Abstract

Fungi are an important and diverse component in various ecosystems. The methods to identify different fungi are an important step in any mycological study. Classical methods of fungal identification, which rely mainly on morphological characteristics and modern use of DNA based molecular techniques, have proven to be very helpful to explore their taxonomic identity. In the present compilation, we provide detailed information on estimates of fungi provided by different mycologistsover time. Along with this, a comprehensive analysis of the importance of classical and molecular methods is also presented. In orderto understand the utility of genus and species specific markers in fungal identification, a polyphasic approach to investigate various fungi is also presented in this paper. An account of the study of various fungi based on culture-based and cultureindependent methods is also provided here to understand the development and significance of both approaches. The available information on classical and modern methods compiled in this study revealed that the DNA based molecular studies are still scant, and more studies are required to achieve the accurate estimation of fungi present on earth.

Keywords: classical and molecular methods, fungal diversity, fungal phylogeny, identification, taxonomy

1. Introduction

Biodiversity is one of the most interesting aspects of biology, which has attracted the attention of scientists and researchers for some time. Biological diversity generally represents the variety of living beings from all sources, including terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems, covering the diversity of plants, animals, insects, pests and microbes. The information on biodiversity yet to be fully discovered may be useful from many beneficial and harmful aspects of life. Based on available information, biodiversity can be of species which are genetic and ecological, and found to be distributed in a variety of environments. The various life forms are adapted to live in specific environments, referred to as terrestrial and aquatic. In addition, these diverse life forms show great variability based on the type of habitats [1]. Fungi is an important component of biodiversity, which play an important role in various ecological cycles [2,3].

Fungi present enormous species diversity with respect to morphological, ecological and nutritional modes. Fungi are considered the largest organismic group after insects [4], andareknown to exist in a wide variety of morphologies, lifestyles, developmental patterns anda wide range of habitats such as soil, water, air, animals, plants and in environments with extreme conditions such as low or high temperature, high concentration of metals and salts [5,6,7]. It has been estimated that 1.5 and 5.1 million species of fungi are believed to exist in various ecosystems of Earth, of which nearly 150,000 species of fungi have been described [8,9,10].

Fungi are an important and diverse component of biodiversity in various ecosystems. These organisms consist of a diverse range of all major fungal groups and play the role of both foe and friend. While some fungi may cause numerous diseases in humans, animals, plants and other biological substrates, others may play an important role in the nutrient cycle. In addition, fungi have beneficial applications in the agriculture, industrial and pharmaceutical sectors. The occurrence of fungi, however, varies greatly with respect to various ecosystems and environments. The study of fungi is not easy due to the extremely high level of diversity and difficulty in the prediction ofexact estimates. However, different researchers predicted fungal diversity on the planet and provided different estimates of fungal species [3,11,12].

Identification based on morphological, phylogenetic or ecological characteristics is one of the most important aspectsof mycological studies. The classical methods of fungal identification which rely on direct observation of fungi either in a natural condition or after culturing on growth media are still most popularly in use. Despitethe use of molecular methods as more advanced modern techniques of fungal identification, the classical methods still have many advantages for studying fungal diversity. Some fungi produce visible structures useful in their identification. The culturing of some of the fungi is still not very successful; therefore, molecular techniques have proved to be very helpful in exploring their taxonomic identity [13,14]. The use of molecular methods along with conventional methods (morphological studies) helped mycologists to investigate the new fungal samples or reinvestigate the preserved ones. This has been led the fungal taxonomists to propose or establish many new taxa.

In the present paper, a general outline with current estimates of fungal diversity in all environments is presented. A complete section on general methods (classical and modern methods) used for fungal identification, along with their advantages and disadvantages, was also presentedin order to provide an updated account on fungal identification. Moreover, adetailed account of culture dependent and culture independent methods was providedin order to highlight their importancein fungal identification and their usefulness in finding updated fungal diversity estimates. Overall, this review will be a document containing present day information on various aspects of fungi.

2. Fungal Diversity: General Outline with Updated Estimates

Fungi constitute one of the largest groups of eukaryotes which play a significant role as decomposers, mutualists and pathogens. They are among the key components of global biodiversity, playing a powerful role in global biogeochemistry, recycling carbon and mobilizing nitrogen, phosphorus and other bio-elements. Besides performing this key role, fungi provide essential support to plant life in the form of endophytes and mycorrhizae, in addition to causing numerous plant and animal diseases. The industrial applications of various fungi nowadays are worth appreciating. Fungi as an important food source, and researchis still in progress to use fungal biomass to fulfil the basic needs of food, clothe and shelter [15,16]. Despite multiple uses, updated information of these organisms about the number of species are described, as well as global estimates of their diversitywhich are essential to accurately describe their taxonomic characteristics. Through the use of advanced methods of isolating and identifying fungi, a number of novel taxa have been established over the past decade, including new divisions, classes, orders and new families. Therefore, this section provides complete information on how to estimate fungal diversity based on the available literature.

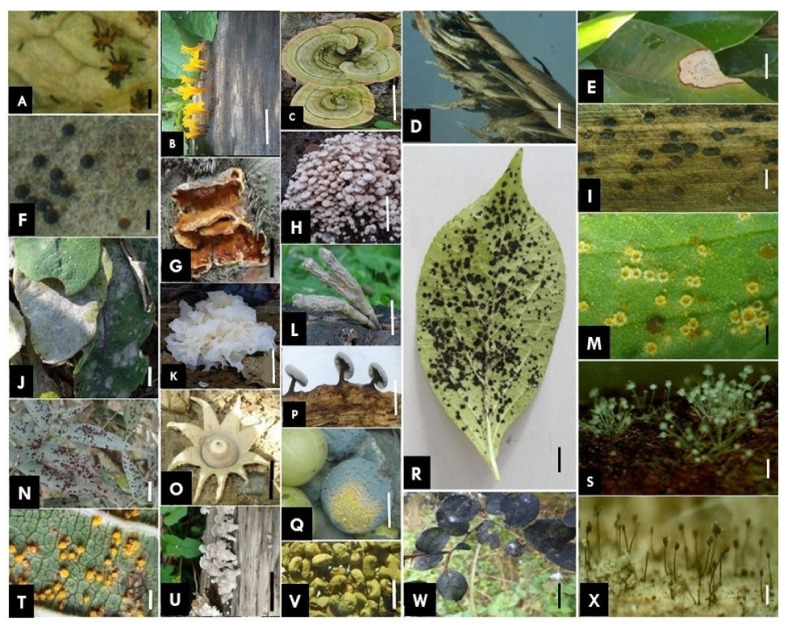

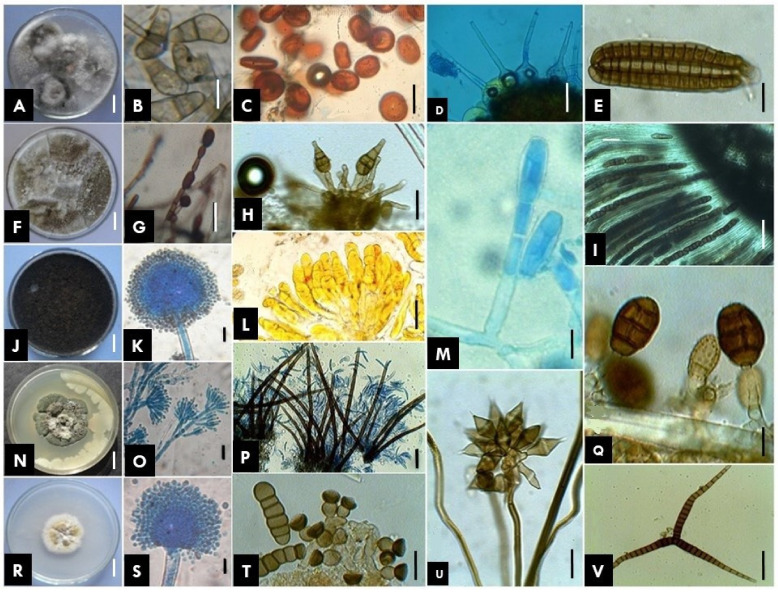

Classification of fungi or their various groups is a continuous process because of the regular inclusion of data based on morpho-taxonomy and molecular studies. The frequent inclusion of data from DNA sequences in recent studies is updating fungal outlines and their estimates constantly. The outline of fungi classification provided by Wijayawardene et al. [17] is used here as a starting point for this section of the paper. An outline of fungi and fungus-like taxa provides a summary of the classification of the kingdom Fungi (including fossil fungi, i.e., dispersed spores, mycelia, sporophores and mycorrhizas). A total of 19 phyla were presented with the placement of all fungal genera with the described number of species per genus at the class-, order-and family-level [17]. Several earlier studies have also focused on fungal diversity. Some glimpses of different types of fungi found in various habitats are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Diversity of different types of fungi. (A) Phragmidium sp. [rose rust], (B) Calocera sp., (C) Trametes sp., (D) Tilletia sp. [smut], (E) Colletotrichum sp. [Leaf spot], (F) Erysiphe sp. [Powdery mildew cleistothecia], (G) Inonotus sp., (H) Termitomyces sp., (I) Kweilingia sp. [rust], (J) Podosphaera sp. on Sonchus sp. [Powdery mildew], (K) Tremella sp., (L) Xylaria sp., (M) Uromyces sp. [aecia and telia], (N) Pileolaria sp. [rust], (O) Gaestrum sp., (P) Didymium sp., (Q) Penicillium sp. on Emblica sp., (R) Schiffnerula sp. [black mildew], (S) Aspergillus sp., (T) Coleosporium sp. [rust], (U) Schizophyllum sp., (V) Aspergillus sp. [on cow pea], (W) Mitteriella sp. [black mildew] and (X) Periconia sp. Scale bars A–X = 20 mm.

Figure 2.

Diversity of different types of fungi. (A,B) Curvularia sp., (C) Pileolaria sp. [rust], (D) Phyllactinia sp. [powdery mildew], (E) Dictyosporium sp., (F,G) Sytalidium sp., (H) Alternaria alternata, (I) Hypoxylon sp., (J,K) Aspergillus niger, (L) Coleosporium sp. [rust], (M) Podosphaera sp. [powdery mildew], (N,O) Penicillium sp. on Emblica sp., (P) Colletotrichum sp., (Q) Pithomyces sp., (R,S) Aspergillus falvus, (T) Torula sp., (U) Beltrania sp., (V) Ceratosporium sp. Scale bars A,F,J,N,R = 1 mm; B–E,G–I,K–M,O–Q,S–V = 10 µm.

Based on phylogenies and the divergence time of particular taxa, Tedersoo et al. [18] proposed classification of kingdom Fungi into 18 phyla Ascomycota, Aphelidiomycota, Basidiobolomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Calcarisporiellomycota, Chytridiomycota, Entomophthoromycota, Entorrhizomycota, Glomeromycota, Kickxellomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Mortierellomycota, Mucoromycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Olpidiomycota, Rozellomycota and Zoopagomycota. Because this study was based on only 111 taxa, its universal acceptance remained a matter of thinking. In this agreement, Wijayawardene et al. [19] provided a revised classification system for basal clades of fungi from phyla to genera in the same year. A total of 16 phyla were accepted among the above-mentioned except viz. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. The detailed information to fully resolved tree of life was reviewed by James et al. [20], where they provide detailed information on advancements in genomic technologies during the last 15 years to understand the revolution in fungal systematics in the phylogenomic era. However, the recently updated outline of fungi given by Wijayawardene et al. [17] revised the number of phyla upto 19 in addition to Caulochytriomycota. This group of researchers also included fungal-like taxa in this study and incorporated them in this outline. Similar studies on outlined fungal phyla were carried outoccasionally. These studies proved very useful for researchers engaged in updating fungal classification. A list of selected literature based on various taxonomical studies carried out by several researchers is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected literature on various taxonomical studies of fungi.

| Title | Reference |

|---|---|

| Orders of Ascomycetes | [41] |

| Laboulbeniales as a separate class of Ascomycota, Laboulbeniomycetes | [42] |

| One hundred and seventeen clades of euagarics | [43] |

| Toward resolving family-level relationships in rust fungi (Uredinales) | [44] |

| Higher level classification of Pucciniomycotina based on combined analyses of nuclear large and small subunit rDNA sequences | [45] |

| A phylogenetic overview of the family Pyronemataceae (Ascomycota, Pezizales) | [46] |

| A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi | [47] |

| Dictionary of the Fungi. (10th edn) | [48] |

| Outline of Ascomycota | [49] |

| Glomeromycota: two new classes and a new order | [50] |

| Entomophthoromycota: a new phylum and reclassification for entomophthoroid fungi | [51] |

| Incorporating anamorphic fungi in a natural classification checklist and notes for 2011 | [52] |

| Taxonomic revision of Ustilago, Sporisorium and Macalpinomyces | [53] |

| Phylogenetic systematics of the Gigasporales | [54] |

| List of generic names of fungi for protection under the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants | [55] |

| A phylogeny of the highly diverse cup fungus family Pyronemataceae (Pezizomycetes, Ascomycota) | [56] |

| Families of Dothideomycetes | [57] |

| Taxonomic revision of the Lyophyllaceae (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) based on a multigene phylogeny | [58] |

| Recommended names for pleomorphic genera in Dothideomycetes | [27] |

| Towards a natural classification and backbone tree for Sordariomycetes | [34] |

| Phylogenetic classification of yeasts and related taxa within Pucciniomycotina | [59] |

| Entomophthoromycota: a new overview of some of the oldest terrestrial fungi | [60] |

| Systematics of Kickxellomycotina, Mortierellomycotina, Mucoromycotina, and Zoopagomycotina | [61] |

| A phylum-level phylogenetic classification of Zygomycete fungi based on genome–scale data | [62] |

| Phylogenomics of a new fungal phylum reveals multiple waves of reductive evolution across Holomycota | [63] |

| Sequence–based classification and identification of fungi | [64] |

| Morphology-based taxonomic delusions: Acrocordiella, Basiseptospora, Blogiascospora, Clypeosphaeria, Hymenopleella, Lepteutypa, Pseudapiospora, Requienella, Seiridium and Strickeria | [65] |

| Families of Sordariomycetes | [35] |

| Proposal to conserve the name Diaporthe eres, with a conserved type, against all other competing names (Ascomycota, Diaporthales, Diaporthaceae) | [66] |

| Taxonomy and phylogeny of dematiaceous Coelomycetes | [67] |

| Multigene phylogeny of Endogonales | [68] |

| Classification of lichenized fungi in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota-Approaching one thousand genera | [69] |

| Taxonomy and phylogeny of the Auriculariales (Agaricomycetes, Basidiomycota) with stereoid basidiocarps | [70] |

| An updated phylogeny of Sordariomycetes based on phylogenetic and molecular clock evidence | [71] |

| Families, genera, and species of Botryosphaeriales | [72] |

| Ranking higher taxa using divergence times: a case study in Dothideomycetes | [73] |

| A revised family-level classification of the Polyporales (Basidiomycota) | [74] |

| Notes for genera: Ascomycota | [22] |

| Towards incorporating asexual fungi in a natural classification: checklist and notes 2012–2016 |

[23] |

| Notes for genera: basal clades of Fungi (including Aphelidiomycota, Basidiobolomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Calcarisporiellomycota, Caulochytriomycota, Chytridiomycota, Entomophthoromycota, Glomeromycota, Kickxellomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Mortierellomycota, Mucoromycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Olpidiomycota, Rozellomycota and Zoopagomycota) | [19] |

| Outline of Ascomycota: 2017 | [75] |

| Classification of orders and families in the two major subclasses of Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota) based on a temporal approach | [76] |

| A taxonomic summary and revision of Rozella (Cryptomycota) | [77] |

| Sexual and asexual generic names in Pucciniomycotina and Ustilaginomycotina (Basidiomycota) | [78] |

| Evolutionary complexity between rust fungi (Pucciniales) and their plant hosts | [79] |

| High-level classification of the Fungi and a tool for evolutionary ecological analyses | [18] |

| Taxonomy and phylogeny of operculate Discomycetes: Pezizomycetes | [33] |

| Molecular phylogeny of the Laboulbeniomycetes (Ascomycota) | [80] |

| Families in Botryosphaeriales | [81] |

| Natural classification and backbone tree for Graphostromataceae, Hypoxylaceae, Lopadostomataceae and Xylariaceae | [82] |

| Classification of the Dictyostelids | [83] |

| Revisiting Salisapiliaceae | [84] |

| Phylogenetic revision of Savoryellaceae | [85] |

| Notes, outline and divergence times of Basidiomycota | [86] |

| A new phylogenetic classification for the Leotiomycetes | [87] |

| Taxonomy and phylogeny of hyaline-spored Coelomycetes | [88] |

| Refined families of Sordariomycetes | [36] |

| Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa | [17] |

| The genera of Coelomycetes | [89] |

| A higher-rank classification for rust fungi, with notes on genera | [90] |

| Indian Pucciniales: taxonomic outline with important descriptive notes | [91] |

| Incorporating asexually reproducing fungi in the natural classification and notes for pleomorphic genera | [92] |

| How to publish a new fungal species, or name, version 3.0 | [93] |

These are studies on defining boundaries and providing the classification of different levels of fungal classification: Ascomycota [21,22,23], Diaporthales [24,25,26,27,28,29], Leotiomycetes [30], Magnaporthales [31], Orbiliaceae (Orbiliomycetes) [32], Discomycetes [33], Sordariomycetes [34,35,36], Sclerococcomycetidae [35,37], Xylariales [38], Xylariomycetidae [39] and Pezizomycetes [40]. Based on this, a brief outline of the classification of the kingdom Fungi (including fossil fungi, i.e., dispersed spores, mycelia, sporophores, mycorrhizas) given by Wijayawardene et al. [17] is provided herein tabulated form (Table 2).

Table 2.

A brief presentation on outline of fungi.

| Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genera |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphelidiomycota | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Ascomycota | 21 | 148 | 624 | 4511 |

| Basidiobolomycota | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Basidiomycota | 19 | 69 | 240 | 1521 |

| Blastocladiomycota | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| Calcarisporiellomycota | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Caulochytriomycota | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chytridiomycota | 9 | 13 | 52 | 97 |

| Entomophthoromycota | 2 | 2 | 5 | 20 |

| Entorrhizomycota | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Glomeromycota | 3 | 5 | 16 | 49 |

| Kickxellomycota | 6 | 6 | 7 | 61 |

| Monoblepharomycota | 3 | 3 | 7 | 9 |

| Mortierellomycota | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Mucoromycota | 3 | 3 | 17 | 62 |

| Neocallimastigomycota | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Olpidiomycota | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Rozellomycota | 2 | 7 | 41 | 162 |

| Zoopagomycota | 1 | 1 | 5 | 25 |

| Total | 79 | 270 | 1031 | 6561 |

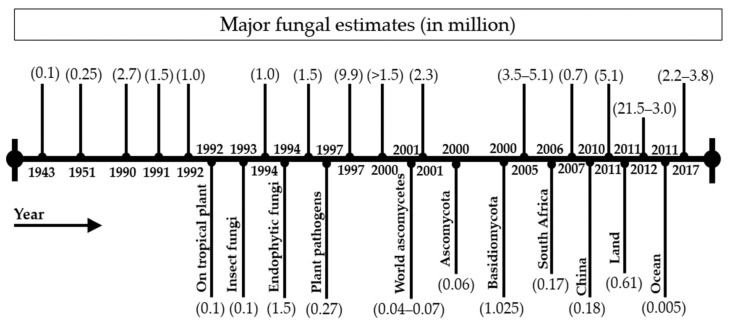

As one of the ancient and most diverse branches of the tree of life, kingdom Fungi contains an estimated 4–5 million species distributed all across the globe and plays vital roles in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems [94,95,96,97]. Of the total estimated number, so far, less than 2% of fungiis described [98]. Because of the vast diversity of these organisms and the addition of new fungi year by year, mycologists are facing major difficulties to define their boundaries accurately. The regular advancement in mycological techniques enables mycologists to describe new fungi all around the world every year based on decade evaluations. The description and addition of new species are estimated at 2626 from 2000 to 2012, while it was around 2326 between 1980 and 1999 [99,100,101]. This ongoing process of describing new fungi changes the overall estimate of fungi regularly. However, the suspense of undescribed fungi is still the same, which also added more uncertainty over defining their estimate exactly. In addition to natural habitats still waiting to explored, requirements of reassessment of dried herbarium samples based on molecular methods, along with morpho-taxonomy and lack of molecular facilities, still hinder mycologists in describing new fungi and attaining full estimate boundaries. Because of the importance of a total number of fungi estimates in their diversity and taxonomy (systematics, resources and classification) [12,102], many estimates have been put forward to elucidate the fungal species diversity in the world. Previous estimates of fungal diversity were based mainly on the plant-associated fungi [3]. Summarizing a comprehensive account of previous estimates of fungal diversity, we start with the estimate of about 100,000 presented by Bisby and Ainsworth [102]. Then, the number of fungi was estimated to be between 0.25–2.7 during the second half of the twentieth century. It was estimated (in millions) as follows: 0.25 [103], 2.7 [104], 1.5 [12,105,106], 1.0 [107,108,109], 1.3 [110], 0.27 [111] and 0.5 [112]. Similarly, the estimates on total described numbers of fungi during the twenty-first century were found to be between 2.3–5.1 million. The fungal estimate (1.5 million) provided by Hawksworth [12] has been most widely accepted for two decades. However, updated estimates of fungal species were provided in the current century as 3.5–5.1 [113], 5.1 [10], 2.2–3.8 [11]. The updated estimates were provided based on DNA based molecular techniques and next-generation sequencing. However, Hyde et al. [114] pointed out that more than 90% of the collected samples of fungi were neglected by mycological taxonomists around the globe. The total number of described fungi may be increased many times after processing these samples. The fungal estimates provided by various mycologists are presented in detail in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Estimations on the global number of fungal species.

In addition to estimating the total number of fungi, the global biodiversity of fungi has been extensively investigated for predicting their accurate estimate on earth. The number of advanced techniques, along with the number of numerical analytical methods, enabled researchers not only to identify and describe those fungi which are either not described, incorrectlyidentified or described incompletely, but also in understanding plant: fungus ratios [12,99], quantitative macroecological grid-based approaches [115,116,117], ecological scaling laws and methods based on environmental sequence data including plant: fungus ratios [10,113]. These studies on estimates proved fungi to be one of the largest groups of living organisms on this planet. An updated estimate of global fungal diversity is 2.2 to 3.8 million provided by Hawksworth and Lücking [11], however, also pointed out that this estimate would be a thousand times higher than the current highest estimate of 10 million species. A regression relationship between time and described fungal species by using Sigma State 3.5.SPSS (USA) was constructed and presented by Wu et al. [3]. With the help of this equation model, Wu et al. [3] presented the description rate of fungi. They indicated that 1.5 million fungal species, estimated by Hawksworth [12], could be described only by the year 2184, while the estimates of 2.2 and 3.8 million could be described by the years 2210 and 2245, respectively.

3. General Methods of Fungal Identification

The correct identification of fungi is one of the essential tools required for documenting fungi at the genus and species levels. There are several methods of fungal identification that differ in scope and content. However, the actual identification procedure is almost the same in each of the methods. Colonial morphological features, along with growth rate and microscopic observations, are some important criteria used to study different fungi. However, technological advancements have added more improved and sophisticated methods in this series. Generally, the fungal identification techniques are, broadly, three types, i.e., truly classical, culture and modern methods. While truly classical methods were based on the study of morphological features, the culture methods involved culture media technique. In modern methods, DNA-based techniques are utilized.

3.1. Classical Methods

Classical methods are most widely used in the documentation of fungi in relation to their identification and distribution on any substrate over a specific area. In general, these methods have been developed for studying any substratum or group of fungi [118]. Classical methods of fungal identification generally include incubation of substrata in moist chambers, direct sampling of fungal fruiting bodies, culturing of endophytes and particle plating. The following are basic types of classical methods.

3.1.1. Opportunistic Approach

In general, the opportunistic approach is one of the different types of classical methods used by mycologists to collect fruiting bodies of macromycetes. The availability of good condition fruiting bodies of macrofungi is generally a prerequisite for this efficient method of detecting new species or new records in a study area. The requirement of highly skilled mycologists for collection, processing and identification is a major limitation of this method, along with the risk of toxicity from these fungi [118].

3.1.2. Substrate Based Approach

The substrate-based protocols are another important approach used for the identification of fungi. The importance of these methods can be imagined because while some fungi fruit rather dependably, others fruit only sporadically. The substrate-based methods are mostly used for fungi that occur only on discrete, discontinuous or patchy resources, or are restricted to a particular host. The fungi forming sporocarps on soil, trees, large woody stumps, leaf litter, twigs and small branches are generally included in such methods. The fungi that form fruiting bodies on soil and ectomycorrhizal association with the trees provides a better understanding of their identification and diversity. The selection of a study plot is an important step that should be considered while using these methods [119,120]. In the case of fungi that form fruiting bodies on large woody debris, use of the log-based sampling method is generally preferred, keeping in view the substrate characteristics such as diameter, decay classes, upright, suspended, or grounded and host information [118,121]. Similarly, the use of a plot-based or band transect method is generally suggested in fungi, giving rise to fruiting bodies on fine debris (leaf litter, twigsand small branches). Here, size of the sample plot is generally kept in mind during the collection of fungal samples [119,120,122,123,124].

3.1.3. Moist Chambers Techniques

Moist Chambers Techniquesis one of the earliest and more effective methodsbeing utilized by mycologists in fungal taxonomy. This technique is used for fungi growing on leaves or small woody debris, such as ascomycetes, hyphomycetes and coelomycetes [124,125] and slime molds [126], and fungi growing on dung [127,128,129,130]. Here, the fungal samples collected from various substrates were processed for the production of fruiting bodies in a moist chamber for some duration and evaluated periodically for approximately 2 to 6 weeks.

3.1.4. Culture Media Technique

The use of culture media to inoculate fungi from the natural environment and incubate it to grow in controlled conditions for their isolation and identification is also one of the popular and widely used techniques. Numbers of artificial culture media are used here to provide growth substrate and required nutrition to inoculated fungi. Along with morphological characteristics, this technique proves quite useful in identifyinga fungal taxon. The easy and economic implication of this method has made it popular among mycologists. The numberof fungal groups such as endophytes, saprophytes and parasites—except obligate—can be isolated on various culture media from symptomless but fully expanded leaves, petioles, twigs, branches and roots, etc. [131]. Similarly, culturing of leaf washes is another culture media-based technique to assess the composition of spores on leaf surfaces. Commonly known as phylloplane fungi, these are considered to have good biocontrol potential [132,133]. Another culture based method known as the particle filtration method [134,135,136] is mainly meant for reducing the number of isolates derived from dormant spores in cultures taken from decomposing plant debris. Vegetatively active mycelia are generally cultured with the use of this method.

3.1.5. Advantages and Disadvantages of Truly Classical and Culture Based Methods

When we compare classical and culture based-methods with other advanced techniques, they still hold a key position in all the methods being utilized for assessing identification, diversity and distribution of fungi. Although these techniques are still in use globally, they also have certain disadvantages. In order tomake mycologistsaware of all aspects of basic methods (truly classical and culture based), a brief discussion on some of their important advantages/disadvantages is given below:

Advantages of Truly Classical and Culture Based Methods

These methods are still considered as the sources which can provide complete information on fungal communities of different areas with variable habitats. Because of the non-availability of DNA-based sequence data of all the fungi, it is the only criteria to determine basic information about individual species, such as geographic range, host relationships and ecological distribution.

The effects of abiotic variables (pH, soil nutrient content, weather-related variables) and biotic variables on fungi of the variable substrate and environmental conditions can be more easily studied by these methods.

As compared to an advanced one, these methods are more economical and can be executed with less specialized equipment.

Overall, the developing nations where adequate research funding is still a big challenge; these methods are important considerations for many investigators.

Disadvantages of Classical and Culture Based Methods

For the fungi which are unable to grow or produce reproductive structures on culture or hardly reproduce naturally, these methods are not suitable and become a major limitation in identifying, classifying and outlining fungi of a specific area.

The detailed procedure of sampling, culturing, isolation and identification methods are considerably more time consuming in comparison to more advanced techniques. The confirmation of new genera or species can be predicted more efficiently and accurately from the repeatedly sampled areas [120].

Due to the above-mentioned disadvantages, classical taxonomists are now considered to be endangered, as the interests of young researchers in classical methods is considerably reducing. If one willing to peruse a career in classical mycology, it takes a long duration of training. Similarly, to identify all of the collections based on the classical approach increases the time duration to find out final results. In molecular methods, technical expertise is quite enough to carry out research which also poses a major limitation to classical methods.

3.1.6. Advantages and Disadvantages of DNA Based Modern Methods

Besides having many advantages, the DNA-based methods also have some limitations, while modern methods are proven to be more efficient in the confirmation of new genera or species inlesser in time consumption. When classical methods are not able to study the fungi more specifically due to overlapping characters, i.e., a high degree of phenotypic plasticity, cryptic species and occurrence of different morphs for the same taxa [67,137,138], there are molecular methods which prove helpful to resolve such issues more accurately.

Like other methods, these methods also have certain disadvantages. The information we obtained with the help of this method is not so detailed as to be compared to classical methods; e.g., when we study basidiomata classically, we obtain a lot of information that we will never learn from DNA. Based on DNA-based techniques, numbers of new species are proposed, solely on the basis of unavailability of their sequences in the databases. Additionally, the submission of improper DNA sequences of many described fungi without proper editing is another drawback caused by molecular methods. Besides, poor taxon coverage in public depositories remains the principal impediment for successful species identification through molecular methods. The interpretation of BLAST results is regarded as the most important aspect in DNA-based methods of fungal identification. The availability of appropriate taxonomic and molecular experts in limited numbers is one of the major drawbacks of these methods. In addition, the contamination of DNA samples is another problem associated with molecular methods. Lastly, these methods are not cost effective in comparison to classical ones.

Keeping in view both advantages and disadvantages, it was found that mycological studies based on classical methods can perform better when combined with molecular analyses.

4. Assessment of Fungal Taxonomy and Diversity

Fungal taxonomy is the fundamental aspect of immense value utilized during mycological studies. The taxonomy of fungi based on morphological characters has been used for centuries and is still in use. Fungal taxonomy is generally required to identify and define existing and new fungi, andis ultimately useful in the assessment of their diversity and distribution. With the passage of time, the use of new and varied methods of fungal assessment came into existence which revolutionize the traditional methods based on morpho-taxonomy. However, both the methods based on morphology and molecular data care are still used equally and have their own levels of importance. It is primarily significant to use morphological-based methods and follow other approaches such as chemical, ecological, molecular or physiological analyses [139]. However, some technologies are expensive or inconvenient in terms ofuse in laboratories where the infrastructure is basic. Morphological analyses are, however, low-cost and results are acquired rapidly. These novel technologies have a relatively high cost. In cases wherethere is a limited quantity of a specimen or lack of sequence data, morphological data then play an important role in identification. In GenBank, there are many sequences which are wrongly named with errors. In such cases, detailed and extensive morphological characters help to resolve the taxonomy of them [140]. Therefore, morphology is still the most common technique to study fungi.

However, in recent times progress has driven taxonomic inferences towards DNA-based methods, and these procedures have parallel pros and cons. Modern mycotaxonomy has moved onward using morphological characters with a combination of chemotaxonomy, ecology, genetics, molecular biology and phylogeny [139,141,142,143,144,145]. The exploitation of sequence data for phylogenetic, biological, genetic and evolutionary analyses has offered a lot of understanding into the diversity and relationships of various fungal groups [71,139,146,147,148].

In DNA-based molecular characters, culture dependent and culture-independent methods are in practice nowadays to estimate fungal diversity. Culture-based approaches have been traditional, used to analyse microorganisms in indoor environments, including settled floor dust samples. However, this approach can be biased, for example, by microbial viability and/or culturability on a given nutrient medium. The advent of growth-independent molecular biology-based techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing, has circumvented these difficulties. However, few studies have directly compared culture-based morphological identification methods with culture-independent DNA sequencing-based approaches. For example, a previous study compared the presence or absence of fungal species detected by a culture-based morphological identification method and a culture independent DNA sequencing method [149]. However, only a qualitative comparison was conducted between these two different approaches and a quantitative comparison was not conducted (Table 3 and Table 4). A detailed account of general tools and repositories generally used in DNA-based identification of fungi are presented in Table 5.

Table 3.

An overview on DNA-based methods of fungal samples analyses.

| Global Fungi Study ID | Substrate | Samples | Method | Sequencing Platform | ITS2 Sequences | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartmann_2012_B1A3 | – | 6 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 2155088 | [150] |

| Ihrmark_2012_3AE5 | Soil, wood, wheat roots and hay | 36 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 414896 | [151] |

| Davey_2012_6F6A | Shoots of Hylocomium splendens, Pleurozium schreberi, and Polytrichum commune | 301 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 296964 | [152] |

| Peay_2013_74BB | Soil | 36 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 86677 | [153] |

| Davey_2013_7683 | Shoots of Dicranum scoparium, Hylocomium splendens, Pleurozium schreberi and Polytrichum commune | 454-pyrosequencing | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 313084 | [154] |

| Talbot_2014_A187 | Soil | 555 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 16977 | [155] |

| Tedersoo_2014_B9DD | Soil | 360 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 1979803 | [156] |

| Kadowaki_2014_B85B | Soil | 46 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 66067 | [157] |

| Geml_2014_2936 | Soil | 10 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 285031 | [158] |

| Davey_2014_2252 | Shoots of Hylocomium splendens | 251 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 639746 | [159] |

| McHugh_2015_CAE1 | Soil | 20 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 594424 | [160] |

| DeBeeck_2014_14DC | Soil | 20 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 32778 | [161] |

| Yamamoto_2014_C3F7 | Seedlings of Quercus sp. | 431 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 59021 | [162] |

| Walker_2014_22C1 | Soil | 24 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 34267 | [163] |

| Veach_2015_7FDE | Soil | 91 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 579967 | [164] |

| Zhang_2015_A52F | Seven lichens speciesViz. Cetrariella delisei, Cladonia borealis, C. arbuscula, C. pocillum, Flavocetraria nivalis, Ochrolechia frigida and Peltigera canina | 22 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 11087 | [165] |

| Elliott_2015_7CC2 | Soil | 16 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 3896 | [166] |

| Geml_2015_1A45 | Soil | 10 | Culture independent | Ion Torrent | 1098472 | [167] |

| Hoppe_2015_BE27 | Wood | 48 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 121459 | [168] |

| Jarvis_2015_B613 | Roots of Pinus sylvestris | 32 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 112333 | [169] |

| Chaput_2015_41F7 | Soil | 4 | Culture independent | Tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing | 1197 | [170] |

| van_der_Wal_2015_1114 | Sawdust from sapwood and heartwood of Quercus robur, Rubus fruticosus, Sorbus aucuparia, Betula pendula, Pteridium aquilinum and Amelanchier lamarckii |

42 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 543801 | [171] |

| Clemmensen_2015_B0AE | Soil | 466 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing GL FLX Titanium system | 592836 | [172] |

| Gao_2015_1CEF | Soil | 24 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing GL FLX Titanium system | 93683 | [173] |

| Liu_2015_6174 | Soil | 26 | Culture independent | Roche FLX 454- pyrosequencing | 53978 | [174] |

| Oja_2015_88D4 |

Cypripedium calceolus (subfamily Cypripedioideae), Neottia ovata

(Epidendroideae) and Orchis militaris (Orchidoideae) and Soil |

158 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 63045 | [175] |

| Goldmann_2015_EA26 | Soil | 48 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencer | 140966 | [176] |

| Tedersoo_2015_ED81 | Soil | 11 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 261751 | [177] |

| Rime_2015_89DE | Soil | 36 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing GL FLX Titanium system | 227118 | [178] |

| Sterkenburg_2015_5E14 | Soil | 56 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 350560 | [179] |

| Stursova_2016_D385 | Soil | 96 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 452546 | [180] |

| Semenova_2016_576B | Soil | 10 | Culture independent | Ion Torrent sequencing | 1007509 | [181] |

| Santalahti_2016_74FC | Soil | 117 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 739877 | [182] |

| Rime_2016_E0E4 | Soils and sediments | 2 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 35937 | [183] |

| RoyBolduc_2016_E50C | Root and soil | 63 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 248325 | [184] |

| RoyBolduc_2016_F11B | Soil | 77 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 280272 | [185] |

| Tedersoo_2016_TDEF | Soil | 136 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 788372 | [186] |

| UOBC_2016_5CA6 | Soil | 655 | Culture independent | Illumina HiSeq | 7138323 | [187] |

| Urbina_2016_CE8E | Soil | 21 | Culture independent | Ion Torrent sequencing | 564332 | [188] |

| Valverde_2016_5E5C | Soil from the rhizosphere of Welwitschia mirabilis | 8 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 2677 | [189] |

| Nacke_2016_8F49 | Soil from the rhizosphere Fagus sylvatica and Picea abies | 160 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 386432 | [190] |

| Newsham_2016_191B | Soil | 29 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 509483 | [191] |

| Nguyen_2016_D8E8 | Shoots of Picea abies, Abies alba, Fagus sylvatica, Acer pseudoplatanus, Fraxinus excelsior, Quercus robur, Pinus sylvestris, Betula pendula, Carpinus betulus and Quercus robur | 221 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 63853 | [192] |

| Goldmann_2016_0757 | Root and soil samples from beech-dominated plots | 29 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 85867 | [193] |

| Bahram_2016_7246 | Soil | 123 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 213249 | [194] |

| Gehring_2016_E395 | Roots and root-associated (rhizosphere) soil of sagebrush, cheatgrass, and rice grass plants | 60 | - | - | 1161117 | [195] |

| Gourmelon_2016_9281 | Soil | 32 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 91814 | [196] |

| Bissett_AAAA_2016 | Soil | 2061 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 50810033 | [197] |

| Cox_2016_EDC5 | Soil | 135 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 886200 | [198] |

| Oh_2016_DEBA | Soil | 12 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 98376 | [199] |

| Frey_2016_5D5C | Soil | 12 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq v3 | 500999 | [200] |

| Gannes_2016_5E98 | Soil | 23 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq system | 218946 | [201] |

| Li_2016_1EBC | Soil | 21 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq system | 129184 | [202] |

| Kielak_2016_1110 | Wood of Pinus sylvestris | 75 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 1281356 | [203] |

| Ji_2016_C06E | Soil | 13 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 277 | [204] |

| Baldrian_2016_DE02 | Sawdust | 118 | Culture independent | llumina MiSeq | 1205580 | [205] |

| Barnes_2016_0042 | Roots of Cinchona calisaya | 21 | Culture independent | llumina MiSeq | 239387 | [206] |

| Porter_2016_CD8D | Soil | 2 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 20123 | [207] |

| Zhou_2016_A8F1 | Soil | 126 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 3542416 | [208] |

| Zhang_2016_1DA0 | Soil | 13 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 2362 | [209] |

| Wang_2016_6223 | Roots, stems, and sprouts of rice plant | 1 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 1850 | [210] |

| Zifcakova_2016_4C03 | Soil | 24 | Culture independent | ILLUMINA HISEQ2000 |

123869 | [211] |

| VanDerWal_2016_4C9C | Sawdust from sapwood and heartwood | 130 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 1215932 | [212] |

| Varenius_2017_BCFB | Soil | 517 | Culture independent | PacBio RSII platform by SciLifeLab | 186474 | [213] |

| van_der_Wal_2017_2D0D | Sawdust samples of Larix stumps, and Quercus stumps | 88 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 877425 | [214] |

| Wang_2017_7E18 | Soil | 6 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 53737 | [215] |

| van_der_Wal_2017_3070 | Soil | 135 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 1572834 | [216] |

| Vasutova_2017_3070 | Soil | 28 | Culture independent | GS Junior sequencer |

9370 | [217] |

| Vaz_2017_C16E | Woody debris | 2 | Culture independent | Personal Genome Machine | 11817 | [218] |

| Yang_2017_2AFC | Soil | 180 | Culture independent | llumina MiSeq platform PE250 | 12688168 | [219] |

| Wicaksono_2017_3B9E | Root samples of Alnus acuminata | 24 | Culture independent | Ion Torrent | 3596531 | [220] |

| Yang_2017_EB1D | Soil | 26 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq platform PE250 |

1450233 | [221] |

| Zhang_2017_02C2 | Plant litter and soil | 54 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 2904476 | [222] |

| Zhang_2017_F933 | Peat soil | 9 | Culture independent | Illumina HiSeq2000 | 320199 | [223] |

| Purahong_2017_8EFD | Wood sample | 116 | Culture independent | Genome Sequencer 454-FLX System | 299831 | [224] |

| Poosakkannu_2017_B342 | Bulk soil, rhizosphere soil, and D. flexuosa Leaf | 43 | Culture independent | IonTorrent | 259743 | [225] |

| Bergottini_2017_02C2 | Roots of Ilex paraguariensis | 11 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 189048 | [226] |

| Dean_2017_F5A5 | Roots of Glycine max (soybean) and Thlaspi arvense | 12 | Culture independent | 454-FLX titanium | 12596 | [227] |

| Fernandez_Martinez_2017_14C3 | Soil | 11 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 138524 | [228] |

| Ge_2017_4DC8 | Roots of Quercus nigra, Q. virginiana, Q. laevis, Carya cf. glabra, Carya cf. tomentosa as well as several Carya and Quercus spp. | 9 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 44 | [229] |

| Gomes_2017_2AFC | Roots of Thismia sp. | 61 | Culture independent | Ion Torrent | 4067438 | [230] |

| Almario_2017_2082 | Root and rhizosphere of Arabis alpina | 26 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 805679 | [231] |

| Anthony_2017_647F | Soil | 142 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 12453259 | [232] |

| Grau_2017_E29A | Soil | 27 | Culture independent | Ion Torrent | 960177 | [233] |

| Hiiesalu_2017_E29A | Soil | 1 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 4616 | [234] |

| Nguyen_2017_6F2C | Leaf samples of Betula pendula | 20 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 1318 | [235] |

| Kolarikova_2017_EB1D | Roots of Salix caprea and Betula pendula | 24 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 47543 | [236] |

| Kyaschenko_2017_89D4 | Soil | 30 | Culture independent | PacBio sequencing | 64010 | [237] |

| Oja_2017_AD29 | Roots and rhizosphere soil of | 333 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 446296 | [238] |

| Miura_2017_2BE5 | Leaves and berries of grapes | 36 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 2250530 | [239] |

| Oono_2017_B342 | Needles of Pinus taeda | 143 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 9755183 | [240] |

| Kamutando_2017_6F2C | Soil | 3 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 4 | [241] |

| Shen_2017_C7F4 | Soil | 1 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 1 | [242] |

| Smith_2017_2AFC | Root of Dicymbe corymbosa | 8 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 94 | [243] |

| Tian_2017_F933 | Soil | 3 | Culture independent | 454-GS FLX+pyrosequencing machine | 25001 | [244] |

| Tu_2017_BCFB | Soil | 60 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 696557 | [245] |

| Sharma_Poudyal_2017_F933 | Soil | 53 | Culture independent | 454-FLX titanium | 7680 | [246] |

| Cross_2017_2AFC | Leaflet, petiole upper and petiole base tissues of ash leaves of Fraxinus excelsior (common ash) | 27 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 171094 | [247] |

| Kazartsev_2018_1115 | Bark of Picea abies | 20 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 22918 | [248] |

| Bickford_2018_2EE0 | Roots of Phragmites spp. | 3 | Culture independent | PacBio-RS II | 66439 | [249] |

| Cline_2018_0BCC | Wood of Betula papyrifera | 15 | Culture independent | 454-FLX titanium | 660 | [250] |

| Cregger_2018_added | Roots, stems, and leaves of Populus deltoides and the Populus trichocarpa × deltoides hybrid | 290 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 14767409 | [251] |

| Marasco_2018_DBE1 | Rhizosheath-root system of Stipagrostis sabulicola, S. seelyae and Cladoraphis spinosa | 49 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 4694085 | [252] |

| Glynou_2018_445A | Roots of nonmycorrhizal Microthlaspi spp. | 5 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 7 | [253] |

| Montagna_2018_E316 | Soil | 24 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 2475767 | [254] |

| Schlegel_2018_A231 | Leaves of Fraxinus spp. and Acer pseudoplatanus | 353 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 24198214 | [255] |

| SchneiderMaunoury_2018_51AB | Different plant species | 78 | Culture independent | Ion Torrent | 352332 | [256] |

| Schon_2018_01F4 | Soil | 18 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 235709 | [257] |

| Rasmussen_2018_C8E6 | Root samples | 228 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 428044 | [258] |

| Rogers_2018_147F | Hemlock stems | 6 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 675067 | [259] |

| Purahong_2018_14C0 | Deadwood logs | 297 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 2034928 | [260] |

| Qian_2018_2B1E | Leaves of Mussaenda shikokiana | 20 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 449179 | [261] |

| Park_2018_569C | Calanthe species: C. aristulifera, C. bicolor, C. discolor, C. insularis and C. striata | 12 | Culture independent | 454-GS FLX +System | 65867 | [262] |

| Mirmajlessi_2018_765D | Soil | 40 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 1077125 | [263] |

| Purahong_2018_9F2E | Wood samples | 96 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 656682 | [264] |

| Si_2018_53B6 | Soil | 27 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 692169 | [265] |

| Saitta_2018_51C8 | Soil | 16 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 4923667 | [266] |

| Santalahti_2018_3794 | Soil | 38 | Culture independent | 454-pyrosequencing | 218387 | [267] |

| Sukdeo_2018_1DF4 | Soil | 126 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 32336646 | [268] |

| Zhu_2018_1E38 | Soil | 12 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 1031479 | [269] |

| Zhang_2018_F81F | Soil | 106 | Culture independent | Illumina HiSeq | 1673070 | [270] |

| Zhang_2018_491A | Bare sand, algal crusts, lichen crusts, and moss crusts | 17 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 442056 | [271] |

| Sun_2018_1B01 | Soil | 36 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 1188520 | [272] |

| Weissbecker_2019_6A75 | Soil | 394 | Culture independent | GS-FLX + 454 pyrosequencer | 1109208 | [273] |

| Purahong_AD_2019 | Wood chips of rotted heartwood deadwood from C. carlesii | 3 | Culture independent | PacBio RS II system | 22886 | [274] |

| Egidi_AD_2019 | Soil | 161 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 14131987 | [275] |

| Froeslev_2019_CA74 | Soil | 276 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 6114124 | [276] |

| Ogwu_2019_38FE | Soil | 13 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 724483 | [277] |

| Ovaskainen_2019_air | Soil particles, spores, pollen, bacteria, and small insects | 75 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 935812 | [278] |

| Qian_2019_9691 | Leaves and soil | 30 | Culture independent | Illumina HiSeq | 2133292 | [279] |

| Ramirez_2019_D0B2 | Soil | 810 | Culture independent | Illumina Miseq | 6555903 | [280] |

| Pellitier_2019_82BC | Bark of black oak (Quercus velutina), white oak (Q. alba), red pine (Pinus resinosa), eastern white pine (P. strobus) and red maple (Acer rubrum) | 15 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 10649956 | [281] |

| Semenova-Nelsen_2019_add | Litter and the uppermost soil | 121 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 3205748 | [282] |

| Sheng_2019_66AC | Soil | 16 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 447840 | [283] |

| Shigyo_2019_5B19 | Soil | 144 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 4353704 | [284] |

| Schroter_2019_1B64 | Fine roots and soil | 3 | Culture independent | Roche GS-FLX+ pyrosequencer | 144 | [285] |

| Singh_2019_EA7F | Fine roots and soil | 96 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 3138303 | [286] |

| Song_2019_ad2 | Soil | 46 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 920391 | [287] |

| U’Ren_2019_add | Fresh, photosynthetic tissues of a diverse range of plants and lichens |

486 | Culture-based sampling and culture-independent | Illumina MiSeq | 5671834 | [288] |

| Unuk_2019_567A | Fine roots and soil | 30 | Culture independent | Ilumina MiSeq | 470786 | [289] |

| Araya_2019_add | Soil | 36 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 8083471 | [290] |

| Alvarez-Garrido_2019_add | Root tips from A. pinsapo trees following the trunk to the superficial secondary roots | 76 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 1795423 | [291] |

| Wei_2019_3796 | Soil | 1 | Culture independent | Illumina HiSeq | 18 | [292] |

| Pan_2020_addZ | Soil from the rhizosphere of potato | 1 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 2 | [293] |

| Detheridge_2020_Z | Soil | 70 | Culture independent | 1832454 | [294] | |

| Li_2020_AS | Soil | 19 | Culture independent | Illumina MiSeq | 116660 | [295] |

Table 4.

An overview on culture dependentand culture independent analyses of fungal samples with respect to location, source, sequencing, observation method and target gene.

| Location | Source | Sequencing | Method | Target Gene | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woods Hole Harbor Massachusetts | Wood | – | Culture dependent | Direct observation | – | – | [296] |

| Atlantic Ocean | Water | – | Culture dependent | Incubation of sample and direct observation | – | – | [297] |

| Rumanian coast of the Black Sea | Calcareous substances | – | Culture dependent | Incubation of sample and direct observation | – | – | [298] |

| Iceland-Faroe ridge | Water | – | Culture dependent | Incubation of sample and direct observation | – | – | [299] |

| Bahamas | Wood | – | Culture dependent | Incubation of sample and direct observation | – | – | [300] |

| Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea | Sediment | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | – | [301] | |

| Northwest Pacific Ocean (Sagami Bay and Suruga Bay; Palau-Yap Trench and Mariana Trench) | Sediments | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | ITS and 5.8S | [302] |

| Guaymas Basin hydrothermal vent | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU | [303] |

| Mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal area | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU | [304] |

| Chagos Trench, Indian Ocean | Sediment | – | Culture dependent/Direct detection | Culture media | – | – | [305] |

| Peru Margin | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | SSU | [306] |

| Central Indian Basin | Sediment | – | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | – | [307] |

| Kuroshima Knoll in Okinawa | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | Clone library | SSU | [308] | |

| Central Indian Basin | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | – | [309] |

| Different locations | Water and sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | Clone library | SSU | [310] | |

| South China Sea | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | – | Clone library | ITS | [311] |

| Lost City | Water | Sanger | Culture dependent | – | Clone library | SSU | [312] |

| Central Indian Basin | Sediment | Direct detection | – | – | – | [313] | |

| Vailulu’u is an active submarine volcano at the eastern end of the Samoan volcanic chain | Water | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | ITS | [314] |

| Vanuatu archipelago | Deepsea water, wood and debris | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | SSU and LSU | [315] |

| East Pacific Rise, Mid-Atlantic Ridge and Lucky Strike | Deepsea hydrothermal ecosystem | Sanger | Culture dependent/Cultureindependent | Culture media | Clone library | SSU | [316] |

| Southwest Pacific | Deepsea hydrothermal ecosystems | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | SSU | [317] |

| Different locations | Deep-sea hydrothermal ecosystems | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | LSU | [318] |

| Japanese islands, including a sample from the deepest ocean depth, the Mariana Trench | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU, ITS and LSU | [319] |

| Southern East Pacific Rise | Water and bivalves | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU | [320] |

| Central Indian Basin | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | Full ITS and SSU | [321] | |

| Southern Indian Ocean | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU | [322] |

| Peru Margin and the Peru Trench | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU | [323] |

| Puerto Rico Trench | Water | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU | [324] |

| Sagami-Bay | Deep-sea methane cold-seep sediments | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU | [325] |

| Marmara Sea | Sediment | Sanger and 454-pyrosequencing | Culture independent | – | Clone library | SSU | [326] |

| Central Indian Basin - Several stations | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | Full ITS and SSU | [327] |

| Central Indian Basin - Several stations | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent/Culture independent | Culture media | Clone library | SSU (Fungal isolates)/ITS (DNA sediment) | [328] |

| Central Indian Basin - Several stations | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent cloning | – | Clone library | Full ITS and SSU | [328] |

| Alaminos Canyon 601 methane seep in the Gulf of Mexico | Methane seeps sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | ITS and LSU | [329] |

| The area surrounding the DWH oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico | Deep-sea samples from the area surrounding the Deepwater Horizon oil spill | 454-pyrosequencing | Culture independent | – | Shotgun | assA and bssA | [330] |

| Hydrate Ridge, Peru Margin, Eastern Equatorial Pacific | Sediment | Sanger and 454-pyrosequencing | Culture independent | – | TRFLP/Metatranscriptomics | SSU | [331] |

| Peru Margin | Sediment | Illumina | Culture independent | Metatranscriptomics | – | [331] | |

| South China Sea | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | Full ITS | [332] |

| Mediterranean Sea | Hypsersaline anoxic basin | 454-pyrosequencing | Culture independent | – | – | SSU | [333] |

| Canterbury basin, on the eastern margin of the South Island of New Zealand | Sediment Ocean Drilling Program | 454-pyrosequencing | Culture independent | – | Metatranscriptomics | ITS and SSU | [334] |

| The Pacific Ocean and MarianaTrench | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | ITS | [335] |

| East Indian Ocean | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent/Culture independent | Culture media | Clone library | ITS | [336] |

| Canterbury basin, on the eastern margin of the South Island of New Zealand | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | SSU, ITS and LSU | [337] |

| Urania, Discovery and L’Atalante basins | Hypsersaline anoxic basin | Illumina | Culture independent | – | Metatranscriptomics | – | [338] |

| Several locations around the world/The ICoMM data set | Pelagic and benthic samples | 454-pyrosequencing | Culture independent | – | – | SSU | [339] |

| The Pacific Ocean and MarianaTrench | Sediment | Sanger | Culture independent | – | Clone library | ITS, SSU and LSU | [340] |

| Okinawa | Sediment | Illumina | Culture independent | – | – | ITS | [341] |

| Southwest Indian Ridge (SWIR) | Sediment and Deepsea hydrothermal ecosystems |

Sanger and Illumina | Culture dependent/Culture independent | With and without Culture media | – | ITS | [342] |

| Continental margin of Peru | Sediment | Illumina | Culture independent | – | – | SSU | [343] |

| North Atlantic and Arctic Basin | Marine snow | Culture independent | – | CARD-FISH | – | [344] | |

| Northern Chile | Water | Sanger | Culture dependent | – | – | Full ITS | [345] |

| The Sao Paulo Plateau | Asphalt seeps | Ion Torrent | Culture independent | – | – | ITS | [346] |

| Peru Margin | Sediment | Illumina | Culture independent | – | Metatranscriptomics | [347] | |

| East Pacific | Sediment | Sanger | Culturedependent | Culture media | Full ITS | [348] | |

| The Ionian Sea (Central Mediterranean Sea) | Sediment | Illumina | Culture independent | – | FISH | ITS | [349] |

| South-central western Pacific Ocean | Water | Illumina | Culture independent | – | – | SSU | [350] |

| Challenger deep | Water | Illumina | Culture independent | – | – | ITS | [351] |

| Mexican Exclusive Economic Zone-Gulf of Mexico | Sediment | Illumina | Culture independent | – | – | ITS | [352] |

| Yap Trench | Sediment | Sanger and Illumina | Culture dependent/Culture independent | – | – | ITS | [353] |

| Mexican Exclusive Economic Zone-Gulf of Mexico | Sediment | Sanger | Culture dependent | Culture media | – | Full ITS and tub | [354] |

Table 5.

Databases and tools for sequence-based classification and identification.

| General Identification Tools and Data Repositories | |

|---|---|

| BOLD | http://www.boldsystems.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Westerdijk Fungal BiodiversityInstitute | https://wi.knaw.nl/page/Collection (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| CIPRES | https://www.phylo.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Dryad | http://datadryad.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| FUSARIUM-ID | http://isolate.fusariumdb.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| One Stop Shop Fungi | http://onestopshopfungi.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| GreenGenes | http://greengenes.lbl.gov/cgi-bin/nph-index.cgi (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| MaarjAM | http://maarjam.botany.ut.ee/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Mothur | http://www.mothur.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Naïve Bayesian Classifier | http://aem.asm.org/content/73/16/5261.short?rss=1&ssource=mfc (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Open Tree of Life |

http://www.opentreeoflife.org/ QIIME http://qiime.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| PHYMYCO database | http://phymycodb.genouest.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| RefSeq Targeted Loci | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/targetedloci/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) | http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Silva | http://www.arb-silva.de/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| TreeBASE | http://treebase.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| TrichoBLAST | http://www.isth.info/tools/blast/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| UNITE | http://unite.ut.ee/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| United Kingdom National Culture Collection | http://www.ukncc.co.uk/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Data standards | |

| BIOM | http://biom-format.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| MIMARKS | http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v29/n5/full/nbt/1823.html (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Darwin | Core http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Genomics databases and tools | |

| AFTOL | http://aftol.umn.edu/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| 1000 Fungal Genomes Project (1KFG) | http://1000.fungalgenomes.org/home/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| FungiDB | http://fungidb.org/fungidb/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| GEBA | http://jgi.doe.gov/our-science/science-programs/microbial-genomics/phylogenetic-diversity/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| MycoCosm | http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/programs/fungi/index.jsf (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Functional database | |

| FUNGuild | http://github.com/UMNFuN/FUNGuild (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Nomenclature and nomenclatural databases and organizations | |

| Catalogue of Life (COL) | http://www.catalogueoflife.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| EPPO-Q-bank | http://qbank.eppo.int/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Faces of Fungi | http://www.facesoffungi.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Index Fungorum | http://www.indexfungorum.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| International code of nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICNAFP) | http://www.iapt-taxon.org/nomen/main.php (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| International Commission on the Taxonomy of Fungi (ICTF) | http://www.fungaltaxonomy.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| List of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (LPSN) | http://www.bacterio.net/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| MycoBank | http://www.mycobank.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Outline of fungi | http://www.outlineoffungi.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| Biodiversity collections databases | |

| Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) | http://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| iDigBio | http://www.idigbio.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| MycoPortal | http://mycoportal.org/portal/index.php (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

| World Federation of Culture Collections (WFCC) | http://www.wfcc.info/ (accessed on 6 November 2021) |

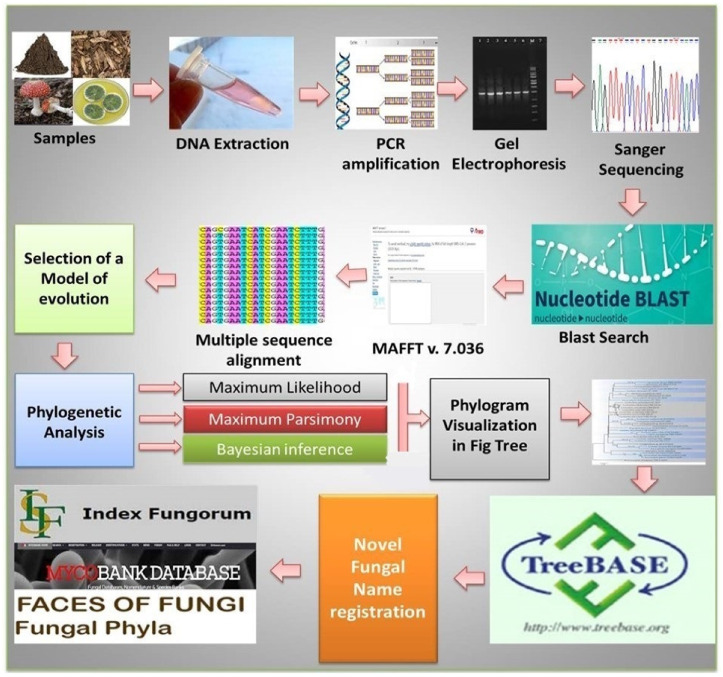

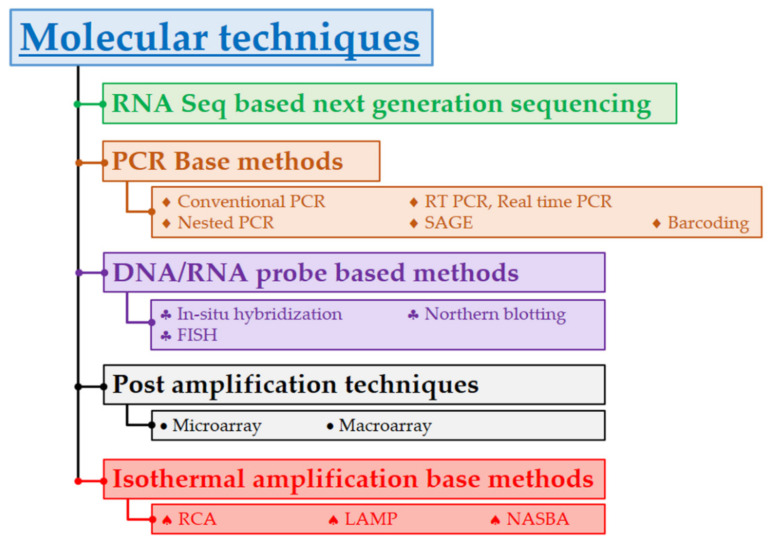

Likewise, a listing of Sequence Independent methodsand High-throughput sequencing platforms are summarized in Table 6. The pictorial overview on different molecular techniques, as well as the general protocol of culture dependent and culture independent DNA-based molecular techniques used in fungal sample analyses, is also present here (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Table 6.

Sequence Independent methods and High-throughput sequencing platforms.

| Sequencing Independent Methods | High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms |

|---|---|

| ARDRA (Amplified Ribosomal DNA Restriction Analysis) | 454 Pyrosequencing (second-generation platform) |

| ARISA (Amplified Intergeneric Spacer Analysis) | Illumina MiSeq sequencing (second-generation) |

| DGGE (Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis) | Ion Torrent PGM and GeneStudio |

| FISH (Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization) | PacBio RSII and Sequel (This third-generation HTS platform) |

| LAMP (Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification) | Oxford Nanopore MinION, GridION and PrometION (third-generation) |

| MT-PCR (Multiplexed tandem PCR) | – |

| RCA (Rolling Circle Amplification) | – |

| RDBH (Reverse Dot Blot Hybridization) | – |

| RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism) | – |

| SSCP (Single-Strand Conformation Polymorphism) | – |

| TGGE (Thermal Gradient Gel Electrophoresis) | – |

| TRFLP (Terminal Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism) | – |

Figure 4.

An overview of DNA-based molecular techniques used in fungal sample analyses.

Figure 5.

Different molecular techniques used in DNA-based analyses of different fungi.

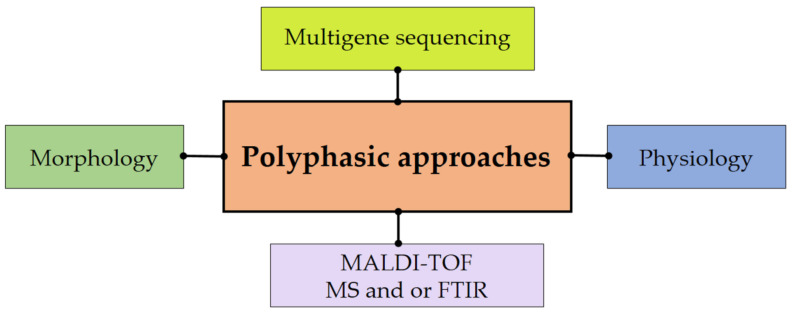

5. Polyphasic Identification

The correct identification of species is a crucial goal in taxonomy. Information about each identified fungal species (e.g., biochemical properties, ecological roles, morphological description, physiological and societal risks or benefits) is a vital component in this process. Identification is a never-ending and apparently lengthy process with several amendments of the taxonomic outlines.

The polyphasic approaches comprise the use of varied procedures based on the grouping of scientific information. Various approaches such as biochemical, micro-and macro-morphology, and molecular biology studies are applied (Figure 6). Microbial spectral analysis based on mass spectrometry (particularly matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry//MALDI-TOF MS) has been developed and used as an important step in the polyphasic identification of fungi [355].

Figure 6.

Modern polyphasic methodology of fungal identification.

A polyphasic method based on ecology, morphology and molecular data based techniques (multigene sequencing) is highly advocated to identify the fungal species precisely. Phylogenetic analyses have been comprehensively used to interpret species limitations in several fungal genera [356,357] shown in Table 7. There are several fungal species that have not been correctly identified. However, there are numerous boundaries associated with phylogenetic analyses for species identification [358,359]. There is an absence of molecular data for many fungal species, including reference sequences, and few species only have ITS sequences, which obstructs molecular-based techniques [360,361]. Moreover, phylogenetic analyses do not account for hybridization events and horizontal gene transfer [359]. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region has been accepted as a nearly universal barcode for fungi owing to the ease of amplification and its wide utility across the kingdom; however, it can often only be used for placement of taxa up to the genus level [361,362]. There is also a lack of ex-type or authenticated sequences for several pathogenic genera [355]. The identification of species boundaries is, thus, important to better understand genetic variation in nature to develop sustainable control measures [363].

Table 7.

An overview of polyphasic approach on analyses of plant pathogenic fungi.

| Family | Genus | Genetic Marker for Genus Level | Genetic Markers for Species Level | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleosporaceae | Alternaria | LSU and SSU | ITS, GAPDH, rpb2 and tef1-α | [365,366,367,368] |

| Physalacriaceae | Armillaria | ITS | ITS, IGS1 and tef1-α | [369,370] |

| Botryosphaeriaceae | Barriopsis | ITS | tef1-α | [371,372] |

| Didymellaceae | Ascochyta, Boeremia, Didymella, Epicoccum, Phoma | LSU and ITS | rpb2, tub2 and tef1-α | [373,374,375,376] |

| Pleosporaceae | Bipolaris | GPDH | ITS, tef1-α and GPDH | [377] |

| Botryosphaeriaceae | Botryosphaeria | LSU, SSU and ITS | tub and tef1-α | [378,379] |

| Nectriaceae | Calonectria, Cylindrocladium | LSU and ITS | ITS, tub, tef1-α, cmdA, His3 and ACT | [380,381,382,383,384] |

| Mycosphaerellaceae | Cercospora | LSU and ITS | ITS, tef1-α, ACT, CAL, HIS, tub2, rpb2 and GAPDH | [385,386,387,388,389] |

| Cryptobasidiaceae | Clinoconidium | ITS and LSU | ITS and LSU | [390,391,392] |

| Choanephoraceae | Choanephora | ITS | ITS | [393] |

| Glomerellaceae | Colletotrichum |

GPDH, tub; ApMat-Intergenic region of apn2 and MAT1-2-1 genes can resolve within the C. gloeosporioides complex |

GS-glutamine synthetase-CHS-1, HIS3-Histone3 and ACT-Actin-Placement within the genus and also some species-level delineation | [394,395,396] |

| Schizoparmaceae | Coniella | LSU and ITS | ITS, LSU, tef1-α, rpb2 and His3 | [397,398,399,400,401] |

| Pleosporaceae | Curvularia | LSU | GDPH | [402,403,404] |

| Nectriaceae | Cylindrocladiella | ITS and LSU | HIS, tef1-α and tub2 | [405,406] |

| Cyphellophoraceae | Cyphellophora | LSU and SSU | ITS, LSU, tub2 and rpb1 | [407,408] |

| Botryosphaeriaceae | Diplodia | ITS, tef1-α and tub | LSU and SSU | [378,409] |

| Botryosphaeriaceae | Dothiorella | tub | tef1-α | [378,410] |

| Elsinoaceae | Elsinoe | ITS | rpb2 and tef1-α | [411,412] |

| Xylariaceae | Entoleuca | LSU and ITS | rpb2 and tub2 | [413] |

| Entylomataceae | Entyloma | ITS | ITS | [80,414,415] |

| Corticiaceae | Erythricium | LSU | ITS | [416] |

| Botryosphaeriaceae | Eutiarosporella | LSU and SSU | ITS and LSU | [372,417,418] |

| Hymenochaetaceae | Fomitiporia | ITS | LSU, ITS, tef1-α and rpb2 | [419,420,421,422,423] |

| Hymenochataceae | Fulvifomes | LSU | ITS, tef1-α and rpb2 | [424,425] |

| Nectriaceae | Fusarium | ATP citrate lyase (Acl1), tef1-α and ITS | Calmodulin encoding gene (CmdA), tub2, tef1-α, rpb1 and rpb2 | [426,427,428] |

| Ganodermataceae | Ganoderma | ITS | rpb2 and tef1-α | [429,430,431,432,433,434,435] |

| Erysiphaceae | Golovinomyces | ITS and LSU | ITS and LSU, IGS, rpb2 and CHS | [436,437,438,439,440] |

| Bondarzewiaceae | Heterobasidion | LSU | rpb1 and rpb2 | [441] |

| Nectriaceae | Ilyonectria | ITS, LSU, tef1-α and tub2 | tef1-α, tub2 and His3 | [442,443,444,445,446] |

| Corticiaceae | Laetisaria, Limonomyces | LSU | ITS | [447,448] |

| Botryosphaeriaceae | Lasiodiplodia | SSU and LSU | ITS, tef1-α and tub2 | [378,449] |

| Botryosphaeriaceae | Macrophomina | LSU and SSU | ITS, tef1-α, ACT, CmdA and tub2 | [378,450] |

| Medeolariaceae | Medeolaria | ITS | ITS | [451] |

| Caloscyphaceae | Caloscypha | SSU and LSU | SSU, LSU | [452] |

| Meliolaceae | Meliola | LSU and SSU | ITS | [453,454] |

| Mucoraceae | Mucor | LSU and SSU | ITS and rpb1 | [455,456,457,458,459] |

| Erysiphaceae | Neoerysiphe | ITS and LSU | ITS | [460,461,462] |

| Dermataceae | Neofabraea | LSU | ITS, LSU, rpb2 and tub2 | [463] |

| Botryosphaeriaceae | Neofusicoccum | SSU, LSU | ITS, tef1-α, tub2 and rpb2 | [464] |

| Nectriaceae | Neonectria | LSU, ITS, tef1-α and tub2 | ITS, tef1-α and tub2 | [446] |

| Sporocadaceae | Neopestalotiopsis | LSU | ITS, tub2 and tef1-α | [465,466,467] |

| Didymellaceae | Nothophoma | LSU and ITS | tub2 and rpb2 | [468,469,470,471] |

| Sporocadaceae | Pestalotiopsis | LSU | ITS, tub2 and tef1-α | [472,473] |

| Togninicaceae | Phaeoacremonium | SSU and LSU | ACT and tub2 | [474,475,476] |

| Hymenochataceae | Phellinotus | LSU | ITS, tef1-α and rpb2 | [477] |

| Hymenochaetaceae | Phellinus | LSU | ITS, tef1-α and rpb2 | [478,479,480,481] |

| Phyllostictaceae | Phyllosticta | ITS | ITS, LSU, tef1-α, GAPDH and ACT | [57,482,483] |

| Peronosporacae | Phytophthora | LSU, SSU and COX2 | LSU, tub2 and COX2 | [484,485] |

| Peronosporaceae | Plasmopara | LSU | LSU | [486] |

| Leptosphaeriaceae | Plenodomus | LSU | ITS, tub2 and rpb2 | [487] |

| Sporocadaceae | Pseudopestalotiopsis | LSU | ITS, tub2 and tef1-α | [488,489] |

| Pyriculariaceae | Pseudopyricularia | LSU and rpb1 | ACT, rpb1, ITS and CAL | [490,491] |

| Saccotheciaceae | Pseudoseptoria | LSU | LSU, ITS and rpb2 | [492,493] |

| Rhizopodaceae | Rhizopus | ITS and rpb1 | SSU, LSU and ACT | [494,495,496] |

| Xylariaceae | Rosellinia | LSU and ITS | ITS | [497,498,499,500] |

| Didymellaceae | Stagonosporopsis | ITS | tub2 and rpb2 | [373,501,502] |

| Pleosporaceae | Stemphylium | ITS | CmdA and GAPDH | [503,504,505,506] |

| Dothidotthiaceae | Thyrostroma | LSU | ITS, tef1-α, rpb2 and tub2 | [507,508] |

| Tilletiaceae | Tilletia | LSU | ITS | [509,510,511,512] |

| Ustilaginaceae | Ustilago | LSU | ITS | [53,513] |

| Venturiaceae | Venturia | LSU and SSU | ITS | [514,515] |

It is also recommended to use diverse methods, including Bayesian inference, maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony coupled with automatic barcode gap discovery, coalescent-based methods or genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition to explore species boundaries in various fungal genera [358,360,364].

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

After compiling this manuscript, it was concluded thatabout 4–5 million species of fungi are distributed all across the globe, and less than 2% of them have been described to date. Different estimates of fungal species ranging between 0.1–9.9 million have been provided by different mycologists working continuously on the taxonomy and diversity of fungi. The addition of new fungal taxa (genera and species) is an ongoing process, as a number of natural environments and a variety of habitatsare still waiting to be explored in terms of their fungal diversity. Based on a regression relationship between time and described fungal species, the description rate of fungi was calculated, and new proposed estimates were also presented. As per the description rate observed after this regression relationship, the estimation of 1.5 million fungal species could be achieved by the year 2184, while the estimation of 2.2 million could be achieved by 2210 and 5.1 million by 2245.

Both classical and DNA-based methods to study fungi have their own utility and importance. While classical methods are still used widely due to low cost, ease of identifying species and ability to sample wide areas or many pieces of substrata, modern methods have also gained popularity due to their accuracy in characterizing the fungi which are not possible with traditional classical methods. When traditional morphology based species identification utilizes the overall morphology of an organism, DNA-based modern techniques require a very small amount of fungal sample. However, modern mycologists have accepted integrated approaches using both morphological and molecular data.

In the integral approach of traditional and modern methods of fungal analyses, fungal culture plays an important role. Production of different morphs on culture and other accessory structures are important for identification and characterization. Due to this non sporulation of many fungi neither on the natural substrate nor artificial culture media, the modern DNA-based technique proved to be more efficient to understand their taxonomy. New generation sequencing or metagenomic techniques are of much use to analyze the fungal diversity of different environments. There area large number of sequences from environmental samples (unculturable and dark taxa) available in GenBank which signifies the use of modern methods to describe many important fungi. The advancement in sequencing technologies of DNA and RNA is regularly helping researchers to study fungi in an integrative way and understand their biology, ecology and taxonomy in a better way. More than a billion HTS-derived ITS reads are available publicly in available databases and can be used by researchers during various mycological studies. It is important to use this data to assemble evidence hitherto overlooked, as well as new hypotheses, research questions and theories. If cultures of all fungi are deposited in culture collections and made easily available to researchers, it may perhaps add value to basic taxonomy research.