Abstract

Study Objectives

To determine whether subjective measures of exercise and sleep are associated with cognitive complaints and whether exercise effects are mediated by sleep.

Methods

This study analyzed questionnaire data from adults (18–89) enrolled in a recruitment registry. The Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI) assessed cognitive complaints. Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-SS) subscales and factor scores assessed sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, nighttime disturbance, and insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)-like symptoms. Exercise frequency was defined as the weekly number of exercise sessions. Exercise frequency, MOS-SS subscales, and factor scores were examined as predictors of CFI score, adjusting for age, body mass index, education, sex, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric conditions, and medical comorbidities. Analyses of covariance examined the relationship between sleep duration groups (short, mid-range, and long) and CFI score, adjusting for covariates. Mediation by sleep in the exercise-CFI score relationship was tested.

Results

Data from 2106 adults were analyzed. Exercise and MOS-SS subscales and factor scores were associated with CFI score. Higher Sleep Adequacy scores were associated with fewer cognitive complaints, whereas higher Sleep Somnolence, Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Problems Index I, Sleep Problems Index II, and factor scores were associated with more cognitive complaints. MOS-SS subscales and factor scores, except Sleep Disturbance and the insomnia factor score, mediated the association between exercise and cognitive complaints.

Conclusions

The relationship between exercise frequency and subjective cognitive performance is mediated by sleep. In particular, the mediation effect appears to be driven by symptoms possibly suggestive of OSA which are negatively associated with exercise engagement, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, and subjective cognitive performance.

Keywords: sleep, cognitive complaints, exercise, aging, insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, subjective cognitive function

Statement of Significance.

In this article, we present a novel framework wherein the relationship between exercise frequency and subjective cognitive function is, in part, due to the relationship between frequent exercise and sleep. Using self-report data from a large sample of community-dwelling adults, we found that worse subjective sleep quality and less frequent exercise were associated with more cognitive complaints. We further determined that the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints was mediated by sleep, most strongly by self-reported symptoms suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). These findings have important public health implications and may suggest that untreated OSA may negatively impact exercise engagement and subjective cognitive performance. Future prospective studies using objective measures of sleep, exercise, and cognitive function are needed to confirm these mediation effects, particularly in patients with OSA.

Introduction

Exercise and sleep support cognitive function across the adult lifespan. Exercise, defined as structured physical activity aimed at improving physical fitness [1], improves both objective and subjective aspects of cognition across adulthood [2]. In young adults, aerobic exercise training improves various aspects of cognition, however, cross-sectional findings are generally mixed [2]. In middle-age and older adulthood, aerobic exercise training improves working memory, response time, and executive control [3, 4]. On the other hand, insufficient physical activity (defined as < 150 min/week), increases risk for severe subjective cognitive complaints in middle-to-older-aged adults [5]. Frequent exercise engagement may preserve cognitive function in elderly individuals with subjective cognitive decline [6] and reduce the risk for age-related cognitive decline and incident dementia [7–11]. Similar to exercise, sleep supports numerous facets of cognition across adulthood, including episodic and working memory, and executive function [12]. Disturbed sleep, including sleep disorders such as insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), increase subjective cognitive complaints [13–15], accelerate cognitive decline [16], and increase risk for dementia [17, 18].

Accumulating evidence suggests that exercise influences sleep. Chronic exercise increases sleep duration, time spent in non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep, and improves sleep quality [19–22]. One meta-analytical study found that regular engagement in exercise (defined as ≥ 1 week of exercise) also reduces daytime sleepiness [22]. Engaging in physical exercise may also help to reduce OSA severity [23] and symptoms [24]. Exercise training has been shown to improve self-reported quality of life and sleep quality in patients with OSA, as well as reduce daytime sleepiness and disease severity [25]. It has been suggested that exercise may also be a viable non-pharmacological treatment for insomnia, as reductions in sleep complaints and sleep onset latency have been reported following both chronic [26] and acute moderate-intensity aerobic exercise [27] training in insomnia patients [28]. However, individuals with untreated OSA report less frequent exercise than patients undergoing treatment [29], and a lack of regular exercise may contribute to OSA-related daytime dysfunction [30]. Similarly, individuals reporting insomnia symptoms are more likely to be physically inactive [31].

These complex relationships between sleep (including OSA and insomnia symptomology) and exercise are important, as sleep and exercise likely act synergistically to influence cognitive function. An acute exercise bout was shown to improve mood in older adults with disrupted sleep [32]. Napping following an exercise bout yields a greater memory benefit than a nap or exercise alone [33]. In a large sample of adults aged 18 and older, sleep problems explained over 20% of the association between inadequate physical activity and cognitive difficulties [5]. A recent study demonstrated that sleep efficiency mediates the relationship between physical activity and executive function in older adults [34]. It is important to note, however, that while exercise and physical activity are related, these are independent constructs [1]. As opposed to the structured nature of exercise, physical activity refers to any body movement resulting in energy expenditure [1]. Thus, it is possible that frequent exercise may improve cognitive function, in part, through improving sleep. These combined effects may have particularly important implications in older adulthood—a time of marked changes in sleep architecture and physiology, as well as increased risk for sleep disorder [35]—as subjective cognitive complaints at baseline may predict future age-related cognitive decline [36].

To determine aspects of sleep that may mediate the effects of exercise frequency on subjective cognitive function across the adult lifespan, we analyzed survey-based measures evaluating subjective cognitive complaints, sleep, and exercise frequency (total number of exercise bouts per week) collected from a community-based sample of adults aged 18–89 interested in participating in clinical research. We performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate whether constructs of OSA-like symptoms, insomnia-like symptoms, daytime impact, and nighttime disturbance may drive these mediation effects. As a secondary set of analyses, we explored whether the frequency aerobic or strength/resistance exercise may play a more important role in these relationships. We hypothesized that self-reported features of sleep would mediate the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints.

Methods

Study participants

A total of 3933 participants were sampled from the University of California Irvine Consent to Contact recruitment registry [37]. Participants who self-reported ever having received a diagnosis of a major neurological disorder (mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease [AD], frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies) or psychiatric condition (i.e. bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcohol/drug abuse), reported taking AD-associated drugs (i.e. cognition-enhancing drugs) and/or drugs known to affect sleep (i.e., sedatives, anxiolytics, hypnotics), reporting fewer than 4 or greater than 10 h of sleep on average, or with incomplete data were excluded from analyses. A final sample of 2106 individuals aged 18–89 was analyzed. The final sample was 64.3% female with a mean age of 55.99 (±16.28) years. Additional sample characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Sample characteristics | Data (N = 2106) |

|---|---|

| Sex, no.of females (%) | 1349 (64.1) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 56.4 (16.2) |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 16.3 (2.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.6 (5.9) |

| CFI score, median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.5–3.5) |

| Total sleep time (hours), mean (SD) | 6.8 (1.2) |

| Exercise frequency, mean (SD) | 10.8 (7.8) |

| Race | |

| White, no. (%) | 1731 (82.2) |

| African American, no. (%) | 37 (1.8) |

| Asian, no. (%) | 137 (6.5) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native, no. (%) | 8 (0.4) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, no. (%) | 7 (0.3) |

| Other, no. (%) | 64 (3.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Latino, no. (%) | 1774 (84.2) |

| Non-Latino, no. (%) | 211 (10.0) |

| Medical comorbidities | |

| Liver disease, no. (%) | 31 (1.5) |

| Kidney disease, no. (%) | 54 (2.6) |

| Congestive heart failure, no. (%) | 16 (0.8) |

| Coronary artery disease, no. (%) | 79 (3.8) |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 111 (5.3) |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 538 (25.5) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, no. (%) | 453 (21.5) |

| Emphysema, no. (%) | 17 (0.8) |

| Sleep apnea, no. (%) | 236 (11.2) |

| REM sleep behavior disorder, no. (%) | 34 (1.6) |

| Blind, no. (%) | 24 (1.1) |

| Deaf, no. (%) | 44 (2.1) |

| Eczema, no. (%) | 131 (6.2) |

| Psoriasis, no. (%) | 55 (2.6) |

| Alopecia, no. (%) | 14 (0.7) |

| Vitiligo, no. (%) | 9 (0.5) |

| Cystic acne, no. (%) | 35 (1.7) |

| None of the above, no. (%) | 960 (45.6) |

| Prior cancer diagnosis, no. (%) | 539 (25.6) |

| Antidepressant usage, no. (%) | 315 (15.0) |

| Psychiatric history | |

| Major depressive disorder, no. (%) | 256 (12.2) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder, no. (%) | 98 (4.7) |

| None of the above, no. (%) | 1805 (85.7) |

Note that individuals could report more than one medical or psychiatric condition.

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; CFI, Cognitive Function Instrument; BMI, body mass index; Exercise frequency, total number of exercise bouts per week; No., number; %, percentage.

Subjective sleep assessment

Sleep was assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-SS) [38]. This scale has been associated with AD pathology in cognitively healthy adults with increased risk for AD [39, 40]. The MOS-SS is a 12-item self-report questionnaire that evaluates six sleep features during the last 4 weeks to derive five subscales: Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Adequacy, Sleep Somnolence, Sleep Problems Index I, and Sleep Problems Index II [41]. Questionnaire items and subscales are outlined in Supplementary Table S1.

Items comprising each subscale are related to certain sleep disorders and features. The Sleep Disturbance Scale evaluates sleep complaints common to Insomnia disorder, for example, difficulties with sleep initiation and continuity. The Sleep Adequacy Scale assesses perceived sleep quality, and the Sleep Somnolence Scale measures daytime sleepiness. Sleep Problems Index I and Index II are derived from items related to symptoms of both OSA and insomnia, such as waking short of breath or with a headache, and difficulty falling and staying asleep. Sleep Problems Index II differs from Index I in that it contains additional questions pertaining to sleep onset time, restlessness of sleep, and daytime sleepiness. Average reported total sleep time per night over the last 4 weeks was a priori binned into groups: short sleepers (4–5 h), mid-range sleepers (6–8 h), and long sleepers (9–10 h).

The original MOS-SS factor structure (as published) was derived using analytical approaches, but this structure may, at times, lack clinical utility as the Sleep Disturbance Scale and both Sleep Problems Indices include questionnaire items that capture a mix of insomnia and OSA-like sleep complaints [41]. We performed a CFA with the aim of grouping questionnaire items into clinically meaningful factors capturing symptoms suggestive of insomnia, OSA, nighttime disturbance, and daytime impact from the MOS-SS based on expert clinical judgment (R.M.B. and A.B.N.; see Statistical analyses section). We, therefore, sought to evaluate a structure of clinically derived factors to provide a more nuanced approach to investigating the relationships among sleep, exercise, and cognitive complaints using our available measures. Higher factor scores indicate greater frequency of these sleep symptoms.

Subjective cognitive complaints

Subjective cognitive complaints were evaluated with the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI) [42], which has been validated in non-demented elderly [43] and used to assess subjective cognitive complaints in a variety of conditions across adulthood [44–46]. The CFI consists of 14 questions assessing perceived cognitive and functional change compared to one year prior, scored as no (0), maybe (0.5), or yes (1). Total scores range from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating more cognitive complaints. Prior literature suggests that a score above two at baseline may predict future cognitive decline in older adults [43].

Exercise frequency

Exercise habits were evaluated using an 8-item questionnaire assessing how many days per week over the past year subjects participated in various forms of exercise for at least 15 min [7]. Questions specifically queried frequency of walking, hiking, bicycling, aerobics or calisthenics, swimming, weight training or stretching, and “another form of exercise.” Exercise frequency was determined by the total number of bouts per week. For secondary analyses, we further divided questionnaire items into the frequency of aerobic (walking, hiking, bicycling, aerobics or calisthenics, swimming) and strength/resistance (weight training or stretching) components.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS v26, RStudio Statistical Software (v1.1.463), and SAS (v 9.4). Assumptions for multiple linear regression were checked and CFI scores were log-base 10 transformed to meet assumptions of normality; a constant (1) was added to CFI scores during transformation to avoid log-base 10 of zero. Continuous covariates were age, body mass index (BMI), and years of education. Supplementary Figure S1 shows the probability density distribution of age in our sample. Supplementary Figure S2 shows the probability density distribution of average sleep duration by age (every 10 years) in our sample. Dichotomous covariates included biological sex, antidepressant usage, self-reported diagnosis of psychiatric conditions (major depressive disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder), prior diagnosis of cancer, and medical comorbidities (self-reported diagnosis of liver disease, kidney disease, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, emphysema, sleep apnea, REM sleep behavior disorder, blind, deaf, eczema, psoriasis, alopecia, vitiligo, cystic acne).

CFA was performed to derive factor scores from the MOS-SS based on our clinical understanding of sleep disorder symptomatology (A.B.N. and R.M.B.). Specifically, we proposed that the MOS-SS could be composed of four clinically relevant constructs, namely those capturing self-reported symptoms suggestive of insomnia (items 1, 7, 8), OSA (items 5, 10), nighttime disturbance (items 3, 4, 12), and daytime impact (items 6, 9, 11). To generate these factor scores, SAS PROC CALIS (SAS v.9.4) was used to run two CFA models, both requiring single item factor loading. In evaluating the structure of the constructs, Goodness-of-fit tests did not support the initial a priori CFA model (Tau-equivalence model), so an additional CFA was run with modifications removing the constraints of equal weighting within a factor. The results of the modified CFA did not meet criteria for overall global test of fit (X2 = 693.89, df = 38, p < .0001), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.093 (accepted cutoff < 0.06), but demonstrated relative fit parameters meeting criteria for acceptable fit (standardized root mean squared residual [SRMR] = 0.067 [accepted cutoff < 0.08], goodness of fit index [GFI] = 0.941 [accepted cutoff > 0.9], Bentler Comparative fit = 0.911 [accepted cutoff > 0.9]) [47]. The factor loadings are shown in Table 2; all t-scores reached statistical significance (ps < .0001). See Supplementary Table S2 for the factor correlation matrix (all ps < .05). Since it was not the objective of the CFA to determine a new factor structure for the MOS-SS, but rather to group items to represent clinically meaningful constructs (i.e. insomnia, OSA, nighttime disturbance, daytime impact), the acceptable relative fit and strong factor loadings gave confidence in using the resulting coefficients to create factor scores for analysis despite not meeting all criteria for fit on all established metrics. The unequal loadings of items within constructs also support the decision to utilize the factor scores for the analytic constructs rather than sum scores or averages [48]. SAS PROC SCORE was used to create the factor score values for each participant. To meet assumptions of normality, each factor score was natural log-transformed and a constant was added (+3) to account for negative factor scores or values below one.

Table 2.

Factor loadings and respective t-scores from confirmatory factor analysis

| Insomnia | OSA | Nighttime disturbance | Daytime impact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.9288 | — | — | — |

| t = 38.88 | ||||

| Item 7 | 1.3774 | — | — | — |

| t = 47.57 | ||||

| Item 8 | 0.8380 | — | — | — |

| t = 27.82 | ||||

| Item 3 | — | — | 0.8598 | — |

| t = 25.66 | ||||

| Item 4 | — | — | 0.9803 | — |

| t = 30.96 | ||||

| Item 12 | — | — | 1.1658 | — |

| t = 36.44 | ||||

| Item 5 | — | 0.5051 | — | — |

| t = 11.19 | ||||

| Item 10 | — | 0.4246 | — | — |

| t = 8.82 | ||||

| Item 6 | — | — | — | 1.1178 |

| t = 38.90 | ||||

| Item 9 | — | — | — | 0.9967 |

| t = 39.52 | ||||

| Item 11 | — | — | — | 0.6459 |

| t = 19.92 |

MOS-SS question items are depicted on the left. All loadings reached statistical significance (p < .0001).

To determine relationships between MOS-SS Subscales, MOS-SS factor scores, and CFI score, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted while adjusting for exercise frequency in addition to all covariates described above. Possible interactions between biological sex and sleep or exercise in predicting CFI score, as well as between sleep duration and exercise frequency in predicting CFI score, were additionally explored. As these potential interactions were secondary analyses, the results were not Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons. One-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to determine associations between sleep duration groups with CFI score, adjusting for the Sleep Somnolence Scale, exercise frequency, and all covariates described above. Another ANCOVA was performed to test for an association between sleep duration groups and exercise frequency, adjusting for all covariates described above. Robust standard error (SE) estimates were calculated to correct for heteroscedasticity, and all analyses were Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons unless stated otherwise. For multiple regression models predicting CFI score from MOS-SS subscales and factor scores, the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level for statistical significance was set to α = 0.005 (nine comparisons). For multiple regression models predicting MOS-SS subscales from exercise frequency, the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level for statistical significance was set to α = 0.01 (five comparisons). For multiple regression models predicting MOS-SS factor scores from exercise frequency, the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level for statistical significance was set to α = 0.0125 (four comparisons). Multiple regression models predicting sleep duration and CFI score from exercise frequency were not corrected for multiple comparisons as there were not multiple models predicting the same dependent variable (DV) from multiple independent variables (IVs; e.g. CFI score regressed on MOS-SS subscales and factor scores). As a secondary analysis, we further divided exercise frequency into aerobic exercise and strength/resistance components. For multiple regression models predicting CFI scores and MOS-SS subscales and factor scores from frequency of aerobic or strength/resistance exercise, the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level for statistical significance was set to α = 0.025 (two comparisons). Using the Hayes SPSS PROCESS Macro, ordinary least squares path analyses were performed to test for mediation (model 4) [49]. Mediation statistically tests a proposed mechanism by which an IV (exercise frequency) is related to a DV (cognitive complaints) through an intermediary variable (MOS-SS subscales or factor scores). The direct effect (c′) refers to the pathway from the IV to the DV, independent of the pathway through the intermediary variable. The indirect effect (a*b) refers to the pathway from the IV to the DV through the intermediary variable (see Figure 1 for a conceptual diagram). If the direct effect is statistically significant, this suggests that the independent and DVs are related independent of the proposed mechanism through the intermediary variable. If the direct effect is not statistically significant, this indicates a lack of evidence for a relationship between the IV and the DV independent of the proposed mechanism through the intermediary variable. To adjust for multiple comparisons in mediation analyses, 99% percentile-based bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) based on 5000 samples were calculated. When upper and lower CIs did not include 0, the indirect effect was considered statistically significant at the α = 0.01 level. Each PROCESS model included all covariates and robust SE estimates were calculated for each PROCESS model. To determine the potential influence of sleep apnea, sensitivity analyses were conducted by performing all primary analyses outlined above while excluding the subset of individuals self-reporting prior sleep apnea diagnosis.

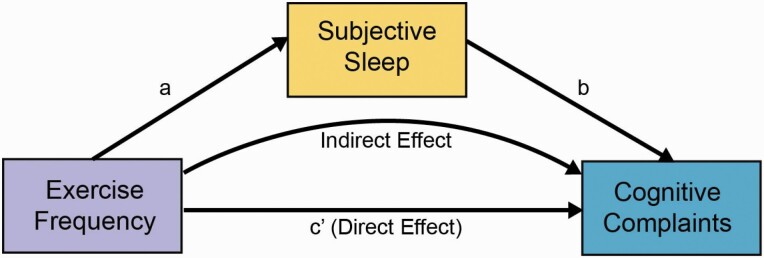

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of mediation analysis. Measures of subjective sleep mediate the association between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints.

Results

Exercise frequency is associated with cognitive complaints and self-reported sleep

First, we determined whether exercise frequency was associated with cognitive complaints. Multiple regression analysis using log-transformed CFI score as the DV, exercise frequency as the IV, and age, biological sex, BMI, years of education, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric conditions, and medical comorbidities as covariates (nine predictors, one outcome) revealed that more frequent exercise was associated with fewer cognitive complaints (β = −0.002, p = .011, Robust SE = 0.0009, t = −2.46).

Next, we determined whether exercise frequency was associated with self-reported sleep. Nine multiple regression models were constructed to predict each MOS-SS Sleep subscale or factor score (DVs) from exercise frequency (IV), while adjusting for age, biological sex, BMI, years of education, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric contditions, and medical comorbidities (nine predictors and one outcome in each model). Multiple regression analyses found that more frequent exercise was associated with greater sleep adequacy (β = 0.350, padj < .001, Robust SE = 0.072, t = 4.84), less daytime sleepiness (β = −0.251, padj = .001, Robust SE = 0.059, t = −4.27), and fewer sleep problems (Index I: β = −0.214, padj = .001, Robust SE = 0.051, t = −4.20; Index II: β = −0.227, padj < .001, Robust SE = 0.050, t = −4.52). More frequent exercise was also associated with lower OSA (β = −0.004, padj < .001, Robust SE = 0.0007, t = −5.27), lower Insomnia (β = −0.002, padj = .044, Robust SE = 0.0009, t = 2.55), Nighttime Disturbance (β = −0.005, padj < 0.001, Robust SE = 0.0009, t = −5.14), and Daytime Impact Factor Scores (β = −0.005, padj < .001, Robust SE = 0.0008, t = −5.670). Exercise frequency was not significantly associated with sleep disturbance (padj = .177). Sleep duration was not significantly associated with exercise frequency (p = .718). Thus, more frequent exercise was associated with better subjective sleep quality, less daytime sleepiness, lower OSA-related sleep problems, and fewer cognitive complaints.

Although recent work has demonstrated sex differences in the effect of exercise on cognitive aging [50, 51], we found no statistically significant interactions between biological sex and sleep subscales (IV) or factor scores (IV) or exercise frequency (IV) in predicting cognitive complaints (DV), while adjusting for age, BMI, years of education, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric conditions, and medical comorbidities (10 predictors and 1 outcome in each model). We also tested for an interaction between exercise frequency and sleep duration (IV) in predicting cognitive complaints (DV), while adjusting for age, biological sex, BMI, years of education, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric conditions, and medical comorbidities (11 predictors, 1 outcome), and did not find a moderating effect of sleep duration on the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints (p = .244).

We performed a secondary set of exploratory analyses to determine whether the frequency of aerobic or strength/resistance exercise may drive these relationships. Repeating the analyses described above, while adjusting for age, biological sex, BMI, years of education, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric conditions, and medical comorbidities, revealed that these results are primarily driven by the frequency of aerobic exercise (see Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

Self-reported sleep is associated with cognitive complaints

Each MOS-SS subscale was significantly associated with log-CFI score (multiple regression results summarized in Table 3; all adjusted ps < .001). Multiple regression analyses predicting log-CFI score (DV) from each MOS-SS subscale and factor score (9 models; 10 predictors and 1 outcome in each model), while adjusting for age, biological sex, BMI, years of education, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric conditions, medical comorbidities, and exercise frequency, indicated that higher scores on the Sleep Disturbance Scale, Sleep Somnolence Scale, both Sleep Problems Indices (I and II), and higher insomnia, OSA, Nighttime Disturbance, and Daytime Impact Factor Scores were all associated with more cognitive complaints, whereas higher scores on the Sleep Adequacy Scale were associated with fewer cognitive complaints. ANCOVA analysis predicting log-CFI from sleep duration groups, adjusting for daytime sleepiness (Sleep Somnolence subscale), age, biological sex, BMI, years of education, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric conditions, medical comorbidities, and exercise frequency (11 predictors, 1 outcome), revealed that sleep duration was also associated with cognitive complaints, as individuals who reported the longest (9–10 h) and shortest sleep duration (4–5 h) reported significantly more cognitive complaints (µ long = 0.527, p = .010; µ short = 0.545, p < .001) than mid-range sleepers (mid-range: 6–8 h, µ mid = 0.422).

Table 3.

Multiple regression models predicting CFI score from MOS-SS subscales and factor scores

| CFI score | N | β | SE | t | R 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Disturbance Scale | 2078 | 0.003 | 0.0003 | 10.503 | 0.141 | <.001 |

| Sleep Adequacy Scale | 2092 | −0.002 | 0.0003 | -8.980 | 0.126 | <.001 |

| Sleep Somnolence Scale | 2076 | 0.004 | 0.0003 | 12.075 | 0.156 | <.001 |

| Sleep Problems Index I | 2063 | 0.005 | 0.0004 | 14.323 | 0.178 | <.001 |

| Sleep Problems Index II | 2047 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | 14.497 | 0.182 | <.001 |

| OSA Factor Score | 2007 | 0.426 | 0.0267 | 15.980 | 0.195 | <.001 |

| Insomnia Factor Score | 2007 | 0.233 | 0.0228 | 10.240 | 0.137 | <.001 |

| Nighttime Disturbance Factor Score | 2007 | 0.276 | 0.0226 | 12.218 | 0.153 | <.001 |

| Daytime Impact Factor Score | 2007 | 0.335 | 0.0241 | 13.904 | 0.173 | <.001 |

Multiple regression models predicting CFI score from MOS-SS subscales and factor scores adjusting for age, biological sex, years of education, cancer diagnosis, BMI, antidepressant usage, medical comorbidities, psychiatric conditions, and exercise frequency.

CFI, Cognitive Function Instrument; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; β, unstandardized regression coefficient; SE, robust standard error estimates; R2, adjusted overall model fit; P, Bonferroni-adjusted P value.

Sleep quality mediates the effects of exercise frequency on cognitive complaints

To determine whether measures of subjective sleep quality mediated the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints, ordinary least squares path analyses were conducted using exercise frequency as the IV, log-CFI as the DV, and each MOS-SS subscale or factor score as the intermediary variable, while adjusting for age, biological sex, BMI, years of education, cancer diagnosis, antidepressant usage, psychiatric conditions, and medical comorbidities. A conceptual diagram of the mediation model is shown in Figure 1. Each MOS-SS subscale and factor score—aside from the Sleep Disturbance subscale and insomnia factor score—significantly mediated the association between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints.

More frequent exercise was associated with less daytime sleepiness (a = −0.251, p < .001, SE = 0.059, t = −4.27), which in turn, was associated with fewer cognitive complaints (b = 0.004, p < .001, SE = 0.0003, t = 12.07). Percentile-based bootstrapped CIs for the indirect effect did not include zero (99% CIs = −0.0017 to −0.0004). After adjusting for daytime sleepiness, however, the direct effect of exercise frequency on cognitive complaints was no longer significant (c′ = −0.001, p = 0.221, SE = 0.0009, t = −1.22), suggesting that the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints may be explained by the relationship between exercise frequency and daytime sleepiness. More frequent exercise was associated with better sleep adequacy (a = 0.350, p < .001, SE = 0.072, t = 4.84), which in turn was associated with fewer cognitive complaints (b = −0.002, p < .001, SE = 0.003, t = −8.98). Percentile-based bootstrapped CIs for the indirect effect did not encompass zero (99% CIs = −0.0014 to −0.0004). A direct effect of exercise frequency on cognitive complaints after controlling for sleep adequacy was not observed, supporting a full mediation by sleep adequacy (c′ = −0.001, p = .109, SE = 0.009, t = −1.60).

More frequent exercise was also associated with fewer sleep problems (Sleep Problems Index I: a = −0.214, p < .001, SE = 0.051, t = −4.19; Sleep Problems Index II: a = −0.227, p < .001, SE = 0.050, t = −4.52), which in turn were associated with fewer cognitive complaints (Sleep Problems Index I: b = 0.005, p < .001, SE = 0.0004, t = 14.32; Sleep Problems Index II: b = 0.006, p < .001, SE = 0.0004, t = 14.50). Percentile-based bootstrapped CIs for the indirect effects of both models did not include zero (99% CIs, Sleep Problems Index I: −0.0019 to −0.0005; Sleep Problems Index II: −0.0021 to −0.0005), and neither model provided evidence to support a direct effect of exercise frequency on cognitive complaints (Sleep Problems Index I: c′ = −0.001, p = .182, SE = 0.0009, t = −1.34; Sleep Problems Index II: c′ = −0.001, p = .205, SE = 0.0009, t = −1.27). The Sleep Disturbance Subscale did not significantly mediate the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints (99% CIs = −0.001 to 0.0001).

To parse out which sleep characteristics were driving the mediation effects, we separately included each factor score as a mediator of the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints. More frequent exercise was associated with fewer OSA-like symptoms (OSA Factor Score: a = −0.004, p < .001, SE = 0.0007, t = −5.27), which was in turn associated with fewer cognitive complaints (b = 0.426, SE = 0.027, p < .001, t = 15.98). Percentile-based CIs for the indirect effect did not include zero (99% CIs = −0.0025 to −0.0008). A direct effect of exercise frequency on cognitive complaints independent of the path through OSA-like symptoms was not supported (c′: −0.0004, p = .632, SE = 0.0009, t = −0.478). Nighttime disturbance and daytime impact also significantly mediated the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints. More frequent exercise was associated with less nighttime disturbance (Nighttime Disturbance Factor Score: a = −0.005, p < .001, SE = 0.0009, t = −5.14) and less daytime impact (Daytime Impact Factor Score: a = −0.005, p < .001, SE = 0.0008, t = −5.67), which in turn were associated with fewer cognitive complaints (Nighttime Disturbance Factor Score: b = 0.276, p < .001, SE = 0.023, t = 12.22; Daytime Impact Factor Score: b = 0.335, p < .001, SE = 0.024, t = 13.90). Percentile-based CIs for the indirect effects did not include zero (Nighttime Disturbance Factor Score: 99% CIs = −0.0019 to −0.0006; Daytime Impact Factor Score: 99% CIs = −0.0023 to −0.0008). Neither model provided evidence to support a direct effect of exercise frequency on cognitive complaints (Nighttime Disturbance Factor Score c′ = −0.0008, p = .372, SE = 0.0009, t = −0.892; Daytime Impact Factor Score: c′ = −0.0005, p = .552, SE = 0.0009, t = −0.594). Insomnia Factor Scores did not significantly mediate the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints (99% CIs = −0.00108 to 0.00004). Exercise frequency did not mediate any relationship between MOS-SS subscales or factor scores and cognitive complaints (see Supplementary Table S5). Secondary analyses investigating whether MOS-SS subscales or factor scores mediate the relationship between either aerobic or strength/resistance exercise and cognitive complaints again revealed that aerobic exercise frequency may be primarily driving these relationships (see Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). Importantly, all the relationships reported above persisted after excluding individuals who self-reported a prior diagnosis of sleep apnea (see Supplementary Tables S8–S10).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of 2106 adults, subjective reports of dysregulated sleep (i.e. disturbance, somnolence, and sleep problems) were significantly associated with cognitive complaints. Exercise frequency effects on cognitive complaints were mediated by specific sleep features—adequacy, somnolence, and sleep problems suggestive of both insomnia and OSA (Sleep Problems Indices). To better characterize which sleep symptoms were driving these effects, we performed a CFA based on our understanding of the clinical presentation of insomnia and OSA. We also derived two-factor scores of nighttime disturbance and daytime impact. Greater insomnia, OSA symptoms, nighttime disturbance, and Daytime Impact Factor Scores were all associated with cognitive complaints. Interestingly, each factor score, aside from the insomnia factor score, significantly mediated the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints. These results may suggest that sleep deficits and associated daytime dysfunction could diminish the effects of exercise on cognitive preservation.

Sleep quantity was related to subjective cognition, as mid-range sleepers reported fewer cognitive complaints than individuals who reported sleeping for shorter or longer periods. This relationship was independent of daytime sleepiness, suggesting that sleep duration may be independently associated with subjective cognitive function. Our finding that 6–8 h of sleep may be optimal for subjective cognitive performance is consistent with the literature, as too much or too little sleep has been associated with cognitive decline and other adverse health outcomes [52–55]. More frequent exercise was also associated with improved sleep quality, reduced daytime sleepiness, fewer sleep problems, less nighttime disturbance, and fewer insomnia and OSA-like sleep symptoms. However, it is possible that individuals reporting greater daytime sleepiness are simply less inclined to exercise often [56]. MOS-SS subscales and items evaluating sleep difficulties—specifically Sleep Disturbance and the Sleep Problems Indices—are derived from questionnaire items that assess symptoms implicated in various sleep disorders, namely insomnia and OSA, which could explain observed relationships between exercise frequency, subjective sleep, and cognitive complaints. The OSA and insomnia factor scores further support this notion.

The Sleep Disturbance subscale gauges difficulty in sleep initiation and sleep fragmentation, two hallmark components of insomnia disorder [57]. The suggested insomnia factor score further parsed out insomnia-like sleep complaints and was also associated with more cognitive complaints. Although cognitive impairment in insomnia is controversial [58, 59], self-reported symptoms of impaired functioning are prevalent and included in disorder diagnosis [57]. Some studies indicate that cognitive complaints in insomnia are associated with worse objective performance [60], whereas other studies show unimpaired performance despite cognitive complaints [61]. The combination of hyperarousal in insomnia, short sleep duration, and circadian rhythm dysregulation likely play a role in cognitive outcomes and contribute to the observed association between insomnia and heightened AD risk [17, 62].

Each aspect of sleep that was assessed by the MOS-SS—aside from the Sleep Disturbance Scale and insomnia factor score—mediated the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints. The independent associations between exercise, sleep quality, and daytime somnolence, are consistent with the work of other research groups and literature [19, 20, 63, 64], and the effects of sleep on cognition are well-established [65]. However, our findings support a novel framework wherein exercise may improve subjective cognitive function in part through improving sleep. That the Sleep Disturbance subscale and insomnia factor scores were the only sleep components that did not mediate this relationship was somewhat surprising given that several studies have reported improved subjective and objective aspects of sleep in response to physical exercise in insomnia patients [26–28]. However, one study in insomnia patients found no relationship between exercise and subjective or objective sleep parameters the corresponding night [66]. The strong association between self-report of insomnia-like symptoms and cognitive complaints is consistent with the literature [59, 60].

Both Sleep Problems Indices and the OSA factor score significantly mediated the association between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints. The Sleep Problems Indices assess symptoms of both insomnia and OSA, and both are associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment and AD [17, 67]. We found a significant mediating role for the Sleep Problems Indices that was not observed with the Sleep Disturbance subscale, which assesses mostly insomnia-like symptoms. This may suggest that OSA-related sleep symptoms may play a specific role in the mediating effects of sleep. This is further supported by our mediation models using the insomnia and OSA factor scores, as only the OSA factor score mediated the relationship between exercise frequency and cognitive complaints.

OSA is characterized by cessation of breathing during sleep due to partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway leading to intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation, which triggers oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby damaging neural tissue [68]. OSA affects roughly 9%–38% of the general population and prevalence increases to as much as 84% in older age groups [69]. Self-reported symptoms of OSA include excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, daytime impairment, and subjective and/or observed respiratory disturbance or apnea [70]. If left untreated, OSA is associated with reductions in gray matter [71] and damage to the medial temporal lobes [72, 73], which is thought to underlie OSA-related neurocognitive impairment. Individuals with OSA report more cognitive complaints than individuals without OSA [74] and are at higher risk for cognitive decline [17, 67, 75]. It is possible then that these findings indicate that frequent exercise may impact apnea symptoms to improve subjective cognition, as one study reported improved apnea symptoms following an aerobic exercise intervention independent of weight change [23]. However, it is also equally plausible that these findings indicate that our sample contains a significant number of individuals with undiagnosed OSA, as individuals with untreated OSA exercise less frequently [29], report daytime impairment, and cognitive complaints which could contribute to the observed mediation effects with the MOS-SS Sleep Somnolence Subscale, Sleep Problems Indices, and the OSA and Daytime Impact Factor Scores. It is important to note that a fraction of participants in this sample self-reported an OSA diagnosis, and this was adjusted for in all models. However, individuals who self-report OSA diagnosis are more likely to be treated, thereby mitigating their influence on these outcomes. Importantly, analyses were conducted excluding individuals who self-reported OSA diagnosis and these effects persisted. However, many individuals with OSA are undiagnosed, and therefore untreated OSA may still contribute to the observed relationships [76]. Future studies should evaluate these relationships in treatment naïve and treated OSA patients to further validate these findings.

These data suggest that exercise may influence cognitive function through improving sleep. The potential mechanisms supporting this relationship are not yet fully understood, but recent work suggests that autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity and inflammatory factors may play a role. Heart rate variability (HRV) is an indicator of neurocardiac function reflecting ANS parasympathetic activity. Low HRV has been linked to worse subjective sleep quality [77] and other adverse health outcomes, including risk for cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality [78], and cognitive decline [79]. Aerobic exercise training has been shown to increase HRV in OSA patients [80] and healthy older adults [81]. Changes in HRV may be an indirect pathway by which exercise improves sleep, as a recent study in a sample of middle-to-older aged adults found that the effects of aerobic exercise training on subjective sleep quality were partially mediated by changes in HRV [77]. It has also been proposed that the production of peripheral inflammatory factors, such as the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6), may be another mechanism for exercise-related changes in sleep quality [82]. IL-6 is secreted by skeletal muscle during exercise performance as a function of exercise intensity and duration [83]. IL-6 typically exhibits a circadian fluctuation, peaking during nocturnal sleep and reaching a nadir during wake [84]. High levels of IL-6 are related to sleep disturbance [85] and short sleep duration [86]. While an acute bout of exercise may increase IL-6, aerobic exercise training (3 days/week for 6 months) reduces plasma levels of IL-6 and improves measures of sleep continuity in older adults [87]. Thus, it is possible frequent engagement in exercise may reduce peripheral markers of inflammation to promote better quality sleep.

This study employed a large sample size that afforded us sufficient statistical power to uncover relationships that have important public health implications, while adjusting for a variety of potential confounders. However, there are also some limitations. Because this study is based on self-reported cross-sectional data, causality cannot be inferred, and we were unable to adjust for potential self-report bias. We are unable to determine whether other lifestyle behaviors, such as caffeine or alcohol intake, affected participants’ subjective assessment of sleep, as these behaviors were not evaluated as part of the recruitment registry. Longitudinal data are also needed to confirm these relationships and to ensure that individuals who exercise more frequently do not just happen to also report good sleep and overall health. In addition, our results may not generalize due to self-selection bias and a lack of diversity, as our sample predominantly consisted of adults residing in Orange County, CA. The study sample also consisted of a relatively large proportion of individuals reporting a prior cancer diagnosis (24.6%). Due to registry limitations, we are unable to determine whether these subjects have an active diagnosis, are currently undergoing treatment, or are cancer survivors—all of which may impact sleep, exercise engagement, and subjective cognitive performance. The clinical factor structure derived from the MOS-SS was constructed by two active clinician scientists. Evaluation of this structure will require an expert panel to reach consensus to yield clinical factors most appropriately. Additionally, study-partner CFI was not collected in our sample, which may limit our sensitivity in detecting cognitive change as the combination of self and study partner reports yield more insight into participant cognitive function [88]. Future studies incorporating objective data, such as overnight polysomnography and electroencephalography, measurements of HRV, or assessments of peripheral inflammatory profiles would help to link this conceptual framework to candidate biophysiological mechanisms supporting the synergistic effects of exercise and sleep on cognition. Despite these limitations, the findings from this study lead to a conceptual framework to inform future mechanistic studies on the relationships between sleep, exercise, and subjective cognitive performance.

In conclusion, the current study provides evidence that across the adult lifespan, the relationship between self-reported exercise frequency and cognitive complaints is mediated by sleep. More specifically, the relationship between frequent exercise and cognitive complaints appears to be mediated by sleep symptoms possibly suggestive of untreated OSA in our sample. These findings extend the current body of literature by assessing subjective reports of sleep, exercise, and cognitive function in tandem in a large sample of adults across age ranges. Most prior literature examining these relationships has substantially focused on aspects of sleep quality or duration in restricted age groups. The current study expands upon this literature by assessing sleep disorder symptomatology, which is often exclusionary, in a large sample across the adult lifespan. Furthermore, this study demonstrates how these sleep symptoms relate to exercise and cognitive complaints, which is a risk factor for age-related cognitive decline and dementia [43]. These findings also offer further specificity that it is aerobic exercise (and not strength/resistance training) that appears to impact perceived cognitive function through sleep. The development of factor scores reflecting potential sleep disorder symptomology from the MOS-SS is also novel and could provide clinical utility for future studies. These results have important implications for exercise-based studies aimed at improving cognitive function or preventing age-related cognitive decline, as the presence of undiagnosed sleep disorders, such as insomnia or OSA, may limit their effectiveness. These findings underscore the importance of sleep health and highlight the need for sleep assessment in the context of exercise interventions.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA F31AG074703, PI: Chappel-Farley, NIA R01AG053555, PI: Yassa; NIA K01AG068353, PI: Mander), the American Academy on Sleep Medicine Strategic Research Award (PI: Benca), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH T32 MH119049). The Consent-to-Contact Registry was made possible by NIA P50 AG016573, NIA P30 AG066519, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences NCATS UL1 TR001414, and a philanthropic gift by HCP, Inc.

Disclosure Statement

Financial Disclosure: None to Declare.

Nonfinancial Disclosure: Dr. Benca has served as a consultant to Eisai, Genomind, Isorsia, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Yassa has served as a consultant for Eisai, Pfizer, and Dart Neuroscience, and is Chief Scientific Officer for Signa Therapeutics. Dr. Mander has served as a consultant to Eisai. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

References

- 1. Caspersen CJ, et al. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Voss MW, et al. Exercise, brain, and cognition across the life span. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2011;111(5):1505–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dustman RE, et al. Aerobic exercise training and improved neuropsychological function of older individuals. Neurobiol Aging. 1984;5(1):35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kramer AF, et al. Ageing, fitness and neurocognitive function. Nature. 1999;400(6743):418–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Felez-Nobrega M, et al. Physical activity is associated with fewer subjective cognitive complaints in 47 low- and middle-income countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(10):1423–1429.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahn S, et al.. Effects of physical exercise on cognition in persons with subjective cognitive decline or mild cognitive impairment: a review. J Parkinsons Dis Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Larson EB, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cass SP. Alzheimer’s disease and exercise: a literature review. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2017;16(1):19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kramer AF, et al. Exercise, cognition, and the aging brain. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2006;101(4):1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nelson ME, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1435–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garber CE, et al. ; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scullin MK, et al. Sleep, cognition, and normal aging: integrating a half century of multidisciplinary research. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(1):97–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kang SH, et al. Subjective memory complaints in an elderly population with poor sleep quality. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(5):532–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee JE, et al. Effect of poor sleep quality on subjective cognitive decline (SCD) or SCD-related functional difficulties: results from 220,000 nationwide general populations without dementia. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsapanou A, et al. Sleep and subjective cognitive decline in cognitively healthy elderly: results from two cohorts. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(5):e12759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bubbico G, et al. Subjective cognitive decline and nighttime sleep alterations, a longitudinal analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shi L, et al. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;40:4–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lim AS, et al. Sleep fragmentation and the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in older persons. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1027–1032. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uchida S, et al. Exercise effects on sleep physiology. Front Neurol. 2012;3:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chennaoui M, et al. Sleep and exercise: a reciprocal issue? Sleep Med Rev. 2015;20:59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dolezal BA, et al.. Interrelationship between sleep and exercise: a systematic review. Adv Prev Med. 2017;2017:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kredlow MA, et al. The effects of physical activity on sleep: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 2015;38(3):427–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kline CE, et al. The effect of exercise training on obstructive sleep apnea and sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2011;34(12):1631–1640. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kline CE, et al. Exercise training improves selected aspects of daytime functioning in adults with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(4):357–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lins-Filho OL, et al. Effect of exercise training on subjective parameters in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2020;69:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Passos GS, et al. Is exercise an alternative treatment for chronic insomnia? Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67(6):653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Passos GS, et al. Effect of acute physical exercise on patients with chronic primary insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(3):270–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lowe H, et al. Does exercise improve sleep for adults with insomnia? A systematic review with quality appraisal. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;68:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stevens D, et al. ; SAVE investigators. CPAP increases physical activity in obstructive sleep apnea with cardiovascular disease. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(2):141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Basta M, et al. Lack of regular exercise, depression, and degree of apnea are predictors of excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with sleep apnea: sex differences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(1):19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haario P, et al. Bidirectional associations between insomnia symptoms and unhealthy behaviours. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(1):89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alfini AJ, et al. Impact of exercise on older adults’ mood is moderated by sleep and mediated by altered brain connectivity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2020;15(11):1238–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mograss M, et al.. Exercising before a nap benefits memory better than napping or exercising alone. Sleep. 2020;43(9). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilckens KA, et al. Physical activity and cognition: a mediating role of efficient sleep. Behav Sleep Med. 2018;16(6):569–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mander BA, et al. Sleep and human aging. Neuron. 2017;94(1):19–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hohman TJ, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints and longitudinal changes in memory and brain function. Neuropsychology. 2011;25(1):125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grill JD, et al. Constructing a local potential participant registry to improve Alzheimer’s disease clinical research recruitment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(3):1055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hays R, et al.. Sleep measures. In: Stewart A, Ware J, eds. Measuring Functioning and Well-being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992:235–259. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sprecher KE, et al. Amyloid burden is associated with self-reported sleep in nondemented late middle-aged adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(9):2568–2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sprecher KE, et al. Poor sleep is associated with CSF biomarkers of amyloid pathology in cognitively normal adults. Neurology. 2017;89(5):445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Spritzer K, et al. MOS Sleep Scale: a Manual for Use and Scoring. Santa Monica, Los Angeles, CA: RAND; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Walsh SP, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group. ADCS prevention instrument project: the Mail-In Cognitive Function Screening Instrument (MCFSI). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4 Suppl 3):S170–S178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li C, et al. The utility of the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI) to detect cognitive decline in non-demented older adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60(2):427–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lal C, et al. Impact of medications on cognitive function in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(3):939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lal C, et al. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome on cognition in early postmenopausal women. Sleep Breath. 2016;20(2):621–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Singh A, et al. World Trade Center exposure, post-traumatic stress disorder, and subjective cognitive concerns in a cohort of rescue/recovery workers. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(3):275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hu LT, et al.. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 48. DiStefano C, et al. Understanding and using factor scores: considerations for the applied researcher. Pract Assessment Res Eval. 2009;14:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-based Approach. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Casaletto KB, et al. Sexual dimorphism of physical activity on cognitive aging: role of immune functioning. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:699–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stern Y, et al.. Sex moderates the effect of aerobic exercise on some aspects of cognition in cognitively intact younger and middle-age adults. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ma Y, et al. Association between sleep duration and cognitive decline. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2013573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cappuccio FP, et al. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Covassin N, et al. Sleep duration and cardiovascular disease risk: epidemiologic and experimental evidence. Sleep Med Clin. 2016;11(1):81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Butler MJ, et al. Suboptimal sleep and incident cardiovascular disease among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study (JHS). Sleep Med. 2020;76:89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chasens ER, et al. Daytime sleepiness, exercise, and physical function in older adults. J Sleep Res. 2007;16(1):60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.American Psychiatric Association. Sleep-wake disorders. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013;361–422. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fortier-Brochu E, et al. Insomnia and daytime cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(1):83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Riedel BW, et al. Insomnia and daytime functioning. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4(3):277–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fortier-Brochu E, et al. Cognitive impairment in individuals with insomnia: clinical significance and correlates. Sleep. 2014;37(11):1787–1798. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Orff HJ, et al. Discrepancy between subjective symptomatology and objective neuropsychological performance in insomnia. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1205–1211. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chappel-Farley MG, et al.. Candidate mechanisms linking insomnia disorder to Alzheimer’s disease risk. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2020;33:92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yang PY, et al. Exercise training improves sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2012;58(3):157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kelley GA, et al. Exercise and sleep: a systematic review of previous meta-analyses. J Evid Based Med. 2017;10(1):26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Walker MP. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1156:168–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Baron KG, et al.. Exercise to improve sleep in insomnia: exploration of bidirectional effects. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;9(8):2239–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bubu OM, et al.. Sleep, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2017;40(1):1–18. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li Y, et al. Neurobiology and neuropathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnea. Neuromolecular Med. 2012;14(3):168–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Senaratna CV, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Macey PM, et al. Brain morphology associated with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Macey PM, et al. Sex-specific hippocampus volume changes in obstructive sleep apnea. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;20:305–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Owen JE, et al.. Neuropathological investigation of cell layer thickness and myelination in the hippocampus of people with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2018;42(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vaessen TJ, et al. Cognitive complaints in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;19:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bubu OM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, cognition and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review integrating three decades of multidisciplinary research. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;50:101250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Young T, et al. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1217–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tseng TH, et al. Effects of exercise training on sleep quality and heart rate variability in middle-aged and older adults with poor sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(9):1483–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Thayer JF, et al. The role of vagal function in the risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Biol Psychol. 2007;74(2):224–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kim DH, et al. Association between reduced heart rate variability and cognitive impairment in older disabled women in the community: Women’s Health and Aging Study I. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(11):1751–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cipriano LHC, et al. Effects of short-term aerobic training versus CPAP therapy on heart rate variability in moderate to severe OSA patients. Psychophysiology. 2021;58(4):e13771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Stein PK, et al. Effect of exercise training on heart rate variability in healthy older adults. Am Heart J. 1999;138(3 Pt 1):567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tan X, et al. The role of exercise-induced peripheral factors in sleep regulation. Mol Metab. 2020;42:101096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Petersen AM, et al. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;98(4):1154–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Irwin MR. Sleep and inflammation: partners in sickness and in health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(11):702–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Cho HJ, et al. Sleep disturbance and longitudinal risk of inflammation: moderating influences of social integration and social isolation in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;46:319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Irwin MR, et al. Implications of sleep disturbance and inflammation for Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Santos RV, et al. Moderate exercise training modulates cytokine profile and sleep in elderly people. Cytokine. 2012;60(3):731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Amariglio RE, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Tracking early decline in cognitive function in older individuals at risk for Alzheimer disease dementia: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Cognitive Function Instrument. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(4):446–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.