Abstract

Background:

Prescription opioid overdose has increased markedly and is of great concern among injured workers receiving workers’ compensation insurance. Given the association between high daily dose of prescription opioids and negative health outcomes, state workers’ compensation boards have disseminated Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (MEDD) guidelines to discourage high dose opioid prescribing.

Objective:

To evaluate the impact of MEDD guidelines among workers’ compensation claimants on prescribed opioid dose.

Methods:

Workers’ compensation claims data, 2010–2013 from two guideline states and three control states were utilized. The study design was an interrupted time series with comparison states and average monthly MEDD was the primary outcome. Policy variables were specified to allow for both instantaneous and gradual effects and additional stratified analyses examined evaluated the policies separately for individuals with and without acute pain, cancer, and high dose baseline use to determine if policies were being targeted as intended.

Results:

After adjusting for covariates, state fixed-effects, and time trends, policy implementation was associated with a 9.26 mg decrease in MEDD (95% CI: −13.96, −4.56). Decreases in MEDD also became more pronounced over time and were larger in groups targeted by the policies.

Conclusions:

Passage of workers’ compensation MEDD guidelines was associated with decreases in prescribed opioid dose among injured workers. Disseminating MEDD guidelines to doctors who treat workers’ compensation cases may address an important risk factor for opioid-related mortality, while still allowing for autonomy in practice. Further research is needed to determine whether MEDD policies influence prescribing behavior and patient outcomes in other populations.

Introduction

Workers often initiate opioid use following occupational injury and complications of opioid use, such as the development of an opioid use disorder, may delay return to work, increase utilization of medical resources, and result in other adverse outcomes for employees.1,2 Opioid use is very common among injured workers receiving workers’ compensation insurance. In a study of US workers’ compensation claims 2000–2010, around one-third of workers with a shoulder or back injury involving time lost from work received opioids, and nearly half of those patients went on to become long-term opioid users (>3 months of continuous use).3 Furthermore, opioid users receiving workers’ compensation insurance, across all injuries, are more likely to receive high doses and to become chronic users than are opioid users in the general population.4 Of particular concern is the transition from acute opioid use for an injury to chronic opioid use. Workers with chronic joint injuries and permanent partial disability are at elevated risk for chronic opioid use.5 Furthermore, opioids are often used for low-acuity back injuries where their efficacy is questionable.6

MEDD, is a measurement that converts opioid prescriptions to their equivalent dose in morphine and divides the total prescription by days supply (the number of days the prescription is intended to last),7 allowing comparison among different opioid formulations and strengths. MEDD threshold guidelines set an overall dose over which prescribing is not recommended. A number of state-level agencies, insurers, and organizations have promoted these types of policies. Among these organizations are state workers’ compensation organizations including Washington, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and California, which have all passed MEDD threshold guidelines.8 Each of these guidelines discourages prescribing above a certain MEDD threshold, but the content and wording of guidelines vary from state to state. For example, Connecticut recommends that “The total daily dose of opioids should not be increased above 90mg oral MED/day (Morphine Equivalent Dose) unless the patient demonstrates measured improvement in function, pain or work capacity.” Similarly, the Massachusetts guideline states “The total daily dose of opioids should not be increased above 120 mg of oral morphine or its equivalent. In some instances, the patient may benefit from a higher dose if there is documented objective improvement in function and pain, and a lack of significant opioid side effects.”

Despite the proliferation of these guidelines, evaluations of the impact of MEDD guidelines on prescribing practices have been limited to Washington State. Evaluations of Washington’s MEDD threshold guideline in the Medicaid population found a reduction in opioid use from pre- to post- guideline implementation with the greatest reductions occurring among patients receiving over 120 MEDD—the threshold level set by the Washington guideline.9,10 The studies did not make use of comparison states, but did note that the reduction was seen at a time in which opioid prescribing was increasing in the United States, overall. In another study using Washington workers’ compensation claims data, no statistically significant reduction in opioid poisonings and adverse events was observed following the passage of MEDD threshold guidelines, although these events may have been under-reported.11

MEDD threshold guidelines promoted by state workers’ compensation agencies have not been evaluated in other settings and no multi-state evaluations have been conducted. While there has been limited evaluation of opioid dose prescribing guidelines, evaluations of other types of prescribing guidelines have found that adherence to published prescribing guidelines is typically low, even years after they have been published.12–15 However, strategies such as alerting prescribers of guidelines through decision support within an Electronic Health Record (EHR) during relevant patient encounters tend to significantly improve adherence.12–14,16,17 The goal of the present study is to evaluate the impact of two states’ workers’ compensation MEDD threshold guidelines (Massachusetts and Connecticut) on the MEDD of filled prescriptions paid for by workers’ compensation insurance.

Methods

To evaluate the impact of workers’ compensation MEDD threshold guidelines, administrative claims data, 2000–2013, from a large, national workers’ compensation insurer was used. An interrupted time series with comparison group design, which is a special case of a difference in differences analysis, was employed. These data were used previously to evaluate occupational injury clinical practice guidelines.3,18–20 The data included National Drug Codes (NDC), drug quantities, dates of service, International Classification of Disease, Version 9 (ICD9) codes, state, age, sex, and employment status prior to injury.

Study Population

Included in the study were patients age 16–64 with a lost-time injury after January 1, 2000 and at least one valid, active opioid prescription between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2013. Valid opioid prescriptions were defined as having non-missing units and days supply. Units with values of 0 or >1000 and days supply 0 or >180 were considered missing, consistent with prior studies.21,22 Duplicate values (based on NDC, units, and fill date) were deleted. Opioid prescriptions and morphine equivalent conversion factors were identified using a crosswalk file from the Centers for Disease Control.23 Patients were only included who resided in a treatment state (Massachusetts and Connecticut) or control state (Illinois, Indiana, and Pennsylvania). Control states were selected on the basis of not implementing Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs),24 pain clinic laws,25 non-workers’ compensation state-level MEDD policies,26 or passing any other major prescription opioid legislation, as determined through a search of LexisNexis and Westlaw Next during the study period. Control states were also examined to ensure parallel monthly MEDD trends prior to guideline implementation. Treatment states were selected if they enacted a workers’ compensation MEDD guideline, as identified in a previous systematic review of state-level MEDD policies.26 States with monopolistic workers’ compensation, meaning a state-run workers’ compensation program for most workers, were not included as control or treatment states due to limited and non-representative presence in the data, which consisted of claims data from a private insurer. Individuals with missing covariate data (<5%) were also excluded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was MEDD calculated at the person-month level by multiplying quantity, dose, and conversion factor and dividing by days supply, taking into account multiple and overlapping prescriptions (see SAS code and example MEDD calculation, Supplemental Digital Content 1). As the distribution of MEDD was highly skewed right with a small number of individuals receiving very high average doses, the natural log of MEDD was also tested as an outcome. MEDD dichotomized as >120 or ≤120 and >90 or ≤90 were also tested, corresponding to the guideline thresholds for Massachusetts and Connecticut, respectively.

Policy Variables

Policy variables were defined in two ways: First, as a simple pre- and post- indicator for whether or not the policy was in effect during the given month. Second, as a months since policy implementation variable to allow for gradual policy dissemination over time. Massachusetts’ guideline was implemented February 2012 and Connecticut’s was implemented July 2012.

Individual Level Variables

In addition to age, sex, and full-time employment status at the time of injury, a number of derived variables were included in the analysis. These included high baseline opioid use (defined as >90 MEDD and >120 MEDD in at least one month prior to February 2012, which was the first policy implementation date), time since first opioid prescription (to account for within-subject changes in MEDD), six body region Abbreviated Injury Scores (AIS) which were calculated using the nine most commonly occurring ICD9 codes for each patient over the course of their claim using ICDPIC for Stata14.6 Injury Severity Score (ISS), a summary measure that squares and adds the three highest AIS score, also calculated using ICDPIC, was calculated for descriptive purposes. Because ICDPIC does not include ICD9 codes for burns, a separate burn indicator was created defined as ICD9 codes with the first three digits 940–949.27 Indicators for whether or not the patient received an acute pain diagnosis and whether or not the patient had a cancer diagnosis, as defined by Mack et al.21, were also created.

Analyses

Generalized linear mixed models were used with MEDD as the primary outcome and person-month as the unit of analysis. All models included state fixed effects, a linear time trend, and clustering at the individual and state level which accounted for correlated outcomes within individuals and within states. All models included controls for age, sex, six body region AIS, burn indicator, and months since the first opioid prescription. Policy variables tested included both dichotomous and months in effect variables as described in the previous section. All time variables (months since first opioid prescription, months since policy implementation, and the monthly linear time trend) were tested for multicollinearity, defined as variance inflation factors (VIF) >10. Models were stratified by months with no active opioid prescription in the previous month (new prescription months) and months with an opioid prescription in the previous month (continuing prescription months) to determine if the policy had a differential effect in these two groups. Models were stratified by the presence of acute pain diagnosis and by the presence of a cancer diagnosis. The Massachusetts policy is specifically geared towards chronic pain and, while neither the Massachusetts nor the Connecticut policy explicitly excludes cancer patients, MEDD policies are frequently geared towards non-cancer pain.8 It was hypothesized that these policies would have either or no effect or a smaller effect in acute pain and cancer patients than in those with chronic, non-cancer pain. Models were also stratified by high baseline opioid use with larger effects of the policy hypothesized in individuals with high baseline use.

Results

Population characteristics by treatment group (control states, treatment states pre-policy implementation, and treatment states post-policy implementation) are presented in Table 1. The majority of individuals across all groups were male and had at least one acute pain diagnosis. Small magnitude, but statistically significant differences existed between treatment groups with a higher percentage of males in the treatment states (83.0% post-policy and 76.5% pre-policy) as compared to the control states (74.3%) (p<0.001). Individuals in the control states were more likely to be employed full-time prior to injury (92.6% in control states, 88.9% in treatment states pre-policy, and 89.7% in treatment states post-policy, p<0.001) and have an acute pain diagnosis (95.2% in control states, 94.0% in treatment states pre-policy, and 93.1% in treatment states post-policy, p<0.001). Individuals in treatment states were on average older (43.9 (SD 10.7) in control states, 44.1 (SD 10.7) in treatment states pre-policy implementation and 47.0 (SD 9.2) in treatment states post-policy implementation, p<0.001) and had higher Injury Severity Scores (ISS) (3.7 (SD 4.5) in control states, 4.1 (SD 5.5) in treatment states pre-policy and 4.6 (SD 5.9) in treatment states post-policy, p<0.001). A greater proportion of person-months involved high-dose opioid use in treatment states than in control states and the percentage of individuals with high-dose opioid use increased from the pre- to the post-period (15.9% with MEDD >120 in control states, 17.3% in treatment states pre-policy and 23.6% in treatment states post-policy, p<0.001) (Table 2). There was also a higher percentage of new opioid prescription months in control states than in treatment states (10.2% in control states, 8.6% in treatment states pre-policy and 3.6% in treatment states post-policy, p<0.001).

Table 1:

Population Characteristics by Treatment Group, N=6562 People (66,656 Person-Months)

| n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| States With No MEDD Guideline at Any Time | States With MEDD Guideline, Prepassage* | States With MEDD Guideline, Postpassage* | P † | |

| People, N | 4482 | 2034 | 698 | NA |

| State | ||||

| Massachusetts | NA | 1412 (69.4) | 517 (74.1) | NA |

| Connecticut | NA | 622 (30.6) | 181 (25.9) | NA |

| Illinois | 1990 (44.4) | NA | NA | NA |

| Indiana | 549 (12.3) | NA | NA | NA |

| Pennsylvania | 1943 (43.7) | NA | NA | NA |

| Male | 3329 (74.3) | 1555 (76.5) | 579 (83.0) | <0.001 |

| Full-time | 4148 (92.6) | 1809 (88.9) | 626 (89.7) | <0.001 |

| Age (y), Mean (SD) | 43.9 (10.7) | 44.1 (10.7) | 47.0 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Acute pain diagnosis‡ | 4265 (95.2) | 1912 (94.0) | 650 (93.1) | 0.03 |

| ISS, Mean (SD)‡ | 3.7 (4.5) | 4.1 (5.5) | 4.6 (5.9) | <0.001 |

Characteristics as of time of injury unless otherwise indicated.

Individuals in treatment states may be counted in prepolicy period, postpolicy period, or both.

X2 test tor categorical variables and 1-way ANOVA tor continuous variables.

Calculated using diagnoses over the person’s entire claim.

ISS indicates Injury Severity Score; MEDD., Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose.

Table 2:

Person-month Characteristics by Treatment Group, N=66,656 Person-Months (6562 People)

| States With No MEDD Guideline at Any Time | States With MEDD Guideline, Prepassage* | States W ith MEDD Guideline, Postpassage* | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-months, N | 40,149 | 19,457 | 7050 | NA |

| > 120 MEDD | 6374 (15.9) | 3371 (17.3) | 1665 (23.6) | <0.001 |

| > 90 MEDD | 7860 (19.6) | 4264 (21.9) | 2040 (28.9) | <0.001 |

| New opioid prescriptions | 4102 (10.2) | 1663 (8.6) | 252 (3.6) | <0.001 |

Individuals in treatment states may be counted in prepolicy period, postpolicy period, or both.

χ2 test.

MEDD indicates Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose.

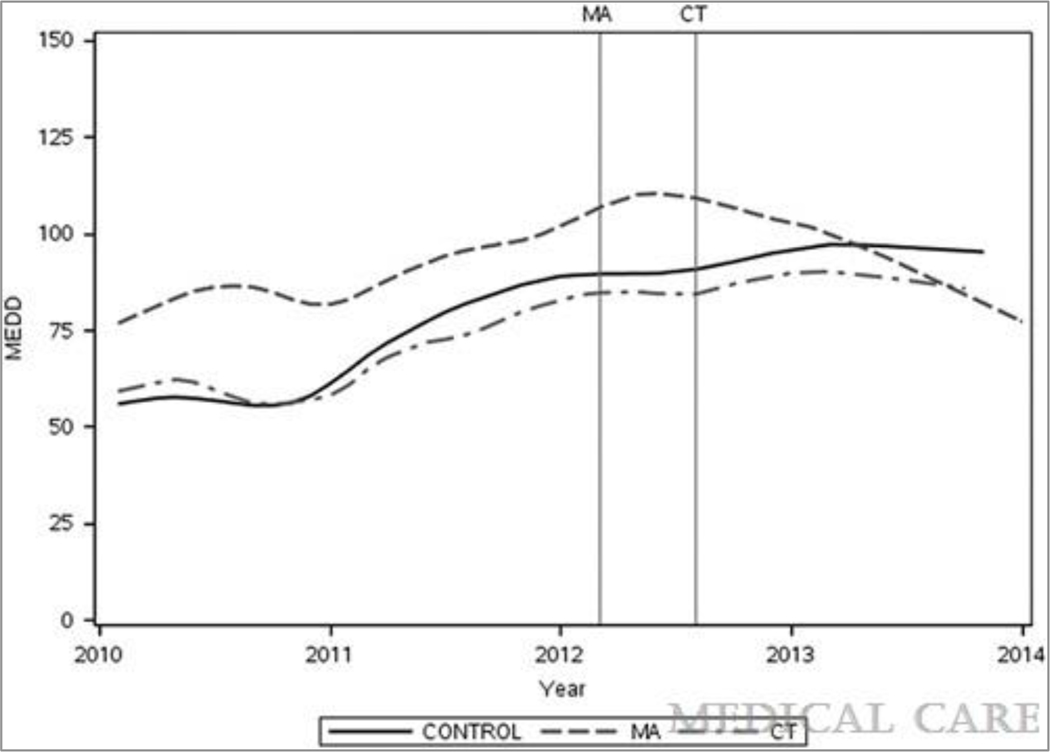

Unadjusted MEDD by state and month are presented in Figure 1. Prior to the first MEDD guideline implementation in Massachusetts, the control and treatment states had roughly parallel trends in monthly MEDD use. Average MEDD increased relatively linearly each month with a higher baseline MEDD in Massachusetts than in Connecticut or the control states. Following the passage of the Massachusetts guideline, average MEDD continued to increase for a couple months before leveling off and finally decreasing. In Connecticut, average MEDD use appears to increase at a slower rate than in the control states following the passage of the Connecticut guideline and begins to level off and decrease slightly in 2013.

Figure 1.

Mean monthly Morphine Equivalent Dose (MEDD) by guideline states Massachusetts (MA) and Connecticut (CT) and control states with loess smoothing (smooth=0.2), vertical lines indicate guideline passage dates

Regression results for the entire population using both dichotomous and months in effect policy definitions are presented in Table 3. After adjusting for covariates, policy implementation (the main independent variable) was associated with a 9.26 mg decrease in MEDD (95% CI: −13.96, −4.56) from the pre- to post- period, relative to control states. This contrasts somewhat from the unadjusted results presented in Table 1 as doses were increasing in control states during this time period and within subject changes tend towards increasing opioid dose over time. Decrease in MEDD also became more pronounced over time. Policy implementation was associated with a 1.87 mg decrease in MEDD for each month since the policy’s implementation (95% CI: −2.37, 1.37, p<0.001). Also of note, MEDD tended to be higher among males, younger individuals, individuals, and individuals who had been on opioids for a longer period of time.

Table 3:

Regression Results, Continuous MEDD Outcome With 2 Policy Variable Definitions, All Patients (N=66,656 Person-Months)

| MEDD Guideline in Effect or Not for Given Month Policy Variable Definition | Months MEDD Guideline in Effect Policy Variable Definition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Variables | Estimate | 95% Cl | P | Estimate | 95% Cl | P |

| Policy variable | −9.26 | −13.96 to −4.56 | <0.001 | −1.87 | −2.37 to −1.37 | <0.001 |

| Head AIS | 0.80 | −0.83 to 2.42 | 0.337 | 0.81 | −0.82 to 2.44 | 0.329 |

| Face AIS | 2.68 | −1.80 to 7.17 | 0.241 | 2.58 | −1.90 to 7.07 | 0.259 |

| Chest AIS | −3.49 | −5.53 to-1.46 | <0.001 | −3.53 | −5.57 to −1.49 | <0.001 |

| Abdomen AIS | 10.80 | 9.03–12.56 | <0.001 | 10.77 | 9.00–12.53 | <0.001 |

| Extremities AIS | 0.51 | −0.65 to 1.67 | 0.386 | 0.49 | −0.67 to 1.65 | 0.411 |

| External AIS | 13.69 | 11.28–16.10 | <0.001 | 13.58 | 11.17–15.99 | <0.001 |

| Burn indicator | −30.66 | −44.29 to −17.04 | <0.001 | −30.52 | −44.13 to −16.90 | <0.001 |

| Age (y) | −0.98 | −1.10 to −0.87 | <0.001 | −0.98 | −1.10 to −0.86 | <0.001 |

| Male | 17.56 | 14.80–20.32 | <0.001 | 17.58 | 14.82–20.34 | <0.001 |

| Months after January 2012 | 0.65 | 0.54–0.77 | <0.001 | 0.73 | 0.62–0.85 | <0.001 |

| Full-time employee | 21.30 | 17.21–25.40 | <0.001 | 21.30 | 17.20–25.40 | <0.001 |

| Connecticut (reference = Pennsylvania) | −13.00 | −17.04 to −8.97 | <0.001 | −12.95 | −16.92 to −8.98 | <0.001 |

| Illinois (reference = Pennsylvania) | −20.27 | −23.27 to −17.27 | <0.001 | −20.26 | −23.25 to −17.26 | <0.001 |

| Indiana (reference = Pennsylvania) | −23.32 | −29.33 to −17.31 | <0.001 | −23.06 | −29.07 to −17.05 | <0.001 |

| Massachusetts (reference = Pennsylvania) | 6.16 | 2.81–9.51 | <0.001 | 7.55 | 4.28–10.81 | <0.001 |

| Months since first opioid rx | 0.73 | 0.68–0.78 | <0.001 | 0.73 | 0.68–0.78 | <0.001 |

AIS indicates Abbreviated Injury Score; Cl, confidence interval; MEDD, Moiphine Equivalent Daily Dose.

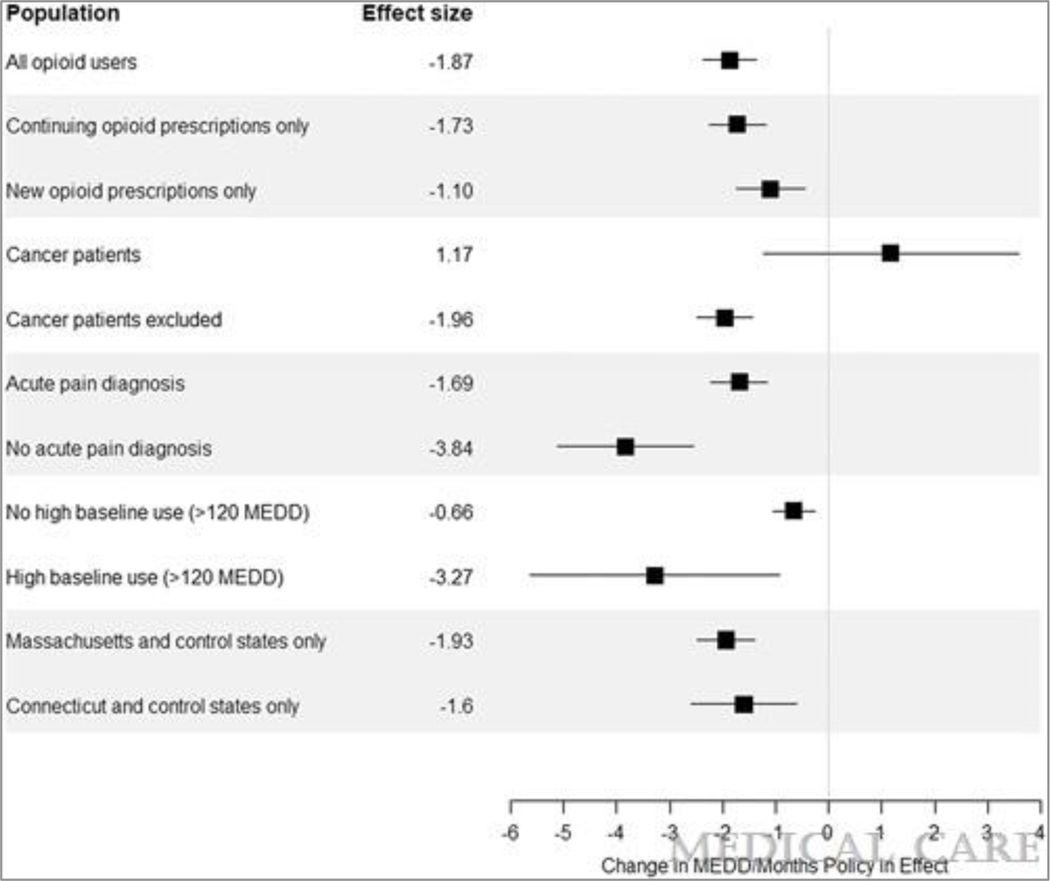

Using the natural log of MEDD and dichotomous MEDD outcome variables did not change the direction or significance of the relationship (Tables 1–3, Supplemental Digital Content 2). Using a dichotomous policy definition and log MEDD, policy implementation was associated with an 11% decrease in MEDD relative to control states (Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2). Individuals in treatment states had 23% lower odds (95% CI: 16% lower, 28% lower, p<0.001) of receiving opioid prescriptions >120 MEDD and 24% lower odds (95% CI: 18% lower, 29% lower, p<0.001) of receiving opioid prescriptions >90 MEDD relative to control states (Tables 2–3, Supplemental Digital Content 2). Stratified analyses are presented in full in Tables 4–13, Supplemental Digital Content 2 and summarized in Figure 2. As hypothesized, the policy was associated with larger decreases in MEDD among individuals without an acute pain diagnosis as compared to with an acute pain diagnosis, among individuals without a cancer diagnosis as compared to with a cancer diagnosis, and among patients with high baseline opioid use as compared to patients with no high baseline opioid use. Continuing opioid prescriptions saw larger decreases than did new opioid prescriptions, consistent with the framing of the guidelines. When state guidelines were examined individually, both the guidelines in Massachusetts and Connecticut were associated with significant decreases in MEDD relative to control states. However, the magnitude of these decreases were larger in Massachusetts than in Connecticut, consistent with the trends observed in the unadjusted results.

Figure 2.

Effect size (change in MEDD per month policy in effect) for clinically relevant subpopulations

Discussion

Overall, the passage of MEDD threshold guidelines was associated with a decrease in the MEDD of filled prescriptions relative to control states. The magnitude of this reduction was greater the more months the policy was in effect. Additionally, there was a larger decrease in MEDD among the groups that the policy was intended to target, namely patients with chronic, non-cancer pain and high baseline use. Importantly, no statistically significant change in MEDD was observed among cancer patients—alleviating a common concern that these types of policies may prevent individuals with cancer from receiving adequate pain treatment. While significant reductions were observed in both states that passed guidelines, larger decreases were observed in Massachusetts than in Connecticut. It is unclear why larger decreases were observed in Massachusetts. Notably, Massachusetts had a higher MEDD threshold than Connecticut. It is possible that dissemination efforts in Massachusetts were more robust and identifying differences in dissemination and influence, perhaps using surveys or qualitative methods, warrants further exploration.

This study has a number of important strengths, namely a large sample size, longitudinal data, and a study design that utilized pre- and post- data from both treatment and control states. The dataset also contained diagnosis codes which allowed controls for injury severity and stratification by clinically important groups. This work also built off previous research that systematically reviewed and categorized state-level MEDD policies.

Notable limitations include a dynamic policy environment in which a number of efforts to curb opioid prescribing are present. While the study carefully selected control states that had not passed major opioid legislation, implemented PDMPs, or implemented other types of MEDD policies at the state-level during the study period, there are still a number of other important considerations. For example, a large private insurer in Massachusetts implemented a comprehensive policy limiting opioid prescriptions through strategies that included prior authorization, quantity limits, and restrictions on opioid dispensing at around the same time as the MEDD guidelines were passed.28 While individuals receiving opioids through workers’ compensation insurance would not have been directly subject to these restrictions, they may have contributed to a more cautious prescribing culture statewide. Efforts to restrict opioid prescribing at the local level were not systematically captured and, if present, may have influenced results. It was also assumed that national-level policy efforts did not differentially influence prescribing by state. As these were state-level policies, we were not examining any efforts of the worker compensation insurer to implement dosing guidance. We assumed that any policy or culture changes on the part of the insurer would not differentially impact treatment and control states, though it is possible that practitioners in certain states may be more receptive to national or insurer level policies. Additionally, the results of this study may not be generalizable to the workers’ compensation population as a whole. As with most claims data research from a single insurer, it is important to note that opioids not paid for by the workers’ compensation insurer were not captured. Study data is also limited to 2010–2013 and several other MEDD policies and opioid prescribing guidelines have proliferated in subsequent years. From 2013–2019, several additional state and national opioid policies have been implemented, notably the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) which implemented a 2016 MEDD guideline cautioning prescribers against raising opioid doses higher than 50 MEDD.29 The study timeframe is a limitation in that the results may not reflect more recent policies, but also is a strength as it allows evaluation of MEDD policies prior the implementation of potentially confounding policies.

A number of recent policies are increasingly emphasizing the importance of other important risk-factors for opioid mortality, such as limiting days supply of new opioid prescriptions to prevent addiction and long-term use, as well as the promotion of alternative non-opioid pain treatment and management.30 Long-term opioid users who are subjected to rapid dose reductions may experience intense withdrawal symptoms and uncontrolled pain.31 Given our finding that individuals on high doses of opioids experienced greater reductions in MEDD following guideline passage, it is important to consider the potential negative impacts of these guidelines on long-term users. There is also some concern that restriction of opioid use among long-term opioid users may lead to increased use of heroin or other illicit drugs, though evidence on this is mixed.32–34 These policy interactions are beyond the scope of the current study, and future research should examine the impact of these guidelines on patient outcomes to determine if reduction of MEDD leads to reductions in overdose or transitions from acute to chronic use.

Overall, this study demonstrates that passage of MEDD guidelines was associated with significant decreases in high dose opioid prescribing among workers’ compensation claimants. Moreover, the most significant decreases were observed among individuals whom the guidelines were intended to target: namely patients with chronic, non-cancer pain. MEDD guidelines should be considered as a tool by policymakers to reduce high dose opioid prescribing, which is a key risk factor for opioid overdose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge Caleb Alexander, Keshia Pollack Porter, Colleen Barry, and Andrea Gielen for their feedback on the manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Grant No.: R36 HS25557

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Franklin GM, Stover BD, Turner JA, Fulton-Kehoe D, Wickizer TM. Early opioid prescription and subsequent disability among workers with back injuries: The Disability Risk Identification Study Cohort. Spine 2008;33(2):199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster BS, Verma SK, Gatchel RJ. Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent surgery and late opioid use. Spine 2007;32(19):2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heins SE, Feldman DR, Bodycombe D, Wegener ST, Castillo RC. Early opioid prescription and risk of long-term opioid use among US workers with back and shoulder injuries: a retrospective cohort study. Inj Prev J Int Soc Child Adolesc Inj Prev 2016. Jun;22(3):211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraut A, Shafer LA, Raymond CB. Proportion of opioid use due to compensated workers’ compensation claims in Manitoba, Canada. Am J Ind Med 2015;58(1):33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hara NN, Pollak AN, Welsh CJ, et al. Factors Associated with Persistent Opioid Use Among Injured Workers’ Compensation Claimants. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1(6):e184050–e184050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swedlow A, Ireland J, Johnson G. Prescribing Patterns of Schedule II Opioids in California Workers’ Compensation. Research Update. California Workers’ Compensation Institute. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ripamonti C, Groff L, Brunelli C, Polastri D, Stavrakis A, De Conno F. Switching from morphine to oral methadone in treating cancer pain: what is the equianalgesic dose ratio? J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998;16(10):3216–3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heins S. Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose Policies. Policy Surveillance Program. June 1, 2017. Available at: http://lawatlas.org/datasets/morphine-equivalent-daily-dose-medd-policies. Accessed August 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulton-Kehoe D, Sullivan MD, Turner JA, et al. Opioid poisonings in Washington State Medicaid: Trends, dosing, and guidelines. Med Care 2015;53(8):679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan MD, Bauer AM, Fulton-Kehoe D, et al. Trends in opioid dosing among of Washington state Medicaid patients before and after opioid dosing guideline implementation. J Pain 2016. May;17(5):561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fulton-Kehoe D, Garg RK, Turner JA, et al. Opioid poisonings and opioid adverse effects in workers in Washington state. Am J Ind Med 2013;56(12):1452–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kooij FO, Klok T, Hollmann MW, Kal JE. Decision support increases guideline adherence for prescribing postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. Anesth Analg 2008;106(3):893–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tooher R, Middleton P, Pham C, et al. A systematic review of strategies to improve prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospitals. Ann Surg 2005;241(3):397–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham NS, El–Serag HB, Johnson ML, et al. National adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the prescription of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol 2005;129(4):1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinmann S, Janssen B, Gaebel W. Guideline adherence in medication management of psychotic disorders: An observational multisite hospital study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112(1):18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: A systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ 2005;330(7494):765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eslami S, de Keizer NF, Abu-Hanna A. The impact of computerized physician medication order entry in hospitalized patients—A systematic review. Int J Med Inf 2008;77(6):365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts ET, DuGoff EH, Heins SE, et al. Evaluating Clinical Practice Guidelines Based on Their Association with Return to Work in Administrative Claims Data. Health Serv Res. 2015;(Journal Article). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trujillo AJ, Heins SE, Anderson GF, Castillo RC. Geographic variability of adherence to occupational injury treatment guidelines. J Occup Environ Med Am Coll Occup Environ Med 2014;56(12):1308–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buttorff C, Trujillo AJ, Castillo R, Vecino-Ortiz AI, Anderson GF. The impact of practice guidelines on opioid utilization for injured workers. Am J Ind Med 2017;60(12):1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mack KA, Zhang K, Paulozzi L, Jones C. Prescription practices involving opioid analgesics among Americans with Medicaid, 2010. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2015;26(1):182–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heins SE, Sorbero MJ, Jones CM, Dick AW, Stein BD. High-Risk prescribing to Medicaid enrollees receiving opioid analgesics: Individual- and county-level factors. Subst Use Misuse 2018;53(10):1591–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data resources: Analyzing prescription data and morphine milligram equivalents. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/resources/data.html. Published September 29, 2017. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- 24.PDMP Training and Technical Assistance Center. PDMP maps and tables. Available at: http://www.pdmpassist.org/content/pdmp-maps-and-tables. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 25.Legal Science. Pain management clinic laws. Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System. http://pdaps.org/datasets/pain-management-clinic-laws. Published June 1, 2018. Accessed July 12, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heins SE, Frey KP, Alexander GC, Castillo RC. Reducing high-dose opioid prescribing: State-level morphine equivalent daily dose policies, 2007–2017. Pain Med, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark DE, Osler TM, Hahn DR. ICDPIC: Stata module to provide methods for translating International Classification of Diseases (Ninth Revision) diagnosis codes into standard injury categories and/or scores; Statistical Software Components S457028, Boston College Department of Economics, revised 29 Oct 2010. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia MM, Angelini MC, Thomas T, Lenz K, Jeffrey P. Implementation of an opioid management initiative by a state medicaid program. J Manag Care Pharm 2014;20(5):447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016. Apr 19;315(15):1624–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Service U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2016;30(2):138–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank JW, Levy C, Matlock DD, et al. Patients’ perspectives on tapering of chronic opioid therapy: A qualitative study. Pain Med 2016;17(10):1838–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Richey M, McGinty EE, Stuart EA, Barry CL, Webster DW. Opioid overdose deaths and Florida’s crackdown on pill mills. Am J Public Health 2016. Feb;106(2):291–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dasgupta N, Creppage K, Austin A, Ringwalt C, Sanford C, Proescholdbell SK. Observed transition from opioid analgesic deaths towards heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014. Dec 1;145:238–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alpert A, Powell D, Pacula RL. Supply-Side Drug Policy in the Presence of Substitutes: Evidence from the Introduction of Abuse-Deterrent Opioids. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.