Abstract

Tubulin is an important cancer drug target. Compounds that bind at the colchicine site in tubulin have attracted significant interest as they are generally less affected by multidrug resistance than are other potential drugs. Modeling is useful in understanding the interactions between tubulin and colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs), but because the colchicine binding site contains two flexible loops whose conformations are highly ligand-dependent, modeling has its limitations. X-ray crystallography provides experimental pictures of tubulin–ligand interactions at this challenging colchicine site. Since 2004, when the first X-ray structure of tubulin in complex with N-deacetyl-N-(2-mercaptoacetyl)-colchicine (DAMA-colchicine) was published, many X-ray crystal structures have been reported for tubulin complexes involving the colchicine binding site. In this review, we summarize the crystal structures of tubulin in complexes with various CBSIs, aiming to facilitate the discovery of new generations of tubulin inhibitors.

Keywords: tubulin, colchicine-binding-site inhibitors, X-ray crystallography

Teaser:

Over the past decade, X-ray crystallography has greatly facilitated the discovery and development of new generations of tubulin inhibitors that utilize the colchicine binding site.

Introduction

The incidence of cancer has increased over the past decade, and it has been predicted that in 2021, there will be 1,898,160 new cancer cases and 608,570 cancer deaths in the United States.1 Microtubules, whose functions are closely related to cell proliferation, are one of the targets for anticancer agents.2 These structures are assembled from and disassembled into subunits of the protein tubulin. In eukaryotic cells, microtubules participate in multiple essential cellular activities, including intracellular transportation, formation of spindles during mitosis, and serving as a critical component of the cytoskeleton to maintain cell shape and to facilitate cellular motion.3 Their role in strengthening the structure of the cytoskeleton suggests that microtubules are intrinsically rigid, in line with their ability to withstand external force. However, microtubules are not static polymers and their functions rely on their dynamic properties.4

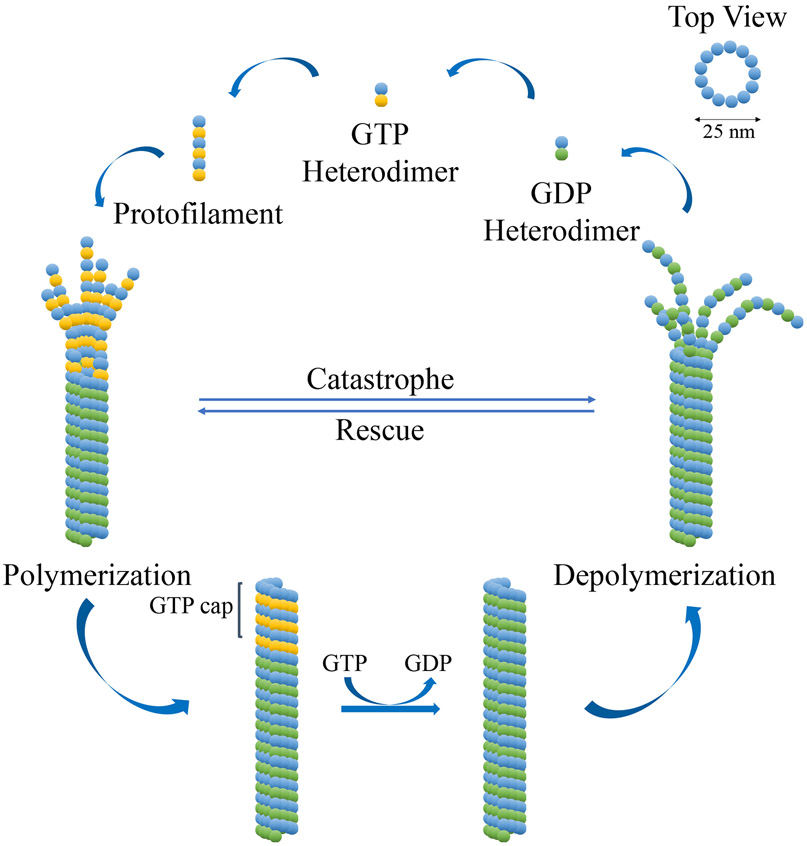

Microtubules are assembled and disassembled from tubulin subunits in a reversible manner. There are five different tubulin subunits (α, β, γ, δ and ε) but the subunit composition of microtubules varies with subcellular localization. Cytoplasmic microtubules are comprised of a heterodimer of α and β subunits, whereas microtubules in the centriole also contain γ, δ, and ε subunits.5,6 Both the α and the β subunits (~50 kDa each) are comprised of α-helices surrounding two core β-sheets. These subunits are assembled (polymerized) head-to-tail to form a linear hollow polarized microtubule whose rim has 13 subunits when viewed from the top. The microtubule disassembly process (hydrolysis) involves the reversible binding of GTP to the β-subunits of the heterodimers, the addition of GTP-bound heterodimers to the positive pole of the microtubule, the hydrolysis of the GTPs to GDPs, and the removal of the GDP-bound heterodimers. By contrast, GTP binding to the α-subunits is static and does not result in the hydrolysis of GTP. Microtubule dynamics result from a difference in rates of the binding and hydrolysis processes. If the binding process is faster than the hydrolysis, the microtubules will polymerize, but if the hydrolysis is more rapid than the binding, the microtubules will depolymerize (Figure 1).7-9

Figure 1: Microtubule dynamics.

The GDP heterodimer is comprised of one subunit each of GDP-bound β-tubulin (green sphere) and α-tubulin (blue sphere). The GTP heterodimer is comprised of one subunit each of GTP-bound β-tubulin (yellow sphere) and α-tubulin (blue sphere).

Microtubule targeting agents (MTA) are molecules that can prompt either the polymerization or the depolymerization of tubulin by interfering with microtubule dynamics, resulting in an antiproliferative effect against cancer cells.10 Recently, a combined computational and crystallographic fragment screening process identified and summarized multiple pockets and binding sites within tubulin,11 some of which bind microtubule-stabilizing agents, whereas others bind microtubule-destabilizing agents, including colchicine.12 Colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) are relatively small molecules that have strong anti-angiogenesis properties, and they are generally much less susceptible to ABC-transporter-mediated multidrug resistance (MDR) than are other MTAs.10,13

Technologies such as transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and electron crystallography made considerable contributions to early explorations of the interactions between tubulin and its ligands. However, due to the limited resolution of these technologies, the atomic details of these interactions remained elusive. X-ray crystallography offers much more detailed data that facilitated determination of the interactions within tubulin–ligand complexes. Together with technical advancements in the construction of stable α/β-tubulin heterodimer crystals, X-ray crystallography has made it possible to determine the structure of many complexes in which small molecules interact with the colchicine binding site within tubulin. In this review, we summarize X-ray crystallography results obtained in the past decade with the goal of facilitating the development of new colchicine binding site ligands that can interfere with microtubule dynamics.

Historical overview of ligand interactions at the colchicine binding site of tubulin from the perspective of X-ray crystallography

The structure of tubulin was determined in 1984 after the protein was isolated from sea urchin eggs and crystalized by adding vinblastine sulphate, MgCl2 and KCl. Clear pictures of tubulin crystals were obtained, and X-ray diffraction was applied to analyze the crystal patterns.14,15 The three-dimensional density maps of tubulin were determined at resolutions of 6.5 Å and 4 Å with the aid of electron crystallography in 1995.16,17 The same method was used to determine the structure of the α/β-tubulin heterodimer at 3.7 Å.18 This work led to the identification of three sequential domains in the tubulin monomer: the amino-terminal (N-terminal) domain, the intermediate domain, and the carboxy terminal (C-terminal) domain.18

It is often instructive to determine the structure of a protein with its ligand bound, in the hope that this structure will provide further insight into the conformation of the protein. In the case of tubulin, the first ligand to be studied in this way was a 19-kDa phosphoprotein called stathmin.19,20 This phosphoprotein can induce reversible microtubule depolymerization by binding to two units of α/β-tubulin heterodimer (thereby sequestering free tubulin) or by binding directly to microtubule ends to induce catastrophe. Phosphorylation of stathmin during mitosis can restore the microtubules.21-24 TEM of the tubulin–stathmin complex revealed its general shape,24 but the arrangement of tubulin subunits and stathmin within the complex remained elusive due to the limitations of these techniques. Even X-ray crystallographic determination of the structure of the complex was initially hindered by the heterogenic nature of tubulin and its relative instability in solution.

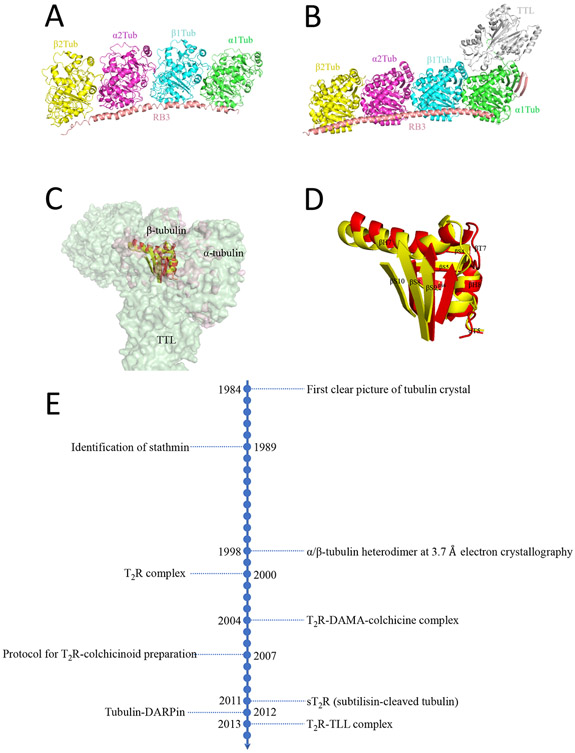

The first successful crystallization of tubulin with a ligand utilized a complex of GDP-tubulin with the stathmin-like domain (SLD) RB3 (T2R, PDB code 1FFX; Figure 2A).25 The structure of this complex was solved at 4 Å resolution by X-ray crystallography. This work not only revealed the molecular structure of the stathmin-sequestered tubulin complex T2R but, more importantly, laid the foundation for in-depth studies of microtubule dynamics.25 The established structure of the T2R complex was used to guide structural studies of the tubulin–colchicine interaction. Next a tubulin–N-deacetyl-N-(2-mercaptoacetyl)-colchicine:RB3-SLD complex (T2R-DAMA-colchicine) was constructed and solved (PDB code 1SA0). Crystallographic analysis was used to discover that the N-terminal domain of RB3-SLD functioned to cap one of the two tubulin heterodimers, so that their polymerization to a microtubule was halted. Moreover, this work proposed the mechanism through which colchicine (1, Figure 3) acts to prevent tubulin assembly. The assembly of tubulin requires a straight structure, but the binding of colchicine at the intermediate domain of tubulin prevents the protein from adopting a straight conformation. The structure of T2R bound to another CBSI, podophyllotoxin (2, Figure 3), was also determined (PDB code 1SA1).26 As a result, an elaborate optimized protocol was established for the preparation of T2R–colchicine or T2R–colchicinoid (colchicine site ligand) complexes.27

Figure 2: Structures of critical tubulin complexes.

(A) T2R strathmin–tubulin complex (PDB code 1FFX). (B) T2R–tubulin tyrosine ligase (TLL) complex (PDB code 4I55). (C) Curved T2R–TLL complex (light green, PDB code 4I55) superimposed on a straight α/β heterodimer (light pink, PDB code 1JFF). (D) Major conformational changes at the colchicine binding site of the superimposition. The moiety in the curved tubulin complex is in yellow, whereas that in the straight tubulin complex is in red. (E) Chronological view of how X-ray crystallography has facilitated the study of tubulin–colchicinoid interactions. DAMA-colchicine, N-deacetyl-N-(2-mercaptoacetyl)-colchicine; DARPin, designed ankyrin repeat protein.

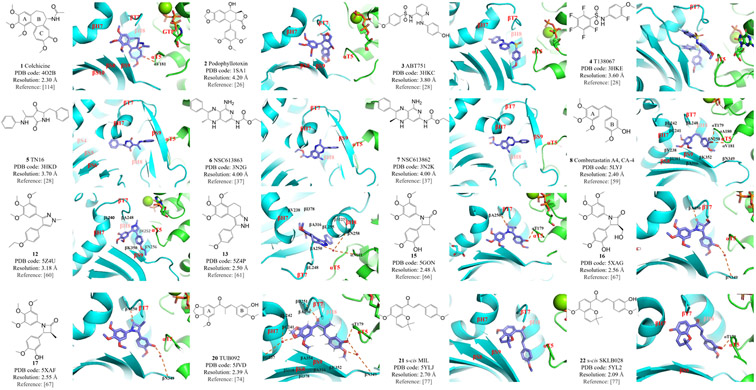

Figure 3: Structures and modes of interaction of colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) bound at the colchicine binding site of tubulin.

Compounds 1–7 were investigated during the historical development of tubulin–colchicinoid crystals; 8, 12, 13, 15, 16 and 17 are analogs of combretastatin; compounds 20–22 are analogs of chalcone.

These discoveries raised questions about how various ligands bind to the colchicine binding site, which is located primarily within the β-subunit and at the α/β-subunit interface within the heterodimer, in order to inhibit its adoption of the straight conformation. Also, how does the structure change if no ligand is bound? An ingenious study based on X-ray crystallography explored the molecular mechanism(s) behind these questions. Structures of T2R without bound ligand (PDB code 3HKB) and those of T2R complexes bound with colchicinoids ABT751 (3, PDB code 3HKC), T138067 (4, PDB code 3HKE) and TN16 (5, PDB code 3HKD) were determined and compared.28 The results indicated that in the absence of colchicine or other ligand, the βT7 loop changes to an inward ‘flipped in’ conformation that occupies the colchicine site, and the βN249 residue is overlapped with the colchicine A-ring. The βT7 loop joins together residues βH8 and βH7, which essentially shapes the straight and curved conformations. In addition, the βT7 loop is also related to the vertical conjunction between monomers. Compounds ABT751 (3) and T138067 (4) bind to the colchicine site in a manner similar to that of colchicine binding. However, TN16 (5) is deeply buried within the tubulin structure and only partially coincides with the colchicine binding pattern. These data suggest that what is commonly referred to as the ‘colchicine site’ is, in reality, the main site of what should be called the ‘colchicine binding domain’, which includes additional binding pockets deep inside the β-subunit.28

With regard to the role of GDP and GTP in the tubulin complex, the observation that tubulin can be induced to form a straight structure upon allosteric GTP binding suggested an allosteric model that favored tubulin polymerization. This mechanism predicted that the preferred curved conformation of GDP–tubulin, which is forced to be straight in microtubules, triggers microtubule catastrophe upon loss of the GTP-cap.29,30 However, later discoveries of the curved GTP–tubulin complex and curved GDP–free-tubulin challenged this allosteric theory. Instead, a lattice model was proposed in which GDP or GTP binding is the logical consequence of the structural switch rather than the cause of this switch.31-34 Further refined theories have attempted to balance or combine the allosteric and lattice models.35,36

An X-ray crystallographic study was conducted to determine the correlations between colchicine ligand binding and tubulin structural state.37 T2R–NSC613863 (6, PDB code 3N2G) and T2R–NSC613862 (7, PDB code 3N2K) complexes were assembled and their structures were compared with the previously reported T2R–colchicine (1) and T2R–TN16 (5) structures. The binding modes of the four complexes were identical overall and the curved structure was independent of the nucleotide type in the complex.37 Another study complemented these findings on the atomic structure of GTP–tubulin using a similar approach, but substituting sT2R (PDB code 3RYC) for T2R in nucleotide-containing complexes GTP–sT2R (PDB code 3RYF), GMPCPP–sT2R (PDB code 3RYH), and GDP–sT2R (PDB code 3RYI).38 sT2R is similar to T2R except that the C-termini of the monomers has been cleaved by subtilisin for higher resolution, whereas the GTP analog GMPCPP (guanylyl-(αβ)-methylene-diphosphonate) is more slowly hydrolyzed than GTP. This study found that rather than being a direct cause of tubulin straightening, GTP binding helps to lower the energy barrier of the straight/curved structural change.38

Microtubules are polarized structures that are in a dynamic state of polymerization versus catastrophe.4 To fully understand the correlation between microtubule dynamics, GDP/GTP binding, and the polar microtubule ends, Pecqueur et al.39 introduced a series of designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins), among which D1 was found to inhibit tubulin assembly in a dose-dependent manner. The tubulin–D1 complex (PDB code 4DRX) was analyzed and compared with the GDP–sT2R (PDB code 3RYI) complex mentioned above. The binding mode of D1 to tubulin is different from that of stathmin binding in the T2R complex, but interestingly, the structures of the two complexes overlap well, indicating that the curved conformations adopted by tubulin in both cases were intrinsic to their unpolymerized state. Finally, a very low concentration of a constructed D1 tandem molecule can specifically inhibit microtubule (+)end assembly, indicating the presence of a selective (+)end capping mechanism.39

A new milestone for the construction of tubulin crystals was achieved by Prota et al.40,41 in 2013 (Figure 2B). This work was intended to discover the molecular mechanism of action of the enzyme tubulin tyrosine ligase (TTL), which posttranslationally adds tyrosine residues to the C-terminus of de-tyrosinated α-tubulin.42-44 On the basis of a previously reported TTL crystal structure and data describing a stable tubulin–TTL complex obtained from small-angle X-ray scattering,45 X-ray crystallography was used to analyze the tubulin–TTL complex (T2R–TTL-apo, PDB code 4IIJ; T2R–TTL-ADP, PDB code 4IHJ), yielding high-resolution structures at ~2 Å. Surprisingly, TTL was found to be in complex with T2R, preserving the curved shape of the original T2R complex. TTL binding occurred at the interface between the α- and β-subunits within an α/β T2R heterodimer. Thereafter, these methods were used to analyze the structures of T2R–TTL (PDB code 4I55) in complex with two different agents that target the taxane binding site in tubulin (T2R–TTL-Zampa, PDB code 4I4T; and T2R–TTL-EpoA, PDB code 4I50). These structures overlap perfectly with those of both T2R–TTL and T2R. X-ray crystallography analysis confirmed the binding mode of these agents involving the taxane pocket.41

Since then, studies related to the design of CBSIs and other types of MTAs with the aid of the now well-established crystal platform have been widely reported. Figures 2C and 2D show the spatial differences in the helices and loops of the colchicine binding site between the straight and curved conformations. Figure 2E summarizes a chronological timeline for the development of tubulin crystal complexes. In the following sections, we will summarize the X-ray crystallographic data by categories that are based on the chemical structures or binding modes exhibited by different CBSIs.

Combretastatin analogs

Combretastatins are natural products extracted from the South African bushwillow tree Combretum caffrum that were found to reverse the differentiation of astrocytes.46 A series of combretastatin derivatives that share a common cis-stilbene scaffold were successively isolated, analyzed, and later chemically synthesized.47-50 Combretastatin A-4 (CA-4, 8, Figure 3) was subsequently found to be cytotoxic against a variety of cancer cell lines.51

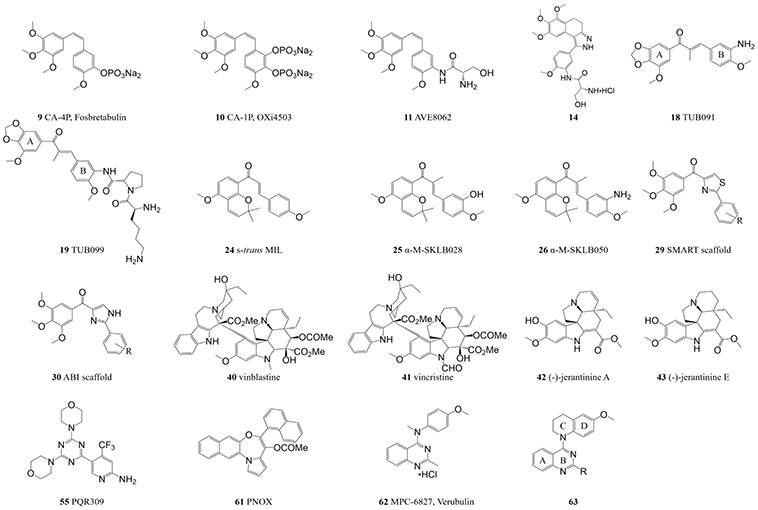

Structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies revealed several critical features of CA-4 that are related to its high antitumor potency, including a 3,4,5-trimethoxy substitution on the A-ring, a para-methoxy substitution on the B-ring, and the cis-configuration of the double bond (Figure 3).52 On the basis of these results, various CA-4 derivatives have been synthesized and evaluated for their antitumor potential. Several published review papers have thoroughly elucidated the rational design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of these CA-4 derivatives.52-55 Three CA-4 analogs, namely CA-4P (the phosphate of CA-4, 9, Figure 4), OXi4503 (the phosphate of CA-1, 10, Figure 4), and AVE8062 (11, Figure 4), were tested in antitumor clinical trials, either as monotherapies or in combination with paclitaxel.56

Figure 4:

Additional structures and scaffolds that do not have crystal structures with tubulin or are not colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs).

At the early stage, the SAR study showed that predominantly cis-trans isomerization alters the activity of CA-4 analogs.57,58 Although trans-CA-4 is thermodynamically more stable than cis-CA-4, it is essentially inactive as an antitumor drug.59 To explore the underlying molecular mechanism and to facilitate the further development of chemically stable CA-4 analogs, X-ray crystal analysis was performed on a T2R–TTL–cis-CA-4 complex (PDB code 5LYJ). The A-ring in cis-CA-4 is buried deeply in a hydrophobic pocket in the tubulin β-subunit (comprising βV238, βC241, βL242, βL248, βA250, βI318, βA354 and βI378). The B-ring is fixed at the interface within the heterodimer through hydrophobic interactions (involving αT179, αA180, αV181, βN258, βM259, βA316, βN349 and βK352). cis-CA-4 also forms two hydrogen bonds with αT179 and αV181.

Compound 12 (Figure 3) was designed from a series of CA-4 analogs that have a rigid five-membered ring that replaces the alkenyl double bond to maintain the overall cis-like structure.60 Data from in vitro and in vivo studies suggested that compound 12 is a promising tubulin inhibitor. X-ray crystal analysis confirmed that compound 12 binds to the colchicine site (PDB code 5Z4U), where hydrophobic interactions between compound 12 and residues in the tubulin β-subunit binding pocket are the major interactions. When compared with colchicine and CA-4, compound 12 shares an identical binding mode, including blockage of the straight/curved conformational change.60 Similarly, a novel scaffold of 1-phenyl-dihydrobenzoindazole was proposed to circumvent the issue of olefinic isomerization.61 The crystal structure of compound 13 (Figure 3) reveals an excellent lead compound that targets the colchicine site (PDB code 5Z4P), driven by hydrophobic interactions with tubulin residues βV238, βL242, βL248, βA250, βL255, βM259, βA316, βI318 and βI378. Two hydrogen bonds are formed with αN101 and βN258. Compound 13 was further optimized to yield compound 14 (Figure 4), which exhibits improved antiproliferative potency over a wider panel of cancer cell lines and enhanced water solubility relative to compound 13.61

The substitution of a β-lactam ring for the double-bond bridge of these CA-4 analogs also maintains a cis-like spatial orientation of rings A and B, and therefore provides an alternative scaffold for modified CA-4 analogs.62 A large number of CA-4 analogs containing a β-lactam ring were designed and synthesized, and they were found to induce significant vascular disruption through a molecular mechanism that remained elusive.63-65 To clarify the SAR of these analogs, specifically in terms of the stereochemistry of the β-lactam ring, compounds 15, 16 and 17 were synthesized and their crystal structures in complex with tubulin were evaluated (PDB codes 5GON, 5XAG and 5XAF, respectively; Figure 3). The A-ring of all three compounds binds deeply within the hydrophobic pocket of the β-tubulin, and this interaction is thought to be the main driving force of the binding. Compound 15 forms two hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues αT179 and βA250, whereas compounds 16 and 17 form two hydrogen bonds with βA250 and βN349. Notably, similar conformational changes to the tubulin βH7 and αT5 loops, which are typical features of colchicine and CA-4 binding, also indicate that these compounds bind to the colchicine site.66,67

Chalcone analogs

The antimitotic potential of chalcone compounds was first reported in 1990.68 Subsequently, the well-studied SAR of CA-4 analogs was used to design many additional chalcone analogs, with the aim of improving their metabolic stability.69-72 Although the T2R complex was used in early-stage docking studies of chalcone analogs with tubulin,73 the T2R–TTL complex was subsequently used to develop these analogs to a higher level and thus the crystal structures of a new series of chalcone analogs were investigated. Both the prototype compound TUB091 (18, Figure 4) and its prodrug TUB099 (19, Figure 4) possess prominent antimitotic activities. A modified compound TUB092 (compound 20, Figure 3) was soaked in co-crystal with the T2R–TTL complex (PDB code 5JVD) and superimposed with the reported crystal structure for apo-T2R–TTL (PDB code 4I55). As expected, the chalcone A-ring is buried in the hydrophobic pocket of the tubulin β subunit, with extensive interactions with tubulin residues βC241, βL242, βL248, βA250, βL255, βM259, βA316, βI318, βK352, βA354 and βI378. It also forms water-bridged hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues βG237 and βC241. The carbonyl moiety of the chalcone scaffold forms another hydrogen bond with tubulin βD251. In addition, the chalcone B-ring also forms hydrogen bonds with αT179 and βN349. Overall, tubulin residues βS8, βS9, βH7, βH8, βT7 and αT5 resemble features of the colchicine binding mode.74

Millepachine (MIL, compound 21, Figure 3) is a natural chalcone product, isolated from the plant Millettia pachycarpa, that has antitumor activity against human hepatocarcinoma cells.75,76 Two of its derivatives, SKLB028 (22, Figure 3) and SKLB050 (23, Figure 5), were designed to provide improved activity (lower IC50 values) and, more importantly, to bind to tubulin irreversibly, thereby providing a novel way to prevent MDR. X-ray crystal analysis shows that MIL (PDB code 5YLJ) is deeply buried in the colchicine binding site but does not form any hydrogen bonds with tubulin.77 By contrast, both SKLB028 (PDB code 5YL2) and SKLB050 (PDB code 5YLS) form a hydrogen bond with tubulin residue αT179, which might explain their enhanced antitumor activity.77 Superimposition of these compounds with the T2R–TTL–colchicine complex (PDB code 5XIW) indicates that they overlap well with colchicine, including the emblematic shift of the βT7 loop.77 In addition, further comparison between the X-ray crystal structures of free MIL and MIL in the complex (24, Figure 4) shows that the s-trans conformation of the chalcone scaffold is sterically favored at the tubulin binding site over the s-cis conformation, which was later verified by various biological assays performed on derivatives α-M-SKLB028 (25, Figure 4) and α-M-SKLB050 (26, Figure 4).77

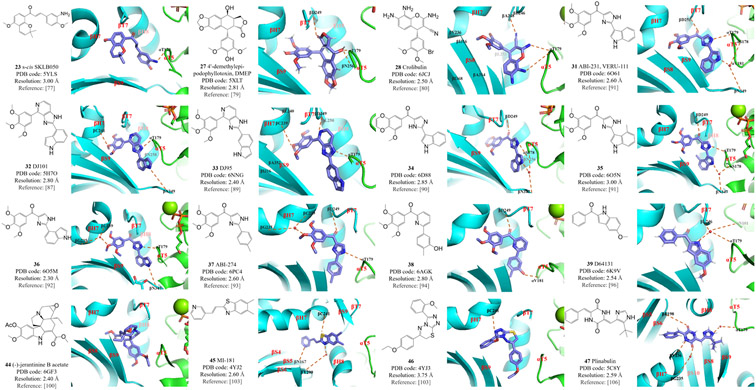

Figure 5: Structures and modes of interaction of colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) bound at the colchicine binding site of tubulin.

These compounds are analogs or derivatives of chalcone (compound 26), podophyllotoxin (compounds 27 and 28), ABI (compounds 31–38), indole (compounds 39 and 44), and CBSIs that fall into the ‘deep binding mode’ category (compounds 45–47). ABI, 2-aryl-4-benzoyl-imidazole.

Podophyllotoxin analogs

The cancer therapy drug podophyllotoxin (2, Figure 3) belongs to the lignan family and was first isolated in the late 19th century from the roots and rhizomes of several Podophyllum species. Its properties are similar to that of colchicine,78 and X-ray crystallographic analysis of its complex with T2R (PDB code 1SA1) confirmed that podophyllotoxin and colchicine share the same binding site in tubulin.26 However, the resolution of the initial structure was relatively low (4.2 Å) and the clinical use of podophyllotoxin was limited by its toxicity. In an attempt to design podophyllotoxin analogs with reduced toxicity, the podophyllotoxin analog 4’-demethylepipodophyllotoxin (DMEP, 27, Figure 5) was co-crystalized with the T2R–TTL complex, and its structure was solved at 2.8 Å resolution (PDB code 5XLT).79 DMEP–T2R–TTL forms three hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues αT179, βD249 and βN256. Comparison of DMEP with podophyllotoxin shows that these two compounds share the same binding mode.79

The podophyllotoxin analog crolibulin (compound 28, Figure 5) has both anti-angiogenesis and anticancer activity but strong toxicity has restricted its clinical use. To provide critical insights into the effects of future modifications of crolibulin-based compounds, a 2.5 Å resolution crystal structure of a crolibulin–tubulin complex was determined (PDB code 6JCJ).80 The crolibulin 3’-bromo,4’,5’-dimethoxybenzene ring binds deeply within the hydrophobic pocket of tubulin, extensively interacting with tubulin residues βY200, βV236, βL240, βL246, βA248, βL253, βA314, βI316, βA352 and βI368. The two amino groups and the cyano group in crolibulin form three hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues αT179 and βA248.80

ABI analogs

As described above, X-ray crystallography has shown that colchicine, CA-4 and podophyllotoxin all share a crucial 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl (TMP) moiety that interacts with the hydrophobic pocket in the tubulin β-subunit. A 4-substituted methoxylbenzoyl-aryl-thiazole (SMART) scaffold (29, Figure 4) exhibited nanomolar-scale IC50 potency against melanoma and prostate cancer cells. SAR studies confirmed the importance of the TMP moiety. Saturation of the thiazole moiety resulted in loss of potency,81 highlighting the importance of this unsaturated five-member ring. As the thiazole ring in SMART was susceptible to metabolic oxidation, it was hypothesized that a 2-aryl-4-benzoyl-imidazole (ABI) scaffold (30, Figure 4) that bioisosterically replaced the thiazole ring in SMART with an imidazole would achieve increased metabolic stability and improved aqueous solubility, while maintaining antiproliferative potency.82

Preliminary modification of ABI analogs led to the discovery of the most potent ABI analog against melanoma and prostate cancer cells in this series, ABI-231 (VERU-111, 31, Figure 5).83 VERU-111 is currently the subject of Phase 2 clinical trials for castration-resistant prostate cancer and COVID-19, and the initiation of a Phase 3 clinical trial in prostate cancer is ongoing.84 The success of VERU-111 and the application of advanced X-ray crystallography technology to CBSIs have facilitated the design and optimization of additional ABI analogs. As the ketone bridge in the ABI scaffold is metabolically labile,85 the ABI analog DJ101 (32, Figure 5) was designed to be more metabolically stable by incorporating the original ketone moiety into a stable ring system.86 X-ray crystallographic structural studies of T2R–TTL–DJ101 (PDB code 5H7O) confirmed that DJ101 interacts directly with the colchicine binding site. The trimethoxy and the imidazopyridine moieties of DJ101 interact with tubulin residues βC241, βL255, βL248 and βN258 via hydrophobic interactions.87 Three hydrogen bonds are formed with tubulin residues αT179, βN349 and βC241, whereas βM259 was a critical determinant of the major straight/curved conformational change.87 A further derivative, DJ95 (compound 33, Figure 5), shows improved antiproliferative potency and effectively overcomes drug efflux mediated by ABC transporters.88 Pharmacologic profiling of DJ101 and DJ95 displays minimal off-target effects, suggesting that their safety profiles will be good. X-ray crystallographic analysis of the T2R–TTL–DJ95 complex (PDB code 6NNG) revealed that the TMP moiety of DJ95 occupies the binding pocket in the tubulin β-subunit, interacting with tubulin residues βY200, βV236, βC239, βC240, βL250, βL253, βA314, βI316, βA352, and βI368.89 Three hydrogen bonds are formed between compound DJ95 and tubulin residues αT179, αD249 and βC239.89

X-ray crystallographic analysis of the reported ABI analogs reveals that only one methoxy group within TMP forms a single hydrogen bond with tubulin residue βC241, as the TMP-binding pocket in the tubulin β-subunit is space limited. It was postulated that the remaining two methoxy groups could be modified for optimized antitumor activity. Compound 34 (Figure 5), in which the two original methoxy groups are replaced with dioxane, exhibits significantly better antiproliferative potency than ABI-231. The crystal structure of T2R–TTL–34 (PDB code 6D88) provides a clear illustration of the compound 34 binding mode, which includes hydrophobic interactions with the tubulin β-subunit, formation of three hydrogen bonds with tubulin, and the straight/curved conformational change. When taken together with the reported structure of the DJ101–tubulin complex, this information suggests that the imidazole and indole moieties in ABI analogs are stacked at the interface of the tubulin α/β-subunits.90

Further modifications of the indole moiety of ABI analog led to compounds 35 and 36 (Figure 5). X-ray crystal structures of T2R–TTL–35 (PDB code 6O5N), T2R–TTL–36 (PDB code 6O5M), and T2R–TTL–ABI-231 (PDB code 6O61) were solved, providing an important framework for further superimposition and docking studies. The indole moiety of compound ABI-231 is stacked in a pocket in tubulin that contacts residues βN256, βM257, βA314, βK350, and αV181. Compound 35 exhibits a binding mode similar to that of ABI-231, whereas the indole moiety of compound 36 contributes to a direct hydrogen bond between the −NH group in 36 and residue βN347 in tubulin. Moreover, this hydrogen bond slightly shifted the position of the TMP moiety in the binding pocket, resulting in a water-bridged hydrogen bond with tubulin residues βG235 and βC239, which may explain the increased potency of compound 36 over other compounds with this scaffold.91

Early attempts to modify the ABI scaffold, including replacing the imidazole ring with six-membered rings, all resulted in decreased potency. However, the X-ray crystal structure of T2R–TTL–ABI-231 implies that a slightly larger central ring moiety may facilitate extension of the compound, potentially allowing it to form extra hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues such as βS178 and βN347. Using a previously reported ABI analog ABI-274 (compound 37, Figure 5) as the starting point, 92 a new series of compounds were synthesized in which the imidazole ring was replaced with a pyridine ring. This led to the discovery of compound 38 (Figure 5), a potent antiproliferative analog with anti-angiogenesis properties. The compound 37 binding mode within the T2R–TTL–37 complex (T2R–TTL–ABI-274; PDB code 6PC4) is similar to that of T2R–TTL–ABI-231. Water-bridged hydrogen bonds are formed between the TMP moiety of compound 37 and tubulin residues βC239 and βG235. The compound 37 keto moiety forms a hydrogen bond with tubulin residue βD249. The imidazole contributes another hydrogen bond, with tubulin αT179, and is stacked between residues βM257, βN256 and αV181. By contrast, the hydroxy group of T2R–TTL–38 (PDB code 6AGK) forms a hydrogen bond with tubulin αV181. The central pyridine ring of compound 38 is larger than an imidazole ring, generating a slight shift of residue αT179 in tubulin that accommodates the binding of this compound.93

Indole derivatives

Molecules that contain indole rings are found in a wide range of natural products that show potential for biological use. Indole-ring-containing drugs have many different therapeutic applications and are used to treat diseases such as leukemia and other cancers, hypertension, depression, psychosis, inflammation, and HIV.94,95 Many ABI analogs contain an indole moiety that is pivotal for their antiproliferative efficacy. To explore the role of this heterocyclic ring in compounds that target the colchicine binding site in tubulin, the indole derivative D64131 (compound 39, Figure 5) was analyzed in complex with T2R–TTL using the crystallographic approach (PDB code 6K9V).96 D64131 binds at the top of the colchicine pocket, hydrophobically interacting with the tubulin β-subunit. The indole nitrogen is critical for the formation of water-bridged hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues βL246, αN101 and αT179. Overall, the indole moiety overlaps well with the C-ring of colchicine. Comparison of D64131 and several reported ABI analogs indicates that the indole moiety can facilitate both hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions with tubulin.96

The colchicine binding site is located at the interface of the α/β-subunits within a tubulin heterodimer, whereas the binding site for vinca is located at the inter-dimer interface. The vinca binding site is targeted by another category of microtubule-destabilizing compounds, namely indole alkaloids such as vinblastine (40, Figure 4) and vincristine (41, Figure 4).97 The (−)-jerantinines A–G are indole alkaloids that were isolated from the flowering plant Tabernaemontana corymbosa. Biological evaluations determined that (−)-jerantinine A (compound 42, Figure 4) and (−)-jerantinine E (compound 43, Figure 4) can destabilize microtubules. Surprisingly, despite having structures that resemble those of vinca alkaloid analogs, these molecules exhibited unexpected cytotoxic effects toward vincristine-resistant cancer cells.98 To reveal the molecular basis of this unexpected result, (−)-jerantinine B acetate (compound 44, Figure 5) was crystallized in complex with T2R–TTL (PDB code 6GF3). The resulting crystal structure showed that these (−)-jerantinines are colchicine site ligands. Their indole moiety overlaps perfectly with the C-ring of colchicine, which corresponds to the binding mode of some of the ABI analogs and D64131 (compound 39, Figure 5).99

CBSIs with a deep binding mode

As described previously, the binding of TN16 (compound 5, Figure 3) to tubulin was initially analyzed in complex with T2R, before the TLL digestion was introduced to the tubulin crystallization method. Although the anilino moiety of TN16 occupies a space in tubulin similar to that occupied by the A-ring in colchicine, the rest of the compound is stacked in a binding pocket that is even deeper within the tubulin structure.28 Additional CBSIs with a similar binding mode were identified with the aid of crystallographic studies with TTL. For example, MI-181 (compound 45, Figure 5) was identified as an M-phase inhibitor that targets tubulin during a high-throughput screen.100 The crystal structure of T2R–TTL–MI–181 (PDB code 4YJ2) indicates that MI-181 is buried deeply within the tubulin β-subunit, in contact with residues βS5 and βS6.101 Many interactions between CBSIs and tubulin involve tubulin residue αT5, but this residue is located too far from the position of MI-181 to interact with it. Instead, a water-bridged hydrogen bond is formed between the thiazole nitrogen of MI-181 and tubulin residue βE200, while direct hydrogen bonds are formed between the thiazole sulfur of MI-181 and tubulin residue βC241 and between the pyridine nitrogen of MI-181 and tubulin residue βN167. Overall, the binding mode of MI-181 is much closer to that of TN16 than to that of colchicine, although MI-181 is still classified as a CBSI. The same report compared the structure of the previously identified CBSI compound 46 (Figure 5)101 bound to tubulin (T2R–TTL–46, PDB code 4YJ3) with that of MI-181. Compound 46 exhibited a binding mode that was similar to that of colchicine. This result indirectly highlights the uniqueness of the TN16-like binding mode, which is demonstrated by compounds with thin and long structures that can fit into the small pocket that extends from the hydrophobic pocket in which the A-ring of colchicine binds. Although tubulin loop αT5 does not directly contact MI-181, MI-181 is closer to loop αT5 than are compounds that exhibit the typical flipped-out conformation adopted by most CBSIs, including compound 46.102

Plinabulin (compound 47, Figure 5) is a synthetic compound derived from the natural product phenylahistin, itself a metabolite of the fungus Aspergillus ustus that inhibits the mammalian cell cycle.103 Previous in silico results suggested that plinabulin is a CBSI that binds at the interface of the tubulin α/β-heterodimer.104 However, this hypothesis was later challenged when the crystal structure of T2R–TTL–plinabulin (PDB code 5C8Y) was analyzed.105 In fact, plinabulin binds much deeper than colchicine, within the β-subunit rather than at the interface of the α and β subunits in the tubulin heterodimer. Plinabulin forms two direct hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues βE198 and βV236 and a water-bridged hydrogen bond with residue αT179. Although plinabulin does indeed target the colchicine binding site of tubulin, only its imidazole moiety overlaps the A-ring of colchicine.105 A recent study solved the high-resolution crystal structures of plinabulin bound to different tubulin isotypes (1.5 Å for βII-tubulin, PDB code 6S8K; 1.8 Å for βIII-tubulin, PDB code 6S8L). Results from the tubulin–DARPin complexes provided insights into the mechanism of tubulin isotype selectivity.106 MBRI-001 (compound 48, Figure 6) was discovered among a series of deuterium-substituted plinabulin derivatives that exhibit improved pharmacokinetic and anticancer properties. Analysis of the crystal structure of T2R–TTL–MBRI-001 (PDB code 5XI5) confirmed that the mode of binding in the interaction between plinabulin derivatives and tubulin shares common features with that of the TN16–tubulin interaction.107

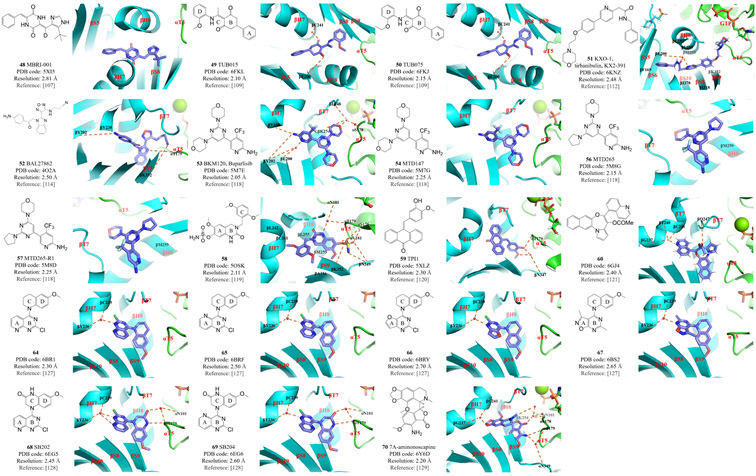

Figure 6: Structures and modes of interaction of inhibitors at the colchicine binding site of tubulin.

The colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) shown here have a deep binding mode (compounds 48–51) or are mentioned in the text under ‘other CBSIs’ (compounds 52–54, 56–60 and 64–70).

Ligand-based virtual screening using TN16 as a query identified the prototype compounds TUB015 (49, Figure 6) and TUB075 (50, Figure 6) as potent CBSIs, both possessing a critical cyclohexanedione scaffold.108 It was therefore hypothesized that these compounds should bind to the colchicine site in a manner that is similar to that of TN16. This predicted result was subsequently confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis of the T2R–TTL–TUB015 (PDB code 6FKL) and T2R–TTL–TUB075 (PDB code 6FKJ) structures.109 Both compounds interact with tubulin residues βS8, βS9, βS10, βT7, βH7, βH8 and αT5. In TUB015 and TUB075 binding, tubulin residue αT5 lies close to the ligand rather than remaining in the flipped out conformation as it does in the common colchicine-like binding mode. The A-ring of TUB015 and TUB075 is deeply buried in a pocket characterized by tubulin residues βI4, βY52, βQ136, βN167, βF169, βE200, βY202, βV238, βT239, βL242 and βL252. The ligand B-ring is located between residues βY202 and βL255. One carbonyl group of the ligand’s central cyclohexanedione moiety forms a hydrogen bond with tubulin residue βE200, while the other participates in a water-bridged hydrogen bond with residue βC241. The ligand D-ring interacts with tubulin residues βL248, βM259, βN258, βA317, βK352, βA354 and αT179 via hydrophobic interactions. Interestingly, these two compounds present the highest binding affinity to tubulin of all reported CBSIs (Kb value of 2.87 × 108 M−1), indicating that the TN16-like binding mode characterized by ligands that are more deeply bound to the tubulin β-subunit may result in better affinity for the colchicine binding site in tubulin.109

KXO-1 (compound 51, Figure 6) exhibits dual inhibitory effects towards the Src kinase signaling pathway and tubulin polymerization.110,111 An X-ray crystallographic study (PDB code 6KNZ) indicates that KXO-1 is a CBSI that occupies a larger footprint at the binding site than does colchicine, and that this footprint overlaps with those of both TN16 and colchicine.112 In addition to forming hydrophobic interactions with tubulin residues βI4, βF169, βL242, βL248, βL252, βL255, βM259, βI318, βI376 and βK352, the KXO-1 morpholine moiety extends to the GTP molecule bound to the tubulin α-subunit, which is not commonly observed in CBSIs. KXO-1 also forms water-bridged hydrogen bonds with tubulin residue βE200. A tryptophan-based binding assay indicates that, like TUB015 and TUB075, KXO-1 exhibits a stronger binding mode than does colchicine.112

Other CBSIs

The CBSI BAL27862 (compound 52, Figure 6) was discovered in high-throughput screens.113 BAL27862 was the first CBSI analyzed using the T2R–TTL crystal complex, which provided high-resolution structures (PDB code 4O2A).114 The structure of T2R–TTL–BAL27862 was compared to that of T2R–TTL–colchicine (PDB code 4O2B), which was later widely used in superimposition studies. BAL27862 targets the same binding site as colchicine, mainly through hydrophobic interactions with tubulin residues βS8, βS9, βT7, βH7, βH8 and αT5 and via hydrogen bonds with residues βY202, βV238, βK352 and αT179. Furthermore, the T2R–TTL–BAL27862 complex allowed the first characterization of the flipped out conformations of the αT5 and βT7 loops relative to their positions in unbound tubulin. This remains a feature common to most CBSIs except the TN16-like molecules that exhibit deep binding modes.114

BKM120 (buparlisib, 53, Figure 6) is a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor that is the subject of multiple clinical studies in which it is used as a single agent or as a component of combination therapies.115,116 General PI3K inhibitors lead to G1/S cell cycle arrest, but at high concentrations, BKM120 also exhibits the off-target effect of disrupting microtubule dynamics, which is considered to be independent of its ability to inhibit PI3K.117 Interestingly, a minor change in the center pyrimidine ring of BKM120 results in the separation of its inhibitory activities against PI3K and microtubules. Replacing the pyrimidine ring with pyridine (MTD147, compound 54, Figure 6) leads to a striking ability to disrupt microtubules with minimal PI3K inhibitory activity. Replacing the pyrimidine ring with a triazine (to form PQR309, compound 55, Figure 4) results in highly specific inhibition of PI3K without disrupting microtubules. Both BKM120 and MTD147 could be crystalized with the T2R–TTL complex (T2R–TTL–BKM120, PDB code 5M7E; T2R–TTL–MTD147, PDB code 5M7G),118 but PQR309 could not, consistent with its role as a PI3K inhibitor that does not affect tubulin. Owing to the limited resolution, however, it is not easy to distinguish nitrogen atoms from the −CH groups of the aromatic ring in these complexes. This difficulty impedes the unambiguous characterization of the positioning of the central ring in the crystal complex. To resolve this issue, MTD265 (compound 56, Figure 6) and MTD265-R1 (compound 57, Figure 6) were synthesized and soaked into the co-crystal with T2R–TTL (T2R–TTL–MTD265, PDB code 5M8G; T2R–TTL–MTD265-R1, PDB code 5M8D).118 The resulting crystal structure highlighted the asymmetry of the compound. It revealed that the morpholino moiety in the crystalline form reaches out toward the GDP molecule, and that it is the −CH group rather than the nitrogen atom in the central ring that interacts with tubulin residue βM259.118 These results indicate that very subtle changes to nitrogen atoms in the central ring within this scaffold have a profound impact on the mode of action. They also show the power of X-ray crystallography in unambiguously solving difficult mechanistic problems in the development of CBSIs.

Compound 58 (Figure 6) is a synthetic molecule with a dihydroquinazolin (DHQ) scaffold. With excellent activity against prostate cancer and breast cancer, compound 58 is the first CBSI with a sulfamate moiety to be studied in a co-crystal with T2R–TTL (PDB code 5OSK).119 Compound 58 forms extensive interactions with tubulin residues βL242, βL255, βC241, βM259, βA316 and βA354. The sulfamate group forms multiple hydrogen bonds with residues βK352, βN349, αS178, αV181 and βN349, further stabilizing the interaction between tubulin and the bound ligand. The B-ring amine also forms water-bridged hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues αN101 and αT179. Superimposition with colchicine-bound tubulin shows that compound 58 has a binding mode that is similar to that of colchicine, although it binds slightly deeper than colchicine.119

An anthracenone derivative, TPI1 (compound 59, Figure 6), was studied in the T2R–TTL–TPI1 complex (PDB code 5XLZ) in order to provide complete structural data to complement the SAR studies of this category of compounds.120 As expected, TPI1 is anchored in the large hydrophobic pocket in the β-subunit of tubulin, forming two hydrogen bonds with tubulin residues αT179 and βN347.120

A novel pyrrolonaphthoxazepine analog, compound 60 (Figure 6), was further modified with a moiety from lead compound PNOX (61, Figure 4). Early attempts to co-crystalize PNOX resulted in failure due to its high lipophilicity. Therefore compound 60 was designed to be less hydrophobic. Owing to its higher solubility, the T2R–TTL–60 (PDB code 6GJ4) co-crystal was successfully obtained and the structure was solved.121 The quinoline and the fused rings engage in hydrophobic interactions with the tubulin β-subunit. Multiple hydrogen bonds and water-bridged interactions are formed between compound 60 and tubulin residues βQ247, βG237, βT240 and βC241.121

Verubulin (compound 62, Figure 4) is a clinical phase 2 compound that exerts strong vascular disruptive activities, shutting down the tumor blood flow and thus restricting tumor growth.122,123 However, its strong potency also brings significant toxicity to the normal cardiovascular system and other normal tissues.124,125 A set of verubulin derivatives with high potency, low toxicity, and high efficacy in overcoming MDR were synthesized using the reported compound 63 (Figure 4) as the lead.126 The four most potent compounds were co-crystallized with T2R–TTL (T2R–TTL–64, PDB code 6BR1; T2R–TTL–65, PDB code 6BRF; T2R–TTL–66, PDB code 6BRY; T2R–TTL–67, PDB code 6BS2; Figure 6). This was the first report of structural data for verubulin analogs in co-crystals with tubulin. Surprisingly, the conclusions of all previously reported in silico studies turned out to be incorrect in terms of the binding mode: the crystal structures showed that these compounds were positioned in the binding site with a 180° flip relative to the predicted positioning. The four compounds bind to the colchicine site with a binding mode similar to that of colchicine: their A- and B-rings occupy the same tubulin β hydrophobic pocket as the TMP moiety of colchicine, and their C- and D-rings are located at the interface of the tubulin dimer. A critical water-bridged interaction between the B-ring 1-nitrogen and tubulin residues βC239 and βV236 provides a solid foundation to explain why this atom is indispensable for the activity of verubulin analogs.127 Furthermore, docking studies based on the crystal data from T2R–TTL–64 indicate that tubulin residue αT179 in the αT5 loop, which commonly forms hydrogen bonds with numerous CBSIs, is positioned very close to the benzyl carbon of compound 64. It was hypothesized that replacing this carbon with a hydrogen bond donor moiety (such as an amide) would provide a new hydrogen bonding interaction that would strengthen the binding to tubulin. To test this hypothesis, SB202 (68, Figure 6) and SB204 (69, Figure 6) were designed and the crystal structures of these compounds in complexes with tubulin were solved (SB202, PDB code 6EG5; SB204, PDB code 6EG6).128 As expected, the amide moiety that was newly introduced into both compounds forms a hydrogen bond with residue αT179 of tubulin. As an added benefit, the carbonyl oxygen in this amide also forms another water-bridged hydrogen bond with residue αN101. Consequently, both compounds 68 and 69 are more potent and more metabolically stable than their parental compound 64.128 These results clearly demonstrate the power of X-ray crystallography and highlight its utility in the development of CBSIs, particularly when given the high flexibility of the colchicine binding site.

7A-aminonoscapine (compound 70, Figure 6) is a synthetic analog of noscapine, which is a natural product extracted from opium. A recent study confirmed the hypothesis that compound 70 binds to the colchicine site, when co-crystals with T2R–TTL were obtained and the structure solved at 2.2 Å resolution (T2R–TTL–70, PDB code 6Y6D).129 This result shows that compound 70 fits into the colchicine pocket, where it forms multiple water-bridged hydrogen bonds. This study also suggested the important role of the two loops in the colchicine site, as superimposition of compound 70 with colchicine reveals that these two ligands perturb the loops in tubulin in a similar way.129

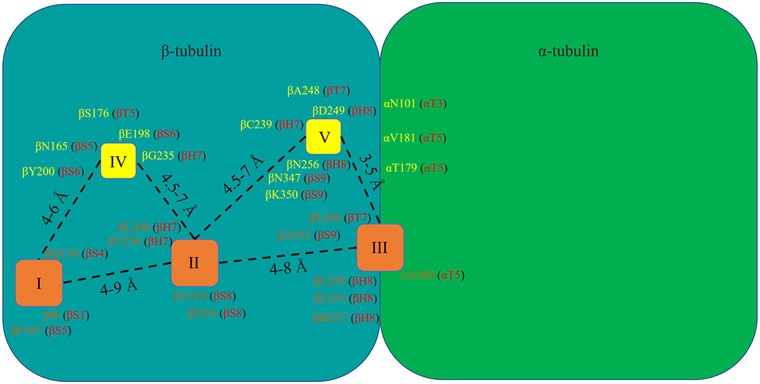

Summary of the colchicine binding site

Analyses of the crystal structures of CBSIs in complex with tubulin allow us to construct a picture that summarizes the colchicine binding site (Figure 7). The colchicine binding site contains three hydrophobic pockets that serve as the main locations for ligand interactions, as well as two hydrophilic sites that are prone to forming additional hydrogen bonds with ligands that add stability to the interactions.105 Hydrophobic pocket I is the main target for compounds in the ‘deep binding mode’ category, whereas hydrophobic pocket II is the major CBSI binding pocket. Hydrophobic pocket II is occupied by the TMP moiety of numerous CBSIs (such as combretastatin A analogs and ABI analogs). Hydrophobic pocket III is located at the interface of the α/β-subunit. The details of these pockets and the locations of major residues surrounding them are provided in Figure 7. Our current understanding of CBSIs and their interactions with tubulin will be further advanced as the co-crystal structures of newly designed diverse CBSIs become available in the future. We anticipate that the current picture will be further refined as we pursue the goal of contributing a useful tool to this research field.

Figure 7: Critical pockets and residues of the colchicine binding site in tubulin.

The three hydrophobic centers and residues that participate in hydrophobic interactions with colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) are shown in brown. The two hydrophilic centers and residues that participate in hydrophilic interactions with CBSIs are shown in yellow.

Conclusions, challenges, and future directions

Tubulin plays a pivotal role in cancer therapy. Although modeling has been extensively applied in tubulin–ligand studies,130 crystallography of T2R complexes at 4 Å resolution offered a more practicable way to explore detailed tubulin–ligand interactions. High-resolution T2R structures were obtained in which the tubulin dimers were cleaved with subtilisin prior to complex formation and crystallization. The advent of the T2R–TTL complex further improved the resolution to ~2–3 Å, which greatly emphasized the power of X-ray crystallography in significantly facilitating efficient structural optimization. The conformation of the maytansine site, one of the binding sites in tubulin, was unambiguously confirmed after the crystal structure of T2R–TTL–maytansine (PDB code 4TV8) was solved, proposing a new direction for the rational design of MTAs.131 Moreover, information on the structure of crystals assists in improving the accuracy of modeling and facilitates rational drug design. X-ray crystallography studies of verubulin analogs,127 as well as on other structurally diverse CBSIs (such as lexibulin, nocodazole, plinabulin and tivantinib), have also corrected previously reported binding modes that were predicted using molecular docking studies. Given that different binding modes generate different hypotheses and thus different directions for structural optimization, the experimental identification of the true binding modes for CBSIs is critical.

The crystallography technique itself has also seen remarkable innovation alongside the evolution of the crystallization strategy discussed in this review. For example, femtosecond X-ray protein nano-crystallography at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) significantly reduce the restrictions on crystal size when compared with traditional X-ray crystallography.132 Further, serial millisecond crystallography at synchrotrons was reported to waive the need for the scarce beamtime of XFELs.133 Overall, these advances in crystallography techniques allow researchers to solve the structures of macromolecules with fewer limitations on temperature, higher flexibility of energy source, and more importantly, more tolerance for crystallization.134

Although tubulin is relatively small and the quality of its crystal structure has already been greatly optimized, a major challenge is to gain new insights into the various isotypes and differential tissue distributions of tubulin. To date, seven isotypes of α-tubulin and nine isotypes of β-tubulin that are expressed in a tissue-dependent manner have been identified.135 Moreover, the chemotherapy itself may also influence accumulation of tubulin escape mutations through the application of selective pressure, particularly given the unstable nature of cancer cells and their potential to develop drug resistance in a stochastic manner.136,137 Most tubulin crystallography studies have been performed on tubulin proteins obtained from brain tissue, which may not adequately represent the tubulin isotypes and differential tissue distributions found in diverse tumor types. It is important to know that crystallography studies provide a snapshot of drug–tubulin interactions in a static (crystallized) state that may not always reflect their natural physiological and dynamic state. This is especially important for the colchicine binding site because the αT5 and βT7 loops in tubulin are highly flexible and exquisitely dependent on the exact chemical structure of a CBSI. Thus, simply advancing the crystallography technique itself may not further aid tubulin-related studies such as the discovery of new CBSIs.

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has raised a technical revolution in the past decade in the field of structural biology. Compared to X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM is generally suitable for detecting macromolecules with molecular weights larger than 200 kDa, as there will be a loss of resolution if the molecules are too small. Regardless, cryo-EM remains a powerful structural determination tool because of its abilities to capture proteins in their native solution state and to document conformational changes, both of which are critical features that will meet the future needs of tubulin structural studies.138 A 4.2 Å resolution cryo-EM structure revealed how microtubule dynamics are affected by different tubulin isotypes.139 In addition, numerous microtubule-binding domains have been determined through 3D reconstruction based on cryo-EM imaging.140 Granted, these studies may only serve tubulin research on a larger scale (microtubule binding domains versus tubulin binding domains) with lower resolution (4.2 Å versus 2–3 Å), but the resolution of cryo-EM has improved in recent years.141,142 It has been suggested that both X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM have unique advantages and that, in many ways, their data complement one another.143 Therefore, it is anticipated that the powerful and reliable approaches of X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM will be used together for future CBSI discoveries.

Highlights:

Colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) are less susceptible to multidrug resistance compared with current FDA-approved tubulin inhibitors.

Due to the high flexibility of the loops at the colchicine binding site, high-resolution X-ray crystal structures can provide realistic pictures of molecular interactions.

Since the first reported CBSI-tubulin co-crystal structure in 2004, X-ray crystallography has advanced significantly and facilitated the design of novel CBSIs.

The chemical structures of CBSIs are often suitable for X-ray crystallography guided optimization for drug-like properties, oral bioavailability, and dual targeting.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for financial support from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH, grant number 1R01CA148706), and the US Department of Defense (grant number W81XWH2010011). We appreciate the editorial assistance provided by Dr Kyle Johnson Moore.

Biography

Jiaxing Wang obtained his BS and MS degrees from Peking University Health Science Center (Beijing, China) before joining Dr Li’s lab at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC), Memphis, TN, USA in 2019. His current research focuses on evaluating new generations of tubulin inhibitors developed in Dr Li’s lab.

Dr Duane D. Miller received his Ph.D. degree in Medicinal Chemistry in 1969 from the University of Washington. He began his academic career at The Ohio State University and moved in 1992 to join the University to Tennessee College of Pharmacy (UTCoP). He retired in 2015 and is currently Professor Emeritus at UTHSC. His interests in drug design and the synthesis of new drug molecules continue, with a focus on tubulin inhibitors and drugs that act on the androgen receptor. His drugs for the treatment of prostate and breast cancers are currently in clinical trials.

Dr Wei Li obtained his BS degree in chemistry from the University of Science and Technology of China in 1992, and PhD degree from Columbia University in 1999. He has been working at the UTHSC College of Pharmacy since 1999. At present, he is a UTHSC Distinguished Professor, Director of UTCoP Drug Discovery Center, and the Faculty Director of the UTCoP Shared Instrument Facility. His research interest is in small molecule drug discovery and he currently has one drug in Phase 2 clinical trials. He is also the Founder and CSO of SEAK Therapeutics LLC, a UTHSC spin-off startup company.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

W.L. is a scientific consultant for Veru, Inc., which licensed one of the CBSIs described in this manuscript, VERU-111, for commercial development. W.L. and D.D.M. have also received sponsored research agreement grants from Veru, Inc., but this company had no input or influence in the collection or analysis of data or in the writing of this manuscript. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by J.W.

References

- 1.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Cancer stat facts: cancer of any site. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html. Published 2020. Accessed January 4, 2021.

- 2.Naaz F, Haider MR, Shafi S, Yar MS. Anti-tubulin agents of natural origin: targeting taxol, vinca, and colchicine binding domains. Eur J Med Chem 2019; 171: 310–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Islam MN, Iskander MN. Microtubulin binding sites as target for developing anticancer agents. Mini Rev Med Chem 2004; 4: 1077–104. doi: 10.2174/1389557043402946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1997; 13: 83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang P, Stearns T. Delta-tubulin and epsilon-tubulin: two new human centrosomal tubulins reveal new aspects of centrosome structure and function. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2: 30–5. doi: 10.1038/71350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez AD, Feldman JL. Microtubule-organizing centers: from the centrosome to non-centrosomal sites. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2017; 44: 93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLoughlin EC, O'Boyle NM. Colchicine-binding site inhibitors from chemistry to clinic: a review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2020; 13: 8. doi: 10.3390/ph13010008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horio T, Murata T. The role of dynamic instability in microtubule organization. Front Plant Sci 2014; 5: 511. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnst KE, Banerjee S, Chen H, Deng S, Hwang D, Li W, Miller DD. Current advances of tubulin inhibitors as dual acting small molecules for cancer therapy. Med Res Rev 2019; 39: 1398–426. doi: 10.1002/med.21568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W, Sun H, Xu S, Zhu Z, Xu J. Tubulin inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site: a perspective of privileged structures. Future Med Chem 2017; 9: 1765–94. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muhlethaler T, Gioia D, Prota AE, Sharpe ME, Cavalli A, Steinmetz MO. Comprehensive analysis of binding sites in tubulin. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2021; 60: 13331–42. doi: 10.1002/anie.202100273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Lin Z, Arnst KE, Miller DD, Li W. Tubulin inhibitor-based antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Molecules 2017; 22: 1281. doi: 10.3390/molecules22081281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Y, Chen J, Xiao M, Li W, Miller DD. An overview of tubulin inhibitors that interact with the colchicine binding site. Pharm Res 2012; 29: 2943–71. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0828-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amos LA, Jubb JS, Henderson R, Vigers G. Arrangement of protofilaments in two forms of tubulin crystal induced by vinblastine. J Mol Biol 1984; 178: 711–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90248-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi TC, Sato H. Yields of tubulin paracrystals, vinblastine-crystals, induced in unfertilized and fertilized sea urchin eggs in the presence of D2O. Cell Struct Funct 1984; 9: 45–52. doi: 10.1247/csf.9.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Khan IA, Luduena RF, Downing KH. Structure of tubulin at 6.5 A and location of the taxol-binding site. Nature 1995; 375: 424–7. doi: 10.1038/375424a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH. Visualizing the secondary structure of tubulin: three-dimensional map at 4 A. J Struct Biol 1997; 118: 119–27. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH. Structure of the alpha beta tubulin dimer by electron crystallography. Nature 1998; 391: 199–203. doi: 10.1038/34465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobel A, Boutterin MC, Beretta L, Chneiweiss H, Doye V, Peyro-Saint-Paul H. Intracellular substrates for extracellular signaling. Characterization of a ubiquitous, neuron-enriched phosphoprotein (stathmin). J Biol Chem 1989; 264: 3765–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozon S, Maucuer A, Sobel A. The stathmin family—molecular and biological characterization of novel mammalian proteins expressed in the nervous system. Eur J Biochem 1997; 248: 794–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-2-00794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jourdain L, Curmi P, Sobel A, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. Stathmin: a tubulin-sequestering protein which forms a ternary T2S complex with two tubulin molecules. Biochemistry 1997; 36: 10817–21. doi: 10.1021/bi971491b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gavet O, Ozon S, Manceau V, Lawler S, Curmi P, Sobel A. The stathmin phosphoprotein family: intracellular localization and effects on the microtubule network. J Cell Sci 1998; 111 :3333–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gradin HM, Larsson N, Marklund U, Gullberg M. Regulation of microtubule dynamics by extracellular signals: cAMP-dependent protein kinase switches off the activity of oncoprotein 18 in intact cells. J Cell Biol 1998; 140: 131–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinmetz MO, Kammerer RA, Jahnke W, Goldie KN, Lustig A, van Oostrum J. Op18/stathmin caps a kinked protofilament-like tubulin tetramer. EMBO J 2000; 19: 572–80. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gigant B, Curmi PA, Martin-Barbey C, Charbaut E, Lachkar S, Lebeau L, et al. The 4 A X-ray structure of a tubulin:stathmin-like domain complex. Cell 2000; 102: 809–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00069-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravelli RB, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, Knossow M. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature 2004; 428: 198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature02393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorleans A, Knossow M, Gigant B. Studying drug-tubulin interactions by X-ray crystallography. Methods Mol Med 2007; 137: 235–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-442-1_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorleans A, Gigant B, Ravelli RB, Mailliet P, Mikol V, Knossow M. Variations in the colchicine-binding domain provide insight into the structural switch of tubulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 13775–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904223106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang HW, Nogales E. Nucleotide-dependent bending flexibility of tubulin regulates microtubule assembly. Nature 2005; 435: 911–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nogales E, Wang HW. Structural mechanisms underlying nucleotide-dependent self-assembly of tubulin and its relatives. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2006; 16: 221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aldaz H, Rice LM, Stearns T, Agard DA. Insights into microtubule nucleation from the crystal structure of human gamma-tubulin. Nature 2005; 435: 523–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlieper D, Oliva MA, Andreu JM, Löwe J. Structure of bacterial tubulin BtubA/B: evidence for horizontal gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102: 9170–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502859102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buey RM, Diaz JF, Andreu JM. The nucleotide switch of tubulin and microtubule assembly: a polymerization-driven structural change. Biochemistry 2006; 45: 5933–8. doi: 10.1021/bi060334m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice LM, Montabana EA, Agard DA. The lattice as allosteric effector: structural studies of alphabeta- and gamma-tubulin clarify the role of GTP in microtubule assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105: 5378–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801155105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gebremichael Y, Chu JW, Voth GA. Intrinsic bending and structural rearrangement of tubulin dimer: molecular dynamics simulations and coarse-grained analysis. Biophys J 2008; 95: 2487–99. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett MJ, Chik JK, Slysz GW, Luchko T, Tuszynski J, Sackett DL, Schriemer DC. Structural mass spectrometry of the alpha beta-tubulin dimer supports a revised model of microtubule assembly. Biochemistry 2009; 48: 4858–70. doi: 10.1021/bi900200q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbier P, Dorleans A, Devred F, Sanz L, Allegro D, Alfonso C, et al. Stathmin and interfacial microtubule inhibitors recognize a naturally curved conformation of tubulin dimers. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 31672–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nawrotek A, Knossow M, Gigant B. The determinants that govern microtubule assembly from the atomic structure of GTP-tubulin. J Mol Biol 2011; 412: 35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pecqueur L, Duellberg C, Dreier B, Jiang Q, Wang C, Plückthun A, et al. A designed ankyrin repeat protein selected to bind to tubulin caps the microtubule plus end. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109: 12011–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204129109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prota AE, Magiera MM, Kuijpers M, Bargsten K, Frey D, Wieser M, et al. Structural basis of tubulin tyrosination by tubulin tyrosine ligase. J Cell Biol 2013; 200: 259–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prota AE, Bargsten K, Zurwerra D, Field JJ, Díaz JF, Altmann KH, Steinmetz MO. Molecular mechanism of action of microtubule-stabilizing anticancer agents. Science 2013; 339: 587–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1230582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murofushi H. Purification and characterization of tubulin-tyrosine ligase from porcine brain. J Biochem 1980; 87: 979–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ersfeld K, Wehland J, Plessmann U, Dodemont H, Gerke V, Weber K. Characterization of the tubulin-tyrosine ligase. J Cell Biol 1993; 120: 725–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westermann S, Weber K. Post-translational modifications regulate microtubule function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003; 4: 938–47. doi: 10.1038/nrm1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szyk A, Deaconescu AM, Piszczek G, Roll-Mecak A. Tubulin tyrosine ligase structure reveals adaptation of an ancient fold to bind and modify tubulin. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011; 18: 1250–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamel E, Lin CM. Interactions of combretastatin, a new plant-derived antimitotic agent, with tubulin. Biochem Pharmacol 1983; 32: 3864–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90163-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pettit GR, Singh SB, Niven ML, Hamel E, Schmidt JM. Isolation, structure, and synthesis of combretastatins A-1 and B-1, potent new inhibitors of microtubule assembly, derived from Combretum caffrum. J Nat Prod 1987; 50: 119–31. doi: 10.1021/np50049a016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettit GR, Singh SB, Schmidt JM, Niven ML, Hamel E, Lin CM. Isolation, structure, synthesis, and antimitotic properties of combretastatins B-3 and B-4 from Combretum caffrum. J Nat Prod 1988; 51: 517–27. doi: 10.1021/np50057a011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pettit GR, Singh SB, Hamel E, Lin CM, Alberts DS, Garcia-Kendall D. Isolation and structure of the strong cell growth and tubulin inhibitor combretastatin A-4. Experientia 1989; 45: 209–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01954881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pettit GR, Singh SB, Boyd MR, Hamel E, Pettit RK, Schmidt JM, Hogan F. Antineoplastic agents. 291. Isolation and synthesis of combretastatins A-4, A-5, and A-6(1a). J Med Chem 1995; 38: 1666–72. doi: 10.1021/jm00010a011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tron GC, Pirali T, Sorba G, Pagliai F, Busacca S, Genazzani AA. Medicinal chemistry of combretastatin A4: present and future directions. J Med Chem 2006; 49: 3033–44. doi: 10.1021/jm0512903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seddigi ZS, Malik MS, Saraswati AP, Ahmed SA, Babalghith AO, Lamfon HA, Kamal A. Recent advances in combretastatin based derivatives and prodrugs as antimitotic agents. Medchemcomm 2017; 8: 1592–603. doi: 10.1039/c7md00227k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shan Y, Zhang J, Liu Z, Wang M, Dong Y. Developments of combretastatin A-4 derivatives as anticancer agents. Curr Med Chem 2011; 18: 523–38. doi: 10.2174/092986711794480221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nainwal LM, Alam MM, Shaquiquzzaman M, Marella A, Kamal A. Combretastatin-based compounds with therapeutic characteristics: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2019; 29: 703–31. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1651841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bukhari SNA, Kumar GB, Revankar HM, Qin HL. Development of combretastatins as potent tubulin polymerization inhibitors. Bioorg Chem 2017; 72: 130–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piekus-Slomka N, Mikstacka R, Ronowicz J, Sobiak S. Hybrid cis-stilbene molecules: novel anticancer agents. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 1300. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cushman M, Nagarathnam D, Gopal D, Chakraborti AK, Lin CM, Hamel E. Synthesis and evaluation of stilbene and dihydrostilbene derivatives as potential anticancer agents that inhibit tubulin polymerization. J Med Chem 1991; 34: 2579–88. doi: 10.1021/jm00112a036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettit GR, Rhodes MR, Herald DL, Hamel E, Schmidt JM, Pettit RK. Antineoplastic agents. 445. Synthesis and evaluation of structural modifications of (Z)- and (E)-combretastatin A-41. J Med Chem 2005; 48: 4087–99. doi: 10.1021/jm0205797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaspari R, Prota AE, Bargsten K, Cavalli A, Steinmetz MO. Structural basis of cis- and trans-combretastatin binding to tubulin. Chem 2017; 2: 102–13. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2016.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lai Q, Wang Y, Wang R, Lai W, Tang L, Tao Y, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of a novel tubulin inhibitor 7a3 targeting the colchicine binding site. Eur J Med Chem 2018; 156: 162–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang J, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhang Q, Fang S, Zhou R, et al. 1-Phenyl-dihydrobenzoindazoles as novel colchicine site inhibitors: structural basis and antitumor efficacy. Eur J Med Chem 2019; 177: 448–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carr M, Greene LM, Knox AJ, Lloyd DG, Zisterer DM, Meegan MJ. Lead identification of conformationally restricted beta-lactam type combretastatin analogues: synthesis, antiproliferative activity and tubulin targeting effects. Eur J Med Chem 2010; 45: 5752–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Boyle NM, Carr M, Greene LM, Bergin O, Nathwani SM, McCabe T, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of azetidinone analogues of combretastatin A-4 as tubulin targeting agents. J Med Chem 2010; 53: 8569–84. doi: 10.1021/jm101115u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tripodi F, Pagliarin R, Fumagalli G, Bigi A, Fusi P, Orsini F, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 1,4-diaryl-2-azetidinones as specific anticancer agents: activation of adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase and induction of apoptosis. J Med Chem 2012; 55: 2112–24. doi: 10.1021/jm201344a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greene TF, Wang S, Greene LM, Nathwani SM, Pollock JK, Malebari AM, et al. Synthesis and biochemical evaluation of 3-phenoxy-1,4-diarylazetidin-2-ones as tubulin-targeting antitumor agents. J Med Chem 2016; 59: 90–113. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou P, Liu Y, Zhou L, Zhu K, Feng K, Zhang H, et al. Potent antitumor activities and structure basis of the chiral beta-lactam bridged analogue of combretastatin A-4 binding to tubulin. J Med Chem 2016; 59: 10329–34. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou P, Liang Y, Zhang H, Jiang H, Feng K, Xu P, et al. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and cocrystal structures with tubulin of chiral beta-lactam bridged combretastatin A-4 analogues as potent antitumor agents. Eur J Med Chem 2018; 144: 817–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Edwards ML, Stemerick DM, Sunkara PS. Chalcones: a new class of antimitotic agents. J Med Chem 1990; 33: 1948–54. doi: 10.1021/jm00169a021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ducki S, Mackenzie G, Lawrence NJ, Snyder JP. Quantitative structure–activity relationship (5D-QSAR) study of combretastatin-like analogues as inhibitors of tubulin assembly. J Med Chem 2005; 48: 457–65. doi: 10.1021/jm049444m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lawrence NJ, Rennison D, McGown AT, Ducki S, Gul LA, Hadfield JA, Khan N. Linked parallel synthesis and MTT bioassay screening of substituted chalcones. J Comb Chem 2001; 3: 421–6. doi: 10.1021/cc000075z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ducki S, Forrest R, Hadfield JA, Kendall A, Lawrence NJ, McGown AT, Rennison D. Potent antimitotic and cell growth inhibitory properties of substituted chalcones. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 1998; 8: 1051–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00162-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ducki S, Rennison D, Woo M, Kendall A, Chabert JF, McGown AT, Lawrence NJ. Combretastatin-like chalcones as inhibitors of microtubule polymerization. Part 1: synthesis and biological evaluation of antivascular activity. Bioorg Med Chem 2009; 17: 7698–710. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ducki S, Mackenzie G, Greedy B, Armitage S, Chabert JF, Bennett E, et al. Combretastatin-like chalcones as inhibitors of microtubule polymerisation. Part 2: structure-based discovery of alpha-aryl chalcones. Bioorg Med Chem 2009; 17: 7711–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Canela MD, Noppen S, Bueno O, Prota AE, Bargsten K, Sáez-Calvo G, et al. Antivascular and antitumor properties of the tubulin-binding chalcone TUB091. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 14325–42. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu W, Ye H, Wan L, Han X, Wang G, Hu J, et al. Millepachine, a novel chalcone, induces G2/M arrest by inhibiting CDK1 activity and causing apoptosis via ROS-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in human hepatocarcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Carcinogenesis 2013; 34: 1636–43. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ye H, Fu A, Wu W, Li Y, Wang G, Tang M, et al. Cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of constituents from Millettia pachycarpa Benth. Fitoterapia 2012; 83: 1402–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]