Abstract

Background

Burnout is a work-related syndrome documented to have negative consequences for GPs and their patients.

Aim

To review the existing literature concerning studies published up to December 2020 on the prevalence of burnout among GPs in general practice, and to determine GP burnout estimates worldwide.

Design and setting

Systematic literature search and meta-analysis.

Method

Searches of CINAHL Plus, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus were conducted to identify published peer-reviewed quantitative empirical studies in English up to December 2020 that have used the Maslach Burnout Inventory — Human Services Survey to establish the prevalence of burnout in practising GPs (that is, excluding GPs in training). A random-effects model was employed.

Results

Wide-ranging prevalence estimates (6% to 33%) across different dimensions of burnout were reported for 22 177 GPs across 29 countries were reported for 60 studies included in this review. Mean burnout estimates were: 16.43 for emotional exhaustion; 6.74 for depersonalisation; and 29.28 for personal accomplishment. Subgroup and meta-analyses documented that country-specific factors may be important determinants of the variation in GP burnout estimates. Moderate overall burnout cut-offs were found to be determinants of the variation in moderate overall burnout estimates.

Conclusion

Moderate to high GP burnout exists worldwide. However, substantial variations in how burnout is characterised and operationalised has resulted in considerable heterogeneity in GP burnout prevalence estimates. This highlights the challenge of developing a uniform approach, and the importance of considering GPs' work context to better characterise burnout.

Keywords: burnout, professional; family medicine; family physicians; family practice; general practice; general practitioners

INTRODUCTION

GP burnout (including physicians and other medical specialties) is a recognised healthcare problem that has become widespread over time and for which the adverse effects on clinicians1–13 and patients2,14 have been documented. Given these deleterious effects, estimating the prevalence of GPs’ burnout is important. Burnout is generally referred to as an inability to cope with chronic psychological stress at work because of insufficient resources to cope with job demands.15,16 Researchers have denoted that burnout captures three dimensions/subscales: emotional exhaustion, cynicism/depersonalisation, and personal accomplishment.17–19

This characterisation of burnout is also used in health care, as is aptly captured in the World Health Organization’s 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (https://icd.who.int). GP tasks are related to treating illness in the context of the patient’s life, belief systems, and community (thus it is person focused rather than disease focused),20,21 and working with other healthcare professionals to coordinate care and make efficient use of health resources.22,23 Although surveys on physician burnout in the US conducted by other researchers have reported that physician specialties that frequently deal with patients and their families, such as GPs, experienced considerably higher burnout rates than other specialties, it is unclear how prevalent GP burnout is.12,24

This systematic review aimed to conduct a synthesis of the evidence on the prevalence of GP burnout documented in the literature. In doing so it aimed to deliver a baseline picture of burnout in the GP context to establish the burden GP burnout imposes on the healthcare system. This, in turn, may benefit policymakers, healthcare institutions, clinicians, researchers, and the public to develop interventions to address the syndrome. This is especially important in the post-COVID-19 environment, which has witnessed considerably greater burden placed on GPs via more frequent patient visits and other requirements.

How this fits in

| GP burnout is widely recognised as a problem in health care. However, to the authors’ knowledge, no study has been conducted on the global burden of this condition. The systematic review and meta-analysis conducted show that moderate to high levels of burnout exist worldwide. However, a challenge to policymakers is the wide variation in burnout estimates across studies and countries documented in this review. The findings from this review highlight that the context within which GPs work should be considered in better understanding GP burnout. |

METHOD

Data sources and searches

The search strategy for this systematic review was conducted using a combination of keywords and subject headings to include two concepts: ‘general practice or GP’ and ‘burnout’. Primary care physicians typically include GPs as well as other physicians such as paediatricians, emergency physicians, and internal medicine specialists. However, this study focuses specifically on physicians who typically undertake generalist patient care such as GPs, and excludes the other subspecialties of primary care.

Only studies that reported prevalence estimates on GP burnout in general practice using the Maslach Burnout Inventory — Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) were included in this review. Although different burnout scales have been used in prior research, the MBI-HSS was used in this review to allow comparisons in burnout prevalence estimates across studies. Moreover, the MBI-HSS is the most widely used burnout instrument in the literature that measures burnout by capturing the different dimensions of burnout that have been identified in the literature, namely, emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and personal accomplishment.

The following databases were searched for potentially relevant articles, followed by screening the reference lists of identified articles: CINAHL Plus, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus. The study eligibility criteria and selection are outlined in Supplementary Appendix S1. Details pertaining to the search terms, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and search strategy used for each database are also outlined in Supplementary Appendix S1. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each article using a standardised form by one of the reviewers (the first author): geographic location; survey period; sample size with response rate; average age of participants (GPs); number and proportion of male participants; average number of years the participants have worked in general practice; practice size; number of hours worked per week; version of MBI-HSS instrument used to measure burnout; cut-off criteria to denote subcomponents of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and personal accomplishment) and overall burnout (defined using the criteria used in the study); and mean and proportion estimates of subcomponents of burnout and overall burnout for all the GPs and for male versus female GPs.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The risk of bias of the included studies was assessed by one reviewer (the first author) using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data, which scored studies based on nine items that assessed quality. This checklist is described in Supplementary Appendix S2. Full details of the scoring method used and the quality appraisal results for the studies included in this review are provided in Supplementary Appendices S2–S4.

Pooled analysis

A meta-analysis of high-quality studies, defined using a threshold of seven out of nine items (77.8%) that satisfied the respective quality criteria pertaining to the JBI checklist, was conducted. Stata statistical software (version 16.0) was used to obtain pooled burnout estimates. The meta-analysis commands used are summarised in Supplementary Appendix S5. Pooled mean estimates of the burnout subscales were computed using the metan command for means and standard error, with the standard errors having been calculated in advance using the standard deviations. Prevalence estimates (rates) were computed from these numbers using the metaprop command, reflecting the pooled proportion of GPs who were reported to have experienced burnout. Accounting for potential heterogeneity across studies, a random-effects model was employed to estimate variances of the raw proportions or means.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

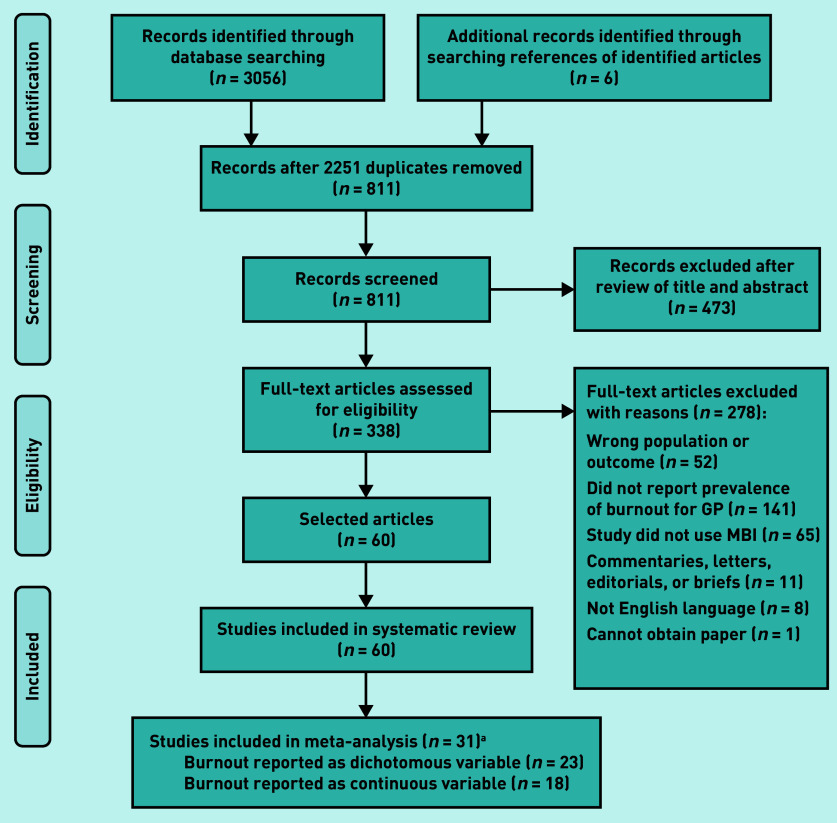

The PRISMA flow diagram detailing the selection process for the 60 articles included in the systematic review25–84 is given in Figure 1. Thirty-one of the 60 (51.7%) identified studies met the threshold of ‘high quality’.31,33,35,38–40,42,43,45,47–49,51–56,58–63,65,70,72–75,83 Of these studies, 74.2% (n = 23/31) reported the number of GPs that had high or moderate burnout along ≥1 of the burnout subcomponents (emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and personal accomplishment) and overall burnout; 58.1% (n = 18/31) reported mean and standard deviation estimates for ≥1 of the burnout subcomponents (data not shown).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram on identification and selection of articles. an-values are greater than 31 because studies can report burnout as both a dichotomous and continuous variable. MBI = Maslach Burnout Inventory — Human Services Survey.

Supplementary Appendix S6 provides a description of selected demographic data extracted from the 60 included studies in this review; burnout cut-offs, mean, and proportion estimates are provided in Supplementary Appendices S7 and S8. Estimates are provided separately for male and female GPs if they are reported in the respective study.

Study time periods ranged from 1987 to 2020, comprising data from 22 177 GPs across 29 countries spanning five continents. The majority of these studies (70.0%, n = 42/60) were conducted in Europe, 18.3% (n = 11/60) were conducted in Asia, with the remaining studies conducted in the following three continents: Africa 1.7% (n = 1/60), North America 3.3% (n = 2/60), and Oceania 6.7% (n = 4/60). Where a study was conducted over different time periods, data for the earliest period were extracted (Supplementary Appendix S6). Most of the studies (70.0%, n = 42/60) used the 22-item version of the MBI-HSS (Supplementary Appendix S6).

The studies predominantly used the following standard cut-offs19 to denote high burnout for the three burnout subscales: emotional exhaustion ≥27 (38.3%, n = 23/60), depersonalisation ≥10 (30.0%, n = 18/60), and personal accomplishment ≤33 (28.3%, n = 17/60) (Supplementary Appendix S7). As for high overall burnout, the studies (28.3%, n = 17/60) generally used the following criteria: high emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation, and low personal accomplishment.

The reported findings collectively show that there is wide variation in the demographic data, as well as burnout cut-offs and estimates, extracted from the studies included in the review. Selected demographic characteristics reported in the 31 high-quality studies are provided in Supplementary Appendix S9. The heterogeneity in demographic and burnout data observed for the 60 included studies remained for the higher-quality 31 studies included in the meta-analysis. However, the ranges of the burnout estimates reported in these studies are considerably narrower than those reported for all 60 studies.

Pooled results

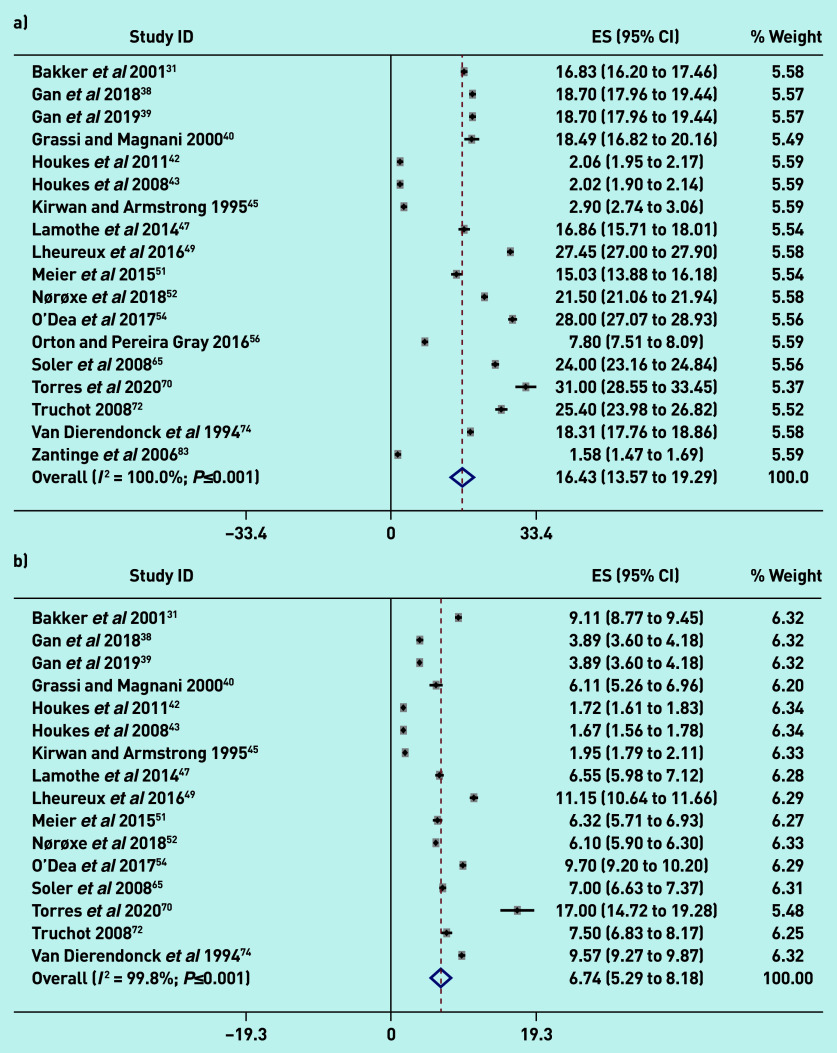

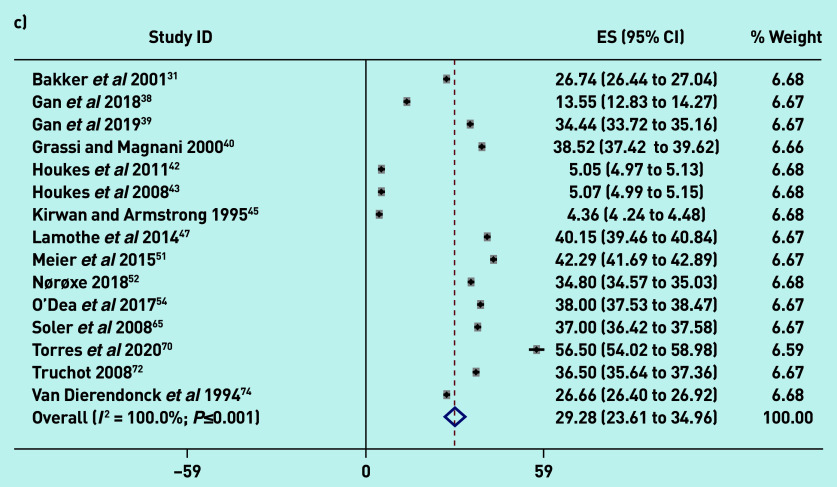

Figure 2 reports the pooled random-effect mean estimates using continuous data based on the scores obtained for the difference burnout subscales: 16.43 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 13.57 to 19.29; I2 = 100.0%; P≤0.001) for emotional exhaustion; 6.74 (95% CI = 5.29 to 8.18; I2 = 99.8%; P≤0.001) for depersonalisation; and 29.28 (95% CI = 23.61 to 34.96; I2 = 100.0%; P≤0.001) for personal accomplishment.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of GP burnout using continuous data: a) emotional exhaustion; b) depersonalisation; and c) personal accomplishment. Weights are from random-effects analysis. a

a Additionally, while the 31 studies comprised the total set of studies on which the meta-analysis was conducted across all dimensions of burnout, some types of estimates were not reported in some studies. Some studies reported only proportions and/or percentages whereas others reported only mean estimates, and yet others reported both proportions and mean estimates. The total number of studies is 31, which would be reflected by all the studies captured in Figure 2 and also Supplementary Appendix S11. ES = mean score.

These estimates denote moderate levels of burnout for emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation, and a high level of burnout for personal accomplishment, based on standard burnout cut-offs for these subscales, indicating significant levels of burnout among GPs. As evident in the high I2 (>99%), there is considerable heterogeneity across studies. Supplementary Appendix S10 shows that the mean burnout estimates for the different burnout subscales varied depending on the country’s geographical region (P-value for heterogeneity ≤0.001). Meta regressions results showed that the continent in which studies were conducted had no effect on variation in mean burnout estimates across studies. There were insufficient observations within subgroups to conduct meta regressions for country. Overall, there was no evidence that the geographical region influenced variation in mean burnout estimates across studies.

Studies reported the following pooled prevalence estimates for GPs that exceeded the threshold for high or moderate burnout (Supplementary Appendix S11): high emotional exhaustion 32% (95% CI = 26 to 39; I2 = 97.95%; P≤0.001); high depersonalisation 31% (95% CI = 19 to 43; I2 = 99.49%; P≤0.001); low personal accomplishment 27% (95% CI = 22 to 32; I2 = 96.86%; P≤0.001); high overall burnout 6% (95% CI = 4 to 9; I2 = 95.42%; P≤0.001); moderate emotional exhaustion 28% (95% CI = 22 to 35; I2 = 95.79%; P≤0.001); moderate depersonalisation 23% (95% CI = 15 to 31; I2 = 97.55%; P≤0.001); moderate personal accomplishment 33% (95% CI = 22 to 44; I2 = 98.51%; P≤0.001); and moderate overall burnout 32% (95% CI = 19 to 44; I2 = 99.40%; P≤0.001).

As evident in the high I2 (>95%), there is considerable heterogeneity across studies. The results (in Supplementary Appendix S10) of subgroup analyses conducted with at least 10 studies to investigate this heterogeneity show that the prevalence of burnout dimensions varied depending on the country’s geographical region and cut-off for moderate overall burnout (P-value for heterogeneity ≤0.001). Although some covariates were dropped because of collinearity, meta regressions conducted using the metareg command showed that the continent in which the studies were conducted was generally not an important determinant of high or moderate burnout (P>0.20); however, high depersonalisation was significantly lower in Europe (regression coefficient −0.565; 95% CI = −0.768 to −0.362; P≤0.001) and North America (regression coefficient −0.354; 95% CI = −0.646 to −0.063; P≤0.001) compared with Asia, and moderate overall burnout was significantly lower in Europe (regression coefficient −0.424; 95% CI = −0.803 to −0.046; P = 0.03) compared with Asia.

Taken together, the findings indicate that, although the continent in which the studies were conducted is not a robust determinant of GP burnout across studies, there is some evidence that GP burnout is lower in Europe and higher in Asia.

The subgroup analysis by country revealed that the country the study was conducted in did not influence high emotional exhaustion; high depersonalisation was significantly higher in China (regression coefficient 0.543; 95% CI = 0.386 to 0.700; P≤0.001) than in the other countries included in the meta regression; low personal accomplishment was significantly higher in China (regression coefficient 0.213; 95% CI = 0.088 to 0.339; P = 0.01), Denmark (regression coefficient 0.220; 95% CI = 0.117 to 0.324; P≤0.001), and England (regression coefficient 0.211; 95% CI = 0.080 to 0.341; P = 0.01) than in other countries. Overall, there is some evidence that GPs from China experienced higher depersonalisation than GPs from other countries (Supplementary Appendix S10).

In addition, overall, there was high residual heterogeneity for high burnout (≥95% for continent and ≥70% for country) and moderate burnout (≥84% for continent) There was no residual heterogeneity (0.00%) and high explained between-study variance for the cut-off for moderate overall burnout (adjusted R 2 99.93%), indicating that this cut-off may be an important determinant of heterogeneity in moderate overall burnout estimates across studies. The findings also reveal that less restrictive burnout criteria used in the studies are associated with higher GP burnout prevalence. For example, the more restrictive criteria for moderate overall burnout used in the studies of high emotional exhaustion and/or high depersonalisation have a smaller regression coefficient of 0.170 compared with the less restrictive criteria of high emotional exhaustion and/or high depersonalisation and/or low personal accomplishment, which has a regression coefficient of 0.355 (Supplementary Appendix S10).

Tests of publication bias via funnel plots85 and Egger tests86 were conducted and results provided in Supplementary Appendix S12. The results provide no evidence of publication bias using the dichotomous data. Visual inspection of the funnel plots showed no asymmetry in all distributions for burnout studies. Furthermore, the Egger tests did not show significant results and thus suggested no evidence of publication bias among the studies on burnout proportions. However, Egger tests on studies using the continuous data showed some evidence of possible small-study effects, with significant results (P≤0.001) for mean emotional exhaustion, mean depersonalisation, and mean personal accomplishment.

As another sensitivity test, the meta-analysis was conducted including studies of lower quality (rated ≤6 on the JBI) that were more susceptible to risk of bias. The results (Supplementary Appendix S13) showed that the burnout estimates were similar and still displayed significant heterogeneity for all studies (including those of lower quality) as for only higher-quality studies.

DISCUSSION

Summary

The 60 studies included in this systematic review reported a wide range of demographic characteristics, burnout cut-offs, and prevalence estimates. Some studies characterised burnout as uni- or bi-dimensional, although the vast majority of studies characterised burnout as multidimensional. Other studies contribute to the ambiguity with how burnout is characterised by partitioning burnout into high, moderate, and low dimensions, or using different labels (for example, ‘severe’, ‘high’, ‘extreme’, ‘full’, or ‘complete’ were used to denote high burnout). These variations across studies were observed despite narrowly focusing on only one burnout instrument, the MBI-HSS, and one specialty, general practice.

In the present study there appears to be some evidence that the country the study was conducted in may influence this heterogeneity. It is conceivable that different national cultural factors (for example, general practice being perceived as a calling versus a profit-making enterprise) may influence how workload is perceived and thus burnout experienced by GPs. Furthermore, the different features of the primary care system across countries may influence the GP’s work environment, which in turn may influence the likelihood of burnout. This review has provided evidence that the cut-offs used to denote burnout play an important role in influencing GP burnout estimates across studies. The more restrictive the burnout criteria used, the lower the burnout estimate reported across studies.

Strengths and limitations

This study is, to the authors’ knowledge, the first to undertake a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the prevalence of GP burnout worldwide. Another strength of this study is that it attempted to conduct a rigorous examination of the burden of GP burnout worldwide based on a clearly defined concept of burnout using the MBI-HSS, and focusing only on general practice.

This study, however, has several limitations. First, the studies included in this review were not conducted concurrently. Hence, the findings may be subject to different interpretations across different time periods. Second, the different demographics, at the GP and other levels, across the studies may have influenced how burnout is perceived, and may in turn influence the generalisability of the findings.

Third, although every attempt was made to select studies that were similar in their methodological approach for the quantitative analysis, several differences in the study design remained and reduced comparability across the studies.

Fourth, given this review’s focus on studies using the MBI-HSS, the insights derived in this review should be interpreted with caution, especially given the criticism some researchers have directed toward the MBI-HSS instrument and who have used other instruments such as the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory and the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory. Related to this, the MBI-HSS is subject to criticism of bias generated by self-ratings by responders on the questionnaire used in the assessed studies. To focus narrowly on burnout, studies on constructs related to burnout, such as psychological or occupational stress, were not included in the review. To the extent that these studies also capture GP experiences similar to burnout, this review could be criticised as ignoring a vast literature that may be relevant. In a similar vein, what constitutes burnout has been debated in the literature, and the literature that conflates burnout and depression was excluded. It is conceivable that there is an important overlap between GP mental health, psychological distress, and burnout. More importantly, burnout may be more a manifestation of the GP’s underlying mental condition than solely as a result of the workplace context. Hence, the generalisability of this review’s findings beyond studies using only the MBI-HSS could be called into question. Related to this, this literature may also include articles on burnout using the MBI-HSS that may not have been identified in the search strategy used in this systematic review. The MBI-HSS, used in this review, was designed to capture burnout associated with interpersonal relations. However, GP burnout also arises as a result of factors external to human relations such as workload and electronic documentation. Thus, the MBI-HSS may not fully capture GP burnout.

Fifth, studies conducted in a language other than English were not included, which may limit this review’s generalisability to other studies not conducted in English.

Finally, this review only considered peer-reviewed publications and did not consider published data from non-peer-reviewed outlets, which also may have introduced another type of selection or publication bias.

Comparison with existing literature

The wide ranges in burnout estimates reported in this review are consistent with those reported in two recent systematic reviews on the prevalence of physician burnout across a range of specialties.87,88 The evidence provided in these studies and the present study may reflect the heterogeneity across studies in the criteria used to define and measure burnout, and thus highlight the importance of uniformity in how burnout is measured and defined across studies.

Implications for research and practice

This study has shown that the approaches used in prior studies to characterise and operationalise GP burnout are inconclusive, with the reported wide-ranging prevalence estimates possibly influenced by a range of factors, such as using different measurement scales, differing cut-off points to define burnout, differing approaches to how burnout is characterised, and different cultural attributes across countries. An implication of this finding for research, practice, and policy pertaining to addressing GP burnout is that assessing and addressing the syndrome should be undertaken by considering the context GPs work in.

The work environment is challenging for the GP, as the GP’s decisions and actions are influenced by those of the patients and other agents that operate within the primary care system who may have different expectations and demands.22,89 These differences in values and priorities between the GP and other individuals in the primary care system can result in difficult interactions between the GP and these individuals. Additional research on the reasons for high/moderate burnout was beyond the scope of this study, but could be related to differences in priorities between the individual GP and the practice the GP is employed at. For example, the emphasis on efficiency could be perceived by GPs as being at the expense of patient welfare, leading to a potential mismatch in values between the practice and the GP. This could interact with the work-related burden imposed on the GP, perhaps exacerbating the level of burnout.

Recent studies have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has also played an important role in influencing physician burnout. For example, one study showed that infection or death from COVID-19 among colleagues or relatives showed significant association with higher emotional exhaustion and lower personal accomplishment.90 Two other studies reported that GPs described feeling more stressed during the pandemic than they had been previously because of the higher workload (for example, as a result of new responsibilities such as additional safety protocols, learning new technology, and daily emails for prescriptions).91,92 The extraordinary impact of the COVID-19 emergency on GPs, as frontline medical providers, was in part produced by the uncertainty of the procedures and treatments required and the immediate saturation of hospitals for critical case management. GPs had to respond directly to a large number of requests without clear prevention or screening instruments. At the time of writing, GPs were the foundation of COVID-19 vaccination programmes in several countries and remain heavily involved in administering vaccines, with some even involved in COVID-19 diagnoses, thus increasing their workload even further. Differences across countries in the severity of the disease as well as the resources available and methods used to curb and treat it (including inefficiencies associated with supplying vaccines to GPs), and operating under different primary care systems, are likely to exacerbate the impact of COVID-19 on GP burnout across countries. Probing GP burnout in more detail within the GP’s workplace environment is left for future research.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Data

The dataset is available upon request.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: a potential threat to successful health care reform. JAMA. 2011;305(19):2009–2010. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell DA, Jr, Sonnad SS, Eckhauser FE, et al. Burnout among American surgeons. Surgery. 2001;130(4):696–702. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, et al. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linzer M, Visser MR, Oort FJ, et al. Predicting and preventing physician burnout: results from the United States and the Netherlands. Am J Med. 2001;111(2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00814-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: a prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1338–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg R, Boss W, Chan L, et al. Burnout and its correlates in emergency physicians: four years’ experience with a wellness booth. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(12):1156–1164. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caplan R. Stress, anxiety and depression in hospital consultants. Br Med J. 1994;309(6964):1261–1263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6964.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Firth-Cozens J. Individual and organizational predictors of depression in general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(435):1647–1651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper CL, Rout U, Faragher B. Mental health, job satisfaction, and job stress among general practitioners. BMJ. 1989;298(6670):366–370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6670.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):30–38. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work–life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting system. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halbesleben JRB, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29–39. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304493.87898.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felton JS. Burnout as a clinical entity — its importance in health care workers. Occup Med. 1998;48(4):237–250. doi: 10.1093/occmed/48.4.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Devel Intern. 2009;14(3):204–220. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 2nd edn. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd edn. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: the challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. 2001;323(7313):625–628. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephenson A. A textbook of general practice. 3rd edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenhalgh T. Primary health care: theory and practice. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell Davies G, Williams AM, Larsen K, et al. Coordinating primary health care: an analysis of the outcomes of a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2008;188(8):S65–S68. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work–life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdulghafour YA, Bo-Hamra AM, Al-Randi MS, et al. Burnout syndrome among physicians working in primary health care centers in Kuwait. Alexandria J Med. 2011;47(4):351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abidli Z, Jadda S, Kharbouch D, et al. The evaluation of burnout syndrome among health professionals in Casablanca, Rabat and Kenitra. Res J Pharm Technol. 2019;12(11):5219–5222. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adam S, Mohos A, Kalabay L, Torzsa P. Potential correlates of burnout among general practitioners and residents in Hungary: the significant role of gender, age, dependant care and experience. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):193. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0886-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al Dabbagh AM, Hayyawi AH, Kochi M. Burnout syndrome among physicians working in primary health care centers in Baghdad, Al-Rusafa Directorate, Iraq. Indian J Public Health Res Devel. 2019;10(7):502–507. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arigoni F, Bovier PA, Mermillod B, et al. Prevalence of burnout among Swiss cancer clinicians, paediatricians and general practitioners: who are most at risk? Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(1):75–81. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arigoni F, Bovier PA, Sappino AP. Trend of burnout among Swiss doctors. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140:w13070. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Sixma HJ, Bosveld W. Burnout contagion among general practitioners. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2001;20(1):82–98. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barcons C, García B, Sarri C, et al. Effectiveness of a multimodal training programme to improve general practitioners’ burnout, job satisfaction and psychological well-being. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-1036-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brøndt A, Sokolowski I, Olesen F, Vedsted P. Continuing medical education and burnout among Danish GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2008. DOI: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Cagan O, Gunay O. The job satisfaction and burnout levels of primary care health workers in the province of Malatya in Turkey. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31(3):543–547. doi: 10.12669/pjms.313.6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dreher A, Theune M, Kersting C, et al. Prevalence of burnout among German general practitioners: comparison of physicians working in solo and group practices. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farahat T, Hegazy NN, Mohamed D. Burnout and quality of life among physicians in primary healthcare facilities in Egypt: a cross-sectional study. Menoufia Med J. 2017;30(3):789–793. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galleta-Williams H, Esmail A, Grigoroglou C, et al. The importance of teamwork climate for preventing burnout in UK general practices. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(Suppl_4):iv36–iv38. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gan Y, Gong Y, Chen Y, et al. Turnover intention and related factors among general practitioners in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, et al. Prevalence of burnout and associated factors among general practitioners in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1607. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grassi L, Magnani K. Psychiatric morbidity and burnout in the medical profession: an Italian study of general practitioners and hospital physicians. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69(6):329–334. doi: 10.1159/000012416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamilton-West K, Pellatt-Higgins T, Pillai N. Does a modified mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) course have the potential to reduce stress and burnout in NHS GPs? Feasibility study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;19(6):591–597. doi: 10.1017/S1463423618000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houkes I, Winants Y, Twellaar M, Verdonk P. Development of burnout over time and the causal order of the three dimensions of burnout among male and female GPs. A three-wave panel study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:240. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Houkes I, Winants Y, Twellaar M, et al. Specific determinants of burnout among male and female general practitioners: a cross-lagged panel analysis. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2008;81(2):249–276. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karakose T. An evaluation of the relationship between general practitioners’ job satisfaction and burnout levels. Studies Ethno-Med. 2014;8(3):239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirwan M, Armstrong D. Investigation of burnout in a sample of British general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1995;45(394):259–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kotb AA, Mohamed KA, Kamel MH, et al. Comparison of burnout pattern between hospital physicians and family physicians working in Suez Canal University Hospitals. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:164. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.164.3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lamothe M, Boujut E, Zenasni F, Sultan S. To be or not to be empathic: the combined role of empathic concern and perspective taking in understanding burnout in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee FJ, Stewart M, Brown JB. Stress, burnout, and strategies for reducing them: what’s the situation among Canadian family physicians? Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(2):234–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lheureux F, Truchot D, Borteyrou X. Suicidal tendency, physical health problems and addictive behaviours among general practitioners: their relationship with burnout. Work Stress. 2016;30(2):173–192. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcelino G, Cerveira JM, Carvalho I, et al. Burnout levels among Portuguese family doctors: a nationwide survey. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3):e001050. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meier LL, Tschudi P, Meier CA, et al. When general practitioners don’t feel appreciated by their patients: prospective effects on well-being and work–family conflict in a Swiss longitudinal study. Fam Pract. 2015;32(2):181–186. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nørøxe KB, Pedersen AF, Bro F, Vedsted P. Mental well-being and job satisfaction among general practitioners: a nationwide cross-sectional survey in Denmark. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0809-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nørøxe KB, Pedersen AF, Carlsen AH, et al. Mental well-being, job satisfaction and self-rated workability in general practitioners and hospitalisations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions among listed patients: a cohort study combining survey data on GPs and register data on patients. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(12):997–1006. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-009039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Dea B, O’Connor P, Lydon S, Murphy AW. Prevalence of burnout among Irish general practitioners: a cross-sectional study. Ir J Med Sci. 2017;186(2):447–453. doi: 10.1007/s11845-016-1407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Orton P, Orton C, Pereira Gray D. Depersonalised doctors: a cross-sectional study of 564 doctors, 760 consultations and 1876 patient reports in UK general practice. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000274. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orton PK, Pereira Gray D. Factors influencing consultation length in general/family practice. Fam Pract. 2016;33(5):529–534. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozyurt A, Hayran O, Sur H. Predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish physicians. QJM. 2006;99(3):161–169. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pedersen AF, Andersen CM, Olesen F, Vedsted P. Risk of burnout in Danish GPs and exploration of factors associated with development of burnout: a two-wave panel study. Int J Family Med. 2013;2013:603713. doi: 10.1155/2013/603713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pedersen AF, Sørensen JK, Bruun NH, et al. Risky alcohol use in Danish physicians: associated with alexithymia and burnout? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pedersen AF, Ingeman ML, Vedsted P. Empathy, burn-out and the use of gut feeling: a cross-sectional survey of Danish general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e020007. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pedersen AF, Vedsted P. Understanding the inverse care law: a register and survey-based study of patient deprivation and burnout in general practice. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:121. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0121-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pedersen AF, Nørøxe KB, Vedsted P. Influence of patient multimorbidity on GP burnout: a survey and register-based study in Danish general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2020. DOI: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Picquendar G, Guedon A, Moulinet F, Schuers M. Influence of medical shortage on GP burnout: a cross-sectional study. Fam Pract. 2019;36(3):291–296. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmy080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pit SW, Hansen V. Factors influencing early retirement intentions in Australian rural general practitioners. Occup Med (Lond) 2014;64(4):297–304. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soler JK, Yaman H, Esteva M, et al. Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study. Fam Pract. 2008;25(4):245–265. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stoyanov D, Tilov B. Burn out syndrome in health care: strategies for complex diagnostic assessment. In: Stoyanov D, editor. New developments in clinical psychology research. Hauppauge, NY: Nova; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taycan O, Taycan SE, Celik C. Relationship of burnout with personality, alexithymia, and coping behaviors among physicians in a semiurban and rural area in Turkey. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2014;69(3):159–166. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2013.763758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thommasen HV, Lavanchy M, Connelly I, et al. Mental health, job satisfaction, and intention to relocate. Opinions of physicians in rural British Columbia. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:737–744. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Torppa MA, Kuikka L, Nevalainen M, Pitkälä KH. Emotionally exhausting factors in general practitioners’ work. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(3):178–183. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2015.1067514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Torres X, Ojeda B, Collado A, et al. Characterization of burnout among Spanish family physicians treating fibromyalgia patients: the EPIFFAC study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(3):386–396. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.03.190201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tosevski DL, Milovancevic MP, Pejuskovic B, et al. Burnout syndrome of general practitioners in post-war period. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15(4):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Truchot D. Career orientation and burnout in French general practitioners. Psychol Rep. 2008;103(3):875–881. doi: 10.2466/pr0.103.3.875-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Twellaar M, Winants Y, Houkes I. How healthy are Dutch general practitioners? Self-reported (mental) health among Dutch general practitioners. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14(1):4–9. doi: 10.1080/13814780701814911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Dierendonck D, Schaufeli WB, Sixma HJ. Burnout among general practitioners: a perspective from equity theory. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1994;13(1):86–100. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Olesen F. Open access to general practice was associated with burnout among general practitioners. Int J Family Med. 2013;2013:383602. doi: 10.1155/2013/383602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Verweij H, Waumans RC, Smeijers D, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for GPs: results of a controlled mixed methods pilot study in Dutch primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(643):e99–e105. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X683497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Winefield H, Farmer E, Denson L. Work stress management for women general practitioners: an evaluation. Psychol Health Med. 1998;3(2):163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Winefield HR, Veale BM. Work stress and quality of work performance in Australian general practitioners. Aust J Prim Health. 2002;8(2):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Winefield HR, Anstey TJ. Job stress in general practice: practitioner age, sex and attitudes as predictors. Fam Pract. 1991;8(2):140–144. doi: 10.1093/fampra/8.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yaman H, Soler JK. The job related burnout questionnaire. A multinational pilot study. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31(11):1055–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yigit AO, Ay FA. The effect of emotional labor and impression management on burnout: example of Family Physicians. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(3):793–796. doi: 10.12669/pjms.35.3.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yuguero O, Marsal JR, Esquerda M, et al. Cross-sectional study of the association between empathy and burnout and drug prescribing quality in primary care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2019;20:e145. doi: 10.1017/S1463423619000793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zantinge EM, Verhaak PF, de Bakker DH, et al. Does the attention general practitioners pay to their patients’ mental health problems add to their workload? A cross sectional national survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zantinge EM, Verhaak PF, de Bakker DH, et al. Does burnout among doctors affect their involvement in patients’ mental health problems? A study of videotaped consultations. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sedgwick P, Marston L. How to read a funnel plot in a meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h4718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sabitova A, McGranahan R, Altamore F, et al. Indicators associated with job morale among physicians and dentists in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(1):31913202. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Herbert CP. Perspectives in primary care: values-based leadership is essential in health care. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):512–513. doi: 10.1370/afm.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abdelhafiz AS, Ali A, Ziady HH, et al. Prevalence, associated factors, and consequences of burnout among Egyptian physicians during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020;8:590190. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.590190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Trivedi N, Trivedi V, Moorthy A, Trivedi H. Recovery, restoration, and risk: a cross-sectional survey of the impact of COVID-19 on GPs in the first UK city to lock down. BJGP Open. 2021. DOI: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Di Monte C, Monaco S, Mariani R, Di Trani M. From resilience to burnout: psychological features of Italian general practitioners during COVID-19 emergency. Front Psychol. 2020;11:567201. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]