Abstract

Zika virus (ZIKV), discovered in the Zika Forest of Uganda in 1947, is a mosquito-borne flavivirus related to yellow fever, dengue and West Nile viruses. From its discovery until 2007, only sporadic ZIKV cases were reported, with mild clinical manifestations in patients. Therefore, little attention was given to this virus before epidemics in the South Pacific and the Americas that began in 2013. Despite a growing number of ZIKV studies in the past three years, many aspects of the virus remain poorly characterized, particularly the spectrum of species involved in its transmission cycles. Here, we review the mosquito and vertebrate host species potentially involved in ZIKV vector-borne transmission worldwide. We also provide an evidence-supported analysis regarding the possibility of ZIKV spillback from an urban cycle to a zoonotic cycle outside Africa, and we review hypotheses regarding recent emergence and evolution of ZIKV. Finally, we identify critical remaining gaps in the current knowledge of ZIKV vector-borne transmission.

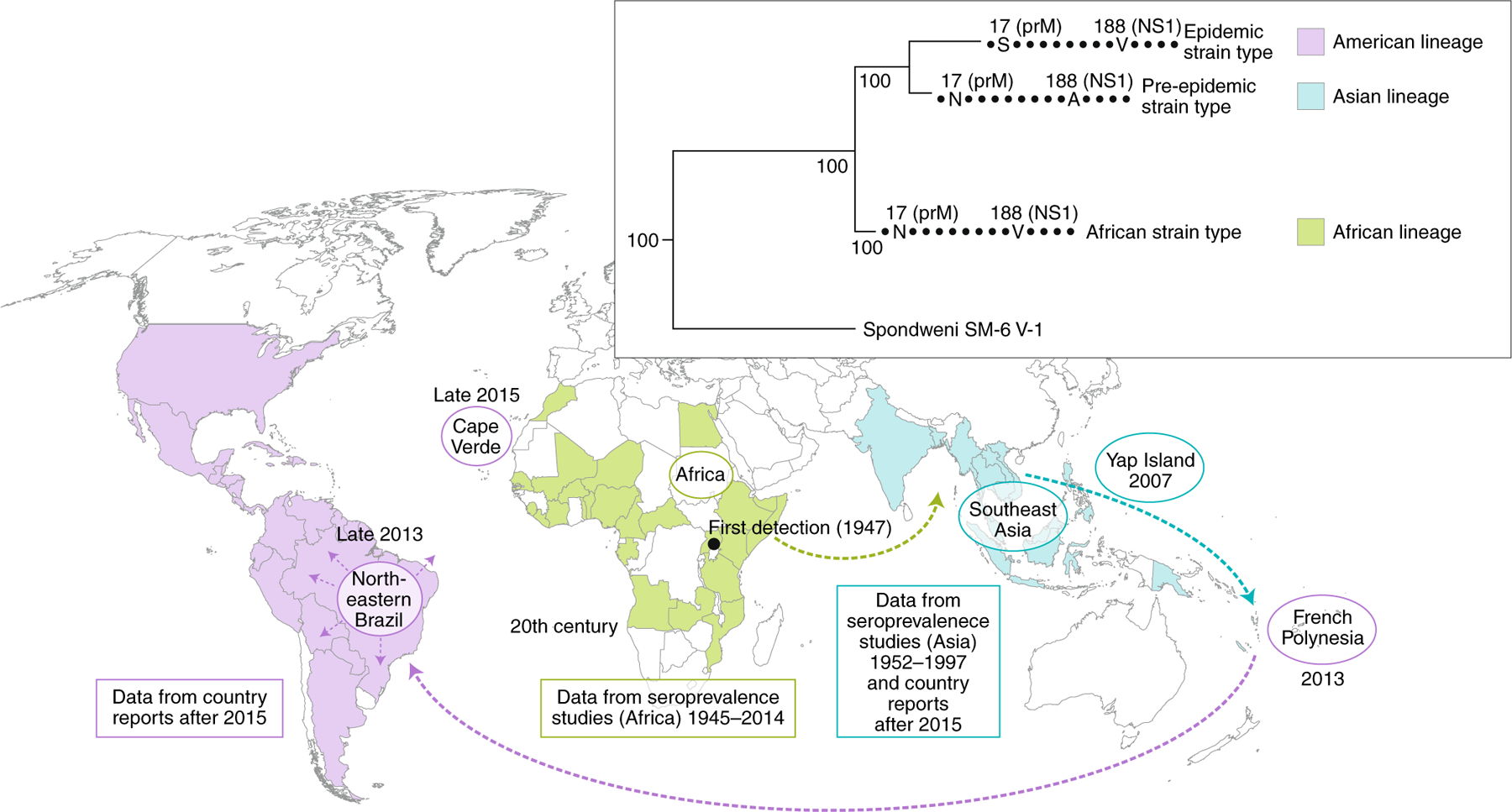

Zika virus (ZIKV) is an arthropod-borne flavivirus related to yellow fever, dengue and West Nile viruses1. ZIKV was first reported in East Africa in 1947 and expanded from the ancestral enzootic cycle in Africa to Asia several decades ago (Fig. 1). At the beginning of the 21st century, the virus expanded into the South Pacific and the Americas, triggering a pandemic that led to 48 countries reporting active ZIKV transmission by 20172. Prior to this expansion, there was little scientific research on this virus3.

Fig. 1 |. Emergence and evolution of Zika virus vector-borne transmission.

Zika virus was first detected in Uganda in 1947. Seroprevalence data suggests the virus was present in Africa and Asia starting from the 1950s and spread to the Pacific and the Americas from 2013 onwards. There are three recognized lineages of Zika virus (African lineage, green; Asian lineage, blue and American lineage, purple), characterized by key pre-epidemic and post-epidemic mutations, shown on the phylogeny.

In this paper, we review the natural history of ZIKV and the current knowledge about ZIKV vector-borne transmission and the mosquito and vertebrate host species potentially involved worldwide. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of ZIKV spillback into an enzootic cycle outside Africa and review hypotheses regarding ZIKV recent global emergence and evolution. Finally, we identify research priorities for filling remaining gaps and challenges in our understanding of ZIKV.

Zika virus natural history

The virus was first isolated from a sentinel rhesus macaque and from Aedes (Stegomyia) africanus mosquitoes in the same Ugandan location. Surveillance efforts identified immune people in at least 25 African countries from 1945 to 2014 (reviewed in ref. 4) and in 7 Asian countries or territories from 1952 to 1997 (Fig. 1). However, many of the serologic tests employed in this surveillance are cross-reactive among flaviviruses, thus these results must be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, direct detection of ZIKV in countries including Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, the Central African Republic, Uganda, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines (reviewed in ref. 5) confirmed its widespread distribution for many decades.

The first evidence of possible interhuman urban transmission came from Malaysia in 1966, when ZIKV was detected in the domesticated, anthropophilic mosquito, Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti aegypti. However, between 1966 and 2013, there was no direct evidence of ZIKV transmission by this species, which may reflect limited urban transmission or simply a lack of surveillance and diagnostics to detect endemic or epidemic circulation.

The first ZIKV outbreaks were documented in Gabon6 and Yap 7,8 in 2007. In 2013, a major outbreak started in French Polynesia involving approximately 100,000 infected persons, providing the first evidence of a severe disease, Guillain Barré syndrome, associated with ZIKV infection9. This was followed by a spread throughout the South Pacific and eventually to the Americas, where a massive epidemic ensued and congenital microcephaly was first associated with maternal ZIKV infection2 (Fig. 1). Millions of ZIKV cases have now been reported from 86 countries, including the expanded forms of congenital infection that comprise congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) and Guillain Barré syndrome10.

ZIKV vectors: evidence in the wild and from the laboratory

To properly incriminate a ZIKV vector, the virus must be isolated from field-collected mosquitoes, and laboratory studies must ascertain their ability to transmit the virus (vector competence; Supplementary Figure 1). Field surveys allow investigation of a large number of mosquito species, but do not deliver proof of transmission, because nondisseminated infections may occur or residual virus may be detected in a partially digested blood meal. Experimental vector-competence studies can demonstrate transmission potential, but practical constraints limit the number of species for which this can be performed, and competent species may not have proper contact with hosts to transmit the virus in nature. Consequently, combined information from both type of study is critical to the definition of the most plausible ZIKV vectors involved in sylvatic and urban transmission cycles (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2 |. Zika virus vector-borne transmission.

a, Horizontal transmission of ZIKV occurs in two distinct cycles: a sylvatic cycle in which the virus circulates between animal vertebrate hosts (i.e., probably nonhuman primates) and zoophilic mosquitoes, and an urban cycle in which the virus is transmitted to humans by highly anthropophilic mosquitoes (such as Ae. aegypti). b, Vector-borne transmission of ZIKV occurs via three main patterns: horizontal transmission between vertebrates and vectors, vertical transmission from and infected mosquito female to its progeny, and venereal transmission from an infected female to a mosquito male and vice versa.

Field investigations

Our literature search conducted in April 2018 reported 31 wild-caught mosquito species infected with ZIKV worldwide (Supplementary Table 1). These mosquitoes belong to five genera: Aedes (22 species), Culex (4 species), Anopheles and Eretmapodites (2 species each) and Mansonia (1 species) (Fig. 3). Among the Aedes mosquitoes, Stegomyia is the major subgenus from which ZIKV has been isolated (9 species). This distribution suggests the Aedes genus as the most important mosquito taxon involved in ZIKV transmission. Most ZIKV-infected mosquito species (25) have been caught in sylvatic settings, whereas only six species have been reported to be infected with ZIKV in urban settings: Ae. aegypti4,11–21, Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus6,12,22, Culex (Culex) quinquefasciatus15,20,23, Aedes (Aedimorphus) vexans20, Culex (Culex) coronator20 and Culex (Culex) tarsalis20. With the exception of Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, ZIKV has been detected in salivary gland pools of all of these mosquito species caught in urban settings in Mexico20. Nevertheless, the viral titers associated with these detections were often not compatible with transmission competence. To incriminate a vector, ZIKV titers consistent with transmission-competence are necessary; however, viral loads have only been measured by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) on five occasions, in Ae. aegypti, Ae. vexans, Ae. albopictus, Cx. tarsalis, Cx. coronator and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes15,16,20,22,24.

Fig. 3 |. Distribution of vector species naturally infected with Zika virus.

The colour code used for countries and territories represents the Zika virus lineages that have been epidemiologically associated with human infections in those regions.

Field collection of ZIKV-infected mosquitoes has been performed in 15 countries: 9 in epidemic regions and 6 in regions with enzootic ZIKV circulation (Fig. 3). The sylvatic species that have been more frequently found infected with ZIKV in the field are Aedes (Stegomyia) luteocephalus, Aedes (Diceromyia) furcifer, Aedes (Aedimorphus) dalzieli, Ae. aegypti, Ae. africanus, Aedes (Fredwardsius) vittatus and Aedes (Diceromyia) taylori. In urban settings, Ae. aegypti has been most frequently found ZIKV-infected and is the most widely distributed, with ZIKV detection in Africa, America, Asia and Oceania (Supplementary Table 1). Ae. africanus, Ae. furcifer and Ae. luteocephalus are also broadly distributed in Africa. Finally, 14 species have been reported as being infected with ZIKV only once: Anopheles (Cellia) gambiae s.l., Aedes (Stegomyia) apicoargenteus, Aedes (Diceromyia) flavicollis, Aedes (Neomelaniconion) taeniarostris, Eretmapodites inornatus, Eretmapodites quinquevittatus, Ae. (Neomelaniconion) jamoti, Aedes (Mucidus) grahamii, Aedes (Aedimorphus) hirsutus, Culex (Culex) perfuscus, Aedes (Stegomyia) unilineatus, Ae. vexans, Cx. coronator and Cx. tarsalis (Supplementary Table 1). Although ZIKV detection in field-collected mosquitoes does not prove their role as vectors, the distribution and frequencies of infected mosquitoes suggest that Ae. africanus, Ae. furcifer, Ae. lutocephalus, Ae. vittatus, Ae. dalzielli and Ae. taylori are involved in sylvatic ZIKV transmission cycles, and Ae. aegypti is implicated in urban ZIKV cycles. The latter is supported by anthropophilic and anthropophagic behaviours of Ae. aegypti and the high abundance of this species in urban environments nearly throughout the tropics25,26.

Vector competence

Our April 2018 literature survey identified 45 appropriate ZIKV vector-competence studies involving 25 mosquito species: 13 Aedes or Ae. (Ochlerotatus) spp. (Ochlerotatus is elevated to a genus by some authors), 8 Culex spp. and 4 Anopheles spp. (Supplementary Table 1). Eight of these species have been found to be able to transmit ZIKV in laboratory conditions, as infectious virus has been found in mosquito salivary glands or saliva: Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, Ae. vexans, Aedes (Rampamyia) notoscriptus, Aedes (Ochlerotatus) camptorhynchus, Ae. vittatus, Ae. luteocephalus and Cx. quinquefasciatus.

Among the sylvatic mosquitoes examined, Ae. vittatus and Ae. luteocephalus were found to be competent ZIKV laboratory vectors, in agreement with the high frequency and distribution of ZIKV-infected specimens from these species found in the field. This suggests their implication in sylvatic cycles in Africa. Outside Africa, many publications have recognized the roles of Aedes (Stegomyia) hensilli and Aedes (Stegomyia) polynesiensis in the Yap Island and French Polynesia ZIKV outbreaks, respectively, because of their high abundances in households7,8,27 although these species have never been found to be infected in the field4,5,28,29. Vector-competence assays have proved the ability of the two species to develop disseminated ZIKV infections, but have not confirmed transmission7,30. Thus, further studies are needed in order to fully evaluate the role Ae. hensilli and Ae. polynesiensis in urban ZIKV cycles.

The Culex spp. controversy

Despite field reports of ZIKV infection in four Culex species (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 1) and experimental oral infection assays highlighting that Cx. quinquefasciatus is susceptible to ZIKV with viral detection in saliva15,31,32, there are so far no reports of naturally infected mosquitoes during outbreaks with viral loads consistent with transmission competence. Even if the infection rates of mosquito populations in nature are very low33—meaning that ZIKV detection will be strongly dependent on the study sampling effort— the majority of field investigations in which Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes were captured did not find any ZIKV infection in this species4,6,7,14,16,21,34.

Vector-borne transmission in natural conditions (known as vectorial capacity) is also determined by the abundance of the vector and its ecological traits, which are quantitatively more important than vector competence (although competence is a requirement for transmission). This may explain why some ‘poor vectors’ can mediate outbreaks regardless of limited vector competence35. Cx. quinquefasciatus is a highly abundant species that may bite humans frequently in urban settings36, which favours the human–vector contact that is critical to vectorial capacity35 and thus, may occasionally transmit ZIKV. Nevertheless, efficient ZIKV transmission by Cx. quinquefasciatus would require sequential feedings on human hosts, and this species is more often associated with avian bloodmeals than human bloodmeals37. Taken together, the collected evidence suggests that Culex species does not play an important role on ZIKV transmission.

ZIKV vertical and venereal transmission reports

Vertical transmission of arboviruses in mosquitoes (from an infected female mosquito to her offspring) has been suggested as a mechanism that ensures maintenance of ZIKV during conditions adverse for horizontal transmission among vertebrate hosts (such as harsh winters, drought conditions and interepidemic stages limited by herd immunity), as well as a potential influence on the epidemiology of arbovirus infection38. Vertical or venereal ZIKV transmission has been demonstrated for the mosquitoes Ae. furcifer34,39, Ae. aegypti16,20 and Cx. quinquefasciatus20 under natural conditions, as adult males infected with ZIKV have been caught in the field (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, ZIKV has been detected in Ae. albopictus eggs collected in Brazil22 and in adult Aedes (Stegomyia) bromeliae, Aedes unilineatus and Ae. vittatus reared from field-collected eggs (reviewed in ref. 5), suggesting the occurrence of natural vertical transmission in these species. Experimental studies have demonstrated vertical ZIKV transmission in Ae. aegypti40–42 and Ae. alboereasve42 whereas venereal transmission has been observed in both directions (male-to-female and vice versa) in Ae. aegypti43,44 (Supplementary Table 2). These findings reveal the complexity of vector-borne ZIKV transmission dynamics (Fig. 2b). Although these intervector transmission modes guarantee the spread and maintenance of the virus in vector populations, its contribution to the mosquito–human transmission chain and epidemiology continues to be a knowledge gap, because no infectious virus has been reported in saliva of vertically or venereally infected female mosquitoes.

ZIKV potential host species

Vertebrate animals are also major players in the ZIKV maintenance in nature, as ZIKV circulates in a sylvatic transmission cycle between nonhuman primate hosts and arboreal mosquitoes in tropical Africa45 (Fig. 2a). Our literature review identified 42 publications reporting ZIKV-infected animals, in either natural or experimental conditions.

At least 79 animal species have been identified as naturally infected or experimentally susceptible to ZIKV infection (Supplementary Table 3). Mammals, and especially primates, are the most represented taxonomic group, although birds, reptiles and amphibians have also been identified, indicating the potential diversity of ZIKV hosts and the lack of a clear association between ZIKV and particular animal taxa (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 3). Among these species,63 have been found as naturally ’infected‘, whereas Macaca mulatta, Cercopithecus aethiops, Cercopithecus ascanius, Callithrix jacchus, Eidolon helvum, and Capra aegagrus have been recognized as being susceptible to ZIKV infection in both natural and experimental conditions. However, the serological assays generally used to assess ZIKV exposure and susceptibility are of limited specificity and could result in overestimation of the number of species susceptible to ZIKV infection.

Fig. 4 |. Distribution of host orders reported as susceptible to Zika virus in natural conditions.

The colour code used for countries and territories represents the Zika virus lineages that have been epidemiologically associated with human infections in those regions (serological assays have been the tests used to assess ZIKV exposure and susceptibility in 87.1% of animals sampled in the field).

The incrimination of such animals in ZIKV transmission chains (either sylvatic or urban) will depend on their viremia levels and duration, their spatial coincidence with competent ZIKV vectors and the feeding preferences of the latter. So far, viremia levels sufficient for transmission have only been detected in five monkey species (M. mulatta, C. jacchus, Macaca fascicularis, Saimiri boliviensis boliviensis and Saimiri sciureus sciureus) infected experimentally (Supplementary Table 3).

The ZIKV sylvatic transmission cycle between nonhuman hosts and arboreal mosquitoes has been most thoroughly studied in Africa (Fig. 4), and seroprevalence data suggest that nonhuman primates are important enzootic amplification hosts for ZIKV maintenance. The most intensively studied enzootic ZIKV focus is in eastern Senegal, where annual mosquito collections and periodic nonhuman primate sampling have revealed strong evidence of regular or continuous arboreal circulation. Interestingly, the same area also harbours dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever viruses with no apparent difference in nonhuman primate amplification hosts or mosquito vectors. However, whereas the latter three viruses are detected in mosquitoes only periodically in asynchronous 7–8-year cycles, ZIKV is detected more frequently (ca. 4-year cycles)39. This suggests that ZIKV may exploit additional, shorter-lived vertebrate hosts with faster turnover than the three monkey species (Chlorocebus aethiops, Erythrocebus patas and Papio papio) typically found in the Senegalese focus. Unfortunately, knowledge of animal reservoirs is lacking in regions outside Africa, as only four studies have been published on this topic: Brazil46, Pakistan47, Indonesia48 and Thailand49 (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 3). Additional research using appropriate diagnostic techniques on potential zoonotic ZIKV hosts could offer important predictive data about the possibility of enzootic establishment outside Africa. Diagnostic methods allowing determination of viral loads in vertebrate hosts should be privileged, as this information is crucial to knowing which species can generate sufficient viremia to infect mosquitoes and thus contribute to circulation.

Establishment of a ZIKV enzootic cycle in the Americas

The arboviruses yellow fever (YFV), chikungunya (CHIKV) and dengue (DENV) were introduced to the Americas following European discovery in the late 15th Century. An enzootic transmission cycle has established for YFV in the Americas50 but has not been documented for CHIKV51 and DENV52.

The recent introduction and explosive spread of ZIKV in urban and rural settings throughout the Americas begs the question of whether spillback and establishment of an enzootic ZIKV transmission cycle could occur in the Americas. Brazil is home to multiple species of primates and mosquitoes potentially capable of ZIKV transmission, although direct assessment of host competence and vector competence of New World species is currently not known. The probability of enzootic establishment is dependent on host and vector population sizes, host birth rates and the ZIKV force of infection. We urgently need investigations of the host competence of New World monkeys or other mammals to ZIKV, of the vector competence of sylvatic New World Aedes, Sabethes, and Haemagogus mosquitoes for ZIKV and of the geographic range of these potential hosts and vectors. Moreover, independent enzootic circulation is difficult to distinguish from temporary spillback from interhuman transmission unless sufficient divergence between enzootic and human strains can be detected or epizootics in nonhuman primates suggest the presence of an enzootic cycle. Nonetheless, based on the experience acquired with the enzootic transmission cycle of YFV, the establishment of a ZIKV enzootic cycle in the Americas (or in Asia) could have important implications for the ultimate control of future epidemics, as these cycles are not amenable to human intervention and control.

Transmission in neotropical sylvatic mosquito species

Transmission of ZIKV in urban settings occurs mainly via Aedes spp. mosquitoes. However, because of the invasive nature and extensive geographic distribution of Ae. albopictus in tropical as well as temperate settings, this species has the potential to become a major ZIKV vector globally. Given that it has been implicated in Asia as a bridge vector for sylvatic DENV movement into the urban cycle (reviewed in refs. 52,53), could this vector serve as the bridge to facilitate reverse spillback and establishment of an enzootic ZIKV transmission cycle in the Americas? Subsequently, a number of New World mosquitoes involved in the enzootic transmission of YFV, including Haemagogus (Haemagogus) albomaculatus, Haemagogus (Haemagogus) spegazzini, Haemagogus (Haemagogus) janthinomys, Sabethes (Sabethoides) chloropterus, Sabethes (Sabethes) albiprivus, Sabethes (Sabethoides) glaucodaemon, Sabethes (Peytonulus) soperi, and Sabethes (Sabethes) cyaneus, Psorophora (Janthinosoma) ferox and Ae. (Ochlerotatus) serratus (reviewed in ref. 53) could serve as competent enzootic vectors of ZIKV and should be evaluated experimentally.

A recent mathematical dynamic transmission model to assess the probability of establishment of a sylvatic ZIKV transmission cycle in nonhuman primates and/or other mammals, via arboreal mosquito vectors in Brazil, demonstrated a high probability of establishment of enzootic ZIKV across a large range of biologically plausible parameters: mean mosquito lifespan, mean ZIKV recovery in nonhuman primates (NHPs), mosquito vertical transmission and rate of yearly ZIKV introduction45. Whether ZIKV will emulate YFV (neotropical enzootic establishment) or DENV (lack of evidence for neotropical enzootic transmission) is an open and critical question. If ZIKV establishes a sylvatic cycle in the Americas (or in Asia), then mosquito control and even human herd immunity from vaccination (if a ZIKV vaccine becomes available) or limitation of transmission from demographic turnover will not suffice to eradicate it from the region.

Transmission in neotropical NHPs

There are more than 190 species and subspecies of nonhuman primates in South America, of which a large number live in the Amazon Basin in proximity in some cases (e.g., Saimiri) to human activities54. This diversity underscores the need for data on their susceptibility to ZIKV infection to predict potential future circulation in an enzootic cycle as well as re-emergence into the human transmission cycle.

In 2015, a serosurvey conducted in diverse ecotypes from Ceará State, Brazil, which at the time was a ZIKV-epidemic area, sampled sera and oral swabs from 15 marmosets (C. jacchus) and 9 capuchin monkeys (Sapajus libidinosus). Four ZIKV-positive samples from marmosets and three positive samples from capuchin monkeys were identified46 (Supplementary Table 3). Subsequent sequencing of amplified products indicated that they were identical to ZIKV strains circulating epidemically at the time, suggesting that they could serve as reservoirs for enzootic transmission. In addition, recent experimental ZIKV infections of marmosets reproduced key features of human ZIKV infection and viremia titers were near the necessary threshold for transmission55,56.

Another study characterized the dynamics of ZIKV infection in neotropical squirrel (Saimiri spp.) and owl monkeys (Aotus spp.)57 (Supplementary Table 3). Viremia was observed in both species in the absence of detectible disease, and seroconversion occurred by day 28. This experimental study confirms the susceptibility to ZIKV infection of two New World NHP species living in close proximity to humans in South America, suggesting that they could support a neotropical enzootic ZIKV cycle. However, it remains to be experimentally validated whether the observed viremia is sufficient to infect sympatric sylvatic mosquitoes (host competence) and whether the New World arboreal enzootic mosquitoes have the ability to become infected with ZIKV and transmit upon subsequent feedings (vector competence) to susceptible NHPs.

Zika virus recent emergence and evolution

Evolutionary studies of recent ZIKV spread.

The first direct phylogenetic studies of ZIKV were reported in 2012, when Haddow et al.58 analysed the genomic sequences of six ZIKV strains and found that they grouped by geographic origin, suggesting that African and Asian lineages diverged over long periods of isolation. Because the closest relative, Spondweni virus, is found only in Africa, the authors concluded that ZIKV originated on that continent. More extensive analyses of ZIKV strains dating from 1968 to 2002, collected in several locations of Africa, suggested at least two independent introductions into West Africa during the 20th century and the possibility of recombination there18. However, the extremely limited ZIKV sampling, especially in East Africa since the 1950s, suggests that sampling bias affects such phylogeographic analyses.

Since the arrival of ZIKV in French Polynesia and the Americas, major phylogenetic analyses using much larger strain numbers have provided detailed understanding of patterns of its spread and evolution. ZIKV was introduced from somewhere in Southeast Asia into French Polynesia, which was followed by the spread both eastward and westward in the South Pacific, presumably by infected air travellers. Introduction into the Americas from French Polynesia is estimated to have occurred in late 201359, followed by a period of undetected circulation in Northeastern Brazil in early 2014. Dissemination to other parts of the Americas occurred subsequently before the first Brazilian outbreak was detected in early 201560 (Fig. 1). The rapid spread throughout the South American continent seems to have been enhanced by the warm temperatures associated with the 2015 appearance of El Niño, perhaps through stimulation of mosquito biting rates and shortening of the ZIKV extrinsic incubation period61. The subsequent explosive spread of ZIKV throughout the Americas facilitated its spread eastward, reaching Cape Verde in late 201562. In addition, ZIKV cases have been detected in Guinea Bissau63, Angola64, Senegal and Nigeria65, but the lineage of the concerned strains has not been yet determined. The most detailed study of ZIKV introduction and spread into new territories comes from Florida in the United States, where an estimated 4–40 introductions (mainly from the Caribbean) seeded local transmission that probably began in the spring of 201666.

Emergence mechanisms of urban ZIKV transmission.

The broad distribution and abundance of Aedes spp. vectors (especially domestic Ae. aegypti)25, coupled with the inefficacy of traditional vector control measures, are key elements in ZIKV emergence67. Poverty and inadequate or damaged infrastructure, deforestation and urbanization are factors that favour mosquito larval development sites, human–mosquito contacts and thereby ZIKV transmission68,69. In addition, human movement and intercontinental air travel has expedited the spread of vector-borne diseases68,70–72. Nevertheless, the impact of these socioeconomic and environmental factors on vector-borne transmission is a common feature for all emerging mosquito-borne viruses, and they do not explain the absence of ZIKV urban epidemics before 2007.

An intuitive explanation for the emergence of urban ZIKV transmission and congenital Zika syndrome was a change in ZIKV phenotypes coincident with its spread into the South Pacific and Americas. This hypothesis was suggested following the observed vector-adaptive evolution of the Indian Ocean lineage of chikungunya virus, which allowed, for the first time, exploitation of Ae. albopictus as a major urban vector via a series of envelope glycoprotein substitutions that enhance transmission by this species73. Could a similar phenomenon explain the massive urban amplification and spread of ZIKV? Alternatively, could the pathogenicity of ZIKV have changed coincident with this spread, for example, selected by increased viremia for transmission by peridomestic mosquitoes, which might also enhance fetal infection? Comprehensive sequencing and phylogenetic studies like those above have also been used to identify recent mutations in the ZIKV genome that might be associated with altered pathogenicity or urban vector transmission to explain the explosive nature of recent outbreaks and the lack of evidence for such epidemics in the past. Two approaches have been used to determine whether such mutations, several of which were traced to ZIKV spread into the South Pacific and the Americas74, could have encoded critical phenotypes responsible for epidemic emergence and congenital disease.

Hypothetical emergence mechanism 1: adaptation for transmission by urban vectors.

Urban vector-adaptive evolution has been identified as a major factor in the emergence of two other viruses with origins in nonhuman primate-arboreal mosquito vector enzootic cycles: dengue and chikungunya viruses. Although no overall increase in urban vector transmission efficiency has been linked to emergence of the human transmission cycle75, the Asian lineage of dengue virus-2 (DENV-2) evolved for more efficient transmissibility by Ae. aegypti76, and this phenotype has been linked to its replacement of the less transmissible and less human-virulent American DENV-2 genotype77.

A mechanism for subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA)-mediated enhancement of flavivirus transmission by mosquitoes has also been suggested78. Substitutions in the 3′ UTR (untranslated region) from the DENV genome have led to higher amounts of sfRNA in Ae. aegypti salivary glands, which resulted in increased DENV infection rates and loads, as well as suppression of mosquito immune response in in this latter organ79. Similar results have been obtained using the West Nile virus-Culex pipiens model80, suggesting a potential role of sfRNA produced by the host metabolic machinery as a driver for ZIKV transmission.

The most striking example of vector-adaptive evolution by an arbovirus is CHIKV repeated emergence events and spread since 2004. One explanation for this dramatic spread is the adaptation via a series of mutations81 of one CHIKV strain, the Indian Ocean Lineage, for efficient midgut infection and transmission by the highly invasive mosquito Ae. albopictus, never before implicated as an important vector. Surprisingly, these mutations have little or no impact on infection of the primary vector Ae. aegypti in most locations and do not affect infection of Ae. albopictus in the genetic backbone of CHIKV strains circulating in the Americas73.

The first evidence of potential Ae. aegypti-adaptive ZIKV evolution came from work examining the flavirirus nonstructural glycoprotein NS1 substitution that enhances infection of this species82. Starting with natural isolates that differ by an alanine versus a valine residue at position 188 showed that a strain encoding valine imported to China from the Americas generated higher levels of NS1 in the blood of infected mice as well as in the supernatant of infected cell lines. The strain encoding V188 also infects the Rockefeller colony of Ae. aegypti more efficiently, and NS1 spiked into artificial bloodmeals recapitulates this finding. However, other studies with ZIKV strains differing in these NS1 residues have not revealed comparable differences83,84. Additional studies with wild mosquito populations (the Rockefeller colony is many decades old, and colonization is known to affect the susceptibility of mosquitoes to arboviruses) are needed to further evaluate the importance of NS1 change. Interestingly, the V188 residue is also present in African ZIKV strains, suggesting it was lost upon the introduction into Asia many decades ago, possibly the result of a founder effect.

Hypothetical emergence mechanism 2: ZIKV adaptive evolution in vertebrate hosts.

Vertebrate-adaptive evolution has been identified as a possible factor in the emergence of DENV. Southeast Asian genotype of serotype 2 and genotype III of serotype 3 have been associated with higher viremias in humans, leading to severe dengue disease and higher transmission rates by susceptible Aedes spp. mosquitoes77,85–88. Duplication of an adaptable RNA element has been suggested as a possible mechanism of sustaining high viral fitness for a virus that cycles between hosts89. However, when mechanisms of human DENV emergence due to host range expansion of sylvatic strains by adaptation to use humans as reservoirs (via increased magnitude of replication) were evaluated in two surrogate models of human infection, there were no significant differences, suggesting that the historical emergence of DENV from the ancestral sylvatic transmission cycle into human cycles may not have required adaptation to replicate in humans as reservoir hosts90. In a similar manner, the rate of evolutionary change and pattern of natural selection are similar among endemic and sylvatic DENV, suggesting that the dynamics of mutation, replication and selection are broadly equivalent for DENV across its host range91, and thus the potential for additional zoonotic virus emergence into the human transmission cycle is high.

The explosive global spread of ZIKV has been hypothesized to be attributed to adaptive evolution for efficient urban transmission in humans. A number of phylogenetic studies59,92 have suggested that adaptive evolution may have occurred in Southeast Asia. The Asian ZIKV lineage may have adapted to generate higher viremia levels in humans, leading to increased efficiencies in mosquito infection, transmission and spread. Higher viremia could then enhance transplacental transmission in humans, which could explain the dramatic emergence of microcephaly in the Americas. Some bioinformatic studies suggested an increase in the use of human codons by the virus, which may support the notion of adapted evolution in humans18,93,94. In addition, one study95 showed that a single serine-to-asparagine substitution (Ser17→Asn17 (S17N))in the ZIKV structural protein prM increased infectivity in both human and mouse neural progenitor cells, leading to more severe microcephaly in the mouse fetus. However, this potential link will require comprehensive longitudinal studies in humans and/or animal models, which will be difficult to test, because various animal models may not respond to ZIKV infection in the same manner as humans. To date, the lack of solid evidence of adaptive evolution in humans suggests that a combination of stochastic factors and selective evolution may have contributed to ZIKV’s global emergence and spread.

Conclusion

Ae. aegypti is the principal vector in urban ZIKV transmission worldwide, whereas other broadly distributed Aedes species may act as ZIKV vectors in specific environments where their abundance is important. However, information about ZIKV titers in mosquitoes consistent with transmission competence is still scarce, resulting in difficulty to assess their specific roles in transmission. Another important knowledge gap that deserves more investigation concerns the contribution of vertical and venereal transmission in mosquito–human transmission.

The NHPs are the most important enzootic amplification hosts for ZIKV maintenance in the sylvatic cycle, although other orders of animal species appear to be susceptible to ZIKV infection. However, there is scarce information on the viremia levels that these potential hosts can develop, which limits complete comprehension of their contribution to ZIKV transmission. In addition, the knowledge of sylvatic specieś competence (both vectors and hosts) to transmit ZIKV in the Americas and Asia is still limited. Despite these gaps, the evidence collected in the wild and in the lab suggest a high probability of establishment of enzootic ZIKV in the Americas, which could make impossible its eradication from the region. Finally, the conducted studies regarding ZIKV-adaptive evolution in vectors and vertebrate hosts suggest that a combination of stochastic factors and Darwinian evolution may have contributed to ZIKV’s global emergence and spread.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work has been notably supported by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) from the World Health Organization (Grant 2017/713047-0). The European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and innovation programme under “ZIKALLIANCE” (Grant Agreement no. 734548) partially supported A.V.-R. and R.L.d.O. The Programme Opérationnel FEDER-Guadeloupe-Conseil Régional 2014–2020 (Grant 2015-FED-192) partially supported A.V.-R. NIH grants R24 AI120942 and U01 AI115577 provided a partial support for N.V. and S.C.W.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0836-z.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Dick GWA Zika virus. II. Pathogenicity and physical properties. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 46, 521–534 (1952). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan American Health Organization. Regional Zika Epidemiological Update (Americas) August 25, 2017 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Pulgarin DF, Acevedo-Mendoza WF, Cardona-Ospina JA, Rodríguez-Morales AJ & Paniz-Mondolfi AE A bibliometric analysis of global Zika research. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 14, 55–57 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musso D & Gubler DJ Zika Virus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 29, 487–524 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer S, Calvez E, Chouin-Carneiro T, Diallo D & Failloux AB An overview of mosquito vectors of Zika virus. Microbes Infect. 20, 646–660 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grard G et al. Zika virus in Gabon (Central Africa) – 2007: a new threat from Aedes albopictus? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2681 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ledermann JP et al. Aedes hensilli as a potential vector of Chikungunya and Zika viruses. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e3188 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy MR et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 2536–2543 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oehler E et al.ZikavirusinfectioncomplicatedbyGuillain-Barre syndrome–case report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Euro Surveill. 19, 7–9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organisation. Zika Virus (ZIKV) Classification Table 15th February. Who 1–2 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchette NJ, Garcia R & Rudnick A Isolation of Zika virus from Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Malaysia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 18, 411–415 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singapore Zika Study Group. Outbreak of Zika virus infection in Singapore: an epidemiological, entomological, virological, and clinical analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, 813–821 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutebi JP et al. Zika virus MB16–23 in mosquitoes, Miami-Dade County, Florida, USA, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 808–810 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerbois M et al. Outbreak of Zika virus infection, Chiapas State, Mexico, 2015, and first confirmed transmission byAedes aegypti mosquitoes in the Americas. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 1349–1356 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guedes DRD et al. Zika virus replication in the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus in Brazil. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 6, e69 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira-de-Brito A et al. First detection of natural infection of Aedes aegypti with Zika virus in Brazil and throughout South America. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 111, 655–658 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayllón T et al. Early evidence for zika virus circulation among Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 1411–1412 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faye O et al. Molecular evolution of Zika virus during its emergence in the 20th century. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2636 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akoua-Koffi C et al. Investigation autour d’un cas mortel de fièvre jaune en Côte d’Ivoire en 1999. Bull Soc. Pathol. Exot. 94, 227–230 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elizondo-Quiroga D et al. Zika virus in salivary glands of five different species of wild-caught mosquitoes from Mexico. Sci. Rep. 8, 809 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yee DA, Dejesus-Crespo R, Hunter FF & Bai F Assessing natural infection with Zika virus in the southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, during 2016 in Puerto Rico. Med. Vet. Entomol. 32, 255–258 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smartt CT et al. Evidence of Zika virus RNA fragments in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) field-collected eggs from Camaçari, Bahia, Brazil.J. Med. Entomol. 54, 1085–1087 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song S et al. Could Zika virus emerge in Mainland China? Virus isolation from nature in Culex quinquefasciatus, 2016. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 6, e93 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Díaz-Quiñonez JA et al. Evidence of the presence of the Zika virus in Mexico since early 2015. Virus Genes 52, 855–857 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraemer MUG et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. eLife 4, e08347 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie SA In Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever, 2nd Edition. (eds Gubler DJ, Ooi EE, Vasudevan S & Farrar J) 455–480 (CAB International, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musso D, Nilles EJ & Cao-Lormeau VM Rapid spread of emerging Zika virus in the Pacific area.Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, O595–O596 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magalhaes T, Foy BD, Marques ETA, Ebel GD & Weger-Lucarelli J Mosquito-borne and sexual transmission of Zika virus: recent developments and future directions. Virus Res. 254, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ioos S et al. Current Zika virus epidemiology and recent epidemics. Med. Mal. Infect. 44, 302–307 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richard V, Paoaafaite T & Cao-Lormeau VM Vector competence of French Polynesian Aedes aegypti and Aedes polynesiensis for Zika virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0005024 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo XX et al. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus: a potential vector to transmit Zika virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 5, e102 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smartt CT, Shin D, Kang S & Tabachnick WJ Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) From Florida transmitted Zika virus. Front. Microbiol. 9, 768 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day JF Predicting St. Louis encephalitis virus epidemics: lessons from recent, and not so recent, outbreaks. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 46, 111–138 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diallo D et al. Zika virus emergence in mosquitoes in southeastern Senegal, 2011. PLoS One 9, e109442 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller BR, Monath TP, Tabachnick WJ & Ezike VI Epidemic yellow fever caused by an incompetent mosquito vector. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 40, 396–399 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandes RS et al. Culex quinquefasciatus from Rio de Janeiro is not competent to transmit the local Zika virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0004993 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Rejon JE et al. Host-feeding preference of the mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, in Yucatan State, Mexico. J. Insect Sci. 10, 32 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lequime S, Paul RE & Lambrechts L Determinants of arbovirus vertical transmission in mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005548 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Althouse BM et al. Impact of climate and mosquito vector abundance on sylvatic arbovirus circulation dynamics in Senegal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92, 88–97 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thangamani S, Huang J, Hart CE, Guzman H & Tesh RB Vertical transmission of Zika virus in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95, 1169–1173 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li CX et al. Vector competence and transovarial transmission of two Aedes aegypti strains to Zika virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 6, e23 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciota AT, Bialosuknia SM, Ehrbar DJ & Kramer LD Vertical transmission of Zika virus by Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 880–882 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campos SS et al. Zika virus can be venereally transmitted between Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Parasit. Vectors 10, 605 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira-Silva JW et al. First evidence of Zika virus venereal transmission in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, 56–61 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Althouse BM et al. Potential for Zika virus to establish a sylvatic transmission cycle in the Americas. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0005055 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Favoretto S et al. First detection of Zika virus in neotropical primates in Brazil: a possible new reservoir. bioRxiv 10.1101/049395 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Darwish MA, Hoogstraal H, Roberts TJ, Ahmed IP & Omar F A sero-epidemiological survey for certain arboviruses (Togaviridae) in Pakistan. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77, 442–445 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olson JG et al. A survey for arboviral antibodies in sera of humans and animals in Lombok, Republic of Indonesia. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 77, 131–137 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joob B & Wiwanitkit V Immunological reactive rate to Zika virus in canine sera: a report from a tropical area and concern on pet, zoonosis and reservoir host. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 10, 208–209 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryant JE, Holmes EC & Barrett ADT Out of Africa: a molecular perspective on the introduction of yellow fever virus into the Americas. PLoS Pathog. 3, e75 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volk SM et al. Genome-scale phylogenetic analyses of chikungunya virus reveal independent emergences of recent epidemics and various evolutionary rates. J. Virol. 84, 6497–6504 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vasilakis N, Cardosa J, Hanley KA, Holmes EC & Weaver SC Fever from the forest: prospects for the continued emergence of sylvatic dengue virus and its impact on public health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 532–541 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hanley KA et al. Fever versus fever: the role of host and vector susceptibility and interspecific competition in shaping the current and future distributions of the sylvatic cycles of dengue virus and yellow fever virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 19, 292–311 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rylands AB & Mittermeier RA in South American Primates, Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects (eds Garber PA, Estrada A, Bicca-Marques JC, Hetmann EW & Strier KB) 23–55 (Springer, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seferovic M et al. Experimental Zika virus infection in the pregnant common marmoset induces spontaneous fetal loss and neurodevelopmental abnormalities. Sci. Rep. 8, 6851 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiu CY et al. Experimental Zika virus inoculation in a new world monkey model reproduces key features of the human infection. Sci. Rep. 7, 17126 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vanchiere JA et al. Experimental Zika virus infection of neotropical primates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98, 173–177 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haddow AD et al. Genetic characterization of Zika virus strains: geographic expansion of the Asian lineage. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1477 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Faria NR et al. Zika virus in the Americas: early epidemiological and genetic findings.Science 352, 345–349 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Faria NR et al. Establishment and cryptic transmission of Zika virus in Brazil and the Americas. Nature 546, 406–410 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caminade C et al. Global risk model for vector-borne transmission of Zika virus reveals the role of El Niño 2015. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 119–124 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lourenço J et al. Epidemiology of the Zika virus outbreak in the Cabo Verde Islands, West Africa. PLoS Curr. 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.19433b1e4d007451c691f138e1e67e8c (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosenstierne MW et al. Zika virus IgG in infants with microcephaly, Guinea-Bissau, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 948–950 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kraemer MUG et al. Zika virus transmission in Angola and the potential for further spread to other African settings. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 111, 527–529 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herrera BB et al. Continued transmission of Zika virus in Humans in West Africa, 1992–2016. J. Infect. Dis. 215, 1546–1550 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grubaugh ND et al. Genomic epidemiology reveals multiple introductions of Zika virus into the United States. Nature 546, 401–405 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fernández-Salas I et al. Historical inability to control Aedes aegypti as a main contributor of fast dispersal of chikungunya outbreaks in Latin America. Antiviral Res. 124, 30–42 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ali S et al. Environmental and social change drive the explosive emergence of Zika virus in the Americas. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005135 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reina Ortiz M et al. Post-earthquake Zika virus surge: disaster and public health threat amid climatic conduciveness. Sci. Rep. 7, 15408 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harrington LC et al. Dispersal of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti within and between rural communities. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 72, 209–220 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stoddard ST et al. House-to-house human movement drives dengue virus transmission. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 994–999 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bogoch II et al. Potential for Zika virus introduction and transmission in resource-limited countries in Africa and the Asia-Pacific region: a modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 1237–1245 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsetsarkin KA, Chen R & Weaver SC Interspecies transmission and chikungunya virus emergence. Curr. Opin. Virol 16, 143–150 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pettersson JHO et al. How did zika virus emerge in the Pacific Islands and Latin America? MBio 7, 1–6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vasilakis N et al. Sylvatic dengue viruses share the pathogenic potential of urban/endemic dengue viruses. J. Virol. 84, 3726–3728 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Armstrong PM & Rico-Hesse R Differential susceptibility ofAedes aegypti to infection by the American and Southeast Asian genotypes of dengue type 2 virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 1, 159–168 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cologna R, Armstrong PM & Rico-Hesse R Selection for virulent dengue viruses occurs in humans and mosquitoes. J. Virol. 79, 853–859 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yeh SC & Pompon J Flaviviruses produce a subgenomic flaviviral RNA that enhances mosquito transmission. DNA Cell Biol. 37, 154–159 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pompon J et al. Dengue subgenomic flaviviral RNA disrupts immunity in mosquito salivary glands to increase virus transmission. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006535 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Göertz GP et al. Noncoding subgenomic flavivirus RNA is processed by the mosquito RNA interference machinery and determines West Nile Virus transmission by Culex pipiens mosquitoes. J. Virol. 90, 10145–10159 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsetsarkin KA et al. Multi-peaked adaptive landscape for chikungunya virus evolution predicts continued fitness optimization inAedes albopictus mosquitoes. Nat. Commun. 5, 4084 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu Y et al. Evolutionary enhancement of Zika virus infectivity in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Nature 545, 482–486 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weger-Lucarelli J et al. Vector competence of American mosquitoes for three strains of Zika virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0005101 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roundy CM et al. Variation in Aedes aegypti mosquito competence for Zika virus transmission. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 625–632 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Libraty DH, Pichyangkul S, Ajariyakhajorn C, Endy TP & Ennis FA Human dendritic cells are activated by dengue virus infection: enhancement by gamma interferon and implications for disease pathogenesis. J. Virol. 75, 3501–3508 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vaughn DW et al. Dengue viremia titer, antibody response pattern, and virus serotype correlate with disease severity. J. Infect. Dis. 181, 2–9 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Messer WB, Gubler DJ, Harris E, Sivananthan K & de Silva AM Emergence and global spread of a dengue serotype 3, subtype III virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9, 800–809 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang WK et al. High levels of plasma dengue viral load during defervescence in patients with dengue hemorrhagic fever: implications for pathogenesis. Virology 305, 330–338 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Villordo SM, Filomatori CV, Sánchez-Vargas I, Blair CD & Gamarnik AV Dengue virus RNA structure specialization facilitates host adaptation. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004604 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vasilakis N et al. Potential of ancestral sylvatic dengue-2 viruses to re-emerge. Virology 358, 402–412 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vasilakis N et al. Evolutionary processes among sylvatic dengue type 2 viruses. J. Virol. 81, 9591–9595 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weaver SC et al. Zika virus: history, emergence, biology, and prospects for control. Antiviral Res. 130, 69–80 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang H, Liu S, Zhang B & Wei W Analysis of synonymous codon usage bias of zika virus and its adaption to the hosts. PLoS One 11, e0166260 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Butt AM, Nasrullah I, Qamar R & Tong Y Evolution of codon usage in Zika virus genomes is host and vector specific.Emerg. Microbes Infect. 5, e107 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yuan L et al. A single mutation in the prM protein of Zika virus contributes to fetal microcephaly. Science 358, 933–936 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.