Abstract

Objectives

Using longitudinal data from Southern Switzerland we assessed ten-month temporal trajectories of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress among adults after the first pandemic wave and explored differences between sociodemographic and health status groups.

Study design

This was a population-based prospective cohort study.

Methods

Participants were 732 (60% women) adults aged 20–64 years who completed the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale on a monthly base since August 2020 until May 2021, as part of the Corona Immunitas Ticino study based on a probability sample of non-institutionalized residents in Ticino, Southern Switzerland.

Results

Prevalence of moderate to severe depression increased from 7.5% in August 2020 to 12.5% in May 2021, anxiety increased from 4.8% to 8.1% and stress increased from 5.5% to 8.8%. A steeper increase in poor mental health was observed between October 2020 and February 2021. Men had a lower risk for anxiety (odds ratio [OR] = 0.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.36–0.95) and stress (OR = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.44–0.95) than women. Suffering from a chronic disease increased the risk for depression (OR = 1.82, 95% CI = 1.12–2.96), anxiety (OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.44–3.92) and stress (OR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.14–3.08). The differences between these groups did not vary over time.

Conclusions

In a representative Swiss adult sample, prevalence of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress almost doubled in the course of ten months following the end of the first pandemic wave in spring 2020. Women and participants with pre-existing chronic conditions were at a higher risk of poor mental health.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mental distress, Longitudinal studies

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of psychological distress and mental disorders in the general population has increased.1, 2, 3 Lockdown measures, prolonged financial hardship and exposure to and fear of potential infection are some of the contingent factors that continue to have detrimental effects on mental health.4, 5, 6 However, changes in psychological distress levels may differ across different population groups and contexts.2 , 7

The World Happiness Report8 outlines four phases to describe both short- and long-term negative impacts on mental health through the pandemic waves. The first two phases are mainly related to the introduction of lockdown measures and the broader socio-economic difficulties that followed. The subsequent phase entails the potential increase in demand for mental health services and the interplay between health and social services disruptions and exceeded capacity during and between the waves of the pandemic outbreaks. Finally, the population's mental health was and still is affected by the sustained exposure to socio-economic constraints, including abrupt changes to employment status, working conditions, income, schooling and social interactions, and the exacerbation of social inequalities. While the pandemic endures and with uncertainties about whether and when it will be over, empirical data of psychological distress and mental health changes over time and context-specific information are crucial to inform policy decision-making and guide community-level interventions.9 However, epidemiological evidence from longitudinal population-based studies on trajectories and potential increases in psychological distress, depressive and anxiety symptoms in representative samples of the general population is generally sparse and lacking also from regions that have been markedly impacted during the first and second pandemic waves, including Southern Switzerland.

Population-based longitudinal studies in China,10 , 11 the UK,12, 13, 14, 15 the Netherlands,16 Spain,17 , 18 Italy19 , 20 and France21 found high levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety and psychological distress among adults, in the months immediately after the first pandemic wave. Most studies focused simultaneously on multiple mental health symptoms, in particular depression and anxiety.11 , 13 , 17 , 18 , 20 Measures of stress-related symptoms10 , 16 , 19 and of overall measures of non-specific mental distress were less commonly ascertained.12 , 14 Moreover, the majority of previous longitudinal studies relied on up to two or three data collection points.22 , 23 Nevertheless, evidence of temporal variations and longitudinal patterns of mental health is limited,24, 25, 26, 27 particularly for the period during and after the second pandemic wave, when COVID-19 containment and mitigation control measures and restrictions endured and further contributed to the disruption of social life and caused far-reaching economic hardship.

The aim of this study was to assess ten-month repeated prevalence of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress among adults aged 20–64 years following the first pandemic wave in the Canton of Ticino (Switzerland), a region severely hit by the COVID-19 pandemic,28 and to explore differences between sociodemographic and health status groups.

Methods

Study design and participants

We used data from the Corona Immunitas Ticino study in Southern Switzerland. Full details about sampling, recruitment and data collection procedures have been previously described.29 Briefly, the Corona Immunitas Ticino study is a population-based, prospective cohort study purposely designed and conducted to assess the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic and its associated impact, including that on mental health, in Southern Switzerland. Participants are being followed up for repeated serological testing, self-reported symptoms and assessments, including mental and physical health, psychological well-being, risk of infection, adherence to infection prevention measures and lifestyle changes over time. The current study focused on adult participants (aged 20 to 64 years) who completed a baseline questionnaire in July 2020 providing sociodemographic and general health status information and who were prospectively followed up using repeated weekly and monthly digital assessments, since study inception. In July 2020, after the first wave of the epidemic, we sent invitation letters to 4000 adults aged 20 to 64 years living in Ticino drawn by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office to recruit a representative actual sample of the population in terms of age and gender distributions. During this phase, we recruited 1009 individuals (27% of those invited), who successfully completed the baseline assessments. In August 2020, 873 among these completed the first of 10 monthly follow-up assessments. All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Measurements and procedures

We collected data using secured online questionnaires implemented in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software,30 hosted at the Università della Svizzera Italiana. Sociodemographic and health status data included age, categorized into two age groups: (0) 20–49 and (1) 50–64 years; gender: (0) women, (1) men; education: (0) up to higher secondary/apprenticeship, (1) higher tertiary; obesity (0) as body mass index (BMI) < 30 kg/m2, (1) BMI ≥30 kg/m2; smoking status (0) non-smoker/former smoker, (1) current smoker (daily or occasional); and existing chronic conditions (“Do you suffer from any of the following chronic conditions?”): (0) none, (1) any among hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, immunological deficiency syndromes or respiratory syndromes.

We used the 21-item Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) to assess self-reported depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress levels at each monthly follow-up.31 Each DASS-21 item is rated on a 4-level Likert scale, from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always). The DASS-21 was used in previous research on psychological distress associated with SARS32 and COVID-19.33 Each of the three DASS-21 scales contains 7 items, divided into subscales with similar content. Subscales' scores range from 0 to 21. We used standard cut-offs for moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms (≥7), anxiety (≥5) and stress (>9) and computed a dichotomized score based on whether participants met or not case criteria for every DASS-21 dimension of distress. The DASS-21 showed good convergent, discriminant and nomological validity in normal samples34 , 35 and good reliability between repeated assessments. Here, Cronbach's α ranged from 0.89 to 0.93 for depression, from 0.76 to 0.86 for anxiety and from 0.89 to 0.93 for stress across assessments.

Statistical analysis

We checked data quality (i.e., straight line scoring) and analyzed missing data patterns. We excluded responses due to straight line scoring on the DASS-21 items (<0.4% across assessments) and participants with DASS-21 missing values on more than 3 monthly assessments of 10 (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material; n = 141, 16.5%) and derived an analytic sample of 732. Next, we imputed missing values of repeated measures of depression, anxiety and stress (<11.3% across assessments) as a linear combination of available observations. We observed no significant differences in baseline mental health scores between participants excluded and included in the analytic sample. Missing values on education (n = 10, 1.4%), living alone (n = 4, 0.6%), obesity (n = 9, 1.2%) and chronic diseases (n = 2, 0.3%) were imputed as a function of age and gender. We then modelled moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress as binary dependent variables in separate generalized estimation equation (GEE) models36 , 37 to assess variance structure and clustering error within subjects. GEE models allow the determination of how the average of a subject's response changes with covariates while specifying variance structure for the correlation between repeated measurements in the same subject over time. To select the best-working covariance structure for the current data, we followed a model selection method described by Pan38 and Cui:39 smaller quasi-likelihood under the quasi-information criterion (QIC) values was indicative of better fit. We assessed three types of covariance structure:40 exchangeable, assuming responses from the same cluster are equally correlated; autoregressive, where correlations between responses decrease across time; and unstructured, considering the correlations between responses to be comparatively complex. We tested GEE univariate models with robust standard errors adjusted for age and gender. We then adjusted also for education, living alone, obesity, smoking and chronic diseases in multivariate models. We further tested significant between-subject effects in interaction with time and plotted results to ease interpretation. Statistical significance was considered for P < 0.05 for direct effects and P < 0.1 for interaction effects. We used Stata version 15, for all statistical analyses (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Table 1 reports characteristics of the analytic sample. The analytic sample representativeness was fairly good. Age distributions by sex did not significantly differ between the study sample and the cantonal population demographics in 2019 although participation rate among those aged 20 to 30 years was smaller for both genders (Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample at baseline, Corona Immunitas Ticino.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| N | 732 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 46.84 (11.24) |

| Age group, years | |

| 20–49 | 383 (52.3) |

| 50–64 | 349 (47.7) |

| Woman | 431 (59.9) |

| Educational level | |

| Up to higher secondary | 479 (65.4) |

| Tertiary | 253 (34.6) |

| Living alone | 113 (15.4) |

| Obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 87 (11.9) |

| Smoking | 164 (22.4) |

| Chronic diseases | 134 (18.3) |

Note. Chronic diseases include hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, immunological deficiency syndromes or respiratory syndromes.

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

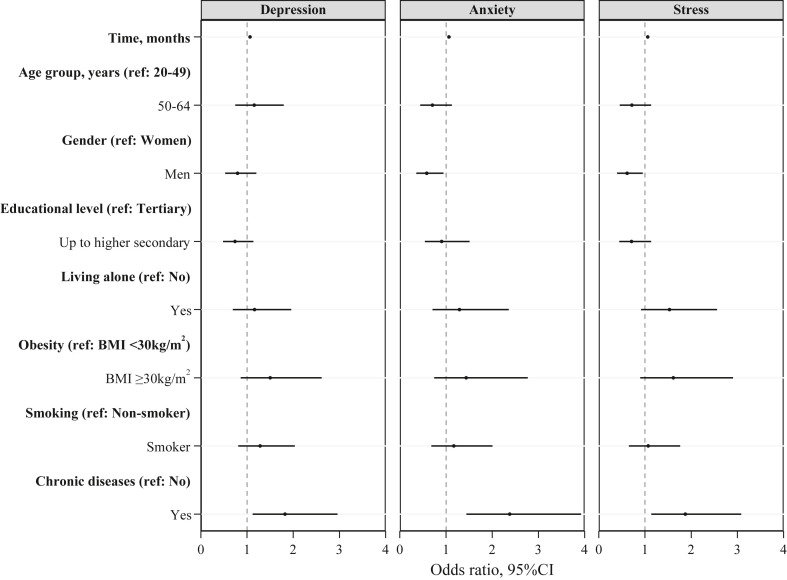

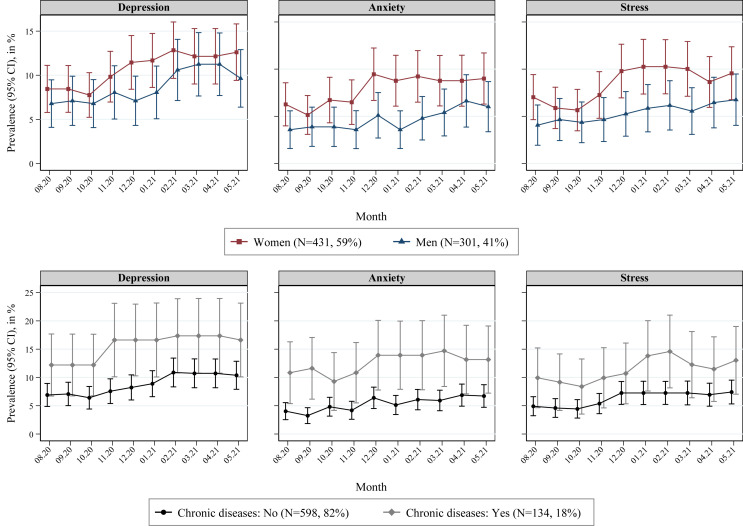

Fig. 1 presents GEE regression results with an exchangeable variance-covariance structure, which fitted the data better than an autoregressive or unstructured solution (see Table S1). The likelihood of depression (χ 2 = 31.89, P < 0.001), anxiety (χ 2 = 22.60, P = 0.007) and stress (χ 2 = 20.24, P = 0.017) significantly increased over time: on average, every month participants experienced a 6% increase in the odds of falling into the moderate to severe classification for depression, anxiety and stress. Men had a lower risk for anxiety (odds ratio [OR] = 0.58, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 0.36, 0.95, P = 0.029) and stress (OR = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.44, 0.95, P = 0.029) than women. In addition, suffering from a chronic disease also increased the risk for depression (OR = 1.82, 95% CI = 1.12, 2.96, P = 0.015), anxiety (OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.44, 3.92, P = 0.001) and stress (OR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.14, 3.08, P = 0.014) (Table S2). Fig. 2 shows 10-month longitudinal adjusted prevalence of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress, by gender and chronic diseases status. Overall, prevalence of moderate to severe depression increased from 7.5% (95% CI = 5.8%–9.1%) in August 2020 to 12.5% (95% CI = 10.1%–14.8%) in May 2021; moderate to severe anxiety increased from 4.8% (95% CI = 3.6%–6.1%) to 8.1% (95% CI = 6.3%–9.9%) and moderate to severe stress increased from 5.5% (95% CI = 4.2%–6.7%) to 8.8% (95% CI = 6.9%–10.8%). We found no significant interactions of gender or chronic diseases with time (expressed as continuous). While overall the differences observed at baseline remained stable over time, men and participants affected by at least one chronic disease had a higher prevalence of mental distress than women and participants with no chronic diseases, respectively. Increases in poor mental health were steeper in winter, between October 2020 and February 2021, than the monthly increases in summer 2020 and spring 2021, in particular for moderate to severe depression and stress levels.

Fig. 1.

Results of generalized estimating equation models explaining 10-month longitudinal prevalence of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress, Corona Immunitas Ticino (N = 732). Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are from generalized estimating equation models with robust standard errors adjusted for all listed covariates. Chronic diseases include hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, immunological deficiency syndromes or respiratory syndromes. BMI, body mass index.

Fig. 2.

Ten-month longitudinal adjusted prevalence of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress, by gender and chronic diseases status, Corona Immunitas Ticino. Prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are from generalized estimating equation models with robust standard errors adjusted for time (months), age, gender, education and living.

Results were unchanged in the set of sensitivity analysis of same GEE models ran in the restricted sample of participants without applying missing data imputations (N = 708), compared to the main results obtained in the larger analytic sample with missing data imputations (N = 732) Table S3.

Discussion

In a representative sample of adults living in Ticino, Southern Switzerland, we found that prevalence of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress almost doubled over ten months starting after the first COVID-19 pandemic wave in summer 2020. Moreover, psychological distress was consistently higher in women than in men and was associated with ill-health due to pre-existing chronic diseases. The pandemic is exacting a remarkable toll on the psychological well-being of the population. As the pandemic continues to unfold, our study highlights the importance of monitoring mental health in populations over time.

Our results are in line with those of studies on the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in specific subgroups of the population conducted in other Swiss regions and cantons, including in healthcare workers,41 in young adults42 and among hospital or clinic patients.43 Moreover, our observations on the longitudinal trends in depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms among adults in Ticino do not differ from those reported in other studies conducted around the end of the first pandemic wave in late spring/early summer 2020. For example, Fancourt et al.24 reported that depression and anxiety levels declined during summer 2020 among adults in the UK, following the end of the early lockdown restrictions. Similar results have been reported by Bendau et al.44 in Germany. However, camparisons with previous studies are not straightforward due to differences in data collection periods and varying national pandemic conditions.45 , 46

The DASS-21 self-reported questionnaires have been used in several population-based studies, in China,33 , 47 Iran,48 Spain,49 Austria50 and Italy51 , 52 and in large cross-national studies.53 , 54 Overall, the DASS-21 subscales’ scores reported in previous studies were generally higher than both the baseline and follow-up levels of psychological distress recorded over time in our sample. Whether this reflects prepandemic differences is not clear, and comparisons with previous studies is not straightforward also because epidemiological data based on the DASS-21 obtained from representative samples of the Swiss population are lacking. Nonetheless, our results are consistent with prepandemic levels in Switzerland of clinically significant depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms.55, 56, 57

We also found that women and participants suffering from pre-existing chronic conditions had higher DASS-21 scores of depression, anxiety and stress than men and healthy individuals, respectively. This is consistent with prepandemic research,58 , 59 and with some2 , 60 , 61 but not all research studies conducted during the pandemic period.1 , 3 Women may be more exposed to the risk of poor mental health because they may carry a heavier load in childcare provision than men,62 , 63 which was highly affected by schools and childcare closures and home-based working during the lockdown and quarantine periods.64 Our results confirm that COVID-19 had a disproportional impact on specific high-risk subgroups of the population including also individuals living with chronic diseases who may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of the pandemic on their physical and mental health because of poorer or reduced healthcare and treatment and higher perceived fear and uncertainty for their health in the event of a SARS-CoV-2 infection.61 , 65 , 66 The impellent needed to increase capacity for patients with COVID-19 imposed a massive and abrupt reorganization of health system and services. Health services have been and, to some extent, still are discontinued, and their access, use and navigation have been greatly impacted.

Our findings are novel because we depicted psychological distress trajectories in a large and representative sample of the population using highly frequent repeated assessments and could monitor changes in psychological distress over time. For example, we found steeper increases of depressive symptoms and stress between October 2020 and February 2021. This period corresponds to the outbreak of the second wave of the pandemic in Europe, which lead to the tightening of previously partially relapsed restrictions to contain the pandemic. Our findings support the hypothesis that the timing and duration of restrictive measures likely play a relevant modulating effect on the mental health of the population.51

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study has several strengths. First, this is the largest study carried out in Southern Switzerland in a representative sample from the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic period, with participants taking part in longitudinal follow-ups for a total of twelve months. Our study has strong external validity. In addition, we used validated and reliable assessment instruments to investigate several domains of mental health, which supports internal validity too. We conducted our analysis using ten monthly follow-up assessments, which allowed us to investigate the temporal variations and longitudinal patterns of mental health during an extended period of time through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some limitations of our study must be noted. First, the baseline assessment started in August 2020; we lack data during the first lockdown period in spring 2020. However, our data suggest little differences in psychological distress during and right after the second lockdown in winter 2020–2021, which may reasonably apply also to the first wave of the pandemic that we did not capture entirely. Second, common to most studies in psychiatric epidemiology, we cannot exclude, nor can we appraise, the extent of selection bias. Participation and retention may be lower in people with more severe depressive symptoms than in those without mood-related symptoms because of lack of interest, anxiety and fatigue, all of which may impact willingness and, to same extent, ability to participate in longitudinal studies with highly intense, repeated, self-reported assessments. Our results may be an underestimate of the true prevalence of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress in the target population. Nonetheless, the opposite may be also possible because healthy people may have been busier and less interested in participating in a mental health survey, which they might have perceived as non-pertinent to them. Finally, the sample size did not allow us to investigate further socio-economic and demographic differences in mental health with appropriate precision. This will be possible pooling data collected in the different study sites of the national Corona Immunitas collaborative initiative.29

Conclusions

This study showed that in a representative adult sample from a region in Switzerland that was severely hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, prevalence of moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress almost doubled over ten months following the end of the first pandemic wave. However, despite this trend, psychological distress may not be worse than prepandemic and may in fact be less marked than in neighbouring countries in Europe. Women were at a higher risk of poor mental health, in addition to participants with pre-existing chronic conditions. These results have important implications for the adoption of future public health interventions to tackle the burden of mental disorders and to sensitize the general population and high-risk groups to the detrimental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health.

Author statements

Acknowledgements

This work was published on behalf of the following members of the Corona Immunitas Ticino Working Group: [Emiliano Albanese, Rebecca Amati, Antonio Amendola, Anna Maria Annoni, Granit Baqaj, Kleona Bezani, Peter Buttaroni, Anne Linda Camerini, AnnaPaola Caminada, Laurie Corna, Cristina Corti, Luca Crivelli, Daniela Dordoni, Marta Fadda, Luca Faillace, Ilaria Falvo, Maddalena Fiordelli, Carolina Foglia, Giovanni Franscella, Roberta Gandolfi, Sara Levati, Isabella Martinelli, Rosalba Morese, Anna Papis, Giovanni Piumatti, Greta Rizzi, Diana Sofia Da Costa Santos, Mauro Tonolla, Gladys Delai Venturelli]. We are grateful to all the participants, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Ethical approval

The Corona Immunitas Ticino study was approved by the Ethics Committees of all the Swiss Cantons members of the projects (BASEC 2020-01247/BASEC 2020-01514).

Funding

The Corona Immunitas Ticino study was funded by the Swiss School of Public Health through the national research program Corona Immunitas, which is a public-private partnership supported by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, various cantons and private funders, and in part by Ceresio Foundation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.02.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cénat J.M., Blais-Rochette C., Kokou-Kpolou C.K., Noorishad P.-G., Mukunzi J.N., McIntee S.-E., et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr Res. 2020:113599. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu T., Jia X., Shi H., Niu J., Yin X., Xie J., et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;281:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pieh C., Budimir S., Delgadillo J., Barkham M., Fontaine J.R., Probst T. Mental health during COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom. Psychosom Med. 2021;83:328–337. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson J.M., Lee J., Fitzgerald H.N., Oosterhoff B., Sevi B., Shook N.J. Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62:686–691. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzpatrick K.M., Harris C., Drawve G. Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020;12(S1):S17–S21. doi: 10.1037/tra0000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benzeval M., Burton J., Crossley T.F., Fisher P., Jäckle A., Low H., et al. 2020. The idiosyncratic impact of an aggregate shock: the distributional consequences of COVID-19. Available at: SSRN 3615691. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banks J., Fancourt D., Xu X. 2021. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic; pp. 107–130. World Happiness Report 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aknin L., De Neve J., Dunn E., Fancourt D., Goldberg E., Helliwell J., et al. Mental health during the First Year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a review and recommendations for moving forward. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1177/17456916211029964. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., McIntyre R.S., et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao Y., Fan B., Zhang H., Guo L., Lee Y., Wang W., et al. The impact of COVID-19 on subthreshold depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30 doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T., Hatch S., Hotopf M., John A., et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwong A.S., Pearson R.M., Adams M.J., Northstone K., Tilling K., Smith D., et al. Mental health before and during COVID-19 in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. Br J Psychiatr. 2020:1–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daly M., Sutin A.R., Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connor R.C., Wetherall K., Cleare S., McClelland H., Melson A.J., Niedzwiedz C.L., et al. Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Br J Psychiatr. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan K.-Y., Kok A.A., Eikelenboom M., Horsfall M., Jörg F., Luteijn R.A., et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: a longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatr. 2021;8:121–129. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30491-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González-Sanguino C., Ausín B., Castellanos M., Saiz J., Muñoz M. Mental health consequences of the Covid-19 outbreak in Spain. A longitudinal study of the alarm situation and return to the new normality. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. 2021;107:110219. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cecchini J.A., Carriedo A., Fernández-Río J., Méndez-Giménez A., González C., Sánchez-Martínez B., et al. A longitudinal study on depressive symptoms and physical activity during the Spanish lockdown. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21:100200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castellini G., Rossi E., Cassioli E., Sanfilippo G., Innocenti M., Gironi V., et al. A longitudinal observation of general psychopathology before the COVID-19 outbreak and during lockdown in Italy. J Psychosom Res. 2021;141:110328. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salfi F., Lauriola M., Amicucci G., Corigliano D., Viselli L., Tempesta D., et al. Gender-related time course of sleep disturbances and psychological symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown: a longitudinal study on the Italian population. Neurobiol. Stress. 2020;13:100259. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramiz L., Contrand B., Castro M.Y.R., Dupuy M., Lu L., Sztal-Kutas C., et al. A longitudinal study of mental health before and during COVID-19 lockdown in the French population. Glob Health. 2021;17:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00682-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prati G., Mancini A. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: a review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol Med. 2021;51:201–211. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter D., Riedel-Heller S., Zuercher S. Mental health problems in the general population during and after the first lockdown phase due to the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic: rapid review of multi-wave studies. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatr. 2021;8:141–149. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce M., McManus S., Hope H., Hotopf M., Ford T., Hatch S.L., et al. Mental health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: a latent class trajectory analysis using longitudinal UK data. Lancet Psychiatr. 2021;8(7):610–619. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00151-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riehm K.E., Brenneke S.G., Adams L.B., Gilan D., Lieb K., Kunzler A.M., et al. Association between psychological resilience and changes in mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fluharty M., Bu F., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Coping strategies and mental health trajectories during the first 21 weeks of COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom. Soc Sci Med. 2021;279:113958. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.COVID-19 information for Switzerland, corondata dashboard. 2020. http://www.corona-data.ch/ [25 September 2020]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 29.West E.A., Anker D., Amati R., Richard A., Wisniak A., Butty A., et al. Corona Immunitas: study protocol of a nationwide program of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and seroepidemiologic studies in Switzerland. Int J Publ Health. 2020;65:1529–1548. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01494-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovibond S.H., Lovibond P.F. Psychology Foundation of Australia; Sidney: 1996. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAlonan G.M., Lee A.M., Cheung V., Cheung C., Tsang K.W., Sham P.C., et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatr. 2007;52:241–247. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee D. The convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) J Affect Disord. 2019;259:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henry J.D., Crawford J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang K.-Y., Zeger S.L. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziegler A., Vens M. Generalized estimating equations. Methods Inf Med. 2010;49:421–425. doi: 10.3414/ME10-01-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan W. Akaike's information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui J. QIC program and model selection in GEE analyses. Stata J. 2007;7:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grady J.J., Helms R.W. Model selection techniques for the covariance matrix for incomplete longitudinal data. Stat Med. 1995;14:1397–1416. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krammer S., Augstburger R., Haeck M., Maercker A. Adjustment disorder, depression, stress symptoms, Corona related anxieties and coping strategies during the Corona pandemic (COVID-19) in Swiss medical staff. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2020;70:272–282. doi: 10.1055/a-1192-6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marmet S., Wicki M., Gmel G., Gachoud C., Daeppen J.-B., Bertholet N., et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 crisis on young Swiss men participating in a cohort study. PsyArXiv. 2020 doi: 10.4414/smw.2021.w30028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck K., Vincent A., Becker C., Keller A., Cam H., Schaefert R., et al. Prevalence and factors associated with psychological burden in COVID-19 patients and their relatives: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bendau A., Kunas S.L., Wyka S., Petzold M.B., Plag J., Asselmann E., et al. Longitudinal changes of anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: the role of pre-existing anxiety, depressive, and other mental disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2021;79:102377. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hajek A., Sabat I., Neumann-Böhme S., Schreyögg J., Barros P.P., Stargardt T., et al. Prevalence and determinants of probable depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in seven countries: longitudinal evidence from the European COVID Survey (ECOS) J Affect Disord. 2021;299:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson E., Sutin A.R., Daly M., Jones A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du J., Mayer G., Hummel S., Oetjen N., Gronewold N., Zafar A., et al. Mental health burden in different professions during the final stage of the COVID-19 lockdown in China: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/24240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102076. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Odriozola-González P., Planchuelo-Gómez Á., Irurtia M.J., de Luis-García R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatr Res. 2020;290:113108. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Traunmüller C., Stefitz R., Gaisbachgrabner K., Schwerdtfeger A. Psychological correlates of COVID-19 pandemic in the Austrian population. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09489-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fiorillo A., Sampogna G., Giallonardo V., Del Vecchio V., Luciano M., Albert U., et al. Effects of the lockdown on the mental health of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: results from the COMET collaborative network. Eur Psychiatr. 2020;63 doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mazza C., Ricci E., Biondi S., Colasanti M., Ferracuti S., Napoli C., et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alzueta E., Perrin P., Baker F.C., Caffarra S., Ramos-Usuga D., Yuksel D., et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: a study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. J Clin Psychol. 2021;77:556–570. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shah S.M.A., Mohammad D., Qureshi M.F.H., Abbas M.Z., Aleem S. Prevalence, Psychological Responses and associated correlates of depression, anxiety and stress in a global population, during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57:101–110. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00728-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dupuis M., Strippoli M.P.F., Gholam-Rezaee M., Preisig M., Vandeleur C.L. Mental disorders, attrition at follow-up, and questionnaire non-completion in epidemiologic research. Illustrations from the CoLaus| PsyCoLaus study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28 doi: 10.1002/mpr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) Swiss Federal Statistical Office FSO, Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA; Neuchâtel: 2013. Swiss health survey. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) Swiss Federal Statistical Office FSO, Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA; Neuchâtel: 2020. Health - pocket statistics 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salk R.H., Hyde J.S., Abramson L.Y. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143:783. doi: 10.1037/bul0000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Labaka A., Goñi-Balentziaga O., Lebeña A., Pérez-Tejada J. Biological sex differences in depression: a systematic review. Biol Res Nurs. 2018;20:383–392. doi: 10.1177/1099800418776082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Louvardi M., Pelekasis P., Chrousos G.P., Darviri C. Mental health in chronic disease patients during the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18:394–399. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M., Gill H., Phan L., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Makarova E., Herzog W. Springer; 2015. Gender roles within the family: a study across three language regions of Switzerland. Psychology of Gender through the Lens of Culture; pp. 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Girardin N., Bühlmann F., Hanappi D., Le Goff J.-M., Valarino I. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2016. The transition to parenthood in Switzerland: between institutional constraints and gender ideologies. Couples' Transitions to Parenthood. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zamarro G., Prados M.J. Gender differences in couples' division of childcare, work and mental health during COVID-19. Rev Econ Househ. 2021;19:11–40. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09534-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saqib M.A.N., Siddiqui S., Qasim M., Jamil M.A., Rafique I., Awan U.A., et al. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on patients with chronic diseases. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:1621–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chudasama Y.V., Gillies C.L., Zaccardi F., Coles B., Davies M.J., Seidu S., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: a global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:965–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.