Abstract

We describe the rarity of Helicobacter pylori strains of vacuolating cytotoxin type s1a (the type most commonly associated with peptic ulceration in the United States) among black and mixed-race South Africans. We also provide the first description of a naturally occurring strain with the vacA allelic structure s2/m1.

Helicobacter pylori colonizes the human gastric mucosa, leading to chronic superficial gastritis, and is an important risk factor for peptic ulceration, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric lymphoma. Two virulence determinants have been described: a 40-kb pathogenicity island for which the gene cagA (cytotoxin-associated gene A) is a marker (5) and a secreted cytotoxin, VacA. The cytotoxin causes vacuolation of epithelial cells in vitro (12) and induces epithelial cell damage and mucosal ulceration when administered orally to mice (14). Although fewer than 50% of H. pylori clinical isolates from the United States produce HeLa cell-vacuolating activity, the gene vacA, which encodes the cytotoxin, has been found in all strains studied (6). However, vacA alleles vary between toxigenic (Tox+) and nontoxigenic (Tox−) strains, the differences being most marked in the region encoding the signal sequence and the mid-region of the gene (2). vacA alleles of strains from the United States, Europe, and Asia are mosaics consisting of any combination of the three signal sequence types (s1a, s1b, or s2) and two mid-region types (m1 or m2), with the exception of s2/m1 (2, 3). The mosaic structure of vacA could be explained by stepwise acquisition of stretches of DNA as single isolated events followed by clonal expansion or by acquisition of DNA and subsequent recombination between vacA alleles among H. pylori strains. Several lines of evidence, namely multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (7, 8) and the use of genetic markers (13), suggest that recombination is frequent in H. pylori. If recombination occurs within vacA, it is unclear why vacA s2/m1 alleles have not been found, especially since we have introduced an artificially constructed s2/m1 allele into two strains and have shown them to be viable in vitro (11). In the United States, strains with vacA s1a alleles are associated with peptic ulceration more frequently than those with s1b or s2 alleles (4). vacA diversity among H. pylori strains from South Africa has not previously been studied but may be clinically important because the scarcity of pathogenic strains could explain the “African enigma” of high levels of H. pylori infection but relatively low levels of peptic ulcer disease and gastric adenocarcinoma in Africa (10). For this reason we studied vacA allele diversity among South African H. pylori isolates.

We examined single-colony H. pylori isolates from 16 South African patients having a median age of 36 years (range, 20 to 63 years). Fifteen patients were black or of mixed race, and 1 was caucasian; 11 were male, 11 had active duodenal ulcers, and 5 were asymptomatic without ulcers. None were taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. For three patients, two morphologically distinct colonies were isolated and examined separately. Chromosomal DNA was extracted from 48-h plate cultures of each strain by a previously described guanidine thiocyanate-EDTA-Sarkosyl lysis method (1). For each isolate, the vacA signal sequence and mid-region were characterized by PCR as previously described (2). The presence or absence of cagA was determined for each isolate by DNA hybridization: samples of each genomic DNA were applied to a nylon membrane and hybridized with a 349-bp digoxigenin-labelled cagA probe derived from H. pylori 84183 (2).

vacA and cagA genotypes were successfully and fully determined for each isolate; results are shown in Table 1. For the three patients from whom two morphologically distinct colonies were isolated, both colonies showed the same vacA and cagA genotype, and for clarity, only one isolate has been included in Table 1. A single vacA s1a/m1 strain was found; it was isolated from the one caucasian patient in the study. Of the 15 black or mixed-race South Africans in this study, 10 had vacA s1b/m1 isolates, 4 had s1b/m2 isolates, and 1 had s2/m1 isolates (two isolates from the same patient).

TABLE 1.

vacA and cagA genotypes and vacuolating activity of H. pylori isolates from South Africa

| H. pylori isolate | Clinical disease of infected patienta |

vacA genotype

|

Vacuolating activityb | cagA genotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal | Mid-region | ||||

| HP218 | DU | s1b | m2 | − | + |

| HP220 | DU | s1b | m1 | − | + |

| HP233 | DU | s1b | m2 | − | + |

| HP442 | DU | s1b | m1 | ND | + |

| HP458cd | DU | s1b | m1 | + | + |

| HP460 | DU | s1b | m1 | − | + |

| HP464 | DU | s1b | m1 | ND | + |

| HP465c | DU | s2 | m1 | − | − |

| HP466 | DU | s1b | m1 | − | + |

| HP467c | No ulcer | s1b | m1 | ND | − |

| HP468 | DU | s1b | m2 | − | + |

| HP469 | DU | s1b | m2 | − | − |

| HP501 | No ulcer | s1b | m1 | ND | − |

| HP508 | No ulcer | s1b | m1 | + | + |

| HP517 | No ulcer | s1b | m1 | − | + |

| HP548 | No ulcer | s1b | m1 | − | − |

DU, duodenal ulcer. No ulcer patients were asymptomatic.

H. pylori isolates were defined as producing vacuolating activity (+) when >80% vacuolation of AGS cells was observed after application of unconcentrated broth culture supernatant (diluted twofold or more). ND, not assayed.

A second, morphologically distinct colony from the same original culture plate was characterized separately and found to be the same (data not shown).

This isolate was from the one caucasian patient in the study. All other strains were isolated from black or mixed-race South Africans.

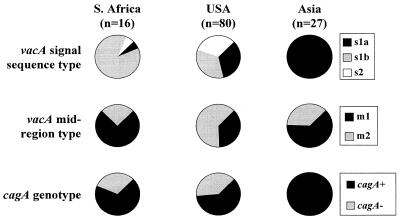

We compared the vacA and cagA genotypes of South African strains from this study with those of previously reported strains from the United States (2, 4) and Asia (3) (Fig. 1). There are striking geographical differences. The absence of the vacA s1a allele among isolates from black and mixed-race subjects from South Africa contrasts with the finding of s1a alleles among all Asian strains studied (P < 10−10, Fisher’s exact test). The prevalence of type s1a vacA alleles among South African strains was also significantly less than that among strains from the United States, where a more even spread of strains with the three different signal types was found (34% s1a; P < 0.01). These comparative data between strains from different continents are potentially influenced by disease state, as there is a recognized link between the vacA s1a genotype and peptic ulceration in the United States (4). However, if this is controlled for by considering only patients with peptic ulcers, the results are even more striking. Among such patients, none of 10 black or mixed-race South Africans had strains with vacA s1a alleles, which is less than the 100% of 14 strains from Asians (P < 10−6, Fisher’s exact test) and the 58% of 40 strains from North Americans (P < 0.005). In contrast to this finding for the vacA signal region, both vacA mid-region types were observed among South African strains, as was the case for strains from Asia and North America. cagA+ strains were observed in South Africa at a frequency similar to that for strains from the United States, whereas all the strains we have studied from Asia were cagA+ (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of vacA signal sequence and mid-region allelic types and cagA genotype between H. pylori isolates from South Africa, the United States (USA), and Asia (Japan [n = 13], China [n = 5], and Thailand [n = 9]).

The only subject with a type s2 vacA signal region appeared to have an s2/m1 vacA allele; natural occurrence of vacA alleles with this structure has not previously been reported. To confirm the genotype of this isolate, the 246-bp signal region and 463-bp mid-region PCR products from duplicate reactions were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and sequenced. The nucleotide and deduced polypeptide sequences were then compared with the corresponding regions of the published vacA sequences from United States strains 60190 (s1a/m1) and Tx30a (s2/m2) by using the Clustal V algorithm (9). The signal region showed greatest identity (87.4% at the nucleotide level) with the typical United States s2 strain Tx30a, including the characteristic 9-codon insertion, which encodes a signal processing site different from that of the s1 signal sequence (2). The mid-region showed greatest identity (99.1% at the nucleotide level) to the typical United States m1 strain 60190.

For a subset of isolates (a maximum of four strains of each genotype), cytotoxin activity was determined by applying 48-h unconcentrated broth culture supernatants to cultured AGS cells, incubating the cells for 24 h at 37°C, and recording the level of vacuolation observed (2). Two of the strains were cytotoxic in this assay (defined as >80% of HeLa cells exhibiting vacuolation), the vacA s1a/m1 strain and one of the s1b/m1 strains; thus, the s2/m1 strain was noncytotoxic (Table 1).

To conclude, vacA diversity was demonstrated among South African H. pylori strains, but the pattern was different from that found among strains from the United States or Asia. In particular, strains with the vacA s1a genotype were not found among H. pylori isolates from black or mixed-race South Africans in this sample. High levels of H. pylori infection exist in Africa, yet the incidences of peptic ulcer disease and gastric adenocarcinoma are both thought to be low (10). It is interesting to speculate that this may be explained by a low prevalence of H. pylori strains with the vacA s1a allele. (Infection with strains with the vacA s1a allele has been shown to be associated with peptic ulceration in a United States population [4].) A larger study to examine the association between vacA genotype, race, and disease in South Africa is currently in progress. Perhaps the most important discovery in this study was the natural existence of a strain with a vacA s2/m1 genotype. The finding that all combinations of vacA signal sequence and mid-region do occur naturally strongly supports the concept of recombination occurring between vacA genes in vivo to create the mosaic gene structures observed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rachel Twells and Brian Dove for their technical assistance.

This work was funded by the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) and the British Digestive Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atherton J C. Molecular methods for detecting ulcerogenic strains of H. pylori. In: Clayton C L, Mobley H L T, editors. Helicobacter pylori protocols. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press Inc.; 1997. pp. 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atherton J C, Cao P, Peek R M, Tummuru M K R, Blaser M J, Cover T L. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori: association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17771–17777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atherton J C, Karita M, Gonzalez-Valencia G, Morales M R, Ray K C, Peek R M, Perez-Perez G I, Cover T L, Blaser M J. Diversity in vacA mid-region but not in signal sequence type among Helicobacter pylori strains from Japan, China, Thailand and Peru. Gut. 1996;39:A73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherton J C, Peek R M, Jr, Tham K T, Cover T L, Blaser M J. Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vacA, the vacuolating cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:92–99. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree J E, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cover T L, Tummuru M K R, Cao P, Thompson S A, Blaser M J. Divergence of genetic sequences for the vacuolating cytotoxin among Helicobacter pylori strains. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10566–10573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go M F, Kapur V, Graham D Y, Musser J M. Population genetic analysis of Helicobacter pylori by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis: extensive allelic diversity and recombinational population structure. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3934–3938. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3934-3938.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazell S L, Andrews R H, Mitchell H M, Daskalopoulous G. Genetic relationship among isolates of Helicobacter pylori: evidence for the existence of a Helicobacter pylori species-complex. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. Fast and sensitive multiple sequence alignments on a microcomputer. CABIOS. 1989;5:151–153. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holcombe C. Helicobacter pylori: the African enigma. Gut. 1992;33:429–431. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Letley D P, Twells R J, Dove B K, Hawkey C J, Cover T L, Atherton J C. Determinants of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin production analysed by construction of vacA hybrids and by site-directed mutagenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:A1020–A1021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leunk R D, Johnson P T, David B C, Kraft W G, Morgan D R. Cytotoxic activity in broth-culture filtrates of Campylobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 1988;26:93–99. doi: 10.1099/00222615-26-2-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salaün L, Audibert C, Le Lay G, Burucoa C, Fauchère J, Picard B. Panmictic structure of Helicobacter pylori demonstrated by the comparative study of six genetic markers. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;161:231–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Telford J L, Ghiara P, Dell’Orco M, Comanducci M, Burroni D, Bugnoli M, Tecce M F, Censini S, Covacci A, Xiang Z, Papini E, Montecucco C, Parente L, Rappuoli R. Gene structure of the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin and evidence of its key role in gastric disease. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1653–1658. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]