Abstract

Background and Aims

We aimed to quantify the magnitude of the association between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence [symptom relapse] in patients with postoperative Crohn’s disease.

Methods

Databases were searched to October 2, 2020, for randomised controlled trials [RCTs] and cohort studies of adult patients with Crohn’s disease with ileocolonic resection and anastomosis. Summary effect estimates for the association between clinical recurrence and endoscopic recurrence were quantified by risk ratios [RR] and 95% confidence intervals [95% CI]. Mixed-effects meta-regression evaluated the role of confounders. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the relationship between these outcomes as endpoints in RCTs. An exploratory mixed-effects meta-regression model with the logit of the rate of clinical recurrence as the outcome and the rate of endoscopic recurrence as a predictor was also evaluated.

Results

In all, 37 studies [N = 4053] were included. For eight RCTs with available data, the RR for clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence was 10.77 [95% CI 4.08 to 28.40; GRADE moderate certainty evidence]; the corresponding estimate from 11 cohort studies was 21.33 [95% CI 9.55 to 47.66; GRADE low certainty evidence]. A single cohort study showed a linear relationship between Rutgeerts score and clinical recurrence risk. There was a strong correlation between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence treatment effect estimates as trial outcomes [weighted Spearman correlation coefficient 0.51].

Conclusions

The associations between endoscopic recurrence and subsequent clinical recurrence lend support to the choice of endoscopic recurrence to monitor postoperative disease activity and as a primary endpoint in clinical trials of postoperative Crohn’s disease.

Keywords: Postoperative Crohn’s disease, endoscopic recurrence, clinical recurrence

1. Introduction

Despite important advances in medical therapy,1 bowel resection to manage complications or treat refractory disease is necessary in approximately half of patients with Crohn’s disease [CD].1–3 However, surgery is not a cure and recurrence is common. Conceptually, postoperative recurrence includes both endoscopic and clinical recurrence. Endoscopic recurrence in the neoterminal ileum, defined empirically as a Rutgeerts’s score of ≥ i2 on ileocolonoscopy, occurs in 30% to 90% of patients within 1 year of surgery.1,2,4 Importantly, the presence and severity of endoscopic recurrence is generally considered a strong predictor of subsequent clinical recurrence1,2,5 on the basis of a previous cohort study conducted by Rutgeerts and colleagues.5 However, confirmatory large-scale prospective cohort studies are lacking, and cross-sectional studies have demonstrated considerable heterogeneity in both endoscopic and clinical recurrence rate estimates during the first postoperative year, with the former ranging from 30% to 90% and the latter from 10% to 40%.1,6

In an effort to inform clinical practice, the American Gastroenterological Association [AGA] has defined two risk categories for recurrence of CD following surgical resection. High-risk patients are defined by the presence of any of the following: age <30 years at diagnosis, current smoking, and/or two or more previous surgeries for penetrating disease with or without perianal disease.2 Low-risk patients are defined as those aged >50 years at diagnosis, non-smokers, with a first surgery for a short segment of fibrostenotic disease [<10 to 20 cm], and after longer disease duration [>10 years].2 It should be recognised that these definitions do not consider the relative independent strength of association of these risk factors and, importantly, the use of these risk categories for clinical decision making has not been validated. Other groups have attempted to develop models for low versus high risk of postoperative recurrence,7,8 but none of these models has been validated. Despite these limitations, the AGA suggests use of prophylactic thiopurines and/or tumour necrosis factor [TNF] antagonists in patients who are at high risk for clinical recurrence.

Alternatively, endoscopic monitoring is recommended for low-risk patients. In this strategy, patients are evaluated by ileocolonoscopy at regular intervals and if high-grade recurrence develops, defined by a Rutgeerts score ≥i2, treatment is initiated with agents that have been shown effective for active disease. Although the AGA recommends that all patients should undergo ileocolonoscopy at 6 to 12 months after surgical resection, surveillance for endoscopic recurrence is likely most relevant for patients not receiving pharmacological prophylaxis.2

The effect of endoscopic surveillance was evaluated in the POCER trial, in which 174 patients with CD were randomised 2:1 to active care plus colonoscopy 6 months after surgery [n = 122] or standard of care with no colonoscopy 6 months after surgery [n = 52].7 All patients initially received metronidazole and then additional therapy was added based on the risk of recurrence, defined by smoking, perforating disease, or previous resection. High-risk patients [>80% in both groups] received thiopurines and treatment was escalated to adalimumab if there was evidence of Rutgeerts ≥i2. At 18 months, endoscopic recurrence occurred in 49% of patients in the active care group compared with 67% of patients in the standard care group [p = 0.03]. Whereas endoscopic evaluation may help guide therapeutic escalation in at-risk patients, the risk stratification algorithm used in POCER has not been validated and does not capture other reported risk factors, and the optimal timing of ‘early’ colonoscopy to identify recurrent lesions remains unclear.

Given these clinical practice issues, it is not surprising that clinical trial endpoints are equally problematic. A case can be made to use endoscopic recurrence as the primary endpoint for trials of postoperative prophylaxis because, presumably, endoscopic recurrence precedes clinical recurrence in all patients.1,2 Furthermore, it is recognised that clinical symptoms poorly reflect inflammatory disease activity in the postoperative setting, due to the presence of altered anatomy, individual pain sensitivity, and other confounding factors including bile acid-related diarrhoea and bacterial overgrowth.9–12 Consequently, it has been suggested that endoscopic recurrence should be designated as the primary endpoint in postoperative trials and that clinical recurrence, defined by patient-reported outcomes, should constitute a key secondary outcome. However, regulatory agencies have expressed concern with this approach, based primarily upon uncertainty regarding the clinical relevance of endoscopic recurrence. Further understanding of the relationship between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence, and the potential influence of other putative risk factors is needed. Specifically, compelling evidence documenting the strength of the relationship and whether or not prevention of endoscopic recurrence results in clinically meaningful benefit for patients is needed before regulatory authorities accept endoscopic recurrence as a surrogate measure that could be used as a primary endpoint for trials in postoperative CD aimed at assessing novel therapeutics.

The primary objective of this systematic review was to quantify the magnitude of the association between endoscopic recurrence, defined using the Rutgeerts score, and clinical recurrence in randomised controlled trials [RCTs] and cohort studies performed in the postoperative CD setting.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis based on Cochrane methodology,13 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA] statement.14 MEDLINE [Ovid, 1946], Embase [Ovid, 1947], and the Cochrane Library [CENTRAL] were searched from inception to October 2, 2020, to identify eligible studies [see Supplementary Appendix 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. The search was limited to English language studies. There were no other limits. The references of relevant articles and conference proceedings including Digestive Disease Week, the United European Gastroenterology Week, and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation Congress were hand-searched to ensure all eligible studies were identified.

2.2. Study eligibility

RCTs and cohort studies of adult [≥18 years] patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CD, and who had had at least one ileocolonic resection and ileocolonic anastomosis, were considered for inclusion. All medical interventions for prevention of recurrence of postoperative CD were considered for inclusion. Potential interventions included 5-aminosalicylates, budesonide, thiopurines, methotrexate, antibiotics, small molecules [e.g., tofacitinib], biologics [e.g., infliximab, adalimumab, vedolizumab], prebiotics, probiotics, and vitamins. To be considered for inclusion, studies must have reported on the proportion of participants with endoscopic recurrence of CD as defined by the Rutgeerts score, the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease [SES-CD], or the Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity [CDEIS] score.

2.3. Outcomes of interest

Our goal was to assess the strength of association between endoscopic recurrence and subsequent clinically meaningful outcomes in postoperative CD. The primary outcome of interest was clinical recurrence as defined by the included studies. We also collected data on the need for an additional surgery for CD, hospitalisation, treatment escalation, and quality of life [e.g., the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire—IBDQ]. To be considered for inclusion, studies must have reported on at least one of these clinically meaningful outcomes.

2.4. Data screening, extraction, and quality assessment

Two authors [JKM, JC] independently screened titles and abstracts in duplicate. Potentially relevant publications were screened in full to determine eligibility for inclusion. Disagreement was discussed until consensus was reached. A third author [RS] acted as the arbiter if consensus could not be reached. Two authors [JKM, JC] independently extracted data from the included studies in duplicate. A study-specific form was used to collect data. Extracted information included study characteristics [e.g., study design category, year of publication, country, number of participants, study arms, study interventions, drug doses, number of follow-up visits, and duration of follow-up], participant characteristics [e.g., age, gender, disease duration, disease location, disease severity, history of concomitant diseases, smoking status, risk group, and number of previous resections], predictors [e.g., proportion of participants with endoscopic recurrence], and outcomes [e.g., clinical recurrence, additional surgery, hospitalisation, treatment escalation, and quality of life]. If data were missing or reported in a way that did not allow for extraction, authors of the original publication were contacted for additional information.

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two authors [JKM, JC] in duplicate using the Cochrane risk of bias tool and the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale [NOS]. Studies with an NOS score of 7 or greater were judged to be at low risk of bias, studies with an NOS score of 4 to 6 were judged to be at high risk of bias, and studies with an NOS score of 0 to 3 were judged to be at very high risk of bias.15 Disagreement between authors were resolved by discussion and consensus.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Since each outcome was binary, we considered risk ratios [RR], odds ratios [OR], and risk differences [RD] as measures of association. The RR using a robust standard error was used as our primary measure. The OR and RD were pooled but were only included in the supplementary information. The RR was defined as the ratio of the probability of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence versus the probability of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence. The RD was defined as the difference between these two probabilities. The OR was defined as the ratio of the odds of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence versus the odds of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence.

Measures of association were pooled, overall and separately for RCTs and cohort studies, using a random-effects model. These were pooled separately to reflect the differences between study design. A random-effects model was selected to account for both within- and between-study variability. To allow for a more symmetrical scale, RRs and ORs were pooled using a log transformation. Point estimates and associated 95% confidence intervals [95% CIs] were then converted back to the original scale. Heterogeneity was assessed using the chi square test and the I2 statistic. An I2 value ≥75% indicates high heterogeneity among the study data, ≥50% indicates moderate heterogeneity, and ≥25% indicates low heterogeneity. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing outliers to determine if the pooled effect estimates were robust to changes in the data or analyses. A study was defined as an outlier if its confidence interval did not overlap with the confidence interval of the pooled effect.16

Mixed-effects meta-regression analyses with log RRs as outcome variables were used to assess the effect of study-level characteristics on the association between clinical recurrence and endoscopic recurrence. Clinical judgement was used to establish factors for inclusion in the meta-regression. Potential sources of clinical heterogeneity were evaluated by constructing stratum-specific RRs for various patient and trial-level covariates. Statistical heterogeneity within these strata was quantified using I2 and Q-test statistics.17 A value below 50% represents lower levels of heterogeneity.18

An additional univariable meta-regression model was used to evaluate the effect of the endoscopic recurrence rate on the clinical recurrence rate. Assuming the existence of between-study variability, the model used the logit of the clinical recurrence rate as the outcome and the rate of endoscopic recurrence as the predictor.

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation [GRADE] criteria were applied to assess the overall certainty of the evidence. Evidence from RCTs was initially considered high quality; however, it can be downgraded due to risk of bias, indirect evidence, inconsistency [unexplained heterogeneity], imprecision, and publication bias.19 Outcomes with less than 35 events were reduced by two GRADE levels; outcomes with less than 300 events were reduced by one GRADE level. Evidence from observational studies was initially considered low quality; however, it could potentially be upgraded due to the presence of a large treatment effect [e.g., at least a 2-fold increase or reduction in risk], when a dose-response gradient existed, or when all plausible confounders would have reduced the effect.20

Meta-analyses, meta-regression, and subgroup analyses were performed using the Metafor package for R [version 2.4-0]. All other analyses were conducted using base R [version 4.0.1].

3. Results

3.1. Search results

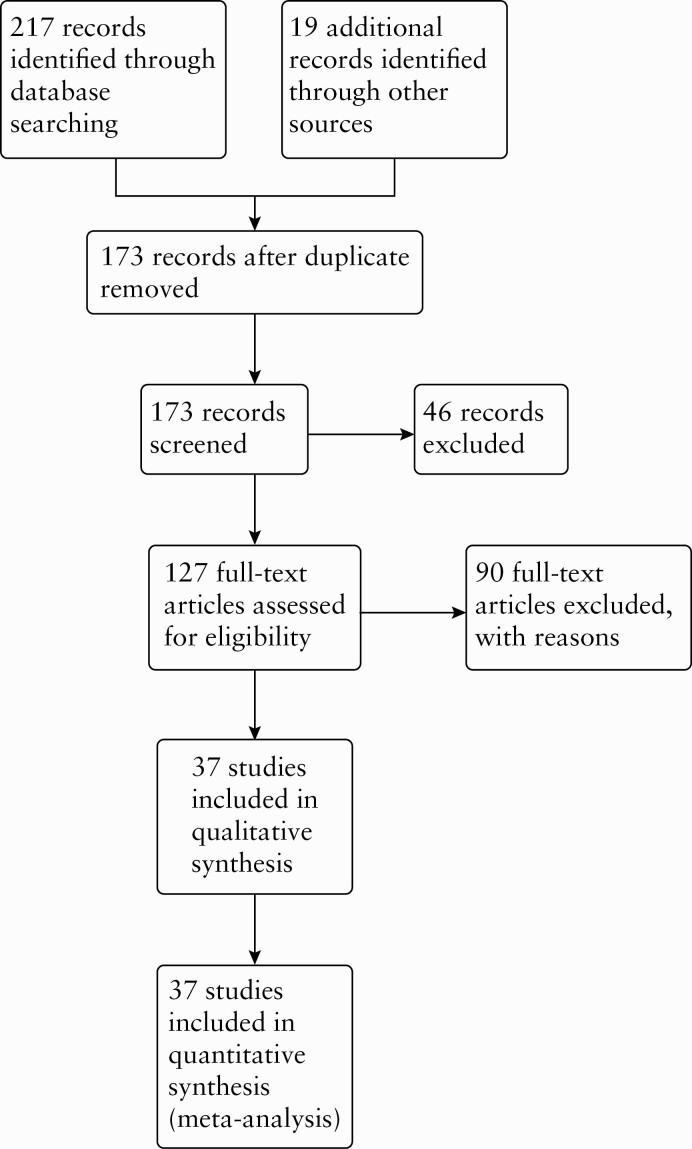

The literature search was conducted on October 2, 2020, and identified 217 records. Nineteen additional records were identified through other sources. After duplicates were removed, we screened 173 records for inclusion. We selected 127 records for full-text review. Ninety full-text articles were excluded with reasons [see Supplementary Table 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. Overall, 37 studies including 22 RCTs,7,8,21–40 nine prospective cohort studies,5,41–48 and six retrospective cohort studies49–54 met the pre-defined inclusion criteria and were included in this review [see Figure 1]. The characteristics of included studies including study type [i.e., RCT or cohort], medication, length of follow-up, definition of endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence, and patients’ risk of recurrence [i.e., high risk and low risk of postoperative recurrence] are reported in Supplementary Table 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram summarising the study selection process and results.

The Cochrane risk of bias analysis for RCTs is reported in Supplementary Figure 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online. Most of the included RCTs were rated as low risk of bias. Six RCTs were rated as high risk of bias for unblinded allocation,21 unblinded treatment,7,21,30,35,39 unblinded outcome assessors,21 and incomplete outcome data.37 The risk of bias analysis for cohort studies and RCTs is reported in Supplementary Table 3a and b, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online. Nine cohort studies were rated as low risk of bias,5,43–46,48,49,52,53 and six cohort studies were rated as high or very high risk of bias.41,42,47,50,51,54 All of the RCTs were rated as low risk of bias. Studies were most often downgraded for comparability, as few cohort studies matched for cases and controls in the study design or controlled for any confounders in their statistical analyses. Furthermore, few studies described how completeness of follow-up was confirmed.

3.2. Included studies

Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of the included studies. The majority of RCTs were designed as two-arm [19/22; 86%], phase 3, multicentre [16/22; 72%] trials, investigating an immunosuppressant or biologic therapy [11/22; 50%]. The average number of patients evaluated per trial was 125.6 [range 23 to 365]. The mean duration of follow-up was 72.4 weeks [range 16 to 157 weeks]. The most common definition of clinical recurrence for RCT studies was symptomatic recurrence which included symptoms of active CD such as diarrhoea and abdominal pain [4/22; 18%], and the most common definition of endoscopic recurrence was defined as a Rutgeerts score ≥i2 [17/22; 77%]. The mean time of primary outcome evaluation [i.e., clinical recurrence] for RCTs was 57.7 weeks [range 12 to 157 weeks].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

| Baseline characteristic | RCT studies | Cohort studies |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of trials | 22 | 15 |

| Mean number of participants and rangeTotal number participants | 96.8 [22, 297]2148 | 125.6 [23, 365]1905 |

| Gender ratio [male: female] | 47:53 | 51:49 |

| Mean age of participants and range | 36.9 [32.3 to 47] | 38.4 [33.8 to 42.3] |

| Mean number of centres and range | 14.3 [1 to 104] | 5 [1 to 26] |

| Mean number of follow-up visits and range | 6.6 [2 to 12] | 7.8 [1 to 24] |

| % of studies with 2 treatment arms | 19/22 [86%] | 6/15 [40%] |

| Mean disease duration [years] prior to enrolment and range | 6.4 [2 to 9.5] | 7.4 [2.9 to 13.8] |

| Mean time of primary outcome evaluation [in weeks] and range | 57.7 [12 to 157] | 127.9 [52 to 352] |

| Mean duration of follow-up [in weeks] and range | 72.4 [16 to 157] | 162.3 [52 to 352] |

| Overall endoscopic recurrence rate | 1075/2081 [51.7%] | 1031/1792 [57.5%] |

| Overall clinical recurrence rate | 500/2012 [24.9%] | 572/1825 [31.3%] |

For cohort studies, the most common definition of clinical recurrence used was a Harvey‐Bradshaw Index score ≥8 [7/15; 47%], and the most common definition of endoscopic recurrence was a Rutgeerts score ≥i2 [12/15; 80%]. The mean time of primary outcome evaluation [i.e., clinical recurrence] for cohort studies was 127.9 weeks [range 52 to 352 weeks].

3.3. Stratified analysis of recurrence rates

For the 22 RCTs comprising 2148 participants, measures of association were evaluable in eight studies.8,21,31–33,35,37,39 For the 15 cohort studies comprising 1905 participants, measures of association were evaluable in 12 studies [eight of which were prospective and four were retrospective].41–50,52,54 Data for other clinically meaningful outcomes other than clinical recurrence [repeat surgery, hospitalisation, treatment escalation, and quality of life] were sparsely available and therefore we were unable to generate summary data for these parameters.

Tables 2 and 3 summarise the stratified recurrence rates for RCTs and cohort studies, respectively. Among the 302 patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence while participating in an RCT, a total of 101 [33.4%] also experienced clinical recurrence. Only four patients [1.2%] of the 105 who experienced clinical recurrence did not experience endoscopic recurrence. For cohort studies, among the 797 patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence, 425 [53.3%] also experienced clinical recurrence. Only 35 patients [5.2%] of the 460 patients who experienced clinical recurrence did not experience endoscopic recurrence.

Table 2.

Stratified recurrence rates for randomised controlled trial [RCT] studies.

| RCT Studies [N = 8] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical recurrence | No clinical recurrence | Total | |

| Endoscopic recurrence | 101 [33.4%] | 201 [66.6%] | 302 |

| No endoscopic recurrence | 4 [1.2%] | 323 [98.8%] | 327 |

| Total | 105 | 524 |

Odds ratio (OR) = (101/201)/(4/323) = 40.6; risk ratio (RR) = [101/(101+201)]/[4/(4+323)] = 27.3.

Table 3.

Stratified recurrence rates for cohort studies.

| Cohort studies [n = 12] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical recurrence | No clinical recurrence | Total | |

| Endoscopic recurrence | 425 [53.3%] | 372 [46.7%] | 797 |

| No endoscopic recurrence | 35 [5.2%] | 643 [94.8%] | 678 |

| Total | 460 | 1015 |

Odds ratio (OR) = (425/372)/(35/643) = 21; risk ratio (RR) = [425/(425+372)]/[35/(35+643)] = 10.3.

Tables 2 and 3 allow the calculation of ORs and RRs across all studies. For RCTs, the odds of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence was 40.6 [95% CI 14.7 to 111.9] times the odds of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence. The risk of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence was 27.3 [95% CI 10.2 to 73.4] times the risk of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence. For cohort studies, the odds of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence was 21 [95% CI 14.5 to 30.3] times the odds of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence. The risk of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence was 10.3 [95% CI 7.4 to 14.4] times the risk of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence. These estimates demonstrate a consistent and strong association between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence.

3.4. Pooled measures of association

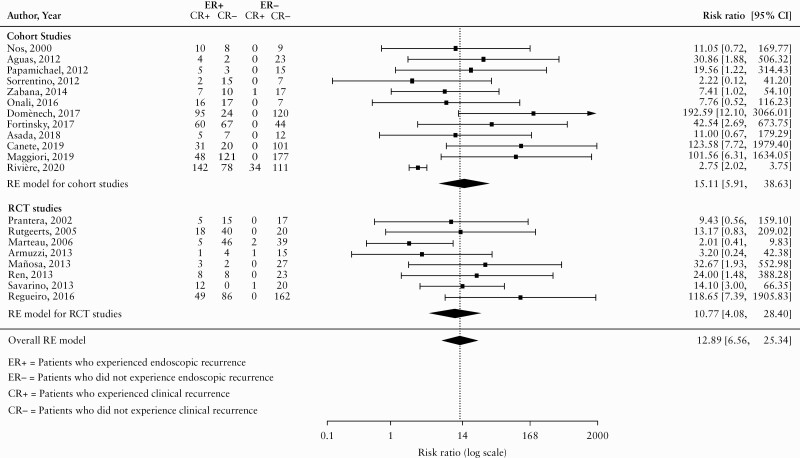

Due to the limited number of patients experiencing clinical recurrence and not endoscopic recurrence [in most studies the total was 0], an RR using a robust estimator for the error variance [known as a ‘sandwich estimator’]55 was used as our primary measure of association. Figure 2 displays the pooled RR estimates using a random-effects model. This model supports the presence of a strong association between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence. Specifically, the risk of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence was 12.89 [95% CI 6.56 to 25.34; I2 = 50.17%; see Figure 2] times the risk of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence. Separate RRs were calculated for cohort and RCT studies. For RCT studies, the risk of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence was 10.77 [95% CI 4.08 to 28.40; I2 = 28.16%; GRADE moderate certainty evidence] times the risk of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence. For cohort studies, the risk of clinical recurrence for patients who experienced endoscopic recurrence was 15.11 [95% CI 5.91 to 38.63; I2 = 54.89%; GRADE very low certainty evidence] times the risk of clinical recurrence for patients who did not experience endoscopic recurrence. The GRADE analysis and justification for ratings are reported in Supplementary Table 4, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online. Overall, we rated the certainty of evidence from RCTs as moderate due to high risk of bias. Evidence from cohort studies was initially upgraded one level to moderate, due to the very large increase in the risk of clinical recurrence that was observed in participants with endoscopic recurrence. The final rating for the certainty of evidence from cohort studies was low, due to the high risk of bias inherent in observational studies.

Figure 2.

Pooled risk ratio [RR].

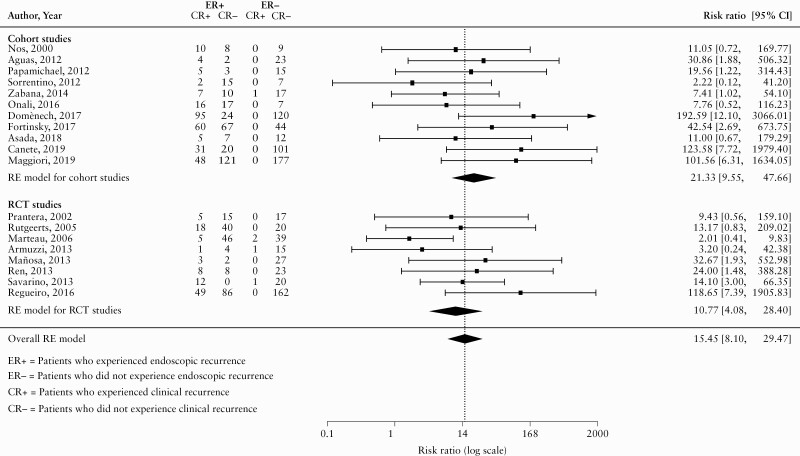

3.5. Sensitivity analysis

One study was identified an outlier.54Figure 3 displays the pooled RR after excluding this study. After removing the outlier, the RR increased from 12.89 [95% CI 6.56 to 25.34] to 15.45 [95% CI 8.10 to 29.47]. The outlier accounted for a substantial amount of the observed heterogeneity as the I2 statistic decreased from 50.17% to 20.7%. Separate RRs were calculated for cohort and RCT studies. For RCTs, the pooled RR was 10.77 [95% CI 4.08 to 28.40; I2 = 28.16%; GRADE moderate certainty evidence]. For cohort studies, the pooled RR was 21.33 [95% CI 9.55 to 47.66; I2 = 0%; GRADE low certainty evidence].

Figure 3.

Pooled risk ratio [RR]—sensitivity analysis.

3.6. Meta-regression

The results of the univariable meta-regression analysis of factors contributing to the association between clinical recurrence and endoscopic recurrence are reported in Supplementary Table 5, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online. None of the covariates investigated had a statistically significant impact on the association.

3.7. Subgroup analyses

Stratum-specific RRs are reported in Supplementary Table 6, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online. Statistically significant heterogeneity was observed in cohort studies [p = 0.001], retrospective studies [p <0.001], European studies [p = 0.002], studies without a placebo arm [p = 0.001], studies without blinding [p = 0.001], studies published after 2005 [p <0.001], studies with a disease duration >7 years [p = 0.001], and studies that used a Rutgeerts score >i2 as their definition of endoscopic recurrence [p = 0.001]. Significant heterogeneity was also observed in studies where less than 50% of the patients had received previous biologic therapy, had a previous surgery, or were current smokers at the time of the study [p = 0.002, p = 0.013, and p = 0.001, respectively]. Substantial statistically significant heterogeneity was observed in the overall pooled effect [I2 = 50.17%].

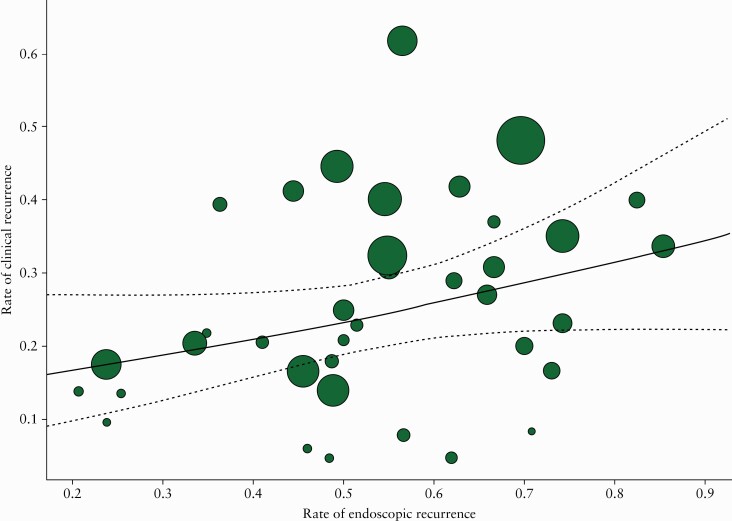

3.8. Relationship between the rate of clinical recurrence and the rate of endoscopic recurrence

Figure 4 displays a meta-analytic scatter plot of the rate of endoscopic recurrence [x-axis] versus the rate of clinical recurrence [y-axis]. The radius of each point was drawn proportional to the inverse of the standard error [i.e., larger/more precise studies are drawn larger]. The predicted average rate of clinical recurrence was also added to the plot [with associated 95% CIs]. The results from the meta-regression [Supplementary Table 7, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online] indicated that an increase in the rate of endoscopic recurrence was associated with a non-significant increase in the rate of clinical recurrence (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.35 [per 10% increase]; p = 0.091]. In particular, there was a 15% increase in the odds of clinical recurrence per 10% increase in the rate of endoscopic recurrence. The weighted and unweighted Spearman rank correlations coefficients were 0.51 and 0.64, respectively, indicating a ‘large’ association between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence.56

Figure 4.

Meta-analytical scatter plot of the rate of endoscopic recurrence [x-axis] vs the rate of clinical recurrence [y-axis].

4. Discussion

The results of this systematic review show a strong association between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence in postoperative CD. Based upon total stratified recurrence rates for endoscopic and clinical recurrence, we calculated odds and risk ratios of 40.6 [95% CI 14.7 to 111.9] and 27.3 [95% CI 10.2 to 73.4], respectively, for RCTs. For cohort studies, we calculated an OR of 21 [95% CI 14.5 to 30.3] and a RR of 10.3 [95% CI 7.4 to 14.4]. Further evidence of the strong association between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence was obtained by pooling the data from the two types of studies. Based on 19 studies [11 cohort studies and eight RCTs] conducted between 2000 and 2019, a pooled RR of 10.77 [95% CI 4.08 to 28.40; GRADE moderate certainty evidence] was calculated for RCTs, and a pooled RR of 21.33 [95% CI 9.55 to 47.66; GRADE low certainty evidence] was calculated for cohort studies. The strong association and the consistency between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence observed across multiple subgroups underscore the importance of endoscopic recurrence as a potential predictor of clinical recurrence.

To further evaluate the association between endoscopic and clinical recurrence, we evaluated the concordance between the two outcomes in RCTs of treatment based upon the notion that outcome concordance would be reflected in linear effect size estimates across studies. Indeed, a ‘large’ correlation was found using both unweighted and weighted Spearman correlation coefficients.56 An additional univariable meta-regression model was used to evaluate the effect of the endoscopic recurrence rate on the clinical recurrence rate. The model used the logit of the clinical recurrence rate as the outcome and the rate of endoscopic recurrence as a predictor variable. This meta-regression analysis indicated that an increase in the rate of endoscopic recurrence was associated with a non-significant increase in the rate of clinical recurrence. In particular, there was a 15% increase in the odds of clinical recurrence per 10% increase in the rate of endoscopic recurrence.

Some noteworthy observations can be made from the results of the meta-regression. It is interesting that despite the large RR of clinical recurrence with endoscopic recurrence, absolute rates remain in range 30–50%, suggesting that within the time frame of these studies, the majority of patients experienced endoscopic recurrence but not clinical recurrence. The presumption would be that with longer follow-up we would see endoscopic recurrence result in clinical recurrence, but the meta-regression did not actually support this, with no apparent effect of length of follow-up.

In our analysis, clinical recurrence without endoscopic recurrence was uncommon. We hypothesise that this may reflect the definition of clinical recurrence used in most studies, which most commonly defined recurrence using a composite of both patient-reported symptoms and other features, to confirm that these symptoms were related to CD rather than other causes of diarrhoea or abdominal pain. This mirrors clinical practice, where there is increasing recognition that potential confounding aetiologies of symptoms after surgery, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or bile acid diarrhoea, must be managed in addition to evaluation for recurrent CD.

We were unable to investigate the linearity of the risk of clinical recurrence based on the Rutgeerts score using meta-analysis and meta-regression, as only a single retrospective cohort study with no comparison group reported data by Rutgeerts score categories [i.e., 0, i1, i2, i3, i4].54 Rivière 2020 et al.54 reported clinical recurrence in 21 of 74 [28%] patients with a Rutgeerts score of i0, 13 of 37 [35%] with a Rutgeerts score of i1, 88 of 180 [49%] with a Rutgeerts score of i2, 27 of 42 [64%] with a Rutgeerts score of i3, and 27 of 32 [84%] with a Rutgeerts score of i4. Based upon these data, severe endoscopic recurrence [high Rutgeerts score] appears to convey greater risk of clinical recurrence. Additional studies on the linearity of the risk of clinical recurrence based on the Rutgeerts score are needed to confirm this observation.

Overall, these data suggest a causal relationship between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence in postoperative CD. Three criteria are generally considered as requirements for identifying a causal effect: empirical association, temporal priority, and non-spuriousness. In terms of empirical association, a strong and consistent association was observed between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence in both RCTs and cohort studies, using multiple statistical methods. It is well established that endoscopic recurrence in CD is often asymptomatic and precedes clinical recurrence at varying time intervals depending on the severity of the endoscopic lesions.1,2,5,57 We can be reasonably confident that the relationship between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence is non-spurious because we have randomised data that control for potential confounders, to support the strong association between these variables.

The AGA suggests the early use of prophylactic thiopurines and/or TNF antagonist therapy in patients who are at high risk for clinical recurrence. Some patients at lower risk of clinical recurrence may opt for close endoscopic monitoring.2 However, there are limited data to validate these risk factors, as reflected in our inability to assess this in meta-analysis and meta-regression. Although there were insufficient data to assess the risk of clinical recurrence when stratified by risk groups [i.e., high risk of recurrence versus low risk] using meta-analysis and meta-regression, data from the one included RCT that used a risk model provide valuable insight.7

De Cruz et al. [2016]7 compared active care [ileocolonoscopy at 6 months] with standard care in postoperative CD patients. All patients received metronidazole 400 mg twice daily for 3 months after surgery. Patients deemed to be at high risk of recurrence [i.e., one or more of the following: smoking, perforating disease including abscess, enteric fistula, free perforation, previous resection] received prophylaxis with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine, or adalimumab if intolerant to thiopurines. Low- and high-risk patients in the active care group who had endoscopic recurrence at 6 months stepped up to thiopurine and adalimumab therapy, respectively. The results using the risk model were conflicting. Active care appears to provide a benefit for endoscopic outcomes in high-risk patients compared with standard care [49.5% had endoscopic recurrence compared with 70.5%] and a benefit for clinical recurrence in low-risk patients compared with standard care [19.0% versus 37.5%]. The complex design of this trial, that compared alternative treatment algorithms with unproven therapies, makes definitive conclusions difficult. However, the results are consistent with the view that active treatment of endoscopic recurrence is associated with lower rates of clinical recurrence in both high- and low-risk patients and provides further support for the use of endoscopic recurrence as a primary outcome in RCTs of postoperative CD patients. Further studies assessing the risk of clinical recurrence when stratified by low- and high-risk groups would be of great interest and would allow for the validation of risk models in this population.

The primary strength of our study was the inclusion of all RCTs and cohort studies that reported on both endoscopic recurrence as measured by the Rutgeerts score, and clinical recurrence defined by symptom relapse. A very strong and consistent association was identified between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence, independent of study design. Indeed, the risk of clinical recurrence in patients with endoscopic recurrence was so large, we felt justified in elevating the certainty of the evidence derived from the cohort studies in the GRADE assessment.

One limitation of our study was the fact that there were insufficient data to assess the association between endoscopic recurrence and other clinically meaningful outcomes [e.g., repeat surgery, hospitalisation, escalation of therapy, and quality of life]. There were also insufficient data to assess the association between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence in different risk groups. We were unable to account for loss to follow-up in cohort studies. Ten out of 15 cohort studies did not explicitly report on loss to follow-up. Among the five cohort studies that did report on loss to follow-up, dropouts ranged from 0% to 65%. It is possible that those with endoscopic recurrence may have been followed more diligently and for longer than patients without endoscopic recurrence. There was also considerable heterogeneity in the definition of clinical recurrence. The most common definition of clinical recurrence in RCTs was symptomatic recurrence [4/22, 18%]. Other definitions of clinical recurrence were based on the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index [CDAI] or Harvey‐Bradshaw Index [HBI] or a combination [e.g., CDAI >200 and Rutgeerts score >i2]. Regardless of the definition that was used, all definitions of clinical recurrence included symptoms of active CD. Finally, we were unable to investigate the impact of the timing and indication for colonoscopy in cohort studies on subsequent clinical recurrence, because these data were often not reported. We recognise that the timing and indication for colonoscopy are highly variable, and likely to be dependent on clinical status [i.e., patients who develop symptoms are more likely to undergo endoscopic evaluation] as well as local guidelines.

In conclusion, this systematic review undertaken to explore the association between endoscopic recurrence and clinical recurrence in RCTs and cohort studies in the postoperative CD setting showed a strong association between endoscopic recurrence and subsequent clinical recurrence. Severe endoscopic recurrence [i.e., a high Rutgeerts score] appears to convey a greater risk of clinical recurrence; however, more data are required to confirm this observation. No defined concurrent risk factor appeared to be of relevance as a modifier of the outcome. Given that symptoms are a relatively unreliable measure of disease activity in the postoperative population, these findings provide support for using endoscopy as the primary outcome measure in controlled trials of postoperative CD therapy.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Alessandro Ble, Corporate R&D, Alfasigma S.p.A., Bologna, Italy.

Cecilia Renzulli, Corporate R&D, Alfasigma S.p.A., Bologna, Italy.

Fabio Cenci, Corporate R&D, Alfasigma S.p.A., Bologna, Italy.

Maria Grimaldi, Corporate R&D, Alfasigma S.p.A., Bologna, Italy.

Michelangelo Barone, Corporate R&D, Alfasigma S.p.A., Bologna, Italy.

Rocio Sedano, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada; Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

Joshua Chang, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada.

Tran M Nguyen, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada.

Malcolm Hogan, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada.

Guangyong Zou, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

John K MacDonald, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada.

Christopher Ma, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada; Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada.

William J Sandborn, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada; Division of Gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Brian G Feagan, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada; Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Western University, London, ON, Canada; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

Emilio Merlo Pich, Corporate R&D, Alfasigma S.p.A., Bologna, Italy.

Vipul Jairath, Alimentiv Inc. [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], London, ON, Canada; Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Western University, London, ON, Canada; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

Funding

No external funding for this work was received. WS was funded in part by the NIDDK-funded San Diego Digestive Diseases Research Center [P30 DK120515].

Conflict of Interest

AB is an employee of Alfasigma S.p.A. CR is an employee of Alfasigma S.p.A. FC is an employee of Alfasigma S.p.A. MG is an employee of Alfasigma S.p.A. MB is an employee of Alfasigma S.p.A. JC is an employee of Alimentiv [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials]. TMN is an employee of Alimentiv [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials]. MH is an employee of Alimentiv [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials]. GYZ is a part-time employee of Alimentiv [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials]. JKM is an employee of Alimentiv [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials]. CM has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AVIR Pharma, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, Mylan, Takeda, Pfizer, Roche, Alimentiv [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials]; speaker’s fees from AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, and Pfizer; research support from Pfizer. WJS has received research grants from Abbvie, Abivax, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Glaxo Smith Kline, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, Prometheus Biosciences, Seres Therapeutics, Shire, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma; consulting fees from Abbvie, Abivax, Admirx, Alfasigma, Alimentiv [previously Robarts Clinical Trials, owned by Alimentiv Health Trust], Alivio Therapeutics, Allakos, Amgen, Applied Molecular Transport, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bausch Health [Salix], Beigene, Bellatrix Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Cellularity, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, Escalier Biosciences, Equillium, Forbion, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Gossamer Bio, Immunic [Vital Therapies], Index Pharmaceuticals, Intact Therapeutics, Janssen, Kyverna Therapeutics, Landos Biopharma, Lilly, Oppilan Pharma, Otsuka, Pandion Therapeutics, Pfizer, Progenity, Prometheus Biosciences, Prometheus Laboratories, Protagonists Therapeutics, Provention Bio, Reistone Biopharma, Seres Therapeutics, Shanghai Pharma Biotherapeutics, Shire, Shoreline Biosciences, Sublimity Therapeutics, Surrozen, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, Tillotts Pharma, UCB, Vendata Biosciences, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences, Vivelix Pharmaceuticals, Vivreon Biosciences, Zealand Pharma; and stock or stock options from Allakos, BeiGene, Gossamer Bio, Oppilan Pharma, Prometheus Biosciences, Prometheus Laboratories Progenity, Shoreline Biosciences, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences, Vivreon Biosciences. Spouse: Iveric Bio, consultant, stock options; Progenity, stock; Oppilan Pharma, consultant, stock options; Prometheus Biosciences, employee, stock, stock options; Prometheus Laboratories, stock, stock options, consultant; Ventyx Biosciences—stock, stock options; Vimalan Biosciences, stock, stock options. BGF has received grant/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Atlantic Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Celltech, Genentech Inc/Hoffmann-La Roche, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline [GSK], Janssen Research & Development, Pfizer, Receptos/Celgene International, Sanofi, Santarus, Takeda Development Center Americas, Tillotts Pharma AG, and UCB; consulting fees from Abbott/AbbVie, Akebia Therapeutics, Allergan, Amgen, Applied Molecular Transport, Aptevo Therapeutics, Astra Zeneca, Atlantic Pharma, Avir Pharma, Biogen Idec, BioMx Israel, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Calypso Biotech, Celgene, Elan/Biogen, EnGene, Ferring Pharma, Roche/Genentech, Galapagos, GiCare Pharma, Gilead, Gossamer Pharma, GSK, Inception IBD, JnJ/Janssen, Kyowa Kakko Kirin, Lexicon, Lilly, Lycera BioTech, Merck, Mesoblast Pharma, Millennium, Nestle, Nextbiotix, Novonordisk, Pfizer, Prometheus Therapeutics and Diagnostics, Progenity, Protagonist, Receptos, Salix Pharma, Shire, Sienna Biologics, Sigmoid Pharma, Sterna Biologicals, Synergy Pharma, Takeda, Teva Pharma, TiGenix, Tillotts, UCB Pharma, Vertex Pharma, Vivelix Pharma, VHsquared, and Zyngenia; speakers’ bureau fees from Abbott/AbbVie, JnJ/Janssen, Lilly, Takeda, Tillotts, and UCB Pharma; is a scientific advisory board member for Abbott/AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Atlantic Pharma, Avaxia Biologics, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Centocor, Elan/Biogen, Galapagos, Genentech/Roche, JnJ/Janssen, Merck, Nestle, Novartis, Novonordisk, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories, Protagonist, Salix Pharma, Sterna Biologicals, Takeda, Teva, TiGenix, Tillotts Pharma AG, and UCB Pharma; and is the Senior Scientific Officer of Alimentiv. EMP is an employee of Alfasigma S.p.A. VJ has received has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Alimentiv Inc [formerly Robarts Clinical Trials], Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, GlaxoSmithKline, Genetech, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Mylan, Pendopharm, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Takeda, Topivert; speaker’s fees from Abbvie, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda.

Author Contributions

Concept and design of the study: AB, CR, FC, MG, MB, RS, JC, TMN, MH, GYZ, JKM, CM, WJS, BGF, EMP, VJ, Data acquisition and analysis: JC, MH, GYZ, JKM. Interpretation of data: AB, CR, FC, MG, MB, RS, JC, TMN, MH, GYZ, JKM, CM, WJS, BGF, EMP, VJ. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: AB, CR, FC, MG, MB, RS, JC, TMN, MH, GYZ, JKM, CM, WJS, BGF, EMP, VJ. Study supervision: BGF, EMP, VJ. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Regueiro M, Velayos F, Greer JB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the Management of Crohn’s Disease After Surgical Resection. Gastroenterology 2017;152:277–95.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nguyen GC, Loftus EV Jr, Hirano I, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, Sultan S; AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee . American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Management of Crohn’s Disease After Surgical Resection. Gastroenterology 2017;152:271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negrón ME, et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology 2013;145:996–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee YW, Lee KM, Chung WC, Paik CN, Sung HJ, Oh YS. Clinical and endoscopic recurrence after surgical resection in patients with Crohn’s disease. Intest Res 2014;12:117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1990;99:956–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buisson A, Chevaux JB, Allen PB, Bommelaer G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Review article: the natural history of postoperative Crohn’s disease recurrence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;35:625–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Hamilton AL, et al. Crohn’s disease management after intestinal resection: a randomised trial. Lancet 2015;385:1406–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Regueiro M, Feagan BG, Zou B, et al. ; PREVENT Study Group. Infliximab reduces endoscopic, but not clinical, recurrence of Crohn’s disease after ileocolonic resection. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1568–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vítek L. Bile acid malabsorption in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skouras T, Dodd S, Prasad Y, Rassam J, Morley N, Subramanian S. Brief report: length of ileal resection correlates with severity of bile acid malabsorption in Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2019;34:185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klaus J, Spaniol U, Adler G, Mason RA, Reinshagen M, von Tirpitz C C. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth mimicking acute flare as a pitfall in patients with Crohn’s disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2009;9:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sandborn WJ. How to avoid treating irritable bowel syndrome with biologic therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis 2009;27[Suppl 1]:80–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA [editors]. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6.1. [Updated September 2020.] www.Training.Cochrane.Org/handbook. Accessed 1 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:112–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Sultan S, et al. ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines: 9. Rating up the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1311–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Armuzzi A, Felice C, Papa A, et al. Prevention of postoperative recurrence with azathioprine or infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease: an open-label pilot study. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:e623–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bommelaer G, Laharie D, Nancey S, et al. ; POPCUR study group. Oral curcumin no more effective than placebo in preventing recurrence of Crohn’s disease after surgery in a randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1553–60.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Malchow H, et al. Interleukin 10 [Tenovil] in the prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Gut 2001;49:42–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Bruyn JR, Bossuyt P, Ferrante M, et al. ; Dutch-Belgian: The Effect of Vitamin D3 to Prevent Postoperative Relapse of Crohn’s Disease: A Placebo-controlled Randomized Trial Study Group. High-dose vitamin D does not prevent postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:1573–82.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Desreumaux P, Dewit O, Belaiche J, et al. Lactobacillus casei dn-114 001 strain in the prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: A randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2010;138[Suppl 1]: S616. [Google Scholar]

- 26. D’Haens GR, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, et al. Therapy of metronidazole with azathioprine to prevent postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a controlled randomized trial. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ferrante M, Papamichael K, Duricova D, et al. ; International Organization for Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Systematic versus endoscopy-driven treatment with azathioprine to prevent postoperative ileal Crohn’s disease recurrence. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hanauer SB, Korelitz BI, Rutgeerts P, et al. Postoperative maintenance of Crohn’s disease remission with 6-mercaptopurine, mesalamine, or placebo: a 2-year trial. Gastroenterology 2004;127:723–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hellers G, Cortot A, Jewell D, et al. Oral budesonide for prevention of postsurgical recurrence in Crohn’s disease. The IOIBD Budesonide Study Group. Gastroenterology 1999;116:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. López-Sanromán A, Vera-Mendoza I, Domènech E, et al. Adalimumab vs azathioprine in the prevention of postoperative Crohn’s disease recurrence. A GETECCU randomised trial. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:1293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mañosa M, Cabré E, Bernal I, et al. Addition of metronidazole to azathioprine for the prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1889–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marteau P, Lémann M, Seksik P, et al. Ineffectiveness of Lactobacillus johnsonii LA1 for prophylaxis of postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled GETAID trial. Gut 2006;55:842–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prantera C, Scribano ML, Falasco G, Andreoli A, Luzi C. Ineffectiveness of probiotics in preventing recurrence after curative resection for Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial with Lactobacillus GG. Gut 2002;51:405–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reinisch W, Angelberger S, Petritsch W, et al. ; International AZT-2 Study Group. Azathioprine versus mesalazine for prevention of postoperative clinical recurrence in patients with Crohn’s disease with endoscopic recurrence: efficacy and safety results of a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, multicentre trial. Gut 2010;59:752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ren J, Wu X, Liao N, et al. Prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: Tripterygium wilfordii polyglycoside versus mesalazine. J Int Med Res 2013;41:176–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rutgeerts P, Hiele M, Geboes K, et al. Controlled trial of metronidazole treatment for prevention of Crohn’s recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology 1995;108:1617–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, et al. Ornidazole for prophylaxis of postoperative Crohn’s disease recurrence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2005;128:856–61.£ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Satsangi J, Kennedy NA, Mowat C, et al. Efficacy and mechanism evaluation. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial to assess mercaptopurine versus placebo to prevent or delay recurrence of Crohn’s disease following surgical resection . Southampton, UK: NIHR Journals Library,2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Savarino E, Bodini G, Dulbecco P, et al. Adalimumab is more effective than azathioprine and mesalamine at preventing postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1731–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scapa E, Fliss-Isakov N, Tulchinsky H, et al. Early initiation of adalimumab significantly diminishes endoscopic postoperative Crohn’s disease recurrence, and is superior to immunomodulatory therapy, regardless of risk stratification. A randomized, controlled study. United Eur Gastroent J 2018;6:A458. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aguas M, Bastida G, Cerrillo E, et al. Adalimumab in prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease in high-risk patients. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:4391–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Asada T, Nakayama G, Tanaka C, et al. Postoperative adalimumab maintenance therapy for Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease: a single-center, single-arm phase II trial [CCOG-1107 study]. Surg Today 2018;48:609–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maggiori L, Brouquet A, Zerbib P, et al. ; GETAID chirurgie group. Penetrating Crohn disease is not associated with a higher risk of recurrence after surgery: a prospective nationwide cohort conducted by the Getaid Chirurgie Group. Ann Surg 2019;270:827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nos P, Hinojosa J, Aguilera V, et al. [Azathioprine and 5-ASA in the prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease]. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;23:374–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Onali S, Calabrese E, Petruzziello C, et al. Postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: A prospective study at 5 years. Dig Liver Dis 2016;48:489–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Papamichael K, Archavlis E, Lariou C, Mantzaris GJ. Adalimumab for the prevention and/or treatment of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a prospective, two-year, single centre, pilot study. J Crohns Colitis 2012;6:924–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sorrentino D, Terrosu G, Paviotti A, et al. Early diagnosis and treatment of postoperative endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease: partial benefit by infliximab – a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:1341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zabana Y, Mañosa M, Cabré E, et al. Addition of mesalazine for subclinical post-surgical endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease despite preventive thiopurine therapy: A case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:1413–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cañete F, Mañosa M, Casanova MJ, et al. ; ENEIDA registry by GETECCU. Adalimumab or infliximab for the prevention of early postoperative recurrence of Crohn disease: results from the ENEIDA Registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:1862–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Domènech E, Garcia V, Iborra M, et al. Incidence and management of recurrence in patients with Crohn’s disease who have undergone intestinal resection: The Practicrohn Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:1840–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fiorino G, Bonifacio C, Allocca M, et al. Clinical utility of the Lemann Index and Rutgeerts Score to predict postoperative course of Crohn’s disease: A retrospective, single-centre cohort study. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9[Suppl 1]:S193. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fortinsky KJ, Kevans D, Qiang J, et al. Rates and predictors of endoscopic and clinical recurrence after primary ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hammoudi N, Cazals-Hatem D, Auzolle C, et al. ; REMIND Study Group Investigators. Association Between Microscopic Lesions at Ileal Resection Margin and Recurrence After Surgery in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:141–149.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rivière P, Vermeire S, Irles-Depe M, et al. Rates of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease and effects of immunosuppressive and biologic therapies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:713‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zou GY, Donner A. Extension of the modified Poisson regression model to prospective studies with correlated binary data. Stat Methods Med Res 2013;22:661–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Kerremans R, Coenegrachts JL, Coremans G. Natural history of recurrent Crohn’s disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgery. Gut 1984;25:665–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.