Abstract

The rise of antimicrobial-resistant phenotypes and the spread of the global pandemic of COVID-19 are worsening the outcomes of hospitalized patients for invasive fungal infections. Among them, candidiases are seriously worrying, especially since the currently available drug armamentarium is extremely limited. We recently reported a new class of macrocyclic amidinoureas bearing a guanidino tail as promising antifungal agents. Herein, we present the design and synthesis of a focused library of seven derivatives of macrocyclic amidinoureas, bearing a second phenyl ring fused with the core. Biological activity evaluation shows an interesting antifungal profile for some compounds, resulting to be active on a large panel of Candida spp. and C. neoformans. PAMPA experiments for representative compounds of the series revealed a low passive diffusion, suggesting a membrane-based mechanism of action or the involvement of active transport systems. Also, compounds were found not toxic at high concentrations, as assessed through MTT assays.

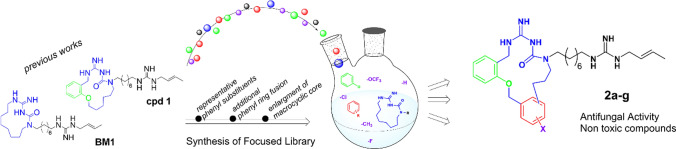

Graphical abstract

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11030-022-10388-7.

Keywords: Amidinourea, Antifungal agents, Candida, Cryptococcus, Macrocycles, PAMPA

Introduction

Nowadays, the burden of systemic fungal infections is threatening public health. Numbers speak for themselves: annually, more than 150 million people are estimated to suffer from fungal diseases, resulting in a considerable negative impact on their life [1]. Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are among the most common nosocomial infections, [2] killing up to 1.5 million people each year [3]. IFIs are related to severe illness and high mortality [4–6] in patients with immunocompromised conditions. Moreover, the global emergency caused by SARS-CoV-2 worsened the scenario, leading affected people to intubation, mechanical ventilation, and long-term hospitalization that increase the susceptibility to the development of fungal infections [7–9]

Candida species are responsible for nearly half of IFIs [10, 11]. The most predominant pathogenic strain in bloodstream infections is C. albicans. However, recently, diseases caused by non-albicans Candida (NAC) species are increasing in concern [12]. Currently available treatments are mainly represented by azoles, the only orally available class in clinics. Unfortunately, C. krusei, C. auris, and C. glabrata, belonging to NAC species, are characterized by a low intrinsic susceptibility to these antifungals and are highly prone to develop resistomes [10]. Moreover, C. glabrata displayed a high capacity to form biofilms on artificial devices and epithelial surfaces, leading to a reduction in the drug absorption and consequent decreases in the treatment efficacy [13–15].

Besides Candida species, Cryptococcus neoformans is highly invasive in humans, causing life-threatening meningitis [16], especially in resource-limited regions where treatments of choice based on amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine are not available since too expensive [17].

However, the clinically available antifungal arsenal is still limited to old drug classes, and the more recently developed, the echinocandins, can be traced back to the early 2000s [13, 15, 17]. Only one drug candidate, Fosmanogepix, a broad-spectrum antifungal agent, is endowed with an innovative mode of action (MoA), but it is still in clinical trials [18]. Furthermore, no vaccine has still received the food and drug administration (FDA) approval to date. Thus, in this frame, the need for new antifungal agents is pressing to address the high mortality risk of IFIs.

In the last decades, we reported the discovery of a new class of non-azole antifungal agents endowed with an amidinourea macrocyclic scaffold bearing a guanidino tail. The hit compound of the series BM1 (Figure 1) showed antifungal activity with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC50) values ranging from 1.25 to 20 µg/mL against several Candida spp. strains [19–21]. Moreover, it displayed an interesting in vitro and in vivo ADMET profile, even if a limited passive diffusion was highlighted in the previously reported parallel artificial permeability assay (PAMPA) [22].

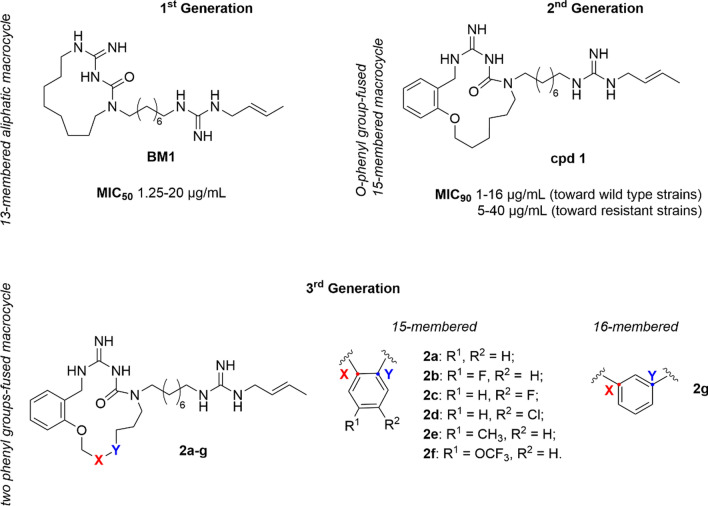

Fig. 1.

Structure of BM1, compound 1, and derivatives 2a–g described in this paper with MIC ranges against Candida spp. strains

A small library of derivatives was designed by modifying both the macrocyclic core and the lateral guanidino tail. In particular, the 13-membered macrocyclic portion was enlarged up to 15 carbon atoms and an O-phenyl group was fused with it, resulting in a remarkable inhibitory activity against representative Candida spp. strains, including some drug-resistant clinical isolates [19–21]. Compound 1 (Figure 1) emerged as a good candidate for further studies, exhibiting an enhanced activity against all the tested Candida strains (MIC90 values ranging from 1 to 40 µg/mL) and a more lipophilic macrocyclic scaffold due to the introduction of the O-phenyl group. Indeed, this chemical modification was expected to favor the establishment of additional interactions with putative targets through π-stacking and enhance the compound membrane permeability [20].

As regards the MoA of the amidinoureas class, it is still under investigation, however, in-depth studies seem to confirm an intracellular accumulation of these derivatives [21] and specific interaction with cell structures such as receptors or enzymes, as found through the previously described in silico target fishing protocol [23]. However, what we expect for amidinoureas is an innovative MoA, not shared with current antifungals, since suggested by the notable activity profile found in drug-resistant fungal strains, especially those overexpressing CDR efflux pumps [21].

In order to further explore the chemical space of the macrocyclic core, derivatives with an additional phenyl group were designed. In particular, we synthesized 2a, characterized by a 15-membered macrocycle in which the additional phenyl ring is fused with the macrocycle in ortho-position and 2g in which it is in meta-position, generating a 16-membered ring (Figure 1). Then, 2b–f (Figure 1), surrounded by some representative electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups, were prepared to gain an understanding of how they could affect the antifungal activity. Also, PAMPA experiments of compounds 1 and 2a–f were performed to assess the impact of their larger core on membrane permeability, since clogP values are increased with respect to BM1, as calculated by SwissADME tool [24] (data not shown).

Results and discussion

Chemistry

The previously published synthetic approach [20] was adapted and optimized to prepare compounds 2a–g. The synthesis of compounds 2a–f and 2g followed the same reaction steps by using different constitutional isomers as key intermediates: the o-vinylated derivatives 6a–f (Scheme 1) and the m-vinylated one 6g (Scheme 2).

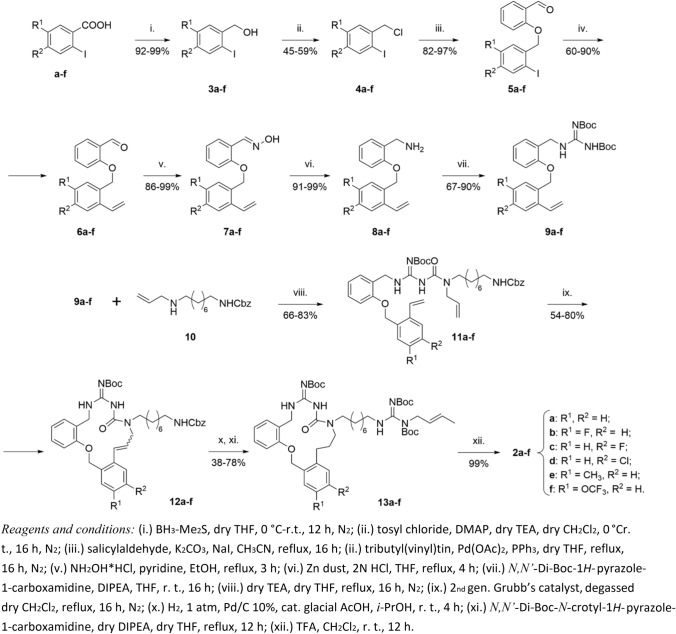

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of final compounds 2a–f

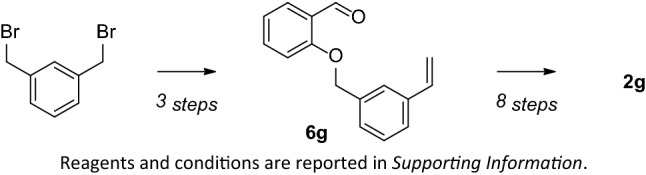

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of final compound 2f. Reagents and conditions are reported in Supporting Information

The preparation of compounds 6a–f started from the appropriately substituted 2-iodobenzoic acids (a–f) that were first reduced to benzyl alcohols 3a–f. Then, the hydroxy group of 3a–f was converted into a better leaving group, furnishing chlorides 4a–f. The reaction was carried out in mild conditions with tosyl chloride, dimethylaminopyridine, and triethylamine (TEA) due to the co-presence of the more reactive iodine atom in the starting materials 3a–f [25]. Then, 4a–f were reacted with salicylaldehyde to furnish the phenyl ethers 5a–f. Finally, the palladium–catalyzed coupling with a vinyl stannane led to derivatives 6a–f according to Stille conditions. Aldehydes 6a–f were first converted into aldoximes 7a–f and then reduced to benzyl amines 8a–f via zinc-mediated hydrogenation. Derivatives 9a-f were finally achieved by guanylating the primary amine moiety with N,N’-Di-Boc-1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine [26, 27]. The primary amine belonging to the previously described linker 10 [20] was reacted with the diBoc-guanidino moiety of 9a–f, furnishing tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-protected amidinoureas 11a–f [28]. The latter compounds were endowed with two olefin groups, used as substrates for a ring-closing metathesis. To obtain macrocycles 12a–f, the second generation Grubb’s catalyst was added to a very diluted degassed CH2Cl2 solution of 11a–f. A palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation led to the simultaneous removal of carboxybenzyl (Cbz) protecting group and olefin reduction, affording free amino functions that were subsequently guanylated by the N-crotyl-guanylating agent [19] to yield derivatives 13a–f. In the end, final compounds 2a–f were obtained as trifluoroacetate salts after Boc-cleavage.

Instead, the meta-vinylated intermediate 6g was synthesized through Wittig reaction from m-xylylene dibromide in only three steps (as summarized in Scheme 2) and followed the above-mentioned synthetic route employed for the isomers 6a–f. The whole synthetic pathway along with the intermediates procedures and characterizations were fully reported in Scheme S 1 and in Supporting Information.

Biological evaluation

The antifungal activity of the synthesized compounds 2a–g was evaluated by determining MIC90 against more than 100 strains belonging to 8 Candida spp. (C. albicans, C. guilliermondii, C. crusei, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. kefyr, C. glabrata, and C. lipolytica) and 15 strains of Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from oral, vaginal, anorectal, urine, stool, blood, central venous catheter, and respiratory tract specimen with each strain representing a single isolate from a patient (Table 1).

Table 1.

MICs of derivatives library (2a–g) against representative Candida spp. and C. neoformans strains

| Antifungal activity, MIC90 [µg/mL]a | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungal strains | F | BM1b | 1 | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2d | 2e | 2f | 2 g |

| C. albicans (22) | 2 | 2.5 | 3.12 | 1 | 3.12 | 3.12 | 3.12 | 4 | 2 | 64 |

| C. guilliermondii (10) | 4 | n.d | 12.5 | 4 | 3.12 | 3.12 | 1.56 | 2 | 2 | 128 |

| C. krusei (13) | 256 | 5 | 6.25 | 8 | 3.12 | 3.12 | 1.56 | 2 | 4 | 64 |

| C. parapsilosis (24) | 0.5 | 5 | 3.12 | 1 | 3.12 | 3.12 | 3.12 | 16 | 16 | 64 |

| C. tropicalis (11) | 2 | 1.25 | 1.56 | 8 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 4 | 4 | 64 |

| C. kefyr (10) | 1 | n.d | 6.25 | 2 | 3.12 | 3.12 | 1.56 | 4 | 4 | 32 |

| C. glabrata (26) | 16 | 20 | 25 | 16 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 6.25 | 16 | 16 | 512 |

| C. lipolytica (10) | n.d | n.d | 25 | 256 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 12.5 | 4 | 4 | n.a |

| C. neoformans (15) | 2 | n.d | 6.25 | n.d | 3.12 | 3.12 | 3.12 | 4 | 4 | n.d |

aMICs are expressed in μg/mL as the average values calculated from experiments performed at least in triplicate and determined at 24 h both visually and spectrophotometrically. MIC50 = Minimum inhibitory concentration required to inhibit the growth of 50% of organisms. MIC90 = Minimum inhibitory concentration required to inhibit the growth of 90% of organisms. The number of tested strains per species is reported in parentheses. Fluconazole (F) and BM1 are reported as reference control and reference compound, respectively

n.d.: not determined; n.a.: not active, no activity observed till compound concentration of 256 µg/mL

bMIC50 values for BM1 were already reported for some Candida species [20]

All the derivatives show improved antifungal activity against almost all the tested strains, except the 16-membered macrocycle 2g with respect to the hit compound 1 (Table 1). The introduction of a second phenyl group in the 15-membered macrocycle proved to significantly enhance the antifungal activity, as evident for compound 2a which showed lower MIC values with respect to the correspondent mono-phenyl derivative 1 against C. albicans, C. kefyr, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. On the other hand, a complete loss of activity against C. lipolytica was noticed for 2a (Table 1). The functionalization of the new phenyl ring with one halogen atom, such as fluorine (2b–c) and chlorine (2d), resulted in a better activity profile against some Candida strains. In fact, the halogenated derivatives 2b–d exert a strong antifungal activity against C. glabrata with MIC values twofold–fourfold lower than 1 and C. guilliermondii, C. krusei, and C. kefyr (3.12–1.56 µg/mL) and comparable activities to compound 1 toward C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis (Table 1).

Moreover, the substitutions in C4 and C5 of the second phenyl ring were found to impact similarly the biological activity, as highlighted by the same activity profile of the fluoro-isomers 2b and 2c. The best compound in terms of activity, 2d, is less active against C. lipolytica than the fluorine derivatives 2b–c (Table 1). Also, compounds bearing methyl (2e) and trifluoromethoxy (2f) substituents resulted overall active although less strong than halogenated compounds 2b–d (Table 1). In the end, derivative 2g, characterized by a 16-membered ring, showed a dramatic loss of activity against all tested species, suggesting the key role of the macrocyclic size for biological activity. These data could confirm our hypothesis of a proteic target since tiny chemical modifications in the structure led to a total or partial loss of antifungal activity (Table 1).

In summary, 15-membered derivatives 2a–e were found more active than the hit compound 1 against most of the fungal strains and, remarkably, active against strains not susceptible to fluconazole, C. glabrata, and C. krusei. As mentioned above, infections from C. glabrata are representing a serious threat since it is one of the most resistant fungal species, together with C. auris, to the azole drug-based treatments. Moreover, halogenated derivatives 2b–d were highlighted as the most active compound of the series, showing also an inhibitory activity against C. neoformans, the pathogenic fungi responsible for fatal meningitis, comparable to that of fluconazole (Table 1).

Cytotoxicity on human fibroblasts

To evaluate the selectivity of the series, the cytotoxicity profile was assessed by determining the CC50 value on Normal Human Dermal Fibroblast (FIBRO) cell line through the MTT assay. Compounds 2a, 2b, and 2d were selected as the most interesting representatives of the library in terms of antifungal activity. As shown in Table 2, after 24 h, 2a and 2b were found to be not cytotoxic at high concentrations (CC50 > 100 μg/mL), while 2d a lower CC50 (38.50 μg/mL), still maintaining a good selectivity index (> 12) for almost all the tested strains.

Table 2.

In vitro cytotoxicity results on FIBRO cells for derivatives 2a, 2b, and 2d

|

CC50

on FIBRO cell line [µg/mL ± S.D.] |

||

|---|---|---|

| Cpd | 24 h | 48 h |

| 2a | > 100 | 36.17 ± 1.86 |

| 2b | > 100 | 24.86 ± 1.07 |

| 2d | 38.50 ± 2.18 | 25.44 ± 1.67 |

CC50 values were determined after 24 and 48 h of incubation in FIBRO cell line. Data are reported as means ± standard deviation (S.D.) of three independent experiments, each done in triplicate

PAMPA experiments

PAMPA was performed to evaluate if the introduction of an additional phenyl ring into the macrocyclic portion could be useful to gain an enhancement in the membrane permeability via passive diffusion. Thus, compounds 2a, 2b, and 2d were selected as representatives of the new series, and the experiment was conducted also on compound 1 to make a comparison among the apparent permeability (Papp) values determined for the aliphatic macrocycle of BM1, the O-phenyl-fused macrocycle of 1, and the tricycle core of 2. All the tested diphenyl derivatives and 1 showed very low Papp values (Table 3) close to that reported for BM1,[22] resulting in scarce permeability, and were highly retained from the bilayer, with approximatively 50% of membrane retention percentage. Although the chemical modification led to an increase in lipophilicity, it was not able to affect the passive absorption of these derivatives, as hypothesized. However, the high membrane retention of this class of compounds could be correlated to additional MoAs involving membranes directly or membrane proteins or transporters, as previously demonstrated [21].

Table 3.

PAMPA results for tested compounds

| Cpd | Papp [10–6 cm/sec] |

Membrane retention (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | < 0.01 | 50.8 |

| 2a | < 0.01 | 55.3 |

| 2b | < 0.01 | 50.6 |

| 2d | < 0.01 | 52.1 |

| Caffeine | 1.84 | 3.2 |

| Chloramphenicol | 0.30 | 26.3 |

Experiments were performed in duplicate. LC-UV–MS method is described in Experimental section. Caffeine and chloramphenicol are reported as reference compounds

Conclusion

Fungal infections represent one of the global healthy treats to date. Among compounds endowed with antifungal activity, macrocycle amidinoureas emerged for their innovative structure and their potent activity toward most Candida species including some resistant clinical isolates.

In this study, we investigated the insertion of a second ring into the macrocycle core of a previously described derivative 1, by synthesizing two isomers, compounds 2a and 2b, endowed with a 15- and 16-membered cycle, respectively. The chemical modification led to a slightly better biological profile for 2a and a complete loss of activity for 2f. Also, we functionalized the phenyl ring with some representative electron-withdrawing and donating groups, such as halogen atoms, methyl, and trifluoromethoxy groups. The synthesized derivatives showed promising antifungal activity against a panel of Candida spp. and C. neoformans microorganisms that was found overall stronger than hit compound BM1 and fluconazole. Remarkably, 2b-d emerged as the best derivatives in terms of antifungal activity toward C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. kefyr, commonly resistant to most of the current treatments and not susceptible to the azole class. We could hypothesize a possible interaction with a specific pharmacological target, such as an enzyme or receptor since tiny modifications in the chemical structure resulted in a significant change in the biological activity. However, in-depth investigation of the MoA of macrocyclic amidinoureas is still ongoing.

Furthermore, three representatives of the series, compounds 2a, 2b, and 2d, were found low cytotoxic at high concentrations in MTT assays, resulting in a good selectivity index. Also, we checked these compounds for their passive permeability through PAMPA experiments. Although more lipophilic (as calculated by means of SwissADME tool)[24] than hit compound 1, they showed low passive adsorption comparable to that of compound 1.

In summary, the series described herein was found to exert an interesting antifungal activity, proving the impact of the insertion of the second phenyl ring into the macrocyclic scaffold in the biological profile. These results highlight this tricyclic core of the macrocyclic amidinoureas a putative starting point for the development of a new class of antifungal agents.

Experimental section

Chemistry

General Chemistry All commercially available chemicals and solvents were used as purchased. CH2Cl2 was dried over calcium hydride and tetrahydrofuran (THF) was dried over sodium and benzophenone before use. Degassed dry CH2Cl2 was prepared from freshly dried CH2Cl2 via three or more freeze–pump–thaw cycles. Dry DIPEA was purchased from Merck. Dry TEA was dried over KOH and distilled under nitrogen atmosphere. Anhydrous reactions were performed into flame-dried glassware after three cycles of vacuum/ dry nitrogen and were run under a positive pressure of dry nitrogen. Chromatographic separations were performed on columns packed with silica gel (230–400 mesh, for flash technique). TLCs were visualized under UV light and stained with ninhydrin, bromocresol green, or basic permanganate stains. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 spectrometer at 400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively. Spectra are reported in parts per million (δ scale) and internally referenced to the CDCl3 and CD3OD signal, respectively at δ 7.26 and 3.31 ppm. Chemical shifts for carbon are reported in parts per million (δ scale) and referenced to the carbon resonances of the solvent (CDCl3 at δ 77.0 and CD3OD at δ 49.0 ppm). Data are shown as following: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, qi = quintet, m = multiplet and/or multiplet resonances, bs = broad singlet), coupling constants (J) in Hertz (Hz), and integration. Mass spectra (LCMS (ESI)) were acquired using an Agilent 1100 LC-MSD VL system (G1946C) by direct injection with a 0.4 mL/min flow rate using a binary solvent system of 95/5 MeOH/H2O. UV detection was monitored at 221 or 254 nm. Mass spectra were acquired in positive or negative mode scanning over the mass range 100–1500 m/z, using a variable fragmentor voltage of 0–70 V.

Determination of purity The purity of final products (≥ 95%) was assessed by LC-UV–MS analysis using the protocol reported [29].

Synthetic procedures and characterizations of compound 2a and its intermediates

(2-iodophenyl)methanol (3a) To a stirred suspension of 2-iodobenzoic acid (3.00 g, 12.09 mmol) in dry THF (40 mL), borane dimethyl sulfide complex (3.44 mL, 36.29 mmol) was added dropwise under N2 atmosphere at 0 °C. Then, the reaction mixture was allowed to gently warm at r.t. and stirred for 12 h. Water and K2CO3 were carefully added and the mixture was stirred for additional 30 min. Then, the mixture was extracted with AcOEt and washed twice with 1 N NaOH and then with brine. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated in vacuo to give pure 2-iodobenzyl alcohol 3a as a white solid. Yield: 98%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 7.80 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.49 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 142.5, 139.1, 129.2, 128.4, 128.3, 97.3, 59.8.

1-(chloromethyl)-2-iodobenzene (4a) To a stirred solution of 3a (2.78 g, 11.88 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (80 mL), freshly distilled dry TEA (1.66 mL, 11.88 mmol) and DMAP (1.74 g, 14.26 mmol) were added under N2 atmosphere at 0 °C. Then, p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (4.07 g, 21.38 mmol) was added portionwise and the reaction mixture was stirred for additional 30 min at 0 °C, then at r.t. for 16 h. The solvent was removed by evaporation in vacuo and the crude was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel, eluting with hexane to give compound 4a. Yield: 56%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 7.85 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 139.8, 135.6, 129.7, 129.3, 126.7, 96.8, 44.2.

2-[(2-iodophenyl)methoxy]benzaldehyde (5a) To a stirred solution of salicylaldehyde (0.50 mL, 4.69 mmol) in CH3CN (10 mL), K2CO3 (710.0 mg, 5.16 mmol), NaI (0.18 g, 1.17 mmol), and 4a (1.30 g, 5.16 mmol) were added and the reaction mixture was stirred at reflux for 16 h. After evaporation in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in AcOEt, 1 N NaOH was added, and the mixture was stirred at r.t. for additional 10 min. Then, the mixture was extracted with AcOEt three times, and the combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated in vacuo to give 5a. Yield: 92%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 10.58 (s, 1H), 7.87 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (m, 1H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (m, 2H), 5.16 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 189.4, 160.8, 142.2,139.5, 135.9, 129.6, 129.2, 128.6, 128.2, 125.3, 121.1, 113.0, 92.9, 67.9.

2-[(2-ethenylphenyl)methoxy]benzaldehyde (6a) To a stirred solution of iododerivative 5a (1.11 g, 3.28 mmol) in dry THF (46 mL), palladium acetate (73.0 mg, 0.33 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (172.0 mg, 0.66 mmol) were added under N2 atmosphere. Then, tributyl(vinyl)tin (1,13 mL, 3.93 mmol) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred at reflux for 16 h. After cooling, the mixture was filtered through a plug of celite, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was diluted with AcOEt, washed with NaHCO3ss and brine. Then, it was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated in vacuo. The crude was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel, eluting with hexane/AcOEt 9:1. Yield: 90%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 10.47 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (m, 2H), 7.42 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (m, 2H), 6.99 (dd, J = 17.2 Hz, 11.2 Hz, 1H), 5.70 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.22 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 189.6, 160.9, 137.2, 135.8, 133.6, 128.8, 128.3, 127.9, 126.2, 125.3, 121.0, 117.0, 113.0, 77.1, 76.8, 68.8.

Aldoxime derivative (7a) To a stirred solution of benzaldehyde 7a (334.0 mg, 1.84 mmol) in EtOH (25 mL), pyridine (180 μL, 2.21 mmol) and hydroxylamine hydrochloride (320.0 mg, 4.6 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred at reflux for 3 h. After cooling, the mixture was evaporated in vacuo and the residue was dissolved in AcOEt, washed with brine twice, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated in vacuo. Yield: 96%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.31 (bs, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.34 (m, 3H), 6.95 (m, 3H), 5.69 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.14 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 163.5 156.6, 146.3, 137.1, 133.6, 133.1, 131.2, 128.9, 128.6, 127.8, 126.6, 126.1, 121.2, 116.9, 112.5, 68.4. LCMS (ESI) m/z = 276.0 [M + Na]+, 254.0 [M + H]+.

Benzylamino derivative (8a) To a stirred solution of aldoxime 7a (251.0 mg, 0.99 mmol) in THF (12 mL), zinc dust (650.0 mg, 9.89 mmol) and 2 N HCl (5 mL) were added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at reflux for 4 h. After cooling, the mixture was filtered on a plug of celite, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in AcOEt and extracted with 3 N HCl three times. Then, the aqueous phase was basified with K2CO3 and extracted with CH2Cl2 three times. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated in vacuo. Compound 8a was obtained without any further purification. Yield: 99%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.56 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (m, 3H), 5.70 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 3.81 (s, 2H), 1.62 (bs, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 156.4, 137.0, 133.8, 133.7, 131.8, 129.3, 129.2, 128.9, 128.8, 128.5, 128.3, 128.1, 127.9, 126.0, 120.9, 116.6, 111.4, 67.5, 42.1. LCMS (ESI) m/z = 262.1 [M + Na]+, 240.1 [M + H]+.

DiBoc-guanidino derivative (9a) To a stirred solution of primary amine 8a (251.0 mg, 1.05 mmol) in THF (10 mL), N,N′-Di-Boc-1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine (420.2 mg, 1.36 mmol) and DIPEA (90 µL, 0.52 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 16 h. After cooling, AcOEt was added, and the mixture was washed with water and brine. After drying over anhydrous Na2SO4, the mixture was filtered and evaporated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel, eluting with hexane/AcOEt 9:1 to give the pure compound 9a. Yield: 78%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 11.47 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (m, 2H), 6.95 (m, 3H), 5.66 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 4.63 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 1.49 (s, 9H), 1.44 (s, 9H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 163.6, 156.7, 156.3, 156.0, 152.9, 136.8, 133.7, 129.8, 128.9, 128.7, 128.2, 127.7, 126.0, 120.9, 116.7, 111.6, 82.7, 79.0, 68.1, 40.6, 28.3, 28.0. LCMS (ESI) m/z = 504.1 [M + Na]+, 482.1 [M + H]+.

Boc-amidinourea derivative (11a) To a stirred solution of 9a (246.1 mg, 0.51 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL), a solution of linker 10 (N-(8-(allylamino)octyl)-2-phenylacetamide (261.0 mg, 0.82 mmol) in dry THF (5 mL) and freshly distilled dry TEA (70 µL, 0.51 mmol) were added dropwise under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at reflux for 16 h. After cooling, AcOEt was added, and the mixture was washed with water and brine. After drying over anhydrous Na2SO4, the mixture was filtered and evaporated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel, eluting with hexane/AcOEt 8:2 to give pure compound 11a. Yield: 73%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 12.28 (s, 1H), 8.41 (s, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (m, 5H), 7.32 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (m, 1H), 7.02 (m, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 2H), 5.77 (m, 1H), 5.66 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 5.32 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 5.09 (m, 4H), 5.01 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 4.55 (dd, J = 14.8 Hz, 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.05 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 3.21 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.14 (m, 2H), 1.51 (m, 4H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.21 (m, 8H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 163.7, 156.5, 154.1, 153.9, 153.3, 135.3, 134.7, 133.7, 129.3, 129.0, 128.7, 128.6, 128.4, 128.4, 128.0, 127.8, 126.8, 126.0, 120.7, 116.7, 115.5, 111.5, 81.9, 68.1, 66.5, 50.5, 48.5, 47.5, 45.7, 41.0, 40.1, 29.8, 29.4, 29.2, 28.5, 28.0, 27, 26.9, 26.6. LCMS (ESI) m/z = 748.9 [M + Na] +, 726.9 [M + H]+.

Unsaturated macrocyclic amidinourea (12a) To a stirred solution of amidinourea derivative 9a (247.1 mg, 0.34 mmol) in freshly degassed dry CH2Cl2 (170 mL, 2 mM solution), a solution of 2nd generation Grubb’s catalyst (58.0 mg, 0.2 mmol) in freshly degassed dry CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was added dropwise under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at reflux for 16 h. After cooling, the mixture was evaporated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel, eluting with hexane/AcOEt 85:15 to give macrocycle 12a. Yield: 75%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 12.27 (bs, 1H), 8.40 (m, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (m, 6H), 7.23 (m, 3H), 6.98 (m, 3H), 6.58 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 6.16 (dt, J = 15.6 Hz, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 5.08 (s, 2H), 4.69 (bs, 1H), 4.61 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.92 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 3.35 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 3.16 (m, 2H), 1.57 (s, 4H), 1.46 (m, 9H), 1.23 (s, 8H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 163.7, 155.3, 154.2, 153.6, 138.1, 137.8, 136.9, 129.6, 129.4, 129.1, 128.8, 128.7, 128.3, 126.5, 122.9, 118.6, 99.9, 82.2, 72.2, 66.5, 45.1, 44.1, 43.4, 40.9, 31.1, 29.3, 29.2, 28.5, 27.3. LCMS (ESI) m/z = 698.2 [M + H] +.

DiBoc-guanidino macrocyclic amidinourea (13a) To a stirred solution of 10a (180.2 mg, 0.17 mmol) in isopropanol (19 mL), Pd/C 10% (32.0 mg, 0.03 mmol) and a few drops of glacial AcOH were added. The reaction mixture was subject to three cycles of vacuo followed by a flush of H2 before being stirred under H2 (1 atm) for 4 h. Then, the mixture was filtered through a plug of celite, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The crude product was used directly in the next step without any further purification. LCMS (ESI) m/z = 566.3 [M + H] +. To a stirred solution of the crude in dry THF (4.5 mL), a solution of the crotyl guanylating agent (N,N’-Di-Boc-(E)-N-crotyl-1H-pyrazole-1-carboximidamide, 60.0 mg, 0.17 mmol) in dry THF (2.8 mL) and dry DIPEA (89 µL, 0.51 mmol) were subsequently added under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at reflux for 12 h. After cooling, the mixture was evaporated in vacuo and the residue was dissolved in AcOEt, washed with water twice and brine. After drying over anhydrous Na2SO4, the mixture was filtered, and evaporated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel, eluting with hexane/AcOEt 8:2 to give pure compound 13a. Yield: 52% over two steps. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 12.20 (s, 1H), 8.54 (s, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (m, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (m,1 H), 5.65 (m, 1H), 5.50 (m, 1H), 5.06 (s, 2H), 4.57 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.18 (m, 6H), 2.53 (m, 2H), 1.97 (m, 2H), 1.65 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 3H), 1.48 (m, 31H), 1.29 (s, 8H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 163.6, 156.0, 155.5, 153.6, 153.3, 142.7, 134.0, 130.7, 129.9, 129.7, 128.9, 127.7, 127.4, 126.5, 126.1 125.8, 120.6, 110.6, 82.9, 82.1, 79.1, 69.4, 60.3, 49.9, 47.3, 40.9, 38.1, 30.8, 30.2, 29.6, 29.3, 29.2, 28.9, 28.7, 28.2, 28.1, 28.0, 27.0, 26.8, 20.9, 17.1. LCMS (ESI) m/z = 884.3 [M + Na]+, 862.4 [M + H]+.

Guanidino macrocylic amidinourea trifluoroacetate salt (2a) To a stirred solution of 13a (10.0 mg, 0,014 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (1.7 mL), freshly distilled TFA (300 µL, final concentration 10% v/v) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 12 h. The mixture was evaporated in vacuo. Then, it was treated with toluene and methanol and evaporated in vacuo to remove TFA residue. The crude was treated with Et2O and hexane and then decanted, and the solvents were pipetted off. This procedure was repeated several times to yield compound 2a. Yield: 99%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.45 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (dd, J = 17.5 Hz, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (dd, J = 11.7 Hz, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (m, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 5.73 (m, 1H), 5.49 (m, 1H), 5.07 (s, 2H), 4.43 (m, 2H), 3.74 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.39 (m, 1H), 3.28 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 3.15 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.82 (s, 1H), 2.61 (s, 1H), 2.09 (m, 1H), 1.85 (m, 1H), 1.70 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H), 1.55 (m, 6H), 1.31 (m, 8H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 157.4, 155.0, 152.0, 131.2, 131.1, 130.8, 130.1, 129.6, 127.2, 127.0, 126.4 125.4, 124.1, 122.5, 122.0, 121.0, 117.1, 116.3, 113.4, 85.9, 79.3, 44.0, 42.5, 30.7, 30.3, 30.2, 30.0, 27.6, 17.8. LCMS (ESI) m/z = 584.4 [M + Na]+, 562.3 [M + H]+, 281.7 [M + 2H]2+.

Procedures and characterizations for final compounds 2b-g and their intermediates (3-13b-g and 14–15) are reported in Supporting Information.

Antifungal activity testing

Yeast cells were grown in yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) medium at 37 °C for 16 h and 150 rpm orbital shaker. Cells were then sub-inoculated in fresh YPD medium and grown to an optical density of 0.3. The turbidity of the inoculum was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland and diluted 1:500 in RPMI 1640 broth, corresponding to around 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL. MICs were determined by liquid growth inhibition assays by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, using serial dilutions of the compounds dissolved in an appropriate buffer with a final concentration ranging from 256 to 0.125 μg/mL in a 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plate [30]. Plates were incubated at 35 °C, and MICs were visualized after 24 h as the lowest concentration of the tested compound that completely inhibited cell growth.

MTT assay

All chemicals were purchased from Euroclone (Milan, Italy). In vitro cytotoxicity on normal human dermal fibroblasts, purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 10,000 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 v/v atmosphere. Briefly, 5 × 103 cells/well were plated in 0.2 mL of medium/well in 96-well plates, the day after seeding, a solution of the test compound in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (0.1 to 100 µg/mL) was added and incubated for 24 and 48 h at 37 °C in 5% v/v CO2 atmosphere. After incubation, the medium was carefully removed and each well was washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice and 150 µL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (5 mg/mL) in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) were added. The plates were incubated for 3 h in a 5% v/v CO2 atmosphere. After incubation, 100 µL of isopropanol were added to each well and plates were shaken at r.t. for 30 min. The optical density was measured by a microtiter plate reader (Multiskan SkyHigh Microplate Spectrophotometer, Thermo Fisher, Italy) at 570 nm. CC50 values were calculated by GraphPad Prism 6.0 software using the best fitting sigmoid curve. For each compound, the determination was performed in triplicate.

PAMPA experiments

Papp values of the tested compounds were evaluated as previously reported.[31] Briefly, for each compound, a donor solution was prepared from a stock solution of the test compound in DMSO (1 mM) diluted with PBS (pH 7.4, 25.0 mM) to a final concentration of 500 μM. Donor wells were filled with 150 µL of the donor solution. Filters were coated with 5 μL of a 1% w/v phosphatidylcholine (L-α-phosphatidylcholine egg yolk, Type XVI-E, purchased from Merck) in dodecane solution and the lower wells were filled with 300 µL of the acceptor solution (DMSO/PBS 1:1). The sandwich plate was assembled and incubated at r.t. for 5 h under gentle agitation. After the incubation time, the sandwich was disassembled and the amount of compound in each donor and acceptor wells was measured by the LC-UV–MS protocol. For each compound, the determination was performed in three independent experiments. Papp and MR% values were calculated as reported [32, 33].

Determination of pan-assay interference compounds

The behavior of all the tested compounds (2a-g) as pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) was examined through prediction by the web tools SwissADME [24, 34] and false positive remover, and no alert of PAINS was recorded.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at and contains the following paragraphs: Preparation of compound 2g. Chemical procedures and characterizations for final compounds 2b-g; 1H and 13C NMR spectra of some derivatives as representatives of the series.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank LDS (Lead Discovery Siena) S.r.l. for financial support.

Author contributions

L.J.I.B., I.D., A.C., D.D., G.I.T., and F.O. synthesized and characterized the compounds. R.M. and M.M. performed the biological assays. E.R. performed PAMPA experiments. C.V. performed cytotoxicity experiments. L.J.I.B., I.D., M.S., F.B., L.B., and E.D. analyzed data. L.J.I.B. and I.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lorenzo J.I. Balestri and Ilaria D’Agostino have contributed equally to the work.

References

- 1.Kainz K, Bauer MA, Madeo F, Carmona-Gutierrez D (2020) Fungal infections in humans: the silent crisis. Microb. cell 7:143–145. 10.15698/mic2020.06.718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Li Y, Gao Y, Niu X, et al. A 5-year review of invasive fungal infection at an academic medical center. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:553648. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.553648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases—estimate precision. J Fungi. 2017;3(4):57. doi: 10.3390/jof3040057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limper AH, Adenis A, Le T, Harrison TS. Fungal infections in HIV/AIDS. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:e334–e343. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Höfs S, Mogavero S, Hube B. Interaction of Candida albicans with host cells: virulence factors, host defense, escape strategies, and the microbiota. J Microbiol. 2016;54:149–169. doi: 10.1007/s12275-016-5514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pathakumari B, Liang G, Liu W. Immune defence to invasive fungal infections: a comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;130:110550. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cataldo MA, Tetaj N, Selleri M, et al. Incidence of bacterial and fungal bloodstream infections in COVID-19 patients in intensive care: an alarming “collateral effect”. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;23:290–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(9):2459–2468. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song G, Liang G, Liu W. Fungal co-infections associated with global COVID-19 pandemic: a clinical and diagnostic perspective from China. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:599–606. doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00462-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández-García R, de Pablo E, Ballesteros MP, Serrano DR. Unmet clinical needs in the treatment of systemic fungal infections: the role of amphotericin B and drug targeting. Int J Pharm. 2017;525:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NARR, et al. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(165):165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seyoum E, Bitew A, Mihret A. Distribution of Candida albicans and non-albicans Candida species isolated in different clinical samples and their in vitro antifungal suscetibity profile in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:231. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4883-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Posteraro B, Sanguinetti M, Fiori B, et al. Caspofungin activity against clinical isolates of azole cross-resistant Candida glabrata overexpressing efflux pump genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:458–461. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabaldón T, Gómez-Molero E, Bader O. Molecular typing of Candida glabrata. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:755–764. doi: 10.1007/s11046-019-00388-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perlin DS, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. The global problem of antifungal resistance: prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:e383–e392. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30316-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin YY, Shiau S, Fang CT. Risk factors for invasive Cryptococcus neoformans diseases: a case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0119090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roemer T, Krysan DJ. Unmet clinical needs, and new approaches. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a019703. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw KJ, Ibrahim AS. Fosmanogepix: a review of the first-in-class broad spectrum agent for the treatment of invasive fungal infections. J Fungi. 2020;6(4):239. doi: 10.3390/jof6040239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manetti F, Castagnolo D, Raffi F, et al. Synthesis of new linear guanidines and macrocyclic amidinourea derivatives endowed with high antifungal activity against Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. J Med Chem. 2009;52(23):7376–7379. doi: 10.1021/jm900760k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanguinetti M, Sanfilippo S, Castagnolo D, et al. Novel macrocyclic amidinoureas: potent non-azole antifungals active against wild-type and resistant Candida species. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:852–857. doi: 10.1021/ml400187w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deodato D, Maccari G, De Luca F, et al. Biological characterization and in vivo assessment of the activity of a new synthetic macrocyclic antifungal compound. J Med Chem. 2016;59:3854–3866. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orofino F, Truglio GI, Fiorucci D et al (2020) In vitro characterization, ADME analysis, and histological and toxicological evaluation of BM1, a macrocyclic amidinourea active against azole-resistant Candida strains. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55:105865. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.105865 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Maccari G, Deodato D, Fiorucci D, et al. Design and synthesis of a novel inhibitor of T. Viride chitinase through an in silico target fishing protocol. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:3332–3336. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;71(7):1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding R, He Y, Wang X, et al. Treatment of alcohols with tosyl chloride does not always lead to the formation of tosylates. Molecules. 2011;16:5665–5673. doi: 10.3390/molecules16075665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasero C, D’Agostino I, De Luca F, et al. Alkyl-guanidine compounds as potent broad-spectrum antibacterial agents: chemical library extension and biological characterization. J Med Chem. 2018 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamperini C, Maccari G, Deodato D, et al. Identification, synthesis and biological activity of alkyl-guanidine oligomers as potent antibacterial agents. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8251. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08749-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Agostino I, Ardino C, Poli G, et al (2022) Antibacterial alkylguanidino ureas: Molecular simplification approach, searching for membrane-based MoA. Eur J Med Chem 114158. 10.1016/J.EJMECH.2022.114158 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Miel H, Rault S. Conversion of N, N’-bis(tert-butoxycarbonyl)guanidines to N-(N’-tert-butoxycarbonylamidino)ureas. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39(12):1565–1568. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00025-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CLSI (2017) Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. 4st ed. CLSI guideline M27. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA

- 31.Rango E, D’Antona L, Iovenitti G, et al. Si113-prodrugs selectively activated by plasmin against hepatocellular and ovarian carcinoma. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;223:113653. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wohnsland F, Faller B. High-throughput permeability pH profile and high-throughput alkane/water log P with artificial membranes. J Med Chem. 2001;44:923–930. doi: 10.1021/jm001020e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugano K, Hamada H, Machida M, Ushio H. High throughput prediction of oral absorption: improvement of the composition of the lipid solution used in parallel artificial membrane permeation assay. J Biomol Screen. 2001;6:189–196. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baell JB, Holloway GA. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.