Abstract

During HIV/SIV infection, the upregulation of immune checkpoint (IC) markers, programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT), lymphocyte-activation gene-3 (LAG-3), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 (Tim-3), CD160, 2B4 (CD244), and V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), can lead to chronic T cell exhaustion. These ICs play predominant roles in regulating the progression of HIV/SIV infection by mediating T cell responses as well as enriching latent viral reservoirs. It has been demonstrated that enhanced expression of ICs on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells could inhibit cell proliferation and cytokine production. Overexpression of ICs on CD4+ T cells could also format and prolong HIV/SIV persistence. IC blockers have shown promising clinical results in HIV therapy, implying that targeting ICs may optimize antiretroviral therapy in the context of HIV suppression. Here, we systematically review the expression profile, biological regulation, and therapeutic efficacy of targeted immune checkpoints in HIV/SIV infection.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), immune checkpoint, immune checkpoint blocker, HIV therapy

1. Introduction

T cell exhaustion due to constant antigen stimulation results in chronic cellular dysfunction. It occurs during chronic infection or cancer when the same antigens repeatedly stimulate T cells, leading to a dysfunctional state [1]. During the process of chronic T cell exhaustion, T cell reactivation gradually declines along with enhanced expression of immune checkpoint (IC) markers. IC markers, primarily PD-1 (programmed cell death protein-1), CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4), TIGIT (T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain), LAG-3 (lymphocyte-activation gene-3), Tim-3 (T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3), CD160, 2B4 (CD244), BTLA (B and T lymphocyte attenuator) and VISTA (V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation), interact with their respective ligands to ”symphonically” switch T cell activation into T cell exhaustion [2,3]. By balancing co-stimulatory signals and co-inhibitory signals, IC markers guarantee T cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation in response to antigenic stimulation from invading microbes [4].

How increasing IC markers maintains T cell dysfunction and exhaustion has been extensively investigated in cancer [5,6]; by contrast, the mechanism of how IC markers on T cells affect the disease progression in viral infections, particularly in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), requires more exploration [2,5,7]. In HIV infection, checkpoint molecules were reported to be overexpressed on both CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in general [8]. Moreover, the regulation of IC marker expression was correlated with HIV disease progression, as reflected in viral RNA replication, T cell function, and HIV reservoir enrichment. In this review, we systematically compared the expression of T cell checkpoint markers with the stage of HIV infection to assess their potential as therapeutic targets.

2. HIV Infection Upregulates the Expression of Immune Checkpoints in T Cells

The expression of ICs on T cells varies according to the stage and the level of host immunity against HIV infection. PD-1 is a critical IC marker that is consistently upregulated during HIV infection. The percentage of PD-1+ CD4+ T cells in HIV-infected individuals (both long-term nonprogressors and common infectors) has been found to be significantly higher than that in healthy persons [9,10,11,12]. A 10% average increase in PD-1+ CD4+ T cells was seen in HIV-infected hosts as compared with HIV-naïve controls [10,13]. Among HIV-infected individuals, long-term nonprogressors (LTNPs) displayed a much lower percentage of PD-1+ CD4+ T cells (6–21%) as compared with viremic patients (14–50%) [9,11,12,14,15,16]. The percentage of PD-1+ CD4+ T cells decreased to 10–35% in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from common infectors with antiretroviral therapy (ART) [9,11,12,15,17,18]. Similarly, the proportion of PD-1+ CD8+ T cells has been shown to be 5–23%, 11–20%, 21–50%, and 10–30% in healthy persons, long-term nonprogressors, viremic patients, and ART-treated HIV-infected patients, respectively [9,10,12,14,15,18,19,20,21,22,23]. These data indicate that HIV infection upregulated PD-1 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dependent of ART treatment. Except for PD-1, numerous IC markers including CTLA-4, TIGIT, LAG-3, Tim-3, CD160, 2B4, and VISTA have been found to be regulated during HIV infection in general. Moreover, the majority of these IC markers showed regulatory trends similar to those of PD-1 (data in regular type in Table 1). In contrast, Zheng Zhang et al. found that HIV infection downregulated BTLA expression. It was shown that BTLA was reduced from 85% to 60–75% on CD4+ T cells and from 69% to 21–42% on CD8+ T cells in ART-naïve, HIV-infected patients as compared with healthy controls [24].

Table 1.

Expression profile of immune checkpoint markers on T cells from HIV/SIV-infected individuals.

| IC Marker |

Healthy Controls | HIV-Infected Individuals | Long-Term Nonprogressors | Viremic Individuals | ART-Treated HIV-Infected Individuals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ T Cells | CD8+ T Cells | CD4+ T Cells | CD8+ T Cells | CD4+ T Cells | CD8+ T Cells | CD4+ T Cells | CD8+ T Cells | CD4+ T Cells | CD8+ T Cells | |

| PD-1 | 5–20% [9,10,11,12] RM: 12% [29] |

5–23% [9,10,12,19,21,23,30] | 10% [10] | 10% [10] | 6–21% [9,11,16,31] | 11–20% [9,31] | 14–50% [9,11,12,14,15,16,31] RM: 6% [29] |

21–50% [9,12,14,15,19,20,21,23,30,31] | 10–35% [9,11,12,15,17,18] RM: 10% [29] |

10–30% [9,11,12,15,18,21,23,30] |

| TIGIT | 10–18% [10,11,32] | 30% [10,32,33] RM: 20% [32] |

20% [10] | 50% [10] RM: 40% [32] |

18–19% [11,32] | 50–57% [32,33] | 21–30% [11,32] | 65–70% [32,33] | 17–20% [11,17,32] | 45–60% [32,33] |

| CTLA-4 | 1–6% [11,12,34,35] RM: 4% [29] |

1–2% [12,35] | 6%-11% [34,35] | 1% [35] | 3–7% [11,16,31] | 0.67% [31] | 2–10% [11,12,16,31] RM: 2% [29] |

0.37, 10–12% [12] | 1–8% [11,12,34] RM: 1% [29] |

5% [12] |

| LAG-3 | 6% [36] RM: 9% [36] |

5–7% [30,36] RM: 9% [36] |

N/A | N/A | 0.065% [31] | 0.047% [31] | 0.021,14–48% [14,31,36] RM: 12% [36] |

0.004,8–32% [14,30,31,36] RM: 15% [36] |

12% [17] | 4% [30] |

| Tim-3 | 3–15% [10,37] RM: 1% [38] |

5–29% [10,37] RM: 5% [38] |

5% [10] | 5% [10] | 22% [37] | 30% [37] | 30–41% [14,31,37] RM: 2% [38] |

14–59% [14,20,37] RM: 5% [38] |

0.8% [17] | N/A |

| CD160 | 3% [10] | 1–10% [10,21,30,39] | 12% [10] | 20% [10] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 15–40% [21,30,39] | 1.1% [17] | 10–16% [21,30] |

| 2B4 | 3% [10] | 40–57% [10,21,30] | 10% [10] | 65% [10] | 5% [31] | 70% [31] | 10% [31] | 75–85% [21,30,31] | 9.5% [17] | 60–70% [21,30] |

| BTLA | 85% [24] | 69% [24] | N/A | N/A | 75% [24] | 42% [24] | 60% [24] | 21% [24] | N/A | N/A |

| VISTA | 3% [10] | 5% [10] | 8% [10] | 10% [10] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

RM, rhesus monkey; ART, active antiretroviral therapy; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; TIGIT, T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4; LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene-3, Tim-3, T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3, BTLA, B and T lymphocyte attenuator; VISTA, V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation; N/A, not assessed.

The underlying mechanism of regulation of IC expression mediated by HIV infection is still unknown and needs further investigation. How HIV regulates PD-1/CTLA-4/Tim-3 expression in CD4+ T cells is partially understood, as the HIV Nef protein upregulates PD-1 transcription in HIV-infected CD4+ T cell by activating p38 MAPK [25]. However, the Nef protein has also been reported to downregulate CTLA-4 expression in HIV-infected CD4+ T cell to provide optimal cellular conditions for cell activation and viral replication [26]. Regarding the regulation of Tim-3 by HIV, evidence has shown that the transmembrane domain of the HIV Vpu protein could downregulate Tim-3, while the di-leucine motif (LL164/165) of the HIV Nef protein upregulated Tim-3 expression on the surface of HIV-infected CD4+ T cells in vitro [27,28].

Non-human primate animal models that are widely used in studying HIV/SIV disease have shown different results as compared with humans. For example, SIV-infected rhesus macaques have relatively stable expression of PD-1, CTLA-4, TIGIT, LAG-3, and Tim-3 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with little change in expression (data in bold type in Table 1).

3. Immune Checkpoints Are Associated with Progression of Disease in HIV/SIV Infection

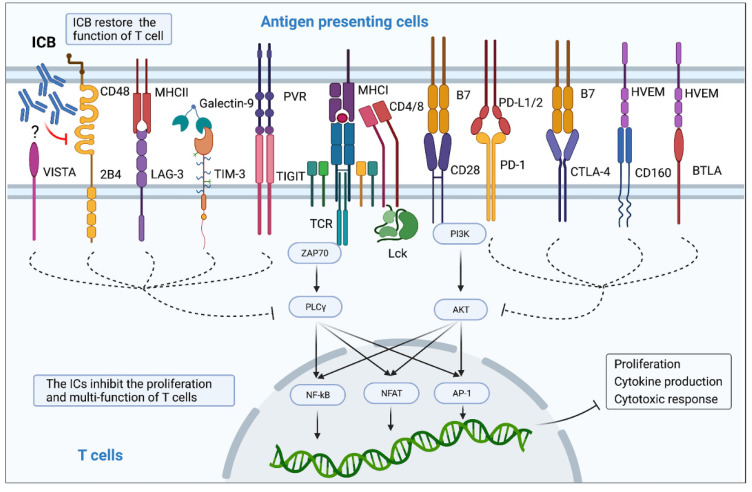

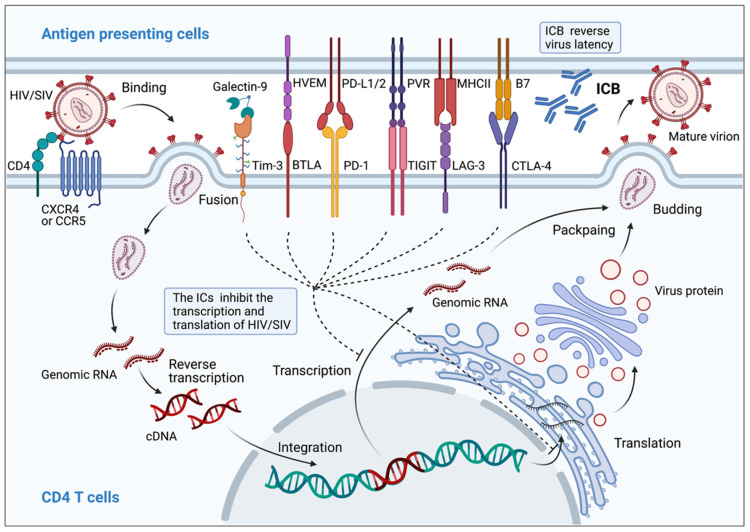

IC expression has been found to be highly correlated with disease progression after HIV/SIV infection, involving activation, proliferation, and function of T cells (Figure 1), and formation and persistence of HIV/SIV latency (Figure 2, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Immune checkpoint proteins impair proliferation and multi-functionality of T cells. Interaction between immune checkpoint markers and their ligands transmits inhibitory signals to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. These inhibitory signals limit TCR- and CD28-mediated co-stimulatory pathway, including the NF-κB, NFAT, and AP-1 signaling pathways, which suppress proliferation, cytokine production, and cytotoxic response. IC blockers are able to cause ligand dissociation from the ICs and restore T cell activation.

Figure 2.

Immune checkpoint proteins contribute to HIV/SIV latency. PD-1, TIGIT, LAG-3, CTLA-4, Tim-3, and BTLA signaling pathways are involved in generating an HIV reservoir and its persistence. The binding of these ICs and their ligands enforces silencing of integrated HIV DNA at the transcriptional and/or translational level. IC blockers can reactivate HIV from the cellular reservoir and produce new virions by blocking IC-ligand interactions in CD4+ T cells.

Table 2.

Biological role of immune checkpoint markers on T cell function in HIV/SIV infection.

| IC Marker | Function Mediated by HIV/SIV Infection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ T Cell | CD8+ T Cell | |||

| PD-1 | Proliferation | Proliferation | ||

| Cytokine secretion |

|

Cytokine secretion | ||

| Virus reservoirs | ||||

| TIGIT | Virus reservoirs | Proliferation | ||

| Cytokine secretion |

|

|||

| CTLA-4 | Proliferation |

|

Cytokine secretion |

|

| Cytokine secretion |

|

|||

| Virus reservoirs | ||||

| LAG-3 | Proliferation |

|

Proliferation |

|

| Cytokine secretion |

|

Cytokine secretion |

|

|

| Virus reservoirs | ||||

| Tim-3 | Proliferation | Proliferation | ||

| Cytokine secretion | Cytokine secretion |

|

||

| Virus reservoirs | ||||

| CD160 | N/A | Proliferation | ||

| Cytokine secretion | ||||

| 2B4 | Cytokine secretion |

|

Proliferation |

|

| Cytokine secretion | ||||

| BTLA | Cytokine secretion |

|

N/A | |

| Virus reservoirs |

|

|||

| VISTA | Cytokine secretion |

|

Cytokine secretion |

|

3.1. Correlation between ICs from CD28 Superfamily and Progression of Disease in HIV/SIV Infection

PD-1, CTLA-4, and BTLA, members of the CD28 superfamily, are characterized by an immune receptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) domain in the cytoplasm; PD-1, CTLA-4, and BTLA bind to PD-L1/2, B7, and herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM), respectively, to regulate progression of disease from HIV/SIV infection via transmission of inhibitory signals. PD-1 expressed on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is positively correlated with plasma viral RNA (vRNA) replication and negatively correlated with CD4+ T cell count in HIV infection [9,13,15,20,40,41,42]. In HIV-infected children, a high proportion of PD-1+ memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was also observed, correlating with vRNA, CD4/CD8 ratio, and immune activation [43]. PD-1 is also highly expressed on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells, with significant correlation to plasma viral load and CD4 T cell count [9,19,30,44].

It has been reported that overexpression of PD-1 impaired T cell proliferation and caused overactivation and exhaustion of T cells, ultimately leading to HIV progression [2]. In ART-treated HIV patients, both PD-1hi CD4+ T cells and PD-1hi CD8+ T cells were negatively regulated by HIV-specific T cell immune responses characterized by reduced IFN-γ secretion in response to HIV Gag and Env peptides [15]. Blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, especially simultaneous blocking of PD-L1 and stimulation through CD28, significantly enhanced the proliferation of HIV-specific CD4+ T cells in ART-naïve, HIV-infected patients [40,45], indicating a synergistic effect by targeting both the inhibitory and costimulatory pathways [45]. In addition, upregulated PD-1 has been observed in HIV-specific CD8+ T cells isolated from typical progressors (TPs) but not in long-term nonprogressors (LTNPs), leading to lower IFN-γ levels from HIV-specific CD8+ T cells and impaired proliferation of HIV-specific effector memory CD8+ T cells [9]. PD-1hi HIV-specific CD8+ T cells were shown to accumulate poorly differentiated phenotypes (CD27hi, CD28lo, CD57lo, CD127lo, CCR7– and CD45RA–) and showed lower production of IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α in response to HIV peptides [44]. Blockade of the PD-1 pathway enhanced proliferation [9,40,44,46] and increased IFN-γ, IL-2 [23,40], TNF-α, granzyme B, and lymphotoxin-α production by HIV-specific CD8+ T cells [44]. Polyfunctional HIV Gag-specific CD8+ T cell responses to PD-1 blockade could be improved by metformin therapy [47].

In an SIV-infected macaque model, PD-1 was also found to be an essential checkpoint marker during SIV infection. Low PD-1 expression was found in memory and naive CD8+ T cells, whereas high PD-1 levels were seen in SIV-specific CD8+ T cells isolated from PBMCs, lymph nodes, spleen, and mucosa, which might be attributed to the differences in TCR response [48]. Proliferation was impaired in SIV-specific PD-1hi CD8+ T cells [48]. Blocking PD-1 by recombinant rhesus macaque PD-1 (rMamu-PD-1) or rMamu-PD-1-immunoglobulin G (IgG) on PBMCs isolated from SIV-infected rhesus macaques increased the SIV-specific proliferative responses of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [49].

CTLA-4 expression on CD4+ T cells has been shown to be closely correlated with HIV progression, and CTLA-4 inhibited cytokine production and proliferation of T cells in chronic HIV infection. The proportion of CTLA-4+ CD4+ T cells was inversely correlated with CD4+ T cell counts and the CD4/CD8 ratio in both ART-naive and ART-treated HIV-1-infected patients [11,34]. The higher proportion of CTLA-4+ CD4+ T cells co-expressing high levels of CCR5 and Ki-67 resulted in increased susceptibility to HIV infection [34]. A subset of CTLA-4+ memory CD4+ T cells was also positively correlated with T cell activation (single and dual CD38 and HLA-DR-expressing memory CD4+ T cells) during HIV infection, reconfirming that CTLA-4 is a hallmark of HIV disease [11]. Moreover, expression of CTLA-4 was upregulated in HIV-specific CD4+ T cells, but could be downregulated by ART [45,50]. The increase in CTLA-4+ HIV-specific CD4+ T cells was correlated with higher vRNA levels and lower CD4+ T cell counts in PBMCs [45,50]. The blockade of CTLA-4 partially rescued cytokine production and proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets, as upregulated expression of IFN-γ, CD40L, IL-2, and TNF-α in both CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells [31], and restored the proliferation of HIV-specific CD4+ T cell producing IFN-γ and IL-2 [50].

The proportion of BTLAlow T cells has been shown to be positively correlated with HIV disease progression of HIV infection. Lower expression of BTLA on both T cells and HIV-specific CD8+ T cells was commonly found in HIV-infected patients either as TP or with AIDS, but rarely found in LTNP [24]. The proportion of BTLA+ CD4+ T cells was positively correlated with CD4+ T cell count, yet inversely correlated with vRNA and Ki-67 expression, respectively. Moreover, BTLA-mediated inhibitory signaling of CD4+ T cell activation as well as cytokine production was severely impaired in HIV-infected patients [24].

3.2. Correlation between ICs from CD4 Family Members and Disease Progression in HIV Infection

LAG-3, a member of the CD4 family, promotes T cell exhaustion by ligating to MHC II, and participates in HIV pathogenesis as a new predictor for disease progression of HIV infection. Tian et al. showed that the numbers of LAG-3+ CD4+ T cells and LAG-3+ CD8+ T cells were inversely correlated with CD4+ T cell counts, while the number of LAG-3+ CD4+ T cells was positively correlated with vRNA in HIV-positive individuals [36]. Another study found that the proportion of LAG-3+ CD8+ T cells was positively correlated with vRNA, but not correlated with CD4 T cell count [20]. A high proportion of LAG-3+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was also found to be related to continuous T cell activation, as indicated by co-expression with CD38 in HIV-1-infected individuals [36]. The putative correlation between LAG-3 expression and clinical indicators needs more data to support it.

The increased inhibitory signals transduced by LAG-3 have been shown to be related to functional T cell impairment, including enhanced production of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-10, and TNF-α in HIV-1-infected subjects in the presence of a LAG-3 blocker, and increased HIV Gag-stimulated proliferation of HIV-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ T and IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells. Overexpression of LAG-3 consistently validated the inhibitory regulation of LAG-3 during HIV infection. The synergistic enhancement between the LAG-3/MHC II pathway and the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway strongly promoted the T cell-mediated immune response against HIV [36].

3.3. Correlation between TIGIT and Disease Progression in HIV/SIV Infection

TIGIT is a common immune receptor linked to PVR/Nectin2 that induces potent immunosuppression, but the correlation between TIGIT expression and HIV infection is controversial. Glen et al. showed that the number of TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells and TIGIT+ CD4+ T cells was increased in HIV-infected patients during all stages of AIDS [32]. However, the frequency of TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells and TIGIT+ CD4+ T cells was also increased in ART-naïve and long-term ART-treated patients with HIV infection as compared with elite controllers and healthy subjects [11,33]. In HIV-infected patients, the proportion of TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells was inversely correlated with the CD4 T cell count and the CD4/CD8 ratio [32,33]. Expression of TIGIT on T cells may be related to HIV pathogenesis by mediating HIV replication and host immune activation during HIV infection [32]. Among long-term ART-treated, HIV-infected patients, a positive correlation between the numbers of TIGIT+ CD4+ T cells and CD4+ T cell-associated HIV DNA was found. The frequencies of TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells and TIGIT+ CD4+ T cells were positively correlated with the frequency of CD38+ HLA-DR+ cells in HIV-infected individuals [11,32,33]. In vitro studies indicated that TIGIT might limit CD8+ T cell proliferation and function against HIV by a unique pathway [32,33]. However, a recent study proposed that TIGIT upregulated genes associated with antiviral immunity in CD8+ T cells, suggesting that TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells maintain an intrinsic cytotoxicity rather than succumbing to a state of immune exhaustion in HIV-infected individuals [51]. Rhesus TIGIT (rhTIGIT) partially mimics human TIGIT expression and function during HIV infection. In SIV-infected rhesus macaques, expression of rhTIGIT was significantly increased on CD8+ T cells derived from lymph nodes (LNs) and spleen but not PBMCs significantly [32]. RhTIGIT inhibited the proliferation and cytokine secretion of SIV-specific CD8+ T cells [32].

3.4. Correlation between Tim-3 and Disease Progression in HIV/SIV Infection

The numbers of Tim-3+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been shown to be elevated in individuals with acute and chronic progression of HIV-1 infection, but not in patients with viral control, as compared with noninfected individuals. Expression of Tim-3 was upregulated on HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from HIV-1-infected patients with chronic progression [37,45,52], but this could be effectively reduced by ART. However, no significant increase in Tim-3 expression was found in an HIV-2 cohort [53]. As a potential predictor of HIV-1 disease progression, the expression of Tim-3 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells correlated positively with vRNA and CD38 expression, but was inversely correlated with CD4+ T cell counts in ART-free HIV infectors [37]. ART strongly attenuated the positive correlation between Tim-3 expression on CD8+ T cells, vRNA, and CD4+ T cell count [37]; but, the significant association between Tim-3 and CD38 was unaffected by ART [37]. These linear correlations were also observed between plasma HIV viral load and expression of Tim-3 on HIV-specific CD4+ T cells [45].

Tim-3-expressing T cells are dysfunctional because of their low capacity to proliferate, produce cytokines, and degranulate in response to ligation of Tim-3 (galectin-9). In both HIV-1 infected patients and healthy individuals, Tim-3 was shown to moderately inhibit IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CD107a production in total and HIV-specific Tim-3+ CD4+ T cells and Tim-3+ CD8+ T cells [37,54]. In chronic persistent HIV infection, the proliferation of Tim-3low CD8+ T cells was higher than that of their Tim-3hi counterparts [37]. Blocking Tim-3 enhanced proliferation and cytotoxicity in both HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [37,46,54]. Recently, Tim-3 was found to be a natural immune inhibitor against viral spread [27].

In SIV-infected rhesus monkeys, the percentage of Tim-3+ CD8+ T cells was significantly higher in LNs than in PBMCs [38]. Amancha et al. found that Tim-3 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells followed a ”reversed U” curve in PBMCs during SIV infection [55]. Therefore, there was little linear correlation between PBMC/LN-derived Tim-3+ T cells and SIV viremia [38,55]. Interestingly, using Tim-3+/PD-1+ double markers, the expression of these dual ICs on LN-derived CD8+ T cells was positively correlated with SIV plasma viremia [38]. The mechanism of Tim-3 regulation of HIV-infected T cells remains controversial and further studies are needed to clarify the pathway [38,55].

3.5. Correlation between CD160 and Disease Progression in HIV/SIV Infection

The expression of CD160 has been shown to be increased in CD8+ T cells in ART-naïve HIV-1-infected individuals [39,56], which could be remarkably reduced by ART, particularly in naïve CD8+ T cells [21,30,56]. Unexpectedly, the subset of CD160+ CD8+ T cells was higher in HIV-1-infected slow progressors (SPs) and ECs as compared with TPs. These results differed from those obtained for PD-1+ and CTLA-4+ CD8+ T cells in HIV infection [39,57]. Expression of CD160 on CD8+ T cells was associated with slow progression of HIV infection, and showed a positive correlation with CD4 T cell counts, but a negative correlation with vRNA. It was concluded that enhanced CD160 expression on CD8+ T cells promoted cytotoxicity against HIV [39]. HIV-specific CD160+ CD8+ T cells were dominantly proliferative and highly activated in ART-naïve, HIV-infected individuals, with increasing expression of granzyme B and CD107a [39]. In contrast, CD160 signaling could attenuate CD8+ T cell immunity against HIV chronic infection, largely through immunosuppression of CD160-HVEM (herpes virus entry mediator). Blockade of the CD160/HVEM pathway restored proliferation and cytokine production from HIV-specific CD8+ T cells [56]. Moreover, HIV-specific CD8+ T cells co-expressing PD-1, CD160, or 2B4, which have been defined as exhausted phenotypes, presented poor activation, reduced intracellular cytokine production, and attenuated responses [30,56,57].

The expression of 2B4 on CD8+ T cells has been shown to be higher in ART-naïve HIV patients, and the expression could be reduced by ART [21,30,57]. The cross-linkage of 2B4 with CD48 was considered an inhibitory signal, which downregulated the functionality of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells during disease progression associated with HIV infection. T cells against HIV could be cooperatively attenuated by co-expression of 2B4 with PD-1 and/or CD160, which was inversely correlated with production of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α from HIV-specific CD8+ T cells [30]. The percentage of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells expressing both 2B4 and PD-1 was negatively correlated with perforin production [57]. Blockade of 2B4 elevated the CD40L responses on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which could be exponentially augmented by PD-1 co-blockade in HIV-positive patients [31]. Co-blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 and 2B4/CD48 synergistically restored the proliferation of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells [30]. The findings indicated that 2B4, PD-1, and/or CD160 cooperatively exhausted CD8+ T cells against chronic HIV stimulation.

The expression of VISTA was significantly higher on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, with attenuated IFN-γ and TNF-α production in HIV-infected individuals [10].

3.6. Correlation between Co-Expression of Checkpoint Markers and Disease Progression in HIV Infection

PD-1 is an essential immune checkpoint marker, involved in multiple synergistic co-functions related to HIV-specific immune regulation. Numerous co-expressing phenotypes of checkpoint markers including PD-1+ TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells, PD-1+ TIGIT+ CD160+ 2B4+ CD8+ T cells, PD-1+ 2B4+ CD160+ Tim-3− CD8+ T cells, and PD-1+ TIGIT+ CTLA-4+ CD4+ T cells have been shown to be significantly increased in HIV-infected patients [21,22,32,33]. CTLA-4 was linked to PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD4+ T cells [45,50]. HIV-specific CD4+ T cells co-expressing PD-1 and CTLA-4 were found at much higher percentages in viremic patients as compared with ECs [45,50]. Co-expressed checkpoints exhibited stronger correlations with HIV viral load and CD4 T cell counts. The percentage of memory CD4+ T cells co-expressing PD-1, CTLA-4, and TIGIT was robustly correlated with CD4 T cell counts, vRNA, CD4/CD8 ratio, and CD4+ T cell activation during HIV infection [11]. In addition, PD-1+ TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells were inversely correlated with CD4 T cell counts, but positively correlated with vRNA [32]. HIV-specific CD4+ T cells co-expressing PD-1, CTLA-4, and Tim-3 exhibited greater aggregate correlation with vRNA [45]. A modest positive correlation between the percentage of PD-1+ CD160+ 2B4+ LAG-3− HIV-specific CD8+ T cells and virus load was shown during chronic HIV infection [30]. In T cells from HIV-viremic individuals, multiple expression of checkpoint markers including PD-1+ CD160+ CD8+ T cells, PD-1+ CD160+ 2B4+ CD8+ T cells, PD-1+ TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells, and PD-1+ Tim-3+ T cells were found to be associated with lower expression of cytokines against HIV as compared with T cells expressing single checkpoint markers [30,32,52,56]. In particular, PD-1+ CD160+ double pathways co-enhanced in CD8+ T cells resulted in poor survival [56]. The in vitro response of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells was better restored via blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 synergizing with TIGIT/CD155, 2B4/CD48, Tim-3/galectin-9, or BTLA/HVEM as compared with that from single blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 [30,32,46,52]. HIV-specific CD4+ T cell function was improved through co-blockade of PD-L1 with Tim-3 [52]. In summary, the synergistic effects of co-inhibition of these checkpoint markers were remarkable, but more investigation is warranted.

3.7. Correlation between Immune Checkpoint Markers and HIV/SIV Latency

HIV reservoirs remain largely understudied. Accumulating proof has shown that checkpoint markers play fundamental roles in maintaining HIV latency (Figure 2). The baseline levels of the checkpoint markers PD-1, Tim-3, and LAG-3 have been shown to be linearly correlated with total baseline HIV-1 DNA, which was predictive of the HIV DNA reservoir after ART, as well as time to rebound after ART withdrawal [14,58]. Such a correlation indicated that checkpoint markers represented the exhaustive dynamics of T cells interacting with HIV reservoirs. Expression of PD-1, TIGIT, and LAG-3 on CD4+ T cells was assumed to be positively correlated with the number of persistently infected CD4+ T cells considered to be the essential part of the HIV reservoir in patients controlled with successful ART [17,59,60]. PD-1 expressed on lymph node CD4+ T cells was characterized as a major source of replication-competent HIV, which presents a serious dilemma for achieving a functional cure [61,62,63].

In SIV-infected rhesus macaques, CTLA-4+ PD-1− memory CD4+ T cells were found with a large majority of cell-associated SIV Gag DNA in PBMCs, lymph nodes, spleen, and gut tissues in monkeys successfully controlled with ART. CTLA-4+ PD-1− memory CD4+ T cells isolated from lymph nodes were considered to be a major part of the persistent viral reservoir [64]. In contrast, we recently reported that LP-98 (a HIV fusion-inhibitory lipopeptide) monotherapy showed extremely potent antiviral efficacy in SHIVSF162P3-infected rhesus macaques. Interestingly, we found that a higher proportion of PD-1+ resting CD4+ central memory T cells was measured on both superficial lymph nodes and deep lymph nodes of stable virologic rebound (SVR) macaques as compared with that of stable virologic control (SVC) after withdrawal from LP-98 treatment, highlighting the close relationship between PD-1 and the LN viral reservoir [65]. In HIV-infected humanized mice, PD-1+ CD4+ T cells and TIGIT+ CD4+ T cells originating from spleens were enriched with latent and reactivatable HIV-1 [66]. In vitro experiments also indicated that HIV latency was enriched in PD-1, CTLA-4, Tim-3, or BTLA expressing CD4+ T cells, which could also be reversed by blockade of ICs [67,68,69,70]. The biological effects of ICs on HIV latency have been investigated with various experimental models, but need to be further verified, and the precise conclusions should be summarized for clinical application.

4. Therapeutic Effects of Immune Checkpoint Blockers on HIV/SIV Infection

Immune checkpoint blockers (ICBs) targeting PD-1 and CTLA-4 pathways combined with anti-HIV drugs have been tested in clinical and experimental trials to develop an effective therapeutic regimen (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Summary of therapeutic effects of IC blockers in HIV-infected patients.

| Reference | IC blocker | Target | Objective | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oscar Blanch-Lombarte [78] | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | ART HIV-1-infected individual with metastatic melanoma | Pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg/3 weeks) |

|

| Vanessa A Evans [67] | Nivolumab | PD-1 | ART HIV-infected individual with metastatic melanoma | Single intravenous infusion of nivolumab (3 mg/kg) |

|

| Jillian S.Y. Lau [79] | Nivolumab Ipilimumab | PD-1 CTLA-4 |

ART HIV-infected individual with metastatic melanoma | Ipilimumab (1 mg/kg/3 weeks) and Nivolumab (3 mg/kg/3 weeks) |

|

| Fiona Wightman [77] | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | ART HIV-infected individual with metastatic melanoma | Ipilimumab (3 mg/kg, four doses/3 week) |

|

| A Guihot [80] | Nivolumab | PD-1 | ART HIV-infected individual with NSCLC | Nivolumab (15 injections/14 days) |

|

| M Hentrich [81] | Nivolumab | PD-1 | ART HIV-infected individual with NSCLC | Chemoradiotherapy and surgical resection Nivolumab (3 mg/kg) |

|

| Brennan McCullar [82] | Nivolumab | PD-1 | ART HIV-infected individual with NSCLC | One cycle of carboplatin/paclitaxel Definitive chemo-radiation with cisplatin and etoposide Start nivolumab |

|

| Gwenaëlle Le Garff [83] | Nivolumab | PD-1 | ART HIV-infected individual with NSCLC | Decompressive radiotherapy Six cisplatin/gemcitabine and four Taxotere chemotherapy treatments Start nivolumab |

|

| E P Scully [84] | Nivolumab Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | ART HIV-1-infected individuals with malignancies | Nivolumab (participant 1 with head and neck SCC, standard dosing, for 18 months) Nivolumab (participant 2 with head and neck SCC, four doses) Pembrolizumab (participant 3 with squamous cell carcinoma of the skin) |

|

| Neil J Shah [85] | Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab, Atezolizumab, Durvalumab and Avelumab | PD-1/PD-L1 | HIV-infected individuals with advanced-stage cancers |

Anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy or anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy combined with chemotherapy |

|

| Thomas A. Rasmussen [86] | Nivolumab Ipilimumab | PD-1 CTLA-4 |

ART HIV-infected individual with advanced malignancies | Nivolumab (240 mg every 2 weeks) in combination with ipilimumab (1 mg/kg every 6 weeks) |

|

| Cynthia L Gay [89] | BMS-936559 | PD-L1 | ART HIV-1-infected adults | Single infusions of BMS-936559 (0.3 mg/kg) |

|

| Elizabeth Colston [88] | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | Chronic HIV-1 -infected individuals |

Ipilimumab, 0.1, 1, or 3 mg/kg, two doses every 28 days; or 5 mg/kg, four doses every 28 days |

|

Table 4.

Summary of therapeutic effects of IC blockers in macaque model.

| Reference | IC Blocker | Target | Objective | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vijayakumar Velu [96] |

Humanized mouse anti-human PD-1 Ab (clone EH12-1540) | PD-1 | SIV251/SIVmac239-infected Indian rhesus macaques | Anti-PD-1 Ab (3 mg/kg) in early chronic phase and in late chronic phase on days 0, 3, 7, and 10 |

|

| Adam C Finnefrock [107] |

Anti-human PD-1 Ab (clone 1B8) |

PD-1 | SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques | Therapeutic model: single infusion of anti-PD-1 Ab 1B8 (5 mg/kg) to chronic SIV-infected macaques before or during ART Prophylactic model: anti-PD-1 Ab 1B8 (5 mg/kg) to naive macaques immunized with an SIV-Gag adenovirus vector vaccine |

|

| Ravi Dyavar Shetty [97] |

Mouse anti- human PD-1 Ab |

PD-1 | SIV-infected rhesus macaques | Anti-PD-1 Ab (3 mg/kg) at either 10 or 90 weeks after SIV infection on 0, 3, 7, and 10 days |

|

| Praveen K Amancha [99] |

Recombinant macaque PD-1 fused to macaque Ig-Fc (rPD-1-Fc) | PD-1 | SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques | rPD-1-Fc (50 mg/kg) alone or in combination with ART during the early chronic phase |

|

| Geetha H Mylvagana [98] |

Primatized anti–PD-1 Ab (clone EH12- 2132/2133) |

PD-1 | Chronic SIVmac251-infected rhesus macaques | Stage I: anti-PD-1 Ab (3 mg/kg/dose, 5 doses) between 24 and 30 weeks after infection on days 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14. Stage II: RMs again treated with anti-PD-1 Ab (10 mg/kg/dose, three monthly, 3 doses) at 26–30 weeks following ART initiation |

|

| Diego A Vargas- Inchaustegui [102] | B7-DC-Ig fusion protein |

PD-1 | Chronic SIVmac251- infected rhesus macaques | ART plus B7-DC-Ig (10 mg/kg, weekly, 11 weeks), then B7-DC-Ig alone for 12 weeks |

|

| Elena Bekerman [110] |

Human/rhesus chimeric anti- PD-1 antibody |

PD-1 | ART SIVmac251-infected rhesus macaques | Anti-PD-1 chimeric Ab (10 mg/kg, every other week, four doses) with or without TLR7 agonist vesatolimod (0.15 mg/kg, every other week, 10 doses) |

|

| Sheikh Abdul Rahman [108] | Primatized anti–PD-1 antibody (clone EH12) | PD-1 | Chronical SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques | Immunized with a CD40L plus TLR7 agonist–adjuvanted DNA/MVA SIV239 vaccine (DNA vaccine: 1 mg/333 µL, 600 µL/dose, at weeks 38 and 42 MVA vaccine: 1 mL/dose, at weeks 46 and 60) during ART. Received anti–PD-1 treatment on days 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14, starting 10 days before the initiation of ART (3 mg/kg) and on week 38–44 starting with the first DNA prime during ART (10 mg/kg, 3 doses, every 3 weeks) |

|

| ChunxiuWu [109] | Anti-PD-1 antibody (GB226) | PD-1 | ChronicallySIV-infected macaque | Anti-PD-1 antibody injection (20 mg/kg) every 2 weeks from 1 to 7 weeks and rAd5-SIVgpe (1011vp in 1 mL PBS) at weeks 0 and 4 post ART discontinuation; ART treatment begins at week 3 before the initial vaccination |

|

| Enxiang Pan [106] | Genolimzumab | PD-1 | Chinese rhesus monkeys | Genolimzumab injection (20 mg/kg, every two weeks) at weeks −1, 1, 3, 5, and 7 and rAd5-SIVgpe (1011vp) injection at week 0 and 4; at week 42 after the initial vaccination, animals were challenged with repeated low-dose SIVmac239 |

|

| Ping Che [101] | Avelumab | PD-L1 | ART SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques | Avelumab (20 mg/kg, weekly, for 24 weeks) and rhIL-15 (10 µg/kg, daily, continuous infusion for 10 days, two cycles), then, ART was discontinued and avelumab treatment continued until completion of the 24-week treatment |

|

| Amanda L Gill [100] | Avelumab | PD-L1 | ART SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques | Avelumab (20 mg/kg, weekly) At week 24, all treatments were discontinued |

|

| Anna Hryniewicz [103] | MDX-010 | CTLA-4 | ART SIVmac251-infected rhesus macaques | Administered MDX-010 (10 mg/kg/injection) after ART initiation at weeks 5 and 8. |

|

| Todd Bradley [105] | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | Cynomolgus macaques |

Immunized with recombinant CH505 HIV Env gp120 (100 µg every 4 weeks) and ipilimumab (10 mg/kg) during the immunization 1–3 |

|

| Justin Harper [104] | Nivolumab Ipilimumab |

PD-1 CTLA-4 |

SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques | Weekly nivolumab and ipilimumab over four weeks during ART, then, ART was interrupted two weeks afterwards with a seven-month follow-up |

|

4.1. Immune Checkpoint Blockers Confer Partial Protection against Progression of HIV Infection

The efficacy and safety of ICBs against HIV infection have been reported to vary with pathological conditions [7,71,72,73,74,75,76] (Table 3). In HIV-infected patients with metastatic melanoma, a PD-1 blocker alone or combined with CTLA-4 blocker enhanced the function of HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells and reversed HIV latency in CD4+ T cells. The CTLA-4 blocker increased CD4 or CD8 T cell counts, elevated the level of CD4+ T cell activation, and reversed HIV latency following drug infusions [67,77,78,79]. In HIV-infected patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a PD-1 blocker helped to restore HIV-specific CD8+ T cell function and maintain HIV viremia. However, the PD-1 blocker could not consistently improve CD4 T cell counts and reduce HIV reservoirs [80,81,82,83]. In ART-treated HIV-infected patients with other advanced-stage malignancies, the HIV suppression was inconsistent when used with PD-1 blocker alone [79,84,85]. It is worth noting that anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 combination therapy moderately reversed HIV latency and potentially eliminated the HIV reservoir in ART-suppressed people living with HIV with advanced malignancies [86]. Moreover, ICBs, including pembrolizumab, nivolumab, ipilimumab, and durvalumab caused no serious adverse events (AEs) to patients, suggesting that patients with HIV should no longer be excluded from clinical trials testing checkpoint inhibitor therapies for various cancers [67,78,80,81,82,83,84,85,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94]. In HIV-1 infected patients without malignancies, the PD-L1 blocker was shown to enhance the HIV-1 Gag-specific CD8+ T cell response [89]. The CTLA-4 blocker reduced plasma viremia in proportion to drug concentration [88]. Safety is a significant challenge, as indicated by the immune-related adverse events (irAEs) that appeared in two clinical trials using a PD-1 blocker for HIV-infected individuals without malignancies [89,95]. Multiple injections of low doses of IC blocker might alleviate the side effects. At present, the differences in therapeutic regimens and the relatively small number of clinical cases might be the cause of the inconsistent outcomes. The tolerance and efficacy of IC blockers vary according to physiological state for HIV infectors with or without malignancies. Given that only clinical trial data for PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockers are available, the data from testing blockers against other ICs (TIGIT, LAG-3, Tim-3, CD160, 2B4, BTLA, and VISTA) may prove highly useful in treatment of AIDs. Therefore, how to combine specific IC blockers and other treatment strategies to design an effective therapeutic program for HIV infectors with or without malignancies is a problem worth studying. More tests of drug combinations in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo are necessary, to provide the missing information on clinical efficacy for curing AIDS.

4.2. Immune Checkpoint Blockers Confer Partial Protection against Progression of SIV Infection

SIV-infected rhesus macaques are the most widely used nonhuman primate (NHP) models for exploring the molecular mechanism and the potential application of novel HIV therapies. Analysis of ICB outcomes in NHP models has provided an experimental foundation and theoretical basis for HIV clinical research (Table 4). In SIV-infected rhesus macaques, the PD-1 blocker enhanced proliferation and function of SIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as increased the proliferation of memory B cells with elevated SIV Env-specific antibody [96,97,98,99]. A PD-1 blocker together with ART reduced viremia to a low level, increased the CD8+ T cell response, and in general, decreased the rebound after ART withdrawal [98,100,101,102]. The CTLA-4 blocker decreased vRNA levels in lymph nodes and restored the effector function of SIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells during ART without impeding rebound after ART suspension [103]. However, Justin Harper et al. recently reported that the combination of PD-1 blocker and CTLA-4 blocker was more effective than single blockade alone in robust latency reversal, while neither PD-1 blocker nor CTLA blocker could enhance SIV-specific CD8+ T cell function [104].

Using a prophylactic model with PD-1 blocker, the vaccine-induced, SIV-specific CD8+ T cell and B cell response has been augmented, resulting in better control of pathogenic SIV infection [105,106,107]. However, PD-1 blockade combined with therapeutic vaccination might be a double-edged sword for SIV therapy. In chronically SIV-infected rhesus macaques under ART, Sheikh et al. discovered that a PD-1 blocker could be used to enhance the therapeutic effects of SIV vaccination by improving vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell function, sustaining B cell homing into follicles for vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell responses, reducing the viral reservoir in lymphoid tissue and, thereby, controlling HIV rebound upon ART interruption [108]. Surprisingly, Wu et al. found the opposite outcome: PD-1 blockade in combination with therapeutic vaccination led to viral reservoir activation that accelerated viral rebound in chronically SIV-infected macaques after ART interruption [109]. Therefore, the therapeutic potential of vaccine + PD-1 blockade might be closely related to ART treatment and the use of this drug combination still needs to be optimized in the SIV-infected rhesus macaque model for developing an HIV-1 cure in the future. Activation of the viral reservoir and enhancement of SIV-specific CD8+ T cell functions are the two dominant factors that need to be considered in the design of an immunotherapeutic strategy. Combining IC blockers with vaccine might produce better outcomes for HIV therapy, but may also raise more safety concerns. Much work is required to determine the best combination to control virus without excessive toxicity.

In summary, the blockade of checkpoint targets is a promising strategy for controlling the disease progression of HIV or SIV infection functionally and clinically. More studies are on the way for translating this treatment into new patient regimens, hopefully soon.

5. Conclusions

Immune checkpoint markers serve as novel biomarkers for HIV infection. ICs control the switching of T cells between the states of activation and exhaustion, and are closely related to HIV pathogenesis. IC overexpression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells attenuated the HIV-specific T cell response. Moreover, ICs are preferentially expressed on the surface of persistently HIV-infected T cells. CD4+ T cells overexpressing ICs are commonly found to serve as HIV reservoirs, and the ICs might play an essential role in HIV latency. Correspondingly, the blockade of ICs was shown to reverse HIV latency and restore the T cell function, providing promising therapeutic opportunities for HIV therapy both experimentally and clinically. However, the underlying regulatory mechanism of IC expression triggered by HIV infection and the cellular immune pathways mediated by IC blockers are still unknown and need further investigation. The optimum therapeutic design of ICs blockers alone or combined with other robust antiviral strategies under study offer novel strategies for the achievement of an HIV cure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuhong Wang for her advice and help proofreading the article.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, J.X. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, J.X. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (grant number 2021-I2M-1-037), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81971944).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wherry E.J. T cell exhaustion. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:492–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fenwick C., Joo V., Jacquier P., Noto A., Banga R., Perreau M., Pantaleo G. T-cell exhaustion in HIV infection. Immunol. Rev. 2019;292:149–163. doi: 10.1111/imr.12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraehenbuehl L., Weng C.H., Eghbali S., Wolchok J.D., Merghoub T. Enhancing immunotherapy in cancer by targeting emerging immunomodulatory pathways. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022;19:37–50. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00552-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin S., Xu L., Yi M., Yu S., Wu K., Luo S. Novel immune checkpoint targets: Moving beyond PD-1 and CTLA-4. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:155. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyck L., Mills K.H.G. Immune checkpoints and their inhibition in cancer and infectious diseases. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017;47:765–779. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalbasi A., Ribas A. Tumour-intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:25–39. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wykes M.N., Lewin S.R. Immune checkpoint blockade in infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:91–104. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H., Moussa M., Catalfamo M. The Role of Immunomodulatory Receptors in the Pathogenesis of HIV Infection: A Therapeutic Opportunity for HIV Cure? Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1223. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J.Y., Zhang Z., Wang X., Fu J.L., Yao J., Jiao Y., Chen L., Zhang H., Wei J., Jin L., et al. PD-1 up-regulation is correlated with HIV-specific memory CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in typical progressors but not in long-term nonprogressors. Blood. 2007;109:4671–4678. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-044826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahbaz S., Dunsmore G., Koleva P., Xu L., Houston S., Elahi S. Galectin-9 and VISTA Expression Define Terminally Exhausted T Cells in HIV-1 Infection. J. Immunol. 2020;204:2474–2491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noyan K., Nguyen S., Betts M.R., Sonnerborg A., Buggert M. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Elite Controllers Maintain Low Co-Expression of Inhibitory Receptors on CD4+ T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:19. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakayama K., Nakamura H., Koga M., Koibuchi T., Fujii T., Miura T., Iwamoto A., Kawana-Tachikawa A. Imbalanced production of cytokines by T cells associates with the activation/exhaustion status of memory T cells in chronic HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2012;28:702–714. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H., Ren C., Song H., Ma L.L., Chen S.F., Wu M.J., Zhang H., Xu J.C., Xu P. Temporal and spatial characterization of negative regulatory T cells in HIV-infected/AIDS patients raises new diagnostic markers and therapeutic strategies. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2021;35:e23831. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurst J., Hoffmann M., Pace M., Williams J.P., Thornhill J., Hamlyn E., Meyerowitz J., Willberg C., Koelsch K.K., Robinson N., et al. Immunological biomarkers predict HIV-1 viral rebound after treatment interruption. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macatangay B.J.C., Gandhi R.T., Jones R.B., McMahon D.K., Lalama C.M., Bosch R.J., Cyktor J.C., Thomas A.S., Borowski L., Riddler S.A., et al. T cells with high PD-1 expression are associated with lower HIV-specific immune responses despite long-term antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2020;34:15–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whittall T., Peters B., Rahman D., Kingsley C.I., Vaughan R., Lehner T. Immunogenic and tolerogenic signatures in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected controllers compared with progressors and a conversion strategy of virus control. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2011;166:208–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fromentin R., Bakeman W., Lawani M.B., Khoury G., Hartogensis W., DaFonseca S., Killian M., Epling L., Hoh R., Sinclair E., et al. CD4+ T Cells Expressing PD-1, TIGIT and LAG-3 Contribute to HIV Persistence during ART. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005761. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoury G., Fromentin R., Solomon A., Hartogensis W., Killian M., Hoh R., Somsouk M., Hunt P.W., Girling V., Sinclair E., et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Persistence and T-Cell Activation in Blood, Rectal, and Lymph Node Tissue in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals Receiving Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;215:911–919. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrovas C., Casazza J.P., Brenchley J.M., Price D.A., Gostick E., Adams W.C., Precopio M.L., Schacker T., Roederer M., Douek D.C., et al. PD-1 is a regulator of virus-specific CD8+ T cell survival in HIV infection. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2281–2292. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann M., Pantazis N., Martin G.E., Hickling S., Hurst J., Meyerowitz J., Willberg C.B., Robinson N., Brown H., Fisher M., et al. Exhaustion of Activated CD8 T Cells Predicts Disease Progression in Primary HIV-1 Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005661. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen S.S., Fomsgaard A., Larsen T.K., Tingstedt J.L., Gerstoft J., Kronborg G., Pedersen C., Karlsson I. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) at Different Stages of HIV-1 Disease Is Not Associated with the Proportion of Exhausted CD8+ T Cells. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tailor J., Foldi J., Generoso M., McCarty B., Alankar A., Kilberg M., Mwamzuka M., Marshed F., Ahmed A., Liu M., et al. Disease Progression in Children with Perinatal HIV Correlates with Increased PD-1+ CD8 T Cells that Coexpress Multiple Immune Checkpoints. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;224:1785–1795. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J., Huang H.H., Tu B., Zhou M.J., Hu W., Fu Y.L., Li X.Y., Yang T., Song J.W., Fan X., et al. Reversal of the CD8(+) T-Cell Exhaustion Induced by Chronic HIV-1 Infection Through Combined Blockade of the Adenosine and PD-1 Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:687296. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.687296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z., Xu X., Lu J., Zhang S., Gu L., Fu J., Jin L., Li H., Zhao M., Zhang J., et al. B and T lymphocyte attenuator down-regulation by HIV-1 depends on type I interferon and contributes to T-cell hyperactivation. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;203:1668–1678. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muthumani K., Choo A.Y., Shedlock D.J., Laddy D.J., Sundaram S.G., Hirao L., Wu L., Thieu K.P., Chung C.W., Lankaraman K.M., et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef induces programmed death 1 expression through a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mechanism. J. Virol. 2008;82:11536–11544. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00485-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Far M., Ancuta P., Routy J.P., Zhang Y., Bakeman W., Bordi R., DaFonseca S., Said E.A., Gosselin A., Tep T.S., et al. Nef promotes evasion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected cells from the CTLA-4-mediated inhibition of T-cell activation. J. Gen. Virol. 2015;96:1463–1477. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prevost J., Edgar C.R., Richard J., Trothen S.M., Jacob R.A., Mumby M.J., Pickering S., Dube M., Kaufmann D.E., Kirchhoff F., et al. HIV-1 Vpu Downregulates Tim-3 from the Surface of Infected CD4(+) T Cells. J. Virol. 2020;94:e01999-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01999-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacob R.A., Edgar C.R., Prevost J., Trothen S.M., Lurie A., Mumby M.J., Galbraith A., Kirchhoff F., Haeryfar S.M.M., Finzi A., et al. The HIV-1 accessory protein Nef increases surface expression of the checkpoint receptor Tim-3 in infected CD4(+) T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297:101042. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoang T.N., Harper J.L., Pino M., Wang H., Micci L., King C.T., McGary C.S., McBrien J.B., Cervasi B., Silvestri G., et al. Bone Marrow-Derived CD4(+) T Cells Are Depleted in Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Macaques and Contribute to the Size of the Replication-Competent Reservoir. J. Virol. 2019;93:e01344-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01344-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto T., Price D.A., Casazza J.P., Ferrari G., Nason M., Chattopadhyay P.K., Roederer M., Gostick E., Katsikis P.D., Douek D.C., et al. Surface expression patterns of negative regulatory molecules identify determinants of virus-specific CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in HIV infection. Blood. 2011;117:4805–4815. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teigler J.E., Zelinskyy G., Eller M.A., Bolton D.L., Marovich M., Gordon A.D., Alrubayyi A., Alter G., Robb M.L., Martin J.N., et al. Differential Inhibitory Receptor Expression on T Cells Delineates Functional Capacities in Chronic Viral Infection. J. Virol. 2017;91:e01263-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01263-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chew G.M., Fujita T., Webb G.M., Burwitz B.J., Wu H.L., Reed J.S., Hammond K.B., Clayton K.L., Ishii N., Abdel-Mohsen M., et al. TIGIT Marks Exhausted T Cells, Correlates with Disease Progression, and Serves as a Target for Immune Restoration in HIV and SIV Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005349. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tauriainen J., Scharf L., Frederiksen J., Naji A., Ljunggren H.G., Sonnerborg A., Lund O., Reyes-Teran G., Hecht F.M., Deeks S.G., et al. Perturbed CD8(+) T cell TIGIT/CD226/PVR axis despite early initiation of antiretroviral treatment in HIV infected individuals. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40354. doi: 10.1038/srep40354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leng Q., Bentwich Z., Magen E., Kalinkovich A., Borkow G. CTLA-4 upregulation during HIV infection: Association with anergy and possible target for therapeutic intervention. AIDS. 2002;16:519–529. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steiner K., Waase I., Rau T., Dietrich M., Fleischer B., Broker B.M. Enhanced expression of CTLA-4 (CD152) on CD4+ T cells in HIV infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1999;115:451–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian X., Zhang A., Qiu C., Wang W., Yang Y., Qiu C., Liu A., Zhu L., Yuan S., Hu H., et al. The upregulation of LAG-3 on T cells defines a subpopulation with functional exhaustion and correlates with disease progression in HIV-infected subjects. J. Immunol. 2015;194:3873–3882. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones R.B., Ndhlovu L.C., Barbour J.D., Sheth P.M., Jha A.R., Long B.R., Wong J.C., Satkunarajah M., Schweneker M., Chapman J.M., et al. Tim-3 expression defines a novel population of dysfunctional T cells with highly elevated frequencies in progressive HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2763–2779. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita T., Burwitz B.J., Chew G.M., Reed J.S., Pathak R., Seger E., Clayton K.L., Rini J.M., Ostrowski M.A., Ishii N., et al. Expansion of dysfunctional Tim-3-expressing effector memory CD8+ T cells during simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus macaques. J. Immunol. 2014;193:5576–5583. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L., Zhang A., Xu J., Qiu C., Zhu L., Qiu C., Fu W., Wang Y., Ye L., Fu Y.X., et al. CD160 Plays a Protective Role During Chronic Infection by Enhancing Both Functionalities and Proliferative Capacity of CD8+ T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:2188. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Day C.L., Kaufmann D.E., Kiepiela P., Brown J.A., Moodley E.S., Reddy S., Mackey E.W., Miller J.D., Leslie A.J., DePierres C., et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cockerham L.R., Jain V., Sinclair E., Glidden D.V., Hartogenesis W., Hatano H., Hunt P.W., Martin J.N., Pilcher C.D., Sekaly R., et al. Programmed death-1 expression on CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells in treated and untreated HIV disease. AIDS. 2014;28:1749–1758. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rallon N., Garcia M., Garcia-Samaniego J., Cabello A., Alvarez B., Restrepo C., Nistal S., Gorgolas M., Benito J.M. Expression of PD-1 and Tim-3 markers of T-cell exhaustion is associated with CD4 dynamics during the course of untreated and treated HIV infection. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foldi J., Kozhaya L., McCarty B., Mwamzuka M., Marshed F., Ilmet T., Kilberg M., Kravietz A., Ahmed A., Borkowsky W., et al. HIV-Infected Children Have Elevated Levels of PD-1+ Memory CD4 T Cells With Low Proliferative Capacity and High Inflammatory Cytokine Effector Functions. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;216:641–650. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trautmann L., Janbazian L., Chomont N., Said E.A., Gimmig S., Bessette B., Boulassel M.R., Delwart E., Sepulveda H., Balderas R.S., et al. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1198–1202. doi: 10.1038/nm1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kassu A., Marcus R.A., D’Souza M.B., Kelly-McKnight E.A., Golden-Mason L., Akkina R., Fontenot A.P., Wilson C.C., Palmer B.E. Regulation of virus-specific CD4+ T cell function by multiple costimulatory receptors during chronic HIV infection. J. Immunol. 2010;185:3007–3018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K., Stecher C., Zettl M., Rosskopf S., Rieger A., Zlabinger G.J., Steinberger P. Antibodies targeting BTLA or TIM-3 enhance HIV-1 specific T cell responses in combination with PD-1 blockade. Clin. Immunol. 2017;183:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chew G.M., Padua A.J.P., Chow D.C., Souza S.A., Clements D.M., Corley M.J., Pang A.P.S., Alejandria M.M., Gerschenson M., Shikuma C.M., et al. Effects of Brief Adjunctive Metformin Therapy in Virologically Suppressed HIV-Infected Adults on Polyfunctional HIV-Specific CD8 T Cell Responses to PD-L1 Blockade. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2021;37:24–33. doi: 10.1089/aid.2020.0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrovas C., Price D.A., Mattapallil J., Ambrozak D.R., Geldmacher C., Cecchinato V., Vaccari M., Tryniszewska E., Gostick E., Roederer M., et al. SIV-specific CD8+ T cells express high levels of PD1 and cytokines but have impaired proliferative capacity in acute and chronic SIVmac251 infection. Blood. 2007;110:928–936. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onlamoon N., Rogers K., Mayne A.E., Pattanapanyasat K., Mori K., Villinger F., Ansari A.A. Soluble PD-1 rescues the proliferative response of simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells during chronic infection. Immunology. 2008;124:277–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaufmann D.E., Kavanagh D.G., Pereyra F., Zaunders J.J., Mackey E.W., Miura T., Palmer S., Brockman M., Rathod A., Piechocka-Trocha A., et al. Upregulation of CTLA-4 by HIV-specific CD4+ T cells correlates with disease progression and defines a reversible immune dysfunction. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1246–1254. doi: 10.1038/ni1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blazkova J., Huiting E.D., Boddapati A.K., Shi V., Whitehead E.J., Justement J.S., Nordstrom J.L., Moir S., Lack J., Chun T.W. Correlation Between TIGIT Expression on CD8+ T Cells and Higher Cytotoxic Capacity. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;224:1599–1604. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Z.N., Zhu M.L., Chen Y.H., Fu Y.J., Zhang T.W., Jiang Y.J., Chu Z.X., Shang H. Elevation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression on T cells appears early in HIV infection, and differential Tim-3 and PD-1 expression patterns can be induced by common gamma -chain cytokines. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015:916936. doi: 10.1155/2015/916936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tendeiro R., Foxall R.B., Baptista A.P., Pinto F., Soares R.S., Cavaleiro R., Valadas E., Gomes P., Victorino R.M., Sousa A.E. PD-1 and its ligand PD-L1 are progressively up-regulated on CD4 and CD8 T-cells in HIV-2 infection irrespective of the presence of viremia. AIDS. 2012;26:1065–1071. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835374db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakhdari A., Mujib S., Vali B., Yue F.Y., MacParland S., Clayton K., Jones R.B., Liu J., Lee E.Y., Benko E., et al. Tim-3 negatively regulates cytotoxicity in exhausted CD8+ T cells in HIV infection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amancha P.K., Hong J.J., Ansari A.A., Villinger F. Up-regulation of Tim-3 on T cells during acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection and on antigen specific responders. AIDS. 2015;29:531–536. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peretz Y., He Z., Shi Y., Yassine-Diab B., Goulet J.P., Bordi R., Filali-Mouhim A., Loubert J.B., El-Far M., Dupuy F.P., et al. CD160 and PD-1 co-expression on HIV-specific CD8 T cells defines a subset with advanced dysfunction. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002840. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pombo C., Wherry E.J., Gostick E., Price D.A., Betts M.R. Elevated Expression of CD160 and 2B4 Defines a Cytolytic HIV-Specific CD8+ T-Cell Population in Elite Controllers. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;212:1376–1386. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin G.E., Pace M., Shearer F.M., Zilber E., Hurst J., Meyerowitz J., Thornhill J.P., Lwanga J., Brown H., Robinson N., et al. Levels of Human Immunodeficiency Virus DNA Are Determined Before ART Initiation and Linked to CD8 T-Cell Activation and Memory Expansion. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;221:1135–1145. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pardons M., Baxter A.E., Massanella M., Pagliuzza A., Fromentin R., Dufour C., Leyre L., Routy J.P., Kaufmann D.E., Chomont N. Single-cell characterization and quantification of translation-competent viral reservoirs in treated and untreated HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007619. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rinaldi S., de Armas L., Dominguez-Rodriguez S., Pallikkuth S., Dinh V., Pan L., Grtner K., Pahwa R., Cotugno N., Rojo P., et al. T cell immune discriminants of HIV reservoir size in a pediatric cohort of perinatally infected individuals. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009533. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Banga R., Procopio F.A., Noto A., Pollakis G., Cavassini M., Ohmiti K., Corpataux J.M., de Leval L., Pantaleo G., Perreau M. PD-1(+) and follicular helper T cells are responsible for persistent HIV-1 transcription in treated aviremic individuals. Nat. Med. 2016;22:754–761. doi: 10.1038/nm.4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pantaleo G., Levy Y. Therapeutic vaccines and immunological intervention in HIV infection: A paradigm change. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2016;11:576–584. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyer Z., Palmer S. Targeting Immune Checkpoint Molecules to Eliminate Latent HIV. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2339. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McGary C.S., Deleage C., Harper J., Micci L., Ribeiro S.P., Paganini S., Kuri-Cervantes L., Benne C., Ryan E.S., Balderas R., et al. CTLA-4(+)PD-1(-) Memory CD4(+) T Cells Critically Contribute to Viral Persistence in Antiretroviral Therapy-Suppressed, SIV-Infected Rhesus Macaques. Immunity. 2017;47:776–788.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xue J., Chong H., Zhu Y., Zhang J., Tong L., Lu J., Chen T., Cong Z., Wei Q., He Y. Efficient treatment and pre-exposure prophylaxis in rhesus macaques by an HIV fusion-inhibitory lipopeptide. Cell. 2022;185:131–144.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Llewellyn G.N., Seclen E., Wietgrefe S., Liu S., Chateau M., Pei H., Perkey K., Marsden M.D., Hinkley S.J., Paschon D.E., et al. Humanized Mouse Model of HIV-1 Latency with Enrichment of Latent Virus in PD-1(+) and TIGIT(+) CD4 T Cells. J. Virol. 2019;93:e02086-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02086-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evans V.A., van der Sluis R.M., Solomon A., Dantanarayana A., McNeil C., Garsia R., Palmer S., Fromentin R., Chomont N., Sekaly R.P., et al. Programmed cell death-1 contributes to the establishment and maintenance of HIV-1 latency. AIDS. 2018;32:1491–1497. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van der Sluis R.M., Kumar N.A., Pascoe R.D., Zerbato J.M., Evans V.A., Dantanarayana A.I., Anderson J.L., Sekaly R.P., Fromentin R., Chomont N., et al. Combination Immune Checkpoint Blockade to Reverse HIV Latency. J. Immunol. 2020;204:1242–1254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fromentin R., DaFonseca S., Costiniuk C.T., El-Far M., Procopio F.A., Hecht F.M., Hoh R., Deeks S.G., Hazuda D.J., Lewin S.R., et al. PD-1 blockade potentiates HIV latency reversal ex vivo in CD4(+) T cells from ART-suppressed individuals. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:814. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08798-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bui J.K., Cyktor J.C., Fyne E., Campellone S., Mason S.W., Mellors J.W. Blockade of the PD-1 axis alone is not sufficient to activate HIV-1 virion production from CD4+ T cells of individuals on suppressive ART. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0211112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cook M.R., Kim C. Safety and Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Patients With HIV Infection and Advanced-Stage Cancer: A Systematic Review. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1049–1054. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tapia Rico G., Chan M.M., Loo K.F. The safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced cancers and pre-existing chronic viral infections (Hepatitis B/C, HIV): A review of the available evidence. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020;86:102011. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abbar B., Baron M., Katlama C., Marcelin A.G., Veyri M., Autran B., Guihot A., Spano J.P. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in people living with HIV: What about anti-HIV effects? AIDS. 2020;34:167–175. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guaitoli G., Baldessari C., Maur M., Mussini C., Meschiari M., Barbieri F., Cascinu S., Bertolini F. Treating cancer with immunotherapy in HIV-positive patients: A challenging reality. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020;145:102836. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.102836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zerbato J.M., Purves H.V., Lewin S.R., Rasmussen T.A. Between a shock and a hard place: Challenges and developments in HIV latency reversal. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019;38:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pham H.T., Yoo S., Mesplede T. Combination therapies currently under investigation in phase I and phase II clinical trials for HIV-1. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2020;29:273–283. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2020.1724281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wightman F., Solomon A., Kumar S.S., Urriola N., Gallagher K., Hiener B., Palmer S., McNeil C., Garsia R., Lewin S.R. Effect of ipilimumab on the HIV reservoir in an HIV-infected individual with metastatic melanoma. AIDS. 2015;29:504–506. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blanch-Lombarte O., Galvez C., Revollo B., Jimenez-Moyano E., Llibre J.M., Manzano J.L., Boada A., Dalmau J., Daniel E.S., Clotet B., et al. Enhancement of Antiviral CD8(+) T-Cell Responses and Complete Remission of Metastatic Melanoma in an HIV-1-Infected Subject Treated with Pembrolizumab. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:2089. doi: 10.3390/jcm8122089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lau J.S.Y., McMahon J.H., Gubser C., Solomon A., Chiu C.Y.H., Dantanarayana A., Chea S., Tennakoon S., Zerbato J.M., Garlick J., et al. The impact of immune checkpoint therapy on the latent reservoir in HIV-infected individuals with cancer on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2021;35:1631–1636. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guihot A., Marcelin A.G., Massiani M.A., Samri A., Soulie C., Autran B., Spano J.P. Drastic decrease of the HIV reservoir in a patient treated with nivolumab for lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:517–518. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hentrich M., Schipek-Voigt K., Jager H., Schulz S., Schmid P., Stotzer O., Bojko P. Nivolumab in HIV-related non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:2890. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McCullar B., Alloway T., Martin M. Durable complete response to nivolumab in a patient with HIV and metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017;9:E540–E542. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.05.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McLean F.E., Gathogo E., Goodall D., Jones R., Kinloch S., Post F.A. Alemtuzumab induction therapy in HIV-positive renal transplant recipients. AIDS. 2017;31:1047–1048. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Scully E.P., Rutishauser R.L., Simoneau C.R., Delagreverie H., Euler Z., Thanh C., Li J.Z., Hartig H., Bakkour S., Busch M., et al. Inconsistent HIV reservoir dynamics and immune responses following anti-PD-1 therapy in cancer patients with HIV infection. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:2141–2142. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shah N.J., Al-Shbool G., Blackburn M., Cook M., Belouali A., Liu S.V., Madhavan S., He A.R., Atkins M.B., Gibney G.T., et al. Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in cancer patients with HIV, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C viral infection. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:353. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0771-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rasmussen T.A., Rajdev L., Rhodes A., Dantanarayana A., Tennakoon S., Chea S., Spelman T., Lensing S., Rutishauser R., Bakkour S., et al. Impact of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 on the HIV reservoir in people living with HIV with cancer on antiretroviral therapy: The AIDS Malignancy Consortium-095 study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73:e1973–e1981. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chughlay M.F., Njuguna C., Cohen K., Maartens G. Acute interstitial nephritis caused by lopinavir/ritonavir in a surgeon receiving antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis. AIDS. 2015;29:503–504. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Colston E., Grasela D., Gardiner D., Bucy R.P., Vakkalagadda B., Korman A.J., Lowy I. An open-label, multiple ascending dose study of the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab in viremic HIV patients. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0198158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gay C.L., Bosch R.J., Ritz J., Hataye J.M., Aga E., Tressler R.L., Mason S.W., Hwang C.K., Grasela D.M., Ray N., et al. Clinical Trial of the Anti-PD-L1 Antibody BMS-936559 in HIV-1 Infected Participants on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;215:1725–1733. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Anti-PD-1 Therapy OK for Most with HIV. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:130–131. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-NB2017-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gonzalez-Cao M., Moran T., Dalmau J., Garcia-Corbacho J., Bracht J.W.P., Bernabe R., Juan O., de Castro J., Blanco R., Drozdowskyj A., et al. Assessment of the Feasibility and Safety of Durvalumab for Treatment of Solid Tumors in Patients With HIV-1 Infection: The Phase 2 DURVAST Study. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1063–1067. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Spano J.P., Veyri M., Gobert A., Guihot A., Perre P., Kerjouan M., Brosseau S., Cloarec N., Montaudie H., Helissey C., et al. Immunotherapy for cancer in people living with HIV: Safety with an efficacy signal from the series in real life experience. AIDS. 2019;33:F13–F19. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adashek J.J., Junior P.N.A., Galanina N., Kurzrock R. Remembering the forgotten child: The role of immune checkpoint inhibition in patients with human immunod eficiency virus and cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:130. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0618-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lurain K., Ramaswami R., Mangusan R., Widell A., Ekwede I., George J., Ambinder R., Cheever M., Gulley J.L., Goncalves P.H., et al. Use of pembrolizumab with or without pomalidomide in HIV-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2021;9:e002097. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gay C.L., Bosch R.J., McKhann A., Moseley K.F., Wimbish C.L., Hendrickx S.M., Messer M., Furlong M., Campbell D.M., Jennings C., et al. Suspected Immune-Related Adverse Events With an Anti-PD-1 Inhibitor in Otherwise Healthy People with HIV. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2021;87:e234–e236. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Velu V., Titanji K., Zhu B., Husain S., Pladevega A., Lai L., Vanderford T.H., Chennareddi L., Silvestri G., Freeman G.J., et al. Enhancing SIV-specific immunity in vivo by PD-1 blockade. Nature. 2009;458:206–210. doi: 10.1038/nature07662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dyavar Shetty R., Velu V., Titanji K., Bosinger S.E., Freeman G.J., Silvestri G., Amara R.R. PD-1 blockade during chronic SIV infection reduces hyperimmune activation and microbial translocation in rhesus macaques. J. Clin. Investig. 2012;122:1712–1716. doi: 10.1172/JCI60612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mylvaganam G.H., Chea L.S., Tharp G.K., Hicks S., Velu V., Iyer S.S., Deleage C., Estes J.D., Bosinger S.E., Freeman G.J., et al. Combination anti-PD-1 and antiretroviral therapy provides therapeutic benefit against SIV. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e122940. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.122940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Amancha P.K., Hong J.J., Rogers K., Ansari A.A., Villinger F. In vivo blockade of the programmed cell death-1 pathway using soluble recombinant PD-1-Fc enhances CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses but has limited clinical benefit. J Immunol. 2013;191:6060–6070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gill A.L., Green S.A., Abdullah S., Le Saout C., Pittaluga S., Chen H., Turnier R., Lifson J., Godin S., Qin J., et al. Programed death-1/programed death-ligand 1 expression in lymph nodes of HIV infected patients: Results of a pilot safety study in rhesus macaques using anti-programed death-ligand 1 (Avelumab) AIDS. 2016;30:2487–2493. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]