Abstract

Objective

This review evaluates the effectiveness of smartphone applications in improving academic performance and clinical practice among healthcare professionals and students.

Methods

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Articles were retrieved from PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane library through a comprehensive search strategy. Studies that included medical, dental, nursing, allied healthcare professional, undergraduates, postgraduates, and interns from the same disciplines who used mobile applications for their academic learning and/or daily clinical practice were considered.

Results

52 studies with a total of 4057 learner participants were included in this review. 33 studies (15 RCTs, 1 cluster RCT, 7 quasi-experimental studies, 9 interventional cohort studies and 1 cross-sectional study) reported that mobile applications were an effective tool that contributed to a significant improvement in the knowledge level of the participants. The pooled effect of 15 studies with 962 participants showed that the knowledge score improved significantly in the group using mobile applications when compared to the group who did not use mobile applications (SMD = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.57 to1.31, P<0.00001). 19 studies (11 RCTs, 3 quasi-experimental studies and 5 interventional cohort studies) reported that mobile applications were effective in significantly improving skills among the participants.

Conclusion

Mobile applications are effective tools in enhancing knowledge and skills. They can be considered as effective adjunct tools in medical education by considering their low expense, high versatility, reduced dependency on regional or site boundaries, online and offline, simulation, and flexible learning features of mobile apps.

Introduction

Applications or apps are software programs designed to run on a computer/tablet/mobile phone to accomplish a particular purpose. Mobile applications play an integral role in medical education, as healthcare professionals (HCPs) and students use these emerging technologies during their training and practice. They have become inevitable in clinical educational settings, particularly as they are accessible for learning anywhere. Many applications are designed to support HCPs with significant tasks such as documentation and time management, health record management and access, consulting and networking, information and reference acquisition, clinical care and monitoring, medical education, training, and clinical decision making [1]. Apps are popular as they have a multimedia approach and include images, videos, texts, and podcasts [2].

The medical education framework encompasses a highly standardized curriculum in a range of preclinical and clinical settings. The designs and specifications of this framework are defined by the Medical Education Board of every country. Competent HCPs are not born; they are educated to combine the art of science with recent concepts of illness, diagnosis, treatment, and empathy. Education in medical institutions endured abrupt disturbances in the face of the 2019 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) [3]. There is ambiguity surrounding how long the condition will continue to exist [4]. Since the pandemic, educational experts are realizing that the implementation and administration of medical curricular modifications will be versatile, building on the current pedagogical framework [5].

In today’s context, as mobile apps offer new learning opportunities, mobile learning is emerging as the newer form of learning and implemented as a result of this pandemic. Most experts suggest that mobile learning initiatives will significantly enhance the learning processes in healthcare. Several randomized trials of mobile learning approaches that aimed at improving knowledge, skills, attitude, and satisfaction have been released. Nevertheless, these results were not carefully checked, and there was no quantification in the effectiveness of mobile learning interventions [6]. Studies suggest that more than 85% of HCPs and medical students use a smartphone, and 30–50% use medical apps for learning and collecting information [7]. The field of medical applications development is very diverse and many applications are being designed to fulfill the needs of medical students and HCPs. As time progressed, smartphones and mobile apps have started to replace conventional knowledge acquisition settings and provide medical students with unparalleled ease of access to medical information and expertise [8]. Despite this acceptance, there is limited research that substantiates the claim that the use of smartphones is effective in enhancing the academic performance of HCPs and/ or students [9].

Mobile apps have a relatively low expense, high versatility, and reduced dependency on regional or site boundaries which encourage stakeholder investments (countries, networks, and universities) and learner demands. This review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of smartphone-based applications in improving academic performance and clinical practice among healthcare professionals and/or students by assessing the impact of the use of smartphone-based interventions and applications in knowledge acquisition and skill levels.

Materials & methods

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines for reporting the findings. The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews with the registration number: CRD42019133670 [10] before conducting the study.

Criteria for inclusion of studies

Type of studies

Quantitative studies such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cluster RCTs (cRCTs), quasi-experimental studies, interventional cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies that assessed the change in knowledge or skill following the use of any mobile application in the study population were included. We excluded studies that assessed the perception of the use of mobile applications, non-English publications, editorials, reviews, conference proceedings, qualitative studies and those on the design and development process.

Type of participants

Medical, dental, nursing, allied HCPs, undergraduates, postgraduates, and internship students from the same disciplines who used mobile applications for academic learning and/or daily clinical practice were included. Participants were not excluded based on their age, gender, experience, and any other socio-demographic characters.

Types of intervention

We included studies that assess the effectiveness of online/offline mobile applications in the acquisition of knowledge and skill development. Studies that include mobile applications related to drug information, guidelines, health parameter calculators, diagnosis, disease, medical notes, case studies, and simulation-aided models to improve knowledge and skills in practice as an intervention were also included. Any intervention using stationary technology, such as desktop computers, e-learning courses attended through internet platforms on mobile phones/tablets/computers, and mobile applications on non-medical topics related to knowledge and skill development among HCPs/ students were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that assessed quantitative outcomes in terms of knowledge or skill level among HCPs/students.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic & other resources searches

We retrieved articles from PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane library databases using a comprehensive search strategy from inception till December 2020. We identified all the possible keywords and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms for the terms “healthcare professionals”, “doctors”, “nurses”, “pharmacists”, “allied healthcare professionals”, “paramedical professionals” and “mobile apps” from the previously published studies and databases. We also used the truncation search method (*) to avoid the possibility of missing studies due to changes in terms in different studies. Further, we searched Google, bibliography of included studies, and relevant reviews published in the same area to look for any other additional studies. The detailed search strategy in different databases is provided in the S1 Appendix.

Selection of studies and data extraction

Two review authors independently determined the eligibility of the studies by examining the title and abstract of the retrieved studies based on the pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, followed by full-text screening. Two review authors independently extracted data from the included studies, using a data extraction form developed using Microsoft Excel. The following information was extracted: characteristics of study (authors name, year of publication, study location), characteristics of the population (type of healthcare professionals/students [year of professional education]), study design, number of participants in study groups at baseline and at the time of completion, characteristics of intervention and/ or control (name and content details of the mobile app, nature of control), outcome measures (scale used), result (knowledge/skill score in mean and standard deviation (SD)/ standardized mean difference (SMD) and SD/median/P value) and limitations of the included studies. All the disagreements during the study selection and data extraction were resolved by consensus or discussion with another researcher.

Assessment of risk of bias in the included studies

The quality of RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool [11] and other study designs were (interventional and observational) assessed using the Modified New castle Ottawa scale [12]. Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool assesses the following criteria of studies: (i) random sequence generation, (ii) allocation concealment, (iii) blinding of participants and personnel, (iv) blinding of outcome assessment, (v) incomplete outcome data, (vi) selective reporting and (vii) any other bias not included in other types into high risk, low risk and unclear risk categories. Modified New castle Ottawa scale assesses the following criteria: (i) representativeness of intervention group (1 point) (ii) selection of comparison group (1point) (iii) comparability of the comparison group (2 points) (iv) study retention (1 point) (v) blinding of assessment (1 point), totaling a maximum of 6 points. Two independent reviewers were involved in the quality assessment and any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Measures of mobile application effectiveness

We separately analyzed the change in knowledge and skill acquisition by using mobile applications among the HCPs and/or students. Our analysis was based on the consideration of continuous outcome variables (change in participants’ knowledge and/or skill score). Studies assessing both skill and knowledge were reported separately in both domains with relevant outcome details.

Data synthesis

The characteristics of the included studies and outcome measures collected were presented in a tabular form and a narrative synthesis was performed. The meta-analysis was performed using the Review Manager version 5.3. [13] Studies reported a single combined score for knowledge and/or skill with continuous data such as mean and SD or those that were calculated from the available data was considered for the meta-analysis. Comparisons of different types of mobile applications are excluded. Studies with multiple arms and multiple applications are considered as separate studies if their knowledge/skill scores were presented separately. The analyzed data is presented as a standardized mean difference along with SD. All the statistical analyses were performed by one author and cross-checked by another author and any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

We used a random-effect model for the data analysis. Further, the sources of heterogeneity were explored through a subgroup analysis according to the study design. Sensitivity analysis was done to ensure the robustness of the study findings by eliminating studies, which had lesser weight and the least number of participants. Funnel plot asymmetry by visual inspection was used for the detection of publication bias, which was further assessed for statistical significance by Egger’s and Begg’s tests. Stata trial version 15 software was used for the detection of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

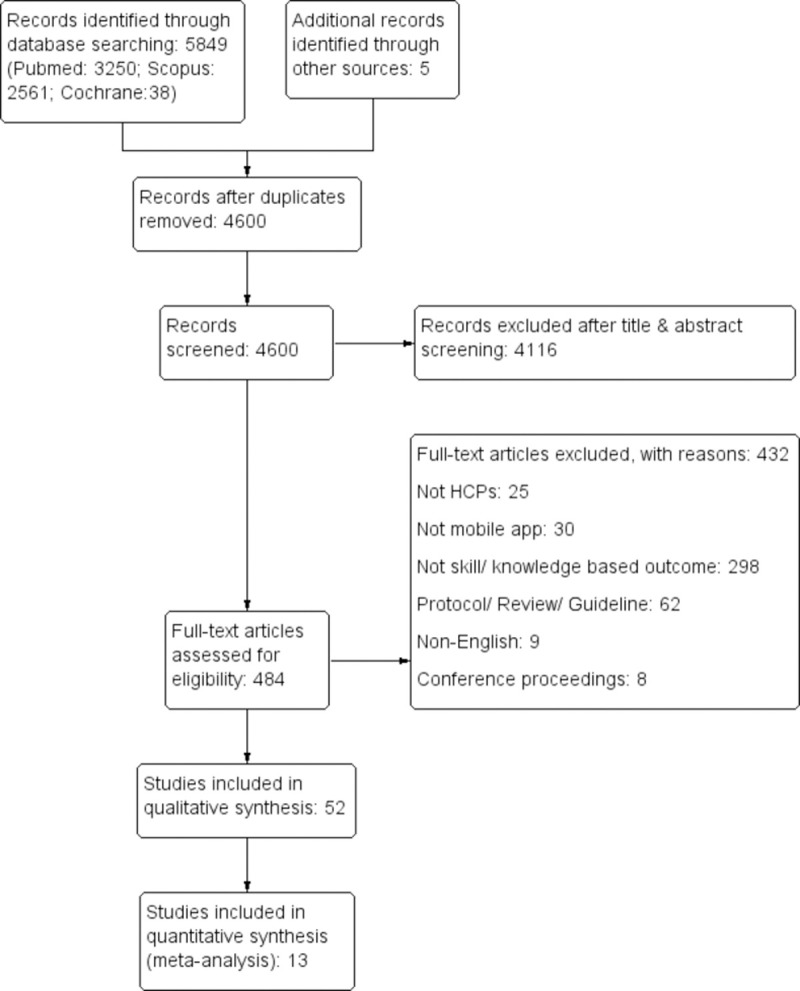

The literature search identified a total of 5849 records out of which 4600 records were screened after the removal of duplication. Finally, 52 articles were included following the exclusion of 4116 records after the initial screening and 432 articles after the full-text screening. The process of identification, screening, eligibility, and synthesis of findings is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig 1).

Fig 1. The PRISMA flow diagram.

Summary & characteristics of studies

Out of 52 included studies, 29 assessed change in the knowledge level [8, 14–41], 10 assessed change in the skill level [42–51], and 13 assessed change in both the knowledge and skill level [9, 52–63]. These studies that provided data from a total of 4057 (sample ranges from 5 to 448) learner participants were included in this review. The included studies consist of 27 RCTs, 1 cluster RCT, 8 quasi-experimental studies, 15 interventional cohort studies, and 1 cross-sectional study, which was published between 2011 and 2020. Major portion of the studies (36/52) were performed in developed countries namely USA (n = 10) [18, 21, 23, 24, 32, 34, 38, 42, 50, 60], UK (n = 7) [37, 43, 44, 47–49, 52], South Korea (n = 5) [53, 58–61], Brazil (n = 4) [15, 25, 40, 45], Germany (n = 3) [17, 19, 63], Spain (n = 3) [29, 55, 56], Turkey (n = 2) [22, 54], Chile (n = 2) [9, 51], while the remaining 10 studies were from France [16], Australia [20], China [27], Iran (n = 4) [14, 28, 30, 41], Rwanda [57], India [33], Taiwan [35], Canada [36], Pakistan [8], Thailand [39], Indonesia [26], Palestine [31] and Finland [46]. The duration of the use of mobile applications ranged from onr time use to a year long usage. The characteristics of the included studies are given in the S2 Appendix. It contains study author, country, year, study design, population, sample size, intervention details, outcome measures, and reported limitations in individual studies.

Quality of included studies

The quality RCTs and cluster RCT were assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool and the results are summarized as the risk of bias graph (S3 Appendix) and summary graph (S4 Appendix). Each category of risk of bias was represented as percentages among the included studies. Interventional and observational studies other than RCTs were assessed using the Modified New castle Ottawa scale. The quality assessment score of included studies using the New castle Ottawa Scale is summarized in the S5 Appendix.

Effect of intervention on knowledge of HCPs

Qualitative analysis

Out of 52 studies, 42 studies reported changes in knowledge level after the use of mobile applications among HCPs/students either in comparison with the control group or comparing the pre and post-test scores of the same group. 33 studies [15 RCTs [9, 14, 15, 17–22, 24–26, 52, 56, 57], 1 cluster RCT [27], 7 quasi-experimental studies [28, 29, 31, 40, 58, 60, 61], 9 interventional cohort studies [33–39, 41, 62] and 1 cross-sectional study [8]] reported that mobile applications were effective tools that led to a significant improvement of knowledge level among the participants. Among that, one RCT conducted by Noll et al., [17] compared the effectiveness of augmented reality mobile application vs. mobile application and concluded that augmented reality mobile application was more effective in increasing the knowledge level than mobile application without augmented reality. 8 studies [5 RCTs [16, 23, 53–55], 1 quasi-experimental study [30], and 2 interventional cohort studies [32, 63]] reported that mobile applications were not effective in improving knowledge among study participants. Among that, one RCT conducted by Kim et al., 2018 [53] compared the effectiveness of interactive mobile application vs non-interactive mobile application and concluded that there is no significant difference in the knowledge level improvement between the two groups. Another quasi-experimental study conducted by Young Yoo et al., [59] reported that mobile applications were effective in improving knowledge in one study condition only (out of the 2 conditions). The overall summary of the effects of mobile applications on the knowledge of HCPs is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Effect of Intervention on knowledge level.

| Study number | Author, year & country | Outcome of interest | Summary statistics (Percentage of mark/ Score by using mobile application (Mean±SD, P Value)) | Sample size (I: Intervention; C: Control) | Duration | Effectiveness of mobile application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bonabi et al, 2019, Iran [14] | Change in knowledge level | Mean knowledge score: Cont: Pre test: 8.17 ± 2.03; Post test: 10.43 ± 1.8 (P<0.001); Int: Pre test: 7.51 ± 1.7; Post test: 10.7 ± 2.1 (P<0.001) | 107 (I: 57; C:50); Final evaluation: 86 (I: 43; C:43) | 4 months | Effective |

| 2 | Velasco et al, 2015, Brazil [15] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean score in the intervention: Pre test: 4.8±3; Post test: 7.5 ± 2 (P = 0.000) Mean score in the control:Pre test: 5.9 ± 3; Post test: 7.5±3 (P = 0.005) |

66 (I: 33; C: 33) | 2 weeks | Effective |

| 3 | Clavier et al, 2019, France [16] | Change in knowledge level |

Post test scores: SCT: Int: 60±9%; Cont: 68±11%; (P = 0.006) MCQs: Int: 18±4; Cont: 16±4; (P = 0.22) |

62 (I: 32; C: 30); Final evaluation: 44 (I:22; C:22) | 3 weeks | Not effective |

| 4 | Noll et al, 2017, Germany [17] | Change in knowledge level |

Average improvement in score (Immediately after learning): Group A: 3.59±1.48; Group B: 3.86±1.51; (P = 0.1) After 14 days follow-up: Average decrease of the number of correct answers as follows; Group A: 0.33±1.62; Group B: 1.14±1.30 |

44 (Group A:22; Group B: 22) | 45 min | Effective |

| 5 | Samra et al, 2016, USA [18] | Change in knowledge level |

Range of score in intervention (Out of 16): Pre test: 0–1; Post test: 0–12 (P = 0.01) Range of score in control (Out of 16): Pre test: 0–2; Post test: 0–4 (P = 0.08); Average improvement in score: Int: 5.4 points (range, 0–12 points); Cont: 0.5 points (range, –1 to +1 points) (P = .0286) |

29 (I: 15; C: 14); Final evaluation 21 (I: 7, C:14) | 8 weeks | Effective |

| 6 | Albrecht V et al, 2013, Germany [19] | Change in knowledge level | Difference in Pre-post score: Int: 4.7±2.9; Cont: 3±1.5 (P = .03). | 10 (I: 6; C: 4) | 105 minutes | Effective |

| 7 | Stirling et al, 2014, Australia [20] | Change in knowledge level |

Pre test score: Int: 9.289 ± 2.265; Cont: 9.727 ±2.565; Post test score: Int: 10.737±1.996; Cont: 10.424 ±2.437; Difference in score: Int: 1.447, 0.384 (P = 0.001); Cont: 2.368, 0.436 (P = 0.12) |

71 (C: 33; I: 38) | One practical session | Effective |

| 8 | Amer et al, 2017, USA [21] | Change in knowledge level | The mean grade on the standardized test: Int: 89.3±6.0%; Cont: 75.6±8.7%; (P < .05) | 100 (C: 50; I: 50) | 3 times visualization | Effective |

| 9 | Kucuk et al, 2016, Turkey [22] | Change in knowledge level | Academic achievement score: Int: 78.14±16.19; cont: 68.34±12.83 (P<0.05) | 70 (I: 34; C: 36) | 5 hours | Effective |

| 10 | Brown et al, 2018, USA [23] | Change in knowledge level | The increment in mean score: Int: 34% to 81%; Cont: 33% to 63%; (P = 0.81) | 67 | 4 days | Not effective |

| 11 | Lacy et al, 2018, USA [24] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean Pre test score: Int: 75%; Cont: 74.7%; Mean post test score: Int: 86.3%; Cont: 77.5% |

36 | 1 hour | Effective |

| 12 | Fernandes Pereira et al, 2016, Brazil [25] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean score (Out of 10): Int: 8.14±1.67; Cont: 5.02±3.21 Error Average: Int: 1.83±0.5; Cont: 4.98±1.0 Average execution time (min): Int: 15.7±21; Cont: 38.9±4.3 |

100 (C: 50; I: 50) | 4 months | Effective |

| 13 | Putri et al, 2019, Indonesia [26] | Change in knowledge level | Mean difference in BLS knowledge: Int: 33.75±12.09; Cont: 25.41±10.93; P = 0.016 | 48 (I: 24; C: 24) | NA | Effective |

| 14 | Martínez et al, 2017, Chile* [9] | Change in knowledge level |

Increase in score: App group: 16.2 ± 8.3 (P < 0.001); Control: 10.6 ± 11.7 (P < 0.001) Difference in score between the groups: 3.5 (P = 0.22). |

80 (I: 40; C: 40) | 4 weeks | Effective |

| 15 | Naveed et al, 2018, England [52] | Change in knowledge level | Average MCQ Score (Percentage): Int: 62.95±5.37; Cont: 56.73±5.18; P = 0.0285 | 20 (C: 10, I: 10); Final evaluation: 15 (C: 7, I: 8) | Int: 1 hr; Cont: 2 hrs | Effective |

| 16 | Kim et al, 2018, South Korea [53] | Change in knowledge level |

Improvement in mean knowledge (Out of 23): Int: 21.24±1.74 to 22.18±0.76; Cont: 20.84±1.35 to 21.25±1.41 Mean Difference in Pre-post Knowledge: Int: 0.94±1.74; Cont: 0.41±1.04; P = 0.133 |

72 (C: 36; I: 36) Final evaluation: 66 (C: 32, I: 34) | 1 week | Not effective |

| 17 | Kang et al, 2020, South Korea [61] | Change in knowledge level | Mean Difference in Pre-post Knowledge: Cont: 0.02 ± 0.13; Exp 1: 0.15 ± 0.14; Exp 2: 0.11 ± 0.15; P = 0.004 | 86 (Exp 1: 26; Exp 2: 32; Cont: 28) | 2 weeks | Effective |

| 18 | Bayram et al, 2019, Turkey [54] | Change in knowledge level |

Median First Knowledge test scores: Int: 18 (9–22); Cont: 17 (12−23); P = 0.441 Median Last Knowledge test scores:Int:19 (13−23); Cont: 19 (8–23); P = 0.568 |

118 (C: 59; I:59) | 1 week | Not effective |

| 19 | Fernández-Lao et al, 2016, Spain [55] | Change in knowledge level | Knowledge test (out of 10 points): Int:7.21 ± 1.988; Cont: 8.09 ± .921; P = 0.089 | 49 (I: 25; C: 24) | 2 weeks | Not effective |

| 20 | Lozano-Lozano et al, 2020, Spain [56] | Change in knowledge level | Pass percentage (MCQ): Int: 86% (43/50); Cont: 27% (15/55); P<0.001 | 110 (C: 55, I: 55) Final Evaluation: 105 (C: 55, I: 50) | 2 weeks | Effective |

| 21 | Bunogerane et al, 2017, Rwanda [57] | Change in knowledge level |

Percentage change in knowledge: Tendon repair theory: Cont:13.0% (P = 0.535); Int: 39.1% (P = 0.056) Tendon repair technique: Cont:19.0% (P = 0.165); Int: 38.1% (P = 0.0254) |

27 (C: 13; I: 14) | Till post-test completion | Effective |

| 22 | Wang et al, 2017, China [27] | Change in knowledge level |

Base line: Int: 19.43±2.48; Cont: 19.04± 2.66; Post test (2nd week): Int:24.18 ± 3.51; Cont: 20.02 ±2.53; Post test (3rd month): Int: 23.61 ± 3.37; Cont:19.54 ± 2.67; |

115 (I: 61; C: 54) | 3 months | Effective |

| 23 | Ziabari et al, 2019, Iran [28] | Change in knowledge level |

Increment inmean awareness score: Int: 11.44 ± 2.37 to 14.88 ± 1.97, P < 0.0001; Cont: 11.38 ± 3.22 to 12.54 ± 3.04; P<0.0001; Mean difference in BLS awareness score: Int: 3.44±1.48; Cont:1.16±1.51; P<0.0001 |

100 (I: 50; C: 50) | 3 months | Effective |

| 24 | Briz-Ponce et al, 2016, Spain [29] | Change in knowledge level |

Pre–post test scores in intervention: Pre test: 2.2000±1.3732; Post test: 3.6000±1.12122 (P = 0.031) Pre–post test scores in control: Pre test: 2.6667±1.54303; Post test: 2.4000±1.40408 (P = 0.157) |

30 (I: 15; C: 15) | 3 Sessions | Effective |

| 25 | Golshah et al, 2020, Iran [30] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean grade point: Post test: Int: 15.57 ± 0.91; Cont: 15.39 ± 1.09; P = 0.503 |

53 (I: 27; C: 26) | 2 weeks | Not effective |

| 26 | Salameh et al, 2020, Palestine [31] | Change in knowledge level | Mean difference in pre-post test scores: Int: 3.86±1.65; Cont: 1.5±2.21; P<0.000 | 104 (I: 52; C: 52) | NA | Effective |

| 27 | Kang et al, 2018, South Korea# [58] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean HTN knowledge: Pre test:Int: 89.4±5.9; Cont: 87.4±7.5; Post test:Int: 93.7±4.4; Cont: 87.4±4.7; P = 0.001 Mean DM knowledge: Pre test:Int: 86.5±8.3; Cont: 84.9±6.8; Post test:Int: 91.0±5.7; Cont: 86.0±8.7; P = 0.009 |

92 [I: 49 (HTN: 21; DM: 28); C: 43 (HTN: 20; DM: 23)] | 1 week | Effective |

| 28 | Young Yoo et al, 2015, South Korea [59] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean Lung test: Pre test:Int: 6.7±1.0; Cont: 6.6±2.1 (P = 0.666);Post test:Int:7.4±0.8; Cont: 5.8±1.6 (P = 0.031) Mean Heart test: Pre test: Int:6.4 ± 1.2; Cont:5.7 ± 1.2 (P = 0.161);Post test: Int: 8.3±1.2; Cont: 8.7 ± 0.9 (P = 0.489) |

22 (11 each cross over) | 4 weeks | Effective in one condition (Out of 2) |

| 29 | Kim et al, 2017, South Korea [60] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean Knowledge: Pre test: Int: 8.69±1.62; Cont: 9.10±1.57 (P = 0.266); Post test: Int: 11.80±1.32; Cont: 11.84±1.48 (P = 0.899) Mean Difference in knowledge: Int: 3.11±1.78; Cont: 2.74±1.86 (P = 0.379) |

80 (I: 40; C: 40) Final evaluation: 73 (I: 35; C:38) | 1 month | Effective |

| 30 | Chung et al, 2018, USA [32] | Change in knowledge level |

Difference in mean pre-post score: Int: 2.4% [–3.1 to 8]; Cont: 4.8% [0.3–9.4]; P>0.05 Post score: Int: 73.8% [69.2–78.4]; Cont: 74.1% [70.3–78.0]; P>0.05 |

37 (I: 18; C: 19) | 4 weeks | Not effective |

| 31 | Shore et al, 2018, USA [62] | Change in knowledge level | Median score of Pre test: 87 (IQR, 81 to 94); Median score of Post test: 100 (IQR, 94 to 100). | 53 (single group) | 3 weeks | Effective |

| 32 | Deshpande et al, 2017, India [33] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean score in SCT: Pre test: 41.5±1.7; Post test: 63±2.4 (P < 0.005). |

92 (single group) | 1 year | Effective |

| 33 | Man et al, 2014, USA [34] | Change in knowledge level |

Mean total score (%): Percentage of correct answers increased after 12 weeks when compared to baseline (P = 0.205). Mean confidence level: Managing outpatient adults with major depression: Baseline: 4.214; After 12 Weeks: 5.364 (P = 0.048); Starting an antidepressant for newly diagnosed major depression: Baseline: 4.286; After 12 Weeks: 5.636 (P = 0.018); Choosing an antidepressant based on patient factors: Baseline: 3.642; After 12 Weeks: 5.273 (P = 0.010) |

N = 14 (Single group) | 12 weeks | Effective |

| 34 | Liu et al, 2018, Taiwan [35] | Change in knowledge level |

Average pre-course score: Overall: 27.50±15.83; Non-dermatology trainees: 15.38 ±8.03; Dermatology trainees: 39.62 ± 11.81. Average post course score: Overall: 91.44 ± 5.92; Non-dermatology trainees: 90.77 ± 5.98; Dermatology trainees: 92.12 ± 6.02 |

26 (Group 1:13; Group 2: 13) | 3 weeks | Effective |

| 35 | Fralick et al, 2017, Canada [36] | Change in knowledge level |

Improvement in knowledge score: Int: 6.2±2.1 vs 8.1±2.2 (P = 0.0001); Cont: 7.1±1.7 vs 7.5±2.0 (P = 0.23) Unadjusted linear regression analysis: P = 0.006 [95% CI: 0.46, 2.48]) Adjusted multivariable linear regression analysis: P = 0.04 [95% CI: 0.10, 2.1]) |

62 (I: 32; C: 30); Follow up: 53 (I: 27; C: 26) | 4 weeks | Effective |

| 36 | Weldon et al, 2019, UK [37] | Change in knowledge level |

Percentage of correct answers: Pre test: Q1: 40%; Q2: 100%; Q3: 60%; Q4: 20%; Q5: 20%; Q6: 20% Post test: Q1: 80%; Q2: 100%; Q3: 80%; Q4: 60%; Q5: 20%; Q6: 80% |

5 (Single group) | Till completion of post test | Effective |

| 37 | Smeds et al, 2016, USA [38] | Change in knowledge level | NBME score: Int: 77.5%; Cont: 68.8% (P< 0.01); USMLE scores: Int: 225.4; Cont: 209.8; (P < 0.001); Cumulative GPA: Int: 3.3; Cont: 2.9; (P < 0.001); Mean MCAT scores: Int: 9.6; Cont: 8.9; (P < 0.01). | 288 (I: 152; C: 136) | 1 year | Effective |

| 38 | Ebner et al, 2019, Germany [63] | Change in knowledge level | Mean Score of MCQs: Int: 30.2; Cont: 36.8 (P = 0.13) | 66 (I: 33; C: 33) | 1 week | Not effective |

| 39 | Hirunyanitiwattana et al, 2020, Thailand [39] | Change in knowledge level |

General asthma knowledge scores: Asthma knowledge in both groups improved significantly between pre & post test (WAAP: P = 0.135; ACA: P = 0.002) Asthma action plan knowledge scores: No statistical difference in score between, or within each group |

44 (I: 25; C: 19) | 3 hours | Effective |

| 40 | Baccin et al, 2020, Brazil [40] | Change in knowledge level | Mean grade: Pre test: 4.77±1.63; Post test: 8.49±1.27 (P<0.0001). | 161 Final evaluation: 150 | 7 weeks | Effective |

| 41 | Ameri et al, 2020, Iran [41] | Change in knowledge level | Difference in mean pre-post test score: Cont: 0.06 (7.69 to 7.75; P = 0.84); Group 1: 1.88 (7.71 to 9.59; P<0.0001); Group 2: 7.6 (7.5 to 15.1; P<0.0001) | 316 (C: 106 Group 1: 105 Group 2: 105) | 2 months | Effective |

| 42 | Hisam et al, 2019, Pakistan [8] | Change in knowledge level |

Score in the last professional examination: Int: 69±7%; Cont: 67±9%. Average usage of application VS academic performance (P<0.01) |

448 (I: 323; C: 125) | NA | Effective |

ACA: Asthma Care Application; AR: Augmented Reality; BLS: Basic Life Support; BSE: Breast Self Examination; CI: Confidence Interval; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; GPA: Grade Point Average; Hr: Hour; HTN: Hypertension; IQR: Inter Quartile Range; MCAT: Medical College Admissions Test; MCQ: Multiple Choice Questionnaire; MD: Mean Deviation; NA: Not Available; NBME: National Board of Medical Examiners; RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial; SCT: Script Concordance Test; SD: Standard Deviation; SEM: Standard Error of the Mean; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America; USMLE: United States Medical Licensing Examination; WAAP: Written Asthma Action Plan

* Indicates that the study reported final score of EUNACOM (theoretical practical exam of general medicine) as combined knowledge and skill score. So the same result is repeated in skill domain also.

# indicates that the study considered as 2 studies in meta analysis, as it is evaluating 2 apps

Quantitative analysis

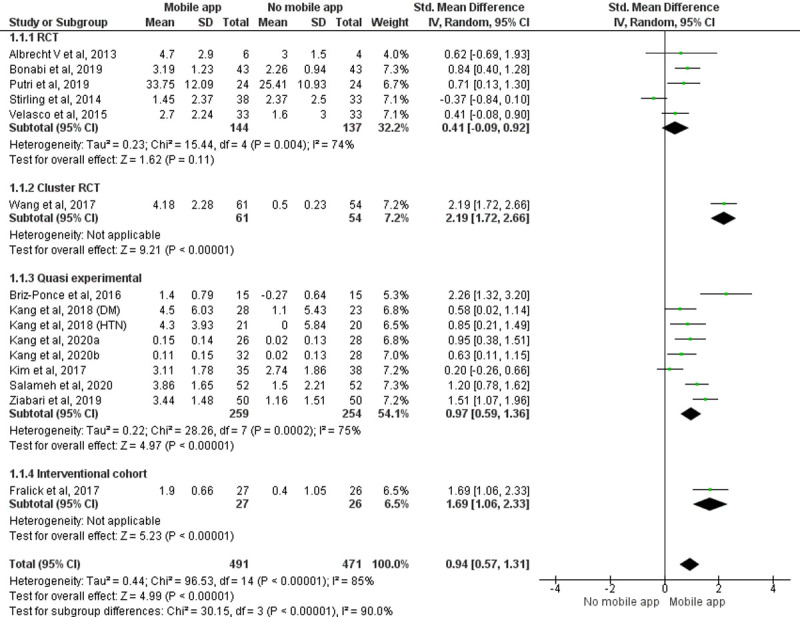

Pooled effect of 15 [14, 15, 19, 20, 26–29, 31, 36, 58, 60, 61] studies with 962 participants showed that the knowledge score improved significantly in the group using the mobile application when compared to the group that does not use mobile application (SMD = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.57 to1.31, P<0.00001) (Study by Kang 2018 [58] is considered as two studies in the meta-analysis as it analyzes the effectiveness of two different applications and reported the outcomes separately. The study by Kang 2020 [61] is considered as two studies in the meta-analysis as it has three groups and analyzed outcomes separately). The random effect model was considered because of the significant statistical heterogeneity among studies (Fig 2). A subgroup analysis was performed because of the heterogeneity in the included study designs. The pooled effect of individual study designs (Cluster RCT, quasi experimental studies and interventional cohort study) showed that participants using mobile applications had better knowledge enhancement scores compared to the group that did not use mobile applications among the study participants (Cluster RCT: SMD = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.72 to2.66, P<0.00001; quasi-experimental studies: SMD = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.59 to 1.36, P<0.00001; interventional cohort study: SMD = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.06 to 2.33, P <0.00001) giving total weightage of 67.8%.

Fig 2. Forest plot: Effect of intervention on knowledge of HCPs.

Effect of intervention on skills of HCPs

Qualitative analysis

Out of 52 studies, 23 studies reported changes in skill level after the use of mobile applications among healthcare professionals/students either in comparison with the control group or comparing the pre and post-test scores of the same group. 19 studies [11 RCTs [9, 43–45, 47, 48, 52, 53, 55–57], 3 quasi-experimental studies [58, 60, 61] and 5 interventional cohort studies [49–51, 62, 63]] reported that mobile applications were effective tool and significantly improved skill levels among participants. Among that, one RCT conducted by Kim et al., in 2018 [53] compared the effectiveness of an interactive mobile application vs a non-interactive mobile application and concluded that interactive mobile application was more effective in improving skill than the non-interactive mobile application. Three studies [2 RCTs [46, 54] and 1 quasi-experimental study [59]] reported that mobile applications were not effective in improving skill among study participants. One RCT conducted by Nadir et al., in 2019 [42] reported that a mobile application was effective in improving skill in one study condition only (out of two conditions). The overall summary of the effects of mobile applications on the knowledge of HCPs is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Effect of Intervention on skill level.

| Study number | Author, year & country | Outcome of interest | Summary statistics (Percentage of mark/ Score by using mobile application (Mean±SD, P Value)) | Sample size (I: Intervention; C: Control) | Duration | Effectiveness of mobile application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nadir et al, 2019, USA [42] | Change in skill level |

Mean percentages of completed checklist items: Int: 56.1±10.3; Cont: 49.4±7.4 for shortness of breath (P = 0.001); Int: 58±8.1; Cont: 49.8±7.0 for syncope (P<0.001) Mean GRS score for Syncope: Int:3.14±0.89; Cont: 2.6±0.97; P = 0.003 Mean GRS score for shortness of breath: Int:2.90±0.97; Cont: 2.81±0.80; P = 0.43 |

58 (C:29; I: 29) | 23 minutes | Effective in one condition (Out of 2) |

| 2 | Mamtora et al, 2018, UK [43] | Change in skill level |

Accurate description score (Out of 60): Dry AMD: Int: 47(78%); Cont: 28(47%) P < 0.05; CRVO: Int: 31(52%); Cont: 15(25%) P < 0.05; Papilloedema: Int: 28(47%); Cont: 29(48%) p = 0.52; Optic atrophy: Int: 50(83%); Cont: 34(57%); P = 0.08; PDR: Int: 43(72%); Cont: 32(53%); p = < 0.05 Accurate clinical diagnosis score (Out of 20): AMD: Int: 15(75%); Cont: 6(30%) P < 0.05; CRVO: Int: 8(40%); Cont: 6(30%); P = 0.48; Papilloedema: Int: 6(30%); Cont: 6(30%); P = 0.78; Optic atrophy: Int: 4(20%); Cont: 4(20%) P = 0.66; PDR: Int: 14(70%); Cont: 8(40%) P = 0.10 |

20 (C: 10; I: 10) | 15 min | Effective |

| 3 | Haubruck et al, 2018, UK [44] | Change in skill level |

Operation performance by OSATS (Points): Int: 38.0 [I50 = 7.0]; Cont: 30.5 [I50 = 8.0]; (P<0.001); Economy of time and motion: Int: 4.0 [I50 = 1.0]; Cont: 3.0 [I50 = 1.0]; (P = 0.004); Less helping need: Int: 4.0 [I50 = 1.0]; Cont: 2.0 [I50 = 1.0]; (P<0.001); Confident in handling of instruments: Int: 3.0 [I50 = 2.0]; Cont: 3.0 [I50 = 2.0] (P<0.001); Digital exploration of the pleural cavity: Int: 4.0 [I50 = 2.0]; Cont: 2.0 [I50 = 2.0](P<0.001); Median time of performing a CTI: Int: 4:15; Cont: 4:17 min. |

95 (I: 49; C: 46) | 120 min | Effective |

| 4 | Oliveira et al, 2019, Brazil [45] | Change in skill level | Significant differences from the specialists’ reference standards: Int: Conditions 4 and 10 (P<0.001); Cont: Conditions 1, 4,6, 7, 8, and 10 (P<0.05) | 20 (C: 10; I: 10) | 1 month | Effective |

| 5 | Martínez et al, 2017, Chile* [9] | Change in skill level |

Increase in score: Int: 16.2 ± 8.3 points (P < 0.001); Cont: 10.6 ± 11.7 points (P < 0.001) Difference in score between the groups: 3.5points (P = 0.22). |

80 (I: 40; C: 40) | 4 weeks | Effective |

| 6 | Naveed et al, 2018, England [52] | Change in skill level | Average OSATS Score (Max score: 5): Int: 3.53±0.39; Cont: 2.58±0.71; P = 0.0139 | 20 (C: 10; I: 10); Final evaluation (C: 7; I: 8) | Int: 1 hour; Cont: 2 hours | Effective |

| 7 | Kim et al, 2018, South Korea [53] | Change in skill level |

Improvement in nursing skill performance (Out of 378): Int: 205.35 ± 24.01 to 363.62 ± 9.07; Cont: 202.94 ± 22.95 to 328.22 ± 27.76 Mean Difference in Pre-post Skills: Int: 158.26±25.61; Cont: 125.28±33.502; P<0.001 |

72 (C: 36; I: 36); Final evaluation: 66 (C: 32, I: 34) | 1 week | Effective |

| 8 | Kang et al, 2020, South Korea [61] | Change in skill level |

Mean Difference in Pre-post Skills: Cont: 0.52 ± 0.56; Exp 1: 0.62 ± 0.73; Exp 2: 0.95 ± 0.46; P = 0.014 |

86 (Exp 1: 26; Exp 2: 32; Cont: 28) | 2 weeks | Effective |

| 9 | Bayram et al, 2019, Turkey [54] | Change in skill level |

Median Skill score: Pre test:Int: 53 (40–57); Cont: 53 (37–57); P = 0.997 Post test:Int: 55 (46–57); Cont: 54 (46–57); P = 0.017 Median OSCE time (Seconds): Pre test: Int: 330 (162–360); Cont: 340 (228–360); P = 0.022 Post test:Int: 260 (180–360); Cont: 260 (190–360); P = 0.723 |

118 (C: 59; I:59) | 1 week | Not effective |

| 10 | Fernández-Lao et al, 2016, Spain [55] | Change in skill level |

Global OSCE Scores: Ultrasound skills: Int:12.000 ± 2.572; Cont:9.000 ± 2.943; P = 0.000 Palpation skills: 12.038 ± 3.155; Cont:9.833 ± 3.963; P = 0.034 |

49 (I: 25; C: 24) | 2 weeks | Effective |

| 11 | Lozano-Lozano et al, 2020, Spain [56] | Change in skill level |

OSCE exam score: Int:7.3 ± 1.5; Cont: NA; P<0.001 |

110 (C: 55; I: 55); Final Evaluation: 105 (C: 55; I: 50) | 2 weeks | Effective |

| 12 | Strandell-Laine et al, 2018, Finland [46] | Change in skill level |

Mean Overall improvement in competence score: Int: 10.11±2.22; Cont: 11.67±2.30 (P = 0.57) Mean Improvement in self-efficacy: Int: 1.77±0.17; Cont: 1.51± 0.20 (P = 0.37) |

102 (I = 52; C = 50) | Three periods of 5 weeks | Not effective |

| 13 | Bartlett et al, 2017, UK [47] | Change in skill level |

Mean baseline score to post intervention score: Group 1: 28.7 (62.3%) to 32.7 (71.1%); P = 0.003 Group 2: 27.0 (58.7%) to 36.1 (78.5%); P = 0.001 Group 3: 27.6 (59.8%) to 34.9 (75.7%); P = 0.001 Mean score change from baseline (95% CI): Group 1: 4.0 (1.8–6.2); Group 2:9.1 (4.7–13.5); Group 3: 7.3 (4.3–10.4) |

27 (Group 1: 9; Group 2: 9; Group 3: 9) | 1 hour | Effective |

| 14 | Bunogerane et al, 2017, Rwanda [57] | Change in skill level |

Difference in cognitive skills (percentage change in pre test & post test): Int: 38.6% (P<0.001); Cont: 15.9% (P = 0.304) Overall simulation test score: Int: 22.43 (89.71%); Cont: 15.85 (63.4%); P <0.001 |

27 (C: 13; I: 14) | Till post-test completion | Effective |

| 15 | Low et al, 2011, UK [48] | Change in skill level | Overall cardiac arrest simulation test score Median (IQR): Int: 84.5(75.5–92.5); Cont: 72(62–87); P = 0.02 | 31 (I: 16; C: 15) | Till completion of test | Effective |

| 16 | Miriam McMullan, 2018, UK [49] | Change in skill level |

Drug Calculation Ability (Mean±SD): Pre: 47.6±23.4; Post: 56.7±24.7; P = 0.004 Drug Calculation Self-Efficacy (Mean±SD): Pre: 20.4±18.0; Post: 49.6±19.9; P<0.001 |

60 (Paramedics: 41; ODP: 19) | 8 weeks | Effective |

| 17 | Kang et al, 2018, South Korea [58] | Change in skill level |

Mean HTN self-efficacy Pre test: Int:72.2±9.6;Cont:68.1±13.6; Post test: Int:78.0±10.3;Cont:66.4±13.6; P = 0 .002 Mean DM self-efficacy Pre test: Int:67.8±9.9;Cont: 62.2±14.1; Post test: Int:72.0±12.2;Cont: 65.8±12.6; P = 0.043 |

92 [I: 49 (HTN: 21; DM: 28); C: 43 (HTN: 20; DM: 23)] | 1 week | Effective |

| 18 | Young Yoo et al, 2015, South Korea [59] | Change in skill level |

Clinical assessment skill for lung practice:Int:29.0 ± 1.1; Cont: 28.4 ± 0.8 (P = 0.258) Clinical assessment skill for Heart practice: Int: 37.0 ± 2.4; Cont: 38.3 ± 1.3 (P = 0.258) |

22 (11 each cross over) | 4 weeks | Not effective |

| 19 | Kim et al, 2017, South Korea [60] | Change in skill level | Difference in the mean scores for skills: Int: 11.97 ± 5.07; Cont: 6.71 ± 4.34 (P<0.001) | 80 (I: 40; C: 40); Final evaluation: 73 (I: 35; C:38) | 1 month | Effective |

| 20 | Shore et al, 2018, USA [62] | Change in skill level | Median simulation test score: 89 (IQR, 81 to 92) | 53 (single group) | 3 weeks | Effective |

| 21 | Meyer et al, 2018, USA [50] | Change in skill level |

Mean accuracy in testing/ diagnostic decisions: Int: 82.6%; Cont: 70.2%; P<0.001 Mean confidence in testing/diagnostic decisions (out of 10): Int: 7.5; Cont: 6.3; P<0.001 |

46 | 30 to 60 minutes | Effective |

| 22 | Quezada et al, 2019, Chile [51] | Change in skill level |

Improvement in GRS (5–25) score: Int: 15(6–17) to 23(20–25); P<0.05; Cont: 15(10–19) to 24(22–5); P<0.05 Improvement in SRS (4–20) score: Int: 12(11–15) to 18(15–20); P<0.05; Cont: 12(8–15) to 19(16–20); P<0.05 Change in Operative time (min): Int: 39(10.47) to 22(3.37); P<0.05; Cont: 42(12.58) to 22(3.35); P <0.05 |

55 (C: 25; I: 30) | 72 hours for single video | Effective |

| 23 | Ebner et al, 2019, Germany [63] | Change in skill level |

Longitudinal kidney measurements (mm) Right kidney (Median[IQR]): Int: 105.3(86.1 to 127.1); Cont: 92(50.4 to 112.2); P<0.001 Left kidney (Median[IQR]):Int: 100.3(81.7 to 118.6); Cont: 85.3(48.3 to 113.4); P<0.001 Median Measuring time (in seconds): Int: 351 (155–563); Cont: 302 (103–527) P = 0.26 |

66 (I: 33; C: 33) | 1 week | Effective |

AMD: Age-related Macular Degeneration; CRVO: Central retinal vein occlusion; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; GRS: Global rating scale; HTN: Hypertension; ODP: Operating Department Practice; OSATS: Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills; OSCE: Objective structured clinical evaluation; PDR: Pre-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; SD: Standard Deviation; SRS: Specific rating scale; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America.

* Indicates that the study reported final score of EUNACOM (theoretical practical exam of general medicine) as combined knowledge and skill score. So the same result is repeated in skill domain also

Quantitative analysis

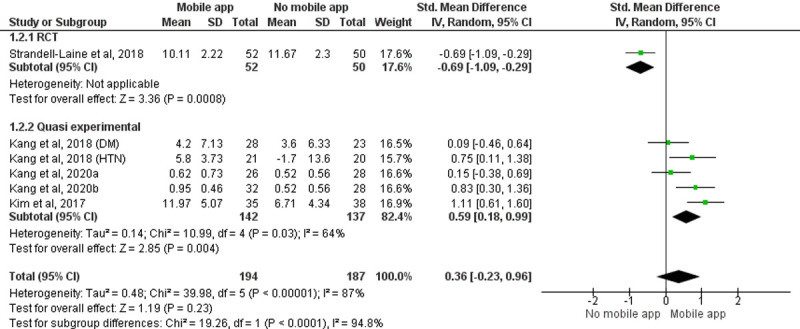

A meta-analysis of six [46, 58, 60, 61] studies with 381 participants studies showed no significant change in skill level among the group using the mobile applications and the group that did not use mobile applications (SMD = 0.36, 95% CI = -0.23 to 0.96, P = 0.23). Included study designs for data synthesis were RCT (n = 1) [46] and quasi-experimental studies (n = 5) [58, 60] (Study by Kang 2018 [58] is considered as two studies in the meta-analysis as it analyzed the effectiveness of two different applications and reported outcomes separately. The study by Kang 2020 [61] is considered as two studies in the meta-analysis as it has three groups and analyzed outcomes separately). The random-effect model was considered because of the significant statistical heterogeneity among studies. A subgroup analysis was performed based on study designs. The pooled effect of quasi-experimental studies showed that the group using the mobile application was better at skill enhancement than the group that did not use mobile application among the study participants (SMD = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.18 to 0.99, P = 0.04) giving a total weightage of 82.4% (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Forest plot: Effect of intervention on the skill of HCPs.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed by removing four studies from the knowledge assessment and one study from the skill assessment that has less weightage, which also supported the previous findings. The result of sensitivity analysis is depicted in S6 Appendix and S7 Appendix.

Publication bias

An obvious asymmetry was observed by the visual inspection of the funnel plot (S8 Appendix), which was not statistically confirmed by Egger’s (P = 0.5) and Begg’s test (P = 0.49). Hence there is no publication bias among the included studies in the meta-analysis.

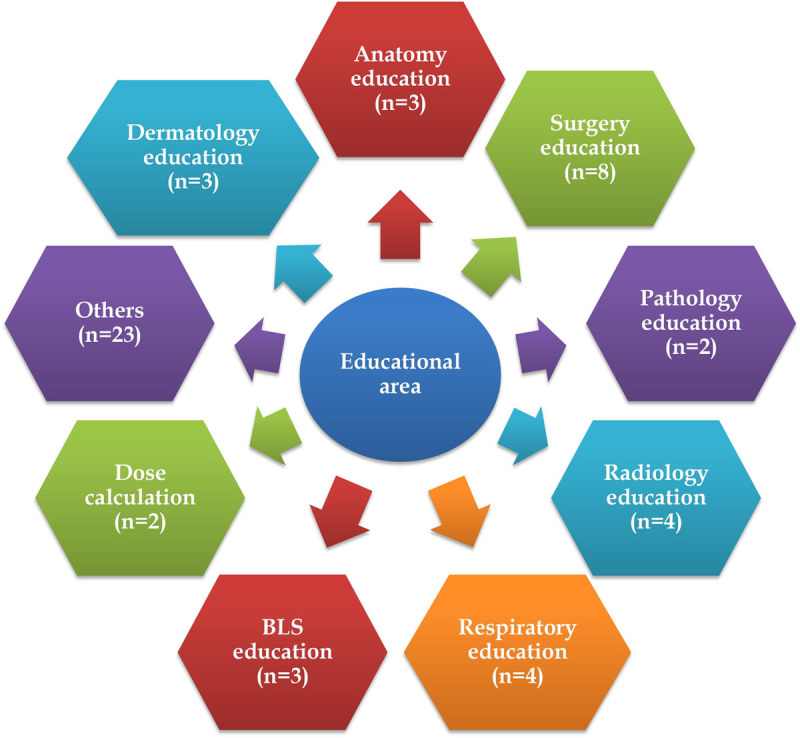

Educational area of mobile applications

The majority of researchers used mobile applications for education on anatomy, surgery, respiratory conditions, dermatology, basic life support (BLS), pathology, dose calculation, and radiology. The characteristic details of the intervention and educational area details are depicted in S2 Appendix and Fig 4.

Fig 4. Educational area of mobile applications.

Network connectivity and mobile apps

Most of the applications that cater to medical education were web-based mobile applications that require an internet connection for access. There was no significant change in the enhancement of knowledge and/or skill among participants using online and offline versions of mobile apps (S9 Appendix). Developing mobile applications which can be accessed without internet connectivity will increase the acceptability and use of mobile apps among healthcare professionals and/or students living in low to middle-income countries and rural areas.

Mobile application operating system

Android and iPhone operating systems (iOS) were used for mobile applications. Both operating system-based applications were effective in enhancing knowledge or skill. There was no significant change in the enhancement of knowledge or skill among participants who used android or iOS mobile apps (S10 Appendix). Developing mobile applications which can be operated through android will increase the acceptability and use of mobile apps among healthcare professionals and/or students living in low to middle-income countries.

Discussion

This study attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of mobile applications in enhancing knowledge and/or skill among HCPs and/or students. The findings from the study support the claim that mobile applications are an effective tool. Medical, paramedical, and allied healthcare professionals were the target population for evaluating the effectiveness of mobile apps in enhancing knowledge and skills. The educational topic, duration of intervention, nature of control/comparison group, and features of mobile apps were different in different studies. Even if the population and mobile apps have their differences, every study compared the change in knowledge and/or skill quantitatively with or without a comparison group. Variations were present in providing the type of educational material to the control/comparison group in different studies. Studies compared the effectiveness of mobile app learning vs traditional teaching or teaching using audio-video slides, simulator training, hardcopy learning materials and e-learning through computer platforms. All the studies compared the change in knowledge and/or skill level by using a mobile application with any of the regular teaching methods, which did not affect the quality of study results. The meta-analysis of the change in the skill of the included studies was not statistically significant. This is possibly due to the limited number of studies in the meta-analysis. Studies that reported skill as a single comparable score were only considered for the meta-analysis. The majority of studies reported multiple component scores in evaluating the skill of healthcare professionals. The systematic review findings supported the use of mobile applications in the enhancement of skill.

Different studies used different mobile applications with different educational topics. The “Touch surgery” application was used in five studies [21, 44, 47, 57, 62] but the educational topic was different. The choice of topics in a mobile app may differ due to the variety of study population, area of interest/expertise of study coordinators and/or study participants and required facilities (e. g.: simulation) in the institution.

Studies among various healthcare professionals reported mixed results regarding the usefulness of the e-learning, mobile learning and technology-enhanced learning. A Cochrane systematic review conducted by Vaona et al in 2018 compared traditional learning with e-learning and reported that e-learning may make little or no difference in health professionals’ behaviours, skills or knowledge [64]. A study conducted by Subhash et al, 2015 among medical students reported that smartphones can be effectively used for learning [65]. A study conducted by Snashall et al, 2016 among medical students reported that medical apps can be used as an adjunct in medical education, though the evidence remains limited [2]. A qualitative systematic review by the Digital Health Education Collaboration conducted by Lall et al, 2019 on the implementation of mobile learning for medical and nursing education reported that mobile learning can potentially play a substantial role in learning [66]. A study conducted by Dickinson et al, 2020 on the educational applications for surgery residents reported that technology-enhanced learning has become prevalent in surgical education and future studies are needed to assess the efficacy of educational apps for surgical education [67]. By considering all the other published studies to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review that has attempted to quantitatively analyze the change in knowledge and/or skills by using any mobile application.

Additionally, this is the first systematic review assessing the effectiveness of online vs offline and android vs iOS based mobile applications in enhancing knowledge and/or skill quantitatively. Even if more studies focused on online applications, offline applications also were equally effective. Either android or iOS based mobile applications were used in different studies. Offline mobile applications, which can be accessed through android and iOS will increase the wide acceptability of mobile apps and reduce the economic burden. Moreover, they help tackle problems due to poor internet connectivity. It is the latest growing trend and developers of mobile apps should take tremendous interest in creating these applications [68].

No restrictions were imposed in the publication period during the literature search. But the included studies were published between 2011 and 2020. During the first decade of the 2000s, m-learning had grown in different forms and directions [69]. This may be the reason for the publication period ranging from 2011 to 2020. Among the 52 included studies around 36 studies are from developed nations. The remaining studies are only developing countries. This may be because the concept of m–learning originated in Europe and this encouraged researchers and educators to reconsider their view on mobile technology as a pedagogical tool [70]. Other possible reasons may include lack of resources, fear of adopting mobile technology, lack of skills of instructors, interruption in power supply and internet connectivity, affordability issues, low bandwidth, and trust deficit. This could impact the global representativeness of the review findings. Therefore, future research should address the effectiveness of mobile applications in learning in diverse populations from other countries.

Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool was used to assess the quality of included RCTs. The quality of the majority of included studies in all sub-domains was high to moderate except for the blinding of participants and personnel, which showed a high risk of bias based on the Cochrane tool. It is not possible to blind the participants in the study population as it provides a mobile application for education to the intervention group. Hence the overall risk of bias in the included studies can be considered as low to moderate. Modified New castle Ottawa scale was used to assess the risk of bias in the included studies other than RCTs. All studies have a comparison group scored 4 or more. Hence these can be considered as moderate to high-quality studies. Single group studies can be considered as low-quality studies based on lesser scores in Modified New castle Ottawa scale scoring. The findings from this review can be considered before developing any mobile application in medical education as the results are interpreted from high-quality studies.

However, this study has some limitations. In this study, the search was conducted in three databases only and this may lead to the missing of studies. We tried to avoid the biases due to the missing of studies by selecting large databases such as PubMed, Cochrane library and Scopus and also by developing a comprehensive search strategy by collecting maximum keywords from the published studies and MeSH term search. According to Cochrane guidelines, a minimum of two large electronic databases should be searched. We have chosen 3 major scientific databases for searching studies. Additionally, we have searched the bibliography of included studies, related reviews, and free search in Google Scholar. This resulted in the identification of five more studies. Hence the chance of missing studies is limited in our review. Secondly, we have excluded studies published in other languages except for English, conference proceedings and grey literature. This may lead to the missing of studies published in non-English languages. However, excluding studies from conference proceedings and grey literature sources may increase the strength of study findings by avoiding irrelevant and incomplete data. Heterogeneity in the assessment of knowledge and/or skill of the study population was another limitation. We have included studies that reported quantitative measurement of knowledge and/or skill score to avoid biases due to various measurement approaches. The meta-analysis was performed for studies provided mean and SD or could be calculated from the reported measures only.

Future directions

Smartphone learning encourages conversation, communication, and cooperation, as well as increased participation. Millennial learners prefer participant-centered, active, and self-directed. Mobile applications based learning can be integrated into medical education to evaluate its performance. Learning materials should be available in a digital format to be feasible to fuel smartphone learning and online education. The importance of education and training using mobile applications is enhanced in the current COVID-19 scenario. A faculty-guided strategy to select appropriate and cost-effective medical education applications can be used. Universities or healthcare organizations should adopt policies for faculty, staff and/or students regarding the use of mobile applications for educational purposes. Multicenter randomized controlled trials with a longer duration have to be conducted to assess the effectiveness and the retention of knowledge and/or skills of mobile applications in medical education among HCPs and/or students. Necessary measures should be employed to avoid dropout, cross-communication between participants and software compatibility issues among trial participants. Other validated practical methods should be employed to assess the knowledge and/or skill validated questionnaires.

Conclusion

Mobile applications are effective tools in enhancing knowledge and skills among healthcare professionals. Online/offline and android/iOS based applications were equally effective in enhancing knowledge. The prevailing pandemic situation demands medical education to increasingly utilize the opportunities of e-learning instead of conventional teaching. Mobile applications can be considered as an effective adjunct tool in medical education by considering the low expense, high versatility, reduced dependency on regional or site boundaries, online, offline, simulation and learning wherever features of mobile apps.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(PNG)

(PNG)

(DOCX)

(PNG)

(PNG)

(PNG)

(JPG)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Department of Pharmacy Practice for all the support and library facilities for the best possible completion of this study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Ventola CL. Mobile Devices and Apps for Health Care Professionals: Uses and Benefits. P T. 2014. May;39(5):356–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snashall E, Hindocha S. The Use of Smartphone Applications in Medical Education. Open Medicine Journal [Internet]. 2016. Dec 27 [cited 2021 Jan 22];3(1). Available from: https://benthamopen.com/FULLTEXT/MEDJ-3-322 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wayne DB, Green M, Neilson EG. Medical education in the time of COVID-19. Sci Adv [Internet]. 2020. Jul 29 [cited 2021 Jan 22];6(31). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7399480/ doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc7110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19 | Medical Education and Training | JAMA | JAMA Network [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 22]. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2764138

- 5.Medical education during COVID-19: Lessons from a pandemic | British Columbia Medical Journal [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 9]. Available from: https://bcmj.org/special-feature-covid-19/medical-education-during-covid-19-lessons-pandemic

- 6.Free C, Phillips G, Watson L, Galli L, Felix L, Edwards P, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2013;10(1):e1001363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozdalga E, Ozdalga A, Ahuja N. The smartphone in medicine: a review of current and potential use among physicians and students. J Med Internet Res 2012;14(5):e128. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.A H, Mu S, Mn K, A H, Mb A, T S. Usage and types of mobile medical applications amongst medical students of Pakistan and its association with their academic performance. Pak J Med Sci 2019;35(2):432–6. doi: 10.12669/pjms.35.2.672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martínez F, Tobar C, Taramasco C. Implementation of a Smartphone application in medical education: a randomised trial (iSTART). BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2017. Sep 18 [cited 2021 Jan 22];17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5604333/ doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1010-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandran Viji, Thunga Girish, Pai Girish, Khan Sohil, Devi Elsa, Poojari Pooja, et al. Smart phone apps for health professional education. PROSPERO 2019. CRD42019133670 Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019133670. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Repr. with corr. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. 649 p. (Cochrane book series). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad Med 2015;90(8):1067–76. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.RevMan [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 22]. Available from: /online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman

- 14.Bonabi M, Mohebbi SZ, Martinez-Mier EA, Thyvalikakath TP, Khami MR. Effectiveness of smart phone application use as continuing medical education method in pediatric oral health care: a randomized trial. BMC Medical Education 2019;19(1):431. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1852-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velasco HF, Cabral CZ, Pinheiro PP, Azambuja R de CS, Vitola LS, Costa MR da, et al. Use of digital media for the education of health professionals in the treatment of childhood asthma. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2015;91(2):183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2014.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clavier T, Ramen J, Dureuil B, Veber B, Hanouz J-L, Dupont H, et al. Use of the Smartphone App WhatsApp as an E-Learning Method for Medical Residents: Multicenter Controlled Randomized Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7(4):e12825. doi: 10.2196/12825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noll C, von Jan U, Raap U, Albrecht U-V. Mobile Augmented Reality as a Feature for Self-Oriented, Blended Learning in Medicine: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5(9):e139. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.7943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samra S, Wu A, Redleaf M. Interactive iPhone/iPad App for Increased Tympanic Membrane Familiarity. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2016;125(12):997–1000. doi: 10.1177/0003489416669952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albrecht U-V, Folta-Schoofs K, Behrends M, von Jan U. Effects of mobile augmented reality learning compared to textbook learning on medical students: randomized controlled pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2013;15(8):e182. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stirling A, Birt J. An enriched multimedia eBook application to facilitate learning of anatomy. Anat Sci Educ 2014;7(1):19–27. doi: 10.1002/ase.1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amer KM, Mur T, Amer K, Ilyas AM. A Mobile-Based Surgical Simulation Application: A Comparative Analysis of Efficacy Using a Carpal Tunnel Release Module. J Hand Surg Am 2017;42(5):389.e1–389.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Küçük S, Kapakin S, Göktaş Y. Learning anatomy via mobile augmented reality: Effects on achievement and cognitive load. Anat Sci Educ 2016;9(5):411–21. doi: 10.1002/ase.1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown A, Ajufo E, Cone C, Quirk M. LectureKeepr: A novel approach to studying in the adaptive curriculum. Med Teach 2018;40(8):834–7. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1484895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacy FA, Coman GC, Holliday AC, Kolodney MS. Assessment of Smartphone Application for Teaching Intuitive Visual Diagnosis of Melanoma. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154(6):730–1. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandes Pereira FG, Afio Caetano J, Marques Frota N, Gomes da Silva M. Use of digital applications in the medicament calculation education for nursing. Invest Educ Enferm 2016;34(2):297–304. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v34n2a09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Putri NO, Barlianto W, Setyoadi. The Influence of Learning with Mobile Application in Improving Knowledge about Basic Life Support. IJPHRD 2019;10(8):1010–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang F, Xiao LD, Wang K, Li M, Yang Y. Evaluation of a WeChat-based dementia-specific training program for nurses in primary care settings: A randomized controlled trial. Appl Nurs Res 2017;38:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zia Ziabari SM, Monsef Kasmaei V, Khoshgozaran L, Shakiba M. Continuous Education of Basic Life Support (BLS) through Social Media; a Quasi-Experimental Study. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2019;7(1):e4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briz-Ponce L, Juanes-Méndez JA, García-Peñalvo FJ, Pereira A. Effects of Mobile Learning in Medical Education: A Counterfactual Evaluation. J Med Syst 2016;40(6):136. doi: 10.1007/s10916-016-0487-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golshah A, Dehdar F, Imani MM, Nikkerdar N. Efficacy of smartphone-based Mobile learning versus lecture-based learning for instruction of Cephalometric landmark identification. BMC Med Educ 2020;20(1):287. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02201-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salameh B, Ewais A, Salameh O. Integrating M-Learning in Teaching ECG Reading and Arrhythmia Management for Undergraduate Nursing Students. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM) 2020;14(01):82–95. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Using an Audience Response System Smartphone App to Improve Resident Education in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.—Abstract—Europe PMC [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 22]. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/pmc/pmc5912270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Deshpande S, Chahande J, Rathi A. Mobile learning app: A novel method to teach clinical decision making in prosthodontics. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2017;30(1):31–4. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.210514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Man C, Nguyen C, Lin S. Effectiveness of a smartphone app for guiding antidepressant drug selection. Fam Med 2014;46(8):626–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu R-F, Wang F-Y, Yen H, Sun P-L, Yang C-H. A new mobile learning module using smartphone wallpapers in identification of medical fungi for medical students and residents. Int J Dermatol 2018;57(4):458–62. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fralick M, Haj R, Hirpara D, Wong K, Muller M, Matukas L, et al. Can a smartphone app improve medical trainees’ knowledge of antibiotics? Int J Med Educ 2017;8:416–20. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5a11.8422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weldon M, Poyade M, Martin JL, Sharp L, Martin D. Using Interactive 3D Visualisations in Neuropsychiatric Education. In: Rea PM, editor. Biomedical Visualisation: Volume 2 [Internet].Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. [cited 2021 Jan 22]. p. 17–27. (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology). Available from: 10.1007/978-3-030-14227-8_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smeds MR, Thrush CR, Mizell JS, Berry KS, Bentley FR. Mobile spaced education for surgery rotation improves National Board of Medical Examiners scores. J Surg Res 2016;201(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirunyanitiwattana T, Pirompanich P, Boonya-anuchit P, Maitree T, Poachanukoon O. Effectiveness of Asthma Knowledge in Nurses using Asthma Care Application Compared with Written Asthma Action Plan. JOURNAL OF THE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION OF THAILAND 2020;103(4):16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baccin CRA, Dal Sasso GTM, Paixão CA, de Sousa PAF. Mobile Application as a Learning Aid for Nurses and Nursing Students to Identify and Care for Stroke Patients: Pretest and Posttest Results. Comput Inform Nurs 2020;38(7):358–66. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ameri A, Khajouei R, Ameri A, Jahani Y. LabSafety, the Pharmaceutical Laboratory Android Application, for Improving the Knowledge of Pharmacy Students. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education 2020;48(1):44–53. doi: 10.1002/bmb.21311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.JMIR Medical Education—Impact of an Electronic App on Resident Responses to Simulated In-Flight Medical Emergencies: Randomized Controlled Trial [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 22]. Available from: https://mededu.jmir.org/2019/1/e10955/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Mamtora S, Sandinha MT, Ajith A, Song A, Steel DHW. Smart phone ophthalmoscopy: a potential replacement for the direct ophthalmoscope. Eye (Lond) 2018;32(11):1766–71. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0177-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haubruck P, Nickel F, Ober J, Walker T, Bergdolt C, Friedrich M, et al. Evaluation of App-Based Serious Gaming as a Training Method in Teaching Chest Tube Insertion to Medical Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res 2018;20(5):e195. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliveira MLB de, Verner FS, Kamburoğlu K, Silva JNN, Junqueira RB. Effectiveness of Using a Mobile App to Improve Dental Students’ Ability to Identify Endodontic Complications from Periapical Radiographs. Journal of Dental Education 2019;83(9):1092–9. doi: 10.21815/JDE.019.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strandell-Laine C, Saarikoski M, Löyttyniemi E, Meretoja R, Salminen L, Leino-Kilpi H. Effectiveness of mobile cooperation intervention on students’ clinical learning outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2018;74(6):1319–31. doi: 10.1111/jan.13542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bartlett RD, Radenkovic D, Mitrasinovic S, Cole A, Pavkovic I, Denn PCP, et al. A pilot study to assess the utility of a freely downloadable mobile application simulator for undergraduate clinical skills training: a single-blinded, randomised controlled trial. BMC Medical Education 2017;17(1):247. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1085-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Low D, Clark N, Soar J, Padkin A, Stoneham A, Perkins GD, et al. A randomised control trial to determine if use of the iResus© application on a smart phone improves the performance of an advanced life support provider in a simulated medical emergency. Anaesthesia 2011;66(4):255–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06649.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McMullan M. Evaluation of a medication calculation mobile app using a cognitive load instructional design. Int J Med Inform 2018;118:72–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyer AND, Thompson PJ, Khanna A, Desai S, Mathews BK, Yousef E, et al. Evaluating a mobile application for improving clinical laboratory test ordering and diagnosis. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018;25(7):841–7. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quezada J, Achurra P, Jarry C, Asbun D, Tejos R, Inzunza M, et al. Minimally invasive tele-mentoring opportunity-the mito project. Surg Endosc 2020;34(6):2585–92. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-07024-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naveed H, Hudson R, Khatib M, Bello F. Basic skin surgery interactive simulation: system description and randomised educational trial. Advances in Simulation 2018;3(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s41077-018-0074-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim H, Suh EE. The Effects of an Interactive Nursing Skills Mobile Application on Nursing Students’ Knowledge, Self-efficacy, and Skills Performance: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2018;12(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bayram SB, Caliskan N. Effect of a game-based virtual reality phone application on tracheostomy care education for nursing students: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ Today 2019;79:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernández-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Galiano-Castillo N, Caro-Morán E, Díaz-Rodríguez L, Arroyo-Morales M. The effectiveness of a mobile application for the development of palpation and ultrasound imaging skills to supplement the traditional learning of physiotherapy students. BMC Med Educ 2016;16(1):274. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0775-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lozano-Lozano M, Galiano-Castillo N, Fernández-Lao C, Postigo-Martin P, Álvarez-Salvago F, Arroyo-Morales M, et al. The Ecofisio Mobile App for Assessment and Diagnosis Using Ultrasound Imaging for Undergraduate Health Science Students: Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(3):e16258. doi: 10.2196/16258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bunogerane GJ, Taylor K, Lin Y, Costas-Chavarri A. Using Touch Surgery to Improve Surgical Education in Low- and Middle-Income Settings: A Randomized Control Trial. J Surg Educ 2018;75(1):231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Development and Evaluation of “Chronic Illness Care Smartphone Apps” on Nursing Students’ Knowledge, Self-efficacy, and Learning Experience.—Abstract—Europe PMC [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 22]. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/29901475 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Yoo I-Y, Lee Y-M. The effects of mobile applications in cardiopulmonary assessment education. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35(2):e19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim S-J, Shin H, Lee J, Kang S, Bartlett R. A smartphone application to educate undergraduate nursing students about providing care for infant airway obstruction. Nurse Educ Today 2017;48:145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kang SR, Shin H, Lee J, Kim S-J. Effects of smartphone application education combined with hands-on practice in breast self-examination on junior nursing students in South Korea. Jpn J Nurs Sci 2020;17(3):e12318. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shore BJ, Miller PE, Noonan KJ, Bae DS. Predictability of Clinical Knowledge Through Mobile App-based Simulation for the Treatment of Pediatric Septic Arthritis: A Pilot Study. J Pediatr Orthop 2018;38(9):e541–5. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ebner F, De Gregorio A, Schochter F, Bekes I, Janni W, Lato K. Effect of an Augmented Reality Ultrasound Trainer App on the Motor Skills Needed for a Kidney Ultrasound: Prospective Trial. JMIR Serious Games 2019;7(2):e12713. doi: 10.2196/12713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaona A, Banzi R, Kwag KH, Rigon G, Cereda D, Pecoraro V, et al. E-learning for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;1:CD011736. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011736.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Subhash TS, Bapurao TS. Perception of medical students for utility of mobile technology use in medical education. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health 2015;5(4):7. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lall P, Rees R, Law GCY, Dunleavy G, Cotič Ž, Car J. Influences on the Implementation of Mobile Learning for Medical and Nursing Education: Qualitative Systematic Review by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res 2019;21(2):e12895. doi: 10.2196/12895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dickinson KJ, Bass BL. A Systematic Review of Educational Mobile-Applications (Apps) for Surgery Residents: Simulation and Beyond. J Surg Educ 2020;77(5):1244–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shah R. Commentary. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(2):JC9. doi: 10.7326/ACPJC-2018-169-2-009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pedro LFMG, Barbosa CMM de O, Santos CM das N. A critical review of mobile learning integration in formal educational contexts. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2018;15(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosman P. M-LEARNING—AS A PARADIGM OF NEW FORMS IN EDUCATION. 2008;7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(PNG)

(PNG)

(DOCX)

(PNG)

(PNG)

(PNG)

(JPG)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.