Graphical abstract

Keywords: Long COVID, Omega-3 PUFAs, Immunity, Depression, Mood, Cognition, Inflammation, Sickness

Abbreviations: ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HPA, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; MaR, maresin; NpD, neuroprotectin D; RvD, resolvin D; RvE, resolvin E; SPMs, specialized pro-resolving mediators

Abstract

The global spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has led to the lasting pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the post-acute phase sequelae of heterogeneous negative impacts in multiple systems known as the “long COVID.” The mechanisms of neuropsychiatric complications of long COVID are multifactorial, including long-term tissue damages from direct CNS viral involvement, unresolved systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, maladaptation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and coagulation system, dysregulated immunity, the dysfunction of neurotransmitters and hypothalamus–pituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis, and the psychosocial stress imposed by societal changes in response to this pandemic. The strength of safety, well-acceptance, and accumulating scientific evidence has now afforded nutritional medicine a place in the mainstream of neuropsychiatric intervention and prophylaxis. Long chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (omega-3 or n-3 PUFAs) might have favorable effects on immunity, inflammation, oxidative stress and psychoneuroimmunity at different stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Omega-3 PUFAs, particularly EPA, have shown effects in treating mood and neurocognitive disorders by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines, altering the HPA axis, and modulating neurotransmission via lipid rafts. In addition, omega-3 PUFAs and their metabolites, including specialized pro-resolvin mediators, accelerate the process of cleansing chronic inflammation and restoring tissue homeostasis, and therefore offer a promising strategy for Long COVID. In this article, we explore in a systematic review the putative molecular mechanisms by which omega-3 PUFAs and their metabolites counteract the negative effects of long COVID on the brain, behavior, and immunity.

1. Introduction

A new coronavirus strain, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has led to a global medical crisis. Many patients recovering from the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection have persistent clinical symptoms and signs, and these long-term or delayed consequences has been becoming a popular medical entity known as “long COVID.” (Huang et al., 2021, Nalbandian et al., 2021, Rubin, 2020). Indeed, since the first appearance of the term in July 2020, it’s been shown in the PubMed for 1073 times and titled 57 articles in BMJ, 49 articles in Lancet, and 46 articles in Nature and Science (PubMed search on Feb. 28th, 2022).

Long COVID affects not only people with severe disease, but also those with mild symptoms and not even hospitalized (Duncan et al., 2020). Concerns have been raised about its impact on mental health and on patients with mental illness (Taquet et al., 2021b). A high percentage of patients diagnosed with the COVID-19 infection are prone to experience significant psychological distress recovered from the infection (Mazza et al., 2020). A range of neuropsychiatric symptoms of long COVID include anxiety, depression, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dysautonomia and non-restored sleep (Greenhalgh et al., 2020, Nath, 2020). Other post-acute neurological manifestations of COVID-19 include migraine or late-onset headache attributable to high cytokine levels, loss of taste and smell for up to 6 months, and cognitive disturbance that may present as difficulty with concentration, memory loss, decreased receptivity to language, and/or executive dysfunction, such as brain frog and dementia (Huang et al., 2021, Lopez-Leon et al., 2021, Nalbandian et al., 2021). The substantial neuropsychiatric and neurological symptoms of long COVID may be fluctuating and were consistent with prior human coronavirus epidemics (Carfi et al., 2020, Huang et al., 2021).

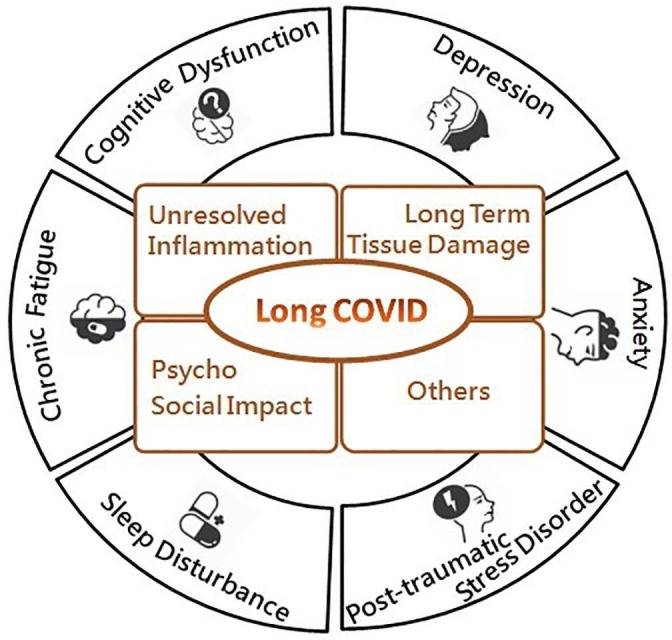

The mechanisms underlying the neuropsychiatric complications of long COVID are multifactorial, including the direct viral effects on the CNS resulting in long-term tissue damage to the brain, persistent systemic inflammation, and immune dysregulation; while psychosocial stress due to changes in health, financial status or social life, as well as the effects of oxidative stress and maladaptation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and coagulation system, may represent interactive pathways associated with psychopathological mechanisms (Mazza et al., 2020). The overview of putative pathophysiology of long COVID and associated neuropsychiatric symptoms is outlined in Fig. 1 . A holistic and multidisciplinary approach, including nutritional support, individualized and adapted physical and cardiopulmonary rehabilitation, psychological support and cognitive training, is recommended and is essential to reduce the catastrophic functional outcomes of long COVID (Greenhalgh et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

The overview of putative pathophysiology of long COVID and associated neuropsychiatric symptoms, some of which are outlined here.

Recent studies suggest that omega-3 PUFAs may interact at different stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly the viral entry and replication phases where persistent viral infection may be responsible for the sustained inflammatory state of long COVID (Carmo et al., 2020, Kandetu et al., 2020, Vibholm et al., 2021, Wang et al., 2020b, Gaebler et al., 2021, Hirotsu et al., 2021, Li et al., 2020, Park et al., 2021, Wu et al., 2020). There is growing evidence for the beneficial effects of omega-3 PUFAs and their metabolites, namely specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), including amelioration of uncontrolled inflammatory responses, reduction of oxidative stress and mitigation of coagulopathy (Calder et al., 2020). Therefore, the nutritional status of omega-3 PUFAs is particularly important for the overall immune response, tissue inflammation and repair, which may be beneficial for the condition of long COVID (Calder et al., 2020, Messina et al., 2020).

The demonstrated efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs, particularly EPA, in treating mood disorders is mainly due to their ability to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines, alter the hypothalamus–pituitaryadrenal (HPA axis), and regulate neurotransmission via lipid rafts (Chang et al., 2020). In this article, we delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying the resistance of omega-3 PUFAs to long COVID from data obtained from animal studies, human clinical trials, and epidemiological studies. These data postulate an important role of omega-3 PUFAs as a supplement to neuropsychiatric complications associated with long COVID (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

The association of potential mechanism of Long COVID and OMEGA-3 PUFAs.

| Long COVID | Potential involved mechanism | Reference | Potential effect of OMEGA-3 PUFAs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain damage | Neurotropism and replication capacity in neuronal cultures, brain organoids | (Ackermann et al., 2020, Chu et al., 2020, Sun et al., 2020, von Weyhern et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020a) | Brain protection: Regenerative, neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects -suppressing NF-κB activation -inhibiting ROS production, heme oxygenase 1 activity -attenuating apoptosis |

(Liu et al., 2014, Lu et al., 2010, Luo et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2014) |

| Changes in brain parenchyma and vessels -altering the integrity of blood–brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers -drove inflammation in neurons, brain vasculature and supportive cells |

(Reichard et al., 2020, Romero-Sánchez et al., 2020) | Beneficial effects on neurodegenerative diseases, cerebral ischemia, neurotrauma and other brain disorders | (Chiu et al., 2008, Lin et al., 2012, Lin et al., 2010, Luo et al., 2014, Michael-Titus, 2009, Su et al., 2008, Su et al., 2014, Su et al., 2018, Zhang et al., 2011) | |

| Cognitive, psychiatric and dysautonomic impairment -hypometabolism in various brain areas such as the right temporal lobe, connected limbic and paralimbic regions including the amygdala and the hippocampus, the brainstem, the cerebellum and the hypothalamus |

(Guedj et al., 2021, Yan et al., 2021) | SPMs have been reported to significantly improve behavioral, neurological and histological outcomes -modulating inflammatory, anti-oxidative, neurotrophic, and anti-apoptotic |

(Belayev et al., 2011, Blondeau et al., 2009, Horrocks and Farooqui, 2004, Lu et al., 2010, Rao et al., 2007, Shi et al., 2016) | |

| Inflammation/Neuroinflammation | Multisystem inflammatory syndrome | (Amato et al., 2021, Belot et al., 2020, Morris et al., 2020) | Activation of PPARγ Inhibition of leukocyte chemotaxis Deactivation of NF-κB Reduction of adhesion molecule expression and leukocyte-endothelial adhesive Destabilizing membrane lipids rafts |

(Calder, 2012, Calder, 2013, Rogero and Calder, 2018) |

| Interference immune cell transmigration, blood–brain barrier permeability, and the expression of radicals and other pro-oxidative molecules, and disrupts the mechanisms of neurotransmission | (Amato et al., 2021, Belot et al., 2020, Morris et al., 2020) | EPA and DHA contribute to the synthesis of SPMs -inflammatory resolution process -limiting the level and duration of critical inflammatory phases -supporting tissue regeneration -restoring tissue homeostasis |

(Rius et al., 2012, Serhan et al., 2004, Serhan et al., 2008) | |

| Limiting the migration of neutrophils and monocytes across the epithelial cells, cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) and chemokines production in damaged tissues and promoting clearance or PMN, leukocytes, apoptotic cells | (Rius et al., 2012, Serhan et al., 2004, Serhan et al., 2008) | |||

| Pschychoneuroimmunity | Neurophysiological impacts of long-term CNS damage from -viral involvement -unresolved neuroinflammation -post-infectious autoimmunity through molecular mimicry between COVID-19 epitopes and host molecules such as human myelin, and impairment of the glymphatic system, endocrine system and mitochondrial function |

(Llach and Vieta, 2021) | Maintain and protect brain function by interacting with phospholipid metabolism and thereby modulating signal transduction | (Chang et al., 2019, Guu et al., 2019, Su et al., 2008, Su et al., 2018) |

| Anxiety, mood disorders, and suicidal thoughts (Frank et al., 2020, Nalleballe et al., 2020)Depression (Yuan et al., 2020)Poor sleep and mood disorders (Lee, 2020, Zhang et al., 2020b) |

Reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines, restoring the HPA axis, altering the gut-brain axis, modulating neurotransmission through lipid rafts, and possibly enhancing immunity | (Chang and Su, 2010, Wang et al., 2021) | ||

| Dysfunction of glymphatic system | Damage to olfactory sensory neurons, causing an increased resistance to CSF outflow through the cribriform plate, and further leading to congestion of the glymphatic-lymphatic system with subsequent toxic build-up within the CNS | (Wostyn, 2021) | Prevent vascular dementia via salutary effects on lipids, inflammation, thrombosis and vascular function | (Robinson et al., 2010) |

| Beneficial effects on neuronal functioning, inflammation, oxidation and cell death, as well as on the development of the characteristic pathology of Alzheimer’s disease | (Wostyn, 2021) | |||

| Decrease Aβ production and aggregation in the brain, and act on the AQP4-mediated glymphatic pathway to promote interstitial Aβ clearance | (Ren et al., 2017) | |||

| Oxidative stress | Severe oxidative stress and the perpetuation of cytokine storms and blood clotting mechanisms, which will exacerbate hypoxia and aggravate tissue damage | (Khomich et al., 2018, Reshi et al., 2014) | Up-regulate anti-oxidant enzymes (e.g. SOD)Down-regulate pro-oxidant enzymes (e.g. NOS) Directly scavenge free radicals |

(Anderson et al., 2014) |

| ME/CFS, the symptoms of long COVID may also be due to redox imbalance, which in turn is associated with inflammation, a defective energy metabolism, and a hypometabolic state | (Paul et al., 2021) | |||

| Imbalance of RAAS system | Induces a downregulation of ACE2, from which follow the reduced ACE2 levels that are associated with decreased formation of Ang-(1–7) and the loss of its vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory and cardiovascular protective effects | (Yan et al., 2020). | Improve the formation of beneficial prostaglandin, but also inhibit ACE activity, reduce angiotensin II formation, activate eNOS generation, suppress TGF-β expression and enhance the parasympathetic nervous system | (Borghi and Cicero, 2006, Darwesh et al., 2021) |

| Directly linked to the viral S protein/ACE2 axis, the downregulation of ACE2, and the damage caused by the immune response | (Cooper et al., 2021) | |||

| Disordered Coagulopathy | The consumption of coagulation factors, as marked by thrombocytopenia -extension of prothrombin time-prominent elevation of D-dimer and other fibrinogen degradation products (FDPs) |

(Tang et al., 2020) | Antithrombotic effects against platelet activating factors and other prothrombotic pathways, including thrombin, collagen, and adenosine diphosphate | (Lordan et al., 2020) |

| Some of the most resistant amyloid deposits to fibrinolysis are present in large amounts in plasma samples from long COVID and are not readily lysed even by the two-step trypsin method | (Pretorius et al., 2021) | EPA and DHA contribute significantly to the regulation of platelet function in hemostasis and thrombosis due to their ability to act on platelet membranes via COX-1 and 12-LOX to reduce platelet aggregation and TX release, and metabolize fatty acids in platelets into a beneficial group of oxylipins | (Lordan et al., 2020, Park and Harris, 2002) | |

| Virus entry and replication for persistent viral infection | Lipid raft modulation may be an option to reduce ACE2-mediated virus infection where ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are mainly expressed | (Goc et al., 2021, Vivar-Sierra et al., 2021) | EPA and DHA could bind to the S protein of SARS-CoV-2, locking its inactive conformation and preventing the interaction between S protein and ACE2, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection | (Vivar-Sierra et al., 2021) |

| LA and EPA significantly interfered with binding to the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2, which implies blocking the entry of SARS-CoV-2 | (Goc et al., 2021) | |||

| The binding of omega-3 PUFAs to cell membranes would alter their key properties, which in turn would affect the amount of SARS-CoV-2 protein and its affinity for ACE2. | (Goc et al., 2021, Vivar-Sierra et al., 2021). |

Abbreviation: ACE: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme; AQP4: Aquaporin 4; CNS: central nervous system; COS: Cyclooxygenase; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; DHA: Docosahexaenoic acid; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; EPA: Eicosapentaenoic acid; FDP: fibrinogen degradation products; IL: interleukin; LA: linolenic acid; LOX: lipoxygenase; ME/CFS: myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; NF-κB: nuclear factor-kappa B; NOs: nitric oxide synthase; PGs:; PMN: polymorphonuclear; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor Gamma; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acids; ROS: reactive oxygen species, SOD: superoxide dismutase; SPMs: specialized pro-resolving mediators; TMPRSS2: Transmembrane protease, serine-2; TX: thromboxane; TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor.

2. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of psychiatric symptoms of long COVID

The presence of a range of post-acute psychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 are highlighted in many reviews and studies and the most frequently disclosed are depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD (Huang et al., 2021, Lopez-Leon et al., 2021, Mazza et al., 2020, Nalbandian et al., 2021, Taquet et al., 2021a). Fluctuating cognitive impairments known as brain fog, have also been noted, which may manifest as difficulties in concentration, memory, receptive language, and/or executive functioning (Heneka et al., 2020, Kaseda and Levine, 2020, Ritchie et al., 2020). Notably, the range of patients influenced by one or more neuropsychiatric symptoms of long COVID could be around 18.1%-56%, and this is comparable to prior human coronavirus epidemics (Carfi et al., 2020, Huang et al., 2021).

In a cohort study of 402 adults surviving COVID-19 (265 male, mean age 58) in Italy, after 1 month of hospital treatment, approximately 56% screened positive in at least one of the domains evaluated for psychiatric sequelae (depression, anxiety, insomnia, PTSD and obsessive–compulsive symptoms) (Mazza et al., 2020). In a post-acute cohort study of the consequences of COVID-19 in Chinese patients discharged from hospital, approximately one-quarter of patients experienced anxiety, depression, and sleep difficulties at 6-month follow-up (Huang et al., 2021). An analysis of retrospective cohort studies of 62,354 COVID-19 cases from 54 healthcare organizations in the United States showed an 18.1% incidence of first and recurrent psychiatric illness within 14 to 90 days of diagnosis (Taquet et al., 2021b). More informatively, the report also noted that the estimated overall probability of diagnosing a new psychiatric illness within 90 days of COVID-19 diagnosis was 5.8% in a subset of 44,759 patients with no previously known psychosis. In another retrospective cohort study of 236,379 COVID-19 survivors using electronic health records, 1 in 3 patients experienced neuropsychiatric disorders within 6 months of COVID-19 diagnosis, which was 44% more common than among influenza survivors (Taquet et al., 2021a).

It is apparent that in the foreseeable future, the demand for health care for people with neuropsychiatric sequelae of long COVID will continue to increase, and further interdisciplinary integration is needed to improve the physical and mental health of COVID-19 survivors.

3. Inflammation/ neuroinflammation in long COVID and the role of Omega-3 PUFAs

Evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 can be persistently detected in the body beyond the acute infection stage (Carmo et al., 2020, Kandetu et al., 2020, Vibholm et al., 2021, Wang et al., 2020b); (Gaebler et al., 2021, Hirotsu et al., 2021, Li et al., 2020, Park et al., 2021, Wu et al., 2020). Furthermore, multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS) occurring 2–6 weeks after SARS- CoV-2 infection play a role in persistent effects of COVID-19 (Amato et al., 2021, Belot et al., 2020, Morris et al., 2020). The neuroinflammatory status compromises the immune cell transmigration, blood–brain barrier permeability, and the expression of radicals and other pro-oxidative molecules, and disrupts the mechanisms of neurotransmission (Amato et al., 2021, Belot et al., 2020, Morris et al., 2020). Ultimately, the persistence of the virus which leads to long-lasting inflammation/neuroinflammation may provide a theoretical basis for the psychiatric long lasting manifestations (Mazza et al., 2020).

It is worth noting that mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory actions of omega-3 PUFAs involve activation of anti-inflammatory transcription factors, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor Gamma (PPARγ), inhibition of leukocyte chemotaxis, deactivation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), reduction of adhesion molecule expression and leukocyte-endothelial adhesive interactions, and destabilizing membrane lipids rafts (Calder, 2012, Calder, 2013, Rogero and Calder, 2018). Furthermore, when oxidized by enzymes, EPA and DHA contribute to the synthesis of SPMs, which play an effective role in the inflammatory resolution process, limiting the level and duration of critical inflammatory phases, supporting tissue regeneration, and restoring tissue homeostasis (Rius et al., 2012, Serhan et al., 2004, Serhan et al., 2008). E-series resolvins from EPA, D-series resolvins, maresins and protectins from DHA have significant anti-inflammatory properties by limiting the migration of neutrophils and monocytes across the epithelial cells, cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) and chemokines production in damaged tissues and promoting clearance or polymorphonuclear (PMN), leukocytes, apoptotic cells and debris from the site of inflammation (Rius et al., 2012, Serhan et al., 2004, Serhan et al., 2008). However, further studies on omega-3 PUFAs for the treatment of long COVID and their anti-inflammatory effects on long-lasting inflammation with immunologic aberrations in patients with long COVID still need to be supported by well-conducted and properly controlled clinical trials.

4. The pschychoneuroimmunity models against long covid with Omega-3

The psychoneuroimmunity model of long COVID comprises fear, stigma, or psychological impact of several illness, and compounds the effects of psychological stressors imposed by societal changes. In addition, the government's city lockdown measures, not only halted general social interactions, but also had a negative impact on mental health, leading to decreased immunity and slower recovery. It also complicates the neurophysiological impacts of long-term CNS damage from viral involvement, unresolved neuroinflammation, post-infectious autoimmunity through molecular mimicry between COVID-19 epitopes and host molecules such as human myelin, and impairment of the glymphatic system, endocrine system and mitochondrial function (Llach and Vieta, 2021).

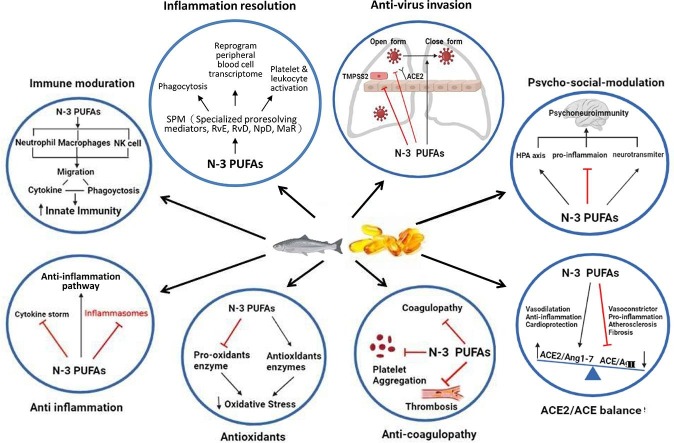

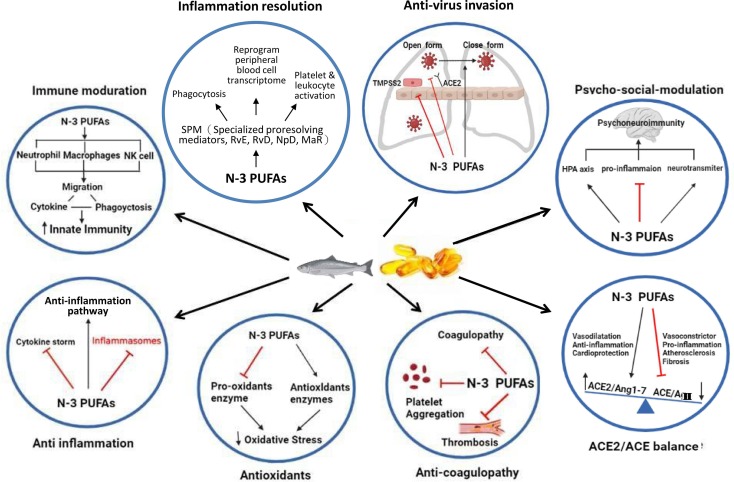

In addition to the overwhelming studies on the positive effects of supplementation with omega-3 PUFAs, there have been several inverse studies on the deficiency outcomes with omega-3 PUFAs. These studies did find a significant inverse relationship between deficiency of omega-3 PUFAs and the manifestation of several neuropsychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD) (Lin et al., 2010), perinatal depression (Freeman, 2006), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Chang et al., 2018), and dementia (Lin et al., 2012). In response to these neuropsychiatric manifestations of deficiency in omega-3 PUFAs, other interventional studies of omega-3 PUFA supplementation have found that they have the potential to maintain and protect brain function by interacting with phospholipid metabolism and thereby modulating signal transduction; and improve clinical outcomes in MDD (Guu et al., 2019), perinatal depression (Su et al., 2008), ADHD (Chang et al., 2019), and anxiety disorders (Su et al., 2018). As we know, the HPA axis is also affected by COVID-19, which is usually activated by stress and can further influence the emotional state of an individual. Omega-3 PUFAs, particularly EPA, have been shown to treat mood disorders by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines, restoring the HPA axis, altering the gut-brain axis, modulating neurotransmission through lipid rafts, and possibly enhancing immunity to the physical and mental effects of COVID-19 through these potential mechanisms (Chang and Su, 2010, Wang et al., 2021). It is worth mentioning that the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research (ISNPR) has also published practice guidelines for omega-3 PUFAs in the treatment of MDD (Guu et al., 2019). It appears that, omega-3 PUFAs could also be used as a potential nutrient in patients with neuropsychiatric complications of long COVID and further studies are needed to confirm the important role of omega-3 PUFAs as a supplement to neuropsychiatric complications associated with long COVID. Fig. 2 outlines the potential molecular mechanisms of omega-3 PUFAs on long COVID.

Fig. 2.

The summary of potential molecular mechanisms of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on long COVID. ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme; HPA: hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal; MaR: maresin; n-3 PUFAs: Long chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids; NpD: neuroprotectin D; RvD: resolvin D; RvE: resolvin E.

5. Restoration of the clearance function of the glymphatic system in long COVID

Interestingly, post-COVID-19 fatigue has been compared with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), with many overlaps between the two (Stefano et al., 2021, Wang et al., 2020a). The symptoms mostly comprise of a feeling of extreme fatigue, non-restorative sleep, variable nonspecific myalgia and headache and having a trouble in thinking/remembering often described as “brain fog”. This syndrome may result from damage to olfactory sensory neurons, causing an increased resistance to CSF outflow through the cribriform plate, and further leading to congestion of the glymphatic-lymphatic system with subsequent toxic build-up within the CNS (Wostyn, 2021). Strategies that can restore or improve the clearance function may hold great promise in treating the symptoms of brain fog or post-COVID-19 fatigue including insomnia and brain fog.

Omega-3 PUFAs have shown a wide variety of beneficial effects on neuronal functioning, inflammation, oxidation and cell death, as well as on the development of the characteristic pathology of Alzheimer’s disease (Wostyn, 2021). Notably, omega-3 PUFAs not only decrease Aβ production and aggregation in the brain but also act on the AQP4-mediated glymphatic pathway to promote interstitial Aβ clearance (Ren et al., 2017). By improving glymphatic transport and decreasing toxin aggregation, omega-3 PUFAs has therefore been suggested to deal with neuropsychiatric complications of long COVID. Further studies are needed to confirm the important role of omega-3 PUFAs as a modulation of glymphatic system associated with long COVID.

6. Possession of the anti-oxidant properties for long COVID

It is known that the hypoxia caused by SARS-CoV-2 will also lead to the generation of superoxide, H2O2 and other reactive oxygen species (ROS). As in ME/CFS, the symptoms of long COVID may also be due to redox imbalance, which in turn is associated with inflammation, a defective energy metabolism, and a hypometabolic state (Paul et al., 2021). Omega-3 PUFAs have been found to exhibit anti-oxidant properties due to their ability to up-regulate anti-oxidant enzymes (e.g. superoxide dismutase) and down-regulate pro-oxidant enzymes (e.g. nitric oxide synthase), and their potential to directly scavenge free radicals (Anderson et al., 2014). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that increased omega-3 PUFAs and their corresponding metabolites may provide beneficial control of free radical generation, ROS production, and oxidant stress prevention which may help the resolution of oxidative stress in long COVID.

7. Modulation of the balance of the RAAS system for long COVID

The development of long COVID is speculated to be directly linked to the viral S protein/ACE2 axis, the downregulation of ACE2, and the damage caused by the immune response (Cooper et al., 2021). Interestingly, intervention with omega-3 PUFAs not only improve the formation of beneficial PGs, but also inhibit angiotensin-converting enzyme activity, reduce angiotensin II formation, activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) generation, suppress TGF-beta expression and enhance the parasympathetic nervous system (Borghi and Cicero, 2006, Darwesh et al., 2021). The end result is ameliorated vasodilation and arterial compliance in both small and large arteries, which may in turn reduce complications. This suggests a novel role for omega-3 PUFAs in correcting the imbalance in the RAAS system that increases Ang-(1–7) production, decreases Ang II levels, and ultimately modulates inflammation caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, thus potentially serving as an adjuvant therapy to limit acute and/or long-term complications due to COVID-19 (Darwesh et al., 2021).

8. Potential coagulopathy improvement of long COVID

Clinical manifestations of coagulation dysfunction caused by SARS-CoV-2 can be the presence of extensive microvascular or macrovascular thrombosis (Tang et al., 2020). Notably, some of the most resistant amyloid deposits to fibrinolysis are present in large amounts in plasma samples from long COVID and are not readily lysed even by the two-step trypsin method (Pretorius et al., 2021). Omega-3 PUFAs exhibit potent antithrombotic effects against platelet activating factors and other prothrombotic pathways, including thrombin, collagen, and adenosine diphosphate (Lordan et al., 2020). Within this family of omega-3 PUFAs, the EPA and DHA contribute significantly to the regulation of platelet function in hemostasis and thrombosis due to their ability to act on platelet membranes via COX-1 and 12-LOX to reduce platelet aggregation and TX release, and metabolize fatty acids in platelets into a beneficial group of oxylipins (Lordan et al., 2020, Park and Harris, 2002). However, our current level of knowledge only allows us to speculate that supplementation with omega-3 PUFAs may be effective in patients with long COVID.

9. Viral entry and replication interference in persistent viral infections of long COVID

SARS-CoV-2 is known for their neurotropism, and neuronal and glial dysfunctions and death can be triggered by either direct neuronal retrograde neuro-invasive or indirect hematogenous routes (Llach and Vieta, 2021). It is postulated that persistent viral infection or new COVID-19 variants may be responsible for the long-term complications of long COVID (Paul et al., 2021). Since neurons rarely regenerate, the resulting brain dysfunction may be long-lasting, leading to neurological and neuropsychiatric sequelae that might underlie long COVID (Yong, 2021).

Studies have shown that the incorporation of omega-3 PUFAs in neutrophil membrane phospholipids enhances immune function and kills pathogens by promoting neutrophil migration, phagocytosis and production of reactive free radicals (Gutierrez et al., 2019). The up-regulation of immune cell activation in macrophages by omega-3 PUFAs is accomplished by the secretion of cytokines and chemokines, which promote phagocytosis and polarize macrophages into classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) macrophages (Eslamloo et al., 2017, Hathaway et al., 2020). Recently, a study showed that by high dietary intake or supplementation of omega-3 PUFAs, EPA and DHA could bind to the S protein of SARS-CoV-2, locking its inactive conformation and preventing the interaction between S protein and ACE2, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection (Vivar-Sierra et al., 2021). It is postulated that lipid raft modulation may be an option to reduce ACE2-mediated virus infection where ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are mainly expressed (Goc et al., 2021, Vivar-Sierra et al., 2021). Intriguingly, another study found that linolenic acid (LA) and EPA significantly interfered with binding to the SARS- CoV-2 receptor ACE2, which implies blocking the entry of SARS-CoV-2 (Goc et al., 2021). Furthermore, EPA showed higher efficacy than LA in reducing the activity of TMPRSS2 and cathepsin L protease, rather than the ACE2 receptor. It appears that the binding of omega-3 PUFAs to cell membranes would alter their key properties, which in turn would affect the amount of SARS-CoV-2 protein and its affinity for ACE2 (Goc et al., 2021, Vivar-Sierra et al., 2021). For those who cannot receive vaccines or for whom vaccination is ineffective, the useful antiviral properties of omega-3 PUFAs will be particularly important for patients with persistent viral infections, and will thus improve the condition of long COVID.

10. Future perspective

Two relatively large randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are currently underway to test the hypothesis that treatment of severe forms of COVID-19 with omega-3 PUFAs (EPA alone or EPA with DHA) is beneficial (EPA-COV-001, 2020, MRC-04-20-1120, 2020). However, clinical interventional studies investigating the role of omega-3 PUFAs in individuals with long-COVID are currently not available. Nonetheless, due to their generally favorable profiles from various standpoints (psychiatric, cardiovascular, etc.), omega-3 PUFAs can be considered a potential health supplement to help maintain physical and mental health in this unabated epidemic, both in the acute and long COVID phases. Recently, various guidelines have been proposed by public health and primary care physicians for the diagnosis and management of long COVID (Crook et al., 2021, Escardio.org, 2020, Excellence, 2020, Organization, 2021, Sisó-Almirall et al., 2021, USnews.com, 2021); Nevertheless, other relevant guidelines aimed at treating specific psychiatric problems may also be helpful in treating long COVID, such as the ISNPR practice guidelines for omega-3 PUFAs in the treatment of MDD (Guu et al., 2019).

Furthermore, there are still some questions that remain to be addressed. What is the optimal dose and duration of treatment for omega-3 PUFAs as a supplement to fight long COVID? Should the clinicians consider the baseline omega-6: omega 3 ratios in each patient before administration? What are the potential benefits and risks of high-dose omega-3 PUFAs supplementation for long COVID? What are the roles and differences of the omega-3 PUFAs family (ALA, EPA, DHA) in preventing or dealing with long COVID? Which subpopulation of patients should be selected in cases of long COVID? Which biomarkers are closely associated with the therapeutic response to omega-3 PUFAs for long COVID? These issues are extremely important and need to be addressed to provide more effective treatment options for patients with long COVID. To answer these questions, scientists and clinicians should join the global community’s effort and focus on high-quality, evidence-based research in response to the long-term neuropsychiatric sequel.

11. Conclusion

This review highlights the molecular mechanisms of omega-3 PUFAs mediated resistance against long COVID based on available evidence. In addition to preserving or repairing the brain structure and function by interacting with phospholipid metabolism and the known shift in the pattern of lipid metabolites to a more anti-inflammatory metabolite profile, omega-3 PUFAs and/or their biologically active metabolites have the potential to improve oxidative stress, and immune dysregulation; maladaptation of the RAAS and coagulation system; and psychosocial stress from changes in health, financial status, or social life. Despite these promising effects of omega-3 PUFAs, additional epidemiological, experimental, and RCTs are needed to test, validate, and translate these proposed effects in the context of long COVID. The information presented in this review has not been widely deliberated in other literature and may serve as a starting point for further exploration of omega-3 PUFAs on long COVID.

Author contributions

CPY, CMC, CCY, CMP and KPS were responsible for the study concept and design, modification of the study design, and review and interpretation of the data. CPY, CMC and KPS were responsible for drafting the manuscript. KPS made modifications to the study design and revised the manuscript. CPY, CMC, CCY and CMP contributed to the collection and analysis of data. CPY, CMC, CMP, and KPS contributed to the interpretation of the data and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work were supported by the following grants: MOST 109-2320-B-038-057-MY3, 109-2320-B-039-066, 110-2321-B-006-004, 110-2811-B-039-507, 110-2320-B-039-048-MY2, and 110-2320-B-039-047-MY3 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan; ANHRF 109-31, 109-40, 110-13, 110-26, 110-44, and 110-45 from An-Nan Hospital, China Medical University, Tainan, Taiwan; and CMU104-S-16-01, CMU103-BC-4-1, CRS-108-048, DMR-102-076, DMR-103-084, DMR-106-225, DMR-107-204, DMR-108-216, DMR-109-102, DMR-109-244, DMR-HHC-109-11, DMR-HHC-109-12, DMR-HHC-110-10, DMR-110-124, and CMU110-AWARD-02 from the China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

References

- Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M., Haverich A., Welte T., Laenger F., Vanstapel A., Werlein C., Stark H., Tzankov A., Li W.W., Li V.W., Mentzer S.J., Jonigk D. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(2):120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato M.-K., Hennessy C., Shah K., Mayer J. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in an adult. J. Emerg. Med. 2021;61(1):e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E.J., Thayne K.A., Harris M., Shaikh S.R., Darden T.M., Lark D.S., Williams J.M., Chitwood W.R., Kypson A.P., Rodriguez E. Do fish oil omega-3 fatty acids enhance antioxidant capacity and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in human atrial myocardium via PPARgamma activation? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;21:1156–1163. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belayev L., Khoutorova L., Atkins K.D., Eady T.N., Hong S., Lu Y., Obenaus A., Bazan N.G. Docosahexaenoic acid therapy of experimental ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2(1):33–41. doi: 10.1007/s12975-010-0046-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belot, A., Antona, D., Renolleau, S., Javouhey, E., Hentgen, V., Angoulvant, F., Delacourt, C., Iriart, X., Ovaert, C., Bader-Meunier, B., Kone-Paut, I., Levy-Bruhl, D., 2020. SARS-CoV-2-related paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome, an epidemiological study, France, 1 March to 17 May 2020. Euro Surveill 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blondeau N., Nguemeni C., Debruyne D.N., Piens M., Wu X., Pan H., Hu X., Gandin C., Lipsky R.H., Plumier J.-C., Marini A.M., Heurteaux C. Subchronic alpha-linolenic acid treatment enhances brain plasticity and exerts an antidepressant effect: a versatile potential therapy for stroke. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(12):2548–2559. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghi C., Cicero A.F. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Their potential role in blood pressure prevention and management. Heart Int. 2006;2:98. doi: 10.4081/hi.2006.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder P.C. Mechanisms of action of (n-3) fatty acids. J. Nutr. 2012;142:592S–599S. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.155259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder P.C. Long chain fatty acids and gene expression in inflammation and immunity. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2013;16(4):425–433. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283620616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder P., Carr A., Gombart A., Eggersdorfer M. Optimal nutritional status for a well-functioning immune system is an important factor to protect against viral infections. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1181. doi: 10.3390/nu12041181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carfi, A., Bernabei, R., Landi, F., Gemelli Against, C.-P.-A.C.S.G., 2020. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 324, 603-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carmo A., Pereira‐Vaz J., Mota V., Mendes A., Morais C., Silva A.C., Camilo E., Pinto C.S., Cunha E., Pereira J., Coucelo M., Martinho P., Correia L., Marques G., Araújo L., Rodrigues F. Clearance and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in patients with COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(10):2227–2231. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.P., Su K.P. The lipid raft hypothesis: the relation among omega-3 fatty acids, depression, and cardiovascular diseases. Taiwan J. Psychiatry. 2010;24:168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.-C., Pariante C.M., Su K.-P. Omega-3 fatty acids in the psychological and physiological resilience against COVID-19. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2020;161:102177. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2020.102177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.-C., Su K.-P., Mondelli V., Pariante C.M. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in youths with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials and biological studies. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(3):534–545. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.P., Su K.P., Mondelli V., Satyanarayanan S.K., Yang H.T., Chiang Y.J., Chen H.T., Pariante C.M. High-dose eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) improves attention and vigilance in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and low endogenous EPA levels. Transl. Psychiatry. 2019;9:303. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0633-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C.-C., Su K.-P., Cheng T.-C., Liu H.-C., Chang C.-J., Dewey M.E., Stewart R., Huang S.-Y. The effects of omega-3 fatty acids monotherapy in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a preliminary randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1538–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H., Chan J.-W., Yuen T.-T., Shuai H., Yuan S., Wang Y., Hu B., Yip C.-Y., Tsang J.-L., Huang X., Chai Y., Yang D., Hou Y., Chik K.-H., Zhang X.i., Fung A.-F., Tsoi H.-W., Cai J.-P., Chan W.-M., Ip J.D., Chu A.-H., Zhou J., Lung D.C., Kok K.-H., To K.-W., Tsang O.-Y., Chan K.-H., Yuen K.-Y. Comparative tropism, replication kinetics, and cell damage profiling of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV with implications for clinical manifestations, transmissibility, and laboratory studies of COVID-19: an observational study. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1(1):e14–e23. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S.L., Boyle E., Jefferson S.R., Heslop C.R.A., Mohan P., Mohanraj G.G.J., Sidow H.A., Tan R.C.P., Hill S.J., Woolard J. Role of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone and Kinin-Kallikrein Systems in the Cardiovascular Complications of COVID-19 and Long COVID. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(15):8255. doi: 10.3390/ijms22158255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook H., Raza S., Nowell J., Young M., Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwesh A.M., Bassiouni W., Sosnowski D.K., Seubert J.M. Can N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids be considered a potential adjuvant therapy for COVID-19-associated cardiovascular complications? Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;219:107703. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan E., Cooper K., Cowie J., Alexander L., Morris J., Preston J. A national survey of community rehabilitation service provision for people with long Covid in Scotland. F1000Res. 2020;9:1416. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.27894.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA-COV-001, 2020. EPA-FFA to Treat Hospitalised Patients With COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04335032.

- Escardio.org, 2020. ESC guidance for the diagnosis and management of CV disease during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Eslamloo K., Xue X., Hall J.R., Smith N.C., Caballero-Solares A., Parrish C.C., Taylor R.G., Rise M.L. Transcriptome profiling of antiviral immune and dietary fatty acid dependent responses of Atlantic salmon macrophage-like cells. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:706. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4099-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excellence, N.I.f.H.a.C., 2020. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 NICE guideline. [PubMed]

- Frank A., Fatke B., Frank W., Forstl H., Holzle P. Depression, dependence and prices of the COVID-19-Crisis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M.P. Omega-3 fatty acids and perinatal depression: a review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2006;75(4-5):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebler C., Wang Z., Lorenzi J.C.C., Muecksch F., Finkin S., Tokuyama M., Cho A., Jankovic M., Schaefer-Babajew D., Oliveira T.Y., Cipolla M., Viant C., Barnes C.O., Bram Y., Breton G., Hägglöf T., Mendoza P., Hurley A., Turroja M., Gordon K., Millard K.G., Ramos V., Schmidt F., Weisblum Y., Jha D., Tankelevich M., Martinez-Delgado G., Yee J., Patel R., Dizon J., Unson-O’Brien C., Shimeliovich I., Robbiani D.F., Zhao Z., Gazumyan A., Schwartz R.E., Hatziioannou T., Bjorkman P.J., Mehandru S., Bieniasz P.D., Caskey M., Nussenzweig M.C. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;591(7851):639–644. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03207-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goc A., Niedzwiecki A., Rath M. Polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids inhibit ACE2-controlled SARS-CoV-2 binding and cellular entry. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:5207. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84850-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Knight M., A'Court C., Buxton M., Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedj E., Campion J.Y., Dudouet P., Kaphan E., Bregeon F., Tissot-Dupont H., Guis S., Barthelemy F., Habert P., Ceccaldi M., Million M., Raoult D., Cammilleri S., Eldin C. (18)F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2021;48(9):2823–2833. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez S., Svahn S.L., Johansson M.E. Effects of Omega-3 fatty acids on immune cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:5028. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guu T.-W., Mischoulon D., Sarris J., Hibbeln J., McNamara R., Hamazaki K., Freeman M., Maes M., Matsuoka Y., Belmaker R.H., Jacka F., Pariante C., Berk M., Marx W., Su K.-P. International society for nutritional psychiatry research practice guidelines for omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychother. Psychosom. 2019;88(5):263–273. doi: 10.1159/000502652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway D., Pandav K., Patel M., Riva-Moscoso A., Singh B.M., Patel A., Min Z.C., Singh-Makkar S., Sana M.K., Sanchez-Dopazo R., Desir R., Fahem M.M.M., Manella S., Rodriguez I., Alvarez A., Abreu R. Omega 3 fatty acids and COVID-19: a comprehensive review. Infect Chemother. 2020;52(4):478. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.4.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka M.T., Golenbock D., Latz E., Morgan D., Brown R. Immediate and long-term consequences of COVID-19 infections for the development of neurological disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:69. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00640-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsu Y., Maejima M., Shibusawa M., Amemiya K., Nagakubo Y., Hosaka K., Sueki H., Hayakawa M., Mochizuki H., Tsutsui T., Kakizaki Y., Miyashita Y., Omata M. Analysis of a persistent viral shedding patient infected with SARS-CoV-2 by RT-qPCR, FilmArray Respiratory Panel v2.1, and antigen detection. J Infect Chemother. 2021;27(2):406–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks L.A., Farooqui A.A. Docosahexaenoic acid in the diet: its importance in maintenance and restoration of neural membrane function. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2004;70(4):361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Gu X., Kang L., Guo L.i., Liu M., Zhou X., Luo J., Huang Z., Tu S., Zhao Y., Chen L.i., Xu D., Li Y., Li C., Peng L.u., Li Y., Xie W., Cui D., Shang L., Fan G., Xu J., Wang G., Wang Y., Zhong J., Wang C., Wang J., Zhang D., Cao B. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandetu T.B., Dziuban E.J., Sikuvi K., Beard R.S., Nghihepa R., van Rooyen G., Shiningavamwe A., Katjitae I. Persistence of Positive RT-PCR Results for Over 70 Days in Two Travelers with COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaseda E.T., Levine A.J. Post-traumatic stress disorder: a differential diagnostic consideration for COVID-19 survivors. Clin Neuropsychol. 2020;34(7-8):1498–1514. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2020.1811894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khomich O., Kochetkov S., Bartosch B., Ivanov A. Redox biology of respiratory viral infections. Viruses. 2018;10(8):392. doi: 10.3390/v10080392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.A. How much “Thinking” about COVID-19 is clinically dysfunctional? Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Zheng X.-S., Shen X.-R., Si H.-R., Wang X.i., Wang Q.i., Li B., Zhang W., Zhu Y., Jiang R.-D., Zhao K., Wang H., Shi Z.-L., Zhang H.-L., Du R.-H., Zhou P. Prolonged shedding of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in patients with COVID-19. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):2571–2577. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1852058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P.-Y., Chiu C.-C., Huang S.-Y., Su K.-P. A meta-analytic review of polyunsaturated fatty acid compositions in dementia. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2012;73(09):1245–1254. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P.-Y., Huang S.-Y., Su K.-P. A meta-analytic review of polyunsaturated fatty acid compositions in patients with depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68(2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Wu D., Ni N., Ren H., Luo C., He C., Kang J.X., Wan J.B., Su H. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids protect neural progenitor cells against oxidative injury. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:2341–2356. doi: 10.3390/md12052341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llach C.D., Vieta E. Mind long COVID: Psychiatric sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;49:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Leon S., Wegman-Ostrosky T., Perelman C., Sepulveda R., Rebolledo P.A., Cuapio A., Villapol S. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:16144. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lordan R., Redfern S., Tsoupras A., Zabetakis I. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: are marine phospholipids the answer? Food Funct. 2020;11(4):2861–2885. doi: 10.1039/c9fo01742a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D.-Y., Tsao Y.-Y., Leung Y.-M., Su K.-P. Docosahexaenoic acid suppresses neuroinflammatory responses and induces heme oxygenase-1 expression in BV-2 microglia: implications of antidepressant effects for omega-3 fatty acids. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(11):2238–2248. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C., Ren H., Wan J.-B., Yao X., Zhang X., He C., So K.-F., Kang J.X., Pei Z., Su H. Enriched endogenous omega-3 fatty acids in mice protect against global ischemia injury. J. Lipid Res. 2014;55(7):1288–1297. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M046466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, M.G., De Lorenzo, R., Conte, C., Poletti, S., Vai, B., Bollettini, I., Melloni, E.M.T., Furlan, R., Ciceri, F., Rovere-Querini, P., group, C.-B.O.C.S., Benedetti, F., 2020. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav. Immun. 89, 594-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Messina G., Polito R., Monda V., Cipolloni L., Di Nunno N., Di Mizio G., Murabito P., Carotenuto M., Messina A., Pisanelli D., Valenzano A., Cibelli G., Scarinci A., Monda M., Sessa F. Functional role of dietary intervention to improve the outcome of COVID-19: a hypothesis of work. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(9):3104. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael-Titus A. Omega-3 fatty acids: their neuroprotective and regenerative potential in traumatic neurological injury. Clin. Lipidol. 2009;4(3):343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Morris S.B., Schwartz N.G., Patel P., Abbo L., Beauchamps L., Balan S., Lee E.H., Paneth-Pollak R., Geevarughese A., Lash M.K., Dorsinville M.S., Ballen V., Eiras D.P., Newton-Cheh C., Smith E., Robinson S., Stogsdill P., Lim S., Fox S.E., Richardson G., Hand J., Oliver N.T., Kofman A., Bryant B., Ende Z., Datta D., Belay E., Godfred-Cato S. Case series of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection – United Kingdom and United States, March-August 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2020;69(40):1450–1456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6940e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MRC-04-20-1120, 2020. Omega-3 Oil Use in COVID-19 Patients in Qatar. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04836052.

- Nalbandian A., Sehgal K., Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., McGroder C., Stevens J.S., Cook J.R., Nordvig A.S., Shalev D., Sehrawat T.S., Ahluwalia N., Bikdeli B., Dietz D., Der-Nigoghossian C., Liyanage-Don N., Rosner G.F., Bernstein E.J., Mohan S., Beckley A.A., Seres D.S., Choueiri T.K., Uriel N., Ausiello J.C., Accili D., Freedberg D.E., Baldwin M., Schwartz A., Brodie D., Garcia C.K., Elkind M.S.V., Connors J.M., Bilezikian J.P., Landry D.W., Wan E.Y. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021;27(4):601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalleballe K., Reddy Onteddu S., Sharma R., Dandu V., Brown A., Jasti M., Yadala S., Veerapaneni K., Siddamreddy S., Avula A., Kapoor N., Mudassar K., Kovvuru S. Spectrum of neuropsychiatric manifestations in COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A. Long-Haul COVID. Neurology. 2020;95(13):559–560. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W.H., 2021. COVID-19 clinical management: living guidance.

- Park S.-K., Lee C.-W., Park D.-I., Woo H.-Y., Cheong H.S., Shin H.C., Ahn K., Kwon M.-J., Joo E.-J. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Fecal Samples From Patients With Asymptomatic and Mild COVID-19 in Korea. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;19(7):1387–1394.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Harris W. EPA, but not DHA, decreases mean platelet volume in normal subjects. Lipids. 2002;37(10):941–946. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-0984-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul B.D., Lemle M.D., Komaroff A.L., Snyder S.H. Redox imbalance links COVID-19 and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021:118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024358118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius E., Vlok M., Venter C., Bezuidenhout J.A., Laubscher G.J., Steenkamp J., Kell D.B. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021;20:172. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01359-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao J.S., Ertley R.N., Lee H.-J., DeMar J.C., Arnold J.T., Rapoport S.I., Bazinet R.P. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid deprivation in rats decreases frontal cortex BDNF via a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism. Mol. Psychiatry. 2007;12(1):36–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichard R.R., Kashani K.B., Boire N.A., Constantopoulos E., Guo Y., Lucchinetti C.F. Neuropathology of COVID-19: a spectrum of vascular and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)-like pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02166-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H., Luo C., Feng Y., Yao X., Shi Z., Liang F., Kang J.X., Wan J.B., Pei Z., Su H. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids promote amyloid-beta clearance from the brain through mediating the function of the glymphatic system. FASEB J. 2017;31:282–293. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshi M.L., Su Y.-C., Hong J.-R. RNA viruses: ROS-mediated cell death. In. J. Cell Biol. 2014;2014:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2014/467452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie K., Chan D., Watermeyer T. The cognitive consequences of the COVID-19 epidemic: collateral damage? Brain Commun. 2020;2:fcaa069. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rius B., Lopez-Vicario C., Gonzalez-Periz A., Moran-Salvador E., Garcia-Alonso V., Claria J., Titos E. Resolution of inflammation in obesity-induced liver disease. Front. Immunol. 2012;3:257. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J.G., Ijioma N., Harris W. Omega-3 fatty acids and cognitive function in women. Womens Health (Lond.) 2010;6(1):119–134. doi: 10.2217/whe.09.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogero M., Calder P. Obesity, inflammation, toll-like receptor 4 and fatty acids. Nutrients. 2018;10(4):432. doi: 10.3390/nu10040432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Sánchez C.M., Díaz-Maroto I., Fernández-Díaz E., Sánchez-Larsen Á., Layos-Romero A., García-García J., González E., Redondo-Peñas I., Perona-Moratalla A.B., Del Valle-Pérez J.A., Gracia-Gil J., Rojas-Bartolomé L., Feria-Vilar I., Monteagudo M., Palao M., Palazón-García E., Alcahut-Rodríguez C., Sopelana-Garay D., Moreno Y., Ahmad J., Segura T. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: The ALBACOVID registry. Neurology. 2020;95(8):e1060–e1070. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. As their numbers grow, COVID-19 “long haulers” stump experts. JAMA. 2020;324:1381–1383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan C.N., Arita M., Hong S., Gotlinger K. Resolvins, docosatrienes, and neuroprotectins, novel omega-3-derived mediators, and their endogenous aspirin-triggered epimers. Lipids. 2004;39(11):1125–1132. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan C.N., Chiang N., Van Dyke T.E. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8(5):349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z., Ren H., Luo C., Yao X., Li P., He C., Kang J.-X., Wan J.-B., Yuan T.-F., Su H. Enriched Endogenous Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Protect Cortical Neurons from Experimental Ischemic Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016;53(9):6482–6488. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9554-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siso-Almirall, A., Brito-Zeron, P., Conangla Ferrin, L., Kostov, B., Moragas Moreno, A., Mestres, J., Sellares, J., Galindo, G., Morera, R., Basora, J., Trilla, A., Ramos-Casals, M., On Behalf Of The, C.L.C.-S.G., 2021. Long Covid-19: Proposed Primary Care Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Disease Management. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stefano G.B., Ptacek R., Ptackova H., Martin A., Kream R.M. Selective neuronal mitochondrial targeting in SARS-CoV-2 infection affects cognitive processes to induce 'brain fog' and results in behavioral changes that favor viral survival. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021;27:e930886. doi: 10.12659/MSM.930886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su K.-P., Huang S.-Y., Chiu T.-H., Huang K.-C., Huang C.-L., Chang H.-C., Pariante C.M. Omega-3 fatty acids for major depressive disorder during pregnancy: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):644–651. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su K.-P., Lai H.-C., Yang H.-T., Su W.-P., Peng C.-Y., Chang J.-C., Chang H.-C., Pariante C.M. Omega-3 fatty acids in the prevention of interferon-alpha-induced depression: results from a randomized, controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;76(7):559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su K.P., Tseng P.T., Lin P.Y., Okubo R., Chen T.Y., Chen Y.W., Matsuoka Y.J. Association of use of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids with changes in severity of anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e182327. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.H., Chen Q., Gu H.J., Yang G., Wang Y.X., Huang X.Y., Liu S.S., Zhang N.N., Li X.F., Xiong R., Guo Y., Deng Y.Q., Huang W.J., Liu Q., Liu Q.M., Shen Y.L., Zhou Y., Yang X., Zhao T.Y., Fan C.F., Zhou Y.S., Qin C.F., Wang Y.C. A mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.020. 124-133 e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taquet M., Geddes J.R., Husain M., Luciano S., Harrison P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taquet M., Luciano S., Geddes J.R., Harrison P.J. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:130–140. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USnews.com, 2021. CDC expected to release guidance on identifying, managing long COVID.

- Vibholm L.K., Nielsen S.S.F., Pahus M.H., Frattari G.S., Olesen R., Andersen R., Monrad I., Andersen A.H.F., Thomsen M.M., Konrad C.V., Andersen S.D., Hojen J.F., Gunst J.D., Ostergaard L., Sogaard O.S., Schleimann M.H., Tolstrup M. SARS-CoV-2 persistence is associated with antigen-specific CD8 T-cell responses. EBioMedicine. 2021;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivar-Sierra A., Araiza-Macias M.J., Hernandez-Contreras J.P., Vergara-Castaneda A., Ramirez-Velez G., Pinto-Almazan R., Salazar J.R., Loza-Mejia M.A. In silico study of polyunsaturated fatty acids as potential SARS-CoV-2 spike protein closed conformation stabilizers: epidemiological and computational approaches. Molecules. 2021;26 doi: 10.3390/molecules26030711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Weyhern C.H., Kaufmann I., Neff F., Kremer M. Early evidence of pronounced brain involvement in fatal COVID-19 outcomes. Lancet. 2020;395:e109. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31282-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Kream R.M., Stefano G.B. Long-term respiratory and neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020;26:e928996. doi: 10.12659/MSM.928996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.C., Su K.P., Pariante C.M. The three frontlines against COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021;93:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Huang K., Jiang H., Hua L., Yu W., Ding D., Wang K., Li X., Zou Z., Jin M., Xu S. Long-term existence of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients: host immunity, viral virulence, and transmissibility. Virol Sin. 2020;35:793–802. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00308-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wostyn P. COVID-19 and chronic fatigue syndrome: is the worst yet to come? Med. Hypotheses. 2021;146 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Guo C., Tang L., Hong Z., Zhou J., Dong X., Yin H., Xiao Q., Tang Y., Qu X., Kuang L., Fang X., Mishra N., Lu J., Shan H., Jiang G., Huang X. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5:434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Yang M., Lai C.L. Long COVID-19 syndrome: a comprehensive review of its effect on various organ systems and recommendation on rehabilitation plans. Biomedicines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9080966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong S.J. Persistent brainstem dysfunction in long-COVID: a hypothesis. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021;12:573–580. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan B., Li W., Liu H., Cai X., Song S., Zhao J., Hu X., Li Z., Chen Y., Zhang K., Liu Z., Peng J., Wang C., Wang J., An Y. Correlation between immune response and self-reported depression during convalescence from COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.Z., Chu H., Han S., Shuai H., Deng J., Hu Y.F., Gong H.R., Lee A.C., Zou Z., Yau T., Wu W., Hung I.F., Chan J.F., Yuen K.Y., Huang J.D. SARS-CoV-2 infects human neural progenitor cells and brain organoids. Cell Res. 2020;30:928–931. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0390-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Xu D., Xie B., Zhang Y., Huang H., Liu H., Chen H., Sun Y., Shang Y., Hashimoto K., Yuan S. Poor-sleep is associated with slow recovery from lymphopenia and an increased need for ICU care in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Wang S., Mao L., Leak R.K., Shi Y., Zhang W., Hu X., Sun B., Cao G., Gao Y., Xu Y., Chen J., Zhang F. Omega-3 fatty acids protect the brain against ischemic injury by activating Nrf2 and upregulating heme oxygenase 1. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:1903–1915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4043-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Li P., Hu X., Zhang F., Chen J., Gao Y. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the brain: metabolism and neuroprotection. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2011;16:2653–2670. doi: 10.2741/3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]