Key Points

Question

Can analysis of cardiac ultrasound by machine learning methods help in the differentiation of cardiovascular diseases?

Findings

In this cohort study including 448 patients (228 for derivation and 220 for control) with takotsubo syndrome (TTS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI), a machine learning system was established. The system achieved the ability to outperform a committee of cardiologists in distinguishing TTS from AMI.

Meaning

These findings suggest that the machine learning system may have utility in gaining insights into the dynamics of diseased heart function.

Abstract

Importance

Machine learning algorithms enable the automatic classification of cardiovascular diseases based on raw cardiac ultrasound imaging data. However, the utility of machine learning in distinguishing between takotsubo syndrome (TTS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has not been studied.

Objectives

To assess the utility of machine learning systems for automatic discrimination of TTS and AMI.

Design, Settings, and Participants

This cohort study included clinical data and transthoracic echocardiogram results of patients with AMI from the Zurich Acute Coronary Syndrome Registry and patients with TTS obtained from 7 cardiovascular centers in the International Takotsubo Registry. Data from the validation cohort were obtained from April 2011 to February 2017. Data from the training cohort were obtained from March 2017 to May 2019. Data were analyzed from September 2019 to June 2021.

Exposure

Transthoracic echocardiograms of 224 patients with TTS and 224 patients with AMI were analyzed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the machine learning system evaluated on an independent data set and 4 practicing cardiologists for comparison. Echocardiography videos of 228 patients were used in the development and training of a deep learning model. The performance of the automated echocardiogram video analysis method was evaluated on an independent data set consisting of 220 patients. Data were matched according to age, sex, and ST-segment elevation/non-ST-segment elevation (1 patient with AMI for each patient with TTS). Predictions were compared with echocardiographic-based interpretations from 4 practicing cardiologists in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and AUC calculated from confidence scores concerning their binary diagnosis.

Results

In this cohort study, apical 2-chamber and 4-chamber echocardiographic views of 110 patients with TTS (mean [SD] age, 68.4 [12.1] years; 103 [90.4%] were female) and 110 patients with AMI (mean [SD] age, 69.1 [12.2] years; 103 [90.4%] were female) from an independent data set were evaluated. This approach achieved a mean (SD) AUC of 0.79 (0.01) with an overall accuracy of 74.8 (0.7%). In comparison, cardiologists achieved a mean (SD) AUC of 0.71 (0.03) and accuracy of 64.4 (3.5%) on the same data set. In a subanalysis based on 61 patients with apical TTS and 56 patients with AMI due to occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery, the model achieved a mean (SD) AUC score of 0.84 (0.01) and an accuracy of 78.6 (1.6%), outperforming the 4 practicing cardiologists (mean [SD] AUC, 0.72 [0.02]) and accuracy of 66.9 (2.8%).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, a real-time system for fully automated interpretation of echocardiogram videos was established and trained to differentiate TTS from AMI. While this system was more accurate than cardiologists in echocardiography-based disease classification, further studies are warranted for clinical application.

This cohort study assesses the utility of a fully automated and interpretable machine learning–based framework in differentiating takotsubo syndrome from acute myocardial infarction using raw echocardiographic imaging data.

Introduction

Precision medicine aims to deliver individually adapted medical diagnostics and treatment to patients with cardiovascular diseases. In particular, use of machine learning can assist in providing precision cardiovascular medicine in diagnostics by analyzing unstructured data, detecting patterns, and then making diagnostic or prognostic predictions on new data in a standardized way.1

Several deep learning algorithms have been advocated for cardiovascular disease diagnosis and prediction, including prediction of cardiovascular risk factors from retinal fundus photographs,2 discrimination of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from physiological hypertrophy of athletes using echocardiography,3 cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection using electrocardiograms, and the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction using left-ventricular long-axis myocardial velocity patterns.4

Despite the ready availability of echocardiography, few studies to date have been conducted on its interpretation with support of machine learning algorithms.5,6,7 The applicability of machine learning models remains limited due to their black-box nature. This interpretation problem is particularly relevant in medicine, where the reasons to support a certain prediction often match the value of the prediction itself. Furthermore, all state-of-the art pipelines require human assistance, for instance, manual tracing of cardiac structures. Previously, echocardiographic cardiovascular disease classification based on deep learning has been applied using output data from speckle-tracking echocardiography.3,8

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) is characterized by acute ventricular dysfunction, which can result in severe adverse effects, including death.9,10,11 Patients with TTS typically present signs and symptoms similar to acute myocardial infarction (AMI),10,12,13 rendering differential diagnosis challenging. Early recognition of TTS has important implications in clinical practice for appropriate clinical and therapeutic management. Nonetheless, to date, reliable and widely accepted criteria for a differential diagnosis of TTS based on echocardiographic features are lacking.14

The aims of the present study are to develop a fully automated and interpretable machine learning–based framework capable of differentiating TTS from AMI using raw echocardiographic imaging data and to compare the accuracy of our resulting model in the binary classification of TTS and AMI with the accuracy of echocardiographic evaluation by cardiologists.

Methods

Study Population

Data of patients with available transthoracic echocardiography images obtained during acute hospitalization were included from 7 cardiovascular centers in the International Takotsubo (InterTAK) Registry (Iowa, US; Jena, Germany; Regensburg, Bavaria; Salerno, Italy; Zurich, Switzerland, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia; and Winterthur, Switzerland)15 to develop the diagnostic machine learning network. The InterTAK Registry is an observational, prospective, and retrospective registry established at the University Hospital Zurich in 2011.16 Patients were included in the registry between 2011 and 2019 based on InterTAK Diagnostic criteria.10 Hospitalization data were recorded through standardized forms on admission or during revision of clinical medical records, and included patient demographic characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, electrocardiograms, and angiographic findings. Transthoracic echocardiography was performed at a median of 1 day (IQR, 0-2 days) after hospitalization in patients with TTS.

Furthermore, clinical, angiographic, and echocardiographic imaging data from patients with AMI were obtained from the Zurich Acute Coronary Syndrome Registry (Z-ACS).9 All patients with AMI fulfilled the criteria of the fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction.17 Of 114 patients with AMI included in the training cohort 110 were enrolled between January 2017 and November 2020 and 4 between October 2011 and December 2012; patients with AMI included in the test cohort were enrolled between January 2010 and November 2015.

Patients with TTS and patients with AMI were matched according to age, sex, and ST-segment elevation/non-ST-segment elevation (1 patient with AMI for each patient with TTS). Apical 2-chamber and 4-chamber echocardiographic views of 228 patients (114 with TTS and 114 with AMI) were used for designing and training the algorithm. In addition, 220 patients (110 with TTS and 110 with AMI) served as an independent test data set. Patients with TTS enrolled in the training cohort were collected from the cardiovascular centers of Iowa, Jena, Regensburg, Salerno, and Zurich; patients with TTS enrolled in the test cohort were collected from the cardiovascular centers of Adelaide, Winterthur, and Zurich. Patients with AMI from Zurich included in the training cohort were enrolled between March 2017 and May 2019; those included in the validation cohort were enrolled between April 2011 and February 2017. Data were analyzed from September 2019 to June 2021.

End-to-End Computer Vision Pipeline for Automated Echocardiography Classification

Our primary goal was to develop a deep learning–based algorithm to automatically classify TTS vs AMI based on raw cardiac ultrasound imaging data. Echocardiographic video data are particularly challenging for deep neural networks because they are very high dimensional, unstructured, and noisy. Furthermore, different types of ultrasound machines and transducers introduce disease-independent confounding factors. To perform inference based on this data type, a compressed and diagnostically informative representation would need to be found.

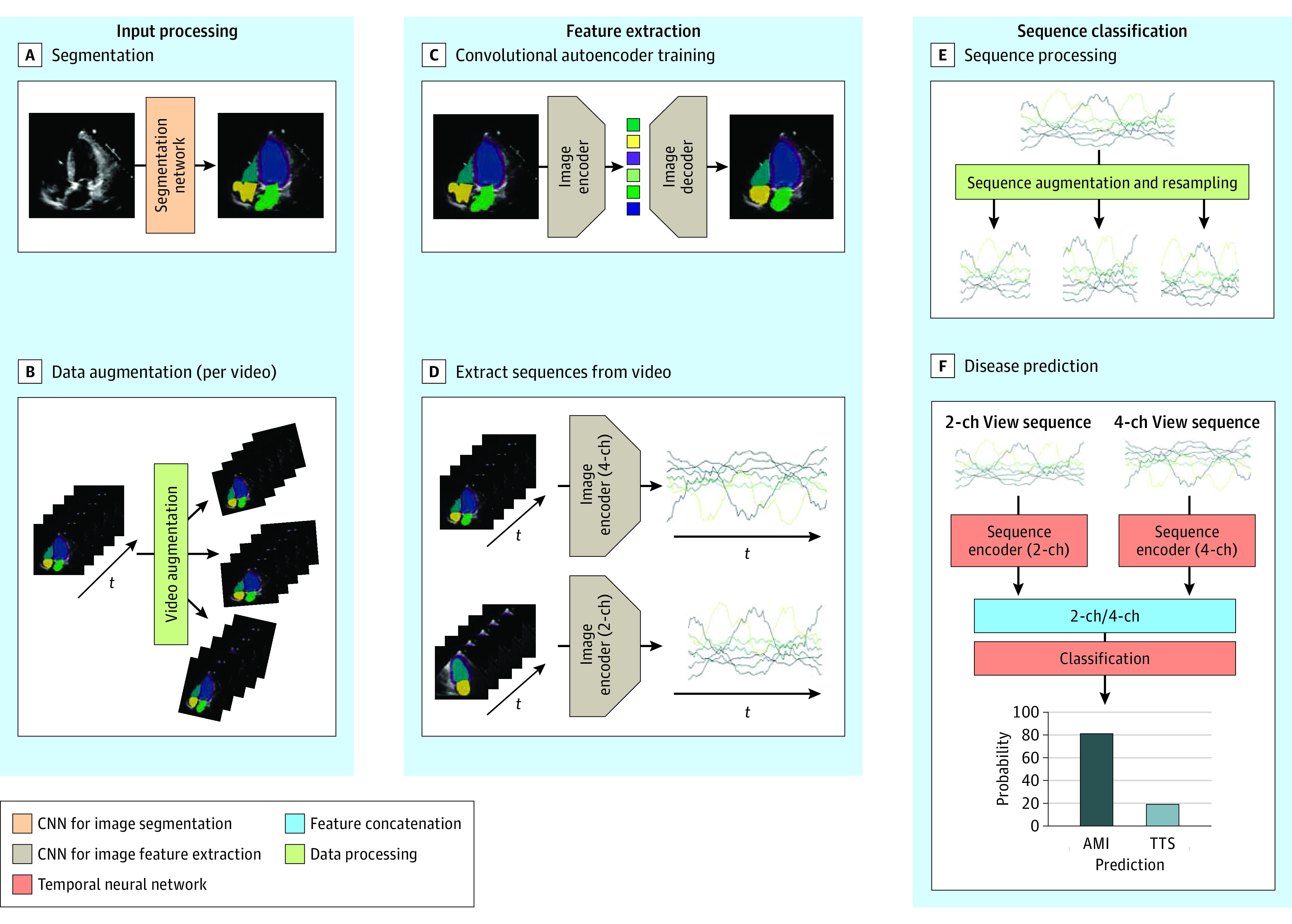

Our diagnostic machine learning pipeline consists of multiple steps, which are depicted in Figure 1. To address confounding factors introduced by the different machine types, in a first step, we used the neural network model by Zhang et al5 to segment the echocardiogram (Figure 1 A), assigning each pixel of a frame to one of the following sections: background, left ventricle blood pool, left atrium blood pool, left ventricle myocardium, right ventricle blood pool and right atrium blood pool (the latter 2 for the 4-chamber view recordings only). These semantic segmentations were calculated based on the echocardiogram images. In a second step, a convolutional autoencoder was trained to reconstruct the segmented frames. The convolutional autoencoder was then used to extract a compressed representation from each echocardiogram video. We used these extracted sequences from the segmented 2-chamber and 4-chamber view videos to train a temporal deep neural network to classify the videos according to TTS and AMI.

Figure 1. Overview of the Fully Automated Echocardiographic Video Interpretation.

The overall method consists of 3 main components: input processing, feature extraction, and sequence classification. First, each frame of echocardiogram video is semantically segmented (A) and the resulting videos are artificially augmented (B). In the next step, an autoencoder model is trained to reconstruct the segmented masks (C). The trained autoencoder is then used to extract a lower dimensional representation of each frame. A multivariate sequence originating from concatenating such representations is depicted along the time axis (D). In the final step, the sequences are artificially augmented and resampled (E), and a temporal neural network based on 1-dimensional time convolutional architecture is trained to classify the sequences according to takotsubo syndrome and acute myocardial infarction (F). CNN indicates convolutional neural network; 2-ch, 2 chamber; 4-ch, 4 chamber.

Furthermore, a framework providing insights into the prediction mechanism was developed, allowing the detection of relevant spatial regions for the disease classification.

Convolutional Autoencoder for Feature Extraction

A convolutional autoencoder, ie, a neural network consisting of an encoder and decoder part, extracts so-called latent features from each frame (Figure 1 C). The encoder part corresponds to a convolutional neural network that subsamples the image and outputs a low dimensional and compressed representation of the input. The decoder plays the role of the counterpart that reconstructs the original image from these latent feature values.

Two different autoencoders were trained for reconstructing segmented apical 2-chamber and 4-chamber views. A fraction of the videos was used for determining the convergence criteria (with the so-called early stopping). The training data set was artificially augmented by a factor of 100 by applying random rotation isotropic scaling as well as horizontal and vertical translation (Figure 1 B). The autoencoder networks were trained by minimizing a combination of mean squared error and cross-entropy loss between input segmentation and reconstruction.

Single images do not contain enough information for the classification of TTS vs AMI. The relevant information about the patient’s disease is contained in the characteristic dynamic of the different parts of the myocardium and heart chambers, ie, the typical wall movement changes in TTS (eg, apical ballooning). These regional wall movements were captured by providing the segmented masks of an echocardiogram video as input into the trained autoencoder model. The encoder extracts a compressed representation for each of the frames of a particular echocardiogram video in the data set (Figure 1 D). These resulting latent sequences were then used to differentiate between TTS and AMI.

Disease Prediction

We used a temporal convolutional neural network to predict the probabilities for TTS and AMI for each patient. We trained this neural network on the augmented training data set and extracted 10 random subsequences from each of the multivariate time series (Figure 1 E). We resampled the sequences to a fixed number of time steps before feeding them into 2 separate temporal encoder networks. The output of these networks is concatenated, and we used a fully connected neural network to predict the disease probability (Figure 1 F). The classifier was trained by minimizing the cross-entropy loss between the predicted probabilities and the ground truth labels. During inference time, we artificially augmented each echocardiogram video of the test data set by a factor of 100, extracted the sequences with the previously trained autoencoder, and then used the trained temporal neural network classifier to output a probability score for each of the augmented samples. The model then averaged the predicted probabilities over 1 patient to arrive at the final diagnosis.

Model Interpretability

We performed a sensitivity analysis of the given latent representations applying a small change to a certain latent feature value and visualizing the difference between the modified and the unchanged reconstructed segmented frame. We showed that different components of the latent feature representation focus on different parts of the myocardium. The affected areas are consistent over different videos (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Medical experts verified that these learned representations encode information about the cardiac cycle. By tracking movements of different parts of the myocardium and learning their temporal dynamics, the model is able to differentiate between TTS and AMI.

We used this insight to investigate the prediction mechanism of the model. To identify the area of the myocardium that contains the most important information for the differentiation of apical TTS vs AMI associated with occlusion of left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD-AMI), we conducted an ablation study by evaluating the performance, measured in AUC, for each latent feature sequence individually. The difference in the affected area of each latent feature value was weighted by the achieved AUC score and superimposed over the original (not segmented) echocardiographic video.

Statistical Analysis

Evaluation of the Deep Learning System

We trained 3 convolutional autoencoder models, using different random initialization as well as different training/validation split. The 3 trained autoencoder models were then subsequently used to extract sequences from each echocardiogram video. For each autoencoder model, we trained 5 temporal neural network classifiers, using different weight initializations and different training/validation splits. We report the mean prediction accuracy and SD of the resulting 15 overall classifiers by testing each of them on an independent test data set that comprised a total of 220 (110 TTS and 110 AMI) echocardiogram videos. In addition, we evaluated the viability of our algorithm to distinguish between 2 common subtypes of the diseases that might present with similar pattern of regional wall motional abnormalities, such as apical TTS and LAD-AMI.

To compare the performance of the classification pipeline with human readers, apical 2-chamber and 4-chamber views of patients from the test cohort were presented in random order on a standard reporting workstation to 4 cardiologists (reader 1, 9 years of experience in echocardiography; reader 2, 4 years of experience in echocardiography; reader 3, 3 years of experience in echocardiography; and reader 4, 5 years of experience in echocardiography). Based on these videos, the cardiologists first performed a binary differential diagnosis of TTS vs AMI and second stated their level of diagnostic confidence on a 1 to 5-point scale (1 indicating lowest confidence and 5 indicating highest confidence in their decision). To generate the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the human graders, we translated the two 5-point confidence scales into a continuous 10-point scale reaching from 0 to 9 (0 indicating highest confidence for AMI and 9 indicating highest confidence for TTS).

No statistical significance analysis was conducted. Model implementation and statistical analysis was performed using the Python programming language version 3.7.4 (Python Software Foundation). For the calculation of the ROC curves and the evaluation metrics the NumPy version 1.19.4 library and the scikit-learn version 1.0.0 library were used.

Results

Both the convolutional autoencoder model used for feature extraction and the model used for classification are completely developed and trained on the training data set. The final algorithm was then evaluated on the independent test data set as previously described. The characteristics of the patients with TTS and AMI of both training (114 patients with TTS and 114 patients with AMI) and test cohorts (110 patients with TTS and 110 patients with AMI) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients With TTS and Age-, Sex-, and ST-Segment Elevation–Matched Patients With AMI in the Training and Test Cohorts.

| Variable | No./total No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort | Test cohort | |||

| Takotsubo syndrome (n = 114) | Acute myocardial infarction (n = 114) | Takotsubo syndrome (n = 110) | Acute myocardial infarction (n = 110) | |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Female | 103 (90.4) | 103 (90.4) | 101 (91.8) | 101 (91.8) |

| Male | 11 (9.6) | 11 (9.6) | 9 (8.2) | 9 (8.2) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68.4 (12.1) | 69.1 (12.2) | 67.5 (11.4) | 68.3 (11.3) |

| Electrocardiogram on admission | ||||

| ST-segment elevation | 49/114 (43.0) | 49/114 (43.0) | 36/110 (32.7) | 36/110 (32.7) |

| Takotsubo morphologic type | ||||

| Apical | 92/114 (80.7) | NA | 61/110 (55.5) | NA |

| Midventricular | 21/114 (18.4) | NA | 39/110 (35.4) | NA |

| Basal | 1/114 (0.9) | NA | 2/110 (1.8) | NA |

| Focal | 0/114 (0.0) | NA | 8/110 (7.3) | NA |

| Culprit lesion | ||||

| Left main trunk | NA | 7/114 (6.1) | NA | 4/110 (3.6) |

| Left anterior descending artery | NA | 49/114 (43.0) | NA | 56/110 (50.9) |

| Left circumflex artery | NA | 23/114 (20.2) | NA | 17/110 (15.5) |

| Right coronary artery | NA | 35/114 (30.7) | NA | 28/110 (25.5) |

| Bypass graft | NA | 0/114 (0.0) | NA | 5/110 (4.5) |

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| Heart rate, bpm | ||||

| No. | 98 | 114 | 102 | 108 |

| Mean (SD) | 85.1 (18.0) | 80.7 (19.6) | 88.6 (20.1) | 78.9 (18.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||

| No. | 105 | 114 | 102 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 128.2 (30.8) | 131.7 (30.9) | 127.6 (27.7) | 122.9 (26.9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||

| No. | 105 | 114 | 99 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 74.7 (17.3) | 68.4 (14.9) | 75.4 (15.4) | 65.2 (14.1) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction,a % | ||||

| No. | 104 | 99 | 105 | 109 |

| Mean (SD) | 36.6 (9.2) | 47.5 (12.8) | 43.4 (11.9) | 48.6 (12.1) |

| Cardiovascular risk factor | ||||

| Hypertension | 76/112 (67.9) | 80/114 (70.2) | 65/108 (60.2) | 71/109 (65.1) |

| Diabetes | 18/112 (16.1) | 31/114 (27.2) | 26/107 (24.3) | 23/108 (21.3) |

| Smoking | 42/110 (38.2) | 55/114 (48.2) | 33/104 (31.7) | 35/109 (32.1) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 33/110 (30.0) | 45/114 (39.5) | 38/106 (35.8) | 29/109 (26.6) |

| Positive family history | 24/100 (24.0) | 17/114 (14.9) | 14/100 (14.0) | 18/109 (16.5) |

Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; TTS, takotsubo syndrome.

Data obtained during catheterization or echocardiography; if both results were available data from catheterization were used.

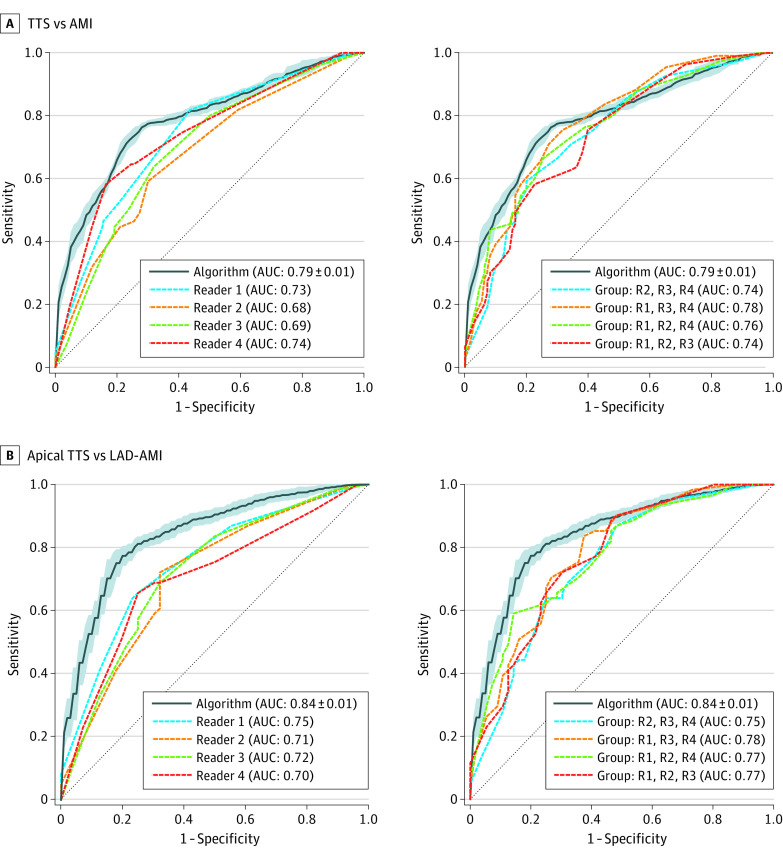

The full diagnostic pipeline was compared against 4 cardiologists by ROC curve analysis (Figure 2). Our best performing model that leverages information from both chamber views achieved a mean (SD) AUC of 0.79 (0.01) and outperformed all the 4 readers whose AUCs ranged from 0.68 to 0.74. The mean (SD) AUC values based on a model trained on 1 chamber view are 0.78 (0.01) for the apical 2-chamber view and 0.73 (0.01) for the apical 4-chamber view.

Figure 2. Performance of the Machine Learning Algorithm Compared With Cardiologists.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (TTS [takotsubo syndrome] considered as the positive class) of the algorithm plotted against the ROC of the 4 different readers. The left of each panel compares the algorithm performance against individual readers. The right of each panel compares the performance with an expert voting committee consisting of 3 of 4 readers. In panel A, the performance of the machine learning algorithm is evaluated on the whole test data set. In panel B, the algorithm is evaluated on a subset of patients with common subtypes, ie, apical TTS and LAD-AMI. AMI indicates acute myocardial infarction, AUC, area under the curve; LAD-AMI, left anterior descending AMI; R, reader.

The same model succeeded in reliably differentiating between common subtypes of TTS and AMI, namely apical TTS and LAD-AMI. The model was trained on the whole training data set and evaluated on a subset of the test data set consisting of 61 of 110 patients with apical TTS and on 56 of 110 patients with LAD-AMI. The model achieved a mean (SD) AUC score of 0.84 (0.01), thereby outperforming the 4 readers (AUCs 0.70 to 0.75) substantially. The detailed summary of the model performance and comparison to the binary diagnosis of the human readers is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Performance of the Deep Learning Model in Detecting TTS Compared With Cardiologists Evaluated on an Independent Test Data Set Consisting of 110 Patients With TTS and 110 Patients With AMI.

| Variable | True | False | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |||

| TTS a vs AMI | ||||||

| Algorithm, mean No.(SD) | ||||||

| 2-Chamber and 4-chamber | 83.1 (3.0)b | 81.5 (3.8) | 28.5 (3.8) | 26.9 (3.0)b | 75.5 (2.7)b | 74.1 (3.5) |

| 2-Chamber | 81.3 (4.1) | 79.1 (4.5) | 30.9 (4.5) | 28.7 (4.1) | 73.9 (3.7) | 71.9 (4.1) |

| 4-Chamber | 81.7 (3.3) | 74.0 (3.4) | 36.0 (3.4) | 28.3 (3.3) | 74.2 (3.0) | 67.3 (3.1) |

| Reader, No. | ||||||

| Reader 1 | 50 | 93b | 17b | 60 | 45.5 | 84.5b |

| Reader 2 | 51 | 82 | 28 | 59 | 46.4 | 74.5 |

| Reader 3 | 49 | 89 | 21 | 61 | 44.5 | 80.9 |

| Reader 4 | 71 | 83 | 27 | 39 | 64.5 | 75.5 |

| Apical TTS vs AMI due to LAD occlusion | ||||||

| Algorithm, mean No. (SD) | ||||||

| 2-Chamber and 4-chamber | 48.4 (2.3)b | 43.8 (2.1)b | 12.2 (2.1)b | 12.6 (2.3)b | 79.3 (3.8)b | 78.3 (3.8)b |

| 2-Chamber | 48.1 (2.5) | 41.3 (2.2) | 14.7 (2.2) | 12.9 (2.5) | 78.8 (4.2) | 73.7 (4.0) |

| 4-Chamber | 44.0 (3.1) | 39.2 (2.1) | 16.8 (2.1) | 17.0 (3.1) | 72.1 (5.0) | 69.9 (3.8) |

| Reader, No. | ||||||

| Reader 1 | 40 | 42 | 14 | 21 | 65.6 | 75.0 |

| Reader 2 | 37 | 38 | 18 | 24 | 60.7 | 67.9 |

| Reader 3 | 33 | 42 | 14 | 28 | 54.1 | 75.0 |

| Reader 4 | 42 | 39 | 17 | 19 | 68.9 | 69.6 |

Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; LAD, left anterior descending; TTS, takotsubo syndrome.

TTS is considered as the positive class.

The best-performing models and readers.

It is noteworthy that the performance of the human readers improved if the independent predictions from 3 of 4 readers was combined by averaging their stated confidence for TTS. Depending which of the 4 readers was omitted, the combined readers achieved AUC scores between 0.74 and 0.78 when evaluated on all the patients, and AUCs ranging from 0.75 to 0.78 when evaluated on a subset consisting of only patients with apical TTS and patients with LAD-AMI.

Considering the prediction of the algorithm in the case in which a committee of 4 cardiologists determined that the patient did not have AMI, the false negative rate of AMI could be reduced from 17 to 5 of 110 patients. Conversely, this computer-supported decision-making would lead to an increase of false negatives of TTS from 51 to 62 of 110 patients. More details about the diagnostic performance of the cardiologists compared with the machine learning algorithm can be found in eFigure 2 and eFigure 3 in the Supplement.

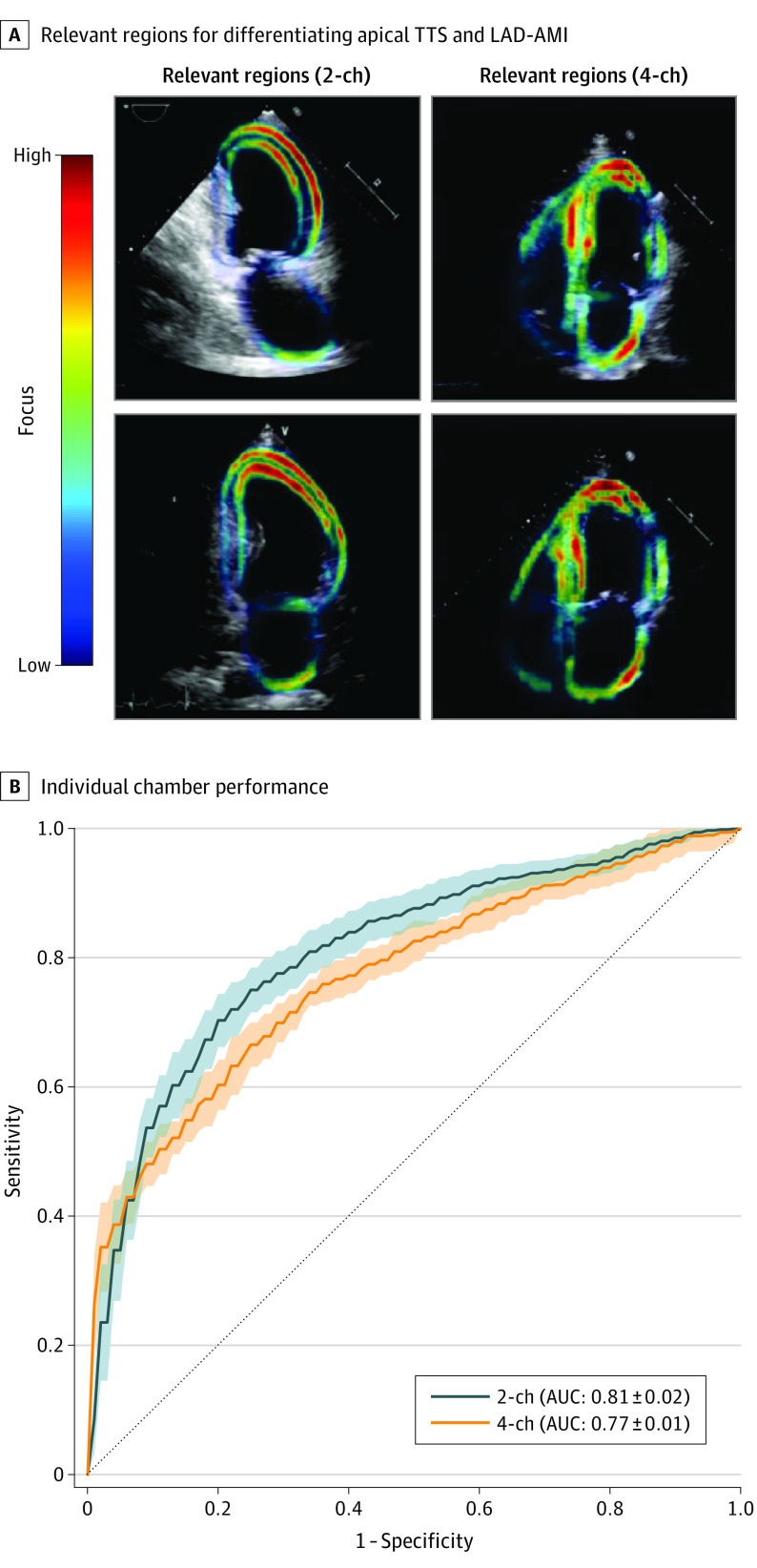

We further used the developed model interpretability framework based on the latent feature sensitivity analysis to study the differentiation between apical TTS and LAD-AMI. The latent time series that predominantly focused on apical segments of the left ventricle of the apical 2-chamber view performed best. Conducting the same analysis for the apical 4-chamber view revealed a focus on apical and midventricular inferoseptal segments of the left ventricle and a focus on the lateral wall of the left atrium. The region of the myocardium corresponding to the best performing latent feature sequences, as well as the diagnostic performance of each chamber (using all sequences) is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Interpretability Analysis (Apical TTS vs LAD-AMI).

A, The individual latent sequences extracted from a video track the movement of different parts of the myocardium. The colored parts in the ultrasound image correspond to the area on which the latent sequences that performed best in terms of area under the curve (AUC) predominantly focused. The analysis is done separately for the 2-chamber and 4-chamber view. B, The ROC curve based on the 2 different chamber views using all sequences is presented. The SD is calculated based on 5 different training and classification runs of the temporal neural network. LAD-AMI indicates left anterior descending acute myocardial infarction; TTS, takotsubo syndrome; 2-ch, 2 chamber; 4-ch, 4 chamber.

While the final algorithm performs best using all sequences and both chambers for prediction, the feature importance analysis based on the individual sequences of a particular chamber may lay first groundwork toward understanding human pathophysiology when interpreting outputs of deep learning models for challenging, human-unexplainable pathologic conditions in echocardiographic imaging.

Discussion

In this cohort study, a deep learning network was shown to perform a challenging differential diagnosis of 2 cardiovascular entities that are similar in the clinical presentation, thereby outperforming individual and a committee of 3 cardiologists. Echocardiography-based disease classification can be conducted in real-time, without the need for human preprocessing.

Previous studies3,8 have shown that machine learning can help in the echocardiography based differentiation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from physiological hypertrophy seen in athletes and constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy. Although those studies used speckle-tracking echocardiography analysis, which needs to be conducted by a trained cardiologist, our approach works solely with the raw, not preprocessed, echocardiographic data, which are readily available. This approach allows our system to classify diseases notably faster than cardiologists. Recently, Narang et al18 validated the use of a deep learning algorithm to guide novices to obtain transthoracic echocardiographic studies with satisfactory diagnostic quality. This approach might expand the application of echocardiography-based machine-learning algorithms even in the absence of highly qualified expertise. Computer-aided decision support systems that involve real-time processing of imaging data may not only reduce the time involved in cardiovascular disease diagnosis but also remove interobserver variability and problems associated with inexperienced users and biased expert judgments.19

Although certain echocardiographic features might be helpful in TTS diagnostic work-up, these are usually not sufficient for the definitive diagnosis of TTS. In terms of discriminating TTS from AMI, previous echocardiography studies revealed that despite a lower increase in troponin values, patients with TTS show more diffuse regional wall motion abnormalities than patients with anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction.20 In addition, a characteristic pattern of regional systolic myocardial dysfunction that extends beyond the distribution territory of a single coronary artery with symmetrical involvement of anterior, inferior, septal, and lateral walls (circumferential pattern), has been described for patients with TTS. A peculiar pattern of wall motion abnormalities characterized by simultaneous involvement of left and right ventricle (biventricular ballooning) has been reported in 15% to 20% of TTS cases and might help guide the differential diagnosis.20,21,22 Nevertheless, routine echocardiography has limitations regarding the differential diagnosis between TTS and AMI. Notably, anterior-inferior AMI due to occlusion of a wraparound left anterior descending coronary artery can mimic apical TTS, making the differential diagnosis particularly challenging. In a subanalysis, our model trained on the whole training data set including all TTS and AMI types and outperformed the cardiologists in the differentiation of these 2 clinical entities on the test data set.

The combination of imaging data for machine learning with clinical data, such as demographic data and biomarkers, may further improve diagnostic accuracy for TTS. The use of machine learning based on combined clinical and myocardial perfusion imaging data has been reported to have high predictive accuracy for evaluating the risk of major adverse cardiac events.23

Fully automated computer-aided decision support systems may be anticipated in the future in the field of echocardiography and may play an expanding role in precision medicine given the complexity of cardiovascular disease phenotypes.1 While deep learning algorithms are not intended to replace physician decision-making, these systems may generate fast, reproducible, and most importantly, precise echocardiographic analyses, emerging as an important tool to enable delivery of high-quality cardiac assessments in a rapid and reliable way.

Limitations

Although machine learning has been successfully applied to a variety of medical tasks in recent years, it still is subject to generalization problems and is not very resilient to confounding factors. As described in the eAppendix and eTable in the Supplement, a first version of our algorithm that acted directly on the raw video frames performed poorly because of confounding factors introduced by different ultrasound scanner models.

The study population is small compared with other machine learning classification databases used in previous medical deep learning studies.5,7,24,25 However, the relatively low prevalence of TTS, corresponding to 2% to 3% of patients presenting with suspected acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department, should be considered. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the largest study cohort in which a machine learning algorithm was tested on echocardiography video data of patients with TTS. However, having a larger population available for training might alleviate confounding factors thereby removing the need for segmentation and leading to better performance.

Future studies on a larger population are warranted to differentiate the 2 conditions using deep learning approaches considering all data available in the acute phase (demographic characteristics, symptoms, hemodynamics, biomarkers, and electrocardiogram).

While the echocardiography-based differentiation of TTS vs AMI is a challenging task for both cardiologist and algorithm, it is rare that the diagnostics options are limited to these 2 diseases. Integration of such an algorithm into clinical practice would require training and testing of the algorithm on a much broader data set, including other pathologic conditions as well as healthy patients.

Conclusions

The increasing availability of imaging technologies in everyday clinical practice suggests a growing need to efficiently process and analyze large volumes of data, such as those originating from echocardiography. In this cohort study we built the first real-time deep-learning–based system for fully automated interpretation of echocardiographic images. Our machine-learning system was trained to differentiate TTS from AMI and results showed the ability to outperform a committee of cardiologists. As more samples become available in the future, deep learning prediction might be substantially further improved, thereby gaining more insights into the dynamics of normal and diseased heart function.

eAppendix. Model Architecture and Implementation Details

eTable. Scanner Models for Each Cohort

eFigure 1. Result of the Sensitivity Analysis of the Different Latent Feature Nodes

eFigure 2. Per Patient Diagnostic Performance of AMI (Humans vs Algorithm)

eFigure 3. Per Patient Diagnostic Performance of TTS (Humans vs Algorithm)

References

- 1.Krittanawong C, Zhang H, Wang Z, Aydar M, Kitai T. Artificial intelligence in precision cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(21):2657-2664. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poplin R, Varadarajan AV, Blumer K, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular risk factors from retinal fundus photographs via deep learning. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2(3):158-164. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0195-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narula S, Shameer K, Salem Omar AM, Dudley JT, Sengupta PP. Machine-learning algorithms to automate morphological and functional assessments in 2d echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(21):2287-2295. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez-Martinez S, Duchateau N, Erdei T, et al. Machine learning analysis of left ventricular function to characterize heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(4):e007138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Gajjala S, Agrawal P, et al. Fully automated echocardiogram interpretation in clinical practice. Circulation. 2018;138(16):1623-1635. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madani A, Arnaout R, Mofrad M, Arnaout R. Fast and accurate view classification of echocardiograms using deep learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:1. doi: 10.1038/s41746-017-0013-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouyang D, He B, Ghorbani A, et al. Video-based AI for beat-to-beat assessment of cardiac function. Nature. 2020;580(7802):252-256. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2145-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sengupta PP, Huang YM, Bansal M, et al. Cognitive machine-learning algorithm for cardiac imaging: a pilot study for differentiating constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(6):e004330. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.004330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929-938. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (part I): clinical characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and pathophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(22):2032-2046. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR, et al. Natural history and expansive clinical profile of stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(4):333-341. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155(3):408-417. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato K, Lyon AR, Ghadri JR, Templin C. Takotsubo syndrome: aetiology, presentation and treatment. Heart. 2017;103(18):1461-1469. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerra F, Giannini I, Capucci A. The ECG in the differential diagnosis between takotsubo cardiomyopathy and acute coronary syndrome. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2017;15(2):137-144. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2017.1276441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takotsubo International Registry . InterTAK registry info. 2011. Accessed February 17, 2022. http://www.takotsubo-registry.com

- 16.Ghadri JR, Cammann VL, Templin C. The International Takotsubo Registry: rationale, design, objectives, and first results. Heart Fail Clin. 2016;12(4):597-603. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. ; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction . Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Glob Heart. 2018;13(4):305-338. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narang A, Bae R, Hong H, et al. Utility of a deep-learning algorithm to guide novices to acquire echocardiograms for limited diagnostic use. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(6):624-632. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darcy AM, Louie AK, Roberts LW. Machine learning and the profession of medicine. JAMA. 2016;315(6):551-552. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Citro R, Pontone G, Pace L, et al. Contemporary imaging in takotsubo syndrome. Heart Fail Clin. 2016;12(4):559-575. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurst RT, Prasad A, Askew JW III, Sengupta PP, Tajik AJ. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a unique cardiomyopathy with variable ventricular morphology. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(6):641-649. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Movahed MR. Important echocardiographic features of takotsubo or stress-induced cardiomyopathy that can aid early diagnosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(11):1200-1201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betancur J, Otaki Y, Motwani M, et al. Prognostic value of combined clinical and myocardial perfusion imaging data using machine learning. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(7):1000-1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115-118. doi: 10.1038/nature21056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghorbani A, Ouyang D, Abid A, et al. Deep learning interpretation of echocardiograms. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:10. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0216-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Model Architecture and Implementation Details

eTable. Scanner Models for Each Cohort

eFigure 1. Result of the Sensitivity Analysis of the Different Latent Feature Nodes

eFigure 2. Per Patient Diagnostic Performance of AMI (Humans vs Algorithm)

eFigure 3. Per Patient Diagnostic Performance of TTS (Humans vs Algorithm)