Abstract

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) acts as a cofactor in several oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions and is a substrate for a number of nonredox enzymes. NAD is fundamental to a variety of cellular processes including energy metabolism, cell signaling, and epigenetics. NAD homeostasis appears to be of paramount importance to health span and longevity, and its dysregulation is associated with multiple diseases. NAD metabolism is dynamic and maintained by synthesis and degradation. The enzyme CD38, one of the main NAD-consuming enzymes, is a key component of NAD homeostasis. The majority of CD38 is localized in the plasma membrane with its catalytic domain facing the extracellular environment, likely for the purpose of controlling systemic levels of NAD. Several cell types express CD38, but its expression predominates on endothelial cells and immune cells capable of infiltrating organs and tissues. Here we review potential roles of CD38 in health and disease and postulate ways in which CD38 dysregulation causes changes in NAD homeostasis and contributes to the pathophysiology of multiple conditions. Indeed, in animal models the development of infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders, fibrosis, metabolic diseases, and age-associated diseases including cancer, heart disease, and neurodegeneration are associated with altered CD38 enzymatic activity. Many of these conditions are modified in CD38-deficient mice or by blocking CD38 NADase activity. In diseases in which CD38 appears to play a role, CD38-dependent NAD decline is often a common denominator of pathophysiology. Thus, understanding dysregulation of NAD homeostasis by CD38 may open new avenues for the treatment of human diseases.

Keywords: CD38, diseases, NAD metabolism

INTRODUCTION

A series of studies by Warburg and others between the 1920s and the 1950s led to the discovery that nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is an essential cofactor in oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions (1). These discoveries shed light on reactions that drive the transfer of reducing equivalents from energy-rich substrates such as glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids to the mitochondrial electron transport system (ETS), resulting in the synthesis of ATP (2). The NAD+-to-NADH ratio (NAD+/NADH) is considered a readout of the cell’s redox state (3). The phosphorylated form of NADH (NADPH) is also a critical substrate for enzymes charged with scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and preventing oxidative damage to cells (4, 5).

In addition to these “classical” functions, NAD plays a crucial role in cell signaling as a substrate for protein-modifying enzymes (e.g., ADP-ribosylation and deacetylation) and the formation of putative second messengers such as cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) and nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) (6). This review critically discusses the mounting literature demonstrating that NAD dysregulation is consequential to cellular homeostasis. In fact, dysregulation of NAD metabolism is currently reported in preclinical animal models of age-related disease and increasingly identified in human diseases (7). NAD homeostasis relies on several enzymes including those associated with NAD degrading and synthetic pathways. This review pays particular attention to the role of the NAD-catabolizing enzyme CD38, which plays critical roles in the pathogenesis of diseases related to infection, inflammation, fibrosis, metabolism, and aging (Fig. 1) (7–9).

Figure 1.

Diseases associated with CD38 and/or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) dysfunction. Asterisks indicate diseases in which CD38 and NAD metabolism play a role in pathophysiology but the link between CD38 and NAD dysregulation in these diseases is yet to be established. GI, gastrointestinal.

NAD METABOLISM OVERVIEW: SYNTHESIS AND DEGRADATION

Cellular NAD levels are dynamically controlled by the balance between its synthesis and degradation (6). As a redox carrier, NAD is interconverted between its oxidized form (NAD+) and its reduced form (NADH) by dehydrogenases or oxidoreductases that catalyze hydride transfer. In redox reactions, the ratio between the oxidized and reduced forms (NAD+/NADH) is changed but no NAD is consumed and the total NAD+/NADH pool is maintained. However, NAD-degrading enzymes such as CD38, ARTCs (ADP-ribosyltransferase C2 and C3 toxin-like), sirtuins (SIRTs), and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) break the glycosidic bond between the nicotinamide ring and the ribose of the dinucleotide. This generates free nicotinamide and an ADP-ribosyl moiety and contributes to a decrease in the levels of NAD (6). The activity of these enzymes is reflected by high turnover of NAD in some tissues (10). NAD half-life varies across tissues from 15 min to 15 h in mice, averaging 2–4 h in most tissues (10). The dynamic turnover of NAD in tissues highlights the previously underappreciated metabolic fluxes of NAD in vivo. Why NAD turnover is especially rapid is not entirely understood (11). The total NAD pool is recycled in hours and requires a significant expenditure of energy to maintain cellular levels (Table 1). Conservative estimates predict that the mouse recycles its NAD pool nearly three times a day to maintain its steady-state level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Energy cost of NAD salvage pathway synthesis

| Tissue | NAD, nmol/mg* | Tissue Weight, g | NAD, µmol | NAD Half-Life, h | NAD Turnover, µmol/h | ATP |

% Daily Caloric Requirements | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µmol/h | µmol in 24 h | kcal in 24 h | |||||||

| Liver | 4.77 | 1.4 | 6.9 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 9.8 | 235.7 | 0.0017 | 0.021 |

| Heart | 4.12 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 22.8 | 0.0002 | 0.002 |

| Spleen | 0.38 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 5.5 | 0.0000 | 0.000 |

| Intestine | 0.84 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 7.8 | 187.6 | 0.0014 | 0.016 |

| Skeletal muscle | 2.26 | 19.7 | 44.5 | 14.6 | 1.5 | 9.1 | 219.6 | 0.0016 | 0.019 |

| Fat | 4.34 | 3.6 | 15.6 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 20.4 | 488.6 | 0.0036 | 0.043 |

| Brain | 2.36 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 3.9 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 18.3 | 0.0001 | 0.002 |

| Lung | 1.75 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 8.2 | 0.0001 | 0.001 |

| Kidneys | 7.78 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 72.8 | 0.0005 | 0.006 |

| Total | 26.9 | 72.5 | 8.74 | 52.5 | 1,259.0 | 0.0092 | 0.110 | ||

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) levels are derived from 3-mo-old C57BL/6 male mice (n = 4). Tissue weights are provided by the Jackson Laboratory database. NAD half-life in tissues is determined according to Liu et al. (10). Daily caloric requirement of young C57BL/6 male mice is 8.33 kcal/day based on the Jackson Laboratory database. *Calculations are based on an expenditure of 6 ATP molecules per recycled nicotinamide (NAM) [i.e., 2 ATP equivalents in the ribose-5-phosphate isomerase reaction, 2 ATP in the reaction catalyzed by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), and 2 ATP equivalents in the reaction catalyzed by nicotinamide/nicotinic acid mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT)].

NAD can be synthesized by multiple pathways (Fig. 2). De novo NAD synthesis requires the essential amino acid tryptophan and proceeds through the kynurenine pathway (KP) mainly in the liver (10, 12). A portion of de novo-synthesized NAD is likely metabolized in the liver to nicotinamide (NAM) and then distributed organism-wide. It is speculated that NAM released from the liver or NAM formed as a product of NAD breakdown in cells is used to generate NAD in other tissues through a second pathway called the NAD salvage pathway (10). The first step of the salvage pathway is catalyzed by the rate-limiting enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which synthesizes nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) from NAM and a phospho-ribosyl group from 5-phospho-α-d-ribosyl 1-diphosphate (PRPP), a metabolite that originates from the pentose-phosphate pathway (13). NMN is a substrate for NMN-adenylyltransferases (NMNATs 1–3), which catalyze the conversion of NMN and ATP to NAD and pyrophosphate. Interestingly, the synthesis of NAD from NAM is energetically costly (Table 1), particularly given the requirement of 2–4 molecules of ATP per molecule of NMN (14, 15). Based on 24-h NAD turnover, one would expect a mouse to use ∼1.25 mmol of ATP each day to recycle its NAD pool via the salvage pathway (Table 1). This amount would correspond to ∼0.7 g of ATP per day, ∼1–3% of the weight of a young mouse, to maintain steady-state levels of NAD. Although NAD turnover has not been determined in humans, data in rodents suggest that the energy requirement for recycling this cofactor is quite significant.

Figure 2.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) pathways: synthesis, degradation, and excretion. Overview of the pathways related to NAD metabolism. 2PY, N-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide; 4PY, N-methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide; ACMS, 2-amino-3-carboxymuconic acid semialdehyde; ADPR, ADP-ribose; AFMID, arylformamidase; AOX, aldehyde oxidase; Cyp2E1, cytochrome P-450 2E1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HAAO, 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; KMO, kynurenine 3-monooxygenase; KYNU, kynureninase; M-NAM, methyl nicotinamide; NA, nicotinic acid; NaAD, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NAM, nicotinamide; NaMN, nicotinic acid mononucleotide; NAMPT, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; NaPRT1, nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase 1; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NMNAT1, nicotinamide/nicotinic acid mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 1; NNMT, nicotinamide N-methyltransferase; NR, nicotinamide riboside; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate; QPRT, quinolinate phosphoribosyl transferase; SARM1, sterile α and TIR motif-containing protein 1; TPO, tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Figure modified from Chini et al. (319) with permission from Cell Metabolism.

NAD is alternatively generated from nicotinic acid (NA), a dietary form of vitamin B3, through a third pathway called the Preiss–Handler pathway. Here the enzyme nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (NAPRT1) catalyzes the reaction between NA and PRPP using energy derived from ATP and produces nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN), ADP, and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) (16, 17). The next steps involve the incorporation of AMP (from ATP) by NMNATs and an amidation in the pyridine ring of NA by the NAD-synthetase, which uses l-glutamine or ammonia as a nitrogen source (18) to generate NAD. Interestingly, changes in the intestinal microbiota can affect NAD production via the Preiss–Handler pathway (19). In the gut, metabolism of NA by the intestinal microbial nicotinamidase PncA generates NAM (19). As expected, germfree mice are more vulnerable to the inhibition of the salvage pathway, indicating that gut microbiota indeed contribute to NAD production through the Preiss–Handler pathway. Furthermore, gut microbiota potentiates the NAD-boosting effect of NAM supplementation by providing deaminated intermediates for NAD synthesis. Gut microbiota also participates in conversion of NR to NAM, NA, and nicotinic acid riboside (NAR) in mice (19). Taken together, gut microbiota contributes to the energy balance of the organism by maintaining NAD levels within a healthy range mainly by diversifying the array of NAD precursors for NAD synthesis available to the host.

NMN, another NAD precursor, can be generated intracellularly from NR via a phosphorylation reaction catalyzed by nicotinamide riboside kinase 1 (NRK1) (20–22). A reduced form of NR (NRH) can also serve as a potent NAD precursor (23, 24). NRH is phosphorylated to NMNH by adenosine kinase and results in enhanced NAD boosting (23–25). The interplay between these multiple pathways for NAD synthesis has not been completely elucidated.

NAD CONSUMERS: PARPs, SIRTs, SARMs

The common feature of enzymes that degrade NAD is that each breaks the glycosidic bond between the NAM ring and the ribose of the dinucleotide. This section highlights ADP-ribosyltransferases (PARPs), NAD-dependent protein deacylases (SIRTs), and the sterile α and toll/IL-1 receptor motif containing 1 enzyme (SARM1).

ADP-Ribose Polymerases

ADP-ribosyltransferases such as PARPs [poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases] and tankyrases catalyze the transfer of ADP-ribose from NAD to a number of amino acids in substrate proteins (i.e., arginine, aspartate, glutamate, cysteine, serine, lysine, or tyrosine residues) and release NAM (26, 27). This posttranslational modification can then be recognized by other proteins that possess specific interaction domains such as PIN, PEPPAR, PBZ, BRCT, MDPAR, WWE, OB-fold, and/or FHA. A well-known example of poly ADP-ribosylation (PAR) is the PARylation of proteins by ribosyltransferases that sense single- or double-strand DNA breaks (26). The resulting PAR chains recruit DNA repair machinery. ADP-ribosylation additionally controls many other important cellular processes such as transcription (28, 29), cell cycle progression (30), proteasome regulation (31), and metabolism (32). Among the ADP-ribosyltransferases, PARP1 is the most abundant and significantly impacts NAD levels when overactivated (33–36). Another example of ADP-ribosylation is the recently described ADP-ribosylation of DNA on thymidine, which is performed by DNA ADP-ribosyltransferase (DarT) and is induced by bacterial toxins (e.g., DarT-DarG-toxin antitoxin system) requiring NAD consumption (37).

NAD-Dependent Protein Deacetylases

Largely known as NAD-dependent protein deacetylases, sirtuins (SIRTs) transfer the acetyl group of an acetylated substrate protein to the ADPR moiety of NAD, forming 2′-O-acetyl-ADPR, NAM, and deacetylated proteins (38). Some sirtuins such as SIRT4–7 display lower deacetylase activity (39–42). Apart from protein deacetylation activity, sirtuins also perform other reactions such as defatty-acylation by SIRT1–3 and -6 (43–46), deacylation by SIRT4 (47), and desuccinylation, demalonylation, and deglutarylation by SIRT5 (48–50) in an NAD-dependent manner. NAD levels regulate these activities as well as biological processes related to these enzymes (51, 52). Having low binding affinity to NAD+ (27), sirtuins are more likely to be influenced by changes in NAD homeostasis as a consequence of the activity of other NAD-dependent enzymes.

Sterile α and Toll/IL-1 Receptor Motif-Containing 1

Sterile α and Toll/interleukin-1 receptor motif-containing 1 (SARM1) has been identified in neurons as a new member of the NADase enzyme family (53, 54). It was shown to degrade NAD and generate ADPR, cADPR, and NAM as products (53). SARM1 may also generate the second messenger NAADP via the base-exchange reaction (55). In neurons, SARM1-dependent NAD depletion plays a key role in the axonal degeneration pathway in vitro and in vincristine-induced traumatic injury models in vivo (53). SARM1 is an important NADase of the nervous system, yet it is still not known whether the enzyme contributes to NAD depletion in other tissues.

NAD CONSUMERS: CD38

CD38 was first observed on thymocytes and T lymphocytes (56) and is widely reported on immune, endothelial, and smooth muscle cells (9, 57–64). CD38 is upregulated in a cell-dependent manner by several stimuli in the presence of 1) proinflammatory or secreted senescence factors (9, 64–66) or in response to a bacterial infection (63, 67); 2) retinoic acid (68); or 3) gonadal steroids (60, 69). CD38 is stimulated in a cell-specific manner by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (9, 66, 70, 71). Among the NAD-degrading enzymes, CD38 is the main regulator of NAD levels in mouse tissues (51, 52, 72–74).

CD38 exhibits three main functions using NAD as a substrate. ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity produces cADPR and NAM, which represents <1% of the enzymatic activity of CD38. cADPR is a putative second messenger that induces calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum by binding to ryanodine receptors (75). CD38 also catalyzes a rare base-exchange reaction that substitutes the NAM group with an NA moiety, which produces NAADP and free NAM (76, 77). NAADP is a putative second messenger that mediates Ca2+ signaling acting on two-pore channel receptor (TPC) in acid endolysosomes (78) and is generated by CD38-dependent base-exchange reaction in vitro (76, 77, 79) with uncertain physiological relevance in vivo (7, 80, 81). Because the base-exchange reaction in vitro occurs in excess of NA and low pH (82), it may have some importance in specific cellular compartments such as the endolysosomal system (83). NAADP is also shown to mediate calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum through its interaction with the NAADP binding protein HN1L/JPT2 (hematological and neurological expressed 1-like protein/Jupiter microtubule associated homolog 2), which forms complex with ryanodine receptor 1 (84–86). Upon T-cell receptor (TCR)/CD3 complex stimulation, the dual NADPH oxidases DUOX1 and DUOX2 produce NAADP from NAADPH, eliciting calcium signaling that ultimately leads to T-cell activation (87). CD38 does not participate in NAADP formation in this context. Rather, CD38 appears to coordinate NAADP degradation in T cells, perhaps acting on the desensitization of the NAADP-dependent signaling (88).

Most significantly, CD38 NAD glycohydrolase activity produces ADPR and NAM and represents >90% of enzyme activity (89). ADPR acts on an intracellular domain of transient receptor melastatin 2 (TRPM2) channels, thus eliciting Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane (90). CD38 can also degrade NMN, producing NAM and, presumably, phosphoribose (52, 91), regulating NMN levels in vivo (64).

Although CD38 can be found in the cytoplasm and in the membranes of intracellular organelles, the vast majority of CD38 activity is in the plasma membrane, facing outside the cell (7, 92). That CD38 regulates NAD homeostasis inside the cell while its catalytic site faces the extracellular space has been known as the CD38 “topological paradox.” One explanation for this paradox is that the roles of extracellular and intracellular CD38 differ. For instance, whereas intracellular CD38 targets NAD for degradation, extracellular-facing CD38 additionally degrades the NAD precursor NMN, limiting the production of NAD intracellularly (51, 52, 64, 91). In addition to its function in NAD catabolism, CD38 is also required in purinergic signaling pathways, where it interacts with extracellular nucleotidases and modulates the production of the immunosuppressive molecule adenosine (93). Neither α-NAD derivatives, NR and NRH, nor reduced forms of NAD can be efficiently hydrolyzed by CD38 (24, 52, 94). CD38 also produces NAM as a product of intracellular NAD breakdown and as a product of NMN extracellular breakdown. Considering the importance of CD38 as the main NAD-consuming enzyme in the body (74), it may also be responsible for local NAM accumulation (36, 95) and subsequent inhibition of NAD-utilizing enzymes, but this possibility remains to be explored.

CD38 interferes with the activity of other NAD-dependent enzymes such as sirtuins. For example, CD38 inhibits sirtuins both by reducing NAD levels and by generating NAM, a well-characterized sirtuin inhibitor (36, 51, 96). Inhibition of CD38 by 78c, a specific and potent CD38 inhibitor, promotes protein deacetylation (51). Genetic deletion or inhibition of CD38 also protects mice from conditions that impair sirtuin activity such as a high-fat diet (97), dysregulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis in obesity (72), age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction (52), and d-galactose-induced myocardial cell senescence (98). Thus, the interplay between CD38 and sirtuins is an important component of the pathophysiology of diseases associated with NAD decline (Fig. 3).

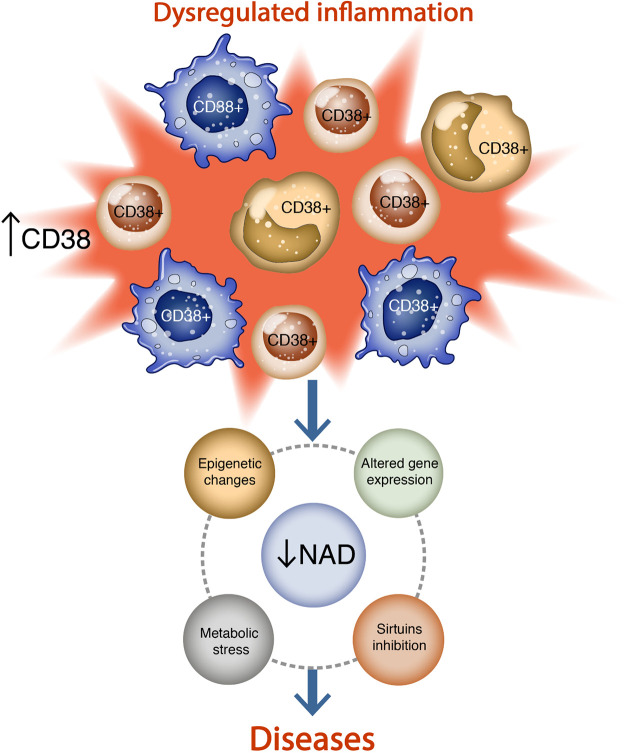

Figure 3.

Interplay between CD38, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) decline, and inflammation. Inflammatory signals induce the recruitment of CD38+ cells to a specific site, where increased CD38 activity leads to NAD decline, inhibition of sirtuins and epigenetic changes, altered gene expression, and metabolic stress.

CD38 AND INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Bacterial and Protozoan Infections

CD38+ immune cells are emerging as important pathogen responders. The reliance of bacteria on uptake of NAD precursors for NAD synthesis provides some insight into how CD38 might disrupt the metabolic demands of bacteria (99, 100). The presence of CD38 on immune cells is likely to be an evolutionary strategy for limiting availability of NAD precursors to bacteria and affecting infection control (7). Evidence in genetically altered mice suggests a role for CD38 in the innate immune response against pathogens. CD38-knockout mice have increased susceptibility to direct intratracheal administration of Streptococcus pneumoniae and intravenous administration of Listeria monocytogenes (101, 102). The recruitment of neutrophils to the site of infection is impaired in CD38-knockout mice, and neutrophil chemotaxis to the bacterial antigen fMLP is dependent on CD38/cADPR/Ca2+ signaling (101), but some controversy surrounds the contribution of ADPR versus cADPR in neutrophil recruitment (103). Macrophages derived from CD38-knockout mice are less efficient at engulfing Listeria than those from wild-type (WT) mice, but both are equally adept at killing bacteria (102) or limiting their growth (63). Interestingly, NAD decline, but not cADPR/Ca2+ signaling, induces cellular cytoskeleton modifications and protects macrophages from excessive bacterial internalization (63). Overall, the bacteriostatic effects of CD38 rely on modulation of immune cell migration/phagocytosis and on scarcity of NAD precursors, which may result in metabolic collapse in these microorganisms (7, 99). The effect of CD38 could be especially important for some bacteria such as Haemophilus influenzae that support metabolism by obtaining intact NAD or other precursors such as NMN from the surrounding environment (99, 100).

CD38 also protects against protozoan infections such as hepatic amoebiasis (i.e., Entamoeba histolytica) by potentiating CD38+ neutrophil migration to amoebic liver abscesses (ALAs) (104). In CD38-knockout mice, there is a delay in neutrophil migration compared with wild-type mice.

Viral Infection

The role of CD38 in viral infections is not well understood but is especially important given the emergence of novel viruses worldwide. Cell-specific increases in CD38 levels are found in patients infected with Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (105–107), but what role CD38 plays in mitigating infection remains unclear. One possibility is that CD38 modifies cytoskeletal dynamics required for immune cell migration by controlling either NAD levels or cADPR-dependent Ca2+ signaling (63, 101). Another alternative, which is observed in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, is CD38-mediated induction of innate immune response genes (e.g., IFN-β, IFN-λ1/IL-29, RANTES, MxA, ISG15) in a cADPR-dependent manner (108).

NAD dysregulation and decline occur in SARS-CoV-2 models of coronavirus infections as a consequence of NAD consumption by PARPs (109). Furthermore, accumulation of senescent cells is observed in a mouse model of coronavirus. In vitro, senescent cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2-derived spike protein produce a hyperinflammatory response (110). Aged coronavirus-infected mice administered senolytic drugs show a reduction in senescence, inflammation, and mortality (110). Given the clear association between the phenomenon of inflammaging, senescence, and CD38, as well as the impact of CD38 on degradation of NAD and the NAD precursor NMN (64, 65), future studies should focus on CD38 as a druggable target in viral illnesses (111, 112). Administration of NAD precursors for the purpose of boosting NAD levels in the presence of viral infections shows promise preclinically and in human clinical trials. For example, NAD boosting attenuates neuronal cell death and increases brain weight in mice infected with Zika virus (113), and administration of a combination of glutathione and NAD precursors in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection results in improved recovery (114).

In summary, CD38 participates in the innate immune response against bacterial, protozoan, and viral infections. Future studies on the role of CD38 in infection should explore how aging influences the immune response and whether the apparent resiliency observed in aging CD38-knockout mice extends to infection in humans.

CD38 IN AUTOIMMUNITY AND FIBROSIS

Autoimmune Disease

CD38 plays a critical role in inflammation, migration, and immunometabolism, but equally important is the resolution of the inflammatory response, if left unchecked, leads to loss of self-tolerance (115), tissue infiltration of lymphocytes, and circulation of autoantibodies (116). Mounting evidence suggests that CD38 acts as a double-edged sword in the formation of autoimmunity. Depending upon context, CD38 can either promote or protect against an autoimmune response (117–121). Here, the role of CD38 in four autoimmune disorders is discussed briefly and outstanding questions highlighted.

Systemic lupus erythematosus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) involves formation of autoantibodies against nuclear and cytoplasmic antigens (122, 123), resulting in tissue damage in multiple organs including skin and kidneys (124). Initial observations of dysregulated NAD metabolism in SLE show decreased ADP-ribosylation in patient-derived peripheral blood lymphocytes (125). Individuals with SLE have CD8+ T cells with high CD38 expression (CD8+CD38high) (117, 121, 126, 127) and accompanying NAD decline, Sirt1 inactivation, acetylation of the methyl-transferase EZH2, and subsequent suppression of cytotoxicity-related transcription factors (128). The result is a lower T-cell cytotoxic response observed in SLE, which predisposes patients to infection. Pharmacological inhibition of EZH2 restores cytotoxic capacity of CD8+CD38high T cells in SLE. What triggers increased CD38 expression in CD8+ T cells in this condition remains unknown.

Multiple sclerosis.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune degenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by inflammation, demyelination, and destruction of the blood-brain barrier (129). The pathogenesis of MS involves activation of microglia and macrophages, which when reversed significantly decreases disease severity (129). In a cuprizone (CPZ)-induced demyelination mouse model, CD38 is upregulated in both astrocytes and microglia (130). CD38 inhibition in this model attenuates glial activation and demyelination by restoring NAD levels. Furthermore, in a myelin-oligodendrocyte-glycoprotein (MOG)-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mouse model, CD38 is involved in T-cell activation (131), which is attenuated in CD38-knockout mice. Further studies are required to evaluate whether CD38 expression on inflammatory cells also disrupts NAD homeostasis in EAE.

Interestingly, a Western diet potentiates demyelination in the CNS of mice, which is improved by genetic ablation or pharmacological CD38 inhibition (132). Furthermore, CD38 levels increase in mouse spinal cord after chronic high-fat diet exposure, after focal toxin-mediated demyelinating injury, and in reactive astrocytes in active MS lesions (132). CD38-catalytically inactive mice are protected from high-fat-induced NAD depletion, oligodendrocyte loss, oxidative damage, and astrogliosis. Likewise, the CD38 inhibitor 78c increases NAD and attenuates neuroinflammatory changes in astrocytes treated with saturated fats in vitro (132). Taken together, a high-fat diet impairs oligodendrocyte survival and differentiation by a CD38-mediated mechanism and underscores the potential therapeutic value of CD38 inhibitors in myelin regeneration (132).

Inflammatory bowel disease.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an idiopathic chronic and progressive inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract mucosa that includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (133). The chronic mucosal inflammation and tissue damage characteristic of the disease predispose IBD patients to the development of colorectal cancer, and the risks increase with duration, extent, and severity of inflammation (134). CD38 expression is increased in macrophages from intestinal tissues of individuals with IBD (135). Additionally, IBD shows systemic chronic inflammation with increased activation of CD38+ T lymphocytes in the blood compared with healthy individuals (136, 137). Dysregulation of NAD metabolism partially explains the pathogenesis of IBD, which includes upregulation of the NAD consumers CD38, PARP9, PARP14, and SIRT1; the NAD synthesis enzyme NAMPT; and the NAD excretion enzyme nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT) (135).

The direct link between CD38 and intestinal inflammation is demonstrated in CD38-knockout mice in a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis model (119). Wild-type mice exposed to DSS display dense CD38+ cells in the mucosa, including resident T cells, granulocytes, and inflammatory monocytes, and exhibit weight loss, shortening of the colon, and alterations in the morphology of the epithelium, crypts, and submucosa. Conversely, CD38-knockout mice displayed only mild disease during DSS treatment (119). CD38 depletion is likely to be protective in DSS-treated mice because of impaired migration of immune cells to mucosal tissue. It is proposed that ADPR produced by CD38 breakdown of NAD acts on TRPM2, a plasma membrane Ca2+-permeable cation channel (119). Curiously, DSS-induced ulcerative colitis is also suppressed in TRPM2-knockout mice (138). It remains to be established whether CD38-induced cell migration, CD38-dependent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, and/or CD38 NADase activity contribute to the role of CD38 in intestinal inflammation.

Rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease more frequently observed in females and the elderly and associated with progressive disability and premature death. RA mainly targets the lining of synovial joints, includes extra-articular involvement, and results in inflammatory arthritis (139, 140).

Antibody-producing plasma cells and their B cell precursors contribute considerably to the pathogenesis of RA by synthesizing autoantibodies that either bind to tissue antigens or form immune complexes within tissues (9). CD38 is highly expressed in plasma cells compared with other immune cell populations in synovial biopsies and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (121). In fact, pathogenic autoantibodies such as anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies and rheumatoid factor (RF), synthesized by infiltrating plasma cells, are considered biomarkers of rheumatoid synovitis and serve to gauge the severity of RA and disease activity (141). Importantly, B cells, T cells, and macrophages, all of which express CD38, infiltrate the joint tissue (synovium), producing various proinflammatory cytokines that facilitate inflammation and ultimately destroy surrounding tissue (142).

CD38 expression is higher in synovial tissues of individuals with RA compared with other inflammatory conditions like ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and osteoarthritis (OA) (143). In the peripheral blood of RA patients, the proportions of CD38+ cells and CD38+ CD56+ cells [which represents CD38+ natural killer (NK) cells] are significantly higher, and the level of CD38+ cells correlates with the level of autoantibodies (143). CD38+ NK cells release proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α, which contribute to RA progression (144). Conversely, suppression of CD38 in cultured patient-derived synovial fibroblasts results in decreased IL-1α and IL-1β secretion (143).

Several drugs targeting CD38 show promise in the treatment and management of RA. Daratumumab, a CD38-targeting monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), reduces autoantibody levels (145) and depletes autoreactive plasma cells (145). Additionally, the anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody TAK-079 prevents arthritis by decreasing NK cells, B cells, and T cells in primates (146). Likewise, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, a competitive inhibitor of CD38 cyclase activity, ameliorates RA synovial fibroblast proliferation, IL-6 and IFN-γ levels, and the percentage of CD38+ NK cells in rats (144).

Future studies will seek to understand the implications of dysregulated NAD homeostasis in autoimmune conditions like RA and the ways in which targeting CD38 may reverse NAD-related metabolic imbalance (147).

Fibrosis

Differentiation of quiescent progenitor cells into activated myofibroblasts and their persistence is a common feature to all forms of fibrosis. However, what triggers the process remains obscure. Mounting evidence suggests that dysregulation of the NAD metabolome may underlie processes leading to fibrosis and, importantly, that CD38 may be a promising therapeutic target.

Systemic sclerosis.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a chronic systemic orphan disease associated with high mortality (148). A hallmark of SSc is synchronous fibrosis in multiple tissues including skin, lung, heart, and muscle that leads to permanent and irreversible organ dysfunction with no effective treatment (8). One hypothesis is that dysregulation of NAD metabolism resulting from the interplay of immune cells and fibroblasts plays a key role in SSc pathogenesis. Indeed, skin biopsies of SSc patients that show signatures of fibrosis have increased expression of key NAD-depleting enzymes including CD38 and NNMT (8). Conversely, genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition of CD38 in mice increases NAD levels in skin and lung and substantially attenuates bleomycin-induced fibrosis (8).

Pulmonary fibrosis.

Inflammatory processes are pathognomonic for common disorders of the lung [e.g., asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)]. Therefore, the link between CD38 and inflammatory diseases of the lung may shed light on early events contributing to fibrosis. Asthma pathophysiology involves a series of events including increased airway smooth muscle contractility, mucus hypersecretion, impaired lung elasticity, and disruption of epithelial integrity, which lead to airway narrowing and impact lung function (149). The influx of inflammatory cells contributes to airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), which is the main characteristic of asthma and defined as an exacerbated response to nonspecific stimuli present in the environment. Studies in CD38-knockout mice using different models of AHR such as inhaled methacholine, TNF-α, IL-13, or ovalbumin (OVA) challenge reveal a dual role for CD38 in airway smooth muscle (ASM) reactivity via cADPR-dependent Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum and modulation of inflammation (150–153). There is a paucity of data elucidating the role of CD38 as an NAD consumer in this context.

Pulmonary fibrosis occurs in the presence of unresolved inflammation and dysregulated tissue repair and results from an array of injurious stimuli including infection, toxicant exposure, adverse effects of drugs, and autoimmune response. Fibrosis is irreversible and is associated with a poor prognosis (154). Interestingly, CD38+ cells are found in the peripheral blood and in the bronchoalveolar space of individuals with pulmonary fibrosis (155, 156), although the contribution of CD38 remains unexplored. One possibility is that CD38 is involved in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (157). EMT is a phenotypic transition of epithelial cells necessary for normal tissue repair (158) but can be induced by stress and lead to loss of apical/basal polarization, loss of cell-cell adhesion, and acquisition of a fibroblast-like phenotype (158). Interestingly, it is reported that postinfluenza viral lung fibrosis observed in old mice is mediated by a subset of CD8+ cells (159). Additionally, CD8+ cells are shown to be enriched with CD38 in some studies (128, 160, 161). Thus, it is possible that CD38+CD8+ cells may contribute to lung fibrosis observed after viral infections such as influenza or coronavirus.

Renal fibrosis.

CD38 plays an important role in kidney physiology, namely renal vasoconstriction responsible for regulating both renal blood flow and glomerular filtration (162, 163). Renal vasoconstriction is controlled hormonally by angiotensin II (ANG II), endothelin-1 (ET-1), and norepinephrine (NE) (164), which in turn are modulated by CD38 expressed on preglomerular resistance arterioles (162). CD38-knockout mice display attenuated hemodynamic response to administration of ANG II, ET-1, and NE, which impact renal microcirculation functioning by reducing basal renal blood flow and urine excretion (162). Furthermore, thromboxane prostanoid (TP)-induced vasoconstriction is also mediated by CD38 (163). Additionally, CD38 is important for differentiation and function of podocytes, which are epithelial cells of the glomerulus that act as a glomerular filtration barrier (165, 166). Although the mechanisms are unknown, CD38 deficiency leads to podocyte EMT, resulting in enhanced glomerular injury and sclerosis (166).

CD38 deficiency significantly elevates levels of renal NAD (74, 167). The kidney is among the organs with the highest mitochondrial abundance (168). Therefore, regulation of NAD is critical for maintaining renal homeostasis. Reduced NAD+-to-NADH ratios (NAD+/NADH) are reported in numerous renal diseases including diabetic nephropathy (169) and acute kidney injury (AKI) (170–172) and in high-glucose-induced mesangial cell hypertrophy (173). By inhibiting CD38 or boosting NAD to increase NAD+/NADH and reduce mitochondrial stress, an improvement of renal conditions is observed. For example, inhibiting CD38 with apigenin restores NAD+/NADH and SIRT3 function in renal cells and improves renal injury in a model of diabetic nephropathy (174). In an LPS-induced AKI mouse model, inhibition of CD38 with quercetin ameliorates LPS-induced AKI and improves kidney function and inflammation by inhibiting LPS-induced M1 polarization and activation of NF-κB signaling in kidney macrophages (172). Supplementation with NR (175) and NMN promotes NAD boosting and protects against age-associated susceptibility to AKI (170). Similarly, NAM supplementation is associated with reduced AKI in cardiac surgery patients (171). These studies demonstrate that modulation of CD38 and NAD levels in kidney disease may provide therapeutic approaches for the prevention of inflammatory conditions of the kidney that predispose the kidney to fibrosis and altered function.

Cirrhosis.

Fibrosis is a critical step in the progression of most chronic liver diseases and a precursor of cirrhosis (176). Liver cirrhosis arises from a variety of conditions including alcoholism, chronic hepatitis virus infection, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), exposure to drugs and toxins, and inherited diseases among others (177, 178). Despite many etiologies of cirrhosis, some common pathological findings include degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes, appearance of regenerative nodules, and fibrotic tissue (176).

The specific role of CD38 in the development of liver cirrhosis is still unclear. An association between CD38 and cirrhosis is shown in a thioacetamide‐induced rat model of liver cirrhosis. Cirrhotic rat livers demonstrate increased CD38 expression and cyclase activity resulting in higher cADPR levels in liver microsomes (179). These findings raise the possibility that increased CD38 activity and cADPR could be involved in the pathogenesis of cirrhosis. Immunohistochemical studies in liver biopsies from patients with chronic liver disease show an increased number of CD38+ hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which are cells known to contribute to hepatic fibrosis (180). Furthermore, there is a positive correlation between the number of CD38+ HSCs and the METAVIR score, which is based on the intensity of necroinflammatory activity, interface hepatitis, and lobulitis. These findings highlight CD38+ HSCs as a potential biomarker of fibrosis in chronic liver diseases (180). Moreover, markers of inflammation and senescence are present in the pathophysiology of chronic liver diseases that progress to cirrhosis (181–186). CD38 plays a role in both inflammation and senescence. Age-related NAD decline and increased inflammation are partially mediated by senescence-induced accumulation of CD38+ inflammatory cells in tissues (64, 65). This may offer new insight into a role for CD38 in cirrhosis.

METABOLIC DISEASES

Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity is a disease of epidemic proportions and represents a major public health problem worldwide (187). Besides being a risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality, obesity is a feature of metabolic syndrome, which is a cluster of conditions that increase risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes, and stroke (188). CD38 plays a key role as a regulator of the obesity phenotype (97, 189), and inhibition of CD38 has the potential to ameliorate obesity and metabolic syndrome. In mice, CD38 deficiency results in a higher metabolic rate and resistance to high-fat diet-induced obesity (97). In humans, several lines of evidence positively associate CD38 with metabolic phenotypes including CD38 methylation and adiposity and linkage between CD38 and cholecystokinin A receptor genes and lipid levels (190–192). Previous studies also demonstrate a relationship between obesity and NAD decline in multiple metabolic tissues including liver, pancreas, and adipose (193, 194). Most notably, inhibition of CD38 ameliorates high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis and protects against obesity and metabolic syndrome by increasing availability of NAD (72, 194, 195). Taken together, elevation of NAD levels by genetic ablation of CD38 affords protection from the diet-induced insulin resistance, accumulation of fat, and metabolic inflexibility observed in wild-type mice (195), which is likely to translate to metabolic syndrome observed in humans.

In addition to its role as the primary NADase in mammalian tissues, CD38 regulates SIRT enzymes by regulating NAD availability (189). CD38-knockout mice show increased NAD levels compared with wild type and are protected against high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity, metabolic syndrome, glucose intolerance, and liver steatosis through a SIRT1-dependent mechanism. CD38-knockout mice also have higher energy expenditures compared with wild-type mice, with increased basal and activity-induced metabolic rates (97). The mechanism underlying these changes is mediated at least in part by NAD-dependent activation of SIRT1-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator α (PGC1α) axis and downstream effects on energy metabolism (97). Furthermore, SIRT1 regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and response to stress through the deacetylation of PGC-1α (196). Consistent with these findings, inhibition of CD38 by the small-molecule inhibitor 78c in mice ameliorates age-related glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, suggesting CD38 as a possible pharmacological target for aging-related metabolic dysfunction (51). A possible mechanism for amelioration of obesity through inhibition of CD38 is impaired adipogenesis and lipogenesis through the activation of a SIRT1-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) or a SIRT1-sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1) signaling pathway, respectively (197). Expression of adipogenic genes including PPARγ, fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα) is attenuated in CD38-knockout mice. In addition, in vitro expression of CD38 is increased during adipocyte differentiation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). CD38-deficient MEFs show increased expression of SIRT1 and downregulation of SREBP1‐mediated FASN (fatty acid synthase) expression, suggesting that CD38 may also influence lipogenesis. Altogether, these results suggest an important link between CD38 deficiency and the development of obesity through activation of Sirt1 signaling (197).

NAD-dependent SIRT3, which is localized in mitochondria, also plays a CD38-dependent role in obesity and other features of metabolic syndrome (197). To illustrate, CD38-knockout mice demonstrate improved glucose tolerance profiles compared with wild-type mice, but this observation is reversed in CD38/SIRT3 double-knockout mice (52). Furthermore, CD38-knockout mice exhibit increased oxygen consumption coupled to ATP synthesis compared with wild-type mice, a phenomenon that is also reversed in double-knockout mice. Taken together, these observations suggest that ablation of SIRT3 in CD38-knockout mice abrogates the protective effect of the CD38 inhibition in HFD-induced obesity, suggesting a role for NAD-dependent enzymes in obesity (52).

Alterations in white adipose tissue (WAT), in particular, may play a part in the pathogenesis of obesity and metabolic diseases (198). Low-grade chronic inflammation is characteristic of obesity and accompanied by macrophage infiltration in WAT (199, 200). Moreover, the observed macrophage burden and proinflammatory secretome of adipose tissue are correlated with obesity-associated metabolic derangements (201). Macrophage-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity are attenuated by quercetin, a CD38 inhibitor (202), which highlights the importance of CD38+ immune cells in the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases.

Curiously, CD38 is implicated in browning of white fat and the development of brown fat in mice. CD38 downregulation occurs during cold-induced thermogenesis and results in increased NAD+ and NADP(H) levels in brown fat (203). Thus, the role of CD38 in obesity and energy expenditure is linked to thermogenesis in brown fat through SIRT1-dependent mechanisms including the inactivation of the NAD/SIRT1/caveolin-1 axis (204, 205).

Taken together, CD38 inhibition resulting in increased NAD availability to SIRT1 and 3 may have therapeutic potential in the treatment of obesity-related metabolic syndrome.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

A common disease closely associated with metabolic syndrome is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD may lead to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the most common form of chronic liver disease characterized by inflammation and hepatocellular damage. Progression to fibrosis, the first stage of liver scarring, occurs in ∼32–37% of individuals with NASH and may increase risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (119, 206, 207). Comorbidities that accompany NAFLD including cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia often contribute to the morbidity and mortality of this disease (208).

SIRT1 and 3 appear to be important targets of NASH pathophysiology. Overexpression of SIRTs not only protects the liver from steatosis and progression to NASH but also can reverse effects of this disease (209–214). In a methionine and choline diet-deficient mouse model of NASH (209), sirtuins are downregulated, resulting in increased expression of lipogenic genes such as fatty acid synthase (215). Increased gene expression is observed as well in mice fed a HFD, which results in decreased NAD levels, reduced SIRT3 activity in liver, hyperacetylation of liver proteins, and reduced activity of mitochondrial complexes III and IV (213).

A role for CD38 in the pathophysiology of NASH has also been proposed. In a HFD model, CD38-knockout mice show significantly lower liver fat infiltration in comparison to wild-type control (97). Additionally, CD38 inhibition in a mouse model of HFD-induced obesity treated with the flavonoid apigenin demonstrates decreased lipid accumulation in liver through increased lipid oxidation, NAD boosting, and SIRT1 activation (72).

Taken together, these studies show a role for sirtuins and CD38 in metabolic syndrome and NAFLD and suggests that therapeutic interventions targeting SIRT1 activators or CD38 inhibitors or supplementation with NAD synthesis precursors may be beneficial for management of metabolic diseases (216–218). For example, NMN administration improves glucose metabolism in obese mice and muscle insulin sensitivity in prediabetic women (216, 217), whereas NR supplementation in mice activates both SIRT1 and SIRT3 and ameliorates metabolic dysfunction by improving mitochondrial function (219). In patients with mitochondrial myopathy, administration of niacin improves NAD metabolism and muscle function and decreases liver fat infiltration (220). Furthermore, NAD precursors, alone or in combination with other metabolic activators, have the potential to reverse obesity, enhance exercise performance, and ameliorate NAFLD (221–224).

AGING AND AGE-RELATED DISEASES

Inflammaging and NAD Decline

Tissue NAD levels decline with age and in progeroid syndromes (52, 225–228) despite NAD synthesis being relatively maintained (229). Boosting NAD levels in vivo is protective against some age-associated disorders in animal models (36, 230–233). One of the causes of NAD decline during aging is increase of NAD breakdown in the presence of increased CD38 expression and activity on immune cells, thus linking inflammaging with tissue NAD decline (51, 52, 64, 65). Other sources of NAD decline include increased DNA damage requiring PARP1 activation and decreased NAMPT levels leading to diminished NAD synthesis through the salvage pathway (216, 225, 226, 234–237).

Although age-related NAD decline seems to be multifactorial, CD38 appears to have a significant contribution in this process (51, 52, 64–66). Among the NAD-degrading enzymes, CD38 expression is upregulated with chronological aging in mice, whereas PARP1 and SIRT1 are downregulated (52). In addition, no changes are observed in the expression of NAD-synthesizing enzymes in multiple tissues in mice including liver, white adipose tissue (WAT), spleen, and skeletal muscle (52). Interestingly, CD38-knockout mice demonstrate a delayed age-related NAD decline with age compared with wild-type animals (52). This observation indicates that CD38 plays a major role in NAD dysregulation during aging. Moreover, CD38-dependent age-related NAD decline occurs as a consequence of SIRT3-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. SIRT3, a key modulator of mitochondrial metabolism, undergoes an age-related decrease in activity, causing increased acetylation of mitochondrial proteins and impaired mitochondrial function independent of mitochondrial biogenesis (52, 238). Aged CD38-knockout mice display more robust mitochondrial function including increased oxygen consumption rates, higher mitochondrial membrane potential, and a higher NAD+/NADH compared with wild-type aged mice (52). Administration of the highly potent and specific CD38 inhibitor 78c restores NAD levels and ameliorates metabolic dysfunction in aged mice, thus improving glucose tolerance, muscle function, exercise capacity, and cardiac function (51). 78c-induced NAD boosting also increases sirtuin and PARP activity; prevents the accumulation of telomere-associated foci (TAFs), a marker of DNA damage associated with aging; and promotes the activation of longevity pathways in tissues of aged mice (51). Taken together, CD38 is a critical regulator of NAD levels during the aging process in rodents.

Whereas CD38 plays a major role in aging-related systemic NAD decline, other mechanisms such as the downregulation of the NAD salvage pathway likely contribute to the NAD decline observed in specific tissues during aging. NAMPT is found inside the cells (iNAMPT) as well as in the extracellular environment (eNAMPT). Plasma eNampt released from adipocytes increases NAD levels in remote tissues such as the hypothalamus by increasing the capacity of the NAD salvage pathway. Increased NAD levels in the hypothalamus regulate SIRT1 activity and neural activation in response to fasting (239). The circulating levels of eNAMPT-containing extracellular vesicles (EVs) decrease with age both in mice and in humans (235). In addition, overexpression of NAMPT in adipose tissue increases NAD biosynthesis in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, pancreas, and retina. Exposure to circulating eNAMPT-containing vesicles results in increased physical activity and sleep quality, delayed aging, and extended life span (235). Conversely, NAMPT decline is correlated with decreased Sirt1 expression/activity in retinal pigment epithelium cells from old mice and in skeletal muscle of aged rats (236, 240). Although the age-associated decline in NAMPT expression is tissue specific, this decrease may also have a systemic impact.

In instances where there is an increase in NAD breakdown by CD38, there will be an excess of NAM. NNMT catalyzes the N-methylation of NAM using S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as a methyl donor, resulting in the generation of methyl-NAM and S-adenosyl-homocysteine (SAH) (Ref. 95, Fig. 1). Thus, increased NNMT expression has been associated with decreased cellular methylation capacity, reduced histone methylation, and alterations to the epigenetic landscape (95, 241). Also, by limiting the availability of NAM to the NAD salvage pathway, NNMT overexpression is associated with reduced NAD levels in specific contexts such as in high-fat diet-induced fatty liver disease (242) and obesity (243), thereby impacting NAD levels both in liver and in WAT. Accordingly, NNMT inhibitors are shown to increase NAD levels in adipocytes (244). NNMT expression increases in skeletal muscle of old mice, whereas NNMT inhibition enhances muscle regeneration in aging by rescuing muscle stem cell (muSC) function (245). Downregulation of Sirt1 activity as a result of NAD decline is a possible mechanism by which NNMT induces muSC activation in aged muscle tissue. Since NNMT is mostly associated with specific tissues such as liver and fat, it is unlikely that NNMT upregulation contributes to systemic NAD decline in aging. As a NAM generator, CD38 may upregulate NNMT activity in tissues such as fat and liver, thus contributing to a methylation sink, NAD decline, and metabolic dysfunction in specific organs. Whereas modulation of both NAMPT and NNMT expression seems to be context specific, the age-related increase in CD38 expression/activity appears to have the greatest impact on NAD levels.

CD38 also appears to play a wider role in aging by disrupting telomere integrity. In patient-derived cells from individuals with congenital telomere shortening, CD38 expression is higher, resulting in lower NAD levels and reduced PARP and SIRT1 activity (246). However, modification of systemic NAD metabolism by CD38 also occurs, at least partially, by way of circulating CD38-expressing immune cells that infiltrate tissues under inflammatory conditions. Indeed, inflammation is among the major risk factors that predispose organisms to age-associated diseases. During aging, the accumulation of senescent cells (SCs) creates an environment rich in proinflammatory signals, leading to “inflammaging” (247). SCs are metabolically active cells that lose their replicative capacity by entering an irreversible quiescent state and are considered both a cause and a consequence of inflammaging (248). SCs secrete several factors collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which in turn serves as a source of chemotactic factors for immune cell recruitment. SCs and SASP factors upregulate CD38 in bone marrow-derived macrophages and endothelial cells in culture as well as in vivo (64–66). Increased accumulation of CD38+ immune cell clusters is observed in WAT and liver during aging (64, 65). Furthermore, CD38-knockout mice receiving wild-type donor bone marrow cells accumulate CD38+ cells in tissues, indicating that these cells infiltrate from the circulation (64). In tissues where high levels of immune cells typically reside, such as spleen and intestine, NAD levels decline in CD38-knockout mice transplanted with bone marrow from WT mice. LPS treatment in this model leads to a decline in NAD levels as well (64). Furthermore, clearance of p16ink4a-positive cells from aged INK-ATTAC mice decreases CD38 expression and promotes recovery of NAD levels in WAT and liver (64). Blocking SASP production also leads to restored tissue NAD levels (64, 65). Moreover, the senescence-inducing agent doxorubicin reduces NAD levels in WT mice but has no effect in mice expressing a catalytically inactive form of CD38, thereby linking NAD decline, senescence, and CD38 activity. Taken together, these studies support a role for senescent cells and their SASP factors in the accumulation of CD38+ cells and age-related NAD decline (11, 64).

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death among the aged and by 2030 will result in 40% of all deaths in individuals aged 65 yr and older. An abundance of mitochondria in cardiac muscle ensures high levels of NAD, which is required to sustain the metabolic demands of the heart (249). Thus, the NAD-consuming CD38, which is present on nonparenchymal cells of the heart, is emerging as a target of pathogenesis as well as a druggable target in heart disease.

Heart failure.

Cardiac muscle requires high energetic demands because of continuous pumping of oxygenated blood throughout the circulation. Under physiological conditions, the heart relies almost entirely on the oxidation of short-chain fatty acids (250). However, during the development of heart failure, there is a shift from fatty acid oxidation to the utilization of other substrates such as carbohydrates and ketone bodies (251, 252). This transition leads to a decline in NAD+/NADH, which increases susceptibility to stress (252). Preclinical studies report that supplementation with NAD precursors such as NMN and NR prevents decline of NAD+/NADH and adverse cardiac remodeling in a mouse model of heart failure induced by pressure overload through transaortic constriction (253).

CD38 also plays a crucial role in the signaling pathway that leads to pathological cardiac hypertrophy in numerous models of heart failure. For example, in a mouse model of β-adrenergic stimulation-induced heart failure, genetic ablation of CD38 prevents myocardial hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and decreased fractional shortening/ejection fraction in a cADPR-dependent manner (254). CD38-dependent cardiac remodeling is also studied in both two-kidney, one-clip and angiotensin II continuous infusion heart failure models (255, 256). In the latter, the proposed mechanism is CD38 upregulation, inhibition of mitochondrial SIRT3 (by NAD depletion), mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation and dysfunction, and, consequently, cardiac hypertrophy. In this model, CD38-knockout mice are protected from cardiac hypertrophy (256).

One of the hallmarks of heart failure is the dysregulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in failing cardiomyocytes. A crucial feature is the decrease in expression and activity of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a), the most critical Ca2+-ATPase located in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of myocytes, which replenishes the intrasarcoplasmic Ca2+ pool to maintain a continuously efficient Ca2+ release (and therefore, contraction) in every beat. Decrease in SERCA2a activity and expression leads to a drop in reticular Ca2+ concentration, which causes insufficient contractility and impairs excitation-contraction coupling mechanisms (257). In this context, CD38-knockout mice have a higher SERCA2a-to-phospholamban (PLB) ratio than wild-type mice. Thus, what results is enhanced SERCA2a function with PLB inhibition (258). In addition, CD38-knockout male, but not female, mice demonstrate improved contractility, better contraction and relaxation velocities, and upregulated expression of SERCA2a, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), ryanodine receptor (RyR), and myosin heavy chain α isoform (α-MHC) (259).

Expression of the α-MHC isoform results in higher contraction velocity and attachment time with actin and improves contraction. These changes are associated with increased testosterone levels in CD38-knockout mice compared with wild-type mice, which is prevented by treatment with an androgen receptor antagonist (259). With age, the α-MHC-to-β-MHC ratio drops, leading to cardiac contraction impairment. This change is enhanced when heart failure is added to the equation. Therefore, upregulation of α-MHC by CD38 inhibition could lead to improved cardiovascular performance. Indeed, the CD38 inhibitor 78c significantly improves ejection fraction, fractional shortening, and other echocardiographic parameters related to cardiac strain compared with control aged mice (51). Interestingly, recent studies also indicate a role for NAD metabolism in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (260, 261). However, to date, the role of CD38 and NAD turnover has not been explored in this condition.

Myocardial infarction.

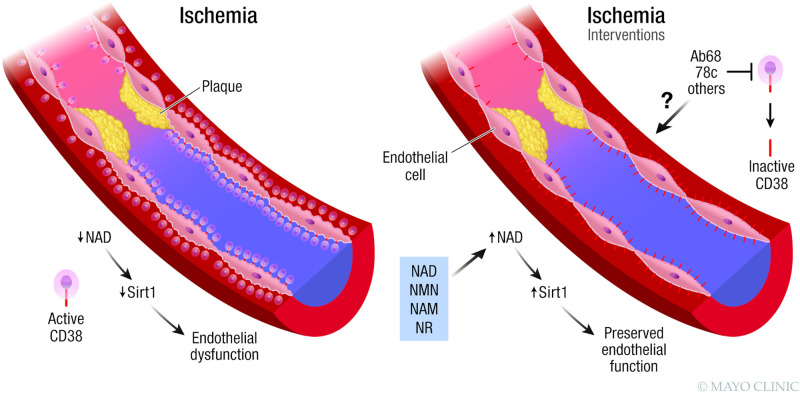

Ischemic heart disease is another cardiovascular disease of paramount importance due to its high prevalence. In an animal model of postischemic heart disease, CD38-dependent NAD and NADP depletion leads to endothelial dysfunction. In this study, CD38-knockout postischemic hearts show recovered endothelial function compared with wild-type hearts. In another in vitro model of ischemia-reperfusion of isolated heart, genetic ablation of CD38 results in postischemic protection by enhancing glutathione levels, improving contractile performance, reducing infarction size, and decreasing enzymatic release from cardiomyocytes compared with wild-type mice (262). After reperfusion, wild-type hearts present severe endothelial dysfunction due to uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), whereas CD38-knockout hearts display near-complete recovery of NOS-dependent coronary flow. Cardiac endothelial cells express high levels of CD38, whereas resident fibroblasts and actual cardiomyocytes express little CD38 (61). Predictably, endothelial cells present high CD38 NADase activity compared with other cell types. When subjected to hypoxia/ischemia, endothelial cells significantly increase expression and activity of CD38, leading to depletion of both NAD and NADP levels in heart and endothelial dysfunction (61). Another feature of the ischemic process in the heart is the metabolic shift toward glycolysis, leading ultimately to NAD depletion, a decline in ATP production, inactivation of ATPases, Ca2+ overload, and inevitable cell death (263). In this context, several studies report that boosting NAD levels by supplementation of NAD precursors increases mouse survival in a SIRT1-dependent manner (264). This evidence suggests an essential role of CD38 and NAD metabolism in mediating ischemia-reperfusion injury (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Ischemia and CD38. During ischemia there is increased expression of CD38 on endothelial cells in the vasculature, resulting in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) decline, downregulation of Sirt1, and endothelial dysfunction. NAD boosting by supplementation with NAD precursors has a protective effect on endothelial function. Although not yet extensively explored, CD38 inhibition could be a target to treat ischemia-induced endothelial dysfunction. NAM, nicotinamide; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NR, nicotinamide riboside. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, all rights reserved.

Vascular dysfunction.

Inflammation-associated metabolic diseases impair vascular function (265). Chronic inflammation can lead to vascular senescence and dysfunction. As discussed above, CD38 leads to NAD depletion related to metabolic syndromes and aging-related diseases (52, 64, 65). Accordingly, CD38 deficiency or NAD supplementation alleviates angiotensin II-induced vascular remodeling and dysfunction by increasing NAD levels in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (266). Increased NAD levels mitigate the degree of fibrosis in the vascular wall and, consequently, the media thickness, thereby preserving physiological pressure levels. This protection is also accomplished by decreasing the secretion of senescence-inducing factors, which are secreted from VSMCs and not bone marrow-derived cells (266). CD38 is also involved in vascular remodeling and dysfunction associated with diabetes (267). Under this pathological condition, CD38 upregulation leads to mitochondrial damage, VSMC remodeling, vascular wall fibrosis, and endothelium-independent dysfunction, which is tied to the activation of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and prevented by CD38 inhibitors (267).

Neurodegeneration

The relationship between pellagra pathophysiology and its effect on the nervous system (NS), when first described, revealed a link between NAD metabolism and proper NS functioning (268, 269). Functional pellagra is likely to cause premature aging and is a risk factor for neurodegeneration. Healthy aged brains demonstrate a decline of NAD+/NADH compared with the brains of younger subjects, and this decline has a potential impact on mitochondrial function (228). Furthermore, the hippocampus of 10- to 12-mo old mice shows a decline in NAD levels and the NAD rate-limiting enzyme NAMPT compared with 1-mo-old mice (270). Considering that CD38 expression and activity increase in multiple tissues and organs with age (52) and are detected in the CNS (130, 271–273), CD38 is proposed to have a role in age-associated neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and multiple sclerosis (MS).

AD is the most prevalent form of dementia (274) and is characterized by accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (275). CD38 promotes activation of microglia, the resident immune cells of the CNS. Furthermore, CD38 knockdown or 8-Br-cADPR treatment results in reduced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-stimulated murine microglial BV2 cells (276, 277). In one study, knockout of CD38 in AD‐prone mice (APP.PS.CD38-KO) results in decreased microglia/macrophage accumulation (278), reduced activity of α-, β-, and γ-secretases, less amyloidogenic Aβ peptide formation, and improved spatial learning (278). However, the role of CD38 in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases has not been well established. In fact, no functional or physiological data are presented in the studies described above (278).

Although a direct association with AD pathology remains to be determined, CD38 appears to play an important role in the nervous system. For instance, CD38 improves neuronal survival after cerebral ischemia by facilitating mitochondrial transfer from astrocytes to neurons, neurons to astrocytes, and astrocytes to astrocytes (272, 279). Mitochondria transfer is proposed to release extracellular mitochondrial particles mediated by CD38/cADPR signaling. The introduction of Alexander disease-associated point mutations into the GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) gene of astrocytes results in impaired mitochondrial transfer from astrocytes and decreased CD38 expression (279). It is not yet known how mutations in the GFAP gene affect CD38 expression. Moreover, changes in NAD levels are not shown to affect mitochondrial transfer among neuronal cells. Thus, CD38 participation in mitochondrial transfer deserves further investigation, particularly because of its potential neuroprotective function. Interestingly, transcriptome-wide association data identify CD38 as a possible gene associated with susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease (280). However, akin to AD, the role of CD38 in this condition is not well explored.

Cancer and Carcinogenesis

Cancer is the quintessential disease of aging, occurring on a backdrop of inflammation, failed DNA repair, senescence, and impaired immune surveillance (281). Because of high metabolic demand and reliance on NAD-dependent signaling, cancer cell growth is tied to NAD metabolism (282, 283). In fact, lowering levels of NAD/NADP by NAMPT inhibition is a promising anticancer strategy in both NAPRT-depleted and CD38-overexpressing tumors (283–285). In addition, NAMPT inhibition sensitizes cancer cells to oxidative stress and chemotherapeutics (283, 285). Interestingly, CD38 is shown to participate in both tumor progression and tumor suppression, depending on tumor type.

CD38 appears to play an important role in multiple myeloma (MM), the second most common hematological malignancy (286, 287). MM cells strongly express CD38, which is used as a marker for myeloma cell immunophenotyping (288, 289). A possible role for CD38 in MM appears to be related to the transfer of mitochondria from bone marrow stromal cells to MM cells via tunneling nanotubes, a process that supports oxidative phosphorylation in MM cells and contributes to cancer cell survival (290). It is still not clear, however, how CD38 facilitates this process. In astrocytes, CD38/cADPR/Ca2+ signaling is proposed to induce release of extracellular mitochondrial particles, promoting mitochondria transfer to adjacent neurons (272). Whether the CD38/cADPR/Ca2+ signaling axis is also part of tunneling nanotube formation in MM remains to be established. Therapeutically, anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies such as isatuximab and daratumumab are being investigated and used as therapies in patients with MM and other hematological malignancies (291, 292). The process by which anti-CD38 antibodies exert their anticancer effects is not completely understood and comprises several different mechanisms including complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) (291, 293–296).

Another hematological malignancy in which CD38 plays an important role is chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (297, 298). CD38 positivity in B-CLL cells is a prognostic factor, indicating decreased patient survival (299). Overexpression of CD38 increases aggressiveness of CLL, and CD38 inhibition by the flavonoid kuromanin results in downstream disruption of calcium signaling necessary for CLL chemotaxis, adhesion, and homing (300). Furthermore, migration and homing of CLL lymphocytes requires interaction between CD38 and its endothelial cell coreceptor CD31, which favors localization of neoplastic cells to growth-permissive sites (301). In addition to the CD38/CD31 axis, ADPR and NAADP signaling appear to mediate CD38-dependent effects of CLL migration via activation of the Ras family GTPase Rap1 through regulation of the Ca2+-sensitive Rap1 guanine-nucleotide exchange factor RasGRP2 (302). Not surprisingly, the anti-CD38 MAb daratumumab has antitumor effects in a partially humanized CLL xenograft model (303). Furthermore, anti-CD38 targeting agents modulate the tumor microenvironment by inducing apoptosis of B regulatory cell-like CLL cells and Treg cells, which have immunosuppressive roles. CD38 inhibition also increases activated cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, which target CLL cells (304). Thus, CD38 likely regulates the CLL microenvironment by modulating migration and proliferation of CLL cells, in addition to having immunomodulatory effects on B and T cells.

An alternative CD38-mediated mechanism of tumorigenesis relies on the interplay of adenosine (ADO)-generating ectonucleotidases expressed on tumor cells, stromal cells, and/or tumor-infiltrating immune cells (305). ADO is a signaling molecule that suppresses multiple immune subsets such as cytotoxic T cells via activation of purinergic receptors (306, 307). ADPR generated by CD38 can be used as a substrate by CD203a to generate AMP, a substrate for the primary adenosine-producing ectoenzyme CD73, which then produces ADO. ADO-producing ectoenzymes are expressed on multiple cell types within the tumor microenvironment or specifically on tumor cells (305). For instance, CD38 expressed on melanoma cells plays a prominent role in adenosinergic signaling leading to suppression of T-cell proliferation (308). Kuromanin-mediated inhibition of CD38 activity on melanocytes partially restores T-cell proliferation in coculture experiments. The immunosuppressive quality of the adenosinergic pathway highlights CD38 as a promising target for cancer immunotherapy (93, 305).

Cancer cells elude or modify the immune system by several mechanisms. One mechanism involves increased expression of cell surface immune checkpoint proteins such as the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), which binds to the programmed cell death 1 (PD1) receptor present on the surface of T cells (309). PD1/PD-L1 binding triggers T-cell suppression and prevents an antitumor cytotoxic response. By blocking PD1/PD-L1 binding, the immune system targets cancer cells that express high levels of PD-L1. Increased CD38 expression on tumors and the subsequent inhibition of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes via purinergic signaling is the main mechanism for reversing PD1/PD-L1 blockade in preclinical models of lung cancer (93, 310). Accordingly, coinhibition of CD38 and PD1/PD-L1 improves antitumor immune response (93, 310).

Another CD38-mediated protumor immune response is the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which are an immature cell population with immunosuppressive functions. Cancer-related inflammation alters myelopoiesis and stimulates generation of MDSCs, which in turn are recruited to tumor tissues in response to chemokines and act as a barrier to antitumor immunity (311). In a murine esophageal cancer model, administration of a CD38 antibody inhibits the expansion and survival of MDSCs (312). Moreover, CD38+ MDSCs are found in peripheral blood of advanced-stage cancer patients (312). Cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IGFBP3, CXCL16, and IL-6 induce CD38 expression in MDSCs, leading to expansion and maintenance of undifferentiated cells with greater immunosuppressive capacity and higher tumor-promoting activity (312). This mechanism is proposed to be mediated by CD38 induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), presumably through binding of CD38 to surface receptors. Another possibility is that the CD38 glycohydrolase activity modulates NAD-dependent signaling and alters gene expression to favor MDSC expansion. Taken together, CD38 is an important immune checkpoint for carcinogenesis with promising therapeutic potential.

CD38 may facilitate interaction between a tumor and its microenvironment including cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor-associated blood vessels by a mechanism yet to be elucidated. Tumor outgrowth induced by subcutaneous injection of melanoma cells is reduced in CD38-knockout mice compared with wild-type mice and is partially explained by fewer cancer-associated fibroblasts and reduced density of tumor-associated blood vessels in CD38-knockout mice (313). In an opposing scenario, CD38 expression is negatively correlated with disease progression in prostate cancer, in which low CD38 mRNA is prognostic for tumor recurrence and metastasis (314, 315). CD38 is epigenetically regulated in prostate cancer. Suppression of CD38 by methylation may increase the availability of extracellular NAD in prostate cancer and lead to disease progression (314). Higher CD38 expression results in lower NAD and leads to cell cycle arrest. The presence of CD38 also reduces glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolism, inhibits fatty acid metabolism, activates AMPK, and promotes a nonproliferative phenotype (316).

Similarly, the presence of CD38+ cells in hepatocarcinomas improves clinical outcome in cancer patients. Infiltration of CD38+ leukocytes in human hepatocarcinomas is correlated with better patient survival (317). Also, the presence of CD38+ M1 macrophages is associated with a positive prognosis after surgery (318). Although there is no direct evidence, CD38 may contribute to an antitumor immune response. Furthermore, CD38 expression sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to NAMPT-mediated metabolic collapse (284). In pancreatic cancer cells, CD38 overexpression reduces NAD levels and inhibits cell growth both in vitro and in a xenograft mouse model. In addition, CD38 knockdown in the pancreatic cancer cell line PaTu8988t results in increased NAD levels and resistance to NAMPT inhibition (284). Therefore, CD38-dependent NAD decline has possible antitumor properties. Akin to what is observed in an infection, CD38 plays a complex role in cancer biology that is highly cell and context dependent. These opposing effects of CD38 on cancer cells, inflammatory cells, and cancer stromal cells, which can be pro- or antitumor, can be explained by the multifunctionality of the ectoenzyme, which seems to be tissue specific and/or depend on interactions between the tumor and its microenvironment. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of understanding the role of CD38 in different types of cancer, in immune cells, and in the tumor microenvironment.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

NAD is a cofactor of paramount importance for an array of cellular processes related to mitochondrial function and metabolism, redox reactions, signaling, cell division, inflammation, and DNA repair. It is not surprising, therefore, that dysregulation of NAD is associated with multiple diseases. Since CD38 is the main NADase in mammalian tissues, its contribution to pathological processes has been explored in multiple disease models, and it is becoming evident that CD38 is a potential pharmacological target for several conditions. Although there may be links between disease and NAD decline, the role of CD38 in the pathogenesis of many of these diseases is still emerging. Studies presented in this review are largely based on animal models. Future studies are needed to explore the possibility of targeting the CD38-NAD axis for treatment of human diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Helen Diller Family Foundation, the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research via the Paul F. Glenn Laboratories for the Biology of Aging, Calico Life Sciences LLC, National Institute on Aging Grants AG-26094 and AG58812, and National Cancer Institute Grant CA233790 to E.N.C.

DISCLOSURES

E.N.C holds a patent on CD38 inhibitors licensed by Elysium Health. E.N.C. consults for Calico, Mitobridge, and Cytokinetics. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.D.Z., T.R.P., S.K., K.S.K., C.C.S.C., and E.N.C. conceived and designed research; J.D.Z. and E.N.C. analyzed data; J.D.Z. and E.N.C. interpreted results of experiments; J.D.Z. and G.A. prepared figures; J.D.Z., K.A.H., G.A., T.R.P., S.K., K.S.K., L.S.G., and D.Z.M. drafted manuscript; J.D.Z., K.A.H., G.A., T.R.P., S.K., K.S.K., L.S.G., D.Z.M., G.W., K.L.T., C.C.S.C., amd E.N.C. edited and revised manuscript; J.D.Z., K.A.H., G.A., T.R.P., S.K., K.S.K., L.S.G., D.Z.M., G.W., K.L.T., C.C.S.C., and E.N.C. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES