Abstract

Individuals with epilepsy often experience social difficulties and deficits in social cognition. It remains unknown how disruptions to neural networks underlying such skills may contribute to this clinical phenotype. The current study compared the organization of relevant brain circuits—the “mentalizing network” and a salience-related network centered on the amygdala—in youth with and without epilepsy. Functional connectivity between the nodes of these networks was assessed, both at rest and during engagement in a social cognitive task (facial emotion recognition), using functional magnetic resonance imaging. There were no group differences in resting-state connectivity within either neural network. In contrast, youth with epilepsy showed comparatively lower connectivity between the left posterior superior temporal sulcus and the medial prefrontal cortex—but greater connectivity within the left temporal lobe—when viewing faces in the task. These findings suggest that the organization of a mentalizing network underpinning social cognition may be disrupted in youth with epilepsy, though differences in connectivity within this circuit may shift depending on task demands. Our results highlight the importance of considering functional task-based engagement of neural systems in characterizations of network dysfunction in epilepsy.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Network, Resting-state, Social brain, Functional connectivity

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is consistently found to be associated with poor interpersonal outcomes, including heightened social isolation and poorer social competence (Camfield and Camfield, 2014; Geerts et al., 2011; Hamiwka, Hamiwka et al., 2011; Jalava and Sillanpää, 1997; Kokkonen et al., 1997; Wakamoto et al., 2000). Social impairment in epilepsy has been noted to be more severe than in other groups with chronic illness (see review by Camfield and Camfield, 2007), to be independent from comorbid issues such as intellectual disability (Camfield, Camfield et al., 1993; Camfield and Camfield, 2007; Jalava and Sillanpää 1997; c. f., Wakamoto et al., 2000), and to manifest as early as childhood and adolescence (Davies et al., 2003; Drewel and Caplan, 2007; Hamiwka and Wirrell, 2009; Jakovljević and Martinović, 2006; Rantanen et al., 2009; Russ et al., 2012; Sillanpää and Cross, 2009; Tse et al., 2007). Both children and adults with epilepsy often struggle to understand others’ mental states or beliefs (mentalizing, or “theory of mind”; e.g., Broicher et al., 2012; Raud et al., 2015; Stewart et al., 2016) and to recognize nonverbal cues of emotion (emotion recognition; e.g., Benuzzi et al., 2004; Cantalupo et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 1990; Fowler et al., 2006; Golouboff et al., 2008; Laurent et al., 2014; Stewart et al., 2019a). Impediments in these rudimentary social cognitive skills are thought to be related to poorer social outcomes in individuals with epilepsy (Besag and Vasey, 2019; Kirsch, 2006; Wang et al., 2015; Yogarajah and Mula, 2019). Indeed, impairments in social cognitive abilities are a cognitive phenotype associated with epilepsy (see reviews by Besag and Vasey, 2019; Bora and Meletti, 2016; Giovagnoli and Smith, 2019; Stewart et al., 2016; Stewart et al., 2019b; Szemere and Jokeit, 2015).

Social cognition is a high-level cognitive function that requires integration of nodes across the brain into complex and interconnected networks (Kennedy and Adolphs, 2012). Parsing a social encounter requires the engagement of areas involved in perception to identify expressive or individual features in social stimuli (e.g., a face), areas involved in salience and motivational attributions, and areas relevant to executive functions (e.g., working memory, inhibitory control) to interpret social signals and guide behaviour. In ongoing interactions, this process must occur iteratively. Though several networks are likely involved in these complex functions, we focus our attention on a) the “mentalizing network” (as defined by Mills et al., 2014), including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ), the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), and the anterior temporal cortex (ATC), and b) an “amygdala network” (as defined by Kennedy and Adolphs, 2012), which centers on the amygdala and includes the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and fusiform gyrus.

These networks support several aspects of socio-emotional perception and social behaviour (Adolphs, 2002a, 2009; Dunbar, 1998; Rushworth et al., 2013). For instance, the pSTS is involved in the integration of auditory and visual stimuli (Ethofer et al., 2013; Redcay, 2008) and the perception of emotional intent in nonverbal cues (Allison et al., 2000; Engell and Haxby, 2007; Kreifelts et al., 2009). The TPJ is a key region for mentalizing ability (Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003; Saxe and Wexler, 2005), a skill that also engages the ATC (Olson et al., 2007) and mPFC (Amodio and Frith, 2016). The ATC also contributes to social memory and emotional processing (Nelson et al., 2005; Overgaauw et al., 2014; Pfeifer and Peake, 2012), whereas the mPFC is relevant to social associations and learning (Rushworth et al., 2013). The amygdala and fusiform have been heavily implicated in the processing of (emotional) faces (Adolphs, 2002a, 2002b, 2002b; Kanwisher et al., 1997). More broadly, the amygdala and OFC also play a role in the detection and interpretation of value and salience in socially relevant stimuli (Kennedy and Adolphs, 2012; Redcay and Warnell, 2018), drawing upon input from the fusiform and broader inferior temporal lobe (Adolphs, 2001) to guide social behaviour.

In typically-developing (TD) individuals, the mentalizing network becomes increasingly organized across childhood and adolescence (Blakemore, 2008; Blakemore and Mills, 2014; Burnett and Blakemore, 2009a; Nelson and Guyer, 2011; Nelson et al., 2016). Both activation in, and functional connectivity among, social brain regions like the pTPJ and mPFC during mentalizing or emotion recognition tasks change between childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood (Blakemore, den Ouden, Choudhury and Frith, 2007; Burnett and Blakemore, 2009b; Klapwijk et al., 2013; Moor et al., 2012; Overgaauw et al., 2014; Sebastian et al., 2011; Vetter et al., 2014). There is also evidence for age-related change in connectivity between the amygdala and OFC (review by Somerville et al., 2010) across adolescence. However, developmental changes in network connectivity may be disrupted in children with epilepsy (Swann, 2004).

Epilepsy is recognized as a disease of neural network dysfunction (Englot et al., 2016; Kramer and Cash, 2012; Tavakol et al., 2019). Structural abnormalities and reduced connectivity in wide-scale networks are noted across the brain, including regions distal to the presumed seizure onset point (e.g., Bettus et al., 2009; Cataldi et al., 2013; Englot et al., 2015; Mankinen et al., 2012; Tavakol et al., 2019). At rest, long-range connectivity seems particularly disrupted (Liao et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010), though localized hyper-connectivity may be preserved near the epileptic zone (e.g., the temporal lobe for patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy [TLE]; Bernhardt et al., 2011; Grassia et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2010; c. f., Zhang et al., 2010). However, while other studies have identified disruptions to a variety of other networks (e.g., default mode network [DMN], dorsal attention network, etc.; Cataldi et al., 2013; Liao et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2009), no studies have specifically focused on the functioning of networks relevant to social cognition—despite its phenotypical relevance to epilepsy.

1.1. Goals and hypotheses

The goal of the current study was to probe the functioning of two neural networks known to be involved in social cognition (i.e., the “mentalizing network” and an “amygdala network”) in youth with and without epilepsy. These networks may be particularly sensitive to disruptions during childhood and adolescence, when important developmental changes in brain structure and function are taking place. Indeed, damage to components of the social brain early in development are linked to more severe social deficits across a range of neurological and psychological disorders (Kennedy and Adolphs, 2012).

To understand the functional organization of social brain networks in pediatric epilepsy, we examined connectivity among nodes of each network both at rest and during a social cognitive task (facial emotion recognition). Few direct comparisons of task-based and resting state connectivity exist in youth (Stevens, 2016) or in individuals with epilepsy (Englot et al., 2016, but see Desai et al., 2018 for an example). This may be partially due to the different methodologies used to investigate both forms of system organization: resting state connectivity is typically assessed using whole-brain graph-theory metrics, whereas task-based networks are often characterised using seed-based methods in regions of interest. To permit a comparison of the two modalities, we opted to use a hypothesis-driven, seed-based approach limited to regions of each network in both conditions. Further, because there is evidence for changes in inter- and intra-network resting-state connectivity throughout childhood and adolescence (Fair et al., 2008; Stevens, 2016; Supekar et al., 2009; van Duijvenvoorde et al., 2016), we also conducted exploratory analyses to determine whether developmental trajectories of network connectivity differed in youth with epilepsy compared to TD youth. Understanding the functioning of neural networks underpinning social cognition is crucial to characterizing potential brain-based mechanisms of social deficits in youth with epilepsy.

We expected that youth with epilepsy would show decreases in resting-state connectivity between neural network nodes compared to TD youth, based on prior work examining networks that overlap in part with the mentalizing network or that center on the amygdala in pediatric epilepsy (e.g., the DMN and salience networks; Pittau et al., 2012; Shamshiri et al., 2017; Widjaja, Zamyadi, Raybaud, Snead and Smith, 2013a; Widjaja, Zamyadi, Raybaud, Snead and Smith, 2013b). Fewer studies have investigated task-based connectivity during social cognitive tasks in individuals with epilepsy. Two studies have reported that adults with temporal lobe epilepsy show decreased functional connectivity in frontal and (mesial) temporal regions (Broicher et al., 2012; Steiger et al., 2017) when seeing fearful faces compared to landscapes. As such, we expected that youth with epilepsy may show similarly reduced connectivity in response to emotional faces. Lastly, due to the paucity of literature on group differences in age-related changes in neural networks (Stevens, 2016; but see Ibrahim et al., 2014 for an example with resting-state data), we made no a priori hypotheses about the effect of age on connectivity in youth with or without epilepsy.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

The sample included 25 youth diagnosed with intractable focal epilepsy (16 male; aged 9–21 years, mean age = 14.28, SD = 3.36) and 41 TD youth (15 male; aged 8–19 years, mean age = 14.00, SD = 3.38). Participants with epilepsy were recruited from an epilepsy surgery center in a large Midwestern children’s hospital (United States). One additional participant with epilepsy was recruited for the study but declined to complete the task in the scanner. TD youth were recruited via a digital flyer distributed to hospital employees. Written parental consent and written participant assent/consent was obtained prior to study participation. All procedures were approved by the hospital Institutional Review Board.

Participants were 1) between the ages of 8–21 years at recruitment (to enable sufficient sample size in the group with epilepsy), 2) fluent in English, 3) had an IQ > 70 (see below for details), and 4) were deemed able to perform a functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan without sedation. Additional inclusion criteria for the epilepsy group included a primary diagnosis of focal epilepsy. Participants were excluded if they had uncorrected hearing, vision, or motor deficits that would impair task participation. Three participants with epilepsy (2 males, 1 female) were removed from analyses due to prior surgical resections. No participant had a history of traumatic brain injury, hydrocephalus, intracerebral hemorrhage, prematurity, or other conditions that would result in altered brain structure independent of epilepsy.

Handedness was assessed using the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971): 5 were left-handed (4 youth with epilepsy, 1 TD youth), 52 were right-handed (16 youth with epilepsy, 36 TD youth), and 5 reported no preference (1 youth with epilepsy, 4 TD youth). IQ was assessed in both groups using subscales of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC; Wechsler, 2014)/Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS; Wechsler, 2008). TD youth completed the matrix reasoning and vocabulary subtests during the study visit. Scaled scores for the same subtests (recorded by trained neuropsychologists as part of a clinical evaluation) were pulled from medical charts for participants with epilepsy. TD youth scored higher than youth with epilepsy for both matrix reasoning, t(61) = 2.02, p = .048, and vocabulary scores, t(61) = 5.06, p < .001 (see Table 1). Groups did not differ in age, t(61) = −0.30, p = .77, or gender distribution (Fisher’s exact test, p = .06).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Typically-developing youth | Youth with epilepsy | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 14.00 (3.38) | 14.27 (3.53) |

| Gender | 15 male (37%) | 14 male (64%) |

| Matrix reasoning | 10.90 (2.97) | 9.14 (3.87) |

| Vocabulary | 12.20 (2.60) | 8.68 (2.68) |

| Type of epilepsy | - | 4 frontal |

| 14 temporal | ||

| 3 fronto-temporal | ||

| 1 other (occipital) | ||

| Lateralization of seizure foci | - | 11 left |

| 9 right | ||

| 2 bilateral | ||

| Age of seizure onset (in years) | - | 7.11 (4.56) |

| Duration of illness (in years) | - | 7.16 (4.04) |

| Presence of MTS | - | 7 yes |

| 15 no | ||

| Number of antiseizure medications prescribed at time of scan | - | 2.00 (0.98) |

Note. For age, matrix reasoning (scaled score) and vocabulary (scaled score), age of seizure onset, duration illness, and number of antiseizure medications prescribed, values represent the mean (standard deviation). Estimates do not include youth with resections who were excluded prior to analyses.

Additional information about participants with epilepsy was obtained from their medical charts. Given known social-cognitive deficits associated with conditions that are often comorbid with epilepsy—such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism—we verified whether such diagnoses were noted in our sample. Four participants were diagnosed with ADHD at the time of scan, and none were diagnosed with autism. Moreover, two independent coders collected information about the type of epilepsy (frontal vs. temporal vs. fronto-temporal vs. other), the lateralization of seizure foci, age of seizure onset, duration of illness (computed by subtracting age of onset from age at scan, in years), presence of mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS; determined based on MR scan reports by radiologists), and the number of antiseizure medications (ASMs) prescribed at the time of study (Table 1). A third rater (M.M.) resolved any disagreements between the two when needed. Neither age at the time of scan, gender, matrix reasoning or vocabulary scores, age of onset, duration of illness, or presence of MTS differed across epilepsy types (all ps > .05), nor across right- vs. left-sided epilepsy (all ps > .05). Lateralization did not predict number of ASMs, but the type of epilepsy did, F(3, 18) = 3.78, p = .03; individuals with frontal lobe epilepsy were prescribed a greater amount of medications. Given the overall similarities across participants, youth with epilepsy were considered as one group for all primary analyses.

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Facial emotion recognition task

Following training in a mock scanner, participants completed a forced-choice emotion recognition task in the MRI scanner. Youth were asked to identify the intended emotion in pictures of adolescents’ facial expressions (conveying anger, fear, happiness, sadness, or neutral) using the above five labels. Ninety facial stimuli (45 male, 45 female) were selected from the National Institute of Mental Health’s Child Emotional Faces Picture Set (NIMH-ChEFS; Egger et al., 2011) based on expression quality, judged by two research assistants. This task has previously been used to probe neural responses to teenage faces in TD youth (Morningstar et al., 2019) and youth with epilepsy (Morningstar et al., 2020).

Each trial of the task was composed of stimulus presentation (1 s in duration) followed by a 5-s response period. Stimuli were presented in an event-related design with a jittered inter-trial interval between 1 and 8 s (mean 4.5s). A fixation cross was presented during the inter-trial intervals and a pictogram of response labels was shown during the response period. All stimuli were viewed on a computer monitor at the head of the magnet bore, via a mirror attached to the head coil. Responses were recorded on Lumina handheld response devices inside the scanner. The task was split into three 6-min runs of 30 faces, each containing a balanced number of stimuli per emotion type (presented in a pseudorandomized order).

2.2.2. Resting state

The resting-state protocol lasted 6 min 15 s. Participants were presented with a fixation cross and instructed to relax and look at the cross for the duration of data collection. Resting state data were acquired after the task protocol in all but 1 participant. Eight participants (4 youth with epilepsy and 4 TD youth) did not complete the resting-state portion of the scan protocol.

2.3. Image acquisition and processing

Due to scanner upgrade during data collection, MRI data were collected on 2 Siemens 3T scanners running identical software, using standard 32- and 64-channel head coil arrays. The imaging protocol included three-plane localizer scout images and a T1-weighted anatomical scan covering the whole brain (MPRAGE). Imaging parameters for the MPRAGE were: 1 mm isometric voxel dimensions, 176 sagittal slices, repetition time (TR) = 2200–2300 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.45–2.98 ms, field of view (FOV) = 248–256 mm. Functional MRI data were acquired with echo planar imaging (EPI) acquisitions, with a voxel size of 2.5 × 2.5 × 3.5–4 mm, and the phase-encoding axis oriented in the anterior-posterior direction. Parameters were: TR = 1500 ms, TE = 30–43 ms, FOV = 240 mm, flip angle = 30 (90 for resting-state scans). Dummy data were collected for 9.2s prior to task onset.

EPI images were preprocessed and analyzed in AFNI, version 18.1.05 (Cox, 1996). Functional task images were corrected to the first volume, realigned to the AC/PC line, and coregistered to the T1 anatomical image. Images were subsequently normalized non-linearly to the Talairach template. Following this, data were spatially smoothed with a Gaussian filter (FWHM, 6 mm kernel). Voxel-wise signal was scaled to a mean value of 100 within each task run, with a maximum scaled value of 200. Finally, volumes in which at least 10% of the voxels were signal outliers or contained movement greater than 1 mm between volumes were censored. Movement below this threshold (6 affine directions and the 1st order derivatives), along with scanner drift per run, was subsequently included as a nuisance regressor (see below). In addition, one participant with epilepsy was removed from the sample entirely due to excessive motion during the task (62% of volumes censored).

Resting-state functional images were preprocessed using FMRIB’s Software Library (FSL, version 6.01; Jenkinson et al., 2012). Skull stripping was performed using FSL’s Brain Extraction Tool (BET) and volumes were realigned to the middle volume (using FSL’s MCFLIRT tool) to correct for gross head motion. Data were co-registered to the T1 anatomical image before being linearly transformed (12 degrees of freedom) to the Talairach template. Data were then spatially smoothed using a Gaussian filter (FWHM, 6 mm). An Independent Components Analysis-based strategy for Automatic Removal of Motion Artifacts (ICA-AROMA; Pruim et al., 2015) was performed to classify and remove motion artifacts from the data. The resulting denoised data were then preprocessed similarly to the task data: using AFNI, data were corrected to the first volume, realigned to the AC/PC line, co-registered to the T1 anatomical image, and then normalized non-linearly to the Talairach template. Signal de-spiking was conducted using AFNI’s 3dDespike tool with default settings, and a temporal bandpass filter was applied with a frequency range of 0.01–0.1. Voxel-wise signal was scaled to a mean value of 100 within each task run, with a maximum scaled value of 200. Volumes with more than 0.5 mm between volumes were censored (applied to only 1 participant); movement below this threshold (6 affine directions and the 1st order derivatives) was included as a nuisance regressor in analyses. The final sample used for resting-state analyses contained 36 TD youth and 17 youth with epilepsy. The final sample used for task-based connectivity analyses included 41 TD youth and 21 youth with epilepsy.1

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Creation of region of interest (ROI) masks

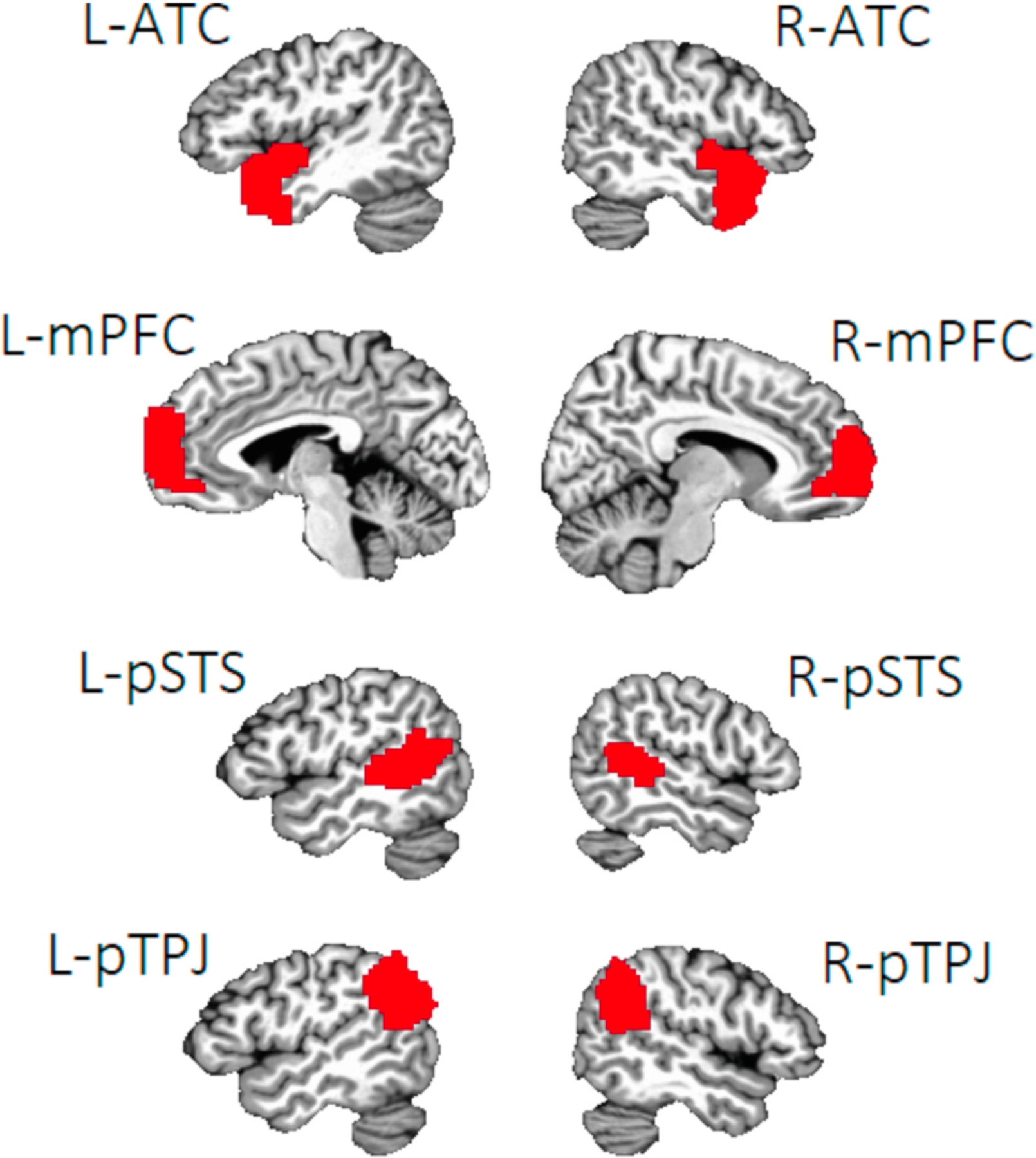

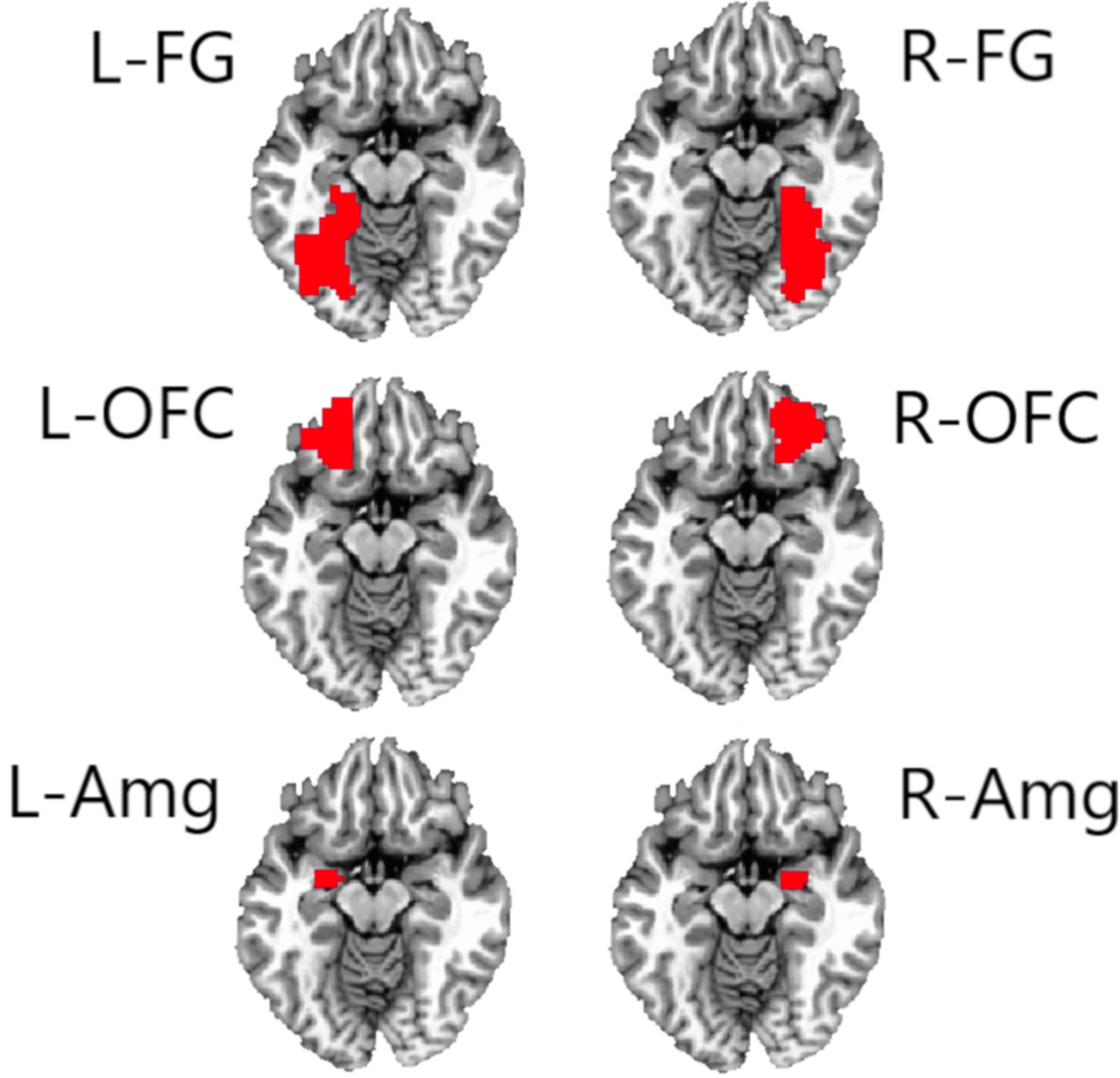

Cortical surface annotations for the mentalizing network ROIs (based on Mills et al., 2014) were downloaded from a publicly-available database (https://figshare.com/articles/Social_Brain_Freesurfer_ROIs/726133). These ROIs represent the anterior temporal cortex (ATC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) in Brodmann area 10, the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) and the posterior temporo-parietal junction (pTPJ), in both the right (R) and left (L) hemispheres. For the amygdala network, the R and L fusiform gyrus (FG) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) ROIs were defined based on the Destrieux atlas in Freesurfer (using the G_oc_temp_lat-fusifor and S_orbital_H_shaped annotations, respectively). Volumetric R and L amygdala ROIs were defined using the Talairach-Tournoux atlas in AFNI. For cortical surface annotations (i.e., all but the amygdala ROIs), we extracted volumetric ROIs by mapping the above masks to the Talairach-Tournoux template brain. Masks were dilated by 3 voxels and eroded by 1 voxel to fill holes inside the ROI. The resulting masks’ alignment to the template was confirmed visually. ROIs for each network are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Note. Regions of interest in the mentalizing network. Regions of interest were based on those outlined in Mills et al. (2014). L = left, R = right. ATC = anterior temporal cortex, mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex, pSTS = posterior superior temporal sulcus, pTPJ = posterior temporo-parietal junction.

Fig. 2.

Note. Regions of interest in the amygdala network. Regions of interest were based on those described in Kennedy and Adolphs (2012). L = left, R = right. FG = fusiform gyrus, OFC = orbitofrontal cortex, Amg = amygdala.

2.4.2. Functional connectivity at rest

Resting-state functional connectivity (RS-FC) was analyzed using a seed-based approach, with the AFNI tool 3dGroupIncorr (Cox, 1996). RS-FC was determined by correlating the mean time series of all voxels in each seed region (i.e., each ROI defined above) against the time series of all other voxels of the brain. A two-sample t-test was computed using the Fisher’s Z transformed correlation data, comparing connectivity with each seed by Group (TD youth vs. youth with epilepsy). Age was included as a variable of interest in the model. T-statistics were derived for the main effect of Group and for the interaction of Group × Age. The resulting statistical parametric maps were then masked to include the non-seed ROIs in each of the two networks; this procedure was implemented to focus only on the interconnectivity of the mentalizing or amygdala networks defined above.

We applied the false discovery rate correction factor to all analyses. For each mask (i.e., all ROIs within a network except for the seed region), a cluster-size threshold correction was generated using the spatial autocorrelation function of 3dclustsim (AFNI), based on Montecarlo simulation with sample-specific smoothing estimates (Cox et al., 2016), two-sided thresholding, and first-nearest neighbor clustering, at α = 0.05 and p < .001. Within both networks, this procedure yielded a cluster threshold of 5 voxels (at p < .001) for all seed regions. These cluster-size corrections were applied to all model results.

2.4.3. Functional connectivity during task (gPPI)

We conducted generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI) analyses (McLaren et al., 2012) to probe the functional connectivity of the mentalizing and amygdala networks. First, we estimated event-related response amplitudes at the subject level within each ROI defined above. Subject-level models included 1) regressors for the presentation of the facial emotion stimulus (1s in duration) convolved with the hemodynamic response function, contrasted to an implicit baseline (all non-stimulus periods), 2) regressors for emotion type (5 levels: anger, fear, happiness, sadness, neutral) to control for possible emotion-specific differences in neural activation, and 3) nuisance regressors for motion (6 affine directions and their 1st order derivatives) and scanner drift per run (3rd polynomial). We controlled for potential emotion-specific effects on activation rather than include it as a factor of interest to maximize comparability between analyses for functional and resting-state connectivity; in addition, previous analyses (Morningstar et al., 2020) indicated that there were no emotion-specific differences in activation across groups. Second, we performed a group-level multivariate model for each seed region (3 dMVM in AFNI; Chen et al., 2014). These models tested the effect of Group (2 levels: TD youth vs. youth with epilepsy) and Age (in years, continuous variable) on functional connectivity with each ROI. From these models, we derived F-statistics for the main effect of Group and for the interaction of Group × Age. Third, as in RS-FC analyses, we masked the resulting statistical parametric maps to only include the other non-seed regions in the network.

As with RS-FC analyses, we applied AFNI’s 3dClustSim as a false discovery rate correction using the parameters detailed above. Within the mentalizing network, this procedure yielded a corrected cluster threshold of 12 voxels for analyses using the right or left ATC as seed regions, 10 voxels for the right or left mPFC seed regions, and 11 voxels for right or left pSTS and pTPJ regions. Within the amygdala network, this procedure yielded a cluster threshold of 11 voxels for all seed regions. These cluster-size corrections were applied to all model results. Resulting clusters were identified at their center of mass using the Talairach-Tournoux atlas. Mean estimates of the connectivity between the seed and target clusters were extracted for follow-up analyses (e.g., simple-slopes tests to probe significant interactions).

2.4.4. Relationship between task-based connectivity and task performance

Previous work examining this sample’s accuracy in recognizing facial emotions during the task demonstrated that youth with epilepsy were overall less accurate than TD youth (Morningstar et al., 2020), with no emotion-specific group differences in performance. We conducted secondary exploratory analyses to examine the relationship between participants’ facial emotion recognition accuracy and functional connectivity during the task. Due to spurious scanner signals that interfered with the recording of some participants’ responses, task performance data was available for 20 TD youth and for 16 youth with epilepsy. Accuracy was indexed using the unbiased hit rate (Hu), a measure of accuracy that corrects for response biases (Wagner, 1993). A value of Hu was computed for each emotion type, with values ranging from 0 (no hit rates, all false alarms) to 1 (all hit rates, no false alarms). Hu values were arcsine-transformed (Wagner, 1993) and subsequently averaged to obtain one value representing overall accuracy in the task. Both TD youth (mean Hu = 2.47, SD = 0.26) and youth with epilepsy (mean Hu = 2.05, SD = 0.37) performed above chance levels in the task (see details in Morningstar et al., 2020).

Where group differences in task-based connectivity were noted (detailed in section 3.2), we examined whether such differences were related to participants’ task accuracy. To do so, we computed partial correlations between Hu and functional connectivity between relevant ROIs, controlling for age.

3. Results

3.1. Group differences in functional connectivity at rest

There were no main effects of Group, nor interactions of Group × Age, on resting-state connectivity for any seed within either the mentalizing or the amygdala network.

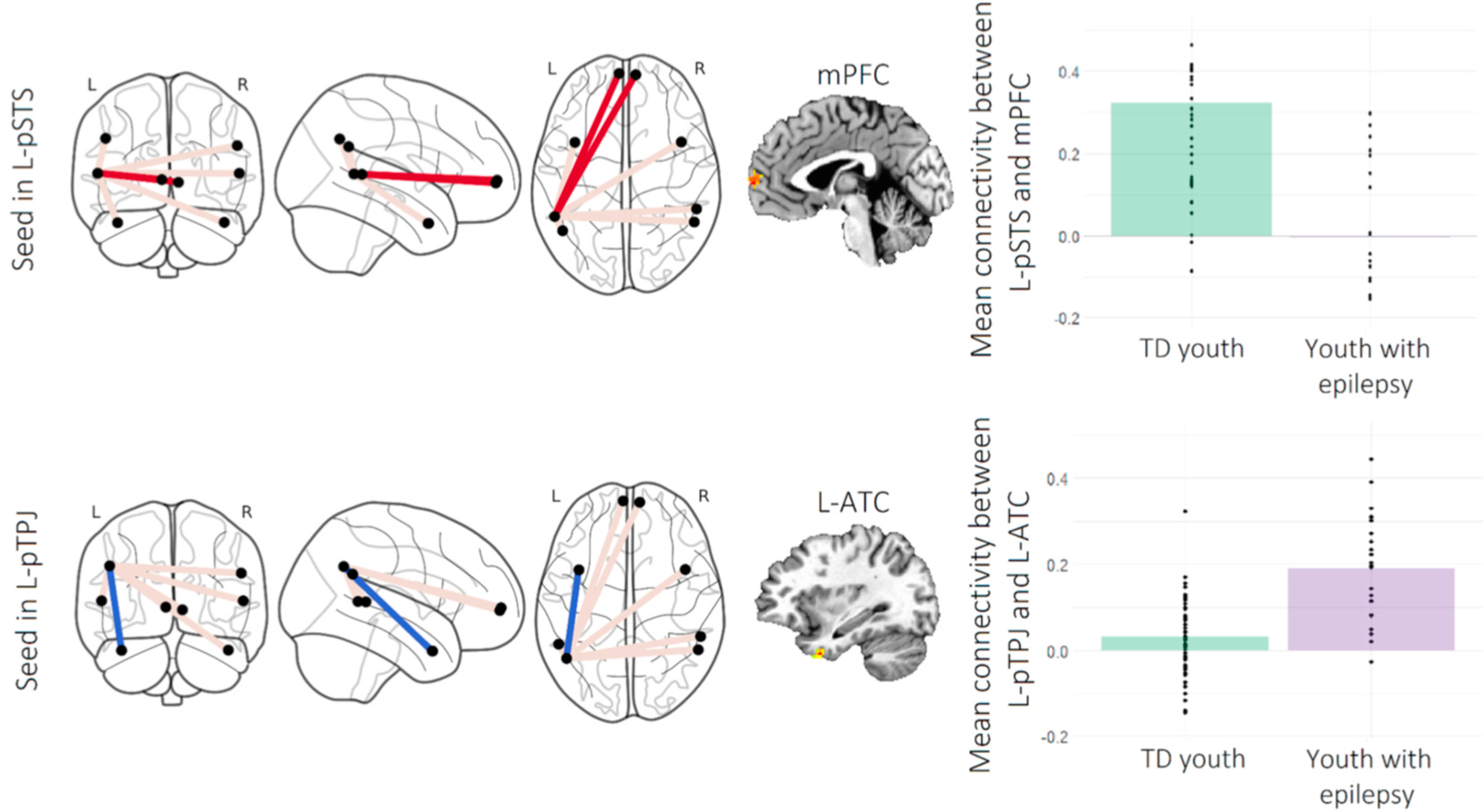

3.2. Group differences in functional connectivity during a social cognitive task

For the seed in the left pSTS, there was an effect of Group on functional connectivity with the bilateral target mPFC region during the task (Table 2; Fig. 3). TD youth showed greater connectivity between these regions than did youth with epilepsy. There was also an effect of Group on connectivity between the seed left pTPJ seed and the target left ATC, whereby youth with epilepsy showed greater functional connectivity than did TD youth. There were no group differences in connectivity for any other seed region in the mentalizing network, nor for any seed in the amygdala network.

Table 2.

Generalized psychophysiological interaction analysis: effect of Group on task-based connectivity within the mentalizing network.

| Seed region | Target region | F | k | x | y | z | Generalized η2 | Brodmann area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-pSTS | mPFC (at midline) | 18.37 | 40 | 1 | 61 | 11 | .24 | 10 |

| L-pTPJ | L-ATC | 37.20 | 15 | −31 | 7 | −34 | .39 | 38 |

Note. Clusters listed here represent areas in which there was an effect of Group (youth with epilepsy vs. typically-developing youth) on functional connectivity with each seed region, during the facial emotion recognition task (stimulus presentation period). Clusters were formed using 3dclustsim at p < .001 (i.e., corrections for cluster-size). R = right, L = left. pSTS = posterior superior temporal sulcus; pTPJ = posterior temporo-parietal junction. k = cluster size in voxels. xyz coordinates represent the cluster’s center of mass, in Talairach-Tournoux space. ƞ2 = eta squared. There were no effects of Group on functional connectivity with the other seeds. Interactions of Group × Age on connectivity are detailed in Table 3.

Fig. 3.

Note. Group differences in task-based functional connectivity in the mentalizing network. Figure depicts significant effects of Group (typically-developing [TD] youth vs. youth with epilepsy) on task-based connectivity in the mentalizing network. R = right, L = left. pSTS = posterior superior temporal sulcus, pTPJ = posterior temporo-parietal junction, mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex, ATC = anterior temporal cortex. Red and blue lines on the connectome images represent connections that were weaker and stronger in youth with epilepsy compared to TD youth, respectively; grey lines represent connections for which the groups did not differ. The mPFC target in the top row is represented as two nodes in the graph but is located at the midline.

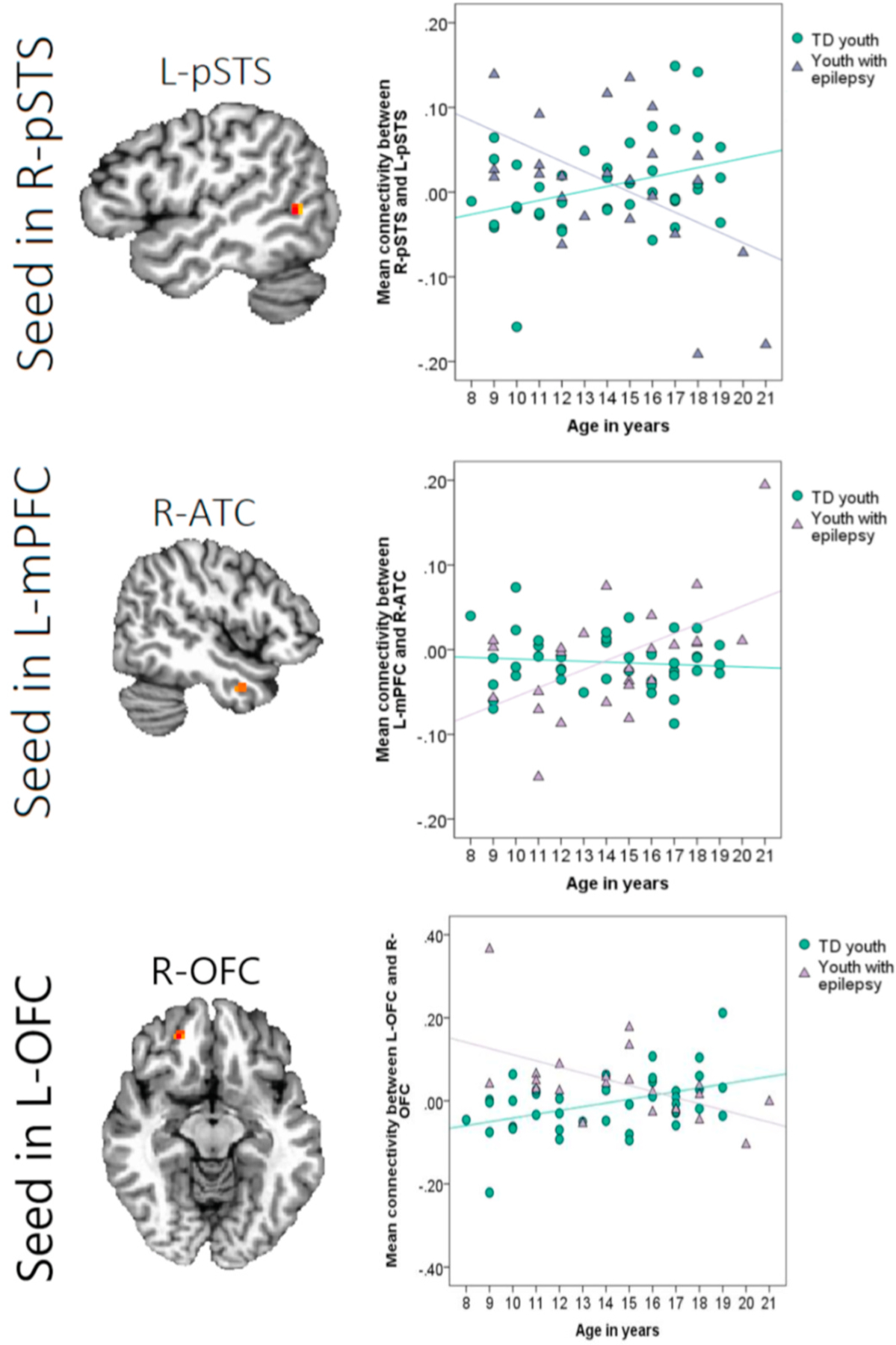

In addition, the Group × Age interaction term was significant for a) connectivity between the seed right pSTS and the target left pSTS, b) connectivity between the seed left mPFC and the target right ATC, and c) connectivity between the seed left OFC and the target right OFC (Table 3; Fig. 4). Simple-slopes tests were performed to probe these interactions. Age was associated with greater connectivity between the right and left pSTS in TD youth, t(59) = 2.02, B = 0.01, β = 0.29, p = .048, but to decreased connectivity between these regions for youth with epilepsy, t(59) = −3.76, B = −0.01, β = −0.75, p < .001. In contrast, age was linked to greater connectivity between the left mPFC and the contralateral ATC for youth with epilepsy, t(59) = 4.58, B = 0.01, β = 0.90, p < .001, but not for TD youth, p = .65. Lastly, age was positively associated with greater connectivity between the left and right OFC in TD youth, t(61) = 3.25, p = .002, but negatively correlated with connectivity between these areas for youth with epilepsy, t(61) = −2.73, p = .008.2

Table 3.

Generalized psychophysiological interaction analysis: interaction of Group × Age on task-based connectivity within the mentalizing and amygdala networks.

| Seed region | Target region | F | k | x | y | z | Generalized η2 | Brodmann area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-mPFC | R-ATC | 15.69 | 16 | 45 | 2 | −25 | .21 | 38 |

| R-pSTS | L-pSTS | 19.50 | 12 | −46 | −56 | 5 | .25 | 37 |

| L-OFC | R-OFC | 16.93 | 15 | 21 | 42 | −7 | .23 | 10 |

Note. Clusters listed here represent areas in which there was an interaction of Group (youth with epilepsy vs. typically-developing youth) and Age on functional connectivity with each seed region, during the facial emotion recognition task (stimulus presentation period). Clusters were formed using 3dclustsim at p < .001 (i.e., corrections for cluster-size). R = right, L = left. mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; ATC = anterior temporal cortex; pSTS = posterior superior temporal sulcus; OFC = orbitofrontal cortex. k = cluster size in voxels. xyz coordinates represent the cluster’s center of mask, in Talairach-Tournoux space. ƞ2 = eta squared. There were no interactions of Group × Age on functional connectivity with the other seeds. Main effects of Group on connectivity are detailed in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Note. Group differences in age-related changes in task-based connectivity. Figure depicts significant interactions of Group (typically-developing [TD] youth vs. youth with epilepsy) × Age (in years) on task-based connectivity with three seed regions. R = right, L = left. pSTS = posterior superior temporal sulcus, mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex, ATC = anterior temporal cortex, OFC = orbitofrontal cortex.

3.3. Relationship between task-based connectivity and task performance

Partial correlations were computed to examine the association between average Hu (arcsine-transformed) and connectivity between a) the left pSTS and mPFC at midline, b) the left pTPJ and left ATC, c) the right pSTS and left pSTS, d) the left mPFC and the right ATC, and e) the left OFC and the right OFC, controlling for age. There was a significant negative correlation between average Hu and connectivity between the left pTPJ and the left ATC, r(32) = −0.43, p = .01, indicating that greater co-activation between these regions during the task (as was noted in the group of youth with epilepsy, relative to TD youth) is related to poorer performance in the task. There was also a trend towards a positive correlation between average Hu and connectivity between the left pSTS and mPFC, r(32) = 0.31, p = .07, suggesting that greater connectivity between these areas during the task (as was noted in the group of TD youth, relative to youth with epilepsy) is marginally related to greater task accuracy. We note that neither correlation would survive Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons; these findings thus provide preliminary information about the relationship between connectivity and accuracy, but require replication.

4. Discussion

The current study examined functional connectivity within two social brain networks, both at rest and during a social cognitive task, in youth with and without epilepsy. Understanding the dynamics of these functional networks in this group is particularly important, given that youth with epilepsy are at risk for social difficulties. We found that youth with epilepsy differed from TD youth in brain connectivity within two networks important for social cognition when completing a facial emotion recognition task, but not at rest. Compared to TD youth, youth with epilepsy showed decreased task-based connectivity between the left pSTS and bilateral mPFC, and increased task-based connectivity within the left temporal lobe. There was also some evidence that age-related changes in task-based connectivity across the network may be disrupted in youth with epilepsy. Our findings highlight the importance of extending investigations of resting-state networks to examine connectivity in functional tasks (Stevens, 2016), in order to probe context-specific neurobiological indicators of clinical phenotypes in epilepsy.

4.1. Connectivity of the mentalizing and amygdala networks

Resting-state analyses did not reveal any robust group differences in connectivity across either of the social brain networks under investigation. These findings are somewhat at odds with previous reports of diminished connectivity with the DMN—which overlaps at least partially with the mentalizing network—in individuals with TLE (see review by Cataldi et al., 2013). However, although one study with children with epilepsy found decreased connectivity between the pTPJ and other nodes of the DMN (Widjaja et al., 2013b), other reports have instead localized disruptions to this network in regions like the (posterior) cingulate, hippocampus, or broader medial temporal lobe (Doucet et al., 2015; Ibrahim et al., 2014; Mankinen et al., 2012; Widjaja et al., 2013b; Zhang et al., 2011). It is thus possible that connectivity within the mentalizing network as defined here is less subject to disruption stemming from epilepsy or associated conditions than connectivity in the full DMN. Moreover, the lack of group differences in the amygdala network may stem from its weak spontaneous organization at rest (review by Cataldi et al., 2013); indeed, there is more evidence for blunted activation in this region than for decreased connectivity at rest (Cataldi et al., 2013) in individuals with epilepsy.

In contrast, youth with epilepsy showed weaker connectivity than TD youth between the posterior temporal lobe (pSTS) and the bilateral mPFC when actively engaged in a facial emotion recognition task. Both regions have been implicated in functions relevant to the processing of facial emotional stimuli: the pSTS is engaged in earlier stages of nonverbal emotion perception (e.g., attention to emotion, face processing; Allison et al., 2000; Engell and Haxby, 2007; Haxby et al., 2002; Narumoto et al., 2001), and the mPFC has been involved in mentalizing and social cognition more broadly (Amodio and Frith, 2016; Van Overwalle, 2009). Given that greater connectivity between these areas was marginally related to better facial emotion recognition accuracy, our findings suggest that activation and coordination between these regions may be important for social cognition. Moreover, our results are consistent with reports that adults with temporal lobe epilepsy showed reduced fronto-temporal connectivity while viewing fearful faces compared to healthy controls (Steiger et al., 2017). Disruptions in white matter tracts may impede these connections in youth with epilepsy: for instance, the integrity of the superior longitudinal fasciculus between these regions has been found to be compromised in children with partial epilepsy (Holt et al., 2011). Such impairments in structural organization across these regions may also yield decreased connectivity during tasks that require the engagement of relevant frontal and parietal regions.

In contrast to disruptions to fronto-parietal connectivity during the processing of facial emotion, youth with epilepsy showed greater co-activation between the left pTPJ and ATC during the task, compared to TD youth. These findings are consistent with previous reports of preserved connectivity within the temporal lobe, both when viewing facial expressions (Steiger et al., 2017) and at rest (Liao et al., 2010; Takeda et al., 2017), in individuals with TLE or other forms of focal epilepsy. Such patterns may be reflective of increased connectivity surrounding the epileptic seizure zone (Englot et al., 2015), which is presumed to be the temporal lobe for many participants in the current sample. However, it is notable that this pattern emerged only during the performance of a task that typically recruits these areas (e.g., mentalizing tasks; Nelson et al., 2005; Olson et al., 2007; Overgaauw et al., 2014; Pfeifer and Peake, 2012; Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003; Saxe and Wexler, 2005)—suggesting that hyperconnectivity of the temporal lobe may serve some compensatory function or underlie an alternative task strategy. However, because this pattern of connectivity was associated with poorer performance on the task, increased connectivity within the temporal lobe may represent an inefficient approach to parsing emotional information in faces.

4.2. Differences in age-related changes to connectivity within the social brain

In typically-developing adolescents, age-related increases in connectivity are thought to reflect normative maturation (Blakemore, 2008). However, we found evidence for differential effects of age in youth with epilepsy compared to TD youth during task engagement. Specifically, when viewing emotional faces, age was associated with greater connectivity between the right and left pSTS in TD youth, but with reduced connectivity among these regions in youth with epilepsy. The same pattern was noted for connectivity between the right and left OFC. In TD youth, age-related increases in OFC co-activation may be reflective of developmental changes in baseline regional connectivity within the frontal lobe (at rest; Fair et al., 2008). Moreover, increased coordination of right and left pSTS regions may facilitate the decoding of social cues, given that heightened connection between both pSTS regions has been found to be related to greater accuracy in a mentalizing task (Wang, Song, Zhen and Liu, 2016). Instead of showing age-related increases in the co-activation of these regions as did TD youth, youth with epilepsy showed decreases in connectivity across hemispheres with age. This pattern may reflect not only an attenuated maturation, but also a possible decompensation in the group with epilepsy. Alternatively, reduced connections across hemispheres may be reflective of a protective mechanism to limit propagation of seizures across the brain. Indeed, the network inhibition hypothesis suggests that long-range connections may be weakened from repeated deactivation during seizures (Englot and Blumenfeld, 2009; Englot et al., 2015). Changes to the organization of neural networks across time are likely relevant to the performance of social cognitive tasks that would benefit from network integration, including cross-hemisphere communication.

Moreover, age was positively associated with increased connectivity between the bilateral mPFC and the right ATC in youth with epilepsy, but not in TD youth. Task demands may promote stronger connectivity across these regions with age. Alternatively, this pattern may reflect a compensatory mechanism for communication among nodes of the social brain that are involved in mentalizing (Amodio and Frith, 2016; Olson et al., 2007), without relying on longer-range connections to other relevant regions like the pTPJ.

Our secondary analyses examining group differences in age-related changes in connectivity should be interpreted with caution, given our modest sample size. Nonetheless, such findings encourage the consideration of age as a variable of interest in larger-scale studies of task-based connectivity in pediatric epilepsy. Along with other illness-related factors or the impact of comorbid conditions, repeated seizures may have a detrimental impact on the fine-tuning of functional neural networks across development. Widespread changes to the architecture of white matter tracts and to grey matter morphology (Tavakol et al., 2019) likely impede the normative development of neural systems and may have functional consequences for youth with epilepsy. For instance, the development of social cognition and social behaviour is thought to rely on white matter connections, which permit rapid integration of information across the neural net (Kennedy and Adolphs, 2012). Changes to connectivity, as well as structural damage to frontal and temporal regions involved in social cognition—commonly noted in chronic focal epilepsy, or frequently comorbid conditions like autism—may therefore impact social function (see review by Kirsch, 2006). Indeed, social cognitive deficits are found to be more pronounced in adults with childhood-onset epilepsy (Besag and Vasey, 2019), particularly in the context of damage to the amygdala, TPJ, mPFC, or networks involving these nodes (Giovagnoli et al., 2011). There is also evidence for progressively diminished connectivity (Englot et al., 2015; Haneef et al., 2015; Morgan et al., 2015) with prolonged duration of seizures in adults; though this pattern did not emerge in our sample, ongoing seizures, comorbid conditions, and other illness-related factors may interfere with developmental processes that would instead favor the coalescence of neural networks. Longitudinal work in youth who have experienced recurrent seizures will be important to elucidate the impact of intractable epilepsy on neural organization in the developing brain.

4.3. Strengths & limitations

To our knowledge, the current study is the first investigation of both resting-state and task-based connectivity in a social cognition task in youth with epilepsy. We probed the organization of two social brain networks, both at rest and when engaged in a facial emotion recognition task, to further our understanding of the neural systems that support social cognition and social behaviour—two aspects of functioning that are often impaired in individuals with epilepsy. Direct comparison of the task-based and resting-state conditions is tenuous, given differences in the number of participants who could be included in both analyses; however, the use of similar seed-based approaches does allow us to draw some contrasts between social networks’ organization at baseline and when responding to task demands. Indeed, group differences in network connectivity were not identical in both conditions, suggesting that epilepsy—or comorbid conditions and phenotypes—may have a differential impact on functional neural circuits than on resting-state systems.

Limitations must be noted. First, our sample size was modest given the specialization of our population and the demands of the scanning protocol. In particular, analyses examining group differences in age-related changes in connectivity—though of interest—are likely under-powered to detect non-linear changes in maturation. Nonetheless, we believe that our findings point to the importance of examining the impact of epilepsy on expected developmental trajectories in neural organization. Relatedly, any future investigation of this question should include assessments of developmental stage beyond chronological age. Given that youth with epilepsy can experience differential treatment by caregivers, more stigma, and more limitations on normative adolescent experiences than TD youth (e.g., Asato et al., 2009; Jacoby and Austin, 2007; Suris et al., 2004), measuring pubertal status and social experiences can be a better indicator of social development than age alone. Second, the group of youth with epilepsy were somewhat heterogenous in the localization of seizure onset and duration of illness. Though neither of these variables predicted group differences in functional connectivity, the variability in illness characteristics limits the specificity of our findings. Replication in more homogenous, larger samples would enhance confidence in the generalizability of our results. Lastly, given evidence of compensatory re-organization of neural networks in individuals with epilepsy (Englot et al., 2016), longitudinal studies of social brain connectivity would provide better insight into age-related changes in neural systems relevant to social functioning. Including real-world measures of social functioning would also elucidate the behavioural consequences of network integrity in the social brain.

4.4. Conclusions

The current study examined resting-state and task-based connectivity in social brain networks, in youth with and without epilepsy. Compared to TD youth, youth with intractable epilepsy showed reduced fronto-parietal connectivity, but increased within-temporal lobe connectivity, when processing emotional faces in a social cognitive task. These findings provide evidence for differential organization of the mentalizing network in youth with intractable epilepsy during relevant tasks. Larger-scaled replications and examinations of the link between connectivity and social outcomes will help determine whether such atypical neural organization is a hallmark of social deficits in pediatric epilepsy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the help of Joseph Venticinque, Stanley Singer, Jr., Connor Grannis, Andy Hung, Brooke Fuller, and Meika Travis in collecting and processing the data, as well as to the participants and their families for their time. We also recognize the Biobehavioral Outcomes Core at Nationwide Children’s Hospital for their assistance with neuropsychological testing in our sample of typically-developing youth. Lastly, we thank Dr. Satyanarayana Gedela and Dr. Adam Ostendorf for their help in facilitating this study.

Funding

This work was supported by internal funds in the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Nature et technologies (grant number 207776).

Footnotes

Credit author statement

Michele Morningstar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Verification, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Roberto C. French: Methodology, Software, Verification, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Whitney I. Mattson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Verification, Writing – review & editing. Dario J. Englot: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Eric E. Nelson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

The final groups in either analysis did not differ in age (ps > .16). The groups used in task-based analyses did not differ in gender (Fisher’s exact test, p = .07), but there were more males with epilepsy than TD males in resting-state analyses (Fisher’s exact test, p = .004). Follow-up analyses examined whether gender predicted connectivity among areas in which group differences were noted (see footnote 2).

Within the group of youth with epilepsy, follow-up correlations were performed to examine whether age of epilepsy onset predicted task-based functional connectivity between the left pSTS and the bilateral mPFC, between the left pTPJ and the left ATC, between the left mPFC and the right ATC, between the right pSTS and the left pSTS, or between the left OFC and the right OFC. No correlations were significant (ps > .11), suggesting that age of onset was not related to differential connectivity across these regions. In addition, follow-up univariate analyses of variance revealed that neither the type of epilepsy nor the lateralization of seizures predicted functional connectivity between the above regions (all ps > .08). Similarly, gender was not predictive of functional connectivity among these areas (all ps > .60), except for the connection between the left pTPJ and the left ATC during the task (p = .003, whereby males showed greater connectivity than females).

References

- Adolphs R, 2001. The neurobiology of social cognition. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 11 (2), 231–239. 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, 2002a. Neural systems for recognizing emotion. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 12 (2), 169–177. 10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00301-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, 2002b. Recognizing emotion from facial expressions: psychological and neurological mechanisms. Behav. Cognit. Neurosci. Rev 1 (1), 21–62. 10.1177/1534582302001001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, 2009. The social brain: neural basis of social knowledge. Annu. Rev. Psychol 60 (1), 693–716. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison T, Puce A, McCarthy G, 2000. Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends Cognit. Sci 4 (7), 267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodio DM, Frith CD, 2016. Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition. In: Discovering the Social Mind Psychology Press, pp. 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Asato MR, Manjunath R, Sheth RD, Phelps SJ, Wheless JW, Hovinga CA, Zingaro WM, 2009. Adolescent and caregiver experiences with epilepsy. J. Child Neurol 24 (5), 562–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benuzzi F, Meletti S, Zamboni G, Calandra-Buonaura G, Serafini M, Lui F, Nichelli P, 2004. Impaired fear processing in right mesial temporal sclerosis: a fMRI study. Brain Res. Bull 63 (4), 269–281. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt BC, Chen Z, He Y, Evans AC, Bernasconi N, 2011. Graph-theoretical analysis reveals disrupted small-world organization of cortical thickness correlation networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. Cerebr. Cortex 21 (9), 2147–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besag FMC, Vasey MJ, 2019. Social cognition and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. Epilepsy Behav 100, 106210. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettus G, Guedj E, Joyeux F, Confort-Gouny S, Soulier E, Laguitton V, Bartolomei F, 2009. Decreased basal fMRI functional connectivity in epileptogenic networks and contralateral compensatory mechanisms. Hum. Brain Mapp 30 (5), 1580–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, 2008. The social brain in adolescence. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 9 (4), 267–277. 10.1038/nrn2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, den Ouden H, Choudhury S, Frith C, 2007. Adolescent Development of the Neural Circuitry for Thinking about Intentions [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blakemore SJ, Mills KL, 2014. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol 65, 187–207. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Meletti S, 2016. Social cognition in temporal lobe epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav 60, 50–57. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broicher SD, Frings L, Huppertz HJ, Grunwald T, Kurthen M, Kramer G, Jokeit H, 2012a. Alterations in functional connectivity of the amygdala in unilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurol 259 (12), 2546–2554. 10.1007/s00415-012-6533-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broicher SD, Kuchukhidze G, Grunwald T, Krämer G, Kurthen M, Jokeit H, 2012b. “Tell me how do I feel” – emotion recognition and theory of mind in symptomatic mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychologia 50 (1), 118–128. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett S, Blakemore SJ, 2009a. The development of adolescent social cognition. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1167, 51–56. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett S, Blakemore SJ, 2009b. Functional connectivity during a social emotion task in adolescents and in adults. Eur. J. Neurosci 29 (6), 1294–1301. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camfield CS, Camfield P, Smith B, Gordon K, Dooley J, 1993. Biologic factors as predictors of social outcome of epilepsy in intellectually normal children: a population-based study. J. Pediatr 122 (6), 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camfield CS, Camfield PR, 2007. Long-term social outcomes for children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 48 (s9), 3–5. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01390x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camfield PR, Camfield CS, 2014. What happens to children with epilepsy when they become adults? Some facts and opinions. Pediatr. Neurol 51 (1), 17–23. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantalupo G, Meletti S, Miduri A, Mazzotta S, Rios-Pohl L, Benuzzi F, Cossu G, 2013. Facial emotion recognition in childhood: the effects of febrile seizures in the developing brain. Epilepsy Behav 29 (1), 211–216. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi M, Avoli M, de Villers-Sidani E, 2013. Resting state networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 54 (12), 2048–2059. 10.1111/epi.12400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Adleman NE, Saad ZS, Leibenluft E, Cox RW, 2014. Applications of multivariate modeling to neuroimaging group analysis: a comprehensive alternative to univariate general linear model. Neuroimage 99, 571–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Prather A, Town P, Hynd G, 1990. Neurodevelopmental differences in emotional prosody in normal children and children with left and right temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Lang 38 (1), 122–134. Retrieved from. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2302542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, 1996. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput. Biomed. Res 29 (3), 162–173. 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, Reynolds RC, Taylor PA, 2016. AFNI and clustering: false positive rates redux. Brain Connect 7 (3), 152–171. 10.1089/brain.2016.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Heyman I, Goodman R, 2003. A population survey of mental health problems in children with epilepsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol 45 (5), 292–295. 10.1017/S0012162203000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai VR, Vedantam A, Lam SK, Mirea L, Foldes ST, Curry DJ, Boerwinkle VL, 2018. Language lateralization with resting-state and task-based functional MRI in pediatric epilepsy, 23 (2), 171. 10.3171/2018.7.Peds18162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet GE, Sharan A, Pustina D, Skidmore C, Sperling MR, Tracy JI, 2015. Early and late age of seizure onset have a differential impact on brain resting-state organization in temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Topogr 28 (1), 113–126. 10.1007/s10548-014-0366-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewel EH, Caplan R, 2007. Social difficulties in children with epilepsy: review and treatment recommendations. Expert Rev. Neurother 7 (7), 865–873. 10.1586/14737175.7.7.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar RIM, 1998. The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues. New Rev 6 (5), 178–190. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Pine DS, Nelson E, Leibenluft E, Ernst M, Towbin KE, Angold A, 2011. The NIMH Child Emotional Faces Picture Set (NIMH-ChEFS): a new set of children’s facial emotion stimuli. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res 20 (3), 145–156. 10.1002/mpr.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engell AD, Haxby JV, 2007. Facial expression and gaze-direction in human superior temporal sulcus. Neuropsychologia 45 (14), 3234–3241. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Blumenfeld H, 2009. Consciousness and epilepsy: why are complex-partial seizures complex? Prog. Brain Res 177, 147–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Hinkley LB, Kort NS, Imber BS, Mizuiri D, Honma SM, Nagarajan SS, 2015. Global and regional functional connectivity maps of neural oscillations in focal epilepsy. Brain 138 (Pt 8), 2249–2262. 10.1093/brain/awv130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Konrad PE, Morgan VL, 2016. Regional and global connectivity disturbances in focal epilepsy, related neurocognitive sequelae, and potential mechanistic underpinnings. Epilepsia 57 (10), 1546–1557. 10.1111/epi.13510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethofer T, Bretscher J, Wiethoff S, Bisch J, Schlipf S, Wildgruber D, Kreifelts B, 2013. Functional responses and structural connections of cortical areas for processing faces and voices in the superior temporal sulcus. Neuroimage 76, 45–56. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair DA, Cohen AL, Dosenbach NUF, Church JA, Miezin FM, Barch DM, Schlaggar BL, 2008. The maturing architecture of the brain’s default network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am 105 (10), 4028–4032. 10.1073/pnas.0800376105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler HL, Baker GA, Tipples J, Hare DJ, Keller S, Chadwick DW, Young AW, 2006. Recognition of emotion with temporal lobe epilepsy and asymmetrical amygdala damage. Epilepsy Behav 9 (1), 164–172. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerts A, Brouwer O, van Donselaar C, Stroink H, Peters B, Peeters E, Arts WF, 2011. Health perception and socioeconomic status following childhood-onset epilepsy: the Dutch study of epilepsy in childhood. Epilepsia 52 (12), 2192–2202. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovagnoli AR, Franceschetti S, Reati F, Parente A, Maccagnano C, Villani F, Spreafico R, 2011. Theory of mind in frontal and temporal lobe epilepsy: cognitive and neural aspects. Epilepsia 52 (11), 1995–2002. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovagnoli AR, Smith ML, 2019. Investigating the social cognition phenotypes in children, adolescents, and adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 100, 106438. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golouboff N, Fiori N, Delalande O, Fohlen M, Dellatolas G, Jambaque I, 2008. Impaired facial expression recognition in children with temporal lobe epilepsy: impact of early seizure onset on fear recognition. Neuropsychologia 46 (5), 1415–1428. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassia F, Poliakov AV, Poliachik SL, Casimo K, Friedman SD, Shurtleff H, Hauptman JS, 2018. Changes in resting-state connectivity in pediatric temporal lobe epilepsy, 22 (3), 270. 10.3171/2018.3.Peds17701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamiwka LD, Hamiwka LA, Sherman EMS, Wirrell E, 2011. Social skills in children with epilepsy: how do they compare to healthy and chronic disease controls? Epilepsy Behav 21 (3), 238–241. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamiwka LD, Wirrell EC, 2009. Comorbidities in pediatric epilepsy: beyond “just” treating the seizures. J. Child Neurol 24 (6), 734–742. 10.1177/0883073808329527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haneef Z, Chiang S, Yeh HJ, Engel J Jr., Stern JM, 2015. Functional connectivity homogeneity correlates with duration of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 46, 227–233. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI, 2002. Human neural systems for face recognition and social communication. Biol. Psychiatr 51 (1), 59–67. 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt RL, Provenzale JM, Veerapandiyan A, Moon W-J, De Bellis MD, Leonard S, Mikati MA, 2011. Structural connectivity of the frontal lobe in children with drug-resistant partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 21 (1), 65–70. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim GM, Morgan BR, Lee W, Smith ML, Donner EJ, Wang F, Carter Snead III O, 2014. Impaired development of intrinsic connectivity networks in children with medically intractable localization-related epilepsy. Hum. Brain Mapp 35 (11), 5686–5700. 10.1002/hbm.22580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby A, Austin JK, 2007. Social stigma for adults and children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 48, 6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovljević V, Martinović Ž, 2006. Social competence of children and adolescents with epilepsy. Seizure 15 (7), 528–532. 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalava M, Sillanpää M, 1997. Reproductive activity and offspring health of young adults with childhood-onset epilepsy: a controlled study. Epilepsia 38 (5), 532–540. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM, 2012. FSL. NeuroImage 62 (2), 782–790. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM, 1997. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J. Neurosci 17 (11), 4302. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Adolphs R, 2012. The social brain in psychiatric and neurological disorders. Trends Cognit. Sci 16 (11), 559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch HE, 2006. Social cognition and epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav 8 (1), 71–80. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapwijk ET, Goddings AL, Burnett Heyes S, Bird G, Viner RM, Blakemore SJ, 2013. Increased functional connectivity with puberty in the mentalising network involved in social emotion processing. Horm. Behav 64 (2), 314–322. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkonen J, Kokkonen E-R, Saukkonen A-L, Pennanen P, 1997. Psychosocial outcome of young adults with epilepsy in childhood. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr 62 (3), 265–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MA, Cash SS, 2012. Epilepsy as a disorder of cortical network organization. Neuroscientist 18 (4), 360–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreifelts B, Ethofer T, Shiozawa T, Grodd W, Wildgruber D, 2009. Cerebral representation of non-verbal emotional perception: fMRI reveals audiovisual integration area between voice- and face-sensitive regions in the superior temporal sulcus. Neuropsychologia 47 (14), 3059–3066. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent A, Arzimanoglou A, Panagiotakaki E, Sfaello I, Kahane P, Ryvlin P, de Schonen S, 2014. Visual and auditory socio-cognitive perception in unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy in children and adolescents: a prospective controlled study. Epileptic Disord 16 (4), 456–470. 10.1684/epd.2014.0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Zhang Z, Pan Z, Mantini D, Ding J, Duan X, Chen H, 2010. Altered functional connectivity and small-world in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. PloS One 5 (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Zhang Z, Pan Z, Mantini D, Ding J, Duan X, Lu G, 2011. Default mode network abnormalities in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: a study combining fMRI and DTI. Hum. Brain Mapp 32 (6), 883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankinen K, Jalovaara P, Paakki J-J, Harila M, Rytky S, Tervonen O, Rantala H, 2012. Connectivity disruptions in resting-state functional brain networks in children with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 100 (1–2), 168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren DG, Ries ML, Xu G, Johnson SC, 2012. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): a comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage 61 (4), 1277–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Lalonde F, Clasen LS, Giedd JN, Blakemore SJ, 2014. Developmental changes in the structure of the social brain in late childhood and adolescence. Soc. Cognit. Affect Neurosci 9 (1), 123–131. 10.1093/scan/nss113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moor BG, de Macks ZAO, Güroğlu B, Rombouts SA, Van der Molen MW, Crone EA, 2012. Neurodevelopmental changes of reading the mind in the eyes. Soc. Cognit. Affect Neurosci 7 (1), 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan VL, Conrad BN, Abou-Khalil B, Rogers BP, Kang H, 2015. Increasing structural atrophy and functional isolation of the temporal lobe with duration of disease in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 110, 171–178. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morningstar M, Grannis C, Mattson WI, Nelson EE, 2019. Associations between adolescents’ social Re-orientation toward peers over caregivers and neural response to teenage faces. Front. Behav. Neurosci 13 (108) 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morningstar M, Hung A, Grannis C, French RC, Mattson WI, Ostendorf AP, Nelson EE, 2020. Blunted neural response to emotional faces in the fusiform and superior temporal gyrus may be marker of emotion recognition deficits in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 112, 107432. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narumoto J, Okada T, Sadato N, Fukui K, Yonekura Y, 2001. Attention to emotion modulates fMRI activity in human right superior temporal sulcus. Cognit. Brain Res 12 (2), 225–231. 10.1016/S0926-6410(01)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Guyer AE, 2011. The development of the ventral prefrontal cortex and social flexibility. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 1 (3), 233–245. 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Jarcho JM, Guyer AE, 2016. Social re-orientation and brain development: an expanded and updated view. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 17, 118–127. 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Leibenluft E, McClure EB, Pine DS, 2005. The social re-orientation of adolescence: a neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychol. Med 35, 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC, 1971. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9 (1), 97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Plotzker A, Ezzyat Y, 2007. The enigmatic temporal pole: a review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain 130 (7), 1718–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overgaauw S, Guroglu B, Rieffe C, Crone EA, 2014. Behavior and neural correlates of empathy in adolescents. Dev. Neurosci 36 (3–4), 210–219. 10.1159/000363318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JH, Peake SJ, 2012. Self-development: integrating cognitive, socioemotional, and neuroimaging perspectives. Developmental cognitive neuroscience 2 (1), 55–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittau F, Grova C, Moeller F, Dubeau F, Gotman J, 2012. Patterns of altered functional connectivity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 53 (6), 1013–1023. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruim RH, Mennes M, van Rooij D, Llera A, Buitelaar JK, Beckmann CF, 2015. ICA-AROMA: a robust ICA-based strategy for removing motion artifacts from fMRI data. Neuroimage 112, 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen K, Timonen S, Hagström K, Hamäläinen P, Eriksson K, Nieminen P, 2009. Social competence of preschool children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 14 (2), 338–343. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raud T, Kaldoja ML, Kolk A, 2015. Relationship between social competence and neurocognitive performance in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 52 (Pt A), 93–101. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redcay E, 2008. The superior temporal sulcus performs a common function for social and speech perception: implications for the emergence of autism. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 32 (1), 123–142. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redcay E, Warnell KR, 2018. A social-interactive neuroscience approach to understanding the developing brain. Adv. Child Dev. Behav 54, 1–44. 10.1016/bs.acdb.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth MF, Mars RB, Sallet J, 2013. Are there specialized circuits for social cognition and are they unique to humans? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 23 (3), 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ SA, Larson K, Halfon N, 2012. A national profile of childhood epilepsy and seizure disorder. Pediatrics 129 (2), 256–264. 10.1542/peds.2010-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Kanwisher N, 2003. People thinking about thinking people: the role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. Neuroimage 19 (4), 1835–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Wexler A, 2005. Making sense of another mind: the role of the right temporo-parietal junction. Neuropsychologia 43 (10), 1391–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian CL, Fontaine NMG, Bird G, Blakemore S-J, De Brito SA, McCrory EJP, Viding E, 2011. Neural processing associated with cognitive and affective Theory of Mind in adolescents and adults. Soc. Cognit. Affect Neurosci 7 (1), 53–63. 10.1093/scan/nsr023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamshiri EA, Tierney TM, Centeno M, St Pier K, Pressler RM, Sharp DJ, Carmichael DW, 2017. Interictal activity is an important contributor to abnormal intrinsic network connectivity in paediatric focal epilepsy. Hum. Brain Mapp 38 (1), 221–236. 10.1002/hbm.23356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpää M, Cross HJ, 2009. The psychosocial impact of epilepsy in childhood., Supplement 1). Epilepsy Behav 15 (2), S5–S10. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Jones RM, Casey BJ, 2010. A time of change: behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain Cognit 72 (1), 124–133. 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger BK, Muller AM, Spirig E, Toller G, Jokeit H, 2017. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy diminishes functional connectivity during emotion perception. Epilepsy Res 134, 33–40. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens MC, 2016. The contributions of resting state and task-based functional connectivity studies to our understanding of adolescent brain network maturation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 70, 13–32. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart E, Catroppa C, Gonzalez L, Gill D, Webster R, Lawson J, Lah S, 2019a. Facial emotion perception and social competence in children (8 to 16 years old) with genetic generalized epilepsy and temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 100, 106301. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart E, Catroppa C, Lah S, 2016. Theory of mind in patients with epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev 26 (1), 3–24. 10.1007/s11065-015-9313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart E, Lah S, Smith ML, 2019b. Patterns of impaired social cognition in children and adolescents with epilepsy: the borders between different epilepsy phenotypes. Epilepsy Behav 100, 106146. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supekar K, Musen M, Menon V, 2009. Development of large-scale functional brain networks in children. PLoS Biol 7 (7), 1–15. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suris JC, Michaud PA, Viner R, 2004. The adolescent with a chronic condition. Part I: developmental issues. Arch. Dis. Child 89 (10), 938–942. 10.1136/adc.2003.045369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann JW, 2004. The effects of seizures on the connectivity and circuitry of the developing brain. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev 10 (2), 96–100. 10.1002/mrdd.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szemere E, Jokeit H, 2015. Quality of life is social – towards an improvement of social abilities in patients with epilepsy. Seizure 26, 12–21. 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Matsuda H, Miyamoto Y, Yamamoto H, 2017. Structural brain network analysis of children with localization-related epilepsy. Brain Dev 39 (8), 678–686. 10.1016/j.braindev.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol S, Royer J, Lowe AJ, Bonilha L, Tracy JI, Jackson GD, Bernhardt BC, 2019. Neuroimaging and connectomics of drug-resistant epilepsy at multiple scales: from focal lesions to macroscale networks. Epilepsia 60 (4), 593–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse E, Hamiwka L, Sherman EMS, Wirrell E, 2007. Social skills problems in children with epilepsy: prevalence, nature and predictors. Epilepsy Behav 11 (4), 499–505. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijvenvoorde ACK, Achterberg M, Braams BR, Peters S, Crone EA, 2016. Testing a dual-systems model of adolescent brain development using resting-state connectivity analyses. Neuroimage 124, 409–420. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Overwalle F, 2009. Social cognition and the brain: a meta-analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp 30 (3), 829–858. 10.1002/hbm.20547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter NC, Weigelt S, Döhnel K, Smolka MN, Kliegel M, 2014. Ongoing neural development of affective theory of mind in adolescence. Soc. Cognit. Affect Neurosci 9 (7), 1022–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner HL, 1993. On measuring performance in category judgment studies of nonverbal behavior. J. Nonverbal Behav 17 (1), 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wakamoto H, Nagao H, Hayashi M, Morimoto T, 2000. Long-term medical, educational, and social prognoses of childhood-onset epilepsy: a population-based study in a rural district of Japan. Brain Dev 22 (4), 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WH, Shih YH, Yu HY, Yen DJ, Lin YY, Kwan SY, Hua MS, 2015. Theory of mind and social functioning in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 56 (7), 1117–1123. 10.1111/epi.13023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]