Abstract

Background

Hip fractures are a major healthcare problem, presenting a huge challenge and burden to individuals and healthcare systems. The number of hip fractures globally is rising rapidly. The majority of hip fractures are treated surgically. This review evaluates evidence for types of arthroplasty: hemiarthroplasties (HAs), which replace part of the hip joint; and total hip arthroplasties (THAs), which replace all of it.

Objectives

To determine the effects of different designs, articulations, and fixation techniques of arthroplasties for treating hip fractures in adults.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, seven other databases and one trials register in July 2020.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs comparing different arthroplasties for treating fragility intracapsular hip fractures in older adults. We included THAs and HAs inserted with or without cement, and comparisons between different articulations, sizes, and types of prostheses. We excluded studies of people with specific pathologies other than osteoporosis and with hip fractures resulting from high‐energy trauma.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We collected data for seven outcomes: activities of daily living, functional status, health‐related quality of life, mobility (all early: within four months of surgery), early mortality and at 12 months after surgery, delirium, and unplanned return to theatre at the end of follow‐up.

Main results

We included 58 studies (50 RCTs, 8 quasi‐RCTs) with 10,654 participants with 10,662 fractures. All studies reported intracapsular fractures, except one study of extracapsular fractures. The mean age of participants in the studies ranged from 63 years to 87 years, and 71% were women.

We report here the findings of three comparisons that represent the most substantial body of evidence in the review. Other comparisons were also reported, but with many fewer participants.

All studies had unclear risks of bias in at least one domain and were at high risk of detection bias. We downgraded the certainty of many outcomes for imprecision, and for risks of bias where sensitivity analysis indicated that bias sometimes influenced the size or direction of the effect estimate.

HA: cemented versus uncemented (17 studies, 3644 participants)

There was moderate‐certainty evidence of a benefit with cemented HA consistent with clinically small to large differences in health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.20, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.34; 3 studies, 1122 participants), and reduction in the risk of mortality at 12 months (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.96; 15 studies, 3727 participants). We found moderate‐certainty evidence of little or no difference in performance of activities of daily living (ADL) (SMD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.21 to 0.16; 4 studies, 1275 participants), and independent mobility (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.14; 3 studies, 980 participants). We found low‐certainty evidence of little or no difference in delirium (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.55 to 2.06; 2 studies, 800 participants), early mortality (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.13; 12 studies, 3136 participants) or unplanned return to theatre (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.10; 6 studies, 2336 participants). For functional status, there was very low‐certainty evidence showing no clinically important differences.

The risks of most adverse events were similar. However, cemented HAs led to less periprosthetic fractures intraoperatively (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.46; 7 studies, 1669 participants) and postoperatively (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.57; 6 studies, 2819 participants), but had a higher risk of pulmonary embolus (RR 3.56, 95% CI 1.26 to 10.11, 6 studies, 2499 participants).

Bipolar HA versus unipolar HA (13 studies, 1499 participants)

We found low‐certainty evidence of little or no difference between bipolar and unipolar HAs in early mortality (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.64; 4 studies, 573 participants) and 12‐month mortality (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.53; 8 studies, 839 participants). We are unsure of the effect for delirium, HRQoL, and unplanned return to theatre, which all indicated little or no difference between articulation, because the certainty of the evidence was very low. No studies reported on early ADL, functional status and mobility.

The overall risk of adverse events was similar. The absolute risk of dislocation was low (approximately 1.6%) and there was no evidence of any difference between treatments.

THA versus HA (17 studies, 3232 participants)

The difference in the risk of mortality at 12 months was consistent with clinically relevant benefits and harms (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.22; 11 studies, 2667 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). There was no evidence of a difference in unplanned return to theatre, but this effect estimate includes clinically relevant benefits of THA (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.07, favours THA; 10 studies, 2594 participants; low‐certainty evidence). We found low‐certainty evidence of little or no difference between THA and HA in delirium (RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.60 to 3.33; 2 studies, 357 participants), and mobility (MD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.96 to 0.16, favours THA; 1 study, 83 participants). We are unsure of the effect for early functional status, ADL, HRQoL, and mortality, which indicated little or no difference between interventions, because the certainty of the evidence was very low.

The overall risks of adverse events were similar. There was an increased risk of dislocation with THA (RR 1.96, 95% CI 1.17 to 3.27; 12 studies, 2719 participants) and no evidence of a difference in deep infection.

Authors' conclusions

For people undergoing HA for intracapsular hip fracture, it is likely that a cemented prosthesis will yield an improved global outcome, particularly in terms of HRQoL and mortality. There is no evidence to suggest a bipolar HA is superior to a unipolar prosthesis. Any benefit of THA compared with hemiarthroplasty is likely to be small and not clinically appreciable. We encourage researchers to focus on alternative implants in current clinical practice, such as dual‐mobility bearings, for which there is limited available evidence.

Plain language summary

Hip replacement surgery in adults

This review assessed evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs, on the benefits and harms of different types of hip replacement used to treat hip fracture in adults.

Background

A hip fracture is a break at the top of the leg bone. These types of breaks are common in older adults whose bones may be fragile because of a condition called osteoporosis. One method of treatment is to replace the broken hip with an artifical one. This can be done using a hemiarthroplasty (HA), which replaces part of the hip joint (the ball part of the joint). These replacements can be unipolar (a single artificial joint), or bipolar (with an additional joint within the HA). Alternatively, surgery may replace the whole hip joint, which also includes the socket in which the ball of the hip joint sits ‐ this a total hip arthroplasty (THA). Both of these artificial joints can be fixed in place with or without bone cement.

Search date

We searched for RCTs (clinical studies where people are randomly assigned to treatment groups), and quasi‐RCTs (in which people are put into groups by a method which is not randomised, such as date of birth or hospital record number) up to 6 July 2020.

Study characteristics

We included 58 studies, involving 10,654 adults with 10,662 hip fractures. Study participants ranged from 63 to 87 years of age, and 71% were women, which is usual for people who have this type of hip fracture.

Key results

Cemented HAs compared to uncemented HAs (17 studies, 3644 participants)

We found that cemented HAs improve health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and reduce the risk of death at 12 months after surgery. The sizes of these benefits ranged from a small to a large effect. There may be little or no difference between treatments in the ability to use the hip (functional status), but this evidence was very uncertain. Whether or not the HA is cemented probably makes little or no difference to performance in activities of daily living (ADL) or the ability to walk independently, how many people experience confusion after surgery (delirium), die within four months of surgery, or need additional surgery. Most complication risks were similar, but we noted that some risks related directly to hip replacement surgery (such as causing a break during surgery) were increased with uncemented HAs.

Bipolar HAs compared to unipolar HAs (13 studies, 1499 participants)

The type of HA probably makes little or no difference to how many people die within four months or up to 12 months after surgery, and may make little or no difference to the need for additional surgery. No studies reported four‐month ADL and functional status. The evidence was very uncertain whether using a bipolar or unipolar HA makes any difference to delirium or HRQoL within four months of surgery. Again, complication risks were similar, and we found no evidence of a difference in the risk of hip dislocation.

THAs compared to HAs (17 studies, 3232 participants)

We are uncertain whether ADL, functional status, delirium, mobility, or deaths within four months or up to 12 months after surgery are different between these treatments. The evidence did not show a difference in the risk of additional surgery but we could not exclude the possibility of an important benefit of THA. Although the risk of most complications was similar, hip dislocation is increased with THA.

Certainty of the evidence

The evidence for many of the comparisons is based on only a few participants, and many studies used methods which may not be reliable. Most of the evidence for ADL, functional status, HRQoL, and independent walking was of low and very low certainty, meaning that we are not confident in the findings. We had limited confidence or were moderately confident in our other findings.

Conclusions

For people having a HA, it is likely that a cemented replacement produces a better outcome overall than an uncemented replacement. There is no evidence to suggest that a bipolar HA leads to different outcomes from a unipolar HA. The differences between a total hip replacement and partial hip replacement are small and may not be clinically important.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Epidemiology

A hip fracture, or proximal femoral fracture, is a break in the upper region of the femur (thigh bone) between the subcapital region (the area just under the femoral head) and 5 cm below the lesser trochanter (a bony projection of the upper femur). The incidence of hip fractures increases with age, and are most common in the older adult population (Court‐Brown 2017; Kanis 2001). Hip fractures in younger adults are usually associated with poor bone health (Karantana 2011; Rogmark 2018). A small proportion of fractures occurring in younger people are a result of high‐energy trauma, such as road traffic collisions and sports injuries. Most hip fractures are fragility fractures associated with osteoporosis, and resulting from mechanical forces that would not ordinarily result in fracture. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined fragility fracture as those sustained from injuries equivalent to a fall from a standing height or less (Kanis 2001). In the UK, the mean age of a person with hip fracture is 83 years and approximately two‐thirds occur in women (NHFD 2017).

Hip fractures are a major healthcare problem at the individual and population level, and present a huge challenge and burden to individuals, healthcare systems, and societies. The increased proportion of older adults in the world population means that the absolute number of hip fractures is rising rapidly worldwide. For example, in 2016 there were 65,645 new presentations of hip fracture to 177 trauma units in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland (NHFD 2017). Based on mid‐2016 population estimates for these regions, this equates to an incidence rate of 108 cases per 100,000 population (ONS 2018). By 2050, the annual worldwide incidence is estimated to be 6 million hip fractures (Cooper 2011; Johnell 2004). Incident hip fracture rates are higher in high‐income countries compared to low‐ or middle‐income countries. The highest hip fracture rates are seen across northern Europe and the USA, and the lowest in Latin America and Africa (Dhanwal 2011). There is also a north‐south gradient seen in European studies, and similarly, more fractures are seen in the north of the USA than in the south (Dhanwal 2011). The factors responsible for the variation in the incidence of hip fractures and osteoporosis are thought to be population demographics (with more elderly populations in countries with higher incidence rates), and the influence of ethnicity, latitude, and environmental factors such as socioeconomic deprivation (Bardsley 2013; Cooper 2011; Dhanwal 2011; Kanis 2012).

Burden of disease

Hip fractures are also associated with a high risk of death. For example, in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the 30‐day mortality rate in 2016 remained high at 6.7%, despite a decline from 8.5% in 2011 and 7.1% in 2015 (NHFD 2017). Mortality at one year following a hip fracture is approximately 30%. However, fewer than half of deaths are attributable to the fracture itself, reflecting the frailty of the individuals and associated high prevalence of comorbidities and complications (Parker 1991; SIGN 2009). Morbidity associated with hip fractures is similar to stroke in terms of impact, with a substantial loss of healthy life‐years in older people (Griffin 2015). As such, hip fractures commonly result in reduced mobility and greater dependency, with many people failing to return to their pre‐injury residence. In addition, the public health impact of hip fractures is significant: data from large prospective cohorts show the burden of disease due to hip fracture is 27 disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) per 1000 individuals, which equates to an average loss of 2.7% of the healthy life expectancy in this population at risk of fragility hip fracture (Papadimitriou 2017).

The direct economic burden of hip fractures is also substantial. Hip fractures are among the most expensive conditions seen in hospitals, with an aggregated cost of nearly 4900 million US dollars (USD) for 316,000 inpatient episodes in the USA in 2011 (Torio 2013). In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, people with hip fracture occupy 1.5 million hospital bed days each year, and cost the National Health Service (NHS) and social care 1000 million pounds sterling (GBP) (NHFD 2017). Combined health and social care costs incurred during the first year following a hip fracture have been estimated at USD 43,669, which is greater than the cost for non‐communicable diseases, such as acute coronary syndrome (USD 32,345) and ischaemic stroke (USD 34,772) (Williamson 2017). In established market economies, hip fractures represent 1.4% of the total healthcare burden (Johnell 2004).

Types of hip fracture

Hip fractures either involve the region of the femur that is enveloped by the ligamentous hip joint capsule (intracapsular), or that is outside the capsule (extracapsular).

Intracapsular fractures include subcapital (immediately below the femoral head), transcervical (across the mid‐femoral neck), or basicervical (across the base of the femoral neck). These injuries are also commonly termed fractures of the ‘neck of femur' (Lloyd‐Jones 2015). Intracapsular fractures can be further subdivided by fracture morphology using several different classification systems, such as the Garden (Garden 1961) or Pauwels classifications (Pauwels 1935). The reliability of these various classifications is poor (Parker 1993a; Parker 1998). A more appropriate grouping distinguishes only those fractures that are displaced, where the anatomy of the bone has been disrupted at the fracture site, and those that are undisplaced (Blundell 1998; Parker 1999). This system broadly corresponds with prognosis: the more displaced, the more likely the blood supply to the femoral head is compromised, which can lead to complications such as avascular necrosis and collapse of the femoral head. More recently, this classification has been refined with additional consideration of posterior tilt ‐ this is not a component of earlier classification, but may be useful in predicting poor outcomes from osteosynthesis (Palm 2009). Furthermore, displaced fractures are less stable, so that treatments involving fixation have a higher risk of failure compared with undisplaced fractures. Approximately 60% of hip fractures are intracapsular; of these, approximately 70% to 90% are displaced (Keating 2010; NHFD 2017).

Extracapsular fractures traverse the femur within the area of bone bounded by the intertrochanteric line proximally up to a distance of 5 cm from the distal part of the lesser trochanter. Several classification methods have been proposed to define different types of extracapsular fractures (AO Foundation 2018; Evans 1949; Jensen 1980). They are generally subdivided depending on their relationship to the greater and lesser trochanters, the two bony projections present at the upper end of the femur, and the complexity of the fracture configuration. It is increasingly clear that each of these classifications is limited in its generalisability since inter‐ and intra‐observer agreement is poor. Table 4 provides a description of the most recent classification of trochanteric fractures (AO Foundation 2018). For this Cochrane Review, we plan to use a pragmatic simplification of these classifications as follows.

1. Trochanteric region fractures: type and surgical management (revised AO/OTA classification, January 2018).

| Type | Features | Stability | Description |

| Simple, pertrochanteric fractures (A1) |

|

Stable | The fracture line can begin anywhere on the greater trochanter and end either above or below the lesser trochanter. The medial cortex is interrupted in only 1 place. |

| Multifragmentary pertrochanteric fractures (A2) |

|

Unstable | The fracture line can start laterally anywhere on the greater trochanter and runs towards the medial cortex which is typically broken in 2 places. This can result in the detachment of a third fragment which may include the lesser trochanter. |

| Intertrochanteric fractures (A3) |

|

Unstable | The fracture line passes between the 2 trochanters, above the lesser trochanter medially and below the crest of the vastus lateralis laterally. |

AO/OTA: Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (German for "Association for the Study of Internal Fixation") / Orthopaedic Trauma Association

Trochanteric fractures: those that lie mostly between the intertrochanteric line and a transverse line at the level of the lesser trochanter. These can be further divided into simple two‐part stable fractures and comminuted or reverse obliquity unstable fractures.

Subtrochanteric fractures: those that mostly lie in the region bordered by the lesser trochanter and 5 cm distal to the lesser trochanter.

Approximately 40% of hip fractures are extracapsular, of which 90% are trochanteric and 10% are subtrochanteric (NHFD 2017).

Description of the intervention

Internationally, many guidelines exist concerning hip fracture management (e.g. AAOS 2014; NICE 2011; SIGN 2009). Each recommends that early surgical management, generally within 24 to 48 hours, is the mainstay of care for most hip fractures. The overall goal of surgery in the older population is to facilitate early rehabilitation, enabling early mobilisation and the return to premorbid function while minimising the complication risk. This approach has been associated with reductions in mortality in many worldwide registries (Neufeld 2016; Sayers 2017). A proposed grouping of arthroplasty interventions is given in Table 5.

2. Proposed grouping of different types of arthroplasty for hip fracture in adults.

| Implant category | Variable (articulation/fixation technique) | Implant subcategory | Examplesa | Description |

| Total hip arthroplasty | Articulation | Femoral head and acetabular bearing surface materials |

|

Bearing surfaces may be grouped into hard (ceramic and metal) and soft (polyethylene variants). Arthroplasties exist with many of the possible combinations of these bearing surfaces. |

| Femoral head size |

|

Over the development of hip arthroplasty, different sizes of femoral head have been used, from 22 mm to very large diameters approximating that of the native femoral head. The size of the head represents a compromise between stability and linear and volumetric wear at the articulation. The optimum size varies by indication and bearing materials. 36 mm is considered as a cut‐off between standard and large sizes. | ||

| Acetabular cup mobility |

|

A standard THA has a single articulating surface between the femoral head and acetabulum bearing surface. Alternative designs incorporate a further articulation within the structure of the femoral head. | ||

| Fixation technique | Cemented |

|

Both components are cemented with polymethylmethacrylate bone cement that is inserted at the time of surgery. It sets hard and acts a grout between the prosthesis and the bone. | |

| Modern uncemented |

|

Neither component is cemented but rely on osseous integration forming a direct mechanical linkage between the bone and the implant. The femoral prosthesis may be coated with a substance such as hydroxyapatite which promotes bone growth into the prosthesis. Alternatively, the surface of the prosthesis may be macroscopically and microscopically roughened so that bone grows onto the surface of the implant. The acetabular component may be prepared similarly and may or may not be augmented with screws fixed into the pelvis. | ||

| Hybrid | Combinations | The femoral stem is cemented and the acetabular cup is uncemented. | ||

| Reverse hybrid | Combinations | The acetabular cup is cemented and the femoral stem is uncemented. | ||

| Hemiarthroplasty | Articulation | Unipolar |

|

A single articulation between the femoral head and the native acetabulum. The femoral component can be a single ‘monoblock’ of alloy or be modular, assembled from component parts during surgery. |

| Bipolar |

|

The object of the second joint is to reduce acetabular wear. This type of prosthesis has a spherical inner metal head with a size between 22 to 36 mm in diameter. This fits into a polyethylene shell, which in turn is enclosed by a metal cap. There are a number of different types of prostheses with different stem designs. | ||

| Fixation technique | First‐generation uncemented |

|

These prostheses were designed before the development of polymethylmethacrylate bone cement and were therefore originally inserted as a ‘press fit’. Long‐term stability through osseus integration was not part of the design concept. | |

| Cemented |

|

The femoral stem is cemented with polymethylmethacrylate bone cement that is inserted at the time of surgery. It sets hard and acts a grout between the prosthesis and the bone. | ||

| Modern uncemented |

|

The femoral stem relies on osseous integration forming a direct mechanical linkage between the bone and the implant. A prosthesis may be coated with a substance such as hydroxyapatite, which promotes bone growth into the prosthesis. Alternatively, the surface of the prosthesis may be macroscopically and microscopically roughened so that bone grows onto the surface of the implant. |

aThis list is not exhaustive.

Abbreviations: CoC: Ceramic‐on‐ceramic CoP: Ceramic‐on‐polyethylene CPT: collarless polished tapered HCL: Highly cross‐linked MoM: Metal‐on‐metal MoP: Metal‐on‐polyethylene THA: total hip arthroplasty

Arthroplasty

Arthroplasty entails replacing part or all of the hip joint with an endoprosthesis: an implant constructed of non‐biological materials such as metal, ceramic, or polyethylene. Arthroplasties can be grouped into two main categories: hemiarthroplasty (HA) where only the femoral head and neck are replaced, and total hip arthroplasty (THA) where both the femoral head and the acetabulum or socket are replaced.

Hemiarthroplasty

Hemiarthroplasty involves replacing the femoral head with a prosthesis whilst retaining the natural acetabulum and acetabular cartilage. The type of HA can be broadly divided into two groups: unipolar and bipolar. In unipolar HAs, the femoral head is a solid block of metal. Bipolar femoral heads include a single articulation that allows movement to occur, not only between the acetabulum and the prosthesis, but also at this joint within the prosthesis itself.

The best known of the early HA designs are the Moore prosthesis (1952) and the FR Thompson Hip Prosthesis (1954). These are both monoblock implants and were designed before the development of polymethylmethacrylate bone cement. They were therefore originally inserted as a ‘press fit’. The Moore prosthesis has a square femoral stem, which is fenestrated and has a shoulder to enable stabilisation within the femur; this resists rotation within the femoral canal. It is generally used without cement and, in the long term, bone in‐growth into the fenestrations can occur. The Thompson prosthesis has a smaller stem without fenestrations and is now often used in conjunction with cement. Numerous other designs of unipolar HAs exist, based on stems that have been used for THAs.

In bipolar prostheses, there is an articulation within the femoral head component itself. In this type of prosthesis, there is a spherical inner metal head between 22 mm and 36 mm in diameter. This fits into a polyethylene shell, which in turn is enclosed by a metal cap. The objective of the second joint is to reduce acetabular wear by promoting movement at the intraprosthetic articulation rather than with the native acetabulum. There are a number of different types of prostheses with different stem designs. Examples of bipolar prostheses are the Charnley‐Hastings, Bateman, Giliberty, and the Monk prostheses, but many other types with different stem designs exist.

Total hip arthroplasty

Total hip arthroplasty (also known as total hip replacement) involves the replacement of the acetabulum in addition to the femoral head. The first successful THA was developed by John Charnley, using metal alloy femoral heads articulating with polyethylene acetabular components. Subsequently, the articulating materials have diversified, and designs using metal alloys, ceramics, and various polyethylenes in various combinations have all been used.

Component fixation

Irrespective of the nature of the articulating surfaces, the components must be fixed to the bone to ensure longevity of the arthroplasty. The two approaches used to achieve this fixation are cemented and uncemented designs.

Cemented systems

Polymethylmethacrylate bone cement may be inserted at the time of surgery. It sets hard and acts as a grout between the prosthesis and the bone at the time of surgery. Potential advantages of cement are a reduced risk of intraoperative fracture, later periprosthetic fracture, and not relying on integration of the prosthesis with osteoporotic bone. Major side effects of cement are cardiac arrhythmias and cardiorespiratory collapse, which occasionally occur following its insertion. These complications may be fatal, leading either to embolism from marrow contents forced into the circulation (Christie 1994), or a direct toxic effect of the cement.

Uncemented systems

Uncemented systems rely on osseous integration forming a direct mechanical linkage between the bone and the implant. A prosthesis may be coated with a substance, such as hydroxyapatite, which promotes bone growth into the prosthesis. Alternatively, the surface of the prosthesis may be macroscopically and microscopically roughened so that bone grows onto the surface of the implant.

The general complications of both types of arthroplasty are those general to surgical management of hip fracture ‐ namely, pneumonia, venous thromboembolism, infection, acute coronary syndrome, and cerebrovascular accident ‐ and those specific to arthroplasty, including dislocation of the prosthesis, loosening of the components, acetabular wear, and periprosthetic fracture.

Why it is important to do this review

This review replaces the Cochrane Review, Parker 2010a, on the same topic. We used up‐to‐date review methods and have optimised current relevance in terms of patient population, implants used, and outcomes for policymaking bodies, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, as well as international audiences. Since Parker 2010a, clinical uncertainty remains as to the optimum implant for older adults. Moreover, further studies have been reported since the last literature search in September 2009.

Appraisal and synthesis of contemporary evidence may enable more robust conclusions to be made to better inform practice. Furthermore, for displaced intracapsular fractures, the recommended treatment is either HA or THA (Parker 2010a; Hopley 2010; NICE 2011). However, there is a lack of evidence regarding whether older adults experience better outcomes with THA or HA. Recent research has also found interhospital variation and systematic inequalities in the provision of THA (Perry 2016). Further evidence is necessary to verify which individuals gain the most from THA. For treatment of undisplaced intracapsular fractures, there is also a gap in the evidence that resulted in the recently updated NICE guideline being unable to make an evidence‐based recommendation on the best surgical management strategy (NICE 2011). Other reviews that will address other types of interventions are in preparation; we focus on arthroplasty in this review.

Objectives

To determine the effects of different designs, articulations, and fixation techniques of arthroplasties for treating hip fractures in older adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that assessed surgical interventions for the management of people with hip fracture. Quasi‐RCTs are trials in which the methods of allocating people to a trial are not properly random, but are intended to produce similar groups (Cochrane 2018). We included trials published as conference abstracts, provided the trial authors reported sufficient data relating to the methods and outcomes of interest. We aimed to include unpublished data if identified in the searches.

Types of participants

We included adults undergoing surgery in a hospital setting for fragility (low‐energy trauma) hip fractures. We included displaced and undisplaced intracapsular or extracapsular fractures which we expected to be caused by low‐energy trauma.

We expected trial populations to have a mean age of between 80 to 85 years, and include 70% women, 30% with chronic cognitive impairment, and 50% with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score greater than II, indicating that people may have a disease or condition affecting their fitness before surgery (NHFD 2017; NICE 2011). These characteristics would be representative of the general hip fracture population.

We excluded studies that focused exclusively on the treatment of participants: younger than 16 year of age; with fractures caused by specific pathologies other than osteoporosis; and with high‐energy traumas. However, we took a pragmatic approach to study inclusion criteria, and included studies with mixed populations (fragility and other mechanisms, ages, or pathologies). We expected that participants with standard fragility fractures were most likely to outnumber those with high‐energy trauma or local pathological fractures; therefore, the results will be generalisable to the fragility fracture population. If the data were reported separately for standard fragility fractures, we planned to use this subgroup data in our main analysis.

We did not pool studies in which the fracture type is mixed (intracapsular and extracapsular).

Types of interventions

We included all hip prostheses: unipolar HA, bipolar HA, or THA (small and large head), applied with or without cement. We included the following comparisons in the review.

Prostheses inserted with cement versus without cement (stratified by THA versus HA; HA group subgrouped by modern versus first‐generation uncemented stems).

Bipolar HA versus unipolar HA (subgrouped by cemented versus uncemented).

HAs versus other HAs (subgrouped by modern stem design (‘ODEP 3A rating') and first‐generation stem design (e.g. Austin‐Moore or Thompson).

THA versus HA (cemented or uncemented, subgrouped by old versus new, as described above);

Single versus multiple (dual/triple) articulations of THA.

Large‐head THA (36 mm diameter or larger) versus other arthroplasty (stratified by THA versus HA).

We created a detailed table of interventions, grouping them by characteristics, and indicating which are in worldwide use. We prepared this table for the protocol with clinical authors and with the International Fragility Fracture Network (www.fragilityfracturenetwork.org/), and we updated it during review preparation to include all implants used in the included studies (Table 5).

Types of outcome measures

Depending on the length of follow‐up reported, we categorised the endpoints for outcomes into 'early' (up to and including 4 months), 12 months (prioritising 12‐month data, but in its absence including data after 4 months and up to 24 months) and 'late' (after 24 months, up to the end of study follow‐up). We selected four months as the definition of 'early' because most of early recovery has been achieved at this time point (Griffin 2015). This decision is also in accordance with the core outcome set for hip fracture, which prioritises early outcome over late recovery (Haywood 2014). Although priority was given to early outcomes in the presentation of our data, we also included outcome data at the '12 months' and 'late' times points.

Critical outcomes

We extracted information on the following seven 'critical' outcomes.

Activities of daily living (e.g. Barthel Index (BI), Functional Independence Measure (FIM)).

Delirium using recognised assessment scores, such as Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) mental test score and the four 'A's test (4AT).

Functional status (region‐specific) (e.g. hip rating questionnaire, Harris Hip Score, Oxford Hip Score).

Health‐related Quality of Life (HRQoL) (e.g. Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36), EuroQol‐5 Dimensions (EQ‐5D)).

Mobility (e.g. indoor/outdoor walking status, Cumulated Ambulation Score, Elderly Mobility Scale Score, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, Short Physical Performance Battery, self‐reported walking scores (e.g. Mobility Assessment Tool ‐ short form)).

Mortality.

Unplanned return to theatre: secondary procedure required for a complication resulting directly or indirectly from the index operation or primary procedure.

Other important outcomes

We also reported the following 'important' outcomes.

Pain (verbal rating or visual analogue scale (VAS)).

Length of in‐hospital stay.

Discharge destination. We used study authors’ definitions, which were variably defined in the included studies.

Adverse events.

We grouped adverse events by relatedness to the implant or fracture, or both. We reported each adverse event type separately for maximum clarity, and included the following.

Related

Damage to a nerve, tendon, or blood vessel.

Intraoperative periprosthetic fracture.

Postoperative periprosthetic fracture.

Loosening of prosthesis.

Wound infection. We used study authors' definitions, which often distinguished deep infection and superficial infection.

Dislocation.

Unrelated

Acute kidney injury.

Blood transfusion.

Cerebrovascular accident.

Chest infection/pneumonia.

Decreased cognitive ability.

Myocardial infarction/acute coronary syndrome.

Sepsis.

Urinary tract infection.

Venous thromboembolic phenomena.

Search methods for identification of studies

As well as developing a strategy for this review, we developed general search strategies for the large bibliographic databases to find records to feed into a number of Cochrane Reviews and review updates on hip fracture surgery (Lewis 2021; Lewis 2022a; Lewis 2022b; Lewis 2022c). We searched the main databases up to July 2020.

Electronic searches

We identified RCTs and quasi‐RCTs through literature searching with systematic and sensitive search strategies, as outlined in Chapter 4 of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2019, hereafter referred to as the Cochrane Handbook). We applied no restrictions on language, date, or publication status. We searched these databases for relevant trials:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; CRS Web; 8 July 2020);

MEDLINE (Ovid; 1946 to 6 July 2020);

Embase (Ovid; 1980 to 7 July 2020);

Web of Science (SCI EXPANDED; 1900 to 8 July 2020);

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; Cochrane Library; 7 July 2020);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/; 17 December 2018);

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/; 17 December 2018);

Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org/; 9 July 2020);

Proquest Dissertations and Theses (Proquest; 1743 to 8 July 2020);

National Technical Information Service (NTIS, for technical reports; www.ntis.gov/; 10 July 2020).

We developed a subject‐specific search strategy in MEDLINE and other listed databases. We adapted strategies with consideration of database interface differences as well as different indexing languages. In MEDLINE, we used the sensitivity‐maximising version of the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials (Lefebvre 2019). In Embase, we used the Cochrane Embase filter (www.cochranelibrary.com/central/central-creation) to focus on RCTs. We ran the initial searches in November and December 2018, and a top‐up search in July 2020 in all databases except for DARE and HTA, in which no new records had been added since the initial search. At the time of the search, CENTRAL was fully up to date with all records from the Cochrane Bone, Joint, and Muscle Trauma (BJMT) Group's Specialised Register, and so it was not necessary to search this separately. We developed the search strategy in consultation with Information Specialists (see Acknowledgements) and the Information Specialist for the BJMT Group. Search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

We scanned ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov/) for ongoing and unpublished trials on 10 July 2020.

Searching other resources

We handsearched these conference abstracts from 2016 to November 2018:

Fragility Fractures Network Congress;

British Orthopaedic Association Congress;

Orthopaedic World Congress (SICOT);

Orthopaedic Trauma Association Annual Meeting;

Bone and Joint Journal Orthopaedic Proceedings;

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Annual Meeting.

To identify further studies, we screened the reference lists of studies included in Parker 2010a as well as the reference lists of eligible studies and systematic reviews published within the last five years that were retrieved by the searches.

Data collection and analysis

In order to reduce bias, we ensured that any review author who is a co‐applicant, study author, or has or has had an advisory role on any potentially relevant study, remained independent of study selection decisions, risk of bias assessment, and data extraction for their study.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts of all the retrieved bibliographic records in a web‐based systematic reviewing platform, Rayyan (Ouzzani 2016), and in the top‐up search using Covidence. Full texts of all potentially eligible records passing the title‐ and abstract‐screening level were retrieved and examined independently by two review authors against the eligibility criteria described in Criteria for considering studies for this review. We conducted full‐text screening using Covidence. We resolved disagreements through discussion or by adjudication of a third review author. We excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We prepared a PRISMA flow diagram to outline the study selection process, numbers of records at each stage of selection, and reasons for exclusions of full‐text articles (Moher 2009). We reported in the review details of key excluded studies, rather than all studies that were excluded from consideration of full‐text articles.

Data extraction and management

All review authors conferred on the essential data for extraction. We designed a data extraction form that aligns with the default headings in the Characteristics of included studies (see Appendix 2). Two review authors independently piloted the form on five studies and compared results. We then made changes to the template following additional discussion with the review author team. For the remaining data extraction, one review author independently extracted data and a second review author checked all the data for accuracy. We extracted the following data.

Study methodology: publication type; sponsorship/funding/notable conflicts of interest of trial authors; study design; numbers of centres and locations; size and type of setting; study inclusion and exclusion criteria; randomisation method; number of randomised participants, losses (and reasons for losses), and number analysed for each outcome. (Collecting information relating to the participant flow helped the assessment of risk of attrition bias.)

Population: baseline characteristics of the participants by group and overall (age, gender, smoking history, medication, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, functional status such as previous mobility, place of residence before fracture, cognitive status, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status, fracture type and displacement).

Interventions: details of each intervention (number and type, manufacturer details); general surgical details (number of clinicians and their skills and experience, perioperative care such as use of prophylactic antibiotics or antithromboembolics, mobilisation or weight‐bearing protocols).

Outcomes: all outcomes measured or reported by study authors; outcomes relevant to the review (including measurement tools and time points of measure); extraction of outcome data into data and analysis tables or additional tables in Review Manager 2014.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011a). We assessed the following domains.

Sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants, personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other risks of bias.

We considered risk of detection bias separately for: subjective outcomes measured by clinicians, objective outcomes measured by clinicians, and participant‐reported outcomes (e.g. pain and HRQoL). For each domain, two review authors judged whether study authors made sufficient attempts to minimise bias in their design. For each domain, we made judgements using three measures ‐ high, low, or unclear risk of bias ‐ and we recorded these judgements in risk of bias tables.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous data outcomes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs); it was not appropriate to use Peto odds ratio (OR) to calculate effects because no outcomes had very low numbers of observed events. We expressed treatment effects for continuous data outcomes evaluated using the same measurement scales as mean differences (MD) with 95% CI. For outcomes measured using different scales, we used standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% CI.

In the event that studies reported dichotomous data using more than one category, we selected these cut‐off points in the distribution of categories:

for functional status: we reported data for those with a score of excellent or good (using Harris Hip Score (HHS)) versus those with a score of moderate or poor;

for mobility: we reported data for those who were able to walk independently out of doors with no more than the use of one stick (NICE 2011), versus those who were more dependent;

for pain: we reported data for participants who reported no pain versus those who reported any category of pain;

for discharge destination: we reported data for participants who were discharged home versus those who were discharged to a care environment.

Unit of analysis issues

In preparation of the review, we encountered potential unit of analysis issues. We found that some studies reported number of hip fractures (or cases) as well as the number of participants, with a very small number of participants having two fractured hips. Often, differentiating the denominators within a report was challenging. In such studies, depending on the outcome, the unit of analysis was either the participant (for example, for outcomes such as mortality, discharge destination, or some adverse events), or the case (for example, for outcomes such as unplanned return to theatre). We noted this differentiation where applicable and used the unit of analysis (participants or case) that was appropriate for the outcome within these studies. One study included three intervention groups (Dorr 1986). We created a pairwise comparison by combining the data for the two HA groups (cemented and uncemented) and comparing these data with the THA group. Although the review included a comparison of cemented HA versus uncemented HA, we did not use data from these two study arms in this comparison because recruitment to these two groups was completed at different time points within the study period and thus it was not appropriate to compare these against one another.

Dealing with missing data

For each included study, we recorded the number of participant losses for each outcome. Unless reported otherwise, we assumed complete case data for mortality, unplanned return to theatre, and adverse events. For outcomes that required participant assessment at end of follow‐up (such as HRQoL), we prioritised intention‐to‐treat (ITT) data where these data were available. If ITT data were unavailable for these outcomes, and if study authors did not clearly report denominator figures for each group for the outcome, we reduced the denominator figure in each group to account for reported mortality. We did not impute missing data. We used the risk of bias tool to judge attrition bias. We judged studies to be at high risk of attrition bias if we noted large amounts of unexplained missing data, loss that could not be easily justified in the study population, or losses were not sufficiently balanced between intervention groups. If we included a study with high attrition bias, we explored the effect during sensitivity analysis. We completed sensitivity analysis only for critical review outcomes and only considered attrition for outcomes that may be affected by these losses.

We attempted to contact study authors of more recently published trials when we noted that data for critical outcomes appeared to be measured but not reported. Where standard deviations were not reported, we attempted to determine these from other reported data (such as standard errors, confidence intervals, or exact P values). We noted in the Characteristics of included studies when we could not use outcome data because they were insufficiently reported or because numbers of losses in each group were not clearly specified.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I2 statistic, automatically calculated in Review Manager 2014 software, to quantify the possible degree of heterogeneity of treatment effects between trials. We assumed moderate heterogeneity when the I2 was between 30% and 60%; substantial heterogeneity when it was between 50% and 90%; and considerable heterogeneity when it was between 75% and 100%. We noted the importance of I2 depending on: 1) magnitude and direction of effects; and 2) strength of evidence for heterogeneity. We did not have sufficient studies to investigate statistical heterogeneity (Deeks 2017).

We assessed clinical and methodological diversity in terms of participants, interventions, outcomes, effect modifiers, and study characteristics for the included studies to determine whether a meta‐analysis was appropriate; we used the information collected during data extraction (Data extraction and management).

We visually inspected forest plots to look at the consistency of intervention effects across included studies. If the studies were estimating the same intervention effect, there should be overlap between the CIs for each effect estimate on the forest plot, but if overlap is poor, or there are outliers, then statistical heterogeneity may be likely.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to investigate the potential for publication bias and explore possible small‐study biases using funnel plots. However, we had insufficient studies (fewer than 10 studies) for most outcomes (Sterne 2017). For outcomes with 10 or more studies, we constructed a funnel plot and interpreted the plot using a visual inspection and the Harbord modified test in Stata; for the critical review outcomes, we reported P values for the Harbord modified test. We incorporated this judgement into the assessment of publication bias within the GRADE assessment.

To assess outcome reporting bias, we screened clinical trials registers for protocols and registration documents of included studies that were prospectively published, and we sourced all clinical trials register documents that were reported in the study reports of included studies. We used evidence of prospective registration to judge whether studies were at risk of selective reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We conducted meta‐analyses only when meaningful; that is, when the treatments, participants, and the underlying clinical question were similar enough for pooling to make sense. We pooled results of comparable groups of trials using random‐effects models. We chose this model after careful consideration of the extent to which any underlying effect could truly be thought to be fixed, given the complexity of the interventions included in this review. We presented 95% CIs throughout. We found that some studies reported outcome data at more than one time point and we reported the data within three time point windows for these studies. Early data included data up to four months, with priority given to data closest to four months; 12‐month data included a window from later than four months up to 24 months, but with priority given to data at 12 months; and late data, which included data reported after 24 months at the latest time point reported by study authors. For studies that reported outcome data using more than one measurement tool, we selected the tool that was used most commonly by other studies in the comparison group, or which reported data for the largest number of participants.

We considered the appropriateness or otherwise of pooling data where there was considerable heterogeneity (I2 statistic value of greater than 75%) that could not be explained by the diversity of methodological or clinical features amongst trials. We presented data from these studies in the analyses and clearly reported these observations in the text for the critical outcomes in the review.

If effect sizes were statistically significant, we considered whether the effect was clinically important. We based these decisions on established minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) for the measurement tool, or used Cohen's effect sizes as a guide if MCIDs were unavailable (Schünemann 2019a).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Few outcomes provided evidence from at least 10 studies to justify subgroup analysis. Although we aimed to explore possible sources of heterogeneity between studies (key effect modifiers such as age, gender, cognitive impairment, and fracture displacement and location), these possible effect modifiers were insufficiently reported to allow for meaningful subgroup analysis.

We planned to subgroup prostheses according to whether a modern or first‐generation uncemented stem was used (see Types of interventions), and we reported the test for subgroup differences in outcomes that had at least 10 studies.

There is no explicit means of accounting for step changes in co‐interventions, certainly not one that would be applicable to the worldwide totality of the evidence. Therefore, we could not try to explain any heterogeneity by statistical test of subgroups defined by co‐intervention. However, we ordered forest plots by date of recruitment so that any temporal trend could be inspected visually and commented on.

Sensitivity analysis

We used sensitivity analysis to explore the effects of risks of bias on the review's critical outcomes. If pooled analyses had at least two studies, we excluded studies that were:

at high or unclear risk of selection bias for sequence generation (this included studies described as quasi‐randomised, or those that did not adequately describe methods used to randomise participants to intervention groups); or

at high risk of attrition bias (because studies reported a large number of losses that were unexplained or not justified for this population, or losses that were unbalanced between groups, and that we expected could influence outcome data).

We compared the effect estimates in the sensitivity analysis with the effect estimates in the primary analysis, and we reported the effect estimates from sensitivity analyses only if we noted a difference in our interpretation of the effect. We planned to conduct sensitivity analysis by excluding studies that had mixed populations, but these data were inadequately reported by study authors and did not allow for meaningful analysis. We also planned, but did not conduct, sensitivity analysis by excluding studies of interventions that are not currently in clinical use. We obtained the general view that all interventions at the major‐grouping level (implant sub‐category level in Table 5) remain in current use. Although some types of implant may no longer be manufactured, we believe the distinction between implants within the same category is marginal and that sensitivity analysis would not be meaningful.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Two review authors used the GRADE system to assess the certainty of the body of evidence associated with the seven critical outcomes in the review (Schünemann 2019b):

activities of daily living (ADL);

delirium;

functional status;

health‐related quality of life (HRQoL);

mobility;

mortality (measured within four months of surgery, and at 12 months);

unplanned return to theatre.

For outcomes that were reported using more than one measurement tool, and that could not be combined in analysis, we assessed the certainty of the evidence for the outcome that used a measurement tool with the most participants.

The GRADE approach assesses the certainty of a body of evidence based on the extent to which we can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. Evaluation of the certainty of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (study limitations), directness of the evidence (indirectness), heterogeneity of the data (inconsistency), precision of the effect estimates (imprecision), and risk of publication bias. The certainty of the evidence could be high, moderate, low or very low, being downgraded by one or two levels depending on the presence and extent of concerns in each of the five GRADE domains. We used footnotes to describe reasons for downgrading the certainty of the evidence for each outcome, and we used these judgements when drawing conclusions in the review.

We did not construct summary of findings tables for all comparisons in this review. Instead, we selected three comparisons that provided the most substantial body of evidence. These provided evidence for each of our comparison types in our review objectives (different fixation techniques, different articulations, and different designs). We therefore constructed summary of findings tables for the following comparisons in this review, using the GRADE profiler software (GRADEpro GDT).

Cemented HA versus uncemented HA.

Bipolar HA versus unipolar HA.

THA versus HA.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification, and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

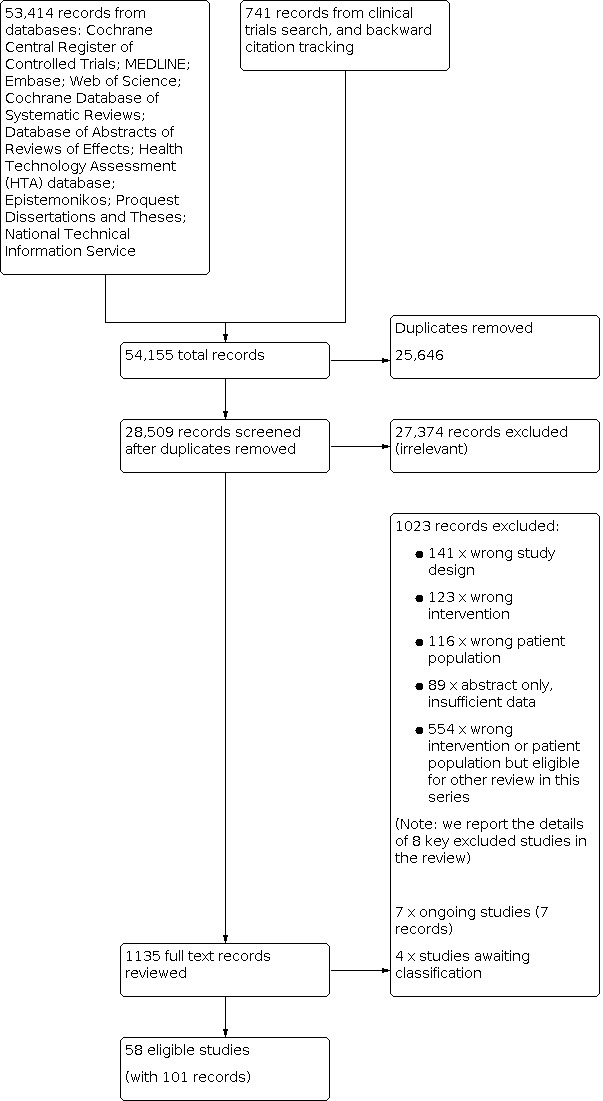

After the removal of duplicates from the search results, we screened 28,509 titles and abstracts, which included backward citation searches and searches of clinical trials registers. We reviewed the full texts of 1135 records and selected 58 studies (with 101 records) for inclusion in this review. We linked any references pertaining to the same study under a single study ID. We excluded 1023 records, and report the details of eight key studies from these excluded records. Four studies are awaiting classification, and we identified seven ongoing studies. See Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies. Two studies were reported only as abstracts with limited study characteristics (Moroni 2002; Patel 2008).

Types of studies and setting

Whilst most studies were RCTs, eight studies used methods to allocate participants to interventions which we assessed as quasi‐randomised (Abdelkhalek 2011; Dorr 1986; Iorio 2019; Livesley 1993; Ravikumar 2000; Santini 2005; Sonaje 2017; Stoffel 2013).

Eleven were multicentre studies, and the remainder were single centre studies. Eighteen studies were completed in the UK (Baker 2006; Brandfoot 2000; Calder 1995; Calder 1996; Davison 2001; Emery 1991; Fernandez 2022; Griffin 2016; Harper 1994; Keating 2006; Livesley 1993; Parker 2010c; Parker 2012; Parker 2019; Parker 2020; Ravikumar 2000; Sadr 1977; Sims 2018), six in Sweden (Blomfeldt 2007; Chammout 2017; Chammout 2019; Cornell 1998; Hedbeck 2011; Inngul 2015), four in South Asia (Malhotra 1995; Rehman 2014; Sharma 2016; Sonaje 2017), four in Italy (Cadossi 2013; Iorio 2019; Moroni 2002; Santini 2005), four in the USA (DeAngelis 2012; Dorr 1986; Macaulay 2008; Raia 2003), three in Norway (Figved 2009; Figved 2018; Talsnes 2013), three in China (Cao 2017; Ren 2017; Xu 2017), three in Australasia (Jeffcote 2010; Stoffel 2013; Taylor 2012), two in the Netherlands (Moerman 2017; Van den Bekerom 2010), two in Egypt (Abdelkhalek 2011; Rashed 2020), and two in South Korea (Kim 2012; Lim 2020). HEALTH 2019 was an international study conducted in Canada, Finland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Spain, the UK, and the USA. The remainder were conducted in other European countries (Kanto 2014; Mouzopoulos 2008; Movrin 2020; Sonne‐Holm 1982; Vidovic 2013), and one study did not report where the study was conducted (Patel 2008).

Studies were published between 1977 and 2020, and we include one study that we expect to be published in 2021. Approximately two‐thirds of the studies were published since 2010.

Types of participants

In total, 10,654 participants, with 10,662 hip fractures, were recruited across the 58 studies. All studies included only participants with intracapsular fractures, except for Cao 2017 (85 participants), which included only participants with extracapsular fractures. Blomfeldt 2007 is the only study to report the inclusion of undisplaced fractures, which was only 2% of the reported study population. Nine studies did not report whether the fracture was displaced (Cadossi 2013; Cao 2017; Dorr 1986; Malhotra 1995; Moroni 2002; Patel 2008; Santini 2005; Sonne‐Holm 1982; Xu 2017), and the remainder included displaced fractures only. One study recruited participants that had neglected fractures, more than 30 days old (Xu 2017).

Most studies specified a lower age limit for recruited participants of at least 50 years (HEALTH 2019; Macaulay 2008), 55 years (DeAngelis 2012; Dorr 1986; Rashed 2020), 60 years (Baker 2006; Fernandez 2022; Griffin 2016; Iorio 2019; Jeffcote 2010; Parker 2010c; Parker 2019; Rehman 2014; Sharma 2016; Sims 2018; Sonaje 2017; Xu 2017), 65 years (Cao 2017; Chammout 2017; Cornell 1998; Davison 2001; Kanto 2014; Lim 2020; Raia 2003; Ravikumar 2000; Santini 2005), 70 years (Blomfeldt 2007; Cadossi 2013; Figved 2009; Figved 2018; Moerman 2017; Patel 2008; Sonne‐Holm 1982; Taylor 2012; Van den Bekerom 2010; Vidovic 2013), 75 years (Moroni 2002; Movrin 2020; Talsnes 2013), and 80 years (Calder 1996; Chammout 2019; Hedbeck 2011; Inngul 2015). Only five studies applied an upper age limit, which was 79 years (Calder 1995; Chammout 2017; Davison 2001), 80 years (Rashed 2020), and 90 years (Blomfeldt 2007). Where reported, the mean ages of participants ranged from 63 years to 87 years.

Seven studies did not report the baseline sex of the participants (Griffin 2016; Livesley 1993; Patel 2008; Ravikumar 2000; Sonaje 2017; Sonne‐Holm 1982; Stoffel 2013). In studies that reported sex distribution, there were 6835 female participants, which represented 71% of the sample in these studies. Approximately one third of the studies specified the ability to walk prior to surgery as an inclusion criteria or required participants to be free of any cognitive impairment. Almost half of the studies stated that pathological fractures would not be included.

The mean follow‐up time period was 24.3 (SD ± 109) months, with a range from 1 week (Malhotra 1995), to 13 years (Ravikumar 2000).

Types of interventions

We included 21 studies with 4282 participants that compared prostheses that were cemented or uncemented; as part of treatment with a THA (Chammout 2017), a HA (Brandfoot 2000; Cao 2017; DeAngelis 2012; Emery 1991; Fernandez 2022; Figved 2009; Harper 1994; Moerman 2017; Movrin 2020; Parker 2010c; Parker 2020; Rehman 2014; Sadr 1977; Santini 2005; Sonne‐Holm 1982; Talsnes 2013; Taylor 2012; Vidovic 2013), or a mixture of either a THA or HA (Inngul 2015; Moroni 2002). We briefly summarise the characteristics of these studies and the critical review outcomes they report that are relevant to this review in Table 6.

3. Implant and study characteristics. Prostheses implanted with cement versus without cement.

| Study ID |

Type of cemented implant Type of uncemented implant |

Study design (N) | Displaced fractures, % | Critical review outcomes (time point, n) |

| Brandfoot 2000 | 1. Cemented, Thompson, unipolar 2. Uncemented Thompson, unipolar |

RCT (91) | 98 | Mortality (16 months, 91) |

| Cao 2017 | 1. Cemented, stem type and uni/bipolar NR 2. Uncemented, stem type and uni/bipolar NR |

RCT (85) | NR | Function (3 and 6 months, 85) |

| Chammout 2017 | 1. Cemented, modular CPT, 32 mm head, cemented cup 2. Uncemented, Bi‐Metric stem, 32 mm head, cemented cup |

RCT (69) | 100 | ADL (3 months, 65; 24 months, 59) Function (24 months, 65) HRQoL (3 months, 64; 12 months, 62) Mortality (12 months, 69) Unplanned return to theatre (24 months, 69) |

| DeAngelis 2012 | 1. Cemented, VerSys stem, unipolar 2. Uncemented, beaded stem, unipolar |

RCT (130) | 100 | Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 130) |

| Emery 1991 | 1. Cemented, Thompson, bipolar 2. Uncemented, Moore, bipolar |

RCT (53) | 100 | Mobility (3 months, 39) Mortality (3 and 17/18 months, 53) |

| Figved 2009 | 1. Cemented, Spectron, bipolar 2. Uncemented, Corail, bipolar |

RCT (230 fractures, 223 participants) | 100 | ADL (3 months, 190; 12 months, 168) Function (3 months, 189; 12 months, 167) HRQoL (3 months, 143; 12 months, 113) Mobility (3 months, 190; 12 months, 168) Mortality (3 and 12 months, 213) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 217) |

| Harper 1994 | 1. Cemented, Thompson, unipolar 2. Uncemented, Thompson, unipolar |

RCT (137) | 100 | Mortality (3 and 12 months, 137) |

| Inngul 2015 | 1. Cemented, Exeter stem, unipolar or 32mm, cemented cross‐linked polyethylene cup 2. Uncemented, HAC Bimetric stem, unipolar or 32 mm, cemented cross‐linked polyethylene cup |

RCT (141) | 100 | Mortality (4 and 12 months, 141) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 141) |

| Moerman 2017 | 1. Cemented, Muller, bi/unipolar NR 2. Uncemented, DB10, bi/unipolar NR |

RCT (201) | 100 | ADL (3 months, 114; 12 months, 96) HRQoL (3 months, 102; 12 months, 90) Mobility (3 months, 88; 12 months, 74) Mortality (12 months, 201) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 201) |

| Moroni 2002 | 1. Cemented, AHS prosthesis, unipolar or THA 2. Uncemented (HAC), Furlong, unipolar or THA |

RCT (28) | NR | Function (24 months, 28) HRQoL (24 months, 28) Mortality (24 months, 28) |

| Movrin 2020 | 1. Cemented, Muller, bi/unipolar NR 2. Uncemented, DB10, bi/unipolar NR |

RCT (158) | 100 | Function (3 month, 148; 24 months, 94) Mortality (7 days and 24 months, 158) |

| Parker 2010c | 1. Cemented, Thompson, unipolar 2. Uncemented, Moore, unipolar |

RCT (400) | 100 | Delirium (60 months, 400) Mobility (3 months, 327; 60 months, 64) Mortality (12 and 60 months, 400) Unplanned return to theatre (60 months, 400) |

| Parker 2020 | 1. Cemented, Exeter Trauma or CPT, unipolar 2. Uncemented, Furlong, unipolar |

RCT (400) | 100 | ADL (4 months, 329; 12 months 283) Delirium (12 months, 400) Mobility (3 months, 329; 12 months, 282) Mortality (3 and 12 months, 400) |

| Rehman 2014 | 1. Cemented, Thompson, unipolar 2. Uncemented, Moore, unipolar |

RCT (110) | 100 | Mobility (3 months, 110) |

| Sadr 1977 | 1. Cemented, Thompson, unipolar 2. Uncemented, Thompson, unipolar |

RCT (40) | 100 | Function (17 months, 25) Mortality (6 weeks and 12 months, 40) |

| Santini 2005 | 1. Cemented, stem type NR, unipolar 2. Uncemented, stem type NR, unipolar |

RCT (106) | NR | ADL (12 months, 106) Function (12 months, 106) Mobility (unknown time point, 106) Mortality (at hospital discharge and 12 months, 106) |

| Sonne‐Holm 1982 | 1. Cemented, Moore, unipolar 2. Uncemented, Moore, unipolar |

RCT (112) | NR | Function (3 and 12 months, 75) Mobility (3 and 12 months, 75) Mortality (6 weeks, 112) |

| Talsnes 2013 | 1. Cemented, Landos Titan, bipolar 2. Uncemented, Landos Corail, bipolar |

RCT (334) | 100 | Mortality (12 months, 334) |

| Taylor 2012 | 1. Cemented, Exeter, unipolar 2. Uncemented, Zweymuller Alloclassic, unipolar |

RCT (160) | 100 | Mortality (6 weeks and 12 months, 160) Unplanned return to theatre (24 months, 160) |

| Vidovic 2013 | 1. Cemented, modular, unipolar 2. Uncemented, Moore, unipolar |

RCT (79) | 100 | Function (3 months, 79; 12 months, 60) Mortality (12 months, 79) |

| Fernandez 2022 | 1.Cemented HA, stem and head at surgeon's preference 2.Uncemented HA, stem and head at surgeon's preference |

RCT (1225) | 99 | ADL (4 months, 715; 12 months, 580) HRQoL (4 months, 877; 12 months, 876) Mobility (4 months, 715; 12 months, 583) HRQoL (4 months, 877; 12 months, 876) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 1225) Mortality (12 months, 1225) |

ADL: activities of daily living AHS: manufacturer's name for implant CPT: collarless, polished, double‐taper design concept DB: manufacturer's name for implant HAC: hydroxyapatite‐coated HRQoL: health‐related quality of life N: total number randomised n: number analysed NR: not reported RCT: randomised controlled trial

We included 13 studies with 1499 participants that compared a bipolar HA with a unipolar HA (Abdelkhalek 2011; Calder 1995; Calder 1996; Cornell 1998; Davison 2001; Figved 2018; Hedbeck 2011; Jeffcote 2010; Kanto 2014; Malhotra 1995; Patel 2008; Raia 2003; Stoffel 2013). We briefly summarise the characteristics of these studies and the outcomes they report that are relevant to this review in Table 7.

4. Implant and study characteristics. Bipolar HA versus unipolar HA.

| Study ID |

Type of HA bipolar Type of HA unipolar |

Study design (N) | Displaced fractures, % | Critical review outcomes (time point, n) |

| Abdelkhalek 2011 | 1. Mixed cemented/uncemented, bipolar; 2. Mixed cemented/uncemented, unipolar |

Quasi RCT (50) | 100 | Function (4.4 years, 50) Unplanned return to theatre (24 months, 50) |

| Calder 1995 | 1. Monk, cemented, bipolar 2. Thompson, cemented, unipolar | RCT (73) | 100 | Pain (6 months, 73) Mobility (6 months, 73) |

| Calder 1996 | 1. Monk, cemented, bipolar 2. Thompson, cemented, unipolar |

RCT (250) | 100 | Mortality (4 and 12 months, 250) |

| Cornell 1998 | 1. Cemented modular, bipolar 2. Cemented modular, unipolar |

RCT (48) | 100 | Function (6 months, 48) Mobility (6 months, 48) Mortality (6 months, 48) |

| Davison 2001 | 1. Cemented, Monk, bipolar 2. Cemented, Thompson, unipolar |

RCT (187) | 100 | Mortality (12 and 36 months, 187) Unplanned return to theatre (36 months, 187) |

| Figved 2018 | 1. Cemented, 28 mm cobalt chromium head and a SelfCentering Bipolar (DePuy) 2. Cemented, Modular Cathcart Unipolar (DePuy) |

RCT (28) | 100 | Function (48 months, 19) HRQoL (12 months, 25; 48 months, 19) Mortality (3 and 12 months, 28) |

| Hedbeck 2011 | 1. Cemented, UHR (Stryker), from 42 to 72 mm, bipolar 2. Cemented, Exeter modular, unipolar |

RCT (120) | 100 | ADL (12 months, 99) HRQoL (4 months, 115; 12 months, 99) Mortality (4 and 12 months, 120) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 120) |

| Jeffcote 2010 | 1. Cemented, Centrax, bipolar 2. Cemented, Unitrax, unipolar |

RCT (51) | 100 | Mortality (24 months, 51) |

| Kanto 2014 | 1. Cemented, Vario cup, bipolar 2. Cemented, Lubinus, unipolar |

RCT (175) | 100 | Mortality (during hospital stay and 5 years, 175) Unplanned return to theatre (5 years, 175) |

| Malhotra 1995 | 1. Uncemented, Bateman type, bipolar 2. Uncemented; Austin‐Moore; unipolar |

RCT (68) | NR | Function (NR, 66) |

| Patel 2008 | 1. Uncemented, medical internation stem, bipolar 2: Uncemented, Thompson; unipolar |

RCT (40) | 100 | Mortality (13 months, 40) |

| Raia 2003 | 1. Centrax, appropriate‐sized cemented Premise stem, bipolar 2. Unitrax; appropriate‐sized cemented Premise stem, unipolar |

RCT (115) | 100 | Mortality (12 months, 115) |

| Stoffel 2013 | 1. Cemented, collarless polished stem, bipolar 2. Cemented, collarless polished stem, unipolar |

RCT (294) | 100 | Delirium (12 months, 261) Function (12 months, 251) Mobility (12 months, 186) |

ADL: activities of daily living HA: hemiarthroplasty HRQoL: health‐related quality life N: total number randomised n: number analysed NR: not reported RCT: randomised controlled trial UHR: universal head system (manufacturer's name)

We included four studies with 1397 participants that compared different types of HAs. These comparisons were between a short stem and standard stem (Lim 2020), a Thompson and a Exeter Trauma Stem (Parker 2012; Sims 2018), and an Austin‐Moore and a Furlong (Livesley 1993). We briefly summarise the characteristics of these studies and the outcomes they report that are relevant to this review in Table 8.

5. Implant and study characteristics. HAs versus other HAs.

| Study ID | Type of HA in each intervention group | Study design (N) | Displaced fractures, % | Critical review outcomes (time point, n) |

| Lim 2020 | 1. Short stem, Bencox M stem, proximal Ti‐plasma spray microporous coating, uncemented, bipolar 2. Standard stem, Bencox ID stem, proximal Ti‐plasma spray microporous coating, uncemented, standard stem, bipolar |

RCT (151) | 100 | ADL (24 months, 75) Mortality (24 months, 151) |

| Livesley 1993 | 1. HAC bipolar 2. Uncemented; press‐fit Moore‐bipolar |

Quasi‐RCT (82) | 100 | Mortality (1 and 12 months, 82) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 82) |

| Parker 2012 | 1. Uncemented, Exeter, unipolar 2. Cemented, Thompson, unipolar | RCT (200) | 100 | Delirium (12 months, 200) Mortality (3 and 12 months, 200) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 200) |

| Sims 2018 | 1. Uncemented, Exeter, unipolar 2. Cemented, Thompson, unipolar |

RCT (964) | 100 | HRQoL (4 months, 618) Mobility (4 months, 494) Mortality (4 months, 964) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 964) |

ADL: activities of daily living HA: hemiarthroplasty HAC: hydroxyapatite‐coated HRQoL: health‐related quality of life N: total number randomised n: number analysed RCT: randomised controlled trial

We included 17 studies with 3232 participants that compared a THA with a HA (Baker 2006; Blomfeldt 2007; Cadossi 2013; Chammout 2019; Dorr 1986; HEALTH 2019; Iorio 2019; Keating 2006; Macaulay 2008; Mouzopoulos 2008; Parker 2019; Ravikumar 2000; Ren 2017; Sharma 2016; Sonaje 2017; Van den Bekerom 2010; Xu 2017). We briefly summarise the characteristics of these studies and the outcomes they report that are relevant to this review in Table 9.

6. Implant and study characteristics. THA versus HA.

| Study ID |

Type of THA Type of HA |

Study design (N) | Displaced fractures, % | Critical review outcomes (time point, n) |

| Baker 2006 | 1. 28 mm femoral head articulating with an all‐polyethylene Zimmer cemented acetabular cup 2. Endo Femoral Head (Zimmer); cemented; unipolar |

RCT (81) | 100 | Mortality (39 months, 81) |

| Blomfeldt 2007 | 1. Modular Exeter femoral component; 28 mm head; OGEE cemented acetabular component 2. Bipolar; modular Exeter, 28 mm head |

RCT (120) | 100 | ADL (4 months, 114; 12 months, 111) Delirium (4 months, 116) Function (48 months, 83) Mortality (4, 12 and 48 months, 120) |

| Cadossi 2013 | 1. Uncemented Conus stem and a large‐diameter femoral head 2. Uncemented, bipolar |

RCT (96) | 100 | Mortality (12 and 36 months, 96) |

| Chammout 2019 | 1. Cemented 32 mm cobalt‐chromium head; cemented highly cross‐linked polyethylene acetabular component 2. Cemented, unipolar |

RCT (120) | 100 | ADL (3 months, 111; 24 months, 99) Delirium (3 months, 111) Function (24 months, 103) HRQoL (3 months, 111; 12 months, 106) Mortality (24 months, 120) Unplanned return to theatre (24 months, 120) |

| Dorr 1986 | 1. 28 mm head size was used 2. Cemented (n = 37) or uncemented (n = 13), bipolar |

RCT (89) | 100 | Unplanned return to theatre (48 months, 89) |

| HEALTH 2019 | 1. Surgeon's preference 2. Surgeon's preference |

RCT (1495) | 100 | Function (24 months, 669) HRQoL (24 months, 844) Mobility (24 months, 535) Mortality (24 months, 1441) Unplanned return to theatre (24 months, 1441) |

| Iorio 2019 | 1. Dual mobility cup with cementless femoral stem 2. Cementless femoral stem with bipolar head |

RCT (60) | 100 | Mortality (1 and 12 months, 60) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 60) |

| Keating 2006 | 1. NR 2. Bipolar, cemented |

RCT (180) | 100 | Delirium (24 months, 168) Function (24 months, 168) HRQoL (4 and 12 months, 168) Mortality (24 months, 180) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 180) |

| Macaulay 2008 | 1. Surgeon's preference 2. Surgeon's preference |

RCT (41) | 100 | Function (24 months, 40) HRQoL (12 months, 40) Mobility (12 and 24 months, 40) Mortality (24 months, 40) |

| Mouzopoulos 2008 | 1. Plus (DePuy) 2. Merete |

RCT (86) | 100 | ADL (48 months, 43) Function (48 months, 43) Mortality (12 and 48 months, 86) Unplanned return to theatre (48 months, 49) |

| Parker 2019 | 1. CPCS stem (n=29), CPT Zimmer (n=23) 2. Monoblock Exeter Trauma Stem (n=22), CPT bipolar (n=4), CPT modular (n=27) |

RCT (105) | 100 | ADL (12 months, 78) Delirium (12 months, 105) Mobility (12 months, 78) Mortality (4 and 12 months, 105) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 105) |

| Ravikumar 2000 | 1. Cemented with Howse II 2. Uncemented Austin‐Moore |

RCT (180) | 100 | Mobility (13 years, 32) Mortality (4 and 12 months and 13 years, 180) Unplanned return to theatre (12 months, 180) |

| Ren 2017 | 1. Surgeon's preference 2. Cemented |

RCT (100) | NR | Function (NR, 100) |

| Sharma 2016 | 1. NR 2. NR |

RCT (80) | 100 | Mortality (1 week, 80) |

| Sonaje 2017 | 1. NR 2. NR |

Quasi‐RCT (42) | 100 | Function (24 months, 40) |

| Van den Bekerom 2010 | 1. Cemented; 32 mm diameter modular head 2. Cemented, bipolar |

RCT (281) | 100 | Mortality (12 and 60 months, 252) Unplanned return to theatre (60 months, 252) |

| Xu 2017 | 1. Uncemented prosthesis 2. Bipolar; uncemented |

RCT (76) | NR | Function (60 months, 76) Mortality (60 months, 76) |

ADL: activity of daily living CPCS: collarless, polished, cemented stem CPT: collarless, polished, double‐taper design concept HA: hemiarthroplasty N: total number randomised n: number analysed NR: not reported OGEE: manufacturer's name for implant RCT: randomised controlled trial THA: total hemiarthroplasty

We included three studies with 244 participants that compared different types of THAs. These comparisons were between a single articulation and a dual‐mobility articulation (Griffin 2016; Rashed 2020), and a short stem and standard stem (Kim 2012). We briefly summarise the characteristics of these studies and the outcomes they report that are relevant to this review in Table 10.

7. Implant and study characteristics. THAs versus other THAs.

| Study ID | Type of THA | Study design (N) | Displaced fractures % | Critical review outcomes (time point, n) |