Abstract

The measurement of neutrino mass ordering (MO) is a fundamental element for the understanding of leptonic flavour sector of the Standard Model of Particle Physics. Its determination relies on the precise measurement of and using either neutrino vacuum oscillations, such as the ones studied by medium baseline reactor experiments, or matter effect modified oscillations such as those manifesting in long-baseline neutrino beams (LBB) or atmospheric neutrino experiments. Despite existing MO indication today, a fully resolved MO measurement () is most likely to await for the next generation of neutrino experiments: JUNO, whose stand-alone sensitivity is , or LBB experiments (DUNE and Hyper-Kamiokande). Upcoming atmospheric neutrino experiments are also expected to provide precious information. In this work, we study the possible context for the earliest full MO resolution. A firm resolution is possible even before 2028, exploiting mainly vacuum oscillation, upon the combination of JUNO and the current generation of LBB experiments (NOvA and T2K). This opportunity is possible thanks to a powerful synergy boosting the overall sensitivity where the sub-percent precision of by LBB experiments is found to be the leading order term for the MO earliest discovery. We also found that the comparison between matter and vacuum driven oscillation results enables unique discovery potential for physics beyond the Standard Model.

Subject terms: Experimental particle physics, Phenomenology

Introduction

The discovery of the neutrino () oscillations phenomenon has completed a remarkable scientific endeavor lasting several decades changing forever our understanding of the leptonic sector’s phenomenology of the standard model of elementary particles (SM). The new phenomenon was taken into account by introducing massive neutrinos and consequently neutrino flavour mixing and the possibility of violation of charge conjugation parity symmetry or CP-violation (CPV); e.g., review1.

Neutrino oscillations imply that the neutrino mass eigenstates (, , ) spectrum is non-degenerate, so at least two neutrinos are massive. Each mass eigenstate (; with i = 1, 2, 3) can be regarded as a non-trivial mixture of the known neutrino flavour eigenstates (, , ), linked to the three (e, , ) respective charged leptons. Since no significant experimental evidence beyond three families exists so far, the mixing is characterised by the so called Pontecorvo-Maki-Nakagawa-Sakata (PMNS)2,3 matrix, assumed to be unitary, thus parameterised by three independent mixing angles (, , ) and one CP phase (). The neutrino mass spectra are indirectly known via the two measured mass squared differences, indicated as () and (), respectively, related to the / and / pairs. The neutrino absolute mass is not directly accessible via neutrino oscillations and remains unknown, despite considerable active research4.

As of today, the field is well established both experimentally and phenomenologically. All relevant parameters (, , and , ) are known to the few percent precision. The phase and the sign of , the so-called Mass Ordering (MO), remain unknown despite existing hints (i.e., effects). CPV processes arise if is different from 0 or , i.e., CP-conserving solutions. The measurement of the MO has the peculiarity of having only a binary solution, either normal mass ordering (NMO), in case , or inverted mass ordering (IMO) if . In order words, determining MO implies to know which is the lightest neutrino (or ), respective the case of NMO (IMO). The positive sign of is known from solar neutrino data5–9 combined with KamLAND10, establishing the solar large mixing angle MSW11,12 solution.

Mass ordering knowledge

This publication focuses on the global strategy to achieve the earliest and most robust MO determination scenario. MO has rich implications not only for the terrestrial oscillation experiments, to be discussed in this paper, but also for non-oscillation experiments like search for neutrinoless double beta decay (e.g., review13) or from more broad aspects, from a fundamental theoretical (e.g., review14), an astrophysical (e.g., review15), and cosmological (e.g., review16) points of view. Present knowledge from global data4,17–19 implies a few hints on both MO and , where the latest results were reported at Neutrino 2020 Conference20. According to the latest NuFit5.021 global data analysis, NMO is favoured up to . However, this preference remains fragile, as it will be explained later on.

Experimentally, MO can be addressed via three very different techniques (e.g.,22 for earlier work): (a) medium baseline reactor experiment23 (i.e., JUNO) (b) long-baseline neutrino beams (labeled here LBB) and (c) atmospheric neutrino based experiments. MO determination by LBB and atmospheric neutrinos relies on matter effects11,12 as neutrinos traverse the Earth over long enough baselines. Since Earth is made of matter, and not of anti-matter, the effect of elastic forward scattering for electron anti-neutrinos and neutrinos depends on the sign of . Instead, JUNO24 is currently the only experiment able to resolve MO via dominant vacuum oscillations [JUNO has a minor matter effect impact, mainly on the oscillation while tiny on MO sensitive oscillation25], thus holding a unique insight and capability in the MO world strategy.

The current generation of LBB experiments, here called LBB-II [The first generation LBB-I are here considered to be K2K26, MINOS27 and OPERA28 experiments], are NOvA29 and T2K30. These are to be followed up by the next generation LBB-III with the DUNE31 and the Hyper-Kamiokande (HK)32 experiments, which are expected to start taking data around 2027. In Korea, a possible second HK detector would enhance its MO determination sensitivity33. In this paper we focus mainly on the immediate impact of the LBB-II. Nonetheless, we shall highlight the prospect contributions by LBB-III, due to their leading order implications to the MO resolution. Contrary to those experiments, JUNO relies on high precision reactor neutrino spectral analysis for the extraction of MO sensitivity.

The relevant atmospheric neutrino experiments are Super-Kamiokande34 (SK) and IceCube35 (both running) as well as future specialised facilities such as INO36, ORCA37 and PINGU38. The advantage of atmospheric neutrinos experiments to probe many baselines simultaneously, is partially compensated by the more considerable uncertainties in baseline and energy reconstruction and limited separation. The HK experiment may also offer critical MO insight via atmospheric neutrinos.

Despite their different MO sensitivity potential and time schedules (discussed in the end), it is worth highlighting each technique’s complementarity as a function of the relevant neutrino oscillation unknowns. The MO sensitivity of atmospheric experiments depends heavily on the so called octant ambiguity [This implies the approximate degeneracy of oscillation probabilities for the cases between and ]39, while LBB experiments exhibit a smaller dependence. JUNO is, however, independent, a unique asset. Regarding the unknown , its role in atmospheric and LBB’s inverts, while JUNO remains uniquely independent. This way, the MO sensitivity dependence on is less important for atmospheric neutrinos (i.e. washed out), but LBB-II are to a great extent handicapped by the degenerate phase-space competition to resolve both and MO simultaneously. In brief, the MO sensitivity interval of ORCA/PINGU swings about the 3 to 5, depending on the value of and LBB-II sensitivities are effectively blinded to MO for more than half of the phase-space. However, DUNE has the unique ability to resolve MO, also via matter effects, regardless of . Although not playing an explicit role, the constraint on , from reactor experiments (i.e. Daya Bay40, Double Chooz41 and RENO42), is critical for the MO (and ) quest for JUNO and LBB experiments.

This publication aims to illustrate, and numerically demonstrate, via a simplified estimation, the relevant ingredients to reach a fully resolved (i.e., ) MO measurement strategy relying, whenever possible, only on existing (or imminently so) experiments to yield the fastest timeline [the timelines of experiments are involved, as the construction schedules may delay beyond the scientific teams’ control. Our approach aims to provide minimal timing information to contextualise the experiments, but variations may be expected]. Our approach relies on the latest 3 global data information21, summarised in Table 1, to tune our analysis to the most probable and up to date measurements on , and , using only the LBB inputs, as motivated later. This work updates and expands previous works43–45 basing the calculations on , instead of , as well as including the effects of the uncertainties on the relevant oscillation parameters. In addition, the here presented results are contextualized in the current experimental landscape, in terms of current precision of the oscillation parameters and the present-day performances of current and near future neutrino oscillation experiments, providing an important insight into the prospects for solving the neutrino mass ordering.

Table 1.

In this work, the neutrino oscillation parameters are reduced to the latest values obtained in the NuFit5.021, where , and (last two rows) were obtained by using only LBB experiments by fixing , and to the values shown in this table (second row).

| NuFit5.0 | |||

| Both MO | 0.304 | 0.0224 | |

| LBB | |||

| NMO | 0.565 | ||

| IMO | 0.568 |

We also aim to highlight some important redundancies across experiments that could aid the robustness of the MO resolution and exploit—likely for the first time—the MO measurements for high precision scrutiny of the standard 3 flavour scheme. In this context, MO exploration might open the potential for manifestations of physics beyond the Standard Model (BSM), e.g., see reviews24,46. Our simplified approach is expected to be improvable by more complete developments (i.e. full combination of experiments’ data), once data is available. Such approach, though, is considered beyond our scope as it is unlikely to significantly change our findings and conclusions, given the data precision available today. To better accommodate our approach’s known limitations, we have intentionally performed a conservative rationale. We shall elaborate on these points further during the discussion of the final results.

Mass ordering resolution analysis

Our analysis relies on a simplified combination of experiments able to yield MO sensitivity intrinsically (i.e. standalone) and via inter-experiment synergies, where the gain may be direct or indirect. The indirect gain implies that the sensitivity improvement occurs due to the combination itself; i.e. hence not accessible to neither experiment alone but caused by the complementary nature of the different experiments’ observables. These effects will be carefully studied, including the delicate arising dependencies to ensure accurate prediction are obtained. The existing synergies found embody a framework for powerful sensitivity boosting to yield MO resolution upon combination. To this end, we shall combine the running LBB-II experiments with the shortly forthcoming JUNO. The valuable additional information from atmospheric experiments will be considered qualitatively, for simplicity, only at the end during the discussion of results. Unless otherwise stated explicitly, throughout this work, we shall use only the NuFit5.021 best-fit values summarised in Table 1, to guide our estimations and predictions by today’s data.

Mass ordering resolution power in JUNO

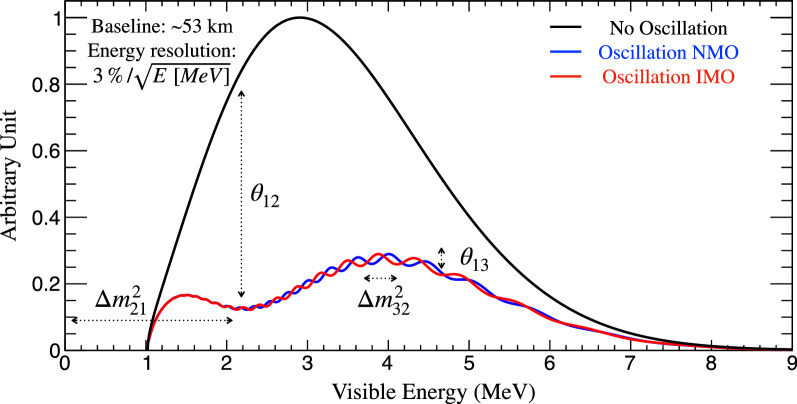

The JUNO experiment24 is one of the most powerful neutrino oscillation high precision machines. The JUNO spectral distortion effects are described in Fig. 1, and its data-taking is expected to start in 202348. The possibility to explore precision neutrino oscillation physics with an intermediate baseline reactor neutrino experiment was first pointed out in49. Indeed JUNO alone can yield the most precise measurements of , , and , at the sub-percent precision48 for the first time. Therefore, JUNO will lead the precision of about half of neutrino oscillation parameters.

Figure 1.

JUNO neutrino bi-oscillation spectral distorsion. JUNO was designed to exploit the spectral distortions from two oscillations simultaneously manifesting via reactor neutrinos in a baseline of 53 km. and drive the slow and large amplitude ( 42%) disappearance oscillation with a minimum at 2 MeV visible energy. The fast and smaller amplitude ( 5%) disappearance oscillation is driven by and instead. The oscillation frequency pattern depends on ’s sign, thus directly sensitive to mass ordering (MO) via only vacuum oscillations. JUNO’s high statistics allow shape-driven neutrino oscillation parameter extraction, with minimal impact from rate-only systematics. Hence, high precision is possible without permanent reactor flux monitoring, often referred to as near detector(s). JUNO’s shape analysis relies on the reactor reference spectrum’s excellent control, implying high resolution, energy scale control, and a robust data-driven reference spectrum obtained with TAO47, a satellite experiment of JUNO. The here presented plot is for illustration purposes and the neutrino oscillation parameters are taken from NuFit5.0 (Table 1).

However, JUNO has been designed to yield a unique MO sensitivity via vacuum oscillation upon the spectral distortion analysis formulated in terms of and (or ). JUNO’s MO sensitivity relies on a challenging experimental articulation for the accurate control of the spectral shape-related systematics arising from energy resolution, energy scale control (nonlinearities being the most important), and even the reactor reference spectra to be measured independently by the TAO experiment47. The nominal intrinsic MO sensitivity is ( ) upon 6 years of data taking. All JUNO inputs to this paper follow the JUNO collaboration prescription24, including . Hence, JUNO alone is unable to resolve MO with high level of confidence ( ) in a reasonable time. In our simplified approach, we shall characterise JUNO by a simple = . The uncertainty aims to illustrate possible minor variations in the final sensitivity due to the experimental challenges behind or improvements in the analysis.

Mass ordering resolution power in LBB-II

In all LBB experiments, the intrinsic MO sensitivity arises via the appearance channel (AC), from the transitions and ; also sensitive to . MO manifests as an effective fake CPV effect or bias. This effect causes the oscillation probabilities to be different for neutrino and anti-neutrinos even under CP-conserving solutions. It is not trivial to disentangle the genuine () and the faked CPV terms. Two main strategies exist, based on the fake component, which is to be either (a) minimised (i.e. shorter baseline, like T2K, 295 km) enabling to measure mainly or (b) maximised (i.e. longer baseline), so that matter effects are strong enough to disentangle them from the , and both can be measured simultaneously exploiting spectral information from the second oscillation maximum. The latter implies baselines km, best represented by DUNE (km). NOvA’s baseline (km) remains a little too short for a full disentangling ability. Still, NOvA remains the most important LBB to date with sizeable intrinsic MO sensitivity due to its relatively large matter effects as compared to T2K.

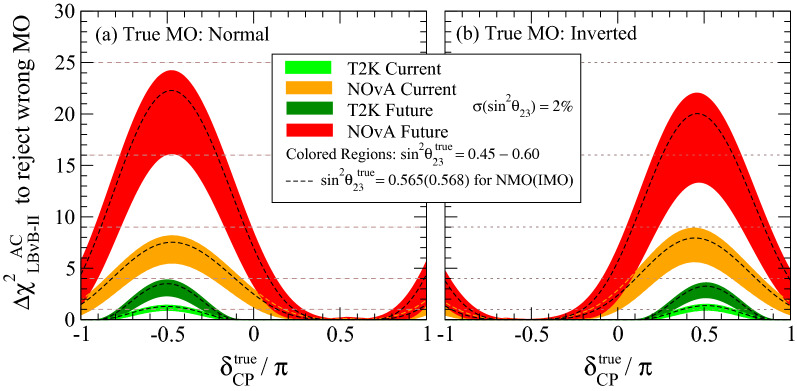

Figure 2 shows the current and future intrinsic MO sensitivities of LBB-II experiments, including their explicit and dependencies. The obtained MO sensitivities were computed using a simplified strategy where the AC was treated as rate-only (i.e., one-bin counting) analysis, thus neglecting any shape-driven sensitivity gain. This approximation is remarkably accurate for off-axis beams (narrow spectrum), especially in the low statistics limit, where the impact of systematics remains small (here neglected). The background subtraction was accounted for and tuned to the latest experiments’ data. To corroborate our estimate’s accuracy, we reproduced the LBB-II latest results20, as detailed in Appendix A.

Figure 2.

LBB-II mass ordering sensitivity. The Mass Ordering (MO) sensitivity of LBB-II experiments via the appearance channel (AC), constrained to a range of , is shown as a function of the “true” value of . The bands represent the cases where the “true” value of lies within the interval [0.45, 0.60] with a relative experimental uncertainty of 2%. The (0.45) gives the maximum (minimum) sensitivity for a given value of . The black dashed curves indicate the NuFit5.0 best fitted value. The NMO and IMO sensitivities are illustrated respectively in the (a) and (b) panels. The sensitivity arises from the fake CPV effect due to matter effects, proportional to the baseline (L). The strong dependence on is due to the unavoidable degeneracy between NMO and IMO, thus causing the sensitivity to swig by 100%. T2K, now (light green) and future (dark green), exhibits minimal intrinsic sensitivity due to its shorter baseline ( km). Instead, NOvA, now (orange) and future (red), hold leading order MO information due to its larger baseline ( km). The future full exposure for T2K and NOvA implies times more statistics relative to today. These curves are referred to as and were derived from data as detailed in Appendix A.

While NOvA AC holds significant intrinsic MO information, it is unlikely to resolve ( 25) alone. This outcome is similar to that of JUNO. Of course, the natural question may be whether their combination could yield the full resolution. Unfortunately, as it will be shown, this is unlikely but not far. Therefore, in the following, we shall consider their combined potential, along with T2K, to provide the extra missing push. This may be somewhat counter-intuitive since T2K has just been shown to hold minimal intrinsic MO sensitivity, i.e., 4 units of . Indeed, T2K, once combined, has an alternative path to enhance the overall sensitivity, which is to be described next.

Synergetic mass ordering resolution power

A remarkable synergy exists between JUNO and LBB experiments thanks to their complementarity24,43–45,50,51. In this case, we shall explore the contribution via the LBB’s disappearance channel (DC), i.e., the transitions and . This might appear counter-intuitive, since DC is practically blinded (i.e. variations ) to MO, as shown in Appendix-B.

Instead, the LBB DC provides a precise complementary measurement of . This information unlocks a mechanism, described below, enabling the intrinsic MO sensitivity of JUNO to be enhanced by the external information. This highly non-trivial synergy may yield a MO leading order role but introduces new dependences, also explored below.

Both JUNO and LBB analyse data in the 3 framework to directly provide (or ) as output. The 2 approximation leads to effective observables, such as and 43 detailed in Appendix-C. A CP-driven ambiguity limits the LBB DC information precision on the measurement if LBB AC measurements are not taken into account. The role of this ambiguity is small, but not entirely negligible and will be detailed below. The dominant LBB-II’s precision is today per experiment52,53. The combined LBB-II global precision on is already 21. Further improvement below 1.0% appears possible within the LBB-II era when integrating the full luminosities53,54. An average precision of is reachable only upon the next LBB-III generation. Instead, JUNO precision on is expected to be well within the sub-percent () level24,55.

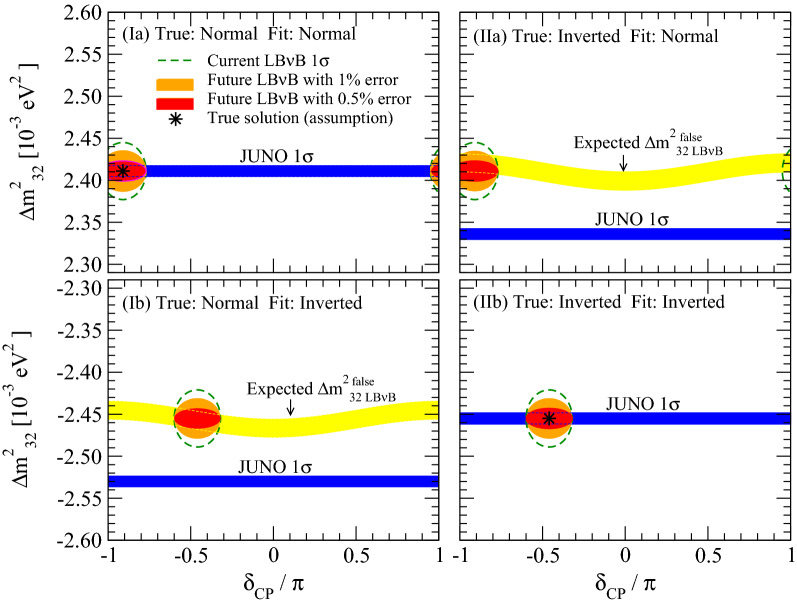

The essence of the synergy is described here. Upon 3 analysis, both JUNO and LBB experiments obtain two different values for depending on the assumed MO. Since there is only one true solution, NMO, or IMO, the other solution is thus false. The standalone ability to distinguish between those two solutions is the intrinsic MO resolution power of each experiment. The critical observation is that the general relation between the true-false solutions is different for reactors and LBB experiments, as semi-quantitatively illustrated in Fig. 3. For a given true , its false value, referred to as , as detailed in Appendix C. This implies that both JUNO and LBB based experiments generally have 2 solutions corresponding to NMO and IMO, illustrated in Fig. 3 by the region delimited by the dashed green ellipses for the current LBB data and blue bands for JUNO. The yellow bands indicate the possible range of false values expected from LBB, including a dependence, if the current best fit is turned out to be true.

Figure 3.

Origin of MO Boosting by LBB for JUNO. Semi-quantitative and schematic illustration of the LBB JUNO MO resolution synergy is shown for the cases where the true MO is normal (left panels) or inverted (right panels). For each case, the true values of are assumed to coincide with the NuFit5.0 best fitted values indicated by the black asterisk symbols. For each assumed true value of , possible range of the false values of to be determined from LBB DC is indicated by the yellow color bands where their width reflects the ambiguity due to the CP phase (see Appendix C). The approximate current 1 allowed ranges of () from NuFit5.0 are indicated by the dashed green curve whereas the future projections assuming the current central values with 1% (0.5%) uncertainty of are indicated by filled orange (red) color. Expected 1 ranges of from JUNO alone are indicated by the blue color bands though the ones in the wrong MO region would be disfavored at confidence level (CL) by JUNO itself. When the MO which is assumed in the fit coincides with the true one, allowed region of by LBB overlaps with the one to be determined by JUNO as shown in the panels I(a) and II(b). On the other hand, when the assumed (true) MO and fitted one do not coincide, the expected (false) values of by LBB and JUNO do not agree, as shown in the panels I(b) and II(a), disfavouring these cases, which is the origin of what we call the boosting effect in this paper.

All experiments must agree on the unique true solution. Consequently, the corresponding JUNO () and LBB () false solutions will differ if the overall precision allows their relative resolution. The ability to distinguish (or separate) the false solutions, or mismatch of 2 false solutions, seen in the panels (Ib) and (IIa) in Fig. 3, can be exploited as an extra dedicated discriminator expressed by the term:

| 1 |

This term characterises the rejection of the false solutions (either NMO or IMO) through an hyperbolic dependence on the overall precision. The derived MO sensitivity enhancement may be so substantial that it can be regarded and as a potential boost effect in the MO sensitivity.

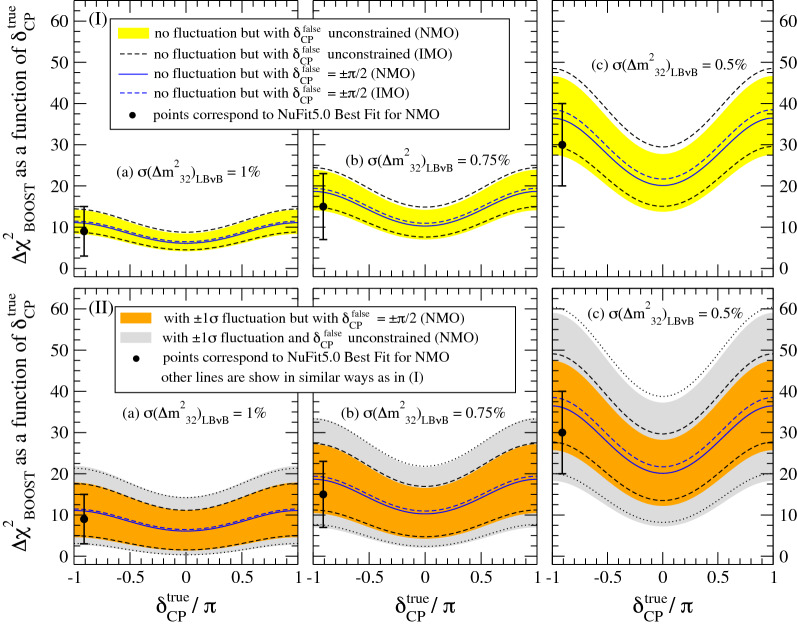

The JUNO-LBB boosting synergy exhibits four main features as illustrated in Fig. 4:

Figure 4.

JUNO and LBB mass ordering synergy dependences. The isolated synergy boosting term obtained from the combining JUNO and LBB experiments is represented by , as approximately shown in Eq. (1), see Appendix-C for details. depends on the true value of and precision, where uncertainties are considered: 1.0% (a), 0.75% (b) and 0.5% (c). The term is almost identical for both NMO and IMO solutions. Two specific effects lead the uncertainty in the a priori prediction on . (I) illustrates only the ambiguity of the CP phase (yellow band) impact whereas (II) shows only the impact of the fluctuations of , as measured by LBB (orange band). The JUNO uncertainty on is considered to be less than . The grey bands in (II) show when both effects are taken into account simultaneously. The mean value of the term increases strongly with the precision on . The uncertainties from CP phase ambiguity and fluctuation could deteriorate much of the a priori gain on the prospected sensitivities. fluctuations dominate, while the ambiguity is only noticeable for the best precision. The use of NuFit5.0 data (black point) eliminates the impact of the prediction ambiguity while the impact of remains as fluctuations cannot be predicted a priori. Today’s favoured maximises the sensitivity gain via the term. When quoting sensitivities, we shall consider the lowest bound as the most conservative case.

Major increase (boost) potential of the combined MO sensitivity. This is realised by the new pull term, shown in Eq. (1) and illustrated in Fig. 4, which is to be added to the intrinsic MO discrimination terms per experiment as it will be described later on in Figs. 5, 6, 7.

Dependence on the precision of . Again, this is described explicitly in Eq. (1). The leading order effect is the uncertainty on . This typically referred to as as this largely dominates due to its poorer precision as compared to that obtained by JUNO ( 0.5%) even within about a year of data-taking. Three cases are explored in this work, (a) 1.0% (i.e. close to today’s precision), (b) 0.75% and (c) 0.5% (ultimate precision). Figure 4 exhibits a strong dependence, telling us the importance of reducing the uncertainties of from LBB to increase the MO sensitivity. This is why T2K can have an active and important role to improve the overall MO sensitivity.

Impact of fluctuations. In order to be accurately predictive, it is important to evaluate the impact of the unavoidable fluctuations due to the today’s data uncertainties on as well as on the ambiguity (see below description). All these effects are quantified and explained in Fig. 4 by the orange bands, thus representing the data fluctuations of from LBB can significantly impact the boosted MO sensitivity.

δCP Ambiguity dependence. The main consequence is to limit the predictability of , even if the assumed true value of the CP phase is fixed or limited to very narrow range. Its effect is less negligible as the LBB precision on improves (0.5%), as shown by the yellow bands in (I) and by the gray band in (II) of Fig. 4. However, by considering the determined by the global fit like NuFit5.0, we can reduce this ambiguity as the best fitted values for NMO and IMO also reflect the most likely values of maximising our predictions’ accuracy to the most probable parameter-space, as favoured by the latest world neutrino data [despite that defined by Eqs. (15) and (16) in Appendix-C does not depend explicitly on the CP phase, we are implicitly using the CP phase information since the best fitted coming from the global analysis carry the informtion on through the LBBAC data used in the global analysis].

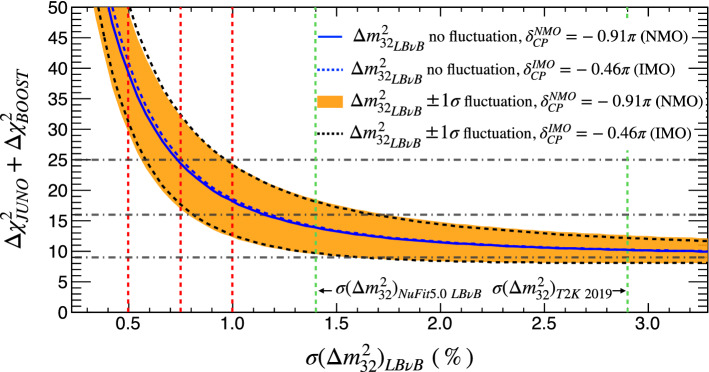

Figure 5.

JUNO mass ordering sensitivity boosting. A significant increase of JUNO intrinsic sensitivity () is possible exploiting the LBB’s disappearance (DC) characterised by depending strongly on the uncertainty of . Today’s NuFit5.0 average LBB-II’s precision on is . A rather humble 1.0% precision is possible, consistent with doubling the statistics if systematics allowed. Since NOvA and T2K are expected to increase their exposures by about factors of before the shutdown, sub-percent precision may also be within reach. While the ultimate precision is unknown, we shall consider a precision to illustrate this possibility. So, JUNO alone (intrinsic + boosting) could yield a (i.e., 16) MO sensitivity, at 84% probability, within the LBB-II era. A 5 potential may not be impossible, depending on fluctuations. Similarly, JUNO may further increase in significance to resolve ( or ) a pure vacuum oscillations MO measurement in combination with the LBB-III’s information.

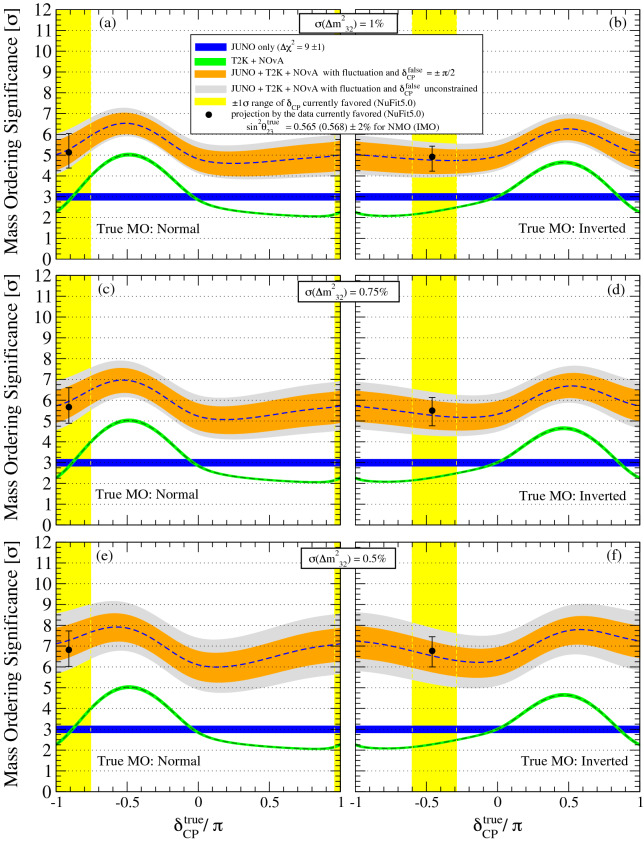

Figure 6.

The combined mass ordering sensitivity. The combination of the MO sensitive of JUNO and LBB-II is illustrated for six difference configurations: NMO (left), IMO (right) considering the LBB uncertainty on to 1.0% (top), 0.75% (middle) and 0.5% (bottom). The NuFit5.0 favoured value is set for with an assumed 2% experimental uncertainty. The intrinsic MO sensitivities are shown for JUNO (blue) and the combined LBB-II (green), the latter largely dominated by NOvA. The JUNO sensitivity boosts when exploiting the LBB’s additional information via the term, described in Fig. 4 but not shown here for illustration simplicity. The orange and grey bands illustrate the presence of the boosting term prediction effects, respectively, the fluctuation of and the ambiguity in addition. T2K impacts mainly via the precision of and the measurement of . The combined sensitivity suggests a mean (dashed blue line) significance for any value of even for the most conservative 1%. However, a robust significance at 84% probability (i.e. including fluctuations) seems possible, if the currently preferred value of and NMO remain favoured by data, as indicated by the yellow band and black point (best fit). Further improvement in the precision of translates into a better MO resolution potential.

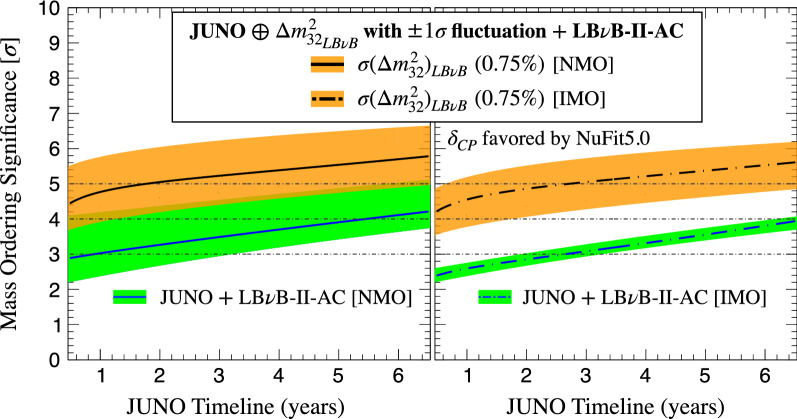

Figure 7.

Mass ordering sensitivity and possible resolution timeline. Since all the NOvA and T2K data are expected to be accumulated by 202457 and 202652, the combined sensitivity follows JUNO data availability. JUNO is expected to start in 2023, reaching its statistically dominated nominal MO sensitivity (9 units of ) within 6 years. We illustrate the NMO (plot on the left) and IMO (plot on the right) scenarios. The sensitivity evolution depends mainly on JUNO once boosted, where 0.75% uncertainty (black line) is considered. The effect of fluctuations is indicated (orange bands), including that of the variance due to the data favoured region for (green band). The larger band of the NMO is caused by contribution of the LBB-II experiments, whose contribution is rather negligible for opposite IMO. Since JUNO boosted dominates, the sensitivities are almost independent of NMO and IMO solutions (left), this also demonstrating the humble overall impact of the AC channel (NOvA mainly) of the LBB-II experiments upon combination. The mean significance is expected to reach the level, including fluctuations and degeneracies (i.e., 84% probability) for both MO solutions, where the precision on is the leading order term. In fact, a 5 measurement may be possible, at 50% probability, within 3 years of JUNO data taking start once combined. In the end, JUNO data may prescind entirely from the LBB’s AC information (minor impact), thus enabling a fully resolved pure vacuum oscillation MO measurement.

In brief, when combining JUNO and the LBB experiments, the overall sensitivity works as if JUNO’s intrinsic sensitivity gets boosted, via the external information. This is further illustrated and quantified in Fig. 5, as a function of the precision on despite the sizeable impact of fluctuations. The LBB intrinsic AC contribution will be added and shown in the next section. It is also demonstrated that the DC information of the LBB’s, via the boosting, play a significant role in the overall MO sensitivity. However, this improvement cannot manifest without JUNO – and vice versa. For an average precision on below 1.0%, even with fluctuations, the boosting effect can be already considerable. A precision as good as may be accessible by LBB-II while the LBB-III generation is expected to go up to level.

Since the exploited DC information is practically blinded to matter effects [the measurement of depends slightly on , obtained via the AC information, itself sensitive to matter effects], the boosting synergy effect remains dominated by JUNO’s vacuum oscillations nature. For this reason, the sensitivity performance is almost identical for both NMO and IMO solutions, in contrast to the sensitivities obtained from solely matter effects, as shown in Fig. 2. This effect is especially noticeable in the case of atmospheric data. The case of T2K is particularly illustrative, as its impact on MO resolution is essentially only via the boosting term mainly, given its small intrinsic MO information obtained by AC data. This combined MO sensitivity boost between JUNO and LBB (or atmospherics) is likely one of the most elegant and powerful examples so far seen in neutrino oscillations, and it is expected to play a significant role for JUNO to yield a leading impact on the MO quest, as described next. In fact, the JUNO collaboration has already considered this effect when claiming its possible median MO sensitivity to be 4 potential24,44. However, JUNO prediction does not account for the fluctuations. This work adds the impact of fluctuations and ambiguity on the MO discovery potential of JUNO upon boosting. Our results are however consistent if used the same assumptions, as described in Appendix D.

Simplified combination rationale

The combined MO sensitive of JUNO together with LBB-II experiments (NOvA and T2K) can be obtained from the independent additive of each . Two contributions are expected: a) the LBB-II’s AC, referred to as (LBB-AC) and b) the combined JUNO and LBB-II’s DC, referred to as (JUNOLBB-DC). All terms were described in the previous sections [we use in this work the terminologies, AC (appearance channel) and DC (disappearance channel) for simplicity. This does not mean that the relevant information is coming only from AC or DC, but that (LBB-AC) comes dominantly from LBB AC whereas (JUNOLBB-DC) comes dominantly from JUNO + LBB DC]. Hence the combination can be represented as = (JUNOLBB-DC) + (LBB-AC), illustrated in Fig. 6, where the orange and grey bands represent, respectively, the effects of the fluctuations and the CP-phase ambiguity. Figure 6 quantifies the MO sensitivity in terms of significance (i.e., numbers of ’s) obtained as quantified in all previous plots. Again, both NMO and IMO solutions are considered for 3 different cases for the LBB uncertainty on .

- The (LBB-II-AC) Term:

this is the intrinsic MO combined information, largely dominated by NOvA’s AC, as described in Fig. 2. The impact of T2K () is minimal, but on the verge of resolving MO for the first time, T2K may still help here. As expected, this depends on and strongly on . This is shown in Fig. 6 by the light green band. We note that when T2K and NOvA are combined, there is significance enhancement in the positive (negative) range of for NMO (IMO) which is not naively expected from Fig. 2. This extra gain of sensitivity for the T2K and NOvA combined case comes from the difference of the matter effects on these experiments, and can be seen, e.g., in Figure 21 of Ref.56. The complexities of possible correlations and systematics handling of a hypothetical NOvA and T2K combination are disregarded in our study, but they are integrated within the combination of the LBB-II term, now obtained from NuFit5.0. The full NOvA data is expected to be available by 202457, while T2K will run until 202652, upon the beam upgrades (T2K-II) aiming for HK.

- The (JUNOLBB-DC) Term:

this term can be regarded itself as composed of two contributions. The first part is the JUNO intrinsic information, i.e., = units after 6 years of data-taking. This contribution is independent of and , as shown in Fig. 6, represented by the blue band. The second part is the JUNO boosting term, shown explicitly in Fig. 4, including its generic dependencies, such as the true value of . This term exhibits strong modulation with and uncertainty of , as illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5. The (JUNOLBB-DC) term strongly shapes the combined curves (orange). Indeed, this term causes the leading variation across Fig. 6 for the different cases of the uncertainty of : (a) 1.0% (top), reachable by LBB-II53,54, (b) 0.75% (middle), maybe reachable (i.e. optimistic) by LBB-II and (c) 0.5% (bottom), which is only reachable by the LBB-III generation31,32.

The combination of the JUNO, AC, and DC inputs from LBB-II experiments appears on the verge of achieving the first MO resolved measurement with a sizeable probability. The combination’s ultimate significance is likely to mainly depend on the final uncertainty on obtained by LBB experiments. The discussion of the results and implications, including limitations, is addressed in the next section.

Implications and discussion

Possible implications arising from the main results summarised in Fig. 6 deserved some extra elaboration and discussion for a more accurate contextualisation, including a possible timeline and highlight the limitations associated with our simplified approach. These are the main considerations:

-

MO global data trend: Today’s reasonably high significance, not far from the level to be reached by intrinsic sensitivities of JUNO or NOvA, is obtained by the most recent global analysis21 which favours NMO up to . However, this significance lowers to without SK atmospherics data, thus proving their crucial value to the global MO knowledge today. The remaining aggregated sensitivity integrates over all other experiments. However, the global data preference is somewhat fragile, still varying between NMO and IMO solutions17,21,58.

The reason behind this is actually the corroborating manifestation of the alluded complementarity between LBB-II and reactors [before JUNO starts, the reactor experiments stand for Daya Bay, Double Chooz, and RENO, whose lower precision on is 2%] experiments. Indeed, while the current LBB data alone favour IMO, the match in measurements by LBB and reactors tend to favour the case of NMO, which is this overall solution obtained upon combination. Hence, the MO solution currently flips due to the reactor-LBB data interplay, despite the sizeable uncertainty fluctuations as compared to the aforementioned scenario where JUNO will be on, indicating it’s crucial contribution. This effect, expected since43, is at the heart of the described boosting mechanism and has started manifesting earlier on. This can be regarded as the first data-driven manifestation of the aforementioned effect.

Atmospherics extra information: We did not account for atmospheric neutrino input, such as the running SK and IceCube experiments. They are expected to add valuable though susceptible to the aforementioned (mainly) and dependences. This contribution is more complex to replicate with accuracy due to the vast E/L phase-space; hence we disregarded it in our simplified analysis. Its importance has long been proved by SK dominance of much of today’s MO information. So, all our conclusions can only be enhanced by adding the missing atmospheric contribution. Future ORCA and PINGU have the potential to yield extra MO information45, while their combinations with JUNO data is actively studied59,60 to yield full MO resolution.

-

Inter-experiment full combination: A complete strategy of data-driven combination between JUNO and LBB-II experiments will be beneficial in the future [during the final readiness of our work, one such a combination was reported61 using a different treatment (excluding fluctuations). While their qualitative conclusions are consistent with our studies, there may still be numerical differences left to be understood]. Ideally, this may be an official inter-collaboration effort to carefully scrutinise the possible impact of systematics and correlations, involving both experimental and theoretical physicists in such studies (see e.g.51). We do not foresee a significant change in our findings by a more complex study, including the highlighted MO discovery potential due to today’s data and knowledge limitations.

Our approach did not merely demonstrate the numerical yield of the combination between JUNO and LBB, but our goal was also to illustrate and characterise the different synergies manifesting therein. Our study focuses on the breakdown of all the relevant contributions in the specific and isolated cases of the MO sensitivity combination of the leading experiments. The impact of the was isolated, while its effect is otherwise transparently accounted for by any complete 3 formulation, such as done by NuFit5.0 or other similar analyses. Last, our study was tuned to the latest data to maximise the accuracy of predictability, which is expected to be order around the 5 range.

-

Hypothetical MO resolution timeline: One of the main observations upon this study is that the MO could be fully resolved, maybe even comfortably, by the JUNO, NOvA and T2K combination. The NMO solution discovery potential, considering today’s favoured , has a probability of () for a precision of up to 1.0% (0.75%). In the harder IMO, the sensitivity may reach a mean of potential only if the uncertainty was as good as . Within a similar time scale, the atmospheric data is expected to add up to enable a full resolution for both solutions. If correct, this is likely to become the first fully resolved MO measurement and it is expected to be tightly linked to the JUNO data timeline, as described in Fig. 7, which sets the timeline to be between 2026–2028.

Such a combined MO measurement can be regarded as a “hybrid” between vacuum (JUNO) and matter driven (mainly NOvA) oscillations. In this context, JUNO and NOvA are, unsurprisingly, the leading experiments. Despite holding little intrinsic MO sensitivity, T2K plays a key role by simultaneously a) boosting JUNO via its precise measurement of (similar to NOvA) and b) aiding NOvA by reducing the possible ambiguity phase-space. The Appearance Channel channel synergy between T2K and NOvA is expected to have very little impact.

This combined measurement relies on an impeccable data model consistency across all experiments. Possible inconsistencies may diminish the combined sensitivity. Since our estimate has accounted for fluctuations (typically, up to probability), those inconsistencies should amount to effects for them to matter. Those inconsistencies may, however, be the first manifestation of new physics62,63. Hence, this inter-experiment combination has another relevant role: to exploit the ideal MO binary parameter space solution to test for inconsistencies that may point to discoveries beyond today’s standard picture. The additional atmospherics data mentioned above, are expected to reinforce both the significance boost and the model consistency scrutiny just highlighted.

Readiness for LBB-III: in the absence of any robust model-independent for MO prediction by theory and given its unique binary MO outcome, the articulation of at least two well resolved measurements appears critical for the sake of the experimental redundancy and consistency test across the field. In the light of DUNE’s unrivalled MO resolution power, the articulation of another robust MO measurement may be considered as a priority to make the most of DUNE’s insight.

-

Vacuum versus matter measurements: since matter effects drive all experiments but JUNO, articulating a competitive and fully resolved measurement via only vacuum oscillations has been an unsolved challenge to date. Indeed, boosting JUNO sensitivity alone, as described in Figs. 4 and 5, up to remains likely impractical in the context of LBB-II, modulo fluctuations. However, this possibility is a priori feasible in combination with the LBB-III improved precision, as shown in Fig. 7 and more detailed Fig. 8. The significant potential improvement in the precision, up to order 0.5%31,32 may prove crucial. Furthermore, the comparison between two fully resolved MO measurements, one using only matter effects and one exploiting pure vacuum oscillations, is foreseen to be one of the most insightful MO coherence tests. So, the ultimate MO measurements comparison may be the DUNE’s AC alone (even after a few years of data taking) versus a full statistics JUNO boosted by the DC of HK and DUNE improving the precision. This comparison is expected to maximise the depth of the MO-based scrutiny by their stark differences in terms of mechanisms, implying dependencies, correlations, etc. The potential for a breakthrough or even discovery, exists, should a significant discrepancy manifest here. The expected improvement in the knowledge of by LBB-III experiments will also play a role in facilitating this opportunity.

This observation implies that the JUNO based MO capability, despite its a priori humble intrinsic sensitivity, has the potential to play a critical role throughout the history of MO explorations. Indeed, the first MO fully resolved measurement is likely to depend much on the JUNO sensitivity (direct and indirectly); hence JUNO should maximise ( ) or maintain its yield. However, JUNO’s ultimate role aforementioned may remain relatively unaffected even by a small loss in performance, providing the overall sensitivity remains sizeable (e.g. ), as illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6. This is because JUNO sensitivity could still be boosted by the LBB experiments by their precision on , thus sealing its legacy. There is no reason for JUNO not to perform as planned, specially given the remarkable effort for solutions and novel techniques developed, such as the dual-calorimetry, for the control and accuracy of the spectral shape64.

LBB running strategy since both AC and DC channels drive the sensitivity of LBB experiments, the maximal yield for a combined MO sensitivity implies a dedicated optimisation exercise, including the role of the sensitivity. Indeed, as shown, the precision on , measured via the DC channel, plays a leading role in the intrinsic MO resolution, which may even outplay the role of the AC data. So, forthcoming beam-mode running optimisation by the LBB collaborations could, and likely should, consider the impact to MO sensitivity. In this way, if precision was to be optimised, this will benefit from more neutrino mode running, leading typically to both larger signal rate and better signal-to-background ratio. This is particularly important for T2K and HK due to their shorter baselines. For such considerations, Fig. 5 might offer some guidance.

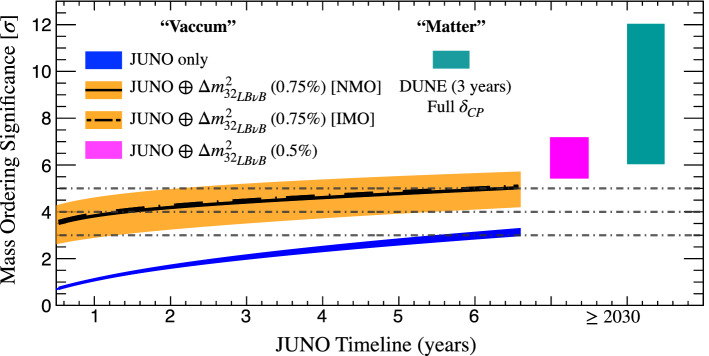

Figure 8.

Different measurements of mass ordering. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the LBB-II generation may provide major boosting of the JUNO sensitivity upon the boosting caused by precision, which is expected to be at best . The boosting effect is again illustrated as the difference between the JUNO alone (blue) and JUNO boosted (orange) curves. However, once the LBB-III generation accelerator experiments start, we expect the precision to be further enhanced up to by both DUNE and HK. At this moment, the JUNO data may only exploit this precision to ensure a fully resolved vacuum only MO measurement (magenta), which can be compared to DUNE stand-alone measurement (green). Given the possible uncertainties due to experiment schedules, etc, all we can say is possible . However, this opens for an unprecedented scenario where two as different as possible high precision MO measurements will be available to ensure the possible overall coherent of the neutrino standard phenomenology. Should discrepancies be seen, this may a smoking-gun evidence of the manifestation of new neutrino phenomenology.

Conclusions

This work presents a simplified calculation tuned to the latest world neutrino data, via NuFit5.0, to study the most important minimal level inter-experiment combinations to yield the earliest possible full MO resolution (i.e. ). Our first finding is that the combined sensitivity of JUNO, NOvA and T2K has the potential to yield the first resolved measurement of MO with timeline between 2026-2028, tightly linked to the JUNO schedule since full data samples of both NOvA and T2K data are expected to be available from . Due to the absence of any a priori MO theory based prediction and given its intrinsic binary outcome, we noted and illustrated the benefit to articulate at least two independent and well resolved () measurements of MO. This is even more important in the light of the decisive outcome from the next generation of long baseline neutrino beams experiments. Such MO measurements could be exploited to over-constrain and test the standard oscillation model, thus opening for discovery potential, should unexpected discrepancies may manifest. However, the most profound phenomenological insight using MO phenomenology is expected to be obtained by having two different and well resolved MO measurements based on only matter effects enhanced and pure vacuum oscillations experimental methodologies. While the former is driving most of the field, the challenge was to be able to articulate the latter, so far considered as impractical. Hence, we here describe the feasible path to promote JUNO’s MO measurement to reach a robust resolution level without compromising its unique vacuum oscillation nature by exploiting the next generation long baseline neutrino beams disappearance channel’s ability to reach a precision of on .

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Much of this work was originally developed in the context of our studies linked to the PhD thesis of Y.H. (APC and IJC laboratories) and to the scientific collaboration between H.N. (in sabbatical at the IJC laboratory) and A.C. Y.H. and A.C. are grateful to the CSC fellowship funding of the PhD fellow of Y.H. H.N. acknowledges CAPES and is especially thankful to CNPq and IJC laboratory for their support to his sabbatical. A.C. and L.S. acknowledge the support of the P2IO LabEx (ANR-10-LABX-0038) in the framework “Investissements d’Avenir” (ANR-11-IDEX-0003-01 – Project “NuBSM”) managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), France, where our developments are framed within the neutrino inter-experiment synergy working group. AC would like to thank also Stéphane Lavignac for useful comments and suggestions as feedback on the manuscript. The authors are grateful to JUNO’s internal reviewers who ensured that the information included in this manuscript about that experiment is consistent with its official position as conveyed in its publications. We would like to specially thank the NuFit5.0 team (Ivan Esteban, Concha Gonzalez-Garcia, Michele Maltoni, Thomas Schwetz and Albert Zhou) for their kindest aid and support to provide dedicated information from their latest NuFit5.0 version. We also would like Concha Gonzalez-Garcia and Fumihiko Suekane for providing precious feedback on a short time scale and internal review of the original manuscript.

Author contributions

A.C., H.N. and Y.H. lead the writeup of the first manuscript as well as the figures. The final version of the manuscript include important review and input by all authors to different degrees given their different inputs from different experiments, thus all authors have major impact to the overall scientific quality of the results reported. P.C. and S.D. are the editors and have led the final stages of the manuscript versioning and quality. The overall result is considered a result by all authors involved.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Pietro Chimenti, Email: pietro.chimenti@uel.br.

Stefano Dusini, Email: stefano.dusini@pd.infn.it.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-09111-1.

References

- 1.Nunokawa H, Parke SJ, Valle JWF. CP violation and neutrino oscillations. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2008;60:338–402. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pontecorvo B. Neutrino experiments and the problem of conservation of leptonic charge. Sov. Phys. JETP. 1968;26:984–988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maki Z, Nakagawa M, Sakata S. Remarks on the unified model of elementary particles. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1962;28:870–880. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zyla PA, et al. Review of particle physics. To appear PTEP. 2020;2020:083C01. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleveland BT, Daily T, Davis R, Jr, Distel JR, Lande K, Lee CK, Wildenhain PS, Ullman J. Measurement of the solar electron neutrino flux with the Homestake chlorine detector. Astrophys. J. 1998;496:505–526. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hampel W, et al. GALLEX solar neutrino observations: Results for GALLEX IV. Phys. Lett. B. 1999;447:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdurashitov JN, et al. Measurement of the solar neutrino capture rate with gallium metal. Phys. Rev. C. 1999;60:055801. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad QR, et al. Direct evidence for neutrino flavor transformation from neutral current interactions in the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:011301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.011301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda S, et al. Solar B-8 and hep neutrino measurements from 1258 days of Super-Kamiokande data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:5651–5655. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.5651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eguchi K, et al. First results from KamLAND: Evidence for reactor anti-neutrino disappearance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;90:021802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.021802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikheyev SP, Smirnov AY. Resonance amplification of oscillations in matter and spectroscopy of solar neutrinos. Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 1985;42:913–917. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfenstein L. Neutrino oscillations in matter. Phys. Rev. D. 1978;17:2369–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolinski MJ, Poon AWP, Rodejohann W. Neutrinoless double-beta decay: Status and prospects. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2019;69:219–251. [Google Scholar]

- 14.King SF. Neutrino mass models. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2004;67:107–158. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dighe AS, Yu A, Smirnov Identifying the neutrino mass spectrum from the neutrino burst from a supernova. Phys. Rev. D. 2000;62:033007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannestad S, Schwetz T. Cosmology and the neutrino mass ordering. JCAP. 2016;11:035. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esteban I, Gonzalez-Garcia MC, Hernandez-Cabezudo A, Maltoni M, Schwetz T. Global analysis of three-flavour neutrino oscillations: Synergies and tensions in the determination of , , and the mass ordering. JHEP. 2019;01:106. [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Salas PF, Forero DV, Gariazzo S, Martínez-Miravé P, Mena O, Ternes CA, Tórtola M, Valle JWF. 2020 global reassessment of the neutrino oscillation picture. JHEP. 2021;02:071. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capozzi F, Lisi E, Marrone A, Palazzo A. Current unknowns in the three neutrino framework. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2018;102:48–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The XXIX International Conference on Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics, Neutrino 2020, June 22–July 2, 2020. https://conferences.fnal.gov/nu2020/, (2020).

- 21.Esteban I, Gonzalez-Garcia MC, Maltoni M, Schwetz T, Zhou A. The fate of hints: Updated global analysis of three-flavor neutrino oscillations. JHEP. 2020;09:178. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blennow M, Coloma P, Huber P, Schwetz T. Quantifying the sensitivity of oscillation experiments to the neutrino mass ordering. JHEP. 2014;03:028. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petcov ST, Piai M. The LMA MSW solution of the solar neutrino problem, inverted neutrino mass hierarchy and reactor neutrino experiments. Phys. Lett. B. 2002;533:94–106. [Google Scholar]

- 24.An F, et al. Neutrino physics with JUNO. J. Phys. G. 2016;43(3):030401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y-F, Wang Y, Xing Z. Terrestrial matter effects on reactor antineutrino oscillations at JUNO or RENO-50: How small is small? Chin. Phys. C. 2016;40(9):091001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahn MH, et al. Indications of neutrino oscillation in a 250 km long baseline experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;90:041801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamson P, et al. Improved search for muon-neutrino to electron-neutrino oscillations in MINOS. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;107:181802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.181802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agafonova N, et al. Observation of a first candidate in the OPERA experiment in the CNGS beam. Phys. Lett. B. 2010;691:138–145. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayres, D.S. et al. NOvA: Proposal to Build a 30 Kiloton Off-Axis Detector to Study Oscillations in the NuMI Beamline, FERMILAB-PROPOSAL-0929, arXiv:hep-ex/0503053. (2004).

- 30.Abe K, et al. The T2K experiment. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A. 2011;659:106–135. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abi, Babak et al. Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), Far Detector Technical Design Report, Volume II DUNE Physics. arXiv:2002.03005 [hep-ex]. (2020).

- 32.Abe, K. et al. Hyper-Kamiokande Design Report, arXiv:1805.04163 [physics.ins-det]. (2018).

- 33.Abe K, et al. Physics potentials with the second Hyper-Kamiokande detector in Korea. PTEP. 2018;2018(6):063C01. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuda Y, et al. Evidence for oscillation of atmospheric neutrinos. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998;81:1562–1567. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aartsen MG, et al. Determining neutrino oscillation parameters from atmospheric muon neutrino disappearance with three years of IceCube DeepCore data. Phys. Rev. D. 2015;91(7):072004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed S, et al. Physics potential of the ICAL detector at the India-based Neutrino Observatory (INO) Pramana. 2017;88(5):79. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulrich F. Katz. The ORCA Option for KM3NeT. arXiv:1402.1022 [astro-ph.IM]. PoS, (2014).

- 38.Aartsen, M.G. et al. Letter of Intent: The Precision IceCube Next Generation Upgrade (PINGU). arXiv:1401.2046 [physics.ins-det]. (1 2014).

- 39.Fogli GL, Lisi E. Tests of three flavor mixing in long baseline neutrino oscillation experiments. Phys. Rev. D. 1996;54:3667–3670. doi: 10.1103/physrevd.54.3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adey D, et al. Measurement of the electron antineutrino oscillation with 1958 days of operation at Daya bay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;121(24):241805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.241805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Kerret H, et al. Double Chooz measurement via total neutron capture detection. Nat. Phys. 2020;16(5):558–564. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bak G, et al. Measurement of reactor antineutrino oscillation amplitude and frequency at RENO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;121(20):201801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.201801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nunokawa H, Parke SJ, Funchal RZ. Another possible way to determine the neutrino mass hierarchy. Phys. Rev. D. 2005;72:013009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y-F, Cao J, Wang Y, Zhan L. Unambiguous determination of the neutrino mass hierarchy using reactor neutrinos. Phys. Rev. D. 2013;88:013008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blennow M, Schwetz T. Determination of the neutrino mass ordering by combining PINGU and Daya Bay II. JHEP. 2013;09:089. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandyopadhyay A. Physics at a future Neutrino Factory and super-beam facility. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2009;72:106201. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abusleme, A. et al. TAO Conceptual Design Report: A Precision Measurement of the Reactor Antineutrino Spectrum with Sub-percent Energy Resolution. arXiv:2005.08745 [physics.ins-det]. (2020).

- 48.Abusleme, A. et al. JUNO Physics and Detector. arXiv:2104.02565 [hep-ex]. (2021).

- 49.Choubey S, Petcov ST, Piai M. Precision neutrino oscillation physics with an intermediate baseline reactor neutrino experiment. Phys. Rev. D. 2003;68:113006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Minakata H, Nunokawa H, Parke SJ, Funchal RZ. Determining neutrino mass hierarchy by precision measurements in electron and muon neutrino disappearance experiments. Phys. Rev. D. 2006;74:053008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forero, D. V., Parke, S. J., Ternes, C. A. & Funchal, Renata Zukanovich. JUNO’s prospects for determining the neutrino mass ordering. arXiv:2107.12410 [physics.hep-ph]. (2021).

- 52.Talk presented by Patrick Dunne at The XXIX International Conference on Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics, Neutrino 2020, June 22–July 2, 2020. https://conferences.fnal.gov/nu2020/, (2020).

- 53.Acero, M. A. et al. An Improved Measurement of Neutrino Oscillation Parameters by the NOvA Experiment, arXiv:2108.08219 [hep-ex]. (2021).

- 54.Abe, K. et al. Sensitivity of the T2K accelerator-based neutrino experiment with an Extended run to POT, arXiv:1607.08004 [hep-ex]. (2016).

- 55.Athar, M. S. et al. IUPAP Neutrino Panel White Paper. https://indico.cern.ch/event/1065120/contributions/4578196/attachments/2330827/3971940/Neutrino_Panel_White_Paper.pdf, (2021).

- 56.Abe K, et al. Neutrino oscillation physics potential of the T2K experiment. PTEP. 2015;2015(4):043C01. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Talk presented by Alex Himmel at The XXIX International Conference on Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics, Neutrino 2020, June 22–July 2, 2020. https://conferences.fnal.gov/nu2020/, (2020).

- 58.Kelly KJ, Machado PAN, Parke SJ, Perez-Gonzalez YF, Funchal RZ. Neutrino mass ordering in light of recent data. Phys. Rev. D. 2021;103(1):013004. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aartsen MG, et al. Combined sensitivity to the neutrino mass ordering with JUNO, the IceCube Upgrade, and PINGU. Phys. Rev. D. 2020;101(3):032006. [Google Scholar]

- 60.KM3NeT-ORCA and JUNO combined sensitivity to the neutrino masse ordering. Poster presented by Chau, Nhan. The XXIX International Conference on Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics. Neutrino 2020, June 22–July 2, 2020. https://conferences.fnal.gov/nu2020/, (2020).

- 61.Cao S, Nath A, Ngoc TV, Quyen PT, Van NTH, Francis NK. Physics potential of the combined sensitivity of T2K-II, NOA extension, and JUNO. Phys. Rev. D. 2021;103(11):112010. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Denton PB, Gehrlein J, Pestes R. -Violating neutrino nonstandard interactions in long-baseline-accelerator data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021;126(5):051801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.051801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Capozzi F, Chatterjee SS, Palazzo A. Neutrino mass ordering obscured by nonstandard interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020;124(11):111801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.111801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abusleme A, et al. Calibration strategy of the JUNO experiment. JHEP. 2021;03:004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.