Abstract

This study describes the characteristics of—and the counseling received by—counselees who passed away through self-ingesting self-collected lethal medication after receiving demedicalised assistance in suicide. We analyzed registration forms filled in by counselors working with Foundation De Einder about 273 counselees who passed away from 2011 to 2015. The majority of these counselees had a serious disease and physical or psychiatric suffering. Half of them had requested physician assistance in dying. This shows that patients with a denied request for physician assistance in dying can persist in their wish to end life. This also shows that not all people with an underlying medical disease request for physician assistance in dying. Physicians and psychiatrist are often uninvolved in these self-chosen deaths while they could have a valuable role in the process concerning assessing competency, diagnosing diseases, and offering (or referring for) treatment.

Keywords: counseling, suicide, right to die, assisted dying/suicide, euthanasia

About 8% of adults in the general population in the Netherlands have had suicidal thoughts during their life. The chance to develop a wish to end life is strongly related to childhood traumas and earlier psychic disorders (ten Have et al., 2011). About 5% to 30% of the wish to end life in older people is, however, not associated with psychiatric or depressive disorders but, for example, with physical risk factors (such as physical decline related to old age) or psychological risk factors (such as loss of connectedness; Rurup, Deeg, et al., 2011; Rurup, Pasman, et al., 2011; van Wijngaarden et al., 2014).

In the Netherlands, people with a wish to end life can request for physician assistance in dying (PAD) under the Dutch Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Review Procedures Act. People can only obtain PAD when they meet all criteria of due care laid out in the law. Under Section 2(1) of the Act, the physician must (a) be satisfied that the patient’s request is voluntary and well considered, (b) be satisfied that the patient’s suffering is unbearable, with no prospect of improvement, (c) have informed the patient about his situation and his prognosis, (d) have come to the conclusion, together with the patient, that there is no reasonable alternative in the patient’s situation, (e) have consulted at least one other, independent physician, who must see the patient and give a written opinion on whether these due care criteria have been fulfilled, and (f) have exercised due medical care and attention in terminating the patient’s life or assisting in his suicide (Regional Euthanasia Review Committees, 2018). Supreme Court rulings added the requirement that the suffering must be the result of an underlying medical diagnosis, either physical or psychiatric in nature (Regional Euthanasia Review Committees, 2018). In the Netherlands, 4.6% of all annual deaths in 2015 have resulted from PAD under the Dutch PAD law. The great majority (92%) of the patients receiving PAD have a (serious) physical disorder, while only a small minority has a psychiatric disorder (3%) or has psychosocial or existential problems (3%; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., 2017).

In the Netherlands, 1,829 people have committed suicide in 2018, which accounts for 1.2% of all annual deaths (Statistics Netherlands, 2020a). Many of these registered suicides have occurred through mutilating methods, such as hanging or strangling (46%) or jumping in front of a moving object or from a great height (19%) and often occur in solitary and isolated circumstances (Statistics Netherlands, 2020b). About two thirds of these suicides are motivated by psychic disorders and about 1 in 12 by physical disorders (Statistics Netherlands, 2020b).

However, suicides do not always need to occur through mutilating methods, nor have to occur in solitary and isolated circumstances. In the Netherlands, several organizations offer counseling to be able to self-determine the timing and manner of your end of life (Hagens et al., 2014, 2017, 2019). This demedicalized assistance in suicide (DAS) exists of having conversations about the wish to end life, offering moral support, and/or providing general information on methods how to end your life in a nonviolent and nonmutilating manner (Hagens et al., 2017). Research has shown that almost half of the people seeking this counseling suffer from a terminal or serious disease. Almost half primarily suffers from physical conditions, while a quarter primarily has psychiatric suffering. About 4 in 10 wish to end life within a year. These people seem to seek a peaceful death to escape from current suffering (Hagens et al., 2014). About one third of the people seeking counseling have primarily psychological suffering (e.g., existential suffering) or do not mention any current suffering at the time they start counseling (e.g., healthy people who wish to avoid situations such as being dependent later in life). More than one third does not have a wish to end life when they start counseling. These people seem to seek reassurance to prevent possible prospective suffering (Hagens et al., 2014). About one eighth of all the people seeking this counseling have ended their lives themselves (Hagens et al., 2014). Interestingly, this practice of DAS exists next to the medicalized practice of physician assistance in dying (PAD). Counselees who seek DAS who have physical or psychiatric suffering can meet the criteria to obtain PAD, but former research has shown only half of them has requested for such assistance (Hagens et al., 2014).

The Dutch practice of DAS shows that counselees who decide to end their own life mostly choose to end life through voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED) or self-ingesting self-collected lethal medication (MED; Chabot & Goedhart, 2009; Hagens et al., 2014; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., 2017). In the Netherlands, limited information is available about VSED (Bolt et al., 2015; Chabot & Goedhart, 2009; KNMG Royal Dutch Medical Association, & V&VN Dutch Nurses’ Association, 2014; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., 2017) and even less about MED (Chabot & Goedhart, 2009; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., 2017). Chabot has published a qualitative interview study with relatives, doctors, and right-to-die activists about people who have passed away through MED after receiving DAS and a nationwide quantitative study on self-directed dying through VSED and MED (Chabot, 2001, 2007). Furthermore, the quinquennial evaluation of the Termination of Life and Assisted Suicide Review Procedures Act has obtained information from physicians about patients who have ended life themselves through VSED and MED (Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., 2017). While the latter two studies offer estimates about the occurrence based on greater samples, both studies included a low number of cases to report on personal characteristics. Furthermore, physicians are not always informed about nor involved in the patients’ intentions to end life themselves. This especially seems to be the case for people who pass away through MED (Chabot, 2007; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., 2017).

We would like to extend on the existing information on people who have passed away through MED by conducting a study with information gathered from counselors working with Foundation De Einder (see Box 1 for history, aim, and work method of Foundation De Einder). These counselors provide counseling to people who wish to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life. Previous research has shown the majority of the counselees who pass away, have passed away through MED (Hagens et al., 2014). Counselors therefore seem to be more often involved in (the preparation of) a self-directed death by MED than physicians and can form a valuable contribution to the knowledge about this form of dying in the Netherlands.

Box 1.

History, Aim, and Work Method of Foundation De Einder

| Foundation | Foundation De Einder was founded in 1995 as a result of dissatisfaction with the situation that people with a wish to end life were confronted with closed doors or were only offered ways to cure the wish to end life. This often resulted in these people having to continue life with unbearable suffering, or in committing a mutilating suicide in isolation, causing a lot of suffering for close ones and involuntary involved (Foundation De Einder, 2016). |

| Aim | The goal of the foundation is “to promote and – if deemed necessary – to offer professional counseling for people with a wish to end life who ask for help, with respect for the autonomy of the person asking for help […]” (Foundation De Einder, p. 9). Contrary to suicide prevention or crisis intervention organizations, Foundation De Einder regards ending your own life as a possible outcome and gives information about self-euthanasia (Vink, 2013). Autonomy is regarded as an important value. Seen as an addition to the—since 2001 in the Netherlands legally regulated—medicalized approach of physician assistance in dying (PAD), Foundation De Einder works in cooperation with independent counselors to offer counseling focused on demedicalized assistance in suicide (DAS). |

| Work method | People who wish to self-determine the timing and manner of their own end of life contact Foundation De Einder themselves. They are referred to counselors working in cooperation with Foundation De Einder who offer nondirective counseling, which consists of having conversations, offering mental support, and providing general information on self-euthanasia. These three forms of assistance by laypersons are regarded as nonpunishable assistance in suicide (The Netherlands Case Law, 1995). The counseling is not aimed at a certain choice or direction but is “aimed at attaining the highest possible quality of the choice and -- if it comes to that -- the highest possible quality of implementation of the wish to end one's own life” (Foundation De Einder, 2016, p. 26). The counseling is aimed at creating an as large as possible clarity regarding the wish to end one’s life and possible suicide. This covers the mental process of decision making and might include matters such as considering alternatives, timing of death, and consideration of others. If the counselee decides to act upon his or her desire to end their life, the counseling is aimed at realizing the best possible preparations for self-euthanasia. This covers the practical preparation and might include gathering means for and the effectuation ending your own life (Foundation De Einder, 2016; Vink, 2008). |

First of all, we are interested in the personal characteristics of, and the counseling received by, counselees who passed away through MED after receiving counseling to be able to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life. Furthermore, we are interested in the differences in the characteristics of the counselees and the counseling between counselees with physical, psychiatric, and psychological or no underlying suffering.

Method

Design

This cross-sectional study consisted of data that were collected from annual registration forms (questionnaires) that counselors working with Foundation De Einder filled out for all counselees they had had contact with the preceding year.

Population

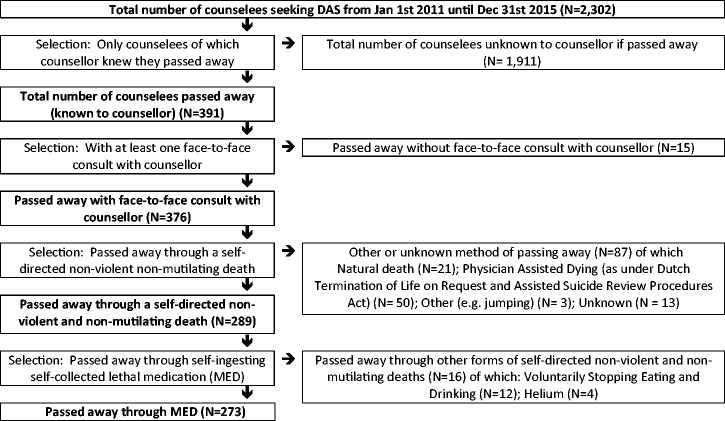

Data over the years 2011 to 2015 were collected in the first 2 months of the consecutive year. All counselors working in cooperation with Foundation De Einder in that period (N = 12) filled out the registration forms (response rate 100%). Four counselors filled out the forms for all 5 years, while the other counselors filled them in for fewer years as a result of starting or ending working as a counselor within these 5 years. This resulted in data on 2,302 persons seeking DAS. For answering the research questions in this article, we selected people of which the counselor knew they passed away (N = 391). Only people with whom the counselor had had at least one face-to-face contact during the counseling were selected for analysis. As explained in our previous study, counselors only share explicit information about self-collecting and self-ingesting lethal medication during face-to-face contacts due to the sensitivity of the information (Hagens et al., 2014). This resulted in data on 376 people who passed away in the years from 2011 until September 2015. The majority of these counselees passed away through MED (N = 273; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of Participants for Analysis.

DAS = demedicalized assistance in suicide.

Measurement Instrument

The researcher digitalized the registration form that was previously used by the board of Foundation De Einder and—in consultation with counselors—expanded the form. To increase reliability and uniformity and to avoid bias, several meetings with the counselors were held to explain the instructions for filling out the form. The registration form underwent minor changes and expansion as a result of feedback from counselors and the wish to collect more information. The registration form consisted of four general areas: (a) personal characteristics of the counselee, (b) overview of the situation of the counselee prior to the start of counseling, (c) characteristics of the counseling process, and (d) outcome of the counseling process (see Additional File 1). All forms returned by the counselors were processed anonymously.

Based on the information provided by the counselees, the counselors provided a description of the situation of, and/or the suffering experienced by, the counselees, such as cancer, dementia, mood disorders, an accumulation of problems related to old age or completed life. The counselor assessed the primary underlying suffering of the counselee at the time they sought counseling: physical (when there are primarily physical and somatic complaints, e.g., cancer or stroke), psychiatric (when there are primarily officially diagnosed psychiatric disorders, e.g., depression or personality disorders), psychological suffering (when there is primarily psychological suffering, e.g., grief or suffering from life), or no current suffering (when the prior forms of suffering are absent, e.g., preparing for self-determination or people who wish to have reassurance for possible prospective suffering). Furthermore, the counselor classified the clients into four categories of severity of the disease (if present): (a) terminal or advanced disease when cancer in a terminal or advanced phase or other disease with terminal diagnose was medically diagnosed, (b) severe disease when a serious somatic disease (not terminal cancer; e.g., heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular accident) and/or serious psychiatric disease (e.g., severe depression) was medically diagnosed, (c) nonsevere disease (e.g., problems of old age, deterioration of mobility, problems of vision or hearing), or (d) no disease, when counselees presented no physical or psychiatric complaints.

Analysis

A description was given on frequencies of categories, focusing on the characteristics of the counselees and the characteristics of the counseling. Furthermore, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to compare groups with different primary underlying suffering at the time they sought counseling. Both calculations were made with SPSS version 20.0.0. A comparison was made between counselees with primarily underlying physical suffering, counselees with primarily underlying psychiatric suffering, counselees with primarily underlying psychological suffering, and counselees without underlying suffering. The latter two were combined as both lack an underlying medical diagnosis which is a prerequisite to be able to receive PAD under the Dutch Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Review Procedures Act.

Approval by Ethics Committee

This study did not require approval under the Dutch law on medical-scientific research with humans because participants were not subjected nor imposed to certain acts or behaviors. This exemption from requiring ethics approval had been granted by the VU Medical Center Medical Ethics Committee.

Results

Characteristics of Counselees Passing Away Through MED

Underlying Suffering

The primary underlying suffering of the majority of counselees who passed away through MED at the time they sought counseling was—according to the counselor—characterized by physical suffering (42%), mostly an accumulation of problems related to old age (mentioned by 14% of the counselees), dementia (7%), cancer (6%), rheumatic diseases (5%), and pain (4%; see Table 1). For a third of the counselees (32%), the primary underlying suffering entailed psychiatric suffering, with mood disorders (22%), personality disorders (13%), trauma and stress disorders (9%), fear disorders (9%), and obsessive-compulsive disorders (7%) mostly mentioned. Furthermore, a quarter of the counselees (26%) primarily had psychological suffering or did not mention underlying suffering at the start of counseling, for example, completed life (19%), or striving for self-determination (4%; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of Underlying Suffering at Start of Counselling and Seriousness of Disease (According to Counselor) of Counselees Passing Away Through Self-Ingesting Self-Collected Lethal Medication (MED) Divided by Primary Underlying Suffering at Start of Counseling (According to Counselor; N = 273; Missing N = 2).

|

Primary underlying suffering |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All (N = 273) |

Physical suffering (N = 114) |

Psychiatric suffering (N = 86) |

Psychological or no suffering (N = 71) |

|||||

| N | % | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | |

| Description of underlying suffering a,b | N = 271 | N = 85 c | N = 69 c | |||||

| Physical suffering | N = 114 | 42 | ||||||

| Accumulation problems of old age d | 38 | 14 | 26 | 23 [16, 31] | 0 | 0 [0, 3] | 12 | 17 [10, 28] |

| Dementia | 19 | 7 | 11 | 10 [5, 16] | 1 | 1 [0, 5] | 7 | 10 [5, 19] |

| Cancer | 16 | 6 | 14 | 12 [7, 19] | 0 | 0 [0, 3] | 2 | 3 [1, 9] |

| Rheumatic | 13 | 5 | 12 | 11 [6, 17] | 1 | 1 [0, 5] | 0 | 0 [0, 4] |

| Pain | 12 | 4 | 12 | 11 [6, 17] | 0 | 0 [0, 3] | 0 | 0 [0, 4] |

| Physical other e | 67 | 25 | 49 | 43 [34, 52] | 12 | 14 [8, 23] | 6 | 9 [4, 17] |

| Psychiatric suffering | N = 86 | 32 | ||||||

| Mood disorders | 59 | 22 | 2 | 2 [0, 6] | 51 | 60 [49, 70] | 6 | 9 [4, 17] |

| Personality disorders | 36 | 13 | 0 | 0 [0, 2] | 33 | 39 [29, 49] | 3 | 4 [1, 11] |

| Trauma and stress disorders | 24 | 9 | 1 | 1 [0, 4] | 17 | 20 [13, 29] | 6 | 9 [4, 17] |

| Fear disorders | 24 | 9 | 0 | 0 [0, 2] | 14 | 16 [10, 25] | 4 | 6 [2, 13] |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 20 | 7 | 1 | 1 [0, 4] | 14 | 16 [10, 25] | 5 | 7 [3, 15] |

| Psychiatric other f | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 [0, 2] | 5 | 6 [2, 12] | 1 | 1 [0, 7] |

| Psychological or no suffering | N = 71 | 26 | ||||||

| Completed life | 52 | 19 | 12 | 11 [6, 17] | 6 | 7 [3, 14] | 32 | 46 [35, 58] |

| Self-determination | 11 | 4 | 3 | 3 [1, 7] | 0 | 0 [0, 3] | 8 | 12 [6, 21] |

| Psychological other g | 22 | 8 | 6 | 5 [2, 11] | 2 | 2 [0, 7] | 14 | 20 [12, 31] |

| Seriousness of disease | N = 249 h | N = 107 h | N = 76 i | N = 64 h | ||||

| Terminal/serious disease | 162 | 65 | 84 | 79 [70, 85] | 62 | 82 [72, 89] | 16 | 25 [15, 37] |

| No (serious) disease | 87 | 35 | 23 | 22 [15, 30] | 14 | 18 [11, 28] | 48 | 75 [63, 84] |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

aOnly the clarifications of underlying suffering mentioned if suffering occurred in ≥ 4% of all counselees.

bAdds up to more than 100% due to comorbidity.

cMissing less than 5%.

dAn accumulation of problems related to old age concerns a comorbidity of lesser nonserious problems of old age, for example, problems with mobility, loss of eyesight, weakening physical condition, and so forth.

ePhysical other includes sleep-wake disorders, heart and vascular diseases, Parkinson’s disease, muscular diseases, osteoporosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tinnitus, neurological disorders, autism, Lyme disease, and deafness.

fPsychiatric other includes feeding and eating disorders.

gPsychological other includes grief, loneliness, addiction, gender issues, and family problems.

hMissing between 5% and 10%.

iMissing ≥ 10%.

According to the counselor, around two thirds of the counselees (65%) had a serious or terminal disease at the time they sought counseling. Counselees with primarily psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling less often had a serious (or terminal) disease (25%, 95% CI [15, 37]) than counselees with primarily physical suffering (79%, 95% CI [70, 85]) or psychiatric suffering (82%, 95% CI [72, 89]; see Table 1)

Personal Characteristics

Half of the counselees were younger than 65 years old. Counselees with primarily psychiatric suffering were more often aged younger than 65 years old (84%, 95% CI [75, 90]) than counselees with physical suffering (35%, 95% CI [27, 44]) and counselees with psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling (37%, 95% CI [27, 49]) and were less often aged older than 80 years old (2%, 95% CI [0, 7]) than counselees with physical suffering (35%, 95% CI [27, 44]) and counselees with psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling (34%, 95% CI [24, 46]; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Counselees Passing Away Through Self-Ingesting Self-Collected Lethal Medication (MED) Divided by Primary Underlying Suffering at the Start of Counseling (According to Counselor; N = 273; Missing N = 2).

|

Primary underlying suffering |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All (N = 273) |

Physical suffering (N = 114) |

Psychiatric suffering (N = 86) |

Psychological or no suffering (N = 71) |

|||||

| N | % | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | |

| Gender | N = 273 | N = 114 | N = 86 | N = 71 | ||||

| Male | 90 | 33 | 39 | 34 [26, 43] | 25 | 29 [20, 39] | 26 | 37 [26, 48] |

| Female | 183 | 67 | 75 | 66 [57, 74] | 61 | 71 [61, 80] | 45 | 63 [52, 74] |

| Age groups | N = 268 a | N = 111 a | N = 85 a | N = 70 a | ||||

| 0–64 years | 136 | 51 | 39 | 35 [27, 44] | 71 | 84 [75, 90] | 26 | 37 [27, 49] |

| 65–79 years | 66 | 25 | 33 | 30 [22, 39] | 12 | 14 [8, 23] | 20 | 29 [19, 40] |

| 80 years and older | 66 | 25 | 39 | 35 [27, 44] | 2 | 2 [0, 7] | 24 | 34 [24, 46] |

| Wish to end life at start counseling b | N = 244 a | N = 103 a | N = 74 c | N = 65 a | ||||

| Yes… | 219 | 90 | 92 | 89 [82, 94] | 72 | 97 [92, 99] | 54 | 83 [73, 91] |

| N = 219 | N = 92 | N = 72 | N = 54 | |||||

| …< 3 months d | 83 | 38 | 37 | 40 [31, 50] | 20 | 28 [18, 39] | 26 | 48 [35, 61] |

| … 3–12 months d | 82 | 37 | 42 | 46 [36, 56] | 19 | 26 [17, 37] | 20 | 37 [25, 50] |

| …> 1 year aheadd | 54 | 25 | 13 | 14 [8, 22] | 33 | 46 [35, 57] | 8 | 15 [7, 26] |

| Prior suicide attempt e | N = 196 c | N = 88 a | N = 55 c | N = 51 f | ||||

| Yes | 53 | 27 | 8 | 9 [4, 17] | 32 | 58 [45, 71] | 13 | 26 [15, 39] |

| Request for PAD | N = 268 a | N = 113 a | N = 83 a | N = 70 a | ||||

| No request | 141 | 53 | 52 | 46 [37, 55] | 38 | 46 [35, 56] | 49 | 70 [59, 80] |

| With request | 127 | 47 | 61 | 54 [45, 63] | 45 | 54 [44, 65] | 21 | 30 [20, 41] |

| Result if request PAD g | N = 126 a | N = 60 a | N = 45 | N = 21 | ||||

| Denied | 108 | 85 | 50 | 82 [72, 91] | 39 | 87 [75, 94] | 19 | 91 [73, 100] |

| Pending | 16 | 13 | 8 | 13 [7, 24] | 6 | 13 [6, 25] | 2 | 10 [2, 27] |

| Granted | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 [1, 10] | 0 | 0 [0, 5] | 0 | 0 [0, 11] |

| Previous help sought h | N = 194 c | N = 86 a | N = 55 c | N = 51 f | ||||

| Yes… | 122 | 63 | 49 | 57 [46, 67] | 37 | 67 [54, 79] | 35 | 69 [55, 80] |

| N = 121 a | N = 49 | N = 37 | N = 35 | |||||

| … with physician i | 46 | 38 | 24 | 49 [35, 63] | 9 | 24 [13, 40] | 13 | 37 [23, 54] |

| … with Right-to-Die Netherlands i | 38 | 31 | 20 | 41 [28, 55] | 5 | 14 [5, 27] | 12 | 34 [20, 51] |

| … with psychiatrist i | 31 | 25 | 1 | 2 [0, 9] | 23 | 62 [46, 76] | 7 | 20 [9, 35] |

| … with End-of-Life Clinici,j | 17 | 14 | 5 | 10 [4, 21] | 5 | 14 [5, 27] | 7 | 20 [9, 35] |

Note. CI = confidence interval; PAD = physician assistance in dying.

aMissing less than 5%

bCategory only registered for deaths from 2012 (N = 254).

cMissing 5% to 10%.

dCategory only registered for deaths from 2012 and wish to end life at start of counseling (N = 219).

eCategory only registered for deaths from 2013 (N = 209).

fMissing ≥ 10%.

gOnly for counselees with a request for PAD (N = 127).

hPreviously help sought with wish to be able to self-determine the timing and manner of own end of life.

iCategory only registered for deaths from 2013 and seeking aid in dying (N = 122).

jEnd-of-Life Clinic (currently known as Euthanasia Expertise Centre).

Wish to End Life and Prior Suicide Attempts

Almost all counselees who passed away through MED (90%) had a wish to end life at the start of counseling. One third of these counselees (38%) wished to end life within 3 months and another third (37%) within 1 year from the start of the counseling. Counselees with primarily psychiatric suffering more often expressed to have a wish to end life at the start of counseling (97%, 95% CI [92, 99]) than counselees with psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling (83%, 95% CI [72, 91]). They, however, more often expressed their wish to be more than 1 year away (46%, 95% CI [35, 57]) compared with both counselees with physical suffering (14%, 95% CI [8, 22]) and counselees with psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling (15%, 95% CI [7, 26]).

One quarter of the counselees who passed away through MED (27%) attempted suicide before. Counselees with primarily psychiatric suffering more often attempted suicide before (58%, 95% CI [45, 71]) than both counselees with physical suffering (9%, 95% CI [4, 17]) and counselees with psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling (26%, 95% CI [15, 39]; see Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Received Counseling of Counselees Passing Away Self-Ingesting Self-Collected Lethal Medication (MED) Divided by Primary Underlying Suffering at Start of Counselling (according to counsellor) (N = 273; Missing N = 2).

|

Primary underlying suffering |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All (N = 273) |

Physical suffering (N = 114) |

Psychiatric suffering (N = 86) |

Psychological or no suffering (N = 71) |

|||||

| Characteristics | N | % | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) |

| Number of personal consults | N = 273 | N = 114 | N = 86 | N = 71 | ||||

| 1 | 125 | 46 | 59 | 52 [43, 71] | 38 | 44 [34, 55] | 26 | 37 [26, 48] |

| 2 | 89 | 33 | 28 | 25 [17, 33] | 32 | 37 [28, 48] | 29 | 41 [30, 53] |

| ≥ 3 (max 14) | 59 | 22 | 27 | 24 [17, 32] | 16 | 19 [11, 28] | 16 | 23 [14, 33] |

| Total number of contacts | N = 273 | N = 114 | N = 86 | N = 71 | ||||

| 1 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 5 [2, 11] | 0 | 0 [0, 3] | 0 | 0 [0, 3] |

| 2–3 | 39 | 14 | 19 | 17 [11, 24] | 13 | 15 [9, 24] | 7 | 10 [4, 18] |

| 4–6 | 101 | 37 | 44 | 39 [30, 48] | 35 | 41 [31, 51] | 20 | 28 [19, 39] |

| ≥ 7 (max 36) | 127 | 47 | 45 | 40 [31, 49] | 38 | 44 [35, 55] | 44 | 62 [50, 73] |

| Duration of counseling | N = 267 a | N = 110 a | N = 85 a | N = 70 a | ||||

| ≤ 3 months | 123 | 46 | 48 | 44 [35, 53] | 42 | 49 [39, 60] | 33 | 47 [36, 59] |

| 3–12 months | 96 | 36 | 48 | 44 [35, 53] | 28 | 33 [24, 43] | 19 | 27 [18, 38] |

| > 12 months | 48 | 18 | 14 | 13 [7, 20] | 15 | 18 [11, 27] | 18 | 26 [17, 37] |

| Content of counseling b | N = 251 a | N = 104 a | N = 77 a | N = 68 a | ||||

| General information | 248 | 99 | 102 | 98 [94, 100] | 76 | 99 [94, 100] | 68 | 100 [96, 100] |

| Moral support | 250 | 100 | 103 | 99 [96, 100] | 77 | 100 [97, 100] | 68 | 100 [96, 100] |

| Mental support | 230 | 92 | 94 | 90 [84, 95] | 70 | 91 [83, 96] | 64 | 94 [87, 98] |

| Counseling about others | 222 | 88 | 99 | 95 [90, 98] | 62 | 81 [71, 88] | 59 | 87 [77, 93] |

| Information PAD | 176 | 70 | 72 | 69 [60, 77] | 56 | 73 [62, 82] | 47 | 69 [58, 79] |

| Information preparation MED | 247 | 98 | 103 | 99 [96, 100] | 75 | 97 [92, 99] | 68 | 100 [96, 100] |

| Information perform MED | 248 | 98 | 103 | 99 [96, 100] | 74 | 96 [90, 99] | 68 | 100 [96, 100] |

| Legal information | 247 | 98 | 103 | 99 [96, 100] | 74 | 96 [90, 99] | 67 | 99 [93, 100] |

| Involving others in counseling | N = 273 | N = 114 | N = 86 | N = 71 | ||||

| Yes | 186 | 68 | 93 | 82 [74, 88] | 46 | 54 [43, 64] | 46 | 65 [53, 75] |

| Which others involved | N = 148 c | N = 71 c | N = 39 c | N = 38 c | ||||

| Partner | 34 | 23 | 21 | 30 [20, 41] | 7 | 18 [8, 32] | 6 | 16 [7, 30] |

| Children | 51 | 34 | 28 | 39 [29, 51] | 5 | 13 [5, 26] | 18 | 47 [32, 63] |

| Parents | 10 | 7 | 3 | 4 [1, 11] | 6 | 15 [7, 29] | 1 | 3 [0, 12] |

| Other family and/or friends d | 43 | 29 | 18 | 25 [16, 36] | 15 | 39 [24, 54] | 10 | 26 [14, 42] |

| Others (professionals) e | 10 | 7 | 3 | 4 [1, 11] | 4 | 10 [4, 23] | 3 | 8 [2, 20] |

| Involved and/or openness | N = 262 a | N = 112 a | N = 81 a | N = 68 a | ||||

| Involvement and/or openness | 205 | 78 | 101 | 90 [84, 95] | 54 | 67 [56, 76] | 49 | 72 [61, 82] |

| No involvement nor openness | 57 | 22 | 11 | 10 [5, 16] | 27 | 33 [24, 44] | 19 | 28 [18, 39] |

| Conversations with bereaved | N = 257 f | N = 108 f | N = 78 f | N = 69 a | ||||

| Yes | 149 | 55 | 72 | 67 [57, 75] | 39 | 50 [39, 61] | 38 | 55 [43, 66] |

Note. CI = confidence interval; PAD = physician assistance in dying.

aMissing less than 5%.

bCategory only registered for deaths from 2012 (N = 254).

cMissing ≥ 10%.

dOther family and/or friends includes grandchild(ren), brother(s), sister(s), cousin, friend(s), and acquaintance(s).

eOthers (professionals) include physician nurse, psychologist, Right-to-Die-Netherlands volunteer, therapist, legal representative, and documentary maker.

fMissing 5% to 10%.

Previously Sought Help

Half of the counselees who passed away through MED had requested PAD before (47%). The majority of them (85%) were confronted with a refusal of their request. Counselees with primarily psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling least often had requested for PAD (30%, 95% CI [20, 41]) compared with counselees with physical suffering (54%, 95% CI [45, 63]) and psychiatric suffering (54%, 95% CI [44, 65]).

Counselees also contacted other organizations or professionals with their current wish to be able to self-determine the timing and manner to end their life. About two thirds of the counselees (63%) previously sought this help, primarily with a physician (38%), Right-to-Die-Netherlands (31%), a psychiatrist (25%), and/or the Euthanasia Expertise Centre (formerly known as End-of-Life Clinic; 14%). Counselees with primarily psychiatric suffering more often sought aid in dying with a psychiatrist (62%, 95% CI [46, 76]) than counselees with physical suffering (2%, 95% CI [0, 9]) and psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling (20%, 95% CI [9, 35]) and less often with Right-to-Die-Netherlands (14%, 95% CI [5, 27]) than counselees with physical suffering (41%, 95% CI [28, 55]; see Table 2).

Characteristics of Counseling Received by Counselees Passing Away Through MED

Almost half of the counselees who passed away through MED (46%) had one personal consult with the counselor, one third (33%) had two personal consults, and the remaining group (22%) three or more (see Table 3). In addition to the personal consults, other contacts such as per email or telephone were registered. One third of the counselees (37%) had four to six contact moments with the counselor, and half (47%) had seven or more. Almost half of the counselees (46%) passed away within 3 months after seeking counseling and another third (36%) within 1 year (see Table 3).

In almost all cases, general information about the foundation, moral support, counseling of mental aspects, practical information on the preparation for and performance of MED, information on others, and legal information was offered (88%–100%). Information on PAD was discussed with 70% of the counselees (see Table 3).

Two thirds (68%) of the counselees involved others in the counseling, most often their children (34%), their partner (23%), or other family members and/or friends (29%). Other professionals, among others physicians, were involved in few cases (7%). One fifth of the counselees (22%) did not involve others in the counseling, nor did they provide openness toward others about the counseling (see Table 3).

There were no significant differences between groups of varying underlying primary suffering in the duration, the number of contacts, and content of the counseling. Counselees with psychiatric suffering less often involved others (54%, 95% CI [43, 64]) than counselees with physical suffering (82%, 95% CI [74, 88]). When they involved others, less often it concerned their children (13%, 95% CI [5, 26]) when compared with counselees with physical suffering (39%, 95% CI [29, 51]) or psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling (47%, 95% CI [32, 63]). Counselees with physical suffering more often involved others and/or were open about the counseling they received toward others (90%, 95% CI [84, 95]) than counselees with psychiatric suffering (67%, 95% CI [56, 76]) or psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling (72%, 95% CI [61, 82]; see Table 3).

Discussion

Summary

The majority of counselees who have passed away through MED after receiving counseling to be able to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life have a terminal or serious disease and primarily suffer from physical or psychiatric problems. Almost all have a wish to end life at the start of counseling, and the majority wishes to end life within a year. Help with the wish to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life has also been sought with other caregivers or organizations by two thirds of the counselees. Half have requested their physician for PAD. Two thirds have involved others in the counseling, while one fifth neither have involved others nor were open toward others about the counseling. Counselees with psychiatric suffering are younger, more often have attempted suicide prior to counseling, and more often have expressed a wish to end life at the start of counseling (although their wish to end life was more often more than 1 year away) than counselees with physical suffering or counselees who mention psychological suffering or do not mention any suffering at the start of counseling.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first quantitative study to include such a large number of people who have passed away through MED after receiving counseling to be able to self-determine the timing and manner of your end of life. Also, it is the first quantitative study to obtain quantitative information from counselors who counsel counselees who wish to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life. The results are, however, not generalizable to all people in the Netherlands who have passed away through MED after receiving counseling because there are other organizations in the Netherlands that offer this counseling, which may have different approaches to offering assistance. Furthermore, information about the counselees has been collected through counselors. The available information is dependent on what counselees share with the counselor, which can cause an information bias. Furthermore, counselors assessed the primary underlying suffering and severity of disease based on this information. The anonymous data provided do not allow to link information to medical files or death registry files.

Who Passes Away Through MED?

This study shows that the majority of the people who have passed away through MED after receiving counseling to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life have a terminal or serious disease and primarily suffer from physical or psychiatric diseases. In a previous study, we found that 42% of the people seeking this counseling suffer from a terminal or serious disease (Hagens et al., 2014). In the current study, 65% of the people who ended their life after seeking this counseling had a terminal or serious disease. That seems to suggest that people who seek counseling to prevent possible future suffering less often (or less quickly) reach a situation in which they want to end their life.

Half of the people who have passed away through MED after receiving counseling have requested PAD. Chabot and Goedhart (2009) have also found that about half of the people passing away through MED (and VSED) have requested for PAD. This study shows that some patients do persist in their wish to end life after a denial of their request for PAD and do seek other ways to end life. Research has shown there can be miscommunication about the persistence of a wish to end life after a denied request for PAD (Pasman et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the results show that half of the counselees with an underlying medical disease have not requested for PAD. While having an underlying medical condition offers the opportunity to request for PAD (Regional Euthanasia Review Committees, 2018), this study supports the idea that people do not make use of this possibility. On one hand, this could reflect that there are people who regard ending your own life as their own responsibility instead of asking the physician for help and to take this responsibility (Hagens et al., 2017). On the other hand, it is also likely there are people who believe that they will not be able to obtain PAD and therefore do not request their physician for assistance (Hagens et al., 2017). For patients with psychiatric suffering, dementia, or an accumulation of problems of old age, the numbers of granted requests for PAD are low (Evenblij et al., 2019). These patient groups only form a small percentage of patients who receive PAD (Onwuteaka-Philipsen, et al., 2017), while they are well represented among the group of counselees who end life through MED after receiving counseling.

Finally, the study shows that counselees with psychiatric suffering differ from both counselees with physical suffering and counselees with psychological or no suffering at the start of counseling. They are, for example, younger and have attempted suicide more often. Offering assistance in dying under the Dutch Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Review Procedures Act to patients with psychiatric suffering is complex for physicians. Only 3% of the patients receiving PAD have a psychiatric disorder (Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., 2017). This is a result of matters such as the unpredictable course of psychiatric disorders, the possibility of spontaneous recovery, a large variety of treatment options, and the possibility that the wish to end life may be a symptom of the psychiatric disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Evenblij, 2019; NVvP Dutch Association for Psychiatry, 2019; Regional Euthanasia Review Committees, 2018). These matters will also be apparent in counseling counselees with psychiatric suffering and ask for the necessity to involve knowledgeable professionals. However, the focus on a recovery-oriented approach in mental health care may leave little room for patients with a wish to end life (Evenblij, 2019; Karlsson et al., 2018; Sowers et al., 2016). This might make it impossible to involve these mental health-care professionals. It might also lead people with psychiatric suffering to contact a counselor with whom they can discuss the wish to self-determine the timing and manner of your own life in an open manner (Hagens et al., 2019).

Counseling to Self-Determine the Timing and Manner of One’s End of Life

Regardless of the source of suffering, counseling in a delicate matter such as self-determining the timing and manner of one’s end of life asks for carefulness and patience. However, the results seem to suggest that the counseling trajectories are often short and consist of little personal contacts. Almost half of the counselees have only had one personal consult with the counselor before they passed away. Almost all the personal contacts are complemented with contacts by telephone or email.

The majority of the counselees who passed away through MED suffer from a terminal or serious disease. In certain cases, this might simply leave counselees with little time. It is unclear in which stage the counselor gets involved, as the counseling is often not the only assistance people seek. About half have requested their physician for assistance in dying, and almost two thirds has also sought help with the wish to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life from other caregivers or organizations. While for almost half of the counselees the counseling lasts less than 3 months, the data also suggest that the period in which counselees find or receive help with their wish to end life lasts longer for most than is suggested by the time frames in this study.

Findings on the counseling itself show that the counseling exists of more than just providing information on methods to end life in a nonviolent nonmutilating manner. Almost all counselees have received moral and mental support, legal information, and counseling about loved ones surrounding them. However, more detailed information about the content of the counseling and the role of counseling in the decision-making process is not available. This requires further research, for example, in-depth interviews with counselees and counselors.

About a quarter of the counselees (22%) have not involved others in the counseling and have not provided openness to others about the counseling. This might give cause for concern that these counselees are at risk for a lonely or isolated end of life, although contact with a counselor itself makes these counselees less isolated. The majority of counselees do involve others in the counseling. In most cases, this concerns family members and/or friends, while physicians are almost never involved in the counseling. This can be cause for concern as physicians can have a very important role in this process, especially concerning assessing competency, diagnosing diseases, and offering (or referring for) treatment.

Conclusion

The majority of people who pass away through MED after receiving counseling to be able to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life had a terminal or serious disease and primarily physical or psychiatric suffering. Half has requested for PAD, which on the one hand shows not all patients with a medical diagnosis ask for PAD and on the other hand shows that some patients with a denied request for PAD persist in their wish to end life. The physician hardly ever seems to be involved in the counseling, while they could have a valuable role in the process concerning assessing competency, diagnosing diseases, and offering (or referring for) treatment. As people will always keep falling outside the scope of the Dutch PAD law, it remains subject of debate if and which arrangements shall be made for people who still wish to self-determine the timing and manner of their end of life.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ome-10.1177_0030222820926771 for Cross-Sectional Research Into People Passing Away Through Self-Ingesting Self-Collected Lethal Medication After Receiving Demedicalized Assistance in Suicide by Martijn Hagens, H. Roeline W. Pasman and Bregje D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen in OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the board of Foundation De Einder and all the counselors facilitated by Foundation De Einder for distributing the data for this study.

Author Biographies

Martijn Hagens is a psychologist and junior researcher. His research interests include the voluntary termination of life, physician assistance in dying and demedicalised assistance in suicide.

H. Roeline W. Pasman is a sociologist and associate professor end of life research. Her research interests include (shared) decision making, advance care planning and wishes to die and she uses both qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Bregje D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen is a health scientist and professor end of life research. Her research themes are palliative care, advance care planning and euthanasia and other end of life decision.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Martijn Hagens https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9616-2685

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth edition).

- Bolt E. E., Hagens M., Willems D., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D. (2015). Primary care patients hastening death by voluntarily stopping eating and drinking. Annals of Family Medicine, 13(5), 421–428. 10.1370/afm.1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot B. E. (2001). Sterfwerk. De dramaturgie van zelfdoding in eigen kring [Interview study with relatives, doctors, and right-to-die activists about their involvement with a self-chosen death]. SUN.

- Chabot B. E. (2007). Auto-euthanasie. Verborgen stervenswegen in gesprek met naasten [A humane self-chosen death. Hidden dying trajectories in conversation with proxies]. Bert Bakker.

- Chabot B. E., Goedhart A. (2009). A survey of self-directed dying attended by proxies in the Dutch population. Social Science and Medicine, 68(10), 1745–1751. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenblij K. (2019). End-of-life care for patients suffering from a psychiatric disorder. Amsterdam UMC Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Evenblij K., Pasman H. R. W., Van der Heide A., Hoekstra T., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D. (2019). Factors associated with requesting and receiving euthanasia: A nationwide mortality follow-back study with a focus on patients with psychiatric disorders, dementia, or an accumulation of health problems related to old age. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 39. 10.1186/s12916-019-1276-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foundation De Einder. (2016). Brochure. Een waardig levenseinde onder eigen regie [Brochure. A dignified death under own autonomy]. Stichting De Einder. https://www.deeinder.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/De-Einder-brochure-Een-waardig-levenseinde-in-eigen-regie.pdf

- Hagens M., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D., Pasman H. R. W. (2017). Trajectories to seeking demedicalised assistance in suicide: A qualitative in-depth interview study. Journal of Medical Ethics, 43(8), 543–548. 10.1136/medethics-2016-103660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagens M., Pasman H. R. W., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D. (2014). Cross-sectional research into counselling for non-physician assisted suicide: Who asks for it and what happens? BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 455. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagens M., Snijdewind M. C., Evenblij K., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D., Pasman H. R. W. (2019). Experiences with counselling to people who wish to be able to self-determine the timing and manner of one’s own end of life: A qualitative in-depth interview study. Journal of Medical Ethics. Advance online publication. 10.1136/medethics-2019-105564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Karlsson P., Helgesson G., Titelman D., Sjöstrand M., Juth N. (2018). Skepticism towards the Swedish vision zero for suicide: Interviews with 12 psychiatrists. BMC Medical Ethics, 19, 26. 10.1186/s12910-018-0265-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNMG Royal Dutch Medical Association, & V&VN Dutch Nurses’ Association. (2014). Zorg voor mensen die bewust afzien van eten en drinken om het levenseinde te bespoedigen [Care for people that voluntarily refuse food and fluid to end life]. https://www.knmg.nl/advies-richtlijnen/afzien-van-eten-en-drinken-om-het-levenseinde-te-bespoedigen.htm

- NVvP Dutch Association for Psychiatry. (2019). Richtlijn levensbeëindiging op verzoek bij patiënten met een psychische stoornis [Guideline termination of life on request with patients with a psychic disorder]. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/levensbeeindiging_op_verzoek_psychiatrie/startpagina_-_levensbe_indiging_op_verzoek.html

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B., Legemaate, J., van der Heide, A., van Delden, H., Evenblij, K., El Hammoud, I., Pasman, R., Ploem, C., Pronk, R., van de Vathorst, S., & Willems, D. (2017). Derde evaluatie Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding [Third Evaluation of the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act]. ZonMw. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasman H. R. W., Willems D. L., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D. (2013). What happens after a request for euthanasia is refused? Qualitative interviews with patients, relatives and physicians. Patient Education and Counseling, 92(3), 313–318. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regional Euthanasia Review Committees. (2018). Euthanasia Code 2018. https://english.euthanasiecommissie.nl/the-committees/documents/publications/euthanasia-code/euthanasia-code-2018/euthanasia-code-2018/euthanasia-code-2018

- Rurup M. L., Deeg D. J. H., Poppelaars J. L., Kerkhof A. J. F. M., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D. (2011). Wishes to die in older people. A quantitative study of prevalence and associated factors. Crisis, 32(4), 194–203. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rurup M. L., Pasman H. R. W., Goedhart J., Deeg D. J. H., Kerkhof A. J. F. M., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D. (2011). Understanding why older people develop a wish to die. A qualitative interview study. Crisis, 32(4), 204–216. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers W., Primm A., Cohen D., Pettis J., Thompson K. (2016). Transforming psychiatry: A curriculum on recovery-oriented care. Academic Psychiatry, 40, 461–467. 10.1007/s40596-015-0445-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Netherlands. (2020. a, January 27). Deceased; important causes of death (short list), age, gender. https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/7052_95/table?ts=1580120608140

- Statistics Netherlands. (2020. b, January 27). Deceased; suicide (inhabitants), various characteristics. https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/7022gza/table?ts=1580120111120

- ten Have M., van Dorsselaer S., Tuithof M., de Graaf R. (2011). Nieuwe gegevens over suïcidaliteit in de bevolking. Resultaten van de ‘Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2’ (NEMESIS-2) [New data about suicidality in the population. Results of the ‘Dutch Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2’ (NEMESIS-2)]. Trimbos-Institute. https://assets-sites.trimbos.nl/docs/3803da0d-43b3-4eee-9e37-f6bcdb68f43c.pdf [Google Scholar]

- The Netherlands Case Law. (1995). Behulpzaamheid bij zelfdoding. Arrest Mulder-Meiss, Uitspraak Hoge Raad, 5 December 1995, NJ, 1996, 322 [Assistance in suicide]. https://www.navigator.nl/document/id3419951205100400nj1996322dosred/ecli-nl-hr-1995-zd0309-nj-1996-3§-euthanasie-behulpzaam-zijn-294-sr-moet-worden-uitgelegd-cfm-algemeen-spraakgebruik-beroep-op-noodtoestand-inz-294-sr-toerei

- van Wijngaarden E., Leget C., Goosensen A. (2014). Experiences and motivations underlying wishes to die in older people who are tired of living: A research area in its infancy. OMEGA, 69(2), 191–216. 10.2190/OM.69.2.f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink T. (2008). Zelf over het levenseinde beschikken – de praktijk bekeken [Self-determination at the end of life. A view at practical experiences]. Damon.

- Vink T. (2013). Zelfeuthanasie, Een zelfbezorgde goede dood onder eigen regie [Self-euthanasia. A self-delivered good death under own autonomy]. Damon.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ome-10.1177_0030222820926771 for Cross-Sectional Research Into People Passing Away Through Self-Ingesting Self-Collected Lethal Medication After Receiving Demedicalized Assistance in Suicide by Martijn Hagens, H. Roeline W. Pasman and Bregje D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen in OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying