Abstract

Background:

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), low socioeconomic status (SES), and harsh parenting practices each represent well-established risk factors for mental health problems. However, research supporting these links has often focused on only one of these predictors and psychopathology, and interactions among these variables in association with symptoms are not well understood.

Objective:

The current study utilized a cross-sectional, multi-informant, and multi-method design to investigate the associations of ACEs, SES, parenting, and concurrent internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescents.

Participants and Setting:

Data are from a volunteer sample of 97 adolescents and their caregivers recruited from 2018 to 2021 in a southern U.S. metropolitan area to sample a range of exposure to ACEs.

Methods:

Multiple linear regression models were used to assess associations among adolescents’ ACEs exposure, SES, observed parenting practices, and symptoms of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology.

Results:

Lower SES was associated with higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, while higher ACEs exposure and observed parenting were related to externalizing but not internalizing symptoms. Associations of adolescents’ exposure to physical abuse and perceived financial insecurity with externalizing symptoms were moderated by warm and supportive parenting behaviors. Conversely, harsh parenting was linked to increased levels of externalizing symptoms, particularly in the context of low income.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that the presence of multiple risk factors may incur greater vulnerability to externalizing problems, while warm and supportive parenting practices may provide a buffer against externalizing problems for adolescents exposed to physical abuse. Links between ACEs, SES, parenting, and youth adjustment should continue to be explored, highlighting parenting as a potentially important and malleable intervention target.

Keywords: Adverse Childhood Experiences, Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, Adolescence, Psychopathology, Internalizing, Externalizing

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is pervasive in the lives of children and adolescents (Dube et al., 2001). ACEs include child maltreatment (i.e., physical and emotional neglect; physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) and a broader array of experiences associated with family circumstances (i.e., witnessing adult domestic violence, parental mental illness, or substance abuse) (Felitti et al., 1998; Walsh et al., 2019). ACEs are associated with a range of psychopathology (e.g., anxiety, depression, suicide risk, disruptive behavior disorders), and substance abuse (Hughes et al., 2017; Kalmakis & Chandler, 2015; Scully et al., 2020). Further, research has demonstrated that the negative effects of ACEs emerge during childhood and adolescence (Scully et al., 2020), which in turn predicts a more severe course of symptoms.

The current study focuses on ACEs related to maltreatment. It is guided by the multiple individual risk approach (LaNoue et al., 2020), which emphasizes the discrete examination of ACEs and outcomes, to clarify the impact of exposure to specific domains of ACEs in the presence or absence of other ACEs. This approach, in which ACEs (e.g., physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect) are treated as separate predictors aggregated in a single model, allows for an examination of the impact of distinct ACEs, especially when those adversities do not occur in isolation (LaNoue et al., 2020). For example, Henry et al. (2021) found that entering multiple ACEs simultaneously into a single model accounted for significant portions of the variance in both internalizing and externalizing symptoms in a large sample of children and adolescents in state custody.

While direct associations between ACEs and symptoms of psychopathology have been found, a range of psychosocial, environmental, and interpersonal processes have been examined as possible moderators of these direct associations. In particular, socioeconomic status (SES) is an important contextual factor that has been linked with exposure to ACEs (Walsh et al., 2019). In the current study, SES is conceptualized as a family’s access to both economic resources (e.g., financial and material) and human resources (e.g., non-material resources such as education; Peverill et al., 2020). As family SES is difficult to fully capture with a single index or an average of disparate indices, using different measures of SES may offer unique strengths in the examination of socioeconomic standing (Peverill et al., 2020). For instance, family income is a commonly utilized index of SES that presents a proxy for material hardship, and parental education affords a measure of SES that is arguably more stable than other facets of SES (Diemer et al., 2013). Further, subjective measures of SES may be more strongly associated with health outcomes than objective SES measures (Quon & McGrath, 2014). Given their relative advantages, using both objective (i.e., family income, parental education) and subjective measures (i.e., perceived financial insecurity) of SES is an important aim. Based on Corman et al. (2012), we define perceived financial insecurity as the perception of one’s inability to meet financial demands (i.e., pay bills, purchase sufficient food and clothing).

Despite the potential importance of understanding the effects of ACEs in the context of SES, relatively little research has examined SES as a moderator of the association between ACEs and symptoms of psychopathology in youth. Prior work has shown that SES moderates the association between ACEs exposure and other health-related outcomes (e.g., Currie et al., 2021; Sundel et al., 2018). Also, children from lower-SES families tend to have higher levels of psychopathology, including internalizing and externalizing symptoms, relative to peers from families with greater resources (Bøe et al., 2014; Peverill et al., 2020). The increased risk associated with lower SES may be exacerbated by a variety of factors, including greater exposure to ACEs and differences in family processes and functioning (Grant et al., 2003; Peverill et al., 2020). Further, it is possible that the association between ACEs and psychopathology is stronger in families from low-SES backgrounds due to reduced access to mental health resources.

Parenting quality is also associated with adjustment in youth, especially in the context of ACEs and SES (Bøe et al., 2014; Uddin et al., 2020). Harsh and inconsistent parenting practices are associated with hostility, aggressiveness, oppositional behavior, anxiety, and depression in youth (Bøe et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2012; Yap et al., 2014; 2015). In contrast, warm and structured parenting practices and interactions are associated with positive adolescent mental health (Clayborne et al., 2021; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2013). In a sample of children with varying exposure to ACEs, Yamaoka and Bard (2019) found that positive parenting practices were associated with fewer negative effects of ACEs. The authors posit that positive parenting practices protect children from adversity and promote development that reinforces resiliency. Evidence also suggests that socioeconomically disadvantaged parents may be more likely to engage in parenting characterized by harsh discipline and low levels of warmth (Choi et al., 2018). Several studies demonstrate the impact of socioeconomic disadvantage on youth adjustment through the negative influence on parent psychological well-being and parenting (Choi et al., 2018; Devenish et al., 2017; Parke et al., 2004). When parents are unable to meet their family’s financial and emotional needs, there are well-established associations between parenting stress and youth behavior problems, delinquency, and antisocial behavior (Cherry et al., 2019; Jeon & Chun, 2017; Piotrowska et al., 2015; Reiss, 2013). Importantly, parenting is a malleable target for intervention and understanding the role of warm/supportive and harsh parenting behaviors in the context of ACEs and financial stress is a crucial clinical aim.

The current study builds upon existing research in several ways. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the interaction between ACEs and SES in association with adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Second, the current study examines the interaction between ACEs exposure and three distinct SES measures (i.e., gross annual income, parental educational attainment, and perceived financial insecurity) in association with youth internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Third, while research has examined the association between parents’ ACEs exposure and parenting behaviors (i.e., Steele et al., 2016), the current study investigates the interaction between parenting and youths’ ACEs exposure in association with youth’s symptoms. Last, to our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine three-way interactions among different facets of family SES, ACEs, and parenting in association with youth adjustment.

To address these issues, the current study utilized a multi-informant and multi-method design to investigate the associations of ACEs, SES, and parenting with youths’ internalizing and externalizing problems in early to mid-adolescence (ages 10 to 15 years old). First, we expected that lower SES (i.e., lower gross income, lower parental educational attainment, higher perceived financial insecurity), increased ACEs exposure, and higher levels of harsh parenting behaviors would be associated with higher internalizing and externalizing symptoms, while higher levels of warm/supportive parenting would be associated with fewer symptoms. Second, we tested SES as a moderator of the association between ACEs and symptoms (i.e., a two-way interaction between SES and ACEs predicting symptoms), such that for adolescents with lower SES, ACEs would be associated with higher symptoms. Third, we expected a two-way interaction between SES and parenting, where harsh parenting and lower SES would be associated with higher symptoms. Fourth, we tested parenting as a moderator of the association between ACEs and symptoms (i.e., a two-way interaction between ACEs and parenting), such that at higher levels of harsh parenting, ACEs would be associated with higher symptoms, while at higher levels of warm/supportive parenting, adolescents would have fewer symptoms regardless of ACEs exposure. Finally, an exploratory aim was to examine the three-way interaction among ACEs, SES, and parenting as a predictor of adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Method

Participants

Data for this cross-sectional multi-method study were drawn from a volunteer sample of 97 parent-adolescent dyads. Adolescents were between 10 and 15 years old (M = 12.21; SD = 1.68), and 52.6% were female. Adolescents identified as 72.2% White, 15.5% African American, 5.2% Asian, 5.0% Hispanic or Latino, and 2.1% Other. The majority of parents were female (89.6%) and married or living with a partner (71.1%). See Table 1 for sociodemographic sample characteristics and descriptive statistics for key study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Study Variables

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing Symptomsa | 54.72 | 10.01 | 32 | 81 |

| Externalizing Symptomsa | 51.15 | 9.71 | 29 | 76 |

| Physical Abuse | 5.99 | 2.26 | 5 | 22 |

| Sexual Abuse | 5.88 | 3.21 | 5 | 25 |

| Emotional Abuse | 8.72 | 3.85 | 5 | 25 |

| Physical Neglect | 6.31 | 2.40 | 5 | 19 |

| Emotional Neglect | 7.28 | 2.67 | 5 | 15 |

| Perceived Financial Insecurity | 6.69 | 3.81 | 0 | 16 |

| Parental Education | 4.60 | 1.29 | 2 | 6 |

| Gross Income ($) | 88,169 | 61,115 | 0 | 250,000 |

| Observed Warm/Supportive Parenting | 14.20 | 3.38 | 7 | 22 |

| Observed Harsh Parenting | 11.27 | 4.19 | 3 | 22 |

Values presented are T scores (M = 50; SD = 10).

Procedure

Adolescents and their parents were recruited in a southern U.S. metropolitan area to participate in a study about stress and emotions in families from 2018 to 2021. In efforts to enroll a sample with variation in ACEs exposure, participants were recruited from university listserv postings, outpatient clinics, and community sites. Parents who expressed interest in the study were screened on the phone by trained research assistants to determine eligibility. Exclusion criteria were (a) the parent was not the adolescent’s legal guardian, (b) adolescents outside the 10 to 15 years old range, (c) the dyad did not live together at least 50% of the time for the previous six months, (d) diagnosis of schizophrenia (past or present) in parents or adolescents, or (e) diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in the adolescent. Parents and adolescents completed a battery of questionnaires prior to an in-person laboratory visit. During the laboratory visit, parent-adolescent dyads completed additional questionnaires, interviews, and a videotaped discussion task in which dyads discussed a recent disagreement. Families were compensated for the assessment and the University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Measures

ACEs.

Youth’s exposure to ACEs was measured using the parent report version of the Child Trauma Questionnaire – Short Form (CTQ- SF; Bernstein et al., 2003), a 28-item screening measure that provides a brief assessment of a broad range of ACEs. Parents reported on their adolescents’ exposure to ACEs on five subscales: emotional, sexual, and physical abuse, and physical and emotional neglect. Responses are measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never true, 2 = rarely true, 3 = sometimes true, 4 = often true, 5 = very often true). For example, parents were asked to indicate the frequency of events in their child’s life from birth until the present such as, “My child didn’t have enough to eat,” and “My child got hit so hard by someone in the family that he/she had to see a doctor or go to the hospital.” The CTQ subscale scores have test-retest reliability coefficients from α = .76 to .86, and internal consistency coefficients from α = .66 to .92 across initial validation samples (Bernstein et al., 2003). In the current study, each subscale demonstrated acceptable to excellent internal consistency: α = .71 for physical neglect, α = .82 for emotional neglect, α = .82 for physical abuse, α = .76 for emotional abuse, and α = .96 for sexual abuse. The following values are suggested for interpreting the severity of ACEs exposure: emotional abuse (5–12 = none or low, 13–15 = moderate, 16 ≥ severe); physical abuse (5–9 = none or low, 10–12 = moderate, 13 ≥ severe); sexual abuse (5–7 = none or low, 8–12 = moderate, 13 ≥ severe); emotional neglect (5–14 = none or low, 15–17 = moderate, 18 ≥ severe); physical neglect (5–9 = none or low, 10–12 = moderate, 13 ≥ severe; Bernstein et al., 2003). Across all five ACEs, a total score of 5 indicates no exposure to that particular ACE (i.e., a score of 5 on physical abuse denotes no exposure to physical abuse).

SES and perceived financial insecurity.

Parents completed a demographic questionnaire assessing their gross annual income, highest level of education completed (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school graduate, 3 = some college or technical school, 4 = college graduate, 5 = some graduate education, and 6 = graduate degree), and parent-perceived financial insecurity. To assess parent-perceived financial insecurity on a scale created for the current study, parents rated the degree to which they agreed with six statements on a 4-point scale (0 = strongly agree, 1 = agree, 2 = disagree, 3 = strongly disagree) and we created a composite score, calculated such that higher scores indicate more perceived financial insecurity. Examples of individual items comprising this composite include: “my family has enough money to afford the kind of home we need,” “we have enough money to afford the kind of food we need,” and “we have enough money to afford the kind of clothing we need.” Internal consistency for this perceived financial insecurity composite score in the present sample was good (α = .89).

Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms.

The Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used to assess youth’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms within the previous six months. The YSR is a 112-item self-report checklist of symptoms and behaviors on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very often or often true). The Internalizing and Externalizing Scales were used, including 31 items on depression, somatic complaints, and anxiety and 32 items on aggressive behaviors and rule-breaking. The reliability and validity of the YSR are well-established (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The internal consistency reliability for the Internalizing (α = .77) and Externalizing (α = .81) scales in the current sample were good (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). While the YSR is specified for 11- to 18-year-olds, applying the definition of adolescence as the second decade of life (Lerner & Steinberg, 2004), 18 youth in the current sample were 10 years old. Internal consistency was good for this subgroup (Internalizing α = .85, Externalizing α = .89).

Parenting Behaviors.

Observed warm/supportive and harsh parenting behaviors were coded from a 10-minute videotaped discussion task between parents and adolescents. Dyads completed an adapted version of the Issues Checklist (Robin & Foster, 1989) to guide their discussion task topic. The Issues Checklist requires respondents to report which of 44 topics they discussed with their parent or adolescent within the last four weeks (e.g., doing homework, talking back to caregivers), and rate how they felt during those discussions (1 = calm to 5 = angry). Trained research assistants chose one topic that was rated highly by both the parent and adolescent. Dyads were instructed to (a) describe the issue, (b) express how they feel about it, (c) explain why it has become a source of conflict, and (d) attempt to resolve the chosen issue.

The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001) is a macro-level system and was used to code parents’ verbal and nonverbal behaviors during the videotaped discussion task on a 9-point scale. When discerning the score for each individual behavior, the intensity, frequency, and contextual and affective nature of the behavior is considered. A score of one denotes the absence of a behavior, while a score of nine denotes the highest level of intensity and frequency of a behavior. The validity of IFIRS has been well-established in correlational analyses and confirmatory factor analysis (Alderfer et al., 2008; Melby & Conger, 2001).

The parent-adolescent discussion tasks were coded by a team of trained graduate and undergraduate student research assistants. All trained coders passed a written test of code definitions and examples (90% accuracy) and reached 80% reliability on previously coded videos. All videos were double coded; two trained research assistants independently coded all videos and then met to discuss and reach consensus. Per the IFIRS manual, when ratings differed by a single point, the higher score was utilized. Ratings that differed by two or more points were resolved through discussion. In the present study, an observed warm/supportive parenting composite was created by summing three parental codes (warmth/support, listener responsiveness, sensitive/child centered). An observed harsh parenting composite was created by summing three parental codes (hostility, intrusive, lecture/moralize). These composites were theoretically derived to represent attributes associated with warm/supportive and harsh parenting (Baumrind, 1971; Eisenberg et al., 2015). The internal consistency reliability for the observed warm/supportive (α = .83) and harsh (α = .72) parenting composites were good. Intraclass correlations (ICCs) for the individual codes within observed harsh parenting ranged from .80 to .86 (M = .82), and individual codes within observed warm/supportive parenting ranged from .81 to .88 (M = .85). Code definitions and examples are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Data Analytic Plan

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS (version 25). Preliminary analyses of means, standard deviations, ranges, and skewness for all variables were calculated. Two outliers that exceeded the 95th percentile of gross income in the sample were identified and winsorized (i.e., the original value was replaced by the nearest value of an observation that was unsuspected of being an outlier; Dixon, 1960). The majority of ACEs subscales were non-normal (i.e., skewness > 2; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Therefore, the bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap method was applied to linear regression analyses with non-normal data (Kelley, 2005). For the YSR, raw scores were used in analyses to maximize variance. Multiple linear regression was used to assess the main effects of ACEs, SES, and parenting in association with symptoms (Hypothesis 1). Next, separate multiple linear regression models were computed to predict adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms from ACEs (i.e., physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect), SES (i.e., parent-perceived financial insecurity, parental educational attainment, and gross income), and observed parenting behaviors (i.e., warm/supportive and harsh), including interactions between (1) ACEs and SES (Hypothesis 2), (2) SES and observed parenting (Hypothesis 3), and (3) ACEs and observed parenting (Hypothesis 4). Exploratory analyses were conducted to predict adolescents’ symptoms from the three-way interaction among ACEs x SES x observed parenting. Due to well-established associations among age, gender, and internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Bongers et al., 2004; Hankin et al., 2009; Mashi et al., 2008; Ohannessian et al., 2017; Salk et al., 2017), adolescents’ age and gender were controlled for in all models. In addition, for each model examining the impact of individual ACEs (e.g., physical abuse), exposure to other forms of ACEs were included in the model as covariates to control for co-occurrence of different types of ACEs in accordance with the multiple individual risk statistical approach for ACEs (LaNoue et al., 2020).

Missing Data.

Of the 97 dyads in the full sample, two dyads did not complete the discussion task that was coded for parenting behaviors, one dyad had missing data on the parental education variable, and eight dyads had missing data on the gross income variable. Little’s MCAR test showed that the data were missing completely at random (p = .37). Multiple imputation was used in all analyses using these variables to minimize potential bias (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Power Analyses.

Power analyses were conducted using G*Power 3.1 to determine detectable effect sizes for linear regression analyses (Erdfelder & Buchner, 1996). With α= .05 and power set to .80, we were able to detect small-to-medium effects and medium-to-large effects. Specifically, we were able to detect small-to-medium effects (f2= .12 or larger) when examining facets of SES and parenting (Hypothesis 1) and their interactions (f2= .14 or larger) in association with internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Hypothesis 3). We were able to detect medium-to-large effects (f2= .18 or larger) when examining interactions between ACEs and SES (Hypothesis 2), and ACEs and parenting (Hypothesis 4) in association with symptoms. We were able to detect medium-to-large effects when examining the main effects of ACEs in association with symptoms (f2= .16 or larger). Last, we were able to detect medium-to-large effects in our exploratory three-way interaction models (f2= .21 or larger).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays means and standard deviations for the key study variables prior to addressing missing data with multiple imputation. As such, data for n = 96 are presented for parental education, n = 95 for observed parenting scores, and n = 89 for gross income in Table 1. Notably, parents reported that 40.2% of youth in the sample had experienced physical neglect, 66% experienced emotional neglect, 14.4% experienced sexual abuse, 36.1% experienced physical abuse, and 83.5% experienced emotional abuse (i.e., endorsed greater than no exposure on the CTQ items). Adolescents’ internalizing symptoms were approximately half of a standard deviation above the normative mean (Mean T = 54.72), while externalizing symptoms approximated the normative mean (Mean T = 51.15). Regarding educational attainment, 76.1% of parents reported earning at least a college degree, 20.8% reported completing some college or technical schooling, and 3.1% had a high school degree or less. Annual household income in the sample ranged from less than $5,000 to over $100,000, with a median income of $72,000. Regarding perceived financial insecurity, on average, 14% of the sample indicated that they did not have enough money to afford costs of living (e.g., clothing, housing, food, medical care), and 63.9% of the sample reported at least some difficulty paying bills in the past 12 months.

Multiple Linear Regression Analyses

Hypothesis 1: Associations of Symptoms with SES, ACEs, and observed parenting.

To test the first hypothesis, separate models were conducted to examine associations among SES, ACEs, and observed parenting with adolescents’ internalizing symptoms (Table 2, Models 1–6, n = 97) and externalizing symptoms (Table 3, Models 1–6, n = 97). To test the main effects of socioeconomic status in association with internalizing and externalizing symptoms, separate models for each facet of SES were run controlling for adolescents’ age and gender. In support of Hypothesis 1, there was a main effect of income in association with internalizing symptoms (β = −.28, p = .004, f2 = .09) and externalizing symptoms (β = −.31, p = .002, f2 = .10). Parental education was also negatively associated with internalizing symptoms (β = −.26, p = .008, f2 = .07) externalizing symptoms (β = −.26, p = .01, f2 = .07), while perceived financial insecurity was positively associated with internalizing symptoms (β = .35, p < .001, f2 = .14) and externalizing symptoms (β = .24, p = .016, f2 = .06).

Table 2.

Linear Regression Analyses Predicting Adolescents’ Internalizing Symptoms from SES, ACEs, and Parenting

| β | t | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | F(3,93) = 5.83**; adjusted R2 = .13** | LL | UL | ||

| Age | .07 | .74 | −.61 | 1.34 | .46 |

| Gender | .30** | 3.13** | 1.83 | 8.15 | .002 |

| Income | −.28** | −2.96** | −.00 | −.00 | .004 |

| Model 2 | F(3,93) = 5.32**; adjusted R2 = .12** | ||||

| Age | .06 | .64 | −.67 | 1.30 | .52 |

| Gender | .29** | 3.03** | 1.66 | 8.02 | .003 |

| Parental Education | −.26** | −2.71** | −3.04 | −.47 | .008 |

| Model 3 | F(3,93) = 7.93***; adjusted R2 = .18*** | ||||

| Age | .06 | .63 | −.65 | 1.26 | .53 |

| Gender | .28** | 3.04** | 1.63 | 7.75 | .003 |

| Perceived Financial Insecurity | .35*** | 3.82*** | .39 | 1.22 | <.001 |

| Model 4 | F(7,89) = 3.00**; adjusted R2 = .12** | ||||

| Age | .00 | .03 | −1.08 | .86 | 0.98 |

| Gender | .24* | 2.39* | .61 | 7.19 | 0.02 |

| Emotional Abuse | .44* | 2.57* | .11 | 1.98 | 0.029 |

| Physical Abuse | −.32 | −1.93 | −2.53 | 2.45 | 0.07 |

| Sexual Abuse | −.10 | −.67 | −1.26 | .64 | 0.43 |

| Emotional Neglect | .01 | .04 | −.89 | .68 | 0.97 |

| Physical Neglect | .12 | .86 | −.61 | 1.45 | 0.34 |

| Model 5 | F(3,93) = 2.85*; adjusted R2 = .06* | ||||

| Age | .06 | .55 | −.75 | 1.31 | .59 |

| Gender | .28** | 2.79** | 1.34 | 7.94 | .006 |

| Observed Harsh Parenting | .07 | .72 | −.27 | .57 | .47 |

| Model 6 | F(3,93) = 3.55*; adjusted R2 = .07* | ||||

| Age | .04 | .43 | −.80 | 1.24 | .67 |

| Gender | .27** | 2.79** | 1.31 | 7.81 | .006 |

| Observed Warm/Supportive Parenting | −.16 | −1.57 | −.91 | .11 | .12 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Table 3.

Linear Regression Analyses Predicting Adolescents’ Externalizing Symptoms from SES, ACEs, and Parenting

| β | t | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | F(3,93) = 4.08**; adjusted R2 = .09** | LL | UL | ||

| Age | .07 | .71 | −.52 | 1.11 | .48 |

| Gender | .16 | 1.64 | −.47 | 4.83 | .11 |

| Income | −.31** | −1.92** | −.00 | −.00 | .002 |

| Model 2 | F(3,93) = 2.96*; adjusted R2 = .09* | ||||

| Age | .06 | .60 | −.58 | 1.08 | .55 |

| Gender | .15 | 1.50 | −.66 | 4.71 | .14 |

| Parental Education | −.26* | −2.60* | −2.50 | −.33 | .01 |

| Model 3 | F(3,93) = 2.69*; adjusted R2 = .05* | ||||

| Age | .06 | .58 | −.59 | 1.08 | .56 |

| Gender | .14 | 1.37 | −.83 | 4.55 | .17 |

| Perceived Financial Insecurity | .24* | 2.44* | .08 | .82 | .016 |

| Model 4 | F(7,89) = 2.53*; adjusted R2 = .10* | ||||

| Age | −.02 | −.17 | −.91 | .77 | 0.87 |

| Gender | .11 | 1.10 | −1.21 | 4.19 | 0.28 |

| Emotional Abuse | .43* | 2.48* | .16 | 1.42 | 0.015 |

| Physical Abuse | −.09 | −.51 | −1.30 | .77 | 0.61 |

| Sexual Abuse | −.03 | −.16 | −.75 | .63 | 0.87 |

| Emotional Neglect | .06 | .44 | −.54 | .84 | 0.66 |

| Physical Neglect | −.02 | −.13 | −.91 | .80 | 0.90 |

| Model 5 | F(3,93) = 3.39*; adjusted R2 = .10* | ||||

| Age | .03 | .25 | −.73 | .94 | .81 |

| Gender | .16 | 1.60 | −.52 | 4.83 | .11 |

| Observed Harsh Parenting | .28* | 2.83* | .14 | .82 | .006 |

| Model 6 | F(3,93) = 2.88*; adjusted R2 = .06* | ||||

| Age | .03 | .26 | −.73 | .95 | .80 |

| Gender | .13 | 1.35 | −.86 | 4.50 | .18 |

| Observed Warm/Supportive Parenting | −.26* | −2.55* | −.96 | −.12 | .01 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

For the next set of models, ACEs served as independent variables, adolescents’ symptoms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms as dependent variables, and adolescent age and gender were covariates. For each model examining the impact of individual ACEs (e.g., physical abuse), exposure to other forms of ACEs were included in the model to account for co-occurrence of different types of ACEs in accordance with the multiple individual risk statistical approach (LaNoue et al., 2020). There was a positive association between emotional abuse and adolescents’ internalizing symptoms (β = .44, p = .029, f2 = .06) and externalizing symptoms (β = .43, p = .015, f2 = .06). However, exposure to other ACEs (i.e., physical and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect) were not associated with internalizing or externalizing symptoms (ps > .05).

Last, to test the main effects of observed parenting in association with internalizing and externalizing symptoms, separate models for harsh and warm/supportive parenting were run controlling for adolescents’ age and gender. In further support of Hypothesis 1, there were main effects of harsh parenting (β = .28, p = .006, f2 = .08) and warm/supportive parenting (β = −.26, p = .01, f2 = .07) in association with externalizing symptoms. However, neither harsh nor warm/supportive parenting was significantly associated with internalizing symptoms (ps > .05).

Hypothesis 2: Predicting internalizing and externalizing symptoms from SES and ACEs.

To test the second hypothesis, separate models were conducted with SES and exposure to ACEs as independent variables, adolescents’ symptoms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms as dependent variables, and adolescent age and gender as covariates. For each model examining the impact of individual ACEs (e.g., physical abuse), exposure to other forms of ACEs were included in the model as covariates to control for co-occurrence of different types of ACEs. None of the two-way interactions between ACEs and SES were significant predictors of internalizing or externalizing symptoms (ps > .05).

Hypothesis 3: Predicting internalizing and externalizing symptoms from SES and observed parenting.

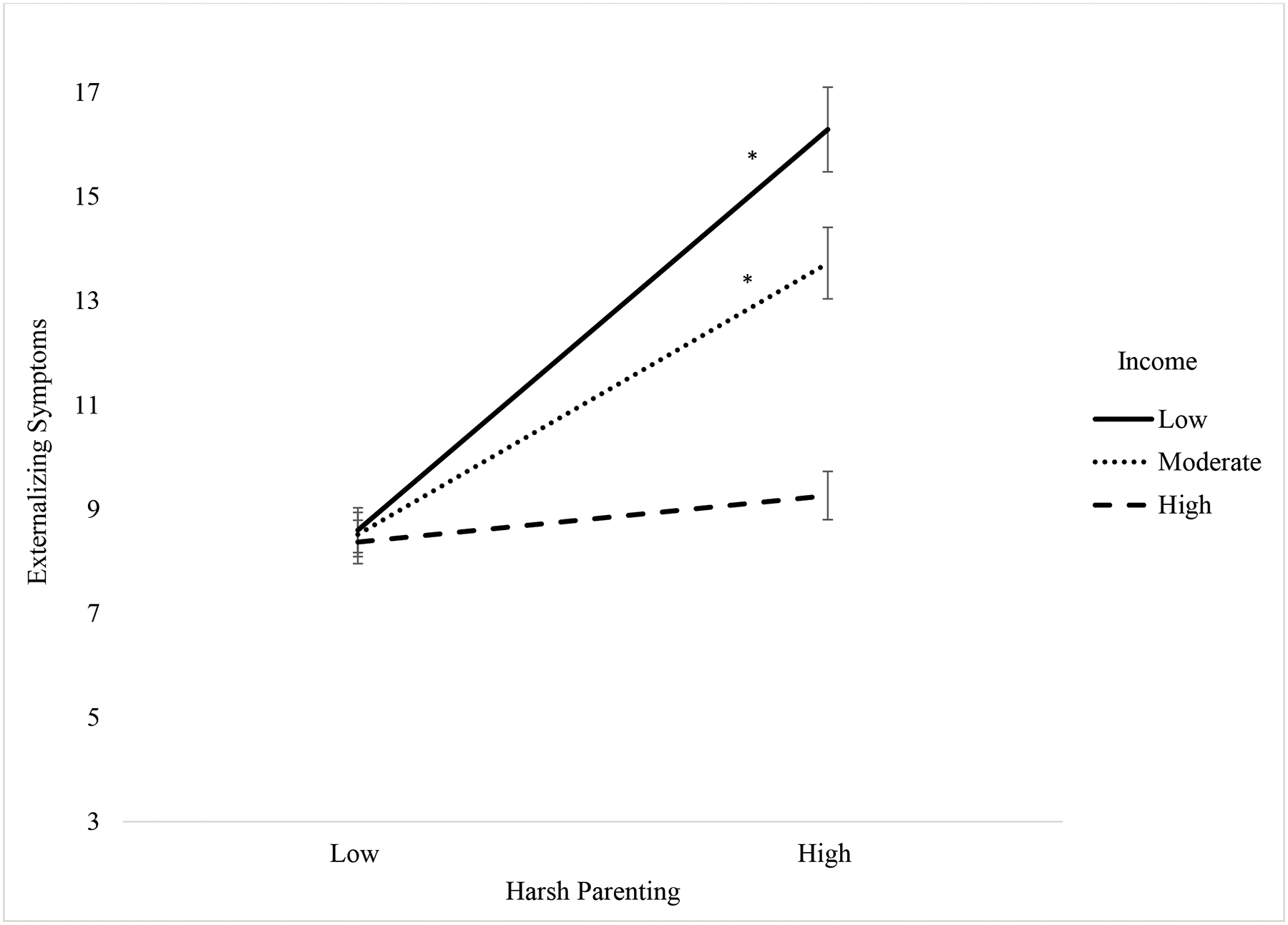

To test the third hypothesis, separate models were conducted with SES and observed parenting as independent variables, adolescents’ symptoms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms as dependent variables, and adolescent age and gender as covariates (Table 4, n = 97). None of the two-way interactions between SES and observed parenting were significant predictors of internalizing symptoms (ps > .05). However, there was a significant interaction between income and observed harsh parenting (β = −.23, p = .02, f2 = .07), such that at low (b = .85, t(91) = 3.84, p < 0.001) and moderate (b = .59, t(91) = 3.56, p < 0.001) levels of income, greater harsh parenting predicted higher externalizing symptoms (Figure 1; n = 97).

Table 4.

Linear Regression Analyses Predicting Externalizing Symptoms from Gross Income and Harsh Parenting

| β | t | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(5,91) = 5.79***; adjusted R2 = .20*** | LL | UL | |||

| Age | .03 | .31 | −.65 | .89 | .76 |

| Gender | .20* | 2.17* | .24 | 5.23 | .03 |

| Observed Harsh Parenting | .28** | 3.05** | .17 | .80 | .003 |

| Gross Income | −.24* | −2.50* | −.00 | −.00 | .01 |

| Income x Harsh Parenting | −.23* | −2.34* | −.00 | −.00 | .02 |

p < .05,

p < .01

Figure 1.

Interaction Between Gross Income and Observed Harsh Parenting Predicting Externalizing Symptoms

Hypothesis 4: Predicting internalizing and externalizing symptoms from ACEs and observed parenting.

To test the fourth hypothesis, separate models were conducted with ACEs and observed parenting as independent variables, adolescents’ symptoms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms as dependent variables, and adolescent age and gender as covariates. For each model examining the impact of individual ACEs (e.g., physical abuse), exposure to other forms of ACEs were included in the model as covariates to control for co-occurrence of different types of ACEs. None of the two-way interactions between ACEs and observed parenting were significant predictors of internalizing or externalizing symptoms (ps > .05).

Exploratory analyses: Three-way interactions predicting symptoms.

The full models including three-way interactions among SES, ACEs, and observed parenting as predictors of adolescents’ symptoms were conducted (Table 5, n = 97). As with previous models, age, gender, and exposure to other forms of ACEs were included in the model as covariates. None of the three-way interactions predicting internalizing symptoms were significant (ps > .05). There was a significant three-way interaction among perceived financial insecurity, physical abuse, and observed warm/supportive parenting predicting externalizing symptoms (β = −.22, p = .009, f2 = .08). At high levels of financial insecurity and low levels of observed warm/supportive parenting (b = 2.84, t(83) = 2.67, p = 0.009), the association between physical abuse and symptoms was significant, such that adolescents exposed to more physical abuse had higher externalizing symptoms. In contrast, at high levels of financial insecurity, physical abuse negatively predicted externalizing symptoms, such that even if adolescents experienced physical abuse, they had fewer externalizing symptoms when levels of warm/supportive parenting were high (b = −2.24, t(83) = −2.12, p = 0.04).

Table 5.

Three-way Interaction of Financial Insecurity, Physical Abuse, and Warm/Supportive Parenting Predicting Externalizing Symptoms

| β | t | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(13,84) = 19.88***; adjusted R2 = .72*** | LL | UL | |||

| Age | −.05 | −.80 | −1.18 | .61 | .36 |

| Gender | .83*** | 14.20*** | 5.69 | 7.11 | <.001 |

| Emotional Abuse | .23* | 2.34* | .17 | 1.36 | .017 |

| Sexual Abuse | .05 | .55 | −1.16 | 1.13 | .51 |

| Emotional Neglect | −.06 | −.76 | −1.26 | .72 | .48 |

| Physical Neglect | −.05 | −.69 | −1.40 | .54 | .48 |

| Physical Abuse | .08 | .83 | −.92 | 1.48 | .47 |

| Observed Warm/Supportive Parenting | −.08 | −1.35 | −.82 | .16 | .12 |

| Financial Insecurity | .13 | 2.06 | −.18 | .97 | .10 |

| Financial Insecurity x Warm/Supportive Parenting | −.10 | −1.50 | −.23 | .05 | .10 |

| Financial Insecurity x Physical Abuse | .07 | .79 | −.47 | .74 | .58 |

| Physical Abuse x Warm/Supportive Parenting | −.06 | −.86 | −.63 | .54 | .40 |

| Financial Insecurity x Physical Abuse x Parenting | −.22** | −2.47** | −.31 | −.05 | .009 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p<.001

Multiplicity Corrections.

To address potentially inflated type I error rates due to multiple comparisons, we utilized Bonferroni corrections. After correcting for multiplicity, the effect for emotional abuse as a predictor of internalizing symptoms approached significance (adjusted p-value = .07). Further, after Bonferroni corrections, the interaction between income and harsh parenting in association with externalizing symptoms approached significance (adjusted p-value = .06). However, all significant main effects and the three-way interaction between financial insecurity, physical abuse, and warm/supportive parenting remained significant after Bonferroni corrections.

Discussion

The current multi-method and multi-informant study investigated the associations of ACEs, observed parenting, and SES with youth’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Findings suggest that lower SES is associated with higher internalizing and externalizing symptoms, while exposure to emotional abuse and observed parenting were associated specifically with externalizing symptoms. Two and three-way interactions were found among SES, parenting and ACEs as predictors of externalizing, but not internalizing symptoms. Findings build on prior research by investigating interactive effects among SES, ACEs, and observed parenting, suggesting that these factors may infer both risk and resilience for psychopathology.

In support of Hypothesis 1, lower SES was associated with heightened internalizing and externalizing symptoms. This is consistent with prior work suggesting that family income is associated with childhood psychopathology (e.g., Yoshikawa et al., 2012). The different facets of SES varied in the strength of their associations with symptoms. For example, perceived financial insecurity had the strongest association with internalizing symptoms, and gross income had stronger associations with internalizing and externalizing symptoms relative to parental education. This is in line with work suggesting that different aspects of SES may have distinct associations with youth psychopathology (Duncan, 2003). It is possible that the mechanism underlying these associations involves the extent to which parents can meet their children’s needs. Accordingly, their income and financial insecurity may be more salient predictors of youth symptoms of psychopathology given their inherent associations with access to resources.

Consistent with prior work suggesting that emotional abuse is related to externalizing symptoms in adolescence (Heleniak et al., 2016), there was a positive association between emotional abuse exposure and externalizing problems in multivariate regression analyses. Associations between other types of ACEs with internalizing and/or externalizing symptoms were not significant. However, it is notable that a significant three-way interaction emerged among observed parenting, physical abuse, and financial insecurity. Thus, it is possible that the association between some ACEs and externalizing problems may be stronger when additional sources of risk and resilience (i.e., harsh vs. warm/supportive parenting practices) are present. While observed parenting was not associated with internalizing symptoms, youth had fewer externalizing symptoms when their parents engaged in higher levels of warm and supportive parenting behaviors and lower levels of harsh parenting behaviors. This is consistent with research suggesting that parenting practices characterized by warmth and attunement to children’s needs are associated with adaptive adjustment in youth (Gaertner et al., 2010).

The two-way interactions between SES and ACEs were not significant predictors of symptoms (Hypothesis 2). However, in support of Hypothesis 3, a significant two-way interaction emerged. Results showed that at lower levels of income, greater observed harsh parenting was associated with higher externalizing symptoms. While these results should be interpreted with caution due to the resultant marginal association following multiplicity corrections, the interaction effect suggests that the risk associated with harsh parenting may be exacerbated by lower income.

The two-way interactions between observed parenting and ACEs were not associated with symptoms (Hypothesis 4). However, we found a significant three-way interaction among perceived financial insecurity, physical abuse, and warm/supportive parenting where the association between adolescents’ physical abuse exposure and heightened externalizing symptoms was the strongest when financial insecurity was high, and levels of warm/supportive parenting were low. In contrast, when parents engaged in higher levels of warm and supportive parenting practices, this appeared to provide a buffer against the experience of physical abuse regardless of perceived financial insecurity. This is consistent with prior work suggesting that positive parenting practices may provide a buffer against the negative effects of ACEs (Yamaoka & Bard, 2019). Further, findings extend prior work by demonstrating that parenting characterized by warmth and attunement to youths’ needs may ameliorate the risk associated with multiple sources of adversity (i.e., ACEs exposure and low SES). Parenting is a well-established modifiable protective factor (e.g., Compas et al., 2010; Traub & Boynton-Jarrett, 2017) that may enhance resiliency in youth (Yamaoka & Bard, 2019). Thus, interventions aimed at promoting warm/supportive parenting practices are a crucial clinical aim, especially for youth exposed to early life adversity.

Unexpectedly, ACEs exposure and observed parenting were not significantly associated with youths’ internalizing symptoms. While we expected associations with both internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, findings linking ACEs exposure and parenting practices with youth psychopathology are mixed in their associations with internalizing and externalizing symptoms. There is evidence that ACEs exposure and harsh parenting behaviors are associated with externalizing behavior in youth (Appleyard et al., 2005; McLaughlin et al, 2012; Yan & Ansari, 2017). In particular, conceptualizations of possible mechanisms underlying the association between harsh parenting and externalizing psychopathology posit that this type of parenting may impede the development of emotion- and self-regulation skills, resulting in heightened externalizing symptoms (Belsky et al, 2007; Wiggins et al., 2015). These associations may be exacerbated by the presence of additional factors that are linked with the development of externalizing psychopathology, including low SES and exposure to ACEs. Thus, the accumulation of multiple risk factors may be more strongly associated with adolescents’ externalizing symptoms relative to internalizing symptoms. Additional work utilizing longitudinal designs and larger sample sizes is necessary to clarify these associations.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

The current study has several important strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first examination of associations among adolescents’ ACEs exposure, SES, observed parenting, and symptoms of psychopathology. Findings build on prior work by investigating the unique contributions of different facets of SES, as well as identifying interactive associations among physical abuse exposure, observed warm/supportive parenting, and financial insecurity with adolescents’ externalizing symptoms. We utilized a multi-informant, multi-method design and observational measures of parenting behaviors, which limits the possibility of shared method variance among measures (Rowe & Kandel, 1997). Lastly, given the common co-occurrence of multiple types of ACEs, multiple individual risk regression models (Henry et al., 2021; LaNoue et al., 2020) allowed for a detailed assessment of the distinct impact of individual ACEs exposure given the presence or absence of other ACEs.

The current study has limitations that can be addressed in future research. First, as the study was cross-sectional, causal inferences cannot be made regarding the relations among ACEs exposure, SES, parenting, and adolescents’ symptoms of psychopathology. Given differential findings among different facets of SES and types of ACEs, additional work is needed to clarify if particular forms of ACEs (i.e., physical vs. emotional abuse) and/or SES (i.e., parental education vs. gross income) incur greater risk for psychopathology over time. Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that the association between youth externalizing problems and harsh parenting practices may be bidirectional (e.g., Yan & Ansari, 2017). Longitudinal analyses will provide a more rigorous assessment of the temporal association between parenting practices and youth psychopathology. Second, the demographics of the current sample may limit the generalizability of findings. While we were able to detect significant effects, variability across some facets of SES was limited. Future research should target increased inclusion of families from varied socioeconomic backgrounds and levels of ACEs. Third, power analyses indicated that we were able to detect medium-to-large effects when examining interactions between ACEs and SES (Hypothesis 2), ACEs and parenting (Hypothesis 4), and the main effects of ACEs in association with symptoms. While we failed to find support for these hypotheses, it is likely that we were underpowered to detect effects that would enable us to fully understand the nature of these associations. As such, future research should examine these effects in larger samples to clarify the associations among SES, ACEs, and parenting in association with adolescents’ symptoms of psychopathology. Fourth, given the importance of better understanding more subjective aspects of socioeconomic standing (Quon & McGrath, 2014), we created a composite score of perceived financial insecurity for use in this study to probe this less-studied facet of SES. While we were able to establish good internal consistency within the present sample, it is important to note that additional research on the validation of this measure is warranted prior to use of this measure in future studies. Last, while we assessed the associations between ACEs exposure and psychopathology in adolescence, an important period for the onset of psychopathology (Kessler et al., 2012), the exact timing of exposure was unknown. Given research suggesting greater risk associated with early exposure to childhood trauma (e.g., Shonkoff, 2010), future research assessing ACEs exposure at critical points in development (i.e., early childhood) is needed.

Conclusion

In sum, the present research suggests that lower SES is associated with heightened internalizing and externalizing symptoms, while ACEs exposure and observed parenting are related to adolescents’ externalizing symptoms. Furthermore, the association between adolescents’ exposure to physical abuse and perceived financial insecurity with externalizing symptoms was associated with the extent to which parents engaged in warm/supportive parenting behaviors. Findings support a cumulative risk model, in which the presence of multiple risk factors incurs greater vulnerability to externalizing problems. In contrast, findings suggest that warm/supportive parenting may provide a buffer for adolescents exposed to physical abuse. The present study highlights the need for additional research investigating the impact of ACEs, SES, and parenting on youth adjustment, and underscores the importance of parenting as a key intervention target.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R21 HD9084854 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and Grant T32-MH18921 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

All procedures were approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (IRB # 181531).

Declarations of conflict of interest: none

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer MA, Fiese BH, Gold JI, Cutuli JJ, Holmbeck GN, Goldbeck L, … & Patterson J (2008). Evidence-based assessment in pediatric psychology: Family measures. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(9), 1046–1061. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen MH, & Sroufe AL (2005). When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(3), 235–245. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4(1, Pt.2), 1–103. 10.1037/h0030372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pasco Fearon RM, & Bell B (2007). Parenting, attention and externalizing problems: testing mediation longitudinally, repeatedly and reciprocally. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 48(12), 1233–1242. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01807.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, … & Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bøe T, Sivertsen B, Heiervang E, Goodman R, Lundervold AJ, & Hysing M (2014). Socioeconomic status and child mental health: The role of parental emotional well-being and parenting practices. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(5), 705–715. 10.1007/s10802-013-9818-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, Van Der Ende J, & Verhulst FC (2004). Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 75(5), 1523–1537. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry KE, Gerstein ED, & Ciciolla L (2019). Parenting stress and children’s behavior: Transactional models during Early Head Start. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(8), 916. 10.1037/fam0000574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JK, Kelley MS, & Wang D (2018). Neighborhood characteristics, maternal parenting, and health and development of children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(3–4), 476–491. 10.1002/ajcp.12276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayborne ZM, Kingsbury M, Sampasa-Kinyaga H, Sikora L, Lalande KM, & Colman I (2021). Parenting practices in childhood and depression, anxiety, and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: a systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(4), 619–638. 10.1007/s00127-020-01956-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Champion JE, Forehand R, Cole DA, Reeslund KL, …. Roberts L (2010). Coping and Parenting: Mediators of 12-month outcomes of a family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention with families of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 623–634. 10.1037/a0020459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman H, Noonan K, Reichman NE, & Schultz J (2012). Effects of financial insecurity on social interactions. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 41(5), 574–583. 10.1016/j.socec.2012.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Currie CL, Higa EK, & Swanepoel LM (2021). Socioeconomic Status Moderates the Impact of Emotional but not Physical Childhood Abuse on Women’s Sleep. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1–11. 10.1007/s42844-021-00035-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devenish B, Hooley M, & Mellor D (2017). The pathways between socioeconomic status and adolescent outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1–2), 219–238. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/10.1002/ajcp.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, Mistry RS, Wadsworth ME, López I, & Reimers F (2013). Best practices in conceptualizing and measuring social class in psychological research. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13(1), 77–113. 10.1111/asap.12001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WJ (1960). Simplified estimation from censored normal samples. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, & Giles WH (2001). Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. JAMA, 286(24), 3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ (2003). Off with Hollingshead: Socioeconomic resources, parenting, and child development. In Magnuson KA, (Ed.), Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development (1st ed., pp. 83–106). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Taylor ZE, Widaman KF, & Spinrad TL (2015). Externalizing symptoms, effortful control, and intrusive parenting: A test of bidirectional longitudinal relations during early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 27(4pt1), 953–968. 10.1017/S0954579415000620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdfelder E, Faul F, & Buchner A (1996) GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 28(1) 1–11. 10.3758/BF03203630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Li D, & Whipple SS (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1342–1396. 10.1037/a0031808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, & Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner AE, Fite PJ, & Colder CR (2010). Parenting and friendship quality as predictors of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in early adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(1), 101–108. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9289-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, & McMahon SD (2003). Stress and child/adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 447–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Oppenheimer C, Jenness J, Barrocas A, Shapero BG, & Goldband J (2009). Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: Review of processes contributing to stability and change across time. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(12), 1327–1338. 10.1002/jclp.20625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heleniak C, Jenness JL, Vander Stoep A, McCauley E, & McLaughlin KA (2016). Childhood maltreatment exposure and disruptions in emotion regulation: A transdiagnostic pathway to adolescent internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(3), 394–415. doi: 10.1007/s10608-015-9735-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LM, Gracey K, Shaffer A, Ebert J, Kuhn T, Watson KH, Gruhn M, Vreeland A, Siciliano R, Dickey L, Lawson V, Broll C, Cole DA, & Compas BE (2021). Comparison of three models of adverse childhood experiences: Associations with child and adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(1), 9–25. 10.1037/abn0000644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, … & Dunne MP (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon HS, & Chun J (2017). The influence of stress on juvenile delinquency: focusing on the buffering effects of protective factors among Korean adolescents. Social Work in Public Health, 32(4), 223–237. 10.1080/19371918.2016.1274704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmakis KA, & Chandler GE (2015). Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: a systematic review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27(8), 457–465. DOI: 10.1002/2327-6924.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley K (2005). The effects of nonnormal distributions on confidence intervals around the standardized mean difference: Bootstrap and parametric confidence intervals. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65(1), 51–69. 10.1177/0013164404264850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, … & Merikangas KR (2012). Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(4), 372–380. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaNoue MD, George BJ, Helitzer DL, & Keith SW (2020). Contrasting cumulative risk and multiple individual risk models of the relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and adult health outcomes. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12874-020-01120-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, & Steinberg L (2009). The scientific study of adolescent development: Historical and contemporary perspectives. In Lerner RM & Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Individual bases of adolescent development (pp. 3–14). John Wiley & Sons Inc. 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Bares CB, & Delva J (2013). Parenting, family processes, relationships, and parental support in multiracial and multiethnic families: An exploratory study of youth perceptions. Family Relations, 62(1), 125–139. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00751.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Han Y, Grogan-Kaylor A, Delva J, & Castillo M (2012). Corporal punishment and youth externalizing behavior in Santiago, Chile. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 481–490. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschi T, Morgen K, Bradley C, & Hatcher SS (2008). Exploring gender differences on internalizing and externalizing behavior among maltreated youth: Implications for social work action. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 25(6), 531–547. 10.1007/s10560-008-0139-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Alegría M, Costello EJ, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, & Kessler RC (2012). Food insecurity and mental disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(12), 1293–1303. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley A, & Sachs-Ericsson N (2009). Predictors of parental physical abuse: The contribution of internalizing and externalizing disorders and childhood experiences of abuse. Journal of Affective Disorders, 113(3), 244–254. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, & Conger RD (2001). The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. Iowa State University: Ames, Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J, & Bernstein L (1994). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Milan S, & Vannucci A (2017). Gender differences in anxiety trajectories from middle to late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 826–839. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-016-0619-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, et al. (2004). Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development, 75, 1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peverill M, Dirks MA, Narvaja T, Herts KL, Comer JS, & McLaughlin KA (2021). Socioeconomic status and child psychopathology in the United States: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101933. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska PJ, Stride CB, Croft SE, & Rowe R (2015). Socioeconomic status and antisocial behaviour among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 35, 47–55. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quon EC, & McGrath JJ (2014). Subjective socioeconomic status and adolescent health: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 33(5), 433–447. 10.1037/a0033716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss F (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 90, 24–31. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin AL, & Foster SL (1989). Negotiating parent-child conflict: A behavioral family systems approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, & Kandel D (1997). In the eye of the beholder? Parental ratings of externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25(4), 265–275. 10.1023/A:1025756201689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salk RH, Hyde JS, & Abramson LY (2017). Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychological Bulletin, 143(8), 783. 10.1037/bul0000102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, & Graham JW (2002). Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully C, McLaughlin J, & Fitzgerald A (2020). The relationship between adverse childhood experiences, family functioning, and mental health problems among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Family Therapy, 42(2), 291–316. 10.1111/1467-6427.12263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP (2010). Building a new biodevelopmental framework to guide the future of early childhood policy. Child Development, 81(1), 357–367. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele H, Bate J, Steele M, Dube SR, Danskin K, Knafo H, … & Murphy A (2016). Adverse childhood experiences, poverty, and parenting stress. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 48(1), 32–38. 10.1037/cbs0000034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundel B, Burton E, Walls T, Buenaver L, & Campbell C (2018) Socioeconomic status moderates the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and insomnia. Sleep, 41(1), A134–A135, 10.1093/sleep/zsy061.349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell L (2013). Using Multivariate Statistics (Sixth Ed.) Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Traub F, & Boynton-Jarrett R (2017). Modifiable resilience factors to childhood adversity for clinical pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 139(5). 10.1542/peds.2016-2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin J, Alharbi N, Uddin H, Hossain MB, Hatipoğlu SS, Long DL, & Carson AP (2020). Parenting stress and family resilience affect the association of adverse childhood experiences with children’s mental health and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 272, 104–109. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D, McCartney G, Smith M, & Armour G (2019). Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(12), 1087–1093. 10.1136/jech-2019-212738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JL, Mitchell C, Hyde LW, & Monk CS (2015). Identifying early pathways of risk and resilience: The codevelopment of internalizing and externalizing symptoms and the role of harsh parenting. Development and Psychopathology, 27(4pt1), 1295–1312. 10.1017/S0954579414001412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka Y, & Bard DE (2019). Positive parenting matters in the face of early adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(4), 530–539. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan N, & Ansari A (2017). Bidirectional relations between intrusive caregiving among parents and teachers and children’s externalizing behavior problems. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 41, 13–20. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MBH, Pilkington PD, Ryan SM, & Jorm AF (2014) Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 156, 8–23. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MBH, & Jorm AF (2015) Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalizing problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 175, 424–440. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, & Beardslee WR (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: implications for prevention. American Psychologist, 67(4), 272. 10.1037/a0028015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.