Abstract

SINE-VNTR-Alu retrotransposons represent one class of transposable elements which contribute to the regulation and evolution of the primate genome and have the potential to be involved in genetic instability and disease progression. However, these polymorphic elements have not been extensively analysed when addressing the missing heritability of neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). SVA_67, a retrotransposon insertion polymorphism, is located in a 1.8 Mb region of high linkage disequilibrium, called the MAPT locus, which is known to contribute to increased risk of developing PD, frontotemporal dementia and other tauopathies. To investigate the role of SVA_67 in directing differential gene expression at this locus, we characterised the impact of SVA_67 allele dosage on isoform expression of several genes in the MAPT locus using the datasets from both the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative and New York Genome Center Consortium Target ALS cohort. The Parkinson’s data was from gene expression in the blood and the ALS data from a variety of CNS regions and allowed us to demonstrate that SVA_67 presence or absence correlated with both isoform- and tissue-specific expression of multiple genes at this locus. This study highlights the importance of addressing SVA polymorphism in disease genetics to gain insight into a better understanding of the role of these regulatory domains to a variety of neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: transposable elements, MAPT, tau, Parkinson’s disease, ALS, FTD, motor neuron disease, SVA

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), are complex disorders involving interaction of genetic and environmental factors (Emamzadeh and Surguchov, 2018). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and targeted single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) studies have allowed the identification of many loci and genetic mutations and polymorphisms associated with these diseases (Taylor et al., 2016; van Rheenen et al., 2016; Nalls et al., 2019; Blauwendraat et al., 2020). However, further analyses are needed to characterise and identify the source of the current missing heritability of these diseases.

Non-coding repetitive DNA is often an overlooked source of genetic variation. Repetitive DNA can be found in both static and mobile forms, whereby transposable elements (TEs) belonging to the latter class are capable of mobilising throughout the genome (Bourque et al., 2018). Originally dismissed as “junk” DNA, TEs are now known to contribute to the regulation and evolution of the genome as well as to be involved in genetic instability and disease progression (Ayarpadikannan and Kim, 2014). Based on their transposition strategy and intermediates formed, TEs are split into two families named DNA transposons and retrotransposons (Savage et al., 2019). Retrotransposon sequences can propagate via a “copy-and-paste” mechanism leading to a new copy at a new genomic locus of the host genome (Elbarbary et al., 2016). SINE-VNTR-Alu (SVA) elements, approximately 0.7–4 kb in length, are one member of the non-LTR (long terminal repeat) retrotransposon family with 2,700–3,000 copies present in the reference human genome. They consist of a 5′ CT-rich hexamer domain (CT element), an antisense Alu-like region, a central GC-rich variable number tandem repeat (VNTR, each repeat typically 30–50 bp in length), a SINE-R domain and a 3′ poly A tail (Figure 1A; Hancks and Kazazian, 2010; Gianfrancesco et al., 2017). SVAs, classified A–F in order of evolutionary age based on their SINE region (Wang et al., 2005), are important contributors to genetic diversity by a variety of mechanisms which include acting as transcriptional regulatory domains and thus modulating gene expression profiles, for instance, by transcription factor (TF) binding or altering patterns of methylation (Hancks et al., 2011). Ongoing mobilisation of SVAs has led to insertions being polymorphic for their presence or absence and are thus named retrotransposon insertion polymorphisms (RIPs) (Hancks and Kazazian, 2016; Gianfrancesco et al., 2019). It should be noted that the evolutionarily youngest classes of SVAs (D-F1) may be of special interest for human physiology, health and evolution since they have introduced hominid-specific insertions which can exert novel regulatory potential to specific genomic loci (Vasieva et al., 2017).

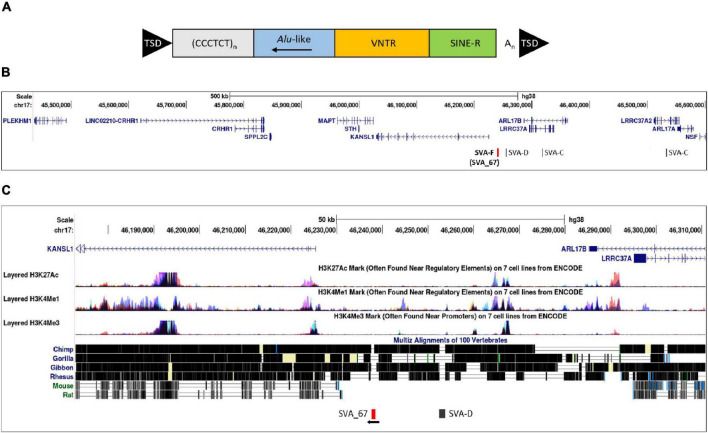

FIGURE 1.

Structure of a full-length SVA and schematic representation of the location of SVA_67. (A) A typical SVA element (full-length) contains five domains. Considered 5′–3′, SVAs are composed of a (CCCTCT)n hexamer repeat, an inverted Alu-like region, a GC-rich variable number tandem repeat (VNTR), a SINE-R domain and a poly A-tail. SVA elements are flanked by target site duplications (TSDs). (B) Schematic modified from UCSC genome browser hg38 of the MAPT locus on chromosome 17. This locus contains multiple genes and four SVAs including the SVA_67 RIP (red bar). Six genes (MAPT, KANSL1, CRHR1, LRRC37A, PLEKHM1 and ARL17A) were selected for analysis. SVA_67 (chr17:46,237,519–46,238,226) is anti-sense with respect to the orientation (defined as their 5′ TSS) of the LRRC37A, CRHR1 and MAPT gene, and shows a sense orientation relative to the KANSL1, ARL17A and PLEKHM1 gene. (C) ENCODE data from UCSC showing the levels of enrichment of histone marks in proximity of SVA_67. Signals for H3K27Ac (marker of active regulatory domains associated with active enhancer elements), H3K4Me1 (marker of regulatory domains associated with enhancers) and H3K4Me3 (marker of a regulatory domains associated with promoters) are indicated. The region has been overlaid with a conservation track of several primates and rodents which shows that SVA_67 is human specific.

To date, there are at least 13 disease-causing SVA insertions (Hancks and Kazazian, 2016; Bychkov et al., 2021) including the insertion causing X-linked dystonia parkinsonism (XDP), where an SVA-F element was found in intron 32 of the TATA-box binding protein associated factor 1 (TAF1) gene (Makino et al., 2007; Aneichyk et al., 2018; Delvallée et al., 2021; Yamamoto et al., 2021). Interestingly, this SVA insertion was not only found to be associated with reduced expression of TAF1, alternative splicing and intron retention, but also the length of its CT hexamer repeat inversely correlated with age of onset of the disease (Bragg et al., 2017). Furthermore, polymorphic SVA insertions have been shown to regulate gene expression or isoform expression via intron retention in a population specific manner (Makino et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2017). This highlights their ability to have an impact at many levels on genetic processing and contribute to phenotypic differences within a variety of diseases including neurodegenerative disorders such as PD or ALS. We recently characterised SVA RIPs utilising whole genome sequencing, transcriptomic and clinical data in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) cohort, which was designed to help understand PD aetiology, identify progression markers, and enhance development of novel therapeutics (Initiative, 2011; Pfaff et al., 2021). Eighty-one reference genome SVAs polymorphic for their presence/absence were identified, seven of which were linked with PD progression and with differential gene expression using whole blood RNA sequencing data (Pfaff et al., 2021). One of these RIPs, SVA_67, is located 12 kb upstream of the KAT8 regulatory NSL complex subunit 1 (KANSL1) gene which is part of the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) locus (Figure 1B). The structurally complex MAPT locus contains a 900-kb inversion and is characterised by two predominant haplotypes (H1 and H2) and the presence of SVA_67 is part of H1 (direct inversion) while H2 (inverted) is specified by its absence (Zody et al., 2008; Wider et al., 2010). This locus contains several genes including MAPT in which mutations can cause, or polymorphisms are correlated with the neurodegenerative diseases frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with parkinsonism and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) (Im et al., 2015; Strang et al., 2019). In relation to ALS, it has been shown that 12.5% of patients with behavioural-variant FTD develop ALS, and mild features of motor neuron involvement have been reported in about 40% of patients with FTD (Bang et al., 2015; van Es et al., 2017).

SVAs have the potential to exert regulatory influences on genes distant from the closest gene to which they are found. As non-coding RIPs may lead to interpersonal differences in expression patterns, we aimed to extend our previous findings (Pfaff et al., 2021) by analysing the association of the SVA_67 RIP with isoform expression of six genes located in the block at the MAPT locus including MAPT, KANSL1, corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRHR1), leucine rich repeat containing 37A (LRRC37A), pleckstrin homology and RUN domain containing M1 (PLEKHM1) and ADP ribosylation factor like GTPase 17A (ARL17A). Using the datasets from both the PPMI and New York Genome Center Consortium Target ALS (henceforth NYGC ALS) cohort, we could show that the SVA_67 genotype was significantly associated with differential isoform expression of all genes of interest in the MAPT locus. Our data only addressed the ability of the SVA to alter isoform expression and current data does not give us sufficient power to address isoform expression in disease progression. These approaches could nevertheless lead to a more precise understanding of transposable elements as contributors to a variety of neurodegenerative diseases.

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatic Analysis of the MAPT Locus

The MAPT locus was examined using the UCSC Genome Browser hg381, which contains a set of tools allowing the visualisation of a defined genomic region. The ‘‘Repeat Masker’’ tool2 was used to screen and identify low complexity DNA sequences and interspersed repeats, including retrotransposons and tandem repeat DNA within the reference genome. This method, where “Repeat Masker” annotations were overlaid with conservation data, specifically the “vertebrate multiz alignment” and conservation of 100 vertebrate species from “Phylogenetic Analysis with Space/Time” models (PHAST program) (Hubisz et al., 2011), allowed us to determine if the SVA of interest (SVA_67) was human specific or present in other primates. To analyse the potential of this non-coding region to have regulatory function, the genomic region of SVA_67 was overlaid with data from “The Encyclopaedia of DNA Elements” (ENCODE) (Consortium, 2012). Signals for H3K4Me1, H3K4Me3 and H3K27Ac histone marks, which are found near regulatory regions, promoters, and active regulatory elements, respectively, were analysed.

Genotyping of SVA_67 in Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative and NYGC Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Cohort and Analysis of Differential Isoform Expression

In this study, we utilised data from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) and New York Genome Center Consortium Target ALS (NYGC ALS) cohort. The structural variant caller Delly23 (Rausch et al., 2012), with default settings, was used to genotype SVA_67 in individuals of the PPMI and the NYGC ALS cohorts (Pfaff et al., 2021). The PPMI is a longitudinal study and SVA_67 was genotyped in 608 individuals, including 179 healthy controls, 371 PD and 58 SWEDD (scans without evidence of dopaminergic deficit) subjects (Marek et al., 2018). For the NYGC cohort, the SVA_67 genotype was available for 197 subjects, including 142 ALS, 29 ALS + other neurological disorders (OND), 4 OND, 21 healthy controls and 1 other motor neuron disease (spinal bulbar muscular atrophy). OND diagnosis can include the following diseases: dementia with lewy bodies, peripheral neuropathy, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple system atrophy, frontotemporal dementia, argyrophilic grain disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, acute meningitis, cerebrovascular disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and Parkinson’s disease. RNA-seq data from different tissues of these subjects from the NYGC ALS cohort were available. The majority represented tissues from the central nervous system (CNS), which were complemented by choroid and liver tissues. Taken together, RNA-seq data from the following tissues (total 1,004) were included: cerebellum (163), 141 frontal cortex (141), medial motor cortex (120), lateral motor cortex (119), unspecified motor cortex (10), occipital cortex (75), temporal cortex (5), sensory cortex (2), lumbar spinal cord (114), cervical spinal cord (132), thoracic spinal cord (72), choroid (32) and liver (19).

In order to evaluate the effect of SVA RIP genotypes on the expression profile, differential isoform expression analysis based on the PPMI whole blood RNA-seq data and NYGC ALS RNA-seq data was performed on all subjects. In this analysis, all subjects (cases and controls) were combined. Isoform quantification of RNA-seq data was performed by using the Salmon tool4. Salmon-generated quant files were imported into R using tximport function from the tximport package (Soneson et al., 2015) of R. Counts were extracted with the DESeqDataSetFromTximport function and raw counts were normalised using the median-of-ratios method, implemented in the DESeq2 package (Love et al., 2014). The DESeq2 package in R was also used to detect statistically significant differences in the isoform expression profiles between the different genotypes of SVA_67. The association of three different genotypes (AA, PA, PP) based on the presence (P) or absence (A) of SVA_67 was analysed. The ggplot2 package (Wickham and Sievert, 2016) in R containing the geom_boxplot function was used to visualise the data specifying the stat_summary function to mean. Six genes (MAPT, KANSL1, PLEKHM1, CRHR1, LRCC37A, and ARL17A) centred around this RIP at the MAPT locus were selected for analysis. The unpaired Wilcoxon test was used to compare two independent groups of samples and to demonstrate statistical significance.

Results

Bioinformatic Analysis of the MAPT Locus

The MAPT locus on chromosome 17q21.31 was analysed using UCSC genome browser, specifically evaluating SVAs, ENCODE data and evolutionary DNA conservation over this region (Figure 1). Using the “Repeat Masker” data track for analysis, four SVA retrotransposons were identified, including two SVA-C elements as well as one element of the classes D and F (Figure 1B). UCSC genome browser additionally indicated three potential SVA-A elements which were present in genome version GRCh38/hg38 but were not identified in the previous version GRCh37/hg19. Upon inspection of the primary sequence of these elements we excluded these elements with a length of 58, 127 and 128 bp, respectively, because their sequences did not align with characteristic structures (e.g., CT element, VNTR or 3′ poly A) of SVA elements. These sequences align with sequences of Alu elements and were therefore incorrectly annotated as SVA elements. We previously identified the SVA-F element, termed SVA_67, as a RIP showing that it transposed relatively recently in evolutionarily age. SVA_67 (hg38, chr17:46,237,519–46,238,226), located 12 kb upstream of the KANSL1 gene, represented a truncated element with a length of 707 bp. This element was anti-sense with respect to the orientation of the genes [defined by their 5′ transcriptional start sites (TSS)] LRRC37A, CRHR1 and MAPT, and showed a sense orientation relative to KANSL1, ARL17A and PLEKHM1 (Figures 1B,C). These six genes were selected for isoform expression analyses. The distances between SVA_67 and the TSS of analysed gene isoforms (Table 1) ranged from approximately 12–800,000 kb and are summarised in Table 1. Using the “vertebrate multiz alignment” and conservation track of 100 vertebrate species, this analysis showed that this genomic region was not conserved in chimps, gorillas, gibbons, rhesus macaques, rats, and mice, indicating that SVA_67 was human specific (Figure 1C). We overlaid the genomic region of SVA_67 with data from ENCODE to analyse if this SVA was associated with signals for H3K4Me1 (marker of regulatory domains associated with enhancers), H3K4Me3 (marker of regulatory domains associated with promoters) and H3K27Ac (marker of active regulatory domains associated with active enhancer elements) marks (Figure 1C). No major histone marks associated with active chromatin were observed in proximity to SVA_67, although this may not be surprising as SVAs are not well captured and aligned to specific genomic locations utilising short read DNA sequence due to the repetitive nature and primary sequence homology of the SVA retrotransposons.

TABLE 1.

Analysed gene isoforms in this study and their specifics.

| Name | Transcript ID | bp | Protein | Biotype | Location on chromosome 17 | Distance SVA_67 to TSS (bp) |

| MAPT-201 | ENST00000262410 | 6,815 | 833aa | PC | 45,894,554–46,028,334 | 342,965 |

| MAPT-202 | ENST00000334239 | 1,107 | 352aa | PC | 45,894,668–46,024,183 | 342,851 |

| MAPT-203 | ENST00000344290 | 2,609 | 736aa | PC | 45,894,560–46,024,425 | 342,959 |

| MAPT-204 | ENST00000351559 | 5,639 | 441aa | PC | 45,894,554–46,028,334 | 342,965 |

| MAPT-205 | ENST00000415613 | 2,331 | 776aa | PC | 45,962,338–46,024,171 | 275,181 |

| MAPT-206 | ENST00000420682 | 1,239 | 412aa | PC | 45,962,338–46,024,171 | 275,181 |

| MAPT-207 | ENST00000431008 | 1,233 | 410aa | PC | 45,962,338–46,024,171 | 275,181 |

| MAPT-208 | ENST00000446361 | 5,345 | 383aa | PC | 45,894,674–46,028,334 | 342,845 |

| MAPT-209 | ENST00000535772 | 1,353 | 381aa | PC | 45,894,551–46,024,225 | 342,968 |

| MAPT-210 | ENST00000570299 | 889 | - | PT | 45,894,576–46,018,730 | 342,943 |

| MAPT-211 | ENST00000571311 | 544 | 59aa | NMD | 45,894,566–45,978,425 | 342,953 |

| MAPT-212 | ENST00000571987 | 2,277 | 758aa | PC | 45,962,338–46,024,171 | 275,181 |

| MAPT-213 | ENST00000572440 | 5,015 | - | RI | 45,975,492–45,980,506 | 262,027 |

| MAPT-215 | ENST00000576518 | 6,778 | - | RI | 45,972,783–46,024,431 | 264,736 |

| MAPT-217 | ENST00000680542 | 2,988 | 412aa | PC | 45,894,663–46,025,873 | 342,856 |

| MAPT-218 | ENST00000680674 | 1,936 | 424aa | PC | 45,894,527–46,024,655 | 342,992 |

| KANSL1-201 | ENST00000262419 | 5,309 | 1105aa | PC | 46,029,956–46,192,800 | 44,719 |

| KANSL1-202 | ENST00000432791 | 5,574 | 1105aa | PC | 46,029,916–46,193,429 | 44,090 |

| KANSL1-203 | ENST00000571698 | 2,276 | 678aa | PC | 46,039,870–46,193,901 | 43,618 |

| KANSL1-204 | ENST00000572218 | 9,095 | - | RI | 46,029,916–46,046,121 | 191,398 |

| KANSL1-205 | ENST00000572904 | 4,973 | 1105aa | PC | 46,029,916–46,223,676 | 13,843 |

| KANSL1-206 | ENST00000573286 | 5,437 | - | RI | 46,037,325–46,043,101 | 194,418 |

| KANSL1-207 | ENST00000573682 | 358 | - | RI | 46,032,165–46,033,512 | 204,007 |

| KANSL1-208 | ENST00000574590 | 5,147 | 1104aa | PC | 46,029,916–46,225,389 | 12,130 |

| KANSL1-209 | ENST00000574655 | 1,681 | - | PT | 46,152,904–46,225,371 | 12,148 |

| KANSL1-210 | ENST00000574963 | 1,493 | - | RI | 46,031,074–46,032,566 | 204,953 |

| KANSL1-211 | ENST00000575318 | 4,935 | 1041aa | PC | 46,029,917–46,225,367 | 12,152 |

| KANSL1-212 | ENST00000576137 | 815 | - | RI | 46,033,099–46,039,075 | 198,444 |

| KANSL1-213 | ENST00000576248 | 452 | - | PT | 46,119,967–46,171,223 | 66,296 |

| KANSL1-214 | ENST00000576739 | 592 | 9aa | PC | 46,172,117–46,224,902 | 12,617 |

| KANSL1-215 | ENST00000576870 | 2,848 | - | RI | 46,029,918–46,040,065 | 197,454 |

| KANSL1-216 | ENST00000577114 | 629 | - | PT | 46,050,650–46,121,338 | 116,181 |

| KANSL1-217 | ENST00000638269 | 3,365 | - | RI | 46,092,870–46,225,361 | 12,158 |

| KANSL1-218 | ENST00000638275 | 5,352 | 1041aa | PC | 46,029,917–46,193,400 | 44,119 |

| KANSL1-220 | ENST00000638551 | 899 | - | PT | 46,032,186–46,035,160 | 202,359 |

| KANSL1-221 | ENST00000638902 | 1,971 | - | RI | 46,170,277–46,223,685 | 13,834 |

| KANSL1-222 | ENST00000639099 | 1,724 | - | PT | 46,152,904–46,225,367 | 12,152 |

| KANSL1-223 | ENST00000639150 | 1,815 | 523aa | PC | 46,033,080–46,224,693 | 12,826 |

| KANSL1-224 | ENST00000639279 | 387 | - | PT | 46,088,428–46,094,641 | 142,878 |

| KANSL1-225 | ENST00000639356 | 1,717 | - | PT | 46,148,125–46,225,367 | 12,152 |

| KANSL1-226 | ENST00000639375 | 3,392 | - | RI | 46,049,399–46,225,355 | 12,164 |

| KANSL1-228 | ENST00000639520 | 2,655 | - | PT | 46,221,186–46,225,376 | 12,143 |

| KANSL1-229 | ENST00000639531 | 2,731 | 897aa | PC | 46,032,257–46,172,183 | 65,336 |

| KANSL1-231 | ENST00000639853 | 1,425 | 475aa | PC | 46,038,636–46,171,416 | 66,103 |

| KANSL1-233 | ENST00000640519 | 1,970 | - | PT | 46,033,045–46,035,924 | 201,595 |

| KANSL1-236 | ENST00000648792 | 4,933 | 1061aa | PC | 46,029,985–46,225,373 | 12,146 |

| PLEKHM1-201 | ENST00000430334 | 5,240 | 1056aa | PC | 45,435,900–45,490,721 | 746,798 |

| PLEKHM1-202 | ENST00000446609 | 2,825 | 63aa | NMD | 45,440,163–45,487,858 | 749,661 |

| PLEKHM1-203 | ENST00000579131 | 499 | - | PT | 45,437,916–45,441,059 | 796,460 |

| PLEKHM1-204 | ENST00000579197 | 4,995 | 63aa | NMD | 45,435,904–45,490,728 | 746,791 |

| PLEKHM1-205 | ENST00000580205 | 2,385 | - | PT | 45,452,938–45,460,432 | 777,087 |

| PLEKHM1-206 | ENST00000580404 | 2,628 | - | PT | 45,435,903–45,446,273 | 791,246 |

| PLEKHM1-207 | ENST00000581448 | 3,292 | 335aa | NMD | 45,437,471–45,490,729 | 746,790 |

| PLEKHM1-208 | ENST00000581932 | 1,163 | - | RI | 45,477,074–45,482,525 | 754,994 |

| PLEKHM1-209 | ENST00000582035 | 1,834 | - | RI | 45,452,938–45,454,771 | 782,748 |

| PLEKHM1-211 | ENST00000583150 | 479 | - | PT | 45,439,615–45,448,112 | 789,407 |

| PLEKHM1-212 | ENST00000584420 | 603 | 140aa | PC | 45,475,211–45,490,738 | 746,781 |

| PLEKHM1-213 | ENST00000585506 | 332 | - | RI | 45,439,514–45,440,373 | 797,146 |

| PLEKHM1-214 | ENST00000586084 | 553 | 99aa | NMD | 45,475,696–45,490,741 | 746,778 |

| PLEKHM1-215 | ENST00000586562 | 550 | - | PT | 45,475,597–45,490,749 | 746,770 |

| PLEKHM1-216 | ENST00000589780 | 587 | 152aa | PC | 45,475,366–45,490,741 | 746,778 |

| PLEKHM1-217 | ENST00000590991 | 327 | 45aa | NMD | 45,439,546–45,445,507 | 792,012 |

| PLEKHM1-218 | ENST00000591580 | 650 | 113aa | PC | 45,437,549–45,445,533 | 791,986 |

| CRHR1-201 | ENST00000293493 | 2,621 | 430aa | PC | 45,784,280–45,835,827 | 453,239 |

| CRHR1-202 | ENST00000314537 | 2,537 | 415aa | PC | 45,784,320–45,835,828 | 453,199 |

| CRHR1-203 | ENST00000339069 | 2,490 | 314aa | PC | 45,784,280–45,835,827 | 453,239 |

| CRHR1-204 | ENST00000347197 | 2,462 | 145aa | NMD | 45,784,307–45,835,825 | 453,212 |

| CRHR1-205 | ENST00000352855 | 1,146 | 375aa | PC | 45,784,527–45,834,764 | 452,992 |

| CRHR1-206 | ENST00000398285 | 2,399 | 444aa | PC | 45,784,545–45,835,828 | 452,974 |

| CRHR1-207 | ENST00000535778 | 1,272 | 52aa | NMD | 45,833,138–45,835,644 | 404,381 |

| CRHR1-208 | ENST00000577353 | 1,206 | 401aa | PC | 45,784,545–45,834,764 | 452,974 |

| CRHR1-209 | ENST00000580876 | 223 | 75aa | PC | 45,833,138–45,834,645 | 404,381 |

| CRHR1-210 | ENST00000580955 | 479 | 93aa | NMD | 45,807,074–45,830,125 | 430,445 |

| CRHR1-211 | ENST00000581479 | 606 | - | RI | 45,830,400–45,833,202 | 407,119 |

| CRHR1-212 | ENST00000582766 | 828 | - | RI | 45,784,569–45,830,940 | 452,950 |

| CRHR1-213 | ENST00000583888 | 777 | 152aa | NMD | 45,816,558–45,834,841 | 420,961 |

| CRHR1-214 | ENST00000619154 | 2,370 | 154aa | PC | 45,784,280–45,835,827 | 453,239 |

| ARL17A-202 | ENST00000336125 | 5,242 | 177aa | PC | 46,552,756–46,579,691 | 341,465 |

| ARL17A-203 | ENST00000445552 | 798 | 125aa | PC | 46,516,702–46,579,670 | 342,151 |

| ARL17A-206 | ENST00000622488 | 524 | 88aa | PC | 46,528,685–46,579,673 | 342,154 |

| LRRC37A-201 | ENST00000320254 | 5,177 | 1700aa | PC | 46,295,131–46,337,794 | 56,905 |

| LRRC37A-202 | ENST00000393465 | 4,997 | 1635aa | PC | 46,295,099–46,337,777 | 57,580 |

| LRRC37A-203 | ENST00000496930 | 3,860 | 738aa | PC | 46,292,733–46,337,792 | 55,214 |

PC, protein coding; PT, processed transcript; NMD, non-sense mediated decay; RI, retained intron; TSS, transcriptional start site.

Genotype of SVA_67 Is Significantly Associated With Differential Isoform Expression of Several Genes in the MAPT Locus

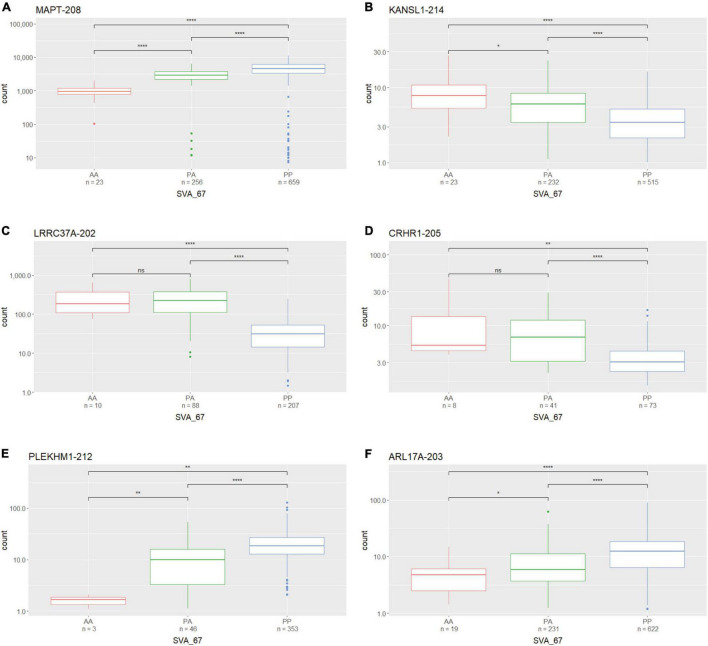

We assessed whether the SVA_67 genotype correlated with isoform expression of six genes (MAPT, KANSL1, PLEKHM1, CRHR1, LRCC37A, ARL17A) centred around this RIP at the MAPT locus (Figure 1B). Transcriptomic data of the PPMI and NYGC ALS cohort was utilised to determine if the SVA RIP had an influence on isoform expression. The association of three different genotypes (AA, PA, PP) based on the presence (P) or absence (A) of SVA_67 was analysed. Initial analysis of one isoform of each gene of interest using the NYGC ALS cohort demonstrated that SVA_67 allele dosage is significantly associated with differential expression of the specific isoforms MAPT-208, KANSL1-214, LRRC37A-202, CRHR1-205, PLEKHM1-212 and ARL17A-203 (Figure 2). Three of these isoforms (MAPT-208, PLEKHM1-212 and ARL17A-203) had significantly increased expression with PP genotype compared to both PA and AA genotype (Figures 2A,E,F). This was in contrast with the levels of expression of the isoforms KANSL1-214, LRRC37A-202 and CRHR1-205 where the opposite pattern was observed (Figures 2B–D). When extending the analysis for all detectable isoforms of the genes of interest using the NYGC ALS cohort, 14/16 MAPT, 3/3 LRRC37A, 3/3 ARL17A, 7/12 CRHR1, 12/17 PLEKHM1 and 23/28 KANSL1 isoforms were significantly associated with at least one SVA_67 genotype (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 1, 3–5, 7, 9). When utilising the PPMI cohort, 2/4 MAPT, 3/3 LRRC37A, 2/2 ARL17A, 5/6 CRHR1, 7/9 PLEKHM1 and 7/7 KANSL1 isoforms were significantly associated with at least one SVA_67 genotype (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 2–4, 6, 8, 10). More isoforms of these genes were detected in the NYGC ALS RNAseq than blood derived from the PPMI cohort. The majority of the corresponding RNAseq data derived from tissues of the CNS (brain and spinal cord) with just a small portion from choroid and liver. Further characterisation and validation will be required to address the significance of that data; however, it could be as simple as the heterogeneity of the CNS compared to blood. Analysed isoforms of each gene and additional information including isoform ID and biotype are summarised in Table 1.

FIGURE 2.

The expression of several gene isoforms at the MAPT locus is associated with SVA_67 genotype. Association of SVA_67 genotype with expression of isoform MAPT-208 (A), KANSL1-214 (B), LRRC37A-202 (C), CRHR1-205 (D), PLEKHM1-212 (E) and ARL17A-203 (F) was analysed by the presence or absence of the SVA RIP (AA, PA, PP) using the NYGC ALS cohort. Wilcoxon test was applied to demonstrate statistical significance indicated as asterisks. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, ns > 0.05.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the effect of SVA_67 allele dosage on isoform expression of genes in the MAPT locus.

| Gene | Analysed isoforms | Significant association of SVA_67 allele dosage on isoform expression |

||

| NYGC ALS cohort | PPMI cohort | Tissue specific influence on ≥ 1 isoform? | ||

| ARL17A | 3 | 3/3 | 2/2 | Yes |

| CRHR1 | 14 | 7/12 | 5/6 | Yes |

| KANSL1 | 30 | 23/28 | 7/7 | Yes |

| LRRC37A | 3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | Yes |

| MAPT | 16 | 14/16 | 2/4 | No |

| PLEKHM1 | 17 | 12/17 | 7/9 | Yes |

Presence of SVA_67 Correlates With Gene Expression in an Isoform-Specific Manner

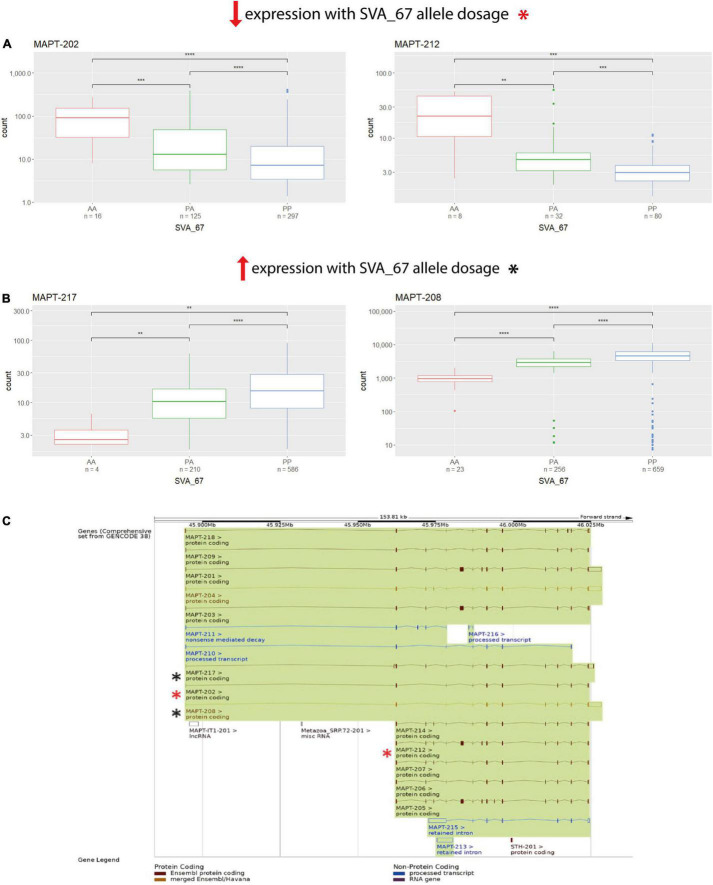

We next assessed if SVA_67 had the same observed influence on each isoform of a gene regarding positive or negative impact on expression. A major consideration when analysing this data was that the expression could be from different cell types in the brain and therefore such positive or negative findings could be generated by two different cell populations. Nevertheless, utilising the NYGC ALS cohort, there was at least one isoform of each analysed gene present that demonstrated higher and lower expression, respectively, in individuals with PP genotypes compared to both PA and AA genotypes. For example, when addressing MAPT, the isoforms MAPT-202 and MAPT-212 showed significantly reduced expression with PP genotype compared to both PA and AA (Figure 3A), while two other isoforms of this same gene (MAPT-208 and MAPT-217) showed the opposite effect (Figure 3B). All four displayed isoforms represented protein coding isoforms encoding distinct proteins with different lengths and there was no association with a specific TSS although several are defined for the gene (Figure 3C and Table 1). This isoform-specific effect of SVA_67 on expression was also visible when using the PPMI cohort, where subjects with PP genotypes showed significantly increased and reduced, respectively, expression of a specific isoform compared to AA, PA or both PA and AA genotypes. For example, KANSL1 isoforms KANSL1-201 and KANSL1-211 showed significantly increased expression with PP genotype compared to both PA and AA, while isoforms KANSL1-209 and KANSL1-214 were associated with reduced expression when the subjects had both alleles of SVA_67 present (Supplementary Figure 10). No statistical significance regarding positive and negative effect was obtained for MAPT isoforms in the PPMI cohort. Here, subjects with PP genotype correlated significantly with increased expression of isoform MAPT-208 (PP vs PA and AA) and MAPT-215 (PP vs AA) (Supplementary Figure 2). The association of SVA_67 genotype did not reach statistical significance for the isoform MAPT-211, however, a trend was visible which indicated a reduced expression with PP and PA genotypes compared to subjects having no allele of SVA_67 present.

FIGURE 3.

SVA_67 influences expression in an isoform-specific manner. Using the NYGC ALS cohort, isoforms MAPT-202 and MAPT-212 show significantly reduced expression with PP genotype (A), while the opposite effect is observed for isoforms MAPT-217 and MAPT-208 (B). Wilcoxon test was applied to demonstrate statistical significance indicated as asterisks. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, ns > 0.05. (C) Overview of the MAPT gene and all its isoforms as shown on Ensembl. Boxes represent exons, connecting lines introns. Filled boxes show coding sequence, and empty boxes UTRs (untranslated regions). Analysed isoforms of interest in panels (A,B) are highlighted as asterisks (red/black).

A Tissue Specific Influence of SVA_67 Allele Dosage on Isoform Expression

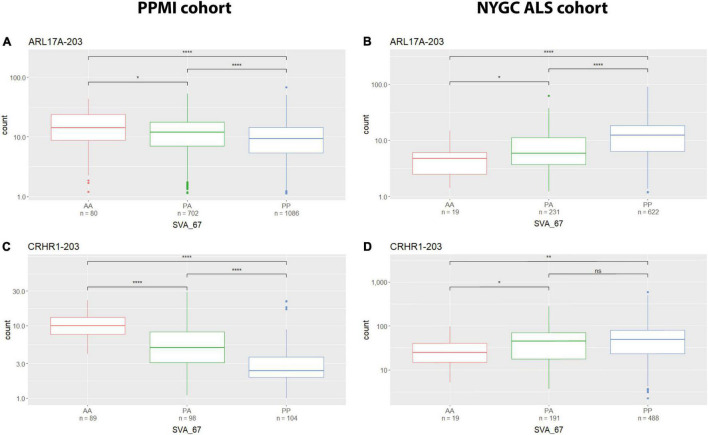

We analysed the effect of SVA_67 on specific isoforms in different tissues by comparing the influence of this SVA RIP in two different datasets (PPMI and NYGC ALS cohort). The six isoforms LRRC37A-201, ARL17A-203, CRHR1-203, PLEKHM1-202, KANSL1-208 and KANSL1-209 were differentially influenced by SVA_67 allele dosage demonstrating opposing effects on expression when comparing both datasets (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 3, 7–10). Using the PPMI cohort, isoform PLEKHM1-202 showed significantly increased expression with PP genotype compared to both PA and AA genotype, while the opposite effect is visible when utilising the NYGC ALS cohort. We do not believe this is disease specific as we have both cases and controls in our datasets to give us power to address transcriptional changes, however, isoform association with disease can be considered in the future as the number of cases and controls increases in such data sets. A tissue-specific effect was also detectable for the two KANSL1 isoforms KANSL1-208 and KANSL1-209. When using the PPMI dataset for analysis, both isoforms were associated with reduced expression when having two alleles of SVA_67 present, while the same genotype led to a decreased expression when using the NYGC ALS cohort for analysis. Regarding LRRC37A-201, this isoform showed an increased expression with one copy of SVA_67 present compared to AA in the PPMI cohort. Again, the opposite effect was visible when utilising the NYGC ALS dataset. ARL17A-203 and CRHR1-203 isoforms showed a significantly reduced expression with PP genotype compared to both PA and AA genotype (PPMI dataset) (Figures 4A,C), while the opposite effect was visible when utilising the NYGC ALS cohort (Figures 4B,D).

FIGURE 4.

Tissue specific influence of SVA_67 genotype. Using the PPMI cohort, isoforms ARL17A-203 (A) and CRHR1-203 (C) show significantly reduced expression with PP genotype, while the opposite effect is observed when using the NYGC ALS cohort (B,D). Wilcoxon test was applied to demonstrate statistical significance indicated as asterisks. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, ns > 0.05.

Discussion

In this study we analysed the impact of SVA_67 allele dosage on isoform expression of six genes (MAPT, KANSL1, CRHR1, PLEKHM1, ARL17A and LRRC37A) at the MAPT locus (Figure 1) in order to gain insight into the role of SVAs to modify the transcriptome. Using two different datasets (PPMI and NYGC ALS cohort) for analysis, we could demonstrate that SVA_67 was significantly associated with 1) changes in expression of multiple genes at this locus and 2) both differential isoform and tissue specific expression of these genes (Figures 2–4 and Table 2). The data is consistent with SVAs having functional consequences for gene expression over long distances directly by activator or repressor mechanisms or their ability to modulate genome structure by looping mechanisms affecting 3D structures in such as transcriptional hubs (Ferrari et al., 2021).

SVAs have previously been demonstrated to be involved in genetic instability and disease progression via genome regulation mechanisms (Hancks and Kazazian, 2010, 2016; Ayarpadikannan and Kim, 2014). It has been demonstrated that SVAs can modulate gene expression profiles by various mechanisms, for instance, by transcription factor binding, altering patterns of methylation and interaction with distant promoters through 3D chromatin structure by recruiting CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), a master regulator of 3D chromatin structure (Hancks et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2019). Indeed, TEs have shown to have multiple binding sites for CTCF which has a well-established role in chromatin looping and topologically associated domain (TAD) formation (Bourque et al., 2008; Schwalie et al., 2013; Kentepozidou et al., 2020; Pugacheva et al., 2020). This could be one model to allow SVA_67 to act at many genes to enhance or reduce gene isoform expression or alter chromatin structure via looping. This is consistent with the obtained results showing that SVA_67 was capable of affecting isoform expression at both the most proximal (e.g., KANSL1) and most distant (e.g., PLEKHM1) TSS relative to its location at the MAPT locus (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figures 7–10).

We have previously characterised the function of SVAs to modulate gene expression profiles by in vitro and in vivo models including an SVA upstream of the FUS RNA binding protein (FUS) gene in which genetic mutations have been linked to many diseases including ALS (Savage et al., 2014) and an SVA upstream of the Parkinsonism associated deglycase DJ-1 gene, also termed PARK7, a gene associated with PD (Savage et al., 2013). These demonstrated the action of SVAs to have classical regulatory domains when analysed in reporter gene constructs and indeed that the SVAs were a composite regulatory domain containing multiple functional domains. In our recent study, we could identify 81 reference SVAs polymorphic for their presence/absence, seven of which, including SVA_67, were associated with the progression of PD using the PPMI cohort (Pfaff et al., 2021). We have extended that previous work by addressing differential gene expression on an isoform-based level using the same cohort. We observed that SVA_67 had an isoform-specific correlation with gene expression showing potentially the capacity of SVA_67 to differentially modulate the transcriptome (Figure 3). Although we do not wish to draw conclusions regarding specific expression and disease progression, we do want to highlight the plethora of transcriptomic changes associated with one SVA insertion. We are not able to demonstrate that causation of differential gene expression is directed by the SVA which would await functional validation by such as CRISPR. No study to date has shown this regulatory influence of an SVA on an isoform-specific level, although intron retention has been proposed for the action of an SVA within an intron of the TAF1 gene (Makino et al., 2007). However, intron retention is not operating at the MAPT locus as the SVA is intergenic in nature (Figure 1). To date, studies have focused predominantly on differential gene expression analyses, however, these approaches are limited as they do not account for isoform diversity (Makino et al., 2007; Hancks and Kazazian, 2010; Gianfrancesco et al., 2017; Hall et al., 2020). Many of the genes at this locus have been associated with CNS functional parameters (Caillet-Boudin et al., 2015; McEwan et al., 2015; Moreno-Igoa et al., 2015; de la Tremblaye et al., 2017) and encode more than one isoform which are generated, for instance, through mechanisms such as alternative splicing or alternative usage of transcription start sites (Elkon et al., 2013). It is important to differentiate between isoforms, as some of these can represent protein-coding isoforms with different functions and/or subcellular localisations, while others do not lead to a protein product (Table 1). Dick et al. (2020) have reported the first genome-wide study of differential transcript usage (DTU), the measure of the relative contribution of one isoform to overall gene expression, in PD. The authors demonstrated that PD subjects showed a decrease in the relative usage of a thioesterase superfamily member 5 (THEM5) transcript (involved in mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism), while the concomitant increase of a shorter isoform, which more likely localises to the extracellular space than to the mitochondria, may therefore not recapitulate the function of the full-length protein (Zhuravleva et al., 2012; Dick et al., 2020). Indeed, these observed changes in the relative expression of specific gene isoforms may affect the ratio of the resulting protein isoforms, which in turn could affect cellular signalling pathway or metabolism through variation of, for instance, function and subcellular localisation (Dick et al., 2020). In our study SVA_67 allele dosage was significantly associated, for instance, with PLEKHM1 isoform expression (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figures 7, 8). McEwan et al. (2015) demonstrated in their study that PLEKHM1 regulates clearance of protein aggregates in an autophagy- and LC3-interacting region-dependent manner. Mutant or misfolded protein accumulation is implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple neurodegenerative diseases, and dysfunction or depletion of PLEKHM1 links this important regulator of protein aggregate removal to an increased risk of PD and ALS. Our data suggest that SVA_67 could influence PLEKHM1 function by modulating isoform expression which could result in a gene specific DTU. This may have an impact on the potential role of PLEKHM1 in maintaining appropriate cellular functions or even cell survival. Future work could address the role of PLEKHM1 and other genes of interest in this study in neurodegenerative diseases by analysing the influence of isoform switches and DTU. More importantly it demonstrates the potential for multigenic regulatory effects of a single variant over a large region of the genome giving greater insight into the complex mechanisms that have to be factored in to understand how a variant is affecting not only genomic regulation but disease progression.

It is known that TE derived sequences can contribute to the regulation of the human genome and that domains with regulatory potential can function in a tissue-specific manner. We previously utilised Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database (Consortium, 2013) to characterise the potential of SVA_67 to act in other tissues using its proxy SNP (rs55653937) (Pfaff et al., 2021). This approach led, based on the findings that the tagging SNP for SVA_67 was identified as eQTL (expression quantitative trait loci) for over 30 genes including the six genes of interest in this study, to the assumption that SVA_67 could also influence gene expression in other tissues in addition to whole blood. We validated that by using transcriptomic data derived from different tissues (NYGC ALS vs PPMI) and demonstrated that SVA_67 correlated with a tissue-specific effect on isoform expression of six genes in the MAPT locus (Figure 4).

Our study presented here demonstrated that SVA insertions have the potential to influence expression of multiple genes over large distances and that regulation can be isoform specific. SVAs could be influencing the disease course of PD and ALS through modulation of isoform expression and usage which ultimately could affect protein levels and biological processes. Therefore, this study highlighted an additional type of variation to be considered at the MAPT locus and an added layer of complexity when analysing the missing heritability of neurodegenerative diseases.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. This data can be found here: Raw data are available from the PPMI (www.ppmi-info.org/data) and the NYGC Target ALS (https://www.targetals.org/research/resources-for-scientists/) website.

Author Contributions

AF, AP, VB, SK, and JQ contributed to study concept, design, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. AF drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) database (www.ppmi-info.org/data). For up-to-date information on the study, visit www.ppmi-info.org. PPMI—a public-private partnership—is funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including Abbvie, Allergan, Amathus therapeutics, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, Biolegend, Briston-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Denali, GE Healthcare, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, janssen neuroscience, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, Meso Scale Discovery, Pfizer, Piramal, Prevail Therapeutics, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Servier, Takeda, Teva, UCB, Verily, and Voyager Therapeutics. We acknowledge the Target ALS Human Postmortem Tissue Core, New York Genome Center for Genomics of Neurodegenerative Disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association and TOW Foundation for RNA-seq data of human ALS patients.

Abbreviations

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ARL17A

ADP ribosylation factor like GTPase 17A

- CRHR1

corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1

- CTCF

CCCTC-binding factor

- DTU

differential transcript usage

- ENCODE

The Encyclopaedia of DNA Elements

- eQTL

expression quantitative trait loci

- FTD

frontotemporal dementia

- FUS

FUS RNA binding protein

- GTEx

Genotype-Tissue Expression

- KANSL1

KAT8 regulatory NSL complex subunit 1

- LRRC37A

leucine rich repeat containing 37A

- MAPT

microtubule-associated protein tau

- NYGC ALS

New York Genome Center Consortium Target ALS

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PLEKHM1

pleckstrin homology and RUN domain containing M1

- PPMI

Parkinson’s Progression Marker Initiative

- PSP

progressive supranuclear palsy

- RIP

retrotransposon insertion polymorphism

- SVA

SINE-VNTR-Alu

- TAD

topologically associated domain

- TAF1

TATA-box binding protein associated factor 1

- TE

transposable element

- THEM5

thioesterase superfamily member 5

- TSS

transcriptional start site

- VNTR

variable number tandem repeat

- XDP

X-linked dystonia parkinsonism.

Footnotes

Funding

AF and JQ are funded by the Andrzej Wlodarski Memorial Research Fund. AF was recipient of Andrzej Wlodarski Memorial Research Ph.D. scholarship. AP and SK are funded by MSWA and Perron Institute for Neurological and Translational Science. VB and JQ are funded by the MNDA (Grant Number: Quinn/Apr15/843-791). This study was funded by the Motor Neurone Disease Association (Grant Number: 41/523). This work was supported by resources provided by the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre with funding from the Australian Government and the Government of Western Australia.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2022.815695/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aneichyk T., Hendriks W. T., Yadav R., Shin D., Gao D., Vaine C. A., et al. (2018). Dissecting the causal mechanism of X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism by integrating genome and transcriptome assembly. Cell 172 897–909.e21. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayarpadikannan S., Kim H. S. (2014). The impact of transposable elements in genome evolution and genetic instability and their implications in various diseases. Genomics Inform. 12 98–104. 10.5808/GI.2014.12.3.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang J., Spina S., Miller B. L. (2015). Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet 386 1672–1682. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00461-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauwendraat C., Nalls M. A., Singleton A. B. (2020). The genetic architecture of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 19 170–178. 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30287-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque G., Burns K. H., Gehring M., Gorbunova V., Seluanov A., Hammell M., et al. (2018). Ten things you should know about transposable elements. Genome Biol. 19:199. 10.1186/s13059-018-1577-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque G., Leong B., Vega V. B., Chen X., Lee Y. L., Srinivasan K. G., et al. (2008). Evolution of the mammalian transcription factor binding repertoire via transposable elements. Genome Res. 18 1752–1762. 10.1101/gr.080663.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg D. C., Mangkalaphiban K., Vaine C. A., Kulkarni N. J., Shin D., Yadav R., et al. (2017). Disease onset in X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism correlates with expansion of a hexameric repeat within an SVA retrotransposon in. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 E11020–E11028. 10.1073/pnas.1712526114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov I., Baydakova G., Filatova A., Migiaev O., Marakhonov A., Pechatnikova N., et al. (2021). Complex transposon insertion as a novel cause of pompe disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:10887. 10.3390/ijms221910887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillet-Boudin M. L., Buée L., Sergeant N., Lefebvre B. (2015). Regulation of human MAPT gene expression. Mol. Neurodegener. 10:28. 10.1186/s13024-015-0025-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium E. P. (2012). An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489 57–74. 10.1038/nature11247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium G. (2013). The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 45 580–585. 10.1038/ng.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Tremblaye P. B., Benoit S. M., Schock S., Plamondon H. (2017). CRHR1 exacerbates the glial inflammatory response and alters BDNF/TrkB/pCREB signaling in a rat model of global cerebral ischemia: implications for neuroprotection and cognitive recovery. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 79(Pt. B), 234–248. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvallée C., Nicaise S., Antin M., Leuvrey A. S., Nourisson E., Leitch C. C., et al. (2021). A BBS1 SVA F retrotransposon insertion is a frequent cause of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Clin. Genet. 99 318–324. 10.1111/cge.13878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick F., Nido G. S., Alves G. W., Tysnes O. B., Nilsen G. H., Dölle C., et al. (2020). Differential transcript usage in the Parkinson’s disease brain. PLoS Genet. 16:e1009182. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbarbary R. A., Lucas B. A., Maquat L. E. (2016). Retrotransposons as regulators of gene expression. Science 351:aac7247. 10.1126/science.aac7247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkon R., Ugalde A. P., Agami R. (2013). Alternative cleavage and polyadenylation: extent, regulation and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14 496–506. 10.1038/nrg3482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamzadeh F. N., Surguchov A. (2018). Parkinson’s disease: biomarkers, treatment, and risk factors. Front. Neurosci. 12:612. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R., Grandi N., Tramontano E., Dieci G. (2021). Retrotransposons as drivers of mammalian brain evolution. Life 11:376. 10.3390/life11050376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianfrancesco O., Bubb V. J., Quinn J. P. (2017). SVA retrotransposons as potential modulators of neuropeptide gene expression. Neuropeptides 64 3–7. 10.1016/j.npep.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianfrancesco O., Geary B., Savage A. L., Billingsley K. J., Bubb V. J., Quinn J. P. (2019). The role of SINE-VNTR-Alu (SVA) retrotransposons in shaping the human genome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:5977. 10.3390/ijms20235977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A., Moore A. K., Hernandez D. G., Billingsley K. J., Bubb V. J., Quinn J. P., et al. (2020). A SINE-VNTR-Alu in the LRIG2 promoter is associated with gene expression at the locus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:8486. 10.3390/ijms21228486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancks D. C., Kazazian H. H. (2010). SVA retrotransposons: evolution and genetic instability. Semin. Cancer Biol. 20 234–245. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancks D. C., Kazazian H. H. (2016). Roles for retrotransposon insertions in human disease. Mob. DNA 7:9. 10.1186/s13100-016-0065-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancks D. C., Goodier J. L., Mandal P. K., Cheung L. E., Kazazian H. H. (2011). Retrotransposition of marked SVA elements by human L1s in cultured cells. Hum Mol Genet 20 3386–3400. 10.1093/hmg/ddr245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubisz M. J., Pollard K. S., Siepel A. (2011). PHAST and RPHAST: phylogenetic analysis with space/time models. Brief Bioinform. 12 41–51. 10.1093/bib/bbq072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im S. Y., Kim Y. E., Kim Y. J. (2015). Genetics of progressive supranuclear palsy. J. Mov. Disord. 8 122–129. 10.14802/jmd.15033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Initiative P. P. M. (2011). The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI). Prog. Neurobiol. 95 629–635. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentepozidou E., Aitken S. J., Feig C., Stefflova K., Ibarra-Soria X., Odom D. T., et al. (2020). Clustered CTCF binding is an evolutionary mechanism to maintain topologically associating domains. Genome Biol. 21:5. 10.1186/s13059-019-1894-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S., Kaji R., Ando S., Tomizawa M., Yasuno K., Goto S., et al. (2007). Reduced neuron-specific expression of the TAF1 gene is associated with X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80 393–406. 10.1086/512129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek K., Chowdhury S., Siderowf A., Lasch S., Coffey C. S., Caspell-Garcia C., et al. (2018). The Parkinson’s progression markers initiative (PPMI) - establishing a PD biomarker cohort. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 5 1460–1477. 10.1002/acn3.644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan D. G., Popovic D., Gubas A., Terawaki S., Suzuki H., Stadel D., et al. (2015). PLEKHM1 regulates autophagosome-lysosome fusion through HOPS complex and LC3/GABARAP proteins. Mol. Cell 57 39–54. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Igoa M., Hernández-Charro B., Bengoa-Alonso A., Pérez-Juana-del-Casal A., Romero-Ibarra C., Nieva-Echebarria B., et al. (2015). KANSL1 gene disruption associated with the full clinical spectrum of 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome. BMC Med. Genet. 16:68. 10.1186/s12881-015-0211-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalls M. A., Blauwendraat C., Vallerga C. L., Heilbron K., Bandres-Ciga S., Chang D., et al. (2019). Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 18 1091–1102. 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30320-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff A. L., Bubb V. J., Quinn J. P., Koks S. (2021). Reference SVA insertion polymorphisms are associated with Parkinson’s Disease progression and differential gene expression. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 7:44. 10.1038/s41531-021-00189-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugacheva E. M., Kubo N., Loukinov D., Tajmul M., Kang S., Kovalchuk A. L., et al. (2020). CTCF mediates chromatin looping via N-terminal domain-dependent cohesin retention. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 2020–2031. 10.1073/pnas.1911708117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch T., Zichner T., Schlattl A., Stütz A. M., Benes V., Korbel J. O. (2012). DELLY: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics 28 i333–i339. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage A. L., Bubb V. J., Breen G., Quinn J. P. (2013). Characterisation of the potential function of SVA retrotransposons to modulate gene expression patterns. BMC Evol. Biol. 13:101. 10.1186/1471-2148-13-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage A. L., Schumann G. G., Breen G., Bubb V. J., Al-Chalabi A., Quinn J. P. (2019). Retrotransposons in the development and progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 90 284–293. 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage A. L., Wilm T. P., Khursheed K., Shatunov A., Morrison K. E., Shaw P. J., et al. (2014). An evaluation of a SVA retrotransposon in the FUS promoter as a transcriptional regulator and its association to ALS. PLoS One 9:e90833. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalie P. C., Ward M. C., Cain C. E., Faure A. J., Gilad Y., Odom D. T., et al. (2013). Co-binding by YY1 identifies the transcriptionally active, highly conserved set of CTCF-bound regions in primate genomes. Genome Biol. 14 R148. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-12-r148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soneson C., Love M. I., Robinson M. D. (2015). Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res 4:1521. 10.12688/f1000research.7563.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang K. H., Golde T. E., Giasson B. I. (2019). MAPT mutations, tauopathy, and mechanisms of neurodegeneration. Lab. Invest. 99 912–928. 10.1038/s41374-019-0197-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. P., Brown R. H., Cleveland D. W. (2016). Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature 539 197–206. 10.1038/nature20413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es M. A., Hardiman O., Chio A., Al-Chalabi A., Pasterkamp R. J., Veldink J. H., et al. (2017). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 390 2084–2098. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31287-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rheenen W., Shatunov A., Dekker A. M., McLaughlin R. L., Diekstra F. P., Pulit S. L., et al. (2016). Genome-wide association analyses identify new risk variants and the genetic architecture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 48 1043–1048. 10.1038/ng.3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasieva O., Cetiner S., Savage A., Schumann G. G., Bubb V. J., Quinn J. P. (2017). Potential impact of primate-specific SVA retrotransposons during the evolution of human cognitive function. Trends Evol. Biol. 6 1–6. 10.4081/eb.2017.6514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. C., Wang W., Zhang L., Wang X. (2019). A tour of 3D genome with a focus on CTCF. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 90 4–11. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Xing J., Grover D., Hedges D. J., Han K., Walker J. A., et al. (2005). SVA elements: a hominid-specific retroposon family. J. Mol. Biol. 354 994–1007. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Rishishwar L., Mariño-Ramírez L., Jordan I. K. (2017). Human population-specific gene expression and transcriptional network modification with polymorphic transposable elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 2318–2328. 10.1093/nar/gkw1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H., Sievert C. (2016). ggplot2 : Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wider C., Vilariño-Güell C., Jasinska-Myga B., Heckman M. G., Soto-Ortolaza A. I., Cobb S. A., et al. (2010). Association of the MAPT locus with Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 17 483–486. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02847.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto G., Miyabe I., Tanaka K., Kakuta M., Watanabe M., Kawakami S., et al. (2021). SVA retrotransposon insertion in exon of MMR genes results in aberrant RNA splicing and causes Lynch syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 29 680–686. 10.1038/s41431-020-00779-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuravleva E., Gut H., Hynx D., Marcellin D., Bleck C. K., Genoud C., et al. (2012). Acyl coenzyme A thioesterase Them5/Acot15 is involved in cardiolipin remodeling and fatty liver development. Mol. Cell Biol. 32 2685–2697. 10.1128/MCB.00312-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zody M. C., Jiang Z., Fung H. C., Antonacci F., Hillier L. W., Cardone M. F., et al. (2008). Evolutionary toggling of the MAPT 17q21.31 inversion region. Nat. Genet. 40 1076–1083. 10.1038/ng.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. This data can be found here: Raw data are available from the PPMI (www.ppmi-info.org/data) and the NYGC Target ALS (https://www.targetals.org/research/resources-for-scientists/) website.