Abstract

Genomic DNA is susceptible to endogenous and environmental stresses that modify DNA structure and its coding potential. Correspondingly, cells have evolved intricate DNA repair systems to deter changes to their genetic material. Base excision DNA repair involves a number of enzymes and protein cofactors that hasten repair of damaged DNA bases. Recent advances have identified macromolecular complexes that assemble at the DNA lesion and mediate repair. The repair of base lesions generally requires five enzymatic activities; glycosylase, endonuclease, lyase, polymerase, and ligase. The protein cofactors and mechanisms for coordinating the sequential enzymatic steps of repair are being revealed through a range of experimental approaches. We discuss the enzymes and protein cofactors involved in eukaryotic base excision repair emphasizing the challenge of integrating findings from multiple methodologies. The results provide an opportunity to assimilate biochemical findings with cell-based assays to uncover new insights into this deceptively complex repair pathway.

Keywords: DNA polymerase, genome stability, mechanism, mutagenesis, repair, structure

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

DNA repair pathways remove lesions from DNA and are required in the maintenance of genome integrity throughout the domains of life. This is because the integrity of the genome is constantly threatened through metabolism as well as environmental stressors such as radiation and chemical exposures. Many different forms of chemical alterations or lesions in DNA occur as a result of these stressors, and cells are forced to maintain a broad range of lesion-specific and general DNA repair pathways to address the lesion burden. The same lesion is often recognized and repaired by more than one repair pathway, providing a redundancy that ensures repair in the event of a deficiency in a primary pathway or a massive level of DNA damage. To achieve traffic control at lesion sites, repair pathways often use lesion-specific recognition systems, such that there is a degree of specialization in matching a lesion with an individual repair pathway.

Most repair pathways involve a series of sequential coordinated enzymatic reactions within multiprotein complexes assembled at the lesion. In contrast, the repair of some lesions involves the activity of a single DNA repair enzyme; e.g., photolyase reversal of the UV-induced pyrimidine dimer (1, 2), O6 methylguanine transferase removal of the O6 methyl group from O6 methylguanine (3-6).

Base excision repair (BER) is a cellular multi-enzyme DNA repair process for removing small and often non-helix distorting base lesions. The BER process has been the subject of many recent reviews (7-13), but in this review we will focus on biochemical, structural, and kinetic approaches toward gaining insights into step coordination in BER. Two BER sub-pathways have been characterized based on the size of the repair patch; short-patch (i.e., single-nucleotide) and long-patch BER (>1 nucleotide) are briefly illustrated in Figure 1. The apurinic/apyrimidinic- (AP-) site is the DNA lesion resulting from spontaneous base loss or DNA glycosylase base removal. The AP-site is considered one of the most common lesions in the genome by virtue of these events, and it accumulates at surprisingly high steady-state levels (50,000–200,000 AP sites per mammailan cell) in several mammalian tissues (14, 15). A persistent AP-site can have adverse consequences, since the lesion disrupts many DNA and RNA transactions, leads to cytotoxic strand breaks, mutations, and other forms of genomic instability (16-18). In addition to the AP-site, BER addresses a range of chemical base modifications or lesions (e.g., 8-oxoG, uracil and alkylated bases), that if not repaired, can lead to mutagenesis. Therefore, the cell possesses robust BER activity.

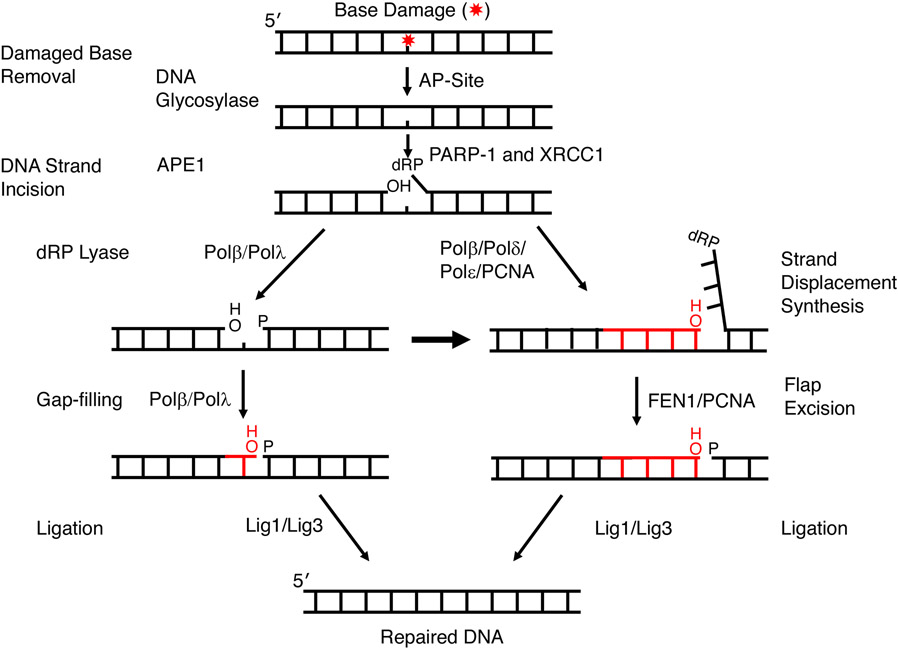

Figure 1.

A simplified scheme illustrating steps and factors in canonical sub-pathways of mammalian BER. BER is initiated by DNA glycosylase removal of a damaged base or by spontaneous base loss (not shown). Following APE1 incision 5′ to the AP site sugar, repair proceeds by short-patch BER (left path) or long-patch BER (right path). A red star depicts the damaged base and nascent nucleotide(s) is shown in red.

Figure 1 summarizes short-patch and long-patch BER. In this figure, a modified base is first removed by a lesion-specific monofunctional DNA glycosylase resulting in an AP-site with a ring-closed deoxyribose group in double-stranded DNA. Next, AP-endonucleases 1 (APE1) incises the DNA backbone at the 5´-side of the deoxyribose group leaving a one-nucleotide gap in double-stranded DNA with a 3´-hydroxyl and a 5´-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) flap at the margins. This intermediate is referred to as a “gap” because one base has been excised from the lesion containing strand generating a single-templating base for DNA synthesis. The accessory factors poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) and X-ray repair cross complementing 1 (XRCC1) bind at the gap and promote repair. In single-nucleotide BER, pols β or λ remove the 5´-dRP group and conduct gap filling DNA synthesis; this is followed by ligation by DNA ligases I or III.

There are situations where the 5´-dRP group (e.g., adenylated dRP) in the gap is a weak substrate for the lyase activity of pol β. In these cases, pol β or other polymerases conduct strand-displacement DNA synthesis in the sub-pathway called long-patch BER (right hand side of Figure 1). The 5´-flap generated during this mode of DNA synthesis is removed by Flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1) generating nicked DNA necessary for DNA ligation (19). The two BER sub-pathways summarized in Figure 1 operate in parallel; thus, with in vitro assays using cell extracts and a substrate containing the natural AP-site, single-nucleotide and long-patch BER were observed in approximately equal amounts (20). Further work is necessary to understand the mechanism of sub-pathway choice, but this choice probably depends on the specific base damage as well as particular enzymes and BER factors (11, 12, 21-23).

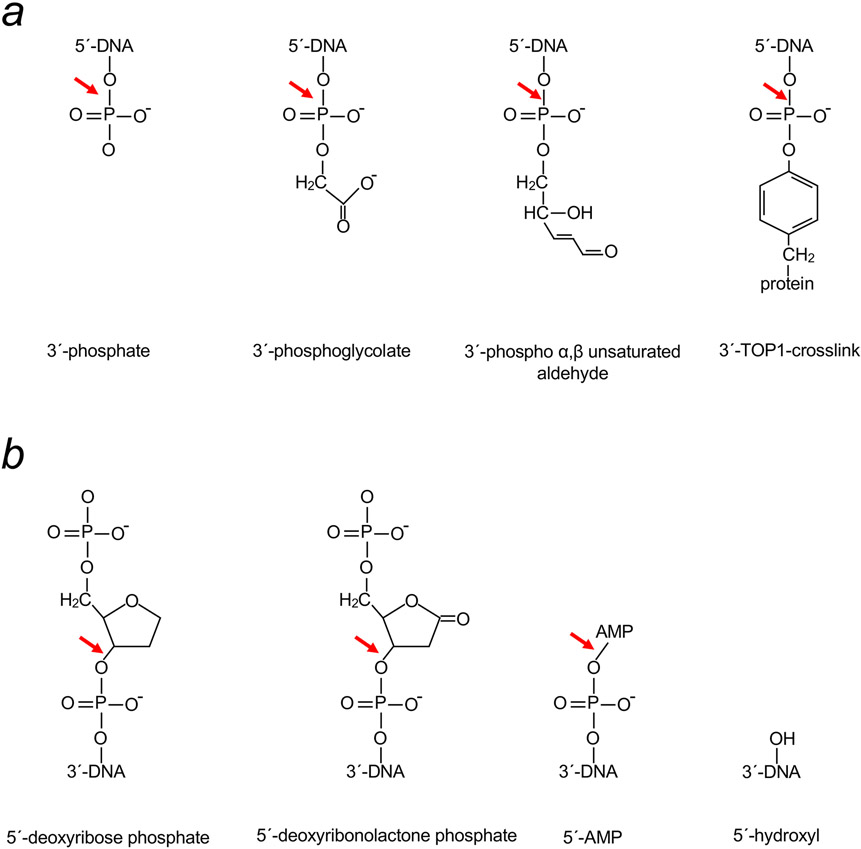

There are many variations of the core sub-pathways of BER (not shown) depending upon the success of each enzymatic step and the DNA substrate. For example, the deoxyribose group in the AP site is susceptible to strand incision via β-elimination. In this case, the 3´-hydroxyl necessary for DNA synthesis is blocked after the β-elimination strand incision, since O3´ is linked to the AP-site’s deoxyribose phosphate group (Figure 2a). This block must be removed to permit the subsequent repair steps, DNA synthesis and ligation. In case of a single-strand break or nick with 3´-hydroxyl and 5´-phosphate groups, DNA ligases mediate repair without the need for DNA polymerase and/or lyase end trimming activities (24). In contrast, in other cases bifunctional DNA glycosylase action is coupled with AP-site incision (25), resulting in a blocked 3´-margin that must be cleansed prior to downstream activities (i.e., DNA synthesis and ligation). Figure 2a illustrates examples of 3´-modifications that block DNA synthesis. The enzymes involved in these cleansing activities are described below.

Figure 2.

Common BER intermediates found in the incised DNA strand that need to be processed to accomplish DNA repair. Incision of an AP-site can result in (a) a 3´-blocking group that must be removed by an enzyme to generate a 3´-hydroxyl (red arrow) or (b) a 5´-blocking group that must be removed by an enzyme to generate a 5´-phosphate (red arrow). In the case where there is a 5´-hydroxyl, PNPK can add a phosphate group to allow ligation.

BER TOOLBOX

DNA Glycosylases

Mammalian DNA glycosylases are instrumental in initiating repair of base lesions (Table 1). These enzymes have been the subject of many reviews, and the general properties of the DNA glycosylases have been expertly reviewed (10). Uracil is a common mutagenic lesion in DNA resulting from cytosine deamination and misincorporation during replication (3). Crystal structures of human uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) revealed the capacity of this enzyme to distort DNA by wedging itself into the double helix and extruding the substrate uracil base from the DNA helix (26, 27). In extruding the base, the enzyme stabilizes the extruded base in the active site and activates the glycosidic bond for cleavage. These crystallographic structures, along with DNA binding results (28), illustrated stable interaction with the reaction product after base release. The results from this seminal work were prescient regarding an understanding of emerging enzyme kinetic observations with DNA glycosylases. Thus, the structural results illustrated the sculpting of the DNA substrate and assembly of the enzyme active site, as well as the tight DNA product binding. These features are found to translate to an understanding of the kinetic behavior of UDG. UDG and a number of other DNA glycosylases are found to exhibit “burst” kinetics (29, 30), where the enzymatic rate constant for the first turnover is fast compared to the rate of the linear steady-state phase of the time course. It is generally assumed that the burst phase reflects the catalytic rate constant (i.e., chemistry), whereas the slower steady-state rate reflects the rate constant for DNA product dissociation (i.e., koff) from the enzyme. Thus, these enzymes rapidly catalyze their reaction, but stall before releasing product DNA.

Table 1.

Mammalian DNA Glycosylases

| Enzyme | Abbreviation | General substrates |

|---|---|---|

| Monofunctional 1 | ||

| Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 4 | MBD4 | T and U paired with G |

| MutY Homolog | MYH | A paired with 8-oxoG |

| N-methylpurine-DNA glycosylase | MPG (AAG) | 3-alkylA |

| Thymine-DNA glycosylase | TDG | T and U paired with G |

| Uracil-DNA glycosylase | UNG | U |

| Bifunctional 1 | ||

| 8-Oxoguanine glycosylase | OGG1 | 8-oxoG paired with C |

| Endonuclease III-homolog 1 | NTH1 | Oxidized bases |

| Nei-like DNA glycosylase | NEIL (1, 2 and 3) | Oxidized bases |

Refers to the number of enzymatic activities; monofunctional, glycosylase activity only; bifunctional, glycosylase and lyase activities.

Oxidative DNA damage is a major burden to cells undergoing aerobic respiration. Cells have evolved an elaborate DNA repair system to quench oxidative DNA lesions (31). Nevertheless, a major promutagenic lesion resulting from oxidative stress is 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro- 2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxoG). This lesion is removed from DNA by 8-oxoG-DNA glycosylase (OGG1). Burst kinetics are also observed for OGG1; a rapid initial turnover is followed by a slower steady-state phase (29). The analysis also illustrated that OGG1 catalysis is sensitive to the presence of neighboring 5´-mismatches. Kinetic results of this type have been correlated with crystal structures of pre-catalytic and product complexes in several cases (29), and the results have implications for understanding the mechanism of BER. First, the lesion containing double-stranded DNA substrate undergoes a conformational change as the enzyme positions the scissile bond in the active site; and second, the product release phase is slower than the other phases of the catalytic cycle. These two features provide opportunities for regulation of the enzymatic activities that could impact overall BER. An interesting implication of the relatively slow product release phase is that the enzyme bound DNA repair intermediate is sequestered and hidden from cellular signaling systems that detect and monitor strand breaks; an excess of strand breaks leads to signaling events and cell death. Slow product release would limit the exposure of repair intermediates to cell death signaling pathways and also provides additional time for downstream BER enzymes to locate repair intermediates. This may occur by altering DNA and/or protein conformations of the repair complex that could facilitate substrate recognition by the downstream enzyme. This may involve direct physical interaction between enzymes and/or enzyme conformational recognition of the repair complex. Dissecting the molecular events that hasten transfer between sequential enzymatic steps requires further study. An implication of the initial substrate sculpting stage is that lesions will be protected from repair under conditions where the DNA structure blocks or impedes the conformational adjustments required for efficient catalysis, such as with non-B form DNA or a DNA-protein complex like the nucleosome core particle (32). The DNA sequence context effect observed with OGG1 DNA glycosylase appears to be an example of regulation at the substrate sculpting stage; in the presence of a 5´-mismatch, OGG1 still exhibits a biphasic time course indicating that it has sufficient catalytic activity with this irregular DNA substrate so that product release is still relatively slow (29).

AP Endonuclease

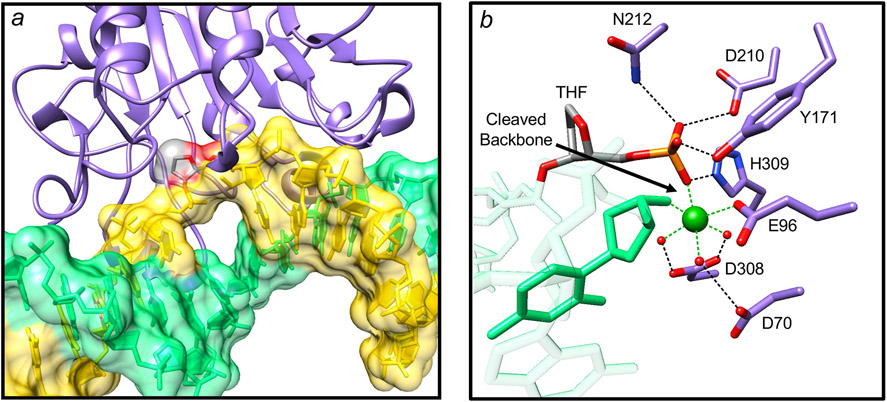

Two AP endonucleases have been characterized in eukaryotic systems. AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) is the main AP endonuclease, and the enzyme’s strand incision of the AP-site exhibits a kinetic pattern similar to that of the DNA glycosylases noted above, where a distinct burst phase precedes the slower steady-state phase. However, the reported rate constants for the burst phase with human APE1 have varied widely (33-35). This may be due to use of various different oligonucleotide substrates and/or reaction conditions. Thus, the enzyme/DNA complex may exhibit conformational differences that translates to alterations in active site geometry relative to the scissile bond. This general picture is reminiscent of the case with UDG and is well illustrated in a recent high-resolution crystal structure of human APE1 (Figure 3) (36). The B-form DNA substrate containing the AP-site analogue tetrahydrofuran is sculpted, such that the enzyme wedges itself into the helix at the scissile bond flipping the AP-site sugar to an extrahelical position (Figure 3a). A water molecule serves as a nucleophile in the chemical reaction and is stabilized by a network of enzyme sidechains. After strand incision, an active site magnesium ion and sidechain interactions stabilize the product (Figure 3b). This product structure suggests tight product DNA binding, and is consistent with the slow steady-state product release step observed in the biphasic time course (34-36).

Figure 3.

Features of a high-resolution crystal structure of the human APE1 (36). (a) The structure of a substrate complex reveals that the AP-site sugar (tetrahydrofuran, THF; gray carbons) is flipped outside of the DNA helix into the APE1 (purple ribbons) active site (PDB ID: 5DFI). The DNA strand that will be incised is colored yellow and the complementary strand is green. (b) Detailed view of the active site of a product complex illustrating a magnesium (green sphere; coordination illustrated with green dashed lines) associated interaction network (black dashed lines) that includes waters (small red spheres), protein side chains (purple carbons), and product DNA (green semi-transparent bonds except the nucleotide 5´ to the gap, solid green bonds) results in tight product binding (PDB ID: 5DFI).

DNA Polymerase/Lyase

Eukaryotic cells express multiple DNA polymerases and many of these appear to be involved in DNA repair. For example, human genes encoding at least 17 DNA polymerases have been characterized and at least 11 have properties consistent with roles in DNA repair (37). Efficient DNA repair involves a series of intermediates containing strand breaks that must to be rapidly processed so that they do not accumulate. The accumulation of strand break intermediates could trigger a cellular response leading to cytotoxicity or genomic instability through template-switching during DNA replication (38). Efficient repair requires that the proper repair enzyme bind to its substrate (i.e., repair intermediate), catalyze its reaction, and dissociate from the product in a programmed fashion.

Mammalian DNA polymerase β represents a case where it contributes two enzymatic reactions that modify the 3´- and 5´-termini in a gap with a single unpaired templating nucleotide. These activities reside on two domains of the enzyme: polymerase and lyase (Figure 4a) that modify upstream and downstream DNA of the incised strand, respectively. The wealth of kinetic and structural information on pol β with a variety of substrates (DNA and nucleotides) provides insight into the molecular attributes that hasten DNA binding and catalysis (39).

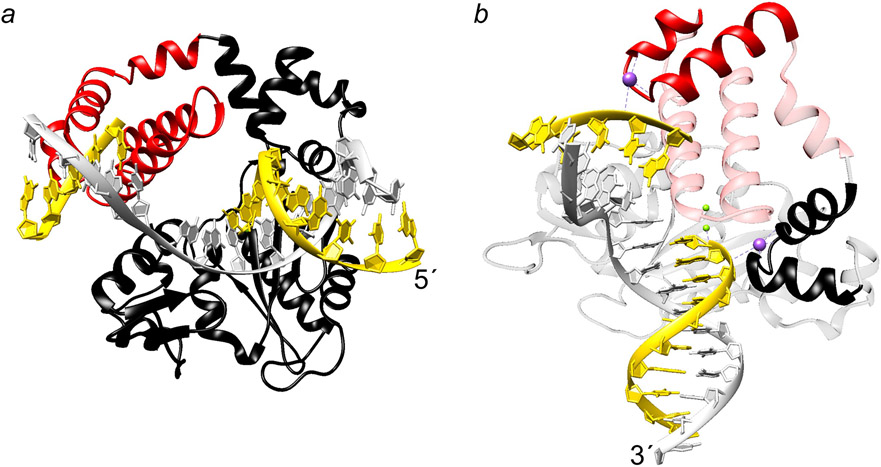

Figure 4.

DNA polymerase ternary substrate complex structure (52). (a) Ribbon representation of human pol β bound to single-nucleotide gapped DNA. The template strand is gray and the primer and downstream DNA strands are yellow and the 5´-terminus of the primer strand is indicated. The amino-terminal lyase domain is red and the polymerase domain is black. (b) An alternate view of the complex highlighting HhH motifs (solid ribbon representation; residues 55–79 and 91–118 of the lyase and polymerase domains, respectively) that interact with the DNA backbone of the incised strand through Na+ ions (purple spheres). The polymerase active site Mg2+ are indicated with green spheres. The 3´-terminus of the template strand is indicated.

As noted above, AP-endonuclease cleaves the DNA backbone 5´ to the AP-site generating a single-nucleotide gap with 3´-hydroxyl and 5´-dRP flap-containing terminus. DNA polymerase β catalyzes addition of a deoxynucleoside monophosphate (dNMP) to the 3´-terminus (polymerase activity) while removing the 5´-dRP-moiety (lyase activity) thereby generating nicked DNA. A crystallographic structure of pol β in complex with single-nucleotide gapped DNA with a 5´-tetrahydrofuran, a dRP analog, revealed that the gapped DNA is severely bent (~90°) at the templating nucleotide in the gap (40). This bend is stabilized by two Helix-hairpin-Helix (HhH) motifs that bind monovalent cations and interact with the DNA backbone in a sequence non-specific manner (41) (Figure 4b). The pol β DNA binding surface can easily be discerned by examining its electrostatic surface potential (Figure 5a). The blue surface (positive potential) parallels the negatively charged DNA backbone. Interestingly, this surface extends beyond the 5´-phosphate binding pocket of the lyase domain. The extended positively-charged surface may serve as a binding pocket for single-stranded DNA generated by the limited strand displacement DNA synthesis in long-patch BER. This would generate a substrate for FEN1-dependent tailoring of downstream DNA with a modified 5´-dRP flap thereby creating a nick with the 5´-phosphate necessary for efficient DNA ligation (42).

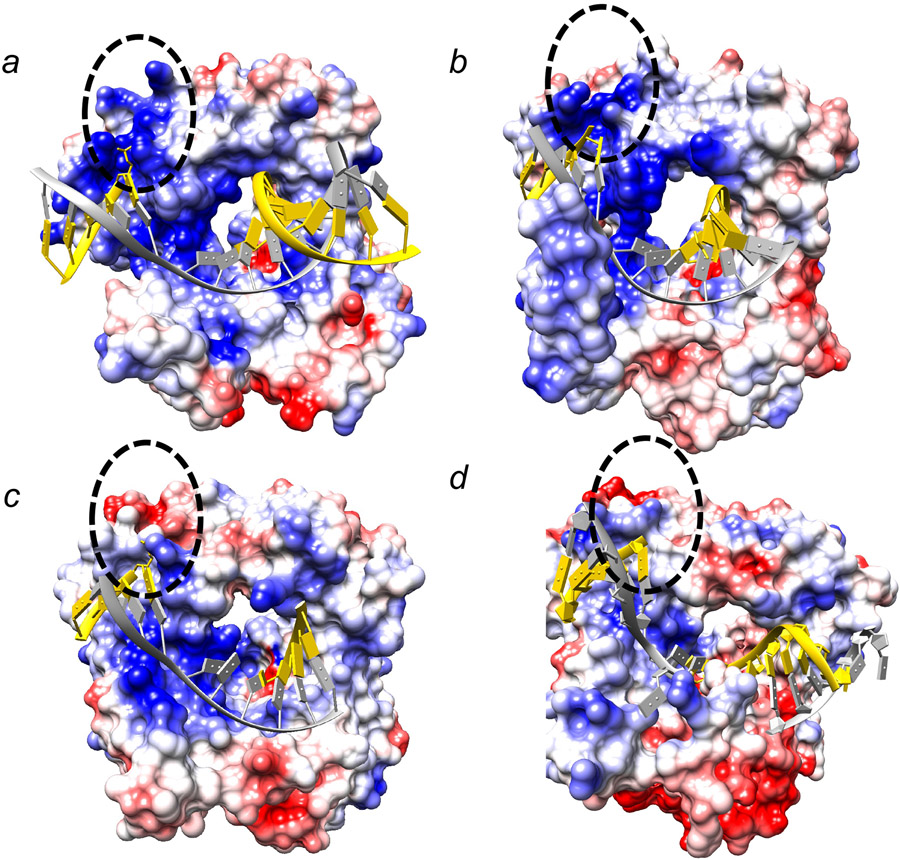

Figure 5.

Electrostatic surface potential of X-family DNA polymerases. The surface potential is mapped onto the protein surface (red to blue represents negative to positive potential, ±10 kcal/mol*e). The view is similar to that in Figure 3a. A black dashed oval identifies the position of the downstream 5´-phosphate. (a) pol β (PDB ID: 2FMS) (52), (b) pol λ (PDB ID: 1XSN) (53), (c) pol μ (PDB ID: 2IHM) (51), and (d) TdT (PDB ID: 5D49) (54). The DNA template strand is colored gray and primer and downstream strands are colored yellow.

DNA binding studies indicated that the 5´-phosphate in a DNA gap facilitates gap binding. Structural and DNA binding assays indicated that the basic amino-terminal lyase domain of pol β confers high affinity binding (43, 44) and lysine residues (residues 35 and 68) are observed to coordinate the 5´-phosphate of the downstream nucleotide in gapped DNA. The nearby Lys72 is a key lyase active site residue that participates in forming the Schiff base intermediate involved in the lyase reaction. In addition to these interactions with the 5´-margin of the gap, the polymerase domain undergoes conformational adjustments as it transitions from an open DNA binary complex to a closed ternary complex upon binding a deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP). Formation of the ternary complex can decrease the DNA dissociation constant by as much as 100-fold (45).

The severe bend in the gapped DNA trajectory exposes the DNA duplex boundaries within the gap. Pol β provides side chains that cap the ends of both the upstream and downstream duplex. His34 stacks with the downstream duplex, while the bases of the incoming and templating nucleotides make van der Waals contact with the side chains of Asp276 and Lys280, respectively.

While pol β is the primary polymerase involved in BER (46), pol λ has also been found to play a significant role in BER (47-49), especially under conditions of oxidatively-induced DNA damage. Like pol β, pol λ also belongs to the X-family of polymerases (50). Humans have four X-family DNA polymerases: pol β, pol λ, pol μ, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT). All four enzymes are believed to fill short gaps in DNA, but with different template specificities (51). In contrast to pol β and λ, pol μ and TdT do not require that their primer terminus be base-paired and have not been implicated in BER. The secondary and tertiary structures of the polymerase domain of all four X-family enzymes are remarkably similar (51-54). While pol β is the smallest (39-kDa), the other enzymes have an amino-terminal extension that includes a BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) domain that can interact with other repair factors, especially those involved in double-strand break repair. In addition, the loops connecting secondary structural elements of the polymerase domain confer substrate specificity for each enzyme. Examination of the electrostatic surface potential of the polymerase and 8-kDa domain (i.e., pol β lyase domain) reveals similarities and differences between these related enzymes. While pol β and λ display similar surface potentials (Figure 5a and b), the 8-kDa domain of pol μ and TdT are significantly less basic especially in the vicinity of the 5´-phosphate binding pocket (Figure 5c and d). These observations pointed to the presence of dRP lyase activity in pols β and λ (55) and the lack of this activity with pol μ and TdT. Phylogenetic analysis is consistent pol β and λ being more closely related than to either pol μ and TdT (56).

DNA Ligase

There are three families of DNA ligases in eukaryotes (57). Members from two of these families are involved in BER, DNA ligase I and DNA ligase III. These nick-sealing enzymes are ATP-dependent DNA ligases that utilize a three-step reaction mechanism: after formation of a covalent enzyme-adenylate intermediate (step 1), the adenylate group is transferred to the 5´-phosphate terminus in a DNA nick (step 2) followed by phosphodiester bond formation (step 3). Abortive ligation results after step 2 where phosphodiester bond formation is hindered resulting in an adenylated 5´-phosphate (Figure 2b). During BER, abnormalities at the nick (i.e., a mismatch resulting from pol β inserting the wrong nucleotide) hastens abortive ligation (58, 59).

DNA ligase I can interact with pol β (60) and supports robust ligation activity in reconstituted BER assays (61, 62). Likewise, DNA ligase III interacts with XRCC1 and can also support BER or single-strand break repair (63). Two isoforms of DNA ligase III are expressed that are targeted to the nucleus and mitochondria (64). Animal and cellular studies suggest that mitochondrial Ligase III, but not nuclear XRCC1/Ligase III is essential for mitochondrial repair and cellular viability (65, 66). Interestingly, Ligase I, but not Ligase III, appears to be critical in the repair of nuclear DNA damage induced by methyl methanesulphonate (MMS) (65).

Accessory Factors

PARP-1

The abundant nuclear enzyme PARP-1 is considered one of the “first responders” and a molecular sensor of DNA lesions, especially those containing AP-sites and strand breaks, the initial intermediates of BER (67, 68). Upon binding to the lesion-containing double stranded DNA, PARP-1 becomes activated for poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) synthesis (69). PARP-1 PARylates itself as well as other proteins involved in BER (70), and this promotes recruitment of other BER proteins, including XRCC1 and pol β. In this way, PARP-1 has a positive impact on the BER system. However, in the presence of excess DNA damage, PARP-1 can also have a negative impact on cell survival in two ways: first, PARP-1 can form a covalent cross-link with the AP-site (71), signaling BER failure, and such PARP-1 DNA-protein cross-links (DPCs) were found to increase in cells after treatment with PARP-1 inhibitors (72, 73); and second, BER failure triggers excess PARylation that can deplete cellular levels of ATP and NAD, resulting in cell killing.

Roles of PARP-1 in BER of the intact or incised AP-site were further considered. With many PARP inhibitors, DNA bound PARP-1 fails to produce PAR polymers or undergo mono-PARylation (74). Nevertheless, PARP inhibition results in extreme sensitization of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) to DNA methylating agents such as MMS and temozolomide (75). This PARP inhibitor cell killing effect in the presence of co-treatment with alkylating agents depends on expression of PARP-1, suggesting that the inhibited protein is involved in the cytotoxicity. In contrast, cell sensitivity to agents producing oxidatively-induced DNA damage are only modestly sensitized. This difference is, in part, due to the nature of the incised AP-sites during repair of methylated bases versus oxidized bases and the attendant PARP-1 DPCs during repair of methylated bases. Methylated bases are processed by monofunctional DNA glycosylases to yield AP-sites that can form DPCs with PARP-1; alternatively, oxidized bases are often processed by bifunctional DNA glycosylases that have associated lyase activity that cleaves the AP site (Table 1). The PARP-1 DPC is formed through Schiff base formation by attack of a PARP-1 lysine NH2 group at the aldehydic C1´ atom of the AP-site. Spontaneous reduction of the Schiff base, along with β-elimination, results in a strand break with a covalent linkage at the 3´-margin of the break, i.e., between the PARP-1 protein and AP-site sugar (71). Cellular deficiencies in BER factors (e.g., pol β or XRCC1) also are associated with extreme hypersensitivity to PARP-1 inhibitors (76), likely due in part to a greater accumulation of the AP-site repair intermediates (76) and PARP-1 DPCs (71).

XRCC1

Toward further understanding of the role of the accessory factor XRCC1, the importance of the pol β and XRCC1 interaction in BER has been investigated using imaging after introducing laser-induced damage. Introduction of DNA damage in this fashion did not involve DNA double-strand breaks and could be limited to single-strand breaks plus oxidatively-induced base lesions or to base lesions alone (77). Using the latter method, efficient recruitment of pol β to sites of laser-induced (355 nm, 0.165 μJ) DNA damage (single-strand breaks and oxidized base lesions) in living cells was found to depend upon XRCC1, and we proposed that the mechanism of recruitment involves XRCC1 and redox regulation of the conformation of the pol β binding site in XRCC1 (78, 79). The oxidized form of XRCC1 is known to bind pol β much tighter (50-fold) than the reduced form and to function in the response to DNA damage (80). Protection of MEFs against oxidative stress requires the oxidized form of XRCC1, implicating the XRCC1 redox status in regulating BER (79). While investigating XRCC1 regulation of pol β recruitment at sites of laser-induced DNA damage, we were surprised to find that pol β is able to provide a degree of protection to MEFs against BER-inducing agents in the complete absence of XRCC1. Therefore, these cells possess an XRCC1-independent, but pol β-dependent mechanism for protection against DNA damage (81). The nature of this XRCC1-independent repair mechanism is unknown.

DNA END CLEANSING ACTIVITIES

The strand incision and gapped DNA intermediates in BER often contain chemical groups that if not removed will block repair (Figure 2). Enzymes specialized in removing these blocking groups, often termed “dirty ends,” are well recognized and include aprataxin (APTX), tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (Tdp1), polynucleotide kinase 3'-phosphatase (PNKP), APE1 and FEN1, among others. The presence of gap trimming enzymes in cells throughout the phylogenetic tree illustrates the importance of their activities to genome stability. These enzymes are able to tailor the gap margins to liberate a 3´-hydroxyl for DNA polymerase and DNA ligase activities. Trimming enzymes also tailor 5´-end blocking groups. In the case of the incised AP-site, the dRP of the AP-site represents a blocking groups at the 5´-margin of a gap. This group is removed by the dRP lyase activity of pol β (82) or λ (55). With ligation failure at a gap or nick, the 5´-margin phosphate group becomes blocked by the abortive adenylation reaction of DNA ligase. The AMP blocking group is removed by APTX and in the case of adenylation of the 5´-dRP, the AMP group is removed by the lyase activity of pol β (83) or the combined activities of pol β and FEN1 during long-patch BER (19, 42). In other cases where a 5´-hydroxyl is generated blocking ligation, the 5´-terminus can be phosphorylated by PNKP thereby enabling ligation. PNKP can also remove a 3´-phosphate resulting from β,δ-elimination reactions at the AP-site sugar that blocks DNA synthesis (84). PNKP is, therefore the quintessential gap trimming enzyme. In addition to AP-site incision, APE1 has 3´-end exonuclease activity capable of removing a mismatched 3´-nucleotide (85, 86).

PNKP also is involved in repair of the DNA topoisomerase 1 (Top1) DPC formed with Top1 failure or in the presence of an inhibitor such as camptothecin. Top1 is attached to a strand break at the 3´-hydroxyl through a phosphotyrosine linkage (Figure 2a), and during DPC repair most of Top1 is subjected to proteosomal degradation. This is followed by removing the tyrosine group plus any residual peptide by Tdp1 (87, 88). The result is a phosphate blocked O3´; PNKP can subsequently generate the 3´-hydroxyl required for downstream repair activities.

MACROMOLECULAR ASSEMBLIES

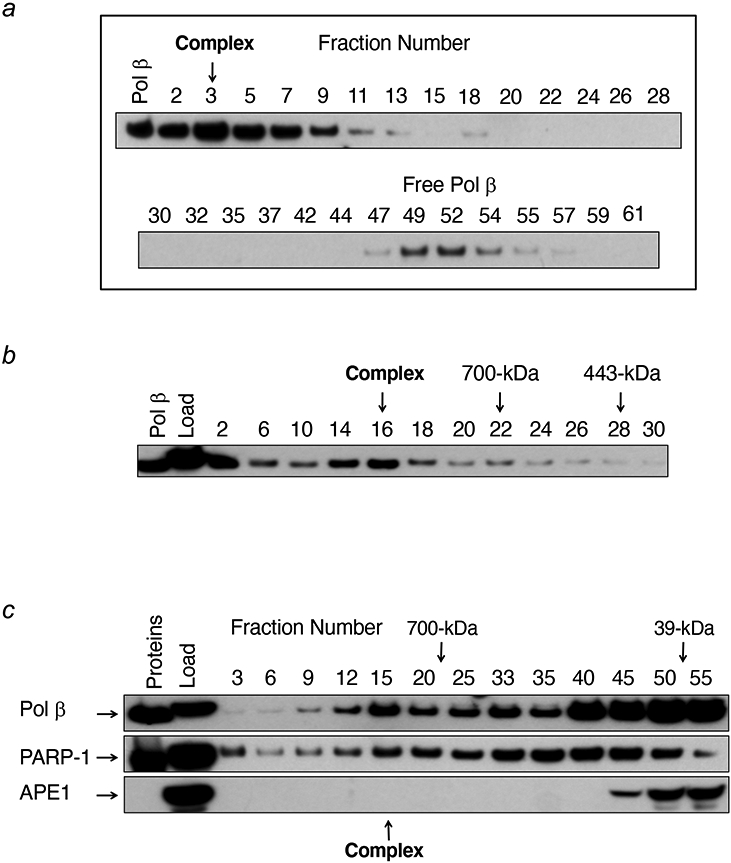

Several laboratories found that large multi-protein complexes of BER factors can be isolated from mammalian tissues and cell extracts (42, 61, 89, 90). These complexes were DNA free, depended on protein-protein interactions, and were stable enough to be analyzed by sucrose gradient centrifugation (61). Examples of this are illustrated in Figure 6. The BER complex isolated by affinity-chromatography contained PARP-1 and a complement of factors (e.g., Ligase III and XRCC1) necessary for in vitro BER (Figure 6c). Interestingly, many well-known BER factors were not recovered on the complex, including DNA glycosylases, APE1, and FEN1. Nonetheless, the concentration of this large BER complex in the initial cell extract appeared to be relatively modest. The large complex contained only a fraction of the total cellular level of these BER factors, since analysis of the crude extract (Figure 6c) revealed relatively abundant BER factors in lower molecular mass ranges (e.g., APE1), consistent with monomeric proteins or multi-molecular complexes of much lower mass than the large BER complex. In light of this and the absence of several critical factors in the large complex, the significance of this BER complex is not clear. One interpretation has been simply that the individual factors within the large complex have sufficient affinity for one another so as to assemble into a stable complex in the absence of a DNA lesion, and that in the presence of a DNA lesion, the large complex plus lower molecular mass factors can assemble at the lesion; and in the presence of a DNA lesion, additional factors might associate with the large complex and conduct repair. Thus, the large complex may be sufficient to recognize and handle repair of a basal level of BER lesions, along with recruitment of additional required factors such as DNA glycosylases, APE1 and FEN1. An alternate interpretation is that the isolated large complex may reflect a post lesion repair event where the complex that has been released from the repaired DNA and has partially disassembled.

Figure 6.

Sucrose density gradient centrifugation analyses of a large BER complex. (a) A BER complex isolated by affinity-capture chromatography with pol β as the bait was analyzed, and gradient fractions were probed by immunoblotting with anti-pol β antibody. The migration positions of the large BER complex and monomeric pol β are shown. (b) The results of re-centrifugation of the large BER complex using a more dense gradient than in (a). (c) Sucrose gradient analysis of the crude cell extract prior to affinity-capture chromatography; gradient fractions were probed by immunoblotting with the three antibodies shown. APE1 was not found in the gradient region containing the large BER complex and only a minor portion of pol β and PARP-1 were found in the large complex. Reproduced from Figure 2 (61).

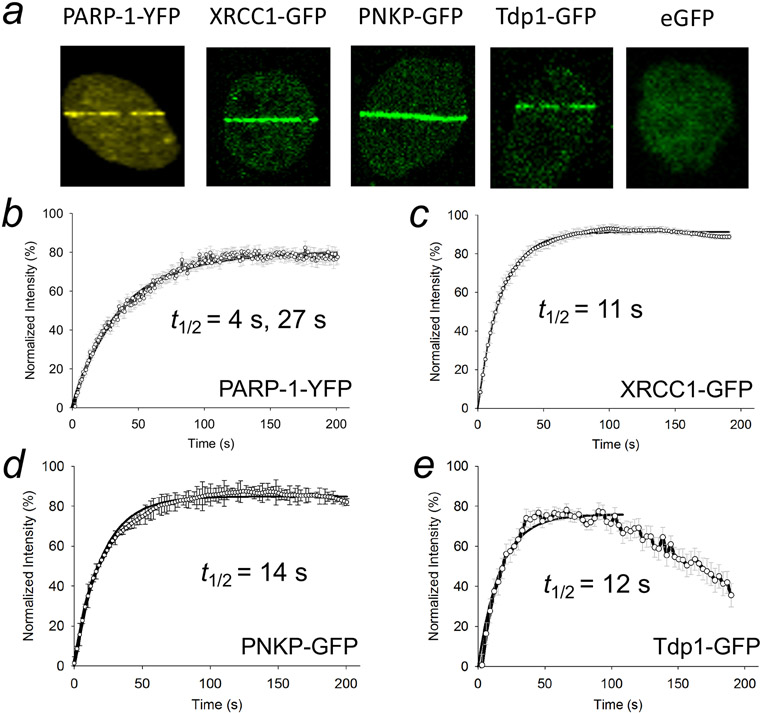

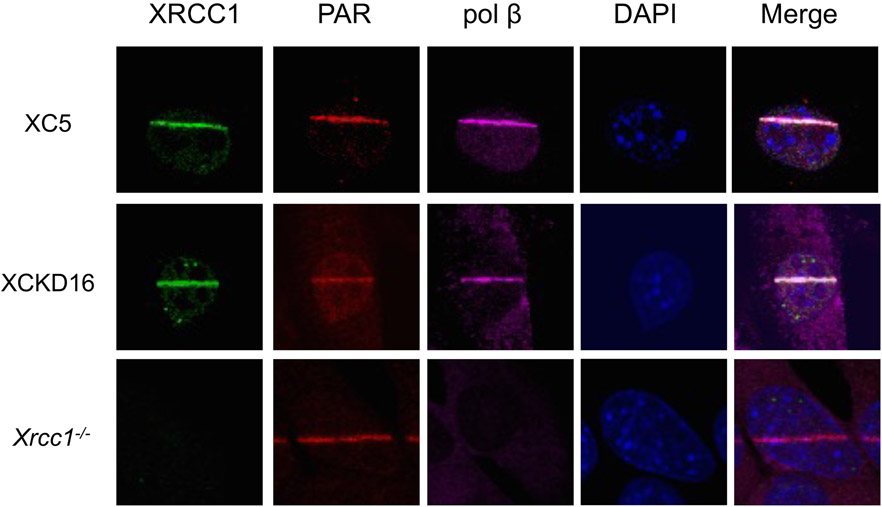

The observation of individual BER factors outside the large BER complex suggests these factors are available to respond to lesions and to participate in other cellular roles, as well. Thus, the factors not found in a large complex, such as the DNA glycosylases, APE1, and FEN1, could participate in repair on an individual transient basis by responding in a lesion-specific manner (42, 91). From cell imaging experiments (77, 92, 93) with fluorescently tagged BER factors, it is clear that BER enzymes are capable of dynamic flux at DNA lesions, as well as abundant accumulation in cellular organelles such as nucleoli. For example, BER factor recruitment at DNA lesions after laser micro-irradiation is well known (94, 95). Fluorescently-tagged BER factors PARP-1, XRCC1, PNKP, and Tdp1 rapidly and exponentially accumulate at laser-induced DNA damage in MEFs (Figure 7) and assessments of recruitment kinetic half-times at the damage sites are presented (96). As expected (92), PAR accumulation can also be observed at the lesions by immunofluorescence. These experiments illustrate that XRCC1 recruitment is dependent on PARylation and recruitment can be blocked by incubation with the PARP inhibitor veliparib (96). Pol β recruitment at a detectable level is dependent on XRCC1 expression (Figure 8). Mechanisms of controlling this rapid response and for regulating BER factor transport between cellular compartments and organelles are being investigated (97, 98).

Figure 7.

Time course of recruitment of transiently expressed carboxyl-terminal tagged repair proteins. Wild-type XRCC1 cells were subjected to micro-irradiation damage and recruitment followed for 200 s. (a) Typical accumulation of fluorescently tagged proteins and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) at damaged sites after 100 s repair. Recruitment curves for (b) PARP-1-YFP (YFP, yellow fluorescent protein) (c) XRCC1-GFP (d) PNKP-GFP and (e) Tdp1-GFP. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Fluorescence data were normalized using the intensity at the beginning of recruitment and maximal intensity values, and recruitment kinetics were fitted to single exponentials except for PARP-1-YFP that was fitted to two exponentials. The recruitment half-times are given in the appropriate panel. Adapted from Figure 2 (96).

Figure 8.

Immunofluorescent imaging of XRCC1, PAR and pol β. Cells were laser micro-irradiated in stripes to initiate XRCC1 and pol β recruitment and synthesis of PAR. After 1 min, cells were fixed and stained and a comparison of representative XC5 (XRCC1 wild-type), XCKD16 (XRCC1 mutated to prevent interaction with PNKP) and Xrcc1−/− cells is shown. Adapted from Figure 4 (96).

PNKP and APTX recruitment are dependent upon interactions with phosphorylated forms of XRCC1. XRCC1 interactions with these BER factors require casein kinase II-mediated phosphorylation of XRCC1 (99), and the interactions can be disrupted by mutation of the phosphorylation sites in XRCC1 (96, 100). Surprisingly, it was found that MEFs expressing an XRCC1 variant that is PNKP interaction-deficient still exhibited significant protection against camptothecin-induced cytotoxicity, despite the absence of detectable recruitment of PNKP under the conditions analyzed. These results suggested the presence of a PNKP-independent, but XRCC1-dependent, repair mechanism for Top1 DPCs (96). Beyond the requirement for XRCC1, the molecular mechanism of this protection against the camptothecin-induced DPC is unknown. As expected, cell lines expressing mutated XRCC1 unable to interact with APTX did not recruit APTX to laser-induced damage, and the cell extracts demonstrated minimal APTX deadenylation activity (5´-AMP removal) (100).

STEP-TO-STEP COORDINATION IN BER

As noted above, DNA repair intermediates such as the single-strand break can be cytotoxic because cellular detection of these repair intermediates can initiate signaling pathways leading to cell death. In this context, DNA repair factors must conceal repair intermediates that might lead to detrimental consequences. One cellular strategy for handling such BER intermediates is to channel them from one enzyme to the next in the sequential pathway before releasing the repaired DNA. In this scenario, the product of one reaction is the substrate for the subsequent reaction in the pathway and is passed along without releasing the product. Since many DNA glycosylases, APE1, and pol β (polymerase and lyase reactions) exhibit rapid chemistry and tight product binding (26, 34, 101), the enzyme-product complexes provide a barrier to signaling enzymes, as well as facilitating the next enzyme in the repair pathway. Thus, a delay in releasing a product that serves as substrate for the subsequent reaction provides an opportunity for the next enzyme to locate its substrate. In general, BER enzymes chemically modify their substrates rapidly even though product release limits enzyme cycling (i.e., product release is slow). Since DNA damage can occur in an array of DNA sequences (i.e., structures), the rapid chemical step may represent an enzyme’s “catalytic reserve” that can be utilized in a variety of DNA sequence contexts that may not be ideal for assembly of the active site. In other words, the enzymatic chemical step is modulated by DNA sequence effects, but still provides for tight product binding hastening hand-off to the next enzyme. As found with OGG1, this type of sequence context effect occurs when a mismatch is situated 5´ to 8-oxoG (29).

The assembly of multiple BER factors at a lesion site requires positional and kinetic step-to-step coordination to achieve efficient repair (102, 103). We proposed that these enzymes “channel repair intermediates,” where the product of the first enzyme is handed off to the next enzyme in the pathway before the first enzyme fully dissociates from the DNA. In support of this idea, we later found that sequential activities of single-nucleotide BER of an AP site (strand incision, dRP lyase, gap-filling DNA synthesis and DNA ligation) can be conducted in a “processive fashion” by a mixture of purified APE1, pol β and DNA ligase (102). A fraction of the product of each step was passed to the next step in the pathway without the enzyme dissociating from lesion-containing DNA. This series of reactions was referred to as “substrate channeling” (102, 103). In summary, the phenomenon of substrate channeling may explain how the multi-step BER process can occur while sequestering the toxic AP-site and strand break repair intermediates from cellular signaling systems.

REGULATION OF BER CAPACITY

Lesion Recognition

Mechanisms of lesion recognition by BER factors and other DNA enzymes are under active investigation. Once a target lesion is found within double-stranded DNA, the BER enzyme structurally alters the DNA exposing the region to be altered and facilitating active site assembly. However, initial lesion recognition presents several challenges for BER enzymes. First, lesions are imbedded in a vast excess of DNA forcing the enzyme to employ a means of efficiently distinguishing a lesion (104); second, lesions are protected from recognition by repair enzymes through DNA/protein complexes, chromatin structures, or non-B form structures (e.g., G-quadruplexes). In studies of restriction enzymes and DNA glycosylases, such as UDG (105-107), processive searching along DNA by scanning or sliding has long been recognized as an important mechanism of lesion recognition. A variation of this is termed hopping (108), where an enzyme maintains a processive search without complete dissociation from the duplex DNA and where the enzyme can interrogate both DNA strands. Another search mechanism without complete dissociation from DNA is termed “jumping” where an enzyme can jump from one DNA segment to another without complete dissociation. Examples of this was found in studies of UDG (105-107) and alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (AAG) (109, 110) in the Stivers and O’Brien laboratories, respectively. They designed substrates in different oligonucleotides that were connected only by a non-DNA tether. This allowed them to reveal AAG’s capacity to conduct a relatively long-range, but processive, DNA searching process they termed “jumping.”

Studies of pol β lesion recognition revealed that single-nucleotide gap searching occurs by a processive scanning mechanism along duplex DNA (111). Lysine residues important for 5´-phosphate recognition in the lyase domain were found to be essential for scanning. In general, the results with pol β were similar to those reported for UDG (105, 106) and AAG (109, 110), and the findings on processive searching included the presence of “jumping” capacity. We also examined the question of processive searching within the nucleosome core particle. Gaps were strategically positioned many nucleotides from one another in the nucleosome core particle. Processive searching was not found with the nucleosome substrate (112). Thus, pol β lesion recognition within the nucleosome core particle was strongly hindered as is overall BER (108). The implications of these in vitro findings regarding lesion recognition and repair in vivo point to the importance of understanding nucleosome remodeling and repositioning across the genome (113, 114).

In cases of accumulation of toxic repair intermediates, BER overlaps with cell cycle checkpoint and cell death signaling mechanisms as well as other DNA repair systems. Thus, to avoid the possibility of a limiting concentration of a BER enzyme acting at one BER step or another, expression control of BER factors has been considered a priority for the cell. Even though mammalian cells maintain a constitutive level of BER capacity, cells respond to stress by altering gene expression and most importantly by conducting posttranslational modifications of BER factors (115, 116), so as to increase a localized repair capacity. These responses have been known as the “adaptive response” from early work in both prokaryotic (117-120) and eukaryotic (121-124) systems. Therefore, the notion emerged that DNA repair is under dynamic regulation, and this phenomenon has been studied extensively and elegantly confirmed for the nucleotide excision DNA repair (NER) pathway (125, 126). In studies of the BER pathway, up- and down-regulation of gene expression at the messenger RNA level has been observed in mammalian cells after exposure to a DNA alkylating agent or to an oxidative stress-inducing agent (127), and up-regulation of pol β protein expression was found to protect cells against oxidatively-induced cytotoxicity in a model cell culture system (128); similar observations with up-regulation of APE1 protein expression were made by Mitra and associates (129). However, the global mechanisms and signaling involved in regulation of BER enzyme gene expression are difficult to assess and this topic requires further work (e.g., see (127)).

PERSPECTIVES

Integration Across Different Approaches

Historically, a challenge in DNA repair research has been integrating results from traditional biochemical approaches with results from genetic and cell biology approaches, and such integration remains a challenge today. Beyond scanning for evolutionary conservation, biological validation of information obtained through biochemical approaches has been an important strategy in DNA repair research. Yet, in light of the extensive redundancy in individual BER factors themselves and in DNA repair pathway overlap, it has often been difficult to use genetic approaches to validate a biological function of a repair factor. Fortunately, with advances in techniques such as recombinant protein expression and better methods for characterizing repair factors, integration across genetic and biological approaches has been expedited. Important emerging tools for characterizing BER factors include better antibodies, sophisticated protein chemistry, enzyme kinetic and biophysical techniques, X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and various computational approaches. In addition, cellular imaging approaches are revealing surprises about BER protein dynamics in response to DNA damage and other stressors.

Nevertheless, examples of the integration challenge abound, such as in cases where biochemical results with an evolutionarily conserved novel protein point to a role in DNA repair, yet genetic experiments with a deletion for the protein fail to reveal a repair deficiency phenotype. This scenario, which is common in BER research, can be explained by recognizing protein factor redundancy/complementation or the occurrence of alternate repair pathways capable of repairing the same lesion. For example, cellular cytotoxicity and mutagenesis from the oxidatively-induced 8-oxoG base can be observed with deletion of OGG1; but, this observation generally requires a cellular background deficient in NER and/or mismatch repair (MMR) pathways, both of which can repair the 8-oxoG lesion (130-135). In spite of the inherent complexity, this functional redundancy appears to be a common biological feature.

In considering examples of similar challenges, genetic studies can reveal unexpected phenotypes, that are not evident from studies in prokaryotic and invertebrate systems. Studies of both the Nei-like DNA glycosylase 1 (NEIL1) and OGG1 knock-out mouse models by Lloyd and associates (136-140) illustrate an example of this phenomenon. Although the NEIL1 knock-out mouse displayed a modest tendency to develop hepatocellular carcinomas (139), that is greatly enhanced in an Endonuclease III-like protein 1 (NTH1) knock-out background (141), the most striking feature for this DNA glycosylase-deficient mice model is a propensity to develop metabolic syndrome (136-140). This mouse disease manifestation was initially considered puzzling in relationship to BER, and possibly limited the murine model. However, humans expressing polymorphic variants of OGG1 were found to have a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes and obesity (142, 143). The fundamental mechanism underlying the relationship between deficiencies in BER of oxidatively-induced base damage and the observed metabolic dysregulation in the mouse is currently not well understood. Yet, roles of BER in mitochondrial versus nuclear genomes may provide information in clarifying this unanticipated array of phenotypes.

Another example of a similar phenomenon comes from studies with a pol β mouse model utilized by Sweasy and associates (144, 145). In this case, pol β deficient mice exhibit an immunological deficiency that was not predicted from studies of cultured cells and lower organisms or from the known BER related biochemical properties of this enzyme. Nevertheless, with knowledge of the mouse phenotype in hand, further studies revealed that an immunological deficiency may be explained in the context of the DNA repair enzymatic activity of pol β (146). Finally, more work will be required to understand ways to more accurately bridge results obtained from biochemical and model organism studies with disease related studies in the more complex biological systems.

An equally challenging problem has been correlating multiprotein complexes revealed by biochemical studies utilizing cell extracts, with the multiprotein assemblies observed by cellular imaging techniques at sites of induced DNA damage in cultured cells. For example, in many cases purified proteins have been found to interact in biochemical studies, but whether or not the interaction is biologically relevant to DNA repair in vivo remains unclear. Progress is being made toward developing techniques to address this problem (147), even though much more innovative work is needed. For example, the emerging use of techniques to measure molecular interactions under equilibrium conditions in solution has been successful, as are techniques to measure dynamics of individual factors and complexes in living cells (148).

Another difficult problem is correlating results from biophysical and crystallography approaches with enzyme kinetic analyses. Structures revealing enzyme active sites, or even pre-catalytic enzyme-substrate interactions, are assumed to provide a basis for understanding mechanistic information about transition states and/or rate-limiting steps. But, cases where these assumptions have been well documented are rare (26). Nevertheless, interpretations of DNA repair enzyme crystal structures have been enhanced by the use of computational methods and by new crystallography techniques providing better resolution (149, 150). The application of time-lapse crystallography has offered surprises about reaction intermediates that had been hidden until recently (151).

Opportunities in Understanding BER Coordination

Recent results have pointed to a role of DNA polymerases in mediating ligation by mammalian DNA ligases. Using coupled DNA polymerase and ligase reactions, it was found that ligation failure, i.e., 5-adenylation of the substrate, can be regulated by a DNA polymerase (59). Further work is needed to understand the molecular basis of this effect. Other examples of accessory factor stimulation of enzymatic activities are known in the BER pathway. For example, APE1 was found to stimulate the steady-state activity of DNA glycosylases (152) and the dRP lyase activity of pol β (91). Similarly, PARP-1 was found to stimulate the AP-site steady-state strand incision activity of APE1 (60). As reviewed recently (108), these stimulatory effects may not depend on direct protein-protein interactions between the BER factors. Instead, enzyme activity stimulation may hinge upon increasing the product release step through altered DNA lesion interactions. For example, this could explain PARP-1 stimulation of APE1 strand incision, but depends on a proposed DNA scanning process where both proteins are associated with and scanning the DNA in the vicinity of the reaction product (108). In this way, as a BER enzyme alters its interaction with its DNA product in preparation for dissociation from the repair intermediate, the subsequent enzyme will be in the vicinity of its substrate and poised to bind to it. Accordingly, the subsequent enzyme captures a conformation of the repair intermediate that deters binding by the previous enzyme thereby hastening its dissociation. Measurement of the individual rate constants and identification of the enzyme/DNA intermediates for these dynamic enzyme/DNA binding events will be required to shed light on this proposed mechanism.

Mitochondrial BER

Our laboratory and collaborators recently found that pol β is associated with mammalian mitochondria (153), and similar findings were independently reported Bohr and associates (154). Assays of in vitro BER activity in extracts from mitochondria purified from HEK293 cells and MEF cells revealed that pol β was responsible for most of the BER DNA polymerase function of the extract. Elimination of pol β using a specific neutralizing antibody or a cellular gene deletion resulted in a very strong reduction in BER activity (153). These results and others point to a role of pol β in mitochondrial DNA repair (155). Further work will be required to understand the implications of pol β mediated BER in light of the presence of multiple DNA polymerases in mammalian mitochondria, including replicative pol γ (156), Primpol (157, 158) and pol θ (159, 160).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We apologize to our colleagues that much of the primary literature in this diverse field could not be cited because of space limitations. Molecular graphics images were produced using the Chimera package from the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIH P41 RR-01081). This research was supported by Research Project Numbers Z01-ES050158 and Z01-ES050159 to SHW in the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Sancar A 2003. Structure and function of DNA photolyase and cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptors. Chem. Rev 103: 2203–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sancar A 2004. In Adv. Protein Chem, pp. 73–100: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindahl T 1982. DNA repair enzymes. Ann. Rev. Biochem 51: 61–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindahl T, Demple B, Robins P. 1982. Suicide inactivation of the E. coli O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. EMBO J. 1: 1359–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitra S, Pal BC, Foote RS. 1982. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in wild-type and ada mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol 152: 534–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tano K, Shiota S, Collier J, Foote RS, Mitra S. 1990. Isolation and structural characterization of a cDNA clone encoding the human DNA repair protein for O6-alkylguanine. PNAS 87: 686–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antoniali G, Malfatti MC, Tell G. 2017. Unveiling the non-repair face of the base excision repair pathway in RNA processing: A missing link between DNA repair and gene expression? DNA Repair 56: 65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David SS, O'Shea VL, Kundu S. 2007. Base-excision repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nature 447: 941–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drohat AC, Coey CT. 2016. Role of base excision “repair” enzymes in erasing epigenetic marks from DNA. Chem. Rev 116: 12711–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krokan HE, Bjørås M. 2013. Base Excision Repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5: a012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson AB, Klungland A, Rognes T, Leiros I. 2009. DNA repair in mammalian cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66: 981–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace SS. 2014. Base excision repair: A critical player in many games. DNA Repair 19: 14–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitaker AM, Schaich MA, Smith MR, Flynn TS, Freudenthal BD. 2017. Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage: From mechanism to disease. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 22: 1493–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chastain PD, Nakamura J, Rao S, Chu H, Ibrahim JG, et al. 2010. Abasic sites preferentially form at regions undergoing DNA replication. FASEB J. 24: 3674–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura J, Swenberg JA. 1999. Endogenous apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in genomic DNA of mammalian tissues. Cancer Res. 59: 2522–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klungland A, Rosewell I, Hollenbach S, Larsen E, Daly G, et al. 1999. Accumulation of premutagenic DNA lesions in mice defective in removal of oxidative base damage. PNAS 96: 13300–05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl T 1993. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature 362: 709–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loeb LA. 1985. Apurinic sites as mutagenic intermediates. Cell 40: 483–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad R, Dianov GL, Bohr VA, Wilson SH. 2000. FEN1 stimulation of DNA polymerase β mediates an excision step in mammalian long patch base excision repair. J. Biol. Chem 275: 4460–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou EW, Prasad R, Asagoshi K, Masaoka A, Wilson SH. 2007. Comparative assessment of plasmid and oligonucleotide DNA substrates in measurement of in vitro base excision repair activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Ballin JD, Della-Maria J, Tsai M-S, White EJ, et al. 2009. Distinct kinetics of human DNA ligases I, IIIα, IIIβ, and IV reveal direct DNA sensing ability and differential physiological functions in DNA repair. DNA Repair 8: 961–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fortini P, Dogliotti E. 2007. Base damage and single-strand break repair: Mechanisms and functional significance of short- and long-patch repair subpathways. DNA Repair 6: 398–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zharkov D 2008. Base excision DNA repair. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65: 1544–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caldecott KW. 2008. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet 9: 619–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace SS. 2013. DNA glycosylases search for and remove oxidized DNA bases. Environ. Mol. Mutagen 54: 691–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parikh SS, Walcher G, Jones GD, Slupphaug G, Krokan HE, et al. 2000. Uracil-DNA glycosylase-DNA substrate and product structures: Conformational strain promotes catalytic efficiency by coupled stereoelectronic effects. PNAS 97: 5083–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mol CD, Arvai AS, Slupphaug G, Kavli B, Alseth I, et al. 1995. Crystal structure and mutational analysis of human uracil-DNA glycosylase: Structural basis for specificity and catalysis. Cell 80: 869–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parikh SS, Mol CD, Slupphaug G, Bharati S, Krokan HE, Tainer JA. 1998. Base excision repair initiation revealed by crystal structures and binding kinetics of human uracil-DNA glycosylase with DNA. EMBO J 17: 5214–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sassa A, Beard WA, Prasad R, Wilson SH. 2012. DNA sequence context effects on the glycosylase activity of human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem 287: 36702–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong I, Lundquist AJ, Bernards AS, Mosbaugh DW. 2002. Presteady-state analysis of a single catalytic turnover by Escherichia coli uracil-DNA glycosylase reveals a “pinch-pull-push” mechanism. J. Biol. Chem 277: 19424–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beard WA, Batra VK, Wilson SH. 2010. DNA polymerase structure-based insight on the mutagenic properties of 8-oxoguanine. Mutat. Res 703: 18–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez Y, Howard MJ, Cuneo MJ, Prasad R, Wilson SH. 2017. Unencumbered pol β lyase activity in nucleosome core particles. Nucleic Acids Res. 45: 8901–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanazhevskaya LY, Koval VV, Vorobjev YN, Fedorova OS. 2012. Conformational dynamics of abasic DNA upon interactions with AP endonuclease 1 revealed by stopped-flow fluorescence analysis. Biochemistry 51: 1306–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maher RL, Bloom LB. 2007. Pre-steady-state kinetic characterization of the AP endonuclease activity of human AP endonuclease 1. J. Biol. Chem 282: 30577–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schermerhorn KM, Delaney S. 2013. Transient-state kinetics of apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease 1 acting on an authentic AP site and commonly used substrate analogs: The effect of diverse metal ions and base mismatches. Biochemistry 52: 7669–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freudenthal BD, Beard WA, Cuneo MJ, Dyrkheeva NS, Wilson SH. 2015. Capturing snapshots of APE1 processing DNA damage. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 22: 924–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu W-J, Yang W, Tsai M-D. 2017. How DNA polymerases catalyse replication and repair with contrasting fidelity. Nat. Rev. Chem 1: 0068 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lovett ST. 2017. Template-switching during replication fork repair in bacteria. DNA Repair 56: 118–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beard WA, Wilson SH. 2014. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase β. Biochemistry 53: 2768–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasad R, Batra VK, Yang X-P, Krahn JM, Pedersen LC, et al. 2005. Structural insight into the DNA polymertase β deoxyribose phosphate lyase mechanism. DNA Repair 4: 1347–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelletier H, Sawaya MR. 1996. Characterization of the metal ion binding helix-hairpin-helix motifs in human DNA polymerase β by X-ray structural analysis. Biochemistry 35: 12778–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Beard WA, Shock DD, Prasad R, Hou EW, Wilson SH. 2005. DNA Polymerase β and flap endonuclease 1 enzymatic specificities sustain DNA synthesis for long patch base excision repair. J. Biol. Chem 280: 3665–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prasad R, Beard WA, Chyan JY, Maciejewski MW, Mullen GP, Wilson SH. 1998. Functional analysis of the amino-terminal 8-kDa domain of DNA polymerase β as revealed by site-directed mutagenesis: DNA binding and 5'-deoxyribose phosphate lyase activities. J. Biol. Chem 273: 11121–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelletier H, Sawaya MR, Wolfle W, Wilson SH, Kraut J. 1996. Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase β complexed with DNA: Implications for catalytic mechanism, processivity, and fidelity. Biochemistry 35: 12742–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beard WA, Shock DD, Wilson SH. 2004. Influence of DNA structure on DNA polymerase β active site function: Extension of mutagenic DNA intermediates. J. Biol. Chem 279: 31921–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sobol RW, Horton JK, Kühn R, Gu H, Singhal RK, et al. 1996. Requirement of mammalian DNA polymerase β in base excision repair. Nature 379: 183–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braithwaite EK, Prasad R, Shock DD, Hou EW, Beard WA, Wilson SH. 2005. DNA polymerase λ mediates a back-up base excision repair activity in extracts of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem 280: 18469–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tano K, Nakamura J, Asagoshi K, Arakawa H, Sonoda E, et al. 2007. Interplay between DNA polymerases β and λ in repair of oxidation DNA damage in chicken DT40 cells. DNA Repair 6: 869–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vermeulen C, Bertocci B, Begg AC, Vens C. 2007. Ionizing radiation sensitivity of DNA polymerase lambda-deficient cells. Radiat. Res 168: 683–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.García-Díaz M, Domínguez O, López-Fernández LA, de Lera LT, Saníger ML, et al. 2000. DNA polymerase lambda (pol λ), a novel eukaryotic DNA polymerase with a potential role in meiosis. J. Mol. Biol 301: 851–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moon AF, Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Davis BJ, Zhong X, et al. 2007. Structural insight into the substrate specificity of DNA polymerase μ. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 14: 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batra VK, Beard WA, Shock DD, Krahn JM, Pedersen LC, Wilson SH. 2006. Magnesium induced assembly of a complete DNA polymerase catalytic complex. Structure 14: 757–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Krahn JM, Kunkel TA, Pedersen LC. 2005. A closed conformation for the pol λ catalytic cycle. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 12: 97–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loc'h J, Rosario S, Delarue M. 2016. Structural basis for a new templated activity by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: Implications for V(D)J recombination. Structure 24: 1452–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia-Díaz M, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA, Blanco L. 2001. Identification of an intrinsic 5'-deoxyribose-5-phosphate lyase activity in human DNA polymerase λ: A possible role in base excision repair. J. Biol. Chem 276: 34659–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bienstock RJ, Beard WA, Wilson SH. 2014. Phylogenetic analysis and evolutionary origins of DNA polymerase X-family members. DNA Repair 22: 77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ellenberger TA, Tomkinson AE. 2008. Eukaryptic DNA ligases: Structural and functional insights. Ann. Rev. Biochem 77: 313–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Çağlayan M, Horton JK, Dai D-P, Stefanick DF, Wilson SH. 2017. Oxidized nucleotide insertion by pol β confounds ligation during base excision repair. Nat. Commun 8: 14045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Çağlayan M, Wilson SH. 2018. Pol mu dGTP mismatch insertion opposite T coupled with ligation reveals promutagenic DNA repair intermediate. Nat. Commun 9: 4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prasad R, Singhal RK, Srivastava DK, Molina JT, Tomkinson AE, Wilson SH. 1996. Specific interaction of DNA polymerase β and DNA ligase I in a multiprotein base excision repair complex from bovine testis. J. Biol. Chem 271: 16000–07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prasad R, Williams JG, Hou EW, Wilson SH. 2012. Pol β associated complex and base excision repair factors in mouse fibroblasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: 11571–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Srivastava DK, Vande Berg BJ, Prasad R, Molina JT, Beard WA, et al. 1998. Mammalian abasic site base excision repair: Identification of the reaction sequence and rate-determining steps. J. Biol. Chem 273: 21203–09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caldecott KW, McKeown CK, Tucker JD, Ljungquist S, Thompson LH. 1994. An interaction between the mammalian DNA repair protein XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Mol. Cell. Biol 14: 68–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lakshmipathy U, Campbell C. 1999. The human DNA ligase III gene encodes nuclear and mitochondrial proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol 19: 3869–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gao Y, Katyal S, Lee Y, Zhao J, Rehg JE, et al. 2011. DNA ligase III is critical for mtDNA integrity but not Xrcc1-mediated nuclear DNA repair. Nature 471: 240–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simsek D, Furda A, Gao Y, Artus J, Brunet E, et al. 2011. Crucial role for DNA ligase III in mitochondria but not in Xrcc1-dependent repair. Nature 471: 245–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hassa O, Hottiger MO. 2008. The diverse biological roles of mammalian PARPS, a small but powerful family of poly-ADP-ribose polymerases. Front. Biosci 13: 3046–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schreiber V, Dantzer F, Ame J-C, de Murcia G. 2006. Poly(ADP-ribose): Novel functions for an old molecule. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 7: 517–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Murcia G, Ménissier de Murcia J. 1994. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: a molecular nick-sensor. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19: 172–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.D'Amours D, Desnoyers S, D'Silva I, Poirier GG. 1999. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem. J 342: 249–68 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prasad R, Horton JK, Chastain PD, Gassman NR, Freudenthal BD, et al. 2014. Suicidal cross-linking of PARP-1 to AP site intermediates in cells undergoing base excision repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: 6337–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ganguly B, Dolfi SC, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Ganesan S, Hirshfield KM. 2016. Role of biomarkers in the development of PARP inhibitors. Biomark. Cancer 8: 15–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rouleau M, Patel A, Hendzel MJ, Kaufmann SH, Poirier GG. 2010. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10: 293–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murai J, Marchand C, Shahane SA, Sun H, Huang R, et al. 2014. Identification of novel PARP inhibitors using a cell-based TDP1 inhibitory assay in a quantitative high-throughput screening platform. DNA Repair 21: 177–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Horton JK, Wilson SH. 2013. Predicting enhanced cell killing through PARP inhibition. Mol. Cancer Res. 11: 13–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Horton JK, Stefanick DF, Prasad R, Gassman NR, Kedar PS, Wilson SH. 2014. Base excision repair defects invoke hypersensitivity to PARP inhibition. Mol. Cancer Res. 12: 1128–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gassman NR, Wilson SH. 2015. Micro-irradiation tools to visualize base excision repair and single-strand break repair. DNA Repair 31: 52–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cuneo MJ, London RE. 2010. Oxidation state of the XRCC1 N-terminal domain regulates DNA polymerase β binding affinity. PNAS 107: 6805–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Horton JK, Seddon HJ, Zhao M-L, Gassman NR, Janoshazi AK, et al. 2017. Role of the oxidized form of XRCC1 in protection against extreme oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med 107: 292–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Horton JK, Stefanick DF, Gassman NR, Williams JG, Gabel SA, et al. 2013. Preventing oxidation of cellular XRCC1 affects PARP-mediated DNA damage responses. DNA Repair 12: 774–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Horton JK, Gassman NR, Dunigan BD, Stefanick DF, Wilson SH. 2015. DNA polymerase β-dependent cell survival independent of XRCC1 expression. DNA Repair 26: 23–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prasad R, Beard WA, Strauss PR, Wilson SH. 1998. Human DNA polymerase β deoxyribose phosphate lyase: Substrate specificity and catalytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem 273: 15263–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Çağlayan M, Batra VK, Sassa A, Prasad R, Wilson SH. 2014. Role of polymerase β in complementing aprataxin deficiency during abasic-site base excision repair. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 21: 497–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Whitehouse CJ, Taylor RM, Thistlethwaite A, Zhang H, Karimi-Busheri F, et al. 2001. XRCC1 stimulates human polynucleotide kinase activity at damaged DNA termini and accelerates DNA single-strand break repair. Cell 104: 107–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chou K-M, Kukhanova M, Cheng Y-C. 2000. A novel action of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease: Excision of L-configuration deoxyribonucleoside analogs from the 3' termini of DNA. J. Biol. Chem 275: 31009–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Whitaker AM, Flynn TS, Freudenthal BD. 2018. Molecular snapshots of APE1 proofreading mismatches and removing DNA damage. Nat. Commun 9: 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Interthal H, Chen HJ, Champoux JJ. 2005. Human Tdp1 cleaves a broad spectrum of substrates, including phosphoamide linkages. J. Biol. Chem 280: 36518–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ledesma FC, El Khamisy SF, Zuma MC, Osborn K, Caldecott KW. 2009. A human 5′-tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase that repairs topoisomerase-mediated DNA damage. Nature 461: 674–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Das A, Wiederhold L, Leppard JB, Kedar P, Prasad R, et al. 2006. NEIL2-initiated, APE-independent repair of oxidized bases in DNA: Evidence for a repair complex in human cells. DNA Repair 5: 1439–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hanssen-Bauer A, Solvang-Garten K, Sundheim O, Peña-Diaz J, Andersen S, et al. 2011. XRCC1 coordinates disparate responses and multiprotein repair complexes depending on the nature and context of the DNA damage. Environ. Mol. Mutagen 52: 623–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu Y, Prasad R, Beard WA, Kedar PS, Hou EW, et al. 2007. Coordination of steps in single-nucleotide base excision repair mediated by apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 and DNA polymerase β. J. Biol. Chem 282: 13532–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lan L, Nakajima S, Oohata Y, Takao M, Okano S, et al. 2004. In situ analysis of repair processes for oxidative DNA damage in mammalian cells. PNAS 101: 13738–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iyama T, Wilson DM. 2016. Elements That Regulate the DNA Damage Response of Proteins Defective in Cockayne Syndrome. J. Mol. Biol 428: 62–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abdou I, Poirier GG, Hendzel MJ, Weinfeld M. 2015. DNA ligase III acts as a DNA strand break sensor in the cellular orchestration of DNA strand break repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 875–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Campalans A, Kortulewski T, Amouroux R, Menoni H, Vermeulen W, Radicella JP. 2013. Distinct spatiotemporal patterns and PARP dependence of XRCC1 recruitment to single-strand break and base excision repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: 3115–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Horton JK, Stefanick DF, Zhao M-L, Janoshazi AK, Gassman NR, et al. 2017. XRCC1-mediated repair of strand breaks independent of PNKP binding. DNA Repair 60: 52–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Antoniali G, Lirussi L, Poletto M, Tell G. 2013. Emerging roles of the nucleolus in regulating the DNA damage response: The noncanonical DNA repair enzyme APE1/Ref-1 as a paradigmatical example. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20: 621–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bauer NC, Doetsch PW, Corbett AH. 2015. Mechanisms regulating protein localization. Traffic 16: 1039–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kubota Y, Takanami T, Higashitani A, Horiuchi S. 2009. Localization of X-ray cross complementing gene 1 protein in the nuclear matrix is controlled by casein kinase II-dependent phosphorylation in response to oxidative damage. DNA Repair 8: 953–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Horton JK, Stefanick DF, Çağlayan M, Zhao M-L, Janoshazi AK, et al. 2018. XRCC1 phosphorylation affects aprataxin recruitment and DNA deadenylation activity. DNA Repair 64: 26–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vande Berg BJ, Beard WA, Wilson SH. 2001. DNA structure and aspartate 276 influence nucleotide binding to human DNA polymerase β: Implication for the identity of the rate-limiting conformational change. J. Biol. Chem 276: 3408–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Prasad R, Shock DD, Beard WA, Wilson SH. 2010. Substrate channeling in mammalian base excision repair pathways: Passing the baton. J. Biol. Chem 285: 40479–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wilson SH, Kunkel TA. 2000. Passing the baton in base excision repair. Nat. Struct. Biol 7: 176–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Berg OG, Winter RB, Von Hippel PH. 1981. Diffusion-driven mechanisms of protein translocation on nucleic acids. 1. Models and theory. Biochemistry 20: 6929–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Parker JB, Bianchet MA, Krosky DJ, Friedman JI, Amzel LM, Stivers JT. 2007. Enzymatic capture of an extrahelical thymine in the search for uracil in DNA. Nature 449: 433–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schonhoft JD, Kosowicz JG, Stivers JT. 2013. DNA translocation by human uracil DNA glycosylase: Role of DNA phosphate charge. Biochemistry 52: 2526–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Esadze A, Stivers JT. 2018. Facilitated diffusion mechanisms in DNA base excision repair and transcriptional activation. Chem. Rev 118: 11298–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Howard MJ, Wilson SH. 2018. DNA scanning by base excision repair enzymes and implications for pathway coordination. DNA Repair 71: 101–07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hedglin M, Zhang Y, O'Brien PJ. 2013. Isolating contributions from intersegmental transfer to DNA searching by alkyladenine DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem 288: 24550–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hedglin M, Zhang Y, O’Brien PJ. 2015. Probing the DNA structural requirements for facilitated diffusion. Biochemistry 54: 557–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Howard MJ, Wilson SH. 2017. Processive searching ability varies among members of the gap-filling DNA polymerase X family. J. Biol. Chem 292: 17473–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Howard MJ, Rodriguez Y, Wilson SH. 2017. DNA polymerase β uses its lyase domain in a processive search for DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 45: 3822–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mao P, Brown AJ, Malc EP, Mieczkowski PA, Smerdon MJ, et al. 2017. Genome-wide maps of alkylation damage, repair, and mutagenesis in yeast reveal mechanisms of mutational heterogeneity. Genome Res. 27: 1674–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rodriguez Y, Hinz JM, Smerdon MJ. 2015. Accessing DNA damage in chromatin: Preparing the chromatin landscape for base excision repair. DNA Repair 32: 113–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Breslin C, Hornyak P, Ridley A, Rulten SL, Hanzlikova H, et al. 2015. The XRCC1 phosphate-binding pocket binds poly (ADP-ribose) and is required for XRCC1 function. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 6934–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Loizou JI, El-Khamisy SF, Zlatanou A, Moore DJ, Chan DW, et al. 2004. The protein kinase CK2 facilitates repair of chromosomal DNA single-strand breaks. Cell 117: 17–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cairns J, Robins P, Sedgwick B, Talmud P. 2981. The inducible repair of alkylated DNA. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol 26: 237–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Demple B, Harrison L. 1994. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: Enzymology and biology. Ann. Rev. Biochem 63: 915–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lindahl T, Sedgwick B, Sekiguchi M, Nakabeppu Y. 1988. Regulation and expression of the adaptive response to alkylating agents. Ann. Rev. Biochem 57: 133–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]