Abstract

Background

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a severe and debilitating condition. Several pharmacological interventions have been proposed with the aim to prevent or mitigate it. These interventions should balance efficacy and tolerability, given that not all individuals exposed to a traumatic event will develop PTSD. There are different possible approaches to preventing PTSD; universal prevention is aimed at individuals at risk of developing PTSD on the basis of having been exposed to a traumatic event, irrespective of whether they are showing signs of psychological difficulties.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological interventions for universal prevention of PTSD in adults exposed to a traumatic event.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trial Register (CCMDCTR), CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, two other databases and two trials registers (November 2020). We checked the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews. The search was last updated on 13 November 2020.

Selection criteria

We included randomised clinical trials on adults exposed to any kind of traumatic event. We considered comparisons of any medication with placebo or with another medication. We excluded trials that investigated medications as an augmentation to psychotherapy.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methodological procedures. In a random‐effects model, we analysed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RR) and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial/harmful outcome (NNTB/NNTH). We analysed continuous data as mean differences (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMD).

Main results

We included 13 studies which considered eight interventions (hydrocortisone, propranolol, dexamethasone, omega‐3 fatty acids, gabapentin, paroxetine, PulmoCare enteral formula, Oxepa enteral formula and 5‐hydroxytryptophan) and involved 2023 participants, with a single trial contributing 1244 participants. Eight studies enrolled participants from emergency departments or trauma centres or similar settings. Participants were exposed to a range of both intentional and unintentional traumatic events. Five studies considered participants in the context of intensive care units with traumatic events consisting of severe physical illness. Our concerns about risk of bias in the included studies were mostly due to high attrition and possible selective reporting. We could meta‐analyse data for two comparisons: hydrocortisone versus placebo, but limited to secondary outcomes; and propranolol versus placebo. No study compared hydrocortisone to placebo at the primary endpoint of three months after the traumatic event.

The evidence on whether propranolol was more effective in reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms compared to placebo at three months after the traumatic event is inconclusive, because of serious risk of bias amongst the included studies, serious inconsistency amongst the studies' results, and very serious imprecision of the estimate of effect (SMD ‐0.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.61 to 0.59; I2 = 83%; 3 studies, 86 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). No study provided data on dropout rates due to side effects at three months post‐traumatic event. The evidence on whether propranolol was more effective than placebo in reducing the probability of experiencing PTSD at three months after the traumatic event is inconclusive, because of serious risk of bias amongst the included studies, and very serious imprecision of the estimate of effect (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.92; 3 studies, 88 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). No study assessed functional disability or quality of life.

Only one study compared gabapentin to placebo at the primary endpoint of three months after the traumatic event, with inconclusive evidence in terms of both PTSD severity and probability of experiencing PTSD, because of imprecision of the effect estimate, serious risk of bias and serious imprecision (very low‐certainty evidence). We found no data on dropout rates due to side effects, functional disability or quality of life.

For the remaining comparisons, the available data are inconclusive or missing in terms of PTSD severity reduction and dropout rates due to adverse events. No study assessed functional disability.

Authors' conclusions

This review provides uncertain evidence only regarding the use of hydrocortisone, propranolol, dexamethasone, omega‐3 fatty acids, gabapentin, paroxetine, PulmoCare formula, Oxepa formula, or 5‐hydroxytryptophan as universal PTSD prevention strategies. Future research might benefit from larger samples, better reporting of side effects and inclusion of quality of life and functioning measures.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Hydrocortisone; Hydrocortisone/therapeutic use; Paroxetine; Psychotherapy; Psychotherapy/methods; Quality of Life; Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic; Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic/psychology

Plain language summary

Medicines for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Why is this review important?

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a severe and disabling condition which may develop in people exposed to traumatic events. Such events can have long‐lasting negative repercussions on the lives of those who have experienced them, as well as on the lives of loved ones.

Research has shown that there are some alterations in how the brain works in people with PTSD. Some researchers have thus proposed using medicines to target these alterations soon after a traumatic event, as a way to prevent the development of PTSD. However, the majority of people who experience a traumatic event will not develop PTSD. Therefore, medicines that can be given soon after exposure to a traumatic event must be carefully evaluated for their effectiveness, including balancing the risk of side effects against the risk of developing PTSD.

Who will be interested?

‐ People exposed to traumatic events and their family, friends, and loved ones

‐ Professionals working in mental health

‐ Professionals working in traumatology and emergency medicine

‐ People caring for victims of traumatic experiences and veterans of the armed forces

What questions did this review try to answer?

For people exposed to a traumatic event, whether or not they have psychological symptoms, are some medicines more effective than other medicines or placebo (dummy pills) in:

‐ reducing the severity of symptoms of PTSD?

‐ reducing the number of people stopping the medication because of side effects?

‐ reducing the probability of developing PTSD?

Which studies were included?

We searched scientific databases for studies in which participants were randomly assigned to a medicine with the aim of preventing PTSD and its symptoms or reducing severity. We included studies published up until November 2020. We selected studies in adults who had experienced any kind of traumatic event, and which provided treatment, regardless of whether or not the participants had psychological symptoms.

We included 13 studies, with a total of 2023 participants. One study alone contributed 1244 participants. The studies took place in different settings and involved people exposed to a wide range of traumatic events. Some studies took place in emergency departments and considered people whose trauma resulted from intentional harm or unintentional harm. Other studies focused on life‐threatening illness as the source of trauma, including major surgeries or being admitted to intensive care units. The medicines most commonly given to participants in the studies included: hydrocortisone (which reduces the body's immune response), propranolol (used to treat heart problems and anxiety, amongst other conditions), and gabapentin (a medicine primarily used to treat seizures and nerve pain).

What did the evidence tell us?

We found four trials comparing hydrocortisone to placebo. These trials did not report how participants were doing at three months after a traumatic event, a time point that is usually useful to assess the evolution of PTSD symptoms.

We found very low‐certainty evidence about propranolol compared to placebo three months after a traumatic event. This evidence does not tell us whether or not propranolol is more effective than placebo in reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms and the probability of developing PTSD. We did not find evidence on the probability of people stopping the medication because of side effects, quality of life, or functional disability (a measure of how much one’s life is limited by symptoms).

We found very low‐certainty evidence about gabapentin compared to placebo three months after a traumatic event. This evidence does not tell us whether or not gabapentin is more effective than placebo in reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms and the probability of developing PTSD. We did not find evidence on the probability of people stopping the medication because of side effects, quality of life, or functional disability.

We found studies on additional medicines, for which information about the reduction of PTSD severity and the probability of people stopping the medication was either inconclusive or missing.

None of the included studies measured the functional disability of participants.

What should happen next?

The evidence we found does not support the use of any medicines for the prevention of PTSD in people exposed to a traumatic event, regardless of whether or not they have psychological symptoms. More higher quality studies involving more people are needed to draw conclusions about these treatments.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Hydrocortisone compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Hydrocortisone compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | |||

| Patient or population: adults (aged 18 and older) exposed to a traumatic event Setting: N/A Intervention: hydrocortisone Comparison: placebo | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| PTSD severity at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| Dropout due to adverse events at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ |

| PTSD rate at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| Functional disability at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ |

| Quality of life at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ |

| PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

Summary of findings 2. Propranolol compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Propranolol compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults (aged 18 and older) exposed to a traumatic event Setting: emergency departments and surgical trauma center Intervention: propranolol Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with propranolol | |||||

| PTSD severity at 3 months assessed with: CAPS (Hoge 2012; Pitman 2002), PCL‐C (Stein 2007) | See comment | SMD 0.51 lower (1.61 lower to 0.59 higher) | ‐ | 86 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | A general rule for interpreting SMDs is that 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect and 0.8 a large effect |

| Dropout due to adverse events at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| PTSD rate at 3 months assessed with: CAPS (Hoge 2012), DSM‐IV criteria (Pitman 2002), CIDI (Stein 2007) | Study population | RR 0.77 (0.31 to 1.92) | 88 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,d | ||

| 204 per 1000 | 157 per 1000 (63 to 392) | |||||

| Functional disability at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Quality of life at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CAPS: Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale; CI: confidence interval; CIDI: Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview; DSM‐IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐4th Edition; PCL‐C: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist ‐ Civilian version; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; RCTs: randomised controlled trials; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias. One study had a high attrition rate (Pitman 2002). Another study had imbalanced attrition rates between the intervention arms (Stein 2007). bDowngraded one level as the 95% confidence interval of one study overlaps minimally with those of the other two cDowngraded two levels for imprecision as the total number of participants is fewer than 400 and the confidence interval includes both appreciable harm and benefit dDowngraded two levels as the optimal information size is not met and the confidence interval includes both appreciable benefit and harm

Summary of findings 3. Gabapentin compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Gabapentin compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults (aged 18 and older) exposed to a traumatic event Setting: surgical trauma center Intervention: gabapentin Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with gabapentin | |||||

| PTSD severity at 3 months assessed with: PCL‐C | One study reports a GEE analysis of PCL‐C scores over the 4 months after the traumatic event of B = ‐0.48, SE= 0.85, ns | ‐ | (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ||

| Dropout due to adverse events at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| PTSD rate at 3 months assessed with: CIDI | Study population | RR 0.80 (0.18 to 3.59) | 26 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | ||

| 250 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 (45 to 898) | |||||

| Functional disability at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Quality of life at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CIDI: Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview; GEE: generalised estimating equations; ns: non‐significant; PCL‐C: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist ‐ Civilian version; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SE: standard error | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias as the included study has imbalanced attrition rates between the intervention arms bDowngraded two levels for imprecision as the total number of participants is fewer than 400 and the confidence interval includes both appreciable harm and benefit cDowngraded two levels as the optimal information size is not met and the confidence interval includes both appreciable benefit and harm

Background

Description of the condition

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a severe and disabling disorder which may develop in people exposed to traumatic events. Up to 80% of the adult population in the USA have been exposed to a traumatic event eligible for diagnosis of PTSD (Breslau 2012), and estimates are similar for Europe (De Vries 2009). Data from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative show that the 12‐month prevalence of PTSD is 1.1% and the lifetime prevalence is 3.9% (Karam 2014; Koenen 2017). Prevalence estimates rates are higher in displaced populations (Bogic 2015; Turrini 2017), and populations exposed to conflict (Steel 2009).

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5), traumatic events eligible for the diagnosis "include, but are not limited to, exposure to war as a combatant or civilian, threatened or actual physical assault, threatened or actual sexual violence, being kidnapped, being taken hostage, terrorist attack, torture, incarceration as a prisoner of war, natural or human‐made disasters, and severe motor vehicle accidents" (APA 2013). As stated by the DSM, this list is not exhaustive and many different traumatic events have proved capable of triggering PTSD. For instance, in recent years, there has been an increase in reports of PTSD in survivors of critical illness, with an estimated prevalence of 25% amongst this population (Wade 2013). With some limitations regarding the nature of the traumatic incident, witnessing a trauma, learning that a relative or close friend was exposed to trauma, or being exposed to aversive details about a trauma (as in the course of professional duties) may also precipitate PTSD (APA 2013).

The majority of individuals exposed to traumatic experiences do not develop PTSD. The likelihood of developing PTSD is associated with a number of pre‐, peri‐, and post‐traumatic factors (Bisson 2007; Qi 2016), such as: history of a psychiatric disorder; sex (females are more vulnerable than males); low socioeconomic status; belonging to a minority; history of previous trauma; genetic endowment and epigenetic regulation; impaired executive functioning and higher emotional reactivity (Aupperle 2012; Guthrie 2005); the severity of the trauma itself; the perceived threat to life; whether the event or the intent to harm was intentional or unintentional; peri‐traumatic emotions and dissociation (Ozer 2003); and the lack of social support and subsequent life stress (e.g. inability to work as a result of the event) (Brewin 2000).

Individuals who develop PTSD following a trauma may experience a wide range of symptoms, which are presented in four categories in the DSM‐5 (APA 2013).

Re‐experiencing; for example, recurrent unwanted intrusive memories, distressing dreams, flashbacks, distress at re‐exposure.

Avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma behaviours; for example, the avoidance of distressing memories associated with the traumatic event or avoidance of external reminders.

Negative alteration in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event; for example, impairment in recalling important aspects of the trauma, negative thoughts and assumptions about oneself or the world, negative beliefs about the causes or consequences of the traumatic event, diminished interest or participation in significant activities, feeling of detachment from others, inability to experience positive emotions.

Arousal symptoms; for example, hypervigilance, insomnia, irritability, reckless or self‐destructive behaviour, problems concentrating.

The development and maintenance of PTSD is most likely the product of an interaction of different factors. Although current evidence alone cannot explain the complexity underlying PTSD, it is clear that multiple and interconnected systems are involved (Kelmendi 2016; Koch 2014; Lee 2016; Pitman 2012), with the contribution of biological and psychological mechanisms (Besnard 2012; Nickerson 2013).

Description of the intervention

Interventions for preventing the development of PTSD can be divided into two main categories: psychological and pharmacological. Although this review focuses on the latter, several other publications have examined and reviewed the former (Forneris 2013; Kearns 2012; Qi 2016; Roberts 2019; Rose 2002).

With respect to pharmacological interventions, drugs belonging to different classes have been examined by means of randomised clinical trials, and some reviews have already been published, including a previous Cochrane Review (Amos 2014; Astill Wright 2019; Sijbrandij 2015). It should be noted that the mechanisms underlying the onset of the disorder are likely to be different from the ones maintaining it, and therefore some of the interventions proposed to prevent the onset of the disorder differ from the interventions for treatment.

Glucocorticoids are synthetic analogues of hormones involved in immunity and stress response. They can be administered in several ways, including oral, intravenous, and intramuscular administration. Depending on the purpose, a treatment course can last from a single shot to several days. The trials testing steroids for PTSD prevention have used either single dose administration or a course of a few days in individuals with severe physical conditions (Delahanty 2013; Schelling 2001; Weis 2006). Hydrocortisone, along with some other steroids, is also included in the World Health Organization (WHO) Model List of Essential Medicines (WHO 2017), and is therefore expected to be commonly available in several global contexts. Propranolol is a beta blocker, primarily used for long‐term treatment in cardiology. Some trials have tested it on a three‐week time span for PTSD prevention (Hoge 2012; Pitman 2002; Stein 2007). Propranolol is also included in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (WHO 2017). A small trial has investigated a short course of temazepam, which belongs to the class of benzodiazepines (common anxiolytic drugs), but found an increase of PTSD onset rather than a decrease (Mellman 2002). Recently, there is growing interest in oxytocin, an endogenous hormone involved in sociability and stress regulation (Qi 2016), and an early trial investigated oxytocin administered in a single intranasal dose (Van Zuiden 2017). Escitalopram is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant, and although this class has yielded good results in PTSD treatment, there is uncertainty about whether SSRIs are effective in reducing the incidence of PTSD (Shalev 2012; Zohar 2017a). Gabapentin, an anticonvulsant with anxiolytic properties and a benign side effect profile, has been included in trials of PTSD prevention (Stein 2007). Opioids have been proposed too; for example, a large retrospective study on American soldiers with combat injury found an association between morphine administration and lower PTSD incidence (Holbrook 2010).

How the intervention might work

The biological mechanisms underlying PTSD provide several possible targets for the pharmacological prevention of PTSD. Different rationales can potentially explain the efficacy of the investigated drugs.

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are involved in both hormonal stress response and memory formation. The hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal (HPA) axis has long been a focus in PTSD investigations, and a role for hydrocortisone in facilitating extinction learning has been hypothesised (Hruska 2014). In a rodent model, a negative association has been found between a high dose of steroids and prevalence of PTSD‐like behaviour in rats exposed to predator scent stress (Cohen 2008), and consistent results were found in a human study (Zohar 2011). There is also epidemiologic evidence that lower urinary cortisol levels in the immediate aftermath of the trauma are associated with increased likelihood of future PTSD symptoms (Delahanty 2000; McFarlane 1997).

Beta blockers

A role for adrenaline in the formation of traumatic memories has long been postulated (Pitman 1989; Ressler 2020). It has been argued that a surge in adrenaline concentration, in conjunction with trauma, results in a strong emotional memory and fear conditioning that could prime PTSD. Later human studies supported a role for the beta adrenergic system in memory storing and in the enhanced memories associated with emotional arousal (Cahill 1994; Southwick 1999), and for propranolol to limit this process (Reist 2001).

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are known for reducing arousal and decreasing distress. They have amnesic properties as well, mostly inhibiting memory consolidation by impairing long‐term episodic storage (Barbee 1993). Despite this, no clinical research has found a positive effect for benzodiazepines in the management of traumatic stress symptoms (Howlett 2016).

Opioids

Studies on rodents have found retrograde amnesia properties for morphine, and a possible mechanism for that has been proposed via decreasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate or activating N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the hippocampus (McNally 2003). Human observational studies support a protective effect for morphine (Bryant 2009; Mouthaan 2015).

Oxytocin

A possible role for oxytocin in the prevention of PTSD is quite a recent approach, which has been proposed on a dual assumption theory: a reduction in the amygdala activation and an increase in the activation of the social reward brain areas (Olff 2010). Behavioural data on rodents seem to confirm a plausible role for oxytocin in mitigating the behavioural response to stress (Cohen 2010).

SSRIs

SSRI antidepressants are generally considered the first‐line pharmacological treatment for PTSD (ISTSS 2018; NICE 2018; Stein 2006), and might thereby have a putative role in the prevention of the disorder. SSRIs enhance serotonergic neurotransmission by inhibiting the re‐uptake of serotonin from the synapsis as mediated by the SERT serotonin transporter (Leonard 2000). Further downstream mechanisms are likely responsible for the beneficial effects of SSRIs, as these effects develop only after a few weeks of treatment. An increased expression of the specific downstream genes is currently supposed to induce dendritic spine formation, synaptogenesis, and neurogenesis (Licznerski 2013; Santarelli 2003).

Mood stabilisers/anticonvulsants

As for SSRIs, mood stabilisers/anticonvulsants might have a putative role in PTSD prevention, considering their employment as adjuvant/second‐line treatment for anxiety disorders (Van Ameringen 2004). A trial of gabapentin has been reported in a previous meta‐analysis of PTSD prevention (Stein 2007). Gabapentin administration increases the release of the neurotransmitter GABA from brain glial cells (Lydiard 2003). Imbalances in the GABAergic system have been reported in people with PTSD and other anxiety disorders (Meyerhoff 2014).

Omega‐3 fatty acid compounds

Given their ability to promote neurogenesis in the hippocampus ‐ a key area in memory consolidation and fear maintenance ‐ a role has been proposed for omega‐3 fatty acids in PTSD prevention (Matsuoka 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

PTSD represents a heavy burden for the people affected, those around them, health systems, and society. Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys showed a mean duration of symptoms of about six years. This time length was greatly influenced by the type of traumatic event: from about one year for natural disasters, up to 13 years for war combat‐related traumatic events (Kessler 2017). Moreover, PTSD is associated with poor general health status and unemployment (Zatzick 1997). Most of the evidence focuses on psychosocial intervention, amongst which trauma‐focused and exposure‐based therapies are the most promising ones. However, many of the studies are restricted by small sample sizes and methodological limitations (Birur 2017; Bisson 2021).

Despite knowledge of biological and clinical risk factors for PTSD and the various predictive strategies being researched (e.g. supervised machine learning (Galatzer‐Levy 2014; Karstoft 2015; Kessler 2014)), in clinical practice there is currently no effective way to predict who will develop PTSD after a traumatic experience. The biological features of PTSD provide several possible targets for the prevention of PTSD, and encouraging results were found in previous meta‐analyses of pharmacotherapy for PTSD prevention (Amos 2014; Sijbrandij 2015).

New trials on PTSD pharmacological prevention have now been published. Additionally, the Amos 2014 and Sijbrandij 2015 reviews considered together two different approaches: universal prevention (people exposed to a traumatic event) and indicated prevention (people exposed to a traumatic event and showing early symptoms). Although it would be valuable to have effective interventions for the prevention of PTSD, the risk‐to‐benefit ratio needs to be carefully assessed, as drugs will entail possible side effects for all of those receiving them, and not all of the individuals exposed to a traumatic event will develop PTSD.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological interventions for universal prevention of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults exposed to a traumatic event.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We have included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing one medication with placebo or one medication with another. We have considered trials for inclusion irrespective of language or publication status. We found no cross‐over trials, for which we had planned to consider the first randomised phase only.

Types of participants

Individuals

We have included trials in individuals with both of the following characteristics.

History of any traumatic event.

Aged 18 and older.

We have excluded studies targeting symptomatic patients at baseline, as these studies will be included in a second parallel review on early interventions (i.e. indicated prevention of PTSD) (Bertolini 2020), whilst the present review is on universal prevention.

Setting

We have considered trials performed in any type of setting.

Subset data

We planned to include trials in which only a portion of the sample met the above criteria, provided that the relevant data could be gained from the study report or by contacting the authors, and that the effect of randomisation was not affected by doing so. We did not find studies that required this treatment.

Types of interventions

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5) regards the three months from the trauma as a relevant timeframe for symptom evolution (APA 2013). Thus, we included any pharmacological intervention administered with the intention to prevent the onset of PTSD or PTSD symptoms within such a timeframe. We set no restrictions regarding dose, duration, administration route of the intervention, nor on the presence of any co‐medication not related to PTSD prevention. We excluded trials that investigated medications as an augmentation to psychotherapy (e.g. cognitive enhancers), as those trials investigate a form of psychological prevention.

Based on our knowledge of the literature, we expected to find drugs from these pharmacological groups:

glucocorticoids;

beta blockers;

benzodiazepines;

opioids;

other hormones (oxytocin);

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs);

mood stabilisers/anticonvulsants; and

omega‐3 fatty acid compounds.

Types of comparison

We have included studies using placebo or any active pharmacological agent as comparison. We have not considered studies comparing pharmacological interventions with only psychosocial interventions (i.e. with no other pharmacological or placebo arm). We have included studies meeting the above criteria, irrespective of whether they reported any of our outcomes of interest.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

PTSD severity (continuous): using the mean score on a validated rating scale such as the Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (Blake 1995), or the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) (Weathers 2001), the Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (WHO 1997), or any other validated rating scale to assess symptom severity.

Dropouts due to adverse events (dichotomous): we considered the number of participants who left the assigned arms early due to side effects, out of the number of randomised individuals.

Secondary outcomes

PTSD rate (dichotomous): we considered PTSD rates, as measured by a DSM‐defined measure or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO 1992) diagnosis made with a clinician‐administered measure.

Depression severity (continuous): we considered the severity of depressive symptoms, using the score on validated scales such as the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery 1979), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton 1960), the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961), or any other validated scale.

Anxiety severity (continuous): we considered the severity of the anxiety symptoms using the score on validated scales such as the Covi Anxiety Scale (CAS) (Covi 1984), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck 1988), the Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger 1970), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton 1959), or any other validated scale.

Functional disability (continuous): we considered validated scales such as the Sheehan Disability Scale (Sheehan 1996), or any other validated scale.

Quality of life (continuous): we considered validated scales such as the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36) (Ware 1992), or any other validated scale to assess quality of life.

Dropout for any reason (dichotomous): we considered the number of participants who left the assigned arms early for any reason, out of the number of randomised individuals.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

The hierarchy of outcome measure scales has followed the order above. We expected that clinician‐administered scales would more frequently be employed. In the case of trials employing validated scales different from the ones mentioned above, for homogeneity reasons, we have given priority to clinician‐administered scales over self‐reported ones.

Timing of outcome measures

We have synthesised data at three months after exposure to the traumatic event, operationalised as the time point closest to three months of follow‐up (from two to four months of follow‐up). In addition, we have included data at study endpoint as a secondary time point.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders (CCMD) maintained a specialised register of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the CCMDCTR, to June 2016. This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety and depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm, and other mental disorders within the scope of CCMD. The CCMDCTR is a partially studies‐based register, with more than 50% of the reference records tagged to 12,600 study records, individually coded for participant, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO). Reports of trials for inclusion in the register were collated from (weekly) generic searches of MEDLINE (1950‐), Embase (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐), quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials were also sourced from international trial registries, drug companies, handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on CCMD's website, with an example of the MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 1.

The CCMD trials register fell out of date with the relocation of the group from the University of Bristol to York University in June 2016.

Electronic searches

CCMDCTR studies and references register

We have cross‐searched the CCMDCTR studies and references register for condition alone, using the following terms: (PTSD or posttrauma* or post‐trauma* or "post trauma*" or "combat disorder*" or "stress disorder*") (all years to June 2016).

Biomedical database search

To account for the period after the CCMDCTR fell out of date, the CCMD's information specialists conducted additional searches on the following bibliographic databases, using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate to each resource (see Appendix 2 for details of the search strategies).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 11) in the Cochrane Library (June 2016 to 13 November 2020).

MEDLINE Ovid (June 2016 to 13 November 2020).

Embase Ovid (June 2016 to 13 November 2020).

PsycINFO Ovid (June 2016 to 13 November 2020).

Published International Literature On Traumatic Stress (PILOTS) EBSCO (June 2016 to 13 November 2020).

The search was for all reviews on PTSD within the scope of CCMD. After de‐duplication, at least two members of the CCMD editorial base staff screened the search results in Covidence, according to the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Any RCT for the treatment of PTSD (irrespective of intervention, age group or comorbidity)

Any RCT which might be seen as a PTSD prevention study

Any RCT for critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) (simulated crises not included)

Any RCT for debriefing after psychological trauma or any stress resilience studies

Any controlled clinical trial (CCT) where the treatment allocation was ambiguous

Corrigendums, errors, retractions, or substantial comments relating to the above

Exclusion criteria

All systematic reviews and meta‐analyses

Healthy populations

Simulated crises (e.g. for staff training in accident and emergency)

RCTs which fall outside the scope of CCMD, such as serious mental illness (schizophrenia), borderline personality disorder, alcohol use disorder (e.g. brief alcohol intervention in accident and emergency department), smoking cessation, traumatic brain injury, fibromyalgia (unless the comorbidity clearly fell within the scope of the search and was an outcome of the trial)

A first search was run in March 2018, with an update in March 2019, and a final update on 13 November 2020 (see Appendix 2).

Searching other resources

We have checked the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We imported all records obtained via the electronic search, plus the handsearch, into EndNote software in order to remove all duplicates. Two review authors (FB and LR) worked independently and in duplicate. We screened all potentially eligible papers' titles and abstracts and coded them as 'retrieve' or 'not retrieve'; obtained the full‐text publication of the records coded as 'retrieve'; and assessed inclusion and exclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreements through discussion or, if necessary, by involving a third review author (NM).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (FB and LR), working independently and in duplicate, extracted data from the included trials. We used a data extraction sheet developed in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (hereafter referred to as the Cochrane Handbook), section 7.5 (Higgins 2011a). We collected the following data.

First author, year of publication, journal, source of funding, notable conflict of interest of authors, total duration of study, number of centres and location.

Methodological characteristics of the trial: randomisation, blinding, allocation concealment, number of arms, follow‐up time points.

Sample characteristics: study setting, type of trauma, criteria for enrolling, age, gender, number of participants randomised to each arm, history of previous traumatic events.

Intervention details: time from the traumatic event to treatment, medication employed, period over which it was administered, dosage range, mean dosage prescribed.

Outcomes: time points of outcome assessment, instrument used to assess PTSD symptoms, instrument used to assess PTSD rate, instrument used to assess depression symptoms, instrument used to assess anxiety, instrument used to assess functional disability, outcome measure employed by original trial (primary and secondary), data for continuous (means and standard deviation or standard error if standard deviation was not provided) and dichotomous variables of interest, total number of dropouts, number of dropouts due to pharmacological side effects, whether the data reflected an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) model, methods of estimating the outcome for participants who dropped out (last observation carried forward (LOCF) or completer/observed case (OC) approach, or other).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FB and LR), working independently and in duplicate, assessed the risk of bias for each study according to the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011b). We resolved any disagreements through discussion, or if necessary, by involving a third review author (NM). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personal (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other bias.

We assessed performance, detection, and attrition bias on a per outcome basis rather than per study. We have rated each source of bias as high, low or unclear, with reasons to justify the rating.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we calculated risk ratio (RR) estimates and their 95% confidence interval (CI). RRs are more easily interpreted than odds ratios (ORs) (Boissel 1999), and as clinicians may risk interpreting ORs as RRs (Deeks 2002), this may lead to an overestimation of the effect. We also calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial/harmful outcome (NNTB/NNTH).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we calculated the mean differences (MDs) and their 95% CI, where data were measured on the same scale. For studies that employed different scales, we have used standardised mean differences (SMDs). We gave preference to endpoint measures, considering the nature of the review (prevention) and that endpoint data are easier to interpret from a clinical point of view. In the case of reporting of change scores measures only, we had planned ‐ if sufficient data had been reported ‐ to convert change scores into endpoint data using standard formulas reported in the Cochrane Handbook (Deeks 2011), but this was unnecessary.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

We included no cross‐over trials in this review. For this design, we had planned to consider only the first phase from cross‐over trials, as the carryover effect cannot be excluded on a prevention measure, regardless of appropriate washout times.

Cluster‐randomised trials

We found no cluster‐randomised trial eligible for inclusion in this review. For eligible cluster‐RCTs which had not appropriately adjusted for the correlation between participants within clusters, we had planned to contact trial authors to obtain an estimate of the intracluster correlation (ICC), or to impute using estimates from the other included trials or from similar external trials. We planned to conduct a sensitivity analyses in the case of imputation of ICCs to examine the impact on estimates.

Multiple treatment group studies

We have compared each arm with placebo separately and included each pair‐wise comparison separately. In the case of pooling different interventions together, we had planned the following means to prevent 'double‐counting', in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook, section 16.5.4 (Higgins 2011c): in the case of dichotomous variables, to split the comparison group evenly amongst the intervention groups; in the case of continuous variables, to only divide the total number of participants and leave the mean and standard deviations (SDs) unchanged.

Dose‐ranging studies

We have not included studies with multiple arms with the same medication administered at different doses or for a different length of time. For these trials, we had planned to pool these intervention groups into a single one, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook, section 16.5.4 (Higgins 2011c).

Dealing with missing data

As a first measure, we tried to contact study investigators to obtain missing data. When this was unsuccessful, we employed the following approaches.

Dichotomous data

We planned to use ITT data analysed on a 'once randomised, always analysed' basis, and for studies that did not perform an ITT analysis, to assume a negative outcome (i.e. onset of PTSD) for individuals lost to follow‐up. However, given the high attrition rates of some trials and that none used ITT analyses, we felt that this approach risked being further distant from the true value. Therefore, we decided to consider the number of participants with the event divided by the number of analysed participants (i.e. 'observed cases'), and added a sensitivity analysis with the number of participants with the event divided by the number of randomised participants.

Continuous data

We used ITT data when reported, favouring multiple imputations or mixed‐effects models where different imputational strategies had been used. In the context of prevention, last observation carried forward (LOCF) provides the least conservative option and therefore observed cases (OC) were preferred. For studies not reporting ITT analyses, we have not imputed missing data for continuous outcomes, as this usually requires access to individual participant data.

Missing statistics

In the case of missing statistics, we had planned to calculate SDs when only P values, CIs, standard errors, and so on were reported, but this was not possible. We also planned to calculate the arithmetic mean of SDs of studies using the same scale of the one with the missing SDs (as in Furukawa 2006), but again this was not possible.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We have assessed heterogeneity by means of:

visual inspection of the overlap of the CIs for individual studies in the forest plot;

Chi2 test, with a P value set at 0.10;

I2 statistic: in accordance with the suggestion in the Cochrane Handbook, section 9.5.2 (Deeks 2011), we have followed a rough guide for interpretation as follows: 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity. We have also taken into account magnitude and direction of effects.

Assessment of reporting biases

We included fewer than 10 studies per outcome per comparison. If more than 10 studies had been included per primary outcome, we would have:

visually inspected the relative funnel plots, tested them for asymmetry, and investigated possible reasons for funnel plot asymmetry;

employed Egger's regression test (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

Methods for pair‐wise meta‐analysis

We have performed standard pair‐wise meta‐analysis with a random‐effects model for every comparison with at least two studies, using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We used a random‐effects model as we were expecting clinical heterogeneity. We have performed the pair‐wise comparison at individual medicine level (e.g. propranolol versus placebo) and planned a possible shift to drug class level if the number of studies was limited. We decided not to do so in the case of dexamethasone and hydrocortisone. Although both drugs are steroids, dexamethasone does not easily pass the blood‐brain barrier whilst hydrocortisone does.

Methods for network meta‐analysis

We had planned to perform a network meta‐analysis subject to feasibility. In consideration of the limited number of included studies and the lack of direct comparisons, we judged the network meta‐analysis infeasible.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to assess the impact on effectiveness of subgrouping by intervention, starting within 12 hours from the traumatic event and after 12 hours from the traumatic event. However, this was feasible for only one comparison, as most of the comparisons we found included only one study, or the reported start time of the intervention was insufficiently specific. To limit the risk of false positive through multiple testing, we applied the subgroup analysis to primary outcomes only. An additional planned subgroup considering the setting of the intervention (e.g. acute and emergency departments, surgery or intensive care units) was not feasible, because for each comparison, all of the included studies took place in the same setting.

Sensitivity analysis

We could not carry out the following additional pre‐planned sensitivity analyses due to lack of data: excluding studies at high risk of bias defined by unclear allocation concealment or unblinded outcome assessment; impact using ITT data versus completers data; and impact of excluding cluster‐RCTs.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We planned to present the results using a summary of findings table for each comparison. However, as we found nine comparisons, we considered this approach impractical. Instead, we prioritised those comparisons that are widely discussed in the literature and in previous guidelines (namely, hydrocortisone versus placebo, propranolol versus placebo, and gabapentin versus placebo) (ISTSS 2018; NICE 2018; Phoenix Australia 2020), as we expect these to be more relevant to decision makers. For comprehensiveness, we have reported summary of findings tables for the other comparisons in Additional tables.

The summary of findings tables considered the primary time point of three months after the traumatic event and these outcomes:

PTSD severity;

dropouts due to adverse events;

PTSD rate;

functional disability; and

quality of life.

We have used the five GRADE 'certainty assessment' domains (study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision) to assess the certainty of the evidence of the studies that provided data for the specific outcome. We have used GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT), and applied the methods and recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook, section 11.5 (Schünemann 2011). Two review authors (FB and TW) independently graded the certainty of the evidence. We resolved any disagreements through discussion or, if required, by consulting a third review author (NM). We have used footnotes to justify the downgrading of the evidence. We have noted comments to aid the reader, when suitable. We have categorised the certainty of the evidence as high (further research is not likely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect), moderate (further research is likely to have an important impact on the estimate of effect and may change it), low (further research is very likely to have an important impact on the estimate of effect and is likely to change it), or very low (estimate of effect is very uncertain).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

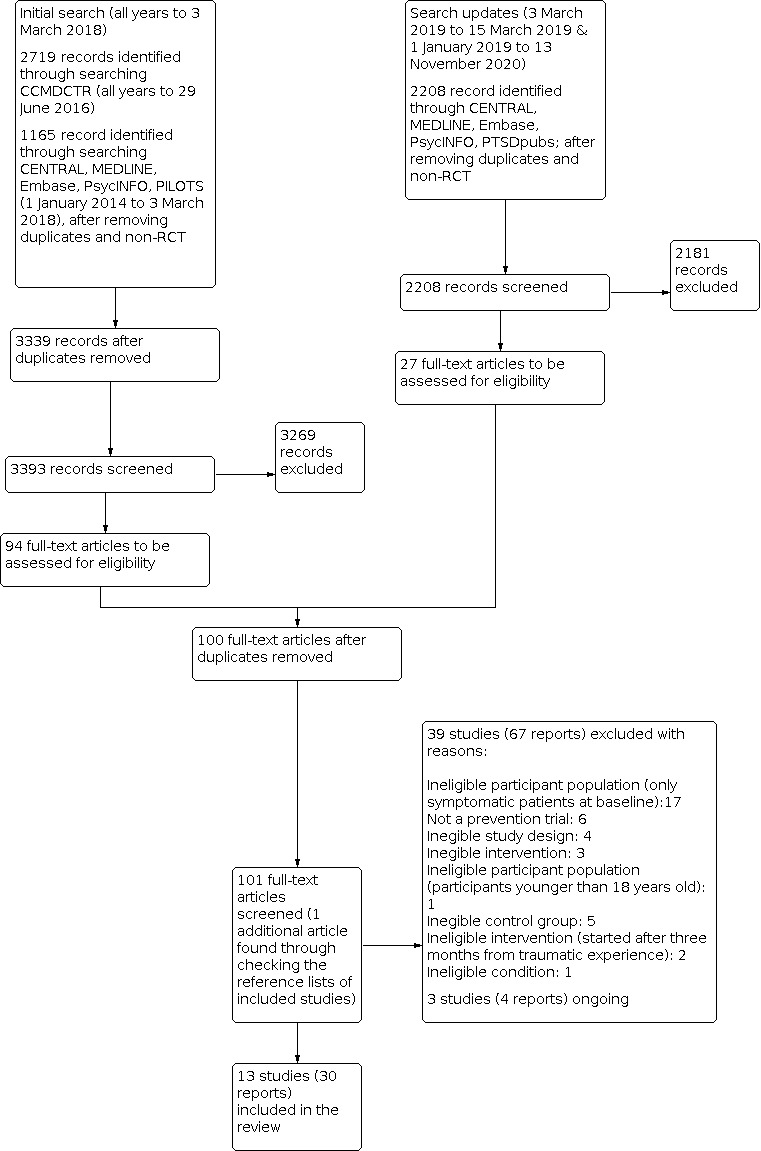

The initial search identified 3339 titles and abstracts, and an updated search identified an additional 2208 titles and abstracts (see Figure 1 for study flow diagram). We screened each title (and abstract if available) for eligibility. We inspected a total of 100 full‐text publications, and identified 16 studies (32 reports) eligible for inclusion in the review. Of these, three are ongoing studies, leaving 13 studies (29 reports) for inclusion in the review. Thirty‐nine studies were ineligible for this review; of these, 18 have been marked for inclusion in the parallel review on early, indicated pharmacological intervention (Bertolini 2020).

1.

PRISMA study flow chart

Included studies

Design

All of the included studies are RCTs. All of them compared one active intervention against placebo, with the exception of Stein 2007, which compared two active interventions and placebo, and Kagan 2015, which compared two different enteral formulas.

Participants, traumatic events, and setting

A total of 2023 participants were included, with one single study contributing 1244 participants (Kok 2016).

The studies considered individuals exposed to a wide range of traumatic events, reflecting different recruitment settings. Eight studies recruited participants from emergency departments (Hoge 2012; Pitman 2002), trauma centres (Borrelli 2019; Shaked 2019; Stein 2007), intensive care units (ICUs) caring for trauma patients (Kagan 2015; Matsuoka 2015), or burn centres (Orrey 2015). Participants were exposed to both intentional and unintentional traumatic events, including assault, work injuries, motor vehicle accidents, and burns. Five studies recruited participants from ICUs, with septic shock (Denke 2008; Schelling 2001), or after cardiac surgery (Kok 2016; Weis 2006); or on the basis of ICU admission for non‐surgical reasons (Tincu 2016).

Two studies were multicentric (Kok 2016; Orrey 2015), nine were single centre (Borrelli 2019; Hoge 2012; Kagan 2015; Matsuoka 2015; Schelling 2001; Shaked 2019; Stein 2007; Tincu 2016; Weis 2006), and two provided insufficient detail to determine how many centres were involved (Denke 2008; Pitman 2002). Five studies were conducted in the USA (Borrelli 2019; Hoge 2012; Orrey 2015; Pitman 2002; Stein 2007), three in Germany (Denke 2008; Schelling 2001; Weis 2006), two in Israel (Kagan 2015; Shaked 2019), one in the Netherlands (Kok 2016), one in Japan (Matsuoka 2015), and one in Romania (Tincu 2016).

Interventions

The trials considered nine active interventions. Five trials investigated intravenous glucocorticoids, with one on dexamethasone (Kok 2016), and four on hydrocortisone (Denke 2008; Schelling 2001; Shaked 2019; Weis 2006). Four trials investigated propranolol (Hoge 2012; Orrey 2015; Pitman 2002; Stein 2007), with one of these having an additional gabapentin arm (Stein 2007). One trial was on omega‐3 fatty acids (docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid) (Matsuoka 2015), one on paroxetine, an SSRI antidepressant (Borrelli 2019), one on 5‐hydroxytryptophan (Tincu 2016), and one on enteral nutrition formulas (Kagan 2015). In the included studies, dexamethasone was administered as a continuous infusion at 1 mg/kg body weight for 12 days (Kok 2016). Hydrocortisone was variably administered, with one study using a single bolus of 100 mg (Shaked 2019); one study using a 4‐day course, including 100 mg as initial loading dose followed by one day at 10 mg/hour and then tapering (Weis 2006); and two studies using courses of several days with either a fixed scheme of 50 mg every 6 hours for five days followed by progressive tapering in six days (Denke 2008), or a loading dose of 100 mg followed by continuous infusion of 0.18 mg/kg/hour for six days and later tapering after septic shock reversal (Schelling 2001). Propranolol administration schemes ranged from a 14‐day course with up to 120 mg daily (Stein 2007), to a 6‐week course with 240 mg daily for three weeks followed by a taper period (Orrey 2015). Gabapentin was administered to up to 1200 mg daily over a course of 14 days. The omega‐3 fatty acids dose consisted of 1470 mg of docosahexaenoic acid and 147 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid daily for 20 days (Matsuoka 2015). The dose of paroxetine was 20 mg with possible reduction to 10 mg for side effects or elderly participants (Borrelli 2019), and the 5‐hydroxytryptophan dose was 300 mg (Tincu 2016). The enteral formulas were administered so as to provide at least 80% of the energetic expenditure and were provided for the duration of participants' ICU stay, up to 28 days (Kagan 2015).

Outcome measures

Most of the studies assessed PTSD severity with either the CAPS (Hoge 2012; Matsuoka 2015; Pitman 2002), or PCL (Borrelli 2019; Kagan 2015; Stein 2007). Denke 2008 used the Post‐Traumatic Stress Symptom 10‐Question Inventory (PTSS‐10) questionnaire, whilst two other studies used a modified version of the PTSS‐10 validated for ICU patients (Schelling 2001; Weis 2006). Two studies used additional, different scales: the Post‐traumatic stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS) (Shaked 2019), and the Posttraumatic Symptom Scale‐Interview Version (PSS‐I) Orrey 2015).

Three studies used the CAPS to establish the presence of PTSD according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) criteria (Hoge 2012; Matsuoka 2015; Pitman 2002), whilst two other studies used other validated DSM‐IV‐based interviews (Borrelli 2019; Schelling 2001). The remaining studies used several different tools to establish the presence of PTSD: the CIDI PTSD (Stein 2007), a validated modified version of the PTSS‐10 questionnaire (Weis 2006), the PSS‐I (Orrey 2015), the PTSS‐10 (Denke 2008), and the Self‐Rating Inventory for PTSD (SRIP, a Dutch questionnaire consistent with the DSM‐IV criteria for PTSD) (Kok 2016).

Depression was assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) (Stein 2007), the MADRS (Matsuoka 2015), the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS‐SR) (Borrelli 2019), and an unspecified 'Depression scale' (Kagan 2015).

All the studies that assessed quality of life used the SF‐36 (Borrelli 2019; Denke 2008; Kok 2016; Matsuoka 2015; Weis 2006).

Timing of outcome assessment

Of the 13 included trials, only five assessed outcomes at three months (which is the review's primary time point, operationalised as between two and four months from the traumatic experience) (Borrelli 2019; Hoge 2012; Matsuoka 2015; Pitman 2002; Stein 2007). The timing of the studies' endpoints varied greatly, from two weeks (Tincu 2016), to 49 months (Schelling 2001), with three studies assessing the outcome only after one year (Denke 2008; Kok 2016; Schelling 2001).

Excluded studies

We excluded 39 studies from this review. About half were excluded because they restricted eligibility to participants experiencing psychological distress at baseline. These studies will be included in the parallel review (Bertolini 2020). We excluded five studies because the focus was not PTSD prevention (NCT00633685; Lijffijt 2019; Naylor 2013; Rabinak 2020; Takehiro 2014; Truppman Lattie 2020); five for lack of or inappropriate comparison arm (Matsumura 2011; Matsuoka 2010; Nishi 2012; Schelling 2004; Yang 2011); four for ineligible study design (Blaha 1999; Gelpin 1996; Mistraletti 2015; NCT02069366); five for ineligible intervention (including interventions started after three months from the traumatic event) (FDA 1999; Kaplan 2015; Nedergaard 2020; Treggiari 2009; Zoellner 2001); one for including participants under 18 years old (Stoddard 2011); and one study concerned an ineligible condition (NCT02505984).

Ongoing studies

We found three currently ongoing studies (McMullan 2020; NCT03997864; NCT04274361).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for further details.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Random sequence generation

Ten studies described in sufficient detail a strategy for randomisation; we judged these as low risk of bias (Borrelli 2019; Denke 2008; Kagan 2015; Kok 2016; Matsuoka 2015; Orrey 2015; Schelling 2001; Shaked 2019; Stein 2007; Weis 2006). The remaining three studies reported a random assignment to intervention but with insufficient detail to assess the validity of the method (Hoge 2012; Pitman 2002; Tincu 2016). Therefore, we assessed these as having an unclear risk of bias.

Allocation

Seven studies described procedures that clearly resulted in or implied the concealment of the randomisation list (Denke 2008; Kagan 2015; Kok 2016; Matsuoka 2015; Orrey 2015; Stein 2007; Weis 2006); we judged these as low risk of bias. Six studies did not describe the allocation process with sufficient detail to ensure that allocation concealment was in place (Borrelli 2019; Hoge 2012; Pitman 2002; Schelling 2001; Shaked 2019; Tincu 2016); we judged these as having an unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Ten studies reported blinding of participants (Borrelli 2019; Denke 2008; Hoge 2012; Kagan 2015; Kok 2016; Matsuoka 2015; Orrey 2015; Shaked 2019; Stein 2007; Weis 2006), and have been judged at low risk of bias. One study was designed as double‐blind, but trial authors raised a concern about the effectiveness of the blinding due to specific side effects that may have allowed the identification of the intervention (Pitman 2002). The reporting of another study was unclear about participants’ blinding, and if blinded, whether blinding was still in place at the time of assessment of PTSD outcomes (Schelling 2001). We judged these trials as having an unclear risk of bias. One study did not mention blinding in its reporting (Tincu 2016); we judged it to be at high risk of bias.

Eleven studies reported blinding of outcome assessors (Borrelli 2019; Denke 2008; Hoge 2012; Kok 2016; Matsuoka 2015; Orrey 2015; Pitman 2002; Schelling 2001; Shaked 2019; Stein 2007; Weis 2006). One study provided insufficient detail (Kagan 2015), and has been judged at unclear risk of bias. One study did not mention blinding in its reporting (Tincu 2016); we judged it to be at high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Only four studies reported low attrition rates for outcomes of interest (Hoge 2012; Matsuoka 2015; Orrey 2015; Weis 2006); we judged these as having a low risk of bias. Three studies provided insufficient detail to assess the attrition rate of intervention arms (Borrelli 2019; Shaked 2019; Tincu 2016); we assessed these as having an unclear risk of bias. We judged six studies to be at high risk of bias. For four of them, this was due to high (over 20%) or uneven attrition rates (Denke 2008; Kagan 2015; Pitman 2002; Stein 2007). Kok 2016 and Schelling 2001 assessed PTSD‐related outcomes in follow‐up studies of clinical trials in ICU patients. The trials had not originally planned for this, requiring additional informed consent and applying additional exclusion criteria post‐randomisation. Moreover, these assessments were performed some time after the original trials, and parts of the samples were lost due to death. We judged these studies to be at high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

Reporting bias could be excluded only for Matsuoka 2015, which we judged as having a low risk of bias. Eight studies lacked a published protocol or clinical trial registration entry finalised before the data were available (Borrelli 2019; Denke 2008; Hoge 2012; Pitman 2002; Shaked 2019; Stein 2007; Tincu 2016; Weis 2006); we judged these as having an unclear risk of bias. In the Orrey 2015 trial, some outcomes were changed whilst the trial was being carried out. Kok 2016 and Schelling 2001 did not plan PTSD‐related outcomes when the original trials were carried out, and the registration entry of Kagan 2015 did not report PTSD‐related outcomes. We judged these four trials as having a high risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not find additional concerns for seven studies (Borrelli 2019; Hoge 2012; Matsuoka 2015; Orrey 2015; Pitman 2002; Shaked 2019; Stein 2007), and rated them at low risk of bias. The reporting of PTSD‐related outcomes for three trials relied on conference abstracts only (Denke 2008; Kagan 2015; Tincu 2016); for this reason, we judged these as having an unclear risk of bias. We judged the three remaining studies to be at high risk of bias. Kok 2016 required additional informed consent after randomisation at a time when part of the sample (critically‐ill participants) was lost due to death, and consenting participants were analysed at various time lengths after the traumatic event. We felt that a high risk of bias was therefore appropriate for this study. The authors of Schelling 2001 raised the concern that the investigated intervention might have been effective due to differences in the inotropic support (catecholamines have a role in PTSD development, see How the intervention might work). Moreover, additional inclusion criteria were applied after randomisation for the PTSD outcomes. A difference in the inotropic support was present in Weis 2006 too. Participants had different courses of the underlying condition between intervention arms and this could mediate an effect on PTSD development. We felt that a judgement of high risk of bias was therefore appropriate for these studies too.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

See Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9 and Data and analyses.

1. Additional summary of findings table: dexamethasone compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Dexamethasone compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | |||

| Patient or population: adults (aged 18 and older) exposed to a traumatic event Setting: N/A Intervention: dexamethasone Comparison: placebo | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| PTSD severity at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| Dropout due to adverse events at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| PTSD rate at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| Functional disability at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| Quality of life at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

2. Additional summary of findings table: omega‐3 fatty acids compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Omega‐3 fatty acids compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults (aged 18 and older) exposed to a traumatic event Setting: intensive care unit of a disaster medical center Intervention: omega‐3 fatty acids Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with omega‐3 fatty acids | |||||

| PTSD severity at 3 months assessed with: CAPS (Matsuoka 2015) | The mean PTSD severity at 3 months was 9.22 | Mean 1.56 higher (4.06 lower to 7.18 higher) | ‐ | 100 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | |

| Dropout due to adverse events at 3 months | Study population | Not estimable | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| PTSD rate at 3 months assessed with: DSM‐IV criteria | Study population | RR 2.44 (0.23 to 26.09) | 100 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc | ||

| 18 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 (4 to 474) | |||||

| Functional disability at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Quality of life at 3 months assessed with: SF‐36, MSC | The mean quality of life at 3 months was 51.6 | Mean 3 lower (7.4 lower to 1.4 higher) | ‐ | 99 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CAPS: Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale; CI: confidence interval; DSM‐IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐4th Edition; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SF‐36, MSC: Medical Outcomes Study 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey, mental component summary | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for imprecision as far fewer than 400 participants were included and the confidence interval is wide bDowngraded two levels for imprecision as the number of participants is very far from the optimal information size (OIS) cDowngraded two levels as the OIS is not met and the confidence interval includes both appreciable benefit and harm

3. Additional summary of findings table: propranolol compared to gabapentin for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Propranolol compared to gabapentin for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults (aged 18 and older) exposed to a traumatic event Setting: surgical trauma center Intervention: propranolol Comparison: gabapentin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with gabapentin | Risk with propranolol | |||||

| PTSD severity at 3 months ‐ not reported | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Dropout due to adverse events at 3 months ‐ not reported | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| PTSD rate at 3 months assessed with: CIDI | Study population | RR 1.25 (0.26 to 6.07) | 22 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 250 per 1000 (52 to 1000) | |||||

| Functional disability at 3 months ‐ not reported | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Quality of life at 3 months ‐ not reported | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CIDI: Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias as the included study has high attrition rates for these interventions bDowngraded two levels as the optimal information size is not met and the CI includes both appreciable benefit and harm

4. Additional summary of findings table: paroxetine compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| Paroxetine compared to placebo for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | |||

| Patient or population: adults (aged 18 and older) exposed to a traumatic event Setting: trauma center Intervention: paroxetine Comparison: placebo | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| PTSD severity at 3 months assessed with: PCL‐C | Change from baseline PCL‐C scores: paroxetine: ‐4.0, placebo +0.3, without statistical significance with alpha set at 0.05. No variance measure is reported nor the number of analysed participants. | (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b |

| Dropout for any reason at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ |

| PTSD rate at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| Functional disability at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ |

| Quality of life at 3 months assessed with: SF‐36 | Change from baseline SF‐36 scores: paroxetine: +4.1, placebo +4.4, without statistical significance with alpha set at 0.05. No variance measure is reported nor the number of analysed participants. | (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b |

| PCL‐C: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist ‐ Civilian version; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SF‐36: Medical Outcomes Study 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

aDowngraded one level for unclear risk of bias in allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting bDowngraded two levels for imprecision as much fewer than 400 participants were included

5. Additional summary of findings table: PulmoCare formula compared to Oxepa formula for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

| PulmoCare formula compared to Oxepa formula for preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | |||

| Patient or population: adults (aged 18 and older) exposed to a traumatic event Setting: N/A Intervention: PulmoCare formula Comparison: Oxepa formula | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| PTSD severity at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| Dropout due to adverse events at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome at this timepoint | ‐ | ‐ |

| PTSD rate at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ |

| Functional disability at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ |

| Quality of life at 3 months ‐ not measured | No study reported this outcome | ‐ | ‐ |

| PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||