Abstract

The existing zoonotic coronaviruses (CoVs) and viral genetic variants are important microbiological pathogens that cause severe disease in humans and animals. Currently, no effective broad-spectrum antiviral drugs against existing and emerging CoVs are available. The CoV main protease (Mpro) plays an essential role in viral replication, making it an ideal target for drug development. However, the structure of the Deltacoronavirus Mpro is still unavailable. Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) is a novel CoV that belongs to the genus Deltacoronavirus and causes atrophic enteritis, severe diarrhea, vomiting and dehydration in pigs. Here, we determined the structure of PDCoV Mpro complexed with a Michael acceptor inhibitor. Structural comparison showed that the backbone of PDCoV Mpro is similar to those of alpha-, beta- and gamma-CoV Mpros. The substrate-binding pocket of Mpro is well conserved in the subfamily Coronavirinae. In addition, we also observed that Mpros from the same genus adopted a similar conformation. Furthermore, the structure of PDCoV Mpro in complex with a Michael acceptor inhibitor revealed the mechanism of its inhibition of PDCoV Mpro. Our results provide a basis for the development of broad-spectrum antivirals against PDCoV and other CoVs.

Keywords: coronaviruses, porcine deltacoronavirus, main protease, broad-spectrum antivirals

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are round or oval enveloped viruses with a positive-sense RNA genome [1]. CoVs are among the most dangerous microbiological pathogens that infect mammals, such as humans, mice, cats, and pigs, as well as birds, such as sparrows, and they are responsible for a large number of gastric, enteric and respiratory syndromes [2,3,4,5,6]. In 2003, an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) led to an international epidemic, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) was demonstrated to be the etiological agent [7,8,9,10]. In 2012, a novel CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), was reported in Saudi Arabia [11]. MERS-CoV infection can cause patients to develop acute renal failure. In late December 2019, a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified in Wuhan, Hubei Province. This infectious pneumonia has spread worldwide, and as of January 2022, more than 318 million people have been infected, and 5.5 million have died from the disease [12]. The ceaseless emergence of new pathogenic CoVs indicates that CoVs remain an enormous threat to public health security. However, at present, no effective broad-spectrum antiviral drugs against existing and emerging CoVs are available.

As demonstrated, the existing zoonotic viruses and viral genetic variants are widely known to be a potential threat to public health. It has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 as well as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are likely to have originated from animal reservoirs and crossed species barriers to infect humans [13,14]. In addition, a high percentage of sequence variations among CoV strains and recombination during coinfections have been indicated. Therefore, it is necessary to develop broad-spectrum antivirals against existing and emerging CoVs. CoV main proteases (Mpros), also called 3C-like proteases, which play a vital role in the proteolytic pathway in viral replication, are known to be among the most attractive and ideal targets for antiviral drug design [15]. The RNA genome of CoVs encodes two replicase polyproteins (pp1a and pp1ab) and other structural proteins. The polyproteins are cotranslationally cleaved into 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1 to nsp16) and assemble into membrane-anchored replication machinery for transcription or replication [16]. Mpros are responsible for cleavage at no fewer than 11 sites, indicating their main role in virus replication and pathogenesis.

Mpros are defined as serine proteases, which have the closest relatives with 3C-like proteinases of potyviruses [17]. Mpros always function as dimers and employ conserved cysteine and histidine residues at their catalytic site as charge-relay systems [18,19]. At present, CoVs are generally divided into four genera according to their genome sequences, as follows: Alphacoronavirus (including human coronavirus NL63 [HCoV-NL63], human coronavirus 229E [HCoV-229E], porcine epidemic diarrhea virus [PEDV], transmissible gastroenteritis virus [TGEV] and feline infectious peritonitis virus [FIPV]), Betacoronavirus (including SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, human coronavirus HKU1 [HCoV-HKU1] and MERS-CoV), Gammacoronavirus (infectious bronchitis virus [IBV]), and the newly discovered Deltacoronavirus genus. Several three-dimensional crystal structures of Mpros have been determined for Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus and Gammacoronavirus [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. However, little is known about the Mpro of Deltacoronavirus, posing a blind spot for broad-spectrum drug design against CoV Mpros. Currently, human CoVs have been identified in the genera Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus. There are not yet reports of CoVs from the genera Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus infecting humans. However, it has been demonstrated that porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) can infect cells of human origin by interacting with host aminopeptidase N (APN) via its spike (S) protein, and studies have identified children in Haiti who were positive for PDCoV, which poses a considerable concern to human health with adaptive changes [30,31]. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the properties of the newly identified Deltacoronavirus Mpro and its relationship with other CoV Mpros to direct rational drug design.

PDCoV is a member of the subfamily Coronaviridae, genus Deltacoronavirus, which was first discovered in 2012 in Hong Kong and named porcine coronavirus HKU15 [6]. Later, the virus spread nationwide and was gradually detected in the US, Korea and various provinces of China [32,33,34,35]. At present, the reasons for the sudden emergence and origin of PDCoV in pigs remain unclear. Similar to PEDV infections, PDCoV infections cause atrophic enteritis, severe diarrhea, vomiting and dehydration in nursing piglets [36], and infected piglets have a high mortality rate [37]. PEDV and PDCoV can infect pigs alone or jointly; these features result in CoV emergence and reemergence in pigs, causing many pig deaths and a dramatic negative economic impact on the animal husbandry industry, leading to major economic losses [32,38]. In this study, we determined the crystal structure of PDCoV Mpro from Deltacoronavirus complexed with a peptidomimetic inhibitor with a Michael acceptor, which is the substituent group on the activated α, β unsaturated ester and can undergo Michael addition reaction with nucleophile from the enzyme. The complex structure provided insight into the detailed structural features of PDCoV Mpro and revealed the mechanism underlying its inactivation by the Michael acceptor. In addition, we identified a drug target conserved among all alpha-, beta-, gamma- and delta-CoVs. We then obtained two modified inhibitors with improved inhibition activity, and propose that peptidomimetic inhibitors carrying a Michael acceptor warhead are effective against the Mpros of all CoVs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene Expression and Protein Purification

The PDCoV Mpro coding sequence was cloned into the BamHI and XhoI restriction sites of the pET-28b_SUMO vector and then transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3). The fusion protein SUMO-PDCoV Mpro was purified by Ni-affinity chromatography (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and then cleaved with ULP protease. Mpro was further purified using anion exchange chromatography (HiTrap Q, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) with a linear gradient from 2.5 to 500 mM NaCl (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0) and size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl.

2.2. Crystallization, Data Collection, Structure Determination and Refinement

Crystals of the complex were obtained by cocrystallization following the incubation of 1 mg mL−1 PDCoV Mpro and 10 mM N3 in the buffer of 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl at 4 °C at a molar ratio of 1:5 for 12 h. The complex was concentrated to 9 mg mL−1 and then crystallized by the microbatch-under-oil method at 291 K. The successful crystal growth conditions were 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.1) and 4% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 6000. Crystals were cryoprotected with 20% glycerol, 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.1) and 4% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 6000 and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) beamline BL19U1 at 100 K using an ADSC Q315r detector with a wavelength of 0.97923 Å. The crystal belonged to space group P61 with unit cell dimensions a = b = 122.3 Å and c = 289.8 Å. Diffraction data were processed with HKL3000 (version 721.3, HKL Research, Inc., Charlottesville, VA, USA) (44). The complex structure was solved by molecular replacement using the structure of PEDV Mpro (PDB ID 5GWZ) [27] as a search model through the PHASER [39] program from the CCP4 package [40]. Model building and refinement were performed using PHENIX (version 1.14) [41] and COOT (version 0.8.9) [42]. The Rwork and Rfree of the final model were 19.21% and 24.14%, respectively.

2.3. Enzyme Activity and Inhibition Assays

Enzymatic assays were carried out as previously reported [15,28,29]. A fluorogenic substrate of PDCoV Mpro, MCA-AVLQ↓SGFR-Lys(Dnp)-Lys-NH2 (>95% purity, GL Biochem Shanghai Ltd., Shanghai, China), was used to assess enzyme activity by measuring fluorescence intensity with excitation and emission wavelengths of 320 nm and 405 nm, respectively. The assay was performed at 30 °C, and the buffer used consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3) and 1 mM EDTA. The Km and kcat of PDCoV Mpro and Ki and k3 of N3 were determined according to the methods used in our previous work [15,29]. The values of Ki and k3 were obtained following the addition of PDCoV Mpro. The enzyme and substrate concentration were set at 2 µM and 50 µM, respectively. The inhibitor concentration varied among seven different concentrations (6–24 µM). Data were analyzed with the program GraphPad Prism (version 5.0, GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). The enzymatic assay used to test M14 and M25 was similar to that used to test N3.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Structure

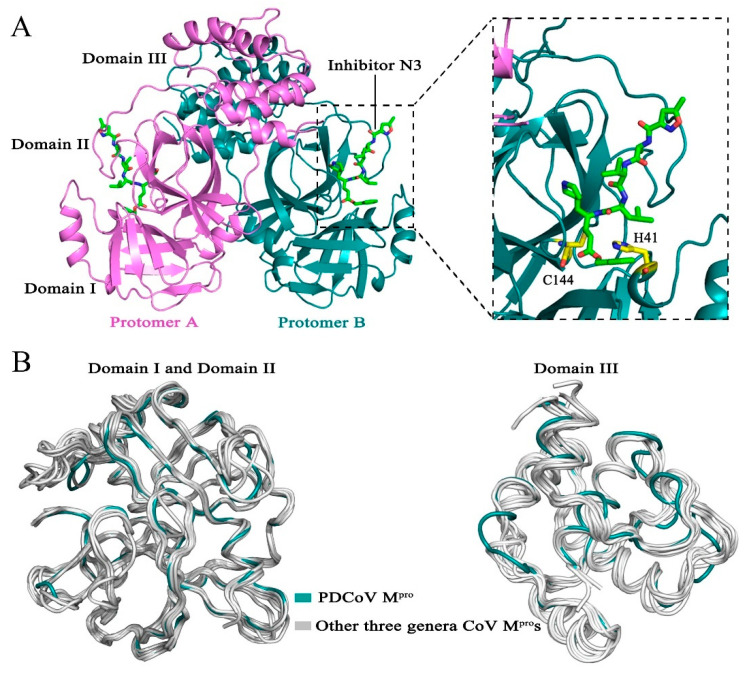

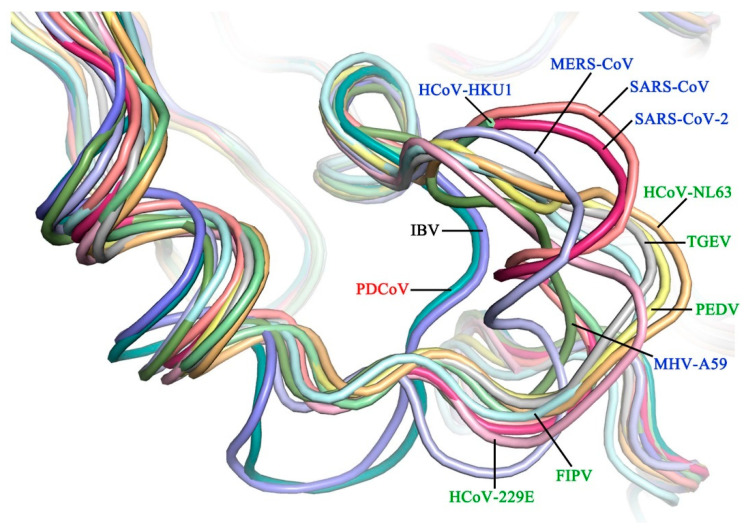

We cocrystallized PDCoV Mpro with a Michael acceptor inhibitor, named N3, and determined the structure of the complex at 2.60 Å resolution (Table 1). The crystal structure contained six Mpro molecules per asymmetric unit. In the crystals, two neighboring molecules, protomer A and protomer B, formed a typical homodimer. Each protomer contains three domains: domain I (residues 1–97), domain II (residues 98–186) and domain III (residues 200–304). Domain I and II each have a chymotrypsin-like fold, and domain III is composed of five α-helixes and contributes to the formation of a homodimer (Figure 1A). The substrate-binding pocket, which contains a catalytic dyad (His-41 and Cys-144), is located in the cleft between domains I and II (Figure 1A). The superimposition of Mpros [15,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] from four different CoV genera shows that the PDCoV Mpro shares a similar overall structure and backbone with other CoV Mpros (Figure 1B). Domain I (residues 1–97) and domain II (residues 98–186) of Mpro from PDCoV are well conserved, with Cα root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs) of 1.4–1.7 Å, 1.3–1.4 Å and 1.1 Å in comparison with those of alpha-, beta-, and gamma-CoV, respectively. Structural overlay of the Mpros from four CoV genera shows that domain III (residues 200–304) of PDCoV has a similar orientation to that of the other CoV Mpros. The Cα RMSDs between different CoVs and PDCoV are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

X-ray data-processing and refinement statistics.

| Statistics | Value for the Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) main protease (Mpro)-N3 Complex |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97923 |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 50.00–2.60 (2.64–2.60) |

| Space group | P61 |

| Cell parameters | |

| a (Å) | 122.29 |

| b (Å) | 122.29 |

| c (Å) | 289.75 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 |

| Total no. of reflections | 75,173 (3733) |

| No. of unique reflections | 74,737 (7392) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (99.3) |

| Redundancy | 20.5 (20.3) |

| Rmerge (%) | 17.2 (>100) |

| Sigma cutoff | 0 |

| I/σ(I) | 12.4 (1.1) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 49.74–2.60 |

| Rwork (%) | 19.21 |

| Rfree a (%) | 24.14 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 14,122 |

| Water | 461 |

| Ligands | 294 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 57.29 |

| Water | 47.07 |

| Ligands | 69.01 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.72 |

| Ramachandran | |

| Favored (%) | 96.05 |

| Allowed (%) | 3.95 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.00 |

aRfree was calculated with 5% of the reflection data. Refinement statistics were calculated with the table one utility of PHENIX.

Figure 1.

Structure of Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) main protease (Mpro). (A) Overall structure of the PDCoV Mpro-N3 complex. The two protomers, A and B, are colored violet and deep teal, respectively; the substrate-binding pocket is indicated by dashed lines; inhibitor N3 is shown as green sticks; and the catalytic dyads Cys-144 and His-41 are colored yellow. (B) Superposition of a representative CoV Mpro from each of four genera: Deltacoronavirus (PDCoV, deep teal) and three other genera (human coronavirus NL63 [HCoV-NL63], human coronavirus 229E [HCoV-229E], porcine epidemic diarrhea virus [PEDV], feline infectious peritonitis virus [FIPV], transmissible gastroenteritis virus [TGEV], severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2], severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [SARS-CoV], Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus [MERS-CoV], human coronavirus HKU1 [HCoV-HKU1], mouse hepatitis virus A59 [MHV-A59] and infectious bronchitis virus [IBV], silver).

Table 2.

The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values of domain I and domain II or domain III between the structures of PDCoV Mpro and Mpros from three other CoV genera.

| Genus | Coronaviruses | RMSD (Å) (Domain I and Domain II) |

RMSD (Å) (Domain III) |

PDB ID | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alphacoronavirus | HCoV-NL63 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 5GWY | [26] |

| HCoV-229E | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2ZU2 | [24] | |

| FIPV | 1.5 | 1.6 | 5EU8 | [25] | |

| PEDV | 1.4 | 1.7 | 5GWZ | [27] | |

| TGEV | 1.7 | 1.6 | 2AMP | [15] | |

| Betacoronavirus | SARS-CoV-2 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 6LU7 | [23] |

| SARS-CoV | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2AMQ | [15] | |

| MERS-CoV | 1.3 | 1.6 | 5C3N | [22] | |

| HCoV-HKU1 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 3D23 | [29] | |

| MHV-A59 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 6JIJ | [21] | |

| Gammacoronavirus | IBV | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2Q6F | [28] |

Human coronavirus NL63, HCoV-NL63; Human coronavirus 229E, HCoV-229E; Feline infectious peritonitis virus, FIPV; Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, PEDV; Transmissible gastroenteritis virus, TGEV; Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2; Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV; Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, MERS-CoV; Human coronavirus HKU1, HCoV-HKU1; Mouse hepatitis virus A59, MHV-A59; Infectious bronchitis virus, IBV.

3.2. The Substrate-Binding Pocket PDCoV Mpro Is Structurally Conserved Relative to Mpros from the Other Three Genera

To provide more insight into the properties of PDCoV Mpro, we analyzed the substrate-binding pocket between domain I and domain II.

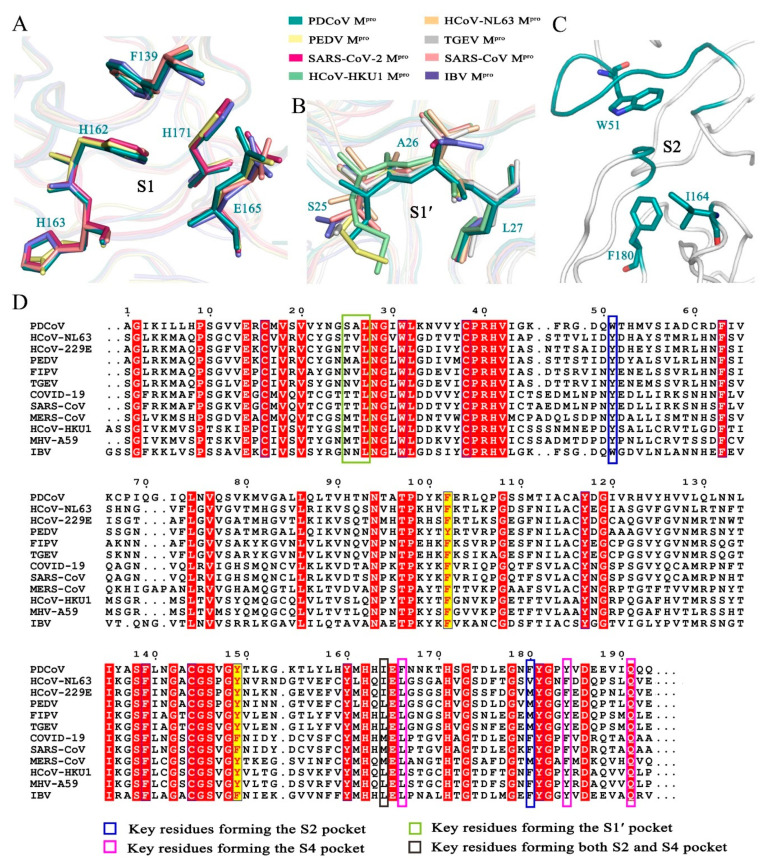

The S1 binding pocket of PDCoV Mpro is composed of residues Phe-139, His-162, Glu-165, and His-171 and the backbones of the other amino acids, such as Leu-140, Asn-141, His-163 and Ile-164. Sequence analysis showed that the Mpro cleavage sites at the P1 position in the identified PDCoV were all glutamines, indicating that the S1 substrate-binding pocket of PDCoV Mpro has an extremely strong preference for glutamine residues. In our previously reported structure of the complex between a SARS-CoV Mpro H41A mutant and an 11-peptidyl substrate, the Nε2 atom of His-163 and the main chain carbonyl oxygen of Phe-140 in the S1 binding pocket form three hydrogen bonds with glutamine at the P1 position [28]. Structural superposition of the S1 binding pocket in Mpros from the CoVs of four genera showed that in PDCoV Mpro, the carbonyl oxygen atom of Phe-139, the imidazole ring NH of His-162 and the carbonyl oxygen atoms of residues at position 163 in PDCoV Mpro, PEDV Mpro, SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, SARS-CoV Mpro and IBV Mpro are extremely conserved. In addition, we found that the key residues that form the S1 binding pocket, His-171 and Glu-165, also share a similar structure (Figure 2A). For the above reasons, we concluded that the Deltacoronavirus PDCoV Mpro shares a conserved S1 binding pocket with Mpros from the other three genera. The evolutionary conservation of amino acids plays a crucial role in drug design.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the substrate-binding pocket of PDCoV Mpro. (A) Superimposition of the key residues in the S1 binding pockets of PDCoV Mpro (deep teal), PEDV Mpro (pale yellow), SARS-CoV Mpro (salmon) and IBV Mpro (slate). (B) Superimposition of the key residues in the S1′ binding pocket of PDCoV Mpro (deep teal), HCoV-HKU1 Mpro (pale green), HCoV-NL63 Mpro (light orange), PEDV Mpro (pale yellow), SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (warm pink), SARS-CoV Mpro (salmon), TGEV Mpro (silver) and IBV Mpro (slate). (C) Hydrophobic residues in the S2 binding pocket. (D) Sequence alignment of the Mpro domains I and II from four different genera. PDCoV from Deltacoronavirus; HCoV-NL63, PEDV, FIPV, TGEV from Alphacoronavirus; SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, HCoV-HKU1, MHV-A59 from Betacoronavirus; IBV from Gammacoronavirus. A sequence alignment was generated using the program ClustalW and drawn by ESPript3. White letters with red backgrounds show identical residues, and red letters with yellow backgrounds show conservative variation.

In the structure of PDCoV Mpro, the side chains of Trp-51, Ile-164 and Phe-180 as well as residues 186–188 and a loop from 41–51 form a deep, hydrophobic S2 binding pocket. Residues 186–188 and a loop from 41–51 contribute to the outer wall of the S2 site (Figure 2C). Furthermore, the side chains of the hydrophobic amino acids Trp-51, Ile-164 and Phe-180 of the S2 subsite interact with residues at the P2 position through hydrophobic interactions. The S2 subsite of CoV Mpros usually prefers a hydrophobic residue. Leucine is the most common residue at the P2 site. The Mpros of HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E from Alphacoronavirus recognize Leu/Ile/Val; those of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, HCoV-HKU1, and MERS-CoV from Betacoronavirus seem to prefer Phe/Met/Pro/Leu/Val. The residues at the P2 position of Mpro from Gammacoronavirus viruses such as IBV are Leu/Met/Val. In Deltacoronavirus viruses such as PDCoV, this position favors Val/Leu. The corresponding residues at positions 51, 164 and 180 of Mpros from the other three genera of CoVs are extremely similar and are almost always hydrophobic amino acids, such as Phe, Leu, Met, Val, Ile, Trp and Tyr, contributing to the interactions between the binding pocket and substrate (Figure 2D).

The S4 binding pocket of PDCoV Mpro is composed of residues 164–167, 183–184 and 188–191. The side chains of Ile-164, Phe-166, Tyr-184, and Gln-191 form the hydrophobic S4 subsite of PDCoV Mpro. Sequence alignment showed that the conserved hydrophobic amino acids in the S4 binding pocket play a key role in hydrophobic interactions (Figure 2D).

Residues Ser-25, Ala-26, Leu-27, His-41, Val-42, Lys-45 and Asn-141 form the S1′ binding pocket. The side chains of the amino acids at positions 25, 26 and 27 directly interact with the P1′ residue of the substrate via van der Waals interactions [28]. The backbone atoms of the residues that form the S1′ pocket of PDCoV Mpro are similar to the corresponding sequences in the other three genera. Sequence alignment showed that the residues at position 25 of Mpro from PDCoV, PEDV, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and IBV are different from the consensus of the CoV Mpros from the four genera; these residues are Thr, Met, Asn and Ser, respectively (Figure 2B,D).

3.3. The Peptidomimetic Inhibitor N3 Efficiently Inhibits PDCoV Mpro

We determined the Km and kcat of PDCoV Mpro to be 56.6 ± 1.9 µM and 0.030 ± 0.009 s−1, respectively (Table 3). This Km value is close to that of HCoV-NL63 Mpro (50.8 ± 3.4 µM) and TGEV Mpro (61 ± 5 µM), lower than that of mouse hepatitis virus A59 (MHV-A59) Mpro (77 ± 5 µM), HCoV-HKU1 Mpro (83.2 ± 13.3 µM), SARS-CoV Mpro (129 ± 7 µM) and IBV Mpro (139 ± 15 µM), and higher than that of HCoV-229E Mpro (29.8 ± 0.9 µM) and FIPV Mpro (13.5 ± 1.8 µM) [15,26,29] (Table 3). Structural analysis showed that the substrate-binding pocket of PDCoV Mpro shares several features in common with Mpros from CoVs in the other three genera, especially the S1, S2 and S4 subsites. The key residues at these sites are almost completely conserved (Figure 2). The N3 is a peptidomimetic inhibitor designed against various Mpros, such as those from SARS-CoV, HCoV-229E and FIPV [15]. Therefore, we deduced that the Michael acceptor and peptidomimetic inhibitor N3 may inhibit PDCoV Mpro. An enzymatic assay showed that N3 inactivated PDCoV Mpro. The calculated Ki and k3 were 11.98 ± 0.13 µM and 72.91 ± 7.05 (10−3 s−1), respectively. The k3 is approximately 23-fold larger than that of SARS-CoV Mpro, which indicates that N3 inactivates PDCoV Mpro faster than it does SARS-CoV.

Table 3.

The Km and kcat values of the representative Mpros from different CoVs.

| Genus | Coronaviruses |

Km (µM) |

kcat (s−1) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deltacoronavirus | PDCoV | 56.6 ± 1.9 | 0.030 ± 0.009 | In this study |

| Alphacoronavirus | HCoV-NL63 | 50.8± 3.4 | 0.098 ± 0.004 | [26] |

| HCoV-229E | 29.8 ± 0.9 | 1.27 ± 0.09 | [15] | |

| FIPV | 13.5 ± 1.8 | 0.6 ± 0.06 | [15] | |

| TGEV | 61 ± 5 | 1.39 ± 0.09 | [15] | |

| Betacoronavirus | SARS-CoV | 129 ± 7 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | [15] |

| HCoV-HKU1 | 83.2 ± 13.3 | 1.1 ± 0.12 | [29] | |

| MHV-A59 | 77 ± 5 | 0.083 ± 0.006 | [15] | |

| Gammacoronavirus | IBV | 139 ± 15 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | [15] |

Porcine deltacoronavirus, PDCoV; Human coronavirus NL63, HCoV-NL63; Human coronavirus 229E, HCoV-229E; Feline infectious peritonitis virus, FIPV; Transmissible gastroenteritis virus, TGEV; Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV; Human coronavirus HKU1, HCoV-HKU1; Mouse hepatitis virus A59, MHV-A59; Infectious bronchitis virus, IBV.

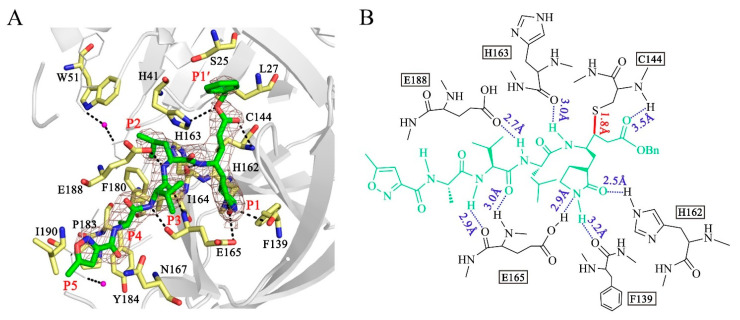

3.4. Binding of N3 to PDCoV Mpro

In the crystal structures, N3 is bound to each protomer of the Mpro dimer. We thus only discuss the binding mode in one of the protomers. The inhibitor is located in the substrate-binding pocket, which adopts the canonical conformation seen in other Mpro-N3 complex structures. As an irreversible inhibitor, the Cβ atom of the vinyl group on N3 is bound to the Sγ atom of Cys-144 through a 1.8 Å covalent bond (Figure 3A,B). The lactam ring of the glutamine analog N3 at the P1 site inserts into the S1 pocket and forms 3.2 Å, 2.5 Å and 2.9 Å hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygen of Phe-139, the imidazole ring NH of His-162 and the Oε1 atom of Glu-165, respectively. The side chain of Leu at the P2 position extends into the S2 pocket and participates in hydrophobic interactions with the hydrophobic amino acids Trp, Ile and Phe. The valine side chain of N3 at the P3 position is exposed to solvent. The alanine residue in the P4 position inserts into a pocket composed of the residues Pro-183 and Tyr-184, leading to a hydrophobic interaction among these residues. The isoxazole at the P5 position, Gln-167 and Ile-190 form a “sandwich structure” by van der Waals interaction. The P2 and P4 sites insert into the S2 subsite and S4 subsite well. Moreover, the backbone NH of Cys-144, the carbonyl oxygen atoms of His-163 and Glu-165, the Oε1 atom of Glu-188 and the NH group of Glu-165 form hydrogen bonds with the inhibitor N3, which ensures tight binding between the Mpro and the inhibitor, as shown in Figure 3. We concluded that peptidomimetic inhibitors carrying the Michael acceptor warhead N3 are effective against the Mpro of PDCoV.

Figure 3.

Structure of the interaction between N3 and PDCoV Mpro. (A) Stereoview of N3 bound to the substrate-binding pocket of PDCoV Mpro. N3 is colored green and shown with a simulated annealing 2mFo-DFc omit map contoured at 1.0 σ. The residues at the substrate-binding pocket that contribute to the interaction between N3 and PDCoV Mpro are shown in yellow. Waters are shown in magenta. The P1′, P1, P2, P3, P4 and P5 sites are labeled. (B) Detailed interactions between PDCoV Mpro and N3. N3 is shown in green. Hydrogen bonds are shown as blue dashed lines. The covalent bond formed by N3 and the Sγ atom of Cys-144 is shown as a solid red line.

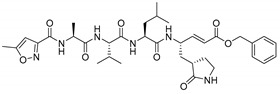

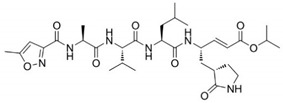

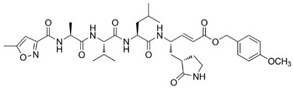

3.5. The P1′ Position May Play an Important Role in the Interaction between PDCoV Mpro and Inhibitors

Previously, we have designed 16 N3 derivatives that target PEDV Mpro (the detailed structures and their chemical synthesis were described in our previous paper) [27]. Next, we evaluated the inhibitory activity of these compounds against PDCoV Mpro. Among these compounds, M14 and M25 exhibited stronger inhibition than N3 (Table 4). The k3/Ki values of M14 and M25 were 13.8 and 9.9, respectively, indicating that they have much better inhibitory activity than N3, which had a k3/Ki of 6.1. The detailed inhibition parameters of N3, M14 and M25 are listed in Table 5. Interestingly, we found that the three compounds shared the same side groups at all positions except the P1′ position (Table 5). The benzyl group at the P1′ position of N3 interacts with Ser-25 and Leu-27 through van der Waals forces. Therefore, we suggest that rational design of the P1′ position could dramatically enhance the interaction between the substrate-binding pocket and the inhibitor. Future modification of peptidomimetic inhibitors at the P1′ position has the potential to control acute gastroenteritis in pigs infected with PDCoV.

Table 4.

Evaluation of the inhibitory activity of compounds targeting PDCoV Mpro. The inhibition ratio (Ir) is defined as the percent inactivation of the initial enzymatic activity of PDCoV Mpro.

| Compound | Inhibition Ratio (Ir) | Inhibitory Activity a |

|---|---|---|

| N3 | 62% | + + + |

| M1 c | 37% | + + |

| M2 c | 53% | + + + |

| M3 c | 21% | + |

| M5 c | - | N/A b |

| M6 c | - | N/A |

| M7 c | 30% | + + |

| M8 c | 20% | + |

| M10 c | 62% | + + + |

| M11 c | 23% | + |

| M12 c | 27% | + |

| M13 c | 21% | + |

| M14 c | 82% | + + + + + |

| M17 c | 39% | + + |

| M18 c | 50% | + + + |

| M19 c | 53% | + + + |

| M25 c | 74% | + + + + |

a Percentage inhibitory activity: + + + + +, >80%; + + + +, 70%−80%; + + +, 50%−70%; + +, 30%−50%; +, <30%. b No inhibition was observed. c The detailed structures and chemical synthesis of the compounds were described in reference [27].

Table 5.

Enzyme inhibition data for inhibitors of PDCoV Mpro.

| Compound | Structure | Ki (µM) | k3 (10−3s−1) | k3/Ki |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N3 |

|

11.98 ± 0.13 | 72.9 ± 7.1 | 6.1 |

| M14 |

|

7.56 ± 0.26 | 104.4 ± 2.3 | 13.8 |

| M25 |

|

8.80 ± 0.15 | 86.8 ± 5.1 | 9.9 |

4. Discussion

The Mpro is an ideal target for drug design against CoVs. Since IBV, the first CoV to be described was discovered in 1937, four genera of CoVs have been identified. Currently, we have a thorough understanding of the Mpro structures of alpha-, beta- and gamma-CoVs; however, we know little about the Deltacoronavirus Mpro. In this paper, we present the first structure of the Mpro of a newly emerged Deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) in complex with a Michael acceptor inhibitor.

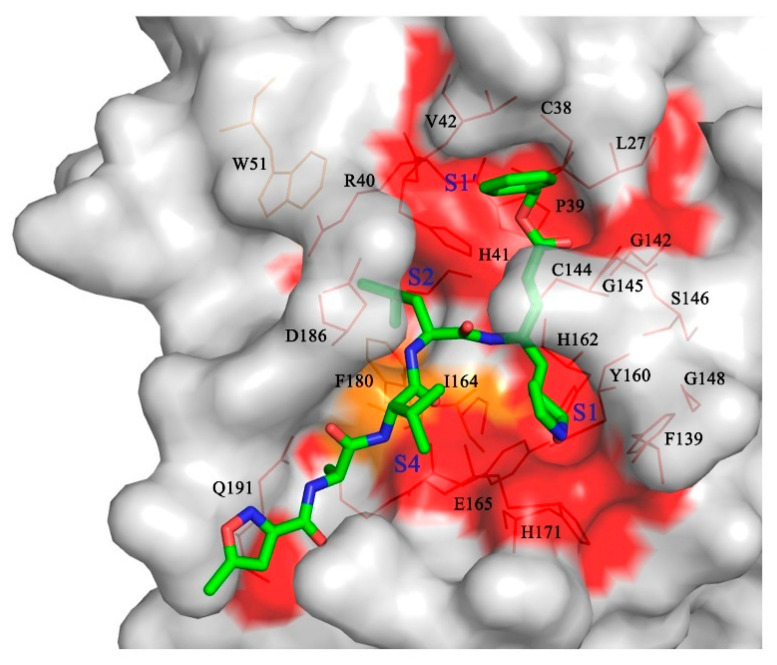

As observed in the previously reported Mpro structures, PDCoV Mpro presented a functional homodimer and conserved His-Cys dyads. Furthermore, a detailed comparison of the Mpro structures showed that PDCoV Mpro shares a similar overall structure and a relatively conserved substrate-binding pocket with the Mpros of the other three CoV genera, especially the key residues located at the S1, S4, and S2 subsites (Figure 4). Meanwhile, the irreversible inhibitor N3 in our structure, designed based on the structure of SARS Mpro in complex with its substrate, could inactivate PDCoV and multiple CoV Mpros. These results also proved the conservation of the overall structures and substrate binding pockets of Mpros. As demonstrated, emerging zoonotic viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are a potential threat to public health because of the existing viral variants. As an important pathogen of piglets, the nonhuman animal virus PDCoV poses the risk of cross-species transmission to humans as well [30,31]. Therefore, the conserved CoV Mpro we identified could be considered a drug target in the event of genetic changes during human-to-human or animal-to-human transmission of CoVs.

Figure 4.

Structure-based substrate-binding pocket conservation analysis of Mpros from four different genera. Surface representation showing the conserved substrate-binding pockets from the ten CoV Mpros listed in Figure 2B. The background is PDCoV Mpro. Red: identical residues among all ten CoV Mpros; orange: substituted in two CoV Mpros. The S1, S2, S4, and S1′ pockets and the residues that form the substrate-binding pocket are labeled. N3 is shown in green.

Interestingly, the structure and conformation of Mpros presented a stable characteristic evolution and obvious species correlation. We superposed the determined structures of Mpros from CoVs in four different genera and found some loops, especially for the region from 41–51, that exhibited corresponding features (Figure 5). For example, this loop in Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus forms a 310 helix, while in Gammacoronavirus IBV, it forms a short loop. Surprisingly, the loop from residues 41–51 of PDCoV Mpro adopts a conformation similar to that of IBV Mpro, which supports that the Deltacoronavirus may be closely related to Gammacoronavirus [6]. Since the loop from 41–51 is associated with the outer wall of the S2 pocket, our structural information will support reasonable broad-spectrum peptidomimetic drug design based on the evolutionary conservation of Mpros from CoVs.

Figure 5.

Structures of the backbone of a loop containing residues 41–51 in Mpros from four different genera (PDCoV, deep teal; HCoV-NL63, light orange; HCoV-229E, light pink; FIPV, pale cyan; PEDV, pale yellow; TGEV, silver; SARS-CoV-2, warm pink; SARS-CoV, salmon; MERS-CoV, light blue; HCoV-HKU1, pale green; MHV-A59, sumudge; IBV, slate).

The peptidomimetic inhibitor N3, which carries a Michael acceptor warhead, was also effective against Mpro of PDCoV, the newly emerging Deltacoronavirus. Peptidomimetic compounds are attractive inhibitors for the development of novel antiviral therapies. These compounds target proteases that are essential for viral replication. For example, boceprevir, telaprevir and simeprevir are peptidomimetic drugs that act as viral NS3/4A serine protease inhibitors of hepatitis C virus (HCV) [43,44,45], while saquinavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, and amprenavir are clinically approved human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitors, which have a similar molecular structure to the protease substrate [46,47]. Furthermore, these peptidomimetic drugs were derived from lead compounds identified based on viral protease structures. For instance, boceprevir, which is a tripeptide derivative that forms a covalent bond with Ser-139 to inactivate the NS3/4A protease [45], was designed based on an undecapeptide alpha-ketoamide inhibitor identified from compound libraries. Hence, after multiple rounds of modification, the inhibitor N3 is a currently available compound for broad-spectrum drug design. It is worth noting that P1′ may be a key position of compound modification for broad-spectrum drug design because of the side chains variability in the amino acid at position 25, which directly participates in the interaction with the inhibitor. In our study, both N3 derivatives (M14 and M25) with improved inhibitory activity against PDCoV Mpro presented a unique group at P1′. Therefore, it is necessary to balance the relatively conserved substrate binding pockets during rational drug design. Furthermore, we found that M25 exhibited potent inhibition of both PDCoV and PEDV Mpro proteins [27]. The two main emerging swine CoVs, PDCoV and PEDV, account for the majority of lethal watery diarrhea in neonatal pigs in the past decade. More recently, the epidemiological evidence shows that the rate of PDCoV coinfection with PEDV has increased up to 51% in China [32,48]. Therefore, M25 could be further developed to combat both PDCoV and PEDV infection in the swine industry.

In summary, the structure of PDCoV Mpro in complex with the Michael acceptor inhibitor N3 provides a basis for the inactivation of Deltacoronavirus viral proteases. The structural comparison of different viral enzymes identified a conserved substrate-binding pocket in all CoV Mpros; this pocket is a target for the development of broad-spectrum antivirals against all existing and emerging CoVs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zuokun Lu for data collection at beamlines BL17U1, BL18U1 and BL19U1 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.W., C.C. and H.Y.; Formal analysis, F.W., P.S. and Y.X.; Funding acquisition, H.Y.; Investigation, F.W., X.H., K.Z. and X.L.; Methodology, C.C.; Project administration, H.Y.; Resources, Z.W. and Y.C.; Supervision, H.Y.; Validation, F.W.; Writing—original draft, F.W.; Writing—review & editing, J.H., L.Z. and H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Lingang Laboratory (grant No. LG202101-01-07 to H.Y.), the National Key R&D Program of China (grant No. 2020YFA0707502 to H.Y.), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant No. YDZX20213100001556 and 20XD1422900 to H.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 92169109 to H.Y.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates for the crystal structure of PDCoV Mpro in complex with N3 can be accessed using PDB code 7WKU in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb7WKU/pdb accessed on 25 January 2022). Authors will release the atomic coordinates and experimental data upon article publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Masters P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J., Lai S., Gao G.F., Shi W. The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;600:408–418. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss S.R., Leibowitz J.L. Coronavirus pathogenesis. Adv. Virus Res. 2011;81:85–164. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385885-6.00009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delaplace M., Huet H., Gambino A., Le Poder S. Feline coronavirus antivirals: A review. Pathogens. 2021;10:1150. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackwood M.W. Review of infectious bronchitis virus around the world. Avian Dis. 2012;56:634–641. doi: 10.1637/10227-043012-Review.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Lam C.S., Lau C.C., Tsang A.K., Lau J.H., Bai R., Teng J.L., Tsang C.C., Wang M., et al. Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphac oronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. J. Virol. 2012;86:3995–4008. doi: 10.1128/Jvi.06540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A., et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W., et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuiken T., Fouchier R.A., Schutten M., Rimmelzwaan G.F., van Amerongen G., van Riel D., Laman J.D., de Jong T., van Doornum G., Lim W., et al. Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;362:263–270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13967-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Situation Report. 2022. [(accessed on 17 January 2022)]. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/

- 13.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zumla A., Chan J.F., Azhar E.I., Hui D.S., Yuen K.Y. Coronaviruses-drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:327–347. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H., Xie W., Xue X., Yang K., Ma J., Liang W., Zhao Q., Zhou Z., Pei D., Ziebuhr J., et al. Design of wide-spectrum inhibitors targeting coronavirus main proteases. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:1742–1752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung K., Hu H., Saif L.J. Porcine deltacoronavirus infection: Etiology, cell culture for virus isolation and propagation, molecular epidemiology and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2016;226:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziebuhr J., Bayer S., Cowley J.A., Gorbalenya A.E. The 3C-like proteinase of an invertebrate nidovirus links coronavirus and potyvirus homologs. J. Virol. 2003;77:1415–1426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1415-1426.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: Basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science. 2003;300:1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H., Yang M., Ding Y., Liu Y., Lou Z., Zhou Z., Sun L., Mo L., Ye S., Pang H., et al. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:13190–13195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anand K., Palm G.J., Mesters J.R., Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra alpha-helical domain. Embo. J. 2002;21:3213–3224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cui W., Cui S.S., Chen C., Chen X., Wang Z.F., Yang H.T., Zhang L. The crystal structure of main protease from mouse hepatitis virus A59 in complex with an inhibitor. Biochem Bioph. Res. Co. 2019;511:794–799. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho B.L., Cheng S.C., Shi L., Wang T.Y., Ho K.I., Chou C.Y. Critical assessment of the important residues involved in the dimerization and catalysis of MERS coronavirus main protease. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., et al. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C.C., Kuo C.J., Ko T.P., Hsu M.F., Tsui Y.C., Chang S.C., Yang S., Chen S.J., Chen H.C., Hsu M.C., et al. Structural basis of inhibition specificities of 3C and 3C-like proteases by zinc-coordinating and peptidomimetic compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:7646–7655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807947200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang F., Chen C., Liu X., Yang K., Xu X., Yang H. Crystal structure of feline infectious peritonitis virus main protease in complex with synergetic dual inhibitors. J. Virol. 2016;90:1910–1917. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02685-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang F., Chen C., Tan W., Yang K., Yang H. Structure of main protease from human coronavirus NL63: Insights for wide spectrum anti-coronavirus drug design. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:2267710. doi: 10.1038/srep22677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang F., Chen C., Yang K., Xu Y., Liu X., Gao F., Liu H., Chen X., Zhao Q., Liu X., et al. Michael acceptor-based peptidomimetic inhibitor of main protease from porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:3212–3216. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue X., Yu H., Yang H., Xue F., Wu Z., Shen W., Li J., Zhou Z., Ding Y., Zhao Q., et al. Structures of two coronavirus main proteases: Implications for substrate binding and antiviral drug design. J. Virol. 2008;82:2515–2527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02114-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Q., Li S., Xue F., Zou Y.L., Chen C., Bartlam M., Rao Z. Structure of the main protease from a global infectious human coronavirus, HCoV-HKU1. J. Virol. 2008;82:8647–8655. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00298-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lednicky J.A., Tagliamonte M.S., White S.K., Elbadry M.A., Alam M.M., Stephenson C.J., Bonny T.S., Loeb J.C., Telisma T., Chavannes S., et al. Independent infections of porcine deltacoronavirus among Haitian children. Nature. 2021;600:133–137. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04111-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W.T., Hulswit R.J., Kenney S.P., Widjaja I., Jung K., Alhamo M.A., van Dieren B., van Kuppeveld F.J., Saif L.J., Bosch B.J. Broad receptor engagement of an emerging global coronavirus may potentiate its diverse cross-species transmissibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E5135–E5143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1802879115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong N., Fang L., Zeng S., Sun Q., Chen H., Xiao S. Porcine deltacoronavirus in mainland China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:2254–2255. doi: 10.3201/eid2112.150283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S., Lee C. Complete genome characterization of Korean porcine deltacoronavirus strain KOR/KNU14-04/2014. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e01191-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01191-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thachil A., Gerber P.F., Xiao C.T., Huang Y.W., Opriessnig T. Development and application of an ELISA for the detection of porcine deltacoronavirus IgG antibodies. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0124363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L., Byrum B., Zhang Y. Detection and genetic characterization of deltacoronavirus in pigs, Ohio, USA, 2014. Emerg Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1227–1230. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Q.Z., Yoo D.W. Immune evasion of porcine enteric coronaviruses and viral modulation of antiviral innate signaling. Virus Res. 2016;226:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerdts V., Zakhartchouk A. Vaccines for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and other swine coronaviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;206:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jung K., Hu H., Eyerly B., Lu Z.Y., Chepngeno J., Saif L.J. Pathogenicity of 2 Porcine Deltacoronavirus Strains in Gnotobiotic Pigs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:650–654. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mccoy A.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D., Winn M.D., Storoni L.C., Read R.J. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winn M.D., Ballard C.C., Cowtan K.D., Dodson E.J., Emsley P., Evans P.R., Keegan R.M., Krissinel E.B., Leslie A.G., McCoy A., et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Cryst. D. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkoczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Cryst. D. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen S.H., Tan S.L. Discovery of small-molecule inhibitors of HCVNS3-4A protease as potential therapeutic agents against HCV infection. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:2317–2342. doi: 10.2174/0929867054864769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenquist A., Samuelsson B., Johansson P.O., Cummings M.D., Lenz O., Raboisson P., Simmen K., Vendeville S., de Kock H., Nilsson M., et al. Discovery and development of simeprevir (TMC435), a HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:1673–1693. doi: 10.1021/jm401507s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Venkatraman S. Discovery of boceprevir, a direct-acting NS3/4A protease inhibitor for treatment of chronic hepatitis C infections. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2012;33:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menendez-Arias L., Tozser J. HIV-1 protease inhibitors: Effects on HIV-2 replication and resistance. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2008;29:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mudgal M.M., Birudukota N., Doke M.A. Applications of click chemistry in the development of HIV protease inhibitors. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2018;2018:2946730. doi: 10.1155/2018/2946730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song D., Zhou X., Peng Q., Chen Y., Zhang F., Huang T., Zhang T., Li A., Huang D., Wu Q., et al. Newly emerged porcine deltacoronavirus associated with diarrhoea in swine in China: Identification, prevalence and full-length genome sequence analysis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2015;62:575–580. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates for the crystal structure of PDCoV Mpro in complex with N3 can be accessed using PDB code 7WKU in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb7WKU/pdb accessed on 25 January 2022). Authors will release the atomic coordinates and experimental data upon article publication.