Abstract

Purpose:

Heavy and prolonged use of cannabis is associated with several adverse health, legal and social consequences. Although cannabis use impacts all U.S. racial/ethnic groups, studies have revealed racial/ethnic disparities in the initiation, prevalence, prevention and treatment of cannabis use and Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD). This review provides an overview of recent studies on cannabis and CUD by race/ethnicity and a discussion of implications for cannabis researchers.

Findings:

The majority of studies focused on cannabis use and CUD among African American/Black individuals, with the smallest number of studies found among Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders. The limited number of studies highlight unique risk and protective factors for each racial/ethnic group, such as gender, mental health status, polysubstance use and cultural identity.

Summary:

Future cannabis studies should aim to provide a deeper foundational understanding of factors that promote the initiation, maintenance, prevention and treatment of cannabis use and CUD among racial/ethnic groups. Cannabis studies should be unique to each racial/ethnic group and move beyond racial comparisons.

Keywords: Cannabis and race, Marijuana, Trends in cannabis use, Racial minority cannabis use, Cannabis use risk factors, Prevalence of cannabis use

Introduction

In 2019, approximately 48 million people (17.5%) ages 12 and over in the United States reported using cannabis in the past year [1]. Moreover, among past-year cannabis users, 3.5 million reported initiating cannabis use for the first time that year. The heavy and prolonged use of cannabis has been linked to several adverse health effects such as memory impairment, issues with executive functioning, and increased risk for developing a mental illness [2, 3, 4]. Furthermore, the literature posits that 30% of weekly cannabis users will be diagnosed with Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD) in their lifetime [5]. Despite the associated health risks, the perceived risk associated with weekly cannabis use has declined among all age groups (i.e., 12 and over) within the past-year, indicating increased likelihood for problematic use [1]. The increased risk of problematic cannabis use highlights the need for more research on prevention, treatment and policy interventions that target cannabis use, especially among understudied and underserved populations who often experience the most detrimental health, social and legal consequences of cannabis use, such as racial/ethnic minorities [6].

Although cannabis use is a significant public health problem for all racial/ethnic groups, several racial/ethnic differences have been observed in the prevalence and consequences of use, as well as in the prevention and treatment of cannabis use. For example, in a recent review of time trends in U.S. prevalence of cannabis use and CUD [7], findings revealed an increase in the prevalence of adult cannabis use for all racial/ethnic groups and other sociodemographic groups (e.g., men, women, all income levels, all education levels) since 2007. However, a marked increase in cannabis use was noted among African American/Black adolescents and adults, representing a significant shift in the historical pattern of African American/Black individuals displaying similar or lower rates of cannabis use and CUD relative to their White counterparts [8]. Moreover, studies highlight the racial disparities observed in the prevalence of emergency department visits [9], referral to cannabis treatment [10] and treatment utilization and outcomes [11, 12]. These studies underscore the importance of contextualizing data by assessing and considering race/ethnicity throughout the entire development, execution and dissemination of research in the cannabis field. The purpose of this review is to describe the prevalence of current cannabis use by race using data from a national surveillance system, provide an overview of current studies (published between 2017–2021) on cannabis use among racial/ethnic minorities and then discuss real world implications for cannabis researchers who seek to decrease cannabis-related disparities among racial/ethnic minorities.

Prevalence of Current Cannabis Use among Racial/Ethnic Minorities

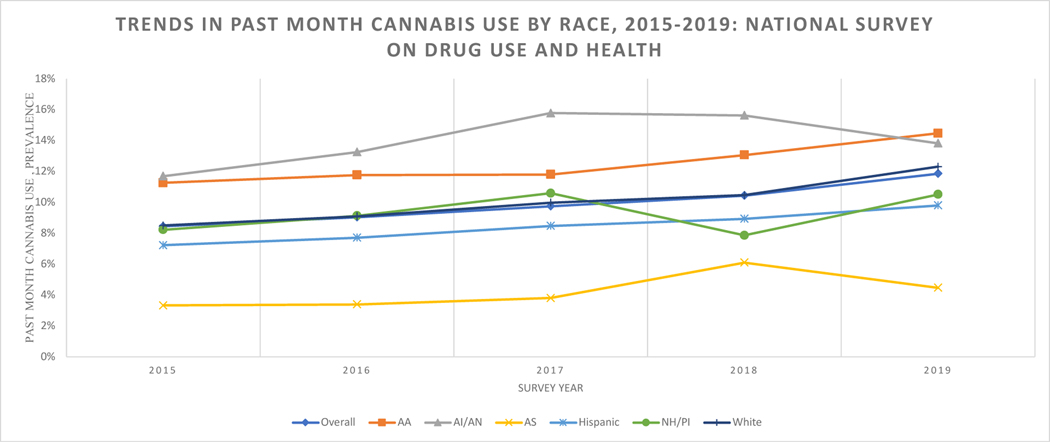

As noted in Figure 1, there has been a steady increase in the prevalence of past month cannabis use among U.S. adults from 2015 (8.45%) to 2019 (11.86%). Pooled data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), an annual nationwide survey of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drug use and mental health among U.S. individuals ages 12 or older, also displays significant racial/ethnic differences in current cannabis use. Specifically, the rates of past month cannabis use among Asian Americans are much lower than the national average, while the rates are slightly higher among White, Hispanic and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander populations. The highest rates of past month cannabis use are seen among American Indian/Alaska Native individuals, followed by African American/Blacks. Although current marijuana use has been consistently high over time among American Indian/Alaska Native individuals, there was a significant decrease in prevalence from 2018 (15.64%) to 2019 (13.83%). This same time period was marked with an increase among African American adults (13.07% to 14.47%). These racial/ethnic differences should continue to be monitored over time, as critical observations about use will inform the appropriate populations to target in cannabis prevention and treatment interventions and policies.

Figure 1.

Trends in the past month of cannabis use.

Note. AA = African American/Black, AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native, AS = Asian, NH/PI = Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

Cannabis Research among African Americans/Blacks

Despite the limited availability of literature on cannabis use and CUD overall among racial/ethnic minorities, most existing studies focus on findings among African American/Black individuals. Several recent studies have found an increased use of cannabis among African American/Black people relative to their White counterparts [13, 14, 15, 16, 17], especially among adolescents [18, 19] and young adults [20, 21, 22, 23]. The increased use of cannabis and CUD was also observed among patients with mental and physical health conditions, such as conduct disorder [24], psychosis [25], epilepsy [26, 27], irritable bowel syndrome [28], and congestive heart failure [29]. The higher rates of cannabis use relative to other racial/ethnic groups (except for American Indian/Alaska Natives) found overall and in these subpopulations are fairly consistent with that of national surveillance data, as shown in Figure 1.

Studies have also shown that cannabis use among African Americans/Black individuals is linked to other drug use, especially among those who live in urban areas [30, 31]. The literature has primarily focused on two patterns of dual use among African American/Black people, showing heavy rates of cannabis and tobacco co-use [32, 33, 34, 35, 36; 37, 38] and cannabis and alcohol co-use [39, 40, 41, 42] relative to other racial/ethnic groups. For example, in a national study of pregnant women, African American/Black women were at an increased odds of using cannabis and tobacco relative to tobacco only [32]. Moreover, in another national examination of alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use among adolescents [40], findings revealed that African American/Black adolescents were more likely than their White peers to co-use cannabis and alcohol. A recent study also found that cannabis use increased the likelihood of gambling among African American/Black males [43].

Racial/ethnic differences have also been shown in ways in which African American/Black individuals use and purchase cannabis. For example, in a sample of young adult cannabis users in Los Angeles [44], African American/Blacks reported significantly greater hits per day of cannabis compared to their White counterparts. A growing body of literature also suggests that African American/Black cannabis smokers are more likely to consume their cannabis through blunts (hollowed out little cigars or cigarillos that are filled with cannabis] than other racial/ethnic groups [45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50]. Further, recent studies have also found that African American/Black individuals spend more money on their cannabis and use different types of cannabis products (e.g., edibles, bongs, dabs) relative to their White peers [51, 52], and highlighted an increase in cannabis-associated emergency department visits among African American/Blacks [53]. Unfortunately, disparities are also observed in the enforcement of cannabis use and possession laws in the African American/Black community, with more sales and possession charges [54, 55] and arrest rates [6, 56], even in cases where the rates of cannabis use/possession are similar to or less than that of their White counterparts.

Some studies have also identified individual and social factors that are associated with cannabis use and cannabis-related problems among African American/Black individuals, such as anxiety sensitivity [57], motives for cannabis use (i.e., depressive symptomatology) [58], age and emotion regulation (i.e., adolescent age and ability to regulate emotions were associated with abstinence from cannabis initiation) [59], peer pressure [60], and living in a disadvantaged community [61]. Attitudes towards cannabis use [62, 63, 64] and gender [65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73] also have a major impact on cannabis use outcomes among African Americans/Blacks, with gender differences observed within the African American/Black community and specific race by gender interactions found. For instance, one recent study found that among 1,173 African American/Black adult cigarette smokers, cannabis use was associated with an increased odds of menthol cigarette use among women, but a decreased odds of menthol cigarette use among men [70]. Another study using national data indicated that African American/Black men had higher prevalence of lifetime cannabis use and past year cannabis initiation than White men, but this pattern was not found among women [68].

Several studies also discuss the role of racial discrimination [74, 75] and race-related stress [76] and cannabis use. However, recent studies have shown that a strong racial identity serves as a protective factor against the increased frequency of cannabis use [77, 78, 79].

Cannabis Research among American Indian/Alaska Natives

American Indians/Alaska Natives have increased risk for early cannabis use initiation [80, 81, 82]. Frequency of use has been found to peak between the ages of 11 and 14, [83, 84], with males endorsing higher rates of use [85, 82]. Positive peer attitudes towards cannabis, association with antisocial peers (including gang affiliation), and familial substance use are risk factors for lifetime use [85, 86, 87, 88], whereas familial disapproval of substance use, strong cultural identity, and perceived risk to others serve as protective factors [89, 87, 90]. Strong community ties also decrease the likelihood of lifetime cannabis use [91]. Coping as a motivating factor for use is associated with cannabis use among this population [92]; these findings are supported by literature noting that exposure to stressful life events increases the likelihood of use [93]. Those engaging in polysubstance use (e.g., tobacco, alcohol) also have increased risk for cannabis use [82, 84, 94].

Cannabis Research among Asian Americans

The literature notes lower rates of cannabis use among Asian Americans when compared to other racial/ethnic groups [95, 96, 97], however, multiple correlates for use were identified. Mental health challenges including anxiety, suicidal ideation, and attempting suicide are associated with cannabis use among Asian Americans [98, 99]. In a sample investigating use among 3,744 individuals receiving outpatient treatment for Schizophrenia, using cannabis increased the odds of exhibiting aggressive behavior, delusions, and treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications [100]. Environmental stressors such as food insecurity, being bullied or physically assaulted, and having low-income also increased the odds of lifetime cannabis use [98, 12]. Males and young adults consistently demonstrate higher rates of use [95, 100, 12, 101]. Asian-American adults also have lower rates of treatment utilization for cannabis dependence compared to White adults [12].

Cannabis Research among Hispanic/Latinos

Gender is a significant predictor of cannabis use among Latinx individuals, with males demonstrating higher rates of use [102, 103, 104]. However, female trauma survivors are more likely to endorse lifetime cannabis use, relative to males who endorsed experiencing trauma [105]. Polysubstance use is associated with increased risk for cannabis use among Latinx populations, with tobacco [106, 46], alcohol [107, 105, 47, 48], and illicit substances [48] being commonly used with cannabis among Latinx people. Additionally, depressive symptomatology has also been linked to cannabis use within this population [108; 109; 48]. In a study investigating acculturation and substance use among 1,494, Latinx adults (i.e., 18 and older), high levels of acculturation were found to be associated with decreased likelihood of reporting lifetime cannabis use [103]. Research investigating the relationship between school-based ethnic discrimination and marijuana use among Latinx adolescents found that youth with substance-using peers were more likely to have favorable marijuana attitudes and increased likelihood for past-month use [108]. Familial relationships are also associated with cannabis use, with Latinx youth who report not receiving homework assistance or encouragement from parents being more likely to endorse current and lifetime use [110]; those who report negative father-figure interactions are more likely to initiate cannabis use early [111].

Cannabis Research among Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders

The literature demonstrated limited findings of cannabis use among Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander individuals. However, one study revealed that current cannabis use was associated with increased likelihood of lifetime e-cigarette use among individuals 18–30 years of age[112].

Conclusions: Implications for Cannabis Researchers

Findings from this review clearly indicate the need for further cannabis research among racial/ethnic minority populations, especially among Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders. Only one recent study was found and its major focus was on e-cigarettes. The lack of cannabis research among Native Hawaaiian/Pacific Islanders is problematic given the high prevalence of cannabis use that has been previously observed in older studies. For instance, the prevalence of past year cannabis use was 18.8% in 2011 among Native Hawaaiian/Pacific Islanders, which was significantly higher than that of Whites (11.8% in 2011) and Asian-Americans (4.9% in 2011) [113]. Due to small sample sizes, Native Hawaaiian/Pacific Islanders (and Asian-Americans) are often combined in an “Other” category in health studies, therefore limiting the conclusions that can be drawn for this population. Future research should specifically focus on risk and protective factors and effective treatments for Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, as well as all other racial/ethnic groups.

Second, examining racial/ethnic differences in cannabis use is important, but use of this approach alone ignores heterogeneity within groups. As discussed in literature on best practices for studying race/ethnicity in addiction [114], research examining racial/ethnic differences provides an understanding of how minority populations differ from each other and the majority population, but it provides limited insight into factors that specifically impact the initiation, maintenance, prevention and treatment of cannabis use in a specific group. One positive observation from the limited number of studies in this review is that several of the articles highlight risk and protective factors that are unique to each racial/ethnic group, such as strong cultural identity among American Indian/Alaska Natives [89] and environmental stressors among Asian Americans [12]. Moreover, important gender differences that were observed within certain racial/ethnic groups would have been overlooked if the studies employed a race comparison design [68, 70]. Identifying unique risk and protective factors to target in interventions and policies for each racial/ethnic minority group is an important step in reducing cannabis-related health disparities.

Third, although limited, most of the existing literature on cannabis and race focuses on African American/Black individuals. Many studies demonstrate higher rates of cannabis use and CUD and greater rates of legal and social consequences [13, 54], which may at least partially explain why more research has been conducted among this racial group. Given that the greatest amount of literature focuses on African Americans/Blacks, the next set of recommendations will be guided from research on this population. First, one of the most important observations from this body of research is the need to focus on methods of cannabis consumption in cannabis research. Several studies have highlighted an increased use of cannabis among African American/Black individuals [14, 15], but a detailed assessment of consumption methods revealed that the majority of African American/Black cannabis users consume cannabis through blunts [45, 46, 47]. This revelation has informed a growing body of research on blunt use, helping to expand our understanding of cannabis use among certain subgroups with high prevalence, such as males, young adults and African American/Black individuals [115]. Further, although joints and blunts are both combustible forms of cannabis use, a recent study found that blunt smokers present to treatment with greater amounts of cannabis smoked and more intense withdrawal symptoms than joint smokers [116]. These types of studies help to provide insights into methods that are commonly used by certain groups and can provide deeper insights into cannabis-related issues among racial/ethnic minorities, such as increased prevalence and cannabis-related problems.

Another important emerging area of research in this area is on cannabis risk and protective factors related to race. Studies have clearly indicated a strong association between racial discrimination and cannabis use [74, 75, 76]. For example, African American/Black men who experienced major discrimination (e.g., unfairly fired, unfairly treated/abused by police, denied loan) had a higher odds of cannabis use [74]. Everyday discrimination (e.g., being treated with less respect than others, being treated as if they are not smart by others, being called names or insulted by others) was not associated with cannabis use among African American/Black men [74]. Studies that assess the impact of discrimination would be beneficial to conduct among all racial/ethnic minority groups, as some racial/ethnic minorities may use cannabis to cope with structural inequalities. There is a growing recognition of the importance of discrimination and structural racism and its role in poor health outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities, with major funding agencies calling for research in this area (e.g., National Institutes of Health’s Funding Opportunity (RFA-MD-21–004): Understanding and Addressing the Impact of Structural Racism and Discrimination on Minority Health and Health Disparities).

Lastly, there are a few areas in the field that warrant additional attention in the literature on racial/ethnic minorities. One important topic is that of identifying and strengthening protective factors that prevent or decrease the frequency of cannabis use, such as spirituality, strong racial identity and familiar disapproval of substance use, among racial/ethnic minorities. Another important area is the co-use of cannabis with both tobacco and alcohol among racial/ethnic minorities [32, 33, 39, 40], as some studies have demonstrated an increase in these patterns of use that exceed the prevalence of cannabis use alone. The increased rates of co-use are problematic; for instance, cannabis and tobacco co-use has been associated with heavier rates of cannabis use, tobacco use and greater problematic behaviors (i.e., selling cannabis, driving a car after using cannabis] relative to the single use of cannabis and tobacco [117]. Lastly, a significant gap in the literature is in the absence of studies assessing the prevalence and correlates of medical cannabis use among racial/ethnic groups [118]. As cannabis legalization evolves, it is important to ensure that existing health inequities are not widened by cannabis-related strategies and laws that harm understudied and underserved populations, such as racial/ethnic minorities. Overall, this review emphasizes the need to monitor cannabis use and CUD and identify culturally appropriate strategies for prevention, treatment and policy interventions for racial/ethnic minorities.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This AM is a PDF file of the manuscript accepted for publication after peer review, when applicable, but does not reflect post-acceptance improvements, or any corrections. Use of this AM is subject to the publisher’s embargo period and AM terms of use. Under no circumstances may this AM be shared or distributed under a Creative Commons or other form of open access license, nor may it be reformatted or enhanced, whether by the Author or third parties. See here for Springer Nature’s terms of use for AM versions of subscription articles: https://www.springernature.com/gp/open-research/policies/accepted-manuscript-terms

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020 Sep 11 [cited 2021 12 June]. Available from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-annual-national-report [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). What is marijuana? [Internet]. National Institute of Health; 2021. Apr 13 [cited 2021 Jun 9]. Available from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana/what-marijuana [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marconi A, Di Forti M, Lewis CM, Murray RM, Vassos E. Meta-analysis of the association between the level of cannabis use and risk of psychosis. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2016. Sep 1;42(5):1262–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance use and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Know the risks of marijuana [Internet]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Dec 16 [cited 2021 Jun 10]. Available from https://www.samhsa.gov/marijuana [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foster KT, Arterberry BJ, Iacono WG, McGue M, Hicks BM. Psychosocial functioning among regular cannabis users with and without cannabis use disorder. Psychological medicine. 2018. Aug;48(11):1853. The relationship between psychosocial impairment between cannabis use and cannabis use disorder (CUD) was investigated in this study. Findings suggest that any cannabis use is associated with increased risk for impairment. Cannabis users diagnosed with CUD demonstrated higher prevalence of comorbid psychosocial impairment and psychiatric symptoms.

- 6.Firth CL, Maher JE, Dilley JA, Darnell A, Lovrich NP. Did marijuana legalization in Washington State reduce racial disparities in adult marijuana arrests?. Substance use & misuse. 2019. Jul 29;54(9):1582–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Sarvet AL. Time trends in US cannabis use and cannabis use disorders overall and by sociodemographic subgroups: a narrative review and new findings. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2019. Nov 2;45(6):623–43. This relevant study examined the comorbidity of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder (CUD) in the U.S. using time trends. Results suggest that rates of use and new cases of CUD increased across multiple socio-demographic groups.

- 8.Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Pickering R, Grant BF. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychological medicine. 2006. Oct;36(10):1447–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu H, Wu LT. Trends and correlates of cannabis-involved emergency department visits: 2004 to 2011. Journal of addiction medicine. 2016. Nov;10(6):429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McElrath K, Taylor A, Tran KK. Black–White disparities in criminal justice referrals to drug treatment: addressing treatment need or expanding the diagnostic net?. Behavioral Sciences. 2016. Dec;6(4):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montgomery L, Robinson C, Seaman EL, Haeny AM. A scoping review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for cannabis and tobacco use among African Americans. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2017. Dec;31(8):922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu LT, Zhu H, Mannelli P, Swartz MS. Prevalence and correlates of treatment utilization among adults with cannabis use disorder in the United States. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2017. Aug 1;177:153–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Yu B, Lasopa SO, Cottler LB. Current patterns of marijuana use initiation by age among US adolescents and emerging adults: implications for intervention. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2017. May 4;43(3):261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton AD, Jang JB, Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Keyes KM. Age, period and cohort effects in frequent cannabis use among US students: 1991–2018. Addiction. 2019. Oct;114(10):1763–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John WS, Wu LT. Problem alcohol use and healthcare utilization among persons with cannabis use disorder in the United States. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2017. Sep 1;178:477–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mitchell W, Bhatia R, Zebardast N. Retrospective cross-sectional analysis of the changes in marijuana use in the USA, 2005–2018. BMJ open. 2020. Jul 1;10(7):e037905. This is an important trend analysis study examining change rates of cannabis use from 2005–2018 among adults. The results indicate that past-year cannabis use increased significantly over time, with non-Hispanic African Americans demonstrating higher prevalence rates.

- 17.Poghosyan H, Poghosyan A. Marijuana use among cancer survivors: Quantifying prevalence and identifying predictors. Addictive Behaviors. 2021. Jan 1;112:106634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aranmolate R. Marijuana use among youths in Mississippi, United States. International journal of adolescent medicine and health. 2020. Aug 1;32(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miech R, Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Increasing marijuana use for black adolescents in the United States: A test of competing explanations. Addictive behaviors. 2019. Jun 1;93:59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keyes KM, Wall M, Feng T, Cerdá M, Hasin DS. Race/ethnicity and marijuana use in the United States: Diminishing differences in the prevalence of use, 2006–2015. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2017. Oct 1;179:379–86. This is an important trend analysis study examining trends over time in past 30-day cannabis use among adolescents in the Monitoring the Future Survey (2006–2015). The results indicate that Black students had a positive linear increase in cannabis use, while the magnitude of the increase for Hispanic students was greater for those in urban areas and in large class sizes.

- 21.Richter L, Pugh BS, Ball SA. Assessing the risk of marijuana use disorder among adolescents and adults who use marijuana. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2017. May 4;43(3):247–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reboussin BA, Ialongo NS, Green KM, Furr-Holden DM, Johnson RM, Milam AJ. The impact of the urban neighborhood environment on marijuana trajectories during emerging adulthood. Prevention science. 2019. Feb;20(2):270–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu H, Wu LT. Sex differences in cannabis use disorder diagnosis involved hospitalizations in the United States. Journal of addiction medicine. 2017. Sep;11(5):357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masroor A, Patel RS, Bhimanadham NN, Raveendran S, Ahmad N, Queeneth U, et al. Conduct disorder-related hospitalization and substance use disorders in American teens. Behavioral Sciences. 2019. Jul;9(7):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel RS, Sreeram V, Vadukapuram R, Baweja R. Do cannabis use disorders increase medication non-compliance in schizophrenia?: United States Nationwide inpatient crosssectional study. Schizophrenia Research. 2020. Oct 1;224:40–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lekoubou A, Fox J, Bishu KG, & Ovbiagele B. (2020). Trends in documented cannabis use disorder among hospitalized adult epilepsy patients in the United States. Epilepsy research, 163, 106341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel RS, Mekala HM, Tankersley WE. Cannabis Use Disorder and Epilepsy: A Cross-National Analysis of 657 072 Hospitalized Patients. The American journal on addictions. 2019. Sep;28(5):353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel RS, Goyal H, Satodiya R, Tankersley WE. Relationship of cannabis use disorder and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): An analysis of 6.8 million hospitalizations in the United States. Substance use & misuse. 2020. Jan 1;55(2):281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajibawo T, Ajibawo-Aganbi U, Jean-Louis F, Patel RS. Congestive heart failure hospitalizations and cannabis use disorder (2010–2014): national trends and outcomes. Cureus. 2020. Jul;12(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reboussin BA, Rabinowitz JA, Thrul J, Maher B, Green KM, Ialongo NS. Trajectories of cannabis use and risk for opioid misuse in a young adult urban cohort. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2020. Oct 1;215:108182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thrul J, Rabinowitz JA, Reboussin BA, Maher BS, Ialongo NS. Adolescent cannabis and tobacco use are associated with opioid use in young adulthood—12-year longitudinal study in an urban cohort. Addiction. 2021. Mar;116(3):643–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman-Cowger VH, Schauer GL, Peters EN. Marijuana and tobacco co-use among a nationally representative sample of US pregnant and non-pregnant women: 2005–2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health findings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017. Aug 1;177:130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilreath TD, Dangerfield DT, Ishino FA, Hill AV, Johnson RM. Polytobacco use among a nationally-representative sample of black high school students. BMC public health. 2021. Dec;21(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery L, Schiavon S, Cropsey K. Factors associated with marijuana use among treatment-seeking adult cigarette smokers in the criminal justice population. Journal of addiction medicine. 2019. Mar;13(2):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubenstein D, Aston ER, Nollen NL, Mayo MS, Brown AR, Ahluwalia JS. Factors associated with cannabis use among African American nondaily smokers. Journal of addiction medicine. 2020. Sep 1;14(5):e170–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seaman EL, Green KM, Wang MQ, Quinn SC, Fryer CS. Examining prevalence and correlates of cigarette and marijuana co-use among young adults using ten years of NHANES data. Addictive behaviors. 2019. Sep 1;96:140–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uddin SI, Osei AD, Obisesan OH, El-Shahawy O, Dzaye O, Cainzos-Achirica M, et al. Prevalence, trends, and distribution of nicotine and marijuana use in E-cigarettes among US adults: the behavioral risk factor surveillance system 2016–2018. Preventive Medicine. 2020. Oct 1;139:106175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young-Wolff KC, Adams SR, Sterling SA, Tan AS, Salloum RG, Torre K, et al. Nicotine and cannabis vaping among adolescents in treatment for substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021. Jun 1;125:108304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banks DE, Bello MS, Crichlow Q, Leventhal AM, Barnes-Najor JV, Zapolski TC. Differential typologies of current substance use among Black and White high-school adolescents: A latent class analysis. Addictive behaviors. 2020. Jul 1;106:106356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banks DE, Rowe AT, Mpofu P, Zapolski TC. Trends in typologies of concurrent alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use among US adolescents: An ecological examination by sex and race/ethnicity. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2017. Oct 1;179:71–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipira L, Rao D, Nevin PE, Kemp CG, Cohn SE, Turan JM, et al. Patterns of alcohol use and associated characteristics and HIV-related outcomes among a sample of African-American women living with HIV. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2020. Jan 1;206:107753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montgomery L, Zapolski T, Banks DE, Floyd A. Puff, puff, drink: The association between blunt and alcohol use among African American adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(5):609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Werner KB, Cunningham-Williams RM, Ahuja M, Bucholz KK. Patterns of gambling and substance use initiation in African American and White adolescents and young adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2020. Mar;34(2):382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lankenau SE, Tabb LP, Kioumarsi A, Ataiants J, Iverson E, Wong CF. Density of medical marijuana dispensaries and current marijuana use among young adult marijuana users in Los Angeles. Substance use & misuse. 2019. Sep 19;54(11):1862–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eggers ME, Lee YO, Jackson K, Wiley JL, Porter L, Nonnemaker JM. Youth use of electronic vapor products and blunts for administering cannabis. Addictive Behaviors. 2017. Jul 1;70:79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montgomery L, Mantey DS, Peters EN, Herrmann ES, Winhusen T. Blunt use and menthol cigarette smoking: An examination of adult marijuana users. Addictive behaviors. 2020. Mar 1;102:106153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montgomery L, Mantey DS. Correlates of blunt smoking among African American, Hispanic/Latino, and white adults: Results from the 2014 national survey on drug use and health. Substance use & misuse. 2017. Sep 19;52(11):1449–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montgomery L, Mantey D. Racial/ethnic differences in prevalence and correlates of blunt smoking among adolescents. Journal of psychoactive drugs. 2018. May 27;50(3):195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montgomery L, Ramo D. What did you expect?: The interaction between cigarette and blunt vs. non-blunt marijuana use among African American young adults. Journal of substance use. 2017. Nov 2;22(6):612–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Streck JM, Hughes JR, Klemperer EM, Howard AB, Budney AJ. Modes of cannabis use: A secondary analysis of an intensive longitudinal natural history study. Addictive behaviors. 2019. Nov 1;98:106033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D’Amico EJ, Rodriguez A, Dunbar MS, Firth CL, Tucker JS, Seelam R, Pedersen ER, Davis JP. Sources of cannabis among young adults and associations with cannabis-related outcomes. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020. Dec 1;86:102971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montgomery L, Heidelburg K, Robinson C. Characterizing blunt use among twitter users: racial/ethnic differences in use patterns and characteristics. Substance use & misuse. 2018. Feb 23;53(3):501–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim PC, Yoo JW, Cochran CR, Park SM, Chun S, Lee YJ, et al. Trends and associated factors of use of opioid, heroin, and cannabis among patients for emergency department visits in Nevada: 2009–2017. Medicine. 2019. Nov;98(47). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenberg A, Groves AK, Blankenship KM. Comparing Black and White drug offenders: Implications for racial disparities in criminal justice and reentry policy and programming. Journal of drug issues. 2017. Jan;47(1):132–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tran NK, Goldstein ND, Purtle J, Massey PM, Lankenau SE, Suder JS, Tabb LP. The heterogeneous effect of marijuana decriminalization policy on arrest rates in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2009–2018. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2020. Jul 1;212:108058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Owusu-Bempah A, Luscombe A. Race, cannabis and the Canadian war on drugs: an examination of cannabis arrest data by race in five cities. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2021. May 1;91:102937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dean KE, Ecker AH, Buckner JD. Anxiety sensitivity and cannabis use-related problems: The impact of race. The American journal on addictions. 2017. Apr;26(3):209–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.King VL, Mrug S, Windle M. Predictors of motives for marijuana use in African American adolescents and emerging adults. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2020. Apr 16:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kliewer W, Parham B. Resilience against marijuana use initiation in low-income African American youth. Addictive Behaviors. 2019. Feb 1;89:236–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jelsma E, Varner F. African American adolescent substance use: The roles of racial discrimination and peer pressure. Addictive behaviors. 2020. Feb 1;101:106154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kogan SM, Cho J, Brody GH, Beach SR. Pathways linking marijuana use to substance use problems among emerging adults: A prospective analysis of young Black men. Addictive behaviors. 2017. Sep 1;72:86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Braymiller JL, Masters LD, Linden-Carmichael AN, Lanza ST. Contemporary Patterns of Marijuana Use and Attitudes Among High School Seniors: 2010–2016. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2018. Oct 1;63(4):394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Javier SJ, Abrams JA, Moore MP, Belgrave FZ. Change in risk perceptions and marijuana and cigarette use among African American young adult females in an HIV prevention intervention. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2017. Dec;4(6):1083–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Patrick ME, Miech RA. Risk is still relevant: Time-varying associations between perceived risk and marijuana use among US 12th grade students from 1991 to 2016. Addictive behaviors. 2017. Nov 1;74:13–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Assari S, Mistry R, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. Marijuana use and depressive symptoms; gender differences in African American adolescents. Frontiers in psychology. 2018. Nov 16;9:2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.King KA, Fuqua SH, Vidourek RA, Merianos AL, Yockey RA. Does marijuana use among African American adolescent males differ based on school factors?. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse. 2020. Sep 29:1–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Floyd LJ. Perceived neighborhood disorder and frequency of marijuana use among emerging adult African American females. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse. 2020. Jul 19:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Forman-Hoffman VL, Glasheen C, Batts KR. Marijuana use, recent marijuana initiation, and progression to marijuana use disorder among young male and female adolescents aged 12–14 living in US households. Substance abuse: research and treatment. 2017. Jun 1;11:1178221817711159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foster DW, Ye F, Chung T, Hipwell AE, Sartor CE. Longitudinal associations between marijuana-related cognitions and marijuana use in African-American and European-American girls from early to late adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2018. Feb;32(1):104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Montgomery L, Webb Hooper M. Gender Differences in the Association between Marijuana and Menthol Cigarette Use among African American Adult Cigarette Smokers. Substance use & misuse. 2020. May 1;55(8):1335–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oh S, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Zapcic I. Substance misuse profiles of women in families receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits: findings from a national sample. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2020. Nov;81(6):798–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oser CB, Harp K, Pullen E, Bunting AM, Stevens-Watkins D, Staton M. African–American Women’s Tobacco and Marijuana Use: The Effects of Social Context and Substance Use Perceptions. Substance use & misuse. 2019. May 12;54(6):873–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sartor CE, Hipwell AE, Chung T. Alcohol or marijuana first? correlates and associations with frequency of use at age 17 among black and white girls. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2019. Jan;80(1):120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parker LJ, Benjamin T, Archibald P, Thorpe RJ. The association between marijuana usage and discrimination among adult Black men. American journal of men’s health. 2017. Mar;11(2):435–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zapolski TC, Yu T, Brody GH, Banks DE, Barton AW. Why now? Examining antecedents for substance use initiation among African American adolescents. Development and psychopathology. 2020. May;32(2):719–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dogan JN, Thrasher S, Thorpe SY, Hargons C, Stevens-Watkins D. Cultural race-related stress and cannabis use among incarcerated African American men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2021. Feb 8; 35(3):320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arsenault CE, Fisher S, Stevens-Watkins D, Barnes-Najor J. The indirect effect of ethnic identity on marijuana use through school engagement: An African American high school sample. Substance Use & Misuse. 2018. Jul 29;53(9):1444–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Banks DE, Clifton RL, Wheeler PB. Racial identity, discrimination, and polysubstance use: Examining culturally relevant correlates of substance use profiles among Black young adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2020. Dec 28; 35(2), 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pahl K, Capasso A, Lekas HM, Lee JY, Winters J, Pérez-Figueroa RE. Longitudinal predictors of male sexual partner risk among Black and Latina women in their late thirties: ethnic/racial identity commitment as a protective factor. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2021. Apr;44(2):202–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stanley LR, Swaim RC, Smith JK, Conner BT. Early onset of cannabis use and alcohol intoxication predicts prescription drug misuse in American Indian and non-American Indian adolescents living on or near reservations. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2020. Jul 3;46(4):447–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Copeland WE, Hill S, Costello EJ, Shanahan L. Cannabis use and disorder from childhood to adulthood in a longitudinal community sample with American Indians. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017. Feb 1;56(2):124–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cwik MF, Rosenstock S, Tingey L, Goklish N, Larzelere F, Suttle R, et al. Characteristics of substance use and self-injury among American Indian adolescents who have engaged in binge drinking. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2018. Jun 1;25(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Swaim RC, Stanley LR. Self-esteem, cultural identification, and substance use among American Indian youth. Journal of community psychology. 2019. Sep;47(7):1700–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hautala D, Sittner K, Walls M. Onset, comorbidity, and predictors of nicotine, alcohol, and marijuana use disorders among North American Indigenous adolescents. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2019. Jun;47(6):1025–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ayers S, Jager J, Kulis SS. Variations in risk and promotive factors on substance use among urban American Indian youth. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse. 2019. May 10;20(2):187–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Swaim RC, Stanley LR. Predictors of Substance Use Latent Classes Among American Indian Youth Attending Schools On or Near Reservations. The American journal on addictions. 2020. Jan;29(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stanley LR, Swaim RC, Dieterich SE. The role of norms in marijuana use among American Indian adolescents. Prevention Science. 2017. May 1;18(4):406–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fox LP, Moore TM. Exploring Changes in Gang Involvement and Associated Risk Factors for American Indian Adolescents in Reservation Communities. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2021. Jan 1;28(1): 17–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Unger JB, Sussman S, Begay C, Moerner L, Soto C. Spirituality, ethnic identity, and substance use among American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents in California. Substance use & misuse. 2020. Apr 15;55(7):1194–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nalven T, Schick MR, Spillane NS, Quaresma SL. Marijuana use and intentions among American Indian adolescents: Perceived risks, benefits, and peer use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2021. Feb 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kelley A, Witzel M, Fatupaito B. Preventing Substance Use in American Indian Youth: The Case for Social Support and Community Connections. Substance use & misuse. 2019. Apr 16;54(5):787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Davis SR, Prince MA, Swaim RC, Stanley LR. Comparing cannabis use motive item performance between American Indian and White youth. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2020. Aug 1;213:108086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eitle D, Thorsen M, Eitle TM. School context and American Indian substance use. The Social science journal. 2017. Dec 1;54(4):420–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kiedrowski L. Patterns of Polysubstance Use Among Non-Hispanic White and American Indian/Alaska Native Adolescents: An Exploratory Analysis. Preventing chronic disease. 2019;16(E40): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tucker JS, Rodriguez A, Dunbar MS, Pedersen ER, Davis JP, Shih RA, et al. Cannabis and tobacco use and co-use: trajectories and correlates from early adolescence to emerging adulthood. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2019. Nov 1;204:107499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hamilton HA, Owusu-Bempah A, Boak A, Mann RE. Ethnoracial differences in cannabis use among native-born and foreign-born high school students in Ontario. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse. 2018. Apr 3;17(2):123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bersamin M, Paschall MJ, Fisher DA. School-based health centers and adolescent substance use: moderating effects of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Journal of school health. 2017. Nov;87(11):850–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Cannabis and amphetamine use among adolescents in five Asian countries. Central Asian journal of global health. 2017;6(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Suicide attempt and associated factors among adolescents in five Southeast Asian countries in 2015. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 2020. Jan 10; 4(4):296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Park SC, Oh HS, Tripathi A, Kallivayalil RA, Avasthi A, Grover S, et al. Cannabis use correlates with aggressive behavior and long-acting injectable antipsychotic treatment in Asian patients with schizophrenia. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2019. Aug 18;73(6):323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Williams L, Ralphs R, Gray P. The normalization of cannabis use among Bangladeshi and Pakistani youth: A new frontier for the normalization thesis?. Substance Use & Misuse. 2017. Mar 21;52(4):413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gattamorta KA, Mena MP, Ainsley JB, Santisteban DA. The comorbidity of psychiatric and substance use disorders among Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2017. Oct 2;13(4):254–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mercado A, Ramirez M, Sharma R, Popan J, Avalos Latorre ML. Acculturation and substance use in a Mexican American college student sample. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse. 2017. Jul 3;16(3):276–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vaughan EL, Wright LA, Cano MÁ, de Dios MA. Gender as a moderator of descriptive norms and substance use among Latino college students. Substance Use & Misuse. 2018. Sep 19;53(11):1840–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hoskins D, Marshall BD, Koinis-Mitchell D, Galbraith K, Tolou-Shams M. Latinx youth in first contact with the justice system: trauma and associated behavioral health needs. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2019. Jun;50(3):459–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lozano P, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Arillo-Santillan E, Morello P, Mejia R, Sargent JD, et al. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use and onset of conventional cigarette smoking and marijuana use among Mexican adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017. Nov 1;180:427–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gonzalez PD, Vaughan EL. Substance use among Latino international and domestic college students. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2020. Apr 2:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bakhtiari F, Boyle AE, Benner AD. Pathways Linking School-Based Ethnic Discrimination to Latino/a Adolescents’ Marijuana Approval and Use. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2020. Dec;22:1273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hill CM, Williams EC, Ornelas IJ. Help wanted: mental health and social stressors among Latino day laborers. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2019. Mar;13(2):1557988319838424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Merianos AL, King KA, Vidourek RA, Becker KJ, Yockey RA. Authoritative Parenting Behaviors and Marijuana Use Based on Age Among a National Sample of Hispanic Adolescents. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2020. Feb;41(1):51–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Moreno O, Janssen T, Cox MJ, Colby S, Jackson KM. Parent-adolescent relationships in Hispanic versus Caucasian families: associations with alcohol and marijuana use onset. Addictive Behaviors. 2017. Nov 1;74:74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Subica AM, Guerrero E, Wu LT, Aitaoto N, Iwamoto D, Moss HB. Electronic Cigarette Use and Associated Risk Factors in US-Dwelling Pacific Islander Young Adults. Substance use & Misuse. 2020. Jul 1;55(10):1702–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu LT, Blazer DG, Swartz MS, Burchett B, Brady KT, Workgroup NA. Illicit and nonmedical drug use among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, and mixedrace individuals. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013. Dec 1;133(2):360–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Burlew AK, Peteet BJ, McCuistian C, Miller-Roenigk BD. Best practices for researching diverse groups. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(3):354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schauer GL, Rosenberry ZR, Peters EN. Marijuana and tobacco co-administration in blunts, spliffs, and mulled cigarettes: A systematic literature review. Addictive Behaviors. 2017. Jan 1;64:200–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Montgomery L, McClure EA, Tomko RL, Sonne SC, Winhusen T, Terry GE, et al. Blunts versus joints: Cannabis use characteristics and consequences among treatment-seeking adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019. May 1;198:105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tucker JS, Pedersen ER, Seelam R, Dunbar MS, Shih RA, D’Amico EJ. Types of cannabis and tobacco/nicotine co-use and associated outcomes in young adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2019. Jun;33(4):401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Valencia CI, Asaolu IO, Ehiri JE, Rosales C. Structural barriers in access to medical marijuana in the USA--A sysematic review. Systematic Review. 2017. August 7: 6: 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]