Abstract

Background

Antiplatelet agents are widely used to prevent cardiovascular events. The risks and benefits of antiplatelet agents may be different in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) for whom occlusive atherosclerotic events are less prevalent, and bleeding hazards might be increased. This is an update of a review first published in 2013.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of antiplatelet agents in people with any form of CKD, including those with CKD not receiving renal replacement therapy, patients receiving any form of dialysis, and kidney transplant recipients.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 13 July 2021 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We selected randomised controlled trials of any antiplatelet agents versus placebo or no treatment, or direct head‐to‐head antiplatelet agent studies in people with CKD. Studies were included if they enrolled participants with CKD, or included people in broader at‐risk populations in which data for subgroups with CKD could be disaggregated.

Data collection and analysis

Four authors independently extracted data from primary study reports and any available supplementary information for study population, interventions, outcomes, and risks of bias. Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated from numbers of events and numbers of participants at risk which were extracted from each included study. The reported RRs were extracted where crude event rates were not provided. Data were pooled using the random‐effects model. Confidence in the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

We included 113 studies, enrolling 51,959 participants; 90 studies (40,597 CKD participants) compared an antiplatelet agent with placebo or no treatment, and 29 studies (11,805 CKD participants) directly compared one antiplatelet agent with another. Fifty‐six new studies were added to this 2021 update. Seven studies originally excluded from the 2013 review were included, although they had a follow‐up lower than two months.

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment were at low risk of bias in 16 and 22 studies, respectively. Sixty‐four studies reported low‐risk methods for blinding of participants and investigators; outcome assessment was blinded in 41 studies. Forty‐one studies were at low risk of attrition bias, 50 studies were at low risk of selective reporting bias, and 57 studies were at low risk of other potential sources of bias.

Compared to placebo or no treatment, antiplatelet agents probably reduces myocardial infarction (18 studies, 15,289 participants: RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.99, I² = 0%; moderate certainty). Antiplatelet agents has uncertain effects on fatal or nonfatal stroke (12 studies, 10.382 participants: RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.59, I² = 37%; very low certainty) and may have little or no effect on death from any cause (35 studies, 18,241 participants: RR 0.94, 95 % CI 0.84 to 1.06, I² = 14%; low certainty). Antiplatelet therapy probably increases major bleeding in people with CKD and those treated with haemodialysis (HD) (29 studies, 16,194 participants: RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.65, I² = 12%; moderate certainty). In addition, antiplatelet therapy may increase minor bleeding in people with CKD and those treated with HD (21 studies, 13,218 participants: RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.90, I² = 58%; low certainty). Antiplatelet treatment may reduce early dialysis vascular access thrombosis (8 studies, 1525 participants) RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.70; low certainty). Antiplatelet agents may reduce doubling of serum creatinine in CKD (3 studies, 217 participants: RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.86, I² = 8%; low certainty). The treatment effects of antiplatelet agents on stroke, cardiovascular death, kidney failure, kidney transplant graft loss, transplant rejection, creatinine clearance, proteinuria, dialysis access failure, loss of primary unassisted patency, failure to attain suitability for dialysis, need of intervention and cardiovascular hospitalisation were uncertain. Limited data were available for direct head‐to‐head comparisons of antiplatelet drugs, including prasugrel, ticagrelor, different doses of clopidogrel, abciximab, defibrotide, sarpogrelate and beraprost.

Authors' conclusions

Antiplatelet agents probably reduced myocardial infarction and increased major bleeding, but do not appear to reduce all‐cause and cardiovascular death among people with CKD and those treated with dialysis. The treatment effects of antiplatelet agents compared with each other are uncertain.

Plain language summary

Are anti‐blood clotting drugs beneficial for people with chronic kidney disease?

What is the issue? People with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have an increased risk of heart disease that can block the blood supply to the heart or brain causing a heart attack or stroke. Drugs that prevent blood clots from forming (antiplatelet agents) can prevent deaths caused by clots in arteries in the general adult population. However, there may be fewer benefits for people who have CKD, because blood clots in arteries is a less common cause of death or reason to be admitted to hospital compared with heart failure or sudden death in these people. People with CKD also have an increased tendency for bleeding due to changes in how the blood clots. Antiplatelet agents may therefore be more hazardous when CKD is present.

What did we do?

This updated review evaluated the benefits and harms of antiplatelet agents to prevent cardiovascular disease and death, and the impact on dialysis vascular access (fistula or graft) function in people who have CKD. We identified 90 studies comparing antiplatelet agents with placebo or no treatment and 29 studies directly comparing one antiplatelet agent with another.

What did we find? Antiplatelet agents probably prevent heart attacks, but do not clearly reduce death or stroke. Treatment with these agents may increase the risk of major and minor bleeding. Clotting of dialysis access was prevented with antiplatelet agents.

Conclusions The benefits of antiplatelet agents for people with CKD is probably limited to the prevention of a heart attack. The treatment does not appear to prevent stroke or death and probably incurs excess serious bleeding that may require hospital admission or transfusion.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Antiplatelet agents versus control for chronic kidney disease.

| Antiplatelet agents versus control for chronic kidney disease | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with chronic kidney disease (predialysis (GFR 15 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m²), HD, PD, transplant recipients) Settings: all settings involving people with any stage of CKD Intervention: antiplatelet agents (abciximab, aspirin, beraprost sodium, cilostazol, clopidogrel, dypiridamole, eptidifibatide, pentoxifylline, picotamide, prasugrel, prostacyclin, sarpogrelate, sulphinpyrazone, ticlopidine, tirofiban, alone or in combination) Comparison: placebo or no treatment | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (RCTs) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with control | Risk with antiplatelet agents | ||||

|

Fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction Follow‐up: 3 to 61.2 months (median 12 months) |

All patients (predialysis, dialysis, transplant recipients) | RR 0.88 (0.79 to 0.99) | 15,289 (18) |

moderate 1 ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

|

| 70 per 1,000 | 8 fewer per 1,000 (1 to 15 fewer) | ||||

| CKD patients (GFR 15 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) | RR 0.85 (0.74 to 0.99) | 11,912 (11) |

moderate 1 ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

||

| 85 per 1,000 | 13 fewer per 1,000 (1 to 22 fewer) | ||||

| HD patients | RR 0.83 (0.49 to 1.41) | 2929 (6) |

moderate 1 ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

||

| 20 per 1,000 | 3 fewer per 1,000 (10 fewer to 8 more) | ||||

|

Fatal or nonfatal stroke Follow‐up: 3 to 61.2 months (median 12 months) |

All patients (predialysis, dialysis, transplant recipients) | RR 1.01 (0.64 to 1.59) | 10,382 (12) |

very low 1,2,3 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

|

| 20 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (7 fewer to 12 more) | ||||

| CKD patients (GFR 15 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) | RR 1.06 (0.64 to 1.74) | 7062 (5) |

very low 1,2,3 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

||

| 25 per 1,000 | 2 more per 1,000 (9 fewer to 19 more) | ||||

| HD patients | RR 0.62 (0.15 to 2.60) | 2872 (6) |

very low 1,2,3 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

||

| 10 per 1,000 | 4 fewer per 1,000 (8 fewer to 16 more) | ||||

|

Death (any cause) Follow‐up: 0.9 to 88.2 months (median 12 months) |

All patients (predialysis, dialysis, transplant recipients) | RR 0.94 (0.84 to 1.06) | 18,241 (35) |

low 1,2 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

|

| 74 per 1,000 | 4 fewer per 1,000 (12 fewer to 4 more) | ||||

| CKD patients (GFR 15 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) | RR 0.97 (0.81 to 1.16) | 13,234 (19) |

low 1,2 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

||

| 72 per 1,000 | 2 fewer per 1,000 (14 fewer to 12 more) | ||||

| HD patients | RR 0.86 (0.72 to 1.03) | 4523 (14) |

low 1,2 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

||

| 87 per 1,000 | 12 fewer per 1,000 (24 fewer to 3 more) | ||||

|

Cardiovascular death Follow‐up: 0.9 to 88.2 months (median 12 months) |

All patients (predialysis, dialysis, transplant recipients) | RR 0.87 (0.65 to 1.15) | 9606 (21) |

very low 1,2,3 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

|

| 36 per 1,000 | 5 fewer per 1,000 (13 fewer to 5 more) | ||||

| CKD patients (GFR 15 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) | RR 0.98 (0.60 to 1.59) | 6525 (10) |

very low 1,2,3 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

||

| 37 per 1,000 | 1 fewer per 1,000 (15 fewer to 22 more) | ||||

| HD patients | RR 0.71 (0.47 to 1.09) | 2597 (9) |

very low 1,2,3 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

||

| 38 per 1,000 | 11 fewer per 1,000 (20 fewer to 3 more) | ||||

|

Major bleeding Follow‐up: 0.7 to 61.2 months (median 6 months) |

All patients (predialysis, dialysis, transplant recipients) | RR 1.35 (1.10 to 1.65) | 16,194 (29) |

moderate 1 ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

|

| 29 per 1,000 | 10 more per 1,000 (3 to 19 more) | ||||

| CKD patients (GFR 15 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) | RR 1.51 (1.15 to 1.98) | 11591 (12) |

moderate 1 ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

||

| 35 per 1,000 | 18 more per 1,000 (5 to 34 more) | ||||

| HD patients | RR 0.90 (0.53 to 1.55) | 4119 (15) |

moderate 1 ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

||

| 13 per 1,000 | 1 fewer per 1,000 (6 fewer to 7 more) | ||||

|

Minor bleeding Follow‐up: 0.5 to 84 months (median 6 months) |

All patients (predialysis, dialysis, transplant recipients) | RR 1.55 (1.27 to 1.90) | 13,218 (21) |

low 1,3 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

|

| 92 per 1,000 | 51 more per 1,000 (25 to 83 more) | ||||

| CKD patients (GFR 15 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) | RR 1.48 (1.20 to 1.83) | 11,530 (12) |

low 1,3 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

||

| 103 per 1,000 | 50 more per 1,000 (21 to 86 more) | ||||

| HD patients | RR 1.87 (0.65 to 5.40) | 1240 (8) |

low 1,3 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

||

| 8 per 1,000 | 7 per 1,000 (3 fewer to 35 more) | ||||

|

Early access thrombosis (before 8 weeks) Follow‐up: 0.9 to 12 months (median 1.4 months) |

HD patients | RR 0.52 (0.38 to 0.70) | 1525 (8) |

low 1,4 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

|

| 200 per 1,000 | 6 fewer per 1,000 (60 to 124 fewer) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; CKD: chronic kidney disease; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; HD: haemodialysis; OIS: Optimal Information Size | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Some or all studies were not blinded (participants and/or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision

3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to moderate between‐study heterogeneity

4 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision (OIS criteria)

Background

Description of the condition

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and death among people at all stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Casas 2005; Keith 2004; Mann 2001; Norris 2006; Sarnak 2003; Weiner 2004a; Weiner 2004b) including kidney transplant recipients (Aakhus 1999; ANZDATA 2019; Kasiske 2000; Ojo 2000; USRDS 2010). Compared with the general population, the risk of cardiovascular disease is increased two‐fold in people with the early stages of CKD (Go 2004) and 30‐ to 50‐fold in people who need dialysis (de Jager 2009; Fort 2005) in whom it accounts for half of all deaths (Collins 2003). Population representative surveys in Australia (AusDiab 2003) and the USA (NHANES 2010) have shown that CKD (defined as proteinuria or reduction of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) below 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) affects approximately 16% of the adult population. With the increasing prevalence of some of the known risk factors for CKD, including hypertension, obesity and diabetes (Fields 2004; Koren‐Morag 2006; Mokdad 2003), the burden of CKD and its complications are projected to increase and to contribute significantly to global healthcare expenditure.

Description of the intervention

Excessive platelet activation occurs in CKD, even in the early stages of the disease. Specifically, the expression of P‐selectin, glycoprotein 53 and activated fibrinogen receptor‐1 on the platelet surface membrane is significantly increased in CKD patients. In ESRD, these abnormalities are more pronounced and may lead to access site thrombosis. Platelet activation is heavily implicated in the prothrombotic state observed in CKD patients, and oral antiplatelet agents have been extensively used in these patients (Alexopoulos 2011).

Dipyridamole is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that reversibly inhibits platelet activation and aggregation by increasing adenosine levels and inhibiting cAMP‐phosphodiesterase (Hung 2014).

The antithrombotic action of aspirin is due to inhibition of platelet function by acetylation of the platelet cyclooxygenase (COX) at the functionally important amino acid serine529. This prevents the access of the arachidonic acid to the catalytic site of the enzyme at tyrosine385 and results in irreversible inhibition of platelet‐dependent thromboxane formation (Schror 1997).

P2Y12 is a G‐protein–coupled receptor that elicits specific intracellular responses to ADP resulting in the activation of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor. Active metabolites of thienopyridines (ticlopidine and clopidogrel) irreversibly bind to the ADP binding site and thereby prevent intracellular signalling and ADP‐induced platelet aggregation. P2Y12 antagonists, such as ticagrelor and prasugrel, inhibit adenosine reuptake in erythrocytes and other cells. The latter effect has been attributed to improved platelet inhibition and coronary blood flow and reduced infarct size (Gurbel 2019). Cilostazol, a selective reversible phosphodiesterase type III inhibitor, has antiplatelet effects due to subsequent increases in cyclic adenosine monophosphate within platelets. The potential to achieve platelet inhibition with minimal risk of bleeding might be explained by an endothelium‐targeted antithrombotic therapy, that is, reduction of partially activated platelets by improved endothelial function (Woo 2011).

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (abciximab, eptifibatide and tirofiban) administered parenterally interfere with platelet activity at the final common pathway of platelet‐induced thrombosis, showing a much greater antiplatelet activity than aspirin with or without clopidogrel at normal doses. In addition to preventing platelet aggregation, GP IIb/IIIa antagonism has the ability to induce the dissolution of platelet‐rich clots by disrupting fibrinogen platelet interaction (Stangal 2010).

Sulfinpyrazone appears to interfere with the adhesion of platelets to subendothelial structures and atherosclerotic plaques (Oelz 1979).

How the intervention might work

Antiplatelet agents prevent arterial occlusion from thrombus via direct prevention of platelet aggregation. Currently available data suggest antiplatelet agents might be beneficial in patients with CKD for primary (ATT 2002; HOT 1993; Ruilope 2001) and secondary (Berger 2003; McCullough 2002) prevention of cardiovascular events. Antiplatelet agents may have beneficial effects on the kidney, possibly reducing proteinuria and protecting kidney function in people with glomerulonephritis (Taji 2006; Zäuner 1994), and improving graft function in kidney transplant recipients (Bonomini 1986; Frascà 1986). However, some have reported that the efficacy of antiplatelet agents in CKD might be lower than for other high cardiovascular risk populations (Best 2008). Despite this, the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guideline program (KDOQI) has supported the use of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in CKD. Antiplatelet agents appear to have a modest effect on the preservation of arteriovenous fistula patency (Dember 2005). Their use for fistula preservation and as part of a multifactorial intervention strategy for patients with CKD is advocated by guideline groups (CARI 2000; UK Renal Association 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

The previous meta‐analyses did not clearly assess the benefits and harms of antiplatelet agents in people with CKD, including those undergoing dialysis (haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD)) and transplant recipients, and recently new studies have been performed in this area in contrast to the general population, people with CKD have a different profile of causes for major cardiovascular events, including a greater preponderance for arrhythmia and congestive heart failure (Amann 2003; Curtis 2005; Dikow 2005; Foley 1995; Remppis 2008), altered pharmacokinetics (Mosenkis 2004; Scheen 2008) and impaired haemostasis (Kaw 2006; Remuzzi 1988; Wattanakit 2008; Zwaginga 1991). Compared with people who do not have CKD, these factors might expose the CKD population to a different spectrum of risk and benefit from antiplatelet agents.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of antiplatelet agents in people with any form of CKD, including those with CKD not receiving kidney replacement therapy, patients receiving any form of dialysis, and kidney transplant recipients.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) of antiplatelet agents in people with CKD were included.

Types of participants

Participants with CKD, including those who needed kidney replacement therapy (dialysis), had a functioning kidney transplant, or whose kidney function was impaired (defined as a reduced GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m²), the presence of other markers of kidney damage such as proteinuria (KDOQI stages 1 to 5), or an elevated serum creatinine (SCr) level (SCr >120 μmol/L). Data from subgroups of participants with CKD within studies with broader inclusion criteria (e.g. people from the general population, people with diabetes, people with cardiovascular disease) were also included.

Types of interventions

Interventions included any antiplatelet agent. Agents could be administered at any dose or route of administration and compared with placebo, no treatment, different dose of the same or different antiplatelet agents, different administration regimens of the same or a different antiplatelet agent, or different combinations of antiplatelet agents. Antiplatelet agents included, but were not limited to:

Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin)

Adenosine reuptake inhibitors (dipyridamole)

Adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitors (ticlopidine and clopidogrel)

Phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitors (cilostazol)

P2Y₁₂ antagonists (prasugrel, ticagrelor, cangrelor, elinogrel)

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (abciximab, eptifibatide, tirofiban, defibrotide)

Sulphinpyrazone.

We excluded studies comparing antiplatelet agents to anticoagulants.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Myocardial infarction (MI) (nonfatal or fatal)

Stroke (nonfatal or fatal)

Death (any cause)

Cardiovascular death

Bleeding‐related death

Major bleeding

Minor bleeding

Haemorrhagic stroke

Kidney failure (previously referred to as end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD))

Kidney transplant graft loss

Transplant rejection

Dialysis vascular outcomes (failure, early thrombosis, loss of unassisted patency, failure to attain suitability for dialysis, and need for access intervention)

Hospitalisation

Treatment withdrawal.

Secondary outcomes

SCr

Proteinuria.

Search methods for identification of studies

A systematic and comprehensive literature search was carried out to identify eligible RCTs. There was no language restriction.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 13 July 2021 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources:

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Searches of kidney and transplant journals, and the proceedings and abstracts from major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Contacting relevant individuals/organisations seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies.

Grey literature sources (e.g. abstracts, dissertations and theses), in addition to those already included in the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies, were searched.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All RCTs enrolling participants with CKD were considered as well as studies in broader populations in which outcome data for subgroups with CKD could be disaggregated. Based on the search strategy described, we identified titles and abstracts that were potentially relevant to this systematic review. Four independent authors screened the titles and abstracts and selected those that met the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies in selection were resolved by discussion or by the review of an experienced arbitrator. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment.

Data extraction and management

Four authors independently read the full text of extracted articles and included studies that met the inclusion criteria. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses.

The same independent authors used standardised data forms to extract data on:

Study design

Participants: baseline characteristics including age, sex, race, diabetic status (proportion with diabetes), hypertension status (proportion with hypertension), smoking status (proportion of smokers), visceral obesity (proportion with visceral obesity as defined by authors), previous cardiovascular events (proportion with existing cardiovascular disease), and stage of CKD (dialysis, predialysis, transplant)

Interventions and comparisons: antiplatelet agent, dose and route of administration, duration of treatment

Outcomes: as listed in Types of outcome measures.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were assessed independently by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2020) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. such as death, cardiovascular events), results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. creatinine clearance (CrCl), GFR, SCr, proteinuria), the mean difference (MD) and its 95% CI was used. The final results are presented in International System (SI) units. When crude event data were not reported by investigators, available reported risk estimates and their 95% CIs were included in meta‐analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was each participant recruited into the studies.

For cross‐over studies, we looked for reporting of paired data in order to estimate within‐user differences. Where no such data were provided, we used data from the first period only in the absence of washout periods to avoid the carry‐over effect.

For studies with more than two arms, we treated each pair of arms as a separate pairwise comparison.

Dealing with missing data

Where possible, data for each outcome of interest were evaluated, regardless of whether the analysis was based on intention‐to‐treat. In particular, dropout rates were investigated and reported in detail, including dropout due to discontinuation of study drug, treatment failure, death, withdrawal of consent, or loss to follow‐up. Corresponding authors of all large studies with broader inclusion were contacted to obtain data for the subgroup of CKD (Higgins 2020).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We then quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I² values was as follows:

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I² depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi² test, or a confidence interval for I²) (Higgins 2020).

Assessment of reporting biases

We evaluated asymmetries in the inverted funnel plots (i.e. for systematic differences in the effect sizes between more precise and less precise studies). There are many potential explanations for why an inverted funnel plot may be asymmetric, including chance, heterogeneity, publication and reporting bias (Higgins 2020). Insufficient data were available to evaluate the robustness of the results according to publication, namely, publication as a full manuscript in a peer‐reviewed journal versus studies published as abstracts/text/letters/editorials and publication.

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model. The GRADE approach developed by Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE Working Group) was used for evaluating the quality of evidence for outcomes to be reported. Based on the GRADE approach, the quality of a body of evidence, in terms of the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the quantity of specific interest, was defined.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was explored using subgroup analyses according to the following parameters (where sufficient numbers of studies were available):

-

Population characteristics

Stage of CKD (pre‐dialysis, dialysis, transplant)

Presence or absence of comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking, obesity, family history of cardiovascular disease, baseline cardiovascular disease); percentage of patients with these comorbidities in each study

Age

Sex

Mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) (< 140 mm Hg versus ≥ 140 mm Hg)

Ethnicity (proportion white)

Presence or absence of previous cardiovascular events (e.g. primary versus secondary prevention)

Time on dialysis (< 3 years versus ≥ 3 years) and modalities of dialysis (HD versus PD)

Time with a functioning transplant (< 3 years versus ≥ 3 years)

-

Intervention characteristics

Types, doses and route of administration of the antiplatelet agents

Duration of intervention (< 6 months, 6 to 12 months, > 12 months).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken to explore the robustness of findings to key decisions in the review process. We assessed the risks of death (any cause and cardiovascular death), nonfatal and fatal MI, and major bleeding only including studies with adequate allocation concealment, or at low risk of bias due to completeness of follow‐up. Insufficient data were available to perform indirect comparisons of antiplatelet agent versus antiplatelet agent (Song 2003).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2020a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also includes an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011a). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as to the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, the precision of effect estimates, and the risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2020b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables:

MI (fatal or nonfatal)

Stroke (fatal or nonfatal)

Death (any cause)

Cardiovascular death

Major bleeding

Minor bleeding

Early access thrombosis

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

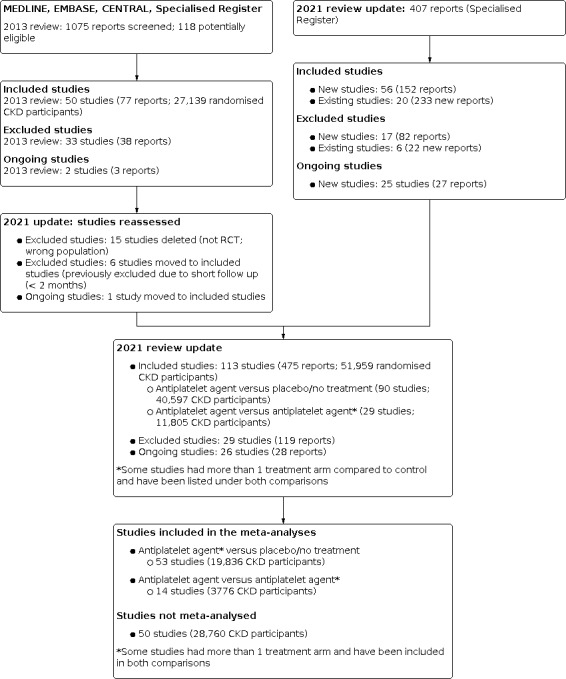

Search results are shown in Figure 1. For this 2021 review update, we screened 407 titles and abstracts identified by the updated search. After full‐text assessment 98 new studies were identified. Fifty‐six new studies (152 reports) were included, 17 (82 reports) were excluded, and 25 ongoing studies were identified. We also identified 233 new reports of 20 existing included studies and 22 new reports of six excluded studies.

1.

Study flow diagram; study identification and selection process.

We reclassified six previously excluded studies as included studies (Dmoszynska‐Giannopoulou 1990; Kamper 1997; Movchan 2001; RESIST 2008; Rubin 1982; Salter 1984), and one ongoing study has now been included (FAVOURED 2009).

For this 2011 update, 113 studies (475 reports, 51,959 CKD participants, Figure 1) were included, 29 studies were excluded, and there are 26 ongoing studies.

Included studies

The overall characteristics of the included studies are provided in the Characteristics of included studies. Information for three studies (1238 participants: Creek 1990; Ell 1982; Middleton 1992) including two internal study reports (Creek 1990; Middleton 1992) were only available in a previously published meta‐analysis of antiplatelet agents (ATT 2002). For three studies (103 participants), the most complete data were provided in published conference proceedings (Dodd 1980; Gonzalez 1995; Taber 1992), and for one study (NCT01252056), information about study characteristics and endpoint data was extracted from www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Studies compared antiplatelet agents with placebo or no treatment, or another antiplatelet agent; several studies compared two or more antiplatelet agents.

Ninety studies (40,597 CKD participants) compared an antiplatelet agent to placebo or no treatment (AASER 2017; Abacilar 2015; Abdul‐Rahman 2007; Anderson 1974; Andrassy 1974; ATACAS 2008; CASSIOPEIR 2014; Chan 1987; CHANCE 2013; CHARISMA 2006; Cheng 1998a; Christopher 1987; CREDO 2005; Creek 1990; CURE 2000; Dember 2005; Dixon 2005; Dmoszynska‐Giannopoulou 1990; Dodd 1980; Donadio 1984; EARLY ACS 2005; Ell 1982; EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; EPISTENT 1998; ETDRS 1992; FAVOURED 2009; Fiskerstrand 1985; Frascà 1997; Gaede 2003; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Giustina 1998; GLOBAL LEADERS 2018; Goicoechea 2012; Gonzalez 1995; Gröntoft 1985; Gröntoft 1998; Guo 1998; Hansen 2000; Harter 1979; HOT 1993; IMPACT II 1997; Jiao 2013; JPAD 2008; Kaegi 1974; Kamper 1997; Kaufman 2003; Khajehdehi 2002; Kobayashi 1980; Kontessis 1993; Kooistra 1994; Koyama 1990; Michie 1977; Middleton 1992; Milutinovic 1993; Movchan 2001; Mozafar 2013; Mozafar 2018; Nakamura 2001d; Nakamura 2002b; NCT01252056; Nyberg 1984; PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014; Pierucci 1989; PLATO 2009; PREDIAN 2011; PRISM‐PLUS 1998; PURSUIT 1997; Quarto Di Palo 1991; RAPPORT 1998; Reams 1985; RESIST 2008; Rouzrokh 2010; Rubin 1982; Salter 1984; Schulze 1990; Sreedhara 1994; Steiness 2018; STOP 1995; Storck 1996; Taber 1992; Tang 2014; Tayebi 2018; TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009; TRACER 2013; UK‐HARP‐I 2005; Watanabe 2011b; Weseley 1982; Yuto 2012; Zäuner 1994)

Twenty‐nine studies (11,805 CKD participants) compared an antiplatelet agent to a second antiplatelet agent (Alexopoulos 2011; CASSIOPEIR 2014; CILON‐T 2010; Dash 2013; EUCLID 2017; Frascà 1986; Hidaka 2013; J‐PADD 2014; Kauffmann 1980; Khajehdehi 2002; Liang 2015; Movchan 2001; Ogawa 2008; OPT‐CKD 2018; Ota 1996; PIANO‐2 CKD 2011; PIANO‐3 2015; PIANO‐6 2017; PLATO 2009; RESIST 2008; Schnepp 2000; Sreedhara 1994; Taber 1992; TARGET 2000; Teng 2018; TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006; Waseda 2016; Xydakis 2004; Yang 2016b).

Antiplatelet versus placebo or no treatment studies

Ninety studies comparing an antiplatelet to placebo or no treatment were published between 1974 and 2018. The number of CKD participants ranged from 6 to 4983 participants (median 85 participants) and the mean age of the participants ranged from 29 to 73.4 years. The duration of study follow‐up ranged from 48 hours to 88.2 months (median six months).

Forty‐nine studies were conducted in people with CKD not yet requiring dialysis (37,013 participants: AASER 2017; ATACAS 2008; CASSIOPEIR 2014; Chan 1987; CHANCE 2013; CHARISMA 2006; Cheng 1998a; Christopher 1987; CREDO 2005; CURE 2000; Donadio 1984; EARLY ACS 2005; EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; EPISTENT 1998; ETDRS 1992; Frascà 1997; Gaede 2003; Giustina 1998; GLOBAL LEADERS 2018; Goicoechea 2012; Gonzalez 1995; Guo 1998; Hansen 2000; HOT 1993; IMPACT II 1997; Jiao 2013; JPAD 2008; Khajehdehi 2002; Kontessis 1993; Koyama 1990; Movchan 2001; Nakamura 2001d; NCT01252056; Nyberg 1984; PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014; Pierucci 1989; PREDIAN 2011; PRISM‐PLUS 1998; PURSUIT 1997; RAPPORT 1998; RESIST 2008; Steiness 2018 Tang 2014; TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009; TRACER 2013; Watanabe 2011b; Zäuner 1994).

Thirty‐two studies enrolled HD patients (5097 participants: Abacilar 2015; Abdul‐Rahman 2007; Andrassy 1974; Creek 1990; Dember 2005; Dixon 2005; Dmoszynska‐Giannopoulou 1990; Dodd 1980; Ell 1982; Fiskerstrand 1985; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Gröntoft 1985; Harter 1979; Kaegi 1974; Kamper 1997; Kaufman 2003; Kobayashi 1980; Kooistra 1994; Michie 1977; Middleton 1992; Milutinovic 1993; Mozafar 2013; Mozafar 2018; Nakamura 2002b; Rouzrokh 2010; Salter 1984; Sreedhara 1994; STOP 1995; Taber 1992; Tayebi 2018; Yuto 2012).

Three studies were in patients treated with PD (40 participants: Reams 1985; Rubin 1982; Weseley 1982).

Four studies enrolled kidney transplant recipients (141 participants: Anderson 1974; Quarto Di Palo 1991; Schulze 1990; Storck 1996).

Two studies enrolled participants with earlier stages of CKD and those treated with HD (673 participants: FAVOURED 2009; Gröntoft 1998)

In one study (UK‐HARP‐I 2005; 448 participants), participants included those with earlier stages of CKD, transplant recipients and participants treated with dialysis (both HD and PD).

In the 90 studies that compared an antiplatelet agent with placebo or no treatment, the interventions included:

-

Acetylsalicylic acid

Aspirin (16 studies, 6140 participants: AASER 2017; Abdul‐Rahman 2007; Andrassy 1974; ATACAS 2008; ETDRS 1992; FAVOURED 2009; Gaede 2003; Guo 1998; Hansen 2000; Harter 1979; HOT 1993; JPAD 2008; Kooistra 1994; Mozafar 2013; Storck 1996; UK‐HARP‐I 2005)

Aspirin plus dextran (1 study, 45 participants; Taber 1992)

-

Adenosine reuptake inhibitors

Dilazep dihydrochloride (2 studies, 62 participants: Nakamura 2001d; Nakamura 2002b)

Dipyridamole (7 studies, 615 participants: Anderson 1974; Koyama 1990; Movchan 2001; Reams 1985; Rubin 1982; Schulze 1990; Weseley 1982)

Dipyridamole plus aspirin (11 studies, 2004 participants: Chan 1987; Christopher 1987; Dixon 2005; Donadio 1984; Gonzalez 1995; Khajehdehi 2002; Middleton 1992; Salter 1984; Sreedhara 1994; Tayebi 2018; Zäuner 1994)

Dypiridamole or aspirin (1 study, 501 participants: Rouzrokh 2010)

-

Adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitors

Clopidogrel (7 studies, 7931 participants: CHANCE 2013; CHARISMA 2006; CREDO 2005; CURE 2000; Dember 2005; Ghorbani 2009; Mozafar 2018)

Clopidogrel and aspirin (1 study, 200 participants: Kaufman 2003)

Clopidogrel and prostacyclin (1 study, 96 participants: Abacilar 2015)

Ticlopidine (12 studies, 986 participants: Cheng 1998a; Creek 1990; Dodd 1980; Ell 1982; Fiskerstrand 1985; Ghorbani 2013; Gröntoft 1985; Gröntoft 1998; Kamper 1997; Kobayashi 1980; Milutinovic 1993; Nyberg 1984)

-

Haemorrhagic agents

Pentoxifylline (2 studies, 260 participants: Goicoechea 2012; PREDIAN 2011)

-

PAR‐1 antagonist

Vorapaxar (1 study, 4983 participants: TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009)

-

Phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitors

Cilostazol (3 studies, 483 participants: Jiao 2013; NCT01252056; Tang 2014)

Beraprost sodium (1 study, 892 participants: CASSIOPEIR 2014)

-

P2Y₁₂ antagonists

Ticagrelor (1 study, 4849 participants: PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014)

Ticagrelor plus aspirin then ticagrelor alone (1 study, 838 participants: GLOBAL LEADERS 2018)

-

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

Abciximab (5 studies, 1537 participants: EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; EPISTENT 1998; RAPPORT 1998; RESIST 2008)

Tirofiban (1 study, 611 participants: PRISM‐PLUS 1998)

Eptifibatide (3 studies, 5065 participants: EARLY ACS 2005; IMPACT II 1997; PURSUIT 1997)

-

Other

Defibrotide (1 study, 20 participants: Frascà 1997)

Picotamide (3 studies, 901 participants: Giustina 1998; Quarto Di Palo 1991; STOP 1995)

Sarpogrelate (2 studies, 132 participants: Watanabe 2011b; Yuto 2012)

Sulphinpyrazone (3 studies, 108 participants: Dmoszynska‐Giannopoulou 1990; Kaegi 1974; Michie 1977)

Sulphonamide derivative (1 study, 6 participants: Pierucci 1989)

Thromboxane synthetase inhibitor (1 study, 15 participants: Kontessis 1993)

SER150 (novel anti‐thromboxane) (1 study, 72 participants: Steiness 2018)

Vorapaxar (1 study, 1477 participants: TRACER 2013)

Vascular access studies

We identified 31 studies that reported dialysis vascular access endpoints in 6449 participants (Abacilar 2015; Abdul‐Rahman 2007; Anderson 1974; Andrassy 1974; Creek 1990; Dember 2005; Dixon 2005; Dodd 1980; Ell 1982; FAVOURED 2009; Fiskerstrand 1985; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Gröntoft 1985; Gröntoft 1998; Harter 1979; Kaegi 1974; Kaufman 2003; Kobayashi 1980; Kooistra 1994; Michie 1977; Middleton 1992; Milutinovic 1993; Mozafar 2013; Mozafar 2018; Rouzrokh 2010; Sreedhara 1994; STOP 1995; Taber 1992; Tayebi 2018; Yuto 2012). Generally, these studies were small; only five studies included more than 500 participants (Dember 2005; Dixon 2005; Middleton 1992; Rouzrokh 2010; STOP 1995), and sixteen studies enrolled fewer than 100 participants (Abacilar 2015; Abdul‐Rahman 2007; Anderson 1974; Andrassy 1974; Ell 1982; Fiskerstrand 1985; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Gröntoft 1985; Harter 1979; Kaegi 1974; Michie 1977; Milutinovic 1993; Taber 1992; Tayebi 2018 Yuto 2012).

Ticlopidine was most the commonly administered (9 studies, 884 participants: Creek 1990; Dodd 1980; Ell 1982; Fiskerstrand 1985; Ghorbani 2013; Gröntoft 1985; Gröntoft 1998; Kobayashi 1980; Milutinovic 1993), followed by aspirin (6 studies, 917 participants: Abdul‐Rahman 2007; Andrassy 1974; FAVOURED 2009; Harter 1979; Kooistra 1994; Mozafar 2013). The combination of dipyridamole and aspirin was prescribed to 1720 participants in four studies (Dixon 2005; Middleton 1992; Sreedhara 1994; Tayebi 2018), three studies evaluated clopidogrel (1070 participants: Dember 2005; Ghorbani 2009; Mozafar 2018), two studies evaluated sulphinpyrazone (78 participants: Kaegi 1974; Michie 1977), and single studies assessed dipyridamole (27 participants: Anderson 1974), picotamide (832 participants: STOP 1995) and sarpogrelate (79 participants: Yuto 2012). One study each assessed the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin (200 participants: Kaufman 2003), the combination of dextran and aspirin (45 participants: Taber 1992), the combination of clopidogrel and prostacyclin (96 participants: Abacilar 2015), and the combination of aspirin or dipyridamole (501 participants: Rouzrokh 2010). The duration of the intervention varied from one month to 61,2 months, with a median of five months.

Studies evaluated whether treatment maintained patency of an arteriovenous fistula (10 studies, 1765 participants: Abacilar 2015; Andrassy 1974; Dember 2005; Fiskerstrand 1985; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Gröntoft 1985; Gröntoft 1998; Kooistra 1994; Yuto 2012), shunt or graft (5 studies, 1063 participants: Dixon 2005; Harter 1979; Kaegi 1974; Kaufman 2003; Sreedhara 1994), fistula or graft (1 study, 16 participants: Michie 1977), or central venous catheter (1 study, 58 participants: Abdul‐Rahman 2007).

Antiplatelet versus antiplatelet studies

Thirty‐four studies comparing an antiplatelet drug with a second antiplatelet drug in people with CKD were published between 1980 and 2018. The number of CKD participants ranged from 6 to 4983 participants (median 85 participants) and the mean age of participants ranged from 33 to 74.4 years. The duration of follow‐up ranged from 2 days to 48 months (median four months).

Twelve studies were conducted in people with CKD not yet requiring dialysis (10,958 participants: CASSIOPEIR 2014; CILON‐T 2010; Dash 2013; EUCLID 2017; Khajehdehi 2002; Liang 2015; Movchan 2001; Ogawa 2008; OPT‐CKD 2018; PLATO 2009; TARGET 2000; TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006).

Thirteen studies evaluated treatment in people on HD (786 participants: Alexopoulos 2011; Hidaka 2013; J‐PADD 2014; Ota 1996; PIANO‐2 CKD 2011; PIANO‐3 2015; PIANO‐6 2017; Schnepp 2000; Sreedhara 1994; Teng 2018: Waseda 2016; Xydakis 2004; Yang 2016b).

Two studies enrolled kidney transplant recipients (122 participants: Frascà 1986; Kauffmann 1980).

In the studies that compared an antiplatelet with another antiplatelet, interventions included:

-

Acetylsalicylic acid

Aspirin versus clopidogrel (3 studies, 202 participants: Dash 2013; Xydakis 2004; Yang 2016b)

Aspirin versus clopidogrel versus ticlopidine (1 study, 30 participants: Schnepp 2000)

Aspirin versus sarpogrelate (1 study, 40 participants: Ogawa 2008)

-

Adenosine reuptake inhibitors

Dypiridamole versus aspirin (2 studies, 97 participants: Kauffmann 1980; Sreedhara 1994)

Dypiridamole versus defibrotide (1 study, 80 participants: Frascà 1986)

Dypiridamole versus aspirin versus dypiridamole plus aspirin versus placebo (1 study, 76 participants: Khajehdehi 2002)

Dypiridamole versus pentoxifylline (1 study, 40 participants: Movchan 2001)

-

Adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitors

Clopidogrel versus cilostazol (1 study, 74 participants: PIANO‐2 CKD 2011)

Clopidogrel plus cilostazol versus clopidogrel (1 study, 184 participants: CILON‐T 2010)

Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor (2 studies, 3701 participants: EUCLID 2017; PIANO‐6 2017)

Low‐dose clopidogrel versus high‐dose clopidogrel (1 study, 370 participants: Liang 2015)

Ticlopidine versus satigrel (1 study, 224 participants: Ota 1996)

-

Phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitors

Cilostazol versus beraprost sodium (1 study, 72 participants: J‐PADD 2014)

Cilostazol versus sarpogrelate (1 study, 35 participants: Hidaka 2013)

-

P2Y12 antagonists

Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel (3 studies, 3322 participants: OPT‐CKD 2018; PIANO‐3 2015; PLATO 2009)

Ticagrerol pre‐dialysis versus ticagrelor post‐dialysis (1 study, 14 participants: Teng 2018)

Prasugrel versus clopidogrel (3 studies, 1544 participants: Alexopoulos 2011; TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006; Waseda 2016)

-

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor

Abciximab versus tirofiban (1 study, 790 participants: TARGET 2000)

-

Other

Low versus high‐dose beraprost sodium (1 study, 600 participants: CASSIOPEIR 2014)

Excluded studies

For this update, we reassessed all previously excluded studies. We deleted 15 studies (not randomised or wrong population) and reclassified six studies as included studies; these were previously excluded due to less than two months of follow‐up. For the 2021 search, we excluded 17 new studies (82 reports) and identified 22 new reports of 6 already excluded studies. In total, we have excluded 29 studies (119 reports).

Three studies were the wrong study design (Caravaca 1995a; Yang 2014a; Yeh 2017)

Eleven studies enrolled the wrong population (Bang 1994; EXCITE 2000; POISE‐2 2013; PRODIGY 2010; RAS‐CAD 2009; REPLACE‐2 2003; SPS3 2018; TRILOGY ACS 2010; Woo 1987; Wu 2018a; Zimmerman 1983).

Nine studies used the wrong intervention (Coli 2006; Foroughinia 2017; Lee 1997; NITER 2005; Perkovic 2004; STENO‐2 1999; Swan 1995a; Yoshikawa 1999; Zhang 2009a)

Six studies used the wrong comparator (AVERROES 2010; Changjiang 2015; Gorter 1998; Lindsay 1972; Sakai 1991; Zibari 1995).

See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Ongoing studies

Twenty‐six studies (27 reports) have yet to be completed (A‐CLOSE 2019; ALTIC 2016; ALTIC‐2 2018; ATTACK 2018; ChiCTR1900021393; IRCT2013012412256N1; IRCT2013100114333N8; IRCT20171023036953N1; LEDA 2017; Lemos Cerqueira 2018; NCT00272831; NCT01198379; NCT01743014; NCT02394145; NCT02459288; NCT03039205; NCT03150667; NCT03649711; Park 2010; PRASTO‐III 2018; SERENADE 2015; SONATA 2013; TROUPER 2020; TWILIGHT 2016; UMIN000003891; VA PTXRx 2018).

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in the included studies is summarised in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Methods for generating the random sequence were deemed to be at low risk of bias in 16 studies (AASER 2017; Alexopoulos 2011; ATACAS 2008CASSIOPEIR 2014; CHANCE 2013; CREDO 2005; Dash 2013; EUCLID 2017; FAVOURED 2009; Goicoechea 2012; JPAD 2008; Mozafar 2018; PIANO‐2 CKD 2011; PIANO‐3 2015; PIANO‐6 2017; UK‐HARP‐I 2005), at high risk of bias in three studies (Guo 1998; Kauffmann 1980; Rubin 1982), and unclear in 94 studies.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was judged to be a low risk of bias in 22 studies (Anderson 1974; ATACAS 2008; CASSIOPEIR 2014; CHARISMA 2006; CURE 2000; Dixon 2005; EARLY ACS 2005; EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; EPISTENT 1998; EUCLID 2017; FAVOURED 2009; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Giustina 1998; HOT 1993; Kaufman 2003; PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014; PURSUIT 1997; TARGET 2000; TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009; TRACER 2013), and unclear in 91 studies.

Blinding

Performance bias

Sixty‐four studies were blinded and considered to be at low risk of bias for performance bias (Abacilar 2015; Abdul‐Rahman 2007; Anderson 1974; Andrassy 1974; ATACAS 2008; CASSIOPEIR 2014; CHANCE 2013; CHARISMA 2006; Christopher 1987; CREDO 2005; CURE 2000; Dember 2005; Dixon 2005; Dodd 1980; Donadio 1984; EARLY ACS 2005; EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; EPISTENT 1998; ETDRS 1992; FAVOURED 2009; Fiskerstrand 1985; Gaede 2003; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Giustina 1998; Gröntoft 1985; Gröntoft 1998; Guo 1998; Hansen 2000; Harter 1979; HOT 1993; IMPACT II 1997; Kaegi 1974; Kauffmann 1980; Kaufman 2003; Kobayashi 1980; Kontessis 1993; Kooistra 1994; Koyama 1990; Michie 1977; Milutinovic 1993; Mozafar 2013; Nyberg 1984; Ota 1996; PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014; Pierucci 1989; PLATO 2009; PRISM‐PLUS 1998; PURSUIT 1997; Quarto Di Palo 1991; RAPPORT 1998; Reams 1985; RESIST 2008; Rubin 1982; Salter 1984; Sreedhara 1994; STOP 1995; TARGET 2000; Tayebi 2018; TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009; TRACER 2013; TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006; Weseley 1982). One study was judged to have unclear risk of bias (EUCLID 2017) and 48 studies were not blinded and were considered at high risk of performance bias.

Detection bias

Blinding of outcome assessment was judged to be at low risk of bias for 41 studies (AASER 2017; ATACAS 2008; CASSIOPEIR 2014; Chan 1987; CHANCE 2013; Cheng 1998a; Christopher 1987; CILON‐T 2010; CURE 2000; Dash 2013; EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; EPISTENT 1998; ETDRS 1992; EUCLID 2017; HOT 1993; IMPACT II 1997; Jiao 2013; JPAD 2008; Kontessis 1993; Koyama 1990; Movchan 2001; Nakamura 2001d; Nakamura 2002b; Ogawa 2008; PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014; PIANO‐2 CKD 2011; PREDIAN 2011; PRISM‐PLUS 1998; PURSUIT 1997; RAPPORT 1998; Rubin 1982; Schnepp 2000; Storck 1996; TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009; TRACER 2013; TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006; Waseda 2016; Weseley 1982; Xydakis 2004; Zäuner 1994). Seventy‐two studies were considered at high risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Follow‐up data was complete and judged to be at low risk of bias for 41 studies (AASER 2017; Abacilar 2015; Abdul‐Rahman 2007; Alexopoulos 2011; Andrassy 1974; CASSIOPEIR 2014; CHARISMA 2006; CREDO 2005; CURE 2000; Dember 2005; Dixon 2005; EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; EPISTENT 1998; ETDRS 1992; Gaede 2003; Ghorbani 2013; Goicoechea 2012; Gröntoft 1998; Hansen 2000; Hidaka 2013: HOT 1993; JPAD 2008; Kamper 1997; Kaufman 2003; Khajehdehi 2002; Kobayashi 1980; Liang 2015; Nyberg 1984; OPT‐CKD 2018; Ota 1996; PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014; PLATO 2009; Quarto Di Palo 1991; RAPPORT 1998; Reams 1985; Storck 1996; Tang 2014; TRACER 2013; TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006; Zäuner 1994), incomplete, and judged to be at high risk of bias for 24 studies (Chan 1987; Cheng 1998a; Dash 2013; Donadio 1984; EUCLID 2017; Fiskerstrand 1985; Frascà 1986; Ghorbani 2009; Giustina 1998; Gonzalez 1995; Gröntoft 1985; Harter 1979; J‐PADD 2014; Kaegi 1974; Kooistra 1994; Michie 1977; PIANO‐3 2015; PIANO‐6 2017; Rouzrokh 2010; Sreedhara 1994; Steiness 2018; TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009; UK‐HARP‐I 2005; Yang 2016b) and unclear in 48 studies.

Selective reporting

Fifty studies reported expected and clinically‐relevant outcomes and were deemed to be at low risk of bias (AASER 2017; Abacilar 2015; Alexopoulos 2011; ATACAS 2008; CASSIOPEIR 2014; CHANCE 2013; CHARISMA 2006; CREDO 2005; Creek 1990; CURE 2000; Dember 2005; Dixon 2005; EARLY ACS 2005; Ell 1982; EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; EPISTENT 1998; ETDRS 1992; FAVOURED 2009; Frascà 1986; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Gröntoft 1998; Harter 1979; HOT 1993; IMPACT II 1997; JPAD 2008; J‐PADD 2014; Kaegi 1974; Kaufman 2003; Kooistra 1994; Liang 2015; Michie 1977; Middleton 1992; Nyberg 1984; OPT‐CKD 2018; Ota 1996; PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014; PLATO 2009; PRISM‐PLUS 1998; PURSUIT 1997; RAPPORT 1998; Sreedhara 1994; STOP 1995; TARGET 2000; TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009; TRACER 2013; TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006; UK‐HARP‐I 2005; Yang 2016b), and 63 studies did not report patient‐centred outcomes of bleeding, cardiovascular events, adverse events, or death and were judged to be at high risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Fifty‐seven studies appeared to be free from other sources of bias (AASER 2017; Abacilar 2015; Abdul‐Rahman 2007, Alexopoulos 2011; Anderson 1974; CASSIOPEIR 2014; Chan 1987; CHANCE 2013; CURE 2000; Dash 2013; Dixon 2005; EARLY ACS 2005; EPISTENT 1998; ETDRS 1992; Frascà 1986; Frascà 1997; Ghorbani 2009; Ghorbani 2013; Giustina 1998; Goicoechea 2012; Gröntoft 1985; Hansen 2000; Hidaka 2013; Jiao 2013; JPAD 2008; J‐PADD 2014; Kaegi 1974; Kauffmann 1980; Khajehdehi 2002; Kobayashi 1980; Kontessis 1993; Kooistra 1994; Liang 2015; Michie 1977; Milutinovic 1993; Mozafar 2013; Mozafar 2018; Nakamura 2001d; Nakamura 2002b; Nyberg 1984; Ogawa 2008; PIANO‐2 CKD 2011; PIANO‐3 2015; PIANO‐6 2017; Quarto Di Palo 1991; RESIST 2008; Rouzrokh 2010; Rubin 1982; Salter 1984; Schulze 1990; Storck 1996; Tang 2014; TARGET 2000; Tayebi 2018; TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006; Yang 2016b; Zäuner 1994), 33 studies reported other sources of bias and were judged to be at high risk (Andrassy 1974; CHARISMA 2006; Cheng 1998a; CREDO 2005; Creek 1990; Dember 2005; Ell 1982; EPIC 1994; EPILOG 1997; FAVOURED 2009; Fiskerstrand 1985; Gaede 2003; GLOBAL LEADERS 2018; Gröntoft 1998; Guo 1998; Harter 1979; HOT 1993; IMPACT II 1997; Kamper 1997; Kaufman 2003; Middleton 1992; OPT‐CKD 2018; PEGASUS‐TIMI 54 2014; PLATO 2009; PRISM‐PLUS 1998; PURSUIT 1997; RAPPORT 1998; Sreedhara 1994; STOP 1995; Teng 2018; TRA 2P‐TIMI 50 2009; TRACER 2013; UK‐HARP‐I 2005), and risk of bias was judged to be unclear in 23 studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Antiplatelet agents versus control

Fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction

Antiplatelet agents probably reduced the risk of fatal or nonfatal MI in people with CKD (Analysis 1.1 (18 studies, 15,289 participants): RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.99; I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 1: Fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction

Fatal or nonfatal stroke

It is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference to fatal or nonfatal stroke in people with CKD (Analysis 1.2 (12 studies, 10,382 participants): RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.59; I² = 37%; very low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision. There was moderate heterogeneity observed between studies. Antiplatelet agents were used both for primary and secondary prevention.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 2: Fatal or nonfatal stroke

Death (any cause)

Antiplatelet agents may have little or no effect on death (any cause) in people with CKD (Analysis 1.3 (35 studies, 18,241 participants): RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.06; I² = 14%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 3: Death (any cause)

Haemorrhagic stroke

Antiplatelet agents had uncertain effects on haemorrhagic stroke in people with CKD (Analysis 1.4 (9 studies, 6844 participants): RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.17; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 4: Haemorrhagic stroke

Cardiovascular death

It is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference to cardiovascular death in people with CKD (Analysis 1.5 (21 studies, 9606 participants): RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.15; I² = 32%; very low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias, imprecision, and inconsistency. There was moderate heterogeneity observed between studies.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 5: Cardiovascular death

Fatal bleeding

It is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference to fatal bleeding in people with CKD (Analysis 1.6 (21 studies, 7629 participants): RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.10 to 19.48; I² = 30%; very low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for Risk of Bias, imprecision, and inconsistency. There was moderate heterogeneity observed between studies.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 6: Fatal bleeding

Major bleeding

Major bleeding events included: retroperitoneal; intra‐articular; intra‐ocular, intracranial or intracerebral haemorrhage; gastrointestinal bleeding; bleeding that was fatal, life‐threatening, disabling or required transfusion; corrective surgery or hospitalisation, with or without a fall in haemoglobin (Hb) level of at least 2 g/dL; or melena.

Antiplatelet agents probably increased major bleeding in people CKD (Analysis 1.7 (29 studies, 16,194 participants): RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.65; I² = 12%; moderate certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 7: Major bleeding

Minor bleeding

Minor bleeding events were described as follows: not serious or significant; epistaxis; ecchymoses or bruising; blood loss and a drop of more than 10% points in the HCT or of 3 g/dL or more in the Hb concentration; not requiring transfusion; hospitalisation; and event‐related study visit; bleeding from cannulation sites, or haematuria.

Antiplatelet agents may increase the risk of minor bleeding in people with CKD (Analysis 1.8 (21 studies, 13218 participants): RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.90; I² = 58%; low certainty evidence). The was heterogeneity was moderate. The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and inconsistency.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 8: Minor bleeding

Kidney failure (end‐stage kidney disease)

Antiplatelet agents may have little or no effect on kidney failure (Analysis 1.9 (11 studies, 1722 participants): RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.14; I² = 23%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision. There was low heterogeneity observed between the studies.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 9: Kidney failure

Doubling of serum creatinine

Antiplatelet agents may reduce doubling of SCr in people with CKD (Analysis 1.10 (3 studies, 217 participants): RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.86; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 10: Doubling of serum creatinine

Kidney transplant graft loss

Antiplatelet agents had uncertain effects on kidney transplant graft loss (Analysis 1.11 (2 studies, 91 participants): RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.01; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 11: Kidney transplant graft loss

Transplant rejection

Antiplatelet agents may have little or no effect on kidney transplant rejection (Analysis 1.12 (2 studies, 97 participants): RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.19; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 12: Transplant rejection

Creatinine clearance

It is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference to CrCl in people with CKD (Analysis 1.13 (3 studies, 90 participants): MD ‐5.46 mL/min, 95% CI ‐12.33 to 1.41; I² = 38%; very low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision. There was moderate heterogeneity observed between studies.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 13: Creatinine clearance

Proteinuria

It is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference to proteinuria in people with CKD (Analysis 1.14 (3 studies, 80 participants): MD ‐0.74 g/day, 95% CI ‐1.35 to ‐0.13; very low certainty evidence) with substantial heterogeneity in the analysis (I² = 94%) which was as a result of Zäuner 1994; however, there was no difference in the direction of the effect when this study was removed from the meta‐analysis (MD ‐0.14 g/day, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.08). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency, and optimal information size not met.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 14: Proteinuria

Dialysis access failure (thrombosis or loss of patency)

For all access types, it is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference in reducing the risk of HD access failure (Analysis 1.15 (17 studies, 2847 participants): RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.78; I² = 46%; very low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias, indirectness, and inconsistency. There was moderate heterogeneity in this analysis which we explored using subgroup analysis by access type. In these analyses, it is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents (aspirin, sarpogrelate, ticlopidine, or clopidogrel with or without prostacyclin) made any difference in reducing the risk of fistula thrombosis or patency failure by 50% (Analysis 1.15.1 (10 studies, 1741 participants): RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.69; I² = 17%; very low certainty evidence), or shunt or graft failure (Analysis 1.15.2 (5 studies, 1052 participants): RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.03; I² = 49%; very low certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference to fistula or graft, or central venous catheter thrombosis (Analysis 1.15.3 (1 study, 16 participants): RR 0.50, 95% 0.06 to 4.47; very low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.15.4 (1 study, 38 participants); 0.44, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.20; very low certainty evidence) respectively. Overall, there was no evidence of subgroup interaction based on access type across all types, suggesting the specific vascular access (fistula, graft, shunt, or central venous catheter) (P = 0.13%) was not an effect modifier for the treatment effects observed and indicating the overall effect estimate was the most appropriate.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 15: Dialysis access failure (thrombosis or loss of patency)

Early access failure (within eight weeks of access creation)

Antiplatelet agents may reduce early dialysis vascular access thrombosis (Analysis 1.16 (8 studies, 1525 participants): RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.70; I²= 8%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and optimal information size not met.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 16: Early access thrombosis (before 8 weeks)

Loss of primary unassisted patency

Two studies (Dixon 2005; Michie 1977) reported a loss of unassisted patency with Dixon 2005 providing 99% of the events. Antiplatelet agents may have little or no effect on reduction of loss of unassisted patency (Analysis 1.17 (2 studies, 665 participants): RR 0.95, 95% 0.89 to 1.03; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 17: Loss of primary unassisted patency

Failure to attain access suitability of dialysis (maturation)

The definitions of access suitability included: the ability to use the fistula for dialysis with two needles and maintain a blood flow rate ≥ 300 mL/min during eight of 12 dialysis sessions occurring during a 30 day suitability ascertainment period (Dember 2005); failure to use graft by week 12 in patients with a catheter for access (Dixon 2005); fistula ceased to function (Gröntoft 1985); permanent shunt thrombosis (Harter 1979); and failure to develop adequate flow (Michie 1977). It is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference in the reduction of failure to attain access suitability (Analysis 1.18 (5 studies, 1503 participants): RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.15; I² = 59%, very low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision. There was moderate heterogeneity potentially due to the differences in definitions of access suitability.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 18: Failure to attain suitability for dialysis

Need for intervention to attain patency or assist maturation

The need for the intervention to attain patency or assist maturation was described: as surgical revision (FAVOURED 2009: Kaegi 1974); thrombectomy (Abacilar 2015; Michie 1977); percutaneous intervention to restore patency or promote maturation (Dember 2005); or angioplasty (Dixon 2005).

Antiplatelet agents may have little or no effect on the reduction of the risk for the need for the intervention to attain patency or assist maturation in people treated with HD (Analysis 1.19 (6 studies, 2067 participants): RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.05; I² = 0%: low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 19: Need for intervention to attain patency or assist maturation

All‐cause hospitalisation

Antiplatelet agents may have little or no effect on all‐cause hospitalisation in people treated with HD (Analysis 1.20 (3 studies, 3535 participants): RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.10; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 20: Hospitalisation (any cause)

Cardiovascular hospitalisation

It is uncertain whether antiplatelet agents made any difference in cardiovascular hospitalisation in CKD and HD (Analysis 1.21 (3 studies, 3535 participants): RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.14; I² = 46%; very low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for Risk of Bias, inconsistency and imprecision. There was moderate heterogeneity potentially due to differences in the adjudication of the outcome.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 21: Cardiovascular hospitalisation

Treatment withdrawal

Antiplatelet agents may have little or no effect on withdrawal from treatment compared with placebo or no treatment in CKD and HD (Analysis 1.22 (15 studies, 2669 participants): RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.14; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antiplatelet agents versus control, Outcome 22: Treatment withdrawal

Prasugrel versus clopidogrel

TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006 compared prasugrel plus aspirin with clopidogrel plus aspirin and provided data for 1490 people with CKD during a median follow‐up of 14.5 months. Data were not available for fatal or nonfatal stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, fatal bleeding, kidney failure, doubling of SCr, kidney transplant graft loss, transplant rejection, CrCl, proteinuria, dialysis access failure, early access thrombosis, loss of primary unassisted patency, failure to attain suitability for dialysis, need for intervention to attain patency or assist maturation, all‐cause hospitalisation, cardiovascular hospitalisation, and treatment withdrawal.

Fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction

TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006 reported no difference between prasugrel plus aspirin compared to clopidogrel plus aspirin on fatal or nonfatal MI (Analysis 2.1 (1 study, 1490 participants): RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.05). Since not all participants experienced MI before treatment allocation, antiplatelet agents were used both for primary and secondary prevention.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Prasugrel versus clopidogrel, Outcome 1: Fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction

Death (any cause)

TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006 reported no difference between prasugrel plus aspirin compared to clopidogrel plus aspirin death (any cause) (Analysis 2.2 (1 study, 1490 participants): RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.18).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Prasugrel versus clopidogrel, Outcome 2: Death (any cause)

Cardiovascular death

TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006 reported no difference between prasugrel plus aspirin compared to clopidogrel plus aspirin on cardiovascular death (Analysis 2.3 (1 study, 1469 participants): RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.87 to 2.10).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Prasugrel versus clopidogrel, Outcome 3: Cardiovascular death

Major bleeding

Major bleeding was defined according to the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) criteria for major bleeding (intracranial haemorrhage, clinically evident bleeding including imaging and a drop in the Hb of ≥5 g/dL). TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006 reported no difference between prasugrel plus aspirin compared to clopidogrel plus aspirin on major bleeding (Analysis 2.4 (1 study, 1475 participants): RR 1.49, 95% CI 0.83 to 2.66).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Prasugrel versus clopidogrel, Outcome 4: Major bleeding

Minor bleeding

Minor bleeding was defined as clinically evident bleeding including imaging and a fall in the Hb of between 3 and 5 g/dL. TRITON‐TIMI 38 2006 reported no difference between prasugrel plus aspirin compared to clopidogrel plus aspirin on minor bleeding (Analysis 2.5 (1 study, 1469 participants): RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.87 to 2.10).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Prasugrel versus clopidogrel, Outcome 5: Minor bleeding

Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel

Three studies (OPT‐CKD 2018; PIANO‐3 2015; PIANO‐6 2017) compared ticagrelor with or without aspirin with clopidogrel alone or in combination with aspirin. Data were not available for haemorrhagic stroke, kidney failure, doubling of SCr, kidney transplant graft loss, transplant rejection, CrCl, proteinuria, dialysis access failure, early access thrombosis, loss of primary unassisted patency, failure to attain suitability for dialysis, need for intervention to attain patency or assist maturation, all‐cause hospitalisation, and cardiovascular hospitalisation.

Fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction

OPT‐CKD 2018 reported no difference between ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel on fatal or nonfatal MI in CKD during 30 days follow‐up (Analysis 3.1 (1 study, 60 participants): RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 70.83). Since not all participants experienced MI before treatment allocation, antiplatelet agents were used both for primary and secondary prevention.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, Outcome 1: Fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction

Fatal or nonfatal stroke

OPT‐CKD 2018 reported no difference between ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel on fatal or nonfatal MI in CKD during 30 days follow‐up (Analysis 3.2 (1 study, 60 participants): RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 70.83). Since it was not reported if all participants experienced a stroke before treatment allocation, it was not clear if antiplatelet agents were used either for primary or secondary prevention.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, Outcome 2: Fatal or nonfatal stroke

Death (any cause)

OPT‐CKD 2018 and PIANO‐6 2017 reported the effect of ticagrelor with clopidogrel while PIANO‐3 2015 reported the effect of ticagrelor plus aspirin with clopidogrel plus aspirin between 14 to 30 days follow‐up. Antiplatelet agents had uncertain effects on death (any cause) in CKD and HD (Analysis 3.3 (3 studies, 137 participants): RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.19 to 20.90; very low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, Outcome 3: Death (any cause)

Cardiovascular death

OPT‐CKD 2018 and PIANO‐6 2017 reported the effect of ticagrelor with clopidogrel while PIANO‐3 2015 reported the effect of ticagrelor plus aspirin with clopidogrel plus aspirin between 14 to 30 days follow‐up. Antiplatelet agents had uncertain effects on cardiovascular death in CKD and HD (Analysis 3.4 (3 studies, 137 participants): RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.25 to 99.59; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, Outcome 4: Cardiovascular death

Fatal bleeding

PIANO‐3 2015 reported the effect of ticagrelor plus aspirin with clopidogrel plus aspirin and PIANO‐6 2017 reported the effect of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in HD during 14 days follow‐up. No fatal bleeding events were reported in either study (Analysis 3.5; 2 studies, 77 participants).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, Outcome 5: Fatal bleeding

Major bleeding

Major bleeding was assessed using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) (OPT‐CKD 2018) or according to the PLATO criteria (PIANO‐3 2015). OPT‐CKD 2018 reported the effect of ticagrelor with clopidogrel during 30 days follow‐up, while PIANO‐3 2015 reported the effect of ticagrelor plus aspirin with clopidogrel plus aspirin during 14 days follow‐up. Antiplatelet agents had uncertain effects on major bleeding in CKD and HD (Analysis 3.6 (2 studies, 85 participants): RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.87; low certainty evidence). The evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, Outcome 6: Major bleeding

Minor bleeding

Minor bleeding was assessed using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC). PIANO‐6 2017 reported no difference between ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel on minor bleeding in HD during 14 days follow‐up (Analysis 3.7 (1 study, 52 participants): RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.10 to 10.90).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, Outcome 7: Minor bleeding

Treatment withdrawal

PIANO‐6 2017 reported no difference between ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel on treatment withdrawal in HD during 14 days follow‐up (Analysis 3.8 (1 study, 52 participants): RR 1.59, 95% CI 0.18 to 14.19).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, Outcome 8: Treatment withdrawal

Clopidogrel (low‐dose) versus clopidogrel (high‐dose)

Liang 2015, which compared a low‐ versus high‐dose clopidogrel, provided data for 370 people with CKD during 30 days follow‐up. Data were not available for fatal or nonfatal MI, fatal or nonfatal stroke, death (any cause), fatal bleeding, major bleeding, minor bleeding, kidney failure, doubling of SCr, kidney transplant graft loss, transplant rejection, CrCl, proteinuria, dialysis access failure, early access thrombosis, loss of primary unassisted patency, failure to attain suitability for dialysis, need for intervention to attain patency or assist maturation, all‐cause hospitalisation, cardiovascular hospitalisation, and treatment withdrawal.

Haemorrhagic stroke

Liang 2015 reported no haemorrhagic stroke events with either low‐dose or high‐dose clopidogrel (Analysis 4.1 (1 study, 370 participants)).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Clopidogrel (low dose) versus clopidogrel (high dose), Outcome 1: Haemorragic stroke

Cardiovascular death

Liang 2015 reported no difference between low‐ versus high‐dose clopidogrel on cardiovascular death (Analysis 4.2 (1 study, 370 participants): RR 4.04, 95% CI 0.46 to 35.83).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Clopidogrel (low dose) versus clopidogrel (high dose), Outcome 2: Cardiovascular death

Abciximab versus tirofiban

TARGET 2000 compared abciximab plus aspirin with tirofiban plus aspirin and provided unpublished data for 790 people with CKD between 6 and 12 months follow‐up. Data were not available for fatal or nonfatal stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, cardiovascular death, fatal bleeding, major bleeding, minor bleeding, kidney failure, doubling of SCr, kidney transplant graft loss, transplant rejection, CrCl, proteinuria, dialysis access failure, early access thrombosis, loss of primary unassisted patency, failure to attain suitability for dialysis, need for intervention to attain patency or assist maturation, all‐cause hospitalisation, cardiovascular hospitalisation, and treatment withdrawal.

Fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction