Abstract

Background

During general anaesthesia for noncardiac surgery, there remain knowledge gaps regarding the effect of goal-directed haemodynamic therapy on patient-centred outcomes.

Methods

Included clinical trials investigated goal-directed haemodynamic therapy during general anaesthesia in adults undergoing noncardiac surgery and reported at least one patient-centred postoperative outcome. PubMed and Embase were searched for relevant articles on March 8, 2021. Two investigators performed abstract screening, full-text review, data extraction, and bias assessment. The primary outcomes were mortality and hospital length of stay, whereas 15 postoperative complications were included based on availability. From a main pool of comparable trials, meta-analyses were performed on trials with homogenous outcome definitions. Certainty of evidence was evaluated using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE).

Results

The main pool consisted of 76 trials with intermediate risk of bias for most outcomes. Overall, goal-directed haemodynamic therapy might reduce mortality (odds ratio=0.84; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64 to 1.09) and shorten length of stay (mean difference=–0.72 days; 95% CI, –1.10 to –0.35) but with low certainty in the evidence. For both outcomes, larger effects favouring goal-directed haemodynamic therapy were seen in abdominal surgery, very high-risk surgery, and using targets based on preload variation by the respiratory cycle. However, formal tests for subgroup differences were not statistically significant. Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy decreased risk of several postoperative outcomes, but only infectious outcomes and anastomotic leakage reached moderate certainty of evidence.

Conclusions

Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy during general anaesthesia might decrease mortality, hospital length of stay, and several postoperative complications. Only infectious postoperative complications and anastomotic leakage reached moderate certainty in the evidence.

Keywords: fluid, general anaesthesia, goal-directed haemodynamic therapy, haemodynamics, perioperative care, postoperative complications, stroke volume

Editor's key points.

-

•

Previous systematic reviews have shown that perioperative, goal-directed, haemodynamic therapy might reduce postoperative complications. It is not clear how patient and procedure heterogeneity or recent publications affect these findings.

-

•

This comprehensive systematic review found that goal-directed, haemodynamic therapy during general anaesthesia for noncardiac surgery reduced postoperative pneumonia, surgical site infection, and anastomotic leakage (with moderate certainty in the evidence). The effects on mortality and hospital length of stay were unclear.

-

•

Large clinical trials are needed to examine the effect on mortality and hospital length of stay. At least three such trials are currently ongoing.

Worldwide, more than 300 million major surgeries are conducted each year1 with the vast majority of these requiring general anaesthesia. Although general anaesthesia is generally considered safe, certain patients are at a higher risk of intra- and postoperative complications and mortality. Common postoperative complications include infection, bleeding, cardiac complications, pulmonary complications, acute kidney injury, and delirium.2, 3, 4, 5

To minimise these risks, clinicians provide intraoperative interventions with the aim of obtaining specific physiological, respiratory, and haemodynamic targets. Yet, little is known about which targets are optimal for which patients in which types of surgery; this limits the possibility of clear guidelines and there are differences in treatment protocols from hospital to hospital. Hence, there is a strong need for evidence-based intraoperative targets.

Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy (GDHT) – sometimes just called goal-directed therapy6 – is the use of a protocol to standardise haemodynamic targets and the treatments used to reach these targets. GDHT most often refers to optimisation of flow-related parameters such as cardiac output or stroke volume,7,8 and optimisation will most often involve fluid therapy and the term goal-directed fluid therapy is therefore also used.9, 10, 11 Systematic reviews have generally found that GDHT reduces hospital length of stay9,12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and overall postoperative complication rate,7,9,14, 15, 16,18, 19, 20 whereas estimates on mortality7,12,13,16,18,19,21, 22, 23 and organ-specific complications9,13,14,16,20,22, 23, 24, 25, 26 tend to favour GDHT with varying precision. Yet, there may be problems with heterogeneity in outcome definitions: although one review did select studies for meta-analyses based on specific definitions of pulmonary outcomes,17 other reviews included all outcome definitions. On the contrary, a 2018 review found all included GDHT trials too heterogeneous to perform any meta-analysis on any outcome.6

This comprehensive systematic review aims to describe the literature on intraoperative GDHT. When deemed appropriate, meta-analyses will be performed on a wide range of patient-centred outcomes while exploring potential heterogeneity. The goal is to provide an overview for clinicians involved in patient care and for researchers to guide future work.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol for the current review is provided in Supplementary Content S1. The protocol was prospectively uploaded to Figshare (figshare.com) on June 11, 2020 and updated on August 19, 2020. The reporting of this systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.27 The PRISMA checklist is provided in Supplementary Content S2, section ‘PRISMA-checklist’.

Eligibility criteria and outcomes

This review was part of a larger review project including trials of adult patients undergoing noncardiac surgery with general anaesthesia and mechanical ventilation. The project investigates whether the use of specific intraoperative physiologic targets improves patient-centred postoperative outcomes. Trials involving very short durations of anaesthesia (e.g. for electroconvulsive therapy), Caesarean sections, or procedures with one-lung ventilation were not included. All years, but only English language publications, were included.

This particular article focuses on trials of GDHT during general anaesthesia, that is trials investigating treatment protocols designed to reach one or more specific haemodynamic targets. There were no limits on the type of haemodynamic variable, nor the type of device used to measure it. Accepted comparators were other treatment protocols or standard care. Trials comparing different fluid strategies without specific targets were not included. Trials solely focusing on blood pressure targets are traditionally not considered GDHT and were not included in this review.

Included trials had to report at least one patient-centred postoperative outcome, meaning clinical outcomes considered directly related to patient morbidity or mortality. We considered mortality and hospital length of stay as the primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes were pneumonia, pulmonary oedema, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, acute kidney injury, surgical site infection, ileus, anastomotic leakage, and delirium. These postoperative outcomes were prioritised based on the available outcomes reported in the included trials. We also extracted data on combined pulmonary complications, acute lung injury, combined cardiac complications, and combined abdominal complications, but these outcomes were not considered further primarily because of incomparable outcome definitions. There were no limits on an individual trial's definitions of the outcomes, but definitions were noted for each outcome in each trial to enable assessment of heterogeneity.

Information sources and search strategy

On July 24, 2020, and again on March 8, 2021, we searched PubMed and Embase. The search included a combination of various text and indexing search terms for general anaesthesia or surgery and various haemodynamic and respiratory targets. To identify randomised trials, the Cochrane sensitivity-maximising search strategy was used.28 The search strategy for each database is provided in the protocol. The reference lists of included articles and recent systematic reviews were reviewed for potential additional articles.

To identify registered ongoing or unpublished trials, we searched the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov on April 5, 2021, and again on June 28, 2021. Additional details are provided in Supplementary Content S2, section ‘Ongoing randomized clinical trials’.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts retrieved from the systematic searches. The kappa values for inter-observer variance were calculated. Relevant titles and abstracts were independently assessed in full text by two reviewers. For ongoing randomised clinical trials, two reviewers independently screened titles and trial registrations for relevant articles.

In all steps, any disagreement regarding eligibility was resolved via discussion between the reviewers and a third investigator as needed.

Data collection

Two reviewers extracted data from individual articles using a predefined standardised data extraction form. Any discrepancies in the extracted data were identified and resolved via discussion. All GDHT protocol targets and interventions were only noted if they were different from the comparator, for example if both groups used vasopressors to reach a mean arterial pressure of ≥65 mm Hg, then mean arterial pressure was not considered a GDHT target and vasopressors were not considered a GDHT intervention.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias for individual trials using version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials.29 Disagreements were resolved via discussion. Risk of bias was assessed for each outcome within a trial but is reported at the trial level as the highest risk of bias across all outcomes. If the bias was different for different outcomes, this was noted. Additional considerations about bias assessment are provided in Supplementary Content S2, section ‘Risk of bias assessment’.

Data synthesis

Trials were evaluated for clinical heterogeneity (i.e. population, intervention, comparator, and outcome) and methodological heterogeneity to determine whether they could be combined in meta-analyses. Additional details are provided in Supplementary Content S2, sections ‘Pooling of trials based on heterogeneity’ and ‘Outcomes: Definitions, data synthesis, and sensitivity analyses’.

To ensure comparability of the intervention and comparator, we made the following choices regarding articles considered for meta-analyses: First, we excluded GDHT protocols without a fluid therapy intervention as almost all trials had one or more targets related to fluid therapy. Second, the haemodynamic target determining fluid therapy was limited to those either directly or indirectly related to stroke volume, and the target cut-off had to be comparable with the majority of the literature. Third, we only included standard care comparators meaning that treatment was either at the discretion of the clinical team or based on standard monitoring targets such as mean arterial pressure, heart rate, central venous pressure, and/or urinary output.

For heterogeneity of outcome definitions, we did the following: when reported definitions were homogenous, all trials – including those with no reported definition – were pooled for the primary analysis; when reported definitions were heterogeneous, comparable definitions were selected from those trials that reported one. When possible, guidelines-based definitions (e.g. EPCO 201530) were prioritised.

Based on data availability, several post-hoc subgroup analyses were performed. Subgroup analyses of abdominal vs non-abdominal surgery (≥50% vs <50%) were performed for all outcomes with ‘abdominal’ meaning any surgery within the abdominal cavity including retroperitoneal surgery. For the primary outcomes mortality and hospital length of stay, we also performed subgroup analyses by risk of surgery (‘moderate risk’, ‘high risk’, and ‘very high risk’), open vs laparoscopic surgery (≥50% vs <50%), GDHT protocol concept of preload variation (the respiratory cycle vs fluid challenges), GDHT protocol use of vasopressors, inotropes (none vs any), or both, by intraoperative fluid volume difference between the GDHT and standard care group (‘≤–500 ml’ vs ‘similar fluid volumes’ vs ‘≥500 ml’), type of device (noninvasive techniques vs pulse contour analysis vs oesophageal Doppler monitoring), and finally type of fluid (crystalloids vs colloids). Details on subgroup definitions are provided in Supplementary Content S2, section ‘Subgroup definitions’. For each outcome, sensitivity analyses – as described in Supplementary Content S2, section ‘Outcomes: Definitions, data synthesis, and sensitivity analyses’ – were also performed. Meta-regressions were performed for the primary outcomes mortality and hospital length of stay to evaluate effect modification by selected continuous variables. Only comparisons with at least 10 trials were considered. Selected potential modifiers were median year of patient inclusion, duration of surgery, and sample size, and control group mortality and hospital length of stay as a reflection of the illness severity in the underlying trial population. The latter two analyses should be interpreted with caution because of the potential for regression to the mean.31,32 Results are presented in a table and visually using bubble plots.

For binary outcomes, we conducted meta-analyses and meta-regressions using Peto's method for odds ratios (ORs) because many trials had few or zero events in one of the groups.33,34 Results from these analyses are reported as ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) with values <1 indicating better outcomes in the GDHT group. DerSimonian and Laird random-effects meta-analyses were used for continuous outcomes. Results from these analyses are presented as mean differences with 95% CIs with values <0 indicating better outcomes in the GDHT group. To allow for meta-analyses, continuous outcomes reported as a median with a measure of variance (e.g. quartiles) were transformed to a mean and a standard deviation using the method described by Shi and colleagues.35 Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using forest plots and I2 statistics. To test for subgroup differences, we calculated P-values using Cochrane's Q statistics.36 For trials with multiple GDHT allocations, the number of controls was evenly spread among these groups if included in the same meta-analysis.

To assess for potential publication bias for the primary outcomes, funnel plots were created and visually interpreted.

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The certainty of the overall evidence for a given comparison was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology and classified within one of four categories: very low, low, moderate, or high certainty of evidence.37 GRADEpro (McMaster University, 2020) was used for drafting of the GRADE tables.

Results

Overview

The search identified 23 454 unique records, of which 534 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 95 trials were identified (eFig. 1). Six additional trials were identified in bibliographies, yielding a total of 101 trials. Three trials had two GDHT groups giving a total of 104 GDHT-allocations, which will be referred to as ‘trials’ in the following. The search for registered ongoing or unpublished trials identified 53 trials (eTable 1).

Fifteen trials compared two different GDHT protocols and did not include a standard care comparator; no meaningful meta-analyses were possible for these trials, and they are only reported descriptively (eTable 2). A further 13 trials were excluded from all meta-analyses because of incomparable interventions: non-stroke volume-related GDHT-target (n=7), supranormal or restrictive GDHT-targets (n=5), and GDHT-protocol without any fluid intervention (n=1) (eTable 2).

The remaining 76 trials, which compared GDHT with standard care, represented 9081 patients; from this pool, trials with comparable outcomes were included in meta-analyses. Details on the included GDHT protocols are provided in Table 1, whereas characteristics on included trials are provided in eTable 3. There was some heterogeneity among the included trials, for example in inclusion years (1988–2020), types of surgery, concepts of preload variation, and reported outcomes. Each trial's reported outcomes are presented in eTable 4.

Table 1.

Overview of goal-directed haemodynamic therapy (GDHT) protocols. CFT, corrected flow time (s); CI, cardiac index (L min−1 m−2); CNAP, continuous noninvasive arterial pressure; CVC, central venous catheter; CVP, central venous pressure (mm Hg); DO2, oxygen delivery (ml min−1 m−2); E/e′ ratio, ratio between diastolic peak mitral inflow velocity and early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity; ELWI, extravascular lung water index (ml kg−1); GDHT, goal-directed haemodynamic therapy; GEDWI, global end-diastolic volume index (ml m−2); HES, hydroxyethyl starch; HPI: Hypotension Prediction Index (score: 0–100%); HR, heart rate (min−1); IBP, invasive blood pressure; LiDCO, lithium dilution cardiac output; LVEDP, left ventricular end diastolic pressure (mm Hg); LVOT-VTI, left ventricular outflow tract velocity time integral (cm s−1); NICOM, noninvasive cardiac output monitoring; NR, not reported; O2ER, oxygen, extraction ratio (VO2 DO2−1); ODM, oesophageal Doppler monitoring; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; PAOP, pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (mm Hg); PCA–, pulse contour analysis without calibration (devices with autocalibration included here); PCA+, pulse contour analysis with calibration (thermodilution or lithium); PI, perfusion index (%); PiCCO, pulse contour cardiac output; PPV, pulse pressure variation (%); PVI; pleth variability index (0–100%); ScvO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation (%); StO2, oxygen saturation (%); SV, stroke volume (ml s−1); ΔSV, Delta stroke volume (%); SVI, stroke volume index (ml min−1 m−2); ΔSVI, Delta stroke volume index (%); SVR, systemic vascular resistance (dyn s cm−5); SVV, stroke volume variation (%); UO, urinary output (ml kg−1 or ml kg−1 h−1); VO2, oxygen consumption (ml min−1 m−2).

| First author, year of publication | Type of device to measure target | Device brand | GDHT targets | Fluid therapy to reach target (bolus amount, type) | Vasoactive drugs to reach target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoemaker, 198838 | PAC | NR | CI 2.8–3.5 DO2 400–550 VO2 120–140 |

NR | Norepinephrine, dopamine, dobutamine |

| Bender, 199739 | PAC | NR | PAOP 8–14 CI >2.8 SVR <1100 |

NR, crystalloids | Dopamine, nitroprusside |

| Sinclair, 199740 | ODM | ODM2 monitor, Abbott | CFT 0.36–0.40 ΔSV <10 |

3 ml kg−1, HES | None |

| Conway, 200241 | ODM | NR | CFT >0.35 ΔSV <10 |

3 ml kg−1, HES | None |

| Gan, 200242 | ODM | Deltex | CFT >0.35 ΔSV <10 |

200 ml, HES | None |

| Venn, 200243 | ODM | Deltex | CFT >0.4 ΔSV <10 |

100–200 ml, gelatine | NR |

| Wakeling, 200544 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | ΔSV <10 | 250 ml, gelatine | None |

| Noblett, 200645 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | CFT >0.35 ΔSV <10 |

7 ml kg−1, gelatine | None |

| Lopes, 200746 | PCA– | IBPplus monitor | PPV <10 | NR, HES | None |

| Buettner, 200847 | PCA+ | PiCCO Plus monitor | SBP variation <10% | NR, crystalloid or HES | None |

| Harten, 200848 | PCA+ | LiDCO plus | PPV <10 | 250 ml, HES | None |

| Senagore, 200949 | ODM | Deltex | ΔSV <10 | 200 ml, HES or 300 ml, crystalloid | None |

| Benes, 201050 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 1.10, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <10 ΔCI <10 CI >2.5 |

3 ml kg−1, HES | Dobutamine |

| Forget, 201051 | PCA– | Masimo V7.1.1.5 with Datex S/5 monitor | PVI <13 | 250 ml, HES | None |

| Mayer, 201052 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | CI >2.5 MAP >65 SVI >35 SVV <12 |

500 ml, crystalloid or 250 ml, colloid | Norepinephrine, dobutamine |

| Van der Linden, 201053 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 1.07, Edwards Lifesciences | CI >2.5 | 250 ml, HES | Dobutamine |

| Challand, 201154 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | ΔSV <10 | 200 ml, HES | None |

| Pillai, 201155 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | ΔSV <10 CFT >0.35 |

3 ml kg−1, NR | None |

| Brandstrup, 201256 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | ΔSV <10 | 200 ml, HES | None |

| Zhang, 201257 | PCA– | Datex Ohmeda S/5 monitor | PPV <12 | 250 ml, crystalloid | None |

| Bisgaard, 201358 | PCA+ | LIDCOplus | SVI >10 | 250 ml, HES | None |

| Bundgaard-Nielsen, 201359 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | ΔSV <10 | 3 ml kg−1, HES | None |

| El Sharkawy, 201360 | ODM | EDM | CFT >0.35 ΔSV <10 |

200 ml, HES | None |

| McKenny, 201361 | ODM | EDM | ΔSV <10 | 3 ml kg−1, HES | None |

| Ramsingh, 201262 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 3.02, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <13 | 250 ml, albumin | None |

| Salzwedel, 201363 | PCA– | ProAQT, Pulsion Medical Systems | PPV <10 CI >2.5 |

NR | Norepinephrine, ephedrine |

| Scheeren, 201364 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <10 ΔSV <10 |

200 ml, HES | None |

| Srinivasa, 201365 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | CFT 0.35–40 ΔSV <10 |

3–7 ml kg−1, colloids | None |

| Zakhaleva, 201366 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | CFT >0.35 ΔSV <10 |

3–7 ml kg−1, NR | None |

| Zheng, 201367 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | CI >2.5 SVI >35 SVV <12 MAP >65 |

200–250 ml colloid/500 ml crystalloid | Norepinephrine, dopamine |

| Pearse, 201468 | PCA+ | LiDCO Rapid | ΔSV <10 | 250 ml, colloid not further specified | None |

| Peng, 201469 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 3.0, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <10 | 4 ml kg−1, HES | None |

| Pestaña, 201470 | Bioreactance | NICOM, Cheetah Medical | MAP >65 CI >2.5 ΔSV <10 |

250 ml, HES or gelatine | Norepinephrine, dobutamine |

| Phan, 201471 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | SVI >35 CFT >0.36 ΔSV <10 |

250 ml, HES, gelatine, or albumin | None |

| Shillcutt, 201472 | ODM | Phillips CX50 | LVOT-VTI 16–25 LVEDP 5–12 E/e′ ratio 4–8 Systolic divided by diastolic pulmonary vein flow velocity >1 |

NR | None |

| Benes, 201573 | Noninvasive finger-pulse contour analysis | CNSystems with Ultraview SL2700 monitor, Spacelabs Healthcare | PPV <13 | 3 ml kg−1, NR | None |

| Colantonio, 201574 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 1.14, Edwards Lifesciences | CI >2.5 SVI >35 SVV <15 |

250 ml, HES | Dopamine |

| Correa-Gallego, 201575 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <2 standard deviations from baseline | 250 ml, albumin | None |

| Funk, 201576 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <13 CI >2.2 MAP >60 |

250 ml, HES | Norepinephrine, phenylephrine |

| Jammer, 201577 | PCA+ | LiDCO rapid | ΔSV <10 SVV <10 |

6 ml kg−1, Ringer's acetate | None |

| Kumar, 201578 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | CI >2.5 O2ER ≤27 SVV <10 |

500 ml, crystalloid or 250 ml, HES | Norepinephrine, dopamine, dobutamine |

| Lai, 201579 | PCA+ | LiDCO rapid | SVV <10 ΔSV <10 |

50–200 ml, gelatine | None |

| Broch, 201680 | Noninvasive finger-pulse contour analysis | Nexfin, Edwards Lifescience | PPV <10 CI >2.5 |

500 ml, crystalloid or colloid | Dobutamine, epinephrine, phenylephrine |

| Hand, 201681 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences with EV-1000 monitor | MAP >75 or <10% from baseline SVV <13 CI >3 SVR >800 |

250 ml, NR | Dobutamine, epinephrine, phenylephrine |

| Kumar, 201682 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 3.0, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <10 | NR, Lactated Ringer's, NaCl, HES | Norepinephrine |

| Schmid, 201683 | PCA+ | PiCCO2, Pulsion Medical Systems | GEDVI 640–800 CI >2.5 MAP >70 ELWI <10 |

500 ml, HES | Norepinephrine, dobutamine |

| Elgendy, 201784 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 1.14, Edwards Lifesciences | CI >2.5 SVV <12 MAP >65 |

3 ml kg−1, HES | Norepinephrine, dobutamine |

| Gómez-Izquierdo, 201785 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | ΔSV <10 | 200 ml, HES and Ringer's | None |

| Liang, 201786 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV 8–13 DO2 >500 |

200 ml, HES | None |

| Luo, 201787 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | MAP >65 CI >2.5 SVV <15 |

200 ml, HES or gelatine | Physician's choice |

| Reisinger, 201788 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | ΔSVI <10 | 250 ml, HES | None |

| Stens, 201789 | Noninvasive finger-pulse contour analysis | ccNexfin (noninvasive) | PPV <12 CI >2.5 MAP >70 |

500 ml, Lactated Ringer's 250 ml, colloid subsequently |

Dobutamine |

| Weinberg, 201790 | PCA– | FloTrac 4.0 with EV1000 monitor | SVV <20 MAP within 20% of baseline CI >2.0 |

250 ml, crystalloid | NR |

| Wu, 201791 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 3.02, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <12 CI >2.5 |

50 ml, HES | None |

| Calvo-Vecino, 201892 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | SVV <10 CI >2.5 MAP >65 |

250 ml, crystalloid and HES | Norepinephrine, dobutamine |

| Kaufmann, 201893 | ODM | Deltex | ΔSV <10 MAP >70 CI >2.5 |

200 ml, crystalloid | Norepinephrine, ephedrine |

| Kim, 201894 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <12 MAP ≥65 CI >2.5 |

200 ml, HES | Norepinephrine, ephedrine, dobutamine |

| Yin, 201895 | Bioreactance | NICOM, Cheetah Medical | CI 2.5–4.0 SVV <13 |

250 ml, HES | Dobutamine |

| Zhang, 201896 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV 9–14 ΔSV <10 |

200 ml, HES | None |

| Zhao, 20188 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <13 ΔSV <10 |

250 ml, HES or crystalloid | None |

| Cesur, 201897 | Pleth curve analysis | Masimo Radical 7 monitor | PVI <13 MAP >65 |

250 ml, gelatine | Ephedrine |

| Davies, 201998 | Noninvasive finger-pulse contour analysis | ClearSight (Nexfin), Edwards Lifesciences | ΔSV <10 MAP within 30% of baseline |

250 ml, Hartmanns solution or Lactated Ringer's | Phenylephrine, metaraminol, ephedrine |

| Godai, 201999 | Pleth curve analysis and PCA– | Life Scope J, Nihon Koden | PI <5 PPV <13 |

250 ml, HES | Phenylephrine, dobutamine |

| Hasanin, 2019100 | Pleth curve analysis | GE Solar 8000 M/I monitor | PPV <13 | 3 ml kg−1, Ringer's | Ephedrine |

| Liu, 2019101 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <13 CI 2.5–4.0 |

200 ml, colloid | Dobutamine |

| Sujatha, 2019 – SVV arm102 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo 3.0, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV <13 | 200 ml, HES | None |

| Sujatha, 2019 – PVI arm102 | Pleth curve analysis | Masimo Radical 7 monitor | PVI <13 | 200 ml, HES | None |

| Szturz, 2019103 | ODM | Cardio-Q-ODM monitor | CI >2.5 CFT >0.33 Peak velocity >70 m−1 |

300 ml, PlasmaLyte | Norepinephrine, dobutamine |

| Weinberg, 2019104 | PCA– | FloTrac 4.0 with EV1000 monitor | SVV <20 MAP within 20% of baseline CI >2.2 |

250 ml, crystalloid or albumin | NR |

| Arslan-Carlon, 2020105 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | ΔSV <10 SVV <13 |

250 ml, crystalloid or albumin | NR |

| De Cassai, 2020106 | Pleth curve analysis | MostCare-UP – Endless version | PPV <13 | NR, NaCl | None |

| Fischer, 2020107 | Pleth curve analysis | Masimo Radical 7 monitor | PVI <13 | 3 ml kg−1, gelatine | Ephedrine, Norepinephrine |

| Iwasaki, 2020108 | PCA– | FloTrac Vigileo, Edwards Lifesciences | SVV 10–13 | 250–500 ml, crystalloid | None |

| Nicklas, 2020109 | PCA– | ProAQT, Pulsion Medical Systems | ΔCI <15% and >baseline CI | 500 ml, crystalloid or colloid | Dobutamine |

| Schneck, 2020110 | PCA– | FloTrac 4.0 with EV1000 monitor | HPI <80 SVV <12 CI >baseline CI MAP <70 |

250 ml, HES or gelatine | Norepinephrine, dobutamine |

| Diaper, 2020111 | PCA+ | LiDCO | ΔSVI <10 PPV <10 |

250 ml, Ringerfundin or colloid | None |

We were able to extract data on intraoperative fluid volume difference in 56 (74%) trials: GDHT as compared with standard care resulted in similar (within 500 ml) intraoperative fluid volumes in 35 (62%) trials, greater (>500 ml) in 10 (18%) trials, and lesser (<–500 ml) in 11 (20%) trials (eFig. 2). A total of 51 (91%) trials reported a difference within 1000 ml.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias within the individual trials is presented in eTable 5. Risk of bias was intermediate for most trials primarily because of a lack of blinding of the clinician performing the intervention. In most trials, the risk of bias was the same across all outcomes.

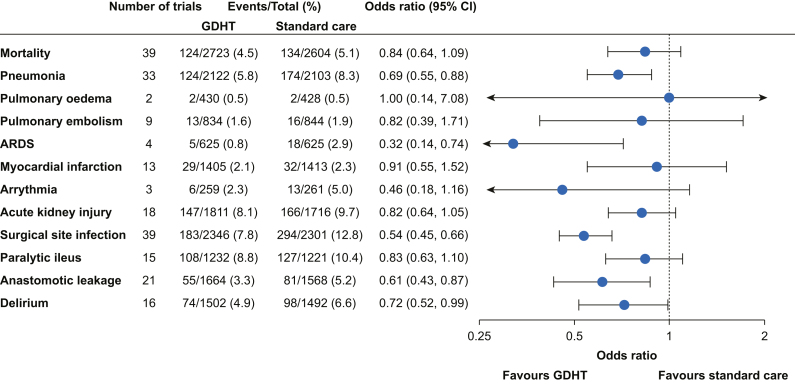

Mortality, primary result

Fifty (66%) of the included trials reported mortality; 39 of these also reported a time frame, of which 37 were in-hospital, 28-day, or 30-day mortality. Because of these relatively homogeneous time frames, meta-analysis was considered for all 50 trials; however, 11 trials were not included in the meta-analysis because of zero events in both groups. GDHT resulted in reduced mortality but with some imprecision (OR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.64–1.09; Fig. 1, eFig. 3). Results were similar when excluding trials with high risk of bias and when excluding two trials that only reported ICU mortality and 180-day mortality, respectively (eTable 6; eFigs 4 and 5).

Fig 1.

Overall results for all binary outcomes. Results from meta-analyses comparing GDHT with standard care for all binary outcomes. Estimates are odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Number of trials included in the analyses and patients with events vs totals are reported for both GDHT and standard care groups. Figures of individual forest plots are shown in eFigures 3, 6, 37, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 53, 55, 59, 62, and 65. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI, confidence interval; GDHT, goal-directed haemodynamic therapy.

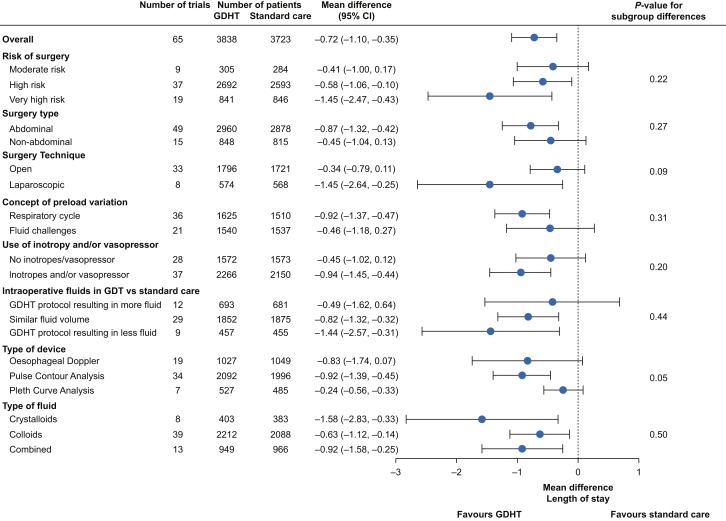

Hospital length of stay, primary result

Sixty-five (86%) of the included trials reported hospital length of stay, of which 40 had their medians and measures of variance converted to means and standard deviations. The definitions of hospital length of stay were homogeneous, and the meta-analysis thus included all 65 trials. GDHT resulted in overall shorter hospital length of stay (mean difference=–0.72 days; 95% CI, –1.10 to –0.35; eFig. 6). Results were similar when excluding trials with high risk of bias and when excluding trials with hospital length of stay >20 days in the control group (eTable 6; eFigs 7 and 8).

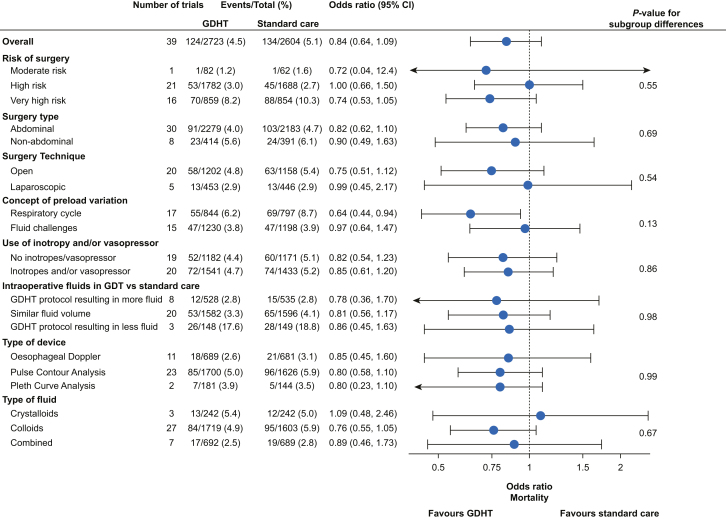

Subgroup analyses, meta-regression, and funnel plots for mortality and hospital length of stay

Subgroup analyses for mortality and hospital length of stay are summarised in Fig 2, Fig 3, respectively – a detailed description is provided in eTables 7 and 8, whereas forest plots for individual analyses are presented in eFigures 9–16 and 17–24. Results from meta-regressions for both outcomes are reported in eTable 9, whereas forest plots for individual analyses are given in eFigures 25–29 and 30–34 for mortality and hospital length of stay, respectively.

Fig 2.

Subgroup results for mortality. Subgroup results from meta-analyses comparing GDHT with standard care for mortality. Estimates are odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Number of trials included in the analyses and patients with events vs totals are reported for both GDHT and standard care groups in all subgroups. P-values for formal test of subgroup differences are presented in the rightmost column. Definitions of all subgroups are provided in Supplementary Content S2. Figures of individual forest plots are shown in eFigures 9–16. CI, confidence interval; GDHT, goal-directed haemodynamic therapy.

Fig 3.

Subgroup results for hospital length of stay. Subgroup results from meta-analyses comparing GDHT with standard care for hospital length of stay. Estimates are mean differences with 95% confidence intervals. Number of trials included in the analyses and number of patients are reported for both GDHT and standard care groups in all subgroups. P-values for formal test of subgroup differences are presented in the rightmost column. Definitions of all subgroups are provided in Supplementary Content S2. Figures of individual forest plots are shown in eFigures 17–24. CI, confidence interval; GDHT, goal-directed haemodynamic therapy.

There was no clear difference in the effect of GDHT on mortality or hospital length of stay according to all subgroups (all P-values for subgroup differences >0.05). Estimates for very high-risk surgery, abdominal surgery, and GDHT targets based on preload variation by the respiratory cycle showed a larger effect of GDHT for both outcomes – however, all confidence intervals had considerable overlap with their comparators.

Meta-regression showed increased absolute reduction in hospital length of stay by GDHT with increasing length of stay in the control group (eFig. 34). There were no clear effect measure modifications in the remaining meta-regression analyses.

Funnel plots for mortality and hospital length of stay showed no clear signs of publication bias (eFigs 35 and 36).

Postoperative complications

For postoperative complications, details on outcome definitions and data synthesis are given in Supplementary Content S2, section ‘Outcomes: Definitions, data synthesis, and sensitivity analyses’. A detailed summary of the results from the primary analyses and sensitivity analyses is provided in eTable 6, whereas individual forest plots are provided in eFigures 37–67.

Except for pulmonary oedema, which showed neutral results (eFig. 43), point estimates favoured GDHT for all postoperative complications. However, only pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, surgical site infection, anastomotic leakage, and delirium had estimates where the 95% CIs did not include 1 (Fig. 1). As compared with the primary analyses, there was no clear different effect of GDHT on any postoperative complication when grouped by abdominal surgery vs non-abdominal surgery (eFigs 37, 41, 45, 47, 49, 53, 55, 59, 62, and 65).

Sensitivity analyses on postoperative complications generally showed similar results with their primary analyses although point estimates varied, especially for outcomes with few included trials or patients (eFigs 38–40, 42, 44, 46, 48, 50–52, 54, 56–58, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, and 67). Including all trials that reported pulmonary oedema gave a more precise and larger risk reductive effect of GDHT on the outcome but led to moderate inconsistency in the estimates (I2=47%) (eFig. 42). For delirium, a sensitivity analysis only including three trials with the EPCO 2015 definition30 showed a stronger effect favouring GDHT (eFig. 67).

GRADE assessment

GRADE assessment is presented in Table 2. For all outcomes, the certainty in the evidence was downgraded owing to risk of bias. The primary outcomes mortality and hospital length of stay were classified as low level of certainty because of imprecision and inconsistent estimates, respectively. The level of certainty was moderate for pneumonia, surgical site infection, and anastomotic leakage, which all had consistent estimates favouring GDHT and relatively narrow CIs with large sample sizes. Certainties for other postoperative complications were either very low or low.

Table 2.

GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations). ∗The majority of the trials were rated as having an intermediate risk of bias. †The 95% confidence interval includes both potential benefit and no effect. ‡Substantial heterogeneity (I2=78%), but few trials showing harm. ¶Wide 95% confidence interval including both potential benefit and harm. §Optimal information size not reached, see Supplementary Content S2. ||Confidence interval includes both benefit and harm. #Moderate inconsistency (I2=41%). CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; MD, mean difference.

| Certainty assessment |

Number of patients (events/total (%) or n) |

Effect |

Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of trials | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other | Goal-directed therapy | Standard of care | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | |

| Mortality | |||||||||||

| 39 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Serious† | None | 124/2723 (4.6%) | 134/2604 (5.1%) | OR 0.84 (0.64–1.09) | 8 fewer per 1000 (from 18 fewer to 4 more) | ⊕⊕◯ ◯ LOW |

| Hospital length of stay | |||||||||||

| 65 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Serious‡ | Not serious | Not serious | None | 3838 | 3723 | – | MD 0.7 days fewer (1.1 fewer to 0.4 fewer) | ⊕⊕◯ ◯ LOW |

| Pneumonia | |||||||||||

| 33 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 124/2122 (5.8%) | 174/2103 (8.3%) | OR 0.69 (0.55–0.88) | 24 fewer per 1000 (from 35 fewer to 9 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ MODERATE |

| Pulmonary oedema | |||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious¶ | None | 2/430 (0.5%) | 2/428 (0.5%) | OR 1.00 (0.14–7.08) | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 4 fewer to 27 more) | ⊕◯ ◯ ◯ VERY LOW |

| Pulmonary embolism | |||||||||||

| 9 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious¶ | None | 13/834 (1.6%) | 16/844 (1.9%) | OR 0.82 (0.39–1.71) | 3 fewer per 1000 (from 11 fewer to 13 more) | ⊕◯ ◯ ◯ VERY LOW |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Serious§ | None | 5/625 (0.8%) | 18/625 (2.9%) | OR 0.32 (0.14–0.74) | 19 fewer per 1000 (from 25 fewer to 7 fewer) | ⊕⊕◯ ◯ LOW |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||||||||

| 13 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Serious|| | None | 29/1405 (2.1%) | 32/1413 (2.3%) | OR 0.91 (0.55–1.52) | 2 fewer per 1000 (from 10 fewer to 11 more) | ⊕⊕◯ ◯ LOW |

| Arrhythmia | |||||||||||

| 3 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Serious|| | None | 6/259 (2.3%) | 13/261 (5.0%) | OR 0.46 (0.18–1.16) | 26 fewer per 1000 (from 40 fewer to 8 more) | ⊕⊕◯ ◯ LOW |

| Acute kidney injury | |||||||||||

| 18 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Serious# | Not serious | Serious† | None | 147/1760 (8.4) | 166/1663 (10.0) | OR 0.83 (0.65–1.06) | 16 fewer per 1000 (from 33 fewer to 5 more) | ⊕◯ ◯ ◯ VERY LOW |

| Surgical site infection | |||||||||||

| 39 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 183/2346 (7.8%) | 294/2301 (12.8%) | OR 0.54 (0.45–0.66) | 54 fewer per 1000 (from 66 fewer to 40 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ MODERATE |

| Paralytic ileus | |||||||||||

| 15 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Serious† | None | 108/1232 (8.8%) | 127/1221 (10.4%) | OR 0.83 (0.63–1.10) | 16 fewer per 1000 (from 36 fewer to 9 more) | ⊕⊕◯ ◯ LOW |

| Anastomotic leakage | |||||||||||

| 21 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 55/1664 (3.3%) | 81/1568 (5.2%) | OR 0.61 (0.43–0.87) | 19 fewer per 1000 (from 29 fewer to 6 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ MODERATE |

| Delirium | |||||||||||

| 16 | RCTs | Serious∗ | Not serious | Not serious | Serious† | None | 74/1502 (4.9%) | 98/1492 (6.6%) | OR 0.72 (0.52–0.99) | 18 fewer per 1000 (from 30 fewer to 1 fewer) | ⊕⊕◯ ◯ LOW |

Discussion

In this comprehensive systematic review, GDHT as compared with standard care, used during general anaesthesia for adult patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, resulted in reduced mortality and hospital length of stay – however, the estimates were imprecise and the overall certainty in the evidence was low. GDHT reduced the risk of pneumonia, surgical site infection, and anastomotic leakage (moderate certainty in evidence). Point estimates from meta-analyses also favoured GDHT for other postoperative complications but the certainty in the evidence was very low to low. Our findings support that GDHT may reduce postoperative complication rates, especially infections and anastomotic leakage, but whether it reduces mortality or shortens hospital length of stay remains uncertain and will require evidence from larger trials. Although meta-regression did not find any association between study size and effect size, it is of note that none of the trials including more than 200 patients had an overall mortality estimate favouring GDHT.

A potential mechanism of a beneficial effect of GDHT cannot be determined from the current review. We found that the average volume of fluid used in the GDHT and control groups in the included trials were relatively similar with 91% of the trials reporting a difference within 1000 ml. However, it is possible that the goals used in GDHT allow for a more individualised approach such that some patients benefit with fluid optimisation and increased cardiac output, whereas others avoid excessive fluid administration and therefore have a decreased risk of tissue oedema, which could potentially lead to a decreased risk of outcomes such as pneumonia, surgical site infection, and anastomotic leakage.

The included trials were heterogeneous. Although the authors of a previous review concluded that no meaningful meta-analysis could be conducted because of heterogeneity,6 we instead explored the potential importance of this heterogeneity through extensive subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses, and meta-regression. Although there were certain population subgroups where GDHT appeared to be more beneficial (e.g. abdominal surgery, very high-risk surgery), these findings are very uncertain as formal statistical tests for subgroup differences were not statistically significant. We also explored whether heterogeneity in the GDHT protocol could influence the effect. There were some signals that GDHT protocols with targets based on preload variation by the respiratory cycle demonstrated better outcomes, but, again, this result should be interpreted carefully as the test for subgroup differences did not reach statistical significance. There were no clear indications that other elements of the GDHT protocol (e.g. use of vasoactive drugs, the amount/type of fluid) modified the effect. The results were generally consistent across multiple sensitivity analyses. Heterogeneity is unavoidable in any meta-analysis, but it is still reasonable to conduct meta-analyses as long as this heterogeneity does not influence the effect of the intervention (i.e. that there is no effect measure modification). With that said, the results of our meta-analyses should be interpreted carefully within this context. With the availability of additional larger trials in the future, it might be possible to further explore this heterogeneity and determine whether there are certain subgroups that benefit with greater certainty or whether certain elements of the GDHT protocol result in better outcomes.

Given the nature of GDHT, it is practically impossible to blind the clinical team performing the intervention. It was therefore not possible to determine whether the two treatment groups received comparable treatment outside the protocol. As such, all the included trials were rated as having an intermediate risk of bias owing to a lack of blinding of the clinical team. Future trials should focus on blinding personnel not directly involved in the intervention, including outcome assessors. Strict adherence to pre-defined outcome definitions would also lower the potential risk of bias and allow for more homogenous comparisons.

This systematic review identified 104 clinical trials assessing various aspects of GDHT, of which 76 specifically compared a GDHT protocol including fluid therapy to optimise stroke volume (or a related parameter) to standard of care. Despite this large number of trials, the 76 trials only included 9081 patients. For inclusion in meta-analyses, the number of patients ranged from 310 patients to 5406 patients depending on the outcome. This illustrates two points. First, the majority of the trials were small with only 10 trials including more than 200 patients and only one trial including more than 500 patients. Second, many trials did not report patient-centred outcomes such as mortality, hospital length of stay, and postoperative complications (eTable 4). No trial reported health-related quality of life, nor did we identify any study assessing cost-effectiveness of a GDHT protocol. Future trials should include multicentre collaborations to increase the sample size and focus on outcomes that are relevant for both clinicians and patients. Such trials are currently on the way (eTable 1).112, 113, 114

This review has several strengths. We conducted a comprehensive and updated search and adhered to standard methodology including risk of bias assessment and GRADE evaluation. We provide detailed information on the included trials and performed extensive subgroup and sensitivity analyses on a wide range of patient-centred outcomes to an extent not included in previous reviews.

The review also has several limitations. As noted, the included trials were generally small and heterogeneous with many trials reporting zero or few outcome events. This makes valid meta-analyses difficult.33,34 Also, continuous outcomes reported as a median with a measure of variance (e.g. quartiles) were transformed to a mean and a standard deviation, which could result in some mis-estimation. The relatively low number of included patients also limits our statistical power, especially for subgroup analyses and meta-regressions. Lastly, given the many small trials and sometimes poor reporting, it was difficult to identify all relevant trials as reflected in a relatively low agreement between reviewers. Although we also reviewed references of included trials, previous systematic reviews, and trial registration sites, it is possible that we might have missed some relevant trials.

In adult noncardiac surgery, GDHT during general anaesthesia might reduce mortality, hospital length of stay, and the risk of several postoperative complications. However, although a reduction in pneumonia, surgical site infection, and anastomotic leakage reached moderate certainty in the evidence, it was very low or low for most outcomes.

Authors' contributions

Study conception and design: LWA, AG, MJH

Data acquisition: all authors.

Data analysis: MKJ, MFV, LWA

Data interpretation: all authors.

Drafting the manuscript: MKJ, MFV, LWA

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors.

All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interests.

Protocol registration

Version 1 (June 11, 2020): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12464366.v1.

Version 2 (August 19, 2020): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12826595.v1.

Handling editor: Jonathan Hardman

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.10.046.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Weiser T.G., Haynes A.B., Molina G., et al. Size and distribution of the global volume of surgery in 2012. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94:201–209F. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.159293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global patient outcomes after elective surgery: prospective cohort study in 27 low-, middle- and high-income countries. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:601–609. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biccard B.M., Madiba T.E., Kluyts H.L., et al. Perioperative patient outcomes in the African Surgical Outcomes Study: a 7-day prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2018;391:1589–1598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gleason L.J., Schmitt E.M., Kosar C.M., et al. Effect of delirium and other major complications on outcomes after elective surgery in older adults. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:1134–1140. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt E.M., Saczynski J.S., Kosar C.M., et al. The Successful Aging after Elective Surgery (SAGES) study: cohort description and data quality procedures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2463–2471. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufmann T., Clement R.P., Scheeren T.W.L., Saugel B., Keus F., van der Horst I.C.C. Perioperative goal-directed therapy: a systematic review without meta-analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62:1340–1355. doi: 10.1111/aas.13212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ripollés J., Espinosa A., Martínez-Hurtado E., et al. Intraoperative goal directed hemodynamic therapy in noncardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2016;66:513–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao G., Peng P., Zhou Y., Li J., Jiang H., Shao J. The accuracy and effectiveness of goal directed fluid therapy in plateau-elderly gastrointestinal cancer patients: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11:8516–8522. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan J., Sun Y., Pan C., Li T. Goal-directed fluid therapy for reducing risk of surgical site infections following abdominal surgery — a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2017;39:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rollins K., Mathias N., Lobo D. Meta-analysis of goal-directed fluid therapy using transoesophageal Doppler monitoring in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. BJS Open. 2019;3:606–616. doi: 10.1002/bjs5.50188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronhjort M., Wall O., Nyberg E., et al. Impact of hemodynamic goal-directed resuscitation on mortality in adult critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Monit Comput. 2018;32:403–414. doi: 10.1007/s10877-017-0032-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grocott M.P., Dushianthan A., Hamilton M.A., Mythen M.G., Harrison D., Rowan K. Perioperative increase in global blood flow to explicit defined goals and outcomes following surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD004082. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004082.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Som A., Maitra S., Bhattacharjee S., Baidya D.K. Goal directed fluid therapy decreases postoperative morbidity but not mortality in major non-cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Anesth. 2017;31:66–81. doi: 10.1007/s00540-016-2261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benes J., Giglio M., Brienza N., Michard F. The effects of goal-directed fluid therapy based on dynamic parameters on post-surgical outcome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2014;18:584. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0584-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michard F., Giglio M.T., Brienza N. Perioperative goal-directed therapy with uncalibrated pulse contour methods: impact on fluid management and postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:22–30. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng S., Yang S., Xiao W., Wang X., Yang K., Wang T. Effects of perioperative goal-directed fluid therapy combined with the application of alpha-1 adrenergic agonists on postoperative outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18:113. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0564-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odor P.M., Bampoe S., Gilhooly D., Creagh-Brown B., Moonesinghe S.R. Perioperative interventions for prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;368:m540. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton M.A., Cecconi M., Rhodes A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of preemptive hemodynamic intervention to improve postoperative outcomes in moderate and high-risk surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1392–1402. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181eeaae5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger M.M., Gradwohl-Matis I., Brunauer A., Ulmer H., Dünser M.W. Targets of perioperative fluid therapy and their effects on postoperative outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2015;81:794–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ripollés-Melchor J., Espinosa Á., Martínez-Hurtado E., et al. Perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy in noncardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2016;28:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurgel S.T., do Nascimento P., Jr. Maintaining tissue perfusion in high-risk surgical patients: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1384–1391. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182055384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messina A., Robba C., Calabrò L., et al. Association between perioperative fluid administration and postoperative outcomes: a 20-year systematic review and a meta-analysis of randomized goal-directed trials in major visceral/noncardiac surgery. Crit Care. 2021;25:43. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giglio M., Dalfino L., Puntillo F., Brienza N. Hemodynamic goal-directed therapy and postoperative kidney injury: an updated meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23:232. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2516-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dushianthan A., Knight M., Russell P., Grocott M.P. Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy (GDHT) in surgical patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of GDHT on post-operative pulmonary complications. Perioper Med (Lond) 2020;9:30. doi: 10.1186/s13741-020-00161-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalfino L., Giglio M.T., Puntillo F., Marucci M., Brienza N. Haemodynamic goal-directed therapy and postoperative infections: earlier is better. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15:R154. doi: 10.1186/cc10284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arulkumaran N., Corredor C., Hamilton M.A., et al. Cardiac complications associated with goal-directed therapy in high-risk surgical patients: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:648–659. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins J., Thomas J., Chandler J., et al. 2020. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions.www.training.cochrane.org/handbook Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins J., Sterne J., Savović J., et al. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD201601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jammer I., Wickboldt N., Sander M., et al. Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: a statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:88–105. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharp S.J., Thompson S.G., Altman D.G. The relation between treatment benefit and underlying risk in meta-analysis. BMJ. 1996;313:735–738. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reade M.C., Delaney A., Bailey M.J., Angus D.C. Bench-to-bedside review: avoiding pitfalls in critical care meta-analysis—funnel plots, risk estimates, types of heterogeneity, baseline risk and the ecologic fallacy. Crit Care. 2008;12:220. doi: 10.1186/cc6941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sweeting M.J., Sutton A.J., Lambert P.C. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Stat Med. 2004;23:1351–1375. doi: 10.1002/sim.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradburn M.J., Deeks J.J., Berlin J.A., Russell Localio A. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of the performance of meta-analytical methods with rare events. Stat Med. 2007;26:53–77. doi: 10.1002/sim.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi J., Luo D., Weng H., et al. Optimally estimating the sample standard deviation from the five-number summary. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11:641–654. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins J., Green S. 2011. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [Updated March 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoemaker W.C., Appel P.L., Kram H.B., Waxman K., Lee T.S. Prospective trial of supranormal values of survivors as therapeutic goals in high-risk surgical patients. Chest. 1988;94:1176–1186. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.6.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bender J.S., Smith-Meek M.A., Jones C.E. Routine pulmonary artery catheterization does not reduce morbidity and mortality of elective vascular surgery: results of a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1997;226:229–236. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00002. discussion 36–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinclair S., James S., Singer M. Intraoperative intravascular volume optimisation and length of hospital stay after repair of proximal femoral fracture: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1997;315:909–912. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7113.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conway D.H., Mayall R., Abdul-Latif M.S., Gilligan S., Tackaberry C. Randomised controlled trial investigating the influence of intravenous fluid titration using oesophageal Doppler monitoring during bowel surgery. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:845–849. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gan T.J., Soppitt A., Maroof M., et al. Goal-directed intraoperative fluid administration reduces length of hospital stay after major surgery. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:820–826. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venn R., Steele A., Richardson P., Poloniecki J., Grounds M., Newman P. Randomized controlled trial to investigate influence of the fluid challenge on duration of hospital stay and perioperative morbidity in patients with hip fractures. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:65–71. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakeling H.G., McFall M.R., Jenkins C.S., et al. Intraoperative oesophageal Doppler guided fluid management shortens postoperative hospital stay after major bowel surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:634–642. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noblett S.E., Snowden C.P., Shenton B.K., Horgan A.F. Randomized clinical trial assessing the effect of Doppler-optimized fluid management on outcome after elective colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1069–1076. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopes M.R., Oliveira M.A., Pereira V.O., Lemos I.P., Auler J.O., Jr., Michard F. Goal-directed fluid management based on pulse pressure variation monitoring during high-risk surgery: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2007;11:R100. doi: 10.1186/cc6117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buettner M., Schummer W., Huettemann E., Schenke S., van Hout N., Sakka S.G. Influence of systolic-pressure-variation-guided intraoperative fluid management on organ function and oxygen transport. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:194–199. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harten J., Crozier J.E., McCreath B., et al. Effect of intraoperative fluid optimisation on renal function in patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery: a randomised controlled pilot study (ISRCTN 11799696) Int J Surg. 2008;6:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senagore A.J., Emery T., Luchtefeld M., Kim D., Dujovny N., Hoedema R. Fluid management for laparoscopic colectomy: a prospective, randomized assessment of goal-directed administration of balanced salt solution or hetastarch coupled with an enhanced recovery program. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1935–1940. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b4c35e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benes J., Chytra I., Altmann P., et al. Intraoperative fluid optimization using stroke volume variation in high risk surgical patients: results of prospective randomized study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R118. doi: 10.1186/cc9070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forget P., Lois F., de Kock M. Goal-directed fluid management based on the pulse oximeter-derived pleth variability index reduces lactate levels and improves fluid management. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:910–914. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181eb624f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayer J., Boldt J., Mengistu A.M., Röhm K.D., Suttner S. Goal-directed intraoperative therapy based on autocalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis reduces hospital stay in high-risk surgical patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R18. doi: 10.1186/cc8875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van der Linden P.J., Dierick A., Wilmin S., Bellens B., De Hert S.G. A randomized controlled trial comparing an intraoperative goal-directed strategy with routine clinical practice in patients undergoing peripheral arterial surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:788–793. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833cb2dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Challand C., Struthers R., Sneyd J.R., et al. Randomized controlled trial of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy in aerobically fit and unfit patients having major colorectal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:53–62. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pillai P., McEleavy I., Gaughan M., et al. A double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial to assess the effect of Doppler optimized intraoperative fluid management on outcome following radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2011;186:2201–2206. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brandstrup B., Svendsen P.E., Rasmussen M., et al. Which goal for fluid therapy during colorectal surgery is followed by the best outcome: near-maximal stroke volume or zero fluid balance? Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:191–199. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang J., Qiao H., He Z., Wang Y., Che X., Liang W. Intraoperative fluid management in open gastrointestinal surgery: goal-directed versus restrictive. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67:1149–1155. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(10)06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bisgaard J., Gilsaa T., Rønholm E., Toft P. Optimising stroke volume and oxygen delivery in abdominal aortic surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:178–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bundgaard-Nielsen M., Jans Ø., Müller R.G., et al. Does goal-directed fluid therapy affect postoperative orthostatic intolerance?: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:813–823. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829ce4ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.El Sharkawy O.A., Refaat E.K., Ibraheem A.E., et al. Transoesophageal Doppler compared to central venous pressure for perioperative hemodynamic monitoring and fluid guidance in liver resection. Saudi J Anaesth. 2013;7:378–386. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.121044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McKenny M., Conroy P., Wong A., et al. A randomised prospective trial of intra-operative oesophageal Doppler-guided fluid administration in major gynaecological surgery. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:1224–1231. doi: 10.1111/anae.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramsingh D.S., Sanghvi C., Gamboa J., Cannesson M., Applegate R.L., 2nd Outcome impact of goal directed fluid therapy during high risk abdominal surgery in low to moderate risk patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;27:249–257. doi: 10.1007/s10877-012-9422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salzwedel C., Puig J., Carstens A., et al. Perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy based on radial arterial pulse pressure variation and continuous cardiac index trending reduces postoperative complications after major abdominal surgery: a multi-center, prospective, randomized study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R191. doi: 10.1186/cc12885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scheeren T.W., Wiesenack C., Gerlach H., Marx G. Goal-directed intraoperative fluid therapy guided by stroke volume and its variation in high-risk surgical patients: a prospective randomized multicentre study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;27:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s10877-013-9461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Srinivasa S., Taylor M.H., Singh P.P., Yu T.C., Soop M., Hill A.G. Randomized clinical trial of goal-directed fluid therapy within an enhanced recovery protocol for elective colectomy. Br J Surg. 2013;100:66–74. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zakhaleva J., Tam J., Denoya P.I., Bishawi M., Bergamaschi R. The impact of intravenous fluid administration on complication rates in bowel surgery within an enhanced recovery protocol: a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:892–899. doi: 10.1111/codi.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng H., Guo H., Ye J.R., Chen L., Ma H.P. Goal-directed fluid therapy in gastrointestinal surgery in older coronary heart disease patients: randomized trial. World J Surg. 2013;37:2820–2829. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pearse R.M., Harrison D.A., MacDonald N., et al. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. JAMA. 2014;311:2181–2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peng K., Li J., Cheng H., Ji F.H. Goal-directed fluid therapy based on stroke volume variations improves fluid management and gastrointestinal perfusion in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23:413–420. doi: 10.1159/000363573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pestaña D., Espinosa E., Eden A., et al. Perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic optimization using noninvasive cardiac output monitoring in major abdominal surgery: a prospective, randomized, multicenter, pragmatic trial: POEMAS Study (PeriOperative goal-directed thErapy in Major Abdominal Surgery) Anesth Analg. 2014;119:579–587. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Phan T.D., D'Souza B., Rattray M.J., Johnston M.J., Cowie B.S. A randomised controlled trial of fluid restriction compared to oesophageal Doppler-guided goal-directed fluid therapy in elective major colorectal surgery within an Enhanced Recovery after Surgery program. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2014;42:752–760. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1404200611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shillcutt S.K., Montzingo C.R., Agrawal A., et al. Echocardiography-based hemodynamic management of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction: a feasibility and safety study. Echocardiography. 2014;31:1189–1198. doi: 10.1111/echo.12574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Benes J., Haidingerova L., Pouska J., et al. Fluid management guided by a continuous non-invasive arterial pressure device is associated with decreased postoperative morbidity after total knee and hip replacement. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:148. doi: 10.1186/s12871-015-0131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Colantonio L., Claroni C., Fabrizi L., et al. A randomized trial of goal directed vs. standard fluid therapy in cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:722–729. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2743-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Correa-Gallego C., Tan K.S., Arslan-Carlon V., et al. Goal-directed fluid therapy using stroke volume variation for resuscitation after low central venous pressure-assisted liver resection: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Funk D.J., HayGlass K.T., Koulack J., Harding G., Boyd A., Brinkman R. A randomized controlled trial on the effects of goal-directed therapy on the inflammatory response open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Crit Care. 2015;19:247. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0974-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jammer I., Tuovila M., Ulvik A. Stroke volume variation to guide fluid therapy: is it suitable for high-risk surgical patients? A terminated randomized controlled trial. Perioper Med (Lond) 2015;4:6. doi: 10.1186/s13741-015-0016-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kumar L., Kanneganti Y.S., Rajan S. Outcomes of implementation of enhanced goal directed therapy in high-risk patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Indian J Anaesth. 2015;59:228–233. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.155000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lai C.W., Starkie T., Creanor S., et al. Randomized controlled trial of stroke volume optimization during elective major abdominal surgery in patients stratified by aerobic fitness. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:578–589. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Broch O., Carstens A., Gruenewald M., et al. Non-invasive hemodynamic optimization in major abdominal surgery: a feasibility study. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016;82:1158–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hand W.R., Stoll W.D., McEvoy M.D., et al. Intraoperative goal-directed hemodynamic management in free tissue transfer for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38:E1974–E1980. doi: 10.1002/hed.24362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kumar L., Rajan S., Baalachandran R. Outcomes associated with stroke volume variation versus central venous pressure guided fluid replacements during major abdominal surgery. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016;32:182–186. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schmid S., Kapfer B., Heim M., et al. Algorithm-guided goal-directed haemodynamic therapy does not improve renal function after major abdominal surgery compared to good standard clinical care: a prospective randomised trial. Crit Care. 2016;20:50. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Elgendy M.A., Esmat I.M., Kassim D.Y. Outcome of intraoperative goal-directed therapy using Vigileo/FloTrac in high-risk patients scheduled for major abdominal surgeries: a prospective randomized trial. Egypt J Anaesth. 2017;33:263–269. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gómez-Izquierdo J.C., Trainito A., Mirzakandov D., et al. Goal-directed fluid therapy does not reduce primary postoperative ileus after elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2017;127:36–49. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liang M., Li Y., Lin L., et al. Effect of goal-directed fluid therapy on the prognosis of elderly patients with hypertension receiving plasmakinetic energy transurethral resection of prostate. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10:1290–1296. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Luo J., Xue J., Liu J., Liu B., Liu L., Chen G. Goal-directed fluid restriction during brain surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7:16. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0239-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reisinger K.W., Willigers H.M., Jansen J., et al. Doppler-guided goal-directed fluid therapy does not affect intestinal cell damage but increases global gastrointestinal perfusion in colorectal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:1081–1091. doi: 10.1111/codi.13923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stens J., Hering J.P., van der Hoeven C.W.P., et al. The added value of cardiac index and pulse pressure variation monitoring to mean arterial pressure-guided volume therapy in moderate-risk abdominal surgery (COGUIDE): a pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:1078–1087. doi: 10.1111/anae.13834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weinberg L., Ianno D., Churilov L., et al. Restrictive intraoperative fluid optimisation algorithm improves outcomes in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective multicentre randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu J., Ma Y., Wang T., Xu G., Fan L., Zhang Y. Goal-directed fluid management based on the auto-calibrated arterial pressure-derived stroke volume variation in patients undergoing supratentorial neoplasms surgery. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10:3106–3114. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Calvo-Vecino J.M., Ripollés-Melchor J., Mythen M.G., et al. Effect of goal-directed haemodynamic therapy on postoperative complications in low-moderate risk surgical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (FEDORA trial) Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:734–744. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kaufmann K.B., Baar W., Rexer J., et al. Evaluation of hemodynamic goal-directed therapy to reduce the incidence of bone cement implantation syndrome in patients undergoing cemented hip arthroplasty — a randomized parallel-arm trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18:63. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0526-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim H.J., Kim E.J., Lee H.J., et al. Effect of goal-directed haemodynamic therapy in free flap reconstruction for head and neck cancer. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62:903–914. doi: 10.1111/aas.13100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yin K., Ding J., Wu Y., Peng M. Goal-directed fluid therapy based on noninvasive cardiac output monitor reduces postoperative complications in elderly patients after gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34:1320–1325. doi: 10.12669/pjms.346.15854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang N., Liang M., Zhang D.D., et al. Effect of goal-directed fluid therapy on early cognitive function in elderly patients with spinal stenosis: a case-control study. Int J Surg. 2018;54:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cesur S., Çardaközü T., Kuş A., Türkyılmaz N., Yavuz Ö. Comparison of conventional fluid management with PVI-based goal-directed fluid management in elective colorectal surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2019;33:249–257. doi: 10.1007/s10877-018-0163-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Davies S.J., Yates D.R., Wilson R.J.T., et al. A randomised trial of non-invasive cardiac output monitoring to guide haemodynamic optimisation in high risk patients undergoing urgent surgical repair of proximal femoral fractures (ClearNOF trial NCT02382185) Perioper Med (Lond) 2019;8:8. doi: 10.1186/s13741-019-0119-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Godai K., Matsunaga A., Kanmura Y. The effects of hemodynamic management using the trend of the perfusion index and pulse pressure variation on tissue perfusion: a randomized pilot study. JA Clin Rep. 2019;5:72. doi: 10.1186/s40981-019-0291-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hasanin A., Zanata T., Osman S., et al. Pulse pressure variation-guided fluid therapy during supratentorial brain tumour excision: a randomized controlled trial. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:2474–2479. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu F., Lv J., Zhang W., Liu Z., Dong L., Wang Y. Randomized controlled trial of regional tissue oxygenation following goal-directed fluid therapy during laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:4390–4399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sujatha P.P., Nileshwar A., Krishna H.M., Prasad S.S., Prabhu M., Kamath S.U. Goal-directed vs traditional approach to intraoperative fluid therapy during open major bowel surgery: is there a difference? Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2019;2019:3408940. doi: 10.1155/2019/3408940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Szturz P., Folwarczny P., Kula R., Neiser J., Ševčík P., Benes J. Multi-parametric functional hemodynamic optimization improves postsurgical outcome after intermediate risk open gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019;85:244–254. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.18.12467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Weinberg L., Ianno D., Churilov L., et al. Goal directed fluid therapy for major liver resection: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2019;45:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arslan-Carlon V., Tan K.S., Dalbagni G., et al. Goal-directed versus standard fluid therapy to decrease ileus after open radical cystectomy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:293–303. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.De Cassai A., Bond O., Marini S., et al. [Pulse pressure variation guided fluid therapy during kidney transplantation: a randomized controlled trial] Braz J Anesthesiol. 2020;70:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2020.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]