Abstract

Introduction

COVID-19 infections have become an urgent worldwide public health concern. Although it is primarily a respiratory disease, up to two-thirds of hospitalised COVID-19 patients exhibit nervous system damage and an increased risk of frailty. In this study, we aim to investigate the relationship between frailty and cognitive function disorders in patients with COVID-19 with a systematic review and meta-analysis approach.

Methods and analysis

This meta-analysis has been registered by the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. We will search for relevant studies from PubMed, Embase, Chinese Biological Medical Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Database, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases, from their inception to 5 July 2021. We will also search reference lists of selected articles for additional studies. Our search strategy will have no language restrictions. We will employ a fixed or random-effects model to calculate OR and 95% CIs for pooled data, and assess heterogeneity using Cochrane’s Q and I2 tests. The primary outcome will be the rate of cognitive disorders related to frailty in old patients with COVID-19.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not essential since data will be extracted from previously published studies. The results of this meta-analysis will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021257148.

Keywords: COVID-19, geriatric medicine, mental health, delirium & cognitive disorders, old age psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review seeking to elucidate the relationship between frailty and cognitive function disorders in patients with COVID-19.

The findings of this study will provide relevant insights to guide doctors to adopt some measures to prevent the effect of frailty on cognition.

The number of original studies is limited, thus, the strength of evidence needs to be examined cautiously.

Introduction

The recent wave of infections by the novel coronavirus in India calls for urgent and numerous attention to be paid to this epidemic owing to the serious threat on human health worldwide.1 2 COVID-19 infection damages the function of various organs or systems, such as the central nervous system (CNS), possibly through infiltration of inflammatory cytokines into the brain that cause injury to the CNS.3–5 Consequently, people who contract novel coronavirus infections, especially the elderly, may experience neurologic and mental disorders,6 7 with the following as main manifestations: cognitive and attention deficits, circadian rhythm and mood disorders, as well as changes in psychomotor function.8 Cognitive function disorder is a serious illness that negatively impacts patients’ lives, including causing deaths. Moreover, a decline in cognitive function has been associated with increased patient mortality, especially in people aged between 65 and 79 years.9

Frailty, a health burden that exacerbates incidence of other diseases and medical expenses, is an age-related clinical state characterised by deterioration in the physiological capacity of organs and systems.10 Previous studies have shown that the risk of frailty greatly increases with age,11 suggesting that elderly people with frailties, who suffer from novel coronavirus pneumonia, are likely to be at a greater risk of cognitive impairment. Research evidence has suggested that this phenomenon may potentially be attributed to inflammation and oxidative stress.12 However, findings from another study suggested that COVID-19 could accelerate the ageing process and increase frailty, although with no decline in cognitive function.13 Therefore, there is need to elucidate the relationship between frailty and cognitive function disorders in patients with COVID-19.

Particularly, knowledge on whether reducing the rate of frailties by enhancing the state of the body in elderly COVID-19 patients can improve their cognitive function is imperative to effective clinical therapies. As far as we know, no systematic review and meta-analysis has evaluated the relationship between frailty and cognitive disorders in patients with COVID-19, necessitating further explorations. In this study, we aim to qualitatively and quantitatively investigate the effect of frailty on cognitive disorders in elderly patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia using a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

This meta-analysis will be performed in accordance to the guidelines by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocols.14 All analyses will be based on previously published studies, thus neither ethical approval nor patient consent will be required.

Literature search

We will search for and retrieve relevant studies across various databases, including PubMed, Embase, Chinese Biological Medical Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Database and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We will also search reference lists of the selected articles to obtain additional studies. There are no language restrictions during the search process, and all studies describing the relationship between frailty and cognitive function in patients with COVID-19 will be enrolled in this systematic review. These will include prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies, cross-sectional researches and observational researches. The search strategy will employ the following terms: ‘COVID-19 Virus Disease’ or ‘COVID-19’ or ‘SARS-CoV-2 and ‘frailty’ and ‘cognition disorders’. A summary of the full search approach of PubMed is outlined in table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy of PubMed

| Search | Query |

| #1 | “COVID-19”[MeSH Terms] |

| #2 | "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "covid 19 virus disease"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "disease covid 19 virus"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "covid 19 virus infection"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "2019 ncov infection"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "infection 2019 ncov"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "coronavirus disease 19"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "2019 novel coronavirus disease"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "2019 novel coronavirus infection"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "2019 ncov disease"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "disease 2019 ncov"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "covid19"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "coronavirus disease 2019"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "sars coronavirus 2 infection"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "sars cov 2 infection"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "covid 19 pandemic"[All Fields] OR "covid 19"[MeSH Terms] OR "covid 19"[All Fields] OR "pandemic covid 19"[All Fields] |

| #3 | #1 or #2 |

| #4 | "frailty"[MeSH Terms] |

| #5 | "frailty"[MeSH Terms] OR "frailty"[All Fields] OR "frailties"[All Fields] OR ("frail"[All Fields] OR "frails"[All Fields] OR "frailty"[MeSH Terms] OR "frailty"[All Fields] OR "frailness"[All Fields]) OR ("frailty"[MeSH Terms] OR "frailty"[All Fields] OR ("frailty"[All Fields] AND "syndrome"[All Fields]) OR "frailty syndrome"[All Fields]) OR ("frailty"[MeSH Terms] OR "frailty"[All Fields] OR "debility"[All Fields]) OR ("frailty"[MeSH Terms] OR "frailty"[All Fields] OR "debilities"[All Fields]) |

| #6 | #4 or #5 |

| #7 | "cognition disorders"[MeSH Terms] |

| #8 | "cognition disorders"[MeSH Terms] OR ("cognition"[All Fields] AND "disorders"[All Fields]) OR "cognition disorders"[All Fields] OR ("disorder"[All Fields] AND "cognition"[All Fields]) OR "disorder cognition"[All Fields] OR ("cognition disorders"[MeSH Terms] OR ("cognition"[All Fields] AND "disorders"[All Fields]) OR "cognition disorders"[All Fields] OR ("disorders"[All Fields] AND "cognition"[All Fields]) OR "disorders cognition"[All Fields]) OR ("cognition disorders"[MeSH Terms] OR ("cognition"[All Fields] AND "disorders"[All Fields]) OR "cognition disorders"[All Fields] OR "overinclusion"[All Fields] OR "overinclusive"[All Fields] OR "overinclusiveness"[All Fields]) |

| #9 | #7 or #8 |

| #10 | #3 and #6 and #9 |

Eligibility criteria

Study design

All relevant studies, including prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies, cross-sectional researches and observational researches, will be included in this systematic review. Due to scarcity of original trials on COVID-19, we will acquire as many related studies as possible by improving the sensitivity of the search strategy.

Participants

Elderly COVID-19 patients (≥65 years old), with cognitive impairment, will be considered. The subjects who are used to investigate the relationship between frailty and cognition disorders, and the confounding factors that affect the rate of cognitive function disorders will be emended. There will be no restriction on the race due to expected limitations in the number of original studies.

Exposures

The main exposure factor will be whether presence of frailty. Therefore, we will assess the frailty scores using a relevant scale, and not just the ‘FRAIL’ scale only.

Outcomes

The primary outcome will be the rate of cognitive disorders in elderly COVID-19 patients with frailty. Cognitive disorder will be assessed using the Brief Assessment of Impaired Cognition tool, which focuses on the self and informant reports, supermarket fluency, and category cued memory test.15 Secondary outcomes will comprise the rate of mortality and length of hospitalisation.

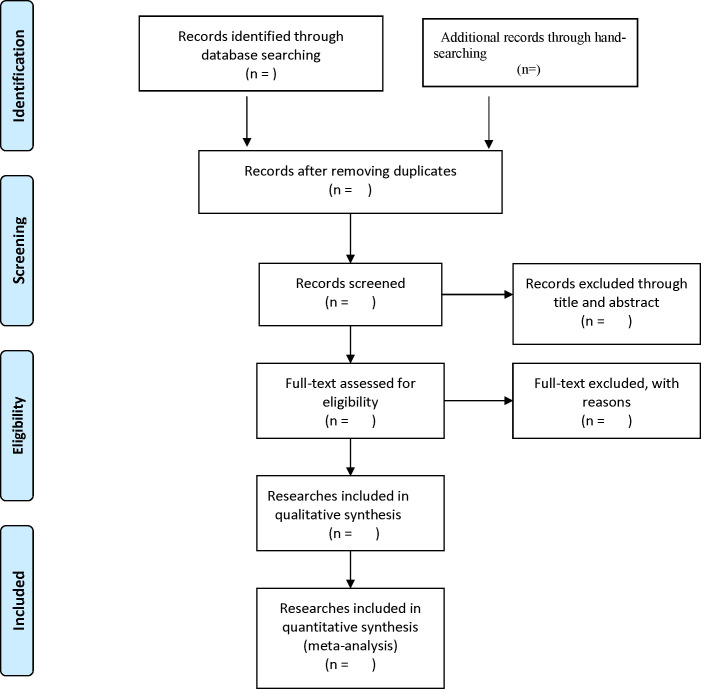

Study selection and data collection

Relevant studies will be independently searched and selected by two reviewers, and any differences between them resolved via further discussions with a senior reviewer. After removing the duplicate items, we will evaluate the preliminary quality of the studies based on the title and abstract. Then, we will make the final evaluation by reading the full text. A schematic representation of the selection procedure is presented in figure 1. A standard collection form will be used for data retrieval, which will also be independently done by the two reviewers. Any discrepancies between them will be resolved through discussion with the aforementioned senior reviewer. Data to be extracted will include, name of the first author, date of publication, sample size, patient characteristics, type of study, number of patients with frailty, grade of frailty, number of patients with cognition disorders (recorded separately in frailty and non-frailty group), number of patients without cognition disorders (recorded separately in frailty and non-frailty group), number of deaths, rate of mortality, and length of hospital stay. In cases where there is missing data, we will attempt to contact the corresponding author to acquire it.

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of literature search and selection.

Determination of risk-of-bias and assessment of study quality

Quality and bias of the enrolled studies will be assessed using relevant tools. Specifically, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale will be used to evaluate bias in non-randomised studies targeting the following aspects: objects’ selection, study comparability and outcome measurement.16 The decisions will be determined as ‘low’, or ‘high’ risk of bias or ‘some concerns’ along with the tool of evaluating the risk of bias. Risk of bias in each included study will be independently assessed by two reviewers. In addition, risk of bias and quality assessment will also be determined using the following measures: Inconsistency, Indirectness, Imprecision, Sensitivity, Specificity and Pooled C-statistic tool.17 Furthermore, we will apply the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation criteria to evaluate strength of the evidence.18

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Data synthesis and meta-analysis will be performed using the Review Manager V.5.4 software (The Cochrane library, Oxford, England). Briefly, we will calculate OR and mean differences with 95% CIs for categorical and continuous data. On the other hand, we will calculate heterogeneity across the included studies using the χ2 and I2 tests, with I2 >50% or p<0.10 to be considered significantly heterogeneous. We will adopt the random-effects model where heterogeneity exists among the studies, otherwise, the fixed-effect model will be applied.19

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses, and assessment of publication bias

Where there is a high degree of heterogeneity, we will perform subgroup analysis based on the level of frailty and age group. Subgroup analysis will only be performed in groups that have at least each group two studies. On the other hand, sensitivity analysis will be performed by excluding low-quality studies, and if the final pooled results are stable after this exclusion, then the meta-analysis will be deemed reliable.20 Publication bias will be investigated by generating funnel plots and the Egger’s test as previously described.21 22

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first meta-analysis to investigate the association between frailty and cognitive function disorders. The findings of the study will provide relevant insights into the effect of frailty on the incidence of cognitive disorders in elderly COVID-19 patients. Frailty incidence significantly increases with increase in age. Frailty, which refers to a reduction in the ability to respond to stress, is more common in elderly. And cognitive impairment is a serious threat to healthy living. Previous studies have shown that age is the most important independent risk factor for occurrence of cognitive disorders.23 Notably, COVID-19 causes serious inflammation in these patients, while inflammatory factors may increase the risk of nerve injure. Therefore, it is important to understand the relationship between frailty and cognitive function disorders in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia.

We anticipate several limitations in the present meta-analysis. First, the number of original studies is limited, which might affect the strength of the obtained evidence. Second, the non-randomised studies will be included, which might affect the interpretation of final pooled results. Finally, considering the limitation of original studies, we may not perform any other subgroup analysis apart from the level of frailty and age group, thus the heterogeneity may not be fully explained if a high degree of heterogeneity exists in this meta-analysis.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis is expected to reveal the relationship between frailty and cognitive disorders in elderly COVID-19 patients.

Patient and public involvement

No patients involved.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not essential since all data will be extracted from previously published studies. Results of this meta-analysis will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BJ and XL designed this review and made the search strategy. BJ and MC will do the literature search, data collection. BJ and MF will perform the data synthesis and analysis, and BJ was major contributor to write the protocol draft. BJ and MC have contributions to this revised manuscript. JL and CC revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.The Lancet . India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet 2020;395:1315. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30938-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu H. The epidemic situation in India is almost out of control, and the world is working together to help. International Business Daily, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alomari SO, Abou-Mrad Z, Bydon A. COVID-19 and the central nervous system. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020;198:106116. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asadi-Pooya AA, Simani L. Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. J Neurol Sci 2020;413:116832. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heneka MT, Golenbock D, Latz E, et al. Immediate and long-term consequences of COVID-19 infections for the development of neurological disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020;12:69. 10.1186/s13195-020-00640-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonso-Lana S, Marquié M, Ruiz A, et al. Cognitive and neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 and effects on elderly individuals with dementia. Front Aging Neurosci 2020;12:588872. 10.3389/fnagi.2020.588872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker HA, Safavynia SA, Evered LA. The ‘third wave’: impending cognitive and functional decline in COVID-19 survivors. Br J Anaesth 2021;126:44–7. 10.1016/j.bja.2020.09.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maldonado JR. Delirium pathophysiology: an updated hypothesis of the etiology of acute brain failure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018;33:1428–57. 10.1002/gps.4823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lv X, Li W, Ma Y, et al. Cognitive decline and mortality among community-dwelling Chinese older people. BMC Med 2019;17:63. 10.1186/s12916-019-1295-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dent E, Martin FC, Bergman H, et al. Management of frailty: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. The Lancet 2019;394:1376–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31785-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, et al. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet 2019;394:1365–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31786-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabrício DdeM, Chagas MHN, Diniz BS. Frailty and cognitive decline. Transl Res 2020;221:58–64. 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greco GI, Noale M, Trevisan C, et al. Increase in frailty in nursing home survivors of coronavirus disease 2019: comparison with noninfected residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:943–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jørgensen K, Nielsen TR, Nielsen A, et al. Validation of the brief assessment of impaired cognition and the brief assessment of impaired cognition questionnaire for identification of mild cognitive impairment in a memory clinic setting. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020;35:907–15. 10.1002/gps.5312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Guideline Centre (UK) . Multimorbidity: assessment, prioritisation and management of care for people with commonly occurring multimorbidity. London: National Institute for health and care excellence (UK), 2016. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK409218/#ch7.s36 [PubMed]

- 18.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. Grade: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioannidis JPA. Interpretation of tests of heterogeneity and bias in meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract 2008;14:951–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.00986.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leeflang MMG. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20:105–13. 10.1111/1469-0691.12474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin L, Chu H, Murad MH, et al. Empirical comparison of publication bias tests in meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:1260–7. 10.1007/s11606-018-4425-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson DA, Savva GM, Kenny RA. Frailty and cognitive impairment--a review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev 2013;12:840–51. 10.1016/j.arr.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.