Abstract

Background:

The obesity epidemic continues to be a major public health concern. Although exercise is the most common weight loss recommendation, weight loss outcomes from an exercise program are often suboptimal. The human body compensates for a large percentage of the energy expended through exercise to maintain energy homeostasis and body weight. Increases in energy intake appear to be the most impactful compensatory behavior. Research on the mechanisms driving this behavior have not been fully elucidated.

Purpose:

To determine if exercise influences the attentional processing towards food cues (attentional bias) and inhibitory control for food cues among individuals classified as overweight to obese who do not exercise.

Methods:

Thirty adults classified as overweight to obese participated in a counterbalanced, crossover trial featuring two assessment visits on separate days separated by at least one week. Attentional bias and inhibitory control towards food cues was assessed prior to and after a bout of exercise where participants expended 500 kcal (one assessment visit) and before and after a 60-minute bout of watching television (second assessment visit). Attentional bias was conceptualized as the percentage of time fixated on food cues when both food and neutral (non-food) cues were presented during a food-specific dot-probe task. Inhibitory control, specifically motor impulsivity, was assessed as percentage of inhibitory failures during a food-specific Go/NoGo task.

Results:

A significant condition by time effect was observed for attentional bias towards food cues, independent of hunger, whereas attentional bias towards food cues was increased pre-post exercise but not after watching TV. Inhibitory control was not affected by exercise or related to attentional bias for food cues.

Conclusions:

An acute bout of exercise increased attentional bias for food cues, pointing to a mechanism that may contribute to the weight loss resistance observed with exercise. Future trials are needed to evaluate attentional bias towards food cues over a longitudinal exercise intervention.

Keywords: Attentional Bias, Obesity, Exercise, Weight loss, Inhibitory Control, Food Cues

1. Introduction

Obesity is a well-documented risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and certain cancers [1–5] and tightly linked to all-cause mortality [6]. Weight loss and weight loss maintenance research continues to be at the forefront for chronic disease prevention and control [7–9]. Despite these efforts, over 70% of the US adult population is overweight or obese [7, 8]. This suggests most individuals are not meeting their weight loss goals and underscores the need for novel obesity treatment interventions. The first step in developing novel and efficacious weight loss treatments is to understand the etiologies behind why weight loss interventions do not produce their desired results.

Exercise is the most common weight loss strategy with a prevalence rate of 65% among those attempting to decrease body weight [10]. Exercise is also one of the primary recommendations of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) and a key component to the classic Look AHEAD trial primarily due to the role exercise is believed to play in weight loss and weight loss maintenance [11, 12]. However, reductions in body weight, specifically fat mass, from exercise training are often less than expected due to compensatory mechanisms that resist maintenance of the energy deficit required for weight loss [13–15]. Some have reported greater amounts of exercise can evoke a proportionally greater compensatory response, potentially why exercise interventions with large differences in daily and weekly exercise energy expenditures can result in similar weight loss [16–19]. Others have determined this compensatory response to equal roughly 1,000 kcal per week regardless of the magnitude of energy expended [20, 21]. Individual differences in the compensatory response to exercise is well documented and likely plays an important role in these contrasting results [22]. In either case, this compensatory response determines the magnitude of weight loss from an exercise intervention.

The compensatory response to an energy deficit is an evolutionarily conserved trait in place to defend against a negative energy balance, formerly seen as a threat to survival [15]. In our current obesogenic society, however, desired weight loss requires a negative energy balance and is opposed by the compensatory response to this energy deficit. An energy deficit can be negated by either increasing energy intake or reducing energy expenditure (conserving energy). Decreases in non-exercise physical activity is one way individuals can conserve energy and thus resist a negative energy balance [15]. Although we have determined, via accelerometry, non-exercise physical activity is not significantly changed when individuals classified as overweight to obese start a new exercise program [20, 21]. Obligatory reductions in metabolic energy expenditure are another source of energy compensation, with these reductions accounting for approximately 120 kcal/day through mechanisms related to thyroid function, skeletal muscle glucose oxidation, and sympathetic nervous system activity [23–27]. The most impactful compensatory response working to resist an energy deficit is increases in energy intake, as the rate of energy intake exceeds the rate of energy expenditure and capable of accounting for considerably more than 120 kcal/day [13–15]. Determining the underlying mechanisms responsible for exercise-induced increases in energy intake is a necessary step towards improving weight loss outcomes.

An often-studied and easily assumed mechanism responsible for greater energy intake with exercise is increased hunger, assessed by hormonal mediators of appetite, lab-based food intake, and hunger/satiety scales [28–32]. In particular, elevated concentrations of the orexigenic hormone ghrelin [28, 33] and reductions in satiety-inducing signals such as peptide YY (PYY), glucagon-like peptide one (GLP-1), pancreatic polypeptide (PP), cholecystokinin (CCK), and leptin may all be altered to promote greater energy intake when exercising [30–32]. However, single bouts of exercise typically do not result in the expected orexigenic changes in appetite, food intake, and appetite regulating hormones [19, 34–36]. Others have demonstrated the opposite, where greater perceptions of fullness persist 24 hours after exercise [37], and long-term exercise improves the satiety response to a meal [31, 38]. We have specifically demonstrated changes in fasting levels of hunger hormones do not predict energy compensation [20], and post-prandial decreases in satiety inducing hormone Leptin predicts less energy compensation [21]. It therefore appears exercise has a sensitizing action on leptin, improving its function to exert its physiological effects at lower levels, similar to the benefits of improving insulin sensitivity. These findings indicate biological processes governing hunger do not fully explain the compensatory response observed in exercising humans, pointing to other processes that require additional exploration [20, 21].

Empirical hypotheses postulate individuals who exercise for weight loss have distorted portion control, seek rewards from exercising in the form of food, and derive greater pleasure from high-fat, high-sugar, energy-dense foods, all of which may be independent of hunger [15, 39]. This heightened awareness and increased responsiveness towards food may be explained by a heightened attentional bias, a measure of the tendency to automatically devote attention to specific stimuli [40]. Attentional bias towards food cues is greater among individuals classified as obese and predicts over consumption of energy-dense palatable foods [41–44]. Impulse control is a multi-faceted construct with various laboratory tasks developed to study different aspects [45, 46]. The present study specifically focused on participants’ ability to suppress pre-potent responses to rewarding cues (motor impulsivity), traditionally measured using Stop Signal and Go/No-Go tasks [46–51]. Consistent with our prior studies, we broadly refer to motor impulsivity as inhibitory control in the present manuscript. Inhibitory control is indeed an important aspect influencing energy intake whereas a heightened awareness/attentional bias towards food may not lead to overeating in those with greater inhibitory control [52]. On the other hand, individuals with poor inhibitory control are at a greater susceptibility to food’s rewarding effects, manifesting as greater energy intake and weight gain [44, 53]. Determining the involvement of these processes in the compensatory response to exercise could guide the development of novel interventions to improve the efficacy of exercise for weight loss interventions. The present study hypothesized an acute bout of exercise would increase attentional bias towards food cues and impair inhibitory control in a sample of individuals classified as overweight to obese.

2. Materials and Methods

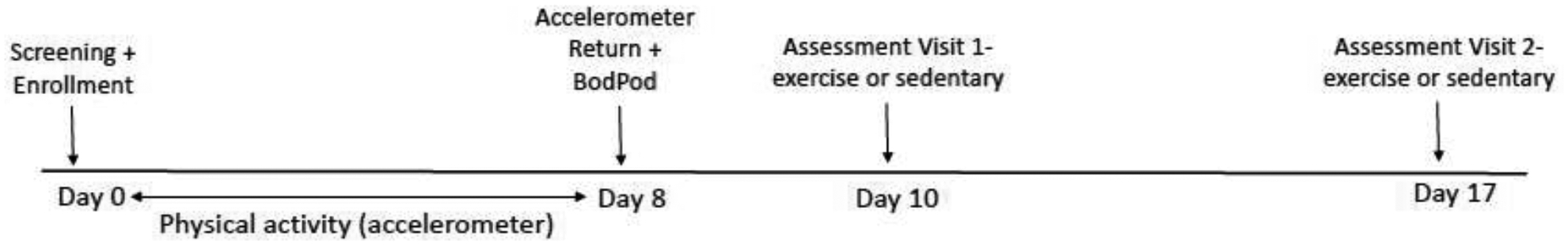

A counterbalanced cross-over design was employed after two initial visits where participants were enrolled and assessed for physical activity and body composition (figure one). The two assessment visits that followed were counterbalanced, one exercise and one sedentary visit, at least one week apart, at the same time of day. Participants completed assessments for attentional bias towards food cues prior to and 15 minutes after a bout of exercise where they expended an estimated 500 kcal (exercise visits) and prior to and 15 minutes after a 60-minute bout of television watching (sedentary visit).

Figure 1:

Study Flow

Recruitment occurred from May to October 2021 in the greater Lexington KY metropolitan area. Participants were a sample who responded to recruitment media (fliers, online advertisements) directed by the University of Kentucky Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS). All participants were overweight to obese (BMI 25–45), non-smoking, had no contraindications to exercise participation, free of chronic diseases (such as diabetes or heart disease) and not currently engaging in exercise or a weight loss diet.

Both assessment visits were performed in the afternoon on the same day of the week, at least one week apart. Participants were 3–5 hours post-prandial and energy intake for the day of each assessment was matched. Participants recorded the foods and beverages they consumed starting the morning of the day of their first assessment up to their visit. Participants were then instructed to replicate these dietary behaviors on the day of their second assessment visit. Participants provided researchers a second food record for their second assessment day to be verified against their first food record. To make the replication of dietary behaviors more natural, assessment visits were scheduled on typical days (not vacations or weekends) where participants followed a usual routine.

Acute Bout of Exercise:

During the exercise assessment visit, participants engaged in exercise on an elliptical ergometer (Octane Fitness ZR8) until they expended an estimated 500 kilocalories (kcal) under supervision of a researcher in the laboratory. Participants were provided a Polar A-300 heart rate monitor with smart-cal™ technology that factors the individual’s sex, age, weight, training status and heart rate to produce an estimate of total energy (in kcal) expended during the exercise session, with energy expended displayed in real-time. Exercise intensity was self-selected, although participants were advised an intensity of 65% heart rate reserve (HRR) is commonly prescribed for sedentary individuals beginning an exercise program [54]. Participants were provided 0.5 l of water during the exercise bout. After expending 500 kcal, participants took a 15-minute rest before performing assessments for attentional bias and inhibitory control towards food cues. Participants also completed a hunger scale where they rated how hungry they felt immediately prior to completing the tasks both before (pre) and after (post) exercise. Standardizing the amount of energy expended during the exercise session was preferred over standardizing the amount of time participants exercised, which would have resulted in different exercise-induced energy deficits across participants, likely influencing the compensatory response and attentional bias towards food cues.

Bout of Sedentary behavior:

Similar to the acute bout of exercise, participants completed assessments for hunger, attentional bias and inhibitory control before and after engaging in 60 minutes of television watching without advertisements (Netflix). Participants selected the program they wished to watch on a big screen TV while relaxing in a recliner. The only stipulation was participants were not allowed to select cooking or food-related programs as this may have influenced their motivational drive to eat.

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Height and Weight

Height was measured in triplicate to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (Seca; Chino, CA). Body weight was measured using a calibrated digital scale connected to the BodPod (Cosmed, USA) to the nearest 0.01 kg. Measures were completed with participants wearing spandex shorts and sports bra (females) or no shirt (males) as required for the BodPod assessment (below). BMI was calculated during the screening and enrollment visit to ensure participants qualified for the study.

2.1.2. Body Composition

Body fat and fat-free mass (kg) was determined via air displacement plethysmography (BodPod, Cosmed USA) and percent body fat calculated. Participants were assessed in the fasted condition at a separate visit prior to completing the two assessment visits (figure one). The BodPod is a reliable and valid assessment tool for body composition in adults, offering a quick and non-invasive assessment of body composition [55]. The Siri or Schutte density model was used, depending on race, to convert body density to percent body fat [56, 57]. Thoracic gas volume was measured according to manufacture recommendations.

2.1.3. Physical activity

To ensure participants were adequately sedentary (defined as not meeting Vigorous physical activity [VPA] guidelines) participants were provided an ActiGraph accelerometer (GT3X model, Pensacola Fla) during their screening and enrollment visit and were instructed to wear it during all awake hours except for swimming or bathing over the following seven days. The accelerometer was collected at a second visit and analyzed to ensure the participant wore it for seven days and that they did not meet VPA guidelines. If the participant did not wear it for seven days, they were given the accelerometer back and this visit was rescheduled. If participants met the VPA guidelines (90+ minutes per week) they would be disqualified from the study. No participants were disqualified from this study based on this requirement. VPA was assessed in favor of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) as the VPA measure is more representative of exercise behavior (planned, structured physical activity performed with the goal of increasing fitness) where as MVPA would include non-exercise activities that included walking [58].

2.1.4. Attentional Bias

Attentional bias for food cues was assessed by the visual probe procedure adapted for food cues [59–61]. Images of highly reinforcing, energy dense foods were matched with neutral images (non-food-related) and presented on a computer screen, one pair at a time. Ten image pairs were presented twice, once with the food image on the left and once with the food image on the right. An additional ten pairs of only neutral images were presented twice. Image pairs were matched for size, color and complexity, and presented in random order. Images were presented for 3,000 ms, after which, a visual probe appeared on either side of the screen in place of one of the previously presented images. Participants responded as quickly as possible to indicate which side the probe appeared by pressing a corresponding computer key. Fixation time (amount of time looking at food and neutral images) was measured by an eye-tracking device (Tobii Pro Fusion 2500, Reston, VA) [59]. Percentage of time fixated on the food image was the primary outcome of interest calculated as: amount of time looking at the food image/ (amount of time looking at neutral image + amount of time looking at food image)*100.

2.1.5. Inhibitory control for food cues

Inhibitory control for food cues was assessed via a food-specific go/no-go task [47], where participants are required to respond to food-related images or neutral (non-food) images. Food-related images included highly rewarding, energy-dense foods such as desserts, candy, or high-fat main entrees such as cheese burgers or other fried foods. Neutral images included those not associated with eating such as office supplies or furniture. After the cue image was presented, it turned either solid green (go) or blue (no-go). All participants were assigned to the food go condition, where 80% of responses following food cues was the “go” response [51, 62]. Participants were instructed to respond by pressing a keyboard button when the green target appeared and withhold responding when the blue target appeared. Failing to withhold responding (blue) to a food-related image is indicative of poor inhibitory control for food cues [51]. The final outcome assessed was percentage of inhibitory failures, or “false alarms” following a food cue (responding when presented with a blue cue following a food image).

2.1.6. Hunger and Satiety

Visual analog scales (VAS) were completed to assess hunger at the beginning of each assessment visit and immediately after the bout of exercise or sedentary behavior (prior to all attentional bias attentional bias and inhibitory control assessments). Participants were asked “how hungry do you feel right now”, on a computer program where they were instructed to drag a bar along a line that ranged from “not hungry at all” to “extremely hungry”. Hunger scores were used as covariates in statistical models. To ensure participants were not more attentive towards food cues just because they were hungrier.

2.2. Analytic Plan and Power Considerations

Independent sample T-tests were used to test for differences in demographics, physical activity behaviors, and specifics of the exercise bout (duration, intensity) between males and females. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess interactions between condition (exercise vs. sedentary) and time (pre vs. post) for attentional bias and inhibitory control outcomes. Bivariate correlations were performed between outcomes measures and participant characteristics. Mediation analysis was performed to assess the mediating effect of inhibitory control on the relationships between exercise and attentional bias and the effects of inhibitory control on the relationship between time and attentional bias in the exercise condition. Linear regression was used to determine predictors of attentional bias outcomes with special interest if hunger scores influenced attentional bias. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 28 (IBM Corp.).

A previous study informed our sample size calculations [63]. They reported an effect size of 0.33 for the interaction between condition and time based on 58 study participants. We estimated that for a within-subject design, with a power of 0.80, and alpha of 0.05, a sample size of at least 30 per group would be needed to detect an interaction effect of 0.53 or larger.

3. Results

A total of 30 participants (14 female) aged 32.9 years with a BMI of 32.7 (mean ± SD) completed the study and were compensated $200. Thirty one (31) participants were originally enrolled with one male dropping out prior to either assessment visit. Table 1 details anthropomorphic data and habitual physical activity behaviors of the study participants. Females had greater percentage of body fat but there were no other differences. As designed, no participant met the physical activity guidelines for VPA.

Table 1:

Baseline demographic measures of study participants

| Male (n=16) | Female (n=14) | All (n=30) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.1 ± 6.1 | 35.0 ± 8.8 | 32.9 ± 7.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.7 ± 4.9 | 33.7 ± 5.1 | 32.7 ± 5.2 |

| % body fat* | 34.6 ± 6.9 | 43.3 ± 6.3 | 38.5 ± 8.0 |

| VPA | 2.9 ± 9.4 | 7.5 ± 17.2 | 5.1 ± 13.7 |

Data presented as means ± SD

Significant difference between sex (P≤0.05)

VPA: vigorous and very vigorous physical activity, 7-day total from accelerometer

Table 2 details the bout of self-selected intensity exercise participants performed on the assessment visit that featured exercise. Females exercised longer than males due to differences in the rate of energy expenditure (requiring more time to expend 500 kcal) which is largely driven by body mass and was calculated by the Polar A-300 fitness watch. There were no differences in exercise intensity (% of time exercising at heart rate zone 3–5) or total kcal expended.

Table 2:

Time and energy expenditure (Kcal) of the acute bout of exercise among study participants.

| Male (n=16) | Female (n=14) | All (n=30) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total time (minutes)* | 36.7 ± 4.1 | 53.6 ± 8.2 | 46.38 ± 5.2 |

| Zone 3–4 time (minutes) | 30.1 ± 1.1 | 34.8 ± 6.79 | 33.1 ± 3.9 |

| Kcal | 506.5 ± 1.5 | 498.9 ± 14.1 | 502.4 ± 7.6 |

Data presented as mean ± SE

Significant difference between sex (P≤0.05)

Zone 3–4: refers to heart rate reserve zones 3–4 (70–100% of maximal heart rate reserve).

Kcal: Amount of energy (in kcal) expended during the exercise bout (instructed to stop after reaching 500 kcal)

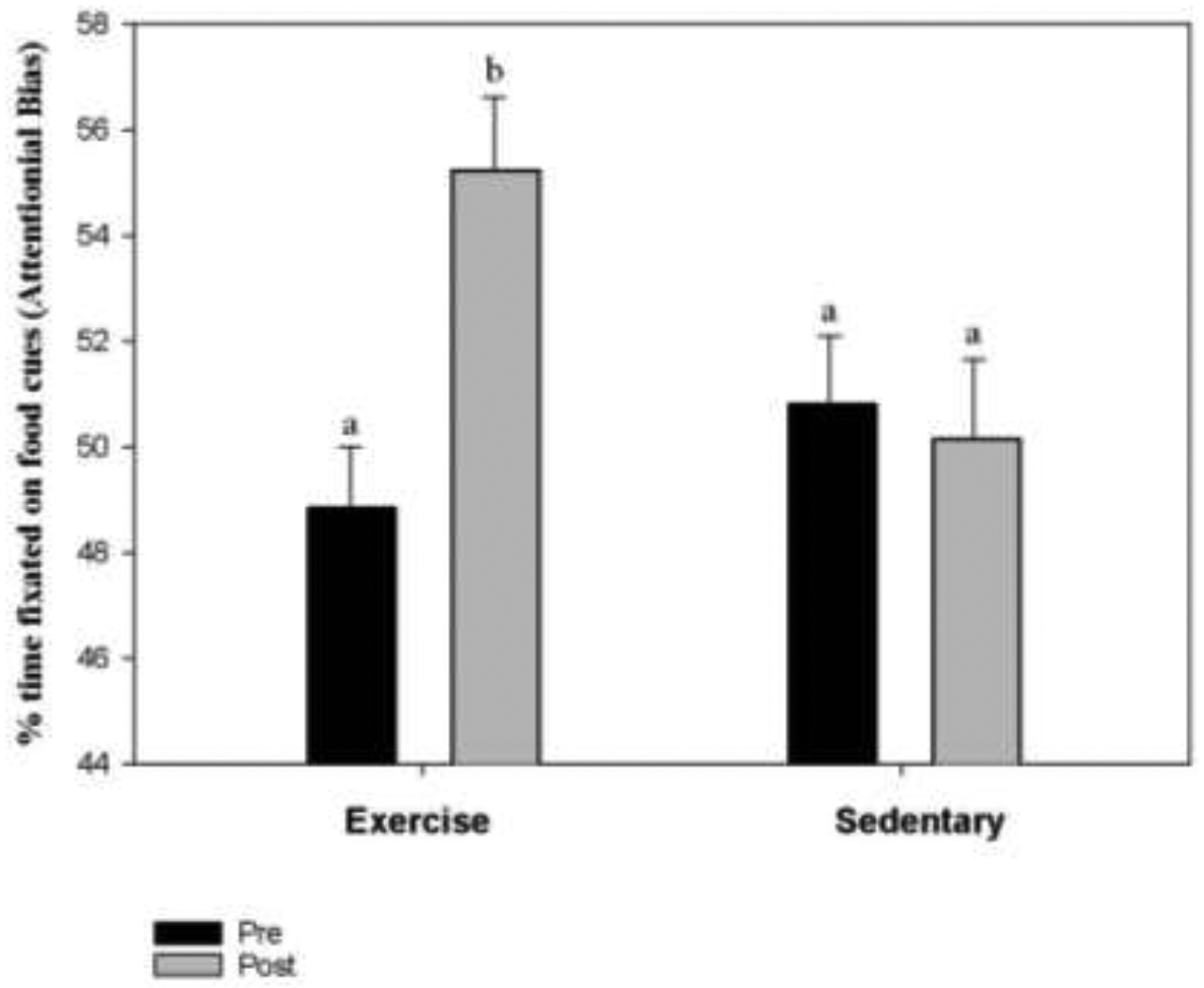

As shown in Figure 2, a significant interaction between condition (exercise vs sedentary) and time (pre vs post) was observed for attentional bias. The percentage of time fixated on food cues increased from 48.85% pre to 55.24% post in the exercise condition, while remaining rather consistent in the sedentary condition at 50.81% pre to 50.15% post.

Figure 2:

A significant time (pre vs. post) by condition (exercise vs sedentary) interaction was observed for Attentional Bias scores (percentage of time fixated on food cues) (P=0.008). Attentional bias significantly increased pre to post exercise bout where participants expended 500 kcal while no significant changes were observed between pre to post sedentary activity (watching TV for 60 minutes).

*similar letters indicate similar attentional bias scores (percent fixation time)

Condition by time effect size (d)= 0.48.

Inhibitory Control results, expressed as percentage of inhibitory fails when presented with a food cue followed by the stop signal, are presented in Table 3. There was no condition or time effect with or without sex included as a covariate.

Table 3:

No significant condition, time, or condition by time effects for inhibitory control measured as percentage of inhibitory fails to the stop signal following a food cue.

| Pre (n=30) | Post (n=30) | Total (n=60) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | 8.67 ± 2.0 | 11.73 ± 2.8 | 10.20 ± 1.72 |

| Sedentary | 10.40 ± 2.4 | 13.87 ± 2.90 | 12.13 ± 1.9 |

| Total | 9.53 ± 1.58 | 12.80 ± 2.05 |

Condition by time effect size (d)=−0.032.

No Correlations were observed between attentional bias and inhibitory control (r=−0.03, p=0.75). Neither attentional bias nor inhibitory control were correlated with hunger (r=0.13 and −0.12, respectively, both p>0.2). Sex was correlated with inhibitory control (r=−0.2, p=0.03), while T tests confirmed females had greater inhibitory control than males (p=0.03). Sex was therefore controlled for in assessing changes in inhibitory control, but did not change results depicted in Table 3. Mediation analyses were performed to determine if inhibitory control mediates the effect exercise has on attentional bias for food cues and if inhibitory control mediates the effect time has on attentional bias for food cues when limiting our analysis to the exercise condition. Neither scenario revealed significant mediating effects, with and without controlling for sex (all p>0.3). To further illustrate hunger did not influence attentional bias, Table 4 presents the linear regression model (full and reduced) demonstrating only BMI was a significant independent predictor of attentional bias when all time points were included. There were no significant predictors of attentional bias when only the post-exercise time point was included or pre to post exercise change in attentional bias.

Table 4:

Quantile regression models predicting attentional bias at all-time points among overweight to obese, sedentary participants.

| Effect | β | SE | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full model | |||

| Intercept | 66.13 | 8.21 | 0.00 |

| Inhibitory Control | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.45 |

| BMI | −0.63 | 0.24 | <0.01 |

| Hunger1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.44 |

| Sex | 3.68 | 2.53 | 0.15 |

| Reduced model | |||

| Intercept | 75.88 | 7.67 | 0.00 |

| BMI | −0.75 | 0.23 | <0.01 |

Hunger scores were self-reported on a 0–100 scale and were taken prior to each Attentional bias and inhibitory control assessments

4. Discussion

The primary findings of the present study are: 1) a large dose of acute exercise results in a shift in attentional processing towards food cues among individuals classified as overweight to obese who do not exercise; 2) inhibitory control is not differentially altered by exercise or sedentary activity in this population; and 3) hunger did not influence attentional bias or inhibitory control for food cues. Below we discuss these findings in the context of the existing literature.

There is a dearth of literature investigating effects of exercise on attentional bias for food cues. To our knowledge, only one such study has been published, which investigated if a short bout of walking could help alleviate chocolate cravings [63]. This study recruited habitual chocolate consumers and deprived them of chocolate. Attentional bias towards chocolate was assessed prior to and after a 15-minute walk. This study demonstrated attentional bias for chocolate decreases after a 15-minute bout of walking, concluding a short walk “took participants’ minds off their cravings” [63]. Since this study was not centered on obesity, the bout of walking was not at the level (intensity or duration) needed to produce sufficient weight loss [20, 21]. Further, the participants in this study were in a state of deprivation and had elevated attentional bias for the stimuli prior to the bout of walking. These factors make it difficult to compare to the results of the present study.

Research investigating the activation of brain regions involved in attentional processing of food images through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or electroencephalography (EEG) have shown decreases in these regions after acute exercise [64–67]. This is at odds with the current findings that exercise increases attentional bias for food cues, indicating other neurocognitive aspects may be in play. Alternatively, children appear to display increased activation of neural activity when presented energy dense foods after exercise compared to low energy-dense foods [68]. Future studies may further investigate this interaction by also assessing the effects of exercise on attentional bias to food cues in children.

Greater energy intake and weight status is often a product of the interaction between inhibitory control and attentional bias, as overeating occurs when the motivational wanting of food exceeds one’s capacity for inhibitory control for eating. As such, a heightened attentional processing towards food may not lead to overeating in those with greater inhibitory control [69, 70]. Conversely, poor inhibitory control strengthens the positive relationship between food’s reinforcing properties and energy intake [69, 71, 72]. Indeed, individuals classified as overweight or obese have poor inhibitory control compared to those classified as normal weight [44, 53, 73–75].

The present study failed to demonstrate exercise influences inhibitory control or had any relationship with attentional bias. Others have demonstrated that exercise improves cognitive function for food-related tasks believed to be related to inhibitory control [76, 77]. These studies utilized a Stroop Task, while the present study specifically assessed motor impulsivity towards food cues i.e. the difficulty suppressing pre-potent responses via a Go/NoGo task [46–51, 78–82]. These prior studies were also performed in children, who likely respond differently to exercise than a sedentary adult classified as overweight or obese. The concept of exercise improving cognitive performance is not new [83–86], although less is known how exercise may affect the ability of an individual classified as overweight or obese to inhibit responding towards food cues. Our results indicate that acute exercise influences attentional bias towards food cues while inhibitory control remains consistent. We also demonstrate inhibitory control and attentional bias for food cues are not related (correlates or mediators) in the context of the present study. Since the present trial did not assess food intake nor was it designed to evaluate weight loss, longitudinal studies are needed to further explore these relationships.

Sex differences in exercise induced energy intake have been reported previously, indicating females are at greater risk for increasing their energy intake in response to exercise when compared to males [87–89]. While we have failed to demonstrate a sex effect in the overall compensatory response [20, 21], others have suggested females may compensate for an exercise-induced energy deficit over the longer term in order to preserve greater body fat stores compared to males [90]. Our sample, which was rather evenly split between male and females, did not detect a sex effect for attentional bias outcomes after exercise nor did sex predict attentional bias when all timepoints were considered. Females did, however, have a greater inhibitory control for food cues than males (all time points considered). Although when including sex as a covariate, there were still no condition or time effects for inhibitory control. Furthermore, the consensus of evidence demonstrates that appetite and appetite-regulating hormones are not differently altered by exercise between males and females [91, 92]. Although future studies specifically powered to detect sex differences in exercise-induced energy compensation and attentional bias are still needed, other behavioral or biological mechanisms appear to be in play to further promote energy intake in females when exercising.

Our linear regression (Table 4) also demonstrated BMI is a significant predictor of attentional bias for food cues, but in the opposite direction expected. Obese individuals have shown greater attentional bias for food cues [41–44], while our regression analysis revealed BMI is a negative predictor of attentional bias. However, this finding must be viewed with caution. There were no differences in attentional bias towards food cues when dividing the participants into two groups based on weight status (obese, BMI≥30 vs. overweight BMI 25–24.9). This is likely due to 22 out of the 30 participants having a BMI ≥ 30, with a very narrow spread of BMIs across all participants (SE=0.95). An additional group of participants with BMI <25 is needed to appropriately assess the relationship between BMI and attentional bias, which has been carried out previously [43]. For this reason, we did not include BMI as a covariate when assessing attentional bias outcomes. The primary purpose of this regression analysis was to determine if hunger scores predicted attentional bias when all timepoints were considered.

This study is not without limitations. We did not assess energy intake for the remainder of the day or the following day, so we do not know if these exercise-induced increases in attentional bias were correlated with greater energy intake. An alternative design would be to measure ad libitum energy intake in the lab after completion of the exercise and control condition. However, this assessment, typically employing buffet-style meals to allow for the selection of different foods, is likely not how individuals would eat in a more natural setting and over-estimates energy intake in response to exercise [93–95]. It is also unknown if age plays a role in this response as the current study only included younger adults. Although we demonstrated hunger did not influence attentional bias or inhibitory control for food cues when assessed 3–5 hours post-prandial, additional studies using extremely hungry or well satiated individuals must be undertaken to confirm this is always the case. We also only assessed the effects of aerobic exercise on attentional bias. Whether other modes of exercise (resistance training) differentially alter attentional bias for food cues is unknown. Since the intensity of exercise was not assigned (all participants self-selected their intensity) we cannot make any assumptions on how exercise intensity may influence attentional bias or inhibitory control. Acute bouts of low to moderate intensity exercise (40–60% VO2 max) do not appear to influence appetite [96] while higher-intensity exercise has been shown to suppress hunger for up to 2 hours [97, 98]. It is unknown if high-intensity exercise would also influence attentional bias differently than low or moderate-intensity exercise.

5. Future Directions

Additional clinical trials are needed to definitively conclude exercise-induced increases in attentional bias are an important mechanism behind the compensatory response to an exercise program and thus responsible for weight-loss resistance. Future trials may consider including assessments of dietary intake to directly demonstrate exercise-induced increases in attentional bias are related to increases in energy intake. Although with the known underreporting habitual dietary intake assessments are subject to, this may be difficult [99, 100]. The present trial assessed attentional bias and inhibitory control once, 15 minutes after exercise, largely for participant convince and funding limitations. It may be interesting to assess these measures at different time points during the day after an exercise bout as more robust increases may present later in the day, or there may be a window where changes are most robust. Since the present trial only assessed this response to an acute bout of exercise, we are also uncertain if this response holds after a long-term exercise intervention. The long-term response may be the more important question, as exercise interventions for weight loss last much longer than a single exercise bout. Longitudinal studies demonstrating increased attentional bias for food cues during an exercise intervention are needed and could guide the development of novel interventions to improve the efficacy of exercise for weight loss. These longitudinal studies can also link exercise-induced increases in attentional bias to energy compensation and weight loss, further establishing attentional bias as a compensatory mechanism.

Highlights:

The mechanisms underlying energy compensation in response to exercise are not fully understood.

A large dose of exercise (500 kcal) increases attentional bias towards food cues while a 60-minute bout of television watching does not.

Inhibitory control is not influenced by exercise when assessed with a food-specific Go/NoGo task

Hunger does not influence attentional bias towards food cues.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thanks the University of Kentucky’s COBRE pilot program for selecting this project for funding and the Center for Clinical and Translational Science for their help in recruitment.

Funding:

The present study was supported by the National Institutes of Health P30GM127211 of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The funding source had no involvement in data collection, analysis, interpretation or the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Fletcher B, Gulanick M, Lamendola C Risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2002,16:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Padula WV, Allen RR, Nair KV Determining the cost of obesity and its common comorbidities from a commercial claims database. Clinical obesity. 2014,4:53–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pedersen SD Metabolic complications of obesity. Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2013,27:179–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Prospective Studies C, Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009,373:1083–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Avgerinos KI, Spyrou N, Mantzoros CS, Dalamaga M Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2019,92:121–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2013,309:71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011–2012. NCHS data brief. 2013:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Statistics, N. C. f. H. Health, United States, 2016: With Chart Book on Long-term Trends in Health. Hyattsville, MD: 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bray GA, Ryan DH Evidence-based weight loss interventions: Individualized treatment options to maximize patient outcomes. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2021,23 Suppl 1:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Santos I, Sniehotta FF, Marques MM, Carraca EV, Teixeira PJ Prevalence of personal weight control attempts in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2017,18:32–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Diabetes Prevention Program Research, G. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015,3:866–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].de Vries TI, Dorresteijn JAN, van der Graaf Y, Visseren FLJ, Westerink J Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects From an Intensive Lifestyle Weight Loss Intervention on Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Data From the Look AHEAD Trial. Diabetes Care. 2019,42:1988–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Thomas DM, Bouchard C, Church T, Slentz C, Kraus WE, Redman LM, et al. Why do individuals not lose more weight from an exercise intervention at a defined dose? An energy balance analysis. Obes Rev. 2012,13:835–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Thomas DM, Kyle TK, Stanford FC The gap between expectations and reality of exercise-induced weight loss is associated with discouragement. Prev Med. 2015,81:357–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].King NA, Caudwell P, Hopkins M, Byrne NM, Colley R, Hills AP, et al. Metabolic and behavioral compensatory responses to exercise interventions: barriers to weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007,15:1373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rosenkilde M, Auerbach P, Reichkendler MH, Ploug T, Stallknecht BM, Sjodin A Body fat loss and compensatory mechanisms in response to different doses of aerobic exercise--a randomized controlled trial in overweight sedentary males. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012,303:R571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Church TS, Martin CK, Thompson AM, Earnest CP, Mikus CR, Blair SN Changes in weight, waist circumference and compensatory responses with different doses of exercise among sedentary, overweight postmenopausal women. PLoS One. 2009,4:e4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].King NA, Hopkins M, Caudwell P, Stubbs RJ, Blundell JE Individual variability following 12 weeks of supervised exercise: identification and characterization of compensation for exercise-induced weight loss. International journal of obesity (2005). 2008,32:177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].King NA, Tremblay A, Blundell JE Effects of exercise on appetite control: implications for energy balance. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1997,29:1076–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Flack KD, Ufholz KE, Johnson LK, Fitzgerald JS, Roemmich JN Energy Compensation in Response to Aerobic Exercise Training in Overweight Adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Flack KD, Hays HM, Moreland J, Long DE Exercise for Weight Loss: Further Evaluating Energy Compensation with Exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2020,52:2466–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Drenowatz C Reciprocal Compensation to Changes in Dietary Intake and Energy Expenditure within the Concept of Energy Balance. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.). 2015,6:592–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Goele K, Bosy-Westphal A, Rumcker B, Lagerpusch M, Muller MJ Influence of changes in body composition and adaptive thermogenesis on the difference between measured and predicted weight loss in obese women. Obesity facts. 2009,2:105–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Byrne NM, Wood RE, Schutz Y, Hills AP Does metabolic compensation explain the majority of less-than-expected weight loss in obese adults during a short-term severe diet and exercise intervention? International journal of obesity (2005). 2012,36:1472–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A Adaptive thermogenesis with weight loss in humans. Obesity. 2013,21:218–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Goldsmith R, Joanisse DR, Gallagher D, Pavlovich K, Shamoon E, Leibel RL, et al. Effects of experimental weight perturbation on skeletal muscle work efficiency, fuel utilization, and biochemistry in human subjects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010,298:R79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rosenbaum M, Vandenborne K, Goldsmith R, Simoneau JA, Heymsfield S, Joanisse DR, et al. Effects of experimental weight perturbation on skeletal muscle work efficiency in human subjects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003,285:R183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A, et al. Long-Term Persistence of Hormonal Adaptations to Weight Loss. New Engl J Med. 2011,365:1597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mason C, Xiao L, Imayama I, Duggan CR, Campbell KL, Kong A, et al. The effects of separate and combined dietary weight loss and exercise on fasting ghrelin concentrations in overweight and obese women: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Endocrinol. 2015,82:369–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Suzuki K, Jayasena CN, Bloom SR Obesity and Appetite Control. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].King NA, Caudwell PP, Hopkins M, Stubbs JR, Naslund E, Blundell JE Dual-process action of exercise on appetite control: increase in orexigenic drive but improvement in meal-induced satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009,90:921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hagobian TA, Sharoff CG, Stephens BR, Wade GN, Silva JE, Chipkin SR, et al. Effects of exercise on energy-regulating hormones and appetite in men and women. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009,296:R233–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mason C, Xiao L, Imayama I, Duggan CR, Campbell KL, Kong A, et al. The effects of separate and combined dietary weight loss and exercise on fasting ghrelin concentrations in overweight and obese women: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015,82:369–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].King JA, Wasse LK, Stensel DJ Acute exercise increases feeding latency in healthy normal weight young males but does not alter energy intake. Appetite. 2013,61:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].King NA, Burley VJ, Blundell JE Exercise-induced suppression of appetite: effects on food intake and implications for energy balance. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994,48:715–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Schubert MM, Desbrow B, Sabapathy S, Leveritt M Acute exercise and subsequent energy intake. A meta-analysis. Appetite. 2013,63:92–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Heden TD, Liu Y, Park Y, Dellsperger KC, Kanaley JA Acute aerobic exercise differentially alters acylated ghrelin and perceived fullness in normal-weight and obese individuals. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2013,115:680–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Martins C, Kulseng B, King NA, Holst JJ, Blundell JE The effects of exercise-induced weight loss on appetite-related peptides and motivation to eat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010,95:1609–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lluch A, King NA, Blundell JE Exercise in dietary restrained women: no effect on energy intake but change in hedonic ratings. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998,52:300–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Appelhans BM Neurobehavioral inhibition of reward-driven feeding: implications for dieting and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009,17:640–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Doolan KJ, Breslin G, Hanna D, Murphy K, Gallagher AM Visual attention to food cues in obesity: an eye-tracking study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014,22:2501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hume DJ, Howells FM, Rauch HG, Kroff J, Lambert EV Electrophysiological indices of visual food cue-reactivity. Differences in obese, overweight and normal weight women. Appetite. 2015,85:126–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Nijs IM, Muris P, Euser AS, Franken IH Differences in attention to food and food intake between overweight/obese and normal-weight females under conditions of hunger and satiety. Appetite. 2010,54:243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hendrikse JJ, Cachia RL, Kothe EJ, McPhie S, Skouteris H, Hayden MJ Attentional biases for food cues in overweight and individuals with obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2015,16:424–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Evenden JL Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 1999,146:348–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bickel WK, Miller ML, Yi R, Kowal BP, Lindquist DM, Pitcock JA Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2007,90 Suppl 1:S85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Fillmore MT, Rush CR Impaired inhibitory control of behavior in chronic cocaine users. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2002,66:265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Fillmore MT, Rush CR Polydrug abusers display impaired discrimination-reversal learning in a model of behavioural control. J Psychopharmacol. 2006,20:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Pike E, Marks KR, Stoops WW, Rush CR Influence of Cocaine-Related Images and Alcohol Administration on Inhibitory Control in Cocaine Users. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2017,41:2140–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pike E, Marks KR, Stoops WW, Rush CR Cocaine-related stimuli impair inhibitory control in cocaine users following short stimulus onset asynchronies. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2015,110:1281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pike E, Stoops WW, Fillmore MT, Rush CR Drug-related stimuli impair inhibitory control in cocaine abusers. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2013,133:768–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kakoschke N, Kemps E, Tiggemann M Combined effects of cognitive bias for food cues and poor inhibitory control on unhealthy food intake. Appetite. 2015,87:358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Houben K, Nederkoorn C, Jansen A Eating on impulse: the relation between overweight and food-specific inhibitory control. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014,22:E6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Baltimore, Md: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Schubert MM, Seay RF, Spain KK, Clarke HE, Taylor JK Reliability and validity of various laboratory methods of body composition assessment in young adults. Clinical physiology and functional imaging. 2019,39:150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Schutte JE, Townsend EJ, Hugg J, Shoup RF, Malina RM, Blomqvist CG Density of lean body mass is greater in blacks than in whites. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984,56:1647–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Siri WE Body composition from fluid spaces and density: analysis of methods. 1961. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.). 1993,9:480–91; discussion, 92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Strath SJ, Bassett DR Jr., Swartz AM Comparison of MTI accelerometer cut-points for predicting time spent in physical activity. International journal of sports medicine. 2003,24:298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Marks KR, Roberts W, Stoops WW, Pike E, Fillmore MT, Rush CR Fixation time is a sensitive measure of cocaine cue attentional bias. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2014,109:1501–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Roberts W, Fillmore MT, Milich R Drinking to distraction: does alcohol increase attentional bias in adults with ADHD? Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012,20:107–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Marks KR, Pike E, Stoops WW, Rush CR Test-retest reliability of eye tracking during the visual probe task in cocaine-using adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014,145:235–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Alcorn JL 3rd, Pike E, Stoops WS, Lile JA, Rush CR A pilot investigation of acute inhibitory control training in cocaine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017,174:145–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Oh H, Taylor AH A brisk walk, compared with being sedentary, reduces attentional bias and chocolate cravings among regular chocolate eaters with different body mass. Appetite. 2013,71:144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Fearnbach SN, Silvert L, Pereira B, Boirie Y, Duclos M, Keller KL, et al. Reduced neural responses to food cues might contribute to the anorexigenic effect of acute exercise observed in obese but not lean adolescents. Nutrition research (New York, N.Y.). 2017,44:76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Evero N, Hackett LC, Clark RD, Phelan S, Hagobian TA Aerobic exercise reduces neuronal responses in food reward brain regions. Journal of applied physiology. 2012,112:1612–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hanlon B, Larson MJ, Bailey BW, LeCheminant JD Neural response to pictures of food after exercise in normal-weight and obese women. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2012,44:1864–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Fearnbach SN, Silvert L, Keller KL, Genin PM, Morio B, Pereira B, et al. Reduced neural response to food cues following exercise is accompanied by decreased energy intake in obese adolescents. International journal of obesity (2005). 2016,40:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Masterson TD, Kirwan CB, Davidson LE, Larson MJ, Keller KL, Fearnbach SN, et al. Brain reactivity to visual food stimuli after moderate-intensity exercise in children. Brain imaging and behavior. 2018,12:1032–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Appelhans BM, Woolf K, Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Whited MC, Liebman R Inhibiting food reward: delay discounting, food reward sensitivity, and palatable food intake in overweight and obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011,19:2175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Houben K Overcoming the urge to splurge: influencing eating behavior by manipulating inhibitory control. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011,42:384–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Epstein LH, Salvy SJ, Carr KA, Dearing KK, Bickel WK Food reinforcement, delay discounting and obesity. Physiol Behav. 2010,100:438–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Rollins BY, Dearing KK, Epstein LH Delay discounting moderates the effect of food reinforcement on energy intake among non-obese women. Appetite. 2010,55:420–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ely AV, Howard J, Lowe MR Delayed discounting and hedonic hunger in the prediction of lab-based eating behavior. Eat Behav. 2015,19:72–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Stojek MMK, MacKillop J Relative reinforcing value of food and delayed reward discounting in obesity and disordered eating: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017,55:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Price M, Lee M, Higgs S Food-specific response inhibition, dietary restraint and snack intake in lean and overweight/obese adults: a moderated-mediation model. International journal of obesity (2005). 2016,40:877–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zhang L, Chu CH, Liu JH, Chen FT, Nien JT, Zhou C, et al. Acute coordinative exercise ameliorates general and food-cue related cognitive function in obese adolescents. J Sports Sci. 2020,38:953–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Chang YK, Chu CH, Wang CC, Song TF, Wei GX Effect of acute exercise and cardiovascular fitness on cognitive function: an event-related cortical desynchronization study. Psychophysiology. 2015,52:342–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Bechara A Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: a neurocognitive perspective. Nature neuroscience. 2005,8:1458–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Tanaka SC, Doya K, Okada G, Ueda K, Okamoto Y, Yamawaki S Prediction of immediate and future rewards differentially recruits cortico-basal ganglia loops. Nature neuroscience. 2004,7:887–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Rubenis AJ, Fitzpatrick RE, Lubman DI, Verdejo-Garcia A Impulsivity predicts poorer improvement in quality of life during early treatment for people with methamphetamine dependence. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2018,113:668–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Smith JL, Mattick RP, Jamadar SD, Iredale JM Deficits in behavioural inhibition in substance abuse and addiction: a meta-analysis. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2014,145:1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Stevens L, Verdejo-García A, Goudriaan AE, Roeyers H, Dom G, Vanderplasschen W Impulsivity as a vulnerability factor for poor addiction treatment outcomes: a review of neurocognitive findings among individuals with substance use disorders. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2014,47:58–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Kirk-Sanchez NJ, McGough EL Physical exercise and cognitive performance in the elderly: current perspectives. Clinical interventions in aging. 2014,9:51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Yoon DH, Lee JY, Song W Effects of Resistance Exercise Training on Cognitive Function and Physical Performance in Cognitive Frailty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2018,22:944–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Chang YK, Labban JD, Gapin JI, Etnier JL The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Brain research. 2012,1453:87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Cassilhas RC, Tufik S, de Mello MT Physical exercise, neuroplasticity, spatial learning and memory. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2016,73:975–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Staten MA The effect of exercise on food intake in men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991,53:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Stubbs RJ, Sepp A, Hughes DA, Johnstone AM, King N, Horgan G, et al. The effect of graded levels of exercise on energy intake and balance in free-living women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002,26:866–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Westerterp KR, Meijer GA, Janssen EM, Saris WH, Ten Hoor F Long-term effect of physical activity on energy balance and body composition. The British journal of nutrition. 1992,68:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Wade GN, Jones JE Neuroendocrinology of nutritional infertility. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004,287:R1277–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Thackray AE, Deighton K, King JA, Stensel DJ Exercise, Appetite and Weight Control: Are There Differences between Men and Women? Nutrients. 2016,8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Dorling J, Broom DR, Burns SF, Clayton DJ, Deighton K, James LJ, et al. Acute and Chronic Effects of Exercise on Appetite, Energy Intake, and Appetite-Related Hormones: The Modulating Effect of Adiposity, Sex, and Habitual Physical Activity. Nutrients. 2018,10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Larson DE, Rising R, Ferraro RT, Ravussin E Spontaneous overfeeding with a ‘cafeteria diet’ in men: effects on 24-hour energy expenditure and substrate oxidation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995,19:331–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Halliday TM, White MH, Hild AK, Conroy MB, Melanson EL, Cornier MA Appetite and Energy Intake Regulation in Response to Acute Exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2021,53:2173–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Balaguera-Cortes L, Wallman KE, Fairchild TJ, Guelfi KJ Energy intake and appetite-related hormones following acute aerobic and resistance exercise. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme. 2011,36:958–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Unick JL, Otto AD, Goodpaster BH, Helsel DL, Pellegrini CA, Jakicic JM Acute effect of walking on energy intake in overweight/obese women. Appetite. 2010,55:413–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Broom DR, Stensel DJ, Bishop NC, Burns SF, Miyashita M Exercise-induced suppression of acylated ghrelin in humans. Journal of applied physiology. 2007,102:2165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].King JA, Miyashita M, Wasse LK, Stensel DJ Influence of prolonged treadmill running on appetite, energy intake and circulating concentrations of acylated ghrelin. Appetite. 2010,54:492–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Trabulsi J, Schoeller DA Evaluation of dietary assessment instruments against doubly labeled water, a biomarker of habitual energy intake. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001,281:E891–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Castro-Quezada I, Ruano-Rodríguez C, Ribas-Barba L, Serra-Majem L Misreporting in nutritional surveys: methodological implications. Nutricion hospitalaria. 2015,31 Suppl 3:119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]