Abstract

Objectives:

There is strong evidence supporting emergency department (ED)-initiated buprenorphine for opioid use disorder (OUD), but less is known about how to implement this practice. Our aim was to describe implementation, maintenance, and provider adoption of a multi-component strategy for OUD treatment in three urban, academic EDs.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective analysis of electronic health record (EHR) data for adult patients with OUD-related visits before (3/2017-11/2018) and after (12/2018-7/2020) implementation. We describe patient characteristics, treatment, and process measures over time and conducted an interrupted time series analysis (ITSA) using a patient-level multivariable logistic regression model to assess the association of the interventions with buprenorphine use and other outcomes. Finally, we report provider-level variation in prescribing after implementation.

Results:

There were 2665 OUD-related visits during the study period; 28% for overdose, 8% for withdrawal, and 64% for other conditions. 13% of patients received MOUDs during or after their ED visit. Following intervention implementation, there were sustained increases in treatment and process measures, with a net increase in total buprenorphine of 20% in the post-period (95% CI 16%-23%). In the adjusted patient-level model, there was an immediate increase in probability of buprenorphine treatment of 24.5% (95% CI 12.1% to 37.0%) with intervention implementation. 70% of providers wrote at least one buprenorphine prescription, but provider-level buprenorphine prescribing ranged from 0-61% of OUD-related encounters.

Conclusions:

A combination of strategies to increase ED-initiated OUD treatment were associated with sustained increases in treatment and process measures. However, adoption varied widely among providers, suggesting additional strategies may be needed for broader uptake.

INTRODUCTION

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and overdose deaths are rapidly accelerating in the United States, with over 70,000 drug overdose deaths in 2019, largely due to opioids.1 OUD-related emergency department (ED) visits have also increased 100% in the last decade,2 and there has been increased recognition that ED visits are critical opportunities to initiate evidence-based interventions for OUD.3 Medications for OUD (MOUDs), including methadone and buprenorphine, improve a number of outcomes in patients with OUD including mortality, physical and mental health, illicit drug use, and retention in treatment.4,5 Initiation of buprenorphine in a setting as accessible as the ED is particularly promising since it can be administered or prescribed from the ED and continued in general outpatient settings such as primary care. Randomized controlled trial evidence has demonstrated ED-initiated buprenorphine doubles rates of treatment engagement at 30 days compared to referral alone 6 and is cost-effective.7 Importantly, initiation of buprenorphine after a non-fatal overdose is associated with a 38% reduction in mortality at one year.8 The strength of the evidence has led to recent calls to action for EDs to implement OUD treatment protocols by professional and government organizations.9,10

Despite calls to action, there is limited evidence about effective strategies to implement ED-initiated treatment for OUD and sustain increases in prescribing. Numerous barriers to OUD treatment have been described, including time, competing demands, lack of knowledge or comfort with OUD treatment, and lack of protocols or guidance.11-13 Treatment implementation is further complicated by regulatory requirements, including the need for a DATA 2000 waiver, better known as an X-waiver, required to prescribe buprenorphine for the outpatient setting after discharge. Although federal legislation in April 2021 eliminated the required training for providers prescribing buprenorphine to up to 30 patients,14 it is unclear how this will translate to practice change. Multiple studies in non-ED settings have demonstrated that even among X-waivered providers, the majority do no prescribe buprenorphine.15 And even among X-waivered providers in the acute care setting, other commonly cited obstacles include lack of referral pathways for outpatient treatment and perceived patient barriers such lack of housing or social support.12,16

A critical challenge for widespread adoption is designing scalable strategies that overcome these multi-level barriers to treatment. Prior work from our team demonstrated that a financial incentive was effective in increasing X-waiver credentialing and buprenorphine prescribing in the immediately post-period, increasing the percentage of X-waivered ED physicians from 6% to 89%.17 However, it remained unclear whether this practice would be sustained and universally adopted across ED clinicians. Here, we describe the implementation of a multicomponent ED-based strategy for increasing identification and treatment of patients with OUD at three urban EDs within a large academic health system. Our objective was to evaluate the association of these interventions with increasing and sustaining treatment of OUD in our ED and explore provider-level variation in outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective evaluation of the implementation and maintenance of our multicomponent strategy to increase ED-based treatment for OUD. Our study design was informed by the RE-AIM framework, which provides a structured approach to measuring the implementation of evidence-based practices.18 The five components are reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance. In evaluating our outcomes, we were interested in adoption (i.e. proportion of providers administered buprenorphine in the ED and wrote buprenorphine prescriptions), implementation (i.e. use of the strategies) and in maintenance (i.e. impact over time). The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and follow the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) 2.0 reporting guideline.19

Penn Medicine is a large, academic health system in Philadelphia, which has the highest overdose death rate of any large U.S. city.20 The hospitals included in our study include a large tertiary referral hospital, a level 1 trauma center, and a downtown hospital with an associated psychiatric crisis center. Together these 3 EDs receive approximately 120,000 visits annually. Prior to the intervention, there was limited use of buprenorphine or take-home naloxone in spite of efforts of clinician champions and the implementation of health system guidelines for treatment initiation in patients with OUD.

Selection of Participants

For our analysis, we included adult patients (≥18 years) who were seen and discharged after an opioid-related ED visit at one of three urban, academic EDs within Penn Medicine from March 2017 to July 2020. Opioid-related encounters were identified using ICD-10 codes for opioid use disorder and overdose (See Appendix A).21 We included all patients regardless of whether they were on MOUDs prior to the index visit.

Interventions

Our implementation strategies were informed by principles of behavior change and iteratively tested with a series of targeted pilots. Implementation strategies can be defined as “methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of a clinical program or practice.”22,23 Our strategies focused on provider training, EHR decision support, integration of peer recovery specialists into clinical teams, and the use of automated prompts to streamline processes.

Design was influenced by the Fogg Behavior Model, which asserts that in order for behavior change to occur, three things must be in place: 1) sufficient motivation, 2) ability to perform the behavior, and 3) a trigger to perform the behavior.24 To inform the strategies, we used innovation and design methods, borrowing from industries outside health care that have developed approached to design and refine techniques or products in a way that allows them to quickly learn and iterate prior to large-scale implementation. These methods often are referred to as rapid-cycle innovation, fail fast or user-centered design,25 and include multiple elements.26 The work included four phases: 1) contextual inquiry, 2) problem definition, 3) exploration of alternatives, and 4) rapid validation.27 Contextual inquiry included conducting a survey of ED physicians about barriers to treatment initiation12 as well as observing ED workflows, including monitoring patients on the ED tracking board and informally interviewing providers to understand how patients presented to the ED and where missed opportunities for patient engagement in treatment. Using these initial inputs, we then refined our goals and conducted small, rapid pilots to iteratively refine the components below.

ED Treatment Initiation (Ability)

In order to build capacity among ED providers to administer and prescribe MOUDs, our health system invested in X-waiver training for all ED physicians. The details of this intervention are reported elsewhere,17 but briefly, providing a financial incentive for X-waiver training led to substantial increases in the number of waivered providers from 6% to 90% over a 6 week period when the incentive was offered (November-December 2019). X-waiver training was also associated with increased physician confidence in initiating buprenorphine treatment in the ED.12 In addition, our team developed two order sets in the electronic health record (EHR) which provided clinical decision support and prepopulated orders for 1) initiation of buprenorphine and 2) discharge orders for patients with OUD .

Integration of Peer Recovery Specialists (Ability)

We leveraged the expertise of trained peer recovery specialists (PRSs) working in the health system to increase engagement of patients in OUD treatment. PRSs provide non-clinical support to people living with SUDs who are seeking recovery assistance and have expertise in engaging with patients and in navigating patient and system barriers to care.28 Core activities include system navigation, supporting behavior change, harm reduction, and relationship building.29,30 Additional activities include referrals and support for treatment, housing, transportation, employment, drug court proceedings, and probation. PRSs facilitated follow-up for patients who initiated treatment in the ED, with referrals made to primary care practices in the health system, internal and external specialty substance use treatment programs, and a local harm reduction organization that can provide care for uninsured patients. PRSs were already employed in our health system, but rarely worked in the ED, representing a missed opportunity to augment care for patients with OUD. During this study period, PRSs were available weekdays during business hours and evenings until 10 PM.

Use of Automated Alerts to Amplify Connections with Peer Recovery Specialists (Prompts)

In order to increase connection of patients with OUD to PRSs, we developed a system for real-time, automated identification of patients with known or suspected OUD. Based on literature31 and chart review, we identified a simple set of criteria that could predict patients who might be appropriate for CRS consultation. These included: 1) Chief complaint suggestive of OUD (i.e. overdose, detox), 2) Diagnosis or visit for OUD in the past year based on ICD code criteria, 3) receipt of naloxone or buprenorphine during their ED visit. Using the program Agent, which integrates into the EHR and can scan ED patient charts in real-time, we used these criteria to generate messages that went directly to the PRSs through a secure, HIPAA-compliant mobile application. PRSs are then able to review patient charts, contact the care team, and go directly to the patient bedside for a consult without additional steps on the part of ED providers. This system runs in the background, and compliments other forms of patient identification, such as traditional consults initiated by individual ED providers.

Culture Change (Motivation)

Facilitating culture change to both motivate and reinforce positive changes was a final element of our strategy. We employed several methods to achieve this. First, we provided public appreciation and acknowledgement when ED clinicians started MOUD or initiated referrals. Second, we created wearable buttons to distribute to physicians the first time they wrote a prescription for buprenorphine. Finally, we promoted professional relationships between recovery specialists and ED clinicians through frequent communication and follow-up. During the first several months of the rollout, our team provided feedback to ED providers for patients they had seen through email or in-person communication, including when they attended follow-up appointments or experienced other positive outcomes related to treatment.

Data Source

We used data from the Epic EHR pulled from Clarity, a reporting database for Epic (Hyperspace 2017; Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI). Rates of missingness for our primary and secondary outcomes were 0%, and no patients were excluded due to missing data.

Outcomes

We assessed both clinical care measures and process measures based on previously identified quality measures for ED-based OUD care including diagnosis, assessment and acute stabilization, treatment, and implementation of harm reduction interventions.32 For the clinical care measures, our primary outcome was buprenorphine treatment rate per opioid-related ED encounter, a composite metric that included buprenorphine administration in the ED and/or a prescription for buprenorphine at discharge. We also assessed the proportion of patients receiving methadone administered in the ED, which included either a continuation of methadone treatment after confirmation with a patient’s opioid treatment program or a one-time, low dose of methadone for treatment of withdrawal as allowed by Federal Law for patients in the hospital.33 The choice to use methadone as opposed to buprenorphine was left to the providers; our ED does not provide direct referrals to opioid treatment programs, so buprenorphine is recommended in ED guidelines as first-line treatment due to flexibility in options for follow-up and methadone is not part of the EHR decision support. There are internal guidelines for methadone dosing available for providers in the ED and hospital, with psychiatric consultation required only for those admitted with plan for dose increases for initiation of methadone maintenance. Finally, we measured the proportion of patients receiving a naloxone prescription at discharge, a measure of harm reduction implementation. In addition, we assessed adoption by measuring provider-level prescribing of buprenorphine per OUD-related encounter before and after the implementation of our intervention. We also evaluated process measures, including 1) assessment of withdrawal (as measured by nurses using the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale, or COWS, which was recorded in the EHR) and 2) use of either of two ED order sets for treatment in the ED and at discharge. Order sets contained decision support and prepopulated orders for two pathways, 1) buprenorphine initiation in the ED and 2) discharge orders for OUD. Clinicians could also initiate medications outside the order set pathway.

Other Variables

We extracted demographic and other patient characteristics from the EHR, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance status. We also extracted comorbid mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) using ICD-10 codes and calculated Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) based on previously coded diagnoses in patient records. We characterized patient visits in terms of presentation type: overdose, withdrawal, and other based on ICD-10 codes (Appendix A) and extracted urine drug screen results from the EHR in cases when this was available. Finally, we reported length of stay (LOS) for the index visit as well as repeat ED visits and hospital admissions at 30 days from the index visit. ED LOS was an important balancing measure to ensure that increasing treatment interventions for OUD did not have a detrimental impact on ED throughput.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the sample and compared patient and visit characteristics between the pre- and post-period using difference in proportions for independent samples, reporting mean deltas and 95% confidence intervals. In addition, we included descriptive analysis of trends in our key quality indicators over time. For buprenorphine prescriptions, we also included a provider-level analysis of rate of buprenorphine prescriptions per opioid use disorder-related encounter after the interventions after restricting the reporting to providers with 10 or more opioid use disorder-related encounters.

We conducted an interrupted time series analysis (ITSA) using mulitvariable logistic regression to assess changes in our primary outcome, total buprenorphine use, as well as other treatment and process measures as secondary outcomes. We used a patient-level logistic regression model controlling for patient characteristics and calendar time with fixed effects at the hospital level to model the association of the intervention with treatment and process outcomes. The unit of analysis was study month, and the model included calendar time (study month), time period (pre vs. post), and an interaction term between calendar time and the time period. We looked at standardized mean differences (SMD) over time among patient characteristics and included covariates with a SMD >0.1 in the final model. The pre-period went from March 2017 to November 2018 and the post-period went from December 2018 to July 2020, the last data available at the time of analysis. The time interval reflected the month that both the X-waivering campaign and the patient identification alerts went into effect, automating the process of connecting ED patients with peers in recovery. We report adjusted outcomes and adjusted marginal probability associated with intervention implementation. We also included a simple ITSA using linear regression for the purposes of illustration. For the simple ITSA, we modeled the change in proportion of visits demonstrating each outcome of interest per month before and after the intervention implementation period. The unit of analysis was study month, and the proportion of visits with each outcome of interest was treated as a continuous variable. Analyses were conducted using Stata (Version 15.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX) and R statistical software.34

RESULTS

Patient and Visit Characteristics

Over the study period, there were a total of 2665 OUD-related visits in study EDs. Characteristics of patients seen in the ED for OUD-related visits are shown in Table 1. Patients were majority male, middle-aged, and publicly insured. 55% of patients were white and 41% identified as Black, with low comorbid mental health disorders, SUDs and chronic conditions captured in our health system. In the prior year, median number of ED visits was 1 and hospital admissions was 0 within the study health system. Patient characteristics did not differ significantly across the pre and post periods (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of patients seen for OUD-related visits in study EDs

| Patient Characteristics | Overall (n=2665) |

Pre-Period (n=1326) |

Post-Period (n=1339) |

Delta | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE, mean (SD) | 41.2 (14.3) | 41.5 (14.3) | 40.9 (14.2) | 0.6 | −0.47 to 1.69 |

| MALE GENDER, n (%) | 1771 (66.5) | 864 (65.1) | 907 (67.7) | 2.6% | −1.8 to 7.0 |

| HISPANIC ETHNICITY, n (%) | 147 (5.5) | 67 (5.1) | 80 (6.0) | 0.9% | −6.5 to 8.3 |

| RACE, n (%) | |||||

| White | 1471 (55.1) | 709 (52.5) | 762 (56.9) | 4.4% | −0.7 to 9.5 |

| Black/African American | 1085 (40.7) | 576 (43.4) | 509 (38.0) | −5.4% | −11.2 to 0.4 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 22 (1.3) | 14 (1.1) | 8 (0.6) | −0.5% | −8.1 to 7.1 |

| Other/Unknown | 87 (3.3) | 27 (2.0) | 60 (4.5) | −.5% | −4.9 to 9.9 |

| INSURANCE STATUS, n (%) | |||||

| Medicaid | 1664 (62.4) | 801 (60.4) | 863 (64.5) | 4.1% | −0.6 to 8.8 |

| Medicare | 351 (13.2) | 192 (14.5) | 159 (11.9) | −2.6% | −9.7 to 4.5 |

| Commercial | 426 (16.0) | 219 (16.5) | 207 (15.5) | −1.0% | −8.0 to 6.0 |

| Uninsured/Unknown | 224 (8.4) | 114 (8.6) | 110 (8.2) | −0.4% | −7.7 to 6.9 |

| COMBORBIDITIES, n (%) | |||||

| Depression | 96 (3.6) | 52 (3.9) | 44 (3.3) | −0.6% | −8.1 to 6.9 |

| Anxiety | 83 (3.1) | 26 (2.0) | 57 (4.3) | 2.3% | −5.3 to 9.9 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 24 (0.9) | 4 (0.3) | 20 (1.5) | 1.2% | −6.8 to 3.8 |

| Schizophrenia | 21 (0.8) | 9 (0.7) | 12 (0.9) | 0.2% | −7.4 to 7.8 |

| Stimulant Use Disorder | 158 (5.9) | 81 (6.1) | 77 (5.8) | −0.3% | −7.7 to 7.1 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 106 (4.0) | 53 (4.0) | 53 (4.0) | 0% | −7.5 to 7.5 |

| Benzodiazepine/Sedative Use Disorder | 62 (2.3) | 38 (2.9) | 24 (1.8) | −1.1% | −8.6 to 6.4 |

| CHARLSON, mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.9) | 0.90 (1.9) | 0.85 (1.9) | 0.1 | −0.1 to 0.2 |

| PREVIOUS ED Visit in last 12 months, *mean (SD) | 3.5 (10.1) | 3.9 (11.1) | 3.2 (8.8) | 0.7 | −0.10 to 1.5 |

| PREVIOUS HOSPITAL ADMISSIONS in last 12 months, mean (SD) | 0.40 (1.55) | 0.35 (1.52) | 0.45 (1.57) | −0.10 | −0.22 to 0.02 |

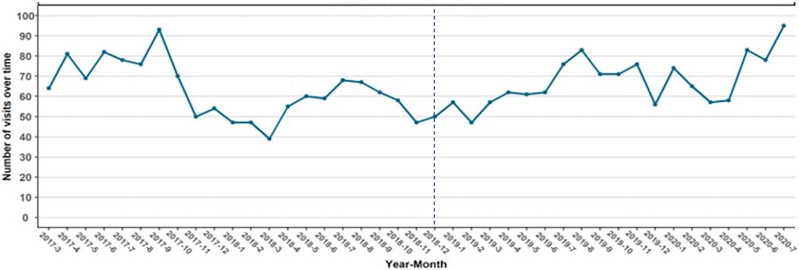

There were a total of 1326 unique visits in the pre-period and 1339 in the post-period (Table 2, Figure 1). There was some variation by season and across time, with higher monthly visits towards the end of the study period. We also broke visits down by presentation type, including overdose, withdrawal, and other OUD-related visits. There were 737 (28%) visits for drug overdose, 213 (8%) for opioid withdrawal, and 1715 (64%) for other OUD-related conditions, with the proportion of patients with overdose decreasing 15.8% (95% CI −22.3% to −9.3%) and other presentations increasing 13% (95% CI 8.9% to 17.9%) in the post-period.

Table 2:

ED visit characteristics for OUD-related visits in the study period

| Total (n=2665) |

Pre-Period (n=1326) |

Post-Period (n=1339) |

Delta | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED Presentation | |||||

| Overdose | 737 (27.7) | 472 (35.6) | 265 (19.8) | −15.8% | −22.3 to −9.3 |

| Withdrawal | 213 (16) | 90 (6.8) | 123 (9.2) | 2.4% | −4.9 to 9.7 |

| Other | 1715 (64.4) | 764 (57.6) | 951 (71.0) | 13.4% | 8.9 to 17.9 |

| COWS measured, n (%) | 253 (9.5) | 19 (1.4) | 234 (17.5) | 16.1% | −8.9 to 23.2 |

| COWS, mean (SD) | 8.0 (5.9) | 7.0 (4.53) | 8.1 (6.0) | 1.1 | −1.7 to 3.9 |

| Urine Drug Screen (UDS) Collected, n (%) | 777 (29.2) | 397 (29.9) | 380 (28.4) | −1.5% | −7.9 to 4.9 |

| UDS positive for opiates, n (%) a | 538 (69.2) | 310 (78.1) | 228 (60.0) | −18.1% | −25.9 to −10.2 |

| UDS positive for fentanyl, n (%) a,b | 197 (25.4) | 48 (12.1) | 149 (39.2) | 27.1% | 15.0 to 39.2 |

| UDS positive for stimulants, n (%) a | 168 (21.6) | 69 (17.4) | 99 (26.1) | 8.7% | −3.7 to 21.1 |

| UDS positive for benzodiazepines, n (%) a | 248 (31.9) | 132 (33.2) | 116 (30.5) | −2.7% | −14.3 to 8.9 |

| MOUD | |||||

| Any MOUD, n (%) | 337 (12.6) | 35 (2.6) | 302 (22.6) | 20.0% | 12.9 to 27.1 |

| Total buprenorphine, n (%) | 302 (11.3) | 20 (1.5) | 282 (21.1) | 19.6% | 13.1 to 26.0 |

| Buprenorphine Administered in ED, n (%) | 211 (7.9) | 16 (1.2) | 195 (14.6) | 13.4% | 6.1 to 20.7 |

| Methadone Administered in ED, n (%) | 35 (1.3) | 15 (1.1) | 20 (1.5) | 0.4% | −7.1 to 7.9 |

| Buprenorphine Prescribed at Discharge, n (%) | 209 (7.8) | 7 (0.5) | 202 (15.1) | 13.6% | 6.5 to 20.7 |

| Naloxone | |||||

| Naloxone Administered in ED, n (%) | 171 (6.4) | 108 (8.1) | 63 (4.7) | −3.4% | −10.7 to 3.9 |

| Naloxone Prescribed at Discharge, n (%) | 649 (24.4) | 232 (17.5) | 417 (31.1) | 13.6% | 7.0 to 20.2 |

| ED LOS in hours, mean (SD) | 5.4 (4.4) | 5.5 (3.9) | 5.3 (4.8) | −0.2 | −0.5 to 0.2 |

| ED 30-day Revisit, n (%) | 935 (35.1) | 468 (35.3) | 467 (34.9) | −0.4% | −6.5 to 5.7 |

| Hospital 30-day Readmission, n (%) | 175 (6.6) | 88 (6.6) | 87 (6.5) | −0.1% | −7.4 to 7.2 |

95% confidence intervals represent the differences across the pre-period and post-period

Individual UDS results calculated as the percent of total urine drug screens collected

Urine fentanyl testing only became routine in our health system in 12/2020. Prior to this fentanyl testing required a send out lab

Figure 1: Total OUD-Related ED Visits Over the Study Period.

The dashed line represents the time of implementation of the suite of interventions in December 2018.

Urine drug screens were collected for 29%, and of those tests collected, 25% contained fentanyl, 69% other opioids, 20% stimulants, and 32% with benzodiazepines, with many containing multiple substances. Of note, our institution did not routinely perform fentanyl testing until December 2019, so likely under-reports the actual prevalence of fentanyl, which was known to be widely available in Philadelphia during the study period.

ED length of stay averaged 5.4 hours and did not change significantly over time despite the introduction of our interventions (5.5 hours in the pre-period and 5.4 hours in the post-period, 95% CI −0.2 to 0.5 hours). Finally, 30-day ED revisits and hospital admissions were 35% (pre-period 35.3% and post-period 34.9%, 95% CI −6.5% to 5.7%) and 7% (pre-period 6.6% and post-period 6.5%, 95% CI −7.4% to 7.2%), respectively, with no significant differences across time periods.

Treatment and Process Outcomes

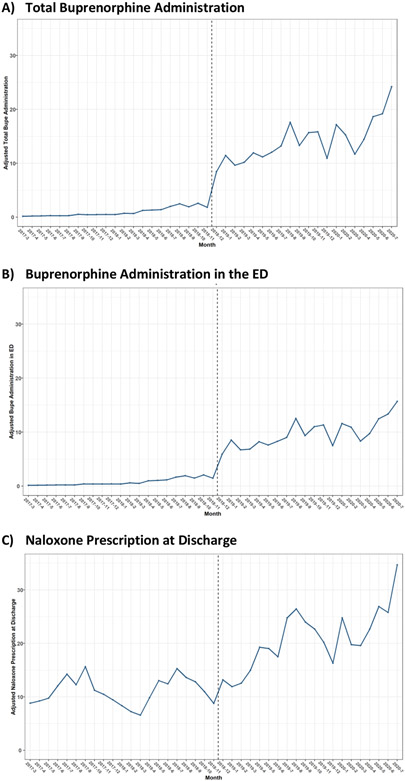

Next, we examined the impact of the multi-component strategy on treatment and process outcomes for patients with OUD-related encounters over the study period (Table 2, Figure 2). Following implementation, we observed increases in both ED administration and discharge prescribing of buprenorphine as well as naloxone prescriptions at discharge. We also observed increases in all the process measures, including COWS measurement and use of order sets, minor increase in the ED OUD induction order set, and substantial use of the discharge order set.

Figure 2: Adjusted treatment outcomes before and after ED intervention implementation.

Multivariable logistic regression models were adjusted for patient characteristics and calendar time with hospital level fixed effects. The dashed line represents the intervention period.

Overall, 13% of patients over the study period received MOUDs during or after their ED visit. Prior to implementation, this was just 3%, whereas 23% received MOUDs following intervention implementation. This net increase of 20% was statistically significant (95% confidence interval 12.9% to 27.1%). The majority received buprenorphine, either in the ED, at discharge, or both. There were no significant changes in rates of ED methadone administration. Trends were similar when we looked at absolute numbers of outcomes rather than as a proportion of total OUD-related visits.

In the patient-level interrupted time series analysis before and after implementation, the was an immediate increase in the adjusted marginal probably of total buprenorphine use of 24.5% (95% confidence interval 12.1% to 37.0%) in association with the implementation of our multi-component strategy to increase identification and treatment of patients (Figure 2), and increases were sustained throughout the post-period. We also saw significant increases in ED buprenorphine administration, with the buprenorphine administration increasing 14.6% (95% confidence interval 4.8% to 24.3%) following the intervention and rising steadily throughout the study period (Figure 2). Naloxone prescribing at discharge did not increase significant in association with the intervention but did increase over time (Figure 2). Details of the models are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Process outcomes, including COWS measurement and use of the induction and discharge order sets, also increased significantly following the intervention period (Supplemental Figure 1).

We also performed a simple ITSA at the visit-level modeling the change in proportion of visits demonstrating each outcome of interest per month before and after the intervention implementation period. Following the intervention implementation, there was an immediate and statistically significant increase in total buprenorphine use of 11.8% (95% confidence interval 6.0%-17.5%) in association with the implementation of our multi-component strategy to increase identification and treatment of patients (Figure S2). We also saw significant increases in ED buprenorphine administration in association with the intervention, and while naloxone prescribing at discharge did not increase significantly in association with the intervention, prescribing did increase over time (Figure S2).

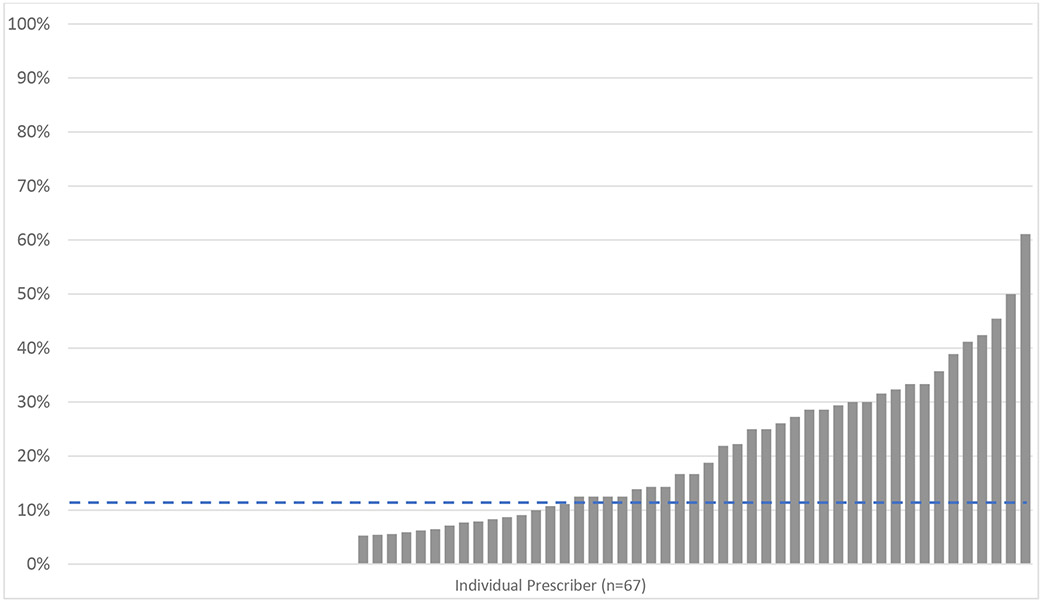

Provider-Level Variation

Finally, in order to understand provider-level variation in the adoption of practice changes, we performed a provider-level analysis of buprenorphine prescriptions per OUD-related encounter. Among attending physicians with 10 or more OUD-related encounters over the study period, we found that only 7% of providers wrote any buprenorphine prescriptions in the pre-period. In the post period, 70% of providers wrote at least one buprenorphine prescription (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Provider-level buprenorphine prescribing following ED intervention implementation.

Rate of buprenorphine prescriptions per OUD-related encounter for all providers with 10 or more OUD-related encounters in the pre and post period. Each bar represents an individual prescriber (n=67), and the dashed line represents the prescriber-level mean.

Despite this strong uptake, the mean rate of prescribing per OUD-related encounter varied substantially by providers. Overall, we saw buprenorphine prescriptions for 11% of OUD-related encounters (median 11%, interquartile range 0-29%). Individual provider-level prescribing rates ranged from 0% to 61% of OUD-related encounters.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has several important limitations. First, we present results from a single urban, academic health system in a city highly affected by the opioid crisis and our local patient population, so the results may not be generalizable to all settings. Second, our interventions could not have been implemented without financial support which included the salaries of our peer recovery support staff, the time and resources of the Center for Health Care Innovation, and the investment from the health system to provide financial incentives. Third, we were unable to measure all components of the intervention including, most notably, frequency of PRS consults or linking PRS consults with individual patient visits. Fourth, all intervention components were implemented in close proximity, making it difficult to disentangle the impact of individual elements. Additionally, we lack a control group and therefore cannot determine whether the interventions caused changes in our outcomes or whether they were due to secular trends. However, we do see an immediate and sustained increase that is closely temporally associated with the intervention implementation. Finally, we only have access to EHR data from within our health system, and therefore did not capture measures from other hospitals, and our patient identification algorithm likely missed some patients with OUD and incorrectly identified others. There is also potential for misclassification from the use of EHR data that relies on diagnostic codes or chief complaint data, including missing patients with OUD or inappropriately including people without OUD, a known limitation of EHR for identification of patients with OUD.35 However, our process and treatment outcomes still required clinical decision-making on behalf of providers, reflecting real changes in provider practice.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that a combination of strategies to increase evidence-based OUD care in the ED was associated with increases in ED initiation of treatment that were sustained over time. We observed these increases ED interventions for patients with OUD – including absolute increases in buprenorphine use by 20% and naloxone prescription upon discharge by 14% – without increased ED length of stay. However, we also saw that uptake varied substantially by at the provider level, suggesting opportunities for continued improvement.

Our study adds to the literature in several key ways. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the automation of patient identification and peer recovery specialist consultation. Much of the work describing implementation of ED buprenorphine has focused on initiatives for education, guidelines or consultative staff models.36-40 While addressing barriers to OUD treatment identified in prior studies,12,16,41 these interventions alone may not be sufficient to significantly alter provider practices, as was the case in our study EDs prior the interventions describe in this study. The peer specialists likely reduced the typical friction involved in initiation treatment by addressing both providers’ ability to prescribe buprenorphine (assisting with patient engagement and linkage to longitudinal care) as well as their motivation to do so (by providing support for not only the patient but also the prescriber in implementing practice change).

Further, although peer specialists are increasingly being utilized for OUD-related ED interventions,42 the automated consultation process in our study helped to ensure that the connection was made in the setting of numerous competing priorities. Automation makes consultation an “opt-out” rather than “opt-in” process, capitalizing on the status quo bias that makes individuals more likely to go with the default option.43 This principle has been effectively leveraged for other healthcare interventions, from opioid prescribing to end of life decision-making.44,45 Because all information used to identify patients is found within the EMR, this is a scalable strategy that other EDs could implement to identify eligible patients with OUD and connect them with services.

Despite these successes and the strong institutional support for implementation, there was still substantial provider-level in adoption of buprenorphine prescribing. Even among those who obtained an X-waiver, there was still wide variability among prescribers, with buprenorphine prescribing rates ranging from 0% to more than 60% of OUD-related encounters. In the literature, it is unclear what an appropriate target goal for treatment is and what targets should be for future quality improvement initiatives. Similar data is limited - one recent study of the implementation of a clinical decision-support tool demonstrated 6.6% of potentially eligible patients with OUD-related visits received buprenorphine.40 Similarly, naloxone was dispensed on average to 25% of patients across our study, but more than 30% of OUD-related visits by the end of the study period. Prior literature has demonstrated that naloxone is prescribed to <2% of patients at risk for overdose overall,46 with low rates nationally in ED settings.47 Although our intervention resulted in rates of treatment comparable to or better than many reported in the literature, the provider-level data suggest that by targeting variability, there are likely opportunities to increase treatment. For example, studies in other areas have demonstrated that peer-comparison data can be presented to individuals to increase their adoption of evidence-based practices.48-50 There may be opportunities to employ similar strategies to prompt the treatment with MOUD or provision of naloxone to at-risk patients in the ED.

Finally, our study provides important evidence about X-waiver training for emergency physicians. This is particularly important In light of the recent announcement from the Department of Health and Human Services eliminating training requirements for the X-waiver for buprenorphine providers prescribing for up to 30 patients14 – which would likely include the majority of ED providers. Following the implementation period in our study, buprenorphine prescribing rates increased substantially, and the majority of physicians wrote at least one prescription. However, the substantial variability described above suggests that like other settings, many providers who receive an X-waiver frequently do not make use of it and rarely prescribe close to their full capacity.15 These findings suggests that while the X-waiver is necessary, it is not sufficient. Adoption of prescribing by 70% of prescribers this study in the post period is higher than the 50% rates cited in a recent national study,15 suggesting that the additional interventions in our setting may have contributed to wider adoption of prescribing practices. As discussions of completely eliminating or “X-ing” the X-waiver, 51 continue at the federal level, it is critical to remember that the regulatory barriers around prescribing is only one of many challenges52 that needs to be addressed to promote practice change among clinicians. While this policy change is an important step to substantially expand access to evidence-based care for OUD, it will likely be most successful if coupled with other initiatives to support providers and patients with OUD.

In conclusion, implementation of a multi-component, multi-disciplinary strategy to increase delivery of OUD treatment and harm reduction practices was associated with a sustained increase in initiation of MOUDs and naloxone provision. Our results support the importance of implementing multiple components to influence and sustain behavior change and are potentially scalable across a variety of EDs nationally. The next stages for implementation may benefit from a focus at the policy and system level on reducing provider variation and strategies to move providers closer to higher treatment rates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation for the support in its accelerator program, and specifically team members Pamela Cacchione, Manik Chhabra, Yevgeniy Gitelman, Kelli Murray-Garant, Carolina Garzon, Austin Kilaru, Bryant Rivera, Dunia Tonob, Madeline Snyder, and Srikanth Gowda. The authors would also like to thank ED leadership at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, including Christopher Edwards and Sean Foster for their support of these efforts. Dr. Edwards was also instrumental in the development of order sets.

Financial Support:

This work was supported by the Penn Injury Science Center (CDC 19R49CE003083), Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation Accelerator Program, and SAMHSA (H79TI081596-01) Dr. Delgado was also supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant K23HD090272001) and by a philanthropic grant from the Abramson Family Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: All authors report no conflict of interest.

Presentations: This work was presented as an oral abstract at the Society of General Internal Medicine Virtual Annual Meeting on April 21, 2021.

References

- 1.Ahmad FB RL, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivolo-Kantor AM SP, Gladden RM, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in Emergency Department Visits for Suspected Opioid Overdoses — United States, July 2016–September 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaczorowski J, Bilodeau J, A MO, Dong K, Daoust R, Kestler A. Emergency Department-initiated Interventions for Patients With Opioid Use Disorder: A Systematic Review. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2020;27(11):1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srivastava A, Kahan M, Nader M. Primary care management of opioid use disorders: Abstinence, methadone, or buprenorphine-naloxone? Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2017;63(3):200–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin A, Mitchell A, Wakeman S, White B, Raja A. Emergency Department Treatment of Opioid Addiction: An Opportunity to Lead. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2015;313(16):1636–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch SH, Fiellin DA, Chawarski MC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of emergency department-initiated treatment for opioid dependence. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2017;112(11):2002–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder After Nonfatal Opioid Overdose and Association With Mortality: A Cohort Study. Annals of internal medicine. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Emergency Physicians. E-QUAL Network Opioid Initiative. https://www.acep.org/administration/quality/equal/e-qual-opioid-initiative/#sm.001836nzfraier110zc172wo1cqzn. Published 2018. Accessed January 13, 2019.

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Office of Disability AaL-TCP. STATE AND LOCAL POLICY LEVERS FOR INCREASING TREATMENT AND RECOVERY CAPACITY TO ADDRESS THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC: FINAL REPORT. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackey K, Veazie S, Anderson J, Bourne D, Peterson K. Barriers and Facilitators to the Use of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder: a Rapid Review. Journal of general internal medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowenstein M, Kilaru A, Perrone J, et al. Barriers and facilitators for emergency department initiation of buprenorphine: A physician survey. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawk KF, D'Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Clinician Readiness to Provide Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine. JAMA network open. 2020;3(5):e204561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of the Secretary DoHaHS. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. April 26, 2021. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan A, Anderman J, Deseran T, Reynolds I, Stein BD. Monthly Patient Volumes of Buprenorphine-Waivered Clinicians in the US. JAMA network open. 2020;3(8):e2014045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuckerman M, Kelly T, Heard K, Zosel A, Marlin M, Hoppe J. Physician attitudes on buprenorphine induction in the emergency department: results from a multistate survey. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa). 2020:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster SD, Lee K, Edwards C, et al. Providing Incentive for Emergency Physician X-Waiver Training: An Evaluation of Program Success and Postintervention Buprenorphine Prescribing. Ann Emerg Med. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American journal of public health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2016;25(12):986–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philadelphia Department of Public Health. 2016 Overdoses From Opioids in Philadelphia. CHART Web site. http://www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/chart%20v2e7.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 DIagnoses and New ICD-10-CM Codes As Ordered in the ICD-10-CM Classification. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/updates-to-dsm-5/coding-updates/as-ordered-in-the-icd-10-cm-classification. Published 2017. Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 22.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical care. 2012;50(3):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation science : IS. 2013;8:139–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogg B A behavior model for persuasive design. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology; 2009; Claremont, California, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dopp AR, Parisi KE, Munson SA, Lyon AR. Integrating implementation and user-centred design strategies to enhance the impact of health services: protocol from a concept mapping study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0403-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asch DA, Terwiesch C, Mahoney KB, Rosin R. Insourcing health care innovation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1401135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reif S, Braude L, Lyman DR, et al. Peer recovery support for individuals with substance use disorders: assessing the evidence. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC). 2014;65(7):853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jack HE, Oller D, Kelly J, Magidson JF, Wakeman SE. Addressing substance use disorder in primary care: The role, integration, and impact of recovery coaches. Substance abuse. 2018;39(3):307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waye KM, Goyer J, Dettor D, et al. Implementing peer recovery services for overdose prevention in Rhode Island: An examination of two outreach-based approaches. Addictive behaviors. 2019;89:85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chartash D, Paek H, Dziura JD, et al. Identifying Opioid Use Disorder in the Emergency Department: Multi-System Electronic Health Record-Based Computable Phenotype Derivation and Validation Study. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(4):e15794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuels EA, D'Onofrio G, Huntley K, et al. A Quality Framework for Emergency Department Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(3):237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders. In. Title 42: Public Health, Part 8 - Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program]. Vienna, Austria: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howell BA, Abel EA, Park D, Edmond SN, Leisch LJ, Becker WC. Validity of Incident Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Diagnoses in Administrative Data: a Chart Verification Study. Journal of general internal medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly T, Hoppe JA, Zuckerman M, Khoshnoud A, Sholl B, Heard K. A novel social work approach to emergency department buprenorphine induction and warm hand-off to community providers. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2020;38(6):1286–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaucher KA, Caruso EH, Sungar G, et al. Evaluation of an emergency department buprenorphine induction and medication-assisted treatment referral program. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2020;38(2):300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards FJ, Wicelinski R, Gallagher N, McKinzie A, White R, Domingos A. Treating Opioid Withdrawal With Buprenorphine in a Community Hospital Emergency Department: An Outreach Program. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(1):49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beauchamp GA, Laubach LT, Esposito SB, et al. Implementation of a Medication for Addiction Treatment (MAT) and Linkage Program by Leveraging Community Partnerships and Medical Toxicology Expertise. J Med Toxicol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holland WC, Nath B, Li F, et al. Interrupted Time Series of User-centered Clinical Decision Support Implementation for Emergency Department-initiated Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2020;27(8):753–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawk K, D'Onofrio G. Emergency department screening and interventions for substance use disorders. Addiction science & clinical practice. 2018;13(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGuire AB, Powell KG, Treitler PC, et al. Emergency department-based peer support for opioid use disorder: Emergent functions and forms. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2020;108:82–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357(13):1340–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delgado MK, Shofer FS, Patel MS, et al. Association between Electronic Medical Record Implementation of Default Opioid Prescription Quantities and Prescribing Behavior in Two Emergency Departments. Journal of general internal medicine. 2018;33(4):409–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halpern SD, Loewenstein G, Volpp KG, et al. Default options in advance directives influence how patients set goals for end-of-life care. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2013;32(2):408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Follman S, Arora VM, Lyttle C, Moore PQ, Pho MT. Naloxone Prescriptions Among Commercially Insured Individuals at High Risk of Opioid Overdose. JAMA network open. 2019;2(5):e193209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kilaru AS, Liu M, Gupta R, et al. Naloxone prescriptions following emergency department encounters for opioid use disorder, overdose, or withdrawal. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2021;47:154–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. Jama. 2013;309(22):2345–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2016;315(6):562–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Navathe AS, Volpp KG, Bond AM, et al. Assessing The Effectiveness Of Peer Comparisons As A Way To Improve Health Care Quality. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2020;39(5):852–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fiscella K, Wakeman SE, Beletsky L. Buprenorphine Deregulation and Mainstreaming Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: X the X Waiver. JAMA psychiatry. 2019;76(3):229–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act. In. 2021-2022. ed2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.