OBJECTIVE:

A growing proportion of critically ill patients admitted in ICUs are older adults. The need for improving care provided to older adults in critical care settings to optimize functional status and quality of life for survivors is acknowledged, but the optimal model of care remains unknown. We aimed to identify and describe reported models of care.

DATA SOURCES:

We conducted a scoping review on critically ill older adults hospitalized in the ICU. Medline (PubMed), Embase (OvidSP), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (Ebsco), and Web of Science (Clarivate) were searched from inception to May 5, 2020.

STUDY SELECTION:

We included original articles, published abstracts, review articles, editorials, and commentaries describing or discussing the implementation of geriatric-based models of care in critical care, step-down units, and trauma centers. The organization of care had to be described. Articles only discussing geriatric syndromes and specific interventions were not included.

DATA EXTRACTION:

Full texts of included studies were obtained. We collected publication and study characteristics, structures of care, human resources used, interventions done or proposed, results, and measured outcomes. Data abstraction was done by two investigators and reconciled, and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

DATA SYNTHESIS:

Our search identified 3,765 articles, and we found 19 reporting on the implementation of geriatric-based models of care in the setting of critical care. Four different models of care were identified: dedicated geriatric beds, geriatric assessment by a geriatrician, geriatric assessment without geriatrician, and a fourth model called “other approaches” including geriatric checklists, bundles of care, and incremental educational strategies. We were unable to assess the superiority of any model due to limited data.

CONCLUSIONS:

Multiple models have been reported in the literature with varying degrees of resource and labor intensity. More data are required on the impact of these models, their feasibility, and cost-effectiveness.

Keywords: critically ill, ICU, models of care, older adult

Older adults (65 yr and older), especially octogenarians (1), represent the largest growing proportion of our population while accounting for a rising share of health expenditure in high-income countries (2–5). Aging physiology, comorbidities, cognitive and physical capacities, as well as the severity of illness are different factors influencing older adults’ outcomes in critical care settings (6, 7).

Models of care for inhospital geriatric patients such as acute care for elderly (ACE) have been shown to improve patient outcomes (8). The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) has been implemented in geriatric (9), surgical (10), and oncological (11) inpatient and outpatient services (12) with improved outcomes including enhanced functional autonomy and a decrease in length of stay (LOS). However, there has been limited study of geriatric critical care, and many knowledge gaps remain. Numerous hypotheses have been formulated as to how to improve care for older adults in critical care settings, and the optimal model of care of geriatric patients in critical care remains unknown. Hence, we aimed to characterize existing and suggested models of care for critically ill older adults in medical, surgical, and trauma ICUs and assess whether it improves patient outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a scoping review on critically ill older adults hospitalized receiving intensive and subintensive care. The search strategy was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes guidelines (13). The protocol was registered on Open Science Framework (OSF) Registries (Registration DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/PY2BC). Medline (PubMed), Embase (OvidSP), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Ebsco), and Web of Science (Clarivate) were searched from inception to August 28, 2019, and updated on May 5, 2020, before article preparation. The search strategy was designed with the help of a trained systematic review methodologist (R.C.). The comprehensive search strategy, using a combination of Keywords and Medical Subject Heading terms, centered around critical care, geriatric, and models of care. It was first developed, then tested in PubMed, and subsequently adapted to Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science (Supplemental Appendix, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A950). A search was performed on the Internet to find gray literature material, and none were identified. We did the same search in Google Scholar and identified four articles. Citations were imported into Rayyan (14), a free web-based application, where duplicates were removed. Rayyan also allowed reviewers to blindly select studies to be included for review.

Study Selection

We included all original reports (observational studies, case series, randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, etc.), published abstracts, review articles (both systematic and narrative reviews), editorials, and commentaries describing or discussing common implementation structures for geriatric-based models of care for older adults in ICUs, sub-ICUs, or step-down units. We were interested in care organization and structures where principles or approaches were predetermined for older adults. Therefore, articles only discussing geriatric syndromes and specific interventions (such as medication reconciliation or delirium prevention) were not included. We included editorials and commentaries to capture all possible (theoretical and applicable) models of care.

Types of Participants

The definition of geriatric age cutoff was left to the author’s discretion. We included all types of critically ill patients including specific subgroups such as trauma, medical ICU, and surgical ICU patients

Study Eligibility

Paired investigators (T.W., M.F.F., D.B., H.T.W.) independently examined titles and abstracts for relevant articles. The full texts were extracted for studies deemed relevant by two investigators (M.F.F., D.B.). Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data Collection and Extraction

For all identified studies, we collected publication and study characteristics (first author name, publication year, journal of publication, type of study, inclusion criteria, and targeted population [age, diagnostic, and setting]); structures of care (geriatric ICU or dedicated beds, geriatric consultation, and CGA); human resources used (occupational therapy, physiotherapy, nutrition, and social worker); interventions (done or proposed); results; and measured outcomes.

Based on the described structures of care and the interventions (done or proposed), we summarized the inferred models of care for geriatric ICU patients, including the propositions made in editorials on the subjects. Each distinct model of care was summarized in a table, including proposed interventions and the clinical environment. We assessed the risk of bias (ROB) of the evidence with the ROB in nonrandomized studies of interventions assessment tool (15) because we aimed to report the measured outcomes of the selected studies.

RESULTS

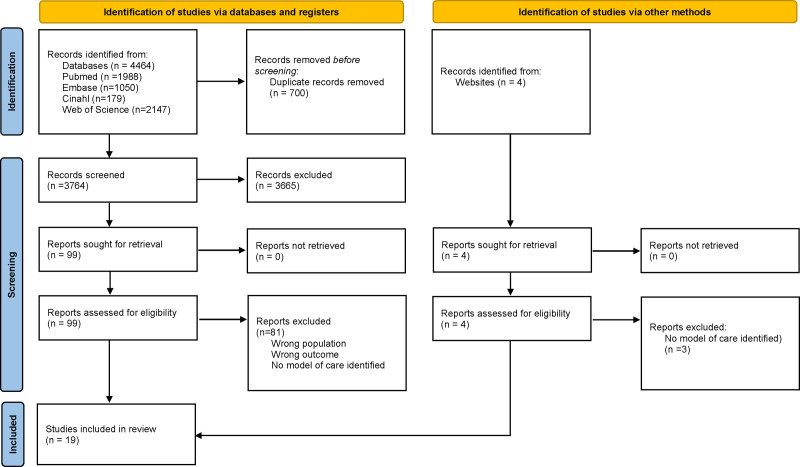

After excluding duplicates, the literature review identified 3,765 unique articles (Fig. 1). Finally, 19 articles written in four languages (English, French, Spanish, and Italian) were identified for inclusion. The most common reason for exclusion was that after full-text analysis, no geriatric models of care could be identified.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 flow diagram for systematic reviews (16).

Description of Articles

Four (21%) articles were pre-post intervention cohort studies (17–20), eight (42%) were descriptive cohort studies without a comparator group (21–28), and seven (37%) were editorials, reviews, and opinion pieces (29–35) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A969). Ten (53%) articles addressed the issue of the older adults in the setting of an ICU, five (26%) in trauma units (including ward, step-down units, and surgical ICU), and four (21%) in step-down units. Geriatric patients were identified by age cutoff in most studies, and the minimum age required varied between 60 and 80 years old. Two studies included only preselected frail or at-risk patients (18, 22).

Description of Models of Care

Four different models of care were identified (Table 1): dedicated geriatric beds (17, 20, 23, 24, 28, 33), geriatric assessment by a geriatrician (18, 19, 21, 27), geriatric assessment without geriatrician (22, 29, 34, 35), and other approaches. Other approaches included checklists, bundles of care, and incremental educational strategies (25, 26, 30–32). The four models were distinguished by the specified environment (e.g., dedicated or nondedicated beds), the medical team expertise (e.g., presence or not of a geriatrician or intensivist), the nonmedical team expertise, and the intervention types.

TABLE 1.

Models of Care

| Description of Resources and Interventions of Model of Care | |

|---|---|

| Dedicated geriatric beds | |

| Medical expertise | Material and environment |

| Critical care physician (36), internal medicine specialist (36–38), cardiologist (36–38), and geriatrician (36, 38) | Dedicated geriatric beds (23, 33, 36–38), unrestricted visits by relative (38), and adjusted lighting for sleep promotion (38) |

| Nonmedical expertise | Intervention |

| Social worker (24, 36), physiotherapist (24, 36–38), reduced patient-to-nurse ratio (24, 36–38), respiratory therapist (38), speech therapist (37), and occupational therapist (37) | Interdisciplinary team management (38), review of medication (38), delirium prevention and screening (33, 38), early mobilization (24, 38), patient and family counseling (38), adjustment of goals of care (37, 38), geriatric assessment (23, 37), social assessment (23, 37), multidimensional prognostic index (23), rehabilitation program (24), financial assistance (24), postdischarge day hospital care (24), and geriatric training for intensivist (33) |

| Geriatric assessment by geriatrician | |

| Medical expertise | Material and environment |

| Geriatrician (18, 19, 21, 27) | |

| Nonmedical expertise | Interventions |

| Physiotherapist (18, 27), nutritionist (18, 27), social worker (18), nurses (21), occupational therapist (27), and pharmacist (27) | Comprehensive geriatric assessment (18, 19, 21), early mobilization (18), prevention and screening of delirium (18), family implication in patient care (18, 21), adjustment of goals of care (18, 21), geriatric consultation (27), order for no benzodiazepine (27), and sleep optimization (27) |

| Geriatric assessment without geriatrician | |

| Medical expertise | Material and environment |

| Treating physician (22) | Patient-friendly environment including orientation cues (29) and liberal visitation by family (29) |

| Nonmedical expertise | Interventions |

| Nurse (22), social worker (22, 29), pharmacist (22, 29), nutritionist (22), elder care navigator (22), physiotherapist (22, 29), and occupational therapist (22) | Early mobilization (22), frailty assessment (22), depression screening (22), team meetings (29), application of recommendation emitted by multidisciplinary team (22), medication review (22, 34), comprehensive geriatric assessment (22, 29, 35), adjustment of goals of care (29, 34), early rehabilitation (29), skin wound prevention (29), palliative care implication (34), ADL, and instrumental ADL evaluation (35) |

| Other models of care | |

| Medical expertise | Material and environment |

| Intensivist (31) | Timely noise and light reduction (30) and adjusted visiting hours (30) |

| Nonmedical expertise | Interventions |

| Physiotherapist (25), respiratory therapist (25), nutritionist (25), pharmacist (31), and nurse (31) | Protocolized anticoagulation reversal (25), protocolized multimodel pain management (25), delirium screening and prevention (25, 30, 31, 39), early mobilization (25, 31, 39), adjustment of goals of care (25, 32), family meetings and education (25, 30, 32), skin wound prevention (25), early nutrition (25, 39), medication review (30–32, 39), Assess, Prevent, and Manage Pain (A), Both Spontaneous Awakening, Trials (B), Choice of analgesia and sedation (C), Delirium: Assess, Prevent, and Mange (D), Early mobility and Exercise (D), and Family engagement and empowerment (F) bundle (31, 39), geriatric education for nurses (30), avoidance of sensory deprivation (e.g., hearing aids) (30), functional and cognitive assessment to identify high-risk older adults (31), assess unnecessary medical tests and procedures (31), intensivists-led multidisciplinary team (32), implication of palliative care (32), patient education (32), and development of geriatric medical expertise in intensivists (32) |

ADL = activity of daily living.

Dedicated Geriatric Beds

Dedicated geriatric beds were described in two pre-post intervention cohort studies (17, 20) and three descriptive cohort studies without comparator (23, 24, 28). The five studies were in step-down units. The population represented was older adults admitted from the emergency department, other wards in the hospital, or from the ICU. The number of dedicated beds ranged from two to six (17, 20). Only two studies described the size of their unit (two to four dedicated beds in a 24-bed step-down unit [28] and four beds in a 38-bed step-down unit [23]). The editorial article referred to the model of dedicated geriatric beds as the ideal setting (33). In these studies, the mean age of the cohorts varied between 77 and 85.

Care in the dedicated geriatric beds was delivered by multidisciplinary teams consisting of critical care physicians working with geriatric specialists (geriatrician or internal medicine specialist) and other human resources including physiotherapists, social workers, occupational therapists, speech therapists, pharmacists, as well as nursing staff with a patient ratio of 1:3 to 1:6. Interventions proposed consisted of specific geriatric-driven interventions including early mobilization, direct patient and family counseling, early discharge planning including rehabilitation planning, as well as social rehabilitation (Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A950). Other interventions included medication review adapted to the older adults, adaptation of lighting to prevent falls without creating sleep disturbances, as well as unrestricted visits by relatives.

Mortality outcomes were reported in three studies (17, 20, 23). In the descriptive cohort study of a step-down unit, admitting older adults from the emergency department and ICU, the overall mortality was 22% (23). In the two pre-post intervention studies, only one showed significant difference in inhospital mortality (ACE [19.2%] vs step-down unit [12.5%]; p < 0.05) (20). LOS was reported in two studies (20, 23). There were no differences in the pre-post intervention study (ACE [7.7 ± 5.2 d] vs step-down unit [6.0 ± 4.9 d], nonsignificant for the same step-down unit older adults samples (20)). Functional outcomes were reported in one descriptive study of medical ICU survivors: 66.7% returned to their premorbid activity of daily living (24). We evaluated ROB for the two pre-post intervention studies, on step-down unit and in an intermediate care unit in a geriatric department, and they were scored serious and moderate (17, 20).

Geriatric Assessment by a Geriatrician

Geriatric assessment, through geriatric consultation or coordinated by a multidisciplinary team including a geriatrician, was described in two pre-post intervention retrospective cohort studies (18, 19), two descriptive cohort studies without comparator (21, 27), and one review (29). The population represented were older adults admitted in general ICU (21) trauma surgical ICUs and trauma step-down units (18, 27) or surgical critical care (19), and standard ICU (29). The timing of the geriatrician or the multidisciplinary team assessment, when specified, varied between 24 (19, 29), 36 (21), and 72 hours of admission (18) and occurred on weekdays. The criteria for the geriatric assessment request were based on age ranging from 60 to 80 years old (19, 21, 27) with one study using a frailty score (18). Age in the cohorts varied between 65 and older, and 80 and older.

This model of care puts the geriatrician as the main expert, either working alone (19, 21), or with a multidisciplinary team that includes a nutritionist, physical and occupational therapists, and pharmacist (18, 27). Interventions included assessment of polypharmacy, pain, cognition, nutritional status, and social circumstances. When the geriatrician worked alone, aspects of the geriatric assessment (premorbid functional data and presence of premorbid cognitive and depressive issues) were evaluated ahead of time by the patient’s ICU nurse (21). The geriatric consultation also included the use of different scales and screening tools to cover all the usual domains of a CGA (19).

Mortality was reported in two studies including trauma surgical ICUs and trauma step-down units (18) and surgical critical care (19): 30-day mortality (6.81% vs 11.63%; p = 0.10 [19]) and inhospital mortality (5.24% vs 9.30%; p = 0.12 [19]; 4.1% vs 7.2%; p = 0.28 [18]) did not differ between geriatric assessment and standard of care. LOS was reported in two retrospective studies. The represented population were from trauma acute care, and surgical critical care (19), and trauma step-down, ICU, and wards (27). Their statistical differences were either unknown or nonsignificant (8.08 vs 7.3 d; p value unavailable [27]; 6.41 vs 5.95 d; p = 0.90 [19]). One pre-post intervention study in trauma surgical ICUs and step-down units reported the prevalence of delirium, showing a beneficial effect of geriatric assessment (21.6% vs 12.5%; p = 0.05) (18). ROB was evaluated for two pre-post intervention studies (18, 19), and they were moderate or inconclusive.

Geriatric Assessment Without Geriatrician

A geriatric assessment model without the explicit use of a geriatrician includes one retrospective cohort study without a comparator group, one clinical review, and one editorial (22, 34, 35). In the descriptive study (22), CGA was performed by allied health personnel in trauma patients admitted in surgical ICU and trauma ward and screened positive for frailty (65 yr and above + one criteria or more at the Identification of Seniors at Risk tool) (36). A review and an editorial article discussed the geriatric assessment for patients in the setting of critical care (34, 35). In those two last articles, the idea of implementing the culture of CGA in ICU without a geriatrician was put forward. The age of the cohort and groups discussed was 65 and above.

A model of care of geriatric assessment without geriatrician uses a multidomain approach as central to the management of older adults in the critical care setting. As conceptualized, this model requires one or many allied health personnel (social worker, dietician, physical therapist, occupational therapist, nurses, and pharmacist), a team coordinator, regular team meetings (22), the use of standardized tools, and indexes covering all the domains of a CGA. The criteria for geriatric assessment were based on age (65 yr and older [22, 34, 35]) and risk of adverse outcomes (22, 37).

For this third model of care, no measured outcomes were reported, except the feasibility of a CGA, in trauma ward and ICUs patients, by a trauma team without a geriatric service (22). The authors concluded the model as being feasible.

Other Approaches (Checklists, Bundles of Care, and Incremental Educational Strategies)

Different approaches to geriatric patients in a critical care setting other than those described above were also found in two descriptive cohort studies without a comparator group (25, 26) and three editorial or reviews (30–32). These approaches can be subclassified as checklists and bundles, and incremental education strategies.

Checklists and Bundles

Two descriptive cohort studies without a comparator group described the impact of implementing protocols in a medical ICU (26) older adult population, and trauma and surgical ICU (25) older adult population. Aspects of these protocols included anticoagulation reversal, rib fracture management, and avoidance of benzodiazepines. Nonadherence to geriatric-focused practices in patients was assessed, including orders to withhold food and fluids (nothing by mouth), and the use of restraints. The cohort mean age was 75 and 81. In a review and in an expert opinion piece, the identification of high-risk older adults in standard ICUs were recommended through pragmatic functional and cognitive assessments. The modifiable risks factor (delirium and immobility) for disability, and the delivery of recommended interventions to improve outcomes, such as the Assess, Prevent, and Manage Pain (A), Both Spontaneous Awakening, Trials (B), Choice of analgesia and sedation (C), Delirium: Assess, Prevent, and Mange (D), Early mobility and Exercise (D), and Family engagement and empowerment (F) (ABCDEF) bundle, were described (31, 32).

Incremental Education Strategy

In the incremental education strategy, an editorial described the implementation of the Nurses Improving Care of Health System Elders (NICHE) program with critical care nurses in standard ICU (30). It defined, using delirium as a practical example, the assessment framework and multilevel interventions model to implement best geriatric centered care. In an editorial, a model of geriatric critical care medicine with stepwise innovations including the use of geriatric training resources by ICU providers, local expertise by geriatric champions, aging-friendly modification in ICU environment, and integration of geriatric curriculum into critical care medicine training was described (32). Their concept puts the critical care physician as the leader for integrating geriatric principles in the critical care setting.

DISCUSSION

In our scoping review, we found four main models of care for the management of geriatric patients in a critical care setting: 1) dedicated geriatric beds, 2) geriatric assessment by a geriatrician, 3) geriatric assessment without geriatrician, and 4) other approaches.

Common elements can be found across these models such as adapting the critical care environment to the geriatric patient, involvement of a multidisciplinary team, and regular assessment of geriatric conditions.

Different advantages and drawbacks are inherent in each of these models. The dedicated ICU geriatric bed approach is holistic with the environment and interventions geared toward the needs of older adults. However, this model has been described as being resource-intensive and challenging to implement. ICU beds are limited with ICU to ward bed ratio ranging from 3.4% to 9.0% in North America, with (38) most hospitals functioning at 70–90% of their ICU bed capacity on any given day (39, 40). The availability of step-down units is also limited, especially in small community centers. Considering these limitations, such models of care might be only applicable in high-resource tertiary or academic centers and might not be optimal for smaller community hospitals.

Geriatric assessment by a geriatrician is based on the rationale of leveraging the geriatrician’s expertise to assess and prevent geriatric syndromes such as delirium and immobility (31). This model has been successful in delirium prevention in postoperative orthopedic patients (41). Compared with the dedicated geriatric beds, it offers a simpler organizational setting with assessments performed within the ICU. An important limiting factor is the availability of a geriatrician. In many countries, geriatricians are in short supply (e.g., in Canada, there are only 300 geriatricians) (42). In addition, the expertise of geriatricians is often required in other well-established areas of expertise (oncology, preoperative evaluation, and neurocognitive assessment clinic). Given these limitations, the feasibility of routine geriatric consultants for older ICU patients remains to be proven. In addition, more data are required to inform on the impact on patient outcomes.

Model of care of geriatric assessment without a geriatrician highlights the relevance of a multidisciplinary team in the management of older adults. While frailty assessment by allied health professionals is well-established (43), few studies have looked at CGA by personnel who does not possess expertise in geriatric medicine and its impact on patient outcomes (44, 45). The absence of a geriatrician makes this model more feasible but still requires high human resources from the multidisciplinary team. The role of the medical expert in this model is assumed by the treating physician. To our knowledge, specific geriatric training is currently not part of most ICU training programs; this obstacle could be addressed in the long term by geriatric training in critical care physicians (32). Again, additional data on the impact of geriatric assessment with geriatricians are required.

The final model of care was broadly termed checklists, bundles of care, as well as incremental education strategies. The publications reporting on this offered insights into the care of geriatric patients in the critical care setting, but no structure for implementation and uptake. Nonetheless, the underlying idea behind these reports is the distillation and application of geriatric expertise in the clinical setting while not being resource-intensive. Checklists and protocols can be integrated into daily practices with an adequate education. These interventions can be delivered with existing personnel, therefore making them potentially more feasible compared with previous models. Furthermore, protocols and bundles have already shown their usefulness in the critical care setting. ABCDEF bundles are associated with a dose-response relationship and with improved patient outcomes (46).

One major drawback of protocols and checklists is that not every type of intervention can be easily and safely applied to all patients. Therefore, incremental educational strategies such as the NICHE program (30) or the gradual integration of geriatric expertise for intensivists (32) can facilitate the implementation of bundles and help address challenging areas. Overall, they enter a broad thematic of holistic care of the older adults in the critical care setting (31, 47). The argument can be made that such a holistic approach will not only benefit the geriatric population in critical care but the chronically critically ill as well. However, the impact of these types of interventions needs to be better studied. In addition, all of the models described have different resources and feasibility implications, and there are little data to choose one model over the other.

Our review has notable strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review of the literature about geriatric critical care. In addition, we are the first to describe different models of care for geriatric patients. Our review has limitations. First, while our search methodology is quite complete, we might have missed unpublished data on existing models of care. Second, we found studies with a limited level of evidence, emphasizing the need for further study in a patient population that comprises a large percentage of critically ill patients and one that is rising. Considering the heterogeneity of the included studies and the observational nature of most of them, outcome data must be interpreted with caution. Third, optimal timing and delivery of interventions require further investigations. Finally, there is no evidence comparing models of care, and optimal models of care remain undetermined, with factors such as availability of resources having a major impact on feasibility.

CONCLUSIONS

Geriatric patients comprise an increasing proportion of critical care patients and critical care units; practitioners will need to adapt to the different needs of the geriatric population to optimize patient outcomes including functional ability and quality of life. Data on the optimal model of geriatric care with the ICU are limited, and we were unable to ascertain the superiority of a particular model. Future research and high-quality studies will need to test out these models with particular attention to describing patient-centered outcomes, the feasibility of their implementation, and cost-effectiveness to inform clinicians, stakeholders, and care funders.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindemark F, Haaland ØA, Kvåle R, et al. : Costs and expected gain in lifetime health from intensive care versus general ward care of 30,712 individual patients: A distribution-weighted cost-effectiveness analysis. Crit Care 2017; 21:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Institute for Health Information. National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2019. 2019. Available at: https://www.cihi.ca/en/health-spending/2018/national-health-expenditure-trends/has-the-share-of-health-spending-on-seniors-changed. Accessed November 20, 2020

- 3.Statistics Canada. Age and sex, and type of dwelling data: Key results from the 2016 Census. The Daily. Catalogue no. 11-001-x. May 3, 2017:1–17. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/170503/dq170503a-eng.htm.

- 4.Chin-Yee N, D’Egidio G, Thavorn K, et al. : Cost analysis of the very elderly admitted to intensive care units. Crit Care 2017; 21:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas LEM, van Beusekom I, van Dijk D, et al. : Healthcare-related costs in very elderly intensive care patients. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44:1896–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somme D, Maillet JM, Gisselbrecht M, et al. : Critically ill old and the oldest-old patients in intensive care: Short- and long-term outcomes. Intensive Care Med 2003; 29:2137–2143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marik PE: Management of the critically ill geriatric patient. Crit Care Med 2006; 34:S176–S182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. : A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:1338–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Craen K, Braes T, Wellens N, et al. : The effectiveness of inpatient geriatric evaluation and management units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boddaert J, Cohen-Bittan J, Khiami F, et al. : Postoperative admission to a dedicated geriatric unit decreases mortality in elderly patients with hip fracture. PLoS One 2014; 9:e83795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao AV, Hsieh F, Feussner JR, et al. : Geriatric evaluation and management units in the care of the frail elderly cancer patient. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005; 60:798–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, et al. : Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 9:CD006211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. : PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372:n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. : Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016; 5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. : ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016; 355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. : The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellamoli C, Azzini M, Bozini C, et al. : Management of critically ill frail elderly patients: The development of an intermediate care unit in the geriatric department, Hospital of Verona. G Gerontol 2010; 58:21–30 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant EA, Tulebaev S, Castillo-Angeles M, et al. : Frailty identification and care pathway: An interdisciplinary approach to care for older trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg 2019; 228:852–859.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olufajo OA, Tulebaev S, Javedan H, et al. : Integrating geriatric consults into routine care of older trauma patients: One-year experience of a level I trauma center. J Am Coll Surg 2016; 222:1029–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranhoff AH, Rozzini R, Sabatini T, et al. : Subintensive care unit for the elderly: A new model of care for critically ill frail elderly medical patients. Intern Emerg Med 2006; 1:197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charron C, Cudennec T, Moulias S, et al. [The importance of geriatrics-intensive care collaboration]. Soins Gerontol 2013; 29–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devore S, Parli SE, Oyler DR, et al. : Comprehensive geriatric assessment for trauma: Operationalizing the trauma quality improvement program directive. J Trauma Nurs 2016; 23:337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greco A, Addante F, Scarcelli C, et al. High care unit for the elderly: One year of experience in a geriatric ward. Eur Geriatr Med 2013; 4:S95 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ip SP, Leung YF, Ip CY, et al. : Outcomes of critically ill elderly patients: Is high-dependency care for geriatric patients worthwhile? Crit Care Med 1999; 27:2351–2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karamanukyan T, Pakula A, Martin M, et al. : Application of a geriatric injury protocol demonstrates high survival rates for geriatric trauma patients with high injury acuity. Am Surg 2017; 83:1122–1126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinvani L, Kozikowski A, Patel V, et al. Non-adherence to geriatric-focused practices in older intensive care unit survivors. Am J Crit Care 2018; 27:354–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swartz K, Donnelly J, Williams P, et al. Geriatric trauma collaboration: Feasibility, sustainability and improved outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67:S11 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss L, Graf C, Herrmann F, et al. : [Intermediate geriatric care in Geneva: Experience of ten years]. Rev Med Suisse 2012; 8:2133–2137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adelman RD, Berger JT, Macina LO: Critical care for the geriatric patient. Clin Geriatr Med 1994; 10:19–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boltz M. A system-level approach to improving the care of the older critical care patient. AACN Adv Crit Care 2011; 22:142–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brummel NE, Balas MC, Morandi A, et al. : Understanding and reducing disability in older adults following critical illness. Crit Care Med 2015; 43:1265–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brummel NE, Ferrante LE: Integrating geriatric principles into critical care medicine: The time is now. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15:518–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies E. The geriatric intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Soc 2013; 1:S11 [Google Scholar]

- 34.López-Soto A, Sacanella E: [Critically-ill seniors: New challenges in the geriatric care of the future]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2008; 43:199–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.López-Soto A, Sacanella E, Pérez Castejón JM, et al. : [Elderly patient in an intensive critical unit]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2009; 44(Suppl 1):27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, et al. : Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: The ISAR screening tool. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:1229–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asomaning N, Loftus C: Identification of seniors at risk (ISAR) screening tool in the emergency department: Implementation using the plan-do-study-act model and validation results. J Emerg Nurs 2014; 40:357–364.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, et al. : Variation in critical care services across North America and Western Europe. Crit Care Med 2008; 36:2787–2793, e1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halpern NA, Pastores SM: Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-2005: An analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med 2010; 38:65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Care Provided in Canadian Intensive Care Units. 2016. Available at: https://www.cihi.ca/en/care-in-canadian-icus-data-tables. Accessed November 20, 2020

- 41.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, et al. : Reducing delirium after hip fracture: A randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49:516–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canadian Medical Association: Geriatric Medicine Profile. 2018. Available at: https://www.cma.ca/default/files/geriatric-e. Accessed November 20, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S, et al. : The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing 2009; 28:182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kocman D, Regen E, Phelps K, et al. : Can comprehensive geriatric assessment be delivered without the need for geriatricians? A formative evaluation in two perioperative surgical settings. Age Ageing 2019; 48:644–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haley MN, Casey P, Kane RY, et al. : Delirium management: Let’s get physical? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australas J Ageing 2019; 38:231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. : Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle: Results of the ICU liberation collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Crit Care Med 2019; 47:3–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michels G, Sieber CC, Marx G, et al. : [Geriatric intensive care: Consensus paper of DGIIN, DIVI, DGAI, DGGG, ÖGGG, ÖGIAIN, DGP, DGEM, DGD, DGNI, DGIM, DGKliPha and DGG]. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2019; 52:440–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]