ABSTRACT

Background

Plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL) is a novel biomarker for age-related neurodegenerative disease. We tested whether NfL may be linked to cardiometabolic risk factors, including BMI, the allostatic load (AL) total score (ALtotal), and related AL continuous components (ALcomp). We also tested whether these relations may differ by sex or by race.

Methods

We used data from the HANDLS (Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span) study [n = 608, age at visit 1 (v1: 2004–2009): 30–66 y, 42% male, 58% African American] to investigate associations of initial cardiometabolic risk factors and time-dependent plasma NfL concentrations over 3 visits (2004–2017; mean ± SD follow-up time: 7.72 ± 1.28 y), with outcomes being NfLv1 and annualized change in NfL (δNfL). We used mixed-effects linear regression and structural equations modeling (SM).

Results

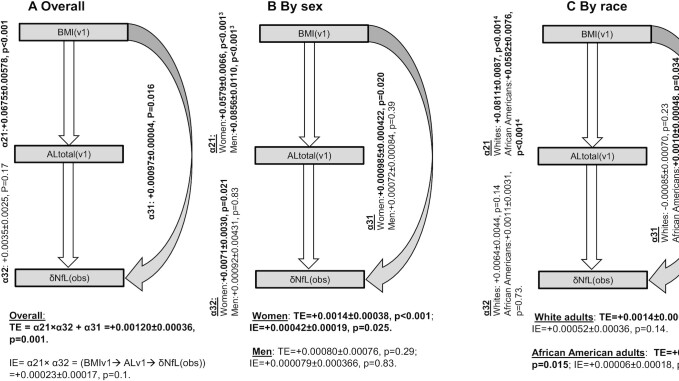

BMI was associated with lower initial (γ01 = −0.014 ± 0.002, P < 0.001) but faster increase in plasma NfL over time (γ11 = +0.0012 ± 0.0003, P < 0.001), a pattern replicated for ALtotal. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), serum total cholesterol, and resting heart rate at v1 were linked with faster plasma NfL increase over time, overall, while being uncorrelated with NfLv1 (e.g., hsCRP × Time, full model: γ11 = +0.004 ± 0.002, P = 0.015). In SM analyses, BMI's association with δNfL was significantly mediated through ALtotal among women [total effect (TE) = +0.0014 ± 0.00038, P < 0.001; indirect effect = +0.00042 ± 0.00019, P = 0.025; mediation proportion = 30%], with only a direct effect (DE) detected among African American adults (TE = +0.0011 ± 0.0004, P = 0.015; DE = +0.0010 ± 0.00048, P = 0.034). The positive associations between ALtotal/BMI and δNfL were mediated through increased glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) concentrations, overall.

Conclusions

Cardiometabolic risk factors, particularly elevated HbA1c, should be screened and targeted for neurodegenerative disease, pending comparable longitudinal studies. Other studies examining the clinical utility of plasma NfL as a neurodegeneration marker should account for confounding effects of BMI and AL.

Keywords: neurofilament light, allostatic load, body mass index, urban adults, race, cognition

Introduction

When axons are damaged with age and in many neurodegenerative diseases, certain cytoskeletal proteins referred to as neurofilaments are often released into the extracellular space, then the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and finally may transmigrate into blood at a lower concentration (1). Neurofilament light chain (NfL) is a novel biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases detectable in blood, reflecting axonal degeneration. Accumulating data indicate that concentrations of plasma NfL are associated with Alzheimer disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative diseases (2–8). In fact, plasma NfL concentrations are associated with cognitive decline in nondemented adults (9, 10) and are able to predict the onset of AD (11, 12). Plasma NfL is attractive as a biomarker, because it uses less invasive procedures than do CSF assessments. NfL measured in CSF is positively correlated with plasma NfL (13, 14) and plasma NfL concentrations are associated with neuroimaging measures of cognition (1, 15, 16). Compared with neuroimaging measures or tests of cognitive performance, plasma NfL as a biomarker reduces both time and expense in assessing risk of dementia with high-risk groups in randomized controlled trials. As for CSF NfL, plasma NfL concentration exhibits an upward-trending trajectory with age. This positive correlation may be in part explained by increased BMI and other related metabolic disorders such as renal dysfunction as was shown in 2 recent studies (17, 18), which in turn are largely determined by poor dietary quality and other nutritional factors (19–24). Obesity, directly measured with BMI, along with its associated cardiometabolic disorders and markers of inflammation [e.g., abdominal obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, elevated blood C-reactive protein, reduced serum albumin (ALB)], become more prevalent with age, particularly between early and mid-life (25, 26); they are also associated with later-life cognitive decline and impairment (27–31) and adverse neuroimaging outcomes (32–38). Moreover, neurocognitive outcomes were associated with CSF biomarkers of neurodegeneration (e.g., Aβ42:40 ratio, tau, and NfL) (39–41), as well as plasma NfL in more recent studies (2–4, 15, 40, 42–46). However, it is still unknown whether age-related cardiometabolic disorders are independent risk factors for the rate of increase in plasma NfL over time.

If these associations exist then they are likely to differ markedly across sociodemographic factors, particularly across sex and race groups, given the sex- and race-specific associations between cardiometabolic risk and neurocognitive aging outcomes (47–50). Moreover, previous reports have shown a direct association between cardiometabolic risk and adverse neurocognitive outcomes, and of increased plasma NfL with those same outcomes. Therefore, a positive association between cardiometabolic risk and plasma NfL would suggest that cardiometabolic risk needs to be accounted for as a potential confounder in studies of the clinical utility of plasma NfL as an early marker of neurodegeneration. Plasma NfL may also be a pathway through which cardiometabolic risk is linked to neurocognitive outcomes.

The present study investigated the longitudinal associations of BMI (continuous and categorical) and the allostatic load (AL) [total score (ALtotal) and components] with plasma NfL (baseline BMI/AL compared with baseline plasma NfL; baseline BMI/AL compared with annual rate of change in plasma NfL), independently of key exogenous confounders, and across sex and race. The study also assessed whether ALtotal mediated the association between BMI and the annual rate of change in plasma NfL, across sex and race groups. Finally, the study tested which individual components of the AL mediated the total effects (TEs) of AL and BMI on annual rate of change in plasma NfL, overall and across sex and race groups.

Methods

Database

The sample was selected from the HANDLS (Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span) study (51). Initiated in 2004, HANDLS is a longitudinal study involving socioeconomically diverse White and African-American adult women and men who resided in Baltimore, MD. Baseline data (visit 1, v1) were collected in 2 phases during 2004–2009. Phase I consisted of a home visit, whereby recruitment, consent, and screening procedures as well as a household in-person interview were performed, including the first 24-h dietary recall. During Phase II (v1), an in-person complete physical health examination was performed within Medical Research Vehicles (MRVs) including a second 24-h dietary recall. Participants were invited to participate in follow-up in-person visits [visit 2 (v2): 2009–2013 and visit 3 (v3): 2013–2017] whereby similar protocols as for v1 (Phase II) were applied. Fasting blood samples were drawn from participants who provided written informed consent during in-person examinations. The study protocol of HANDLS was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH.

Study sample

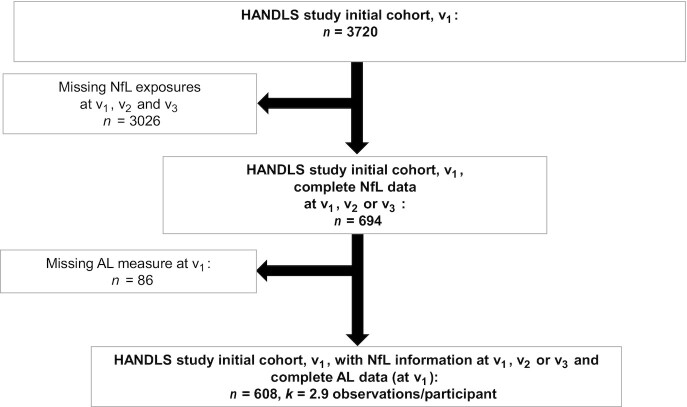

In our present study, ≤3 repeats on plasma NfL concentrations were available from v1, v2, and/or v3. AL components and therefore ALtotal were measured also at ≤3 visits. However, in this study, we only examine v1 exposures. As shown in the study design flowchart (Figure 1), among 3720 initially recruited HANDLS participants, n = 694 had complete v1, v2, and/or v3 data on plasma NfL. Of those participants, n = 608 had data on v1 AL. Mean ± SD follow-up time (between v1 and v3) for the final analytic sample with complete v3 data (n = 596 participants) was 7.72 ± 1.28 y. Supplemental Method 1 shows a detailed description of sample selection with respect to the plasma NfL outcome. Compared with the initial sample with incomplete data for our analysis, the final sample had a lower proportion of individuals living below poverty (27% compared with 44%, P < 0.001, χ2 test). Of n = 608, 606 had complete data to compute the observed annualized NfL change (δNfLobs), and thus an additional n = 2 were excluded for the structural equations modeling (SM) analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flowchart. AL, allostatic load; HANDLS, Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span; NfL, plasma neurofilament light chain; v1, visit 1; v2, visit 2; v3, visit 3.

Plasma NfL

Fasting blood samples were collected between 09:30 and 11:30 into EDTA blood collection tubes. The tubes were centrifuged at 4°C and at 600 × g for 15 min followed by the removal of the buffy coat. These steps were repeated twice and samples were visually examined for hemolysis. Plasma samples were stored in aliquots at −80°C after their collection. Plasma NfL concentrations were quantified using the Simoa® NF-light Advantage Kit (Quanterix) following kit instructions. Samples from the different visits were run on the same plate for each individual and plates were balanced for individuals within each demographic group (race/sex/poverty). Plasma samples were diluted 4-fold, and concentrations were adjusted for this dilution correction. Pooled plasma samples from 2 individuals were run in duplicate on all plates; intra-assay and interassay CVs were 4.5% and 7%, respectively. The limit of detection was 0.152 pg/mL and the lower limit of quantification was 0.696 pg/mL. The upper limit of detection was 1872 pg/mL. Plasma NfL was the main outcome of interest, measured for ≤3 repeats per participant, at v1, v2, and/or v3.

AL

We relied on a previously reported method to compute ALtotal (52). This method sums cardiovascular [systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse rate], metabolic [total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), sex-specific waist-to-hip ratio (WHR)], and inflammatory [serum ALB and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP)] risk indicators. As summarized in Supplemental Table 1, multiple clinical criteria were used to obtain risk indicators which were subsequently summed with equal weighting to compute an ALtotal that ranges between 0 and 9. The higher the ALtotal, the more the overall cardiometabolic risk. Total cholesterol (mg/dL), HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), hsCRP (mg/dL), ALB (g/dL), and HbA1c (%) were determined by contract laboratories (Quest Diagnostics), using reference analytical methods. Using standard protocols, trained examiners measured WHR, radial pulse (beats/min), and SBP and DBP (mm Hg). In particular, blood pressure was measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer and the arithmetic means of left and right SBP and DBP were used in this analysis.

BMI

BMI was calculated as weight divided by height (kg/m2). In part of the analysis, the TE of BMI on plasma NfL change was tested as potentially being mediated through ALtotal. In addition, both continuous BMI and weight status (categorical BMI) were included among potential exposures, alternative to ALtotal, in mixed-effects linear regression models. Weight status was defined as follows: BMIv1 <18.5—underweight; BMIv1 ≥18.5 and <25—normal weight; BMIv1 ≥25 and <30—overweight; and BMIv1 ≥30—obese.

Covariates

We assessed multiple covariates as potential confounders, given previous significant associations with plasma NfL, and these are considered antecedent risk factors to the AL. These included v1 age (continuous; y), sex (male, female), race (white, African American), poverty status (below compared with above 125% of the federal poverty line), and educational attainment (less than high school, high school, more than high school). We operationalized poverty status using the 2004 US Census Bureau poverty thresholds (53) based on household income and total family size (including children <18 y old). Some of the lifestyle and health-related factors were considered as potential confounders, given their potential impact on both AL and plasma NfL, although they were not necessarily on the causal pathway between AL and plasma NfL. Those factors were current smoking status (0 = no compared with 1 = yes), illicit drug use (0 = no compared with 1 = yes, using any of marijuana, opiates, and cocaine), the Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HEI-2010) (54) whereby overall diet quality was measured based on food- and macronutrient-related US dietary guidelines for Americans, total energy intake (kcal/d), and the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) total score for depressive symptoms (55). Sex and race were the main effect modifiers in our analyses. Basic sociodemographic covariates were complete by design, whereas other measures assessed during the MRV phase of v1 had some missing data. However, after accounting for missingness in all key variables (v1 AL and δNfL), covariates had <5% missingness individually out of the final eligible sample (n = 608). Thus, multiple imputation was conducted as described in the next section.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata release 16 (56). First, study sample characteristics were described in terms of fixed, baseline, and longitudinal changes in key variables across race and sex, using means and proportions, as well as bivariate linear, logistic, and multinomial logit models to examine racial and sex differences in continuous, binary, and categorical multilevel covariates, respectively. We then further adjusted those models for the remaining sociodemographic factors among age, sex, race, and poverty status to determine whether racial and sex differences remained statistically significant. Second, for testing our main hypotheses, a series of mixed-effects linear models were conducted (Supplemental Method 2). The outcome in these models was plasma NfL measured longitudinally with ≤3 repeats, whereas the main exposure was ALtotal measured at v1 (2004–2009). The modeling process consisted of 2 model sets, with an increasing level of adjustment for potentially confounding covariates. These covariates were assumed to confound the relation between v1 ALtotal and v1 plasma NfL as well as v1 ALtotal and annualized change in plasma NfL, and thus were included among the main effects and interacted with Time. Model 1 adjusted for only sociodemographic variables: age at v1, sex, race, poverty status, and educational attainment. Model 2 adjusted for all other lifestyle and health-related covariates listed in the Covariates section, excluding BMI at v1. We ensured sample size consistency across models by conducting multiple imputation for covariates (aside from sociodemographics). This was accomplished with chained equations (5 imputations, 10 iterations), with all covariates used simultaneously in the estimation process, similarly to previous studies (57, 58). Nine AL continuous components (ALcomp) measured at v1 were considered as secondary predictors, substituting ALtotal in these models, separately. Thus, in these multiple mixed-effects linear regression models, we applied Models 1 and 2 to 1 key exposure (ALtotal) and 9 secondary predictors (ALcomp), 1 key outcome (plasma NfL) with ≤3 repeats [effect of ALtotal on v1 plasma NfL (NfLv1) and annualized change in NfL (δNfL) over time between v1 and v3], and 2 main stratifying variables (race and sex). In all these models, plasma NfL was loge transformed, as done in other studies [e.g., (45)]. Using a simplified model with Time as the only predictor, annualized change in plasma NfL was also estimated for each participant in the final analytic sample, by predicting random effects from the model and estimating the empirical Bayes estimator for annualized change in plasma NfL. This estimation process used the largest available sample with 1, 2, or 3 measures on plasma NfL and assumed missingness of outcome at random. Given that the variance of this estimator is significantly different from the observed annualized change, it was only used to validate δNfLobs (Supplemental Figure 1). The latter was estimated by taking the arithmetic mean for annualized changes between v1 and v2, between v2 and v3, and between v1 and v3. Racial and sex differences in the association between v1 ALtotal and plasma NfL at v1 were tested using ALtotal × Race and ALtotal × Sex interaction terms in separate models, respectively. In each of these models, heterogeneity by race and sex in the association between ALtotal and δNfL were tested by also adding ALtotal × Time × Race and ALtotal × Time × Sex, respectively. This modeling process was repeated for BMI and weight status, substituting ALtotal.

Two sets of structural equations models were constructed to test pathways explaining annual rate of change in plasma NfL, predicted from a simple mixed-effects regression model with random effects added to intercept and slope (δNfLobs), through mediating pathways involving several cardiometabolic risk factors. The first SM set examined whether BMI at v1 was associated with δNfLobs through ALtotal at v1, overall and stratifying separately by sex and race. Thus, this SM set attempted to test whether ALtotal mediated the association between BMI and δNfL. In contrast, a second SM set examined individual ALcomp (e.g., total cholesterol) as alternative mediators between ALtotal at v1 and δNfLobs. In all these models, exogenous covariates included v1 age, sex, race, poverty status, education, current smoking, current illicit drug use, CES-D total score, HEI-2010, and mean energy intake (kcal/d) at v1. These exogenous covariates were allowed to predict all 3 endogenous variables in the system, including (δNfLobs), (v1 BMI), (v1 ALtotal), and (v1 ALcomp). ALcomp included v1 WHR, v1 serum ALB, v1 hsCRP, v1 HbA1c, v1 total cholesterol, v1 HDL cholesterol, v1 resting heart rate (RHR), v1 SBP, and v1 DBP. Supplemental Method 3 provides a detailed description of the SM methods and the estimated parameters and statistics. In a sensitivity analysis with δNfLobs as the final outcome, we examined the mediating effect of ALcomp in the BMI–δNfLobs relation, overall and by sex and race following a similar analytic strategy.

In all models (mixed-effects and SM), sample selectivity potentially caused by missingness on exposure and outcome data, relative to the initially recruited sample, was corrected by utilizing a 2-stage Heckman selection process. As a first stage, using a probit model, we predicted an indicator of selection with sociodemographic factors. Those were, in this case, v1 age, race, sex, and poverty status. This model yielded an inverse Mills ratio (IMR), a function of the probability of being selected conditional on those sociodemographic factors. At the second stage, the main models testing the key hypotheses were estimated using multiple mixed-effects linear and SM models, adding among adjusted factors the IMR in addition to the aforementioned covariates (59).

We set the type I error rate a priori for main effects and interactions to 0.05 and 0.10, respectively (60). We illustrated some of the main findings from specific mixed-effects linear regression models using predictive margins (with estimated 95% CIs) of plasma NfL outcome across time, and by ALtotal exposure, overall or stratified by race and/or sex. Pictural representations of SM models were also utilized, where appropriate, to illustrate the potential mediating effects of cardiometabolic risk factors, while stratifying by sex and race.

Results

Study sample characteristics by sex and race

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study sample, while examining differences by sex and by race. The most notable differences were in BMI, which was higher among women than among men, whereas the reverse was true for total caloric intake and current illicit drug use (P < 0.05). ALtotal on average reflected greater cardiometabolic risk among white than among African American adults (1.98 compared with 1.78, P = 0.044). Sex and racial differences were also detected in ALcomp. Specifically, men were at higher cardiometabolic risk than women on HDL cholesterol and DBP, whereas the reverse was true for serum ALB, hsCRP, and total cholesterol. Moreover, African American adults were at higher risk of lower ALB concentrations, and at lower risk of higher HDL cholesterol, than their White counterparts. The loge-transformed plasma NfL concentrations at v1 and v3 were all on average higher among men than among women, with no difference detected by sex for δNfLobs. At each of v1 and v3, loge-transformed plasma NfL concentration was also higher among White adults, even though δNfLobs did not differ across racial groups.

TABLE 1.

Study sample characteristics by sex and by race: HANDLS, 2004–20171

| Overall (n = 608) | Women (n = 352) | Men (n = 256) | P sex | White adults(n = 257) | African American adults (n = 351) | P race | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health-related factors at v1 | |||||||

| Men, % | 42.1 | 0.0 | 100.0 | — | 39.7 | 43.9 | 0.30 |

| African American, % | 57.7 | 56.0 | 60.2 | 0.30 | 0.0 | 100.0 | — |

| Age, y | 47.7 ± 0.4 | 47.7 ± 0.5 | 47.6 ± 0.5 | 0.90 | 48.4 ± 0.5 | 47.2 ± 0.5 | 0.11 |

| Below poverty, % | 27.0 | 28.1 | 25.4 | 0.45 | 26.1 | 27.6 | 0.67 |

| Education, % | |||||||

| <High school | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 0.78 | 6.8 | 3.4 | 0.093 |

| High school | 58.2 | 57.1 | 59.8 | Ref. | 59.5 | 57.3 | Ref. |

| >High school | 36.9 | 37.9 | 35.5 | 0.53 | 33.7 | 39.3 | 0.28 |

| Current illicit drug use, % yes | 15.6 | 9.7 | 23.7 | <0.001* | 12.3 | 18.0 | 0.058 |

| Current tobacco use, % yes | 40.0 | 38.9 | 46.1 | 0.084 | 40.5 | 43.0 | 0.54 |

| Healthy Eating Index-2010 total score | 42.3 ± 0.5 | 42.9 ± 0.7 | 41.3 ± 0.7 | 0.12 | 41.4 ± 0.8 | 42.9 ± 0.7 | 0.18 |

| Energy intake, kcal/d | 1993 ± 40 | 1697 ± 47 | 2399 ± 71 | <0.001* | 1996 ± 73 | 1991 ± 63 | 0.97 |

| CES-D total score | 14.3 ± 0.4 | 14.6 ± 0.6 | 13.9 ± 0.7 | 0.41 | 15.2 ± 0.7 | 13.6 ± 0.6 | 0.070* |

| BMIv1, kg/m2 | 30.3 ± 0.3 | 31.8 ± 0.4 | 28.3 ± 0.4 | <0.001* | 30.4 ± 0.5 | 30.2 ± 0.4 | 0.84 |

| Weight status at v1, % | |||||||

| Underweight: BMIv1 <18.5 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 0.23 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 0.84 |

| Normal: BMIv1 ≥18.5, <25 | 20.9 | 16.2 | 27.3 | <0.001* | 19.8 | 21.7 | 0.72 |

| Overweight: BMIv1 ≥25, <30 | 30.4 | 26.1 | 36.3 | <0.001* | 31.5 | 29.6 | 0.72 |

| Obese: BMIv1 ≥30 | 45.7 | 54.8 | 33.2 | Ref. | 45.5 | 45.9 | Ref. |

| ALtotal at v1 | 1.87 ± 0.05 | 1.91 ± 0.06 | 1.80 ± 0.08 | 0.28 | 1.98 ± 0.07 | 1.78 ± 0.06 | 0.044 |

| ALcomp at v1 | |||||||

| WHR | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.99 ± 0.05 | 0.92 ± 0.00 | 0.081 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 4.33 ± 0.01 | 4.28 ± 0.01 | 4.40 ± 0.02 | <0.001* | 4.36 ± 0.02 | 4.30 ± 0.01 | 0.006* |

| hsCRP,2 mg/L | 0.74 ± 0.05 | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 0.40 ± 0.08 | <0.001* | 0.81 ± 0.07 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 0.26 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.85 ± 0.04 | 5.85 ± 0.05 | 5.86 ± 0.06 | 0.93 | 5.83 ± 0.06 | 5.87 ± 0.04 | 0.55 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 186.1 ± 1.7 | 190.2 ± 2.2 | 180.5 ± 2.6 | 0.004* | 189.6 ± 2.7 | 183.6 ± 2.1 | 0.075 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 53.5 ± 0.7 | 55.9 ± 0.9 | 50.3 ± 1.1 | <0.001* | 50.2 ± 0.9 | 56.0 ± 1.0 | <0.001* |

| Resting heart rate, beat/min | 66.9 ± 0.5 | 67.3 ± 0.6 | 66.4 ± 0.7 | 0.32 | 67.7 ± 0.7 | 66.4 ± 0.6 | 0.14 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 119.5 ± 0.7 | 119.1 ± 0.9 | 120.0 ± 1.0 | 0.48 | 119.3 ± 1.1 | 119.7 ± 0.8 | 0.76 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 72.9 ± 0.4 | 71.7 ± 0.5 | 74.5 ± 0.7 | 0.001* | 72.4 ± 0.6 | 73.2 ± 0.6 | 0.32 |

| Plasma NfL, loge transformed | |||||||

| NfLv1 | 1.98 ± 0.02 | 1.95 ± 0.03 | 2.03 ± 0.03 | 0.039* | 2.11 ± 0.03 | 1.89 ± 0.03 | <0.001* |

| NfLv3 | 2.35 ± 0.02 | 2.28 ± 0.03 | 2.44 ± 0.04 | 0.002* | 2.41 ± 0.04 | 2.30 ± 0.03 | 0.038 |

| δNfLobs 3 | 0.0492 ± 0.0027 | 0.0462 ± 0.0043 | 0.0532 ± 0.0047 | 0.20 | 0.0468 ± 0.0044 | 0.0508 ± 0.0033 | 0.47 |

Values are means ± SEs for continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables. BMI in kg/m2. *P < 0.05 upon further adjustment for age, sex, race, and poverty status in multiple linear and multinomial logit models. ALcomp, allostatic load continuous components; ALtotal, allostatic load total score; BMIv1, BMI at v1; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; HANDLS, Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NfL, neurofilament light chain; v1, visit 1; v3, visit 3; WHR, waist:hip ratio; δNfLobs, observed annualized rate of change in plasma neurofilament light between visit 1 and visit 3.

Loge transformed.

Validated against the empirical Bayes estimator predicted from a mixed-effects linear regression model with NfL as the outcome and Time as the only predictor (Pearson's r >0.80). n = 606. See Table 4 for sample sizes within sex and race strata. 1 SD of δNfLobs is 0.0665. All other SDs can be obtained from this table as sqrt(N) × SE to assess clinically meaningful effects.

BMI, weight status, and their longitudinal association with plasma NfL

Our main hypotheses of associations of BMI (and weight status) with time-dependent plasma NfL concentrations were examined by a series of mixed-effects linear regression models, with key findings presented in Table 2. Overall, baseline concentrations of plasma NfL were inversely associated with BMI (γ01 = −0.014 ± 0.002, P < 0.001) and higher weight status in both the reduced and full models. In contrast, BMI (γ11 = +0.0012 ± 0.0003, P < 0.001) and higher weight status at baseline were linked to faster increase in plasma NfL over time. Both associations were driven by the contrast between obesity and normal weight (γ01 = −0.234 ± 0.045, P < 0.001; γ11 = +0.017 ± 0.006, P < 0.010). The results were largely homogeneous across sex and race with few exceptions, particularly for the reduced model. When examining standardized regression coefficients (b), 1 SD increase in BMI was linked to a −0.19 SD lower baseline plasma NfL and with a 0.015-fold annual increase in SD of plasma NfL, yielding an increase of 0.15 SD over a period of 10 y. Both of these cross-sectional and longitudinal standardized effect sizes are considered weak to modest.

TABLE 2.

BMI and weight status (at v1) and their association with baseline plasma NfL and annualized change in plasma NfL between v1 and v3, overall and by sex and race: mixed-effects linear regression models; HANDLS, 2004–20171

| Overall (n = 608) | Women (n = 352) | Men (n = 256) | P sex 2 | White adults (n = 257) | African American adults (n = 351) | P race 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A | |||||||

| BMIv1, γ0a | −0.015 ± 0.002*** | −0.014 ± 0.003*** | −0.016 ± 0.005*** | 0.56 | −0.014 ± 0.004*** | −0.014 ± 0.003*** | 0.72 |

| BMIv1 × Time, γ1a | +0.0012 ± 0.0003*** | +0.0011 ± 0.0003*** | +0.0014 ± 0.0006** | 0.65 | +0.0007 ± 0.0005 | +0.0014 ± 0.0004*** | 0.21 |

| Model 2A | |||||||

| BMIv1, γ0a | −0.014 ± 0.002*** | −0.013 ± 0.003*** | −0.016 ± 0.005** | 0.58 | −0.014 ± 0.004*** | −0.013 ± 0.003*** | 0.81 |

| BMIv1 × Time, γ1a | +0.0012 ± 0.0003*** | +0.0012 ± 0.0003*** | +0.0014 ± 0.0006* | 0.60 | +0.0008 ± 0.005 | +0.0013 ± 0.0003*** | 0.15 |

| Model 1B | |||||||

| [Underweight vs. Normal], γ0a | +0.170 ± 0.103 | +0.176 ± 0.129 | +0.160 ± 0.165 | 1.00 | +0.343 ± 0.155* | +0.028 ± 0.137 | 0.10 |

| [Overweight vs. Normal], γ0a | −0.085 ± 0.047 | −0.025 ± 0.064 | −0.122 ± 0.071 | 0.27 | +0.034 ± 0.073 | −0.163 ± 0.052** | 0.054 |

| [Obese vs. Normal], γ0a | −0.245 ± 0.045*** | −0.223 ± 0.057*** | −0.245 ± 0.072** | 0.75 | −0.177 ± 0.069* | −0.281 ± 0.059*** | 0.16 |

| [Underweight vs. Normal] × Time, γ1a | −0.016 ± 0.013 | −0.003 ± 0.016 | −0.034 ± 0.022 | 0.23 | −0.015 ± 0.019 | −0.014 ± 0.018 | 0.91 |

| [Overweight vs. Normal] × Time, γ1a | +0.001 ± 0.006 | +0.009 ± 0.008 | +0.007 ± 0.010 | 0.89 | −0.002 ± 0.009 | +0.016 ± 0.008* | 0.15 |

| [Obese vs. Normal] × Time, γ1a | +0.017 ± 0.006** | +0.023 ± 0.007** | +0.010 ± 0.010 | 0.22 | +0.011 ± 0.009 | +0.022 ± 0.008** | 0.39 |

| Model 2B | |||||||

| [Underweight vs. Normal], γ0a | +0.138 ± 0.104 | +0.109 ± 0.127 | +0.163 ± 0.167 | 0.95 | +0.344 ± 0.155* | −0.020 ± 0.137 | 0.093 |

| [Overweight vs. Normal], γ0a | −0.077 ± 0.047 | −0.015 ± 0.062 | −0.115 ± 0.072 | 0.27 | +0.041 ± 0.073 | −0.156 ± 0.062* | 0.061 |

| [Obese vs. Normal], γ0a | −0.234 ± 0.045*** | −0.206 ± 0.056*** | −0.239 ± 0.074** | 0.70 | −0.171 ± 0.070* | −0.274 ± 0.060*** | 0.17 |

| [Underweight vs. Normal] × Time, γ1a | −0.018 ± 0.013 | −0.005 ± 0.016 | −0.036 ± 0.022 | 0.20 | −0.023 ± 0.019 | −0.011 ± 0.018 | 0.91 |

| [Overweight vs. Normal] × Time, γ1a | +0.009 ± 0.006 | +0.009 ± 0.008 | +0.006 ± 0.010 | 0.94 | −0.002 ± 0.009 | +0.015 ± 0.008 | 0.14 |

| [Obese vs. Normal] × Time, γ1a | +0.017 ± 0.006** | +0.0237 ± 0.007** | +0.008 ± 0.010 | 0.23 | +0.014 ± 0.009 | +0.020 ± 0.008* | 0.34 |

Values are fixed-effects γ ± SE. Models 1A and 1B included each of v1 BMI and weight status (z scored), separately as the main predictor for v1 NfL and NfL annualized rate of change over time, using a series of mixed-effects linear regression models, carried out in the overall population, and stratified by sex and by race, separately. These models adjusted only for age, sex, race, poverty status, educational attainment, and the inverse Mills ratio. Models 2A and 2B followed a similar approach but adjusted further for selected lifestyle and health-related factors, namely current drug use, current tobacco use, Healthy Eating Index-2010, total energy intake, and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression total score. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.010; ***P < 0.001 for null hypothesis that fixed effect γ = 0. HANDLS, Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span; NfL, neurofilament light chain; v1, visit 1; v3, visit 3.

Based on separate models testing the statistical significance for Sex × BMI/[weight status] and Sex × BMI/[weight status] × Time in models unstratified by sex or race in which these 2-way and 3-way interaction terms were included for each sociodemographic factor, separately.

Based on separate models testing the statistical significance for Race × BMI/[weight status] and Race × BMI/[weight status] × Time in models unstratified by sex or race in which these 2-way and 3-way interaction terms were included for each sociodemographic factor, separately.

ALtotal and ALcomp and their longitudinal association with plasma NfL

Following a similar modeling approach (Table 3), we examined the associations of ALtotal and ALcomp in relation to time-dependent change in plasma NfL. Overall, there was a clear association between ALtotal at v1 and faster increase in plasma NfL (P < 0.001) and the same exposure was associated with lower baseline plasma NfL (P < 0.05). Although largely homogeneous by sex and by race, this association differed markedly by these 2 sociodemographic groups when each component of AL was considered as the main exposure. One notable finding is that v1 HbA1c was consistently associated with higher plasma NfL at baseline and faster increase in plasma NfL among White adults in both the reduced and full models (P < 0.010 for HbA1c main effect and HbA1c × Time), with P = 0.007 for the HbA1c × Race parameter. Other notable findings included an inverse relation between v1 WHR and v1 plasma NfL among men, with the reverse found in women and among African American adults and no association detected among White adults. In contrast, inverse associations of v1 SBP and/or DBP with v1 plasma NfL were mostly detected among White adults. Moreover, v1 serum ALB was inversely linked with plasma NfL at v1 among men, an association not detected in women (P < 0.01 for ALB × sex).

TABLE 3.

ALtotal and ALcomp (at v1) and their association with baseline plasma NfL and annualized change in plasma NfL between v1 and v3, overall and by sex and race: mixed-effects linear regression models; HANDLS, 2004–20171

| Overall (n = 608) | Women (n = 352) | Men (n = 256) | P sex 2 | White adults (n = 257) | African American adults (n = 351) | P race 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A | |||||||

| ALtotal, γ0a | −0.038 ± 0.015* | −0.029 ± 0.019 | −0.039 ± 0.023 | 0.52 | −0.005 ± 0.023 | −0.057 ± 0.020** | 0.15 |

| ALtotal × Time, γ1a | +0.0066 ± 0.0018*** | +0.006 ± 0.002** | +0.008 ± 0.003* | 0.75 | +0.004 ± 0.003 | +0.008 ± 0.002** | 0.25 |

| Model 2A | |||||||

| ALtotal, γ0a | −0.033 ± 0.015* | −0.027 ± 0.018 | −0.037 ± 0.024 | 0.68 | −0.003 ± 0.023 | −0.050 ± 0.019* | 0.65 |

| ALtotal × Time, γ1a | +0.0067 ± 0.0018*** | +0.006 ± 0.002** | +0.008 ± 0.003* | 0.75 | +0.004 ± 0.003 | +0.008 ± 0.002** | 0.19 |

| Model 1B | |||||||

| WHR, γ0a | +0.053 ± 0.033 | +0.063 ± 0.030* | −1.247 ± 0.465** | <0.001 | +0.065 ± 0.032 | −1.047 ± 0.349** | 0.008 |

| WHR × Time, γ1a | +0.004 ± 0.004 | +0.003 ± 0.004 | +0.119 ± 0.062 | 0.066 | +0.0035 ± 0.0040 | +0.074 ± 0.045 | 0.084 |

| Model 2B | |||||||

| WHR, γ0a | +0.053 ± 0.032 | +0.064 ± 0.029* | −1.179 ± 0.474* | 0.001 | +0.064 ± 0.032 | −0.991 ± 0.345** | 0.008 |

| WHR × Time, γ1a | +0.005 ± 0.004 | +0.003 ± 0.004 | +0.112 ± 0.063 | 0.077 | +0.0034 ± 0.0039 | +0.0711 ± 0.044 | 0.064 |

| Model 1C | |||||||

| ALB, γ0a | −0.092 ± 0.064 | +0.045 ± 0.078 | −0.301 ± 0.106** | 0.004 | −0.064 ± 0.101 | −0.127 ± 0.083 | 0.90 |

| ALB × Time, γ1a | +0.014 ± 0.008 | +0.003 ± 0.010 | +0.029 ± 0.014* | 0.14 | +0.010 ± 0.012 | +0.017 ± 0.011 | 0.56 |

| Model 2C | |||||||

| ALB, γ0a | −0.107 ± 0.064 | +0.007 ± 0.077 | −0.303 ± 0.107** | 0.006 | −0.062 ± 0.102 | −0.146 ± 0.082 | 0.81 |

| ALB × Time, γ1a | +0.013 ± 0.008 | +0.003 ± 0.010 | +0.027 ± 0.014 | 0.17 | +0.007 ± 0.012 | +0.017 ± 0.011 | 0.46 |

| Model 1D4 | |||||||

| hsCRP, γ0a | −0.008 ± 0.008 | −0.015 ± 0.010 | +0.004 ± 0.014 | 0.19 | −0.010 ± 0.012 | −0.008 ± 0.011 | 0.90 |

| hsCRP × Time, γ1a | +0.004 ± 0.002* | +0.006 ± 0.002** | +0.001 ± 0.003 | 0.059 | +0.005 ± 0.003* | +0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.53 |

| Model 2D4 | |||||||

| hsCRP, γ0a | −0.008 ± 0.008 | −0.015 ± 0.010 | +0.003 ± 0.015 | 0.24 | −0.010 ± 0.013 | −0.018 ± 0.011 | 0.88 |

| hsCRP × Time, γ1a | +0.004 ± 0.002* | +0.006 ± 0.002** | +0.001 ± 0.003 | 0.074 | +0.005 ± 0.002* | +0.004 ± 0.002 | 0.54 |

| Model 1E | |||||||

| HbA1c, γ0a | +0.026 ± 0.019 | +0.032 ± 0.025 | +0.015 ± 0.028 | 0.78 | +0.080 ± 0.025** | −0.035 ± 0.027 | 0.007 |

| HbA1c × Time, γ1a | +0.0078 ± 0.0023** | +0.0098 ± 0.0052** | +0.0061 ± 0.0036 | 0.35 | +0.0084 ± 0.0030** | +0.0068 ± 0.0034* | 0.70 |

| Model 2E | |||||||

| HbA1c, γ0a | +0.030 ± 0.019 | +0.030 ± 0.024 | +0.021 ± 0.029 | 0.98 | +0.076 ± 0.025** | −0.024 ± 0.028 | 0.021 |

| HbA1c × Time, γ1a | +0.0076 ± 0.0023** | +0.0099 ± 0.0030** | +0.0055 ± 0.0037 | 0.30 | +0.0088 ± 0.0029** | +0.0051 ± 0.0035 | 0.60 |

| Model 1F | |||||||

| CHOL, γ0a | −0.0004 ± 0.0004 | +0.0001 ± 0.0005 | −0.0011 ± 0.0007 | 0.13 | −0.0004 ± 0.0006 | −0.0004 ± 0.0006 | 0.89 |

| CHOL × Time, γ1a | +0.00014 ± 0.00005** | +0.00006 ± 0.00006 | +0.00025 ± 0.00009** | 0.069 | +0.00016 ± 0.00007* | +0.00012 ± 0.00007 | 0.66 |

| Model 2F | |||||||

| CHOL, γ0a | −0.0004 ± 0.0004 | +0.0001 ± 0.0005 | −0.0011 ± 0.0007 | 0.17 | −0.0004 ± 0.0006 | −0.0004 ± 0.0006 | 0.87 |

| CHOL × Time, γ1a | +0.00014 ± 0.00005** | +0.00006 ± 0.00006 | +0.00026 ± 0.00009** | 0.060 | +0.00017 ± 0.00007* | +0.00014 ± 0.00007 | 0.69 |

| Model 1G | |||||||

| HDL-C, γ0a | +0.0034 ± 0.0010** | +0.0029 ± 0.0013* | +0.0037 ± 0.0017* | 0.35 | +0.0031 ± 0.0019 | +0.0034 ± 0.0012** | 0.88 |

| HDL-C × Time, γ1a | −0.00017 ± 0.00014 | −0.00030 ± 0.00016 | −0.00002 ± 0.00023 | 0.33 | −0.00010 ± 0.00024 | −0.00018 ± 0.00017 | 0.80 |

| Model 2G | |||||||

| HDL-C, γ0a | +0.0030 ± 0.0010** | +0.0025 ± 0.0013 | +0.0036 ± 0.0017* | 0.54 | +0.0030 ± 0.0019 | +0.0028 ± 0.0013* | 0.89 |

| HDL-C × Time, γ1a | −0.0002 ± 0.0001 | −0.00032 ± 0.00017 | −0.00001 ± 0.00024 | 0.31 | −0.00019 ± 0.00024 | −0.00013 ± 0.00017 | 0.81 |

| Model 1H | |||||||

| RHR, γ0a | −0.0017 ± 0.0015 | −0.0031 ± 0.0020 | −0.00043 ± 0.0024 | 0.43 | −0.00205 ± 0.00231 | −0.0018 ± 0.0020 | 0.99 |

| RHR × Time, γ1a | +0.00087 ± 0.00019*** | +0.00077 ± 0.00024** | +0.00096 ± 0.00031** | 0.60 | +0.00069 ± 0.00028* | +0.00100 ± 0.00026*** | 0.47 |

| Model 2H | |||||||

| RHR, γ0a | −0.0019 ± 0.0015 | −0.0029 ± 0.0019 | −0.0005 ± 0.0024 | 0.51 | −0.00213 ± 0.00230 | −0.0017 ± 0.0020 | 0.89 |

| RHR × Time, γ1a | +0.00087 ± 0.00019*** | +0.00081 ± 0.00024** | +0.00096 ± 0.00031** | 0.68 | +0.00062 ± 0.00028* | +0.0010 ± 0.0002*** | 0.46 |

| Model 1I | |||||||

| SBP, γ0a | −0.0033 ± 0.0011** | −0.0037 ± 0.0013** | −0.0023 ± 0.0019 | 0.67 | −0.0052 ± 0.0016** | −0.0013 ± 0.0016 | 0.023 |

| SBP × Time, γ1a | +0.00040 ± 0.00014** | +0.00019 ± 0.00016 | +0.00074 ± 0.00025** | 0.062 | +0.00024 ± 0.00019 | +0.00056 ± 0.00020** | 0.36 |

| Model 2I | |||||||

| SBP, γ0a | −0.0030 ± 0.0011** | −0.0035 ± 0.0013** | −0.0020 ± 0.0010 | 0.64 | −0.0049 ± 0.0016** | −0.0007 ± 0.0016 | 0.019 |

| SBP × Time, γ1a | +0.00039 ± 0.00014** | +0.0002 ± 0.0002 | +0.00070 ± 0.00026** | 0.063 | +0.00021 ± 0.00019 | +0.00053 ± 0.00020** | 0.27 |

| Model 1J | |||||||

| DBP, γ0a | −0.0052 ± 0.0017** | −0.0082 ± 0.0021*** | −0.0012 ± 0.0027 | 0.047 | −0.0104 ± 0.0026*** | −0.0015 ± 0.002 | 0.002 |

| DBP × Time, γ1a | +0.0005 ± 0.0002* | +0.0003 ± 0.0003 | +0.0007 ± 0.0003* | 0.32 | +0.0003 ± 0.0003 | +0.00063 ± 0.00027* | 0.50 |

| Model 2J | |||||||

| DBP, γ0a | −0.0045 ± 0.0017** | −0.0071 ± 0.0021** | −0.0010 ± 0.0027 | 0.069 | −0.0098 ± 0.0027*** | −0.0005 ± 0.0021 | 0.002 |

| DBP × Time, γ1a | +0.00048 ± 0.00021* | +0.00034 ± 0.00027 | +0.00068 ± 0.00034 | 0.32 | +0.0002 ± 0.0003 | +0.00056 ± 0.00028* | 0.38 |

Values are fixed effects γ ± SE. Models 1A–1J included each of v1 ALtotal and ALcomp, separately as the main predictor for v1 NfL and NfL annualized rate of change over time, using a series of mixed-effects linear regression models, carried out in the overall population, and stratified by sex and by race, separately. These models adjusted only for age, sex, race, poverty status, educational attainment, and the inverse Mills ratio. Models 2A–2J followed a similar approach but adjusted further for selected lifestyle and health-related factors, namely current drug use, current tobacco use, Healthy Eating Index-2010, total energy intake, and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression total score. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.010; ***P < 0.001 for null hypothesis that fixed effect γ = 0. ALB, albumin; ALcomp, allostatic load continuous components; ALtotal, allostatic load total score; CHOL, total cholesterol; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HANDLS, Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NfL, neurofilament light chain; RHR, resting heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; v1, visit 1; v3, visit 3; WHR, waist:hip ratio.

Based on separate models testing the statistical significance for Sex × AL and Sex × AL × Time in models unstratified by sex or race in which these 2-way and 3-way interaction terms were included for each sociodemographic factor, separately.

Based on separate models testing the statistical significance for Race × AL and Race × AL × Time in models unstratified by sex or race in which these 2-way and 3-way interaction terms were included for each sociodemographic factor, separately.

Loge transformed. All the continuous predictors, including main exposure variables, were centered at their respective means.

hsCRP, cholesterol, and RHR at v1 were among the ALcomp associated with faster increase in plasma NfL over time in the total sample, whereas they were uncorrelated with baseline plasma NfL. In contrast, SBP and DBP had different associations with baseline NfL compared with δNfL, suggesting that both measures were inversely related to first-visit NfL as well as being associated with faster increase in NfL over time. Finally, higher HDL cholesterol at v1 was associated with higher v1 plasma NfL, in the total sample.

ALtotal and ALcomp as a mediator between BMI and annualized change in plasma NfL

Figure 2 shows the results from a structural equations model in which ALtotal at v1 was tested as a potential mediator between BMI at v1 and annualized change in plasma NfL. Our results suggested that the TE of BMI at v1 on δNfLobs indicated a positive association between the 2 factors in the total sample (TE >0, P < 0.05). This was also the case among women. However, only among women the indirect effect (IE) indicated a large portion of this TE was mediated through ALtotal, with an estimated mediation proportion of 30% (TE = +0.0014 ± 0.00038, P < 0.001; IE = +0.00042 ± 0.00019, P = 0.025). In other groups and overall, TE was statistically significant mostly as a direct effect (DE) and there was no significant IE through ALtotal. Specifically, among African American adults, most of the TE was a DE (TE = +0.0011 ± 0.0004, P = 0.015; DE = +0.0010 ± 0.00048, P = 0.034).

FIGURE 2.

BMI at v1 → AL at v1 → δNfLobs, overall and by sex and race: structural equations model; HANDLS (Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span), 2004–2017. Values are unstandardized path coefficients α ± SE, TEs, direct effects, and IEs with associated P values. See Table 4 for sample sizes, overall and by strata. Exogenous variables in the models were age, sex, race, poverty status, educational attainment, current drug use, current tobacco use, Healthy Eating Index-2010, total energy intake, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression total score, and the inverse Mills ratio. 1P value associated with null hypothesis of no difference in path coefficient α, by sex, using the Wald test (χ2 test, 1 df) for group invariance. 2P value associated with null hypothesis of no difference in path coefficient α, by race, using the Wald test (χ2 test, 1 df) for group invariance. *AL, allostatic load; IE, indirect effect; TE, total effect; v1, visit 1; δNfLobs, observed annualized rate of change in plasma neurofilament light chain between visit 1 and visit 3.

ALcomp as mediators between ALtotal and annualized change in plasma NfL

Table 4 presents results from the structural equation model testing DEs and IEs of ALtotal on δNfLobs through alternative ALcomp, while stratifying by sex and by race groups. Focusing on models with significant TEs, the IE was statistically significant only for HbA1c as the primary mediating factor in the total sample (IE = +0.0031 ± 0.0012, P < 0.05; TE = +0.0062 ± 0.0023, P < 0.05; mediation proportion: 50%). Most other models with significant TEs (e.g., WHR, hsCRP, total cholesterol, SBP, DBP) of ALtotal on δNfLobs indicated that another pathway was at play not including each of those ALcomp.

TABLE 4.

ALtotal (at v1) → ALcomp (at v1) → δNfLobs, overall and by sex and race: structural equations model; HANDLS, 2004–20171

| Overall (n = 606) | Women (n = 351) | Men (n = 255) | P sex 2 | White adults (n = 255) | African American adults (n = 351) | P race 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHR | |||||||

| ALtotal→WHR | +0.0411 ± 0.0185* | +0.0560 ± 0.0333 | +0.0273 ± 0.0027*** | 0.39 | +0.0600 ± 0.0439 | +0.0277 ± 0.0026*** | 0.46 |

| WHR→δNfLobs | +0.0054 ± 0.0051 | +0.0038 ± 0.0045 | +0.1989 ± 0.0908* | 0.032 | +0.0045 ± 0.0054 | +0.0848 ± 0.0592 | 0.18 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobs | +0.0059 ± 0.0023* | +0.0098 ± 0.0028*** | −0.0037 ± 0.0046 | 0.012 | +0.0089 ± 0.0038* | +0.0013 ± 0.0033 | 0.13 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023** | +0.0101 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0018 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038* | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | +0.0002 ± 0.0002 | +0.0002 ± 0.0003 | +0.0054 ± 0.0025* | — | +0.0003 ± 0.0004 | +0.0023 ± 0.0017 | — |

| ALB | |||||||

| ALtotal→ALB | −0.0368 ± 0.0093*** | −0.0488 ± 0.0126*** | −0.0179 ± 0.0138 | 0.099 | −0.0391 ± 0.0140** | −0.0394 ± 0.0126** | 0.99 |

| ALB→δNfLobs | −0.0034 ± 0.0101 | −0.0057 ± 0.0118 | +0.0098 ± 0.0178 | 0.47 | −0.0311 ± 0.0169 | +0.0140 ± 0.0124 | 0.031 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobs | +0.0060 ± 0.0023* | +0.0098 ± 0.0029** | +0.0019 ± 0.0040 | 0.11 | +0.0079 ± 0.0038* | +0.0041 ± 0.0030 | 0.43 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023 | +0.0101 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0018 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038* | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | +0.0001 ± 0.0004 | +0.0003 ± 0.0006 | −0.0002 ± 0.0003 | — | +0.0012 ± 0.0008 | −0.0006 ± 0.0005 | — |

| hsCRP4 | |||||||

| ALtotal→hsCRP | +0.5602 ± 0.0400*** | +0.6194 ± 0.0534*** | +0.4928 ± 0.0611*** | 0.12 | +0.5687 ± 0.0524*** | +0.5377 ± 0.0580*** | 0.69 |

| hsCRP→δNfLobs | −0.0009 ± 0.0024 | +0.0018 ± 0.0028 | −0.0055 ± 0.0040 | 0.13 | −0.0011 ± 0.0045 | −0.001 ± 0.0027 | 0.98 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobs | +0.0067 ± 0.0027* | +0.0090 ± 0.0033** | +0.0045 ± 0.0044 | 0.41 | +0.0098 ± 0.0046* | +0.0041 ± 0.0033 | 0.31 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023** | +0.0101 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0017 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038 | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | −0.0005 ± 0.0013 | +0.0011 ± 0.0017 | −0.0027 ± 0.0020 | — | −0.0006 ± 0.0026 | −0.0005 ± 0.0014 | — |

| HbA1c | |||||||

| ALtotal→HbA1c | +0.3657 ± 0.0285*** | +0.3922 ± 0.0347*** | +0.3544 ± 0.0479*** | 0.52 | +0.4169 ± 0.0490*** | +0.3200 ± 0.0338*** | 0.10 |

| HbA1c→δNfLobs | +0.0085 ± 0.0033** | +0.0072 ± 0.0043 | +0.0098 ± 0.0051 | 0.71 | +0.0074 ± 0.0048 | +0.0095 ± 0.0046* | 0.76 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobs | +0.0030 ± 0.0026 | +0.0073 ± 0.0032* | −0.0017 ± 0.0043 | 0.10 | +0.0061 ± 0.0043 | +0.0006 ± 0.0033 | 0.31 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023* | +0.0101 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0018 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038 | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | +0.0031 ± 0.0012* | +0.0028 ± 0.0017 | +0.0035 ± 0.0019 | — | +0.0031 ± 0.0020 | +0.0030 ± 0.0015* | — |

| CHOL | |||||||

| ALtotal→CHOL | +4.555 ± 1.4354** | +2.4277 ± 1.9497 | +7.4950 ± 2.1194*** | 0.079 | +5.8848 ± 2.3200* | +3.8843 ± 1.8562* | 0.50 |

| CHOL→δNfLobs | +0.0000 ± 0.0001 | +0.0000 ± 0.0001 | +0.0000 ± 0.0001 | 0.86 | −0.0001 ± 0.0001 | +0.0001 ± 0.0001 | 0.23 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobs | +0.0061 ± 0.0023** | +0.0100 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0016 ± 0.0040 | 0.088 | +0.0095 ± 0.0038* | +0.0032 ± 0.0029 | 0.19 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023** | +0.0101 ± 0.0028 | +0.0017 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038 | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | +0.0001 ± 0.0003 | +0.0001 ± 0.0002 | +0.0002 ± 0.0009 | — | −0.0003 ± 0.0006 | +0.0004 ± 0.0004 | — |

| HDL-C | |||||||

| ALtotal→HDL-C | −5.7701 ± 0.5346*** | −5.3073 ± 0.7133*** | −6.0073 ± 0.8018*** | 0.51 | −4.9331 ± 0.6840 | −6.2943 ± 0.7649 | 0.18 |

| HDL-C→δNfLobs | −0.0001 ± 0.0002 | −0.0001 ± 0.0002 | −0.0001 ± 0.0003 | 0.96 | −0.0002 ± 0.0003 | +0.0000 ± 0.0002 | 0.35 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobs | +0.0058 ± 0.0025* | +0.0097 ± 0.0030** | +0.0014 ± 0.0044 | 0.12 | +0.0084 ± 0.0042* | +0.0035 ± 0.0032 | 0.72 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023 | +0.0101 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0017 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038 | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | +0.0004 ± 0.0010 | +0.0004 ± 0.0011 | +0.0004 ± 0.0019 | — | +0.0008 ± 0.0017 | +0.0001 ± 0.0013 | — |

| RHR | |||||||

| ALtotal→RHR | +2.7833 ± 0.3786*** | +2.7503 ± 0.4903*** | +3.1124 ± 0.5822*** | 0.63 | +3.0838 ± 0.5950*** | +2.7980 ± 0.4917*** | 0.71 |

| RHR→δNfLobs | +0.0003 ± 0.0002 | +0.0003 ± 0.0003 | +0.0004 ± 0.0004 | 0.85 | +0.0001 ± 0.0004 | +0.0005 ± 0.0003 | 0.48 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobs | +0.0052 ± 0.0024* | +0.0093 ± 0.0029** | +0.0005 ± 0.0042 | 0.085 | +0.0088 ± 0.0040* | +0.0022 ± 0.0030 | 0.19 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023** | +0.0101 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0018 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038* | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | +0.0010 ± 0.0007 | +0.0008 ± 0.0008 | +0.0012 ± 0.0013 | — | +0.0004 ± 0.0012 | +0.0014 ± 0.0009 | — |

| SBP | |||||||

| ALtotal→SBP | +5.5879 ± 0.4957*** | +6.0208 ± 0.6872*** | +4.8958 ± 0.7195*** | 0.26 | +6.0278 ± 0.8259*** | +5.2905 ± 0.6207*** | 0.48 |

| SBP→δNfLobs | +0.0045 ± 0.0025 | +0.0002 ± 0.0002 | +0.0004 ± 0.0003 | 0.54 | +0.0003 ± 0.0003 | +0.0003 ± 0.0003 | 0.91 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobss | +0.0003 ± 0.0002 | +0.0091 ± 0.0031** | −0.0003 ± 0.0043 | 0.076 | +0.0076 ± 0.0042 | +0.0020 ± 0.0032 | 0.28 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023* | +0.0101 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0017 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038* | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | +0.0016 ± 0.0011 | +0.0010 ± 0.0013 | +0.0020 ± 0.0017 | — | +0.0016 ± 0.0017 | +0.0016 ± 0.0013 | — |

| DBP | |||||||

| ALtotal→DBP | +3.1337 ± 0.3384*** | +3.2288 ± 0.4412*** | +2.9112 ± 0.5342*** | 0.65 | +2.7516 ± 0.5047*** | +3.4213 ± 0.4603*** | 0.33 |

| DBP→δNfLobs | +0.0001 ± 0.0003 | −0.0001 ± 0.0003 | +0.0003 ± 0.0005 | 0.41 | +0.0000 ± 0.0005 | +0.0001 ± 0.0003 | 0.90 |

| ALtotal→ δNfLobs | +0.0059 ± 0.0025* | +0.0105 ± 0.0030*** | +0.0008 ± 0.0042 | 0.057 | +0.0091 ± 0.0040* | +0.0032 ± 0.0031 | 0.25 |

| TE (ALtotal) | +0.0062 ± 0.0023** | +0.0101 ± 0.0028*** | +0.0017 ± 0.0040 | — | +0.0092 ± 0.0038* | +0.0036 ± 0.0029 | — |

| IE (ALtotal) | +0.0003 ± 0.0009 | −0.0004 ± 0.0011 | +0.0010 ± 0.0014 | — | +0.0001 ± 0.0013 | +0.0004 ± 0.0012 | — |

Exogenous variables in the models were age, sex, race, poverty status, educational attainment, current drug use, current tobacco use, Healthy Eating Index-2010, total energy intake, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression total score, and the inverse Mills ratio. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.010; ***P < 0.001 for null hypothesis that path coefficient α = 0. ALB, albumin; ALcomp, allostatic load continuous components; ALtotal, allostatic load total score; CHOL, total cholesterol; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HANDLS, Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IE, indirect effect; RHR, resting heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TE, total effect; v1, visit 1; WHR, waist:hip ratio; δNfLobs, annualized rate of change in plasma neurofilament light chain between visit 1 and visit 3.

P value associated with null hypothesis of no difference in path coefficient α, by sex, using the Wald test (χ2 test, 1 df) for group invariance.

P value associated with null hypothesis of no difference in path coefficient α, by race, using the Wald test (χ2 test, 1 df) for group invariance.

Loge transformed.

Supplemental Table 2 tests similar mediating effects but replacing ALtotal with ALcomp while examining them overall and by race and sex. The results indicate that HbA1c, overall and among women, is also among the main mediators in the relation between BMI and δNfLobs, as was the case for the ALtotal–δNfLobs association. Specifically, a TE of +0.00140 ± 0.0004 (P < 0.001) was detected among women, of which +0.00023 ± 0.00011 (P = 0.028) was explained by the IE of HbA1c at baseline (or a mediation proportion of 16.4%). A similar pattern was observed overall with a mediation proportion ∼19%. There were no significant IEs of HbA1c detected among men, white, or African American adults in the association between BMI and δNfLobs.

Discussion

This study is the first that we know of to examine associations comprehensively and longitudinally between cardiometabolic risk factors and plasma NfL, particularly in a racially diverse community-based sample of middle-aged urban adults. Among our key findings, BMI and ALtotal were associated with lower initial but faster increase in plasma NfL over time. hsCRP, serum total cholesterol, and RHR at v1 were linked with faster increase in plasma NfL over time overall. In SM analyses, the association of BMI with δNfL was significantly mediated through ALtotal among women and overall was mediated through HbA1c concentrations.

Previous studies

Plasma NfL and its association with neurocognitive outcomes

NfL has been posited as a biomarker of neuronal injury and recently the development of sensitive and accurate methods to measure plasma NfL has led to the examination of whether this noninvasive biomarker may be an indicator of neurodegeneration. Cross-sectional studies have reported that plasma NfL is elevated in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD and that these concentrations correlate with other neurocognitive measures (15). Individuals with mild cognitive impairment or with AD dementia had higher baseline plasma NfL and longitudinal analyses showed faster rates of NfL were correlated with rates of cognitive and imaging measures as well as CSF biomarker concentrations (2). In fact, serum/plasma NfL predicts future development of sporadic and familial AD and is associated with faster cognitive decline and also with brain structure alterations (3, 4, 40, 42). However, plasma NfL was associated with changes in brain white matter and AD but not with preclinical phases of AD in another study (43). In nondemented adults, plasma NfL also was associated with cognitive decline (45, 61). These data are indicative that plasma NfL may have value in monitoring neurodegenerative disease progression. Furthermore, these studies point to plasma NfL as an easily accessible biomarker that shows promise for delineating early neurodegeneration in the presymptomatic stages of AD.

Cardiometabolic risk and its association with neurocognitive outcomes

The association of obesity and other cardiometabolic factors with dementia is complex. These complexities lie in when during the life span these factors are considered and the fact that they are often accompanied by a myriad of risk factors. For example, midlife obesity is associated with a significant risk of dementia and structural brain changes (27, 32). However, closer in time to the onset of disease (∼5–10 y) low BMI is associated with increased dementia risk, possibly owing to behavioral changes that accompany dementia including reduced physical activity and caloric intake (62, 63). Our data agree with the association of midlife obesity with dementia risk because BMI was associated with a faster increase of plasma NfL over time. ALtotal was also associated with a faster increase in plasma NfL over time, indicating that other cardiometabolic risk factors may also influence dementia risk. Cardiovascular disease risk factors including hsCRP, serum total cholesterol, and RHR at v1 were components of ALtotal that were linked to higher NfL longitudinally. Vascular disorders, such as hypertension, also have complex risk associations with dementia. Evidence indicates that hypertension at midlife increases risk of dementia but is protective or not a significant risk factor for the elderly (>80 y old) (31, 33, 64). Taken together, modifiable cardiometabolic risk factors at midlife may have long-term consequences that affect dementia risk and may be amenable to interventions for at-risk populations.

Cardiometabolic risk, adiposity, and their association with plasma NfL

Plasma NfL and CSF NfL concentrations increase with age. Aging is associated with chronic health conditions, in particular cardiometabolic risk. Therefore, cardiometabolic risk and other age-associated disease processes may be potential explanations for the observed increases in NfL over the lifetime. Despite this, few studies have examined cardiometabolic risk factors and plasma NfL and findings are contrary to expectations, which demonstrates the need for further research. For instance, recent studies suggest that there is an inverse relation between BMI and plasma NfL in healthy samples (17) and several clinical samples, including individuals with type 2 diabetes (18), multiple sclerosis (17), and women with anorexia (65, 66). However, a few studies found no relation between BMI and plasma NfL in healthy controls (18, 66). Furthermore, 1 study examining renal function, another aspect of cardiometabolic risk, found a significant, positive correlation between serum creatinine concentrations and plasma NfL in nondemented samples aged 60 y or older in both healthy controls and patients with diabetes (18). Finally, another study examining glucose metabolism, yet another aspect of cardiometabolic risk, found that, in patients with type 1 diabetes, those with more frequent and severe hypoglycemic episodes had significantly higher plasma NfL than did those with less frequent and less severe hypoglycemic episodes (67). Notably, the plasma NfL concentrations did not differ between healthy controls and patients with type 1 diabetes who had fewer and less severe hypoglycemic episodes. This, in tandem with the fact that both type 1 diabetes groups showed no differences in their cardiometabolic profiles, suggests that hypoglycemia, in particular, is associated with plasma NfL, which may indicate neuronal damage.

Given the paucity of research in cardiometabolic risk and NfL, several of our study findings are novel. Our findings indicate that AL mediates the association between BMI and the rate of change in plasma NfL only among women. Thus, plasma NfL increase over time is determined by BMI in women, a relation largely explained by the multimorbidity index of ALtotal, reflecting cardiometabolic risk. In contrast, among African American adults, the putative effect of BMI on rate of change in plasma NfL is largely a DE perhaps explained by other factors associated with global adiposity that are not part of the multimorbidity index of ALtotal. Sex and race differences in mediating effects of ALtotal in the BMI–δNfLobs relation may be explained by the possible inadequacy of the summary score of AL in some subgroups as opposed to the ALcomp. Our additional analyses indicated that, overall, HbA1c is the most likely mediator in the relation between BMI and change in plasma NfL over time, given the observed significant TEs and IEs, suggesting that the adverse potential effect of BMI on NfL over time is at least in part explained by co-occurrence of an elevated HbA1c with elevated BMI.

Moreover, HbA1c was the component of AL that explained its TE on rate of change in NfL reflecting glucose metabolism disorders. This ALcomp consistently explained the association overall between BMI and rate of change in NfL, with the mediation mostly detected among women. Finally, measures of inflammation, lipid metabolism, and hemodynamics were all related to increased plasma NfL over time in the total sample, without affecting baseline values of plasma NfL. This was not the case for SBP and DBP, which were associated with lower NfL at first visit, as well as having a direct relation with increase in NfL over time. This suggests that in this population of urban middle-aged adults, these 3 components of AL may have utility in predicting the pace of increase in plasma NfL over time, independently of its initial value.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several notable strengths. First, this study has included adequate numbers of African American adults to power subset analysis, which is critical for the field to move forward and examine the differential risk of dementia among African American adults. As far as we know, it is the first study to examine these important research questions on the association between cardiometabolic risk and plasma NfL. This suggests cardiometabolic risk may be important to consider when examining the clinical utility of plasma NfL for predicting neurocognitive outcomes. In addition, plasma NfL may be on a pathway through which cardiometabolic risk can influence neurocognitive outcomes. Second, we ascertained temporality of association with a longitudinal study design examining baseline exposures against change in outcomes over time. Third, the sample size is large and adequately powered to test those associations across sex and race groups. Fourth, advanced statistical techniques were used, including multiple linear mixed-effects regression and structural equation models, to test those associations and their heterogeneity across sex and race, while adjusting for key potential confounders and for sample selectivity using 2-stage Heckman selection.

Nevertheless, our study has ≥1 notable limitation, which is the relatively young age of our sample, leading to a low baseline plasma NfL compared with previous studies with older participants. Thus, the rate of increase in plasma NfL may have occurred at a slower pace than in older adults. Many studies have indicated that increased risk of adverse cognitive outcomes later in life is a function of cardiometabolic and related lifestyle risk factors at midlife (27, 28). Therefore, our study shows that a midlife putative marker of neurodegeneration may in fact be longitudinally associated with cardiometabolic risk among middle-aged adults.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report an association between cardiometabolic risk and an increase over time in plasma NfL. The association of BMI with δNfL was mediated through ALtotal in women and was mainly explained by elevations in HbA1c. Given that NfL may be a pathway through which cardiometabolic risk can lead to neurodegeneration, prevention efforts aimed at reducing plasma NfL should target cardiometabolic risk factors, particularly reduction of HbA1c concentrations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms. Nicolle Mode, Laboratory of Epidemiology and Population Sciences, Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging, NIH, for her contribution in selecting participants for plasma NfL analyses and related data management. We also thank all HANDLS participants, staff, and investigators, as well as internal reviewers of the manuscript at National Institute on Aging/NIH/Intramural Research Program. The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—MAB: conceived the study, managed the data, completed all the statistical analyses, had full access to the data used in this manuscript, and wrote up the manuscript; MAB, NNH, AIM, HAB, and ABZ: planned the analysis; MAB, NNH, AIM, HAB, and JW: performed the literature search and review; NNH, MKE, and ABZ: acquired the data; NNH, AIM, HAB, JW, MKE, and ABZ: wrote up parts of the manuscript; AIM: assisted with statistical methods; JW: assisted with statistical analysis; and all authors: revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Notes

Supported in part by Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging, NIH project number ZIA–AG000513 (to MKE and ABZ).

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, the Defense Health Agency, Department of Defense, or the US Government. Reference to any commercial products within this publication does not create or imply any endorsement by Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, the Defense Health Agency, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Supplemental Methods 1–3, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, and Supplemental Figure 1 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/jn/.

MKE and ABZ contributed equally to this work as senior authors.

Abbreviations used: AD, Alzheimer disease; AL, allostatic load; ALB, albumin; ALcomp, allostatic load continuous components; ALtotal, allostatic load total score; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DE, direct effect; HANDLS, Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HEI-2010, Healthy Eating Index 2010; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IE, indirect effect; IMR, inverse Mills ratio; MRV, Medical Research Vehicle; NfL, neurofilament light chain; RHR, resting heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SM, structural equations modeling; TE, total effect; v1, visit 1; v2, visit 2; v3, visit 3; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; δNfL, annualized change in NfL; δNfLobs, observed annualized neurofilament light chain change.

Contributor Information

May A Beydoun, Laboratory of Epidemiology and Population Sciences, National Institute on Aging/NIH/Intramural Research Program, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Nicole Noren Hooten, Laboratory of Epidemiology and Population Sciences, National Institute on Aging/NIH/Intramural Research Program, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Ana I Maldonado, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Catonsville, MD, USA.

Hind A Beydoun, Department of Research Programs, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, Fort Belvoir, VA, USA.

Jordan Weiss, Department of Demography, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Michele K Evans, Laboratory of Epidemiology and Population Sciences, National Institute on Aging/NIH/Intramural Research Program, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Alan B Zonderman, Laboratory of Epidemiology and Population Sciences, National Institute on Aging/NIH/Intramural Research Program, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Data Availability

Upon request, data can be made available to researchers with approved proposals, after they have agreed to confidentiality as required by our Institutional Review Board. Policies are publicized on https://handls.nih.gov. Data access requests can be sent to principal investigators (PIs) or the study manager, Jennifer Norbeck, at norbeckje@mail.nih.gov. These data are owned by the National Institute on Aging at the NIH. The PIs have made those data restricted to the public for 2 main reasons: “(1) The study collects medical, psychological, cognitive, and psychosocial information on racial and poverty differences that could be misconstrued or willfully manipulated to promote racial discrimination; and (2) Although the sample is fairly large, there are sufficient identifiers that the PIs cannot guarantee absolute confidentiality for every participant as we have stated in acquiring our confidentiality certificate.” Code book and statistical analysis script can be readily obtained from the corresponding author, upon request, by E-mail contact at baydounm@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1. Zhao Y, Xin Y, Meng S, He Z, Hu W. Neurofilament light chain protein in neurodegenerative dementia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;102:123–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mattsson N, Cullen NC, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Association between longitudinal plasma neurofilament light and neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(7):791–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Preische O, Schultz SA, Apel A, Kuhle J, Kaeser SA, Barro C, Graber S, Kuder-Buletta E, LaFougere C, Laske C et al. Serum neurofilament dynamics predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in presymptomatic Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2019;25(2):277–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weston PSJ, Poole T, O'Connor A, Heslegrave A, Ryan NS, Liang Y, Druyeh R, Mead S, Blennow K, Schott JM et al. Longitudinal measurement of serum neurofilament light in presymptomatic familial Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scherling CS, Hall T, Berisha F, Klepac K, Karydas A, Coppola G, Kramer JH, Rabinovici G, Ahlijanian M, Miller BC et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament concentration reflects disease severity in frontotemporal degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(1):116–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teunissen CE, Dijkstra C, Polman C. Biological markers in CSF and blood for axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(1):32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shahim P, Gren M, Liman V, Andreasson U, Norgren N, Tegner Y, Mattsson N, Andreasen N, Ost M, Zetterberg H et al. Serum neurofilament light protein predicts clinical outcome in traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):36791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khalil M, Teunissen CE, Otto M, Piehl F, Sormani MP, Gattringer T, Barro C, Kappos L, Comabella M, Fazekas F et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(10):577–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beydoun MA, Noren Hooten N, Beydoun HA, Maldonado AI, Weiss J, Evans MK, Zonderman AB. Plasma neurofilament light as a potential biomarker for cognitive decline in a longitudinal study of middle-aged urban adults. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. He L, Morley JE, Aggarwal G, Nguyen AD, Vellas B, de Souto Barreto P, MAPT/DSA Group . Plasma neurofilament light chain is associated with cognitive decline in non-dementia older adults. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weston PSJ, Poole T, Ryan NS, Nair A, Liang Y, Macpherson K, Druyeh R, Malone IB, Ahsan RL, Pemberton H et al. Serum neurofilament light in familial Alzheimer disease: a marker of early neurodegeneration. Neurology. 2017;89(21):2167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sanchez-Valle R, Heslegrave A, Foiani MS, Bosch B, Antonell A, Balasa M, Llado A, Zetterberg H, Fox NC. Serum neurofilament light levels correlate with severity measures and neurodegeneration markers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raket LL, Kühnel L, Schmidt E, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Mattsson-Carlgren N. Utility of plasma neurofilament light and total tau for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hansson O, Janelidze S, Hall S, Magdalinou N, Lees AJ, Andreasson U, Norgren N, Linder J, Forsgren L, Constantinescu R et al. Blood-based NfL: a biomarker for differential diagnosis of parkinsonian disorder. Neurology. 2017;88(10):930–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging I. Association of plasma neurofilament light with neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(5):557–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jin M, Cao L, Dai Y-p. Role of neurofilament light chain as a potential biomarker for Alzheimer's disease: a correlative meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Manouchehrinia A, Piehl F, Hillert J, Kuhle J, Alfredsson L, Olsson T, Kockum I. Confounding effect of blood volume and body mass index on blood neurofilament light chain levels. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(1):139–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Akamine S, Marutani N, Kanayama D, Gotoh S, Maruyama R, Yanagida K, Sakagami Y, Mori K, Adachi H, Kozawa J et al. Renal function is associated with blood neurofilament light chain level in older adults. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Artegoitia VM, Krishnan S, Bonnel EL, Stephensen CB, Keim NL, Newman JW. Healthy eating index patterns in adults by sex and age predict cardiometabolic risk factors in a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2021;7(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mousavi SM, Milajerdi A, Pouraram H, Saadatnia M, Shakeri F, Keshteli AH, Tan SC, Esmaillzadeh A. Adherence to Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI-2010) is not associated with risk of stroke in Iranian adults: a case-control study. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2021;91(1–2):48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sullivan VK, Petersen KS, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Eren F, Cassens ME, Bunczek MT, Kris-Etherton PM. Greater scores for dietary fat and grain quality components underlie higher total Healthy Eating Index-2015 scores, while whole fruits, seafood, and plant proteins are most favorably associated with cardiometabolic health in US adults. Curr Dev Nutr. 2021;5(3):nzab015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Millar SR, Navarro P, Harrington JM, Perry IJ, Phillips CM. Dietary quality determined by the Healthy Eating Index-2015 and biomarkers of chronic low-grade inflammation: a cross-sectional analysis in middle-to-older aged adults. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lim CGY, Whitton C, Rebello SA, van Dam RM. Diet quality and lower refined grain consumption are associated with less weight gain in a multi-ethnic Asian adult population. J Nutr. 2021;151(8):2372–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fanelli Kuczmarski M, Hossain S, Beydoun MA, Maldonando A, Evans MK, Zonderman AB. Association of DASH and depressive symptoms with BMI over adulthood in racially and socioeconomically diverse adults examined in the HANDLS Study. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States—gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29(1):6–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Min J, Xue H, Kaminsky LA, Cheskin LJ. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(3):810–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Wang Y. Obesity and central obesity as risk factors for incident dementia and its subtypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2008;9(3):204–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beydoun MA, Kivimaki M. Midlife obesity, related behavioral factors, and the risk of dementia in later life. Neurology. 2020;94(2):53–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gottesman RF, Albert MS, Alonso A, Coker LH, Coresh J, Davis SM, Deal JA, McKhann GM, Mosley TH, Sharrett AR et al. Associations between midlife vascular risk factors and 25-year incident dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Atti AR, Valente S, Iodice A, Caramella I, Ferrari B, Albert U, Mandelli L, De Ronchi D. Metabolic syndrome, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(6):625–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Legdeur N, van der Lee SJ, de Wilde M, van der Lei J, Muller M, Maier AB, Visser PJ. The association of vascular disorders with incident dementia in different age groups. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Driscoll I, Beydoun MA, An Y, Davatzikos C, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Midlife obesity and trajectories of brain volume changes in older adults. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(9):2204–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. de la Torre J. The vascular hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: a key to preclinical prediction of dementia using neuroimaging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(1):35–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gomez G, Beason-Held LL, Bilgel M, An Y, Wong DF, Studenski S, Ferrucci L, Resnick SM. Metabolic syndrome and amyloid accumulation in the aging brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;65(2):629–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li D, Hagen C, Fett AR, Bui HH, Knopman D, Vemuri P, Machulda MM, Jack CR Jr, Petersen RC, Mielke MM. Longitudinal association between phosphatidylcholines, neuroimaging measures of Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology, and cognition in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;79:43–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spinelli M, Fusco S, Grassi C. Brain insulin resistance and hippocampal plasticity: mechanisms and biomarkers of cognitive decline. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Suzuki H, Venkataraman AV, Bai W, Guitton F, Guo Y, Dehghan A, Matthews PM. Associations of regional brain structural differences with aging, modifiable risk factors for dementia, and cognitive performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1917257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Van Etten EJ, Bharadwaj PK, Nguyen LA, Hishaw GA, Trouard TP, Alexander GE. Right hippocampal volume mediation of subjective memory complaints differs by hypertension status in healthy aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;94:271–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sánchez-Benavides G, Suárez-Calvet M, Milà-Alomà M, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Grau-Rivera O, Operto G, Gispert JD, Vilor-Tejedor N, Sala-Vila A, Crous-Bou M et al. Amyloid-β positive individuals with subjective cognitive decline present increased CSF neurofilament light levels that relates to lower hippocampal volume. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;104:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. de Wolf F, Ghanbari M, Licher S, McRae-McKee K, Gras L, Weverling GJ, Wermeling P, Sedaghat S, Ikram MK, Waziry R et al. Plasma tau, neurofilament light chain and amyloid-β levels and risk of dementia; a population-based cohort study. Brain. 2020;143(4):1220–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Olsson B, Portelius E, Cullen NC, Sandelius Å, Zetterberg H, Andreasson U, Höglund K, Irwin DJ, Grossman M, Weintraub D et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein levels with cognition in patients with dementia, motor neuron disease, and movement disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(3):318–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rajan KB, Aggarwal NT, McAninch EA, Weuve J, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, DeCarli C, Evans DA. Remote blood biomarkers of longitudinal cognitive outcomes in a population study. Ann Neurol. 2020;88(6):1065–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]