Abstract

Severe asthma constitutes a serious health burden with significant morbidity and socioeconomic costs. The development and introduction of new biologics targeting type 2 inflammation changed the paradigm for management of severe asthma and initiated a biological era. These changes impose a challenge to clinicians in managing difficult-to-treat and severe asthma. To understand the characteristics and heterogeneity of severe asthma and to develop a better strategy to manage it, the Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Working Group on Severe Asthma, has organized the Korean Severe Asthma Registry (KoSAR). In this review, we describe the challenges of severe asthma management regarding diagnosis, disease burden, heterogeneity, guidelines, and organization of severe asthma clinics. This review also examines the current global activities of national and regional registries and study groups. In addition, we present the KoSAR vision and organization and describe the findings of KoSAR in comparison with those of other countries.

Keywords: Severe asthma, Registries, Biological products, Real world

INTRODUCTION

With implementation of preventive and therapeutic strategies for asthma at national and clinical levels, there has been a notable improvement in the outcomes. However, recent analyses using Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) data showed that the overall prevalence of and mortality from asthma remain high [1]. Asthma-related death and frequent hospitalization due to acute exacerbations mostly occur in patients with uncontrolled and severe asthma. Moreover, severe asthma is linked to high use of healthcare facilities and high economic costs [2].

The substantial burden of severe asthma has been a driving force in the development of novel drugs. Following the introduction of anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody, the first biologic for severe asthma, monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin 5 (IL-5), IL-5 receptor (IL-5R), or IL-4R have been developed and approved for treatment of severe asthma. Furthermore, several more novel drugs targeting other critical molecules in the pathogenesis of severe asthma are under development. The availability of new biological agents has created a novel paradigm for management of severe asthma [3], addressing a number of issues.

To understand severe asthma and to address various issues regarding its management, national and international registries have been developed. In Korea, a national registry of severe asthma has been established by the Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology (KAAACI), Working Group on Severe Asthma, and named the Korean Severe Asthma Registry (KoSAR) [4]. The present paper describes the challenges in the management of severe asthma and the relevant global research. This paper also presents the vision, organization, and findings of the KoSAR.

CHALLENGES OF SEVERE ASTHMA MANAGEMENT

Defining severe asthma

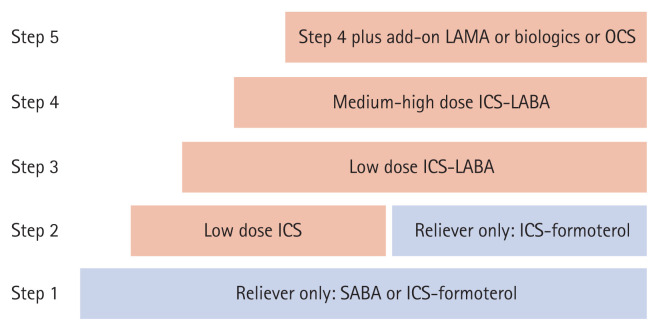

In the treatment of asthma, stepwise approaches are recommended to achieve and maintain asthma control (Fig. 1). Severe asthma often is defined as uncontrolled asthma despite the use of higher treatment steps and correction of modifiable factors. While various definitions of severe asthma have been suggested by international and national organizations, the major criteria for diagnosis include uncontrolled asthma symptoms, frequent exacerbations, lung function decline, and requirement of a higher treatment level (Table 1) [5–7]. Complexity in the determination of the levels of asthma control and asthma severity leads to challenges for clinicians. Difficulties in identifying severe asthma might contribute to a low referral rate and a high proportion of unrecognized severe asthma cases in primary care [8].

Figure 1.

Stepwise approach for asthma management. LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroid; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta2 agonist.

Table 1.

Definitions of uncontrolled, difficult-to-treat, and severe asthma

| GINA | ERS/ATS | KAAACI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled asthma | Uncontrolled asthma includes one or both of the followings: Poor symptom control (frequent symptoms or reliever use, activity limited by asthma, night waking due to asthma) Frequent exacerbations (≥ 2/year) requiring OCS, or serious exacerbations (≥ 1/year) requiring hospitalization |

Uncontrolled asthma defined as at least one of the following: Poor symptom control: ACQ consistently > 1.5, ACT > 20 (or “not well controlled” by NAEPP/GINA guidelines) Frequent severe exacerbations: two or more bursts of systemic CS (> 3 days each) in the previous year Serious exacerbations: at least one hospitalization, ICU stay or mechanical ventilation in the previous year Airflow limitation: after appropriate bronchodilator withhold FEV1 < 80% predicted (in the face of reduced FEV1/FVC defined as less than the lower limit of normal) |

Uncontrolled asthma symptom (3 or 4 of criteria) ≥ 2 Daytime symptoms/weeks in the past 4 weeks Any night waking in the past 4 weeks Reliever used ≥ 2/week in the past 4 weeks Any activity limitation in the past 4 weeks OR Partly controlled asthma symptom (1 or 2 criteria) plus one risk factor for poor outcome Reduced lung function (FEV1 predicted value ≤ 80%) History of asthma exacerbation (OCS bursts ≥ 2/year or hospitalization ≥ 1/year) |

| Difficult-to-treat asthma | Asthma that is uncontrolled despite prescribing of medium or high dose ICS-LABA treatment or that requires high dose ICS-LABA treatment to maintain good symptom control and reduce exacerbations. | Difficult asthma include uncontrolled asthma in whom appropriate diagnosis and/or assessment of confounding factors and comorbidities vastly improves their current condition. | Asthma that is uncontrolled with GINA step 4 or 5 treatment |

| Severe asthma | Asthma that is uncontrolled despite adherence with optimized high dose ICS-LABA therapy and treatment of contributory factors, or that worsens when high dose treatment is decreased. | Asthma which requires treatment with guidelines suggested medications for GINA steps 4–5 asthma (high dose ICS and LABA or leukotriene modifier/theophylline) for the previous year or systemic CS for ≥ 50% of the previous year to prevent it from becoming “uncontrolled” or which remains “uncontrolled” despite this therapy Controlled asthma that worsens on tapering of these high doses of ICS or systemic CS (or additional biologics) |

Asthma that is still uncontrolled after 3–6 months of optimizing treatment including both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment: Confirmation of asthma diagnosis Correction of modifiable risk factors Control of comorbidities |

GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ERS, European Respiratory Society; ATS, American Thoracic Society; KAAACI, Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology; OCS, oral corticosteroid; ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; ACT, Asthma Control Test; NAEPP, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program; CS, corticosteroid; ICU, intensive care unit; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta2 agonist.

In an expert opinion paper by the KAAACI [9], we suggested an integrated approach to uncontrolled asthma, difficult-to-treat asthma, and severe asthma. Criteria for uncontrolled asthma included frequent symptoms day and night, frequent use of a reliever, any activity limitation, reduced lung function, and history of exacerbation in the previous year. Confirmation of asthma diagnosis, correction of modifiable risk factors, and control of comorbidities are required in the evaluation of difficult-to-treat asthma. We recommended referral of patients with severe asthma to asthma specialists or severe asthma clinics for phenotype assessment and use of add-on medications like biologics.

Epidemiology and disease burden in Korea

The prevalence of severe asthma is estimated to be about 5% to 10% of all asthma patients [10], but this prevalence varies depending on the definition of severe asthma and the study population. Data from the Korean NHIS showed that the prevalence of severe asthma has increased over the past decade [1]. Asthma specialists in Korea estimated that 13.9% of the asthma patients presenting to their clinics have severe asthma [11]. Despite the low proportion of severe asthma patients, mortality and economic costs are much higher in patients with severe asthma than in those with mild to moderate disease [12]. Moreover, systemic corticosteroids are used frequently for exacerbations and maintenance of severe asthma. Analysis of the asthma medications used in treatment in Korea showed a strikingly high number of patients using oral corticosteroids (OCS), while the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) is low [13]. These findings suggest that the asthma guidelines have not been adopted and applied uniformly by the primary care physicians in Korea [14]. Analysis of data from 11 national registries of severe asthma in Europe showed that OCS maintenance is common, ranging in prevalence from 21.0% to 63.0% [15]. Higher chronic use of OCS leads to increased risk of complications, costs, and dose-dependent mortality [16–18]. Furthermore, patients with severe asthma experience severe physical and psychological distress from exacerbations [19]. Nonetheless, physicians and regulatory authorities have not acknowledged the extent of the severe asthma burden.

Heterogeneity of severe asthma

As with asthma, severe asthma is heterogeneous with multiple phenotypes and endotypes [20]. Phenotypes of asthma can be determined and classified into various categories by clinical, trigger-related, or inflammatory characteristics [21]. While allergic/non-allergic phenotypes and intrinsic/extrinsic phenotypes were used for a long time, inflammatory phenotypes, which can be determined as eosinophilic, neutrophilic, or pauci-granulocytic, are also useful to guide the pharmacological treatment of severe asthma. In addition, endotypes of severe asthma can be defined by different mechanisms underlying severe asthma and networks of the innate and adaptive immune responses [22]. Ongoing researches on the phenotypes and endotypes of severe asthma would enhance our understanding of the pathobiology of severe asthma and develop precision medicine in severe asthma.

Responses to medications can differ according to demographic and clinical characteristics. Particularly, biologics targeting type 2 cytokines and IgE showed significant efficacy in asthma outcomes such as exacerbations and lung function. These biologics are approved for use in patients with severe asthma with type 2 inflammation, characterized by eosinophilic and allergic phenotypes [23]. Moreover, there is a variety of treatable traits that require identification in patients with severe asthma [24,25]. While comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in severe asthma usually is diagnosed as asthma-COPD overlap (ACO), determination of COPD might not be consistent among specialists [26]. The prevalence of ACO is especially high in older male patients with severe asthma [27]. There is little evidence regarding pharmacological treatment of ACO [28].

Various biomarkers are utilized to determine phenotypes, endotypes, and treatable traits of severe asthma. Notably, type 2 biomarkers, such as blood and sputum eosinophils, exhaled nitric oxide, and skin test positivity to perennial allergens, play important roles in determining which patients would benefit from biological agent therapy [29]. However, a questionnaire survey among asthma specialists in Korea suggested that phenotyping of severe asthma and application of various diagnostic tests are not widespread [11].

Guidelines for severe asthma

With the introduction of biologics in the management of severe asthma, there has been a growing demand for practical guidelines. To meet this demand and assist practitioners in treating severe asthma, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) published a 2019 pocket guide, ‘Diagnosis and Management of Difficult-to-treat and Severe Asthma in Adolescent and Adult Patients.’ This guide later was incorporated into a main report [30]. In addition, new European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines were published focusing on the pharmacological treatment of severe asthma including biologics (anti-IL5, anti-IL5R, and anti-IL4Rα), long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), and macrolides [29]. The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) also published guideline on the use of biologics for severe asthma [23]. Some countries including Canada [31], China [32], and those in Latin America [33], published their national guidelines or position papers on difficult-to-treat asthma and severe asthma. The Working Group on Severe Asthma of the KAAACI, issued an expert opinion paper on evaluation and management of difficult-to-treat asthma and severe asthma [9]. International and national guidelines or position papers on severe asthma are described in Table 2. These guidelines require updating to include new therapeutic agents for severe asthma such as triple therapy in a single inhaler [34–36]. For those who did not show good response to type 2-targeted therapy and those without evidence of type 2 inflammation, azithromycin or low dose OCS should be considered as add-on treatment.

Table 2.

National and international guidelines and position papers regarding severe asthma

| Title of guidelines or position paper (year) | Country | Organization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GINA pocket guide, Diagnosis and management of difficult-to-treat and severe asthma in adolescent and adult patients (2019) | International | GINA | [30] |

| Management of severe asthma: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline (2020) | Europe and United States | ERS and ATS | [29] |

| EAACI Biologicals Guidelines-recommendations for severe asthma | Europe | EAACI | [23] |

| Recognition and management of severe asthma: a Canadian Thoracic Society position statement (2017) | Canada | Canadian Thoracic Society | [31] |

| Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and management of severe asthma (2018) | China | Asthma Workgroup of the Chinese Thoracic Society, Chinese Medical Association, and China Asthma Alliance |

[32] |

| Evaluation and management of difficult-to-treat and severe asthma: an expert opinion (2020) | Korea | KAAACI, Working Group on Severe Asthma | [9] |

| Severe asthma: adding new evidence: Latin American Thoracic Society (2021) | Latin America | Latin America Thoracic Society | [33] |

GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ERS, European Respiratory Society; ATS, American Thoracic Society; EAACI, European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; KAAACI, Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Setting up severe asthma clinics

While most patients with asthma are managed by primary care physicians, severe asthma management should be performed at a specialty center [37]. This level of treatment facility optimizes the possibility of favorable treatment results [38]. Approaches to uncontrolled asthma include confirmation of asthma, evaluation of comorbidities, and use of advanced medications based on asthma phenotype. Thus, asthma guidelines underscore the necessity of specialist referral of patients in whom asthma is uncontrolled despite the use of advanced treatments [30,39]. To provide comprehensive and specialized care, severe asthma clinics or centers should be equipped with appropriate facilities and specialists, including physicians, nurses, and pharmacists [40]. Moreover, a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach to uncontrolled asthma leads to improved treatment outcomes [41]. Table 3 describes the roles and capacities of severe asthma clinics. Education of patients should be one of the major services of severe asthma clinics since correction of poor treatment adherence and inhaler technique can be improved to reduce the need for OCS and hospitalization [42]. Given that the proportion of current smokers in Korean subjects is higher than in other countries [4], a smoking cessation program should be a part of the severe asthma clinic services. Recognition and referral of patients with severe asthma from primary care could be derived by setting up partnership between primary care and severe asthma clinics and education program of the general physicians.

Table 3.

Capacity required for specialized severe asthma clinics

| Category | Purpose | Service or facility |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Confirmation of diagnosis of asthma Differential diagnosis of asthma Assessment of level of asthma control |

Spirometry Bronchodilator response Bronchial provocation test Chest CT Bronchoscopy Laryngoscopy Laboratory tests: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies |

| Phenotyping | Evaluation of inflammatory and immunological phenotypes | Blood and sputum eosinophils (sputum induction and processing) exhaled nitric oxide skin tests and serum-specific IgE |

| Comorbidities | Assessment of comorbidities Treatment of comorbidities Multidisciplinary care |

Management of chronic rhinosinusitis, GERD, sleep apnea, obesity, aspirin hypersensitivity, depression, and anxiety disorder multidisciplinary team Specialty consultation: allergists, pulmonologists, otolaryngologists, psychiatrists |

| Medications | Controllers including biologics Adverse reactions to asthma medications |

Facilities for biologics medications: injection and monitoring of adverse reactions Emergency care for anaphylaxis |

| Patient education | Understanding asthma and severe asthma Action plan for exacerbation Inhaler technique Selection of appropriate inhalers Smoking cessation Environmental control |

Patient education program Specialist nurses and pharmacists Education materials and resources |

| Referral | Partnership with general physicians Recognition of severe asthma in primary care |

Education of the general physicians Referral system from primary clinics |

CT, computed tomography; IgE, immunoglobulin E; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

REGISTRIES AND STUDY GROUPS ON SEVERE ASTHMA

Strengths and opportunities of a severe asthma registry

Registries of severe asthma can offer valuable opportunities to assess the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in addition to the assessment of actual treatment responses and adverse reactions of heterogeneous severe asthma [43]. In addition to baseline characteristics, registry follow-up information would include the long-term course of severe asthma according to phenotype and treatment. National severe asthma registries deliver country-specific information and knowledge from enrolled subjects managed by country-specific healthcare and referral systems. Many countries, including the United Kingdom [44], Italy [45], France [46], Belgium [47], Spain [48], Portugal [49], Austria [50], Germany [51], and Russia [52], the United States [53], Korea [4], and Austalia [54], have established national registries (Table 4).

Table 4.

National and international registries and study groups focused on severe asthma

| Name | Country | Organization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| National: Europe | |||

| UK Severe Asthma Registry (UKSAR) | United Kingdom | BTS | [44] |

| Severe Asthma Network in Italy (SANI) registry | Italy | SANI | [45] |

| COhort of BRonchial obstruction and Asthma (COBRA) | France | [46] | |

| Belgian Severe Asthma Registry (BSAR) | Belgium | Belgian Thoracic Society | [47] |

| Spanish Registry of Severe Asthma | Spain | [48] | |

| Portuguese Severe Asthma Registry | Portugal | REAG | [49] |

| Austrian Severe Asthma Registry | Austria | Austrian Severe Asthma Net (ASA-Net) | [50] |

| German Severe Asthma Registry | Germany | German Asthma Net | [51] |

| Russian Severe Asthma Registry (RSAR) | Russia | Russian Respiratory Society | [52] |

| National: North America | |||

| CHRONICLE | United States | [53] | |

| Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) | United States | [58] | |

| National: Asia-Pacific | |||

| Korean Severe Asthma Registry (KoSAR) | Korea | KAAACI | [4] |

| Australian Severe Asthma Registry (ASAR) | Australia | Australian Severe Asthma Network (ASAN), TSANZ | [54] |

| International | |||

| Severe Heterogeneous Asthma Research collaboration, Patient-centred (SHARP) | Europe | ERS | [55] |

| African Severe Asthma Project (ASAP) | Africa | [56] | |

| International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR) | World | [57] | |

| Unbiased Biomarkers for the Prediction of Respiratory Disease Outcomes (U-BIOPRED) | Europe | [60] | |

BTS, British Thoracic Society; REAG, Rede de Especialistas em Asma Grave; KAAACI, Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology; TSANZ, Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand; ERS, European Respiratory Society.

In addition to national registries, international or regional registries create the possibility for comparison of patient characteristics between countries. The ERS launched a clinical research collaboration on severe asthma in 2018, the Severe Heterogeneous Asthma Research collaboration, Patient-centred (SHARP) [55]. Comparisons of the characteristics and treatment of severe asthma by the SHARP showed wide variation and heterogeneity across 11 European countries [15]. A regional registry of the African Severe Asthma Project (ASAP) showed unique characteristics of severe asthma in East Africa (Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia), where only 14.0% of patients, including severe asthma patients, used ICS [56]. The International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR) was organized to collect data from national registries for comparison across countries [57]. Such sufficiently large datasets could generate reliable and powerful answers to various research questions.

Study consortiums on the mechanisms of severe asthma

Unlike the national and international registries, there are study groups to address the mechanisms of severe asthma. The U.S. Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) is a US research consortium established by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health in 2011 [58]. Investigators in the SARP recruited a large number of asthma patients and explored the heterogeneity of severe asthma using various clinical, genetic, imaging, and biomarker analyses [59]. In Europe, the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI)-funded consortium Unbiased BIOmarkers for the Prediction of REspiratory Disease outcomes (U-BIOPRED) improved our understanding of the mechanisms of severe asthma using a systems biology approach [60].

KOREAN SEVERE ASTHMA REGISTRY

Vision and organization

The KoSAR (https://severeasthmawg.com) was established in 2011, by the KAAACI, Working Group on Severe Asthma. This registry aimed to assess the demographics, clinical characteristics, and heterogeneous phenotypes of severe asthma. We also gained an understanding of the natural course and progression of severe asthma and the responses and adverse reactions to medications through long-term regular follow-ups. Moreover, we aimed to estimate the burden and treatment status of severe asthma and to develop better strategies for management of severe asthma in Korea. For this purpose, allergy or respiratory centers of the university hospitals and the members of the KAAACI working group (allergists or pulmonologists) have participated in this study (Supplementary Table 1). With the same study protocol and approval of the Institutional Review Board of each participating center, 31 centers in Korea have enrolled subjects with severe asthma (Fig. 2). We enrolled adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with severe asthma who were treated for more than 1 year. Severe asthma was defined as uncontrolled despite the use of GINA step 4 or 5 treatment according to the international guidelines of the ERS and the ATS [7]. Asthma is defined as uncontrolled (1) when GINA step 4 or 5 treatment is unsuccessful or (2) when symptoms are relatively controlled with GINA step 4 or 5 treatment but frequent or serious exacerbations occur. At the time of enrollment, frequent exacerbation is defined as OCS bursts ≥ 3 times per year, and serious exacerbation is defined as ≥ 1 hospitalization or visit to the emergency department per year. Uncontrolled asthma also includes any near-fatal exacerbation and loss of asthma control upon reduction of ICS or OCS dose. A web-based electronic case report form and electronic data capture system were used to collect and extract anonymized data from the enrolled subjects. The Data Management Committee evaluated the administered data quality at each center by programmed queries on the central web-based database of the KoSAR. Table 5 summarizes the data collected by the KoSAR. Longitudinal data also are collected by regular follow-up of the enrolled subjects.

Figure 2.

Locations of participating Korean Severe Asthma Registry (KoSAR) institutions.

Table 5.

KoSAR findings

| Category | Information |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Age, sex, height, weight, body mass index Smoking status and past smoking Previous and current occupations Living area Owning a pet |

| Diagnosis | Physician (specialist) diagnosis of asthma Onset and duration of asthma Treatment period of asthma Family history of allergic diseases (asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis) Combined COPD |

| Exacerbations | Frequency of exacerbations and OCS bursts Use of healthcare facilities: visits to outpatient department and emergency department, hospitalization, and use of ICU |

| Asthma control and quality of life | Level of symptom control Asthma Control Test® Quality of Life Questionnaire for Adult Korean Asthmatics |

| Environmental factors | Work-exacerbated asthma Aspirin hypersensitivity Aggravation during menstruation |

| Comorbidities | Current or previous history of diagnosis and duration Current treatment Allergic rhinitis: severity, comorbid sinusitis and nasal polyp, treatment Atopic dermatitis, allergic conjunctivitis, GERD, sleep apnea, depression, anxiety disorder, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmia, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and bronchiectasis Previous history of pulmonary tuberculosis, pneumonia, pertussis, and measles |

| Asthma medications | Controllers including inhalers and biologics OCS and immunosuppressant Adherence to medications Use of SABA |

| Lung function tests | Spirometry Bronchodilator response Lung volume Bronchial provocation test |

| Laboratory tests | Skin prick test to aeroallergens Peripheral blood eosinophils Total IgE Induced sputum analysis Exhaled nitric oxide |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OCS, oral corticosteroid; ICU, intensive care unit; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; SABA, short-acting beta2 agonist; IgE, immunoglobulin E.

Observations from the KoSAR

The demographic and clinical characteristics of severe asthma vary according to study subjects and their ethnic groups [15,61]. Compared with severe asthma patients enrolled in the registries from the European countries and the United States, the Korean patients with severe asthma were older (mean age of 62.3 ±14.0 years) with older onset time (mean age of onset 40.8 ± 17.4 years) [4]. There were more females (54.9%), similar to European countries in which the percentage of females ranged from 48.1% to 70.0%. Body mass index was relatively lower in Korean patients with severe asthma than in Western countries. In terms of maintenance medications, Korean patients used more oral medications like leukotriene receptor antagonists and theophylline. The prescription of biologics was extremely low in Korea.

The KoSAR neither excluded nor restricted patients who smoke currently or who ceased smoking before enrollment, leading to inclusion of a substantial number of current smokers (12.3%) and ex-smokers (33.7%). In addition, the principal investigator of each institution determined if subjects could be diagnosed with ACO at the time of enrollment. About one-fourth of severe asthma patients in the KoSAR were classified as having ACO [27]. ACO patients required more frequent OCS bursts and emergency department visits for asthma exacerbations than those with asthma only. These findings suggest that a novel approach to severe asthma is needed considering COPD, as clinical trials of new therapeutic agents including biologics in severe asthma usually exclude subjects with diagnosis of COPD. Retrospective analysis of the effects and safety of therapeutic drugs using data from severe asthma registries would be of help in developing better strategies to manage severe asthma with features of COPD.

KoSAR Biologics registry

With a better understanding of the mechanisms of asthma, new therapeutic agents targeting the key molecules and cytokines in type 2 airway inflammation and immune responses in asthma have been developed. Biologics, mostly monoclonal antibodies inhibiting cytokines and receptors, have proven clinical benefits, especially in certain phenotypes of severe asthma. These benefits include reduction of exacerbations and improvement of asthma control, quality of life, and lung function [62,63]. Omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody to IgE, is the first biologic approved for treatment of uncontrolled allergic asthma [64]. Recently, monoclonal antibodies binding to IL-5 (mepolizumab and reslizumab), IL-5R (benralizumab), and IL-4Rα (dupilumab) were developed and approved sequentially for Koreans with severe asthma. These biologics are expected to improve asthma control and quality of life of asthma sufferers.

While omalizumab was approved and introduced in clinical practice in 2007, in Korea, the prescription of omalizumab has been low even in eligible patients with severe asthma [4]. In a 2015 survey of perceptions and practices concerning severe asthma, Korean asthma specialists responded that only 3.3% of the patients with severe asthma were prescribed biologics [11]. The use of biologics in severe asthma is much lower in Korea than in other countries [61]. The critical hurdle for the use of biologics is the high cost since most are not reimbursed by the Korean NHIS. In 2020, omalizumab was approved for reimbursement in cases of severe allergic asthma with frequent exacerbations and decreased lung function despite the use of high dose ICS, long-acting beta2-agonists, and LAMA. Reimbursement should be made for appropriate severe asthma patients upon assessment by an asthma specialist.

While clinical trials of biologics showed efficacy and safety in severe asthma, there are many questions that need to be answered. Australian investigators examined the effectiveness of omalizumab and mepolizumab and factors predictive of good response to these biologics using data from the Australian Xolair Registry [65] and the Australian Mepolizumab Registry [66]. The UK Severe Asthma Registry explored the effectiveness of mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma by retrospective review of enrolled patients [67]. The Spanish Registry evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of omalizumab in patients with allergic asthma [48] and non-atopic asthma [68]. Severe asthma registries have the potential to evaluate the effectiveness, responses, and safety of biologics in everyday settings. Furthermore, the prescription patterns, causes of discontinuation, and switching of biologics could be assessed by analyzing data from the registries. To answer the various questions regarding biologics use, we organized the KoSAR Biologics registry (KoSAR-BIO). Recruitment of a large number of patients using biologics and collection of qualified data will provide the opportunity and power to conduct analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

Severe asthma needs to be acknowledged as a ‘severe’ disease considering the detrimental impacts on quality of life, socioeconomic cost, and life of the affected patient. Furthermore, the seriousness of severe asthma should be understood by patients, healthcare professionals, national governments, policymakers, pharmaceutical companies, and the public. As a recently suggested patient charter argued [69], a specialized health policy and a dedicated campaign are needed to improve patient care in severe asthma. In line with the severe asthma registries in other countries, we organized the KoSAR to understand the characteristics, heterogeneity, and phenotypes of severe asthma in Korea. In the era of biologics for treatment of severe asthma, we hope to find ways to use biologics wisely and to improve treatment outcomes of severe asthmatic patients based on knowledge obtained from the KoSAR-BIO.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HC19C0318). The authors thank the investigators, clinical research coordinators, and participants for their time and efforts in the KoSAR.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Supplementary Information

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee E, Kim A, Ye YM, Choi SE, Park HS. Increasing prevalence and mortality of asthma with age in Korea, 2002–2015: a nationwide, population-based study. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12:467–484. doi: 10.4168/aair.2020.12.3.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SH, Kim TW, Kwon JW, et al. Economic costs for adult asthmatics according to severity and control status in Korean tertiary hospitals. J Asthma. 2012;49:303–309. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.641046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agache I, Cojanu C, Laculiceanu A, Rogozea L. Critical points on the use of biologicals in allergic diseases and asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12:24–41. doi: 10.4168/aair.2020.12.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim MH, Kim SH, Park SY, et al. Characteristics of adult severe refractory asthma in Korea analyzed from the Severe Asthma Registry. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2019;11:43–54. doi: 10.4168/aair.2019.11.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bousquet J, Mantzouranis E, Cruz AA, et al. Uniform definition of asthma severity, control, and exacerbations: document presented for the World Health Organization Consultation on Severe Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:926–938. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bel EH, Sousa A, Fleming L, et al. Diagnosis and definition of severe refractory asthma: an international consensus statement from the Innovative Medicine Initiative (IMI) Thorax. 2011;66:910–917. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.153643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:343–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan D, Heatley H, Heaney LG, et al. Potential severe asthma hidden in UK primary care. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1612–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim BK, Park SY, Ban GY, et al. Evaluation and management of difficult-to-treat and severe asthma: an expert opinion from the Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the Working Group on Severe Asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12:910–933. doi: 10.4168/aair.2020.12.6.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hekking PW, Wener RR, Amelink M, Zwinderman AH, Bouvy ML, Bel EH. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SH, Moon JY, Lee JH, et al. Perceptions of severe asthma and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome among specialists: a questionnaire survey. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10:225–235. doi: 10.4168/aair.2018.10.3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee YJ, Kwon SH, Hong SH, et al. Health care utilization and direct costs in mild, moderate, and severe adult asthma: a descriptive study using the 2014 South Korean Health Insurance Database. Clin Ther. 2017;39:527–536. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi JY, Yoon HK, Lee JH, et al. Current status of asthma care in South Korea: nationwide the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:3208–3214. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.08.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jo EJ, Kim MY, Kim SH, et al. Implementation of asthma management guidelines and possible barriers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e72. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Bragt JJMH, Adcock IM, Bel EHD, et al. Characteristics and treatment regimens across ERS SHARP severe asthma registries. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901163. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01163-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefebvre P, Duh MS, Lafeuille MH, et al. Acute and chronic systemic corticosteroid-related complications in patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1488–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voorham J, Xu X, Price DB, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with incremental systemic corticosteroid exposure in asthma. Allergy. 2019;74:273–283. doi: 10.1111/all.13556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H, Ryu J, Nam E, et al. Increased mortality in patients with corticosteroid-dependent asthma: a nationwide population-based study. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:1900804. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00804-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song WJ, Won HK, Lee SY, et al. Patients’ experiences of asthma exacerbation and management: a qualitative study of severe asthma. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7:00528–2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00528-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore WC, Fitzpatrick AM, Li X, et al. Clinical heterogeneity in the severe asthma research program. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(Suppl):S118–S124. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201309-307AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenzel SE. Asthma: defining of the persistent adult phenotypes. Lancet. 2006;368:804–813. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agache I. Severe asthma phenotypes and endotypes. Semin Immunol. 2019;46:101301. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2019.101301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agache I, Akdis CA, Akdis M, et al. EAACI biologicals guidelines-recommendations for severe asthma. Allergy. 2021;76:14–44. doi: 10.1111/all.14425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald VM, Hiles SA, Godbout K, et al. Treatable traits can be identified in a severe asthma registry and predict future exacerbations. Respirology. 2019;24:37–47. doi: 10.1111/resp.13389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agusti A, Bel E, Thomas M, et al. Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:410–419. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01359-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MA, Park HW, Kim BK, et al. Specialist perception of severe asthma in Korea: a questionnaire survey. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2021;13:507–514. doi: 10.4168/aair.2021.13.3.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H, Kim SH, Kim BK, et al. Characteristics of specialist-diagnosed asthma-COPD overlap in severe asthma: observations from the Korean Severe Asthma Registry (KoSAR) Allergy. 2021;76:223–232. doi: 10.1111/all.14483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo M, Tamaoki J. Therapeutic approaches of asthma and COPD overlap. Allergol Int. 2018;67:187–90. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holguin F, Cardet JC, Chung KF, et al. Management of severe asthma: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1900588. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00588-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Global Initiative for Asthma . Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention [Internet] Fontana (WI): GINA; 2022. [cited 2022 Jan 12]. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org . [Google Scholar]

- 31.FitzGerald JM, Lemiere C, Lougheed MD, et al. Recognition and management of severe asthma: a Canadian Thoracic Society position statement. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2017;1:199–221. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J, Yang D, Huang M, et al. Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and management of severe asthma. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:7020–7044. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.11.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia G, Bergna M, Vasquez JC, et al. Severe asthma: adding new evidence: Latin American Thoracic Society. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7:00318–2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00318-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerstjens HA, Maspero J, Chapman KR, et al. Once-daily, single-inhaler mometasone-indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus mometasone-indacaterol or twice-daily fluticasone-salmeterol in patients with inadequately controlled asthma (IRIDIUM): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1000–1012. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee LA, Bailes Z, Barnes N, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily single-inhaler triple therapy (FF/UMEC/VI) versus FF/VI in patients with inadequately controlled asthma (CAPTAIN): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3A trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:69–84. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virchow JC, Kuna P, Paggiaro P, et al. Single inhaler extrafine triple therapy in uncontrolled asthma (TRIMARAN and TRIGGER): two double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394:1737–1749. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sferrazza Papa GF, Milanese M, Facchini FM, Baiardini I. Role and challenges of severe asthma services: insights from the UK registry. Minerva Med. 2017;108(3 Suppl 1):13–17. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4806.17.05323-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibeon D, Heaney LG, Brightling CE, et al. Dedicated severe asthma services improve health-care use and quality of life. Chest. 2015;148:870–876. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Expert Panel Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) administered and coordinated National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee (NAEPPCC) Cloutier MM, Baptist AP, et al. 2020 Focused updates to the asthma management guidelines: a report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:1217–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDonald VM, Vertigan AE, Gibson PG. How to set up a severe asthma service. Respirology. 2011;16:900–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burke H, Davis J, Evans S, Flower L, Tan A, Kurukulaaratchy RJ. A multidisciplinary team case management approach reduces the burden of frequent asthma admissions. ERJ Open Res. 2016;2:00039–2016. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00039-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gamble J, Stevenson M, Heaney LG. A study of a multi-level intervention to improve non-adherence in difficult to control asthma. Respir Med. 2011;105:1308–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.FitzGerald JM, Alramezi Y. The challenges and opportunities of maximizing the benefits of severe asthma registries. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1469–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heaney LG, Brightling CE, Menzies-Gow A, Stevenson M, Niven RM, British Thoracic Society Difficult Asthma Network Refractory asthma in the UK: cross-sectional findings from a UK multicentre registry. Thorax. 2010;65:787–794. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.137414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Senna G, Guerriero M, Paggiaro PL, et al. SANI-Severe Asthma Network in Italy: a way forward to monitor severe asthma. Clin Mol Allergy. 2017;15:9. doi: 10.1186/s12948-017-0065-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pretolani M, Soussan D, Poirier I, et al. Clinical and biological characteristics of the French COBRA cohort of adult subjects with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700019. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00019-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schleich F, Brusselle G, Louis R, et al. Heterogeneity of phenotypes in severe asthmatics: the Belgian Severe Asthma Registry (BSAR) Respir Med. 2014;108:1723–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vennera Mdel C, Perez De Llano L, Bardagi S, et al. Omalizumab therapy in severe asthma: experience from the Spanish registry: some new approaches. J Asthma. 2012;49:416–422. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.668255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sa-Sousa A, Fonseca JA, Pereira AM, et al. The Portuguese Severe Asthma Registry: development, features, and data sharing policies. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1495039. doi: 10.1155/2018/1495039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doberer D, Auer W, Loeffler-Ragg J, et al. The Austrian Severe Asthma Registry. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127:821–822. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korn S, Hubner M, Hamelmann E, Buhl R. Das Register “Schweres Asthma”. [The German Severe Asthma Registry]. Pneumologie. 2012;66:341–344. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1308908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nenasheva N, Belevsky A. Characteristics of patients with severe asthma in the Russian Federation-the Russian Severe Asthma Registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A1337. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ambrose CS, Chipps BE, Moore WC, et al. The CHRONICLE study of US adults with subspecialist-treated severe asthma: objectives, design, and initial results. Pragmat Obs Res. 2020;11:77–90. doi: 10.2147/POR.S251120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand Leaders in Lung Health . Australasian Severe Asthma Registry [Internet] Sydney (AU): TSANZ; 2022. [cited 2022 Jan 12]. Available from: https://www.thoracic.org.au/researchawards/australasian-severe-asthma-registry-asar . [Google Scholar]

- 55.Djukanovic R, Adcock IM, Anderson G, et al. The Severe Heterogeneous Asthma Research collaboration, Patient-centred (SHARP) ERS Clinical Research Collaboration: a new dawn in asthma research. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1801671. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01671-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kirenga B, Chakaya J, Yimer G, et al. Phenotypic characteristics and asthma severity in an East African cohort of adults and adolescents with asthma: findings from the African severe asthma project. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2020;7:e000484. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.ISAR Study Group International Severe Asthma Registry: mission statement. Chest. 2020;157:805–814. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wenzel SE, Busse WW, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program Severe asthma: lessons from the Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jarjour NN, Erzurum SC, Bleecker ER, et al. Severe asthma: lessons learned from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:356–362. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1317PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shaw DE, Sousa AR, Fowler SJ, et al. Clinical and inflammatory characteristics of the European U-BIOPRED adult severe asthma cohort. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:1308–1321. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00779-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang E, Wechsler ME, Tran TN, et al. Characterization of severe asthma worldwide: data from the International Severe Asthma Registry. Chest. 2020;157:790–804. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agache I, Rocha C, Beltran J, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with biologicals (benralizumab, dupilumab and omalizumab) for severe allergic asthma: a systematic review for the EAACI Guidelines: recommendations on the use of biologicals in severe asthma. Allergy. 2020;75:1043–1057. doi: 10.1111/all.14235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agache I, Beltran J, Akdis C, et al. A systematic review for the EAACI guidelines: recommendations on the use of biologicals in severe asthma. Allergy. 2020;75:1023–1042. doi: 10.1111/all.14221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jung JW, Park HS, Park CS, et al. Effect of omalizumab as add-on therapy to Quality of Life Questionnaire for Korean Asthmatics (KAQLQ) in Korean patients with severe persistent allergic asthma. Korean J Intern Med. 2021;36:1001–1013. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2020.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gibson PG, Reddel H, McDonald VM, et al. Effectiveness and response predictors of omalizumab in a severe allergic asthma population with a high prevalence of comorbidities: the Australian Xolair Registry. Intern Med J. 2016;46:1054–1062. doi: 10.1111/imj.13166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harvey ES, Langton D, Katelaris C, et al. Mepolizumab effectiveness and identification of super-responders in severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1902420. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02420-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kavanagh JE, d’Ancona G, Elstad M, et al. Real-world effectiveness and the characteristics of a “super-responder” to mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest. 2020;158:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Llano LP, Vennera Mdel C, Alvarez FJ, et al. Effects of omalizumab in non-atopic asthma: results from a Spanish multicenter registry. J Asthma. 2013;50:296–301. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.757780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Menzies-Gow A, Canonica GW, Winders TA, Correia de Sousa J, Upham JW, Fink-Wagner AH. A charter to improve patient care in severe asthma. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1485–1496. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0777-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.