Abstract

Background

Multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales (MDR-E), including carbapenem-resistant and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE, CefR-E), are major pathogens following solid organ transplantation (SOT).

Methods

We prospectively studied patients who underwent lung, liver, and small bowel transplant from February 2015 through March 2017. Weekly perirectal swabs (up to 100 days post-transplant) were cultured for MDR-E. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on gastrointestinal (GI) tract–colonizing and disease-causing isolates.

Results

Twenty-five percent (40 of 162) of patients were MDR-E GI-colonized. Klebsiella pneumoniae was the most common CRE and CefR-E. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases and CTX-M were leading causes of CR and CefR, respectively. Thirty-five percent of GI colonizers developed MDR-E infection vs 2% of noncolonizers (P < .0001). The attack rate was higher among CRE colonizers than CefR-E colonizers (53% vs 21%, P = .049). GI colonization and high body mass index were independent risk factors for MDR-E infection (P ≤ .004). Thirty-day mortality among infected patients was 6%. However, 44% of survivors developed recurrent infections; 43% of recurrences were late (285 days to 3.9 years after the initial infection). Long-term survival (median, 4.3 years post-transplant) did not differ significantly between MDR-E–infected and MDR-E–noninfected patients (71% vs 77%, P = .56). WGS phylogenetic analyses revealed that infections were caused by GI-colonizing strains and suggested unrecognized transmission of novel clonal group-258 sublineage CR-K. pneumoniae and horizontal transfer of resistance genes.

Conclusions

MDR-E GI colonization was common following SOT and predisposed patients to infections by colonizing strains. MDR-E infections were associated with low short- and long-term mortality, but recurrences were frequent and often occurred years after initial infections. Findings provide support for MDR-E surveillance in our SOT program.

Keywords: CRE colonization and infection, solid organ transplant, molecular epidemiology, MDR-E colonization, MDR-E infection

Twenty-five percent of transplant recipients were gastrointestinally colonized by multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales, which predisposed to invasive infections. Infections were associated with low short-term and long-term mortality, but recurrences were common for years. Whole-genome phylogenetic analyses linked infections to colonizing strains.

Enterobacterales are colonizers of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Enterobacterales (MDR-E) are defined by resistance to ≥1 agent in ≥3 antibiotic classes [1]. MDR-E often produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), which confer resistance to third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, and AmpC β-lactamases that confer resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. Carbapenem resistance (CR) is caused most commonly by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs). ESBL and carbapenemase genes are typically carried with other resistance determinants on plasmids that can spread by horizontal transfer [2]. Nosocomial outbreaks of infections due to third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales (CefR-E) and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) are well recognized [3–5].

Solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients are particularly vulnerable to GI colonization and infections by MDR-E. In several studies, GI colonization rates among SOT recipients were approximately 15%–30% [6–10], and subsequent infection attack rates were approximately 20%–90% [7, 9, 11, 12]. MDR-E infections in these patients were associated with high mortality, prolonged lengths of hospital stay, and excess healthcare costs [13–16]. We previously reported that SOT recipients who survived CRE bloodstream infections at our center from 2009 through 2011 frequently developed recurrent infections [13]. We and others have shown that CRE-active β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors, introduced in 2015, have improved short-term outcomes of CRE infections [17, 18]. Long-term outcomes of SOT recipients with MDR-E infections are not well studied. Moreover, it is unclear if new β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors limit recurrent infections in SOT recipients on long-term follow-up.

Our objectives were to determine the molecular epidemiology, natural history, and long-term outcomes of MDR-E GI colonization and infections among SOT recipients in the era of new anti-CRE antibiotics.

METHODS

In the CREST study (CRE and MDR-E carriage among SOT recipients), we prospectively enrolled patients undergoing lung, liver, or small bowel transplants at our center between February 2015 and March 2017. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved CREST. During the study period, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), but not MDR-E perirectal surveillance was the standard of care. Data on MDR-E colonization were not available to clinical or infection prevention services.

Consented patients underwent weekly perirectal surveillance for MDR-E from transplant until discharge or 100 days post-transplant. Patients were excluded if a perirectal swab was not obtained during SOT admission. Swabs for CefR-E/ESBL and CRE were cultured on HardyCHROM selective agar plates (Hardy Diagnostics). Species identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing were performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass-spectrometry and Microscan (Beckman Coulter), respectively [19]. MDR-E were defined as CefR-E (nonsusceptible to third-generation cephalosporins, susceptible to carbapenems) or CRE (nonsusceptible to any carbapenem).

At least 1 MDR-E GI-colonizing species per patient underwent multiplexed, real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to identify ESBLs, AmpC, carbapenemases, and clonal group 258 (CG258) K. pneumoniae [20, 21]. Additional isolates from individual patients were evaluated if they displayed different morphotypes or susceptibility data or if patients had recurrent MDR-E colonization or infection (in which case, first and last isolates were evaluated). Short- and long-read whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed using Illumina HiSeq and Minion Nanopore (Oxford), respectively. Core genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) phylogenetic analysis was conducted on available MDR-E isolates. Details on WGS, assembly, and analyses are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Clinical data from 90 days pre-transplant through June 2020 were abstracted from electronic medical records (Supplementary Materials). Standard antibacterial prophylaxis is summarized in the Supplementary Materials. Types of infection were classified according to National Healthcare Safety Network criteria. Recurrent colonization was defined as culture positivity for the same MDR-E ≤90 days (early) or >90 days (late) after the initial positive culture, with an intervening negative culture. Recurrent infection was defined by culture positivity and concomitant signs and symptoms following clinical resolution and culture sterilization for an initial infection.

Statistical Analyses

Primary outcomes were MDR-E GI colonization and infection at 100 and 180 days post-transplant, respectively. Secondary outcomes were 30- and 90-day mortality from date of MDR-E infection; mortality at 90-days, 1-year, and last follow-up post-transplant; and recurrent MDR-E colonization or infection post-transplant. Data were analyzed using Stata, v15 (StataCorp), and GraphPad Prism, v8.0 (GraphPad Software). Categorical and continuous variables were compared using Fisher exact and Mann-Whitney U tests, respectively. Variables significant by univariate analysis at P ≤ .05 were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model to determine independent risk factors for MDR-E infection. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank test were used to estimate MDR-E infection-free survival and to compare curves between groups, respectively. Significance was defined as P ≤ .05 (2-tailed).

RESULTS

We consented 171 patients, 9 of whom were excluded because a perirectal swab was not collected (n = 6) or SOT was aborted (n = 3). Among 162 enrolled patients, 88, 70, and 4 were lung, liver, and small bowel recipients, respectively (Table 1). In the 90 days preceding transplant, 4 patients had a positive clinical culture for CefR-E.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Liver, Lung, and Small Bowel Transplant Recipients Gastrointestinally Colonized or Infected With Multidrug-Resistant-Enterobacterales

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 162) | Lung Transplant Patients (N = 88) | Liver Transplant Patients (N = 70) | Small Bowel Transplant Patients (N = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, median (range), years | 57 (21 to 74) | 58 (20 to 75) | 56 (21 to 74) | 35 (25 to 42) |

| Male sex | 59% (95) | 53% (46) | 66% (46) | 50% (2) |

| White race | 89% (145) | 89% (78) | 91% (64) | 75% (3) |

| Underlying diseases | ||||

| Diabetes | 7% (12) | 3% (3) | 13% (9) | 0% |

| Malignancy | 26% (42) | 17% (15) | 39% (27) | 0% |

| Previous organ transplant | 7% (12) | 4% (4) | 4% (3) | 0% |

| Hemodialysis pre-transplant | 7% (11) | 1% (1) | 14.3% (10) | 0% |

| Neutropenia | 2% (3) | 0% | 4.3% (3) | 0% |

| Pre-transplant conditions | ||||

| Hospitalization within 90 days | 39% (63) | 32% (28) | 49% (34) | 25% (1) |

| Surgery or invasive procedures within 90 days | 8% (13) | 6 | 7 | 0% |

| Mechanical ventilation pre-transplant | 7% (11) | 12% (11) | 0% | 0% |

| Median body mass index (range), kg/m2 | 26.0 (16.6 to 40.4) | 22.7 (12.9 to 27.2) | 28.7 (18.8 to 43.7) | 22.7 (18.9 to 27.3) |

| Days from admission to transplant | 1 (0 to 57) | 1 (0 to 81) | 1 (1 to 57) | 0.5 (0 to 2) |

| Colonization or infection due to multidrug-resistant bacteria prior to transplant | ||||

| Vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonization | 27% (42) | 21% (18) | 36% (24) | 0% |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization | 10% (16) | 16% (14) | 3% (2) | 0% |

| MDR-E infection or colonizationa | 2% (4) | 2% (2) | 3% (2) | 0% |

| Transplant and post-transplant characteristics | ||||

| Alemtuzumab | 23% (37) | 42% (37) | 0% | 0% |

| Thymoglobulin | 4% (7) | 0% | 4% (3) | 100% |

| Median units of red blood cell transfusion during transplant (range) | 4 (0 to 39) | 5 (1 to 51) | 4 (0 to 20) | 0 |

| Renal failure post-transplant | 5% (8) | 8% (7) | 1.4% (1) | 0% |

| Surgical reexploration or invasive procedure after transplant | 24% (39) | 24% (21) | 23% (16) | 50% (2) |

| Antibiotic exposure post-transplantb | ||||

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 31% (50) | 15% (13) | 51% (36) | 25% (1) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 41% (66) | 41% (36) | 39% (27) | 75% (3) |

| Cefazolin | 17% (28) | 26% (23) | 7.2% (5) | 0% |

| Second- and third-generation cephalosporin | 9% (15) | 6% (5) | 14% (10) | 0% |

| Cefepime | 54% (87) | 70% (62) | 36% (25) | 0% |

| Carbapenem | 4% (6) | 4.6% (4) | 2.9% (2) | 0% |

| Fluoroquinolone | 26% (43) | 30% (26) | 24% (17) | 0% |

| Metronidazole | 16% (26) | 18% (16) | 11% (8) | 50% (1) |

| Post-transplant outcomes | ||||

| Mortality rate at 6 months after transplant | 0.6% (1) | 0% | 1.4% (1) | 0% |

| MDR-E gastrointestinal colonization | ||||

| MDR-E colonization | 25% (40) | 26% (23) | 23% (16) | 25% (1) |

| CefR-E colonization | 17% (28) | 15% (13) | 20% (14) | 25% (1) |

| CRE colonization | 10% (17) | 14% (12) | 7% (5) | 0% |

| MDR-E infection | ||||

| MDR-E infection | 10% (17) | 10% (9) | 11% (8) | 0% |

| CefR-E infection | 4% (7) | 1% (1) | 9% (6) | 0% |

| CRE infection | 7% (12) | 10% (9) | 4% (3) | 0% |

Abbreviations: CefR-E, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales; CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; MDR-E, multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales.

aFour patients were infected with CefR-E before transplant: Escherichia coli (N = 2), Enterobacter cloacae complex (N = 1), and Citrobacter freundii (N = 1).

bFor patients with subsequent MDR-E infections, antibiotics were captured before the first onset of infection. For patients without MDR-E infections, antibiotics were captured up to 100 days after transplant.

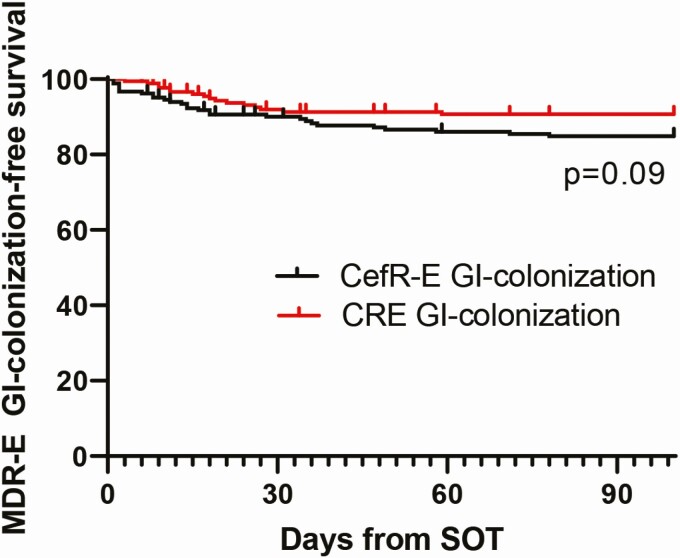

MDR-E GI Colonization

Perirectal swabs (N = 713) were obtained from 162 patients (mean, 4 swabs/patient). Twenty-five percent (40 of 162) of patients were colonized with MDR-E within 100 days post-transplant (CefR-E only, N = 23; CRE only, N = 12; both, N = 5; Figure 1). Seventy-five percent (3 of 4) of patients with positive pre-transplant clinical cultures for MDR-E were GI colonized by the same MDR-E post-transplant. Seventy-five percent (30 of 40) of patients had a positive MDR-E swab at the time of hospital discharge.

Figure 1.

MDR-E GI colonization-free survival after SOT. The Kaplan-Meier curve was stratified by CefR-E and CRE. The median times from transplant to detection of CefR-E and CRE colonization were 14 days (range, 1 to 83) and 17 days (range, 3 to 59), respectively (P = .96). Abbreviations: CefR-E, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales; CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; GI, gastrointestinal; MDR-E, multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales; SOT, solid organ transplantation.

Fifty-four MDR-E isolates (35 CefR-E, 19 CRE) were recovered from GI-colonized patients; >1 MDR-E was recovered from 28% (11 of 40) of GI-colonized patients. Klebsiella pneumoniae were the most common MDR-E (Table 2). Resistance determinants were evaluated in 91% (49 of 54) of GI-colonizing isolates using multiplex real-time PCR (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1). Fifty-two percent (16 of 31) of CefR-E carried blaCTX-M, and 72% (13 of 18) of CRE carried blaKPC.

Table 2.

Presence of Genes Encoding for Resistance Determinants Among Gastrointestinal-Colonizing Multidrug-Resistant-Enterobacterales

| A. CRE GI-Colonizing Strains | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRE | bla KPC | bla CTX-M | bla ESBL-SHV | bla AmpC | No Markers Identified | Isolates Not Available | Multiple Determinants |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 11) | 9 | 11 | 1 | 1This strain had truncated OmpK35 and OmpK36 porins by WGS | |||

| Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 3) | 32 | 1 | 1 | 2 One strain coharbored blaKPC and blaCTX-M, and 1 strain coharbored blaKPC and blaACT encoding AmpC | |||

| Klebsiella aerogenes (n = 2) | 2 | ||||||

| Enterobacter cloacae complex (n = 2) | 13 | 1 | 2 | Both strains harbored blaACT-2 encoding AmpC | |||

| 3One strain also coharbored blaKPC and blaCTX-M | |||||||

| Serratia marcescens (n = 1) | 14 | 4This strain harbored blasrt3 encoding AmpC (identified by WGS) | |||||

| B. CefR-E GI-Colonizing Strains | |||||||

| CefR-E | bla CTX-M | bla ESBL-SHV | bla ESBL-TEM | bla AmpC | No Markers Identified | Isolate Not Available | Note |

| K. pneumoniae (n = 8) | 51a | 41a | 11b | 1aOne strain coharbored blaCTX-M and blaESBL-SHV | |||

| 1bOne strain coharbored blaCTX-M and blaampC | |||||||

| K. oxytoca (n = 4) | 32a | 1 | 12a | 12b | 2aOne strain harbored both blaCTX-M and blaDHA-1 encoding AmpC | ||

| 2b WGS showed that this strain harbored blaOXY-2 | |||||||

| K. aerogenes (n = 1) | 1 | ||||||

| E. cloacae complex (n = 8) | 33 | 63 | 2 | 3Three strains harbored both blaCTX-M and blaAmpC | |||

| Enterobacter asburiae (N = 1) | 1 | ||||||

|

Citrobacter freundii complex (n = 4) and Citrobacter amalonaticus4b (n = 1) |

14a | 34a | 14b | 1 | All 3 C. freundii complex strains harbored blaCMY-2 | ||

| 4a One C. freundii complex strain coharbored blaCTX-M | |||||||

| 4b C. amalonaticus harbored blaSED (by WGS); this strain did not harbor blaCMY-2 | |||||||

| Escherichia coli (n = 6) | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Hafnia alvei (n = 1) | 1 | This strain harbored blaACC | |||||

| Proteus mirabilis (n = 1) | 1 | This strain harbored blaCMY-2 |

Genes were identified using multiplexed, real-time polymerase chain reaction assays. Note that 11 patients were colonized with >1 multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales (MDR-E). Four patients were colonized with 3 MDR-E (1 patient with 3 CR-E (patient CR-001), 1 patient with 1 CRE and 2 CefR-E (CR-41), and 1 patient with 3 CefR-E (CR-94)). Four patients were colonized with both CRE and CefR-E (patients CR-154, CR-155, CR-186, CR-194). Four patients were colonized with 2 CefR-E (CR-9, CR-50, CR-69, CR-134).

Abbreviations: CefR-E, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales; CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; GI, gastrointestinal; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

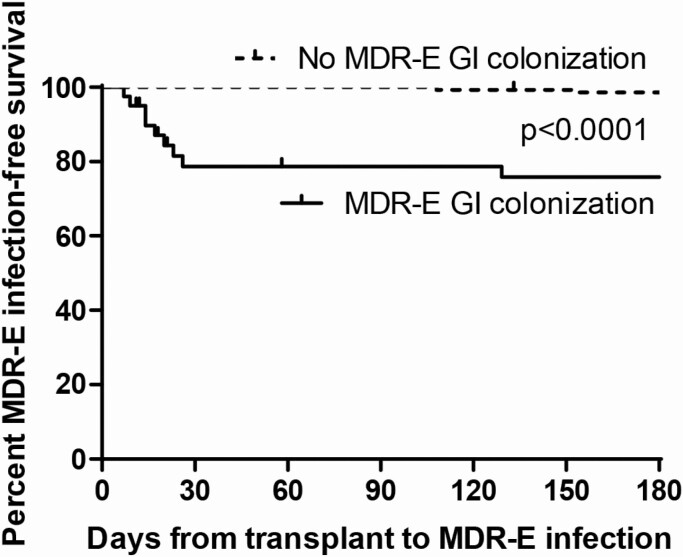

MDR-E Infections

Ten percent (17 of 162) of patients developed MDR-E infections within 6 months post-transplant, including CefR-E (N = 5), CRE (N = 10), and both CRE and CefR-E (N = 2) infections (Table 3, Supplementary Table 2, Figure 2). Thirty-five percent (14 of 40) of MDR-E colonizers and 2% (3 of 145) of noncolonizers developed MDR-E infection (P < .0001). The attack rate was higher following CRE colonization than CefR-E colonization (53% vs 21%, P = .049). Median times from detection of GI colonization to diagnosis of CefR-E and CRE infections were 5 days (1–58) and 8 days (0–162), respectively.

Table 3.

Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes, Microbiology, and Strain Data for Initial Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales

| Patient | MDR-E GI Colonization | MDR-E Infection | MDR-E Isolate(s) | Genetic Relationship (Colonizing vs Infecting Strains) | Recurrence(s) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR-001 | Yes | Urinary tract infection | CR-Klebsiella oxytoca | Colonizing (n = 2) vs infecting (n = 1) strains | No | Alive at 5.8 years after transplant |

| KPC-3 | 6 SNP | |||||

| CR-035 | Yes | Pneumonia | CR-Klebsiella pneumoniae | Colonizing (n = 1) vs infecting (n = 1) strains | Late recurrence | Alive at 5.5 years after transplant |

| CG258 | 3 SNP | |||||

| KPC-3 | ||||||

| CR-038 | Yes | Pneumonia | CR-K. pneumoniae | Colonizing (n = 2) vs infecting (n = 4) strains | Multiple early and late recurrences | Alive at 5.5 years after transplant |

| CG258 | 3 SNP (2–7) | |||||

| KPC-3 | ||||||

| CR-041 | Yes | Peritonitis | CR-K. oxytoca | Colonizing (n = 1) vs infecting (n = 2) strains | No | Alive at 5.4 years after transplant |

| KPC-3 | 5 SNP (3–8) | |||||

| CR-048 | Yes | Pneumonia and empyema | CR-K. pneumoniae | Colonizing (n = 4) vs infecting (n = 2) strains | Late recurrence | Died 3.9 years after initial infections (died from recurrent KPC-K. pneumoniae infection) |

| CG258 | 4 SNP (2–6) | |||||

| KPC-3 | ||||||

| CR-096 | No | Pneumonia | CR-K. pneumoniae | No GI colonization | Early recurrence | Died 75 days after initial infection (died from recurrent CR-K. pneumoniae infection)a |

| CG258 | Initial (n = 2) vs recurrent infecting (n = 1) strains | |||||

| KPC-3 | 8 SNP (2–8) | |||||

| CR-145 | Yes | Chest wall infection | CR-K. quasi-pneumoniae | N/A (colonizing isolate not available for whole-genome sequencing) | No | Alive at 4.7 years after transplant |

| ST1224 | ||||||

| DHA-1 | ||||||

| CR-148 | No | Pneumonia | CR-K. pneumoniae | N/A | No | Alive at 4.7 years after transplant |

| CG258 | ||||||

| KPC-3 | ||||||

| CR-192 | Yes | Tracheo-bronchitis then pneumonia | CR-K. pneumoniae | Colonizing (n = 1) vs infecting (n = 2: 1 initial and 1 early recurrent) strains | Early and multiple late recurrences | Alive at 4.2 years after transplant |

| CG258 | 1 SNP (0–1) | |||||

| KPC-3 | ||||||

| CR-214 | Yes | Pneumonia | CR-K. pneumoniae | Colonizing (n = 1) vs infecting (n = 1) strains | No | Alive at 3.9 years after transplant |

| CG258 | 1 SNP | |||||

| KPC-8 | ||||||

| CR-047b | Yes | Urinary tract infection (CefR-E) and bacteremia CRE)c | Urine: CefR-E. cloacae | Colonizing (n = 1) vs infecting (n = 2) strains | Late recurrence | Alive at 5.4 years after transplant |

| Pre-transplant infection | CTX-M-15 and ACT-16 | 16 SNP (13–20) | ||||

| CefR-Enterobacter cloacae | Blood: CR-E. cloacae | |||||

| CTX-M-15 and ACT-16 | ||||||

| CR-186c | Yes | Bacteremia | CefR-K. pneumoniae | Colonizing (n = 2) vs infecting (n = 4: 1 initial and 3 early recurrent) strains | Early recurrence | Alive at 4.3 years after transplant |

| ST-38 | 2 SNP (0–6) | |||||

| Extended-spectrum β-lactamases -SHV | ||||||

| CR-183 | Yes | Pneumonia | CefR-K. oxytoca | Colonizing (n = 1) vs infecting (n = 1) strains | Early recurrence | Alive at 4.3 years after transplant |

| CTX-M | 14 SNP | |||||

| CR-070 | Nod | Pyelonephritis | CefR- Escherichia coli | Pre-transplant (n = 1) and post-transplant strains (n = 1) | Late recurrence | Alive at 5.2 years after transplant |

| CTX-M-15 | 3 SNP | |||||

| CR-128 | No | Intraabdominal abscess | CefR-E. coli | N/A | Died | Died from persistent infection (7 days after diagnosis) |

| CXT-M | ||||||

| CR-123 | Yes | UTI | CefR-K. pneumonia | Colonizing (n = 1) and infecting (n = 1) strains | No | Alive at 4.9 years after transplant |

| ST11 | 3 SNP | |||||

| CTX-M-14 | ||||||

| CR-013 | Yes | UTI | CefR-K. oxytoca | Colonizing (n = 2) vs infecting strains (n = 1) | Early recurrent infection | Alive at 5.6 years after transplant |

| DHA-1, OXY2-5, CTX-M-27 | 16 SNP (3–19) |

Definitions: early recurrence: culture positivity for the same CRE or CefR-E within 90 days of the initial clinical culture; late recurrence: culture positivity for the same CRE or CefR-E >90 days of the initial culture; duration of GI colonization: if a patient had ≥2 CefR-E or CRE GI colonization at 2 consecutive weeks immediately before discharge, the duration of GI colonization is denoted as greater than or equal to the number of days from the first date to the last date of GI colonization.

Abbreviations: CefR-E, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales; CG, core group; cg, core genome; CR, carbapenem-resistance; CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; GI, gastrointestinal; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases; MDR-E, multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales; N/A, not applicable; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; ST, strain type; UTI, urinary tract infection.

aThis patient (CR-096) died from septic shock; blood and lung cultures performed at autopsy grew CR-K. pneumoniae, and there was evidence of bowel necrosis with transmural gram-negative rod infiltration of the bowel wall.

bCR-047 was GI colonized with CefR-E. cloacae complex then developed E. cloacae urosepsis; the urine isolate was CefR, but the blood isolate was CR. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) showed that CefR and CE-Enterobacter cloacae complex shared blaACT and CTX-M-15. Mechanism of CR is unclear from WGS data.

cCR-186 was GI colonized with CefR-K. pneumoniae 8 days after solid organ transplantation then with CR-K. pneumoniae 7 days later. She developed CefR-K. pneumoniae intraabdominal infection and bacteremia that was treated with drainage and meropenem. Twenty-six days after the initial infection (11 days after CR-K. pneumoniae GI colonization), she developed recurrent a intraabdominal abscess due to CR-K. pneumoniae; the second isolate acquired a new truncation of porin OmpK36.

dCR-070 had UTI and bacteremia due to CefR-E. coli 23 days before transplant.

Figure 2.

MDR-E infection-free survival after solid organ transplantation. The Kaplan-Meier curve was stratified by MDR-E GI colonization status. Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; MDR-E, multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales.

Risk factors for MDR-E infections identified using univariate analyses are presented in Table 4A. By multivariate analysis, GI colonization and higher recipient body mass index were independent risk factors for both MDR-E and CefR-E infections (Table 4A and B). CRE GI colonization and surgical reexploration after transplant were independent risk factors for CRE infection (Table 4C).

Table 4.

Risk Factors for Multidrug-Resistant-Enterobacterales Infections

| A. Risk factors for MDR-E infections | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factor | Univariate Analyses | Multivariate Analyses | |||

| Infection (N = 17) | No Infection (N = 145) | P Value | P Values | OR (95% CI) | |

| Hospitalization within 90 days before transplant | 65% (11) | 36% (52) | .03 | .25 | ... |

| Recipient’s BMI before transplant | 31 (17–44) | 26 (17–36) | .026 | .004 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) |

| Post-transplant MDR-E colonization | 82% (14) | 18% (26) | <.0001 | <.0001 | 29.4 (6.5–132.5) |

| Reexploration after transplant | 47% (9) | 21% (30) | .006 | .134 | ... |

| B. Risk factors for CefR-E infectionsa | |||||

| Risk Factor | Univariate Analyses | Multivariate Analyses | |||

| Infection (N = 5) | No Infection (N = 145) | P Value | P Value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Hospitalization within 90 days before transplant | 80% (4) | 36% (52) | .065 | NA | NA |

| Recipient’s BMI before transplant | 36 (23–44) | 26 (17–36) | .03 | .004 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) |

| CefR-E colonization | 80% (4) | 15% (21) | .003 | .008 | 88 (3.2-2404) |

| Reexploration after transplant | 20% (1) | 21% (30) | 1.0 | NA | NA |

| C. Risk factors for CRE infectionsb | |||||

| Risk Factor | Univariate Analyses | Multivariate Analyses | |||

| Infection (N = 10) | No Infection (N = 145) | P Value | P Value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Hospitalization within 90 days before transplant | 50% (5) | 36% (52) | .50 | ... | ... |

| Recipient’s BMI before transplant | 29 (17–35) | 26 (17–36) | .11 | ... | ... |

| CRE colonization | 80% (8) | 5% (8) | <.0001 | <.0001 | 74.7 (11–508.4) |

| Re-exploration after transplant | 70% (7) | 21% (30) | .002 | .016 | 10.2 (1.6–66.4) |

The factors previously associated with MDR infections (listed in Supplementary Method 3) were assessed as risk factors for MDR-E infections. This table only includes factors found to be associated with MDR-E, CefR-E, or CRE infections by univariate analyses at P < .05.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CefR-E, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales; CI, confidence interval; CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; MDR-E, multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

a The 12 patients infected with CRE were excluded from this analysis.

bThe 7 patients infected with CefR-E were excluded from this analysis.

Treatment and Outcomes of MDR-E Infections

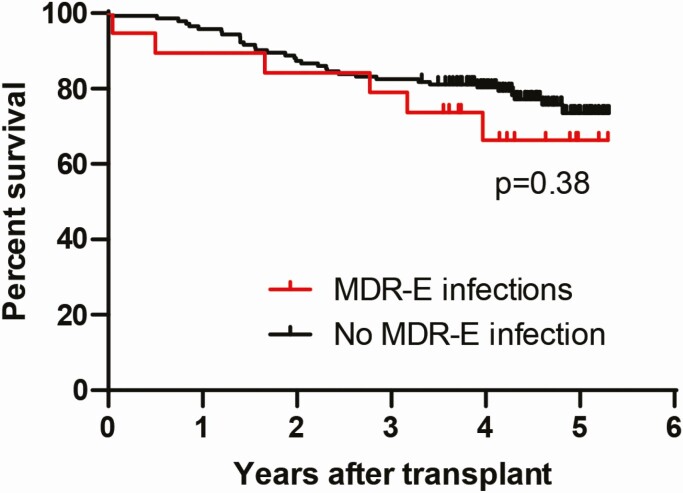

Patients with CRE infections were treated with ≥1 in vitro active antibacterial agent, most commonly ceftazidime-avibactam or meropenem-vaborbactam (83%, 10 of 12) (Supplementary Table 2). Patients with CefR-E infections were most commonly treated with a carbapenem (57%, 4 of 7). Thirty- and 90-day mortality rates after initial MDR-E infections were 6% (1 of 17) and 12% (2 of 17), respectively. Survival at median 4.3 years follow-up post-transplant did not significantly differ among patients with or without MDR-E infections (Figure 3). MDR-E–infected patients had significantly longer hospitalizations than those who were not MDR-E–infected (median 31 vs 17 days, P = .015). There were no significant differences in MDR-E infection outcomes among liver and lung recipients.

Figure 3.

Long-term survival of solid organ transplantation patients stratified by the presence or absence of MDR-E infections encountered within 6 months of transplant. Median follow-up of patients was 4.3 years (0.04 to 5.3 years) post-transplant. At the last follow-up, the mortality rate of patients with MDR-E infections was 29% (5 of 17) vs 23% (34 of 145) among patients without MDR-E infections (P = .56). Abbreviation: MDR-E, multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales.

Sixty-two percent (10 of 16) of patients who survived initial MDR-E infection had recurrent positive clinical cultures (colonization or infection), including 4 patients with early recurrent (≤90 days of initial infection), 4 patients with late recurrent (>90 days), and 2 patients with both early and late recurrent cultures (Table 5). Forty-four percent (7 of 16) of those who survived initial MDR-E infection developed recurrent infections (4 early, 3 late recurrence). Recurrent infections occurred in patients originally infected with CefR (N = 4) and CRE (N = 3) after as long as 3.9 years. One patient (CR-186) who was initially GI colonized and infected with CefR-K. pneumoniae was treated with a carbapenem. He subsequently was GI colonized with CR-K. pneumoniae with a newly truncated ompK36 porin and later developed an intraabdominal infection due to this strain (26 days after the initial CefR-K. pneumoniae infection).

Table 5.

Clinical Characteristics, Microbiology, and Resistance Mechanisms of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales Responsible for Late Recurrent Colonization or Infection

| Patient | Onset from Initial MDR-E Infection | Infection or Colonization | Type of MDR-E | Mechanisms of MDR-E Resistance | Median (Range) #cgSNP Between Initial and Recurrent Isolates | Outcome of Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR-035 | 483 days | Purulent tracheobronchitis | CR-Kp | KPC-3, ST258 | Initial (n = 1) vs late recurrent (n = 1) strains | No further recurrence |

| 4 SNP | Alive | |||||

| CR-048 | 1213, 1268, 1274, 1304, and 1421 days | Bacteremia and pneumonia | CR-Kp | KPC-3, ST258 | Initial (n = 2) vs late recurrent (n = 1) strains | Persistent colonization and multiple recurrent infections |

| 12 (11–13) SNP | Died 1422 days after initial infection (died from recurrent infection due to ceftazidime-avibactam–resistant KPC46-Kp) | |||||

| CR-038 | 457, 583, 618, and 759 days | Respiratory and urinary colonization | CR-Kp | KPC-3, ST258 | Initial (n = 4) vs late recurrent (n = 3) strains | Multiple recurrent colonization |

| 5 (1–7) SNP | Alive | |||||

| CR-1092 | 191, 338, and 401 days | Respiratory colonization | CR-Kp | KPC-3, ST258 | Initial (n = 1) vs late recurrent (n = 3) strains | Multiple recurrent colonization |

| 2 (1–4) SNP | Alive | |||||

| CR-070 | 285, 911, 957, and 1224 days | Urinary tract infection | CefR-Escherichia coli | CTX-M15 | Initial (n = 2) vs late recurrent (n = 2) strains | Multiple recurrent colonization |

| 17 (7–18) SNP | Alive | |||||

| CR-047 | 202 days | Urinary colonization | CefR-ECC | CefR-ECC | Isolate not available | No further recurrence |

| CTX-M-15 and ACT-16 group | Alive |

Late recurrent colonization or infection was defined as >90 days after the initial infection with the same MDR-E.

Abbreviations: CefR-E, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales; cg, core genome; CR, cephalosporin-resistant; ECC, Enterobacter cloacae complex; Kp, Klebsiella pneumoniae; Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; MDR-E, multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

WGS and Comparative Genomics of MDR-E Isolates

Seventy-six GI-colonizing and infection-causing MDR-E isolates from 28 patients underwent short-read Illumina WGS (Supplementary Figure 1, Table 3). Thirty-eight isolates were CG258 CR-K. pneumoniae; the remaining isolates were other CRE and CefR-E (n = 19 each) of various species. Five patients were colonized or infected with ceftazidime-avibactam–resistant CG258 K. pneumoniae that carried KPC-31 (KPC-3 with D179Y, n = 3), KPC-8 (KPC-3 with V240G, n = 1), or KPC-46 (KPC-3 with S171P, n = 1; Supplementary Table 3). Each KPC-carrying, ceftazidime-avibactam–resistant isolate was misidentified by the clinical microbiology laboratory as an ESBL-producer based on susceptibility phenotype. One CR-Enterobacter isolate carried the plasmid-borne polymyxin-resistance gene mcr-9. Twenty-five percent (3 of 12) of patients colonized by CG258 CR-K. pneumoniae carried a strain with mutant ompK36; 100% (12 of 12) of CG258 CR-K. pneumoniae harbored yersiniabactin and colibactin virulence genes.

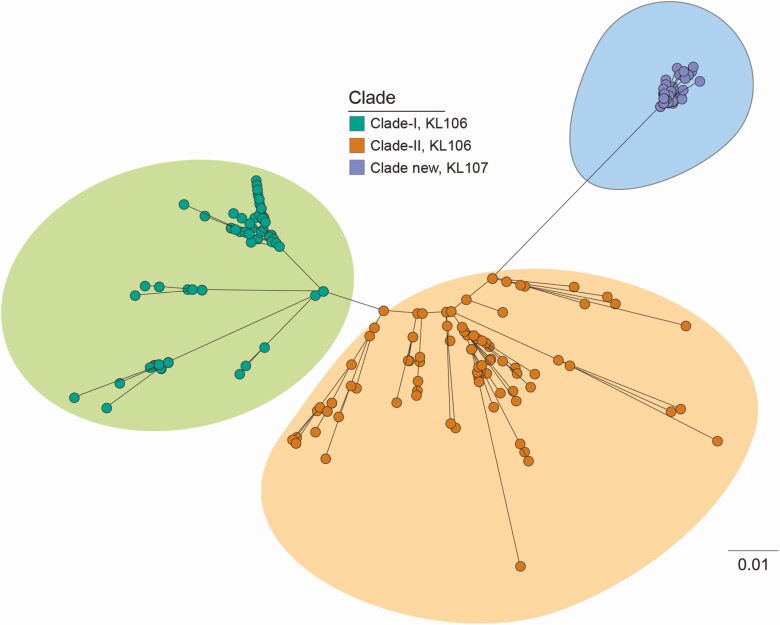

In intrapatient comparisons, GI-colonizing and GI-infecting CG258 K. pneumoniae from each of 5 patients differed by a median of 3 core genome SNPs (range, 0 to 8; Table 3, Supplementary Table 3). Initial infecting CG258 CR-K. pneumoniae from 4 patients differed from their late recurrent colonizing or infecting isolates by a median of 5 core genome SNPs (range, 1–13; Table 5, Supplementary Table 4). In interpatient comparisons, initial CG258 K. pneumoniae from 12 patients differed by a median of 10 core genome SNPs (range, 1–18; Supplementary Table 4). CG258 K. pneumoniae isolates clustered within a novel clade II sublineage, which differed from clade II and clade I lineages detected at our center from 2012 to 2015 (Figure 4). Data on intrapatient SNP differences between GI-colonizing and GI-infecting non-CG258 CRE and CefR-E are presented in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 5.

Figure 4.

Core genome phylogeny of CG258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Comparisons of core genome phylogeny enabled us to put CG258 K. pneumoniae isolates from our solid organ transplantation recipients into the context of broader institutional epidemiology. Isolates recovered at our center during the study period clustered within a novel clade II sublineage (blue oval), which differed from clade II (orange circles) and clade I (green circles) lineages from previous years.

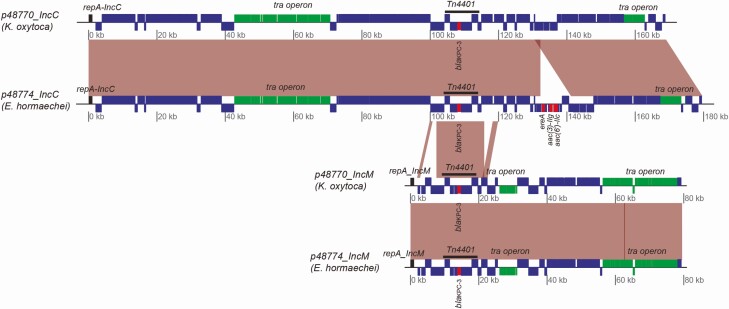

Patient CR-001 was GI colonized with CR-Klebsiella oxytoca and CR-Enterobacter hormaechei 7 and 48 days after SOT, respectively. Hybrid assembly of Nanopore and Illumina WGS revealed that the strains shared 2 KPC-3 plasmids belonging to the IncC and IncM replicon groups (Figure 5). IncC plasmids were 169.0 kb and 179.7 kb in length and shared >99.9% nucleotide identity. Extra content of the E. hormaechei IncC plasmid harbored macrolide (ereA) and aminoglycoside (aac(3)-IIg, aac(6’)-IIc) resistance genes. IncM plasmids in the strains were virtually identical.

Figure 5.

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) plasmids derived from Nanopore and Illumina hybrid assembly of Klebsiella oxytoca and Enterobacter hormaechei strains from patient CR-001. The strains shared 2 KPC-3 plasmids belonging to the IncC and IncM replicon groups. IncC plasmids were 169.0 kb and 179.7 kb in length, with >99.9% nucleotide identity. The extra 10.7 kb of the E. hormaechei IncC plasmid harbored additional genes encoding macrolide (ereA) and aminoglycoside (aac (3)-IIg and aac(6’)-IIc) resistance determinants. IncM KPC-3 plasmids were virtually identical.

Discussion

This study of MDR-E GI colonization following liver, lung, and small bowel transplants was unique for its long-term patient follow-up. Twenty-five percent of SOT recipients were GI colonized by MDR-E within 100 days post-transplant. GI colonization was the most significant independent risk factor for MDR-E infections in the first 6 months following transplant. Mortality among MDR-E–infected patients was surprisingly low (6% at 30 days post-infection) compared with previous studies of SOT recipients at our center and others [13–15, 23, 24]. However, encouraging mortality data were counterbalanced by recurrent infections in 44% of survivors; 43% of recurrent infections were late, occurring 285 days to 3.9 years after initial infections. Initial and recurrent infections were caused by GI-colonizing strains, as revealed by core genome phylogenetic analyses. Moreover, WGS data suggested that there was unrecognized transmission of a novel sublineage of CG258 CR-K. pneumoniae at our center, as well as horizontal transfer of plasmids bearing resistance determinants. In summary, MDR-E presented an ongoing problem among SOT recipients, even as clinical outcomes and molecular epidemiology evolved. Findings indicate that MDR-E surveillance may be useful in our SOT program.

Ten percent of SOT recipients developed an MDR-E infection within 6 months post-transplant, including 35% of those who were GI colonized and only 2% who were not colonized (P < .0001). Our finding that MDR-E colonization predisposed to invasive infections corroborates earlier reports in liver and lung transplant recipients [9–11]. MDR-E colonization, infection, and attack rates in our study did not differ between colonized liver and lung recipients. Likewise, colonization and infection rates by CRE or CefR-E did not differ significantly. However, the attack rate following CRE colonization was higher than after CefR-E colonization (53% vs 21%, P = .049). Reasons for this finding are unclear but they may reflect unrecognized patient-related factors or differences in strain virulence. Surgical reexploration was an independent risk factor for CRE but not CefR-E infection, suggesting that patients with the former may have had more complicated post-transplant courses. CRE carriage has been associated with intestinal dysbiosis and metabolic alterations, which can compromise intestinal epithelial barrier function and enable bacterial translocation [25]. Genes that encode yersiniabactin and colibactin virulence determinants were found in all of our CG258 CR-K. pneumoniae isolates. Yersiniabactin enables bacteria to sequester iron from infected tissues, bypassing iron-deprivation host defense mechanisms [26]. Colibactin promotes gut colonization by CRE [26] and is required for invasive disease [27]. Despite differences in attack rates, both CRE and CefR-E colonization were independent risk factors for invasive infections. In keeping with previous reports [6–9], MDR-E–infected patients had longer hospitalizations than noninfected SOT recipients (median 31 vs 17 days, P = .015).

Ninety-day mortality following CefR-E and CRE infections was 14% and 8%, respectively. Seventy-one percent of patients with MDR-E infections were still alive at the end of our study compared with 77% of patients who were not MDR-E–infected (P = .56). The low mortality is particularly striking since types of infection observed in our study (pneumonia, intraabdominal, bacteremia) are typically associated with poor outcomes [13, 28]. It is likely that mortality rates, at least in part, reflect availability of new, CRE-active antibiotics [17, 18]. Eighty-three percent and 42% of patients infected with CefR-E and CRE, respectively, had the same organism causing recurrent GI colonization or infection as late as 3.9 years after the initial infection. ESBL-E and CRE GI carriages have been reported to persist for as long as 1.1 and 2.75 years, respectively [29, 30]. Factors that account for chronic colonization and late recurrent infections by MDR-E are unclear [31]. Antibiotic exposure is a well-established risk factor for MDR-E colonization; lung and small bowel recipients were maintained on lifelong trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis. Patients were not hospitalized immediately prior to recurrent infections, but we cannot rule out outpatient antibiotic prescriptions. It is also possible that immunosuppression limited eradication of MDR-E from the GI tract and other sites.

MDR-E represented several Enterobacterales spp. that harbored various cephalosporin- and carbapenem-resistance determinants. Twenty-eight percent of patients were colonized with >1 MDR-E. In keeping with US epidemiology, KPCs were the most common carbapenemases and CTX-M were the most common ESBLs [32]. In patient CR-186, CR-K. pneumoniae emerged in GI-colonizing and infection-causing CefR-K. pneumoniae strains through a truncation of ompK36 porin. New β-lactamases were acquired in longitudinal MDR-E isolates from other patients. Patient CR-001 was GI colonized with CR-K. oxytoca and CR-E. hormaechei strains that shared 2 KPC-3–bearing plasmids, as evident by long-read WGS, suggesting horizontal transfer. In several unique patients, the same resistance determinants (eg, KPC-3, CTX-M) were detected in different Enterobacterales spp., further supporting horizontal spread. Ceftazidime-avibactam–resistant CG258 K. pneumoniae carrying KPC-3 variants with Ω-loop mutations that function as ESBLs were identified in 5 patients [33, 34]. Clinical microbiology laboratories that screen for CRE might misidentify Enterobacterales carrying such KPC variants. One patient was infected with ceftazidime-avibactam–resistant CG258 K. pneumoniae with a KPC-3 variant in the absence of prior ceftazidime-avibactam exposure, suggestive of nosocomial strain acquisition.

WGS revealed that colonizing and infecting CG258 K. pneumoniae isolates from a given patient differed by a median of 3 core genome SNPs, and initial infecting and late recurrent CG258 K. pneumoniae differed by a median of 5 core genome SNPs. Initial infecting CG258 K. pneumoniae from unique patients differed by a median of 10 core genome SNPs. These findings were consistent with SNP evolution rates of 3.8 to 10 per genome per year described in previous studies [35–37]. Intrapatient SNP differences between isolates of other K. pneumoniae clonal groups or Enterobacterales species were also consistent with those reported previously for closely related strains [9]. CG258 K. pneumoniae in our study were from a novel clade II sublineage that differed from clade II or clade I strains previously detected at our center, suggesting cryptic introduction and transmission of the lineage (Figure 4). These observations cast doubt on the effectiveness of (and/or full compliance with) universal glove and gown precautions that were in place for SOT recipients. In a recent multicenter study, universal gowning was not associated with reduced acquisition of antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria [38]. Perirectal VRE surveillance was also standard in our program, drawing into question ancillary benefits of this practice in limiting the spread of MDR-E or other antibiotic-resistant bacteria. We did not find an association between CRE colonization or infection and post-transplant endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or endoscopies, ruling out transmission by contaminated devices [39, 40].

Caution must be exercised in extrapolating our experience in this single-center study to other programs. We surveyed MDR-E GI colonization for up to 100 days after SOT but we did not systematically evaluate durations of long-term GI colonization or perform screening pre-SOT. Nevertheless, we documented that MDR-E persisted in clinical samples from 5 patients for at least 1 to 3.9 years. Four percent (4 of 156) of patients screened within 48 hours post-transplant carried MDR-E, suggesting that they may have been colonized pre-transplant. We relied on perirectal swabs cultured on selective chromogenic agar for screening. As such, we may not have recovered MDR-E that were noncultivable or present below levels of detection, as might have been identified by PCR screening. Finally, we did not enroll kidney transplant recipients. In a pilot study of 17 kidney recipients, none were GI-colonized; these patients were hospitalized for a median of 2 days, making nosocomial acquisition of MDR-E unlikely.

High MDR-E colonization and infection rates, links between colonization and invasive infection, and evidence of genetic relatedness between colonizing and infection-causing strains provide rationale for routine surveillance of liver, lung, and small bowel recipients. Surveillance for MDR-E carriage is less likely to be useful at hospitals in which these pathogens are uncommon, highlighting the importance of understanding local epidemiology. In our antibiogram during the enrollment period, 18% and 14% of K. pneumoniae and 9% and 0% of Escherichia coli were CefR and CR, respectively. Knowing that a given SOT recipient is colonized with CefR-E or CRE might inform empiric antibiotic treatment at early indication of infection or trigger investigations and measures to combat nosocomial outbreaks. At the same time, surveillance and WGS data may detect changes in institutional genomic epidemiology and/or emergence of novel antibiotic resistance determinants. Targeting SOT recipients for surveillance may also gather more broadly relevant insights into CefR-E and CRE prevalence and dissemination. In this regard, SOT recipients could serve as “canaries in the coal mine” for other patient populations and high-risk hospital units. Finally, it is reasonable to assume that once colonized by MDR-E, immunosuppressed patients remain colonized.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the patients who participated in this study, research staff (Brett Wildfeuer, Diana Pakstis, Julie Paronish, and Josh Kohl) who assisted with recruitment and review of medical records, and Guojun Liu for DNA extraction and preparation for whole-genome sequencing.

Financial support. The CREST study was supported in part by awards from the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (to M. H. N., National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant UM1AI104681) and the National Institutes of Health (R21AI128338 to M. H. N. and R01AI090155 to B. N. K.).

Potential conflicts of interest. R. K. S. has been awarded investigator-initiated research grants from Merck, Shinogi, and Venatorx; has served on advisory boards for Entasis, Summit, Utility, Menarini, Merck, Shionogi, and Venatorx; and has served as a speaker for Menarini. C. J. C. has been awarded investigator-initiated research grants from Astellas, Merck, Melinta, and Cidara for studies unrelated to this project; has served on advisory boards or consulted for Astellas, Merck, the Medicines Company, Cidara, Scynexis, Shionogi, Qpex, and Needham & Company; and has spoken at symposia sponsored by Merck and T2Biosystems. MHN has been awarded investigator-initiated research grants from Astellas, Merck, Pulmocide, Scynexis for studies unrelated to this project, served on advisory boards or consulted for Astellas, Pulmocide and Scynexis. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All other authors report no potential conflicts. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18:268–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Duin D, Doi Y. The global epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence 2016; 1–10. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1222343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ohana S, Leflon V, Ronco E, et al. Spread of a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain producing a plasmid-mediated ACC-1 AmpC beta-lactamase in a teaching hospital admitting disabled patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:2095–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woodford N, Tierno PM Jr, Young K, et al. Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing a new carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamase, KPC-3, in a New York medical center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004; 48:4793–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carrër A, Lassel L, Fortineau N, et al. Outbreak of CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in the intensive care unit of a French hospital. Microb Drug Resist 2009; 15:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alevizakos M, Mylonakis E. Colonization and infection with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae in patients with malignancy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2017; 15:653–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bert F, Larroque B, Paugam-Burtz C, et al. Pretransplant fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and infection after liver transplant, France. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:908–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilkowski P, Gajko K, Marczak M, et al. Clinical significance of gastrointestinal carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae-producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in kidney graft recipients. Transplant Proc 2018; 50:1874–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Macesic N, Gomez-Simmonds A, Sullivan SB, et al. Genomic surveillance reveals diversity of multidrug-resistant organism colonization and infection: a prospective cohort study in liver transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:905–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Errico G, Gagliotti C, Monaco M, et al. ; SInT Collaborative Study Group . Colonization and infection due to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in liver and lung transplant recipients and donor-derived transmission: a prospective cohort study conducted in Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019; 25:203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giannella M, Bartoletti M, Morelli MC, et al. Risk factors for infection with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae after liver transplantation: the importance of pre- and posttransplant colonization. Am J Transplant 2015; 15:1708–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lübbert C, Becker-Rux D, Rodloff AC, et al. Colonization of liver transplant recipients with KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with high infection rates and excess mortality: a case-control analysis. Infection 2014; 42:309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clancy CJ, Chen L, Shields RK, et al. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of bacteremia due to carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2013; 13:2619–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wong D, van Duin D. Carbapenemase-producing organisms in solid organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2019; 24:490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Winters HA, Parbhoo RK, Schafer JJ, Goff DA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacterial infections in adult solid organ transplant recipients. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pereira MR, Scully BF, Pouch SM, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2015; 21:1511–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Chen L, et al. Ceftazidime-avibactam is superior to other treatment regimens against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 61:e00883–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shields RK, McCreary EK, Marini RV, et al. Early experience with meropenem-vaborbactam for treatment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:667–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing M100, 30th edition. Wayne, PA: CLSI, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chavda KD, Satlin MJ, Chen L, et al. Evaluation of a multiplex PCR assay to rapidly detect Enterobacteriaceae with a broad range of β-lactamases directly from perianal swabs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:6957–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen L, Chavda KD, Mediavilla JR, et al. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of an epidemic KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 clone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:3444–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/infectiontypes.html. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Satlin MJ, Jenkins SG, Walsh TJ. The global challenge of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in transplant recipients and patients with hematologic malignancies. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:1274–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Santoro-Lopes G, de Gouvêa EF. Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections after liver transplantation: an ever-growing challenge. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:6201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Korach-Rechtman H, Hreish M, Fried C, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis in carriers of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. mSphere 2020; 5:e00173–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wisgrill L, Lepuschitz S, Blaschitz M, et al. Outbreak of yersiniabactin-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019; 38:638–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lu MC, Chen YT, Chiang MK, et al. Colibactin contributes to the hypervirulence of pks+ K1 CC23 Klebsiella pneumoniae in mouse meningitis infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017; 7:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Delden C, Blumberg EA; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice . Multidrug resistant gram-negative bacteria in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2009; 9 Suppl 4:S27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Birgand G, Armand-Lefevre L, Lolom I, Ruppe E, Andremont A, Lucet JC. Duration of colonization by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae after hospital discharge. Am J Infect Control 2013; 41:443–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zimmerman FS, Assous MV, Bdolah-Abram T, Lachish T, Yinnon AM, Wiener-Well Y. Duration of carriage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae following hospital discharge. Am J Infect Control 2013; 41:190–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Fallon E, Gautam S, D’Agata EM. Colonization with multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria: prolonged duration and frequent cocolonization. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:1375–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. David van Duin CAA, Komarow L, Chen L, et al. ; for the Multi-Drug Resistant Organism Network Investigator . Molecular and clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in the USA (CRACKLE-2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:731–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haidar G, Clancy CJ, Shields RK, Hao B, Cheng S, Nguyen MH. Mutations in blaKPC-3 that confer ceftazidime-avibactam resistance encode novel KPC-3 variants that function as extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61:e02534–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shields RK, Chen L, Cheng S, et al. 2017. Emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance due to plasmid-borne blaKPC-3 mutations during treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61:e02097–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jousset AB, Bonnin RA, Rosinski-Chupin I, et al. A 4.5-year within-patient evolution of a colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae sequence Type 258. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:1388–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moradigaravand D, Martin V, Peacock SJ, Parkhill J. Evolution and epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United Kingdom and Ireland. mBio 2017; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mathers AJ, Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing K. pneumoniae at a single institution: insights into endemicity from whole-genome sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:1656–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harris AD, Morgan DJ, Pineles L, Magder L, O’Hara LM, Johnson JK. Acquisition of antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria in the Benefits of Universal Glove and Gown (BUGG) cluster randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:431–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Muscarella LF. Risk of transmission of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and related “superbugs” during gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6:457–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marsh JW, Krauland MG, Nelson JS, et al. Genomic epidemiology of an endoscope-associated outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing K. pneumoniae. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0144310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.