Abstract

[18F]DPA-714 is a radiotracer specific to the translocator protein (TSPO) and is useful for in vivo Positron Emission Tomography imaging studies. In this report, we have developed an automated radiosynthesis of [18F]DPA-714 on a commercially-available radiosynthesis platform, which comports with USP <823> guidelines. The wide availability of the radiosynthesis module and ease of dissemination of the production sequence will facilitate preclinical and clinical research of TSPO-related pathology.

Keywords: Fluorine-18, F-18, Positron Emission Tomography, radiosynthesis, radiochemistry, automation

INTRODUCTION

Neuroinflammation plays an important role in evoking Central Nervous System (CNS) immunity as a primary defense mechanism against harm and restoring homeostasis(Sochocka et al., 2017; Wyss-Coray & Mucke, 2002). As the chief sensory mediators of brain integrity, microglia ramify as a response to neuronal insult through modifications of gene expression, morphology, and function(Block et al., 2007; Czeh et al., 2011; Hanisch & Kettenmann, 2007; Jain et al., 2020). One key functional change in microglial activation is the overexpression of the translocator protein (TSPO), an 18 kDa five transmembrane protein located in the outer mitochondrial membrane. TSPO possesses a well-characterized role in transport of cholesterol(Papadopoulos et al., 2006) and is predominantly expressed in the heart, kidneys, adrenal cortex, testis, and ovaries(Rupprecht et al., 2010). The overexpression of TSPO in CNS pathology has been described in a number of disorders including TBI, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease and others.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) is a noninvasive imaging technique capable of quantifying and imaging biochemical and physiological changes in vivo. TSPO has been the target of a catalog of radiopharmaceutical ligand developments aimed at quantifying the increased expression of TSPO resulting from neurological insult. The most widely studied TSPO radiopharmaceutical, [11C]-R-PK11195 has demonstrated several limitations for its widespread use as a CNS imaging agent; most notably (1) a low brain bioavailability and poor signal-to-noise due to non-specific binding(Chauveau et al., 2008) and (2) the inherent short physical half-life of carbon-11 radiopharmaceuticals (t1/2 = 20 minutes). As such, a number of second-generation TSPO PET radiopharmaceuticals have been developed including [11C]PBR-28, [11C]DPA-713, [18F]DPA-714, [18F]FEPPA and others(Doorduin et al., 2009; Endres et al., 2009; Vignal et al., 2018). In particular, [18F]DPA-714 has shown improved bioavailability, low nonspecific binding, and significant non-displaceable binding potential in several research studies(Chauveau et al., 2009; Doorduin et al., 2009; Israel et al., 2016; James et al., 2008).

Initial dosimetry studies validated the safe use and favorable dosimetry in humans(Arlicot et al., 2012). Accordingly, clinical PET research studies have investigated the use of [18F]DPA-714 in quantifying TSPO changes in patients suffering from stroke(Ribeiro et al., 2014), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis(Corcia et al., 2012), and Alzheimer’s disease(S. S. Golla et al., 2014; S. S. V. Golla et al., 2016). Further, recent clinical studies have investigated TSPO changes in collision sports with PET using [11C]DPA-713(Coughlin et al., 2015, 2016); our programmatic interests in traumatic brain injury prompted us to develop an automated radiosynthesis of [18F]DPA-714 to allow routine access to this imaging agent for both preclinical and clinical research studies.

EXPERIMENTAL

General Considerations.

The radiochemical precursor, 2-(4-(3-(2-(diethylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-5,7-dimethylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-2-yl)phenoxy)ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate, as well as non-radioactive [19F]DPA-714, N,N-diethyl-2-(2-(4-(2-fluoroethoxy)phenyl)-5,7-dimethylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)acetamide, were synthesized in-house with slight modifications to the previously reported procedures(Banister et al., 2012; James et al., 2008). All reagents and chemicals were purchased from Millipore Sigma and used without further purification. Both precursor and standard were stored in a −20 °C freezer and were stable for at least 3 years. Radiochemical optimizations and products were analyzed by analytical HPLC (Shimadzu LC-20AD/BioScan Flow Count), Gas Chromatography (Perkin Elmer Clarus 680, ResTek Capillary Column, 30 m x 0.25mm ID) and Endotoxin (Charles River Endosafe NexGen PTS).

Radiochemistry

All radiochemical experiments were performed on a commercially available automated radiosynthesizer, Elixys Flex/Chem (Sofie Biosciences – Dulles, VA). All purifications and reformulations were performed on the commercially available automated unit, Pure/Form (Sofie Biosciences – Dulles, VA). [18F]Fluoride ion was synthesized by the nuclear reaction of 18O(p,n)18F in target of [18O]OH2 using a Siemens RDS 11 cyclotron. [18F]DPA-714 was synthesized in accordance with USP <823> guidelines. Briefly, [18F]Fluoride was captured on an anion-exchange resin (Myja Scientific-O’Neill, NE) (previously conditioned with 5 mL of 0.5 M K2CO3, followed by 10 mL of water) and then eluted with a solution containing 20 mg of Kryptofix (K222) in 0.9 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile (MeCN) and 2 mg of K2CO3 in 0.1 mL of sterile water. Water was removed by azeotropic distillation at 100 °C under negative pressure. Anhydrous acetonitrile (0.7 mL x 2) was added to the residue to azeotropically remove water at 100 °C. Next, 6 ± 1 mg of N,N-diethyl-2-[4-(2-tosylethoxy)phenyl]-5,7-dimethylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-acetamide in 1 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile was added to the dried K222/[18F]FK complex and reacted at 100°C for 15 minutes while stirring. After allowing to cool to 40°C, the solution was diluted with 3 mL of 0.1 M NH4OAc and then transferred through a non-vented syringe filter and subsequently sent to a semi-prep HPLC for purification (Phenomenex Synergi Hydro-RP, 250 X 10 mm, 10 μm; flow rate = 4.0 mL/min, gradient of 10% MeCN : 0.1 M NH4OAc to 60 % MeCN : 0.1 M NH4OAc over the course of 10 mins; tR = 11 mins) with a recording wavelength of 254 nm. The desired product was collected in a gross dilution vial containing 25 mL of 0.1 M NH4OAc and transferred through a HLB Light Sep Pak. The HLB cartridge was rinsed with 10 mL of sterile water, followed by 1 mL USP EtOH to recover the product. The final product was reconstituted with 15 mL of sterile saline and terminally sterilized through a 0.22 μm filter.

Quality Control Testing

Quality control of [18F]DPA-714 was conducted according to guidelines outlined in US Pharmacopeia chapter 823. Results for 3 process validation batches using the described radiosynthesis and associated purification and quality control tests are described in Table 2. Each batch met all acceptance criteria confirming suitability for clinical use and future production.

HPLC for identification, chemical, and radiochemical purity determination

The HPLC module was comprised of the following Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) components: SPD-20A(V) UV-Vis detector coupled to a SIL-20AHT autosampler and injection unit, LC-20AT tandem plunger, CMB-20A light system controller, CTO-20AC column thermostat with a FCV-14AH6 6-way column switching valve and a DGU020A3R degassing unit. The system was coupled in series to an Bioscan Flowcount 106 radio flow detector (Berlin, Germany) for radioactivity measurements. The HPLC software control and processing system was performed with LabSolutions Lite.

Analysis was performed on a Phenomenex Synergi Hydro-RP column (100 Å 5 μm; 250 × 4.6 mm) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min using isocratic elution with 0.1 M ammonium acetate/acetonitrile (40/60 v/v%). The spectrum was recorded at 254 nm. Prior to [18F]DPA-714 injection, system suitability was validated by injection of a blank sample (water, 20 μL), followed by the DPA-714 reference solution (10 μg/mL, 20 μL) and an additional blank injection.

GC for residual solvent and ethanol content determination

Method validation was performed for gas chromatography (GC) identification and control of residual solvents in accordance with United States Pharmacopoeia <823> guidelines as well as the United States FDA Q3C guidance document for residual solvents of pharmaceuticals for human use. Ethanol was used as an excipient to enhance stability of the product and was not considered a residual solvent. The content of ethanol was determined to verify its compliance with a maximum concentration of 10% v/v%.

The GC module consisted of the following Perkin Elmer components: Clarus 680 unit equipped with an autoinjectior/autosampler and a hydrogen flame ionization detector. The system was controlled by TotalChrom 680 software. Analysis was performed on a Restek Rtx-WAX column (part #12423) (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) with a gradient heating rate (0–1 min 60 °C, followed by a 27.5 °C/min ramp to 140 °C and held for 1 min; total run time 4.91 minutes) at a linear velocity of 32 mL/min with helium as carrier gas and a 15:1 He:H2 split ratio. Prior to [18F]DPA-714 injection, system suitability was validated by injection of a blank sample (water, 0.1 μL), followed by the reference solution containing acetonitrile and ethanol (0.1 μL) followed by three additional blank injections prior to the QC test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

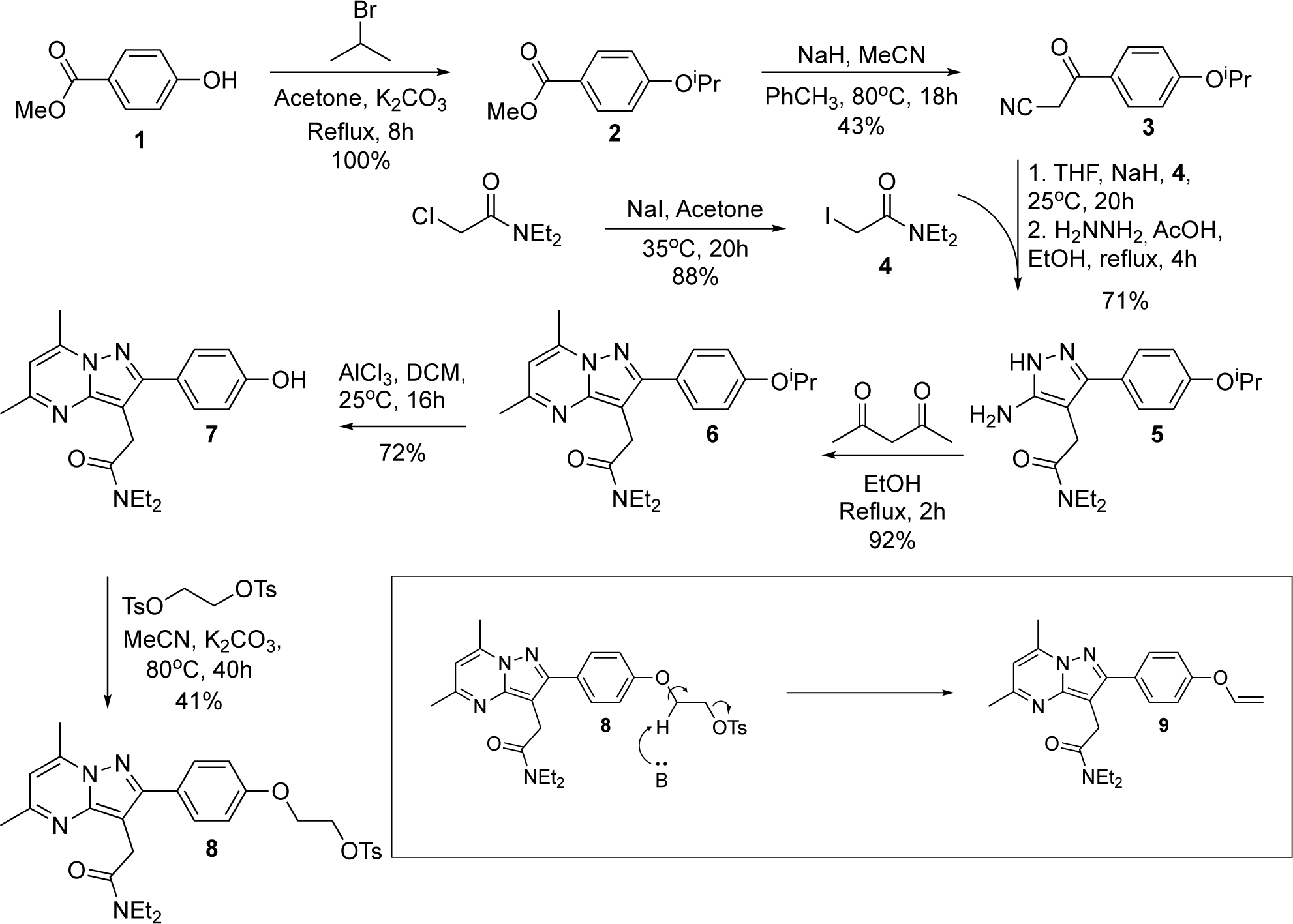

We synthesized the radiochemical precursor in-house with slight modifications to the previously reported chemical synthesis(Banister et al., 2012; James et al., 2008), which is depicted below in Scheme 1. Our optimization initially focused on the production of 5, which proceeds via enolate alkylation of an alkyl halide. Previous reports utilized an α-bromo-amide to facilitate alkylation; however, in our hands, this resulted in very low yields of the final product 5. We synthesized the α-iodo-amide 4 via the Finkelstein reaction as our new electrophile, which resulted in significant improvements in the yield of 5.

Scheme 1. Synthetic organic route to the radiochemical precursor of [18F]DPA-714.

The hypothesized formation of the elimination side product observed during the production of 8 is highlighted (lower right).

The final step in the synthesis results in an alkyl tosylate (8) to facilitate substitution with [18F]fluoride. Previous reports have synthesized 8 through Mitsunobo reaction of 2-tosyloxyethanol(James et al., 2008) or bimolecular substitution with bis-tosyloxy-ethane(Damont et al., 2008; Doorduin et al., 2009). In our hands, the Mitsonubu reaction generally resulted in very low yields, thus, our optimization efforts focused on improving the SN2 reaction. We explored several different reaction conditions (solvent, base, temperature) and found that the production of 8 was ultimately limited by a competing deleterious elimination of the final product, resulting in the formation of a side product, 9, where the longer 8 remained in solution, the more 9 appeared to form. We also found the solubility of 7 to play an important role; due to the marginal solubility of 7, addition of more solvent and higher reaction temperature led to a faster reaction, minimizing the elimination reaction and ultimately increasing the overall yields of 8. Adding more equivalents of bis-tosyloxy-ethane also resulted in faster conversion of 7 to 8, reducing the opportunity for 9 to form. After purification by flash chromatography, 8 was further purified by vapor diffusion recrystallization, with an overall yield of 41% for this step.

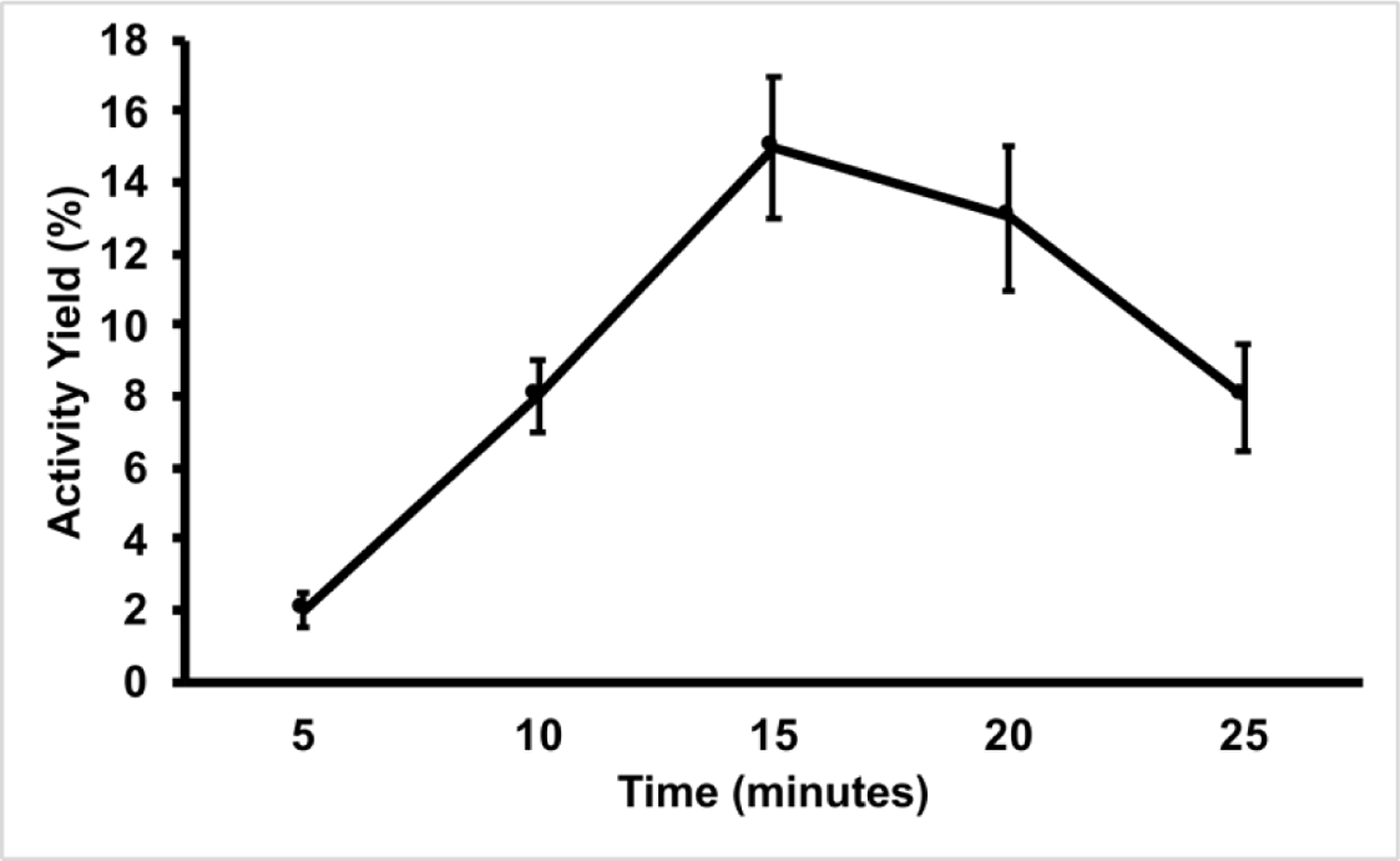

The radiochemical synthesis of [18F]DPA-714 (10) is a straightforward bimolecular substitution reaction (SN2) with [18F]fluoride, shown below in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Radiochemical Synthesis of [18F]DPA-714.

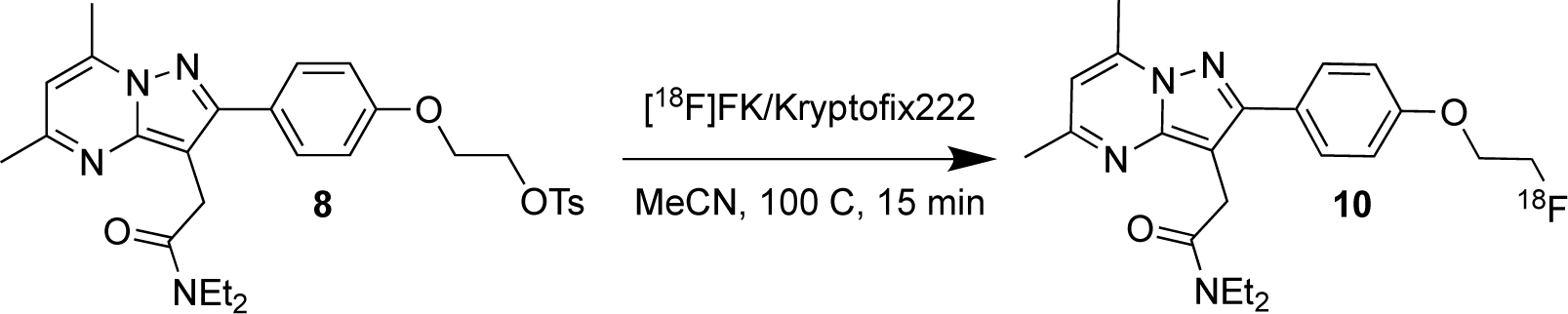

As is shown in Scheme 2, the radiosynthesis is a single step. Thus, the major radiosynthetic parameters needed for optimization were [18F]fluoride reaction time and temperature. The major goal for this work was to develop the radiochemical synthesis on a commercially-available automated radiosynthesizer to facilitate access to the imaging agent for both preclinical and clinical research. To this end, we utilized the Elixys Flex/Chem and Pure/Form. The reagent and consumable setup is described below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Reagents and consumables needed to complete the radiosynthesis of [18F]DPA-714 on the Elixys Flex/Chem™.

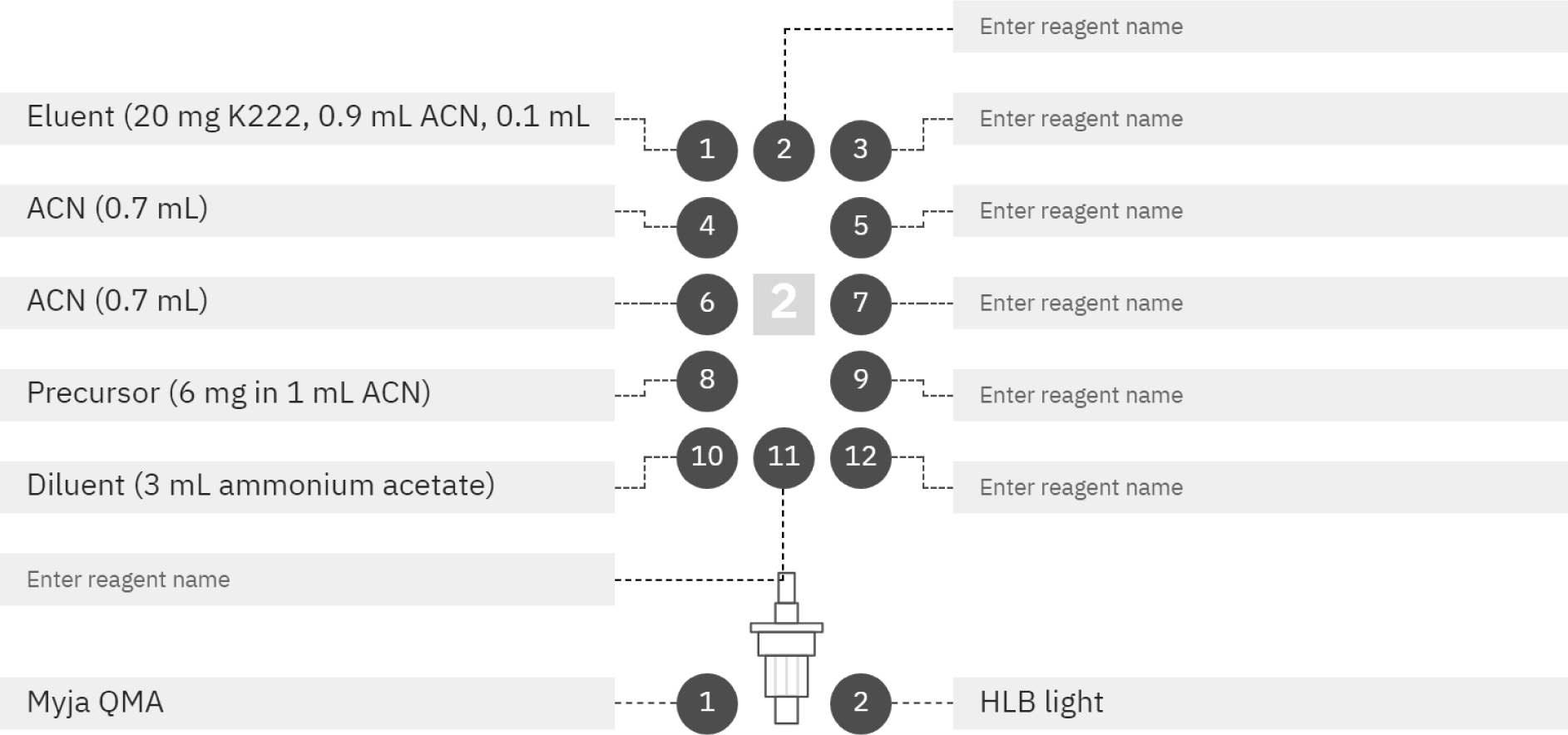

Our initial optimization efforts were aimed at the substitution reaction with [18F]fluoride. Thus, we first explored a variety of conditions modifying reaction time and temperature. The results of the time and temperature optimization are summarized in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Figure 2. Influence of Time on Activity Yields of [18F]DPA-714.

All reactions were performed at 100 °C on the Elixys Flex/Chem module. All activity yields are reported as an average (n=3).

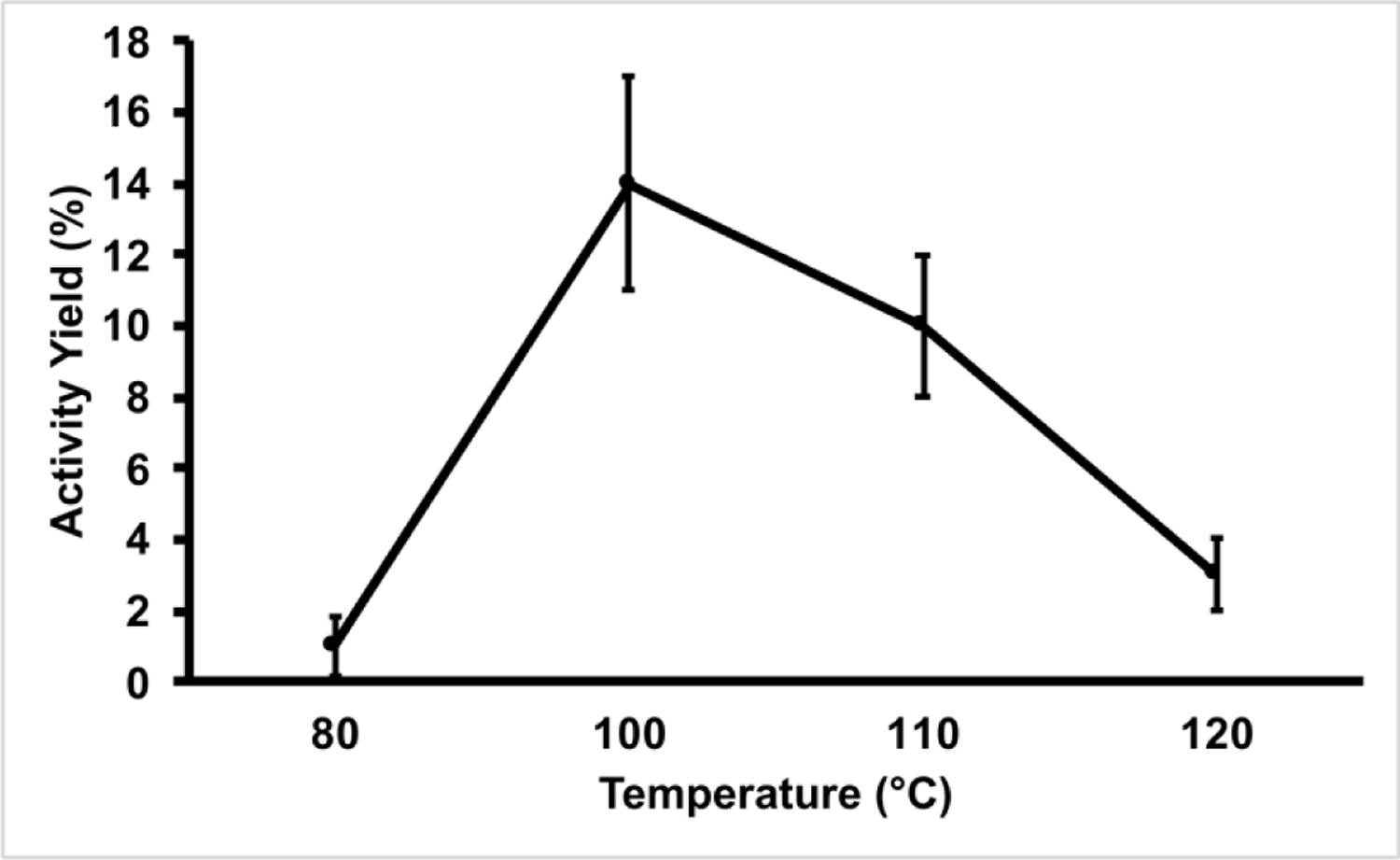

Figure 3. Influence of Temperature on Activity Yields of [18F]DPA-714.

All reactions were performed for 15 minutes on the Elixys Flex/Chem module. All activity yields are reported as an average (n=3).

Our initial optimization parameter for the radiosynthesis was the influence of reaction time. In our hands, manual production of [18F]DPA-714 achieved maximal activity yields in as little as 5 minutes. However, as noted in Figure 1, maximal activity yields required 15 minutes of heating on the Flex/Chem system. The longer heating times on the Flex/Chem are likely due to the system’s desig using thick-wall glass v-vials, which should require longer heating times to allow the internal solution temperature to reach its intended target. We also investigated the effect of temperature on the reaction and observed 100 °C to be the ideal temperature (Figure 2). As the reaction progresses toward completion, the reaction solution turns a deep red to brown color and produces some form of insoluble aggregates. These particulates are increased both in quantity and size as the reaction temperature was increased. Thus, the low yields observed at 120 °C were the result of activity loss within the insoluble material remaining in the reactor vial.

An additional important modification to the Pure/Form platform was introduced during the transfer of the reaction mixture from the Flex/Chem to the semi-prep HPLC (Pure/Form) for final purification. The Flex/Chem utilizes a LED-based liquid sensor to initiate automatic injections of solutions onto the HPLC. However, as described above, the fluorination reaction produces a crude solution that is both turbid and deeply saturated in color. Thus, specifically in this reaction, the crude solution often did not initiate HPLC injections and were instead lost to waste after passing through the loop. To maximize solution transfer onto the HPLC, we chose to insert a non-vented syringe filter immediately prior to the HPLC loop injection line, approximately 6 cm from the injection loop. The syringe filter served to not only filter insoluble material from our crude reaction mixture prior to HPLC injection onto the column, it also created a vapor-lock after the reaction solution passed through, thereby, preventing loss of the reaction solution through the HPLC loop to waste. While the syringe filter was effective at minimizing loss of the reaction solution during transfer, perhaps unsurprisingly, we noticed radiochemical yields were substantially impacted by the type of filter membrane used. Our survey of various syringe filter membranes is shown below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Impact of syringe filter membrane on recovery of [18F]DPA-714.

| Syringe Filter | Manufacturer | Part number | Membrane | Pore Size (μm) | Diameter (mm) | % Activity Recovered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Millex | SLGV013SL | PVDF | 0.22 | 13 | 85 |

| 2 | Millex | SLHP033RS | PES | 0.45 | 33 | 60 |

| 3 | PALL | 4541 | Nylon | 0.45 | 13 | 90 |

| 4 | PALL | 4545 | PVDF | 0.45 | 13 | 98 |

| 5 | Millex | SLHAM33SS | MCE | 0.45 | 33 | 65 |

| 6 | PALL | 4558 | GHP | 0.45 | 33 | 90 |

Hydrophilic PVDF membrane provides the highest recoveries of radioactivity. Each syringe filter tested is reported as an average (n=3). PVDF = polyvinylidene fluoride; PES = polyethersulfone; MCE = mixed cellulose ester; GHP = hydrophilic polypropylene.

As shown in Table 1, PVDF filter membranes retained the least amount of associated radioactivity and subsequently, resulted in higher activity yields of [18F]DPA-714. Generally speaking, hydrophobic membranes appeared to retain the most radioactivity. In addition, pore size had a noticeable effect on activity yields, where lower pore sizes were directly proportional to activity yields.

With the reaction parameters optimized, our final goal was to conduct 3 process validation batches to qualify the radiosynthesis for clinical research production. After performing the optimized radiosynthesis described, the final solution was terminally sterilized with a sterile 0.22 μm polyethersulfone (PES) filter. Our three validation runs demonstrated [18F]DPA-714 was synthesized in a 13.5 ± 3.04% activity yield (EOS) with a molar activity of 3.7 ± 1.4 Ci/μmol (n=3) in a total synthesis time of 90 minutes. All doses were submitted for Quality Control testing and met all acceptance criteria confirming suitability for clinical research use, the results of each validation run are presented above in Table 2. Radiochemical purity was analyzed for each batch over 1 hour increments to assign an expiration time of 8 hours from EOS.

Table 2.

Quality Control data from each process validation batch of [18F]DPA-714.

| QC Test | Specification | Batch 1 | Batch 2 | Batch 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radionuclidic Purity | Presence of peak at 511 keV | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Residual Solvent | MeCN <400 ppm | 22 ppm | 22 ppm | 15 ppm |

| Ethanol content | < 78,900 ppm | 61,133 ppm | 68,676 ppm | 55,782 ppm |

| Radionuclidic Identity | 100–120 min | 109.8 min | 108.9 min | 107.7 min |

| Bacterial Endotoxin | <17.5 EU/mL | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| pH | 5–8 | 5 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Chemical Purity (K222 test) | < 50 μg/mL K222 | < 50 μg/mL | < 50 μg/mL | < 50 μg/mL |

| Chemical Purity (UV @254 nm-HPLC) | <15 μg / mL | 0.06 μg / mL | 0.01 μg / mL | 0.01 μg / mL |

| Radiochemical Purity | >90% | >99% | >99% | >99% |

| Appearance | Clear, colorless and free of particulates | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Filter Integrity | ≥47 psig | 87 psig | 87 psig | 87 psig |

| Sterility | Negative / No Growth | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Molar Activity | >1 Ci/μmol | 2.8 | 2.2 | 6.1 |

All batches met or exceeded quality control specifications as guided by USP <823>.

Finally, another very recent publication also reported the radiosynthesis of [18F]DPA-714 on the commercially available radiosynthesis module, Trasis AllinOne(Cybulska et al., 2021). While the end-product ([18F]DPA-714) is identical, the radiosynthesis reported here is novel with respect to the reagents, times, temperatures, and other parameters needed to produce the radiopharmaceutical on a very different automated radiosynthesizer, the Elixys Flex/Chem. For example, the previous report utilized the phase transfer catalyst, tetraethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), to demonstrate a slight improvement in radiochemical yield. As such, Cybulska et al also developed a qualitative test for determination of quaternary ammonium salt in their final formulation product; however, as they point out, no known limits for TEAB are reported in the European Pharmacopoeia. The radiosynthesis in this report uses the well-known phase transfer catalyst Kryptofix™ (K2.2.2.) and uses a similar qualitative TLC spot test for determination in final product formulations, which has been deemed acceptable by the US FDA. More importantly, the recent efforts focused on making [18F]DPA-714 widely available for research studies, as reported in this report and others, underscore the importance of this tracer and the TSPO biomarker. As such, it is important [18F]DPA-714 and other radiopharmaceuticals are available on multiple commercially available automated radiosynthesizers to improve access to these agents and further facilitate imaging research.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we have described the development and implementation of an automated radiochemical synthesis of [18F]DPA-714 on a commercially-available synthesizer unit, the Elixys Flex/Chem + Pure/Form system. In addition, we have also described several improvements to the synthetic organic chemical production of the radiochemical precursor. The availability of a USP <823> compliant radiosynthesis, in addition to an optimized production of the precursor, will ensure reliable availability of [18F]DPA-714 to facilitate clinical imaging research studies.

Highlights.

A USP <823> compliant [18F]DPA-714 radiosynthesis is now available

Synthesis of a radiochemical precursor is optimized

Low yields of a radiochemical precursor were the result of an elimination product formed in situ

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the University of Virginia Radiochemistry Core for their services and infrastructure to complete the project.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering [R01EB028338-01] and the University of Virginia BRAIN Institute [LC00183].

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Arlicot N, Vercouillie J, Ribeiro M-J, Tauber C, Venel Y, Baulieu J-L, Maia S, Corcia P, Stabin MG, Reynolds A, Kassiou M, & Guilloteau D (2012). Initial evaluation in healthy humans of [18F]DPA-714, a potential PET biomarker for neuroinflammation. Nuclear Medicine and Biology, 39(4), 570–578. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banister SD, Wilkinson SM, Hanani R, Reynolds AJ, Hibbs DE, & Kassiou M (2012). A practical, multigram synthesis of the 2-(2-(4-alkoxyphenyl)-5,7-dimethylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)acetamide (DPA) class of high affinity translocator protein (TSPO) ligands. Tetrahedron Letters, 53(29), 3780–3783. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.05.044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Zecca L, & Hong J-S (2007). Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(1), 57–69. 10.1038/nrn2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauveau F, Boutin H, Camp NV, Dollé F, & Tavitian B (2008). Nuclear imaging of neuroinflammation: a comprehensive review of [11C]PK11195 challengers. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, 35(12), 2304–2319. 10.1007/s00259-008-0908-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauveau F, Camp NV, Dollé F, Kuhnast B, Hinnen F, Damont A, Boutin H, James M, Kassiou M, & Tavitian B (2009). Comparative Evaluation of the Translocator Protein Radioligands 11C-DPA-713, 18F-DPA-714, and 11C-PK11195 in a Rat Model of Acute Neuroinflammation. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 50(3), 468–476. 10.2967/jnumed.108.058669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcia P, Tauber C, Vercoullie J, Arlicot N, Prunier C, Praline J, Nicolas G, Venel Y, Hommet C, Baulieu J-L, Cottier J-P, Roussel C, Kassiou M, Guilloteau D, & Ribeiro M-J (2012). Molecular Imaging of Microglial Activation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. PLoS ONE, 7(12), e52941. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Minn I, Bienko N, Ambinder EB, Xu X, Peters ME, Dougherty JW, Vranesic M, Koo SM, Ahn H-H, Lee M, Cottrell C, Sair HI, Sawa A, Munro CA, Nowinski CJ, Dannals RF, Lyketsos CG, … Pomper MG (2016). Imaging of Glial Cell Activation and White Matter Integrity in Brains of Active and Recently Retired National Football League Players. JAMA Neurology, 74(1), 67. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Munro CA, Ma S, Yue C, Chen S, Airan R, Kim PK, Adams AV, Garcia C, Higgs C, Sair HI, Sawa A, Smith G, Lyketsos CG, Caffo B, Kassiou M, Guilarte TR, & Pomper MG (2015). Neuroinflammation and brain atrophy in former NFL players: An in vivo multimodal imaging pilot study. Neurobiology of Disease, 74, 58–65. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska KA, Bloemers V, Perk LR, & Laverman P (2021). Optimised GMP-compliant production of [18F]DPA-714 on the Trasis AllinOne module. EJNMMI Radiopharmacy and Chemistry, 6(1), 20. 10.1186/s41181-021-00133-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeh M, Gressens P, & Kaindl AM (2011). The Yin and Yang of Microglia. Developmental Neuroscience, 33(3–4), 199–209. 10.1159/000328989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damont A, Hinnen F, Kuhnast B, Schöllhorn-Peyronneau M, James M, Luus C, Tavitian B, Kassiou M, & Dollé F (2008). Radiosynthesis of [18F]DPA-714, a selective radioligand for imaging the translocator protein (18 kDa) with PET. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals, 51(7), 286–292. 10.1002/jlcr.1523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doorduin J, Klein HC, Dierckx RA, James M, Kassiou M, & Vries E. F. J. de. (2009). [11C]-DPA-713 and [18F]-DPA-714 as New PET Tracers for TSPO: A Comparison with [11C]-(R)-PK11195 in a Rat Model of Herpes Encephalitis. Molecular Imaging and Biology, 11(6), 386. 10.1007/s11307-009-0211-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres CJ, Pomper MG, James M, Uzuner O, Hammoud DA, Watkins CC, Reynolds A, Hilton J, Dannals RF, & Kassiou M (2009). Initial Evaluation of 11C-DPA-713, a Novel TSPO PET Ligand, in Humans. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 50(8), 1276–1282. 10.2967/jnumed.109.062265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golla SS, Boellaard R, Oikonen V, Hoffmann A, Berckel BN van, Windhorst AD, Virta J, Haaparanta-Solin M, Luoto P, Savisto N, Solin O, Valencia R, Thiele A, Eriksson J, Schuit RC, Lammertsma AA, & Rinne JO (2014). Quantification of [18F]DPA-714 Binding in the Human Brain: Initial Studies in Healthy Controls and Alzheimer’S Disease Patients. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 35(5), 766–772. 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golla SSV, Boellaard R, Oikonen V, Hoffmann A, Berckel B. N. M. van, Windhorst AD, Virta J, Beek E. T. te, Groeneveld GJ, Haaparanta-Solin M, Luoto P, Savisto N, Solin O, Valencia R, Thiele A, Eriksson J, Schuit RC, Lammertsma AA, & Rinne JO (2016). Parametric Binding Images of the TSPO Ligand 18F-DPA-714. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 57(10), 1543–1547. 10.2967/jnumed.116.173013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch U-K, & Kettenmann H (2007). Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nature Neuroscience, 10(11), 1387–1394. 10.1038/nn1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel I, Ohsiek A, Al-Momani E, Albert-Weissenberger C, Stetter C, Mencl S, Buck AK, Kleinschnitz C, Samnick S, & Sirén A-L (2016). Combined [18F]DPA-714 micro-positron emission tomography and autoradiography imaging of microglia activation after closed head injury in mice. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 13(1), 140. 10.1186/s12974-016-0604-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain P, Chaney AM, Carlson ML, Jackson IM, Rao A, & James ML (2020). Neuroinflammation PET Imaging: Current Opinion and Future Directions. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 61(8), 1107–1112. 10.2967/jnumed.119.229443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James ML, Fulton RR, Vercoullie J, Henderson DJ, Garreau L, Chalon S, Dolle F, Costa B, Selleri S, Guilloteau D, & Kassiou M (2008). DPA-714, a New Translocator Protein–Specific Ligand: Synthesis, Radiofluorination, and Pharmacologic Characterization. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 49(5), 814–822. 10.2967/jnumed.107.046151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos V, Baraldi M, Guilarte TR, Knudsen TB, Lacapère J-J, Lindemann P, Norenberg MD, Nutt D, Weizman A, Zhang M-R, & Gavish M (2006). Translocator protein (18kDa): new nomenclature for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor based on its structure and molecular function. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 27(8), 402–409. 10.1016/j.tips.2006.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro M-J, Vercouillie J, Debiais S, Cottier J-P, Bonnaud I, Camus V, Banister S, Kassiou M, Arlicot N, & Guilloteau D (2014). Could 18 F-DPA-714 PET imaging be interesting to use in the early post-stroke period? EJNMMI Research, 4(1), 28. 10.1186/s13550-014-0028-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht R, Papadopoulos V, Rammes G, Baghai TC, Fan J, Akula N, Groyer G, Adams D, & Schumacher M (2010). Translocator protein (18 kDa) (TSPO) as a therapeutic target for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 9(12), 971–988. 10.1038/nrd3295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sochocka M, Diniz BS, & Leszek J (2017). Inflammatory Response in the CNS: Friend or Foe? Molecular Neurobiology, 54(10), 8071–8089. 10.1007/s12035-016-0297-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignal N, Cisternino S, Rizzo-Padoin N, San C, Hontonnou F, Gelé T, Declèves X, Sarda-Mantel L, & Hosten B (2018). [18F]FEPPA a TSPO Radioligand: Optimized Radiosynthesis and Evaluation as a PET Radiotracer for Brain Inflammation in a Peripheral LPS-Injected Mouse Model. Molecules, 23(6), 1375. 10.3390/molecules23061375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, & Mucke L (2002). Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease—A Double-Edged Sword. Neuron, 35(3), 419–432. 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00794-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]