Abstract

Background

Tbr1 encodes a T-box transcription factor and is considered a high confidence autism spectrum disorder (ASD) gene. Tbr1 is expressed in the postmitotic excitatory neurons of the deep neocortical layers 5 and 6. Postnatally and neonatally, Tbr1 conditional mutants (CKOs) have immature dendritic spines and reduced synaptic density. However, an understanding of Tbr1’s function in the adult mouse brain remains elusive.

Methods

We used conditional mutagenesis to interrogate Tbr1’s function in cortical layers 5 and 6 of the adult mouse cortex.

Results

Adult Tbr1 CKO mutants have dendritic spine and synaptic deficits as well as reduced frequency of mEPSCs and mIPSCs. LiCl, a WNT signaling agonist, robustly rescues the dendritic spine maturation, synaptic defects, and excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission deficits.

Conclusions

LiCl treatment could be used as a therapeutic approach for some cases of ASD with deficits in synaptic transmission.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s11689-022-09421-5.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Tbr1, Dendritic spine, Synaptogenesis, Excitatory neuron, Cortex, Synaptic transmission, Synaptic rescue, mPFCx

Introduction

Genetic heterogeneity and phenotypic pleiotropy have complicated efforts in understanding the underlying biology of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [1, 2]. Whole-genome and exome sequencing has revealed 102 high confidence ASD (hcASD) risk genes (FDR < 0.1) [3]. Systems analyses suggest that the expression of ASD risk genes have important functions in mid-fetal deep layer cortical excitatory neurons and that disruption may contribute to ASD pathophysiology [2]. The hcASD-risk genes fall into two major categories of gene expression regulators and synaptic genes [1, 3, 4]. However, an actionable understanding of whether ASD-risk gene expression regulators control and/or contribute to synaptic pathophysiology remains unclear.

Genetic analyses of patients with ASD have identified TBR1 as a high confidence risk factor for ASDs [2, 4–6]. Analyses of co-expression networks of ASD-risk genes provide evidence that reduced dosage of genes, such as Tbr1, may underlie ASD by disrupting processes in immature projection neurons of deep cortical layers during human mid-fetal development [2]. To date, there are 5 de novo loss-of-function mutations in TBR1 that are associated with ASD [7]. Two of the TBR1 de novo mutations generate truncated proteins that lack a functional DNA-binding T-box domain [4]. These two truncated TBR1 mutants lose their ability to regulate transcription, have an altered intracellular distribution, and fail to interact with other proteins including CASK [8, 9] and FOXP2 [7]. Thus, analysis of the Tbr1 transcription factor (TF) has opened the possibility of defining a transcriptional pathway that contributes to ASD pathology [5, 6].

Tbr1 has a central role in the development of mouse early-born excitatory cortical neurons. Tbr1 expression, which begins in newborn neurons, dictates layer 6 identity by repressing Fezf2 and Bcl11b, transcription factors that control layer 5 fate [10–14]. We previously demonstrated that young adult (P56) Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKO mutants have reduced dendritic spine density as well as reduced excitatory and inhibitory synaptic density [15, 16]. Furthermore, we demonstrated that Tbr1 mutant layer 5 and 6 cortical neurons have reduced WNT signaling that underlies their defects in dendritic spines and synaptic density. Consistent with this, lithium chloride (LiCl) treatment, or inhibition of GSK3β, rescued these defects [15]. LiCl is an FDA-approved drug that promotes WNT signaling [17–19].

Towards evaluating whether LiCl rescue could be relevant for the treatment of human TBR1 mutant patients, we evaluated whether Tbr1 mutant mice have (1) dendritic spine and synaptic deficits that persist into adulthood, (2) whether LiCl treatment can rescue the phenotype in the older animals, and (3) whether LiCl treatment rescued synaptic transmission. Here, we demonstrate that adult Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKO mutants have dendritic spine and synaptic density deficits. Furthermore, adult Tbr1 CKO mutants have reduced mEPSC and mIPSC frequencies. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that the LiCl rescue of the spine and synaptic density in the Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKO mutants is sustained 6 months after the LiCl injection, which indicates the long-term efficacy of LiCl treatment on rescuing spine and synaptic density deficits. Lastly, we show that LiCl rescues the spine and synaptic defects in adult Tbr1 CKOs, which may have therapeutic implications for ASD patients with either mutations in TBR1 or for cases with impaired synaptic function.

Materials and methods

Animals

All procedures and animal care were approved and performed in accordance with the University of California San Francisco Laboratory Animal Research Center (LARC) guidelines (Animal protocol # AN180174-03B). All strains were maintained on a C57Bl/6 background. Animals were housed in a vivarium with a 12-h light (7 am to 7 pm), 12-h dark cycle. Animals were tested during the light cycle. Experimental animals were kept with their littermates.

The Tbr1flox allele was generated by the inGenious Targeting Laboratory (Ronkonkoma, NY). LoxP sites were inserted into introns 1 and 3, flanking Tbr1 exons 2 and 3 [16]. To enable the selection of homologous recombinants, the LoxP site in intron 3 was embedded in a neo cassette that was flanked by Flp sites. The neo cassette was removed by mating to a Flp-expressing mouse to generate the Tbr1flox allele. Cre excision removes exons 2 and 3, including the T-box DNA binding region, similar to the constitutive null allele [13]. Rbp4-cre (Gensat KL100) and Ntsr1-cre (Gensat 220) mice were used to delete Tbr1 in layer 5 and layer 6 projection neurons, respectively. tdTomatofl/+ (Ai14) mice were crossed with Tbr1f/f mice and used as an endogenous reporter. Tbr1 layer 5 and layer 6 conditional knockout mice were generated as previously described [15, 16].

Transgenic animal models

The mouse strains used for this research project, B6.FVB (Cg)-Tg (Ntsr1-cre)GN220Gsat/Mmucd, RRID:MMRRC_030648-UCD, and B6.FVB (Cg)-Tg (Rbp4-cre)KL100Gsat/Mmucd, RRID:MMRRC_037128-UCD were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Resource and Research Center (MMRRC) at the University of California at Davis, an NIH-funded strain repository, and was donated to the MMRRC by MMRRC at UCD, University of California, Davis. Made from the original strain (MMRRC:032081) donated by Nathaniel Heintz, Ph.D., The Rockefeller University, GENSAT https://protect2.fireeye.com/url?k=c19cddd3-9ddce8ed-c19cface-0cc47ad9c120-2678b1e782f452c7&u=http://www.gensat.org/ and Charles Gerfen, Ph.D., National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health.

Information about the generation and genotyping of the transgenic lines used in this study can be found in the corresponding original studies: Rbp4-Cre [20], lox-STOP-lox-tdTomato (Ai14; [21]). Mice were maintained on C57BL/6J background.

Genomic DNA extraction and genotyping

Tail clippings were digested in a solution containing 1 mg/mL of proteinase K, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, and 1% SDS. Genomic DNA was extracted using a standard ethanol precipitation protocol. Genotyping was performed with PCR-based assays using purified genomic DNA and primer-pair combinations flanking the deleted region and detecting Cre and tdTomato alleles.

In vivo synapse rescue assay

We performed in vivo rescue assay of synaptic deficit in Tbr1 mutant mice by using a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of LiCl to rescue the decrease in synapse numbers in Tbr1 mutants. P180 mice were administered a single IP injection of 400 mg/kg LiCl or saline in a volume of 4 ml/kg [18]. A separate cohort of P30 mice was administered a single IP injection of 400 mg/kg LiCl or saline in a volume of 4 ml/kg. Treated mice were anesthetized and perfused 6 months after LiCl injection, as described below.

Histology

Animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine containing 15 mg/kg xylazine. Animals were then perfused transcardially with ice-cold 1× PBS and then with 4% PFA in 1× PBS, followed by brain isolation, 1–2 h post-fixation in 4% PFA in 1X PBS at RT, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 1× PBS overnight at 4 °C, and cut frozen coronally on a sliding microtome at 40 μm for immunohistochemistry. All primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 1× PBS containing 10% normal serum, 0.25% Triton X-100, and 2% BSA. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-Vglut1 (1:200, Synaptic Systems; RRID: AB_887875), rabbit anti-Vgat (1:500, Synaptic Systems; RRID: AB_887871), rabbit anti-PSD95 (1:200, Cell Signaling; RRID: AB_2307331), and mouse anti-gephyrin (1:200, Synaptic Systems; RRID: AB_887717). The secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence were goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000, Thermo Fisher; RRID: AB_143165) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (1:1000, Thermo Fisher; RRID: AB_2633277). For in vivo synapse immunohistochemistry, a total of n = 10 apical dendrites were counted from each of Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer5 homozygous mutants of mixed gender. The coronal sections were pre-treated with pepsin to enhance the staining. Immunofluorescence specimens were counterstained with 1% DAPI to assist the delineation of cortical layers.

Image acquisition and analysis

Fluorescent and bright-field images were taken using a Coolsnap camera (Photometrics) mounted on a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope using the NIS Elements acquisition software (Nikon). Confocal imaging experiments were conducted at the Cancer Research Laboratory (CRL) Molecular Imaging Center, supported by Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute at UC Berkeley. Confocal images were acquired using Zeiss LSM 880 with Airyscan with a 63X oil objective at 1024 × 1024 pixels resolution with 2.0X optical zoom using the ZEN 2.0 software. The 2.0X optical zoom allowed a higher magnification to visualize the dendritic spines prior to imaging. Brightness and contrast were adjusted, and images merged using the Fiji ImageJ software. The Fiji ImageJ software was used for image processing [22, 23]. For synapse counting (presynaptic and postsynaptic boutons), confocal image stacks (0.4μm step size) were processed with the Fiji ImageJ software. In brief, background subtraction and smooth filter were applied to each stack. Using a threshold function, each stack was converted into a “mask” image. Furthermore, the channels were co-localized with the Image Calculator plugging. Lastly, the number of co-localizations were counted, and the length of each dendrite was measured in each of the focal plane. Staining for control and mutant were done in parallel as well as the image capturing.

Ex vivo electrophysiology

Tbr1 layer5 ::Rbp4-Cre::tdTomato and Tbr1layer6::Ntsr1-Cre::tdTomato homozygous conditional knockout mice and wild-type littermates were administered a single, intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 400 mg/kg LiCl or 4 ml/kg of saline at P30. Mice aged P70-110 were anesthetized under isoflurane. Brains were dissected and placed in 4 °C cutting solution consisting of (in mM) 87 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 75 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, and 7 MgCl2 and bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2. Coronal slices 250-μm-thick were obtained that included the medial prefrontal cortex or the somatosensory cortex. Slices were then incubated in a holding chamber with sucrose solution for 30 mins at 33 °C, then placed at room temperature until recording. External aCSF recording solution consisted of (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 25 glucose, approximately 310 mOsm, bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2, and maintained at 32–34 °C. Miniature excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs, mIPSCs) were measured in the presence of 10 μM R-CPP and 400 nM TTX. td-Tomato-positive neurons were identified using a Rolera-XR camera and conventional whole-cell patch clamp was conducted under differential interference contrast (DIC) optics.

mEPSC and mIPSC recordings were performed in voltage-clamp using glass patch electrodes (Schott 8250, 3–4 MΩ tip resistance) filled with a CsCl-based internal solution that contained (in mM): 110 CsMeSO3, 40 HEPES, 1 KCl, 4 CaCl, 4 Mg-ATP, 10 Na-phosphocreatine, 0.4 Na2-GTP, 5 QX-314, and 0.1 EGTA; ~ 290 mOsm, pH 7.22. Electrophysiological recordings were collected with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices) and a custom data acquisition program in the Igor Pro software (Wavemetrics). mEPSCs and mIPSCs were acquired in voltage-clamp configuration at − 80 mV and 0 mV, respectively, and corrected for a 12-mV junction potential. mEPSCs and mIPSCs were collected at 10 kHz and filtered at 3 kHz. Pipette capacitance was completely compensated, and series resistance was compensated by 50%. Series resistance was < 18 MΩ for all recordings and data were omitted if input resistance changed by ± 15%. Events were analyzed using a deconvolution-based event detection algorithm within Igor Pro [24]. Detectable events were identified using a noise threshold of 3.5× with a minimum amplitude of 2 pA and a 2-ms inter-event interval. Events were subsequently manually screened to confirm appropriate event detection. Event detection code is available at https://benderlab.ucsf.edu/resources. Data were acquired from both sexes and no sex-dependent differences were found. All data were analyzed blind to genotype. Statistical analyses were conducted using the GraphPad Prism 8.4 software. Data are shown as min. to max. box and whisker plots. Each data point (n) is indicative of individual neurons. The mean values per cell were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Cumulative probability distribution of mEPSCs and mIPSCs event intervals were generated per cell and then averaged. Distributions were compared using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. A confidence interval of 95% (P < 0.05) was required for values to be considered statistically significant.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All individual data points are shown as well as mean ± SEM. All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. Statistical significance was accepted at the level p < 0.05. We used Student’s t-test to compare pairs of groups if data were normally distributed (verified using the Lillie test). We examined the changes in synapse numbers from n = 2 animals for each genotype. The number of dendrites analyzed is specified in the figure legends. Miniature recording experiments at P70-110 were conducted from n = 3 different animals for each age and genotype. The specific n for each experiment as well as the post hoc test and the corrected p values can be found in the figure legends.

Results

Excitatory and inhibitory synapses are reduced in adult Tbr1 CKO mutants

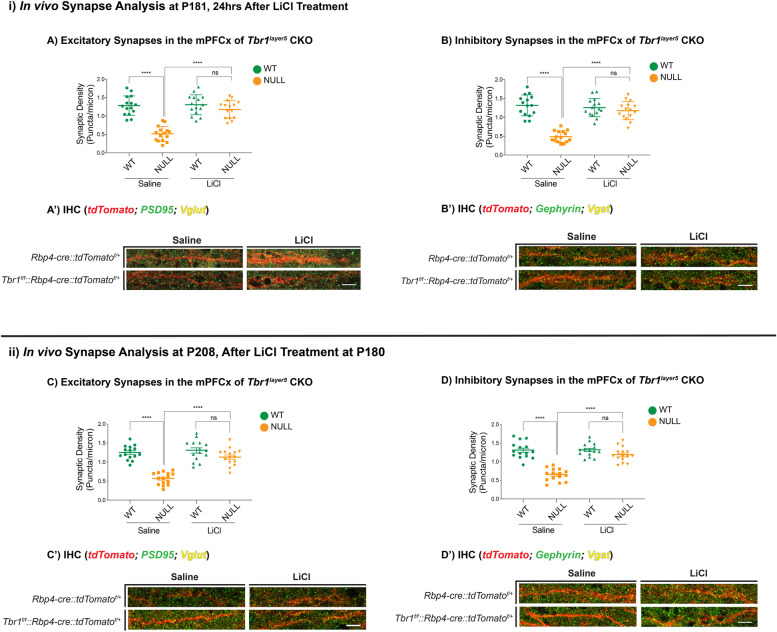

To evaluate whether Tbr1 mouse mutants have a stable synaptic deficit, we examined the number of excitatory and inhibitory synapses onto the apical dendrites of adult Tbr1wildtype, Tbr1layer5CKO, and Tbr1layer6CKO. We compared Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer5CKO neurons within layers 2/3 of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFCx), and Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer6CKO neurons within layer 5 in the somatosensory cortex (SSCx) at P181 and P208. Layer 5 and layer 6 projection neurons were tdTomato+ through labeling with Rbp4-cre::tdTomatof/+ and Ntsr1-cre::tdTomatof/+, respectively. A functional or mature synapse was defined by the overlap of either presynaptic PSD95 and postsynaptic VGLUT1 (excitatory synapse) or presynaptic Gephyrin/ postsynaptic VGAT (inhibitory synapse) onto the endogenous tdTomato+ structures.

We measured the excitatory synaptic density by analyzing VGLUT1+ presynaptic terminals that were apposed to dendritic postsynaptic zones (PSD95+) using immunofluorescence (IF) and confocal microscopy (Fig. 1A, A’). Inhibitory synaptic density was assessed by counting the overlapping VGAT+ presynaptic inhibitory terminals and Gephyrin+ dendritic postsynaptic zones on the apical dendrites (Fig. 1B, B’). Excitatory and inhibitory synapse density was decreased 70% and 73% in Tbr1layer5 CKOs, and 74% and 68% in Tbr1layer6 CKOs at P181 (Figs. 1 and S1) and P208 (Figs. 1 and S1), respectively.

Fig. 1.

LiCl treatment restores normal synapse numbers in Tbr1layer5 mutant mice. Immunofluorescence (IF) was used to detect excitatory (A, C) and inhibitory (B, D) synapses onto dendrites from mPFCx of Tbr1wildtype (Rbp4-cre::tdTomatof/+; green), Tbr1layer5 CKOs (Tbr1f/f::Rbp4-cre::tdTomatof/+; orange) (n = 10 dendrites). Synapses were measured (i) 24 h and (ii) 4 weeks after injection with saline or LiCl at P180. Excitatory synapses were analyzed by VGlut1+ boutons and PSD95+ clusters co-localizing onto the dendrites from layer 5 neurons of mPFCx of Tbr1wildtype (green) and Tbr1layer5CKO (orange) mice 24 h (at P181; A, A’) and 4 weeks (P208; C, C’) after saline and/or LiCl was administered. Mann-Whitney ****p < 0.0001, ns = not significant. Inhibitory synaptic density was measured by VGat+ boutons and Gephyrin+ clusters co-localizing onto dendrites of mPFCx of Tbr1wildtype (green) and Tbr1layer5CKO (orange) 24 h (at P181; B, B’) and 4 weeks (P208; D, D’) after saline and/or LiCl was administered. Mann-Whitney ****p < 0.0001, ns = not significant. The Fiji ImageJ software was used to process confocal images for quantification. Two-tailed T-test with Mann-Whitney’s correction was used for pairwise comparisons

We then examined whether lithium treatment could rescue the synaptic deficit in adult Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKOs (Figs. 1 and S1). The control and LiCl treated brains were harvested either at P181 (24 h after injection), or at P208 (4 weeks after injection; Fig. 1). Confocal images of IF from mPFCx (layer 5) and SSCx (layer 6) showed a nearly complete rescue of synaptic densities, 24 h and 4 weeks after treatment (Figs. 1 and S1). Thus, LiCl treatment of the adult Tbr1layer5, and Tbr1layer6 mutant mice rescued both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic deficit (Figs. 1 and S1).

Furthermore, we investigated the long-term efficacy of lithium treatment on rescuing synaptic deficit in Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKOs. To this end, we treated Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKOs at P30 with a single IP injection as before and examined the changes in synaptic density 6 months post-treatment at P210 (Fig. S2). Lithium treatment resulted in a sustained rescue of the synaptic deficit in Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKOs (Fig. S2), though the percent recovery is lower after a long-term treatment with lithium. Thus, providing in vivo evidence that synaptic deficit phenotype persists into adulthood and that efficacy of the LiCl treatment is sufficient to restore normal synapse numbers in adult Tbr1 CKO mice.

Tbr1 CKO mutants have reduced mature dendritic spine density at P180

The synaptic deficits described above prompted us to investigate the state of dendritic spines from the apical dendrites of Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer5CKO neurons within layers 2/3 in the mPFCx and Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer6CKO neurons within layer 5 in the SSCx at P180. Layer 5 and layer 6 projection neurons were labeled with Rbp4-cre::tdTomatof/+ and Ntsr1-cre::tdTomatof/+, respectively. We captured × 120 magnification Z-stack images (using × 2 optical zoom) using airyscan confocal microscopy from the apical dendrites of Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer5CKO neurons (Fig. 2A–D) and Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer6CKO (Fig. S3A-D) at P180. We used the Imaris software (v9.2.1) to analyze the dendritic spine density and distribution.

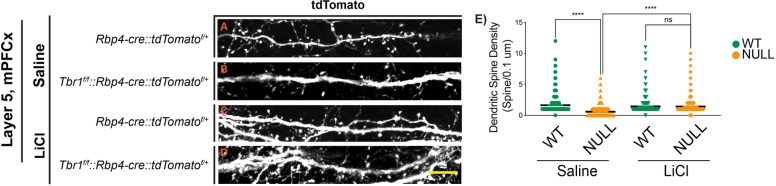

Fig. 2.

LiCl rescues dendritic spine density deficit in mPFCx of Tbr1layer5 CKOs at P180. Rbp4-cre::tdTomatof/+ allele was used to label the dendrites of layer 5 neurons (A–D). The monochrome tdTomato signal (white) is shown from apical dendrites of saline-injected (A, B) and LiCl injected (C, D) Tbr1 CKOs at P181, 24 h after treatment. The Imaris software (v9.2.1) was used to analyze the dendritic spine density on apical dendrites of Tbr1layer5 wildtype and Tbr1layer5CKO neurons located within layers 2-4 of mPFCx (A–D). E Quantification of dendritic spine density on apical dendrites of Tbr1layer5 wildtype (green) and Tbr1layer5CKO neurons (orange) at P181. Spine density was improved 24 h after LiCl treatment (D), compared to the saline-injected control animals (B). Two-tailed T-test with Tukey correction was used for pairwise comparisons. Mann-Whitney ****p < 0.0001 (n = 10 dendrites), ns = not significant. Scale bar = 2 μm

The dendritic spine density was reduced in Tbr1layer5CKO (Fig. 2) and Tbr1layer6CKO (Fig. S3). Thus, the reduction in the mature dendritic spine density may underlie the synaptic density deficit in Tbr1 mutants (Figs. 1, 2, S1 and S3). We then tested whether administering LiCl could rescue the reduction in mature spine density in Tbr1 mutants. We gave a single IP injection of 400 mg/kg LiCl; control animals received a single IP injection of 4 ml/kg saline. LiCl administration rescued the mature dendritic spine density within 24 h in Tbr1 mutants (Fig. 2E, S3E). The LiCl did not have a clear effect on the density of wild-type dendritic spines (Fig. 2E, S3E).

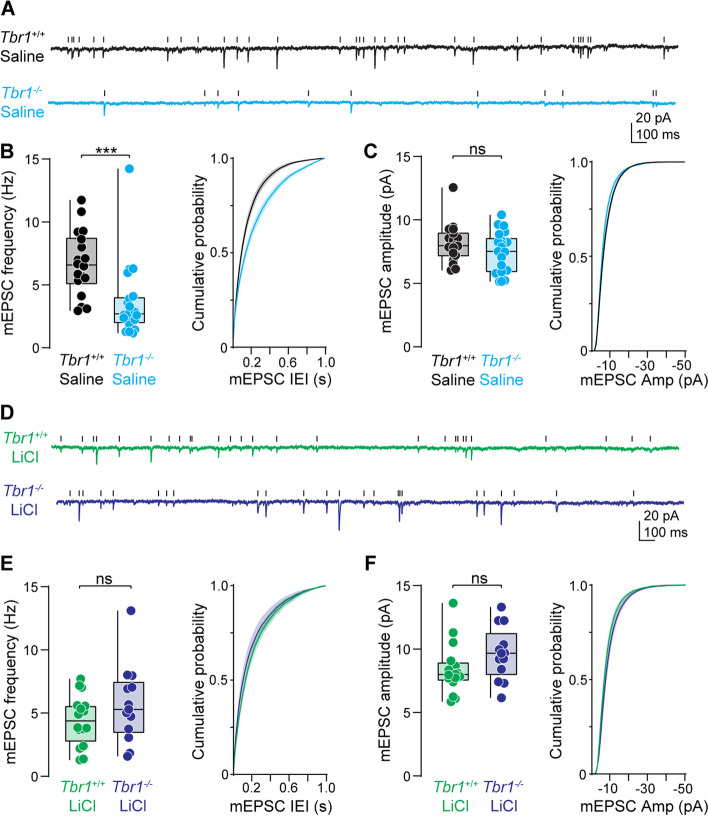

A single dose of LiCl rescues excitatory and inhibitory synapse function in Tbr1 mutant mice

This anatomical reduction in synaptic markers and spine density likely leads to alterations in synapse function. To determine the physiological consequences of Tbr1 loss-of-function on excitatory synapse function in layer 5 thick-tufted pyramidal neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFCx), we performed whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings in acute brain slices of Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer5CKO mice and measured miniature excitatory and inhibitory events. If loss of Tbr1 within layer 5 neurons reduces synapse numbers, without changing synaptic efficacy (e.g., release probability, postsynaptic receptor density at extant synapses), the miniature synaptic frequency would be reduced without any change in the amplitude of the remaining miniature events. Consistent with this prediction, the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) was reduced by ~ 45% in P65-106 Tbr1layer5CKO neurons compared to Tbr1wildtype (Fig. 3A–B), an extent comparable to the observed reduction in anatomical markers of excitatory synapses (Fig. 1). There was no difference in mEPSC amplitude between Tbr1layer5CKO neurons compared to Tbr1wildtype (Fig. 3A, C). This suggests that Tbr1 loss affects both anatomical and functional aspects of excitatory synapses, perhaps without affecting AMPA receptor density at remaining synapses. Whether postsynaptic Tbr1 loss affects presynaptic release probability remains unclear.

Fig. 3.

A single LiCl treatment restores excitatory synapse function in Tbr1layer5 CKOs. A Representative traces of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) from saline treated (4 ml/kg) P65-106 Tbr1wildtype (black) and Tbr1layer5CKO (cyan) layer 5 thick-tufted pyramidal neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFCx). Scale bars: 20 pA, 100 ms. B Left: quantification of mEPSC frequency. Mann-Whitney ***p = 0.0001 (Tbr1wildtype+saline: 6.71 ± 0.6 Hz, n = 18, Tbr1layer5CKO+saline 3.627 ± 0.7 Hz, n = 20). Right: cumulative probability distribution of mEPSC inter-event intervals. Kolmogorov-Smirnov **p = 0.002. C Left: quantification of mEPSC amplitude. Mann-Whitney p = 0.32 (Tbr1wildtype: 6.03 ± 0.4 pA, n = 18, Tbr1layer5CKO 5.15 ± 0.4 pA, n = 20). Right: cumulative probability distribution of mEPSC amplitude. Kolmogorov-Smirnov p = 1.0. D Representative traces of mEPSCs from layer 5 neurons of P95-104 Tbr1wildtype (green) and Tbr1layer5CKO (purple) treated with 400 mg/kg LiCl at P30. Scale bars: 20 pA, 100 ms. E Left: quantification of mEPSC frequency. Mann-Whitney p = 0.31 (Tbr1wildtype+ LiCl: 4.43 ± 0.5 Hz, n = 16, Tbr1layer5CKO+ LiCl: 5.69 ± 0.9 Hz, n = 13). Right: cumulative probability distribution of mEPSC inter-event intervals. Kolmogorov-Smirnov p > 0.99. F Left: quantification of mEPSC amplitude. Mann-Whitney p = 0.09 (Tbr1wildtype+ LiCl: 8.41 ± 0.5 pA, n = 16, Tbr1layer5CKO+ LiCl 9.63 ± 0.6 pA, n = 13). Right: cumulative probability distribution of mEPSC inter-event intervals. Kolmogorov-Smirnov p > 0.99. Boxplots are min to max show all points

Tbr1 is also highly expressed in layer 6 pyramidal neurons within the somatosensory cortex (SSCx) [11, 14]. Therefore, we next investigated the functional implications of Tbr1 knockout in SSCx layer 6 neurons of adult mice. Recordings of mEPSCs in P70-P110 mice revealed ~ 60% reduction in mEPSC frequency in Tbr1layer6CKO mice versus Tbr1wildtype (Fig. S4A-B). In contrast to experiments in layer 5, mEPSC amplitude was reduced in layer 6 (Fig. S4A and C), suggesting that Tbr1 plays an additional role in regulating either postsynaptic AMPA receptor density or, on average, shifts the location of remaining excitatory synapses to positions more distal to the soma. Despite these differences, the magnitude of reduction in mEPSC frequency is similar between deep-layer pyramidal neurons within the mPFCx and SSCx. Overall, these data indicate that Tbr1 is critical for normal glutamatergic transmission within these cell types.

Previously, we showed that a single, 400 mg/kg dose of LiCl restored excitatory synapse density on layer 5 pyramidal neurons in Tbr1layer5CKO mice within 24 h, an effect that is maintained up to 4 weeks post-treatment [15]. Here, we found the morphological components of excitatory synapses were rescued in Tbr1layer5CKO and Tbr1layer6CKO mice up to 6 months after one administration of LiCl. But whether a single IP injection of LiCl in Tbr1 knockout mice restores excitatory synapse function for the long term was unknown. To test this, we first administered LiCl (400 mg/kg) in Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer5CKO mice at P30 and recorded mEPSCs in acute brain slices at P95-104. Following LiCl treatment, there was no difference in mEPSC frequency or amplitude in Tbr1layer5CKO mice compared to Tbr1wildtype littermates up to 8–10 weeks (Fig. 3D–F). We next measured excitatory synapse function in layer 6 SSCx neurons of Tbr1layer6CKO versus Tbr1wildtype 8 weeks after LiCl treatment. Neither mEPSC frequency nor amplitude was different in Tbr1wildtype and Tbr1layer6CKO layer 6 SSCx pyramidal neurons from P65-95 LiCl treated mice (Fig. S4D-F). Taken together, these data demonstrate that a single dose of LiCl rescues excitatory synapse function in layer 5 and layer 6 pyramidal neurons in the mPFCx and SSCx up to 8 weeks post-treatment.

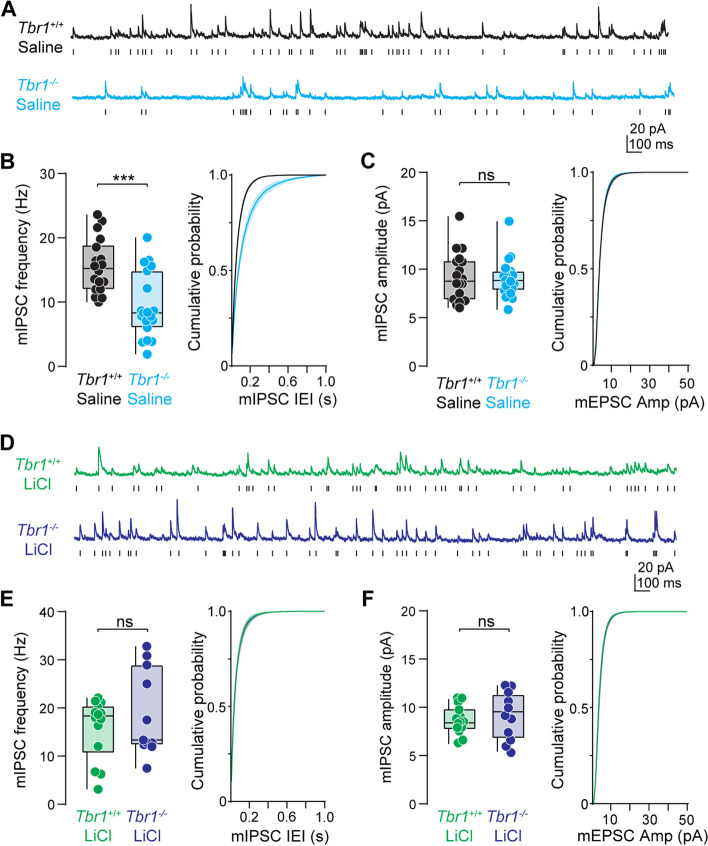

Tbr1 also plays an essential role in inhibitory synapse development, maintenance, and function [16]. We found that Tbr1layer5CKO and Tbr1layer6CKO mice have a lower inhibitory synaptic density at P180 compared to Tbr1wildtype littermates. Thus, we predicted that fewer inhibitory synapses onto layer 5 and layer 6 pyramidal neurons in Tbr1 knockout mice would result in reduced frequency of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSC). To test this, we recorded mIPSCs from layer 5 thick-tufted pyramidal neurons in Tbr1layer5CKO mice and Tbr1wildtype controls. mIPSC frequency was significantly reduced in Tbr1layer5CKO neurons compared to Tbr1wildtype with no difference in mIPSC amplitude (Fig. 4A–C).

Fig. 4.

LiCl rescues inhibitory synapse deficits in mPFCx of Tbr1layer5 CKOs. A Representative traces of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) from layer 5 mPFCx neurons of P65-106 Tbr1wildtype (black) and Tbr1layer5CKO (cyan) mice following saline administration (4 ml/kg) at P30. Scale bars: 20 pA, 100 ms. B Left: quantification of mIPSC frequency. Mann-Whitney ***p = 0.0005 (Tbr1wildtype+saline: 15.6 ± 1.0 Hz, n = 18, Tbr1layer5CKO+saline 9.4 ± 1.2 Hz, n = 19). Right: cumulative probability distribution of mIPSC inter-event intervals. Kolmogorov-Smirnov ****p < 0.0001. C Left: quantification of mIPSC amplitude. Mann-Whitney p = 0.32 (Tbr1wildtype+saline: 9.24 ± 0.6 pA, n = 18, Tbr1layer5CKO+saline: 9.08 ± 0.5 pA, n = 19). Right: cumulative probability distribution of mIPSC amplitude. Kolmogorov-Smirnov *p = 0.04. D Representative traces of mIPSCs from layer 5 neurons of LiCl (400 mg/kg) treated P95-104 Tbr1wildtype (green) and Tbr1layer5CKO (purple) mice. Scale bars: 20 pA, 100 ms. E Left: quantification of mIPSC frequency. Mann-Whitney p = 0.77 (Tbr1wildtype+ LiCl: 15.84 ± 1.7 Hz, n = 14, Tbr1layer5CKO+ LiCl: 18.73 ± 2.7 Hz, n = 11). Right: cumulative probability distribution of mIPSC inter-event intervals. Kolmogorov-Smirnov p = 0.47. F Left: quantification of mIPSC amplitude. Mann-Whitney p = 0.57 (Tbr1wildtype+ LiCl: 8.6 ± 0.4 pA, n = 14, Tbr1layer5CKO+ LiCl 9.1 ± 0.8 pA, n = 11). Right: cumulative probability distribution of mIPSC inter-event intervals. Kolmogorov-Smirnov p = 0.86. Boxplots are min to max show all points

Next, we recorded mIPSCs from layer 6 pyramidal neurons in the SSCx from Tbr1layer6CKO mice and Tbr1wildtype littermates. We found similar trends in both the frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs in Tbr1layer6CKO neurons within the SSCx as observed in Tbr1layer5CKO neurons within the mPFCx; however, these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. S5A-C). We next wanted to evaluate the long-term efficacy of LiCl treatment on rescuing inhibitory synaptic deficits in Tbr1layer5CKO and Tbr1layer6CKO mice. A single dose of LiCl (400 mg/kg) administered at P30 restored the mIPSC frequency deficits in Tbr1layer5CKO pyramidal neurons in P95-104 mice. LiCl treatment of Tbr1layer6CKO mice resulted in no difference in mIPSC frequency or amplitude compared to Tbr1wildtype treated animals (Fig. S5D-F). Thus, a single 400 mg/kg dose of LiCl results in long-term restoration of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission deficits following the loss of Tbr1 in layer 5 pyramidal neurons of the mPFCx and restores excitatory synaptic deficits in layer 6 pyramidal neurons within the SSCx.

Discussion and conclusions

Tbr1 promotes synaptic numbers and function in adult mouse mPFCx

Tbr1 is expressed in telencephalic post-mitotic excitatory neurons; its expression is well described in the mouse where it is detected in the neocortex, hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, pallial amygdala, piriform cortex, olfactory bulb, subplate, and Cajal-Retzius neurons [10, 11]. Tbr1 is best known for its expression and function in layer 6, where it is required to initiate and then maintain layer 6 identity by repressing markers of layer 5 identity [12, 16]. Previously, we demonstrated that Tbr1 promotes dendritic spine maturation and synaptogenesis in the excitatory neurons of mouse cortical layers 5 and 6 during neonatal and adolescent developmental stages [15, 16]; a phenotype that potentially links Tbr1’s function to neuropsychiatric disorders such as ASD. Furthermore, we interrogated these phenotypes in mouse mPFCx, a cortical region with critical functions in cognitive and affective processing.

Towards evaluating whether the LiCl rescue could be relevant for treatment of human TBR1 mutant patients, we examined whether Tbr1 is required to maintain dendritic spine maturation and synaptogenesis in adulthood (P180 and P208). We discovered that the adult Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKO mutants have reduced dendritic spine and synaptic densities. Furthermore, adult Tbr1 CKO mutants have reduced synaptic transmission as demonstrated by the reduction in the frequency of mEPSCs and mIPSCs. Thus, Tbr1 is required for the long-term synaptic development, maintenance, and function of the excitatory neurons of cortical layers 5 and 6.

LiCl rescues dendritic spine maturation and synaptic transmission in Tbr1 mutants

WNT signaling is well-known to control synapse development [25, 26]. WNT signaling is essential in postsynaptic differentiation of excitatory synapses by recruiting NMDA receptors via promoting PSD95 clustering and local activation of CaMKII within dendritic spines [27]. Furthermore, the Wnt7b activation of the canonical WNT pathway has been linked to increased presynaptic inputs in the developing hippocampus [25, 28, 29]. Previously, we showed that LiCl, an FDA-approved drug with multiple effects including acting as a WNT signaling agonist, rescued defects in dendritic spine maturation and reduced synapse numbers in the adolescent Tbr1 mutants [15, 16]. Here, we examined the efficacy and long-term potency of LiCl treatment in rescuing the dendritic spine and synaptic defects in the adult Tbr1 mutants. We used two different approaches: (1) administering a single IP LiCl injection at 6 months (P180) and examining the effect 4 weeks post-injection and (2) administering a single IP LiCl injection at P30 and examining the effect 6 months post-injection.

LiCl rapidly (within 24 h) promoted the maturation of dendritic spines in Tbr1layer5 and Tbr1layer6 CKO neurons in cortical layers 5 and 6, respectively. Furthermore, LiCl rescued excitatory and inhibitory synapse numbers within 24 h. Remarkably, a single dose of LiCl at P30 led to a sustained rescue of synaptic density, measured 6 months after treatment. Furthermore, LiCl treatment rescued the reduction in the mEPSCs and mIPSCs. Thus, LiCl treatment led to a long-term restoration of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission deficits following the loss of Tbr1 in layer 5 and 6 pyramidal neurons.

LiCl as a potential therapy for neurodevelopmental disorders with reduced synapse transmission

ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder and patients typically display symptoms before the age of three [30]. One of the key questions in autism research is whether the pathology is reversible, and if so, at what ages can it be ameliorated. Currently, there are no treatments for ASD that address its core biological defects; we suggest that reduced synapse numbers may be one of these core defects in at least a subset of patients, such as those who have a function altering TBR1 mutation. In addition to TBR1, mutations in SHANK3 (another high confidence ASD-risk gene) have been shown to result in synaptic defects and autistic-like behaviors including anxiety, social interaction deficits, and repetitive behavior [31–33]. Thus, it has been postulated that synapse numbers (connectivity) and synaptic function are points of convergence in ASD pathophysiology [34].

The ability to restore synapse numbers and transmission following LiCl administration in the adult Tbr1 mutant mice provides an insight to a possible human therapy, especially given that LiCl is an FDA-approved drug with well-described side effects [35]. Even though our current work suggests the applicability of LiCl for ASD patients with TBR1 mutations, LiCl could be considered for other ASD syndromes. This hypothesis is further strengthened by a clinical case report where two ASD patients (a 21-year-old male and a 17-year-old female) with mutations in SHANK3 underwent lithium treatment. Lithium treatment in these two patients improved the clinical regression, stabilized behavioral abnormalities, and restored brain function to their pre-catatonia levels without reported adverse side effects [36].

Remarkable properties of LiCl in treating mouse Tbr1 mutants are (1) its ability to rapidly (24 h) promote dendritic spine maturation and synaptogenesis and (2) the 6-month persistence of its action after only a single LiCl single dose. We suggest that the Tbr1 mutants may have immature synapses that are poised to mature once they receive the appropriate signal (perhaps a WNT agonist) [15] and once achieved, the synapses are maintained and function at a reasonable level. Thus, LiCl may have some promise as a therapy for ASD patients with either mutations in TBR1 or for cases due to other genetic or non-genetic etiologies that have a similar block in synaptic development.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the UCSF-LARC animal facility for their help with the mouse colony maintenance.

Abbreviations

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- mEPSC

Miniature excitatory post-synaptic current

- mIPSC

Miniature inhibitory post-synaptic current

- CKO

Conditional nock-out

- mPFCx

Medial prefrontal cortex

- SSCx

Somatosensory cortex

- IP

Intraperitoneal injection

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: S.F.D., A.D.N., K.J.B., and J.L.R. Methodology: S.F.D., A.D.N., K.J.B., and J.L.R. Investigation: S.F.D. and A.D.N. Writing—original draft: S.F.D., A.D.N., and J.L.R. Writing—review and editing. S.F.D., A.D.N., K.J.B., and J.L.R. Funding acquisition: J.L.R. and K.J.B. Supervision: K.J.B. and J.L.R. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the research grants to J.L.R.R. from Nina Ireland, NINDS R01 NS34661, and R01 NS099099, and the Simons Foundation 630332 and grants to K.J.B. NIH R01 MH125978 and A.D.N. NIH F32 MH125536.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials that were used in this study are available upon request from the lead contact.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures and animal care were approved and performed in accordance with the University of California San Francisco Laboratory Animal Research Center (LARC) guidelines.

Consent for publication

All contributing authors have read and agreed to submit this manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

J.L.R.R. is the cofounder, stockholder, and currently on the scientific board of Neurona, a company studying the potential therapeutic use of interneuron transplantation. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Siavash Fazel Darbandi, Email: siavashfd86@gmail.com.

Andrew D. Nelson, Email: Andrew.Nelson2@ucsf.edu

Emily Ling-lin Pai, Email: emilypai1125@gmail.com.

Kevin J. Bender, Email: Kevin.Bender@ucsf.edu

John L. R. Rubenstein, Email: john.rubenstein@ucsf.edu

References

- 1.Sanders SJ, He X, Willsey AJ, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Samocha Kaitlin E, Cicek AE, et al. Insights into autism spectrum disorder genomic architecture and biology from 71 risk loci. Neuron. 2015;87(6):1215–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willsey AJ, Sanders Stephan J, Li M, Dong S, Tebbenkamp Andrew T, Muhle Rebecca A, et al. Coexpression networks implicate human midfetal deep cortical projection neurons in the pathogenesis of autism. Cell. 2013;155(5):997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satterstrom FK, Kosmicki JA, Wang J, Breen MS, De Rubeis S, An J-Y, et al. Large-scale exome sequencing study implicates both developmental and functional changes in the neurobiology of autism. Cell. 2020;180(3):568–84.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, Poultney CS, Samocha K, Ercument Cicek A, et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515(7526):209–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iossifov I, O’Roak BJ, Sanders SJ, Ronemus M, Krumm N, Levy D, et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515(7526):216–221. doi: 10.1038/nature13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders SJ, Murtha MT, Gupta AR, Murdoch JD, Raubeson MJ, Willsey AJ, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485(7397):237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deriziotis P, O’Roak BJ, Graham SA, Estruch SB, Dimitropoulou D, Bernier RA, et al. De novo TBR1 mutations in sporadic autism disrupt protein functions. Nat Commun. 2014;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Wang T-F, Ding C-N, Wang G-S, Luo S-C, Lin Y-L, Ruan Y, et al. Identification of Tbr-1/CASK complex target genes in neurons. J Neurochemistry. 2004;91(6):1483–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang T-N, Hsueh Y-P. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase (CASK), a protein implicated in mental retardation and autism-spectrum disorders, interacts with T-Brain-1 (TBR1) to control extinction of associative memory in male mice. J Psychiatr Neuroscience: JPN. 2017;42(1):37–47. doi: 10.1503/jpn.150359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hevner RF, Neogi T, Englund C, Daza RAM, Fink A. Cajal–Retzius cells in the mouse: transcription factors, neurotransmitters, and birthdays suggest a pallial origin. Developmental Brain Res. 2003;141(1):39–53. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(02)00641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hevner RF, Shi L, Justice N, Hsueh Y-P, Sheng M, Smiga S, et al. Tbr1 Regulates differentiation of the preplate and layer 6. Neuron. 2001;29(2):353–366. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenna WL, Betancourt J, Larkin KA, Abrams B, Guo C, Rubenstein JLR, et al. Tbr1 and Fezf2 egulate alternate corticofugal neuronal identities during neocortical development. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):549–564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4131-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulfone A, Wang F, Hevner R, Anderson S, Cutforth T, Chen S, et al. An olfactory sensory map develops in the absence of normal projection neurons or GABAergic interneurons. Neuron. 1998;21(6):1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedogni F, Hodge RD, Elsen GE, Nelson BR, Daza RAM, Beyer RP, et al. Tbr1 regulates regional and laminar identity of postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2010;107(29):13129–13134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002285107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazel Darbandi S, Robinson Schwartz SE, Pai EL-L, Everitt A, Turner ML, Cheyette BNR, et al. Enhancing WNT signaling restores cortical neuronal spine maturation and synaptogenesis in Tbr1 mutants. Cell Reports. 2020;31(2):107495. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fazel Darbandi S, Robinson Schwartz SE, Qi Q, Catta-Preta R, Pai EL-L, Mandell JD, et al. Neonatal <em>Tbr1</em> dosage controls cortical layer 6 connectivity. Neuron. 2018;100(4):831–45.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenox RH, Wang L. Molecular basis of lithium action: integration of lithium-responsive signaling and gene expression networks. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8(2):135–144. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin PM, Stanley RE, Ross AP, Freitas AE, Moyer CE, Brumback AC, et al. DIXDC1 contributes to psychiatric susceptibility by regulating dendritic spine and glutamatergic synapse density via GSK3 and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(2):467–475. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farooq M, Kim S, Patel S, Khatri L, Hikima T, Rice ME, et al. Lithium increases synaptic GluA2 in hippocampal neurons by elevating the delta-catenin protein. Neuropharmacology. 2017;113(Pt A):426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong S, Doughty M, Harbaugh CR, Cummins A, Hatten ME, Heintz N, et al. Targeting Cre recombinase to specific neuron populations with bacterial artificial chromosome constructs. J Neuroscience. 2007;27(37):9817. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2707-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nature Neurosci. 2010;13(1):133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pernía-Andrade AJaG, Sarit Pati and Stickler, Yvonne and Fröbe, Ulrich and Schlögl, Alois and Jonas, Peter. A deconvolution-based method with high sensitivity and temporal resolution for detection of spontaneous synaptic currents in vitro and in vivo. Biophys J. 2012;103(7):1429–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis EK, Zou Y, Ghosh A. Wnts acting through canonical and noncanonical signaling pathways exert opposite effects on hippocampal synapse formation. Neural Development. 2008;3:32-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Liebl FLW, McKeown C, Yao Y, Hing HK. Mutations in Wnt2 alter presynaptic motor neuron morphology and presynaptic protein localization at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e12778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciani L, Boyle KA, Dickins E, Sahores M, Anane D, Lopes DM, et al. Wnt7a signaling promotes dendritic spine growth and synaptic strength through Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Proc Nat Acad Sciences United States of America. 2011;108(26):10732–10737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018132108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Budnik V, Salinas PC. Wnt signaling during synaptic development and plasticity. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2011;21(1):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salinas PC, Zou Y. Wnt signaling in neural circuit assembly. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2008;31(1):339–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC; 2013.

- 31.Peça J, Feliciano C, Ting JT, Wang W, Wells MF, Venkatraman TN, et al. Shank3 mutant mice display autistic-like behaviours and striatal dysfunction. Nature. 2011;472(7344):437–442. doi: 10.1038/nature09965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, McCoy PA, Rodriguiz RM, Pan Y, Je HS, Roberts AC, et al. Synaptic dysfunction and abnormal behaviors in mice lacking major isoforms of Shank3. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(15):3093–3108. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bozdagi O, Sakurai T, Papapetrou D, Wang X, Dickstein DL, Takahashi N, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the autism-associated Shank3 gene leads to deficits in synaptic function, social interaction, and social communication. Molecular autism. 2010;1(1):15-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Sestan N, State MW. Lost in translation: traversing the complex path from genomics to therapeutics in autism spectrum disorder. Neuron. 2018;100(2):406–423. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curran G, Ravindran A. Lithium for bipolar disorder: a review of the recent literature. Expert Rev Neurother. 2014;14(9):1079–1098. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2014.947965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serret S, Thümmler S, Dor E, Vesperini S, Santos A, Askenazy F. Lithium as a rescue therapy for regression and catatonia features in two SHANK3 patients with autism spectrum disorder: case reports. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0490-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials that were used in this study are available upon request from the lead contact.