Executive summary

Health is central to the development of any country. Nigeria's gross domestic product is the largest in Africa, but its per capita income of about ₦770 000 (US$2000) is low with a highly inequitable distribution of income, wealth, and therefore, health. It is a picture of poverty amidst plenty. Nigeria is both a wealthy country and a very poor one. About 40% of Nigerians live in poverty, in social conditions that create ill health, and with the ever-present risk of catastrophic expenditures from high out-of-pocket spending for health. Even compared with countries of similar income levels in Africa, Nigeria's population health outcomes are poor, with national statistics masking drastic differences between rich and poor, urban and rural populations, and different regions.

Nigeria also holds great promise. It is Africa's most populous country with 206 million people and immense human talent; it has a diaspora spanning the globe, 374 ethnic groups and languages, and a decentralised federal system of governance as enshrined in its 1999 Constitution. In this Commission, we present a positive outlook that is both possible and necessary for Nigeria to deliver equitable and optimal health outcomes. If the country confronts its toughest challenges—a complex political structure, weak governance, poor accountability, inefficiency, and corruption—it has the potential to vastly improve population health using a multisector, whole-of-government approach.

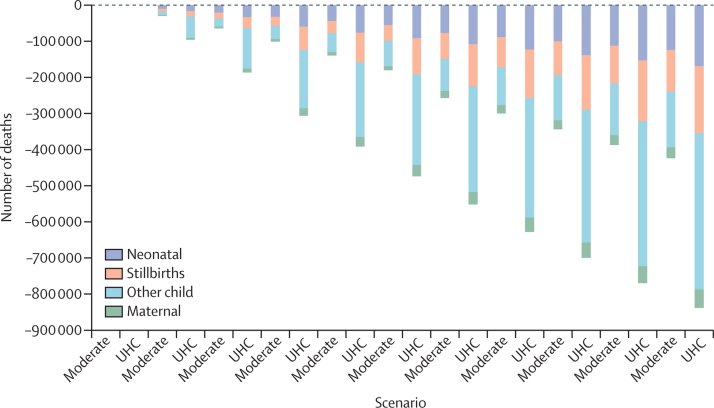

Major obstacles include ineffective use of available resources, a dearth of robust population-level health and mortality data, insufficient financing for health and health care, sub-optimal deployment of available health funding to purchase health services, and large population inequities. Nigeria's demographic dividend has unguaranteed potential, with a high dependency ratio, a fast-growing population, and slow reduction in child mortality. Effective, quality reproductive, maternal, and child health services including family planning, and female education and empowerment are likely to accelerate demographic transition and yield a demographic dividend.

This Commission was written in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has laid bare the inability of the public health system to confront new pathogens with threats to human health. However, despite a history of weak surveillance and diagnostic infrastructure, the scale up of COVID-19 diagnostics suggests that it is possible to rapidly improve other areas with sufficient local effort and resources.

The Lancet Nigeria Commission aims to reposition future health policy in Nigeria to achieve universal health coverage and better health for all. This Commission presents analysis and evidence to support a positive and realistic future for Nigeria. The Commission addresses historically intractable challenges with a new narrative. Nigeria's path to greater prosperity lies through investment in the social determinants of health and the health system.

Addressing multiple, intersecting disease burdens in a diverse population requires an equal balance between prevention and care

Nigeria is not making use of its most precious resource—its people—by not adequately enacting policies to address preventable health problems. Health is influenced by access to quality health services, but other influencing factors lie outside this sphere. Huge gains in health can and must be made by ensuring adequate sanitation and hygiene, access to clean water, and food security, especially for children, and by addressing environmental threats to health, including air pollution.

Nigeria has a young population, yet, despite spending more on health than many countries in west Africa (mostly from out-of-pocket payment), Nigerians have a lower life expectancy (54 years) than many of their neighbours. Nigeria's lower life expectancy is partially due to having more deaths in children of 5 years and younger than any other country in the world, including more populous India and China and countries experiencing widespread long-term conflict, such as Somalia. Chronic diseases and a high infectious disease burden, and an ever-present risk of epidemics of Lassa fever, meningitis, and cholera, present additional challenges. A rising population and inadequate infrastructure development over the past 30 years have contributed to increasing deaths from trauma through road injuries and conflicts driven by inequitable distribution of resources.

Addressing Nigeria's health challenges requires a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach to prevent ill health. This means investing in highly cost-effective health-promoting policies and interventions, which have extremely high cost–benefit ratios, and offering clear political benefits for implementation. Interventions are needed to improve child nutrition, reduce indoor and outdoor air pollution, address unmet family planning needs, and improve access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

Key messages.

-

•

We call for a new social contract centred on health to address Nigeria's need to define the relationship between the citizen and the state. Health is a unique political lever, which to date has been under-utilised as a mechanism to rally populations. Good health can be at the core of the rebirth of a patriotic national identity and sense of belonging. A commitment to a “One Nation, One Health” policy would prioritise the attainment of Universal Health Coverage for the most vulnerable subpopulations, who also bear the highest disease burden.

-

•

We recommend that prevention should be at the heart of health policy given Nigeria's young population. This will require a whole-of-government approach and community engagement. An explicit consideration of equity in the implementation of programmes and provision of social welfare, education and employment opportunities should be paramount.

-

•

We propose an ambitious programme of healthcare reform to deliver a centrally determined, locally delivered health system. The goal of government should be to provide health insurance coverage for 83 million poor Nigerians who cannot afford to pay premiums. Implementation of a reinvigorated National Strategic Health Development Plan (NSHDP III) should be supported by structured and explicit approaches to ensure that Federal, State and Local Governments deliver and are held accountable for non-delivery. NSHDP III should be supported by a ring-fenced budget and have a longer horizon of at least a decade during which common rules should apply to all parts of the system.

-

•

At the same time, the system should encourage innovation. Future health system reform should engage communities to ensure that existing nationally driven schemes have local buy-in and are sustainable. Further, since more than 50% of health services are provided in the private sector, often with poor quality and high costs, reforming the policy and regulatory landscape to unleash the market potential of the private sector is important.

-

•

We outline options for improving health financing and ensuring better accountability and distribution of resources. The rationalised governance schemes we have proposed should improve the efficient use of existing resources devoted to health. Ultimately, the proportion of spending allocated to health needs to be increased. We envision a future of Nigeria's health without foreign aid. This will require substantial increase in domestic investments. Foreign aid (multilateral, bilateral, and philanthropic) has led to fragmentation of the already complex health development landscape, with huge asymmetries in legitimacy between foreign actors and the Nigerian state as well as weak accountability. Defragmenting and decolonizing the Nigerian health landscape requires domesticating health financing.

-

•

We recommend a whole system assessment of the invest-ment needs in Nigeria's health security. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the weaknesses of Nigeria's health security system. Nigeria needs better manufacturing capacity for essential health products, medicines and vaccines, the provision of diagnostics, surveillance and preventive public health measures in health facilities and community settings, as well as other preventive and curative measures.

-

•

We call on the Federal Government, working with state governments, to fund and lead the development of standards for the digitisation of health records and better data collection, registration and quality assurance systems. A National Medical Research Council with 2% of the health budget and central government funding to award competitive peer reviewed grants will support high quality evidence and innovation.

Governance and prioritisation of health are the first places to start

We call for the thoughtful use of existing institutions as an approach to achieve better governance and prioritisation of health. Although corruption has undermined the Nigerian health system, we can harness existing institutions for the benefit of population health. All levels of Government in Nigeria (federal, state, and local), and traditional leadership structures, civil society, the private sector, religious organisations, and communities, influence health.

Efforts towards a balance between centralisation and localisation should focus on common policies, standards, and accountability. Concurrently, there is an equal need for localisation of implementation, meaning actual community and local government ownership of health service delivery. All three levels of Government are crucial, and we provide recommendations for each level. Differences in regional needs and context must also dictate programmes and interventions. What is needed in the northeast, in a context of ongoing insecurity and a crisis of internally displaced persons, is quite different from needs in wealthier, more secure urban centres, or in the face of the different level of insecurity found in oil-producing areas in the Niger Delta.

Prioritisation of health requires additional funds. We have provided a clear investment case on health to convince politicians and governments that improved population health will reap political, demographic, and economic dividends. Our call for a whole-of-government approach to health will allow the delivery of multisectoral policies to address the social determinants of health, prioritise health-care expenditure to major causes of burden of diseases, and substantially increase healthy and productive lifespans.

Leapfrogging the health system into the 21st century

Nigeria's health system was built in an ad hoc way, layering traditional community health systems with colonial medicine aimed at maximising resource extraction. This origin has resulted in inbuilt inequalities, a dysfunctional focus on curative care, and a detrimental social distance from users and communities. Post-independence policies to redress problems have only been partially implemented.

However, the current health system is sprawling, multifarious, disintegrated, and frequently inaccessible, with very minimal financial risk protection and low financial accessibility of services. Nigerians variously seek care from medical personnel and auxiliaries, community health workers, medicine vendors, marabouts and spiritual healers, traditional birth attendants, and other informal providers. The system relies on a mixture of quasi-tax-funding, fee-for-service, and minimal health insurance coverage.

What kind of health system do Nigerians deserve, and should the country's leaders work towards? The core need of most Nigerians today is for accessible basic health services, and for this to be achieved, improvements in public sector delivery supported by an enhanced complementary private sector, including faith-based organisations, is the way forward.

We lay out a path for Nigeria to move towards a system that, although remaining diverse, better serves the needs of the population. Within this diversity, we believe there is an opportunity for a “one nation and one health” approach, whereby Nigeria guarantees a minimum standard and delivery of health care for all with an emphasis on strengthening public and private (including faith-based and non-profit) systems. Nigeria should also leverage the private sector for certain functions, such as expanding innovation, discovery, and manufacturing capacities to claim a leadership role on the African continent and globally. Government investment in private industry should be mission-driven, supporting innovation and claiming dividends for society from its investments.

Core functions of the health system require immediate attention, in particular, good quality health data. This Commission strongly recommends better recording, storage, and use of data. Paper systems are unworkable. A drive towards digitisation can result in major improvements, for both patient care and devolved health decision-making. Mobile digital technologies should allow a relatively rapid expansion of population health data and linked existing datasets. Human resources in rural and poor regions of the country are worsened by brain drain. We propose prioritising the optimal development and redistribution of health workers at all levels.

Financing health for all by rationalising contributions from insurance, out-of-pocket payments, donor funding, and taxes

A viable health system requires dedicated, efficient, and equitable health financing mechanisms, complemented by optional health insurance. Countries with systems comparable with Nigeria's, such as Ethiopia and Indonesia, have planned or implemented ambitious programmes to deliver health insurance coverage.

Nigeria's public health system should be supported by a comprehensive health insurance system for all people, funded using through both contributions and taxation, with trials underway in states such as Anambra. Access to health insurance for society's most vulnerable people must be government funded. Considerable political will is needed to bring a greater proportion of the informal sector accessed by most Nigerians under government governance mechanisms.

There is also a need to expand the fiscal space by increasing overall government revenue, which will lead to higher health funding, allowing health and the determinants of health to be addressed. Achieving these financing goals will require an optimistic political economy approach, considering current context, alongside future steps. A starting point could be explicit declaration by governments at all tiers that the achievement of universal health coverage is a priority goal.

Nigeria is a country with so much wealth in terms of human talent and potential, but also beset by challenges, including inadequate provisions for optimal health-care delivery and well-being of its people. For Nigeria to fulfil its potential, the leaders and people alike must embrace the implications of what they know already—that health is wealth.

Section 1: introduction

Nigeria is at an important crossroad. Nigeria's population is projected to increase from approximately 200 million people in 2019 to an estimated 400 million in 2050, and 733 million people by 2100,1 becoming the world's third most populous country after India and China. These estimates assume that the average number of children per mother will decline from 5·1 currently to 3·3 on average by 2050 and 2·2 children on average by 2100. If this projected decline in fertility is to fall short by half a child per mother, Nigeria's population will reach 985 million by 2100. The potential gain from this expansion will only be possible if population growth is managed and supported by equitably distributed prosperity. A rapidly rising population, coupled with the absence of reliable access to high-quality health care, education, and other public services will serve only to increase the potential for unrest, drive large-scale unplanned migration, and consequent regional and even global destabilisation. A large population of uneducated and unemployed youth risks further instability and security challenges.2 These demographic and socio-economic challenges are further compounded by climate vulnerability. Nigeria is one of the ten countries most vulnerable to climate change3 due to extreme weather, rising sea levels, and increasing land temperature.4

Conversely, a healthy and secure Nigerian population living within planetary boundaries could make untold contributions to human progress, now and in the future. Accordingly, integrated efforts to address health inequalities and climate vulnerabilities is a crucial priority for the country.5 If the right policies are implemented, Nigeria is poised to become a global superpower.6 Nigeria's significance to global health and the health of Africans is self-evident, particularly considering its large and mobile population.7 Major health gains in Nigeria should improve health outcomes in Africa by directly improving health security and through the sharing of good practice and policy to neighbouring nations.

But Nigeria faces numerous challenges in confronting both population growth and climate vulnerability ensuring a healthy future for its population. The country did not achieve any of the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and progress towards health-related Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets has been modest at best.8 According to almost all health metrics, Nigeria's health outcomes are dismal with inadequate progress made over the past three decades for the majority of its population. Investment in health is low at 4% of GDP in 2018,9 whereas substantial resources continue to be spent fighting insecurity without addressing its root causes, and sustaining a large and complex governance structure, with too little left over for health and education. The macro-fiscal environment is not favourable, with only modest economic growth and a sharp worsening of the economic outlook due to the COVID-19 pandemic.10 Conversely, given Nigeria's low starting base, reforms towards achieving universal access to high-quality public health services have the potential to achieve large positive effects on population health outcomes.

Despite its considerable human and material assets, achieving universal health coverage will be challenging. The modest resources allocated to health have been mismanaged by successive governments since independence in 1960. A series of national plans, strategies, and policy documents have only ever been partially implemented, with missed opportunities to apply health as a tool for development. Given the scale of the challenge, there has also arguably been an inadequate focus, with the most recent plan outlining 48 strategic objectives.11 Several policy documents allude to “quality, effective, efficient, equitable, accessible, affordable, acceptable and comprehensive health care services” for all Nigerians,11 yet these goals are elusive. Nigeria's most recent development plan ended in 2020 with, at best, partial success,12 presenting an opportunity to better frame health as a determinant of national achievement in the next plan. There are immense opportunities to alter Nigeria's population health and economic development trajectory, if only they can be seized. Reducing maternal and child mortality and unmet need for family planning are basic first steps to improve families' well-being, with implications for security, resource utilisation, economic growth, and shared prosperity. Reducing the burden of HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and other communicable diseases will change the epidemiological landscape, allowing greater scope to simultaneously tackle rising non-communicable diseases. Taking bold multisectoral preventive action on the determinants of health can in turn prevent and even reverse the rise of non-communicable diseases. Government action needs to move away from treating disease to creating health. And importantly, such efforts must be integrated with climate action for healthy resilient futures.

The Lancet Nigeria Commission aims to reposition future health policy in Nigeria to achieve universal health coverage and better health for all. A detailed critical evaluation of the historical and current challenges facing the health of the country is presented to contextualise recommendations for the future. There is a distinct opportunity to redefine the national social contract using health benefits to the most vulnerable households as a key element of the relationship of citizens to the state. And despite the country's reputation for intractable governance, developments over the past two decades have shown that positive reforms are possible. The initiation of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund scheme and the introduction of state health insurance have provided an important starting point for future reform towards universal health coverage. Improvements in infectious disease surveillance led by the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) have resulted in timely national data reporting on outbreaks of COVID-1913 and monkeypox.14 Similarly, the completion of the largest ever population-based HIV/AIDS survey by the National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA)15 within the allocated budget and on time illustrates what is feasible. Success will depend on effective implementation of a coherent set of policies, by translating evidence into action and measuring effects on population health. In this Commission, we aim to present a new path to better health with consequences on development, wealth creation, and strengthening of human capital, notably by proposing comprehensive approaches for improving all components of health care in Nigeria (panel 1).

Panel 1. Overview of Commission recommendations.

Nigeria has a great opportunity to implement policies that effectively promote population health. Well-intended and seemingly well-designed policies, including most recently the second National Strategic Health Development Plan (2018–22), have often struggled in the past to meet objectives due to poor coordination of a complex multipartner system in the implementation phase and insufficient stakeholder and community engagement, inadequate legal frameworks, perverse incentives, insufficiently robust accountability mechanisms, inadequate adaptation to Nigeria's federal structure, and suboptimal allocation and utilisation of funds. There is now a chance that Nigeria can build on lessons of the past to chart a new course into the future.

Our recommendations build on lessons from within Nigeria's national and state health systems and the experiences of countries that have been more successful in tackling similar challenges. Some of these would require modest resources and be easier to implement, whereas others would require consultation and more fundamental reform. Building on the work of colleagues, we reiterate and reinforce recommendations from previous policy documents, adding evidence-based views on how they can be implemented and by whom.

We call for a new social contract centred on health as a transformational way to define Nigeria's relationship between the citizen and the state. One approach to achieve this goal is committing to a “One Nation, One Health” policy, by offering Universal Health Coverage through greater allocation of ring-fenced resources underpinned by strong accountability systems. This slogan also makes a rhetorical link to the One Health paradigm, which recognises the interconnection between all people, animals, plants, and their shared environment, and the need for a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach at the local, state, and national levels. Nigeria should also radically revisit its strategy in seven key areas connected to health.

Recommendation 1

Political leadership should operationalise previous recommendations to adopt a multisectoral response to health (ie, Health in All Policies) via cabinet-level orders to implement a whole-of-government approach. Each government agency should define goals and indicators aligned to achieving health targets, led by the presidency and with strong funded coordination of the complex multipartner structure by the Health Ministry, National Economic Council, and state governments to:

-

•

Prioritise health investments to address key social determinants of health including adequate sanitation, access to clean air and water, and food security, especially for children

-

•

Consider a standing multisector council on hygiene to coordinate actions of various stakeholders towards prevention

-

•

Enforce existing government policy and regulation on products that are known to be detrimental to health and elevate the risk of non-communicable diseases including sugar-sweetened beverages, ultraprocessed foods, skin lightening cosmetics, and tobacco as outlined in the 2019 National Multisectoral Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of non-communicable diseases, through non-regressive levies and taxation

-

•

Address population growth through improving access to modern contraceptive methods at all health-care levels, female education, and increasing the age of sexual debut

-

•

Adopt an integrated planetary health governance approach, including tackling sources of indoor and outdoor air pollution, and other environmental risk factors, in rural areas and urban centres with a focus on protecting the poor through improved housing and access to clean cooking fuel and enforcing limits on pollution from industrial and transportation sectors, and incentivising transition to renewable energy sources such as solar energy—Kenya provides an example that could be emulated, with the inclusion of health impacts and health in climate adaptation measures into Nationally Determined Contributions, placing health at the centre of policies to reduce emissions in the energy, food, agricultural, and transport sectors for both health and economic returns.16

-

•

Integrate health and health service delivery into climate adaptation strategies (examples include integrated surveillance of flood risk and water-related illnesses, climate vulnerability assessments of primary care clinics in communities to limit service delivery interruption in the event of extreme weather events, and urban design that ensures equitable access to green space to reduce land surface temperatures and heat-related illnesses)

-

•

Ensure a multisectoral response that is implemented by Functional Health units, which should be opened in all ministries, departments, and agencies at the federal and state levels where they do not exist, which would ensure that all ministers have a planetary health portfolio with the explicit responsibility of assessing the human health and ecological impact of any decisions, strategies, and policies;17 using the performance of this portfolio as an indicator against which all sectors are assessed to encourage and support health creation that is cognisant of climate realities

-

•

Explicitly require equity assessments in the implementation of programmes and provision of social welfare, education, and employment opportunities by federal and state governments

-

•

Systematise a delivery approach across the spectrum—performance management and accountability systems, building on successful application of Emergency Operations Centres as delivery units.

Recommendation 2

Federal government, with full engagement of the National Assembly, state and local governments, civil society organisations, the private sector, community groups, development partners, and technical oversight and funded coordination of implementation by the Ministry of Health, should lead a comprehensive reform of the health sector, led by the presidency, to inform the next National Strategic Health Development Plan (NSHDP III) premised on a collectively determined but locally delivered health service, building on policy reforms over the past two decades

-

•

Unify national health delivery standards, improve supply chains, and incentivise manufacturing through national legislation, with funding from the federal level in consultation with state governments

-

•

Build the capacity of local government health officials to deliver basic health services and products based on minimum national standards through state government legislation to prioritise health and support local government implementation

-

•

Define responsibility for governance, purchasing and provision in the health system with oversight and policy formulation led by the Federal Ministry of Health at the national level and State Ministries of Health at the state level

-

•

Maintain high-quality state-government services and enable private sector-run health-care services that are evaluated using federally-led performance management systems for monitoring, evaluation, and quality assurance, using best practices for incentives and penalties linked to targets

-

•

Ensure that auditable public financial management and accountability mechanisms for commissioning and purchasing are developed to improve transparency, efficiency, and equity, and eliminate corruption in the deployment and use of resources

-

•

Build on the improvements in national and state level surveillance and diagnostics achieved through the response to COVID-19 and allocate specific resources to ensure sustainability

-

•

Unlock the potential of health-care markets across the value chains

Recommendation 3

The federal government should lead efforts to improve health financing (ie, revenue mobilisation, pooling and management of funds, and purchase of services), aligning the investment case with political incentives, levers of accountability, and the rhetorical appeal of “health for wealth” among the Nigerian population. To achieve these improvements the government should:

-

•

Establish legally ring-fenced predetermined health budgets outside of the electoral cycle, which occurs every 4 years to ensure sustainable funding and strategic planning building on the Basic Health Care Provision Fund, and using the third National Strategic Health Development Plan to reach the goal of 15% of the annual budget allocated to health

-

•

Establish structural reforms to withdraw inequitable subsidies towards financing health and social services building on lessons from the Presidential Task Force on COVID-19 (eg, 1·5 trillion Naira in petroleum subsidy can free up fiscal space to be redirected towards health)

-

•

Fund health insurance coverage to all Nigerians by paying the estimated 15 000 Naira per capita annual premium for 83 million least wealthy individuals (approximately 40% of the population) with revenue raised through the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund, taxation, and levies, and each state to fund residents through their state health insurance scheme supported by a national mechanism to assure quality; today, it would cost 1·2 trillion Naira or 9% of the current budget to cover individuals who cannot afford to pay current premiums in National and State Health Insurance Schemes

-

•

Improve the efficiency of systems for pooling and purchasing of health finances by establishing national and state purchasing organisations with oversight for allocation of funds, raised through revenues generated from taxation, levies, or donors, and the payer at each level should use strategic health purchasing to provide more health services using available resources

-

•

Increase the national fiscal space for health through more efficient tax collection (company profit tax, and capital gains) and through innovative health financing such as levies on commercial services (eg, mobile phone use, financial transactions, and air travel) to reach the existing goal of reducing the proportion of out-of-pocket expenditure to below 30% by the end of NSHDP III and improve health outcomes

-

•

The federal government should anticipate donor transition and prepare for post-aid status in which technical assistance, knowledge, and learning are more relevant than donor projects, which will require domesticating financing of health, research, and development, to achieve health independence and decolonise the Nigerian health space. Local institutions must be prepared to step up.

Recommendation 4

Federal and state governments should leverage public–private partnerships based on accountability, mutual trust, information sharing, and joint planning to overhaul Nigeria's dilapidated hospital infrastructure and support manufacturing by:

-

•

Creating an enabling environment for functional health markets while protecting the poor, supported by sound policies, regulations, and access to long term capital

-

•

Using private sector capital to modernise and expand the capacity of hospitals with appropriate accountability mechanisms

-

•

Investing in a coherent state supported and private sector-led approaches to increase local production of vaccines, medicines, and other health products and services

Recommendation 5

Federal and state governments should collaborate to address deficiencies and imbalances in the health workforce by engaging in dedicated planning to train and retain adequate numbers of staff at all levels.

-

•

State Ministries of Health should, based on national standards, engage in regular workforce planning reviews to determine the number and type of staff needed at regular time horizons and establish incentive systems to allocate health workers appropriately and specifically increasing incentives to work at primary health care level

-

•

State governments should work with the main health worker regulatory bodies to ease the process of licensure and tracking of members at state level

-

•

The federal government, through the Ministry of Education, should consider expansion of quality medical and allied health professional training to boost human resources and talent

-

•

Federal and state governments should jointly develop and implement strategies to retain staff through career development support, appropriate remuneration and other measures to discourage brain drain between rural and urban areas and internationally

Recommendation 6

Federal and state governments should actively manage the demand for health and health services by engaging communities, with a focus on areas such as vaccine hesitancy and the quality and acceptability of government-provided maternity services

-

•

Using adapted guidance from the federal level, local governments should conduct regular consultations to gain a full understanding of community health needs and desires and co-create delivery systems that respond to these needs while ensuring minimum national standards

-

•

State and local governments should establish state-level health forums that meet every 6 months to address local issues with membership drawn from Ward Development Committees across the state

-

•

The federal government should create a national health forum as a deliberative platform for bringing together a wide and inclusive range of stakeholders to discuss complex health challenges, and to provide meaningful and substantive input to NSHDP III

-

•

The federal government should strengthen the voice of citizens using technological and mobile platforms to amplify voices of citizens on needed reforms and accountability

Recommendation 7

Define and urgently implement enhanced research and data systems to support planning, monitoring, and accountability at all levels

-

•

The federal government should create a Nigeria Medical Research Council, with permanent federal funding, to strengthen and coordinate health and health-care research; the establishment of the council should be informed by a thorough review of existing research to know where the gaps are. A competitive funding programme targeting investigators at universities, hospitals, and research institutions and complementing other extramural funding systems such as the TETFund should identify research areas based on Nigeria's burden of disease, with priority given to conditions affecting the poorest and most vulnerable

-

•

The federal government, through the Ministry of Health and National Bureau of Statistics, should set national standards for the digitisation of health records, building on existing systems such as District Health Information System version 2, the Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System, and the National Health Logistics Information System to improve preventive and curative care, support decision making, and guide system management at all levels. Local and state governments should maintain ownership of local digital infrastructure, using federal funds. Data assurance mechanisms based on a non-blame culture and regular audit cycles improving the quality and timeliness of information, combined with rapid feedback and local use of all collected data, will show value. Federal and state governments should co-fund these data systems, including the cost of internet access for all health workers and access to appropriate technology. The evidence we have reviewed in this Commission suggests digitisation is good value for money

-

•

Federal laws should link access to services and entitlements with registration of births and deaths, and systems to show the value of such data for the economy and to achieve the engagement of civil society. Federal, state and local governments should review existing legislation and develop an action-oriented implementation plan to improve vital registration systems in close collaboration with local stakeholders and institutions such as religious and traditional leaders

Post Commission phase

This Commission aims to inspire the next phase of Nigeria's health journey, using evidence-based recommendations to influence the programme of work of the Nigerian Government and its development partners. In tandem with this Commission, we have designed a programme of strategic engagement with key influencers in and out of government, at federal and state levels, to ensure wide dissemination and uptake of key messages among the broader community of policy actors, including the National Assembly. For specific policy makers, we will disseminate the evidence generated through policy briefs and policy roundtables. We will also use the report to generate further discussions using targeted convenings, innovative science-arts approaches, media outreach including via high profile opinion pieces and social media-based delivery of tailored messages for key audiences, including civil society and development partners.

We also hope and expect that co-production of the evidence presented here with members of the target audience, the Nigerian health policy community, will facilitate appropriate and prompt dissemination of our recommendations. We also acknowledge that positive attitudinal change by both the leaders and citizens is key in achieving optimal health outcomes and prosperity in the country. Several senior leaders in the health sector and beyond are contributing to the public engagement strategy to ensure the Commission reaches the right actors. It is intended that through liaison with the two major political parties and by influencing the planned Health Reform Committee of the current government, this Commission will directly set the pace for changes over the next decade. We will continue as a group of experts to work with civil society groups, the Nigerian Government and the legislature to advocate for the changes recommended in this Commission and summarise progress towards implementing the recommendations in future reports and on the Lancet Nigeria Commission website. By setting out the challenges, synthesising the evidence, and outlining bold recommendations for action, this Commission presents an opportunity for Nigeria to achieve optimal health outcomes and prosperity ensuring that “health is wealth”.

Our Commissioners combine expertise in the diverse disciplines required to shape national health policy, including public health and epidemiology, political science, history, economics, public policy, sociology, demography, law, anthropology, and health systems. We ensured representation with respect to gender and local origin, included a range of political and health policy views among experts based within and outside Nigeria, and consulted with a diverse group of policy stakeholders to provide insight into the challenges of delivering health and health care in Nigeria. From the outset, we set a 10-year timeframe for our analyses, looking beyond the lifespan of the current Nigerian Government, to ensure relevance to current and future administrations in Nigeria. The core values that underpin this Commission are fairness, equity, pragmatism, and evidence-driven approaches.

The Commission focuses on generation and synthesis of evidence to inform policy and programme implementation, with a view to building a strengthened health system that meets the needs of all Nigerians. First, we review Nigerian history to understand current structures and systems by rooting them in pre-colonial, colonial, and modern-day trends and events. Second, we analyse the country's disease burden, the major causes of morbidity and mortality based on the best available data and models, and projected future trends where possible. Third, we analyse Nigerian health systems and policy, and intersectoral governance and policies that influence health beyond health care, and articulate key challenges and suggested systems-level leverage points. Fourth, we combine health economic analyses with the work on disease burden to generate evidence on the most cost-effective combination of interventions to achieve health goals and summarise approaches to improve health financing. Our concluding section brings together these analyses in the form of specific recommendations and an agenda for action. Finally, we use case studies throughout the Commission to illustrate the lessons, gaps, and opportunities for action. Well-functioning health systems generally prevent maternal, neonatal, and child deaths, and thus we have presented one case study per section of the Commission on this subject.

Section 2: evolution of a health system skewed away from population needs

Pre-colonial community health systems provided broad access to holistic care

Organised systems of health-care delivery and disease control have long been present in the territory now known as Nigeria. In the centuries preceding colonial rule, this region was governed by the Hausa States and Kanem-Bornu Kingdoms in the north and the Oyo and Benin Kingdoms in the south. In the southeast, the Igbos used an alternative, more decentralised, governance system, as did numerous other ethnic groups (over 350 ethnic groups inhabit the country today).18 Each sovereign area operated its own form of traditional medical care. The dibia of the Igbo peoples, wombai of the Hausa, and the adahunse of the Yoruba peoples were widely trusted to deliver traditional medical care.19 Although belief systems and social structures, including health care, varied across these societies, the practice of divination, incantations, exorcism, and other spiritual practices to provide care was commonplace in pre-colonial Nigeria.18 Diagnosis and treatment were based on notions of complete therapy and cure, accounting for the individual patient's cultural, social, and physical environment. In particular, diagnosis included sociocultural analysis of the patient's situation, and therapy was sometimes an avenue to cement fragmented relationships between individuals and offended spirits.20, 21 As many still do today, traditional medical practitioners used leaves, roots, tree bark, animal parts, and minerals from the soil in preparing remedies to heal or prevent unpleasant health events in the lives of their clients.19

Health systems were structured so that every community had a full-time healer and nearly every extended family had a part-time healer who could treat common minor ailments.20 More serious health problems were referred to a qualified medicine man or woman, as indeed the agricultural surpluses of pre-colonial economic systems allowed for the creation of specialist trades.20 Although some healers possessed an integrated body of knowledge of the causes and treatments of diverse illnesses, others (eg, medicine men, diviners, midwives, magicians, bonesetters, and barber-surgeons) concentrated on specific biopathological and social aspects of health. In each community or village, it was not uncommon to find specialists who attended to pregnancy and birth, child health, general welfare, bewitchment, diarrhoeal diseases, and complicated cases such as arthritis.20 Consequently, all members of society had access to some basic health services from a healer.19, 22, 23 In modern terms, the health-care delivery could be said to follow a community-based approach, rendering it accessible to much of the population,24 with referral systems to specialised healers. Patients with chronic illnesses or incapacitated individuals (eg, people with severe mental illness and leprosy) stayed in special treatment rooms in the practitioner's compound until they were better, whereas those with acute or non-incapacitating illnesses (eg, childbirth or delivery complications, accidents, and bewitchment) were usually treated in their own homes.

However, pre-colonial Nigeria was not a classless society and so access to some health services was unequal. Although treatment and care were sometimes paid for in kind,19 those with greater wealth, power, and prestige had more access to the most expensive forms of medicines available, such as for bewitchment.25 During the period of state formation that preceded colonialism, population inequities grew substantially. Currency devaluations (in currencies including cowrie shells and copper manillas) and the increasingly virulent trade in enslaved people resulted in societies that were more militarised, stratified, and predatory, sowing the seeds of mistrust of government authorities that is still a factor in state–society relations today.26 Yet during this era, the role of the traditional healer was not (fully) commodified; in all ethnic groups, healers had a common role of providing care to all individuals in their communities.

Colonial health care services laid the foundation for today's inequitable health system

The introduction of Western medicine to Nigeria's pre-colonial societies began with the first incursions of western European traders in the early 15th century and was linked to primarily commercial and extractive ends. During the transatlantic slave trade beginning in the 16th century, doctors were brought to deliver health-care services to slave traders and later to guarantee traders' investments by assessing enslaved people's fitness for travel.27 Endemic diseases such as malaria largely impeded European incursions into the interior of the continent. However the use of quinine as prophylaxis and therapy for malaria beginning in the mid-19th century was a major boon for the imperial agenda,27 making it easier for Europeans to stay longer, venture further inland, and engage local chiefs and kings in treaties of commerce and so-called friendship, ultimately allowing effective colonisation.

Early colonial authorities established health facilities in cities and towns near the Atlantic coast in Lagos and Calabar, and in Lokoja, the capital of the British Northern Nigeria protectorate, for the use of European merchants, military men, colonial officials, and, much later, Africans employed in mining and construction.27 As colonialism gained momentum from the 1860s onwards, mission hospitals also began to appear. Like colonial government hospitals, these were concentrated in Lagos (table 1). Mission hospitals were rarely funded by the colonial government, yet they served the political interest of promoting colonial rule, as preferential treatment was given to Nigerians associated with the Christian mission.29 With health services concentrated in urban areas, there was little to no provision for people in rural areas who were less economically valuable to the imperialists. The colonial state-organised Rural Health Units were stifled by funding shortages.30 Indigenous healers were still the main providers of health services to most of the population.

Table 1.

Regional distribution of Nigerian hospitals (1895–1960)21 alongside estimated population (1963)

| North | East | West | Lagos | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | 39 | 26 | 24 | 12 | 101 |

| Mission | 31 | 16 | 1 | 70 | 118 |

| Unknown* | 14 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 31 |

| Total (%) | 84 (34%) | 53 (21%) | 30 (12%) | 83 (33%) | 250 (100%) |

| Population – Total (%)† | 29·8 million (54%) | 12·3 million (22%) | 12·8 million (23%) | 675 000 (1%) | 55·6 million (100%) |

Leprosarium, nursing homes, and others. Could include some government-owned and mission-owned facilities.

Data are from the Institute of Current World Affairs28

Colonial medical services established the basis for Nigeria's medical and nursing schools, and introduced primary health care (PHC) and hospital care grounded in allopathic medicine. However, the extractive colonial agenda shaped Nigeria's nascent allopathic health system in other ways. The colonial state showed a particular concern for maternal and child health as reproduction promoted population growth and therefore, the expansion of British imperial interests.31 Somewhat paradoxically, British health services otherwise maintained a curative bias, with much less emphasis placed on preventive activities such as immunisation, health education, and environmental sanitation. Environmental health campaigns were generally aimed at protecting the European population; for example, Governor of Lagos' massive antimalaria campaign that was initiated around 1900 drained swampy areas and sprayed insecticide to prevent mosquito breeding. Boots, nets, and quinine were distributed only to government officials and their families. Even in the late colonial era, campaigns like the Rockefeller Foundation-funded Yellow Fever Initiative in West Africa, were motivated more by global biosecurity concerns stemming from the rampant spread of yellow fever in countries including the USA, rather than by concern for Africans' health.32

The human resource demands of the pre-colonial health system were initially met primarily by European doctors and medical staff. Under the sponsorship of the Church Missionary Society, James Africanus Beale-Horton and William Broughton Davis were the first Nigerian doctors trained in Scotland in 1858, although neither practiced in Nigeria.33 The first Nigerian doctor to practice within the country was Nathaniel King who qualified in 1874.33 It was not until 1930 that the Yaba Medical Training College in Lagos began training assistant medical officers, and it was not until 1952 that the first teaching hospital in Nigeria, the University College Hospital Ibadan, was established, finally allowing for domestic training of medical and nursing personnel. After the World War 1 and World War 2, many Nigerian physicians became members of the Nationalist Movements demanding better conditions and equality from the colonial government.34, 35 One response of the colonial government to nationalist agitations was to extend modern health services to all Nigerians, one of several factors leading to the issuance of the 10-year National Development Plan (1946–1956), which projected the building of new hospitals, rural health centres, and nursing training schools. It was during this timeframe that a Ministry of Health was established and health services from all stakeholders, such as the missionaries, colonial government, and trading companies, became centralised. However, the plan continued the prior emphasis on curative services, and there was no budgeted funding for sanitation, health education, or other preventive health-care services. Most new health facilities were in the southern region of Nigeria, mainly in urban areas, as opposed to the rural areas where they were most needed.20

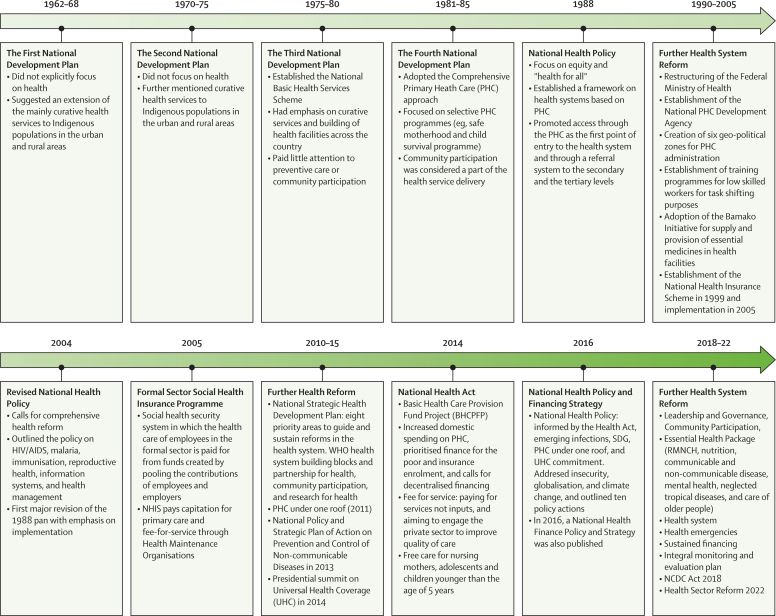

Independent Nigeria's recurring crises and governance challenges hinder efforts to improve population health

Nigeria's independence in 1960 ushered in new hopes to realign state and society and re-orient public spending and governance towards the good of the population. For example, in the 1960s, following the Ashby Commission report,36 second-generation medical schools were established in Zaria in the north of Nigeria, Lagos and Ilé-Ifé̀ in the west, and Enugu in the east. Unfortunately, recurring economic crises and ongoing political instability, with a series of military coups in 1966, 1975–76, 1983, 1985, 1993 and persisting until 1999, created a challenging environment for sustained reform. Since the return to democracy in 1999, the political situation has arguably stabilised, albeit with ongoing popular agitation rooted in grievances about the allocation of political and economic benefits. Insecurity is still a major problem in many parts of the country, as are fragile and incomplete democratisation and fiscal weakness. Taken together, these trends have complicated durable progress towards improving population health.27

The development of the PHC system in the 1980s and the 1990s under the leadership of Professor Olikoye Ransome-Kuti is a notable exception. Prof Ransome-Kuti, as the health minister, helped develop the first National Health Policy in 1988, and led the introduction of the PHC model in 52 pilot Local Government Areas (LGAs), with the primary focus of promoting preventive medicine at the community level. Among other successes, child immunisation coverage reached over 80% by 1990, meeting the Universal Child Immunisation target.37 To ensure the continued progress of PHC service delivery, the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) was established in 1992. However, the 1993 military coup d'état hastened the collapse of the PHC system and brought an end to the giant strides recorded under the leadership of Ransome-Kuti from 1985 to 1992, and other successes from that period, for example in immunisation coverage, have also not been sustained to the present day. Although PHC is a focus of health reforms—for example with the 2011 Primary Health Care Under One Roof policy, which integrates PHC service delivery under one authority—implementation by states and local governments has been slow and fragmentary.

Key informants familiar with the development of the Nigerian health system in the post-independence period offered varying explanations, many of which appear linked to underlying political issues such as citizens' inability to hold leaders to account (panel 2). Although the colonial inheritance of a generally weak, unequal, curative-oriented system offered a poor start to independent Nigeria, there has arguably been a failure to re-establish a social contract, including an underlying ethos and expectation of the government's duty to provide health-creating conditions, including a functioning basic health system.

Panel 2. Key informants' views of constraints to the development of the Nigerian health system in the modern era.

We interviewed key informants with direct personal knowledge of the development of the Nigerian health-care system in the modern post-colonial era. Respondents included professors of medicine, former ministers of health, and traditional rulers. They identified key determinants in the development of the national health system:

-

•

Political volatility and constant shifts in political structures meant that positive health reforms were not sustained and consolidated into durable health systems improvement

-

•

Development plans were ineffectively implemented and deployed due to delayed execution, neglect of community stakeholders, non-involvement or limited consultation with medical experts, inadequacy of resource commitment, and neglect of integral policies and institutional structures to enable continuity

-

•

Infrastructural projects were prioritised instead of fundamental development projects designed to effectively tackle Nigeria's persistent health system deficiencies

-

•

Political leaders perceived that investing in the development of efficient health structures would not yield immediate returns, both economically and in terms of goodwill and attribution of success from the served population

-

•

Inadequate funding resulted in degradations of infrastructure and human resources, including the so-called brain drain of qualified personnel

-

•

Constitutional provisions for health are vague, resulting in unclear distribution of responsibilities across governance levels

-

•

Primary health care reform attempts were undermined by a failure to engage with communities to raise awareness, clarify individual responsibilities, or solicit inputs in the reform processes

-

•

Attempts to restructure the three tiers of health-care service delivery occurred in complete isolation, leading to the overburdening of whichever tier was most functional at the period in question

-

•

Political attitudes characterised by narrow individualism and widespread corruption have played a major role in perpetuating the current dysfunctional state of the health sector

See appendix for methodology

One key challenge has been Nigeria's complex, opaque, and poorly specified governance arrangements, which obscure constitutional responsibility and accountability. Since 1979, Nigeria's federal presidential system has divided responsibilities between federal, state, and LGAs, and although the 1999 constitution asserts that “The State shall direct its policy towards ensuring that there are adequate medical and health facilities for all persons” 38 (a provision it transparently does not meet), little further detail is enshrined about how this entitlement is meant to be delivered. Since the 2014 National Health Act, the tertiary level of care is nominally the responsibility of the federal government, states manage secondary healthcare, and the primary level, including PHC centres, are managed by LGAs. In reality, the separation is non-existent as states still have their own tertiary care facilities, whereas for primary care, the federal government provides a regulatory advisory function, alongside centralised provision of some services (such as immunisation) and finances infrastructural improvements through the NPHCDA. The poor delineation of responsibilities among these levels has resulted in a complex and contested distribution of resources, a referral system widely agreed to be defective, and an unclear responsibility structure that frequently results in neglect at all three levels. This division of responsibilities partly explains why primary care is generally weak in Nigeria as responsibility for this critical level of care has been devolved to the weakest level of government (ie, LGAs) while control of primary care resources is driven by the state governors.

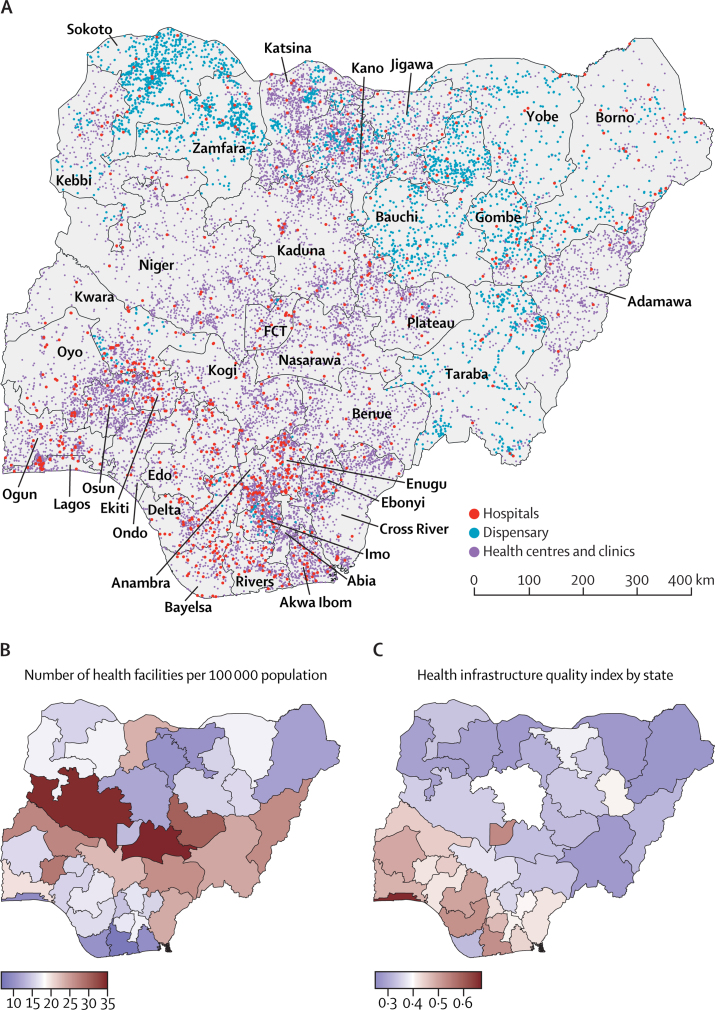

The division between federal, state, and local obligations also risks entrenching historical inequities between geographical regions, with areas that were formerly highly centralised and autonomous during colonial rule (eg, in the north of Nigeria) resisting federal autocratic regimes, which has led to retaliation through under-investment in federal services.39 These trends can help explain some of the greater concentration of hospitals (managed at tertiary level) and other formal health structures in the south as compared with the north (figure 1), despite the proportionally larger population in the north. Subsequent investment by the state governments and the private sector further ensured that the density of hospitals and health centres in the south of Nigeria improved and diverged further post-independence. Furthermore, although the rural population constitutes about 50% of residents, it is served by fewer health facilities.40, 41

Figure 1.

(A) Distribution of public hospitals, health centres/clinics and dispensaries in Nigeria (2019), (B) Number of health facilities per 100 000 population and (C) Health infrastructure quality index by state, 2012

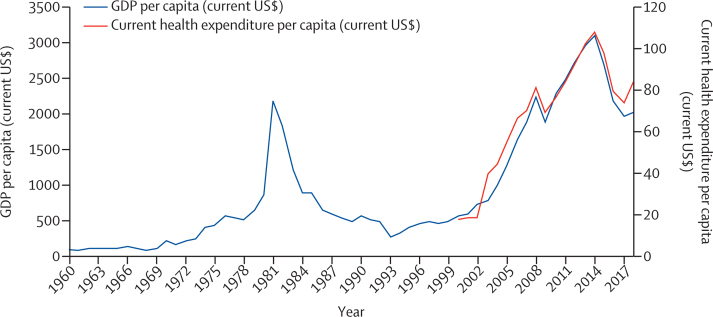

Further compounding these issues, population health has not been highly prioritised in national and state budgets throughout Nigeria's modern history. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the political will to deliver “health for all”, including universal health coverage, has been grossly inadequate, due to in part the population's limited ability to effectively demand improved health services. Since the 1970s, financial gains from oil revenues have been a funding source for health, albeit one that political leaders have repeatedly failed to harness. Political turnover has not been an impetus for change; for example, the dire state of the health system was cited as one of the reasons for the 1985 coup overthrowing General Muhammadu Buhari,42 however his successor, General Ibrahim Babangida, allocated only 2·7% of the national budget to the health sector.35 Following the collapse of petroleum prices thereafter, Nigeria was subjected to the well-documented ravages of the Structural Adjustment Programme, during which both allocation to the health sector and per capita expenditure on health were reduced.43 Out-of-pocket payments have since become the most common mechanism of financing health care for individuals and households,44 creating a cost barrier and decreasing the use of health-care services and adherence to medications. Prospective patients are thus driven to use traditional medicine, which is easily accessible and relatively affordable.

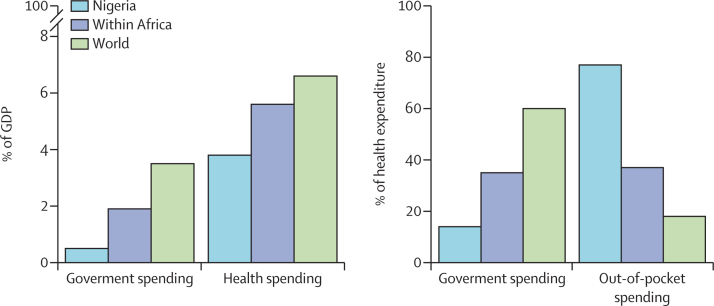

Government health expenditures have risen somewhat under the Fourth Republic, however, Nigeria's total government spending as a share of overall health spending was at 4·6% in 2017, lower than the African average of 7·2% and the world average of 10·3%.45 In contrast, out-of-pocket expenditure is extremely high, at 77% of total health spending in Nigeria, compared with 37% for the African average, and a much lower 18% for the world average. Compounding Nigeria's health inequities are low in investment in water and sanitation infrastructure compared with other low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs),46 as well as generally low government spending across sectors.

Overall, Nigeria's model of health-care financing since the First Republic has gradually transformed into one focused on the generation of revenue for hospital management through the charging of user fees. Public health centres have been pseudo-commercialised as they are restructured to generate funds to work efficiently and independently. In the public and organised private sectors, neoliberal reforms have led health-care provision to be more market-oriented, even though 60% of the Nigerian population are estimated to have minimal disposable income.47 As a result of underfunding, the capacity and quality of government health facilities and health services dwindled due to the persistent unavailability of drugs and equipment, resulting in increasing reliance on home treatment, medicine sellers, traditional medical systems, and faith healing by the Nigerian populace.48 The accumulated results of this history can be traced throughout the health system, with a case study of maternal health services providing an example of the resulting challenges and opportunities (panel 3).

Panel 3. The effect of historical trends on maternal health services.

The delivery of maternal health-care services relies on the entire health system, and systems-level issues influence access to and uptake of services, quality of care, and health outcomes.49 Therefore, the historical construction of the Nigerian health system can be examined through the lens of maternal mortality, and the diagnosis is dire. Nigeria's maternal mortality ratio (814 per 100 000 livebirths in 2019) is among the world's highest, and the country accounts for 20% of the world's maternal deaths.50 Large inequities in access to perinatal health services (including antenatal care, delivery, and post-natal care), are found along the political, social, and economic fault lines characterising the allopathic health system since its origins in the early colonial period. There are marked disparities between geopolitical zones,51 with women in northern Nigeria less likely to deliver in a health facility than those in southern Nigeria,52 and also between urban and rural areas,51, 53 with rural residents twice as likely as their urban counterparts to drop out between antenatal care and delivery. Distance to the health facility is a common barrier to accessing antenatal care and facility delivery,53, 54 compounded by poor road access and unavailability of transport late at night or during the day, especially in rural areas.55 The poorly functioning referral system, with unclear repartition of responsibilities between the three levels of governance leads to late presentation and consequent adverse maternal outcomes in tertiary facilities.56

The ability of women to seek maternal health services is substantially moderated by the cost of care, an unsurprising finding given that out-of-pocket payments have become the main source of financing of basic healthcare. High cost is a major factor hindering both the use of antenatal care services and the decision or ability to give birth in a facility.57, 58 Cost as a barrier is most pronounced in rural and semi-urban areas, and the challenge is even greater when women are referred to a higher level of care. The most common reasons for discontinuation of treatment include the cost of services, drugs, and laboratory expenses, and scarcity of transportation to the hospital (which is also often an issue of cost).59 These problems are not irremediable; pilot federal government-led initiatives that include financial incentives in the form of subsidies for antenatal care services or free maternal and child health services increase antenatal care utilisation.54

Problems of access for ordinary Nigerians, including pregnant women, are measured not only in miles or naira, but also in the social and cultural distance between traditional, holistic care systems and formal medicine, which has only widened since the pre-colonial period. In the formal health system, the poor attitude and behaviour of health facility staff influence antenatal care, formal delivery, and postnatal care service use.57 A systematic review60 found a broad range of disrespectful and abusive behaviours towards parturient Nigerian women, ranging from non-dignified care to physical abuse, which sowed distrust and undermined service utilisation. Aversion to such abuse is only one component of the psycho-social barriers to access. In the context of Nigeria's pluralist health system, there is often a strong preference for accessing traditional maternal care, which differentially effects maternal morbidity and mortality, and contributes to health inequities. Rather than in formal facilities, women frequently deliver in herbal or traditional maternity homes, on church premises, or at home due to cultural beliefs, avoidance of the patriarchal (medical) system, affordability and ease of payment, convenience, strong interpersonal relationships with healers, and fear of medical procedures, such as blood collection for investigations and pelvic examinations during delivery.54, 55 There is a strong sense of trust in traditional birth attendants, especially in rural communities, as they are perceived to be more compassionate than formal health workers and provide options such as home delivery, presenting an opportunity to skill up community-based providers who can support normal deliveries and refer pregnant women needing further care.

Section 3: an evolving burden of disease challenges a system focused on curative care

Burden of disease

Demographic context

With an estimated population of 206 million, of which almost 44% is aged under 15 years, Nigeria is both the most populous nation in Africa and one of the youngest.61 Almost 111 million Nigerians are of working age (25–64 years) compared with 95 million of non-working age, and the size of the workforce is projected to grow substantially. Although the UN Population Fund refers to such a situation in which the share of the working-age population is larger than the non-working-age group as a demographic dividend with the potential to drive economic growth into the future,62 no country has tapped into these benefits while faced with unchecked population growth. East Asian countries (eg, Singapore, Indonesia and South Korea) used demographic changes to achieve economic development by incorporating new workers and driving up incomes, productivity, and development indicators.63 However, these countries also simultaneously tackled population growth by lowering fertility rates; between the 1950s and 2010, the total fertility rate in east Asia declined from 5·8 to 2·3.64

Unfortunately, Nigeria still ranks very low on the World Bank's Human Capital Index 2020, as one of only 24 countries out of 174 globally with a score below 0·4.65 Indeed Nigeria's score of 0·36 out of 1 means a Nigerian child born today will only be “36 percent as productive when she grows up as she could be if she enjoyed complete education and full health”.66 Therefore, investments need to be made now to enable the demographic dividend and to avoid population growth outstripping economic growth and pushing more people into poverty.

The country can harness its human resources by ensuring population growth is managed well and a demographic dividend is realised. By investing in reducing unmet need for family planning, closing the gender gap in education through increasing education of the female population, increased opportunities for women's participation in the labour market, and reducing child mortality, Nigeria's fertility rate can decrease towards replacement levels (2·1 children per woman) so that the large proportion of children and youths today at the bottom of the population pyramid become the engine of the economy (Onwujekwe O, unpublished). Such a bulge in the middle of the population structure if realised would mean a high workforce to dependents ratio and can drive growth. This growth is conditional on large investments in good education and health now so that the potential workers of tomorrow are skilled and healthy.

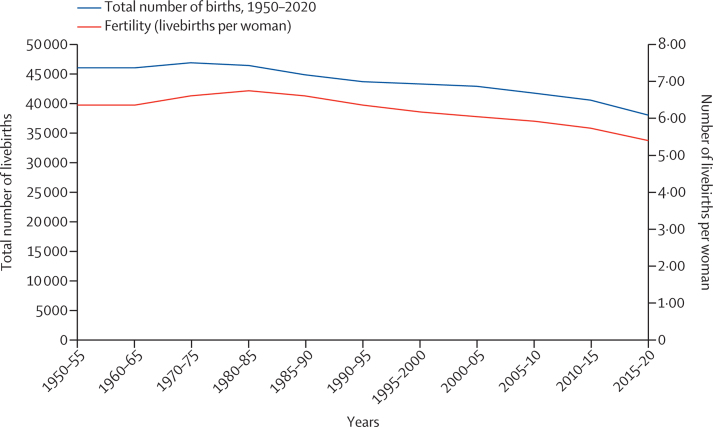

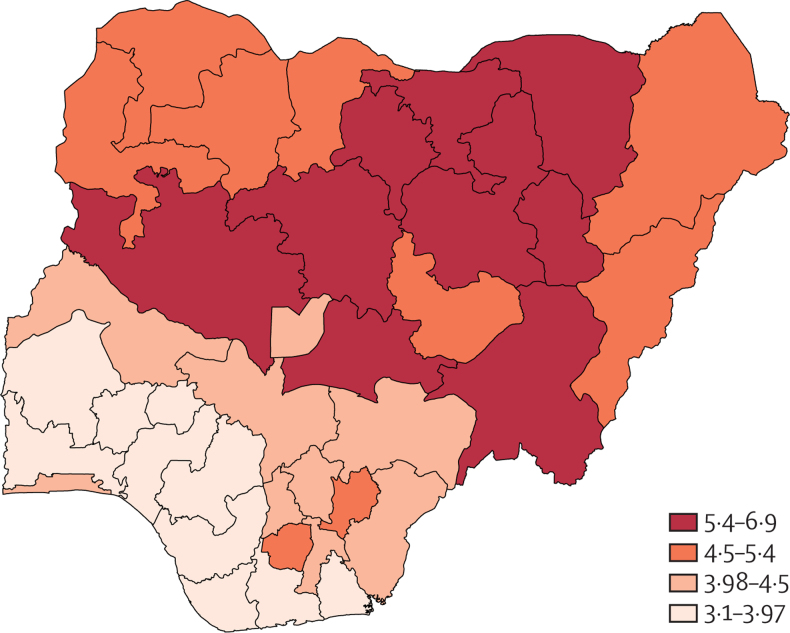

Despite modest decreases in fertility over the past four decades, the fertility rate is high relative to the global average, at around five livebirths per woman (figure 2). The number of births across the country has continued to increase,67 leading to population growth of 2·6% a year, a rate that will lead to a doubling of the population within less than 27 years, placing extensive pressure on communities and social services.61 This figure masks substantial variations in fertility across the country. Various states in the northern geopolitical zone, rural and poorer households, and specific sociocultural and religious groups report higher fertility rates.68 Data from the National HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey reported an average household size ranging from 3·8 in the South-South Region to 5·9 in the North-East Region (figure 3), and lower in urban areas compared with rural regions.

Figure 2.

Fertility rate and total births in Nigeria, 1950–2020

Data are from the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs.61

Figure 3.

Nigeria Average Household Size by State from the National HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey, 2018/19—Sample Size

Faster decreases in fertility driven by family planning and female education, especially in regions and groups with the highest growth rate, will be required for Nigeria to effectively reap its demographic dividend.64, 69 Ensuring access to family planning and contraception is vital to ensuring gender equality and human rights, reducing unplanned pregnancies and achieving broader improvements in health, education, and economic outcomes.70, 71 Yet, unmet need for modern contraception in Nigeria is estimated at over 20%, with only slight decreases in the past two decades.72 Unmet need among married women is estimated to be lower than among unmarried women but still high.73 Meeting the demand for contraception and increased investment in and access to education services is therefore essential, and will require wide-reaching efforts to overcome gender inequities across the population74 and taking into account sociocultural challenges that drive high fertility.

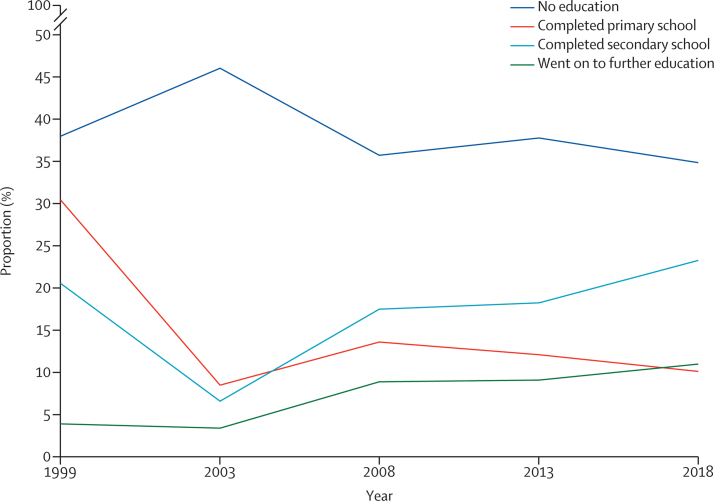

Indeed, the link between the empowerment of women and increased demand for modern contraception has been shown around the world. More broadly, education has been shown to be a key determinant of health seeking behaviour, with the effect particularly pronounced for girls.75 Although the proportion of Nigerian women aged 15–49 years with no education has reduced between 1999 and 2018, it is still relatively high, with 34·9% of women having no formal education as of 2018 (figure 4). The percentage of women with secondary education or higher is highest in the south of Nigeria and lowest in the north (appendix p 32), indicating the long distance to travel in improving female education and in addressing the country's regional disparities.76

Figure 4.

Trends in percent distribution of women aged 15-49 years by highest level of schooling completed, Nigeria DHS 1999–2018

Data are from the National Population Commission (Nigeria]) and ICF 74.

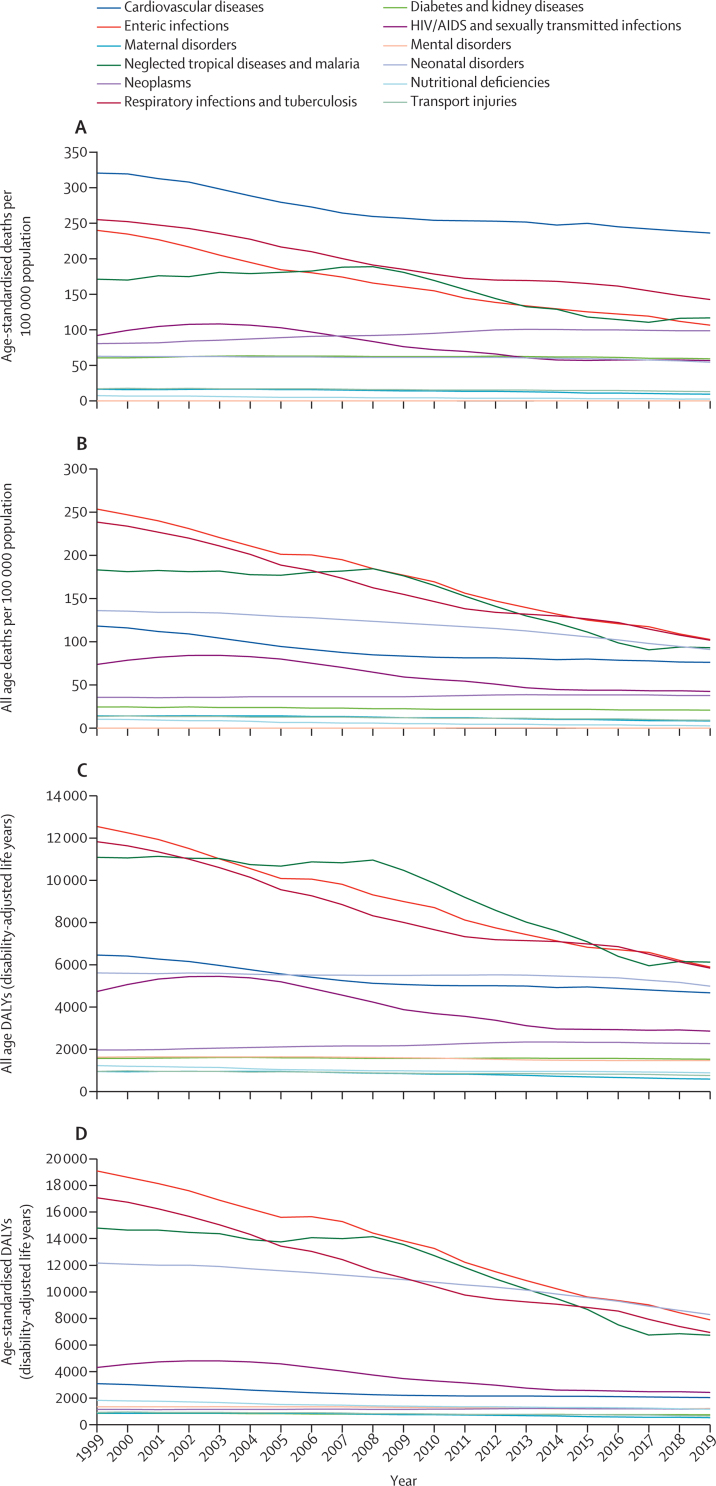

Healthy life expectancy, morbidity, and mortality

Nigeria continues to bear an extremely high burden of death, disease, and disability, even compared with other LMICs. The UN estimates life expectancy at birth in Nigeria to be just over 54 years, the fifth lowest in the world (appendix p 33).61 The burden of death and disability in Nigeria has historically been dominated by communicable, maternal, and neonatal diseases along with nutritional deficiencies, which continue to be the case in 2019, although non-communicable diseases are having an increasing effect on the population over time.67 Much of Nigeria's disease burden is uncertain given the near absence of relevant data; for example, in its latest SCORE assessment, WHO estimates that only 10% of deaths in Nigeria are registered.77, 78 The paucity of data is strongly indicative that decision making is rarely based on appropriate evidence, an enormous challenge that is nonetheless surmountable provided key hurdles are scaled. Panel 4 summarises the data sources, challenges, and suggests areas for improvement.

Panel 4. Data systems and quality in Nigeria.

This Commission has relied heavily on the Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) Injuries and Risk Factors study,79, 80 which provides ongoing estimates of the mortality and morbidity burden attributable to a wide array of conditions and exposure to risk factors in all countries. In addition to the use of GBD results, the Commission undertook bespoke data collection and assessed the quality of existing data to inform future disease burden estimates. Population level data (demographic surveillance sites and census information), national facility-based databases (eg, District Health Information System version 2 [DHIS2]), surveys and surveillance databases eg, Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS), Nigeria HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey, and National Primary Health Care Development Agency immunisation coverage data), and morbidity and mortality records from hospitals across the country were requested.

The process of collating data was not without its challenges, beginning with identifying where the data was situated and requesting permission to access it, due to insufficient institutional memory and frequent leadership changes. Although some organisations were confused as to who the rightful guardian of the data was, others had several custodians with numerous channels to permission, each of whom had to consent for data to be released. Approval processes were therefore complex and slow. Where data existed, as in many health facilities, it was not captured using electronic medical record systems, and was therefore often incomplete and marred with inaccuracies. Furthermore, despite approval from the National Health Research Ethics Committee, each organisation had its own guidelines, which were expected to be fulfilled before data issuance. Reluctance to share data in some institutions was based on concerns about opportunities to publish their own data, cost of extracting data, and apprehensions about privacy and data misuse.

To illustrate the limitations of existing data, we undertook a data quality audit of DHIS2—a key source of input for GBD estimates—in 31 districts across Nigeria selected to achieve geographical representation and data quality spread. We selected districts in the following regions or states: Cross River, South South; Ebonyi, South-East; Oyo, South-West; Kano, North-West; Yobe, North-East; and Nasarawa, North-Central. The results of this audit showed that during the period January to March, 2020, facility-reported data completeness on the DHIS2 platform varied between 58·3% and 71·7%. To illustrate the level of missingness, some public tertiary facilities, responsible for caring for a large proportion of cases out of six facilities audited in each state, did not report any data to the DHIS2 platform. The absence of tertiary hospital data is particularly important for conditions that can only be diagnosed in such centres. In addition to these quality gaps, DHIS2 does not include data from the private sector in most states, where a large proportion of Nigerians access care.

However, some states, such as Lagos, have implemented initiatives to ensure private hospital data are compiled.