Abstract

Purpose of Review

Exposure to trauma accelerates during the adolescence, and due to increased behavioral and psychiatric vulnerability during this developmental period, traumatic events during this time are more likely to cause a lasting impact. In this article, we use three case studies of hospitalized adolescents to illustrate the application of trauma-informed principles of care with this unique population.

Recent Findings

Adolescents today are caught in the crosshairs of two syndemics—racism and other structural inequities and the COVID-19 pandemic. Increased hospitalizations and mental health diagnoses during the past two years signal toxic levels of stress affecting this group. Trauma-informed care promotes health, healing, and equity.

Summary

This concept of the “trauma-informed approach” is still novel; through examples and practice, providers can learn to universally apply the trauma-informed care framework to every patient encounter to address the harmful effects of trauma and promote recovery and resilience.

Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences, Adolescent, Hospitalized, Patient-centered care, Feeding and eating disorders, Suicide

Introduction

Haley is a 19-year-old admitted to the pediatric floor after telling their roommate, “I am at the end of my line and can’t keep going.” Ryan is a 16-year-old hospitalized with anorexia nervosa. Emmanuel is a 13-year-old struggling with a new diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. Adolescents in similar situations are currently well-represented in pediatric hospitals, with children’s mental health being a national emergency [1–3]. Any history of trauma may influence how these patients experience a hospitalization and can be compounded by trauma of the hospitalization itself.

This paper will review how trauma influences adolescents during hospitalization and how inpatient providers can utilize an understanding of the prevalence and impact of trauma to provide therapeutic care. After reviewing the impacts of trauma in this population and introducing the principles of trauma-informed care (TIC), we will use cases to discuss applying skills to the care of hospitalized adolescents in varying stages of development. Importantly, we aim to equip readers with strategies to Realize how trauma can affect an adolescent patient and their family, Recognize the signs of trauma in this population, Respond to trauma while an adolescent is hospitalized, and Resist further traumatization within an inpatient setting (the four “R’s” of TIC) [4].

Epidemiology of Trauma

Trauma is “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances an individual experiences as physically or emotionally harmful that can have lasting adverse effects on the person’s functioning and mental, physical, emotional, or spiritual well-being” [5•]. This definition encompasses individual traumas such as car accidents or the death of loved one; interpersonal traumas such as interpersonal violence, discrimination, or abuse; collective traumas such as natural disasters or pandemics; and structural traumas such as racism and sexism. Trauma can occur at any life stage. Roughly 90% of Americans have experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, and 28.9% of youth have experienced at least one adverse childhood event (ACE) [6, 7]. Transgender and gender diverse adolescence have the highest rates of mistreatment, harassment, and violence in their home life, school, occupations, and interpersonal relationships; nearly half of these individuals have been sexually assaulted and 40% have attempted suicide in their lifetime [8]. In socio-economically disadvantaged communities, rates of trauma exposure have also been shown to be disproportionally higher [9, 10••]. In the USA, racial-based traumatic stress (the mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical injury that occurs as the result of living within a racist system or experiencing racism) [11] leaves Black, Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) most vulnerable. Examples of individualized, interpersonal, and systemic racism afflicting trauma on a range of minority groups have persisted and continue to persist throughout this nation’s history.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a collectively experienced potentially traumatic stress in adolescents and children akin to the trauma of a natural disaster [12]. Stressors occurring during this time include prolonged home confinement, school interruptions, worry for loved ones, unexpected illnesses and death, mental healthcare disruptions, and economic instability [13, 14]. These challenges have had the potential to exacerbate any number of individual traumas, including identity crises and family conflicts [15]. Notably, adolescents have experienced the results of governments and communities failing to address the impact of structural violence and racism. Though the full extent of the impact of racism and other structural inequities, as well as the effects of COVID-19 pandemic, on developing youth has yet to be quantified, increased hospitalizations and diagnoses suggest that anxiety, fear, anger, loneliness, and grief associated with these events has led to toxic stress for many adolescents [16••, 17, 18].

Exposure to many types of trauma accelerates and peaks in the teenage years [19]. Traumatic experiences cluster such that adolescents exposed to one event are at an increased risk for additional ACEs [20]. Trauma during the impressionable periods of childhood and adolescence is strongly associated with worse mental and physical health outcomes as well as high-risk adolescent behavior and functional impairment [20–22]. Trauma can directly interfere with the core objectives of adolescence: (1) biological and sexual maturation, (2) development of a personal identity, (3) establishment of intimate sexual relationships, and (4) establishment of independence and autonomy in the context of the sociocultural environment [23].

Trauma-Informed Care

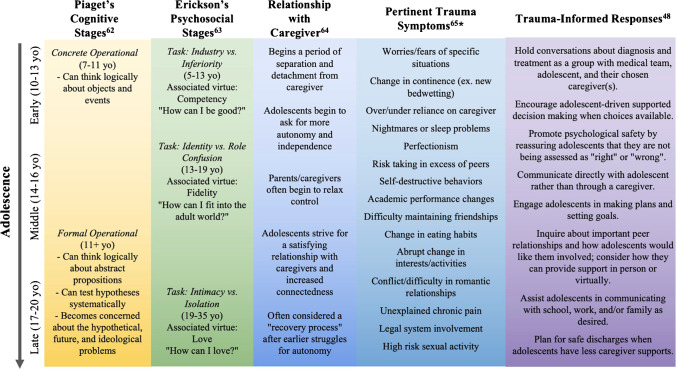

Recurrent exposure to trauma is correlated with increased behavioral and psychological symptoms in adolescents (see Fig. 1) [24]. Medical interventions themselves have the potential to be traumatic for patients and families [25]. TIC is a strength-based approach “grounded in an understanding of and responsiveness to the impact of trauma, that emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety for both providers and survivors, and that creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment” [26]. The core goals of TIC are to (1) reduce re-traumatization, (2) highlight survivor strengths and resilience, (3) promote healing and recovery, and (4) support the development of healthy short- and long-term coping mechanisms [27]. In the context of all patients, but especially pediatric patients, this framework must be applied to both the patient and their family.

Fig. 1.

Incorporating principles of TIC through hospitalization

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has developed a framework outlining six key-principles of TIC: (1) safety; (2) trust and transparency; (3) peer support; (4) collaboration and mutuality; (5) empowerment, voice, and choice; and (6) cultural, gender, and historical issues [4]. Examples of using TIC in caring for adolescents can map directly to these principles. For example, to ensure safety, medical staff can ask a patient’s preference about where procedures should be performed, thus protecting the patient’s bed as a place of healing. To ensure trust and transparency, clinicians should provide early and honest discussion with adolescents about their differential diagnoses and ultimate diagnosis [28]. We acknowledge that many providers may feel underprepared to address patients’ trauma histories and the possibilities of de novo and re-traumatization [29]. Skills of TIC can be learned, and increased dexterity with principles of TIC takes time and repetition [30]. In the following three cases, we will continue to discuss how to incorporate principles of TIC in the care of all hospitalized adolescents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adolescent development, trauma symptoms, and trauma-informed responses

| Admission | Daily | Discharge | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Strengths-based Relationship-based |

Inquire about patients’ strengths, consider a self-assessment of strengths, reflect noted strengths back to the patient, and leverage strengths in treatment | ||

|

Contact primary care providers and mental health clinicians on admission (with patient permission) Inquire about how to best support patient preferences |

Document patients’ interests, passions, and preferences Include these notes in hand-offs to support continuity of therapeutic alliance between teams |

Contact primary care providers and mental health clinicians prior to discharge to ensure continuity of care Highlight noted patient preferences and strengths |

|

| Safety |

Support trusted caregivers and/or peers to be at the bedside Identify with adolescents if certain family members/caregivers/friends make them feel unsafe and determine hospital mechanisms to limit that visitation Discuss and reinforce how to ask for nursing, provider, and team support (social work, child life, chaplaincy) |

Discuss home life and identify a safe discharge plan Provide information regarding resources in the community if home life becomes unsafe |

|

| Trustworthiness and transparency |

Provide care as originally specified; promptly communicate deviations from original plans Communicate work-up, results, and diagnoses directly with adolescents (i.e., not through family members) |

Ensure defined discharge criteria and adhere to these criteria throughout hospitalization | |

| Peer support |

Identify relationships in the teen’s life that they identify to be meaningful Respect and normalize that relationships with family may be challenging or not existent Discuss how to maintain communication with schools, universities, or employers during hospitalization (consider consulting social work and/or child life to support these discussions) |

Discuss with the adolescent how they may lead discussions with peers/family regarding details of the hospitalization Leverage flexible visitation (i.e. friends may have to visit after school/work) and technology to maintain these important relationships Identify diagnosis-related peer support groups |

Plan with the adolescent how they will re-engage with their meaningful community activities Work with the adolescent to define scripts to address questions of their absence during hospitalization |

| Collaboration and mutuality | Elicit adolescent’s goals for hospitalization and collaborate to find shared goals |

Focus on working with the patient (i.e., we are not doing this TO you but WITH you) Continually elicit both short-term (daily) goals as well as long term (for hospitalization and beyond) |

Convey patient-identified long-term care goals to the primary care provider to ensure continuity of goals |

| Empowerment, voice, and choice |

Close encounters by eliciting questions directly from the adolescent to ensure their understanding Explain procedures prior to initiation and convey how the adolescent can communicate stopping procedures if the adolescent feels unsafe or a loss of control Inquire regarding learning preferences, and provide videos, images, and/or text to ensure the teen understands diagnoses and treatment Support healthy boundaries regarding discussing personal medical information |

Discuss that the individual controls the disclosure of personal medical information to peers Ensure supported decision-making (with caregiver, if appropriate) around treatment decisions and discharge planning |

|

| Cultural, historical, and gender issues |

Initiate every encounter with a medically stable patient with a discussion of names and pronouns Discuss and document which names and pronouns are preferred in which settings Lead with inquiry of cultural or religious practices that can be supported throughout hospitalization (i.e., Kosher diets or Holy communion) |

Introduce new members of the team with names and pronouns Consider staff pins or name badges that include pronouns Use simple, clinical language during the physical exam Ask the patient which terms they use to talk about their body (i.e., vagina vs. genital opening) |

Attempt to support gender or cultural preferences when selecting referrals for outpatient providers (i.e., an adolescent girl may be more comfortable with a woman as a provider) |

| Trauma-informed techniques | Practice a trauma-informed physical exam. For further discussion of this exam, we recommend “A Novel, Trauma-Informed Physical Examination Curriculum for First-Year Medical Students” by Elisseou et al. [61••] (noting that this exam is described for adult patients, and principles must be adapted for a pediatric population) | ||

Case One: a Case of Intentional Ingestion

Haley is a 19-year-old college student (they/them pronouns) with a history of major depressive disorder who was admitted to the pediatric service after an intentional overdose of bupropion.

On the day of admission, Haley had told their roommate, “I am at the end of my line and can’t keep going anymore.” A few hours later, their roommate returned to the room to find Haley agitated, disoriented, and mumbling. Haley then had rapid eye movements and loss of tone, followed by whole body shaking. Haley’s roommate called 9-1-1.

EMS arrived, Haley was eventually admitted to the PICU, and they were transferred to the medical floor when stable. Based on past prescriptions and an empty pill bottle, they were believed to have ingested a potentially lethal dose of bupropion.

Social history was provided by Haley’s roommate, who listed several stressors in Haley’s life including a failed exam and less frequent communication with their partner. The roommate noted that Haley had been missing class, skipping meals, and sleeping for several hours during the day, all of which was out of the ordinary. Haley’s roommate also noted that Haley’s family relationships had been strained. The roommate stated that Haley is “a truly great friend” and usually “such a positive person to be around.”

With this background, Haley’s providers ask questions such as follows:

What are best practices for TIC of a patient after a suicide attempt?

How should an inpatient provider proceed with trauma-inquiry with this patient?

Over the last decade, rates of suicide among adolescents have risen alarmingly [31, 32], and during the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of ED visits for mental health conditions has markedly increased [1]. Periods of high COVID-19 stress in the community have been paralleled by higher rates of suicide ideation or attempt among adolescents [33•]. Prior to the pandemic, black youth were already experiencing a significant upward trend in suicide [34], and during this period of increased racism and structural inequities, race-based discrimination has been shown as a “painful and provocative event” for increased depression and suicide ideation [35••].

In a patient like Haley, TIC is relationship-based and starts with building rapport and a therapeutic relationship with the patient prior to addressing any trauma [36•]. Sitting at the bedside [37], sincerely asking the patient “how are you?,” and starting with discussions of a patients’ strengths and passions can help build and maintain a therapeutic alliance with patients.

Assuming principles of solution-focused brief therapy, TIC is a strength-based approach that focuses on “patients’ resources and preferred future rather than their histories and problems” [38]. After medical stabilization, the pediatric team should promote the patient’s self-assessment of their key strengths. To provide reflection time, the team could consider “homework assignments,” such as creating short lists of talents, successes, challenges overcome, or values. This work builds a sense of self-worth, can be done on the medical ward, and can carry forward to psychiatric treatment. This strength-based focus aligns with the principle of empowerment, voice, and choice discussed in more detail below.

Key TIC principles in Haley’s care include peer support and cultural, historical, and gender issues. To ensure peer support, care teams should acknowledge the prevalent stigma regarding mental health [39] and directly engage with patients about how they want to discuss their hospitalization with friends and family. The team should empower patients to lead discussions with these relevant individuals but support conversations as patients feel necessary to provide medical context. Providers must acknowledge beforehand that their outside opinions of who may be supportive, such as parents, may not align with patients’ experiences. In this setting, attempts can be made to support visiting possibilities (hindered in many current settings) and virtual engagement with those the patient deems crucial.

As to cultural, historical, and gender issues, providers should initiate a prompt discussion of names and pronouns. Transgender youth have extremely high levels of suicidal ideation and behavior [40]; use of chosen name and pronouns can be life-saving due to lower depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide behavior [41]. Notably, some individuals who identify as transgender or gender diverse may have not disclosed this aspect of identity with certain family members or peers. Transparent discussions about when to use the patient’s chosen name and pronouns are crucial to preserve safety and confidentiality, both in verbal communications and medical records.

When discussing self-harm behavior, providers can start by acknowledging the role that prior trauma exposure may have played in a patient’s symptomatology and that certain behaviors are an adaptation to cope. Asking directly about the antecedents to and emotional and relational impacts of the behavior promotes transparency and demonstrates openness and curiosity rather than judgment or blame. Exploring options for managing future situations in which the patient feels similarly triggered supports empowerment, voice and choice. In addition, providers should take a holistic approach that incorporates important aspects of an adolescent’s culture (such as religious, extracurricular, or school support) as well as their home environment (family and peer relationships).

History of difficult relationships with family and partners as well as a presentation with clear symptoms of trauma (i.e., suicide attempt) would require an assessment for certain types of traumas like intimate partner and domestic violence. Importantly, in the initial trauma inquiry, the provider should not require the patient to detail emotionally overwhelming events, as disclosure of granular details can be re-traumatizing for patients. As many patients are not aware of the connection between trauma and psychological or physical symptoms, the assessment instead can focus on how a history of trauma may affect the patient’s current patterns of behavior. The clinician should discuss how findings from the assessment can be used to support the patient’s care plan, such as arranging for community support, or can highlight the need for additional medical testing (i.e., STI or pregnancy). Frank discussions of trauma can be emotionally destabilizing, so clinicians should ensure that the patient is grounded, has a care plan in place for the immediate future (e.g., how they will manage the next few hours), and is aware of additional support resources. A team-based approach that includes a child abuse pediatrician and clinical social worker should be considered to ensure proper investigation and documentation is performed to protect the patient’s legal rights and to support access to community resources. Though beyond the scope of this article, the child protective team should be engaged if there is any suspicion of ongoing abuse or safety concern. After the initial trauma inquiry, repeated and unnecessary inquiries should be avoided, if possible.

Case Two: a Case of New-Onset Eating Disorder

Ryan is a 16-year-old teenage girl (she/her pronouns) with no significant past medical history who was referred to the emergency room by her pediatrician in the setting of weight loss.

Ryan is a long-standing gymnast who three months prior to admission abruptly quit gymnastics after a “difficult interaction” with her coach. She then began to diet and became fixated on her weight and appearance. She skips breakfast and lunch, has soup most days for dinner, and goes on numerous multi-hour walks per day. She has lost approximately 11 kg. In addition, she has begun wearing exclusively compressive sports bras.

Ryan does well in school and describes having friends in classes, but over the last year, she has been less interested in social activities. Her mother is unclear why Ryan quit gymnastics and has encouraged Ryan to participate in other high school clubs as an alternative. In independent conversations with Ryan’s mother, she says that she and Ryan used to be close, but that Ryan has become increasingly isolated from her mother and her stepfather.

Due to electrolyte abnormalities, hypothermia, BMI of 16.5, and prolonged inadequate intake, Ryan was admitted to a general pediatrics floor and adolescent medicine was consulted, and Ryan was initiated on standardized treatment.

The inpatient team asks:

How might a history of trauma have contributed to Ryan’s acute presentation?

How can TIC principles be incorporated into treatment?

Eating disorders (e.g., anorexia nervosa and bulimia) and subthreshold eating conditions are prevalent in adolescents [42]. Ryan is among many children with exacerbated eating disorder signs and symptoms during the pandemic [2]. While Ryan’s conversation with her coach may have triggered behavior change, this was likely one of many contributors including societal, social, and athletic pressures, as well as an increased wish for control [43]. In middle adolescence, distancing from parents may be a normal behavior, but the sudden distancing from parents, peers, and extracurriculars is concerning. In addition to warning signs and symptoms of disordered eating, clinicians must keep in mind common trauma-related symptoms (Fig. 1).

In working with adolescents who have eating disorders, assumptions of past trauma are often held explicitly or implicitly. Many adolescents have experiences of body shame and fatphobia either in the media [44], in peer groups, or in family networks. In Ryan, additional aspects of her past that may warrant attention during treatment include long-term engagement in a competitive sport that relies on maintenance of a specific body type, a recent conversation that may have had undertones of fatphobia or sexualization, and a family structure that includes a stepfather (reflecting possible divorce or single mother history). Though much of the work around trauma and body dysmorphia will likely be done in outpatient settings, there are some aspects of Ryan’s case that require upfront attention. An initial evaluation to rule out current abuse and to ensure safety would be crucial (see “Case One” for detailed description of considerations in an initial evaluation). To ensure the team is correctly addressing and supporting Ryan, evaluation for gender dysphoria should be completed.

In working with patients with eating disorders, two crucial TIC principles include trustworthiness and transparency and collaboration and mutuality. Necessary treatment (i.e., feeding) is often unwanted—and in minors, forced—making the provision of care through a trauma-informed lens even more crucial. In addition, many patients receiving eating disorder treatment have already experienced inpatient therapy, resulting in traumatic experiences and distrust in the system. First and foremost, providers should work to make sure that patients feel trustworthiness and transparency with the team. This can include care being provided as originally specified (such as meals at specific times) or care being escalated or deescalated as it has been indicated (such as the nasogastric tube being inserted after three missed meals, and not allowing a fourth attempt). It cannot go unrecognized that communities that have been historically marginalized by healthcare may have a great deal of mistrust, and teams should recognize the possibility of prior adverse experiences and secondhand trauma. In the other direction, providers can take steps to indicate to patients that they have trust in them, as well. Working with patients to make them feel more heard or involved in care and trusted as participants in their own care allows for an increased sense of control and authenticity, and autonomous motivation has been found to predict treatment success [45, 46].

As to the principle of collaboration and mutuality, collaboration with a patient and their family includes identifying an eating disorder as an adaptive reaction to a traumatic situation rather than a pathological set of behaviors [27]. Mutuality centers on building a sense of working with the patient, rather than on the patient. With this approach, treatment should include nutritional support and work with the patient to determine skills to respond to this maladaptation through healthy methods of emotional regulation. The team should inquire about the patient’s strengths and encourage those traits and behaviors; alternatively, the team should also accept patient feedback about what is not working, and carefully negotiate those aspects of care. Mutuality includes shared decision-making around goals of care (i.e., discharge to residential treatment versus home). As an added layer of complexity, providers should collaborate with families as well, as their buy-in supports patient outcomes.

Case Three: a Case of Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress

Emmanuel is a previously healthy 13-year-old boy who uses he/him pronouns who was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit with the diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis in the setting of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes.

Emmanuel presented to the community emergency room after three days of nausea, vomiting, and mild diffuse abdominal pain. Over the past month, Emmanuel has been fatigued to the point of wanting to skip his usual favorite activities of basketball and computer class. His mother has noticed that Emmanuel looks thinner despite a “teenage boy appetite” and “eating everything in sight.”

The emergency physician noted extensive laboratory abnormalities, and Emmanuel was transferred, via helicopter, to the tertiary children’s hospital’s pediatric intensive care unit to be fluid resuscitated and started on an insulin drip.

Throughout the first night of admission, Emmanuel’s mother was noted to be visibly tearful. She noted to the nursing staff, “Between Emmanuel and my dad getting sick, we have spent this whole year in the hospital.”

Diabetes education began on day two of admission. Emmanuel was noted to be fearful of needles, and he did not engage in teaching by staff, instead pulling his blankets over his head and not responding to staff when teaching began.

Questions:

How may the process of Emmanuel’s admission have been potentially traumatizing/re-traumatizing for him?

How can trauma-informed principles be incorporated into educating Emmanuel about his disease?

Within the hospital, adolescents can experience pediatric medical traumatic stress (PMTS), which consists of a child or adolescent’s psychologic and physiologic response to potentially traumatic medical events such as procedures, pain, serious illness or injury, and effects of treatment [47]. PMTS can manifest as avoidance of healthcare systems, nightmares, and frank post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); notably, a child or adolescent is predisposed to PMTS if they have a history of other trauma prior to hospitalization [48]. PMTS is also known to affect not only the pediatric patient, but also their families and communities [49].

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, pediatric hospitalizations for non-psychiatric indications have been associated with additional parental anxiety and depression [50]. These parental symptoms are associated with challenges in adolescent emotional and behavioral functioning [51, 52], in addition to the direct effect of hospitalization during a pandemic on the mental health of an adolescent, which has not yet been fully elucidated. Like the patients, many caregivers will have been exposed to trauma and chronic stress inside the healthcare system, including racism, language barriers, illness, or injury, emphasizing the importance of a trauma-informed approach to the entire family unit.

Educating families like Emmanuel’s about new diagnoses in the setting of potentially traumatizing hospitalizations requires specific considerations. An acutely traumatic event can hinder the ability to process new information, as a perceived threat may cause emotional dysregulation, resulting in a state of either hyperarousal (“fight or flight”) or hypo-arousal (“freeze”) [53]. Emmanuel’s behavior of not engaging in teaching is likely indicative of hypo-arousal and assisting him in moving back into his window of tolerance will help him to learn about his new diagnosis. The window of tolerance describes a balanced state of arousal in which individuals can regulate their emotions and integrate new experiences [54]. Using tools of mindfulness to promote a sense of grounding and safety (explored further below) can help patients move into this window following potentially traumatizing events [55]. Patient strengths can also promote learning and healing. For example, Emmanuel’s team could note his interest in computers and use technology-based teaching. Emmanuel’s secure attachment with his mother is another strength that can promote resilience [56].

Using trauma-informed principles of safety and empowerment, voice, and choice can help Emmanuel and his mother navigate the hospitalization and learn about this new diagnosis. As to the principle of safety, the team should ensure that Emmanuel and his mother have a sense of feeling both physically and psychologically safe throughout his hospitalization. In the ICU, providers can promote a sense of safety by remaining present, sharing knowledge (as desired by patients and families), and addressing the key concerns families have [57]. While there will likely be overlap in adolescent and caregiver concerns, adolescents may carry their own concerns they wish to discuss. High-quality nursing care and presence of relatives at the bedside have been shown to improve adult patients’ sense of safety in the ICU [58], implying that adolescent patients could also benefit.

To ensure the principle of empowerment, voice, and choice, the team should provide the support to make choices in Emmanuel’s care when possible. Even in an emergency situation, providers can obtain consent from parents of minors and assent from these minors as is developmentally appropriate [47]. For a younger adolescent like Emmanuel, this could mean inclusion in treatment planning discussions and supported decision-making with his caregivers as he is ready. Patient education in the context of a potentially traumatic hospitalization should take place on the patient and family’s terms. In this case, the family could work with the team to set a time for teaching and choose how they would like to initially be taught (perhaps without needles at first, then adding them in for practice later). Following the patient and family’s lead can prepare them better for learning and help them to feel in control of the situation.

Conclusion

In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a marked increase in adolescent presentations and admissions to hospitals for mental health crises. This pandemic has also exacerbated long-existing disparities in healthcare based on race, socioeconomic status, and sexual and gender orientation; thus, adolescents in certain groups have been differentially affected. These teenagers often present with a history of trauma and can experience trauma in the setting of long-term boarding, medicalization, and treatment unaligned with personal will. Regardless of explicitly known ACEs or traumatic instances, approaching patients and families with a TIC lens can improve patient experiences and outcomes [59, 60], Though pediatric providers may feel unaccustomed to explicitly considering trauma or feel less responsibility to provide TIC in inpatient settings, these considerations are critical, especially given the current influx of these vulnerable populations. This paper provides an outline of TIC principles and examples of cases where applications of these tools are critical to patient health. Further research must be undertaken regarding how to teach both faculty- and trainees-specific trauma-informed methods, including trauma-informed communication and physical exam, how trauma-informed self-care can be applied to pediatric healthcare workers, and how to develop a quality standard to assess physician understanding and quality of trauma-informed skills.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Trauma-Informed Care Working Group at Harvard Medical School in their continued support for trauma-informed medical education.

Author Contribution

Allison Fialkowski conceptualized the review, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised this manuscript.

Katie Shaffer conceptualized the review, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised this manuscript.

Maya Ball-Burack conceptualized the review, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised this manuscript.

Traci L. Brooks reviewed and revised this manuscript.

Nhi-Ha T. Trinh conceptualized the review, reviewed, and revised this manuscript.

Jennifer E. Potter conceptualized the review, reviewed, and revised this manuscript.

Katherine R. Peeler conceptualized the review, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised this manuscript.

All the authors approved this manuscript as submitted and share responsibility for the content presented in the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Adolescent Medicine

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218533. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews A, Kramer RA, Peterson CM, Mitan L. Higher admission and rapid readmission rates among medically hospitalized youth with anorexia nervosa/atypical anorexia nervosa during COVID-19. Eat Behav. 2021;43:101573. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(24):888–894. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publ No. (SMA) 14–4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014:1–27.

- 5.•.Forkey H. Putting your trauma lens on. Pediatr Ann 2019:48(7):e269-e273. 10.3928/19382359-20190618-01. Comprehensive introduction of trauma-informed care in pediatrics. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatr. 2010;125(4):e778–e786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):537–547. doi: 10.1002/jts.21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi MA. Executive summary of the report of the US transgender survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. 2015;2016:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Gore S. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.••.Walsh D, McCartney G, Smith M, Armour G. Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019:73(12):1087–1093. 10.1136/jech-2019-212738. Supports the critical importance of understanding the socioeconomic context to address ACEs and mistreatment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Cleary SD, Snead R, Dietz-Chavez D, Rivera I, Edberg MC. Immigrant trauma and mental health outcomes among Latino youth. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;20(5):1053–1059. doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-0673-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM, Walling D, Bishop S, Karayan I, Pynoos R. 25-year follow-up of treated and not-treated adolescents after the Spitak earthquake: course and predictors of PTSD and depression. Psychol Med 51(6):976–988. Doi:10.1017/S0033291719003891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R, et al. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113264. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salerno JP, Williams ND, Gattamorta KA. LGBTQ populations: psychologically vulnerable communities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020;12(Suppl 1):S239–S242. doi: 10.1037/tra0000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cénat JM, Dalexis RD. The complex trauma spectrum during the COVID-19 pandemic: a threat for children and adolescents’ physical and mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113473. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.••.von Soest T, Kozák M, Rodríguez-Cano R, et al. Adolescents’ psychosocial well-being one year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nat Hum Behav 2022:1–12. 10.1038/s41562-021-01255-w. Large study of survey data examining psychosocial outcomes in adolescents before and during the pandemic. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Delvecchio E, Orgilés M, Morales A, et al. COVID-19: Psychological symptoms and coping strategies in preschoolers, schoolchildren, and adolescents. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2022;79:101390. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2022.101390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espinoza G, Hernandez HL. Adolescent loneliness, stress and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: the protective role of friends. Infant Child Dev 2022:e2305. Doi:10.1002/icd.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Breslau N. The epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10(3):198–210. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layne CM, Greeson JKP, Ostrowski SA, et al. Cumulative trauma exposure and high risk behavior in adolescence: findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network core data set. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2014;6(Suppl 1):S40–S49. doi: 10.1037/a0037799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sturman DA, Moghaddam B. The neurobiology of adolescence: changes in brain architecture, functional dynamics, and behavioral tendencies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(8):1704–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christie D, Viner R. Adolescent development. BMJ. 2005;330(7486):301–304. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7486.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darnell D, Flaster A, Hendricks K, Kerbrat A, Comtois KA. Adolescent clinical populations and associations between trauma and behavioral and emotional problems. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2019;11(3):266–273. doi: 10.1037/tra0000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price J, Kassam-Adams N, Alderfer MA, Christofferson J, Kazak AE. Systematic review: a reevaluation and update of the integrative (trajectory) model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41(1):86–97. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.K. Hopper E, L. Bassuk E, Olivet J. Shelter from the storm: trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. Open Health Serv Policy J 2010:3(2):80–100. Accessed October 23, 2021. https://benthamopen.com/ABSTRACT/TOHSPJ-3-80.

- 27.Substance abuse and mental health services administration. Understanding the impact of trauma. In: Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 57. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Serv Administr 2014:59–89. [PubMed]

- 28.Riccio A, Kapp SK, Jordan A, Dorelien AM, Gillespie-Lynch K. How is autistic identity in adolescence influenced by parental disclosure decisions and perceptions of autism? Autism. 2021;25(2):374–388. doi: 10.1177/1362361320958214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green BL, Kaltman S, Frank L, et al. Primary care providers’ experiences with trauma patients: a qualitative study. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2011;3(1):37–41. doi: 10.1037/a0020097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein E, Murray-García J, Sciolla AF, Topitzes J. Medical students’ perspectives on trauma-informed care training. Perm J 2018:22. Doi:10.7812/TPP/17-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Suicide rates in the United States continue to increase. NCHS Data Brief, no 309. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. [PubMed]

- 32.Mercado MC, Holland K, Leemis RW, Stone DM, Wang J. Trends in emergency department visits for nonfatal self-inflicted injuries among youth aged 10 to 24 years in the United States, 2001–2015. JAMA. 2017;318(19):1931–1933. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.•.Hill RM, Rufino K, Kurian S, Saxena J, Saxena K, Williams L. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatr 2021:147(3). 10.1542/peds.2020-029280. Correlates suicide ideation and attempts in relation to times of heightened COVID-19-related stressors. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Sheftall AH, Vakil F, Ruch DA, Boyd RC, Lindsey MA, Bridge JA. Black youth suicide: investigation of current trends and precipitating circumstances. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021:0(0). Doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2021.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.••.Brooks JR, Hong JH, Cheref S, Walker RL. Capability for suicide: discrimination as a painful and provocative event. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2020:50(6):1173-1180. 10.1111/sltb.12671. Describes perceived discrimination as increasing the capability for suicide in Black adults [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.•.Park J, Nwora C, Forkey H, Justin B, Chiu C. #15 a primer for understanding trauma-informed care in the pediatric setting. Cribsiders Pediatr Med Podcast 2020. https://thecurbsiders.com/cribsiders/15. Introduction to pediatric trauma-informed care in an accessible, podcast format with associated show notes.

- 37.Merel SE, McKinney CM, Ufkes P, Kwan AC, White AA. Sitting at patients’ bedsides may improve patients’ perceptions of physician communication skills. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):865–868. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang A, Franklin C, Currin-McCulloch J, Park S, Kim J. The effectiveness of strength-based, solution-focused brief therapy in medical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Behav Med. 2018;41(2):139–151. doi: 10.1007/s10865-017-9888-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moses T. Being treated differently: stigma experiences with family, peers, and school staff among adolescents with mental health disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):985–993. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grossman AH, Park JY, Russell ST. Transgender youth and suicidal behaviors: applying the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2016;20(4):329–349. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2016.1207581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell ST, Pollitt AM, Li G, Grossman AH. Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation and behavior among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(4):503–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714–723. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Froreich FV, Vartanian LR, Grisham JR, Touyz SW. Dimensions of control and their relation to disordered eating behaviours and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Eat Disord. 2016;4(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s40337-016-0104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uchôa FNM, Uchôa NM, Daniele TM da C, et al. Influence of the mass media and body dissatisfaction on the risk in adolescents of developing eating disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019:16(9):E1508. Doi:10.3390/ijerph16091508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Mansour S, Bruce KR, Steiger H, et al. Autonomous motivation: a predictor of treatment outcome in bulimia-spectrum eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;20(3):e116–e122. doi: 10.1002/erv.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holmes S, Malson H, Semlyen J. Regulating, “untrustworthy patients”: an analysis of “trust” and “distrust” in accounts of inpatient treatment for anorexia. Feminism & Psych. 2021;31(1):41–61. doi: 10.1177/0959353520967516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kassam-Adams N, Butler L. What do clinicians caring for children need to know about pediatric medical traumatic stress and the ethics of trauma-informed approaches? AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(8):793–801. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.8.pfor1-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.TIC Module A1 - what is trauma informed care? Accessed October 23, 2021. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/webapps/elearning/TIC/Mod01/story_html5.html

- 49.Kazak AE, Kassam-Adams N, Schneider S, Zelikovsky N, Alderfer MA, Rourke M. An integrative model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(4):343–355. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan R, Xu Q hui, Xia C cui, et al. Psychological status of parents of hospitalized children during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychiatry Res 2020:288:112953. Doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Bosco GL, Renk K, Dinger TM, Epstein MK, Phares V. The connections between adolescents’ perceptions of parents, parental psychological symptoms, and adolescent functioning. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2003;24(2):179–200. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00044-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sieh DS, Visser-Meily JMA, Meijer AM. The relationship between parental depressive symptoms, family type, and adolescent functioning. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson S, Taylor K. The neuroscience of adult learning: new directions for adult and continuing education, number 110. John Wiley & Sons; 2006.

- 54.Siegel DJ. The developing mind: how relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Publications; 2020.

- 55.Ogden P, Fisher J. Sensorimotor psychotherapy: interventions for trauma and attachment (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). WW Norton & Company; 2015 Apr 27.

- 56.Masten AS. Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mollon D. Feeling safe during an inpatient hospitalization: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(8):1727–1737. doi: 10.1111/jan.12348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wassenaar A, Schouten J, Schoonhoven L. Factors promoting intensive care patients’ perception of feeling safe: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(2):261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bartlett JD, Griffin JL, Spinazzola J, et al. The impact of a statewide trauma-informed care initiative in child welfare on the well-being of children and youth with complex trauma. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;84:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cary CE, McMillen JC. The data behind the dissemination: a systematic review of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for use with children and youth. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34(4):748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.••.Elisseou S, Puranam S, Nandi M. A novel, trauma-informed physical examination curriculum for first-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL 2019:15. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10799. Thorough curriculum to describe trauma-informed physical exam in adults that can be modified for pediatric population. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Piaget J. The theory of stages in cognitive development. In: Green D, Ford MP, Flamer GB, editors. Measurement and Piaget. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1971. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Erikson EH. Childhood and society. 2. New York: Norton; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keijsers L, Poulin F. Developmental changes in parent–child communication throughout adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(12):2301–2308. doi: 10.1037/a0032217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strand VC, Sarmiento TL, Pasquale LE. Assessment and screening tools for trauma in children and adolescents: a review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6(1):55–78. doi: 10.1177/1524838004272559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]