Abstract

Background:

Vaccination has been increasingly promoted to help control epidemic and endemic typhoid fever in high-incidence areas. Despite growing recognition that typhoid incidence in some areas of sub-Saharan Africa is similar to high-incidence areas of Asia, no large-scale typhoid vaccination campaigns have been conducted there. We performed an economic evaluation of a hypothetical one-time, fixed-post typhoid vaccination campaign in Kasese, a rural district in Uganda where a large, multi-year outbreak of typhoid fever has been reported.

Methods:

We used medical cost and epidemiological data retrieved on-site and campaign costs from previous fixed-post vaccination campaigns in Kasese to account for costs from a public sector health care delivery perspective. We calculated program costs and averted disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and medical costs as a result of vaccination, to calculate the cost of the intervention per DALY and case averted.

Results:

Over the 3 years of projected vaccine efficacy, a one-time vaccination campaign was estimated to avert 1768 (90%CI: 684–4431) typhoid fever cases per year and a total of 3868 (90%CI: 1353–9807) DALYs over the duration of the immunity conferred by the vaccine. The cost of the intervention per DALY averted was US$ 484 (90%CI: 18–1292) and per case averted US$ 341 (90%CI: 13–883).

Conclusion:

We estimated the vaccination campaign in this setting to be highly cost-effective, according to WHO’s cost-effective guidelines. Results may be applicable to other African settings with similar high disease incidence estimates.

Keywords: Typhoid, Typhoid vaccination, Uganda, Cost-effectiveness

1. Introduction

Typhoid fever is a systemic infection caused by the bacterium Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (Salmonella Typhi) and is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. Annually, Salmonella Typhi causes an estimated 27 million illnesses and 270,000 deaths worldwide [1]. Until recently, most infections were thought to occur in Asia [2]; however, new reports suggest that parts of sub-Saharan Africa are also highly affected [1]. High rates of endemic typhoid were documented in an urban population in Kenya during 2007–2009 [3]; since 2008, severe typhoid fever outbreaks have been reported in rural areas in Malawi [4], Uganda [5], and in urban areas in Zimbabwe and Zambia [6,7].

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends typhoid fever vaccination for controlling endemic and epidemic typhoid fever [8]. The Vi capsular polysaccharide (ViCPS) vaccine is a single dose injectable subunit vaccine that showed high efficacy and effectiveness, with protection lasting at least 3 years in large scale trials [9]. One ViCPS vaccine manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur is licensed in many countries for persons 2 years of age and older and is WHO pre-qualified. The ViCPS vaccine has been widely adopted for programmatic use, to control outbreaks in a school in China, and in a preemptive mass vaccination campaign in Fiji following a tropical cyclone [8,10–13].

Cost-effectiveness studies in endemic settings in Asia support the value of typhoid vaccination as a prevention and control measure, but they are not necessarily applicable in epidemic settings in Africa, where typhoid affects a wider age range and programmatic costs may differ widely given differences in health systems [4,5,14,15]. A large outbreak of typhoid fever began in Kasese District (see Appendix I), Uganda in 2008 and continued through 2011, with cases still being reported as recently as October 2012 [16] [C.D.C.: Unpublished report, 2012]. We analyzed the cost-effectiveness of a hypothetical one-time mass typhoid vaccination campaign in Kasese District, using published data from case finding activities to estimate incidence, a community survey to characterize health care seeking behavior, and medical costs retrieved on-site to estimate treatment costs.

2. Methods

2.1. Model

We compared the costs and benefits of a one-time fixed-post typhoid vaccination campaign using the single dose ViCPS vaccine with the baseline alternative of “no vaccine”, over the period when the vaccine confers protection (3 years). Benefits (in disability adjusted life years – DALYs, and averted medical costs) were measured and discounted over 3 years, the time the vaccine was assumed to confer protection against typhoid. Costs were due to the vaccination campaign and occurred only at the beginning of the evaluation period. We applied standard cost effectiveness methodologies to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of immunization programs, including a standard discount rate (3%) and uniform age weights [17,18] (see Appendix II).

We first measured burden of disease in DALYs, with and without the vaccination campaign. Disability adjusted life years incorporates both reductions in typhoid morbidity (years of life lost to disability, YLD) and typhoid mortality (years of life lost, YLL) (Appendix II). The benefits from the vaccination campaign, or DALYs averted, consist of the differences between the burden of disease with, and without the vaccination campaign. Although the vaccine may confer herd immunity and therefore positive externalities, there is little data on the magnitude of such effects, and so we used a static model to generate a conservative estimate [9,17].

We measured the average cost effectiveness ratio by dividing the program’s costs by the program’s benefit in averted DALYs, according to a public sector health care delivery perspective. This perspective was used since there is little information on patient time lost. The denominator of the average cost-effectiveness ratio thus consists on the number of averted DALYs over the three years of immunity conferred by the vaccine, while the numerator of the average cost effectiveness ratio is the difference between the one-time costs of the vaccination program and the averted medical costs borne by the public sector over the three years the vaccine confers immunity.

The averted medical costs borne by the public sector consist of the averted costs of typhoid related outpatient visits and hospitalizations. To estimate averted medical costs we calculated the epidemiological burden of disease (expected typhoid cases), the burden expected to be averted by the vaccination campaign, and then multiplied the latter by the expected case cost. We assumed that cases resulting in death did not have additional medical costs.

2.2. Epidemiological parameters

To estimate incidence of typhoid in Kasese and in the absence of routine, laboratory-enhanced surveillance for typhoid fever, we used published data on incidence of intestinal perforation (IP) per 5 year age-group in Kasese District [5]. Intestinal perforation is a serious complication of typhoid fever that is known to occur in 1–8% of cases [5]. We thus considered the IP rate for typhoid fever patients to be 1–8% across all age-groups, and calculated the total number of typhoid cases per 5 year age-groups taking into account Kasese’s projected population for 2012 [5,19] [Unpublished Data: District Planner Kasese – Kasese Populations, 2008].

From estimated cases, we calculated the total burden of deaths and IP. To calculate number of deaths due to typhoid fever, typical values were used for the case fatality rate for typhoid patients without IP (0.6–2.1% across all age-groups) [2,20]. For typhoid patients with IP the case fatality rate considered was 17–22% across all age-groups, according to a recent review of the evidence [21]. Average vaccine effectiveness over the duration of immunity of the vaccine (3 years) was considered to vary between 30% and 70% [22].

To assess the probabilities of different medical outcomes and characterize health care seeking behavior, we used a community assessment survey administered in northern Kasese District (Busongora North health subdistrict) and published evidence. Health outcomes included number of cases with and without IP, and number of early deaths. Health care seeking behavior included patients cared for at home, hospitalizations (for IP and non IP patients), and outpatient treatment. Length of illness (4–7 days for patients without IP, and 17–24 days for patients with IP) was taken from a recent review and previous published evidence for typhoid [14,21] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inputs for base case analysis (inputs, source, and assumptions for sensitivity analysis).

| Item | Point-estimate | Distribution and range | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood of IP given infection | – | Uniform 0.01–0.08 | [5] |

| Case fatality rate | |||

| For patients without IP | – | Uniform 0.006–0.021 | [20] |

| For patients with IP | – | Uniform 0.17–0.22 | [21] |

| Length of illness | |||

| For patients without IP | – | Uniform 4–7 | [14] |

| For patients with IP | – | Uniform 17–24 | [21] |

| Likelihood of seeking medical care given IPb | |||

| Likelihood of outpatient visit, followed by no hospitalization | 0.18 | a | CAS |

| Likelihood of outpatient visit, followed by hospitalization | 0.82 | Uniform 0.8–1 | CAS |

| Likelihood of seeking medical care given no IPb | |||

| Likelihood of outpatient visit, followed by no hospitalization | 0.46 | Uniform 0.43–0.48 | CAS |

| Likelihood of outpatient visit, followed by hospitalization | 0.32 | Uniform 0.28–0.33 | CAS |

CAS: community assessment survey; IP: intestinal perforation; incidence rate calculated from intestinal perforation rate.

In the Monte Carlo simulation, modeled as 1-Likelihood of outpatient visit, followed by hospitalization.

Confidence intervals obtained through the CAS.

2.3. Case costs

We estimated the direct medical costs of three different health care scenarios: (i) outpatient treatment; (ii) hospitalization of an IP patient; and, (iii) hospitalization of a non-IP patient. The costs of medicines, supplies, and medical fees for each scenario were determined through a two-step process. First, a surgeon at Kilembe Mines Hospital, a private-not-for-profit hospital in Kasese where surgical procedures to repair IP were performed during 2008–2011, created a list of medications (including dosage and duration of treatment) and medical supplies used for a typical patient in each treatment situation. Itemized costs were then determined based on the Uganda National Medical Stores catalog (2011). Total costs were estimated in the local currency (Ugandan shillings), inflated to 2014 Uganda shillings using the “Health, Entertainment & Others” component of the Ugandan Consumer Price Index and then converted to 2014 US$, using the exchange rate published by the U.S. Treasury Department [23–25]. The cost of care for patients that did not visit a provider and were cared for at home was considered to be 0, from a public sector health care delivery perspective.

The cost of an outpatient visit included the cost of antimicrobials, antimalarials, and antipyretics (i.e. paracetamol), a consultation fee that takes into account medical labor, and a laboratory fee. The cost of antimalarials was included because typhoid and malaria have similar clinical presentations, and health care workers reported that typhoid patients were likely to be treated for both illnesses in malaria endemic areas including Kasese District.

The cost of a 7-day inpatient hospital stay for typhoid patients without IP included medications, intravenous fluids, medical supplies, a consultation fee covering medical labor, a laboratory fee, and daily bed costs. For IP associated hospitalizations, the cost of associated surgery was also included. Additionally, medical chart abstractions showed that 15% of hospitalized patients undergoing surgery for IP were treated with a temporary ileostomy or colostomy that was later surgically repaired. Accordingly, the final medical costs for hospitalized patients undergoing IP surgery was a weighted average between the costs of patients that underwent only one surgery and patients that underwent two. Because most hospitalized patients reported seeking care from at least one health facility before going to the hospital, the cost of one outpatient visit was added to the treatment costs of all hospitalized typhoid patients.

The estimated medical costs reflect standardized care; however, medical costs vary substantially with individual illness because of factors including the number of outpatient visits required, the duration of hospitalization, and additional surgical interventions required for complications. To take into account such variations, outcome costs were assumed to follow a truncated (at the 10th and 90th percentiles) lognormal distribution (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cost of different medical care outcomes.

| Item | Point estimatea |

|---|---|

| Hospitalization for patient with Intestinal Perforation | 155.6 |

| Hospitalization for patient without Intestinal Perforation | 58.1 |

| Outpatient care | 4.3 |

Costs in 2014 US$. Costs assumed to have a lognormal distribution with (standard deviation) = μ(mean)/10 (where μ corresponds to the tabulated values), and were truncated at the 10th and 90th percentiles. Costs obtained via interview with medical superintendent at Kilembe Mines Hospital in Kasese District.

2.4. Vaccination Campaign Cost

Total direct costs of a one-time fixed-post community vaccination campaign targeting all persons ≥2 years old were estimated from a public sector health care delivery perspective (Table 3, Appendix II). The direct costs are the sum of the costs of campaign preparation (community organization and sensitization, cold chain maintenance, training, labor, and transportation of campaign workers and vaccine) and vaccine administration. Injection materials and labor costs were assumed to be directly proportional to the costs of a 2012 measles vaccination campaign in Kasese. Again, costs were inflated from 2012 to 2014 Uganda shillings using the Consumer Price Index (All Items) published by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, and then converted to 2014 US$ using the exchange rate published by the Treasury Department [23,24].

Table 3.

Vaccine effectiveness, duration of protection, vaccine costs, and DALY weights.

| Item | Point estimate | Distribution and range | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine effectiveness (base case) | 0.55 | Uniform (0.30–0.70) | [22] |

| Vaccine effectiveness (age dependent vaccine effectiveness for SA) | |||

| <5 years old | 0.80 | Uniform (0.53–0.91) | [9] |

| Between 5 and 15 years old | 0.56 | Uniform (0.18–0.77) | [9] |

| >15 years old | 0.46 | Uniform (0.00–0.79) | [9] |

| Vaccine duration | 3 years | [14] | |

| DALY weights | 0.27 | Uniform (0.075–0.471) | [14] |

| Kasese population estimates | 747,800 | ||

| Campaign type | Fixed post | ||

| Operational costs per dosea, Labor costs, transportation costs, injection materials | 0.15 | Uniform (0.13–0.16) | b |

| Vaccine cost per dosea | – | Uniform (0.5–3.4) | [11]c |

| Vaccine coverage | – | Uniform (0.60–0.75) | c |

SA: sensitivity analysis.

Costs are in 2014 US$.

Data from 2012 Kasese Measles Immunization Campaign. The 2012 Kasese Measles Immunization Campaign covered children between 1 and 15 years old so we multiplied total cost of injection site materials and labor (public sector financial perspective) by: share of population >2 in Uganda/share of total population between 1 and 15 years old in Uganda. Detailed population estimates were not available for Kasese. The interval corresponds to multiplying the different factor costs by 0.9 and 1.1.

Personal Communication, K. Date, C.D.C., Atlanta.

The vaccine’s purchase price per dose was varied between US$ 0.5 and 3.4 [11] [Personal Communication, K. Date, C.D.C., Atlanta]. Although 98% of heads of households surveyed in the community assessment reported that they would use a free typhoid vaccine to protect their family from typhoid fever, we assumed a more conservative vaccination coverage rate that varied between 60% and 75% [Personal Communication, K. Date, C.D.C., Atlanta]. The vaccine wastage rate was estimated at 10%, in accordance with values obtained for previous vaccination campaigns [26,27]. Consistent with the public sector health care delivery perspective, vaccinees’ lost productivity and transportation costs associated with obtaining the vaccines were not included in the estimated campaign costs.

2.5. Sensitivity analysis

We attributed to each parameter a probability distribution (Tables 1–3), and obtained confidence intervals for the base case through Monte Carlo simulation (using 200,000 draws from the probability distributions and Latin hypercube sampling techniques).

Since the analysis was particularly sensitive to incidence estimates, and given uncertainty surrounding endemic incidence in this area afflicted by a typhoid outbreak, we analyzed cost-effectiveness results as a function of incidence alone. We also estimated the cost effectiveness of a mass typhoid vaccination campaign in case the vaccine was donated (vaccine purchase cost of zero), a plausible scenario given a vaccine donation offer [Personal Communication, Deschamps I., Sanofi Pasteur]; and explored the impact of age dependent vaccine effectiveness [9].

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological parameters

Based on an IP rate of 1–8% and given IP incidence previously published for this outbreak [5], the estimated incidence of typhoid varied between 296 and 2368 cases per 100,000 individuals across all age groups. The estimated incidence rate was highest among those between 15 and 19 years old, followed by those between 10 and 14 years old.

To characterize health care seeking behavior, the community assessment survey was completed by interviewing the heads of 320 randomly selected households (median size: 6 persons) in 40 randomly selected rural villages [5]. A typhoid case was defined as “illness with onset between December 27, 2007 and July 30, 2009 in a person with fever, abdominal pain, and ≥1 of the following symptoms: gastrointestinal complaints (i.e., vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation), general body weakness, joint pain, headache, no response to antimalarial medications, or IP” [5]. There were 173 cases that met the case definition among the 2173 persons living in the study households [5] [Unpublished Report: C.D.C., Outbreak of typhoid fever, Kasese, Uganda]. All cases with IP sought care at a health facility, and 82% (9/11) were hospitalized (IP status was not known for 4 patients). Only 50 patients without IP were hospitalized (32%), and 35 patients without IP did not seek care. Thus, 46% of patients without IP received outpatient treatment only (Table 1).

3.2. Case costs

The cost of an outpatient visit totaled US$ 4.3; a 7-day inpatient hospital stay for typhoid patients without IP was estimated at US$ 53.8. Patients undergoing surgery for IP had a higher estimated cost of US$ 144.7. Fifteen percent of hospitalized patients undergoing surgery for IP were treated with a temporary ileostomy or colostomy that was later surgically repaired at an estimated cost of US$ 44.0 (CDC, unpublished data). Therefore, the case cost for each patient receiving outpatient care only was US$ 4.3, while the case costs for hospitalized patients was US$ 58.1 for individuals without IP, and US$ 155.6 for individuals with IP (Table 2).

3.3. Program costs, burden of disease and estimated impact of the vaccination campaign

The operational costs of the vaccination campaign were US$ 0.15 per vaccinee (Table 3). Considering an IP rate of 1–8% across all age-groups (corresponding to an incidence rate of 296–2368 cases per 100,000 individuals), there were 5261 (90%CI: 2315–13,119) new typhoid cases per year, resulting in 237 (90%CI: 48–660) IP cases, and 114 (90%CI: 39–292) deaths among Kasese individuals. Per year, typhoid in Kasese is expected to cause 2774 (90%CI: 940–7087) YLL, and 23 (90%CI: 9–58) YLD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Baseline burden, averted burden, averted cost, program cost, and dollars spent per DALY averted.

| Item | Valuea and 90% confidence interval |

|---|---|

| Expected case cost | 25.3 (20.7–30.1) |

| Burden (no vaccination) per year (total cases), including | 5261 (2315–13119) |

| Total cases among individuals <5 years old | 170 (75–425) |

| Total cases among individuals ≥5 years old & < 15 years old | 1810 (797–4515) |

| Intestinal perforations | 237 (48–660) |

| Deaths | 114 (39–292) |

| Averted burden per year (total cases), including: | 1768 (684–4431) |

| Averted cases among individuals <5 years oldb | 28 (10–71) |

| Averted cases among individuals ≥5 years old & <15 years old | 618 (218–1566) |

| Intestinal perforations | 88 (34–221) |

| Deaths | 40 (14–101) |

| DALYs averted over duration | 3868 (1353–9807) |

| Averted medical costs over duration (thousands of dollars) | 391 (146–984) |

| Program costs (thousands of dollars) | 1590 (595–2585) |

| Net costs per DALY averted | 484 (18–1292) |

| Net costs per case averted | 341 (13–883) |

| Program costs (thousands of dollars)/vac. dose donation | 103 (93–112 |

| Net costs per DALY averted | CS (CS–CS) |

| Net costs per case averted | CS (CS–CS) |

| GDP per capitac | 598 |

| Threshold to be considered “highly cost-effective” | 598 |

| Threshold to be considered “cost-effective” | 1794 |

GDP: Gross Domestic Product, CS: Cost Saving.

All costs in 2014 US$.

The vaccine was considered to avert cases only for those >2 years old.

From Ref. [28].

A one-time vaccination campaign would avert a total of 5300 typhoid cases (90%CI: 2067–13,247); 265 IP cases (90%CI: 103–662); and 120 deaths (90%CI: 42–303) over the 3 years of projected vaccine protection. The vaccine would avert on average 8 (90%CI: 3–20) YLD per year, and 1320 (90%CI: 461–3347) YLL per year; and, over the 3-year duration of protection, a total of 3868 DALYs (90%CI: 1353–9807). The total averted medical costs due to the vaccination campaign, using a 3% discount rate, varied between US$ 146,000 and 984,000 (mean: US$ 391,000). The cost of the intervention per DALY averted was US$ 484 (90%CI: 18–1292), and per case averted US$ 341 (90%CI: 13–883) (Table 4).

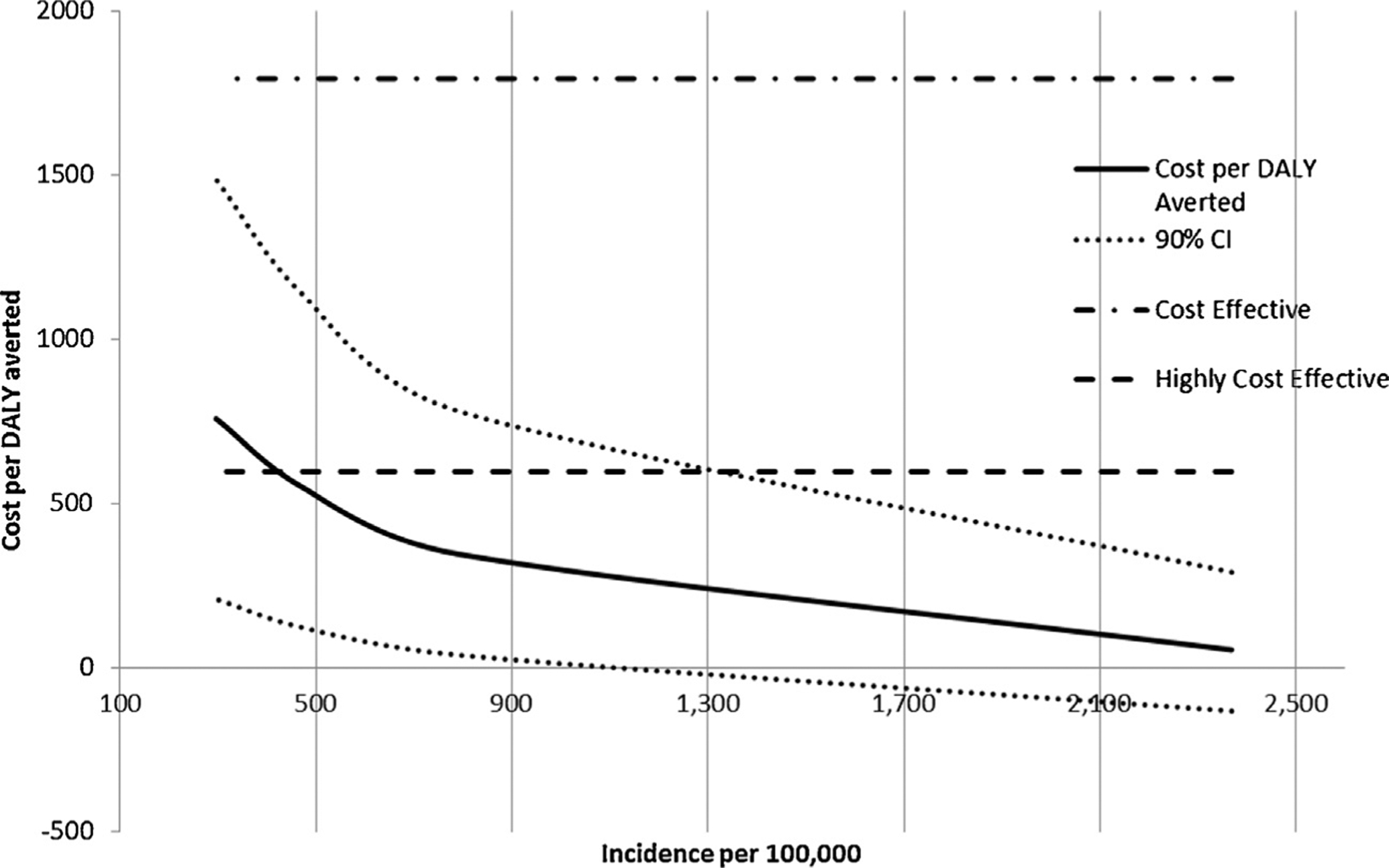

3.4. Sensitivity analysis

Dollars spent per DALY averted decreased with the incidence rate, with typhoid vaccination meeting the criteria for a highly cost-effective intervention when the incidence rate was above 500 cases per 100,000 individuals per year (Fig. 1). If the vaccine was donated, the vaccination campaign would be a cost-saving intervention, when evaluated from a public sector health care delivery perspective (Table 4). Using age dependent vaccine effectiveness slightly increased the average cost per DALY and case averted and also widened the 90%CI (Table 5).

Fig. 1.

Cost per DALY averted as a function of the incidence rate, with 90% confidence intervals (dotted lines), and WHO’s required thresholds for interventions to be considered cost effective or highly cost effective (horizontal lines).

Table 5.

Results of sensitivity analyses considering age dependent vaccine effectiveness.

| Item | Valuea and 90% confidence interval |

|---|---|

| Averted burden per year (total cases), including | 1514 (396–4041) |

| Averted cases among individuals <5 years oldb | 40 (16–101) |

| Averted cases among individuals ≥5 years old & <15 years old | 588 (159–1572) |

| Intestinal perforations | 76 (20–202) |

| Deaths | 34 (8–92) |

| DALYs averted over duration | 3316 (814–8953) |

| No vaccine dose donation | |

| Net costs per DALY averted | 693 (32–2057) |

| Net costs per case averted | 489 (23–1424) |

| Vaccine dose donation | |

| Program Costs | 103 (93–112) |

| Net costs per DALY averted | CS (CS–19) |

| Net costs per case averted | CS (CS–14) |

CS: Cost Saving

All costs in 2014 US$.

The vaccine was considered to avert cases only for those >2 years old.

4. Discussion

To the best our knowledge, our study is the first cost-effectiveness evaluation of a hypothetical typhoid vaccination campaign in sub-Saharan Africa. We found that a one-time fixed-post community vaccination campaign in response to a severe typhoid fever epidemic in Kasese District, Uganda, would cost US$ 484 (90%CI: 18–1292) per DALY averted, and US$ 341 (90%CI: 13–883) per case averted, consistent with that which was estimated for highly endemic Asian settings [13]. In Uganda the Gross Domestic Product per capita is US$ 598 and so, based on WHO standard measures for cost-effectiveness, this intervention would be classified as highly cost-effective [28].

These findings should be considered with some qualifiers. Since we estimated the epidemiological burden of disease for a region afflicted by a typhoid outbreak, our calculations reflect the cost-effectiveness of a typhoid vaccination campaign in Kasese had it been conducted shortly after the outbreak was identified. However, the incidence of disease used in the present analyses is similar to other values published for East Africa and South Asia, making the analyses generalizable to other high incidence countries [20]. Theoretically, some of the impact of vaccination may be offset by acquired immunity in the absence of vaccination, a factor we did not account for in this analysis. Notably, typhoid incidence in areas of Kasese remained high during the three year period from 2009 to 2011, suggesting that, in this setting, acquired immunity would not substantially offset or negate the benefits of vaccination.

In addition, our static model did not take into account that after the three years of immunity conferred by the vaccine, incidence of typhoid may rebound [29]. This occurs as the number of non-naturally immunized individuals builds up during the years the vaccine provides immunity. As a result, these estimates should be interpreted as particular to the three years following the one time vaccination campaign, and the relatively short duration of protection given by vaccination underscores the need to consider long-term interventions, such as improved water sources and sanitation systems [29].

To note, the estimated burden of IP was higher than the published values in Ref. [5] (that is, after estimating incidence by assuming a 1–8% IP rate, we estimated a potentially higher burden of IP using Monte Carlo simulation). This conveys uncertainty regarding underreporting ratios (the incidence of typhoid in the community survey was much higher than the one assumed here), and was thus helpful in generating credibly wide confidence intervals.

We used a conservative perspective when accounting for the costs averted and benefits gained due the vaccination campaign, to generate conservative estimates of the cost per DALY averted. Notably, in this poor, rural area of Uganda, transportation to clinics can cost as much as outpatient visits, and days lost to illness impact subsistence farming and food availability. The potential of typhoid to cause catastrophic health expenditures is real, but has not been featured in this analysis. Additionally, we did not take into account the higher disability weights due to IP, given lack of evidence, and the potentially beneficial herd immunity effects of vaccination.

In conclusion, a one-time fixed-post typhoid vaccination campaign in Kasese District, Uganda, was estimated to be a highly cost-effective intervention from the public sector health care delivery perspective. While we have not addressed the efficiency of allocating resources to typhoid vaccination as compared to other public health measures, the use of published estimates for epidemiological parameters makes this study applicable to similar African settings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff in the Global Disease Detection Operations Center (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC), for logistical and technical support collecting cost data. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Annet Kiskaye (World Health Organization – Expanded Programme on Immunizations), Stephen Bagonza (Kasese District Health Office), and Sabiti Johnson (Bundibugyo District Health Office) for providing invaluable information about immunization campaigns conducted in Uganda. From the Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases (CDC), we thank Dr. Karen Neil for providing additional insight on published surveillance and community survey findings, and Drs. Janell Routh and Jolene H. Nakao for assisting with field activities. This work would not have been possible without support from numerous staff at the Uganda Ministry of Health and Kasese District Health Office.

Funding

Support for capturing cost-retrieval data in this study was provided by the CDC Global Disease Detection Operations Center Outbreak Response Contingency Fund.

Appendix I. The setting: Kasese, Uganda

Kasese is a rural district in western Uganda that borders the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The district had an estimated population of 747,800 people in 2012, half of whom were <15 years of age [23]. Kasese residents seek healthcare from hospitals and health centers operated by the Uganda Ministry of Health and non-profit organizations; health clinics run by private practitioners; pharmacies and drug shops; traditional healers; and herbalists. Within Kasese, there are 3 hospitals, 95 health centers, and 21 private health clinics [Personal communication, S. Bakulirahi, Kasese District Biostatistician]. The health system in Uganda follows a tiered referral system in which the lowest level health centers run outpatient clinics that treat common, uncomplicated illnesses and offer antenatal services, and the highest level facilities are hospitals with outpatient clinics, surgical and in-patient services.

Vaccination campaigns have historically been used in Kasese district to control epidemic diseases such as measles and polio, and district health officials and community survey results indicate that vaccination is highly acceptable in the population [5,30]. A fixed-post measles campaign estimated to cover 70% of the target population occurred in Kasese in 2012; vaccination costs were $0.5 per dose [Personal Communication, K. Date, C.D.C., Atlanta].

Appendix II. The model

| (1) |

where for each age group, and as used previously [14,18,31,32]:

| (2) |

| (3) |

and CFR stands for case fatality rate, Eff for vaccine effectiveness, VC for vaccine coverage, N for number of individuals targeted for the vaccination campaign, I for incidence of the disease, length for duration of illness (in years), and LE for life expectancy. In the current analysis, I, VE (and LE) vary per age group, but VC and CFR are considered to be the same across all age groups. We distinguished between the CFR of patients with and without intestinal perforation (IP), and considered different illness durations depending on IP status, and so the final formulae are:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where IP is the share of patients developing Intestinal Perforation, CFRnoIP is the CFR for individuals with no IP, CFRIP is the CFR for IP patients, lenghtnoIP is the duration of illness for individuals with no IP, and lengthIP is the duration of illness for individuals with IP. In our calculations, we considered 15 age-groups for which we had detailed estimates on typhoid incidence and life expectancy (<1, 1–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65+), and that the average age at death for those 65+ was 72.5 (and so the life expectancy for those 65 was taken from WHO’s life table for age-group 70–74) [5,32]. The number of people in each age group was derived using population projections for Kasese in 2012 [Unpublished Data: District Planner Kasese – Kasese Populations, 2008], and the Ugandan population pyramid [19]. Averted cases were only counted among those >2 years old.

We finally modeled the averted burden due to a one time vaccination campaign in year one, throughout the duration (Dur) of the vaccine as the discounted sum of the averted DALYs per year across all age-groups:

| (6) |

B.1. Vaccination operational campaign costs

We multiplied total costs of injection materials and labor for the Kasese measles campaign by a multiplier equal to the ratio between projected vaccination coverage in Kasese (all above 2, for 2012) and the target population for the measles campaign (population between 1 and 15 years old) in Kasese [19]. To obtain lower and upper bounds we multiplied each factor by 0.9 and 1.1, respectively.

Footnotes

This work has not been presented in an open scientific conference before. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the agency.

Conflicts of interest: The authors do not have a commercial association or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Buckle GC, Walker CL, Black RE. Typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever: systematic review to estimate global morbidity and mortality for 2010. J Glob Health 2012;2(1):10401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Crump JA, Luby SP, Mintz ED. The global burden of typhoid fever. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82(5):346–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Breiman RF, Cosmas L, Njuguna H, Audi A, Olack B, Ochieng JB, et al. Population-based incidence of typhoid fever in an urban informal settlement and a rural area in Kenya: implications for typhoid vaccine use in Africa. PLoS ONE 2012;7(1):e29119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lutterloh E, Likaka A, Sejvar J, Manda R, Naiene J, Monroe SS, et al. Multidrug-resistant typhoid fever with neurologic findings on the Malawi-Mozambique border. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54(8):1100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Neil KP, Sodha SV, Lukwago L, O-Tipo S, Mikoleit M, Simington SD, et al. A large outbreak of typhoid fever associated with a high rate of intestinal perforation in Kasese District, Uganda, 2008–2009. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54(8):1091–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Slayton RB, Date KA, Mintz ED. Vaccination for typhoid fever in Sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2013;9(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Imanishi M, Kweza PF, Slayton RB, Urayai T, Ziro O, Mushayi W, et al. Household water treatment uptake during a public health response to a large typhoid fever outbreak in Harare, Zimbabwe. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90(5):945–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bhutta Z, Chaignat C, Clemens J, Favorov M, Ivanoff B, Klugman K, et al. Background paper on vaccination against typhoid fever using new-generation vaccines. WHO SAGE; 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/SAGE_Background_paper_typhoid_newVaccines.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sur D, Ochiai RL, Bhattacharya SK, Ganguly NK, Ali M, Manna B, et al. A cluster-randomized effectiveness trial of Vi typhoid vaccine in India. N Engl J Med 2009;361(4):335–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Thiem VD, Danovaro-Holliday M, Canh DG, Son ND, Hoa NT, Thuy DTD, et al. The feasibility of a school-based VI polysaccharide vaccine mass immunization campaign in Hue City, central Vietnam: streamlining a typhoid fever preventive strategy. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2006;37(3):515–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dewan DK. Community based typhoid vaccination program in New Delhi, India. In: 8th international conference: typhoid fever and other invasive salmonel-loses. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yang H, Wu C, Xie G, Gu Q, Wang B, Wang L, et al. Efficacy trial of Vi polysaccharide vaccine against typhoid fever in south-western China. Bull World Health Organ 2001;79(7):625–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Scobie HM, Nilles E, Kama M, Kool JL, Mintz E, Wannemuehler KA, et al. Impact of a targeted typhoid vaccination campaign following cyclone Tomas, Republic of Fiji, 2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90(6):1031–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cook J, Jeuland M, Whittington D, Poulos C, Clemens J, Sur D, et al. The cost-effectiveness of typhoid Vi vaccination programs: calculations for four urban sites in four Asian countries. Vaccine 2008;26(50):6305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Muyembe-Tamfum J, Veyi J, Kaswa M, Lunguya O, Verhaegen J, Boelaert M. An outbreak of peritonitis caused by multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhi in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Travel Med Infect Dis 2009;7(1):40–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Walters MS, Routh J, Mikoleit M, Kadivane S, Ouma C, Mubiru D, et al. Shifts in geographic distribution and antimicrobial resistance during a prolonged typhoid fever outbreak – Bundibugyo and Kasese Districts, Uganda, 2009–2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8(3):e2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].WHO guide for standardization of economic evaluations of immunization programmes. World Health Organization, Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals; 2008.

- [18].National burden of disease manual: a practical guide. World Health Organization, Global Program on Evidence for Health Policy; 2001.

- [19].International Data Base. Population pyramid for Uganda; 2012. Available from: http://www.census.gov/population/international/ [accessed January 2015].

- [20].Mogasale V, Maskery B, Ochiai RL, Lee JS, Mogasale VV, Ramani E, et al. Burden of typhoid fever in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic, literature-based update with risk-factor adjustment. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2(10):e570–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mogasale V, Desai SN, Mogasale VV, Park JK, Ochiai RL, Wierzba TF. Case fatality rate and length of hospital stay among patients with typhoid intestinal perforation in developing countries: a systematic literature review. PLOS ONE 2014;9(4):e93784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Anwar E, Goldberg E, Fraser A, Acosta CJ, Paul M, Leibovici L. Vaccines for preventing typhoid fever. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD001261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Consumer Price Index Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2014.

- [24].Treasury reporting rates of exchange as of September 30, 2014. Bureau of the Fiscal Service, U.S. Department of the Treasury; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kumaranayake L The real and the nominal? Making inflationary adjustments to cost and other economic data. Health Policy Plan 2000;15(2):230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Immunization service delivery – projected vaccine wastage; 2014. Available from: http://apps.who.int/immunization_delivery/systems_policy/logistics_projected_wastage/en/index.html [accessed January 2014].

- [27].Parmar D, Baruwa EM, Zuber P, Kone S. Impact of wastage on single and multi-dose vaccine vials: implications for introducing pneumococcal vaccines in developing countries. Hum Vaccines 2010;6(3):270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].GDP per capita: Uganda; 2015. Available from: http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=Uganda [accessed January 2015].

- [29].Pitzer VE, Bowles CC, Baker S, Kang G, Balaji V, Farrar JJ, et al. Predicting the impact of vaccination on the transmission dynamics of typhoid in South Asia: a mathematical modeling study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8(1):e2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nakao JH. A knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey to inform a typhoid fever intervention campaign — Kasese District, Rural Western Uganda. In: Epidemic intelligence service conference. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jeuland M, Cook J, Poulos C, Clemens J, Whittington D. Cost-effectiveness of new-generation oral cholera vaccines: a multisite analysis. Value Health 2009;12(6):899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Global health observatory: Uganda – country data and statistics; 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/uga/en/ [accessed January 2015].