Summary

To date, there has been no multi-omic analysis characterizing the intricate relationships between the intragastric microbiome and gastric mucosal gene expression in gastric carcinogenesis. Using multi-omic approaches, we provide a comprehensive view of the connections between the microbiome and host gene expression in distinct stages of gastric carcinogenesis (i.e., healthy, gastritis, cancer). Our integrative analysis uncovers various associations specific to disease states. For example, uniquely in gastritis, Helicobacteraceae is highly correlated with the expression of FAM3D, which has been previously implicated in gastrointestinal inflammation. In addition, in gastric cancer but not in adjacent gastritis, Lachnospiraceae is highly correlated with the expression of UBD, which regulates mitosis and cell cycle time. Furthermore, lower abundances of B cell signatures in gastric cancer compared to gastritis may suggest a previously unidentified immune evasion process in gastric carcinogenesis. Our study provides the most comprehensive description of microbial, host transcriptomic, and immune cell factors of the gastric carcinogenesis pathway.

Subject areas: Cellular physiology, Microbiome, Omics

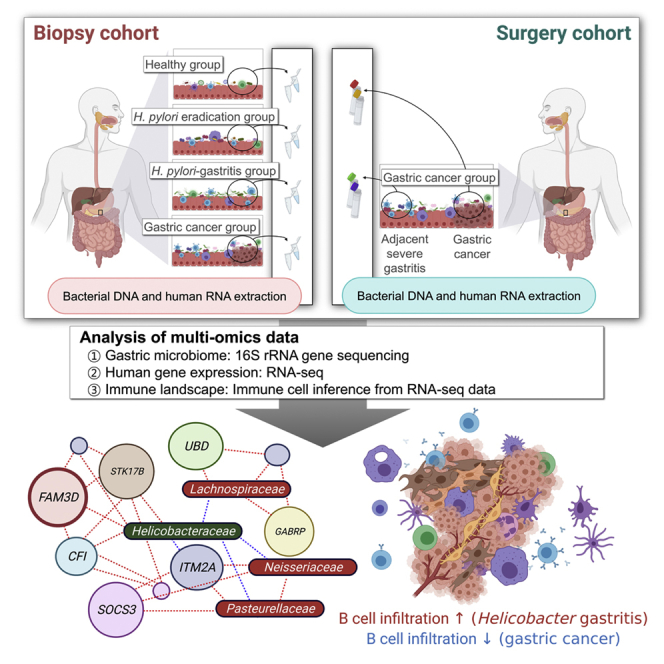

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Multi-omics finds genetic, microbial, and immunological links in gastric cancer

-

•

Helicobacteraceae was highly associated with the expression of inflammation genes

-

•

Pasteurellaceae and Lachnospiraceae were associated with cancer-related genes

-

•

B cell infiltration was prominent in gastritis tissues but not in gastric cancer

Cellular physiology; Microbiome; Omics

Introduction

Globally, gastric cancer is the fourth and fifth leading cause of cancer death in men and women, respectively, and over one million cases of gastric cancer are diagnosed annually (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020). Gastric cancer typically occurs through the gastric carcinogenesis pathway, which is initiated by chronic Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection and progress to atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric cancer (Correa, 1995). Although HP infection is the strongest risk factor for gastric cancer development (Crew and Neugut, 2006), intragastric bacteria, other than HP may be also involved in gastric carcinogenesis (Sung et al., 2020). In this sense, our previous study showed that the composition of intragastric microbiome and metagenomic functional annotations differed between healthy individuals and patients with intestinal metaplasia (Park et al., 2019). For example, Type IV secretion system protein genes, which are essential for HP to transfer CagA proteins into human epithelial cells, were found to be more abundant in the intragastric microbiome of patients with intestinal metaplasia (Park et al., 2019).

In addition to the intragastric microbiome, host gene expression has been found to differ between different gastric disease states along the gastric carcinogenesis pathway. Differential gene expression analysis of gastric cancer tissue showed that several cancer-related biological pathways, including ‘Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase signaling’ and ‘Cell cycle’, were associated with gastric cancer (Shi et al., 2021). Moreover, HP-associated non-atrophic gastritis was found to be associated with the upregulation of genes related to ‘Immune response’ and ‘Chemokine activity’ pathways (Yin et al., 2020). These pathways are related to chronic gastric inflammation, which may induce precancerous changes in the gastric mucosa (atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia). In addition, atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia were associated with the enrichment of ‘Fat digestion and absorption pathway’ and ‘Metabolic pathway’ (Yin et al., 2020). A better understanding of changes in host gene expression throughout the clinical course of gastric carcinogenesis may help reveal insights into pathogenesis mechanisms and potential treatment targets.

Immune cells comprising the tumor microenvironment have also been of significance in gastric cancer research (Lee et al., 2014). For example, HP infection activates the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor in dendritic cells, which leads to the recruitment and activation of other immune cells, including Th1, Th17, and Treg cells (Salama et al., 2013). In addition, tumor-infiltrating immune cells can contribute to tumor progression, metastasis, and resistance to anticancer treatment (Galon and Bruni, 2019). Further elucidating the role of the immune system in gastric carcinogenesis may lead to improvements in treatment response for immunotherapy, which in recent years has emerged as the standard treatment option for various advanced cancers, including gastric cancer (Lordick et al., 2017).

Although the intragastric microbiome, gastric mucosal gene expression, and immune cells comprising the tumor microenvironment in the stomach have all been independently well studied, integrative analyses identifying associations and potential cross talk between these separate systems have been lacking in the field of gastric cancer research. In this regard, comprehensive analyses utilizing multiple ‘omes’ can provide a broader and more powerful analysis on the interconnectivity of multiple biological data types (Hasin et al., 2017), and ultimately in-depth, systems-level knowledge of human health (Price et al., 2017; Wainberg et al., 2020). Moreover, recent multi-omic studies have provided striking revelations underlying biomolecular mechanisms underlying human diseases (Lee et al., 2021; Lloyd-Price et al., 2019; Su et al., 2020; Tong et al., 2016). Therefore, investigating the relationship between intragastric microbiome and host gene expression, or between intragastric microbiome and immune cell infiltration, across multiple steps of gastric carcinogenesis would represent an innovative strategy for intragastric pathology research.

In this study, we investigated the microbiome, host gene expression, and gastric tissue-infiltrating immune cells in two disease cohorts, which included patients with gastritis and with gastric cancer, and healthy controls. By identifying associations between taxa of the intragastric microbiome and host genes expressed in the gastric mucosa, we propose a strategy for screening high-risk individuals of gastric cancer based on both microbiome and gene expression profiling. In addition, we found strong associations between intragastric bacteria and gene expression signatures of immune cell types. Consequently, we infer significantly fewer immune cells in gastric cancer compared to HP-associated gastritis, which may be associated with potential immune evasion mechanisms in carcinogenesis. Looking ahead, the findings herein may provide important insights into preventive approaches or therapeutic targets of gastric cancer.

Results

Study population

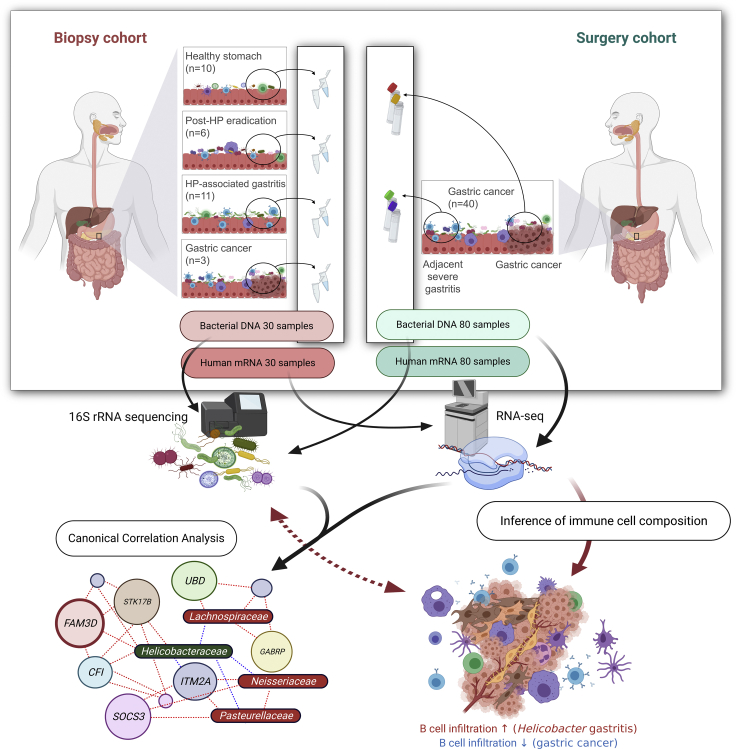

As shown in Figure 1, the study population is composed of two independent cohorts: biopsy cohort and surgery cohort. In the biopsy cohort, bacterial DNA samples and human mRNA samples were obtained from gastric antrum (27 participants without cancer) or gastric cancer lesions (3 gastric cancer patients). Table S1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics of the participants in the biopsy cohort. In this cohort, we compared the microbial composition and human gene expression patterns between disease groups (i.e., post-HP eradication, HP-associated gastritis, and gastric cancer) and the healthy stomach group.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study design

Bacterial DNA and human gastric mRNA samples were obtained from the biopsy and surgery cohorts. The biopsy cohort consisted of asymptomatic volunteers and patients with gastric cancer who were scheduled for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. In this cohort, we compared the microbial composition and human gene expression patterns between disease groups (i.e., post-HP eradication, HP-associated gastritis, and gastric cancer) and the healthy stomach group. The surgery cohort consisted of patients with gastric cancer who underwent gastrectomy. In the surgery cohort, gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis tissues were obtained from each patient. Microbial composition and gene expression patterns were compared between the gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis groups. The association between the microbiome and transcriptome was analyzed using canonical correlation analysis. In addition, the immune cell composition of the tumor microenvironment was investigated through a gene signature-based inference algorithm. Immune cell compositions, and their links to the gastric microbiome, were compared between groups. HP, Helicobacter pylori.

In the surgery cohort, bacterial DNA samples and human mRNA samples were obtained from both gastric cancer lesions and adjacent noncancerous (severe gastritis) lesions in 40 gastric cancer patients. Microbial composition and human gene expression patterns were compared between gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis samples. Participant characteristics in the surgery cohort are shown in Table S2.

Evaluation of intragastric microbiome

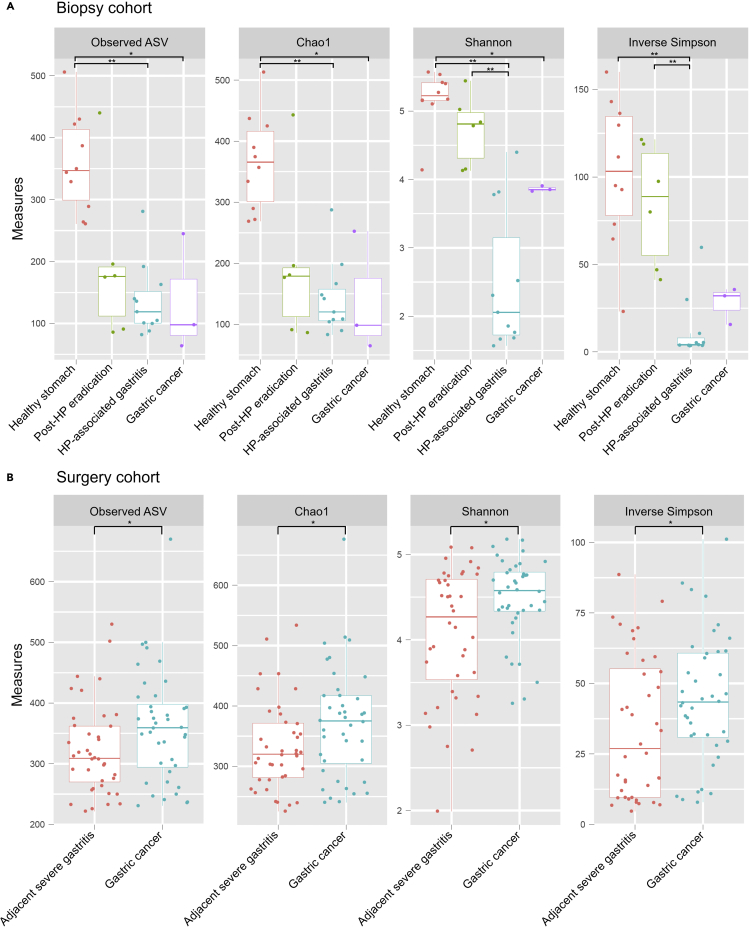

Figure 2 shows the alpha-diversity indices in the study groups of both cohorts. In the biopsy cohort, the number of observed ASVs and Chao1 and Shannon indices were higher in the healthy stomach group than in both HP-associated gastritis (by Mann-Whitney U test: ASVs, p < 0.001; Chao1, p < 0.001; Shannon, p < 0.001) and gastric cancer groups (by Mann-Whitney U test: ASVs, p = 0.035; Chao1, p = 0.035; Shannon, p = 0.028) (Figure 2A). All four measures of intragastric microbial alpha-diversity were found to be lower in patients with HP-associated gastritis compared to the healthy group, possibly because of an overrepresentation of HP during HP infection (Park et al., 2019).

Figure 2.

Alpha-diversity of the gastric microbiome in the biopsy and surgery cohorts

(A) In the biopsy cohort, all alpha-diversity indices were higher in the healthy stomach group than in the HP-associated gastritis group. Significant differences in alpha-diversity indices were not identified between the post-HP eradication and healthy stomach groups.

(B) In the surgery cohort, alpha-diversity indices were higher in the gastric cancer group than in the adjacent severe gastritis group.

ASV, amplicon sequence variant; HP, Helicobacter pylori. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney U test.

In the surgery cohort, all alpha-diversity indices were higher in gastric cancer than in adjacent severe gastritis (by Mann-Whitney U test: ASVs, p = 0.048; Chao1, p = 0.046; Shannon, p = 0.024; Simpson, p = 0.049) (Figure 2B). This is likely caused by the relatively lower abundance of HP (and thereby more even abundances of other bacterial taxa) in gastric cancer than in adjacent severe gastritis (average relative abundance of HP: gastric cancer, 4.2%; adjacent severe gastritis, 26.9%).

The beta-diversity was evaluated using principal coordinate analysis plots (Figure S1). We found that the microbiome composition was significantly different among the groups in both the biopsy and surgery cohorts (by ANOSIM test: biopsy cohort, p < 0.001; surgery cohort, p < 0.001).

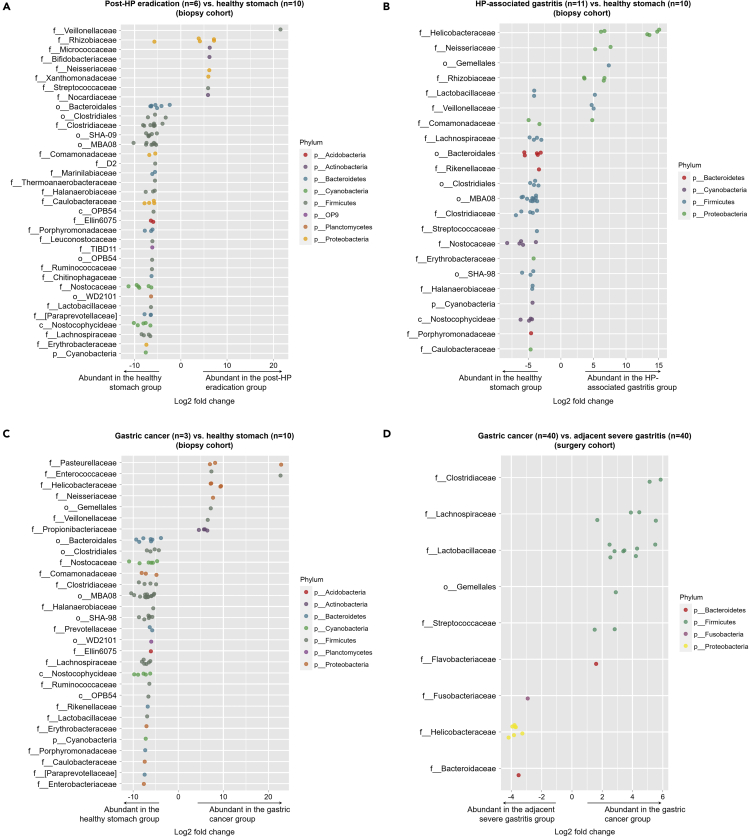

The relative abundances of bacterial taxa at the phylum level are shown in Figure S2. In all disease groups of both cohorts, the most abundant phylum was Proteobacteria followed by Firmicutes; on the other hand, for the healthy stomach group of the biopsy cohort, the abundance of Firmicutes was the highest. Figure 3 shows the bacterial taxa that were differentially abundant between the study groups. For example, several bacterial taxa, especially Veillonellaceae, were of higher abundance in the Post-HP eradication group than in the healthy stomach group (Figure 3A). In addition, the HP-associated gastritis group showed higher abundances in several bacterial taxa, including Helicobacteraceae and Neisseriaceae, compared to the healthy stomach group (Figure 3B). The gastric cancer group in the biopsy cohort also showed higher abundances in several bacterial taxa compared to the healthy stomach group, including Pasteurellaceae and Enterococcaceae (Figure 3C). In the surgery cohort, Helicobacteraceae was more abundant in the adjacent severe gastritis group than in the gastric cancer group (Figure 3D). Gemellales was more abundant in the HP-associated gastritis and gastric cancer groups than in the healthy stomach group (biopsy cohort), and was also more abundant in the gastric cancer group than in the adjacent severe gastritis group (surgery cohort).

Figure 3.

Differential abundance of bacterial ASVs between study groups

(A–D) Post-HP eradication vs. healthy stomach, (B) HP-associated gastritis vs. healthy stomach, and (C) gastric cancer vs. healthy stomach in the biopsy cohort, and (D) gastric cancer vs. adjacent severe gastritis in the surgery cohort. Each point represents bacterial ASVs that significantly differ between the groups. The x axis indicates log2 fold-change of ASVs between the groups. The y axis indicates the bacterial taxa at the family level to which each bacterial ASV belongs. If a taxon has multiple significantly different ASVs, then points corresponding to those ASVs are shown in the respective row. The color of the points indicates the phylum to which the bacterial ASV belongs. HP, Helicobacter pylori; ASV, amplicon sequence variant.

Differential human gene expression

The principal component analysis (PCA) plots for the gene expression datasets showed that the HP-associated gastritis and gastric cancer groups were distinct from the healthy stomach group in the biopsy cohort (Figure S3A). In the surgery cohort, gastric cancer was also distinguishable from adjacent severe gastritis (Figure S3B). Differential gene expression data in the biopsy and surgery cohorts are shown in Table S3. Differential gene expression between the post-HP eradication and healthy stomach groups in the biopsy cohort, related to Table 1, Table S4. Differential gene expression between the HP-associated gastritis and healthy stomach groups in the biopsy cohort, related to Table 1, Table S5. Differential gene expression between the gastric cancer and healthy stomach groups in the biopsy cohort, related to Table 1, Table S6. Differential gene expression between the gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis in the surgery cohort, related to Table 1. LUM, THY1, COL1A1, and PDGFRB, which have been previously identified as marker genes for fibroblasts/myofibroblasts or pericytes in tumor microenvironments (Sathe et al., 2020), were highly expressed in gastric cancer tissues compared to the healthy stomach (biopsy cohort) or adjacent severe gastritis tissues (surgery cohort).

In the biopsy cohort, pathway analysis identified seventeen differentially expressed KEGG pathways, including ‘Intestinal immune network for IgA production’, between the HP-associated gastritis and healthy stomach groups; and six KEGG pathways, including ‘Chemokine signaling’, between the gastric cancer and healthy stomach groups (Table 1). However, there was no differentially expressed KEGG pathway between the post-HP eradication and healthy stomach groups. In the surgery cohort, fourteen KEGG pathways were differentially expressed between gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis. In particular, the ‘Cell cycle’ pathway was upregulated in gastric cancer tissues in both biopsy and surgery cohorts. Among cell cycle pathway-related genes, the proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene (PCNA), which is an essential factor for DNA replication and preferentially expressed in human cancer (Wang, 2014), was highly expressed in gastric cancer tissues of the surgery cohort.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed KEGG pathways between study groups

| KEGG Pathway | p-valuea | Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Biopsy cohort | ||

| Upregulated pathways in the HP-associated gastritis group (vs. healthy stomach) | ||

| hsa04672 Intestinal immune network for IgA production | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| hsa04640 Hematopoietic cell lineage | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| hsa04062 Chemokine signaling pathway | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| hsa04145 Phagosome | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| hsa04380 Osteoclast differentiation | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| hsa04514 Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| hsa04670 Leukocyte transendothelial migration | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| hsa04662 B cell receptor signaling pathway | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| hsa04612 Antigen processing and presentation | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| hsa04650 Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| hsa04620 Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| hsa04610 Complement and coagulation cascades | 0.003 | 0.036 |

| hsa04660 T cell receptor signaling pathway | 0.003 | 0.038 |

| hsa04666 Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis | 0.004 | 0.039 |

| hsa04664 Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway | 0.004 | 0.039 |

| hsa00500 Starch and sucrose metabolism | 0.004 | 0.041 |

| hsa04210 Apoptosis | 0.005 | 0.048 |

| Upregulated pathways in the gastric cancer group (vs. healthy stomach) | ||

| hsa04062 Chemokine signaling pathway | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| hsa04380 Osteoclast differentiation | <0.001 | 0.016 |

| hsa04512 ECM-receptor interaction | <0.001 | 0.020 |

| hsa04670 Leukocyte transendothelial migration | <0.001 | 0.022 |

| hsa04145 Phagosome | <0.001 | 0.032 |

| hsa04110 Cell cycle | <0.001 | 0.034 |

| Surgery cohort | ||

| Upregulated pathways in gastric cancer group (vs. adjacent severe gastritis) | ||

| hsa04110 Cell cycle | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| hsa03030 DNA replication | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| hsa03040 Spliceosome | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| hsa03010 Ribosome | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| hsa03008 Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes | <0.001 | 0.015 |

| hsa04115 p53 signaling pathway | 0.001 | 0.018 |

| hsa03013 RNA transport | 0.001 | 0.018 |

| hsa03050 Proteasome | 0.001 | 0.022 |

| hsa00240 Pyrimidine metabolism | 0.003 | 0.046 |

| Upregulated pathways in the adjacent severe gastritis group (vs. gastric cancer) | ||

| hsa00980 Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| hsa00982 Drug metabolism - cytochrome P450 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| hsa04020 Calcium signaling pathway | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| hsa04971 Gastric acid secretion | <0.001 | 0.011 |

| hsa00830 Retinol metabolism | <0.001 | 0.012 |

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

p-values obtained from a two-sample t test.

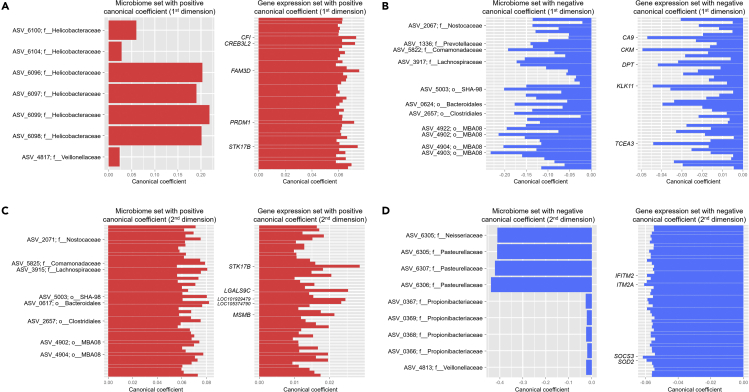

Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) between the intragastric microbiome and human gene expression

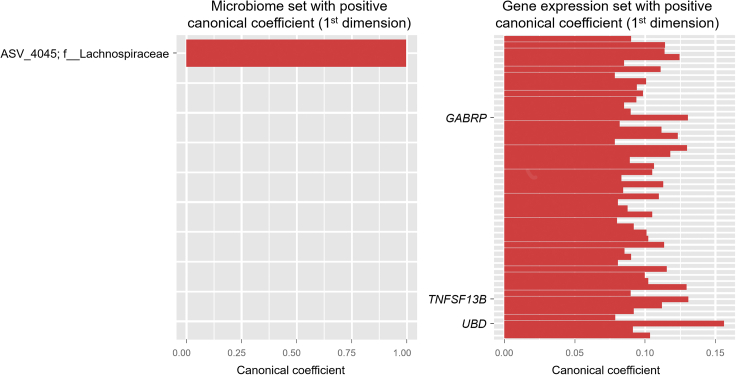

To identify significant associations between the intragastric microbiome and host gastric mucosa transcriptome, we performed CCA, which utilizes dimensionality reduction to identify correlated sets of variables (i.e., canonical variates) from two different data types (Mai and Zhang, 2019; Witten et al., 2009). For the first few strongly correlated (microbial and host gene expression) canonical variates in the CCA model, bacterial ASVs having positive canonical coefficients can be generally regarded as being associated with genes having positive canonical coefficients. Similarly, bacterial ASVs having negative canonical coefficients can be interpreted as being correlated with genes having negative canonical coefficients. In the CCA model for the biopsy cohort, there were several bacterial taxa associated with expressed genes, both of which having positive canonical coefficients (Figure 4A and Table S7). For example, Helicobacteraceae and Veillonellaceae were associated with various genes, including FAM3 Metabolism Regulating Signaling Molecule D (FAM3D), Serine/Threonine Kinase 17b (STK17B), and Complement Factor I (CFI). As shown in Table S4, these genes were expressed higher in the HP-associated gastritis group compared to the healthy stomach group. In addition, associations between bacterial taxa and expressed genes having negative canonical coefficients were observed (Figure 4B). Here, various bacterial taxa, including Comamonadaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Bacteroidales, were associated with genes (e.g., CKM and CA9) expressed higher in the healthy stomach group.

Figure 4.

Canonical correlation analysis between the gastric microbiome and human gene expression in the biopsy cohort

(A–D) Upper panels, (A and B) show the correlated bacterial ASVs and human genes comprising the first canonical variate, whereas lower panels, (C and D) show the correlated bacterial ASVs and human genes comprising the second canonical variate. The y axis indicates bacterial ASVs (ID with taxon) or human genes. The unique identifiers of the ASV IDs are shown in Table S9. Up to the top 50 ASVs or the top 50 genes are plotted. HP, Helicobacter pylori; ASV, amplicon sequence variant; ID, identification.

The CCA between microbiome and gene expression data may help to identify the most clinically relevant genes and bacteria. For example, Helicobacteraceae was the most abundant taxonomic family in participants with HP infection. Therefore, we may regard a set of genes associated with ASVs belonging to Helicobacteraceae as representative genes of the HP-associated gastritis group. These genes included FAM3D, STK17B, and CFI, which are involved in inflammation. FAM3D has a high affinity with formyl peptide receptors 1 and 2, which are highly expressed on the surface of neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages (Peng et al., 2016). In addition, FAM3D has been found to be upregulated in the colon of the dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis model (Peng et al., 2016). STK17B may also be involved in gastric inflammation. The expression of STK17B was reduced after HP eradication therapy in patients with HP infection (Resnick et al., 2006). CFI, also known as C3b/C4b inactivator, is a protein of the complement system, and regulates complement activation (Lachmann and Muller-Eberhard, 1968). Although the effect of CFI on HP infection is not well known, Helicobacter felis infection of IL-10-deficient mice resulted in a marked increase in the levels of complement in serum (Ismail et al., 2003). Therefore, gastric inflammation ensuing HP infection may involve the complement system.

In Figures 4C and 4D, we show bacterial ASVs and expressed genes comprising the second pair of canonical variates in the CCA model for the biopsy cohort. As shown in Figure 4D, several bacterial taxa, including Pasteurellaceae, Neisseriaceae, Propionibacteriaceae, and Veillonellaceae, were associated with the expression of various genes, including Suppressor Of Cytokine Signaling 3 (SOCS3), Integral Membrane Protein 2A (ITM2A), Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2), and Interferon Induced Transmembrane Protein 2 (IFITM2).

SOD2 and IFITM2 have been previously reported to be involved in gastric cancer. SOD2 is induced upon Toll-like receptor two activation in human gastric cancer cells, and its expression is correlated with a risk of distant metastasis in patients with gastric cancer (Liu et al., 2019a). IFITM2 expression was upregulated in gastric cancer tissues and was correlated with gastric cancer progression, postoperative recurrence, and higher mortality (Xu et al., 2017). IFITM2 knockdown in gastric cancer cell lines decreased gastric cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (Xu et al., 2017). In the case of SOCS3, its role in gastric carcinogenesis has not yet been fully elucidated; however, SOCS3 has been found to be highly expressed in patients with HP-associated gastritis, and HP triggers SOCS3 expression via p38 signaling (Sarajlic et al., 2020). Interestingly, gastric tumors can develop in mice with conditional SOCS3 knockout by enhancing leptin production and activating the leptin-signal transducer and activator of transcription three signaling pathway (Inagaki-Ohara et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2015). The role of ITM2A in gastric carcinogenesis is also unknown, although ITM2A is a tumor suppressor that induces cell-cycle arrest, acts as a chemosensitizer in ovarian cancer, and inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation (Nguyen et al., 2016).

Associations between bacterial taxa and expressed genes for the surgery cohort (gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis) are shown in Figure 5 and Table S8. Lachnospiraceae was the only taxon correlated with the expression of human genes, including Ubiquitin D (UBD) and Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptor Subunit Pi (GABRP). UBD regulates mitosis and reduces cell cycle time by combining with the spindle checkpoint protein Mitotic Arrest Deficient 2 (Liu et al., 1999). It was found to be upregulated in gastric cancer tissue and positively correlated with mutant p53 expression, lymph node metastasis, and tumor progression (Ji et al., 2009).

Figure 5.

Canonical correlation analysis between the gastric microbiome and human gene expression in the surgery cohort

The correlated bacterial ASVs and human genes comprising the first canonical variate. Bacterial ASVs and human genes with negative canonical coefficients are not shown because there were no such genes in the CCA model. The y axis indicates bacterial ASVs (ID with taxon) or human genes. The unique identifiers of the ASV IDs are shown in Table S9. The top 50 genes are plotted

CCA, canonical correlation analysis; ASV, amplicon sequence variant; ID, identification.

Scatterplots for the canonical variates are shown in Figure S4. Modest correlations were observed between the microbiome and gene sets.

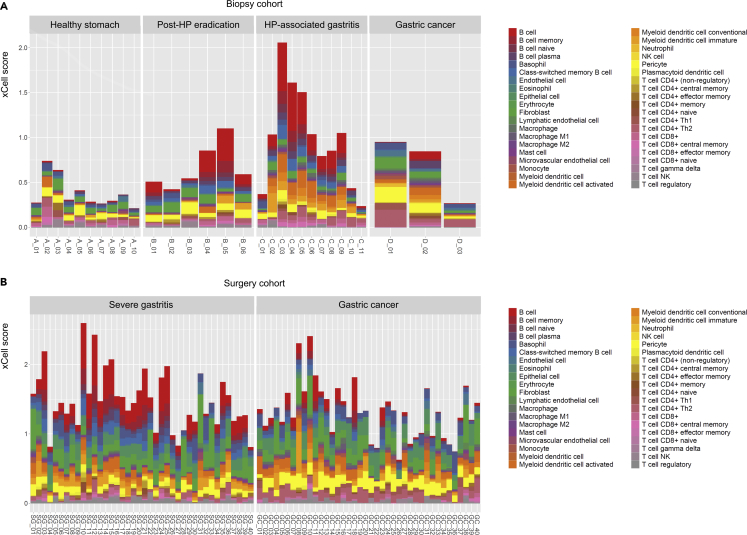

Immune-microbiome associations

Finally, we sought to identify connections between the intragastric microbiome and immune cells inferred to be infiltrating gastric tissues. We first performed cell-type enrichment analysis on our bulk RNA-seq data using xCell, which calculates ‘xCell scores’ of 40 different cell types for each sample. Briefly, a higher xCell score for a particular cell type indicates an estimated greater amount of the corresponding cells. In the biopsy cohort, the sum of xCell scores increased going from the healthy stomach, to the post-HP eradication, and to the HP-associated gastritis groups (Figure 6A), possibly indicating greater immune cell infiltration in biopsied tissues with rising disease severity. In particular, B cell infiltration was prominent in the HP-associated gastritis group. However, the amount of infiltrated B cells in the gastric cancer group was lower than that in the HP-associated gastritis group (biopsy cohort) or the adjacent severe gastritis group (surgery cohort) (Figures 6A and 6B). The PCA plots in Figure S5 show different immune cell type patterns between the healthy and unhealthy stomach groups in the biopsy cohort, and gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis groups in the surgery cohort. To ensure the robustness of our immune cell identification results, we performed an additional cell-type enrichment analysis on our RNA-seq data using Cell-type Identification By Estimating Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT) (Newman et al., 2015). Similar to the previous estimations by xCell, B cell infiltration was a prominent characteristic in the HP-associated gastritis group (biopsy cohort) and the adjacent severe gastritis group (surgery cohort) (Figure S6).

Figure 6.

Inferred abundances of 40 different cell types in gastric tissues

(A and B) Biopsy cohort and (B) surgery cohort. Cell-type enrichment analysis was performed using a gene signature-based approach (xCell). The xCell score serves as a proxy for the abundance of the corresponding cell type. In the biopsy cohort, B cell infiltration was more abundant in the HP-associated gastritis group than in the gastric cancer group. Enriched B cell infiltration in the severe gastritis tissues was also observed in the surgery cohort. The x axis indicates each sample in the biopsy and surgery cohorts. The prefix of each sample label denotes the study group (A_: healthy stomach, B_: post-HP eradication, C_: HP-associated gastritis, D_: gastric cancer [biopsy cohort], GC_: gastric cancer [surgery cohort], and SG_: severe gastritis). The y axis indicates the xCell score. HP, Helicobacter pylori; SG, severe gastritis; GC, gastric cancer.

Hierarchical clustering on immune cell type composition profiles revealed that most unhealthy gastric tissues (i.e., post-HP eradication, HP-associated gastritis, and gastric cancer) in the biopsy cohort were clustered away from healthy gastric tissues (Figure S7A). Furthermore, for the surgery cohort, gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis were different in their immune cell type compositions (Figure S7B).

Correlations between bacterial taxa and infiltrated immune cell types are shown in Figure S8. Helicobacteraceae, which was the most prominent bacterial taxon in HP-associated gastritis (biopsy cohort) and adjacent severe gastritis (surgery cohort), was correlated with B cells. The correlations between bacterial taxa and immune cell types were further investigated according to the clinical phenotype (i.e., healthy and unhealthy groups in the biopsy cohort; and adjacent severe gastritis and gastric cancer groups in the surgery cohort) (Figure S9). In the unhealthy stomach group of the biopsy cohort, several bacterial taxa, including Helicobacteraceae, Enterococcaceae, and Bacteroidales, were highly correlated with activated myeloid dendritic cells. Macrophages were correlated with Gemellales and Neisseriaceae, which were largely abundant bacterial taxa in the gastric cancer group. In the gastric cancer group of the surgery cohort, macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells were highly correlated with Lactobacillaceae. To summarize our main findings, we provide a comprehensive, qualitative description of several representative associations among intragastric microbiome, expressed genes, and infiltrating immune cells in gastric tissues in Figure S10.

Subgroup analysis by histologic subtypes of gastric cancer

To identify differences in microbiome, host gene expression, and immune cell enrichment patterns between gastric cancer subtypes, we delineated subgroups of gastric cancers of the surgery cohort according to the WHO histology-based classification criteria. Our PCA ordination plots show that the gastric cancer subtypes (i.e., well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma) are not distinguishable from each other (Figure S11), most likely indicating a lack of significant differences in any of the three data types.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated differences in the intragastric microbiome and in gene expression among normal, gastritis, and gastric cancer tissues. The multi-omic approach demonstrated herein allowed us to pinpoint both bacterial taxa and host genes relevant to gastric carcinogenesis in the same setting. For example, we identified 16 significant bacterial ASVs (7 unique bacterial taxa) and 583 significant genes in HP-associated gastritis compared to healthy stomach. From these, we identified a bacterial taxon (Helicobacteraceae) and genes (FAM3D and STK17B) to be the most significant and hence possibly clinically meaningful. Likewise, several bacterial taxa (Pasteurellaceae and Neisseriaceae) and genes (SOCS3 and ITM2A) were found to be associated with gastric cancer compared to healthy ones. In the comparison between gastric cancer and adjacent severe gastritis (in the surgery cohort), Lachnospiraceae and several genes, including UBD and GABRP, were identified to be associated with gastric cancer.

Another strength of our analysis is that our cohorts have multiple groups representing a different clinical phenotype along the gastric carcinogenesis pathway: normal, HP-associated gastritis, post-HP eradication status, and gastric cancer. Therefore, our findings on microbiome-gene associations may advise future strategies for stratifying the risk of gastric cancer. For example, PCR-based marker panels could test for significant bacterial taxa and gene expression simultaneously, and thereby facilitate the selection of high-risk individuals for gastric cancer who require intensive endoscopic surveillance.

In addition, significant bacterial taxa associated with gastritis or gastric cancer may be potential targets of gastric cancer prevention or treatment. As HP eradication therapy is already being used to prevent gastric cancer (Ford et al., 2020), studies such as ours can provide insight into the development of other microbe-targeting therapies, such as live biotherapeutics and microbiota transplantation. Ideally, a better understanding of the differences in the intragastric microbiome between different clinical phenotypes of the gastric carcinogenesis pathway will contribute to the discovery of preventive or therapeutic options in gastric cancer.

Our identified associations between microbiome and human immune cells facilitate a ‘systems-level’ understanding of the cross-kingdom interconnectivity characterizing the gastric tumor microenvironment. As mentioned above, gastritis tissues were found to have higher abundances of HP and more infiltration of B cells compared to the healthy stomach. In gastric cancer tissues, however, infiltration of immune cells was less significant compared to normal or gastritis tissues. The identified B cell infiltration in HP-associated gastritis and adjacent severe gastritis, as well as the putative interactions between other intragastric microorganisms and immune cells, will be subject to validation in future studies.

Interestingly, in gastric cancer tissues in both the biopsy and surgery cohorts, our study showed overexpression of several marker genes for fibroblasts/myofibroblasts or pericytes. To this point, cancer-associated fibroblasts were found to produce many growth factors and proinflammatory cytokines to recruit immunosuppressive cells into the tumor microenvironment and contribute to the immune evasion of cancer cells (Liu et al., 2019b). Pericytes also assist the immune evasion mechanism by enhancing the tight junction function and endothelial barrier.

Although no study has yet to show that the intragastric microbiome is associated with gastric cancer immunotherapy, multiple studies have investigated the influence of the gut microbiome on response to immunotherapy in cancer-bearing hosts (Andrews et al., 2021; Gopalakrishnan et al., 2018; Matson et al., 2021; Oster et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2020; Routy et al., 2018). In this regard, the myriad associations between intragastric microbes and immune cells identified herein suggest an intricately coupled system, and thereby allude to the possibility that the state of the intragastric microbiome may have implications in the efficacy of anti-gastric cancer immunotherapy.

Differences in microbial diversity across the study groups with different clinical phenotypes were also of high interest. The microbial diversity was highest in the healthy stomach group, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (Guo et al., 2020; Serrano et al., 2019). Intragastric microbiome in patients with HP-associated gastritis showed the lowest microbial diversity, which is likely a result of an overrepresentation of HP. Notably, HP eradication therapy in patients with HP infection has been associated with partial restoration of normal microbial diversity (Guo et al., 2020). The abundant bacterial taxa in patients who received HP eradication, including Veillonellaceae, Micrococcaceae, and Streptococcaceae, may originate from the oral cavity (Park et al., 2020). In addition, our observation that intragastric microbial diversity is different across disease states is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Aviles-Jimenez et al., 2014; Ferreira et al., 2018; Gantuya et al., 2020; Hsieh et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Several studies in both eastern and western hemispheres have demonstrated that alpha-diversity in the stomach is higher in healthy individuals, whereas that is lower in patients with intestinal metaplasia or gastric cancer (Aviles-Jimenez et al., 2014; Ferreira et al., 2018; Gantuya et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Our finding that the abundance of HP-related taxa was lower in patients with gastric cancer than in patients with HP-associated gastritis is consistent with a previous report (Hsieh et al., 2018). Given our results and those from other relevant studies, we conclude that changes in the intragastric microbiome according to gastric disease states are a robust phenomenon.

In summary, our study demonstrates how the intragastric microbiome is linked to gastric mucosal transcriptome and to immune cells in the major stages of gastric carcinogenesis. Looking ahead, a combined analysis of microbiome and gene expression may help to devise a diagnostic kit that screens for high-risk patients of gastric cancer who require surveillance endoscopy. In addition, this study can be a basis for discovering preventive or therapeutic targets of gastric cancer. In all, the results presented herein elucidate connections underlying the microbiome-immune cell relationship in gastric carcinogenesis. Our promising study warrants future comprehensive, multi-omic investigations into the interactions governing the intragastric microbiome and gastric tumor microenvironment.

Limitations of the study

We acknowledge the following limitations of our study: First, this is a retrospective study. The utility of our identified genes as biomarkers for risk stratification and screening should be further evaluated through prospective studies. Second, we did not seek to observe longitudinal changes in microbiome and transcriptome. Serial follow-up analyses in the same patient need to be performed to determine the changes over time. However, gastric carcinogenesis is a life-long process, and it is challenging to observe gastritis patients until gastric cancer develops. Therefore, our unique cohort designed to include various gastric carcinogenesis steps is still very useful to investigate differences in the intragastric environment depending on gastric disease states. Third, median age differed across the study groups. This is a clear limitation because age can be a confounding factor. However, this factor is difficult to strictly control for, as individuals with healthy stomachs are usually young whereas gastric cancer mostly occurs in older people. We deliberately did not include young-age onset gastric cancer because of possible differences in clinical characteristics and pathogenesis compared to typical gastric cancer (Zhou et al., 2021). Fourth, all the study participants were from a single ethnic group (Korean). Although samples derived from Koreans may provide clinically useful information because gastric cancer incidence is comparatively high in South Korea (Rawla and Barsouk, 2019), we emphasize caution in generalizing our findings to other ethnic groups.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Chan Hyuk Park (chan100@hanyang.ac.kr).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Study population and study design overview

The Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects Research and Ethics Committee, Hanyang University Guri Hospital, Korea, approved the study protocol (GURI 2019-09-035-003). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

A total of seventy adult participants were included in this study. The age and sex information is described in Tables S1 and S2. Although we included both male and female participants, the sex ratio was unbalanced depending on the disease group. For example, there were more male participants than female participants in patients with gastric cancer because gastric cancer is prevalent in men. Figure 1 provides an overview of the overall study design and key outcomes of our study. All participants in this study were recruited as two separate cohorts (biopsy [n = 30] and surgery [n = 40] cohorts), from whom bacterial DNA and human gastric RNA samples were obtained. In the biopsy cohort, asymptomatic volunteers and patients with gastric cancer were recruited. Participants were classified into the following four groups according to histopathologic examination and history of HP eradication therapy: (i) healthy stomach, i.e., participants who had never been infected with HP; (ii) post-HP eradication, i.e., participants who had a history of HP infection but received successful HP eradication therapy; (iii) HP-associated gastritis, i.e., participants who had a current or past HP infection and did not receive HP eradication therapy; and (iv) gastric cancer, i.e., patients who were diagnosed with histopathologically confirmed gastric cancer. In the biopsy cohort, gastric mucosal samples were obtained by endoscopic biopsy from the greater curvature side of the mid-antrum. In patients with gastric cancer, biopsy samples were obtained from the lesion site instead of the mid-antrum.

In the surgery cohort, patients who underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer were recruited. Fresh-frozen gastric tissues of those patients were provided by the Biobank of Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital and Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, who are institutional members of the Korea Biobank Network (Lee et al., 2012). Surgical samples were obtained from both gastric cancer lesions and adjacent severe gastritis lesions. Gastric cancer samples were classified into five subtypes by histology using the WHO classification (well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma) (Bosman et al., 2010).

Microbial taxonomic compositions were analyzed and compared using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. Gene expression patterns were evaluated using RNA-seq analysis. Additionally, a gene expression signature-based inference algorithm was used to investigate the immune cells comprising tumor microenvironment. Thereafter, we analyzed the association between the microbiome and host transcriptome, and between the microbiome and immune cell composition.

Method details

16S rRNA gene sequencing and analysis

For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, DNA was extracted from biopsy and surgical samples using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Briefly, 100 mg of frozen tissue was suspended in 1 mL of InhibitEX buffer, mashed with a pestle, and vortexed for 1 min. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 1 min. After adding 25 μL of proteinase K into a fresh tube, 600 μL of supernatant was added to the proteinase K-containing tube. Then, 600 μL of AL buffer was added and the mixture was vortexed, followed by incubation at 70°C for 10 min. Then, 600 μL of ethanol was added to the lysate and mixed by vortexing. Lysate (600 μL) was carefully applied to the QIAamp spin column, centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 1 min, and the supernatant was discarded. This step was repeated twice. Then, 500 μL of AW1 buffer was added and centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 5 min. After discarding the supernatant, 500 μL of AW2 buffer was added and centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 5 min. Again, after discarding the supernatant, the QIAamp spin column was transferred into a new tube, and 200 μL of ATE buffer was added. After incubating for 5 min at 15–25°C, it was centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 1 min to elute the DNA. Isolated DNA was stored at −80°C until microbial characterization.

Extracted DNA was amplified by targeting the V3 to V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene. High-throughput sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quality control and trimming of the raw sequences, and constructing the final table of features (amplicon sequence variants [ASVs]), were performed using the QIIME two pipeline (Bolyen et al., 2019). For taxonomic assignment, the feature classifier trained by ‘feature-classifier’ plugin of QIIME two on the GreenGenes 13.8 database with 97% similarity level was used (Bokulich et al., 2018). Downstream analyses, including alpha- and beta-diversity analyses, were performed using the phyloseq package (version 1.34.0) in R (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013).

Gastric tissue mRNA sequencing and analysis

RNA extraction for human gene expression analysis was performed using the Hybrid-R Total RNA Isolation Kit (GeneAll Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). Briefly, 100 mg of frozen tissue was homogenized in 1 mL of RiboEx™ and incubated for 5 min at 15–25°C. Then, chloroform (0.2 mL) was added, and the tissue was further incubated for 2 min at 15–25°C followed by centrifugation at 15,000 ×g for 15 min at 4°C. After transferring the aqueous phase to a fresh tube, absolute isopropanol (0.5 mL) was added and the tube incubated for 10 min at 15–25°C. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded. Then, 1 mL of 75% ethanol was added and centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 5 min at 4°C. After discarding the ethanol, RNA pellet was air-dried for 5 min. Finally, RNA was dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water and incubated for 10 min at 56°C.

For RNA sequencing, the mRNA library was prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina) and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 platform with a per-sample target of 50 million 150 bp paired-end reads. Quality control on the raw sequences was performed using FastQC (version 0.11.9) (Andrews, 2010). Next, Trimmomatic (version 0.39) was used for quality trimming and adapter removal (Bolger et al., 2014). Additionally, we used SortMeRNA (version 4.2.0) to remove the potentially remaining rRNA sequence (Kopylova et al., 2012). Finally, we mapped the reads to the genome using STAR (version 2.5.4b) (Dobin et al., 2013). Downstream analysis for differential gene expression was performed using the DESeq2 package (version 1.28.1) in R (Love et al., 2014).

To identify enriched functional pathways in the gene expression data, we performed gene set enrichment analysis using the ‘gage’ (Generally Applicable Gene-set Enrichment for Pathway Analysis) package (version 2.40.1) in R (Luo et al., 2009). This software package provides the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways associated with a given gene set (e.g., upregulated or downregulated genes between study groups).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Association between microbiome and host genes

In the biopsy cohort, significantly different ASVs and expressed genes between each disease group (i.e., post-HP eradication, HP-associated gastritis, and gastric cancer) and the healthy stomach group were identified. In the surgery cohort, significantly different ASVs and expressed genes between the gastric cancer and adjacent gastritis groups were identified. To model the relationship between the differentially abundant ASVs and differentially expressed (host) genes, we used canonical correlation analysis (CCA) implemented in the PMA package (version 1.2.1) in R (Mai and Zhang, 2019; Witten et al., 2009). CCA is an approach for multivariate analysis of correlation. More specifically, it is a method to evaluate the relationships between two sets of variables (vectors) measured from the same individual. Due to the high dimensionality of microbiome and gene expression data, it is clearly very difficult and impractical to analyze (and interpret) all relationships between each microbe and each gene simultaneously. Rather, CCA allows one to summarize the relationships into a small number of statistics while preserving the main facets of the relationships. For multiple x (e.g., ASVs) and multiple y (e.g., expressed genes), the CCA constructs two canonical variates CVX1 = α1x1+α2x2+ … +αnxn and CVY1 = β1y1+β2y2+ … +βmym. The canonical coefficients α1 … αn and β1 … βm are chosen so that they maximize the correlation between the canonical variates CVX1 and CVY1. As such, the first two canonical variate pairs CVX1 and CVY1 represent the maximum correlation. Because the CCA is based on a dimensionality reduction technique, the second pair of canonical variates can be obtained by finding the correlation of the variables uncorrelated with (or linearly orthogonal to) the first pair of canonical variates. In each pair of canonical variates, variables with same direction of coefficients (e.g., positive αn and positive βm, or negative αn and negative βm) can be regarded as having multiple correlations among themselves because they increase (or decrease) both canonical variates CVX and CVY.

Immune cell type enrichment analysis

To infer immune cell composition from bulk transcriptomic (RNA-seq) data, we utilized xCell, which is a gene expression signature-based computational inference algorithm that performs cell type enrichment analysis on RNA-seq data (Aran et al., 2017). In this study, 30 immune cell types, five stromal cell types, and two other cell types (epithelial cell and erythrocyte) were included in the analysis. Abundances of different cell types, which were estimated through xCell (version 1.1.0), were compared between study groups. Hierarchical clustering was also used to identify the relationship between study groups and different cell types. Additionally, we investigated the association in abundances between bacterial taxa and immune cell types using Spearman's rank correlation test. To ensure robustness of our xCell analysis results, immune cell composition was additionally estimated using CIBERSORT, which is a deconvolution-based approach (Newman et al., 2015).

Statistical analysis

For demographic and clinical characteristics, continuous variables were compared between groups using the Mann-Whitney U test, while categorical variables were compared between groups using the Fisher’s exact test. In the microbiome dataset, beta-diversity was tested using analysis of similarities (ANOSIM), which is a test of whether there is a significant difference between two or more groups of sampling units (Clarke, 1993). Differential analysis for screening significant ASVs and expressed genes was performed using the Wald test. p-values for multiple tests were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction procedure. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.0.4).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2021R1C1C1005728) (C.H.P.). The biospecimens and clinical information in the surgery cohort were provided by the Biobank of Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital and Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, who are institutional members of the Korea Biobank Network. Graphical abstract and Figure 1 were created with BioRender.com.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, C.H.P. and T.H.H.; Methodology, C.H.P., C.H., and T.H.H.; Investigation, C.H.P., C.H., and A.L.; Writing – Original Draft, C.H.P.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.H.P., C.H., A.L., J.S., and T.H.H.; Funding Acquisition, C.H.P.; Resources, C.H.P., C.H., and T.H.H; Supervision, J.S., and T.H.H.

Declaration of interest

No disclosures were reported.

Published: March 18, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.103956.

Contributor Information

Jaeyun Sung, Email: sung.jaeyun@mayo.edu.

Tae Hyun Hwang, Email: hwang.taehyun@mayo.edu.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

De-identified 16S rRNA gene sequencing and RNA-seq data in this study have been deposited at NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Bioproject accession numbers for these datasets are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

All original code has been deposited at Zenodo and is publicly available as of the date of publication. DOIs are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

References

- Andrews M.C., Duong C.P.M., Gopalakrishnan V., Iebba V., Chen W.S., Derosa L., Khan M.A.W., Cogdill A.P., White M.G., Wong M.C., et al. Gut microbiota signatures are associated with toxicity to combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade. Nat. Med. 2021;27:1432–1441. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. FASTQC. A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc

- Aran D., Hu Z., Butte A.J. xCell: digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol. 2017;18:220. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1349-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviles-Jimenez F., Vazquez-Jimenez F., Medrano-Guzman R., Mantilla A., Torres J. Stomach microbiota composition varies between patients with non-atrophic gastritis and patients with intestinal type of gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4202. doi: 10.1038/srep04202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich N.A., Kaehler B.D., Rideout J.R., Dillon M., Bolyen E., Knight R., Huttley G.A., Gregory Caporaso J. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2's q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 2018;6:90. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolyen E., Rideout J.R., Dillon M.R., Bokulich N.A., Abnet C.C., Al-Ghalith G.A., Alexander H., Alm E.J., Arumugam M., Asnicar F., et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman F.T., Carneiro F., Hruban R.H., Theise N.D. Fourth edition. vol. 3. IARC; 2010. (WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System). [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993;18:117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Correa P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1995;19:S37–S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crew K.D., Neugut A.I. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006;12:354–362. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira R.M., Pereira-Marques J., Pinto-Ribeiro I., Costa J.L., Carneiro F., Machado J.C., Figueiredo C. Gastric microbial community profiling reveals a dysbiotic cancer-associated microbiota. Gut. 2018;67:226–236. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford A.C., Yuan Y., Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2020;69:2113–2121. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J., Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:197–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantuya B., El Serag H.B., Matsumoto T., Ajami N.J., Uchida T., Oyuntsetseg K., Bolor D., Yamaoka Y. Gastric mucosal microbiota in a Mongolian population with gastric cancer and precursor conditions. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;51:770–780. doi: 10.1111/apt.15675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan V., Spencer C.N., Nezi L., Reuben A., Andrews M.C., Karpinets T.V., Prieto P.A., Vicente D., Hoffman K., Wei S.C., et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359:97–103. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Zhang Y., Gerhard M., Gao J.J., Mejias-Luque R., Zhang L., Vieth M., Ma J.L., Bajbouj M., Suchanek S., et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori on gastrointestinal microbiota: a population-based study in Linqu, a high-risk area of gastric cancer. Gut. 2020;69:1598–1607. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin Y., Seldin M., Lusis A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 2017;18:83. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Y.Y., Tung S.Y., Pan H.Y., Yen C.W., Xu H.W., Lin Y.J., Deng Y.F., Hsu W.T., Wu C.S., Li C. Increased abundance of clostridium and fusobacterium in gastric microbiota of patients with gastric cancer in taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:158. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18596-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki-Ohara K., Mayuzumi H., Kato S., Minokoshi Y., Otsubo T., Kawamura Y.I., Dohi T., Matsuzaki G., Yoshimura A. Enhancement of leptin receptor signaling by SOCS3 deficiency induces development of gastric tumors in mice. Oncogene. 2014;33:74–84. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Cancer today. 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today

- Ismail H.F., Zhang J., Lynch R.G., Wang Y., Berg D.J. Role for complement in development of helicobacter-induced gastritis in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:7140–7148. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7140-7148.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji F., Jin X., Jiao C.H., Xu Q.W., Wang Z.W., Chen Y.L. FAT10 level in human gastric cancer and its relation with mutant p53 level, lymph node metastasis and TNM staging. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2228–2233. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopylova E., Noe L., Touzet H. SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3211–3217. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann P.J., Muller-Eberhard H.J. The demonstration in human serum of "conglutinogen-activating factor" and its effect on the third component of complement. J. Immunol. 1968;100:691–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.E., Kim J.H., Hong E.J., Yoo H.S., Nam H.Y., Park O. National biobank of korea: quality control programs of collected-human biospecimens. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2012;3:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.W.J., Plichta D., Hogstrom L., Borren N.Z., Lau H., Gregory S.M., Tan W., Khalili H., Clish C., Vlamakis H., et al. Multi-omics reveal microbial determinants impacting responses to biologic therapies in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:1294–1304.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Hwang H., Nam K.T. Immune response and the tumor microenvironment: how they communicate to regulate gastric cancer. Gut Liver. 2014;8:131–139. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2014.8.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Han C., Wang S., Fang P., Ma Z., Xu L., Yin R. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: an emerging target of anti-cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019;12:86. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0770-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.C., Pan J., Zhang C., Fan W., Collinge M., Bender J.R., Weissman S.M. A MHC-encoded ubiquitin-like protein (FAT10) binds noncovalently to the spindle assembly checkpoint protein MAD2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1999;96:4313–4318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.D., Yu L., Ying L., Balic J., Gao H., Deng N.T., West A., Yan F., Ji C.B., Gough D., et al. Toll-like receptor 2 regulates metabolic reprogramming in gastric cancer via superoxide dismutase 2. Int. J. Cancer. 2019;144:3056–3069. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Price J., Arze C., Ananthakrishnan A.N., Schirmer M., Avila-Pacheco J., Poon T.W., Andrews E., Ajami N.J., Bonham K.S., Brislawn C.J., et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature. 2019;569:655–662. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lordick F., Shitara K., Janjigian Y.Y. New agents on the horizon in gastric cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:1767–1775. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W., Friedman M.S., Shedden K., Hankenson K.D., Woolf P.J. GAGE: generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai Q., Zhang X. An iterative penalized least squares approach to sparse canonical correlation analysis. Biometrics. 2019;75:734–744. doi: 10.1111/biom.13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson V., Chervin C.S., Gajewski T.F. Cancer and the microbiome-influence of the commensal microbiota on cancer, immune responses, and immunotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:600–613. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie P.J., Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman A.M., Liu C.L., Green M.R., Gentles A.J., Feng W., Xu Y., Hoang C.D., Diehn M., Alizadeh A.A. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.M., Shin I.W., Lee T.J., Park J., Kim J.H., Park M.S., Lee E.J. Loss of ITM2A, a novel tumor suppressor of ovarian cancer through G2/M cell cycle arrest, is a poor prognostic factor of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016;140:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster P., Vaillant L., Riva E., McMillan B., Begka C., Truntzer C., Richard C., Leblond M.M., Messaoudene M., Machremi E., et al. Helicobacter pylori infection has a detrimental impact on the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies. Gut. 2021;71:457–466. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.H., Lee A.R., Lee Y.R., Eun C.S., Lee S.K., Han D.S. Evaluation of gastric microbiome and metagenomic function in patients with intestinal metaplasia using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12547. doi: 10.1111/hel.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.H., Seo S.I., Kim J.S., Kang S.H., Kim B.J., Choi Y.J., Byun H.J., Yoon J.H., Lee S.K. Treatment of non-erosive reflux disease and dynamics of the esophageal microbiome: a prospective multicenter study. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:15154. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X., Xu E., Liang W., Pei X., Chen D., Zheng D., Zhang Y., Zheng C., Wang P., She S., et al. Identification of FAM3D as a new endogenous chemotaxis agonist for the formyl peptide receptors. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:1831–1842. doi: 10.1242/jcs.183053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z., Cheng S., Kou Y., Wang Z., Jin R., Hu H., Zhang X., Gong J.F., Li J., Lu M., et al. The gut microbiome is associated with clinical response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020;8:1251–1261. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price N.D., Magis A.T., Earls J.C., Glusman G., Levy R., Lausted C., McDonald D.T., Kusebauch U., Moss C.L., Zhou Y., et al. A wellness study of 108 individuals using personal, dense, dynamic data clouds. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:747–756. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawla P., Barsouk A. Epidemiology of gastric cancer: global trends, risk factors and prevention. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14:26–38. doi: 10.5114/pg.2018.80001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M.B., Sabo E., Meitner P.A., Kim S.S., Cho Y., Kim H.K., Tavares R., Moss S.F. Global analysis of the human gastric epithelial transcriptome altered by Helicobacter pylori eradication in vivo. Gut. 2006;55:1717–1724. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.095646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routy B., Le Chatelier E., Derosa L., Duong C.P.M., Alou M.T., Daillere R., Fluckiger A., Messaoudene M., Rauber C., Roberti M.P., et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359:91–97. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama N.R., Hartung M.L., Muller A. Life in the human stomach: persistence strategies of the bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:385–399. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarajlic M., Neuper T., Vetter J., Schaller S., Klicznik M.M., Gratz I.K., Wessler S., Posselt G., Horejs-Hoeck J. H. pylori modulates DC functions via T4SS/TNFalpha/p38-dependent SOCS3 expression. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020;18:160. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00655-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathe A., Grimes S.M., Lau B.T., Chen J., Suarez C., Huang R.J., Poultsides G., Ji H.P. Single-cell genomic characterization reveals the cellular reprogramming of the gastric tumor microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:2640–2653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano C.A., Pierre R., Van Der Pol W.J., Morrow C.D., Smith P.D., Harris P.R. Eradication of helicobacter pylori in children restores the structure of the gastric bacterial community to that of noninfected children. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:1673–1675. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Qi L., Chen H., Zhang J., Guan Q., He J., Li M., Guo Z., Yan H., Li P. Identification of genes universally differentially expressed in gastric cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021;2021:7326853. doi: 10.1155/2021/7326853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Chen D., Yuan D., Lausted C., Choi J., Dai C.L., Voillet V., Duvvuri V.R., Scherler K., Troisch P., et al. Multi-omics resolves a sharp disease-state shift between mild and moderate COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183:1479–1495.e1420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung J.J.Y., Coker O.O., Chu E., Szeto C.H., Luk S.T.Y., Lau H.C.H., Yu J. Gastric microbes associated with gastric inflammation, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia 1 year after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut. 2020;69:1572–1580. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong M., Zheng W., Li H., Li X., Ao L., Shen Y., Liang Q., Li J., Hong G., Yan H., et al. Multi-omics landscapes of colorectal cancer subtypes discriminated by an individualized prognostic signature for 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e242. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2016.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainberg M., Magis A.T., Earls J.C., Lovejoy J.C., Sinnott-Armstrong N., Omenn G.S., Hood L., Price N.D. Multiomic blood correlates of genetic risk identify presymptomatic disease alterations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2020;117:21813–21820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2001429117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.C. PCNA: a silent housekeeper or a potential therapeutic target? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;35:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Gao X., Zeng R., Wu Q., Sun H., Wu W., Zhang X., Sun G., Yan B., Wu L., et al. Changes of the gastric mucosal microbiome associated with histological stages of gastric carcinogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:997. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten D.M., Tibshirani R., Hastie T. A penalized matrix decomposition, with applications to sparse principal components and canonical correlation analysis. Biostatistics. 2009;10:515–534. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Zhou R., Yuan L., Wang S., Li X., Ma H., Zhou M., Pan C., Zhang J., Huang N., et al. IGF1/IGF1R/STAT3 signaling-inducible IFITM2 promotes gastric cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2017;393:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H., Chu A., Liu S., Yuan Y., Gong Y. Identification of DEGs and transcription factors involved in H. pylori-associated inflammation and their relevance with gastric cancer. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9223. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Liu W., Dai Y. SOCS3 and its role in associated diseases. Hum. Immunol. 2015;76:775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Jiang Z., Gu W., Han S. STROBE-clinical characteristics and prognosis factors of gastric cancer in young patients aged </=30 years. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e26336. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000026336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

De-identified 16S rRNA gene sequencing and RNA-seq data in this study have been deposited at NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Bioproject accession numbers for these datasets are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

All original code has been deposited at Zenodo and is publicly available as of the date of publication. DOIs are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.