Summary

Background

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents is a significant mental health problem around the world. Here, we performed a meta-analysis to systematically delineate the risk factors for NSSI.

Method

We searched Medline, Embase, Web of Science and Cochrane for relevant articles and abstracts published prior to 12 November 2021. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confident intervals (CIs) were used to assess various risk factors, and publication bias was assessed by Egger's test, the trim and fill method and meta-regression. This study is registered with PROSPERO, CRD42021265885.

Results

A total of 25 articles were eventually included in the analysis. Eighty risk factors were identified and classified into 7 categories: mental disorders (ORs, 1·89; 95% CI, 1·60–2·24), bullying (ORs, 1·98; 95% CI, 1·32–2·95), low health literacy (ORs, 2·20; 95% CI, 1·63–2·96), problem behaviours (ORs, 2·36; 95% CI, 2·00–2·77), adverse childhood experiences (ORs, 2·49; 95% CI, 1·85–3.34), physical symptoms (ORs, 2·85; 95% CI, 1·36–5·97) and the female gender (ORs, 2·89; 95% CI, 2·43–3·43). The range of heterogeneity (I2) was from 20·3% to 99·2%.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis found that mental disorders, low health literacy, adverse childhood experiences, bullying, problem behaviours, the female gender and physical symptoms appear to be risk factors for NSSI.

Keywords: Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), Adolescents, Risk factors, Meta-analysis

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Non-suicidal self-injury is a common behaviour that threatens the health of adolescents. Although NSSI is different from attempted suicide, it is a strong predictor of suicide and therefore an important health issue. We searched Medline (through PubMed), Embase, Web of Science and the Cochrane library until 12 November 2021, using the keywords for NSSI “(self-injury behaviour OR Nonsuicidal Self Injury” OR Deliberate Self Harm)” and adolescent “(teen OR youth)” and risk factor “(health correlates OR risk scores)”. We focused on screening articles that clearly distinguished the purpose of self-injury behaviour as non-suicidal and strictly controlled for the age range of adolescents. The quality of most studies was moderate.

Added value of this study

This was the first meta-analysis to address risk factors for self-injury in adolescents only. Our study summarized the risk factors that contribute to NSSI behaviours in this group. The results suggested that mental disorders, low health literacy, adverse childhood experiences, bullying, problem behaviours, the female gender and physical symptoms were indeed risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury adolescents. However, the quality of evidence for bullying and mental disorders was low and needed further study.

Implications of all the available evidence

Based on these risk factors found in the research, parents, teachers, and medical personnel should be vigilant and implement targeted prevention. In addition, more high-quality cohort studies are needed to explore the possible psychological factors and the associated neurophysiological mechanisms behind these possible risk factors.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as direct, repetitive injury to the body without suicidal intent.1 NSSI includes a variety of behavioural patterns, such as cutting, burning, hitting, scratching, and hair pulling. NSSI is a complex behaviour and differs from general risk-taking behaviours; it is intended to hurt the body, not just a byproduct of behaviour.2 The purpose of adolescent NSSI may vary by social and cultural differences. However, the mainstream view is that NSSI may be a strategy for regulating negative emotions.2,3 It has been reported that pooled NSSI (including single acts of self-injury) prevalence was 17.2% amongst adolescents, 13.4% amongst young adults and 5.5% amongst adults.4

NSSI is associated with various poor outcomes, such as cognitive impairments, poor interpersonal relationships, and violent crimes.5 Early adolescent NSSI may predict the occurrence of mental disorders in late adolescence, with increased rates of depression, anxiety and eating disorders.6,7 NSSI also results in negative impacts on family, such as difficulties in parent–child relationships, disrupted family communication, and family functioning.8,9 Self-harm acts are associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescents.10 It is estimated that NSSI as a whole is associated with a 30-fold increase in the risk of suicide attempt when compared with the general population.11

The causes of self-harm behaviour in adolescents are complicated and involve genetic, biological, spiritual, psychological, physiological, social, cultural and other factors.12 Identifying risk factors for NSSI is important for the early recognition and prevention of this behavioural problem. Previous clinical observations and cohort studies have reported various risk factors for NSSI, such as chronic interpersonal stress, early-life adversity, and digital media use. A meta-analysis conducted in 2015 analysed the risk factors for NSSI behaviours in people aged 10 to 4413 and found that there is a lack of unified predictive factors and that standardized NSSI measurements are needed. This updated study aimed to systematically analyse the risk factors associated with NSSI in adolescents to inform NSSI prevention and intervention strategies.

Method

Search strategy

We searched English articles published up to 12 November 2021 in the following databases: Medline (through PubMed), Embase, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. Primary search terms for Medline included (“self-injury behaviour” OR “self-injurious behaviour*” OR “Intentional Self Injury*” OR “Intentional Self Harm” OR “Non-suicidal Self Injury” OR “Non-suicidal Self Injury*” OR “Deliberate Self-Harm” OR “Deliberate Self Harm” OR “Self Injury*” OR “Non Suicidal Self Injury*” OR “Self Harm” OR “Self Destructive Behaviour*”) AND (“Adolescent*” OR “Teen*” OR “Teenager*” OR “Youth*” OR “Female Adolescent*” OR “Male Adolescent*”) AND (“Risk Factor” OR “Health Correlates” OR “Risk Scores” OR “Risk Factor Score” OR “Population at Risk”), a more detailed search strategy see Appendix 1. The search strategy was modified accordingly for the other databases. The initial study protocol was preregistered at PROSPERO (CRD42021265885).

Inclusion criteria and data extraction

Two researchers independently assessed the titles and abstracts for potential eligibility that satisfied the above search strategy, and then full-text articles were further assessed by two researchers to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Any potential dispute was resolved through discussion. The final included articles met the following criteria: (1) the age of the samples ranged from 10 to 20 years old; (2) the study was either a case–control or cohort study, with the cohort study followed up for at least 1 year; and (3) the definition of NSSI can be clearly distinguished from suicide attempt and suicide behaviour (suicidal thoughts need to be explicitly excluded in all included articles). We compared studies involving repetitive groups in terms of publication time, sample size, article quality and whether the research involved is ongoing.

All data were independently extracted by two researchers, and the following data were collected for all articles: authors, year of publication, country, size of sample, sample age, population type (i.e., community, hospital or school-based), type of NSSI behaviour, period prevalence measure (e.g., lifetime NSSI or 12-month NSSI), and risk factors. In terms of quality assessment, the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of the articles. The full score of the scale was 9, with 0–4 points for low-quality studies, 5–6 points for moderate-quality studies, and 7–9 points for high-quality studies (Appendix 2).

Statistical analysis

Stata version 14·0 was used to pool the results from the individual studies. We used random-effects models for this study, which allow for true effects to differ across different studies when compared with fixed effects models. Considering the different sample sources, experimental methods and designs used in the included studies, we initially assumed that there was significant heterogeneity between the studies. In the process of data extraction, the odds ratio (OR) was taken as the main index. Due to the large heterogeneity in the analysis, we conducted heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses on the overall group and the subgroup, respectively.

Data were summarized as ORs, and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each outcome was used to reflect the uncertainty of point estimates. ORs = 1.0 indicated no association, ORs 〈 1.0 indicated that this factor might be a protective factor, and ORs 〉 1.0 indicated a risk factor. The heterogeneity of those variations across studies was examined with I-squared (I2) values, which provide a percentage of the proportion, with an I2 value of 0–25% representing low inconsistency, 25–75% representing moderate inconsistency, and > 75% representing high inconsistency. The research results were summarized with a common forest plot. For the publication bias of those studies, we used funnel plots for rough qualitative analysis. The Egger's test was used to quantitatively evaluate publication bias; if publication bias was shown, the trim and fill method was used to evaluate the influence of bias on the obtained results. Moreover, the subgroup analysis of different risk factors was conducted, and meta-analysis with high heterogeneity (I2 > 75%) was further evaluated by meta-regression. The variables included in the regression to consider their potential moderating effects were (1) study type (case–control/cohort study), (2) population type, (3) period prevalence measure, and (4) country.

Role of funding source

The funders of this study had no direct role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, or data interpretation. TFY, SHH and CHN critically revised and edited drafts of the paper. All of the authors had access to the data and decided to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Results of searching

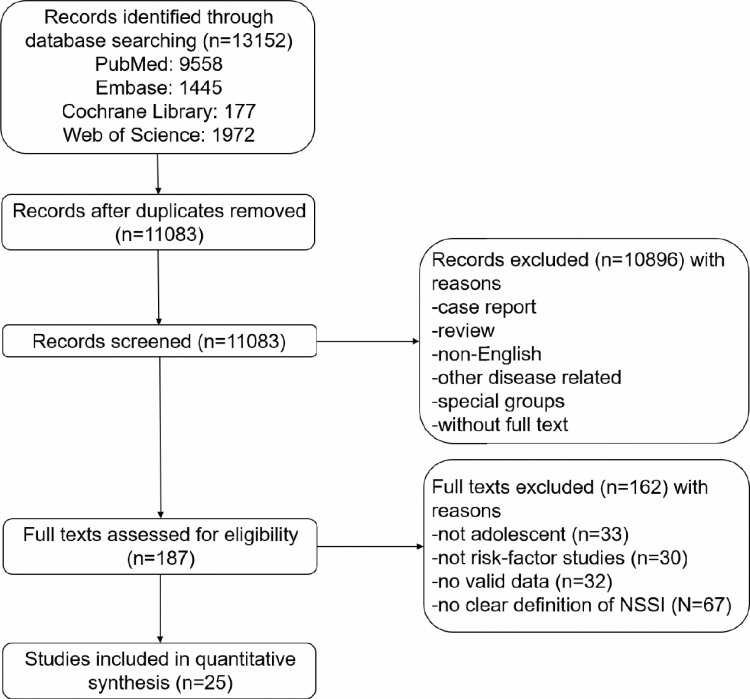

The initial database search produced 13,152 records, with a total of 11,083 records remaining after removing duplicates and manually searching. Subsequently, screenings by title, abstract and full text led to the result with 25 studies (Figure 1), after 162 articles were excluded from the meta-analysis. In total, 80 risk factors were included in this analysis, and they were divided into 7 categories: adverse childhood experiences, bullying, low health literacy, the female gender, mental disorders, physical symptoms, and problem behaviours. The pooled OR of all factors was 2·25 (95% CI, 2·04–2·48), which is highly heterogeneous (I2 = 98·3%, p = 0·000) and very significant. Therefore, different risk factors were divided into 7 categories and discussed separately (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the search for relevant references.

Table 2.

Risk factor categories.

| Risk factor | No. of studies | Heterogeneity | Pooled OR | 95% CI | Pooled effect size test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I² (%) | tau² | Z | P | ||||

| Adverse Childhood Experiences | 15 | 94·9% | 0·286 | 2·49 | 1·85–3.34 | 6·056 | 0·000 |

| Bullying | 7 | 95·5% | 0·237 | 1·98 | 1·33–2·95 | 3·348 | 0·001 |

| Low Health Literacy | 2 | 95·6% | 0.044 | 2·20 | 1·63–2·96 | 5·182 | 0·000 |

| Female Gender | 8 | 20·3% | 0·012 | 2·89 | 2·43–3·43 | 12·132 | 0·000 |

| Mental Disorders | 21 | 99·2% | 0·123 | 1·89 | 1·60–2·24 | 7·519 | 0·000 |

| Physical Symptoms | 5 | 92·8% | 0·640 | 2·85 | 1·36–5·97 | 2·771 | 0·006 |

| Problem Behaviours | 21 | 91·8% | 0·099 | 2·36 | 2·00–2·77 | 10·274 | 0·000 |

| Overall | 80 | 98·3% | 0·154 | 2·25 | 2·04–2·48 | 16·125 | 0·000 |

Characteristics of the included studies

Of the twenty-five studies eventually included, eighteen were case–control studies, and the remaining seven were cohort studies. Eight studies were conducted in China, seven in the US, three in Canada, and one each in Australia, Singapore, Iran, Turkey, Norway, South Korea and three European cities. The number of NSSI samples included in the studies ranged from 26 to 20,416. In addition, most of the articles used the self-report method to conduct NSSI classification, and only 2 articles used interviews (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author | Year | (Mean) age | Population Type | Risk Factors | NSSI definition | Interview v. Self-Report | period | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrews et al.32 | 2013 | 12 to 18 | School | Female, Birth Outside of Australia, No Religious or Spiritual, Psychological Distress | NSSI | Self-report | / | 7 |

| Baiden et al.33 | 2017 | 12 to 18 | School | Female, Number of Children Abuse, Bullying Victimization, Depression | NSSI | Self-report | / | 6 |

| Bandel et al.34 | 2018 | 13 to 17 | Community | Depressive Symptoms, Insomnia Symptoms (SCI) | NSSI | Self-report | Past 6 months | 6 |

| Cox et al.35 | 2012 | M = 13.7 (3.9) | Community | Diagnosis of Major Depression, Current Suicidal Ideation | NSSI | Interview and Questionnaire | / | 8 |

| Giletta et al.36 | 2011 | 14 to 19 | School | Depressive Symptoms, Family Loneliness, Peer Victimization, Smoking, Marijuana Use | NSSI | Self-report | 1 year (I/N), 6 months (The US) | 5 |

| Gromatsky et al.37 | 2019 | 13 to 15 | Community | Parental Substance Abuse, Avoidance | NSSI | Self-report | Lifetime | 5 |

| Jeong et al.38 | 2021 | 12 to 17 | School | Female, Middle School, Gaming Disorder, Lower Economic Status | NSSI | Self-report | Past 12 Months | 6 |

| Khoubaeva et al.39 | 2021 | 13 to 30 | Hospital | Sex, BD-II/-NOS Subtype, Higher Most Severe Lifetime Depression Scores, Greater Emotion Dysregulation | NSSI | Interview | / | 5 |

| Lanzillo et al.40 | 2021 | 12 to 17 | Hospital | Any Form of Cyberbullying | NSSI | Self-report | / | 5 |

| Larsson et al.41 | 2008 | 13.7 to 17 | Community | Function Impairment Due to Somatic Handicap, Friend Had Attempted Suicide, Smoking, Sex, High MFQ Score | Self-harm | Self-report | Past 12 months | 6 |

| Lauw et al.42 | 2018 | 13 to 19 | Hospital | Female Gender, Depressive Disorders, Alcohol Use, Forensic History | More frequent NSSI | Self-report | / | 5 |

| Li et al.14 | 2019 | M = 15.36 (1.79) | School | Low HL, Problem Mobile Phone Use (PMPU) | NSSI | Self-report | Previous 12 months | 5 |

| Liu et al.43 | 2016 | 11 to 18 | School | Frequent Nightmares, Poor Sleep Quality | NSSI | Self-report | Past 12 months | 6 |

| Monto et al.44 | 2018 | 14 to 18 | School | Sad 2 weeks, Suicide Attempt, Forced to Have Sex, Electronically Bullied | NSSI | Self-report | Past 12 months | 5 |

| Nemati et al.45 | 2020 | 15 to 18 | School | Psychological Functioning of The Family, Perceived Social Support | NSSI | Self-report | / | 6 |

| Stewart et al.46 | 2014 | 14 to 18 | Hospital | Female, 3 or More Psychiatric Admissions, Sexual Abuse, Intentional Misuse of Prescription Medications, Alcohol, Mood disorder, Adjustment Disorder, Personality Disorders | NSSI | Self-report | Last 12 months | 5 |

| Taliaferro et al.47 | 2018 | 14 to 17 | School | Mental Health Problem, Positive Screen for Depression, Teasing Victim, Run Away from Home, Alcohol Use | Only NSSI (one or more times in the past year) | Self-report | Past 12 months | 5 |

| Tang et al.48 | 2020 | 11 to 20 | School | Internet Addiction | More frequent NSSI | Self-report | 12 months | 6 |

| Tsai et al.49 | 2011 | 9 to 12 grades | School | Female, Running Away from Home, Suicide Attempts, History of Sexual Abuse, Drinking | DSH | Self-report | / | 7 |

| Unlu et al.50 | 2016 | 12 to 18 | Community | Revictimization, Alcohol/Substance Use | NSSI | Standard Assessment | / | 5 |

| Victor et al.51 | 2019 | 14 to 17 | Community | Depression Severity, Low Social Self-Worth, Peer Victimization | NSSI | Self-report | Past 12 months | 7 |

| Wan et al.52 | 2018 | 10 to 20 | School | High ACEs Scores, Low Social Support | NSSI | Self-report | 12 months | 6 |

| Wang et al.53 | 2020 | M = 14.59 (1.45) | School | Weekdays internet Use≥2 h, Mobile Phone Use 1–2 h, Weekends internet Use≥3 h, Mobile Phone Use≥4 h | NSSI | Self-report | Lifetime/Last-year | 7 |

| Xie et al.54 | 2021 | 10 to 20 | School | Opioid Misuse, Sedative Misuse | NSSI | Self-report | Past 12 months | 5 |

| Zhang et al.55 | 2016 | 11 to 19 | School | Psychological Symptoms, Low HL | NSSI | Self-report | Past 12 months | 7 |

Note: HL, health literacy; MFQ, The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; BD bipolar disorder.

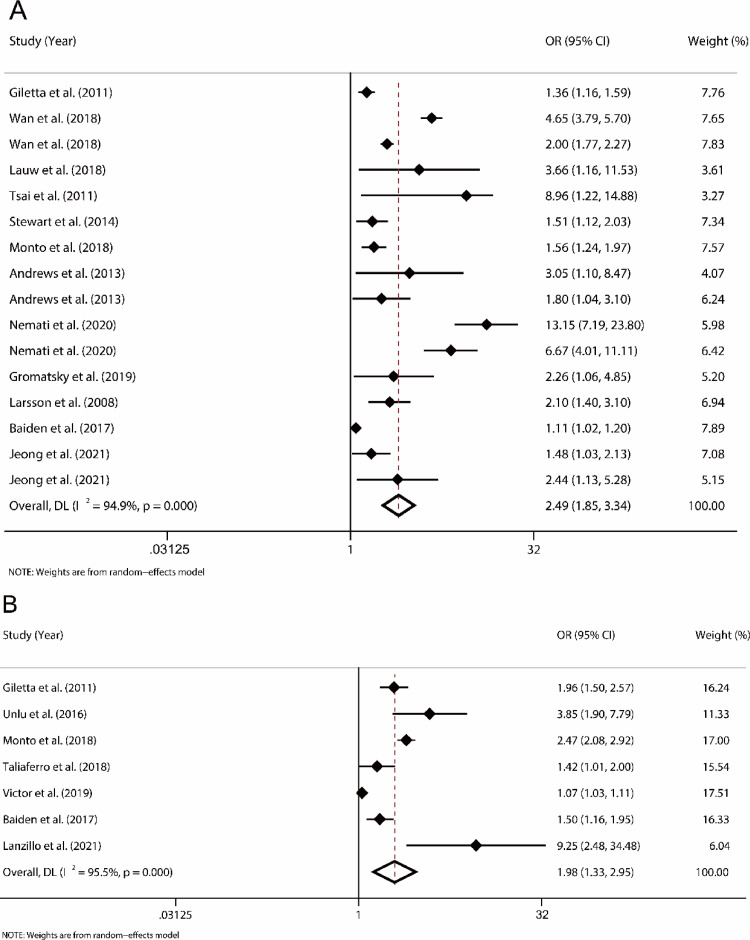

Adverse childhood experiences

A total of 16 factors associated with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) were attributed to this category, which included high adolescent childhood experience scores, family loneliness, low social support, parents’ substance abuse, forced sexual behaviours, forensic history, history of sexual abuse, sexual abuse, perceived social support, birth outside of the country, no religious or spiritual context, psychological functioning of the family, friend had attempted suicide, episodes of childhood abuse, middle school and lower economic status. Although this category included society, family, school, and other aspects, in terms of combined outcomes, adolescents with ACEs were more likely to have NSSI behaviours than healthy adolescents (OR, 2·49; 95% CI, 1.85–3·34), although there was a large heterogeneity observed (I2= 94·9%; P < 0·000) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plots for adverse childhood experiences and bullying

A, Forest plot of effect size and 95% CI of adverse childhood experiences (random effects model); B, Forest plot of effect size and 95% CI of bullying (random effects model). The diamonds represent individual studies and pooled effect sizes, and the lines represent 95% confidence intervals for each main study. OR = odds ratio.

Bullying

A total of 7 studies covered bullying, with the main categories being traditional bullying and cyberbullying. The pooled OR (OR, 1·98; 95% CI, 1·33–2·95) showed that bullying was a relatively weak risk factor in all categories. At the same time, the studies on bullying had great heterogeneity (I2 = 95·5%; P = 0·001) (Figure 2).

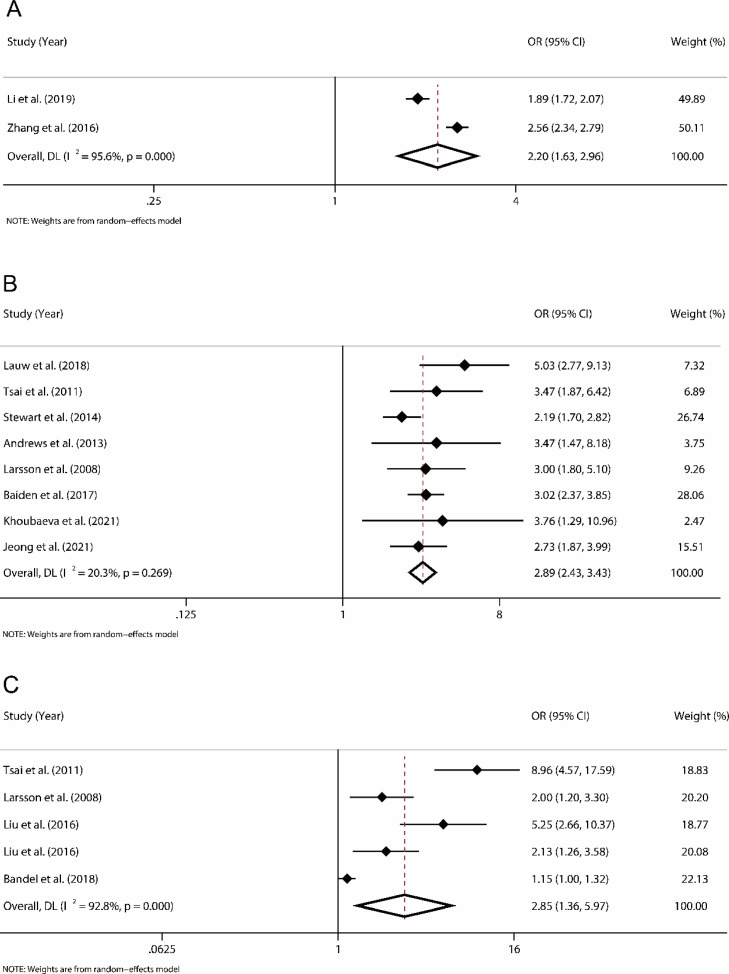

Low health literacy

Health literacy is a person's ability to obtain, understand and process basic health information and make corresponding health decisions.14 There were two studies involving health literacy from China, and the combined results were significantly different (OR, 2·20; 95% CI, 1·63–2·96). However, due to the small number of included studies, the results may lack reliability to an uncertain extent (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for low health literacy, female gender, and physical symptoms

A, Forest plot of effect size and 95% CI of low health literacy (random effects model); B, Forest plot of effect size and 95% CI of female gender (random effects model); C, Forest plot of effect size and 95% CI of physical symptoms (random effects model). The diamonds represent individual studies and pooled effect sizes, and the lines represent 95% confidence intervals for each main study. OR = odds ratio.

Female gender

Eight studies reported on gender. Most studies indicated that female adolescents were more likely to have NSSI than male subjects. Furthermore, the sex difference may decrease with age, and the merged result (OR, 2·89; 95% CI, 2·43–3·43) was significant with a greater impact. The heterogeneity of the studies on gender was low (I2 = 20·3%; P < 0·001) (Figure 3).

Physical symptoms

Five risk factors were mentioned in this category, which included disabilities and sleep problems. Different from our expectation, the effect of physical problems on NSSI behaviours was significant (OR, 2·85; 95% CI, 1·36–5·97). However, at the same time, due to the low number of studies and high heterogeneity (I2 = 92·8%, p < 0·001), this result may be unstable (Figure 3).

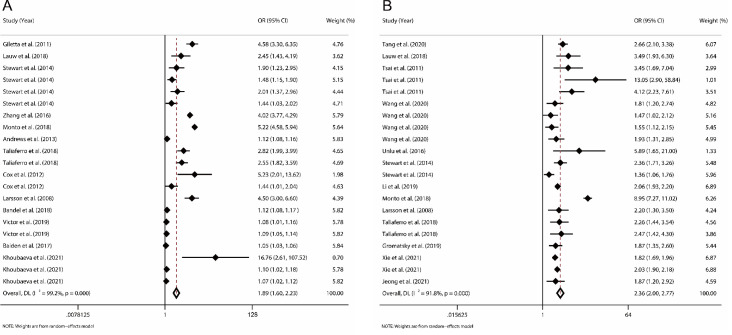

Mental disorders

Mental disorders included 21 factors, amongst which depression and anxiety symptoms were the most common, while personality disorders, adaptation disorders, emotional scale scores and psychological symptoms were also included. The NSSI patients were recruited in hospitals, communities, and school groups. In terms of the pooled OR (OR, 1·89; 95% CI, 1·60–2·24), the impact of mental disorders was not as strong as we expected, and the results had some heterogeneity (I2 = 99·2%; P = 0·001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot for mental disorders and problem behaviours

A, Forest plot of effect size and 95% CI of mental disorders (random effects model); B, Forest plot of effect size and 95% CI of problem behaviours (random effects model). The diamonds represent individual studies and pooled effect sizes, and the lines represent 95% confidence intervals for each main study. OR = odds ratio.

Problem behaviours

Problem behaviour refers to behaviours that may be not conducive to the future development of young people. In the merged results, the pooled OR was 2·36 (95% CI, 2·00–2·77; I2 = 91·8%, P = 0·001). Twenty-one factors were included in this category, including internet addiction, alcohol/substance use, smoking, problematic mobile phone use, having run away from home, suicide attempt, internet/mobile phone abuse, intentional misuse of prescription medications, avoidance, opioid misuse, sedative misuse, and gaming disorder (Figure 4).

Publication bias

Except for the female gender, the distribution of scattered points in the funnel plot was asymmetric, suggesting potential publication bias. The funnel plot, however, provided a relatively symmetrical pattern, indicating that the possibility of publication bias was slight. This distribution did not indicate that more extreme results were selectively accepted for publication. Since the studies on low health literacy were too few to complete the Egger test, no publication bias analysis was performed. We then performed Egger's test on other categories and found that the results of ACEs, bullying, mental disorders and problem behaviours were significantly different, which may be due to publication bias. By supplementing the virtual literature with the trim and fill method, it was found that the results of ACEs and problem behaviours were very stable, indicating that publication bias had little effect on the results. In contrast, the results of bullying and mental disorders were not stable, indicating that the influence of publication bias on the results was present, and more studies in this area are needed.

We also carried out meta-regressions with study type, population type, period prevalence measures, country of study, and literature quality as variables to further explore the possible sources of heterogeneity. It was found that the study type (b = 1·038, p = 0·795) and study quality (b = 0·959, p = 0·796) were not important sources of heterogeneity. Population type (b = 1·196, p = 0·042), period prevalence measures (b = 0·753, p = 0·003), and country of study (b = 1·053, p = 0·029) may be sources of heterogeneity. We conducted subgroup analyses based on these three possible sources. However, the subgroup heterogeneity of a small number of studies was not significant, while the subgroup heterogeneity of a large number of studies remained high. This suggests that these three variables may regulate the generation of heterogeneity, but they themselves were not important sources of heterogeneity.

Discussion

This meta-analysis was based on eighteen case–control studies and seven cohort studies, with an overall sample of more than 55,596 people with NSSI behaviour. The pooled data suggested that the female gender, physical symptoms, ACEs, problem behaviours, low health literacy, bullying and mental disorders were potential risk factors for NSSI. We also note that the included studies were highly heterogeneous and had a certain publication bias.

Our study was the first comprehensive meta-analysis focusing on NSSI behaviour in adolescents, given that NSSI is highly prevalent in adolescence and can lead to irreparable consequences.15,16 Compared with adults, the risk factors for NSSI in adolescents are different. Adults are more likely to be affected by previous NSSI experiences and emotional disorders associated with NSSI behaviour.13 In contrast, NSSI in adolescents is associated with sleep problems and ACEs.

The results derived from studies with less heterogeneity showed that female adolescents were more prone to have NSSI behaviour than their male counterparts, which is in line with previous community-based studies.12 In addition, there is also evidence that male and female adolescents may choose different modes of NSSI. Women are more likely to cut the skin, scratch, and bite, while men are more likely to hit, beat and burn.17 There are also gender differences in terms of self-reported causes of NSSI. Female adolescents adopt self-injury behaviour mainly for regulating emotions and self-control. Male teenagers, however, are more prone to impulsive pleasure.18 In the face of stressors and negative emotions, men are more likely to initiate strategies to solve problems, whereas women are more likely to focus on emotionally directed coping strategies.19 However, emotional strategies are often maladaptive, and females also have a greater risk for internalization difficulties.20 Adolescent females are more likely to report internalization symptoms than males leading to mental illness (such as depression and anxiety), while males have a greater prevalence of externalization disorders (extraverted aggression and substance abuse).21,22 The high incidence of emotional disorders amongst women may contribute to the high incidence of NSSI in women; in addition, women may be more dependant on NSSI behaviour to release their negative emotions.23

Low health literacy and mental disorders were also risk factors for NSSI, although the relevant studies were highly heterogeneous. It was found that emotion dysregulation was associated with a higher risk for NSSI amongst individuals across settings. In adolescence, there is limited efficacy of adaptive internal emotion regulation.24,25 Therefore, during the process of dealing with negative emotions, teenagers lack effective coping strategies and are more likely to engage in NSSI behaviour for relief. This can result in more serious psychosocial consequences (shame, guilt, peer discrimination, and teacher and parental criticism) and self-criticism, resulting in impaired social relations and negative emotions, creating a vicious circle. It was also found in female adolescents with depression that the activation of the left frontal cortex related to positive emotions was reduced, while it was the opposite in healthy groups.11 We speculate that frontal alpha asymmetry may also exist in adolescents with NSSI, which needs to be verified.

Adverse childhood experiences, bullying and problem behaviours are important risk factors, which include the negative impact of family, school, and society on adolescents. These factors may cause short-term physical and psychological health damage to individuals and adversely affect lifelong health, increasing the overall medical burden on society.26 Repeated exposure to such adverse stress events in childhood and adolescence may lead to the deviation of development trajectory, increase the occurrence of emotional symptoms, affect the development of cognitive function and the formation of personality characteristics. Thus, preventing ACEs can, to a large extent, reduce the incidence of health hazards.27, 28, 29 In terms of biological mechanisms, adverse experiences may have a negative impact on adolescents, such as brain structural changes, the HPA axis and circulating inflammatory cytokines.30 A cohort study found that the higher the ACEs score, the higher the risk of self-injury at 16 years old; however, the psychological and biological mechanisms between ACEs and NSSI still require further study.31

There were some limitations to the present study. First, almost all studies used self-report as the standard of classification. Most researchers and clinicians classified NSSI behaviours after excluding any intent to die or commit suicide. Therefore, a more reliable classification method is needed to distinguish between NSSI and suicide attempts. Second, sample representativeness, sample type, period prevalence measure and other factors may influence the results. The number of studies of some risk factors was too small for meta-analysis, and hence, the interpretation of results and publication bias are still limited by the small study numbers. Third, all the articles included both clinical and nonclinical samples, and the risk factors for NSSI behaviours in these groups may be different. Finally, the present study selected both case–control studies and cohort studies; more cohort studies with longer follow-up times are required to validate the present findings.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis identified potential risk factors for NSSI behaviour in adolescents. Such findings may help develop strategies for the early recognition and prevention of adolescent NSSI.

Contributors

Yu-Jing Wang: Methodology, Formal analysis and investigation, Data curation, Writing - Original draft preparation

Xi Li: Methodology, Formal analysis and investigation, Data curation

Dong-Wu Xu: Supervision, Writing - Review and editing, Funding acquisition

Shaohua Hu: Supervision, Writing - Review and editing, Funding acquisition

Ti-Fei Yuan: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - Review and editing, Funding

Chee H Ng: Writing, review and editing

Funding acquisition All authors have read the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statements

Extracted data are from published studies and are available in the paper, and the dataset are not subject to embargo or restrictions.

Funding

NSFC grant (81,822,017), National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFA0113600), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (No. LY19H090015), Shenzhen-Hong Kong Institute of Brain Science - Shenzhen Fundamental Research Institutions (NYKFKT20190020), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission - Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (20,181,715), Social Science Foundation of China (BIAl80167).

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101350.

Contributor Information

Dong-Wu Xu, Email: xdw@wmu.edu.cn.

Shaohua Hu, Email: dorhushaohua@zju.edu.cn.

Ti-Fei Yuan, Email: ytf0707@126.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Nock M.K. Self-injury. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:339–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bresin K., Gordon K.H. Endogenous opioids and nonsuicidal self-injury: a mechanism of affect regulation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(3):374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenn C.R., Klonsky E.D. Nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: an empirical investigation in adolescent psychiatric patients. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42(4):496–507. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.794699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swannell S.V., Martin G.E., Page A., Hasking P., St John N.J. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(3):273–303. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richmond-Rakerd L.S., Caspi A., Arseneault L., et al. Adolescents who self-harm and commit violent crime: testing early-life predictors of dual harm in a longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(3):186–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18060740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson P.O., Qiu T., Neufeld S., Jones P.B., Goodyer I.M. Sporadic and recurrent non-suicidal self-injury before age 14 and incident onset of psychiatric disorders by 17 years: prospective cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(4):222–226. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2017.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mars B., Heron J., Crane C., et al. Clinical and social outcomes of adolescent self harm: population based birth cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g5954. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne S., Morgan S., Fitzpatrick C., et al. Deliberate self-harm in children and adolescents: a qualitative study exploring the needs of parents and carers. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;13(4):493–504. doi: 10.1177/1359104508096765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tschan T., Ludtke J., Schmid M., In-Albon T. Sibling relationships of female adolescents with nonsuicidal self-injury disorder in comparison to a clinical and a nonclinical control group. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2019;13:15. doi: 10.1186/s13034-019-0275-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan K., Fox K.R., Prinstein M.J. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):842–849. doi: 10.1037/a0029429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graae F., Tenke C., Bruder G., et al. Abnormality of EEG alpha asymmetry in female adolescent suicide attempters. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40(8):706–713. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawton K., Saunders K.E.A., O'Connor R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012:379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox K.R., Franklin J.C., Ribeiro J.D., Kleiman E.M., Bentley K.H., Nock M.K. Meta-analysis of risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;42:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D., Yang R., Wan Y., Tao F., Fang J., Zhang S. Interaction of health literacy and problematic mobile phone use and their impact on non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(13):2366. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodav O., Levy S., Hamdan S. Clinical characteristics and functions of non-suicide self-injury in youth. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(8):503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olfson M., Wall M., Wang M., et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bresin K., Schoenleber M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;38:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitlock J., Muehlenkamp J., Purington A., et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury in a college population: general trends and sex differences. J Am Coll Health. 2011;59(8):691–698. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.529626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melendez J.C., Mayordomo T., Sancho P., Tomas J.M. Coping strategies: gender differences and development throughout life span. Span J Psychol. 2012;15(3):1089–1098. doi: 10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n3.39399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S., Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo D., Ahluwalia A., Potenza M.N., Sinha R. Gender differences in neural correlates of stress-induced anxiety. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95(1–2):115–125. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendelson T., Kubzansky L.D., Datta G.D., Buka S.L. Relation of female gender and low socioeconomic status to internalizing symptoms among adolescents: a case of double jeopardy? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1284–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.033. (1982) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox K.R., Millner A.J., Mukerji C.E., Nock M.K. Examining the role of sex in self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young K.S., Sandman C.F., Craske M.G. Positive and negative emotion regulation in adolescence: links to anxiety and depression. Brain Sci. 2019;9(4):76. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9040076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff J.C., Thompson E., Thomas S.A., et al. Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;59:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellis M.A., Hughes K., Ford K., Ramos Rodriguez G., Sethi D., Passmore J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(10):e517–e528. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selous C., Kelly-Irving M., Maughan B., Eyre O., Rice F., Collishaw S. Adverse childhood experiences and adult mood problems: evidence from a five-decade prospective birth cohort. Psychol Med. 2020;50(14):2444–2451. doi: 10.1017/S003329171900271X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong J., Chan R.C.K. Early maladaptive schemas as mediators between childhood maltreatment and later psychological distress among Chinese college students. Psychiatry Res. 2018;259:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellis M.A., Hughes K., Leckenby N., et al. Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviours in young adults: surveys in eight eastern European countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(9):641–655. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.129247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhlman K.R., Geiss E.G., Vargas I., Lopez-Duran N.L. Differential associations between childhood trauma subtypes and adolescent HPA-axis functioning. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;54:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell A.E., Heron J., Gunnell D., et al. Pathways between early-life adversity and adolescent self-harm: the mediating role of inflammation in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(10):1094–1103. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrews T., Martin G., Hasking P., Page A. Predictors of onset for non-suicidal self-injury within a school-based sample of adolescents. Prev Sci. 2014;15(6):850–859. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baiden P., Stewart S.L., Fallon B. The mediating effect of depressive symptoms on the relationship between bullying victimization and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: findings from community and inpatient mental health settings in Ontario, Canada. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandel S.L., Brausch A.M. Poor sleep associates with recent nonsuicidal self-injury engagement in adolescents. Behav Sleep Med. 2020;18(1):81–90. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2018.1545652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox L.J., Stanley B.H., Melhem N.M., et al. A longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury in offspring at high risk for mood disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(6):821–828. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giletta M., Scholte R.H., Engels R.C., Ciairano S., Prinstein M.J. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: a cross-national study of community samples from Italy, the Netherlands and the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197(1–2):66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gromatsky M.A., He S., Perlman G., Klein D.N., Kotov R., Waszczuk M.A. Prospective prediction of first onset of nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(9):1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeong J.Y., Kim D.H. Gender differences in the prevalence of and factors related to non-suicidal self-injury among middle and high school students in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5965. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khoubaeva D., Dimick M., Timmins V.H., et al. Clinical correlates of suicidality and self-injurious behaviour among Canadian adolescents with bipolar disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01803-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanzillo E.C., Zhang I., Jobes D.A., Brausch A.M. The influence of cyberbullying on nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal thoughts and behavior in a psychiatric adolescent sample. Arch Suicide Res. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2021.1973630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsson B., Sund A.M. Prevalence, course, incidence, and 1-year prediction of deliberate self-harm and suicide attempts in early Norwegian school adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(2):152–165. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauw M.S.M., Abraham A.M., Loh C.B.L. Deliberate self-harm among adolescent psychiatric outpatients in Singapore: prevalence, nature and risk factors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12:35. doi: 10.1186/s13034-018-0242-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X., Chen H., Bo Q.G., Fan F., Jia C.X. Poor sleep quality and nightmares are associated with non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(3):271–279. doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monto M.A., McRee N., Deryck F.S. Nonsuicidal self-injury among a representative sample of US adolescents, 2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(8):1042–1048. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nemati H., Sahebihagh M.H., Mahmoodi M., et al. Non-suicidal self-injury and its relationship with family psychological function and perceived social support among Iranian high school students. J Res Health Sci. 2020;20(1):e00469. doi: 10.34172/jrhs.2020.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stewart S.L., Baiden P., Theall-Honey L. Examining non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents with mental health needs, in Ontario, Canada. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(4):392–409. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.824838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taliaferro L.A., McMorris B.J., Rider G.N., Eisenberg M.E. Risk and protective factors for self-harm in a population-based sample of transgender youth. Arch Suicide Res. 2019;23(2):203–221. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2018.1430639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang J., Ma Y., Lewis S.P., et al. Association of internet addiction with nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents in China. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai M.H., Chen Y.H., Chen C.D., Hsiao C.Y., Chien C.H. Deliberate self-harm by Taiwanese adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(11):e223–e226. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unlu G., Cakaloz B. Effects of perpetrator identity on suicidality and nonsuicidal self-injury in sexually victimized female adolescents. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1489–1497. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S109768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Victor S.E., Hipwell A.E., Stepp S.D., Scott L.N. Parent and peer relationships as longitudinal predictors of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury onset. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2019;13:1. doi: 10.1186/s13034-018-0261-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wan Y.H., Chen R.L., Ma S.S., et al. Associations of adverse childhood experiences and social support with self-injurious behaviour and suicidality in adolescents. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;214(3):146–152. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L., Liu X., Liu Z.Z., Jia C.X. Digital media use and subsequent self-harm during a 1-year follow-up of Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie B., Fan B.F., Wang W.X., Li W.Y., Lu C.Y., Guo L. Sex differences in the associations of nonmedical use of prescription drugs with self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among adolescents: a large-scale study in China. J Affect Disord. 2021;285:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang S.C., Tao F.B., Wu X.Y., Tao S.M., Fang J. Low health literacy and psychological symptoms potentially increase the risks of non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese middle school students. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):327. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1035-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.