Abstract

The cornea is an excellent model tissue to study how cells adapt to periods of hypoxia as it is naturally exposed to diurnal fluxes in oxygen. It is avascular, transparent, and highly innervated. In certain pathologies, such as diabetes, limbal stem cell deficiency, or trauma, the cornea may be exposed to hypoxia for variable lengths of time. Due to its avascularity, the cornea requires atmospheric oxygen, and a reduction in oxygen availability can impair its physiology and function. We hypothesize that hypoxia alters membrane stiffness and the deposition of matrix proteins, leading to changes in cell migration, focal adhesion formation, and wound repair. Two systems—a 3D corneal organ culture model and polyacrylamide substrates of varying stiffness—were used to examine the response of corneal epithelium to normoxic and hypoxic environments. Exposure to hypoxia alters the deposition of the matrix proteins such as laminin and Type IV collagen. In addition, previous studies had shown a change in fibronectin after injury. Studies performed on matrix-coated acrylamide substrates ranging from 0.2 to 50 kPa revealed stiffness-dependent changes in cell morphology. The localization, number, and length of paxillin pY118- and vinculin pY1065-containing focal adhesions were different in wounded corneas and in human corneal epithelial cells incubated in hypoxic environments. Overall, these results demonstrate that low-oxygenated environments modify the composition of the extracellular matrix, basal lamina stiffness, and focal adhesion dynamics, leading to alterations in the function of the cornea.

Keywords: hypoxia, extracellular matrix, cornea, focal adhesions, epithelium

INTRODUCTION

The cornea is an excellent model tissue to study how cells and organs adapt to hypoxia because it is exposed to fluxes in oxygen levels on a diurnal basis. The avascular healthy cornea is exposed to a 21% oxygenated environment in waking hours, which is reduced to 8% oxygen during the sleep cycle. The cornea adapts quickly and the corneal swelling that occurs during sleep returns to normal levels within an hour of eyelid opening. These daily changes have led many to speculate that the rapid eye movements and occasional eye opening during sleep cycles are sufficient to achieve homeostatic regulation (Morgan et al., 2010).

Another time when the cornea is naturally exposed to fluxes in environmental oxygen is during development. The changes in oxygenation occur before and after eyelid opening. Prior to eyelid opening, proteoglycan localization is first detected in the anterior corneal stroma. When the lids open and there is increased oxygen, proteoglycan deposition is detected in the posterior stroma (Gregory et al., 1988; Cintron and Covington, 1990). Other changes in matrix proteins appear to depend on the levels of oxygenation. For example, fibronectin is detected in the corneal stroma during development; but is no longer detected in the unwounded adult cornea (Cintron et al., 1984).

Investigators have demonstrated that decreased oxygenation of the cornea alters its function and physiology (Teranishi et al., 2008; Hara et al., 2009). The barrier function of the apical corneal epithelium is disrupted upon exposure to prolonged hypoxia (Table 1). In rabbit corneas, hypoxia impairs the integrity of tight junctions and the localization of zonula occludens-1, a tight junction protein (Teranishi et al., 2008). In addition, low-oxygenated environments may affect immune responses where the expression of Toll-like receptor 4 is downregulated, leading to a reduction in nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (Table 1; Hara et al., 2009).

TABLE 1.

Role of chronic hypoxia on the cornea

| Group | Effect of chronic hypoxia on the cornea | Cell/tissue type |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Teranishi et al. (2008) | Corneal barrier function disruptions via changes in tight junction integrity and ZO-1 localization | Rabbit corneas |

| Lee et al. (2014) | Delayed wound healing; reduction in ATP levels and altered calcium mobilization after injury | Human corneal limbal epithelial cells; rat corneas |

| Bhadange et al. (2018) | Protection against cell death after mechanical injury | Human corneal endothelial cells |

| Hara et al. (2009) | Impaired inflammatory response; downregulation of TLR4 and NFkB | Human corneal epithelial cells |

| Phillip et al. (2000); Safvati et al. (2009); Sanyal et al. (2017) | Upregulation of angiogenic and inflammatory factors; neovascularization | Human corneas |

| Zaidi et al. (2004); Yamamoto et al. (2005); Yamamoto et al. (2006a); Yamamoto et al. (2006b) | Lipid raft formation in the epithelium; increased internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa; corneal inflammation | Rabbit corneal epithelium; human corneal epithelium |

| Sarver et al. (1983); Holden et al. (1984) | Corneal edema | Human corneas |

| Klyce (1981) | Corneal edema; stromal lactate accumulation | Rabbit corneal epithelial cells |

| Choy et al. (2004) | Increased albumin and lactose dehydrogenase at the corneal surface | Human corneal epithelium |

| Lee et al. (2018) | Decreased expression of small leucine-rich proteoglycans (decorin, lumican, and keratocan); increased perlecan expression; alterations in Type III collagen and fibronectin localization; decreased sulfation of heparan sulfate proteoglycans | Corneal stromal construct |

| Kazuhiro et al. (2018) | Decreased glycogen granules | Mice corneal epithelial cells |

| McKay et al. (2017) | Decreased Type 1 collagen secretion; increased MMP-1 and MMP-2 expression; reduced ECM thickness | Human keratoconus-derived corneal fibroblasts |

| Carney (1975); McNamara et al. (1999) | Increased central and peripheral corneal thickness | Human corneas |

| Robertson (2013) | Thinning of the epithelium | Human corneal epithelium |

Pathologies such as diabetes, herpes simplex virus infection, dry eye syndrome, and limbal stem cell deficiency can cause a transition to a hypoxic state, where oxygen levels are at or below 8% for various time periods (Boost et al., 2017; Kanda et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Sanyal et al., 2017). Under these conditions, vascularization of the cornea may occur. Corneal avascularization is required for refraction of light through the lens to the retina. The formation of blood vessels and subsequent decrease in corneal transparency that can occur during injury or disease are additional side effects of a chronic hypoxic environment. Overall, these changes are thought to result from an increase in the expression of angiogenic factors and the factors involved in corneal inflammation (Table 1) (Phillip et al., 2000; Safvati et al., 2009).

To examine the response to hypoxia in the cornea, a number of models have been used. One is a corneal organ culture model that maintains the typical 3D configuration and allows for analysis of cell migration, wound repair, matrix deposition, and focal adhesion formation (Gordon et al., 2010; Minns and Trinkaus-Randall, 2016). The other model is a human stromal construct that recapitulates the deposition of matrix molecules under different environments (Ren et al., 2008). A significant delay in the repair rate of epithelial abrasions under hypoxic conditions is demonstrated using the corneal organ culture wound model (Lee et al., 2018) (Table 1). Exposure to hypoxia causes a change in the extracellular matrix proteins deposited along a murine basal lamina and in the formation of a stroma using the human stromal construct. Using the latter, we demonstrated that increasing exposure to hypoxia caused a decrease in both the sulfation of proteoglycans and the expression of sulfatase I mRNA (Table 1). These were supported by studies where corneal epithelium was debrided and the cornea was placed in organ culture under normoxic or hypoxic conditions, and there was a change in the population of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (Lee et al., 2018). In human cells from corneas with keratoconus, acute hypoxia regulated collagen and matrix metalloproteinase expression (McKay et al., 2017).

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans are critical to the organization of matrix proteins. One in vitro study showed heparan sulfate was necessary to induce the alignment of fibronectin fibrils (Mitsi et al., 2006). The regulation of fibronectin is unique in the cornea as it is not detected in an unwounded state. However, after injury fibronectin is transiently localized along the basal lamina, where it provides a temporary matrix for epithelial cells to migrate and or heal (Zieske et al., 1987). During wound closure, epithelial protein synthesis reaches a maximum rate of 16–18 hr after wounding, a time point when fibronectin is elevated (Zieske and Gipson, 1986). Similar results were obtained using the corneal organ culture model, where fibronectin was present transiently along the basal lamina and in the anterior stroma. However, when corneas were exposed to hypoxic conditions, there was a reduction in fibronectin (Table 1) (Lee et al., 2018). These results indicate that the response in our organ culture system is similar to the physiological wound response in vivo. It is speculated that the hypoxic environment may impair the secretion of fibronectin and the diminished protein impairs the ability of the epithelial cells to pull along the fibronectin provisional matrix, ultimately compromising wound repair. An elegant in vitro study by Hubbard supports this idea by demonstrating that there is a change in morphology of the cells as they move along a single fibronectin molecule (Hubbard et al., 2016). Overall, these data indicate that the stromal matrix and the basal lamina are altered with changes in oxygen tension that exceed the normal diurnal changes.

In this study, we demonstrate that hypoxia modifies the deposition of laminin and Type IV collagen and a change in localization of focal adhesions in the cornea. Experiments on substrates with a range of stiffness revealed changes in morphology. There was an increase in vacuoles in cells incubated in hypoxic environments. Additionally, there was a change in localization and phosphorylation of residues of vinculin in a hypoxic environment in vitro that were accompanied by additional changes in the length and number of focal adhesions. These suggest a difference in the tension that a cell exerts as it moves along a matrix protein. The changes in the matrix and stiffness are potential contributors to the delayed healing response when corneas are subjected to hypoxic conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

The following antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO): anti-phospho-vinculin (pTyr822) polyclonal rabbit antibodies (catalog #V4889–1VL), anti-talin monoclonal mouse antibodies (clone 8d4, catalog #T3287), and anti-laminin-5 (γ2 chain) monoclonal mouse antibodies (clone D4B5, catalog # MAB19562). Anti-Type IV collagen monoclonal mouse antibodies (catalog #MA1–22148), anti-vinculin (pTyr1065) phosphospecific unconjugated polyclonal rabbit antibodies (catalog #44–1078G), anti-phospho-paxillin (pTyr118) polyclonal rabbit antibodies (catalog #2541S), and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (catalog #A11008) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Cambridge, MA).

Reagents

Human plasma fibronectin (catalog #FC010–10MG) was purchased from EMD Millipore Corporation (Temecula, CA). Collagen from human placenta (Bornstein and Traub Type IV, catalog #C5533–5MG) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM) 1× (catalog #10724–011), human recombinant Epithelial Growth Factor (EGF, catalog #10450–013), Bovine Pituitary Extract (catalog #13028–014), and amphotericin B (Fungizone, catalog #15290–018) were purchased from GIBCO (Grand Island, NY). Penicillin–streptomycin (catalog #30–002-CI) and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 1 g/L glucose (catalog #10–014-CV) were acquired from Cellgro (Herndon, VA). VectaSHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (catalog #H-1200) was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA).

Cell Culture

Human corneal limbal epithelial (HCLE) cells were a gift from the lab of Dr. Ilene K. Gipson (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). The cells were cultured in K-SFM, supplemented with 0.5% amphotericin B, 0.02 nM EGF, 25 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract, 0.03 mM CaCl2, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were plated at a density of 80–100 cells/mm2 on fetal bovine serum (FBS)-coated 22 mm square glass coverslips #1.5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The growth medium was removed 16 hr prior to experimentation and replaced with supplement-free K-SFM.

To determine the effects of matrix protein and stiffness, the cells were plated at a density of 20 cells/mm2 on fibronectin or collagen-coated polyacrylamide gels (Matrigen, Brea, CA) or glass bottom microwell dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA). The stiffnesses examined were 0.2, 8, 25, and 50 kPa. Epithelial cells were incubated under hypoxic conditions (1% O2, 5% CO2, and 94% N2) using a hypoxic chamber (New Brunswick Scientific, Enfield, CT) for 2, 3, 5, 18, and 24 hr. Control cells and organ cultures were incubated in a normoxic environment (21% O2, 5% CO2, and 74% N2)for equivalent lengths of time. At the completion of each experiment, the cells were fixed and stained with rhodamine phalloidin for 1 hr at room temperature.

Organ Culture

Mother rats (Charles River Labs., Wilmington, MA) were euthanized, a 3-mm-diameter demarcation was made in the center of the corneas with a trephine, and the epithelium was removed. Rat corneas were removed with adjacent sclera and placed on molds (Gordon et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2014). Briefly, the eyes were washed several times in ice-cold DMEM and 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.5). Corneas and the adjacent 2 mm of sclera tissue were removed. A solution of warm DMEM containing 0.75% low melt agar was added to the posterior region of each cornea to maintain the natural curvature of the cornea. Once the agar hardened, the corneas were placed anterior side up into culture dishes and sufficient DMEM was added to cover the scleral rim. The corneas were incubated under normoxic conditions (21% O2, 5% CO2, and 74% N2) or hypoxic conditions (1% O2, 5% CO2, and 94% N2) for 18 hr.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy

Corneal epithelial cells or organ cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min (cells) or for 30 min (organ cultures) at room temperature. Corneas were sectioned radially and immunofluorescence staining was performed. The cells or tissues were permeabilized for 5 min with 0.1% v/v Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked for 3 hr at room temperature with 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Samples were incubated in primary antibody solutions overnight at 4°C, washed, and then incubated in Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (1:100) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 1% BSA for 1 hr at room temperature. The samples were counterstained with rhodamine phalloidin (1:50) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to examine F-actin. The cells or tissues were mounted using VectaSHIELD with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Images were taken using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with either a 40× oil or 63× oil objective. Secondary antibody controls were used to set the gain of the laser, and experimental samples were imaged at the same gain. The pinhole size was kept at 1 Airy unit across all images. Images were obtained using Zen Black Edition software (Zeiss) and analyzed with FIJI/ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, CA).

Live Cell Imaging

Polyacrylamide gels of different stiffnesses (Matrigen) were coated with 0.2 mg/mL fibronectin or Type IV collagen for 1 hr at room temperature. Gels were washed with PBS and blocked for 1 hr in 3% BSA in PBS. Cells were added to the gels at a density of 20 cells/mm2 and cultured in K-SFM, supplemented with 30 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract, 0.032 nM EGF, and 100 μ/mL penicillin–streptomycin. HCLE cells were incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Live cell imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope with the environmental chamber and the temperature was set to 35°C. Images were taken using a 20× objective at 2, 3, 5, 18, and 24 hr and analysis was conducted using FIJI.

Atomic Force Microscopy

Nanoindentation measurements were performed on rat corneas using an atomic force microscope (AFM) (MFP-3D; Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) with a micromanipulator-controlled stage and a silicon nitride cantilever (0.06 N/m) functionalized with a 5 μm borosilicate bead (Novascan, Boone, IA). The corneal epithelium was removed immediately prior to the experimental trial and the cornea was placed basal lamina side up. The cornea was placed in DMEM. The central region of the corneas was measured. To perform the indentation on the basal lamina, the tip was moved down until there was a deflection of 1 V or 1.85 nN of force. Experiments were performed at room temperature in steps parallel to the direction of the gradient at an indentation rate of 500 nm/s. The elastic modulus was calculated by fitting force versus indentation depth data to a linearized Hertz model (Domke and Radmacher, 1998; Guo and Akhremitchev, 2006).

Statistical Analysis

Values are means SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or unpaired, one-tailed t-test using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Changes in Stiffness and Matrix Alter HCLE Cell Morphology

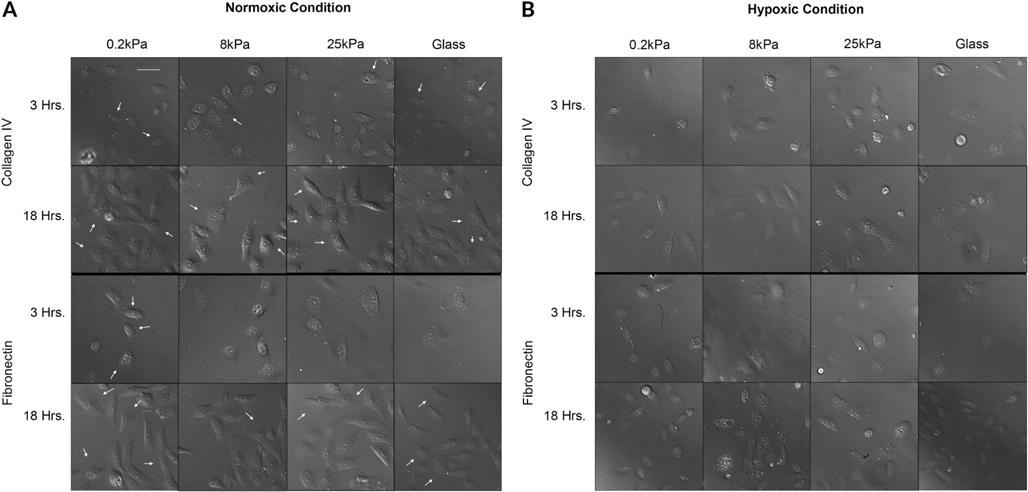

To determine the effects that substrate stiffness and matrix protein have on epithelial cell behavior, subconfluent epithelial cells were examined over time. Live cell imaging was performed on cells seeded onto fibronectin and Type IV collagen-coated polyacrylamide gels with stiffness values of 0.2, 8, 25, and 50 kPa. These were compared to glass coverslips coated with the two matrix proteins. The range of values were chosen to simulate the stiffness of the epithelial surface (0.2 kPa), the basement membrane zone (8 kPa), and the corneal stroma (40–50 kPa). The cells were plated and cultured in normoxic and hypoxic environments and examined at 2, 3, 5, 18, and 24 hr. Representative images of the cellular morphology are shown (Fig. 1A,B). At 24 hr, the cells were stained with rhodamine phalloidin to examine their cellular architecture (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Corneal epithelial cell morphology. Epithelial cells were cultured on fibronectin- and collagen IV-coated substrates of different stiffness values under normoxic (A) and hypoxic (B) conditions. Images are representative of a minimum of five independent experiments for each time point and condition. Changes in cell morphology are substrate and environment dependent. Scale bar = 66 μm.

Under normoxic conditions, membrane ruffling was present throughout all stiffnesses coated with Type IV collagen at 3 and 18 hr (see arrows) (Fig. 1A). However, on fibronectin-coated stiffnesses, membrane ruffling was detected at 18 hr (see arrows) (Fig. 1A). At 3 hr, membrane blebbing was detected on fibronectin coated 0.2 kPa (see arrows). Major changes that occurred under hypoxic conditions at all stiffness values included increased volume and flattening of the cell shape; morphological changes that have been associated with cellular senescence (Ben-Porath and Weinberg, 2004) (Fig. 1B). Under hypoxic conditions, cytosolic vacuoles were prominent by 18 hr with cells cultured on fibronectin exhibiting greater levels of stress (Fig. 1B). These vacuoles may be features of cellular stress induced by hypoxia (Shimizu et al., 1996). In addition, under hypoxic conditions, membrane ruffling was less extensive on the cells seeded on fibronectin-coated substrates.

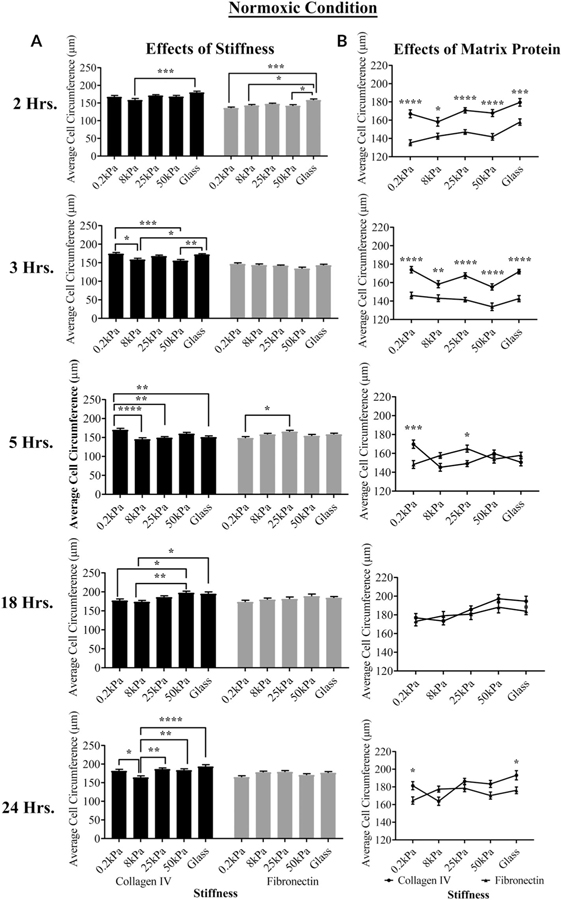

The effects of the matrix and substrate on the cell circumference under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, respectively, are shown in Figures 2A–D. When the cells were cultured under normoxic conditions on fibronectin and Type IV collagen at the five stiffness values, the effect of stiffness on average cell circumference was consistently the greatest between the cells cultured on 8 kPa and glass coated with Type IV collagen at 2, 3, 18, and 24 hr (***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, *P < 0.05, and ****P < 0.0001, respectively; two-way ANOVA) (Fig. 2A). On the fibronectin-coated substrates, differences were only significant at 2 hr between 8 kPa and glass *P < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Fig. 2A). When the cells seeded on either matrix protein were compared, there were significant differences in the circumference between cells cultured on Type IV collagen and fibronectin at 0.2, 8, 25, 50 kPa, and glass (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA) at both 2 and 3 hr. The effect of matrix protein was detected at later time points on 0.2 kPa (Fig. 2B). The morphological changes are indicative of deposition of additional matrix protein(s) (Bergethon and Trinkaus-Randall, 1989).

Fig. 2.

The effects of hypoxia, matrix protein, and stiffness on cell circumference over time. Cell shape was determined using FIJI. (A,B) The effects of stiffness and substrate over time under normoxic conditions. (C,D) The effects of stiffness and substrate over time under hypoxic conditions. Statistical analysis was conducted (ANOVA). Standard error bars are ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, and ****P < 0.005.

In contrast to normoxic conditions, when cells were cultured under hypoxic conditions, the effects of stiffness were more significant than the effects of matrix protein (Fig. 2C,D). Significant differences were detected between cells cultured on 0.2 kPa and glass coated with Type IV collagen at 2, 3, and 18 hr (***P < 0.001 and *P < 0.05, respectively; two-way ANOVA). Likewise, significant differences were detected between cells cultured on the 0.2 kPa and stiffer substrates coated with fibronectin at 3, 5, 18, and 24 hr (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA) (Fig. 2C). When comparing cells on either matrix protein, there was a significant difference between the cells cultured on Type IV collagen and fibronectin at 25 kPa (***P < 0.001; two-way ANOVA) at 18 hr (Fig. 2D). Overall, the data presented indicate that cell morphology and behavior are influenced by substrate stiffness. However, within a stiffness, there was a greater influence of matrix protein on average cell circumference under normoxic conditions than under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 2B).

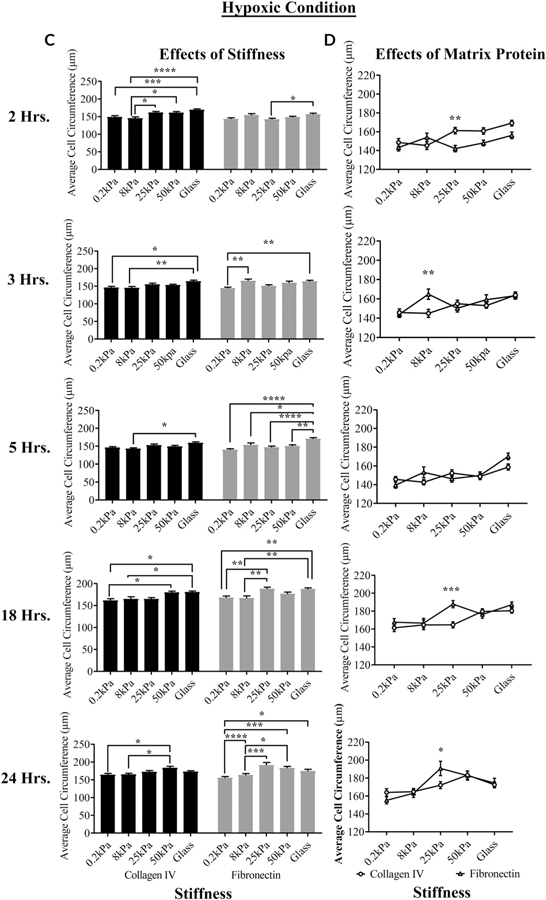

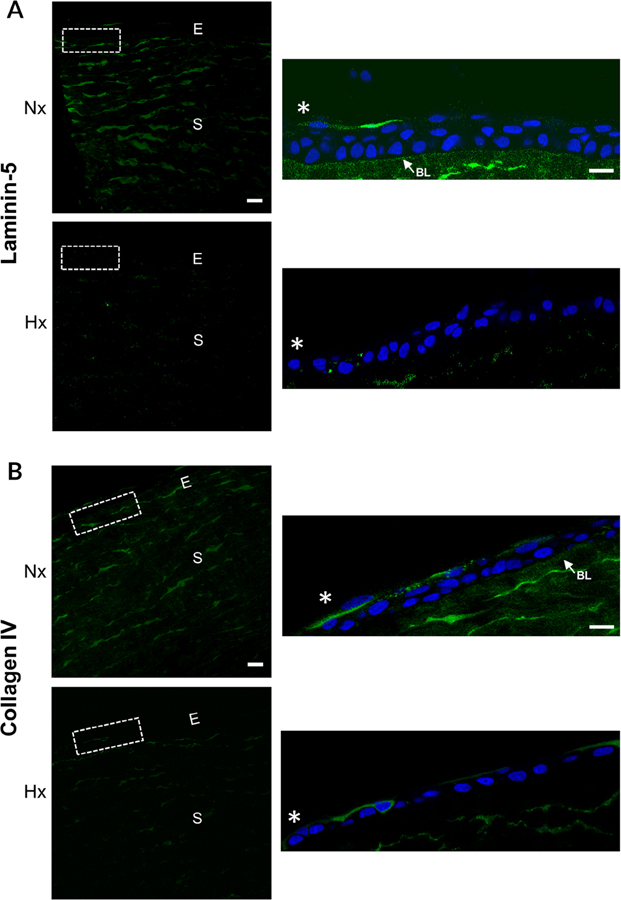

Hypoxia Reduces Deposition of Laminin-5 and Type IV Collagen

Previously we demonstrated changes in fibronectin and heparan sulfate proteoglycans with injury and hypoxia (Lee et al., 2018). Since laminin and Type IV collagen are present in the basal lamina, we evaluated the effect of hypoxia on their localization (Fig. 3A). Immunostaining was performed on normoxic and hypoxic corneas 18 hr after injury. Under normoxic conditions, laminin-5 localized to the basal lamina and the stroma (Fig. 3A). Staining was reduced when the corneas were incubated under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3A). Type IV collagen is present along the basal lamina and is a part of the hemidemosomal complexes present in the stroma. It differs from fibrillar collagens as it is present as a lattice. Type IV collagen was minimal until the intensity was increased (insets) and it was detected in the stroma and along the basal lamina. There was a similar decrease in localization of Type IV upon exposure to hypoxia (Fig. 3B). Investigators found a decrease in laminin in diabetic corneas (Azar et al., 1992; Sady et al., 1995; Ljubimov et al., 1998). It is not known if the reduction in laminin under hypoxic and diabetic environments is coincidental or if the environmental changes in the diabetic cornea induce a similar response.

Fig. 3.

Hypoxia modulates the localization of laminin and Type IV collagen in wounded corneas. Epithelial abrasions were performed and corneas incubated in normoxic or hypoxic environments for 18 hours. Corneas were immunostained for laminin-5 and Type IV collagen and counterstained with DAPI. Images were obtained at 40× magnification using a Zeiss Axiovert LSM 700 confocal microscope. The region outlined is shown in inset. A, Laminin-5 is reduced along the basal lamina and in the stroma of hypoxic corneas. Arrow indicates laminin-5 localization to the basal lamina. B, Type IV collagen localization is reduced along the basal lamina and stroma after exposure to hypoxic conditions. Arrow indicates Type IV collagen localization to the basal lamina in the normoxic cornea. Scale bar = 100 μm. *, wound edge. Images are representative of a minimum of three independent experiments. Nx, normoxia; Hx, hypoxia; E, epithelium; S, stroma; BL, basal lamina.

Corneas Exposed to Hypoxic Conditions Exhibit Increasing Trend in Basal Lamina Stiffness

We speculated that the change in matrix protein localization and expression could alter the stiffness of the basal lamina (Lee et al., 2018). AFM was used to measure the basal lamina stiffness in uninjured rat corneas. The eyes were incubated in DMEM in normoxic or hypoxic incubators for 18 hr. Immediately prior to measuring stiffness, the epithelium was removed and four slits were cut in the corneas so that they would lie flat and they were placed on glass slides and DMEM was added to maintain hydration. The indentation of a 5 μm radius spherical bead was less than 400 nm, which correspond to the stiffness values in the kPa range consistent with that reported for a basal lamina (Thomasy et al., 2014). An indentation of this value is acceptable when using a 5-μm-radius bead, and the material being evaluated is more than 4 μm thick. Our results indicate that the value should not be influenced by underlying stromal layers.

The basal lamina stiffness of corneas incubated under normoxic conditions ranged from 2.2 to 5.6 kPa, with a mean of 4.3 kPa (Table 2). The basal lamina stiffness of unwounded corneas exposed to hypoxic conditions had values ranging from 6.2 to 10 kPa with a mean of 8.1 kPa (Table 2). The large range detected in the measurements may reflect the length of time the corneas were incubated. These data indicate that there is a trend toward increased stiffness under hypoxic conditions and should be compared to corneas with defined pathologies. The data represent an average of the repeats from similar indentation sites (technical repeats) on a single cornea averaged with values from other corneas.

TABLE 2.

Basal lamina stiffness in normoxic and hypoxic rat corneas

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Unwounded cornea (kPa) | 2.2 | 6.2 |

| 5.1 | 8.0 | |

| 5.6 | 10.0 | |

| Mean (kPa) | 4.3 ± 1.84 | 8.1 ± 1.90 |

Corneas were incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 18 hr. Epithelium was removed immediately prior to experimentation and corneas were placed onto glass slides. DMEM/penicillin–streptomycin was added before measurement of the basal lamina. An atomic force microscope (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) with indentation of a 5 μm radius spherical bead was used. Measurements of the basement membrane zone were obtained in the central cornea. Each number represents the average of two measurements at a given spot. The data represent a minimum of three independent runs for each condition.

Hypoxia Alters the Localization of Focal Adhesion Proteins

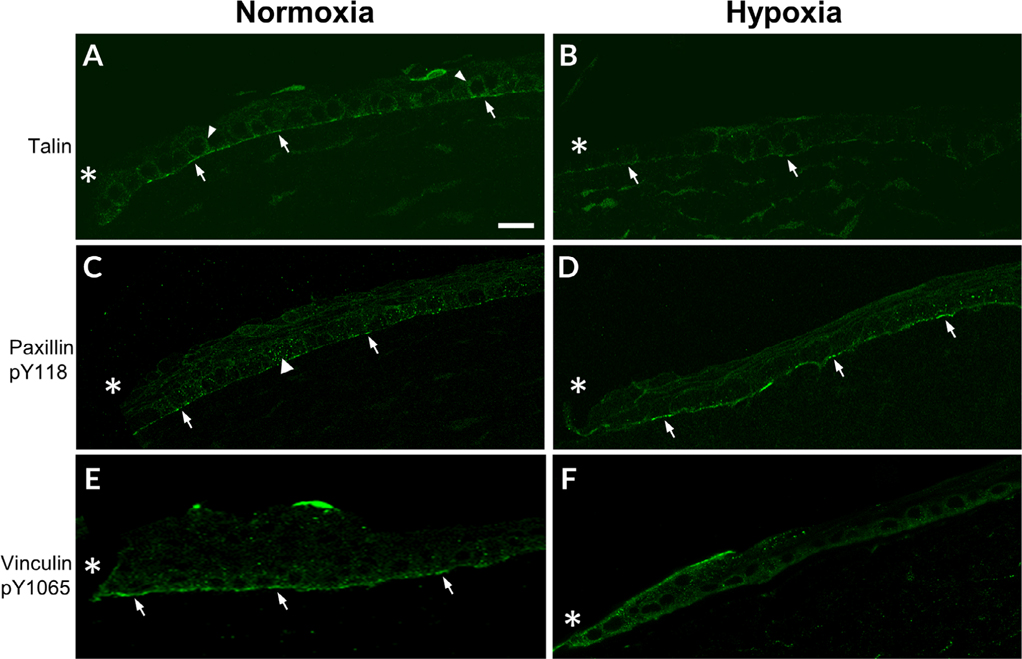

To study the effect of hypoxia on epithelial cell migration after corneal injury, changes in focal adhesion proteins were examined (Fig. 4). The actin cytoskeleton of migrating cells interacts with extracellular matrix proteins to form focal adhesion complexes, enabling cells to move over the underlying substrate. The focal adhesion protein, talin, initiates the formation of nascent focal complexes by binding to β1-integrin and acting as a docking site for adaptor proteins. Corneal abrasions were made to analyze adhesion structures in the migrating epithelium of both normoxic and hypoxic corneas. After 18 hr in normoxic conditions, talin localized along the basal (arrows) and basolateral surfaces of epithelial cells (arrowhead) (Fig. 4A). Under hypoxic conditions, localization was reduced (arrow), but staining was detected along cells in the anterior stroma (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Localization of focal adhesion proteins is altered under hypoxic conditions. A–D, Corneas were wounded, incubated in normoxic or hypoxic environments for 18 hr, and stained for focal adhesion proteins. Images were obtained at 40× magnification using a Zeiss Axiovert LSM 700 confocal microscope and are representative of a minimum of three experiments. A, Talin localizes along the basal surface (arrows) and along basolateral surface (arrowheads) of corneal epithelial cells. B, Talin is diminished after exposure to hypoxic conditions. Arrows indicate localization to the basal surface. C, Paxillin pY118 localizes to the basal surface (arrows) and the basolateral surface (arrowhead) of epithelial cells D, Paxillin pY118 localization is present along the basal surface (arrows). E, Vinculin pY1065 localizes to the basal surface (arrows). F, Vinculin pY1065 is present at the wound edge along basal and apical surface. *, wound edge. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Paxillin pY118, another component of the focal adhesion complex, binds to β1-integrin and talin and acts as a docking site for adhesion proteins (Glenney and Zokas, 1989; Turner et al., 1990; Zaidel-Bar et al., 2007). Mass spectrometry phosphoproteomic data indicate that there is differential phosphorylation of paxillin Y118 that occurs after injury, stimulation with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or the growth factor, EGF. All of these molecules are released with injury or from tears. Moreover, inhibition of specific purinoreceptors inhibits phosphorylation of the latter residue (Kehasse et al., 2013). Others have demonstrated that paxillin pY118 has an essential role in activating vinculin pY1065 (Glenney and Zokas, 1989; Turner et al., 1990; Zaidel-Bar et al., 2007). In these studies, under normoxic conditions, paxillin pY118 was present in a punctate pattern along the basal surface of cells (arrows) and along the basolateral membranes (arrowhead; Fig. 4C). Under hypoxic conditions, paxillin pY118 was present almost continuously along the basal surface in the migrating epithelium (arrows; Fig. 4D).

Although Zieske demonstrated a change in the localization of vinculin after corneal abrasion, an understanding of the role of phosphorylation at Y1065 in focal adhesion maturation was not understood for several years (Zieske et al., 1989; Grashoff et al., 2010; Auernheimer et al., 2015). Under normoxic conditions, vinculin pY1065 localized along the basal surface of the leading edge, indicating its presence in focal adhesions (arrows; Fig. 4E). However, in the corneas incubated under hypoxic conditions for 18 hr, there was decreased localization along the basal surface of the epithelium. Instead, vinculin pY1065 was present along the apical and basal surfaces of the cells at the leading edge of the wound (asterisk) and decreased with distance from the wound (Fig. 4F). We speculate that the changes in vinculin pY1065 localization may be a factor in the delayed rate of healing in hypoxic corneas. Furthermore, these alterations may relate to changes observed with paxillin pY118 localization under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 4D). The increased paxillin pY118 along the basal surface of epithelial cells may assist in recruitment of vinculin pY1065 to adhesion sites.

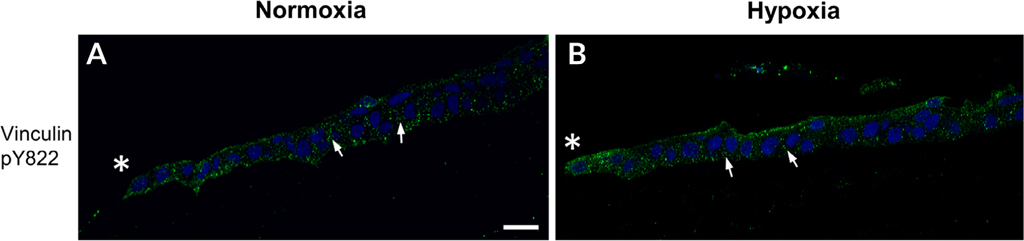

Successful migration as an epithelial sheet requires communication of neighboring cells that is achieved by the formation of cell–cell junctions such as cadherin. Vinculin pY822 has a role in stabilizing the E-cadherin-containing adherens junctions (Perez-Moreno et al., 2003; Bays et al., 2014). Therefore, vinculin pY822 localization was examined to determine whether a reduction in vinculin pY822 could be a contributing factor in the impaired migration observed in hypoxic corneas. However, punctate vinculin pY822 staining was detected between adjacent epithelium of the leading edge of wounded corneas exposed to either normoxic or hypoxic conditions (arrows; Fig. 5A,B). Thus, hypoxia does not appear to alter vinculin pY822 localization. These results indicate that hypoxic environments affect the localization of paxillin pY118 and vinculin pY1065 along the leading edge of the migrating epithelium. These alterations may affect the maturation of focal adhesion complexes, which would delay migration after injury in hypoxic corneas.

Fig. 5.

Localization of vinculin pY822 under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Corneas were wounded and incubated in normoxic or hypoxic environments for 18 hr. Corneas were immunostained for vinculin pY822 and counterstained with DAPI. Images were obtained at 40× magnification using a Zeiss Axiovert LSM 700 confocal microscope. (A,B) Vinculin pY822 localizes to cell–cell contacts (arrows). Images are representative of a minimum of three independent experiments. *, wound edge. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Paxillin pY118 and Vinculin pY1065 Focal Adhesion Length is Reduced under Hypoxia

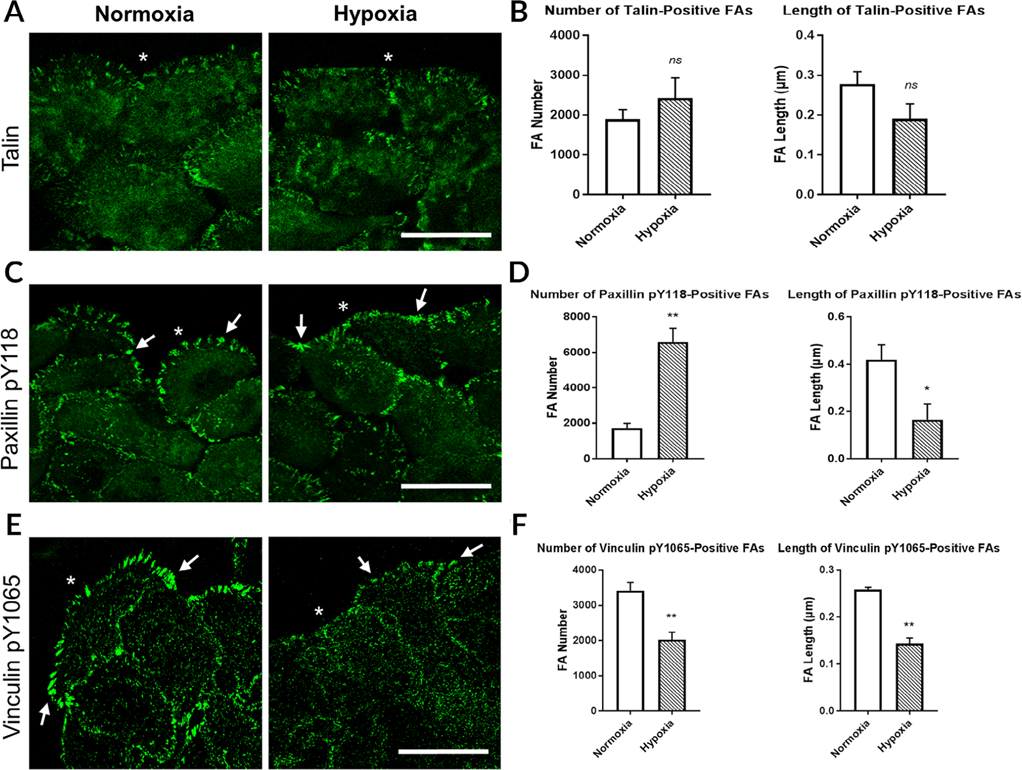

To further assess how hypoxia affects focal adhesion dynamics, we determined changes in focal adhesion number and length along the leading edge in an in vitro culture of epithelial cells. The cells were seeded, grown to confluence, wounded, and fixed 4 hr after injury. Four hours was chosen as a time point because the cells actively migrate under normoxic conditions, and the cells are not influenced by the opposing wound margin. In addition, an optimization study revealed a lack of any detectable difference in the localization of focal adhesions stained for talin or vinculin pY1065 at the 1 hr point.

Immunofluorescence was performed to observe changes in localization after exposure to hypoxia. Focal adhesion count and length were determined using FIJI. Under either normoxic or hypoxic conditions, talin localized to the leading edge of epithelial cells with additional diffuse staining in the cytoplasm (asterisk; Fig. 6A). As detected in the hypoxic corneas, the leading edge of epithelial cells cultured under hypoxic conditions had a blunt or flat-edge morphology. In addition, hypoxia did not significantly affect the number or length of talin-positive focal adhesions (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Hypoxia affects the number and length of paxillin pY118- and vinculin pY1065-positive focal adhesions. Human corneal limbal epithelial (HCLE) cells were wounded and incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 4 hr. HCLE cells were fixed and immunostained for focal adhesion proteins. Images were obtained at 40× magnification using a Zeiss Axiovert LSM 700 confocal microscope. The leading edge was analyzed in 500 μm intervals. Focal adhesion number and length were determined using FIJI. A, Talin localized to the leading edge. B, No significant change in talin-positive focal adhesion number or length under hypoxic conditions. C, Paxillin pY118-positive focal adhesions (arrows). D, Increased number and decreased length of paxillin pY118-positive focal adhesions when exposed to hypoxia. E, Vinculin pY1065-positive focal adhesions (arrows). F, Hypoxia reduced the number and length of vinculin pY1065-positive focal adhesions at the leading edge. Images are representative of a minimum of at least four independent experiments. *, wound edge. Scale bars = 50 μm. Standard error bars are ±SEM. (unpaired t-test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ns = not significant. FAs, focal adhesions.

After injury, paxillin pY118 localized to the wound edge in normoxic and hypoxic cells (Fig. 6C,D). In contrast to talin, the paxillin pY118 positive focal adhesions in epithelial cells cultured under normoxic conditions were localized further apart from each other in discrete regions (arrows). In contrast, the number of paxillin pY118-containing adhesions at the leading edge was more than threefold greater in the cells exposed to hypoxia (**P < 0.01; unpaired t-test) (Fig. 6D). Under hypoxic conditions, paxillin pY118 was continuous along the basal surface of the migrating epithelium, and this different pattern contributed to the increased number of adhesions present. These data correlate to the results obtained from organ culture experiments (Fig. 4B). Although the number increased, the length of paxillin pY118-containing adhesions was significantly lower in cells incubated under hypoxic conditions (*P < 0.05; unpaired t-test) (Fig. 6D). The reduction in length indicates that focal adhesion maturation may be affected by hypoxia and that the adhesions may exist as multiple nascent complexes along the borders of cells.

To further determine the effect that hypoxia has on focal adhesion formation, vinculin pY1065 was examined 4 hr after injury to confluent epithelial cells. Vinculin pY1065 prominently localized to adhesions at the leading edge (arrows; Fig. 6E), as was observed in normoxic corneas (Fig. 4E). Under hypoxic conditions, vinculin pY1065 was present at the wound edge, but these adhesions were shorter and similar to the paxillin pY188 focal adhesions (arrows; Fig. 6E). Unlike focalthe adhesions containing paxillin pY118, exposure to hypoxia led to reduction in both the number and length of focal adhesions containing vinculin pY1065 (**P < 0.01; unpaired t-test) (Fig. 6F). In comparison, when corneas were incubated under hypoxic conditions, pY1065 localization was altered with minimal localization along the basal surface distal to the wound edge (Fig. 4F). After exposure to hypoxia, the increased localization of paxillin pY118 at the leading edge in corneas and the increased paxillin pY118-containing adhesions in epithelial cells may be the compensatory effects resulting from vinculin pY1065 reduction. The increase in paxillin pY118 may indicate an increase in the recruitment of vinculin pY1065 to adhesion sites. In summary, lower oxygenated environments significantly affect the localization and morphology of paxillin pY118 and vinculin pY1065 focal adhesions. These alterations may affect the migration of corneal epithelial cells after injury, contributing to the delayed rate of wound closure occurring in corneas exposed to hypoxia.

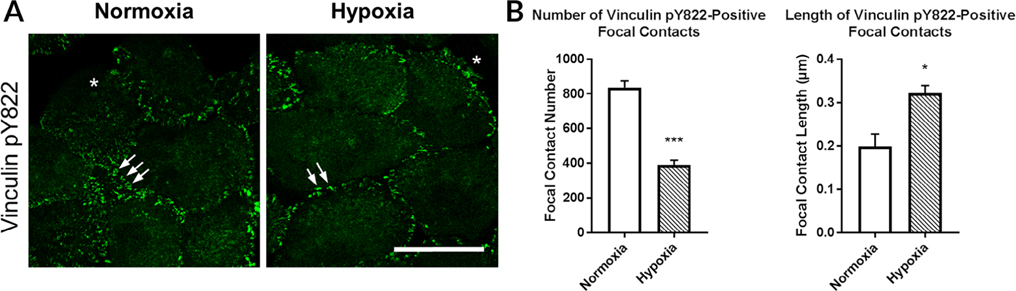

To examine cell–cell interactions, vinculin pY822 was examined under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. When vinculin is phosphorylated at tyrosine 822, it is recruited to cell–cell contacts (Fig. 7A,B). When the epithelial cells were cultured under hypoxic conditions, the distance between the focal contacts was greater, while they were clustered under normoxic conditions (arrows; Fig. 7A,B). Analysis of number and length revealed a significant decrease in the number of vinculin pY822-positive contacts and an increase in the length of contacts (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005; unpaired t-test) (Fig. 7A,B).

Fig. 7.

Vinculin pY822 localized to cell–cell contacts under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Cells were wounded and incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions and immunostained for vinculin pY822. Images were obtained at 40× magnification using a Zeiss Axiovert LSM 700 confocal microscope. The leading edge was analyzed in 500 μm intervals. The focal contact number and length were determined using FIJI. A, Vinculin pY822 localized primarily to cell–cell contacts. B, Hypoxia decreased the number but increased the length of vinculin pY822-positive cell–cell contacts. Images are representative of at least four independent experiments. *, wound edge. Scale bar = 50 μm. Standard error bars are ± SEM. (unpaired t-test). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005.

DISCUSSION

The cornea is an excellent tissue to study and understand the effect of hypoxia on matrix deposition, cell motility, and wound repair. In the diurnal wake–sleep cycle, the cornea is exposed to transitions between 21% and 8% oxygen, and investigators have demonstrated that hypoxia modifies the integrity of cell junctions (Hara et al., 2009). These results support earlier studies that found growth factors, such as epidermal growth factor, penetrate through impaired tight junctions, resulting in the upregulation of epidermal growth factor receptors (Zieske et al., 2000). In addition, the cornea may become vascularized in response to a hypoxic state during disease or trauma. Investigations on the development of retinal vasculature and ischemic retinal diseases showed that hypoxia could induce increased synthesis and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in several cell types (Phillip et al., 2000; Safvati et al., 2009; Azar et al., 1992; Ljubimov et al., 1998). Additionally, Fini et al. demonstrated that a delay in reepithelialization often preceded stromal ulceration, which they speculated to be due to changes in the substrate, along with increased matrix metalloproteinases (Fini et al., 1996).

When wounded rat corneas were exposed to hypoxic conditions, there was a delay in wound healing. There was also a change in the overall epithelial morphology at the leading edge and alterations in the basal lamina and/or anterior stroma, which may explain this delayed wound repair. Such changes involved a number of matrix proteins, including an increase in lysyl oxidase in the stroma, a decrease in fibronectin secretion, and an increase in heparan sulfate proteoglycans (Lee et al., 2018). Our current data demonstrated that hypoxia also resulted in reduced laminin and Type IV collagen. The effect of matrix proteins on migration was supported by observations in the diabetic cornea, where impaired wound healing was associated with a decrease in laminin along the basal lamina (Ljubimov et al., 1998). In other tissues, matrix proteins (fibronectin, laminin, and Type IV collagen) have a unique influence on the phenotypic properties of subcultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells (Thyberg and Hultgårdh-Nilsson, 1994). Overall, these results indicate that the alterations in matrix proteins may modify the stiffness of the cornea leading to a change in the interaction of cells with the underlying substrate.

The cornea is only one of many tissues that routinely responds to hypoxia. Another tissue that responds naturally to changes in environmental oxygen is the mitral valve. Investigators have demonstrated that the integrity of the mitral valve depends on the deposition of matrix proteins, and hypoxia reduces the secretion of sulfated proteoglycans (Salhiyyah et al., 2017). In addition, when articular cartilage was exposed to hypoxia, there was an increase in lysyl oxidase mRNA, which resulted in increased cross-links that may increase the cartilage stiffness (Makris et al., 2013). Similarly, the corneal stroma responds to hypoxia with an increase in lysyl oxidase mRNA (Lee et al., 2018). There is a range of environmental oxygen that induces changes in lysyl oxidase localization and expression, and when corneas were exposed to 10% oxygen, there was no detectable change in corneal vascularization and no sign of radical tissue injury (Mahelková et al., 2008). The latter results might be explained by the diurnal fluxes in environmental oxygen where the cornea is normally exposed to 8% oxygen during the sleep cycle (Morgan et al., 2010).

Recent experimental work has demonstrated the effect of matrix stiffness on cellular behavior (i.e., differentiation, spreading, and motility), which was modulated by the composition of the extracellular matrix upon which the cells were grown (Gilchrist et al., 2011; Sazonova et al., 2015). When cells migrated along either a natural or synthetic substrate, they attached through focal adhesion complexes. These multiprotein complexes linked the cytoskeleton to the underlying matrix, which transmitted forces across the adhesion sites, thus acting as a signaling center for cellular pathways that regulate cell motility and growth (Ingber, 2003). Moreover, the complexes are matrix type specific, and the integrin receptors that were recruited along the membrane differed depending on the matrix proteins that were present. This topic was explored in great detail in an extensive review on integrin receptors in the cornea during disease and after injury (Stepp, 2006). As the present data demonstrate that hypoxia alters both the matrix stiffness and proteins present along the basal lamina, future studies should address the changes in integrin receptors when environmental oxygen levels are decreased. We speculate that the decrease in migration may be due to a combination of factors stemming from the hypoxic environment, such as changes in the matrix, integrin receptors, and the subsequent formation of focal adhesions. Recently, investigators demonstrated that alterations in the amount of force applied through integrin receptors could affect the composition and maturation of focal adhesions (Kong et al., 2009; Kong et al., 2013; Schiller et al., 2013). Coll et al. demonstrated that vinculin reduced fibronectin adhesion, decreased lamellipodial protrusions, increased migration, and altered cell morphology in mutant cells (Coll et al., 1995). Alenhat et al. demonstrated that deleting vinculin caused changes in cellular mechanics (Alenghat et al., 2000), while others showed that an increase in vinculin pY1065 amplified the recruitment and binding of adaptor proteins, which may explain the presence of larger and stronger focal adhesions (del Rio et al., 2009; Austen et al., 2015). In addition, another residue on vinculin, vinculin Y100, was identified for its potential role in cellular force transmission (Auernheimer et al., 2015).

Our results demonstrate that hypoxia alters the localization of vinculin pY1065 in migrating corneal epithelium. Under normoxic conditions, vinculin pY1065 was localized along the basal surface of cells, and under hypoxic conditions, it decreased distal to the leading edge. In addition, paxillin pY118 localized to the basal surface of the migrating epithelium, while it was punctate under normoxic conditions. In our in vitro studies, the number and length of vinculin pY1065-containing focal adhesions were significantly reduced after exposure to hypoxia, indicating that the adhesions may remain as nascent focal complexes, thereby indicating a lack of adhesion maturation. Evidence of changes in the mechanical linkage between cells under hypoxic conditions is demonstrated by the increased spacing of pY822 vinculin focal contacts.

In conclusion, exposure of the cornea to a hypoxic environment alters the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, and upon injury, it affects cell migration. These effects of hypoxia are potentially caused by alterations in basal lamina stiffness and localization at focal adhesions of specific phosphorylated proteins. The stiffness of the basal lamina was increased in unwounded corneas incubated under hypoxic conditions. In 3D organ culture, laminin and collagen Type I localization were altered after exposure to hypoxia, which agrees with previous studies showing changes in fibronectin and heparan sulfate proteoglycan cores along the basal lamina (Lee et al., 2018). Therefore, we speculate that the alterations in matrix composition and focal adhesion dynamics may contribute to the impaired migration and healing associated with chronic hypoxic conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Christopher Hartman for his extensive assistance with the atomic force measurements. We thank Yoonjoo Lee, Audrey Hutcheon, and Garrett Rhodes for their constructive criticism and assistance with figures. We thank Dr. Symes for her critical comments.

Grant sponsor: Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund; Grant sponsor: National Eye Institute; Grant numbers: EY06000, EY06000S; Grant sponsor: New England Corneal Transplant Fund to Boston University.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

LITERATURE CITED

- Alenghat FJ, Fabry B, Tsai KY, Goldmann WH, Ingber DE. 2000. Analysis of cell mechanics in single vinculin-deficient cells using a magnetic tweezer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 277:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auernheimer V, Lautscham LA, Leidenberger M, Friedrich O, Kappes B, Fabry B, Goldmann WH. 2015. Vinculin phosphorylation at residues Y100 and Y1065 is required for cellular force transmission. J Cell Sci 128:3435–3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austen K, Ringer P, Mehlich A, Chrostek-Grashoff A, Kluger C, Klingner C, Sabass B, Zent R, Rief M, Grashoff C. 2015. Extracellular rigidity sensing by talin isoform-specific mechanical linkages. Nat Cell Biol 17:1597–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar DT, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Tisdale AS, Gipson IK. 1992. Altered epithelial-basement membrane interactions in diabetic corneas. Arch Ophthalmol 110:537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays JL, Peng X, Tolbert CE, Guilluy C, Angell AE, Pan Y, Superfine R, Burridge K, DeMali KA. 2014. Vinculin phosphorylation differentially regulates mechanotransduction at cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Biol 205:251–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath I, Weinberg RA. 2004. When cells get stressed: an integrative view of cellular senescence. J Clin Invest 113:8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergethon P, Trinkaus-Randall V. 1989. Modified hydroxyethyl-methacrylate hydrogels as a modelling tool for the study of cell-substratum interactions. J Cell Sci 92:111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadange Y, Lautert J, Li S, Lawando E, Kim ET, Soper MC, Price FW Jr, Price MO, Bonanno JA. 2018. Hypoxia and the prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor FG-4592 protect corneal endothelial cells from mechanical and perioperative surgical stress. Cornea 37:501–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boost M, Cho P, Wang Z. 2017. Disturbing the balance: effect of contact lens use on the ocular proteome and microbiome. Clin Exp Optom 100:459–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney LG. 1975. Effect of hypoxia on central and peripheral corneal thickness and corneal topography. Aust J Optom 58:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy CKM, Cho P, Benzie IFF, Ng V. 2004. Effect of one overnight wear of orthokeratology lenses on tear composition. Optom Vis Sci 81:414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintron C, Covington HI. 1990. Proteoglycan distribution in developing rabbit cornea. J Histochem Cytochem 38:675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintron C, Fujikawa LS, Covington H, Foster CS, Colvin RB. 1984. Fibronectin in developing rabbit cornea. Curr Eye Res 3:489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll JL, Ben-Ze’ev A, Ezzell RM, Rodriguez Fernandez JL, Baribault H, Oshima RG, Adamson ED. 1995. Targeted disruption of vinculin genes in F9 and embryonic stem cells changes cell morphology, adhesion, and locomotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:9161–9165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domke J, Radmacher M. 1998. Measuring the elastic properties of thin polymer films with the atomic force microscope. Langmuir 14: 3320–3325. [Google Scholar]

- Fini ME, Parks WC, Rinehart WB, Girard MT, Matsubara M, Cook JR, West-Mays JA, Sadow PM, Burgeson RE, Jeffrey JJ, et al. 1996. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in failure to re-epithelialize after corneal injury. Am J Pathol 149:1287–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist CL, Darling EM, Chen J, Setton LA. 2011. Extracellular matrix ligand and stiffness modulate immature nucleus pulposus cell-cell interactions. PLoS One 6:e27170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenney JR, Zokas L. 1989. Novel tyrosine kinase substrates from Rous sarcoma virus-transformed cells are present in the membrane skeleton. J Cell Biol 108:2401–2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MK, Desantis A, Deshmukh M, Lacey CJ, Hahn RA, Beloni J, Anumolu SS, Schlager JJ, Gallo MA, Gerecke DR, et al. 2010. Doxycycline hydrogels as a potential therapy for ocular vesicant injury. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 26:407–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grashoff C, Hoffman BD, Brenner MD, Zhou R, Parsons M, Yang MT, McLean MA, Sligar SG, Chen CS, Ha T, et al. 2010. Measuring mechanical tension across vinculin reveals regulation of focal adhesion dynamics. Nature 466:263–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory JD, Damle SP, Covington HI, Cintron C. 1988. Developmental changes in proteoglycans of rabbit corneal stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 29:1413–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Akhremitchev BB. 2006. Packing density and structural heterogeneity of insulin amyloid fibrils measured by AFM nanoindentation. Biomacromolecules 7:1630–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Shiraishi A, Ohashi Y. 2009. Hypoxia-altered signaling pathways of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in human corneal epithelial cells. Mol Vis 15:2515–2520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden BA, Sweeney DF, Sanderson G. 1984. The minimum precorneal oxygen tension to avoid corneal edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 25:476–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard B, Buczek-Thomas JA, Nugent MA, Smith ML. 2016. Fibronectin fiber extension decreases cell spreading and migration. J Cell Physiol 231:1728–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. 2003. Mechanosensation through integrins: cells act locally but think globally. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:1472–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda A, Dong Y, Noda K, Saito W, Ishida S. 2017. Advanced glycation endproducts link inflammatory cues to upregulation of galectin-1 in diabetic retinopathy. Sci Rep 7:16168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazuhiro K, Harada T, Jike T, Tsuboi I, Aizawa S. 2018. Long-term hypoxic tolerance in murine cornea. High Alt Med Biol 19:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehasse A, Rich CB, Lee A, McComb ME, Costello CE, Trinkaus-Randall V. 2013. Epithelial wounds induce differential phosphorylation changes in response to purinergic and EGF receptor activation. Am J Pathol 183:1841–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Choi JY, Park SM, Rho CR, Cho KJ, Jo SA. 2017. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Vatalanib, inhibits proliferation and migration of human pterygial fibroblasts. Cornea 36:1116–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klyce SD. 1981. Stromal lactate accumulation can account for corneal oedema osmotically following epithelial hypoxia in the rabbit. J Physiol 321:49–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, Garcia AJ, Mould AP, Humphries MJ, Zhu C. 2009. Demonstration of catch bonds between an integrin and its ligand. J Cell Biol 185:1275–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, Li Z, Parks WM, Dumbauld DW, Garcia AJ, Mould AP, Humphries MJ, Zhu C. 2013. Cyclic mechanical reinforcement of integrin-ligand interactions. Mol Cell 49:1060–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio A, Perez-Jimenez R, Liu R, Roca-Cusachs P, Fernandez JM, Sheetz MP. 2009. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science 323:638–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Derricks K, Minns M, Ji S, Chi C, Nugent MA, Trinkaus-Randall V. 2014. Hypoxia-induced changes in Ca(2+) mobilization and protein phosphorylation implicated in impaired wound healing. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 306:C972–C985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Karamichos D, Onochie OE, Hutcheon AEK, Rich CB, Zieske JD, Trinkaus-Randall V. 2018. Hypoxia modulates the development of a corneal stromal matrix model. Exp Eye Res 170:127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubimov AV, Huang ZS, Huang GH, Burgeson RE, Miner JH, Gullberg D, Ninomiya Y, Sado Y, Kenney MC. 1998. Human corneal epithelial basement membrane and integrin alterations in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. J Histochem Cytochem 46:1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Wang L, Dai W, Lu L. 2010. Effect of hypoxic stress-activated Polo-like kinase 3 on corneal epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51:5034–5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahelková G, Korynta J, Moravová A, Novotná J, Vytásek R, Wilhelm J. 2008. Changes of extracellular matrix of rat cornea after exposure to hypoxia. Physiol Res 57:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris EA, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. 2013. Hypoxia-induced collagen crosslinking as a mechanism for enhancing mechanical properties of engineered articular cartilage. Osteoarthr Cartil 21:634–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay TB, Hjortdal J, Priyadarsini S, Karamichos D. 2017. Acute hypoxia influences collagen and matrix metalloproteinase expression by human keratoconus cells in vitro. PLoS One 12:e0176017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara NA, Chan JS, Han SC, Polse KA, McKenney CD. 1999. Effects of hypoxia on corneal epithelial permeability. Am J Ophthalmol 127:153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minns MS, Trinkaus-Randall V. 2016. Puringeric signaling in corneal wound healing: a tale of 2 receptors. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 32: 498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsi M, Hong Z, Costello CE, Nugent MA. 2006. Heparin-mediated conformational changes in fibronectin expose vascular endothelial growth factor binding sites. Biochemistry 45:10319–10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan PB, Brennan NA, Maldonado-Codina C, Quhill W, Rashid K, Efron N. 2010. Central and peripheral oxygen transmissibility thresholds to avoid corneal swelling during open eye soft contact lens wear. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 92:361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder GL, Huang MM, Waterston RH, Barstead RJ. 1996. Talin requires beta-integrin, but not vinculin, for its assembly into focal adhesion-like structures in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell 7:1181–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Moreno M, Jamora C, Fuchs E. 2003. Sticky business: orchestrating cellular signals at adherens junctions. Cell 112:535–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillip W, Speicher L, Humpel C. 2000. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in inflamed and vascularized human corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41:2514–2522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren R, Hutcheon AE, Guo XQ, Saeidi N, Melotti SA, Ruberti JW, Zieske JD, Trinkaus-Randall V. 2008. Human primary corneal fibroblasts synthesize and deposit proteoglycans in long-term 3-D cultures. Dev Dyn 237:2705–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GCK, Critchley DR. 2009. Structural and biophysical properties of the integrin-associated cytoskeletal protein talin. Biophys Rev 1:61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DM. 2013. The effects of silicone hydrogel lens wear on the corneal epithelium and risk for microbial keratitis. Eye Contact Lens 39:67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sady C, Khosrof S, Nagaraj R. 1995. Advanced Maillard reaction and crosslinking of corneal collagen in diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 214:793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safvati A, Cole N, Hume E, Willcox M. 2009. Mediators of neovascularization and the hypoxic cornea. Curr Eye Res 34:501–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salhiyyah K, Sarathchandra P, Latif N, Yacoub MH, Chester AH. 2017. Hypoxia-mediated regulation of the secretory properties of mitral valve interstitial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 313:H14–H23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S, Law A, Law S. 2017. Chronic pesticide exposure and consequential keratectasia & corneal neovascularisation. Exp Eye Res 164:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarver MD, Polse KA, Baggett DA. 1983. Intersubject difference in corneal edema response to hypoxia. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 60:128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sazonova OV, Isenberg BC, Herrmann J, Lee KL, Purwada A, Valentine AD, Buczek-Thomas JA, Wong JY, Nugent MA. 2015. Extracellular matrix presentation modulates vascular smooth muscle cell mechanotransduction. Matrix Biol 41:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller HB, Hermann MR, Polleux J, Vignaud T, Zanivan S, Friedel CC, Sun Z, Raducanu A, Gottschalk KE, Thery M, et al. 2013. Beta1- and alphav-class integrins cooperate to regulate myosin II during rigidity sensing of fibronectin-based microenvironments. Nat Cell Biol 15:625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Eguchi Y, Kamiike W, Itoh Y, Hasegawa J, Yamabe K, Otsuki Y, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. 1996. Induction of apoptosis as well as necrosis by hypoxia and predominant prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. Cancer Res 56:2161–2166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smelser GK, Ozanics V. 1952. Importance of atmospheric oxygen for maintenance of the optical properties of the human cornea. Science 115:140–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp MA. 2006. Corneal integrins and their functions. Exp Eye Res 83:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teranishi S, Kimura K, Kawamoto K, Nishida T. 2008. Protection of human corneal epithelial cells from hypoxia-induced disruption of barrier function by keratinocyte growth factor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49:2432–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomasy SM, Raghunathan VK, Winkler M, Reilly CM, Sadeli AR, Russell P, Jester JV, Murphy CJ. 2014. Elastic modulus and collagen organization of the rabbit cornea: epithelium to endothelium. Acta Biomater 10:785–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyberg J, Hultgårdh-Nilsson A. 1994. Fibronectin and the basement membrane components laminin and collagen type IV influence the phenotypic properties of subcultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells differently. Cell Tissue Res 276:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CE, Glenney JR, Burridge K. 1990. Paxillin: a new vinculin-binding protein present in focal adhesions. J Cell Biol 111:1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Yamamoto N, Petroll WM, Cavanagh HD, Jester JV. 2005. Internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by lipid rafts in contact lens-wearing rabbit and cultured human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46:1348–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Yamamoto N, Jester JV, Petroll MW, Cavanagh HD. 2006a. Prolonged hypoxia induces lipid raft formation and increases Pseudomonas internalization in vivo after contact lens wear and lid closure. Eye Contact Lens 32:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Yamamoto N, Petroll WM, Jester JV, Cavanagh HD. 2006b. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa internalization after contact lens wear in vivo and in serum-free culture by ocular surface cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47:3430–3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonemura S, Wada Y, Watanabe T, Nagafuchi A, Shibata M. 2010. Alpha-catenin as a tension transducer that induces adherens junction development. Nat Cell Biol 12:533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidel-Bar R, Milo R, Kam Z, Geiger B. 2007. A paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation switch regulates the assembly and form of cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Sci 120:137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi T, Mowrey-Mckee M, Pier GB. 2004. Hypoxia increases corneal cell expression of CFTR leading to increased Psuedomonas aeruginosa binding, internalization, and initiation of inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45:4066–4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Gipson IK. 1986. Protein synthesis during corneal epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 27:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Higashijima SC, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Gipson IK. 1987. Biosynthetic responses of the rabbit cornea to a keratectomy wound. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 28:1668–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Bukusoglu G, Gipson IK. 1989. Enhancement of vinculin synthesis by migrating stratified squamous epithelium. J Cell Biol 109:571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Takahashi H, Hutcheon AEK, Dalbone AC. 2000. Activation of epidermal growth factor receptor during corneal epithelial migration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41:1346–1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.