Abstract

Sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization and improve symptoms among patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, when compared to the gold-standard angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, enalapril. In the 5 years since the publication of the results of PARADIGM-HF, further insight has been gained into integrating a neprilysin inhibitor into a comprehensive multi-drug regimen, including a renin-angiotensin aldosterone system (RAS) blocker. Here we review current understanding of the effects of sacubitril/valsartan and highlight expected developments over the next 5 years, including potential new indications for use. We additionally provide a practical, evidence-based approach to the clinical integration of sacubitril/valsartan among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Keywords: heart failure, neprilysin inhibition, sacubitril/valsartan

Introduction

In 2014, the PARADIGM-HF trial (Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) established that the combination of the neprilysin inhibitor pro-drug, sacubitril, and valsartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker [ARB], was superior to the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), enalapril, in reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic HFrEF (1). Clinical practice guidelines have since afforded sacubitril/valsartan a class I recommendation as a replacement for an ACEi (Online ref 1,2).

Subsequent analyses of PARADIGM-HF and new trials have provided new information about how neprilysin inhibition works and how sacubitril/valsartan can be used in practice. Further trials are currently underway, examining whether neprilysin inhibition may be valuable in other groups of patients such as after an acute myocardial infarction.

How Does Neprilysin Inhibition Work?

Neprilysin Substrates.

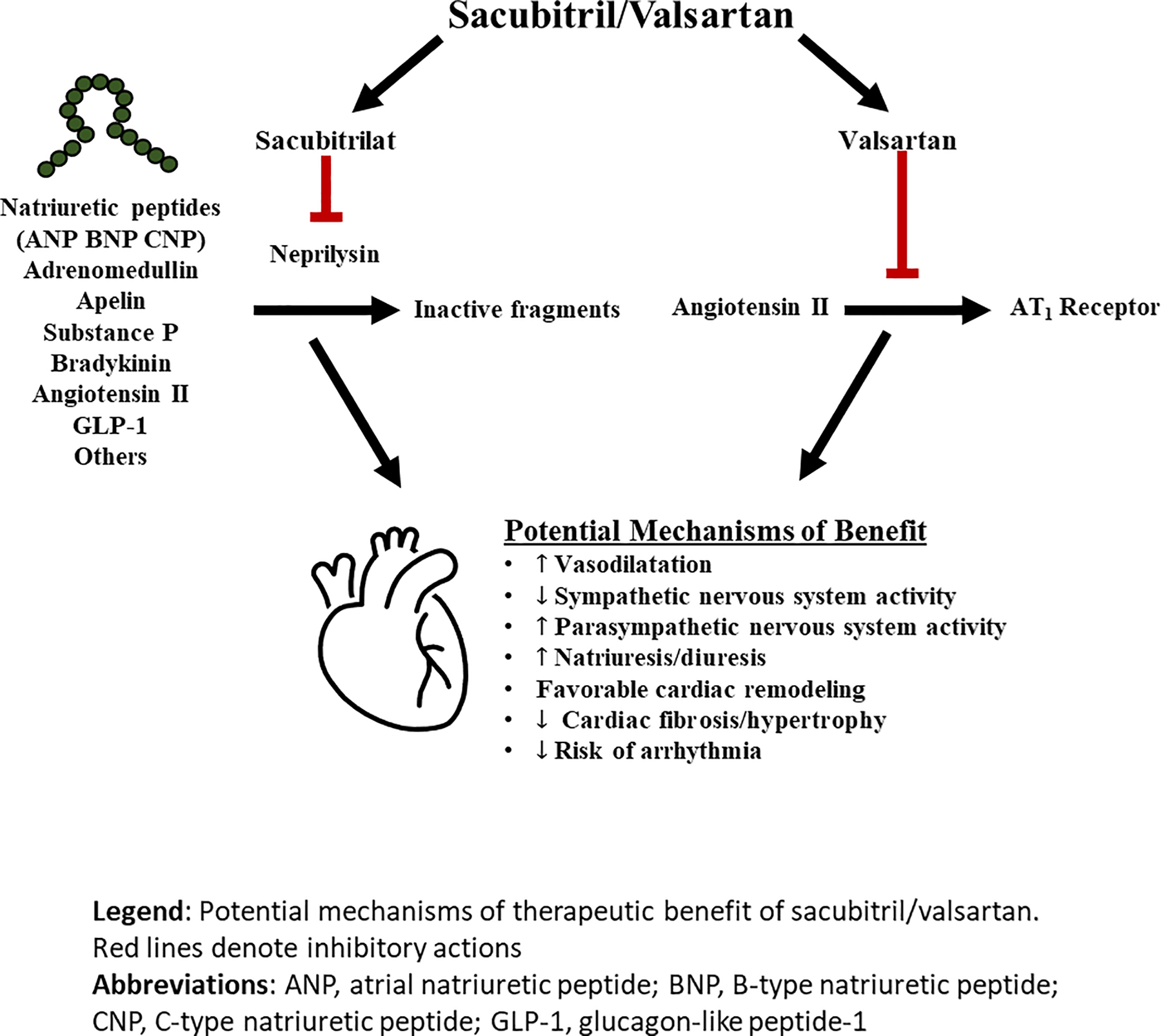

Despite the findings of PARADIGM-HF, the exact mechanisms underlying the therapeutic benefit of neprilysin inhibition are not entirely certain. The substrates for neprilysin are multifarious, and include the biologically active natriuretic peptides, adrenomedullin, endothelin, angiotensin II, substance P, among others, and it is unclear which of these substrates, or combination of substrates, are responsible for the benefit observed (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1:

Mechanism of action of sacubitril/valsartan

Red lines denote inhibitory actions.

Abbreviations: ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CNP, C-type natriuretic peptide.

Recent biomarker-based mechanistic studies have provided further insight into potential pathways that may be relevant to the observed benefits with ARNI. Compared with enalapril, treatment with sacubitril/valsartan in PARADIGM-HF was associated with an increase in B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and urinary levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), the latter reflecting the increase in intracellular second-messenger levels resulting from the action of natriuretic peptides, and other direct and indirect, effects of mediators increased by neprilysin inhibition (2). However, the increase in BNP levels after initiation of sacubitril/valsartan was modest in most treated patients (3).

In contrast, A-type natriuretic peptide (ANP), which neprilysin has a greater affinity for compared to BNP, increases more consistently and robustly after sacubitril/valsartan initiation (Online ref. 3,4). It may be that ANP or indeed other neprilysin substrates (e.g. C-type natriuretic peptide, urodilatin, bradykinin, adrenomedullin, substance P, vasoactive intestinal peptide [VIP], calcitonin gene related peptide [CGRP], glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1] and apelin - Figure 1), play a predominant role in the mechanism of action of sacubitril/valsartan and further mechanistic studies are ongoing to elucidate the processes underlying the clinical benefits observed in PARADIGM-HF.

Levels of the N-terminal prohormone of BNP (NT-proBNP), which is not a direct substrate of the neprilysin enzyme, and troponin were significantly lowered by treatment with sacubitril/valsartan reflecting a reduction in cardiac wall stress and cardiac injury, respectively (2). This reduction in NT-proBNP occurred within 4 weeks of therapy in PARADIGM-HF and earlier in other studies. NT-proBNP reduction was strongly and directly related to the observed benefit and represented a near perfect surrogate for benefit in PARADIGM-HF (4). In PARADIGM-HF, treatment with sacubitril/valsartan led to significant reductions in levels of aldosterone, soluble ST2, matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and its specific inhibitor, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1), reflecting a reduction in profibrotic signalling (Online ref 5). Procollagen aminoterminal propeptide type I (PINP) and type III (PIIINP) levels, were also reduced, compared with enalapril, reflecting reduced collagen synthesis. It is uncertain whether neprilysin inhibition has a direct effect on ECM homeostasis or if these profibrotic benefits reflect hemodynamic improvement. The completed PROVE-HF (Prospective Study of Biomarkers, Symptom Improvement, and Ventricular Remodeling During Sacubitril/Valsartan Therapy for Heart Failure; NCT02887183) will continue to examine a broad range of biomarkers, including markers of collagen homeostasis, in 795 patients with HFrEF treated with open-label sacubitril/valsartan (Online ref 6).

Reverse Myocardial Remodeling.

The clinical benefits of ACEi, ARB, β-blockers and cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) are in part, due to a beneficial effects on maladaptive ventricular dilatation and hypertrophy, along with reductions in systolic function, in HFrEF and it has been suggested that neprilysin may reverse this adverse remodeling (Online ref 7). Prior to the publication of PARADIGM-HF, the phase II Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB on Management of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PARAMOUNT) trial in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) demonstrated a significant reduction in left atrial size and volume in patients randomized to sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan after 36 weeks of treatment (Online ref 8).

Pre-clinical acute myocardial infarction and heart failure models have shown improvements in ventricular remodeling with neprilysin inhibition, and non-randomized, observational studies have reported favorable reverse-remodeling in HFrEF patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan (Online ref. 9–11). In patients with HF and significant functional mitral regurgitation, a significant reduction in both the degree of mitral regurgitation and LV end-diastolic volume, as measured by echocardiography, was observed with sacubitril/valsartan, compared with valsartan, in a randomized controlled trial of 118 patients (Online ref. 12). PROVE-HF, a prospective, single-group, open-label study of sacubitril/valsartan in HFrEF, reported a significant 9.4% (95%CI 8.8–9.9, p<0.001) absolute improvement in LV ejection fraction (LVEF) as measured by echocardiography which correlated with changes in NT-proBNP over 12-months of follow-up.(5) Favourable changes in LV volumes and indices of left ventricular filling pressures (left atrial volume and E/e’ ratio) were also reported. In the randomized, double-blind Study of Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan vs. Enalapril on Aortic Stiffness in Patients With Mild to Moderate HF With Reduced Ejection Fraction (EVALUATE-HF), no beneficial effect of sacubitril/valsartan on the primary endpoint of central aortic stiffness or the prespecified secondary endpoint of LVEF was reported compared with enalapril.(6) However, significant favourable changes with sacubitril/valsartan in the prespecified secondary endpoints of LV and left atrial volumes were observed after 12-weeks of follow-up. These data suggest that the beneficial clinical effects of neprilysin inhibition in HFrEF may be, in part, due to a reverse remodelling mechanism of action.

The currently enrolling PARADISE-MI trial includes an echocardiographic substudy and will provide information on the remodeling effect of neprilysin inhibition in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD), HF, or both following an acute myocardial infarction (Supplementary Table 1). Another dedicated randomized, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging-based trial comparing sacubitril/valsartan to valsartan in patients with asymptomatic LVSD and a prior history of myocardial infarction (NCT03552575) will provide further insight into the potential remodeling effects of ARNI.

Clinical Benefits of Sacubitril/Valsartan versus RAS blockade alone

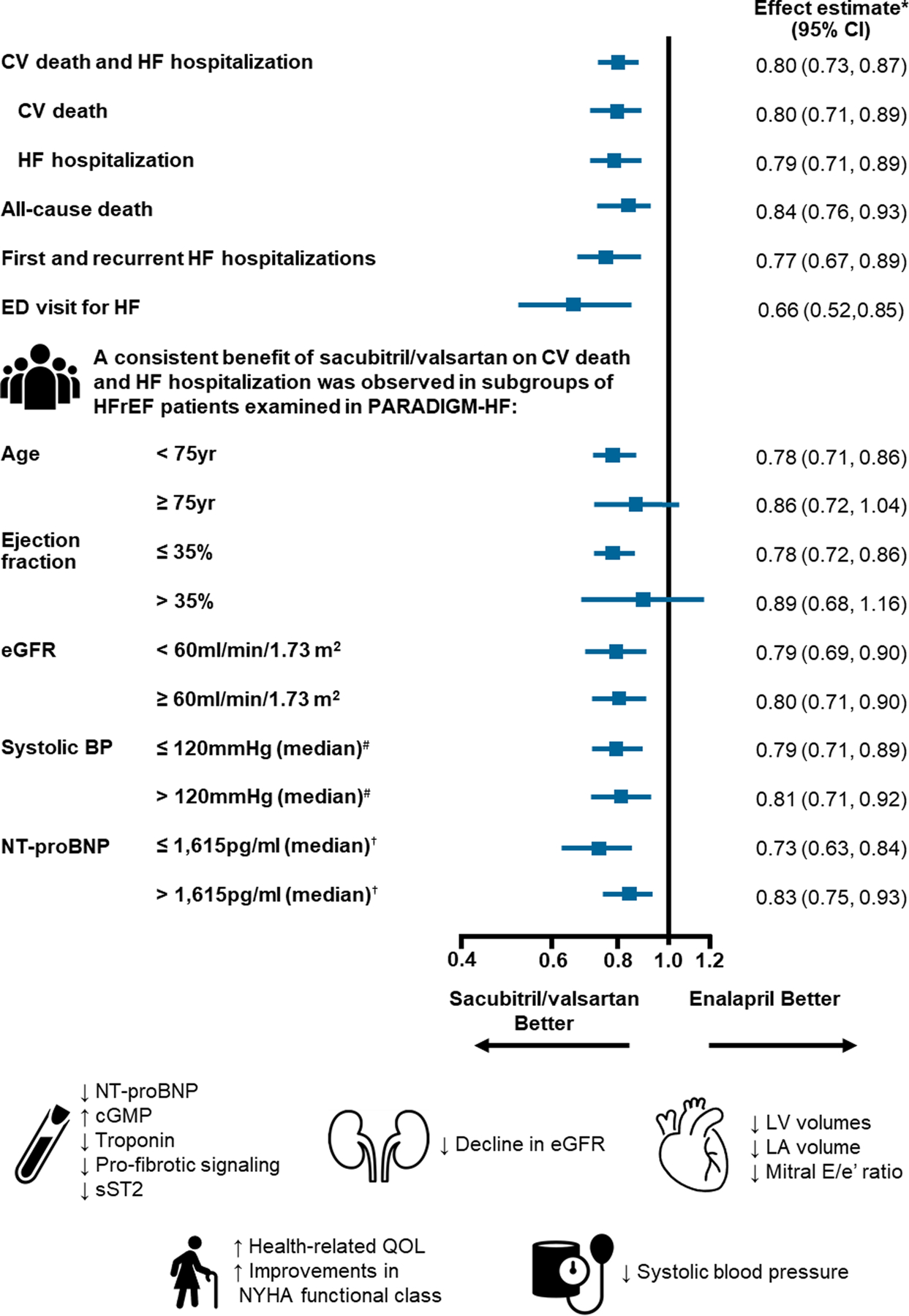

After the publication of the primary results of PARADIGM-HF, a series of subsequent prespecified and post-hoc analyses have provided detailed insight into the clinical and quality-of-life benefits of sacubitril/valsartan over enalapril (Central Illustration).

Central Illustration: Effect of sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril on clinical, mechanistic and quality-of-life outcomes in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction.

*Effect estimate is presented as a hazard ratio except for first and recurrent HF hospitalizations (rate ratio calculated using the negative-binomial method).

# Median systolic blood pressure at randomization = 120mmHg

† Median NT-proBNP at screening = 1,615pg/ml

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; HFrEF, heart failure and reduced ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; BP, blood pressure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal of the prohormone of B-type natriuretic peptide; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; sST2, soluble suppression of tumorigenesis-2; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium; QOL, quality of life; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Estimating Effects of Long-Term Therapy.

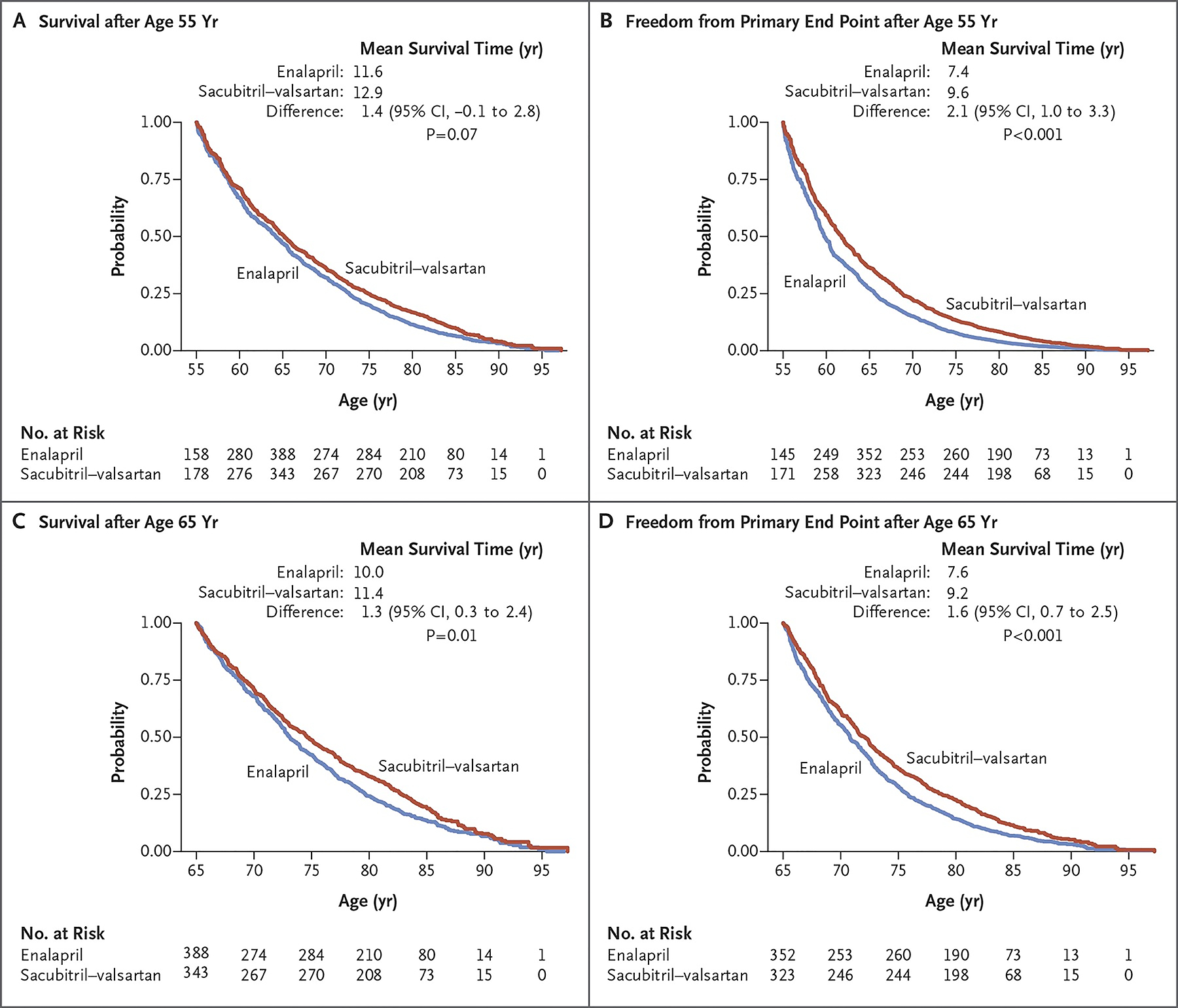

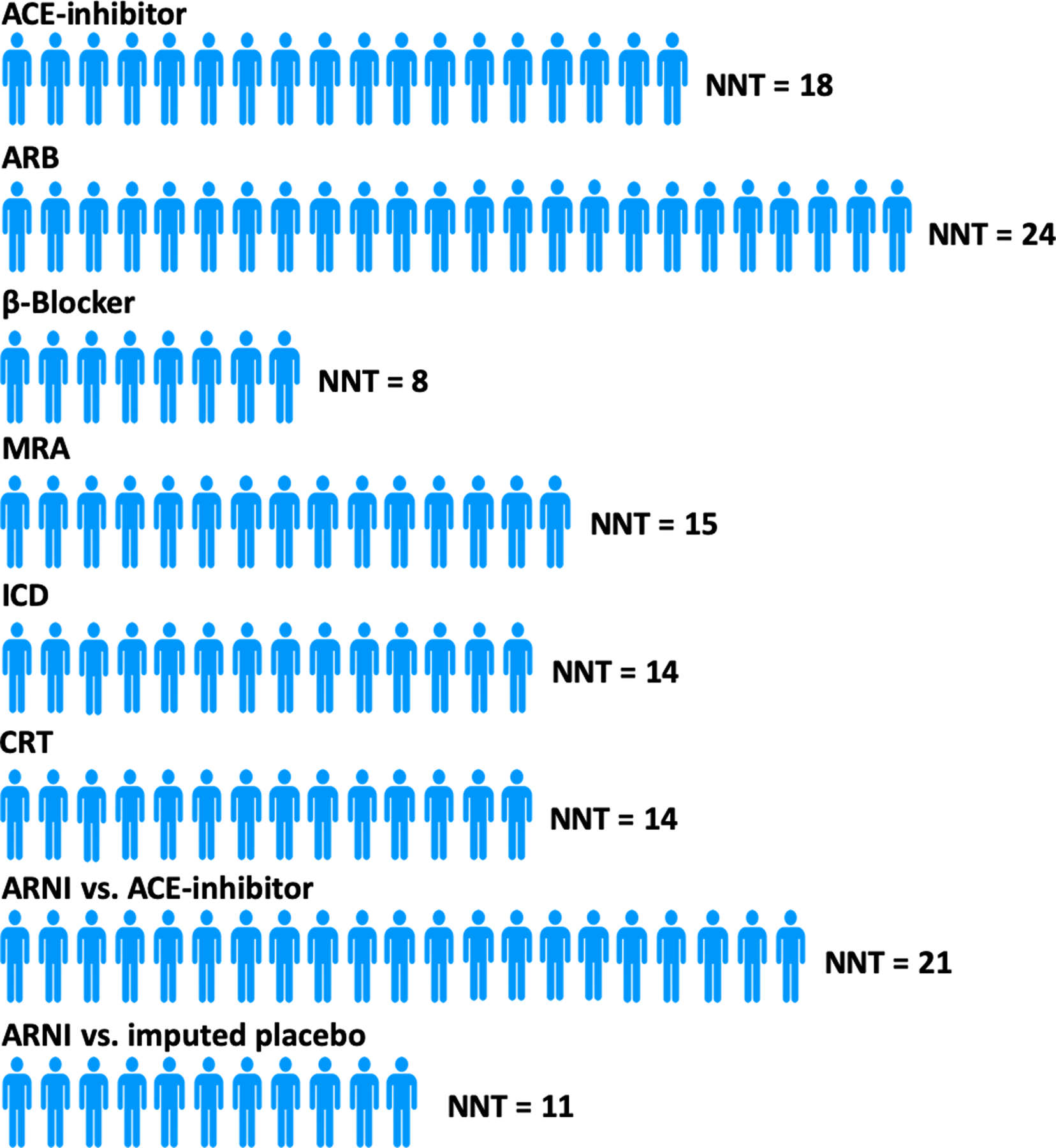

The estimated long-term effects of a treatment are a helpful adjunct to clinical trial results in providing easy-to-understand information to patients regarding the potential benefits of one treatment over another. Leveraging follow-up data from PARADIGM-HF using actuarial methods and assuming consistent long-term benefits patients randomised to sacubitril/valsartan aged 55 and 65 years were estimated have an average survival benefit, compared to enalapril, of 1.4 years (95% confidence interval [CI], −0.1–2.8) and 1.3 years (95% CI, 0.3–2.4), respectively (Figure 2) (7). On a US population level, assuming similar treatment effects and application of the therapy as in PARADIGM-HF, >28,000 deaths may be averted by switching eligible patients with HFrEF from ACEi/ARB to ARNI (Online ref. 13). In PARADIGM-HF the estimated 5-year number needed to treat (NNT) for the primary outcome of cardiovascular mortality or HF hospitalisation was 14 (8) (Figure 3). For all-cause mortality, the NNT was 21 for sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril i.e. adding a neprilysin inhibitor to a RAS blocker, compared with a RAS blocker alone. This compared to NNTs for all-cause mortality of 18 for an ACEi, 8 for a β-blocker, 15 for a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, 14 for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and 14 for cardiac resynchronization therapy for all-cause mortality.

FIGURE 2:

Estimation of extension of life expectancy with sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril based on projections from PARADIGM-HF trial

Figure reproduced from Claggett B. et al. N Engl J Med. 2015(7). Copyright© 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

Figure 3: Estimated 5-year Number Needed to Treat for All-Cause Mortality.

Figure adapted from data from Srivastava PK et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:1226–1231.(8)

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; NNT, number needed to treat; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor.

Reducing Burden of Hospitalizations.

Another goal of treating HFrEF is to reduce the occurrence of often multiple hospitalizations for worsening HF and maximize the time patients spend out of hospital. In PARADIGM-HF, over a median follow-up of 27 months, approximately a third of patients with a first HF hospitalization had at least one further admission. In a recurrent events analysis, compared with enalapril, sacubitril/valsartan reduced both first and recurrent events for both HF hospitalization and the combined endpoint of recurrent HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death (9). The risk of readmission for decompensated HF is highest in the early after discharge and is associated with a high mortality rate. In the US, 30-day readmission rate is a quality-of-care metric which, if higher than expected, may lead to financial penalty. In PARADIGM-HF, the rates of investigator-reported readmission for HF at 30 days were 9.7% and 13.4% in patients randomized to sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril, respectively (odds ratio: 0.62; 95%CI 0.45–0.87; p=0.006) (10). The benefit was also seen at 60 days.

Worsening HF & Clinical Deterioration.

Beyond the improvements in mortality and HF hospitalisation reported in PARADIGM-HF, the addition of a neprilysin inhibitor to a RAS blocker reduces other of non-fatal manifestations of clinical deterioration, including of the need to intensify medical treatment for HF and visits to an emergency department for worsening HF (2). Even among patients hospitalized with worsening HF, sacubitril/valsartan reduced the rate of admission to intensive care (risk reduction [RR]: 18%, p=0.005), the use of intravenous inotropes (RR 31%, p<0.001), and a composite of ventricular assist device implantation, cardiac transplantation and cardiac resynchronization therapy (RR 22%, p=0.07). Investigator-assessed symptomatic limitation, as measured by NYHA functional class, was also improved, with fewer sacubitril/valsartan treated patients deteriorating by ≥1 class, at 8 and 12 months following randomization, compared with enalapril (2).

Adding a neprilysin inhibition to a RAS blocker, compared with a RAS blocker alone, reduced both major modes of CV death among patients with HFrEF, sudden cardiac death and death due to worsening HF (11). The incremental benefit of neprilysin inhibition, compared with RAS inhibition alone, in reducing the risk of CV death, was observed despite high levels of effective medical and device therapy. Among the potential mechanisms underlying this benefit are reduced wall stress, ventricular dilatation, cardiomyocyte injury and hypertrophy, and fibrosis, each of which may reduce the substrate for arrhythmias. The possible vagoexcitatory and sympathoinhibitory actions of natriuretic peptides may also improve electrical stability (Online ref. 14).

Improving Quality of Life.

Compared with enalapril in PARADIGM-HF, sacubitril/valsartan improved health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with HFrEF. Specifically, sacubitril/valsartan reduced symptom burden and physical limitations related to heart failure, as measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), and this benefit extended to nearly all domains of the score when examined individually (1, 12, 13). A significantly smaller proportion of patients randomised to sacubitril/valsartan reported a clinically meaningful deterioration (≥5 points decrease) compared with those randomized to enalapril (27% versus 31%; P=0.01) (12).

Furthermore, compared to individuals randomized to enalapril, patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan reported a significantly attenuated decline in the EQ-5D-3L non-disease specific outcome measure, an evaluation of five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), irrespective of baseline NYHA functional class and this benefit persisted at 36-months follow-up (Online ref 15).

Safety of Sacubitril/Valsartan

Run-In Phases & Tolerability.

In PARADIGM-HF patients were required to tolerate target doses of both enalapril and sacubitril/valsartan during sequential run-in phases, with approximately 10% of participants discontinuing each treatment phase because of intolerance or other reasons. This design element may limit the generalizability of the study findings. Several factors were associated with a higher risk of discontinuation of either enalapril or sacubitril/valsartan during the run-in period, including higher natriuretic peptide levels, lower blood pressure, eGFR <60mL/min/1.73m2, and an ischemic etiology (Online ref 16). An inverse probability-weighted re-analysis of PARADIGM-HF, giving additional weight to those randomized patients with similar characteristics to those who did not complete the run-in, showed a similar benefit of sacubitril/valsartan over enalapril, suggesting that the run-in period and related discontinuations did not alter the interpretation of the results of the trial (Online ref 16).

Renal Function and Potassium.

Renal dysfunction and hyperkalaemia are factors limiting attainment of target doses of RAS antagonists. In PARADIGM-HF, both renal dysfunction (serum creatinine ≥2.5 mg/dl [221 μmol/l]) and severe hyperkalaemia (>6mmol/l) occurred less frequently with sacubitril/valsartan, compared with enalapril (1). Furthermore, the decline in eGFR over time was attenuated with sacubitril/valsartan, compared to enalapril, despite a small increase in urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) with neprilysin inhibition (14). Moreover, patients with CKD at baseline, who were at particularly high risk of adverse outcomes, had a similar relative risk reduction with sacubitril/valsartan, compared with enalapril, and, thus, a large absolute benefit from the addition of a neprilysin inhibitor to RAS blockade.

Combination of an MRA with a RAS blocker increases the risk of hyperkalaemia. Patients on an MRA at baseline in PARADIGM-HF, randomly assigned to enalapril were more likely to experience severe hyperkalaemia than those randomized to sacubitril/valsartan, suggesting that the addition of neprilysin inhibition to dual RAAS blockade may reduce the risk of hyperkalaemia associated with this combination (15).

Hemodynamic Intolerance.

In PARADIGM-HF, symptomatic hypotension occurred more frequently with sacubitril/valsartan group than with enalapril, although this did not lead to a difference in discontinuation between the treatment arms (1). Hypotension was more likely in older patients, those with a lower systolic blood pressure at screening and patients on lower than target dose of ACEi/ARB prior to enrolment (Online ref 17). Importantly, there was no interaction between the occurrence of hypotension, either during the run-in phase or following randomization, and the beneficial treatment effect of sacubitril/valsartan. These results, along with the observation that patients who received sub-target doses of sacubitril/valsartan due to intolerance of higher doses derived similar benefit to those who tolerated higher doses, emphasize that hypotension should not dissuade clinicians from commencing or continuing sacubitril/valsartan at a lower than target dose (16).

In PARADIGM-HF, discontinuation of diuretic was more common in those treated with sacubitril/valsartan, and the number of diuretic dose increases fewer, compared with enalapril (Online ref 18).

Angioedema.

Because only one bradykinin-metabolizing enzyme (neprilysin) is inhibited with sacubitril/valsartan, the risk of angioedema should be low compared with combined ACE and neprilysin inhibitor (e.g. using omapatrilat) (Online ref 19). Angioedema was independently adjudicated in PARADIGM-HF by a blinded committee with a small number of confirmed cases and no major imbalance between treatment arms. Consistent with prior reports that patients of African-descent are at increased risk of treatment-related angioedema, black patients in PARADIGM-HF did experience a higher risk of sacubitril/valsartan-related angioedema compared with non-black patients (Online ref 20).

Amyloid Deposition.

As neprilysin is partially responsible for the clearance of certain amyloid-β peptides from the brain, an ARNI may, theoretically, increase cerebral deposition of these peptides and in the long term, potentially, have an adverse impact on cognition. Two weeks treatment with sacubitril/valsartan, compared with placebo, increased amyloid-β1–38 concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of healthy volunteers, although concentrations of amyloid-β1–40 and the toxic amyloid-β1–42 were unaltered (Online ref. 21). Moreover, rates of dementia-related adverse events in PARADIGM-HF were similar in the sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril treatment arms, and similar to rates observed with other contemporary trials of HFrEF (Online ref 22). A dedicated mini-mental state examination is embedded in the large PARAGON-HF trial (Efficacy and Safety of LCZ696 Compared to Valsartan on Morbidity and Mortality in Heart Failure Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT01920711). Similarly, the PERSPECTIVE trial is comprehensively evaluating the effects of sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan on cognitive function employing a battery of validated neurocognitive instruments and advanced imaging for amyloid deposition in over 550 patients with HFpEF (Supplementary Table 1).

Sacubitril/Valsartan Across the HF Spectrum

In PARADIGM-HF, consistent benefits of sacubitril/valsartan over enalapril were observed across a range of prespecified and other subgroups, including race and geographic region (with patients enrolled in 47 countries on 6 continents) (1, 17). Sacubitril/valsartan was also beneficial across the whole spectrum of age (patients aged between 18 and 96 years were enrolled in PARADIGM-HF) and there was no interaction between age and the risk of any adverse events (18). Moreover, the benefits of the addition of neprilysin inhibition were evident irrespective of the etiology of HFrEF (Online ref 23).

PARADIGM-HF also encompassed patients with a broad spectrum of baseline risk and severity of left ventricular dysfunction. The incremental benefit of ARNI was consistent irrespective of baseline risk as assessed by the MAGGIC (Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure) and EMPHASIS-HF (Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure) risk scores and ejection fraction (Online ref 24, 25). The mean baseline LVEF was 29.5±6.2%. A lower LVEF was associated with a higher risk of all outcomes, with a 5-point reduction in LVEF % associated with a 9% higher risk of the of CV death or HF hospitalization, and each of its components (Online ref 25). The beneficial treatment effect of sacubitril/valsartan was not modified by LVEF (P interaction=0.95 with LVEF modelled as a continuous variable).

The treatment benefits of sacubitril/valsartan were not influenced by the clinical stability of patients at baseline, as determined by the occurrence of, or time from a hospitalization for HF prior to screening(Online ref 26). Overall, 37% of patients in PARADIGM-HF were “clinically stable” at baseline with no history of HF hospitalization prior to randomization. The risk of all endpoints was lower in this subgroup than in less stable patients (those with a history of HF hospitalization), although 20% of “stable” patients had a primary endpoint and 17% died during follow-up. Of those who died, 51% had a cardiovascular death, with no preceding HF hospitalization, and 60% of these deaths occurred suddenly. These data highlight that perceived “stability” is not a reason to withhold the incremental benefits of neprilysin inhibition from patients with HFrEF.

Diabetes mellitus occurs in 30–45% of patients with HFrEF and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality, compared with patients without diabetes. One of the substrates for neprilysin is glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and inhibition of the breakdown of this peptide may result in reduction in blood glucose (Online ref. 27). In PARADIGM-HF, treatment with sacubitril/valsartan resulted in a greater reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) than treatment with enalapril in patients with known diabetes mellitus or an HbA1c ≥6·5% at screening (between-group reduction 0·14%, 95%CI 0·06–0·23, p=0·0055) (Online ref 28). Furthermore, there was less initiation of insulin or oral glucose lowering medications in patients randomized to sacubitril/valsartan, compared with enalapril. Additionally, the reduction in decline of eGFR over time, which was more marked in patients with diabetes, than in those without, was attenuated with sacubitril/valsartan (to at least as great an extent as in individuals without diabetes) (p for interaction=0·038) (Online ref 29).

Practical Considerations with Sacubitril/Valsartan

Patient Selection:

Ambulatory or hospitalized patients with HFrEF and a systolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg are potential candidates for sacubitril/valsartan. The safety and efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan among patients with advanced HFrEF (defined as patients with NYHA class IV symptoms, an LVEF ≤35%, elevated natriuretic peptide levels, established on evidenced based HFrEF therapy for at least 3 months [or intolerant of this] and at least one of the following criteria: current or recent use of inotropes; a HF hospitalization in the past 6 months; LVEF ≤25%; or reduced functional capacity measured by either peak VO2 or 6-minute walk test) is being studied in the HFN-LIFE trial (Supplementary Table 1). Although the US & European guidelines differ regarding need for optimization of background medical therapies (namely β-blockers and MRAs), the efficacy of ARNI appears consistent irrespective of background therapy (Online ref 30). Implementation of multi-drug regimens of therapies known to alter disease course and mortality in HFrEF (ARNI, β-blockers, MRAs, and most recently the sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin) is expected to afford substantial extension of life expectancy and survival free from heart failure events.(19)

In-Hospital Initiation:

Although most patients in PARADIGM-HF were in NYHA functional class II, the analyses described above showed many of these patients were at high risk and far from “stable”. The efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan was consistent across risk strata and similar whether patients were recently hospitalized or not (20). Patients in hospital because of decompensated HF face the highest risks of near-term readmission and mortality, and thus potentially stand most to benefit from therapeutic optimization. While these patients were excluded from evaluation in PARADIGM-HF, in PIONEER-HF (Comparison of Sacubitril–Valsartan versus Enalapril on Effect on NT-proBNP in Patients Stabilized from an Acute Heart Failure Episode), the safety and efficacy of in-hospital initiation of sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril were compared in 881 patients stabilized after admission with decompensated HFrEF. NT-proBNP level (the primary endpoint) was reduced more by sacubitril/valsartan compared to enalapril, from baseline through weeks 4 and 8 after discharge, while the rates of key safety outcomes (worsening renal function, hyperkalemia, symptomatic hypotension, and angioedema) were not different between treatment groups (21). Although PIONEER-HF was not powered to assess clinical endpoints, in-hospital initiation of sacubitril/valsartan reduced the composite outcome of death, rehospitalization for HF, implantation of a left ventricular assist system, or listing for cardiac transplantation by 46%, compared with enalapril. This benefit was due, principally, to an observed reduction in HF rehospitalization. A post-hoc, exploratory analysis reported a 42% (95%CI 13–61%; p=0.007) reduction in clinical endpoint committee-adjudicated CV death or HF hospitalization with sacubitril/valsartan compared to enalapril (Online ref 31). A reduction in adjudicated HF hospitalization was evident as early as 30 days following randomisation (HR 0.72; 95% CI,0.42–1.25) with a 39% (95%CI 7–60%; p=0.021) reduction at 8 weeks. In patients who were randomised to sacubitril/valsartan, increased natriuretic peptide bioactivity was evidenced by significant increases in urinary cGMP levels at 1 week following randomisation (Online ref 32). Early, favourable changes in levels of biomarkers of both haemodynamic stress (NT-proBNP and soluble ST2) and myocardial injury (high-sensitivity troponin T) were also observed in patients randomised to sacubitril/valsartan compared to enalapril.

The results of PIONEER-HF demonstrate that in hospitalized patients stabilised from an acute decompensation of HFrEF, the addition of a neprilysin inhibitor to a RAS antagonist and standard therapy is safe and effective compared to standard therapy alone. Furthermore, it provides evidence of benefit in groups of patients who were not enrolled in PARADIGM-HF; at randomisation around a half of patients were RAS antagonist naïve and a third of patients were de-novo presentations of HF. A strategy of in-hospital initiation may promote persistence with treatment after discharge and help overcome “therapeutic inertia” in the care of ambulatory patients mistakenly considered to be “stable”. The open-label TRANSITION trial initiation sacubitril/valsartan initiated before discharge compared to 1–14 days after hospital discharge, among 1,002 patients stabilized after hospitalization for HFrEF. Similar proportions of patients in each group achieved pre-defined target doses of the therapy by 10 weeks after randomization (Online ref 33).

Data-Driven Approach to Clinical Use of Sacubitril/Valsartan:

To minimize risks of angioedema, a washout period of at least 36 hours after the last dose of ACEi should be allowed prior to initiation of sacubitril/valsartan (this is not necessary if the patient has been taking an ARB). Sacubitril/valsartan is an oral therapy dosed twice daily with 3 doses available in most countries: 24/26mg, 49/51mg, and 97/103mg (target dose); in some countries these doses are described as 50, 100 and 200mg. Prior dosing and tolerance of an ACEi/ARB helps guide selection of the appropriate starting dose of ARNI. Based on the American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus Decision Pathway, patients should be started on the 49/51mg dose if tolerating the equivalent of enalapril 10mg twice daily or valsartan 160mg twice daily. Patients who are RAS-blocker naïve, tolerating less than this dose, or who severe renal dysfunction or moderate hepatic dysfunction should start with the 24/26mg dose (Online ref 34).

TITRATION assessed strategies for up-titrating and optimizing the dose of sacubitril/valsartan and 498 patients were randomized to a “condensed” regimen (49/51 mg twice daily for 2 weeks followed by 97/103 mg twice daily for 10 weeks) or a “conservative” regimen (24/26 mg twice daily for 2 weeks, 49/51 mg twice daily for 3 weeks, followed by 97/103 mg twice daily for 7 weeks) (Online ref 35). Rates of hypotension, renal dysfunction, and hyperkalemia at 12 weeks were similar in the two treatment groups. Overall, attainment of the target dose of 97/103 mg twice daily was similar between arms and three-quarters of patients were successfully maintained on this dose. However, among patients on lower pre-initiation doses of ACEi/ARB, the conservative uptitration regimen resulted in greater attainment of target dosing compared with the condensed regimen (Online ref 35). In clinical practice, dose increases towards the target dose of 97/103mg may be made every 2–4 weeks, depending on tolerability assessed by symptoms of hypotension, blood pressure, renal function, and potassium. Sacubitril/valsartan seems to be “diuretic-sparing” and loop diuretic dose may be need to be reduced during or after uptitration (Online ref 18). Indeed, in euvolemic patients, consideration should be given to reducing diuretic dose before initiating or switching to sacubitril/valsartan; similarly, stopping other treatments with a blood pressure lowering effect that have not been demonstrated to improve clinical outcomes in HFrEF (e.g. nitrates, calcium channel blockers, and alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists) may facilitate the introduction of sacubitril/valsartan.

Conclusions

Sacubitril/valsartan is an efficacious, safe, and cost-effective therapy that improves quality of life and longevity in patients with chronic HFrEF, as well as reducing hospital admission. An in-hospital initiation strategy offers a potentially new avenue to improve the clinical uptake of sacubitril/valsartan.

The recently completed PARAGON-HF trial showed that sacubitril/valsartan modestly reduced the risks of total heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular death compared with valsartan, although this finding narrowly missed statistical significance.(22) Clinical benefits were observed in secondary endpoints including quality of life and kidney endpoints; women and patients at the lower end of the LVEF spectrum appeared to preferentially benefit. The safety profile of sacubitril/valsartan was largely consistent with prior trial experiences. Regulatory review of sacubitril/valsartan for the indication of treatment of HFpEF is currently underway. Ongoing trials are evaluating the clinical utility of sacubitril/valsartan among patients with HFpEF (PARALLAX) and acute MI (PARADISE-MI) (Supplementary Table 1).

In the last 5 years sacubitril/valsartan has been established as a cornerstone component of comprehensive disease-modifying medical therapy in the management of chronic HFrEF; the next 5 years should see its wider implementation in practice and potential expansion of its therapeutic indications.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

In PARADIGM-HF, sacubitril/valsartan reduced morbidity and mortality compared to enalapril in patients with chronic HFrEF.

A series of subsequent analyses of PARADIGM-HF have provided further insight into the benefits of sacubitril/valsartan over enalapril.

Subsequent smaller mechanistic trials have highlighted the favorable effects of sacubitril/valsartan in attenuating adverse myocardial remodeling.

Other trials have advanced potential pathways for therapeutic implementation (including during hospitalization for heart failure).

Ongoing trials may provide evidence of new indications for sacubitril/valsartan.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Vaduganathan is supported by the KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH/NCATS Award UL 1TR002541), and serves on advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, and Relypsa. Dr. Solomon has received research grants from Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bellerophon, Celladon, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Ionis Pharmaceutics, Lone Star Heart, Mesoblast, MyoKardia, NIH/NHLBI, Novartis, Sanofi Pasteur, Theracos, and has consulted for Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corvia, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Ironwood, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, and Theracos. Professor McMurray’s employer, Glasgow University, has been paid by Novartis (who manufacture sacubitril/valsartan) for his time spent as committee member for the trials listed (using sacubitril/valsartan), meetings related to these trials and other activities related to sacubitril/valsartan e.g. lectures, advisory boards and other meetings. Novartis has also paid his travel and accommodation for some of these meetings. These payments were made through a Consultancy with Glasgow University and he has not received personal payments in relation to these trials/this drug. The trials include - PARADIGM-HF: co-PI; PARAGON-HF: co-PI; PERSPECTIVE, PARADISE-MI and UK HARP III Trial: executive/steering committees. Professor McMurray and Dr. Docherty are conducting an investigator originated study funded by the British Heart Foundation (Project Grant no. PG/17/23/32850) using sacubitril/valsartan supplied by Novartis.

ABBREVIATIONS LIST

- ACEi

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARB

angiotensin II receptor blockers

- ARNI

angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

References

- 1.McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition versus Enalapril in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer M, McMurray JJV, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibition Compared With Enalapril on the Risk of Clinical Progression in Surviving Patients With Heart Failure. Circulation 2015;131:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myhre PL, Vaduganathan M, Claggett B, et al. B-Type Natriuretic Peptide During Treatment With Sacubitril/Valsartan: The PARADIGM-HF Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2019;73:1264–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zile MR, Claggett BL, Prescott MF, et al. Prognostic Implications of Changes in N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in Patients With Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2016;68:2425–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Januzzi JL, Prescott MF, Butler J, et al. Association of change in n-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide following initiation of sacubitril-valsartan treatment with cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA 2019;322:1085–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai AS, Solomon SD, Shah AM, et al. Effect of Sacubitril-Valsartan vs Enalapril on Aortic Stiffness in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA 2019;322:1077–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claggett B, Packer M, McMurray JJV, et al. Estimating the Long-Term Treatment Benefits of Sacubitril–Valsartan. N. Engl. J. Med 2015;373:2289–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava PK, Claggett BL, Solomon SD, et al. Estimated 5-Year Number Needed to Treat to Prevent Cardiovascular Death or Heart Failure Hospitalization with Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition vs Standard Therapy for Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:1226–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mogensen UM, Gong J, Jhund PS, et al. Effect of sacubitril/valsartan on recurrent events in the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM-HF). Eur. J. Heart Fail 2018;20:760–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai AS, Claggett BL, Packer M, et al. Influence of Sacubitril/Valsartan (LCZ696) on 30-Day Readmission After Heart Failure Hospitalization. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2016;68:241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai AS, McMurray JJ V, Packer M, et al. Effect of the angiotensin-receptor-neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 compared with enalapril on mode of death in heart failure patients. Eur. Heart J 2015;36:1990–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis EF, Claggett BL, McMurray JJ V., et al. Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes in PARADIGM-HF. Circ. Heart Fail 2017;10:e003430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandra A, Lewis EF, Claggett BL, et al. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on physical and social activity limitations in patients with heart failure, A secondary analysis of the PARADIGM-HF trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damman K, Gori M, Claggett B, et al. Renal Effects and Associated Outcomes During Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure. JACC Hear. Fail 2018;6:489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai AS, Vardeny O, Claggett B, et al. Reduced Risk of Hyperkalemia During Treatment of Heart Failure With Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists by Use of Sacubitril/Valsartan Compared With Enalapril. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vardeny O, Claggett B, Packer M, et al. Efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril at lower than target doses in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the PARADIGM-HF trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2016;18:1228–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristensen SL, Martinez F, Jhund PS, et al. Geographic variations in the PARADIGM-HF heart failure trial. Eur. Heart J 2016;37:3167–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jhund PS, Fu M, Bayram E, et al. Efficacy and safety of LCZ696 (sacubitril-valsartan) according to age: Insights from PARADIGM-HF. Eur. Heart J 2015;36:2576–2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Jhund PS, et al. Estimating lifetime benefits of comprehensive disease-modifying pharmacological therapies in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a comparative analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2020; S0140–6736(20)30748–0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon SD, Claggett B, Packer M, et al. Efficacy of Sacubitril/Valsartan Relative to a Prior Decompensation: The PARADIGM-HF Trial. JACC. Heart Fail 2016;4:816–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, et al. Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med 2019;380:539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, et al. Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med 2019;381:1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Online References

- 1.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J 2016;37:2129–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2017;70:776–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nougué H, Pezel T, Picard F, et al. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on neprilysin targets and the metabolism of natriuretic peptides in chronic heart failure: a mechanistic clinical study. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2018;21:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim NE, McCarthy CP, Shrestha S, et al. Effect of Neprilysin Inhibition on Various Natriuretic Peptide Assays. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2019;73:1273–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zile MR, O’Meara E, Claggett B, et al. Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan on Biomarkers of Extracellular Matrix Regulation in Patients With HFrEF. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2019;73:795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Januzzi JL, Butler J, Fombu E, et al. Rationale and methods of the Prospective Study of Biomarkers, Symptom Improvement, and Ventricular Remodeling During Sacubitril/Valsartan Therapy for Heart Failure (PROVE-HF). Am. Heart J 2018;199:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konstam MA, Kramer DG, Patel AR, Maron MS, Udelson JE. Left ventricular remodeling in heart failure: current concepts in clinical significance and assessment. JACC. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2011;4:98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon SD, Zile M, Pieske B, et al. The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a phase 2 double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:1387–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Lueder TG, Wang BH, Kompa AR, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 attenuates cardiac remodeling and dysfunction after myocardial infarction by reducing cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy. Circ. Hear. Fail 2015;8:71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kompa AR, Lu J, Weller TJ, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition provides superior cardioprotection compared to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition after experimental myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol 2018;258:192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martens P, Beliën H, Dupont M, Vandervoort P, Mullens W. The reverse remodeling response to sacubitril/valsartan therapy in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Cardiovasc. Ther 2018;36:e12435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang D-H, Park S-J, Shin S-H, et al. Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitor for Functional Mitral Regurgitation. Circulation 2019;139:1354–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonarow GC, Yancy CW, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Spertus JA, Heidenreich PA. Potential impact of optimal implementation of evidence-based heart failure therapies on mortality. Am. Heart J 2011;161:1024–1030.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang CC, Struthers AD. Interactions between atrial natriuretic factor and the autonomic nervous system. Clin. Auton. Res 1991;1:329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trueman D, Kapetanakis V, Briggs A, et al. P3373 Better health-related quality of life in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril, irrespective of NYHA class: Analysis of EQ-5D in PARADIGM-HF. Eur. Heart J 2017;38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai AS, Solomon S, Claggett B, et al. Factors Associated With Noncompletion During the Run-In Period Before Randomization and Influence on the Estimated Benefit of LCZ696 in the PARADIGM-HF Trial. Circ. Hear. Fail 2016;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardeny O, Claggett B, Kachadourian J, et al. Incidence, Predictors, and Outcomes Associated With Hypotensive Episodes Among Heart Failure Patients Receiving Sacubitril/Valsartan or Enalapril. Circ. Hear. Fail 2018;11:e004745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vardeny O, Claggett B, Kachadourian J, et al. Reduced loop diuretic use in patients taking sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril: the PARADIGM-HF trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2019;21(3):337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostis JB, Packer M, Black HR, Schmieder R, Henry D, Levy E. Omapatrilat and enalapril in patients with hypertension: The Omapatrilat Cardiovascular Treatment vs. Enalapril (OCTAVE) trial. Am. J. Hypertens 2004;17:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi V, Senni M, Streefkerk H, Modgill V, Zhou W, Kaplan A. Angioedema in heart failure patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) or enalapril in the PARADIGM-HF study. Int. J. Cardiol 2018;264:118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hubers SA, Brown NJ. Combined angiotensin receptor antagonism and neprilysin inhibition. Circulation 2016;133:1115–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannon JA, Shen L, Jhund PS, et al. Dementia-related adverse events in PARADIGM-HF and other trials in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2017;19:129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balmforth C, Simpson J, Shen L, et al. Outcomes and Effect of Treatment According to Etiology in HFrEF. JACC Hear. Fail 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson J, Jhund PS, Silva Cardoso J, et al. Comparing LCZ696 with Enalapril According to Baseline Risk Using the MAGGIC and EMPHASIS-HF Risk Scores An Analysis of Mortality and Morbidity in PARADIGM-HF. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2015;66:2059–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon SD, Claggett B, Desai AS, et al. Influence of Ejection Fraction on Outcomes and Efficacy of Sacubitril/Valsartan (LCZ696) in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: The Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF). Circ. Hear. Fail 2016;9:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon SD, Claggett B, Packer M, et al. Efficacy of Sacubitril/Valsartan Relative to a Prior Decompensation: The PARADIGM-HF Trial. JACC. Heart Fail 2016;4:816–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willard JR, Barrow BM, Zraika S. Improved glycaemia in high-fat-fed neprilysin-deficient mice is associated with reduced DPP-4 activity and increased active GLP-1 levels. Diabetologia 2017;60:701–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seferovic JP, Claggett B, Seidelmann SB, et al. Effect of sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril on glycaemic control in patients with heart failure and diabetes: a post-hoc analysis from the PARADIGM-HF trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Packer M, Claggett B, Lefkowitz MP, et al. Effect of neprilysin inhibition on renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic heart failure who are receiving target doses of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system: a secondary analysis of the PARADIGM-HF trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okumura N, Jhund PS, Gong J, et al. Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan in the PARADIGM-HF Trial (Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) According to Background Therapy. Circ. Heart Fail 2016;9(9):e003212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrow DA, Velazquez EJ, DeVore AD, et al. Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Randomly Assigned to Sacubitril/Valsartan or Enalapril in the PIONEER-HF Trial. Circulation 2019:139(19):2285–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrow DA, Velazquez EJ, DeVore AD, et al. Cardiovascular biomarkers in patients with acute decompensated heart failure randomized to sacubitril-valsartan or enalapril in the PIONEER-HF trial. Eur Heart J 2019;40(40):3345–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wachter R, Senni M, Belohlavek J, Butylin D, Noe A, Pascual-Figal D. Sacubitril/Valsartan Initiated in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction after Hemodynamic Stabilization: Primary Results of the TRANSITION Study. J. Card. Fail 2018;24:S15. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yancy CW, Januzzi JL, Allen LA, et al. 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Optimization of Heart Failure Treatment: Answers to 10 Pivotal Issues About Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2018;71:201–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senni M, McMurray JJ V, Wachter R, et al. Initiating sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) in heart failure: results of TITRATION, a double-blind, randomized comparison of two uptitration regimens. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2016;18:1193–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.