Abstract

The OneFlorida Data Trust is a centralized research patient data repository created and managed by the OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium (“OneFlorida”). It comprises structured electronic health record (EHR), administrative claims, tumor registry, death, and other data on 17.2 million individuals who received healthcare in Florida between January 2012 and the present. Ten healthcare systems in Miami, Orlando, Tampa, Jacksonville, Tallahassee, Gainesville, and rural areas of Florida contribute EHR data, covering the major metropolitan regions in Florida. Deduplication of patients is accomplished via privacy-preserving entity resolution (precision 0.97–0.99, recall 0.75), thereby linking patients’ EHR, claims, and death data. Another unique feature is the establishment of mother-baby relationships via Florida vital statistics data. Research usage has been significant, including major studies launched in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (“PCORnet”), where OneFlorida is 1 of 9 clinical research networks. The Data Trust’s robust, centralized, statewide data are a valuable and relatively unique research resource.

Keywords: Clinical Data Research Network, data warehouse, data quality, data management, data analysis

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 15 years, research reuse of electronic health record (EHR) data has become commonplace and occurs increasingly at scale. Key drivers of this trend are the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)1,2 and the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).3 More recently, the growth of the Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) program4 and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) efforts to promote the generation of real-world evidence from real-world data5,6 have accelerated the trend further. These initiatives echo the much longer history of repurposing of large, administrative claims datasets for research.

Within the CTSA program and PCORnet, research usage of EHR data extends beyond retrospective, observational analysis. Besides cohort detection, researchers collect study data elements from EHRs on outcomes, interventions, adverse events, and factors associated with outcomes. The goal is to enable prospective translational studies that include clinical and pragmatic trials and implementation science.

The OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium is currently one of the 9 clinical research networks (CRNs) that, along with a coordinating center, constitute PCORnet 2.0. As a CRN, OneFlorida is unique in its statewide scope, covering all the major metropolitan regions in the nation’s third most populous state. In addition, the Florida of today resembles the United States of tomorrow: older and more diverse.

The OneFlorida Data Trust is the research patient data repository established and operated by OneFlorida. At its core, it includes EHR data from 10 health systems in Miami, Orlando, Tampa, Jacksonville, Tallahassee, and Gainesville linked to statewide claims data from Medicaid and Medicare. We report here on the design and composition of the Data Trust, our methods for building it, toolsets we employ for building and using it, examples of research usage, and key lessons learned.

ESTABLISHMENT AND GROWTH OF ONEFLORIDA

We have previously described OneFlorida and its history.7 Briefly, OneFlorida began as a partnership between UF and Florida State University funded through an administrative supplement to UF’s CTSA. The addition of the University of Miami and state funding through Florida’s James and Esther King foundation built additional infrastructure focused on cancer research. OneFlorida became a part of PCORnet in 2015 in phase 2 as one of 2 new networks.

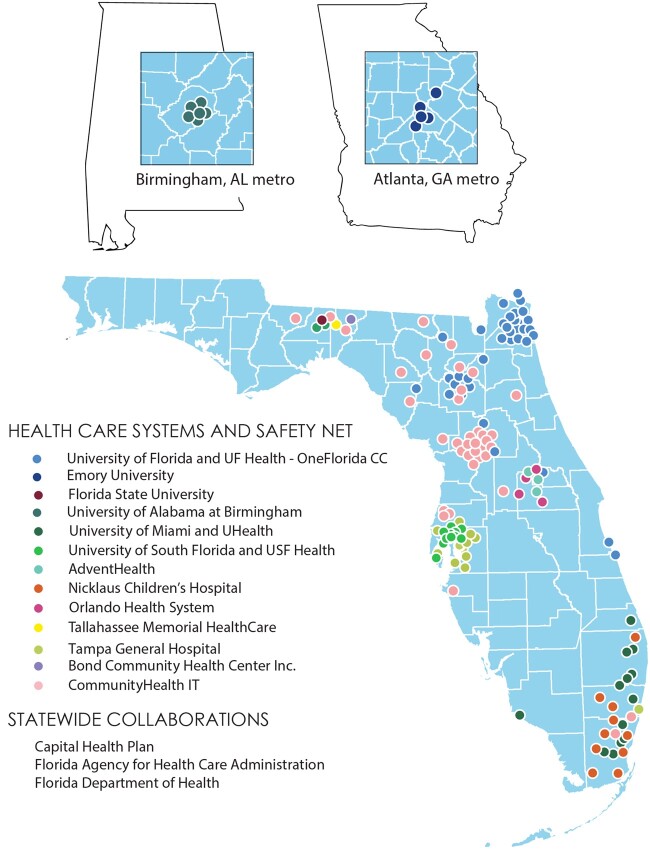

Since then, OneFlorida has grown to include 2 additional health system partners (Figure 1). Importantly, the addition of University of South Florida (USF) and Tampa General Hospital (TGH) in 2019 added coverage of Florida’s third-largest city, Tampa. In addition, at that time, some OneFlorida partners had not yet begun contributing data, who are now routinely submitting data that meet PCORnet standards. They include Bond Community Health Center, Inc. (CHC) and a practice in central Florida facilitated by CommunityHealth IT. Bond CHC is a federally qualified health center (FQHC) in Tallahassee, and CommunityHealth IT is a 501(c)(6) that helps health systems and safety net medical facilities adopt health information technology. CommunityHealth IT will add additional practices from its consortium on an ongoing basis. OneFlorida is committed to the inclusion of safety net providers, such as FQHCs. These entities serve unique populations that typically experience gross health inequities. By ensuring their inclusion, we ensure that data used for research and for example, construction of artificial intelligence models, are less biased and do not help to perpetuate health inequities. By engaging these providers in prospective trials, we more directly reduce disparities in research results generated in OneFlorida. Further, as Florida is geographically diverse with mixed rural versus urban areas and is rapidly becoming a majority-minority state, the real-world data of unselected populations from the OneFlorida network provide a golden opportunity for health disparity research, especially research that focuses on racial and ethnic minorities and geographic disparities.

Figure 1.

Map of contributing partners to the OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium, where each color represents a healthcare partner organization and each dot of that color represents a physical location operated by that organization, such as a clinic or hospital.

THE ONEFLORIDA DATA TRUST

A key differentiator of the OneFlorida Data Trust is that it is centralized: all partners contribute data to a single, secure data warehouse managed by the OneFlorida Coordinating Center (OFCC) at the University of Florida. Our key motivation for this approach was cost-effectiveness and efficiency of the network: many OneFlorida partners did not have existing research infrastructure on which to build an independent PCORnet data mart. Nor were they as experienced with the core data standards used such as LOINC, RxNorm, and the PCORnet Common Data Model (CDM).

Thus, a centralized model at the OFCC enabled significant cost-efficiencies: we estimate ∼$183K/year/partner for a centralized versus ∼$2.0M/year/partner for federated approach, using as estimates our own costs for personnel and technology infrastructure (see Supplemental Material for our methods and more detailed results). Academic centers typically have distributed these costs among several sources (especially a CTSA) that are unavailable at nonacademic partners. Because a common approach across all OneFlorida partners was also a cost-saving imperative, academic partners adopted the centralized model too.

Data types and sources

In total, the Data Trust houses data on 17.2 million unique individuals dating from January 2012 through March 2021 (Table 1). It includes EHR data, claims data, and additional data that we discuss next. We estimate that our partners in Florida serve 40–50% of Florida’s population. In 2019 and 2020, 5.5 million and 5.4 million unique patients had an encounter at one of our partners’ facilities, respectively. Across both 2019 and 2020, the total was 7.4 million. Even in a 2-year window, it is unlikely that every person in a population visits a healthcare provider, so the true 1- and 2-year denominators are unknown but certainly less than the total Florida population.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of OneFlorida compared to Florida and the United States overall

| Population | OneFlorida | Florida | United States |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | N = 17 193 585 | N = 21 477 737 | N = 328 239 523 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 45.2% (7 768 107) | 48.9% | 49.2% |

| Female | 54.7% (9 410 081) | 51.1% | 50.8% |

| Unknown | 0.09% (15 397) | ||

| Age | |||

| <18 years | 27% (4 642 783) | 19.7% | 22.2% |

| 18–64 years | 54% (9 284 021) | 59.4% | 61.3% |

| 65+ years | 18.99% (3 264 282) | 20.9% | 16.5% |

| Unknown | 0.01% (2499) | ||

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.2% (33 043) | 0.3% | 0.9% |

| Asian | 1.4% (239 141) | 2.8% | 5.7% |

| Black | 18% (3 092 909) | 16.0% | 12.8% |

| White | 45.9% (7 897 865) | 74.5% | 72.0% |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.1% (10 480) | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Other | 23.2% (3 993 438) | 3.4% | 5.0% |

| Unknown | 11.2% (1 926 709) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 23% (4 029 625) | 26.4% | 18.4% |

Notes: OneFlorida numbers are cumulative since 2012, whereas Florida and US numbers are current state. The high percentages of other and unknown in OneFlorida are due to data limitations that reflect a suboptimal state of the art in collecting these data, driven by basic compliance with federal data standards as the primary consideration.

EHR data

The chief data requirement of PCORnet CRNs is to house EHR data for unselected patient populations from each healthcare system in the network. Ten OneFlorida providers contribute EHR data (Figure 1), populating all the EHR-based tables in the PCORnet CDM, including diagnoses, procedures, observations (including vital signs), prescriptions, laboratory tests, and immunizations. In total, 9.9 million patients have EHR data. Partners refresh EHR data no less frequently than quarterly. Given typical billing cycles, the data lag 30–90 days behind the date of submission.

Claims data

Since its inception, the Data Trust has housed complete, statewide Medicaid data through a partnership with the Florida Agency for Healthcare Administration (AHCA). We subsequently added Medicare data for the dual-eligible (Medicare/Medicaid) population. Capital Health Plan—a health maintenance organization with 135 000 members and 3 health centers—contributes claims data and laboratory test results for patients cared for at Tallahassee Memorial Healthcare (TMH). For individual studies, we can link the entire Medicare population at each participating partner. In partnership with commercial payers, we also link commercial claims data to the entire Data Trust for individual studies. In total, 9 million patients have claims data. As we discuss below, our entity resolution processes have linked patients across sources and as a result, 1.7 million patients have both EHR and claims data.

Death data

Each healthcare partner includes information about the deaths of patients occurring within their institutions. In 2020, OneFlorida purchased and linked a commercial death dataset from Datavant, fulfilling one of OneFlorida researchers’ most common requests for additional data. We refresh death data monthly with updates from Datavant.

Tumor registry data

UF Health, Orlando Health, and TMH submit to the Data Trust an Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) limited data set (LDS) copy of the data they submit to the state tumor registry, the Florida Cancer Data System, following the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) data standards. Currently, the Data Trust holds tumor information for 87 179 patients with cancer, which includes detailed tumor characteristics (eg, tumor size and staging information), treatment information (eg, surgery, systemic therapy, immunotherapy, etc.), genetic markers (eg, HER2 status) among much other information that are important to cancer research.

Other data sources including publicly available third-party data

We have integrated American Community Survey data—and deprivation indexes derived from them—by linking patients’ home location to census tracts, ZIP codes, and counties in American Community Survey. More recently, we established an external exposome database with over 5500 variables from the natural (eg, air pollution), built (eg, walkability), and social (eg, housing) environment derived from well-validated, public data sources.8 We can provision patient-level OneFlorida data linked to environmental exposures through residential history. For ∼70% of patients in the Data Trust, we have 9-digit home ZIP, which enables linking to census tract level. For certain studies, we have also integrated OneFlorida data with Florida birth certificates and fetal death certificates data, through which a mother-baby relationship can be established. This capability enables linking a mother’s data (EHR, claims, etc.) to her baby’s data (EHR, claims, etc.) to study the effects of maternal health on child health outcomes. The Data Trust houses mother-baby birth, death, and prenatal screening data for all births.

Security, privacy, and regulatory framework

With the adoption of a centralized model, OneFlorida chose to make the Data Trust a HIPAA LDS, primarily motivated by partner concerns for patient privacy and by simplifying regulatory compliance. Being an LDS means only that the Data Trust excludes 16 of 18 categories of identifiers under HIPAA. What remains are dates of service, birth, and death and geographic indicators at resolutions smaller than a state.

From a regulatory perspective, an LDS requires only a data-use agreement (DUA) between the UF and each data provider, avoiding the need for Business Associate Agreements. Each partner additionally signs a memorandum of understanding with UF that expresses the intent of both parties to jointly conduct research. The DUA requires that the healthcare partner submit EHR data per PCORnet requirements, including the addition of new data as the PCORnet CDM expands or as new OneFlorida priorities arise. We also have a DUA with AHCA that enables the inclusion of the Medicaid and Medicare data and a DUA with the Florida Department of Health (FLDOH) for birth certificate and fetal death data.

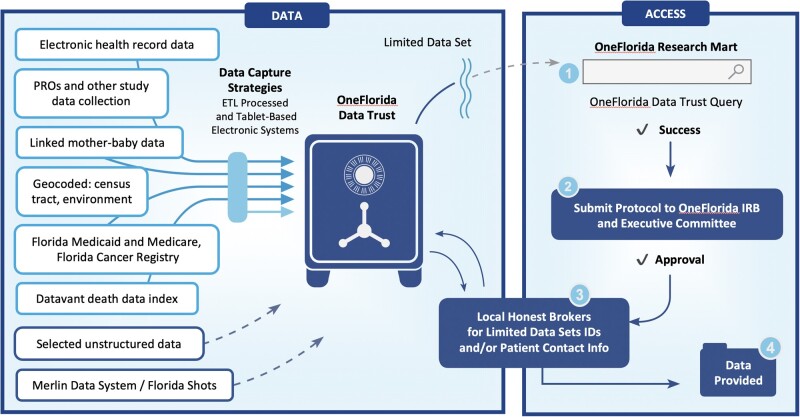

The Data Trust is approved as a UF “data bank” type Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol. Because an HIPAA LDS is still protected health information, the IRB requires periodic, extensive information technology security reviews to ensure that we provide strong, state-of-the-art controls and safeguards of the data. The OneFlorida Executive Committee serves as the oversight board and monitoring committee under the IRB, reviewing and reporting all Data Trust activity quarterly to the IRB. The Data Trust IRB permits patient re-identification through honest brokers (Figure 2). Each partner has staff who are not members of any research team and can re-identify patients at their sites for approved research protocols. Such re-identification enables participant recruitment for prospective studies and trials. Because each partner controls re-identification at its sites, no researcher can contact its patients without its involvement, which was also a key concern of OneFlorida partners generally.

Figure 2.

Overall scheme of the Data Trust, showing data sources flowing into the Data Trust, and research workflows for using the data (solid lines represent ongoing routine data flows and dashed lines represent data sources under development, but nonetheless used for specific studies in the past). A robust honest broker system enables patient re-identification for IRB approved protocols to enable participant recruitment. PROs: Patient-Reported Outcomes; ETL: extract, transform, and load; IDs: identifiers; IRB: Institutional Review Board.

Entity resolution and record linkage

The fact that the Data Trust is an HIPAA LDS presented an added challenge to linking patients’ data across multiple data sources. We implemented a hash-based privacy-preserving entity resolution (PPER, or record linkage) solution. Initially, we deployed our in-house solution—OneFl Deduper—across all OneFlorida partners and evaluated its performance—that is, precision 0.97–0.99 and recall 0.75.9 For several studies, we used Deduper to link other data sources such as mother-baby relationships established from birth certificates. In late 2019, PCORnet began the process of identifying a common PPER solution and selected a commercial, hash-based PPER solution from Datavant. We are in the process of implementing Datavant at all partners. However, we continue to operate both solutions in parallel, and we still carry out entity resolution via Deduper so its performance is applicable to our current entity resolution results.

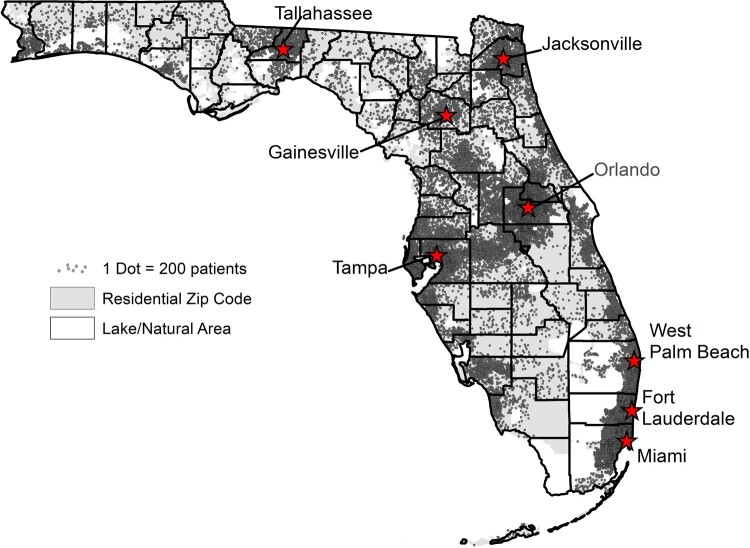

As of April 2021, through our existing PPER process with OneFl Deduper, we deduplicated 2.4 million patient records for 2.2 million patients and linked 1.7 million (10%) patients’ EHR data to their claims data. In total, 9 million patients have claims data and 9.9 million have EHR data. Given that our PPER has an estimated recall of 75–85%, the true number of unique patients is likely to be slightly lower than 17.2 million. Our geographical coverage of unique individuals across the state of Florida mirrors the population density of the state (Figure 3). The Data Trust nevertheless covers all 67 counties in Florida and most rural areas have substantial representation.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of coverage of Florida by the OneFlorida Data Trust. The figure was generated from OneFlorida patients seen during 2017–2021, totaling 9.2 million patients thus far into 2021. 1 dot = 100 patients.

We also implemented additional entity resolution processes to improve data quality. For example, when a particular patient has records from multiple partners, we source their demographic data from the partner with the most recent encounter. However, we overwrite fields that have “other” and “unknown” values with known values when they are present in other partners’ older data. For example, a recent race value of “unknown” from partner A would be overwritten with an older value of “black” from partner B. Excluding unknown values, among the 2.2 million linked patient record pairs, 0.17% of pairs have conflicting sex values, 2.6% have multiple race values (which might or might not conflict depending on whether the individuals in question are multiracial), and 3.7% have conflicting ethnicity values (ie, Hispanic vs not Hispanic).

We note that the state of the art among our partners is to collect limited gender, race, and ethnicity data, the latter 2 as defined by Office of Management and Budget (OMB) standards which are basic and simplistic. In particular, claims data use the single-question format to capture both race and ethnicity, leaving one or the other unknown. For example, a response of Black does not capture ethnicity. A response of Hispanic does not capture race. This situation leads to the high percentages of “unknown” and “other” values in Table 1. Sadly, we believe this situation results from the lack of incentives in the healthcare industry at large to capture richer gender, race, and ethnicity data. We have confronted this problem through, for example, the development of transgender and gender nonconforming computable phenotypes that leverage data besides the demographics table in the PCORnet CDM.10

Data quality

We have taken multiple approaches to ensuring data quality in the Data Trust. The most intensive quality assurance process in terms of the number of checks, running time, comprehensiveness across PCORnet CDM tables, and the addition of new checks over time is the PCORnet empirical data characterization (EDC) process. PCORnet EDC occurs quarterly, with a mandate to refresh all EHR data each time. EDC includes mandatory checks for certification for use in PCORnet studies and also flags serious issues. Datamarts are judged based on the numbers of serious issues outstanding. Despite the Data Trust being centralized, PCORnet treats each OneFlorida source (including Medicaid) as a separate PCORnet data mart, each of which must pass EDC on its own. OFCC staff perform EDC for each data mart and work with partners to address issues identified.

To further improve our data quality practices, we synthesized data quality dimensions and assessment methods for real-world data, especially EHRs, through a systematic scoping review and then assessed gaps in existing PCORnet EDC processes.11 Guided by this review, we further advanced data quality assessment within OneFlorida, especially providing more comprehensive, study-specific data quality checks. For example, our study-specific data quality checks often focused on various aspects of plausibility, concordance, consistence, and relevance, while the PCORnet EDC merely focus on conformance and completeness. Further, as part of the OneFlorida project intake process, a dedicated data team with informatics faculty and data analysts iteratively works with the investigators to address various data issues including data quality issues.

Queries and data analytics

A key function of the OFCC is to provide query and data extraction services. Researchers use the i2b2 self-service query tool for many preparation-to-research queries, including cohort identification and counts. The OneFlorida i2b2 instance includes one large project with all linked data comprising over 12 billion facts, as well as 11 partner-specific projects (10 health systems plus Medicaid) that when linked comprise the larger dataset. Each partner may query the combined data project and its own project, but not any other partner’s project. The individual partner-based projects do not include additional data not also included in the large project. Data analysts write and curate more complex queries and conduct study data extraction. Often, an informatics faculty liaison from the OFCC is involved in the query fulfillment process, providing expertise and consultation on best practices for using real-world data in research. The centralized model has enabled the OFCC to manage all query requests and responses for PCORnet studies. We have not only fulfilled the needs of PCORnet and OneFlorida studies but also conducted novel informatics research advancing the field (eg, developing and applying novel distributed learning algorithms and trial simulations using real-world data from the OneFlorida network).12–15

Approach to findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability

We deposit metadata about each PCORnet-certified, quarterly refresh of the Data Trust into DataCite Commons, including title, creators, various dates, and a description. DataCite Commons assigns a digital object identifier (DOI) to each metadata submission,16–20 enabling us to meet a key findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) data metric of assigning the metadata a unique, resolvable identifier. We provide these DOIs to investigators so they can cite the Data Trust in their work. Although these efforts address the findability of Data Trust data and begin to guide reuse by clearly identifying successive versions of the Data Trust as utilized in various studies, they represent only our initial efforts toward FAIR. Because FAIR principles also apply to metadata, we note that our metadata adhere to FAIR principles to the extent that the DataCite Commons itself supports them.

RESEARCH USAGE

Several retrospective studies have utilized the Data Trust. Examples include studies on hypertension,21 obesity,22,23 sickle cell disease,24 stillbirth,25 hepatitis C,26 opioid use disorder,15 and adults with multiple chronic conditions.27 Researchers have also used the Data Trust to develop computable phenotypes, including resistant hypertension, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and transgender and gender nonconforming individuals.10,28,29 In addition, the Data Trust has played key roles in several, large studies carried out in PCORnet.30–34 Also, to confront the COVID-19 pandemic, PCORnet partnered with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on a COVID-19 healthcare data initiative,35 with 5 OneFlorida partners participating. OneFlorida and its Data Trust were essential to the formation of the South East Enrollment Center (SEEC) in the All of Us Research Program (AoURP),36 which includes the University of Miami, University of Florida, Morehouse School of Medicine, and Emory University. SEEC has to date enrolled over 20 000 AoURP participants, and the OFCC has delivered EHR data for a significant majority.

EMERGING AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The expansion of OneFlorida to OneFlorida+ occurred in 2020 with the additions of Emory University in Georgia and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The result is an expansion of the network and research infrastructure from Florida to the southeastern United States. The vision is to address the health needs and health disparities of the entire expanded region. The new partners already participate on the OneFlorida+ Executive Committee, and we currently are adding their data to the Data Trust. OneFlorida+ has applied for funding for these partners, as well as for USF/TGH, to become official PCORnet 3.0 partners. As we add healthcare organizations managed by CommunityHealth IT, we will prioritize safety net providers such as FQHCs. Discussions are ongoing with key stakeholders about linking the Data Trust to additional statewide datasets, such as the Florida immunization registry, emergency medical services data, and the Merlin case reporting system of the FLDOH (dashed lines in Figure 2).37

SUMMARY/CONCLUSION

The OneFlorida Data Trust is a key component of OneFlorida’s statewide research infrastructure. It has grown considerably over time, to include new partners, new sources and types of data, and the addition of third-party data sets. It serves as a robust research resource, including but not limited to translational, comparative effectiveness, and informatics research.

In keeping with OneFlorida’s mission to translate research results into practice across the spectrum, it includes nonacademic community health systems and safety net providers as partners. The inclusion of these entities, plus patient privacy and regulatory concerns, drove the development of a centralized model of the Data Trust. The centralized model has provided substantial efficiencies in building and operating it, including querying and analyzing the data.

Although the Data Trust is not the first or largest significant linkage of EHR and claims data, it remains among the largest—and one of the most comprehensive at a statewide scale.

FUNDING

This work was supported by awards UL1TR000064, UL1TR001427, and UL1TR002736 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS); awards CDRN-1501-26692, RI-CRN-2020-005, and GEN-1607-35623 from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); award 4KB16 from the FLDOH’s James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program; award AGR DTD 02-17-2021 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); and contract #1239 from the People-Centered Research Foundation (PCRF). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCATS, PCORI, FLDOH, CDC, or PCRF.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author WRH drafted the initial manuscript with contributions of sections from authors JB, LM, SW, and AL. Authors TR, OC, PSR, RZE, and DN provided significant input and review in describing the overall goals of OneFlorida, the issues of health equity, issues of real-world data and real-world evidence, and the agreements, structure, history, and partnership of OneFlorida. Authors GL, CH, TM, SW, and AL provided significant input and review on the technical and infrastructure aspects of the Data Trust, including data content, refreshes, and query and analytics. Author JH generated Figure 3 and provided significant input into the section describing Census data and its use in calculating deprivation indexes. All authors reviewed, edited, and commented on the manuscript and approved its final form.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge all the individuals working at all our partner organizations who make OneFlorida and the Data Trust possible. They would also like to thank Mahmoud Enani and Erik Schmidt for their contributions to the analysis provided in the Supplementary Material. They would also like to thank Joe Selby for his vision and leadership in creating the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet), as well as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Board of Governors for their bedrock support and confidence in PCORnet and its Clinical Research Networks and Coordination Center.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The OneFlorida Data Trust is available to investigators for research purposes through the formal policies and procedures established by the OneFlorida Executive Committee. The identifiers of sequential versions of the Data Trust are 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V1, 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V2, 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V3, 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V4, and 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V5. The data used to calculate the cost comparisons are provided in the Supplementary Material.

REFERENCES

- 1. Obeid JS, Tarczy-Hornoch P, Harris PA, et al. Sustainability considerations for clinical and translational research informatics infrastructure. J Clin Trans Sci 2018; 2 (5): 267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Campion TR, Craven CK, Dorr DA, et al. Understanding enterprise data warehouses to support clinical and translational research. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27 (9): 1352–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fleurence RL, Curtis LH, Califf RM, et al. Launching PCORnet, a national patient-centered clinical research network. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014; 21 (4): 578–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hripcsak G, Duke JD, Shah NH, et al. Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI): opportunities for observational researchers. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015; 216: 574–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Dal Pan GJ, et al. Real-world evidence—what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med 2016; 375 (23): 2293–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Use of Electronic Health Record Data in Clinical Investigations Guidance for Industry. US Food and Drug Administration; 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/use-electronic-health-record-data-clinical-investigations-guidance-industry Accessed June 26, 2021.

- 7. Shenkman E, Hurt M, Hogan W, et al. OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium: linking a Clinical and Translational Science Institute with a community-based distributive medical education model. Acad Med 2018; 93 (3): 451–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang H, Hu H, Diller M, et al. Semantic standards of external exposome data. Environ Res 2021; 197: 111185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bian J, Loiacono A, Sura A, et al. Implementing a hash-based privacy-preserving record linkage tool in the OneFlorida clinical research network. JAMIA Open 2019; 2 (4): 562–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo Y, He X, Lyu T, et al. Developing and validating a computable phenotype for the identification of transgender and gender nonconforming individuals and subgroups. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2020; 2020: 514–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bian J, Lyu T, Loiacono A, et al. Assessing the practice of data quality evaluation in a national Clinical Data Research Network through a systematic scoping review in the era of real-world data. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27 (12): 1999–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duan R, Luo C, Schuemie MJ, et al. Learning from local to global: an efficient distributed algorithm for modeling time-to-event data. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27 (7): 1028–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duan R, Chen Z, Tong J, et al. Leverage real-world longitudinal data in large clinical research networks for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia (ADRD). AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2020; 2020: 393–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Z, Zhang H, Guo Y, et al. Exploring the feasibility of using real-world data from a large Clinical Data Research Network to simulate clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease. NPJ Digit Med 2021; 4: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tong J, Chen Z, Duan R, et al. Identifying clinical risk factors for opioid use disorder using a distributed algorithm to combine real-world data from a large Clinical Data Research Network. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2020; 2020: 1220–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weinbrenner D, Hunter C, Kidder B, et al. OneFlorida Certified Database 04/29/2020. 2020. doi: 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V1. https://figshare.com/articles/OneFlorida_Certified_Database_04_29_2020/8063567/1 Accessed June 27, 2021.

- 17. Weinbrenner D, Hunter C, Kidder B, et al. OneFlorida Certified Database 07/27/2020. 2020. doi: 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V2. https://figshare.com/articles/online_resource/OneFlorida_Certified_Database_04_29_2020/8063567/2 Accessed June 27, 2021.

- 18. Weinbrenner D, Hunter C, Kidder B, et al. OneFlorida Certified Database 11/13/2020. 2020. doi: 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V3. https://figshare.com/articles/online_resource/OneFlorida_Certified_Database_04_29_2020/8063567/3 Accessed June 27, 2021.

- 19. Weinbrenner D, Hunter C, Kidder B, et al. OneFlorida Certified Database 3/8/2021. 2021, doi: 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V4. https://figshare.com/articles/online_resource/OneFlorida_Certified_Database_04_29_2020/8063567/4 Accessed June 27, 2021.

- 20. Weinbrenner D, Hunter C, Kidder B, et al. OneFlorida Certified Database 05/20/2021. 2021, doi: 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567. 10.6084/m9.figshare.8063567 Accessed June 27, 2021. [DOI]

- 21. Smith SM, McAuliffe K, Hall JM, et al. Hypertension in Florida: data from the OneFlorida Clinical Data Research Network. Prev Chronic Dis 2018; 15: E27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Filipp SL, Cardel M, Hall J, et al. Characterization of adult obesity in Florida using the OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium. Obes Sci Pract 2018; 4 (4): 308–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lemas DJ, Cardel MI, Filipp SL, et al. Objectively measured pediatric obesity prevalence using the OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium. Obes Res Clin Pract 2019; 13 (1): 12–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mainous AG, Rooks B, Tanner RJ, et al. Shared care for adults with sickle cell disease: an analysis of care from eight health systems. J Clin Med 2019; 8 (8): 1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Savitz DA, Hu H.. Ambient heat and stillbirth in Northern and Central Florida. Environ Res 2021; 199: 111262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vadaparampil ST, Fuzzell LN, Rathwell J, et al. HCV testing: order and completion rates among baby boomers obtaining care from seven health systems in Florida, 2015–2017. Prev Med 2020; 106222. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. He Z, Bian J, Carretta HJ, et al. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among older adults in Florida and the United States: comparative analysis of the OneFlorida Data Trust and national inpatient sample. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20 (4): e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McDonough CW, Babcock K, Chucri K, et al. Optimizing identification of resistant hypertension: computable phenotype development and validation. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2020; 29 (11): 1393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morris HL, Donahoo WT, Bruggeman B, et al. An iterative process for identifying pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes: retrospective observational study. JMIR Med Inform 2020; 8 (9): e18874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnston A, Jones WS, Hernandez AF.. The ADAPTABLE trial and aspirin dosing in secondary prevention for patients with coronary artery disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2016; 18 (8): 81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Toh S, Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Harmata EE, et al. ; PCORnet Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) bariatric study cohort: rationale, methods, and baseline characteristics. JMIR Res Protoc 2017; 6 (12): e222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rifas-Shiman SL, Bailey LC, Lunsford D, et al. Early life antibiotic prescriptions and weight outcomes in children 10 years of age. Acad Pediatr 2021; 21 (2): 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bachmann KN, Roumie CL, Wiese AD, et al. Diabetes medication regimens and patient clinical characteristics in the national patient-centered clinical research network. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2020; 8 (5): e00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wake Forest School of Medicine. PREVENTABLE—PRagmatic EValuation of evENTs And Benefits of Lipid-lowering in oldEr adults. https://www.preventabletrial.org/home.cfm Accessed June 27, 2021.

- 35.Public Health Informatics Institute. PCORnet CDC COVID-19 Healthcare Data Initiative. PCORnet CDC COVID-19 Healthcare Data Initiative. https://www.phii.org/electronic-healthcare-data-initiative Accessed June 27, 2021.

- 36. Denny JC, Rutter JL, Goldstein DB, et al. ; All of Us Research Program Investigators. The “All of Us” research program. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 668–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Potential effects of electronic laboratory reporting on improving timeliness of infectious disease notification–Florida, 2002-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008; 57: 1325–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The OneFlorida Data Trust is available to investigators for research purposes through the formal policies and procedures established by the OneFlorida Executive Committee. The identifiers of sequential versions of the Data Trust are 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V1, 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V2, 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V3, 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V4, and 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.8063567.V5. The data used to calculate the cost comparisons are provided in the Supplementary Material.