that NF-κB/IL-8 are potential therapeutic targets in CSCC patients with metastasis.

Indeed, tumor progression was remarkably attenuated by the CXCR1/2 inhibitor Reparixin, whereas inhibition of NF-κB had limited effect given the involvement of multiple signaling pathways. Consistent with our findings, IL-8 and CXCR1/2 inhibitors significantly attenuated progression of breast cancer [54–56]. Anti-IL-8 treatment regimens are currently in the clinical testing phase for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (NCT04123379, recruiting), and early (NCT01861054) and metastatic breast cancer (NCT02001974). Interestingly, Reparixin significantly improved the survival of mice bearing metastatic Siha/LV-NOD1 tumors but its therapeutic effect was less pronounced in the Siha/LV-NOD2 group.

Conclusions

In summary, NOD1 is a potential biomarker of worse prognosis in CSCC patients. Both NOD1 and NOD2 enhanced the proliferative and metastatic abilities of CSCC cells by promoting IL-8 secretion via the NF-κB pathways. Furthermore, Reparixin is a promising agent against CSCC and should be further examined in a clinical setting in NOD1-positive populations with metastatic CSCC.

Methods

Patient samples and clinicopathological data

Specimen collection and clinicopathological data review were approved by the Ethics Committee of Cancer Hospital, CAMS (Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College). This study was performed in accordance with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS), and none of the procedures conducted in this study interfered with the treatment plan of the patients. CSCC tissues were collected during surgery or biopsies conducted between Oct 2017 and Dec 2019 at the Cancer Hospital, after obtaining consent from the patients. Totally, fifty-eight CSCC samples and thirty-three normal cervix tissue samples were used for the quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay, and 143 CSCC samples were collected for immunohistochemistry (IHC). Sixteen tumor samples were used for primary cell isolation and subsequent assays.

Transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

The NOD1 and NOD2 expression data of CSCC patients was extracted from the Human Protein Atlas (http://www.proteinatlas.org), and the mRNA expression and survival data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) databases. The transcriptome sequencing (differential expression genes, DEG) of CSCC and normal cervical tissue (from Cancer Hospital) were identified by BGISEQ platform and analyzed on the DR. TOM network platform of BGI (https://biosys.bgi.com/#/report/login). The sequencing reads which contain low-quality, adaptor-polluted, and high content of unknown base (N) reads should be processed to be removed before downstream analyses. After sequencing data filtering, DEG level was calculated for each sample with RSEM [57]. The target genes were functionally annotated by Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses, and the significant biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions were identified.

Cell culture

The human CSCC cell lines Siha, CasKi, and C33a were all purchased from Cell Resource Center (Beijing, China). The cell lines were verified by short tandem repeat (STR) sequencing by the Beijing Microread Genetics Company on July 2018. The cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PS) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 37 °C under 5% CO2 (Thermo Technologies, Vancouver, Japan). The cells were treated with Tri-DAP, MDP (InvivoGen, USA), ML-130 (TargetMol, USA), CXCR1/2 inhibitor (Reparixin, Med Chem Express, USA), NF-κB inhibitor (EVP4593, Sellect, USA), or ERK inhibitor (SCH772984, Sellect, USA) as required. Primary CSCC cells were isolated from patient samples as previously described [58]. Briefly, the specimens were minced into 1-mm3 pieces in 6-cm petri dishes, and sequentially digested with 0.05% trypsin containing EDTA (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) and 0.2% type I collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St Louis, MO, USA) at 37 °C with constant shaking. FBS was added to terminate the reaction, and the cells were washed and re-suspended in DMEM/F12 complete medium with 5% FBS (Gibco). The primary cells were seeded in a petri dish and cultured for 7–10 days.

MACS and flow cytometry

Trypsinized primary CSCC cells were re-suspended in MACS (magnetic-activated cell sorting) separation buffer and incubated with anti-EpCAM magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec Inc, Auburn, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, the EpCAM-positive cells were collected and cultured in high-glucose DMEM medium with FBS (5%). Flow cytometry (FCM) was used to identify the purity of the CSCCs immediately after cell sorting or a short period of culture: Purified primary cells were stained with fluorescent-conjugated antibodies against anti-human EpCAM FITC (BioLegend Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and anti-human vimentin PE (Miltenyi Biotec Inc, Auburn, CA, USA) on ice. Since vimentin was the cellular marker used, the cells were pretreated with Fixation/Permeabilization reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the protocols recommended by the manufacturer. FCM acquisition was performed using a Beckman coulter-Dxflex flow cytometer. Flow Jo V10 software was used for the data analysis. The purity of the sorted cells reached ∽ 96% purity. After the purification was identified, the cells were collected and cultured for functional examination.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cultured cells and frozen tissues using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The quality and concentration of the RNA were determined using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). The RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Takara, Japan) and amplified by RT-qPCR using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life, Applied Biosystems) on the Step One Plus Real-Time PCR System (Life, Applied Biosystems). The target gene expression levels were calculated with the 2−ΔΔCt method, and each sample was analyzed in triplicates. The primers were synthesized by Sangon Technologies (Shanghai, Corp.) and the sequences were as follows:

NOD1:FW5′-TACTGAAAAGCAATCGGGAACT,

RW: 5′-GTAGAGGAAGAACTCGGACACC;

NOD2: FW: 5′-TGCGGACTCTACTCTTTGAGC,

RW: 5′-CCGTGAACCTGAACTTGAACT;

GAPDH: FW: 5′-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC,

RW: 5′-TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining (HE) and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The tissue samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm-thick sections, and coated at 75 °C for 2 h. The sections were deparaffinized using xylene and rehydrated through an ethanol gradient. HE staining was performed as standard protocols. For IHC, the sections were heated in citrate buffer for antigen retrieval, incubated with 2% hydrogen peroxide for quenching endogenous peroxidase, and blocked using 1% goat serum (ZSJQ, Beijing, China). The slices were then incubated overnight with rabbit anti-human vimentin (without diluted, Origene, Beijing, China), mouse anti-human pan-cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (without diluted, Origene, Beijing, China), mouse anti-human Ki67 (diluted 1:200, ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China), mouse anti-human P16 (diluted 1:200, ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China), mouse anti-human NOD1 (B-4; dilution: 1:100; sc-398696, Santa Cruz, USA), and mouse anti-human NOD2 (2D9; dilution: 1:100; sc-56168, Santa Cruz, USA) antibodies and the isotype control at 4 °C. After washing with PBST (Phosphate Buffer Solution with Tween-20), the sections were sequentially stained with DAB chromogen (diaminobezidin, ZSJQ, Beijing, China) and hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). NOD1 and NOD2 expression parameters were scored by Image Pro Plus software (USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

The cells cultured on chamber slides were fixed with cold 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated overnight with rabbit anti-human vimentin (diluted 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), mouse anti-human AE1/AE3 (diluted 1:100, ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China), rabbit anti-human CDKN2A/p16INK4a (P16) (diluted 1:200, Abcam), mouse anti-human NOD1 (B-4; dilution: 1:100; sc-398696, Santa Cruz), and mouse anti-human NOD2 (2D9; dilution: 1:100; sc-56168, Santa Cruz) primary antibodies. The slides were then incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature and counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Cat.H3570, Life Technologies). The stained tissues and cells were viewed using Olympus scanner or laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM780; Zeiss), and the staining intensity was evaluated by a pathologist blinded to the samples using image plus software (USA).

Lentiviral transduction

Human NOD1 (BC040339.1) and NOD2 (NM022162.2) were respectively cloned into the pLVX-P2A-ZsGreen-T2A-Puro vector at the XhoI and BamHI sites. The lentivirus with pLVX-hNOD1/hNOD2-ZsGreen-Puro was purchased and packaged as per the manufacturer’s description (Likeli Biotec Inc, Beijing, China USA). The CSCC cell lines (Siha, CasKi and C33a) were transduced with the NOD1/NOD2 or empty vector lentiviruses and selected using puromycin. NOD1/2 overexpression was verified by western blotting.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

NOD1, NOD2, FN1, and scrambled siRNAs were synthesized by JTS Scientific Company (Beijing, China). The sequences are as follows:

NOD1: Si1 (866) - CCUGCUCACUCAGAGCAAAtt, UUUGCUCUGAGUGAGCAGGtt

Si2 (1240) - GCAUGUUCAGCUGCUUCAAtt, UUGAAGCAGCUGAACAUGCtt

Si3 (2095) - CCUUCUUUACAGCCUUCUUtt, AAGAAGGCUGUAAAGAAGGtt

NOD2: Si1 (952) - GCAAGAAGUAUAUGGCCAAtt, UUGGCCAUAUACUUCUUGCtt

Si2 (1253) - GCAAGACUUCCAGGAAUUUtt, AAAUUCCUGGAAGUCUUGCtt

Si3 (2798) - GCUCAUUGAAUGUGCUCUUtt, AAGAGCACAUUCAAUGAGCtt

FN1 - CCAUUUCACCUUCAGACAAtt, UUGUCUGAAGGUGAAAUGGtt

The Siha/LV-NOD1, Siha/LV-NOD2, CasKi/LV-NOD1, and CasKi /LV-NOD2 cell lines were grown till 70% confluency and transfected with the respective siRNAs using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, siRNA and 1 μl Lipofectamine™ 2000 was respectively diluted in 50 μl Opti-MEM, incubated for 15 min at room temperature, and then mixed. The mixture was incubated for 15 min at room temperature and added to each well. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the transfection efficacy was tested.

Human cytokine array, western blotting, and ELISA

The cultured cells were harvested for cytokine array and western blotting, and the supernatants were collected for ELISA. The cytokine levels were analyzed with the G-Series Human Cytokine Antibody Array 440 as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Ray Biotech Inc. Quantibody service, China). Western blotting was performed using standard protocols after the cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) [59]. The following primary antibodies were used: β-actin (AC-15; 1:2000; Sigma), NOD1 (mouse anti-human, B-4; 1:500; sc-398696, Santa Cruz), NOD2 (mouse anti-human, 2D9; 1:500; sc-56168, Santa Cruz), P65 (rabbit anti-human, D14E12, 1:1000; CST, USA), p-P65 (rabbit anti-human, 93H1, 1:1000; CST, USA), P44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (rabbit anti-human, 1:1000; CST, USA), and pP44/42 MAPK (pERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204, rabbit anti-human, 1:1000, CST, USA). The IL-8 and IL-6 levels in the supernatants were quantified using LEGEND MAX™ Human IL-8 and Human IL-6 ELISA Kits (Biolegend, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell counting and CCK8 assays

Cells were seeded in 6-cm petri dishes at the logarithmic phase of growth, and harvested after 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h, respectively. The number of cells was recorded using a cell counter II (Life Corp, USA). The cells were seeded into 96-well plates for the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay (Dojindo Laboratories, Japan), and 10 μl CCK8 solution was added per well at 24, 48, and 72 h of culture. The optical density at 450 nm (OD.450) was measured using a Model 680 Microplate Reader (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA). Five replicates were tested per sample.

Cell cycle profiling

The transfected cells were seeded into 12-well plates and cultured for 24 h. After fixing in cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min and permeabilizing with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min, the cells were incubated with EdU (5-Ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine) (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) for proliferation. The cells were then washed thrice with PBS, counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology, China), and observed under a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM780; Zeiss). For FCM, the cells were harvested, washed sequentially with citrate buffer and PBS, and incubated with ribonuclease (RNAase) and propidium iodide (PI) (Ref. CYT-PIR-25, Cytognos, Spain) at room temperature for 1 h. The stained cells were acquired in a flow cytometer (Beckman coulter-Dxflex) and analyzed by the Flow Jo V10 software.

Colony formation assay

The primary cells and cell lines were seeded in six-well plates at the respective densities of 800 cells/well and 500 cells/well. After culturing for 10–14 days, the cells were fixed with cold 4% PFA and stained with crystal violet (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

Wound healing assay

Siha/LV-Ctrl/NOD1/NOD2 and CasKi/LV-Ctrl/NOD1/NOD2 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at the density of 1 × 106 cells/well in complete DMEM/F12 (10% FBS). After 24 h of culture, the monolayer was scratched using a 10-μl pipette tip, and the wound region was measured at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h under a microscope. The wound healing rate at the different time points was quantified as the width of the wound region relative to the initial width at 0 h.

Transwell assay

The different cell lines and primary cells were seeded into transwell chambers (Costar, Cambridge, MA) at the respective densities of 3–5 × 104 cells/well and 0.5–1 × 105 cells/well in 200 μl serum-free DMEM/F12. The lower chambers were filled with 600 μl complete DMEM/F12 (10% FBS). After 20–24 h of incubation, the cells that had migrated through the membrane were fixed and stained, and counted in four randomly chosen fields. The invasive capacity of the cells was similarly analyzed using Matrigel-coated (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) transwell membranes.

In vivo experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission, and conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines. The xenograft model was established by subcutaneously inoculating 8-week-old BALB/c nude mice or 7–8 weeks NOD/SCID mice with 3 × 106 Siha/LV-Ctrl/NOD1/NOD2 cells and bilaterally. Palpable tumors (> 3 mm) appeared 7 days after injection and were measured every 3 days. The mice were euthanized 28–56 days post-inoculation, and the tumors were removed and weighed. The lung metastasis model was established by intravenously injecting 8–9-week-old NOD/SCID mice with 1 × 106 Siha/LV-Ctrl/NOD1/NOD2 cells. Metastatic growth in the lungs was detected by labeling with luciferase or GEP. The mice were sacrificed 56–84 days, and the number of metastatic nodules was counted. For the treatment regimen, the tumor-bearing mice were divided into the placebo control, Reparixin, and EVP-4395 groups, and the tumor growth was monitored as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 software, and GraphPad Prism 5.0 software was used for plotting graphs. Quantitative variables between two groups were compared by Student’s t test (normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal distribution), and one-way or two-way ANOVA was used for comparing multiple groups. Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare qualitative variables. Survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. The IHC scores of NOD1 and NOD2 expression levels. A) Representative images of HE-stained human CSCC tissues (n = 113, magnification 10╳), P16 and/or Ki67 and/or CK immunostaining, and AE1/AE3 and vimentin immunofluorescence (n = 6; scale bar - 30 μm). B) DEGs by Venn diagrams (left panel): the red number represents the up-regulated gene amount, blue number represents the downregulated gene amount; Scatter plot (right panel): hierarchical clustering of 5,140 upregulated mRNAs, using X Y axis represents log10 transformed gene expression level, red color represents the up-regulated genes, blue color represents the downregulated genes, gray color represents the non-DEGs (Normal cervix, n = 4; cervical cancer, n = 6). C) IHC scores for NOD1 and NOD2 in the early and advanced stage tumors (for NOD1, I-II stages: n = 39, III-IV stages: n = 53; for NOD2, I-II stages: n = 34, III-IV stages: n = 52). D) IHC scores of NOD1 and NOD2 in tumors of different grades (for NOD1, high and middle: n = 46, poor: n = 60; for NOD2, high and middle: n = 43, poor: n = 50). E) The positive correlation mRNA expression of NOD1 and NOD2 was identified by database (n = 306, http://timer.cistrome.org). F) Kaplan–Meier curves showing overall survival of CSCC patients demarcated on the basis of in situ NOD1 and NOD2 expression (http://www.proteinatlas.org). All data are presented as mean ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Additional file 2. NOD1/2 expression in primary CSCC cells and CSCC cell lines. A) Morphology of the cultured Siha, Caski, C33a cell lines and the primary CSCC cells (left). EpCAM positive cells were sorted by MACS and identified by FCM (middle). The continuum of cultured primary CSCC cells were confirmed using immunofluorescence (AE1/AE3+ and P16+ and vimentin) (right). B) The level of NOD1 and NOD2 in CSCC cell lines and primary cells was upregulated through pretreatment by specific ligands (10 ng/mL) at 24 h by qPCR (upper) and in-cell immunofluorescence staining (lower). C) Stable NOD1 and NOD2 expression in the cultured Siha, CasKi and C33a cell lines were confirmed by green fluorescence (GFP flag), qPCR and western blotting.

Additional file 3. NOD1 and NOD2 enhanced the tumorigenic and metastatic abilities of CSCC cells. A) The percentages of wound healing, while data on C33a wound closure was normalized using the wound length at 0 h (left, 24 h and 48 h). The image on the right shows the percentage of wound closure of the Siha and CasKi cells, which were normalized to the wound length at 0 h (48 h). B) The weights of mice injected with different cell lines. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Additional file 4. Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells transfected by siRNA. The expression of NOD1 mRNA (A, data were from three independent experiments with three replicates) and protein (B, the picture is a representative from two independent experiments). SiRNA was presented as Si1, Si2 and Si3.

Additional file 5. Over-expression of NOD1 or NOD2 of Siha cells promotes FN1 and IL-8. A) Representative results of adhesion and invasion molecules with over-expression of NOD1/NOD2. (Siha cells, two independent experiments using triplicated wells). B) Transwell assays revealed that the migration and invasion abilities of the Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells were inhibited by knock down FN1. C) Reparixin downregulates FN1 mRNA expression.

Acknowledgements

We give our sincere thanks to Chong Wang for the data review.

Abbreviations

- CSCC

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- IL-8

Interleukin-8

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry staining

- qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- CI

Cell Index

- mRNA

Messenger RNA

- H&E staining

Hematoxylin-eosin staining

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- LVSI

Lympho-vascular space invasion

- LM

Lymph nodes metastasis

- FCM

Flow cytometry

- HPV

Human papilloma virus

- PRRs

Paternal recognition receptors

- PD-1/ PDL-1

Program death-1/ program death ligand-1

- NLRs

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor

- TLR

Toll like receptors

- NOD

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain receptor

- meso-DAP

Meso-diaminopimelic acid

- MDP

Muramyl dipeptide

- MACS

Magnetic-activated cell sorting

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- EdU

5-Ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered Saline

- PFA

Paraformaldehyde

- OS

Overall survival

- CCR1-2

IL-8 receptor

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: YZ and LW; Development of methodology: YZ, ML, DZ, WW, JZ and GZ; Managed patients: NL1, GY, HY, YS and GZ; Acquired and provided facilities: ML; Statistical analysis, biostatistics: HY and NL2; computational analysis: YZ; Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: YZ, ML and LW; Administrative, technical, or material support: ML and NX. Study supervision: LW. All author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972450, 81601261 and 82173333) for Dr. Lingying Wu and Dr. Yuanyuan Zhang and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018 M631395) for Dr. Yuanyuan Zhang.

Availability of data and materials

The NOD1 and NOD2 expression data of CSCC patients was extracted from the Human Protein Atlas (http://www.proteinatlas.org), and the mRNA expression and survival data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) databases. The target genes were functionally annotated by Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway analyses, and the significant biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions were identified.

The primary experiment data and material can be obtained from the correspondence with reasonable require.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Specimen collection and clinicopathological data review protocols used in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Cancer Hospital, CAMS (Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College (NCC2018-070 and NCC2019C-010). This study was performed in accordance with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS) and neither of the procedures conducted interfered with the treatment plan of the patient. All animal experiments were approved by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission and conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines. The Ethics approval number of animal experiments: NCC2019A037.

Specimens were obtained with the informed consent of all patients involved. These specimens collected included primary cell culture and constructed continuing cell lines.

Consent for publication

All of the authors consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuanyuan Zhang, Email: zyyyyz026@163.com.

Ning Li, Email: liningnci@126.com.

Guangwen Yuan, Email: william327@126.com.

Hongwen Yao, Email: absurgeonyao@163.com.

Die Zhang, Email: 2113126781@qq.com.

Nan Li, Email: concerto2000@126.com.

Gongyi Zhang, Email: samuel000816@sina.com.

Yangchun Sun, Email: sych18@163.com.

Wenpeng Wang, Email: wangwenpeng0224@126.com.

Jia Zeng, Email: zack.zeng@yahoo.com.

Ningzhi Xu, Email: xuningzhi@cicams.ac.cn.

Mei Liu, Email: liumei@cicams.ac.cn.

Lingying Wu, Email: wulingying@csco.org.cn.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International journal of cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, de Sanjose S, Saraiya M, Ferlay J, Bray F. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. The Lancet Global health. 2020;8(2):e191–e203. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30482-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the cervix uteri. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics. 2018;143(Suppl 2):22–36. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brisson M, Kim JJ, Canfell K, Drolet M, Gingras G, Burger EA, Martin D, Simms KT, Benard E, Boily MC, et al. Impact of HPV vaccination and cervical screening on cervical cancer elimination: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):575–590. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30068-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canfell K, Kim JJ, Brisson M, Keane A, Simms KT, Caruana M, Burger EA, Martin D, Nguyen DTN, Benard E, et al. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):591–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30157-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The L Eliminating cervical cancer. Lancet. 2020;395(10221):312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vu M, Yu J, Awolude OA, Chuang L. Cervical cancer worldwide. Current problems in cancer. 2018;42(5):457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N: Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. The Journal of pathology. 1999;189(1):12-19. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1 < 12::AID-PATH431 > 3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kalliala I, Athanasiou A, Veroniki AA, Salanti G, Efthimiou O, Raftis N, Bowden S, Paraskevaidi M, Aro K, Arbyn M, Bennett P, Nieminen P, Paraskevaidis E, Kyrgiou M. Incidence and mortality from cervical cancer and other malignancies after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2020;31(2):213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girardin SE, Tournebize R, Mavris M, Page AL, Li X, Stark GR, Bertin J, DiStefano PS, Yaniv M, Sansonetti PJ, et al. CARD4/Nod1 mediates NF-kappaB and JNK activation by invasive Shigella flexneri. EMBO reports. 2001;2(8):736–742. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogura Y, Inohara N, Benito A, Chen FF, Yamaoka S, Nunez G. Nod2, a Nod1/Apaf-1 family member that is restricted to monocytes and activates NF-kappaB. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276(7):4812–4818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carneiro LA, Travassos LH, Philpott DJ. Innate immune recognition of microbes through Nod1 and Nod2: implications for disease. Microbes and infection. 2004;6(6):609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Carneiro LA, Antignac A, Jehanno M, Viala J, Tedin K, Taha MK, Labigne A, Zahringer U, et al. Nod1 detects a unique muropeptide from gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science. 2003;300(5625):1584–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1084677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278(11):8869–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu RY, Chan CH, Spicer JD, Rousseau MC, Giannias B, Rousseau S, Ferri LE. LPS-induced TLR4 signaling in human colorectal cancer cells increases beta1 integrin-mediated cell adhesion and liver metastasis. Cancer research. 2011;71(5):1989–1998. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim S, Karin M. Role of TLR2-dependent inflammation in metastatic progression. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1217(1):191–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cario E. The human TLR4 variant D299G mediates inflammation-associated cancer progression in the intestinal epithelium. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(7):e24890. doi: 10.4161/onci.24890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang P, Zhang L, Jiang JM, Ma D, Tao HX, Yuan SL, Wang YC, Wang LC, Liang H, Zhang ZS, Liu CJ. Association of NOD1 and NOD2 genes polymorphisms with Helicobacter pylori related gastric cancer in a Chinese population. World journal of gastroenterology. 2012;18(17):2112–2120. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang HY, Najmeh S, Martel G, MacFadden-Murphy E, Farias R, Savage P, Leone A, Roussel L, Cools-Lartigue J, Gowing S, Berube J, Giannias B, Bourdeau F, Chan CHF, Spicer JD, McClure R, Park M, Rousseau S, Ferri LE. Activation of the pattern recognition receptor NOD1 augments colon cancer metastasis. Protein & cell. 2020;11(3):187–201. doi: 10.1007/s13238-019-00687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millrud CR, Kvarnhammar AM, Tajti J, Munck-Wikland E, Uddman R, Cardell LO. Nod-like receptors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2013;133(12):1333–1344. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2013.831476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Jiang W, Duan N, Qian Y, Zhou Q, Ye P, Jiang H, Bai Y, Zhang W, Wang W. NOD1, RIP2 and Caspase12 are potentially novel biomarkers for oral squamous cell carcinoma development and progression. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2014;7(4):1677–1686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halec G, Scott ME, Farhat S, Darragh TM, Moscicki AB. Toll-like receptors: Important immune checkpoints in the regression of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia 2. International journal of cancer. 2018;143(11):2884–2891. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Husseinzadeh N, Davenport SM. Role of toll-like receptors in cervical, endometrial and ovarian cancers: a review. Gynecologic oncology. 2014;135(2):359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghosh A, Dasgupta A, Bandyopadhyay A, Ghosh T, Dalui R, Biswas S, Banerjee U, Basu A. A study of the expression and localization of toll-like receptors 2 and 9 in different grades of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Experimental and molecular pathology. 2015;99(3):720–724. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang LS, Leng CH, Yeh YC, Wu CC, Chen HW, Huang HM, Liu SJ. Toll-like receptor 9 agonist enhances anti-tumor immunity and inhibits tumor-associated immunosuppressive cells numbers in a mouse cervical cancer model following recombinant lipoprotein therapy. Molecular cancer. 2014;13(1):60. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Ma H, Fei L, Jiang M, Xia M, Bai L, Pi X, Chen S, Yu L. HPV-mediated down-regulation of NOD1 inhibits apoptosis in cervical cancer. Infectious agents and cancer. 2020;15(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13027-020-0272-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swaminathan V, Mythreye K, O'Brien ET, Berchuck A, Blobe GC, Superfine R. Mechanical stiffness grades metastatic potential in patient tumor cells and in cancer cell lines. Cancer research. 2011;71(15):5075–5080. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim YG, Park JH, Shaw MH, Franchi L, Inohara N, Nunez G. The cytosolic sensors Nod1 and Nod2 are critical for bacterial recognition and host defense after exposure to Toll-like receptor ligands. Immunity. 2008;28(2):246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King AE, Horne AW, Hombach-Klonisch S, Mason JI, Critchley HO. Differential expression and regulation of nuclear oligomerization domain proteins NOD1 and NOD2 in human endometrium: a potential role in innate immune protection and menstruation. Molecular human reproduction. 2009;15(5):311–319. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart KM, Murphy AJ, Barrett KT, Wira CR, Guyre PM, Pioli PA. Functional expression of pattern recognition receptors in tissues of the human female reproductive tract. Journal of reproductive immunology. 2009;80(1-2):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velloso FJ, Sogayar MC, Correa RG. Expression and in vitro assessment of tumorigenicity for NOD1 and NOD2 receptors in breast cancer cell lines. BMC research notes. 2018;11(1):222. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3335-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Velloso FJ, Campos AR, Sogayar MC, Correa RG. Proteome profiling of triple negative breast cancer cells overexpressing NOD1 and NOD2 receptors unveils molecular signatures of malignant cell proliferation. BMC genomics. 2019;20(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu D, Zhang S, Zhang S, Liu H, Li P, Yu L, Shang H, Hou Y, Tian Y. NOD2 maybe a biomarker for the survival of kidney cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(60):101489–101499. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma X, Qiu Y, Sun Y, Zhu L, Zhao Y, Li T, Lin Y, Ma D, Qin Z, Sun C, Han L. NOD2 inhibits tumorigenesis and increases chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting AMPK pathway. Cell death & disease. 2020;11(3):174. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2368-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Udden SMN, Peng L, Gan JL, Shelton JM, Malter JS, Hooper LV, Zaki MH. NOD2 suppresses colorectal tumorigenesis via downregulation of the TLR pathways. Cell reports. 2017;19(13):2756–2770. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao L, Wen H, Feng Z, Han X, Zhu J, Wu X. Role of adjuvant therapy after radical hysterectomy in intermediate-risk, early-stage cervical cancer. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2021;31(1):52–58. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2021;155(Suppl 1):28–44. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang HY, Najmeh S, Martel G, MacFadden-Murphy E, Farias R, Savage P, Leone A, Roussel L, Cools-Lartigue J, Gowing S, et al. Activation of the pattern recognition receptor NOD1 augments colon cancer metastasis. Protein Cell. 2020;11(3):187–201. 10.1007/s13238-019-00687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Park JH, Kim YG, Shaw M, Kanneganti TD, Fujimoto Y, Fukase K, Inohara N, Nunez G. Nod1/RICK and TLR signaling regulate chemokine and antimicrobial innate immune responses in mesothelial cells. Journal of immunology. 2007;179(1):514–521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tada H, Aiba S, Shibata K, Ohteki T, Takada H. Synergistic effect of Nod1 and Nod2 agonists with toll-like receptor agonists on human dendritic cells to generate interleukin-12 and T helper type 1 cells. Infection and immunity. 2005;73(12):7967–7976. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.7967-7976.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Nunez G. Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity. 2007;27(4):549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saxena M, Yeretssian G. NOD-like receptors: master regulators of inflammation and cancer. Frontiers in immunology. 2014;5:327. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vavricka SR, Musch MW, Chang JE, Nakagawa Y, Phanvijhitsiri K, Waypa TS, Merlin D, Schneewind O, Chang EB. hPepT1 transports muramyl dipeptide, activating NF-kappaB and stimulating IL-8 secretion in human colonic Caco2/bbe cells. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5):1401–1409. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masamune A, Kikuta K, Watanabe T, Satoh K, Hirota M, Hamada S, Shimosegawa T. Fibrinogen induces cytokine and collagen production in pancreatic stellate cells. Gut. 2009;58(4):550–559. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.154401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayashi R, Yamashita N, Matsui S, Fujita T, Araya J, Sassa K, Arai N, Yoshida Y, Kashii T, Maruyama M, Sugiyama E, Kobayashi M. Bradykinin stimulates IL-6 and IL-8 production by human lung fibroblasts through ERK- and p38 MAPK-dependent mechanisms. The European respiratory journal. 2000;16(3):452–458. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.016003452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sankpal NV, Fleming TP, Gillanders WE. EpCAM modulates NF-kappaB signaling and interleukin-8 expression in breast cancer. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2013;11(4):418–426. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin TC, Yang CH, Cheng LH, Chang WT, Lin YR, Cheng HC. Fibronectin in cancer: friend or foe. Cells. 2019;9(1). 10.3390/cells9010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Mohamed MM. Monocytes conditioned media stimulate fibronectin expression and spreading of inflammatory breast cancer cells in three-dimensional culture: a mechanism mediated by IL-8 signaling pathway. Cell communication and signaling : CCS. 2012;10(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Yang H, Barnie PA, Yang P, Su Z, Chen J, Jiao Z, Lu L, Wang S, Xu H. The expression of Toll-like receptor 8 and its relationship with VEGF and Bcl-2 in cervical cancer. International journal of medical sciences. 2014;11(6):608–613. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pluta L, Yousefi B, Damania B, Khan AA. Endosomal TLR-8 senses microRNA-1294 resulting in the production of NFkB dependent cytokines. Frontiers in immunology. 2019;10:2860. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouris P, Manou D, Sopaki-Valalaki A, Kolokotroni A, Moustakas A, Kapoor A, Iozzo RV, Karamanos NK, Theocharis AD. Serglycin promotes breast cancer cell aggressiveness: Induction of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, proteolytic activity and IL-8 signaling. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2018;74:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Q, Li A, Tian Y, Wu JD, Liu Y, Li T, Chen Y, Han X, Wu K. The CXCL8-CXCR1/2 pathways in cancer. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2016;31:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jayatilaka H, Tyle P, Chen JJ, Kwak M, Ju J, Kim HJ, Lee JSH, Wu PH, Gilkes DM, Fan R, Wirtz D. Synergistic IL-6 and IL-8 paracrine signalling pathway infers a strategy to inhibit tumour cell migration. Nature communications. 2017;8(1):15584. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ginestier C, Liu S, Diebel ME, Korkaya H, Luo M, Brown M, Wicinski J, Cabaud O, Charafe-Jauffret E, Birnbaum D, Guan JL, Dontu G, Wicha MS. CXCR1 blockade selectively targets human breast cancer stem cells in vitro and in xenografts. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120(2):485–497. doi: 10.1172/JCI39397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldstein LJ, Perez RP, Yardley D, Han LK, Reuben JM, Gao H, McCanna S, Butler B, Ruffini PA, Liu Y, Rosato RR, Chang JC. A window-of-opportunity trial of the CXCR1/2 inhibitor reparixin in operable HER-2-negative breast cancer. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2020;22(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13058-019-1243-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC bioinformatics. 2011;12(1):323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, An J, Liu M, Li N, Wang W, Yao H, Li N, Yang X, Sun Y, Xu N, Wu L. Efficient isolation, culture, purification, and stem cell expression profiles of primary tumor cells derived from uterine cervical squamous cell carcinoma. American journal of reproductive immunology. 2020;84(2):e13251. doi: 10.1111/aji.13251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou C, Liu S, Zhou X, Xue L, Quan L, Lu N, Zhang G, Bai J, Wang Y, Liu Z, Zhan Q, Zhu H, Xu N. Overexpression of human pituitary tumor transforming gene (hPTTG), is regulated by beta-catenin /TCF pathway in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. International journal of cancer. 2005;113(6):891–898. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. The IHC scores of NOD1 and NOD2 expression levels. A) Representative images of HE-stained human CSCC tissues (n = 113, magnification 10╳), P16 and/or Ki67 and/or CK immunostaining, and AE1/AE3 and vimentin immunofluorescence (n = 6; scale bar - 30 μm). B) DEGs by Venn diagrams (left panel): the red number represents the up-regulated gene amount, blue number represents the downregulated gene amount; Scatter plot (right panel): hierarchical clustering of 5,140 upregulated mRNAs, using X Y axis represents log10 transformed gene expression level, red color represents the up-regulated genes, blue color represents the downregulated genes, gray color represents the non-DEGs (Normal cervix, n = 4; cervical cancer, n = 6). C) IHC scores for NOD1 and NOD2 in the early and advanced stage tumors (for NOD1, I-II stages: n = 39, III-IV stages: n = 53; for NOD2, I-II stages: n = 34, III-IV stages: n = 52). D) IHC scores of NOD1 and NOD2 in tumors of different grades (for NOD1, high and middle: n = 46, poor: n = 60; for NOD2, high and middle: n = 43, poor: n = 50). E) The positive correlation mRNA expression of NOD1 and NOD2 was identified by database (n = 306, http://timer.cistrome.org). F) Kaplan–Meier curves showing overall survival of CSCC patients demarcated on the basis of in situ NOD1 and NOD2 expression (http://www.proteinatlas.org). All data are presented as mean ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Additional file 2. NOD1/2 expression in primary CSCC cells and CSCC cell lines. A) Morphology of the cultured Siha, Caski, C33a cell lines and the primary CSCC cells (left). EpCAM positive cells were sorted by MACS and identified by FCM (middle). The continuum of cultured primary CSCC cells were confirmed using immunofluorescence (AE1/AE3+ and P16+ and vimentin) (right). B) The level of NOD1 and NOD2 in CSCC cell lines and primary cells was upregulated through pretreatment by specific ligands (10 ng/mL) at 24 h by qPCR (upper) and in-cell immunofluorescence staining (lower). C) Stable NOD1 and NOD2 expression in the cultured Siha, CasKi and C33a cell lines were confirmed by green fluorescence (GFP flag), qPCR and western blotting.

Additional file 3. NOD1 and NOD2 enhanced the tumorigenic and metastatic abilities of CSCC cells. A) The percentages of wound healing, while data on C33a wound closure was normalized using the wound length at 0 h (left, 24 h and 48 h). The image on the right shows the percentage of wound closure of the Siha and CasKi cells, which were normalized to the wound length at 0 h (48 h). B) The weights of mice injected with different cell lines. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Additional file 4. Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells transfected by siRNA. The expression of NOD1 mRNA (A, data were from three independent experiments with three replicates) and protein (B, the picture is a representative from two independent experiments). SiRNA was presented as Si1, Si2 and Si3.

Additional file 5. Over-expression of NOD1 or NOD2 of Siha cells promotes FN1 and IL-8. A) Representative results of adhesion and invasion molecules with over-expression of NOD1/NOD2. (Siha cells, two independent experiments using triplicated wells). B) Transwell assays revealed that the migration and invasion abilities of the Siha/LV-NOD1 and Siha/LV-NOD2 cells were inhibited by knock down FN1. C) Reparixin downregulates FN1 mRNA expression.

Data Availability Statement

The NOD1 and NOD2 expression data of CSCC patients was extracted from the Human Protein Atlas (http://www.proteinatlas.org), and the mRNA expression and survival data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) databases. The target genes were functionally annotated by Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway analyses, and the significant biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions were identified.

The primary experiment data and material can be obtained from the correspondence with reasonable require.