Abstract

Background/Aims

The incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is increasing annually. Studies have suggested that psychosocial disorders may be linked to the development of GERD. However, studies evaluating the association between psychosocial disorders and GERD have been inconsistent. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies that evaluated the association between psychosocial disorders and GERD.

Methods

We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases until October 17, 2020. Pooled OR with 95% CI and subgroup analyses were calculated using a random-effects model. Subgroup analyses were performed to identify the sources of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis by one-study removal was used to test the robustness of our results.

Results

This meta-analysis included 1 485 268 participants from 9 studies. Studies using psychosocial disorders as the outcome showed that patients with GERD had a higher incidence of psychosocial disorders compared to that in patients without GERD (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.87-3.54; I2 = 93.8%; P < 0.001). Studies using GERD as an outcome showed an association between psychosocial disorders and an increased risk of GERD (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.42-3.51; I2 = 97.1%; P < 0.001). The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the non-erosive reflux disease group had a higher increased risk of anxiety than erosive reflux disease group (OR, 9.45; 95% CI, 5.54-16.13; I2 = 12.6%; P = 0.285).

Conclusion

Results of our meta-analysis showed that psychosocial disorders are associated with GERD; there is an interaction between the two.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depressive disorder, Gastroesophageal reflux, Meta-analysis, Odds ratio

Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of contemporary societies, people face pressures in all aspects of life. The incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and psychosocial disorders, especially anxiety, and depression, has increased worldwide annually1-5; moreover, GERD and psychosocial disorders often occur together and can affect each other.6-8

GERD is a clinically common gastrointestinal disease in Western countries, affecting up to 20% of the Western population, and is associated with a variety of risk factors such as obesity and smoking.9,10 A meta-analysis reported a global incidence of GERD of 13.98%, with an estimated 1.03 billion people worldwide experiencing GERD.1 GERD mainly refers to the reflux of stomach and duodenum contents to the esophagus, which, in turn, causes acid reflux, heartburn, and other symptoms.11 GERD seriously affects patient quality of life and work efficiency; moreover, long-term burns to the esophagus can also increase the risk of adenocarcinoma of the lower esophagus.11

At present, psychosocial disorders are becoming increasingly common worldwide, especially anxiety and depression.4,5 According to the World Health Organization, depression will become the first global burden of disease by 2030.12 A systematic review collected 87 studies from 44 countries; the final statistics showed that the global prevalence of anxiety disorders was 7.30%.13 Psychological disorders in contemporary societies affects many people and are related to many diseases of the digestive tract, among which irritable bowel syndrome, is the most studied.14-16 Clinical studies have confirmed the association between psychosocial disorders and GERD.17-20 GERD can lead to anxiety and depression, in turn, psychological disorders can also lead to reflux symptoms.21,22 People with depression are 1.7 times more likely to develop GERD compared to those without depression.22 In the study of Kessing et al,23 levels of anxiety can increase the severity of reflux episodes. Treating GERD with antidepressants can improve the symptoms of patients with esophageal visceral allergy.24

GERD and depression have many similar neurobiological mechanisms, among which the “brain-gut” axis plays an important role in the mechanism of the 2 comorbidities.25 The “brain-gut axis” refers to the 2-way communication between the central and the enteric nervous systems.26 Emotional changes, such as anxiety and depression, in GERD may be related to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. GERD includes reflux esophagitis (RE) with mucosal damage and non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) without mucosal damage. Compared to patients with erosive reflux disease (ERD), patients with NERD have a higher prevalence of mental illness.27 Recent studies have suggested that the pathogenesis of erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease is mainly due to excessive acid exposure and subsequent mucosal damage caused by reflux. However, for NERD without mucosal damage under gastroscopy, the pathogenesis is mainly due to psychological stress from esophageal hypersensitivity, epithelial permeability, and dilation of intercellular space causing changes in intercellular pH and/or osmotic pressure, leading to pain.28-32 Studies have shown that the poor efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in patients with GERD may be caused by psychological factors.30

Although studies have explored their correlation, no meta-analysis has shown a causal relationship between psychosocial disorders and GERD. The present study systematically analyzed the association between psychosocial disorders and GERD to provide a deep understanding of the relationship between these 2 diseases to better manage patients in clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

We searched the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases for literature published up to October 17, 2020, using terms in the Medical Subject Headings database, including “depression” OR “anxiety” OR “alexithymia” OR “psychological stress” OR “occupational stress” AND “gastroesophageal reflux disease.”

Protocol and Guidance

This study was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Our inclusion criteria were as follows:

(1) The included studies reported on the association between psychosocial disorders and GERD

(2) Definitely diagnosed as GERD

(3) Diagnosis of psychological disorders based on validated instruments

(4) Observational studies

(5) Research that provided ORs and 95% CIs, or that included data from which OR could be calculated

Our exclusion criteria were as follows:

(1) Reviews, case reports, and letters to the editor

(2) Full text not available

(3) Non-English articles

(4) No control group

Study Selection

Two researchers (M.H. and G.B.) screened the article titles and abstracts, as well as the full texts, selected the studies, and extracted general information on the patients in the studies. Disagreements between the researchers on study inclusion were resolved by a third researcher (D.Y.).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two researchers collected relevant information from each study. The relevant information included the first author and year of publication, country of origin, sample size, study design, age, diagnostic criteria of GERD and psychosocial disorders, and outcome. Two researchers assessed the quality of each study. Cohort and case-control studies were assessed using 3 aspects of the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale: (1) the selection of study groups, (2) comparability of the groups, and (3) ascertainment of exposure or outcome of interest for case-control studies.33 The cross-sectional studies were assessed using an 11-item checklist recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.34

Statistical Methods

Data were analyzed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). ORs and their associated 95% CIs were used to measure the effect size. We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, in which I2 values greater than 50% indicated substantial statistical heterogeneity.35 We used a random-effects model to calculate the pooled effect size. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding 1 study at a time.

Results

Included Studies

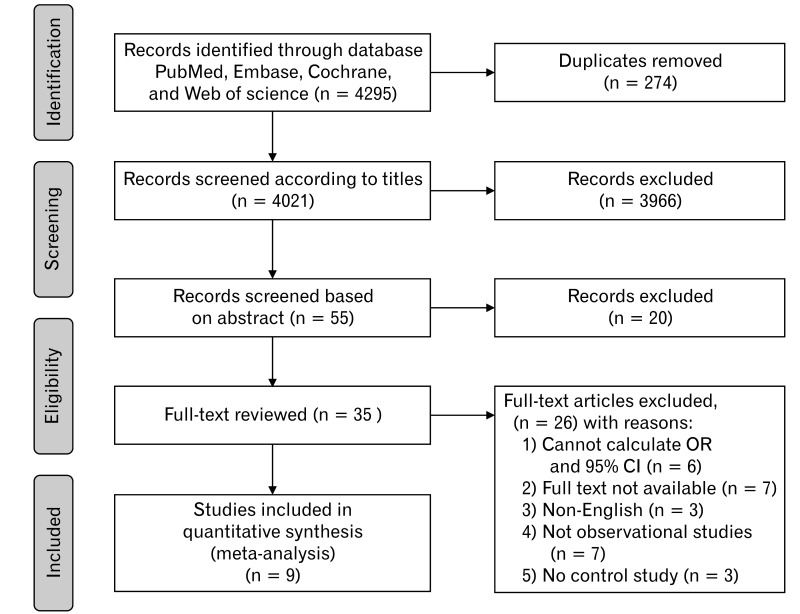

A total of 4295 articles were identified, 4021 of which were included after deduplication. After checking the titles and abstracts, 35 articles were fully reviewed, and 9 articles were finally included (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Characteristics and Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

The baseline information for each study is presented in Table. The 9 articles included a total of 1 485 268 participants. Seven studies showed a higher incidence of psychosocial disorders among patients with GERD, as compared to the healthy control group36-42; 3 studies reported that patients with psychosocial disorders were associated with an increased risk for GERD.39,43,44 Application of the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale method for evaluating article quality showed that the 7 studies had 5 or more stars (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The included cross-sectional studies were assessed using an 11-item checklist (Supplementary Table 3).

Table.

Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Meta-analysis

| First author (yr) | Study design | Ethnicity | Sample size | Age (yr) | GERD diagnosis | Psychosocial disorders diagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al36 (2015) | Case-control | Chinese | GERD (n = 279) | RE (41.07 ± 10.61) | Rome III criteria | ZSASZSDS | Anxiety/depression |

| Healthy controls (n = 100) | NERD (39.68 ± 10.80) | ||||||

| Controls (40.04 ± 12.22) | |||||||

| Javadi and Shafikhani37 (2017) | Case-control | Iranian | GERD (n = 100) | NR | Los Angeles classification | HADS | Anxiety/depression |

| Healthy controls (n = 100) | |||||||

| Denver et al38 (2013) | Case-control | Irish | RO (n = 230) | Controls (63.0) | Savary-Miller classification | 4-item Reed Stress Inventory | Anxiety/depression |

| Controls (n = 260) | RO (61.7) | Hetzel-Dent classification | |||||

| BO (62.4) | Los Angeles classification | ||||||

| Kim et al39 (2018) | Case-control | Korean | Study 1: Depression (n = 60 957) Control (n = 243 828) |

> 20 | ICD-10 codes | ICD-10 codes | Study 1: GERD |

| Study 2 GERD (n = 133 089) Control (n = 266 178) |

Study 2: Depression | ||||||

| Lee et al40 (2018) | Cohort study | Korean | GERD (n = 9503) | > 19 | KCD-6 codes24-hr pH monitoring | KCD-6 codes | Psychological disorders |

| Healthy controls (n = 9503) | |||||||

| On et al41 (2017) | Cohort study | Australian | GERD (n = 221) | 35-80 | GERDQ | Beck Depression Inventory Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale |

Anxiety/depression |

| Healthy controls (n = 1391) | |||||||

| You et al42 (2015) | Cohort study | Chinese | GERD (n = 3813) | GERD (45.9) | ICD-9-CM codes | ICD-9-CM codes | Psychological disorders |

| Healthy controls (n = 15 252) | Control (45.9) | ||||||

| Song et al43 (2013) | Cross-sectional | Korean | Stress group (n = 902) | Stress (42.3 ± 10.5) | Los Angeles classification | BEPSI-K | GERD |

| Reference group (n = 6023) | Control (44.1 ± 9.7) | ||||||

| Chou et al44 (2014) | Cross-sectional | Chinese | General population (n = 728 749) | > 20 | ICD-9-CM codes | ICD-9-CM codes | GERD |

| Patients with MDD (n = 4790) |

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; RE, reflux esophagitis; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease; ZSAS, Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; ZSDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; NR, not reported; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; RO, reflux oesophagitis; BO, Barrett’s esophagus; ICD-10, International Classification of Disease-10; KCD-6, Korean Classification of Diseases, sixth revision; GERDQ, gastroesophageal reflux disease; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification; BEPSI-K, Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Psychosocial Disorders and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

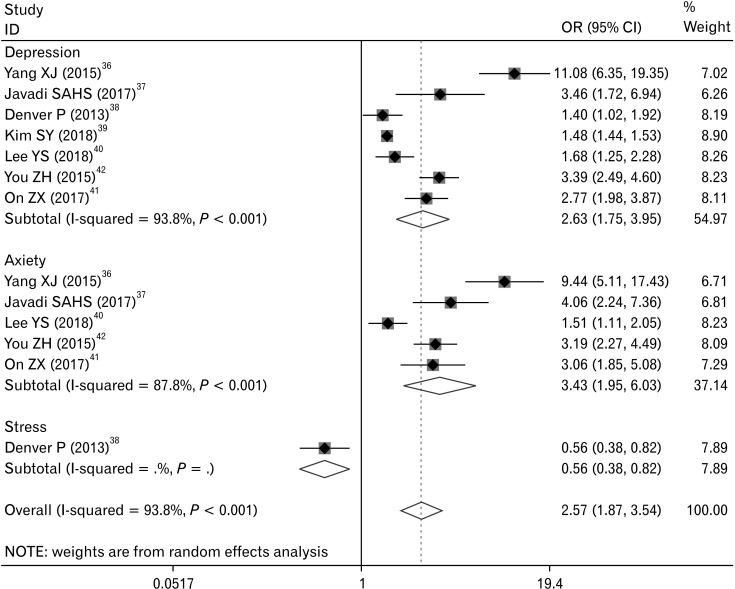

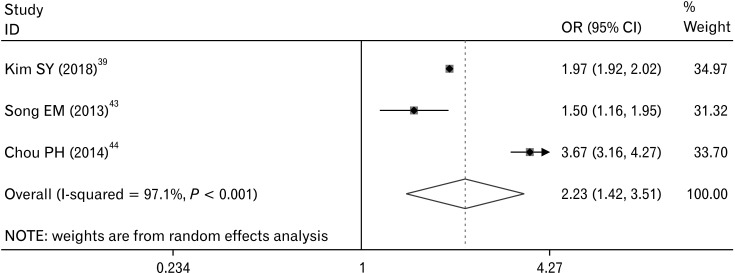

The 7 studies using psychosocial disorders as the outcome showed a higher incidence of psychosocial disorders in patients with GERD than that in patients without GERD (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.87-3.54; I2 = 93.8%; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The other 3 studies using GERD as an outcome showed that psychosocial disorders were associated with an increased risk of GERD (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.42-3.51; I2 = 97.1%; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the associations between gastroesophageal reflux disease and psychosocial disorders.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the associations between psychosocial disorders and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Subgroup Analysis

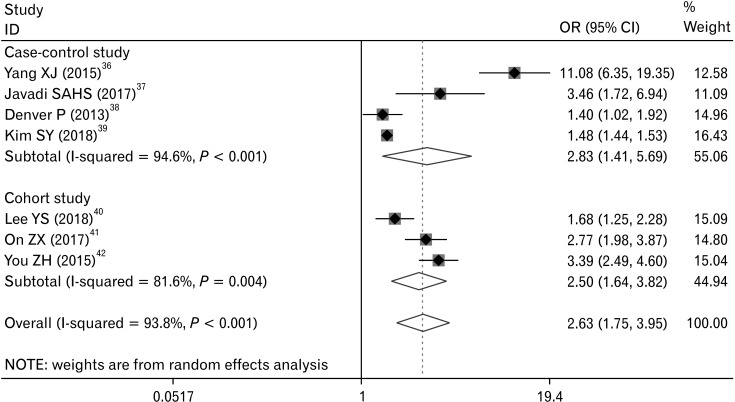

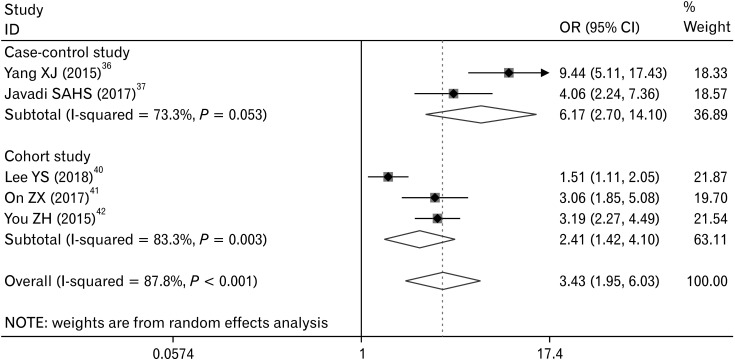

First, a subgroup analysis was conducted according to the types of study. In the subgroup analysis exploring the association between GERD and depression (Fig. 4), the results showed OR, 2.83 (95% CI, 1.41-5.69; I2 = 94.6%; P < 0.001) for case-control studies and OR, 2.50 (95% CI, 1.64-3.82; I2 = 81.6%; P = 0.004) for cohort studies. In the subgroup analysis exploring the association between GERD and anxiety (Fig. 5), the results showed OR, 6.17 (95% CI, 2.70-14.10; I2 = 73.3%; P = 0.053) for case-control studies, and OR, 2.41 (95% CI, 1.42-4.10; I2 = 83.3%; P = 0.003) for cohort studies. The results indicated that the heterogeneity was not attributed to the types of study.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of the associations between gastroesophageal reflux disease and depression according to the study type.

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis of the associations between gastroesophageal reflux disease and anxiety according to study type.

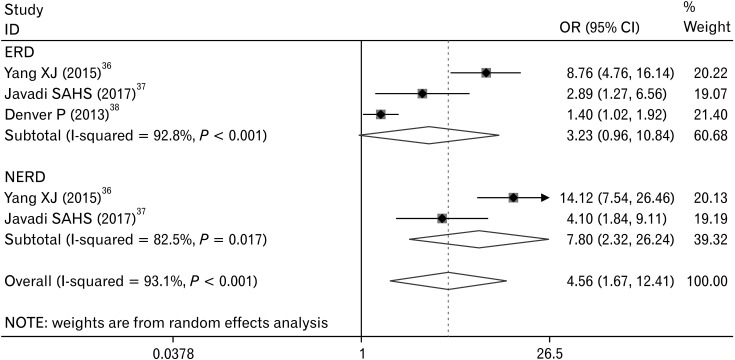

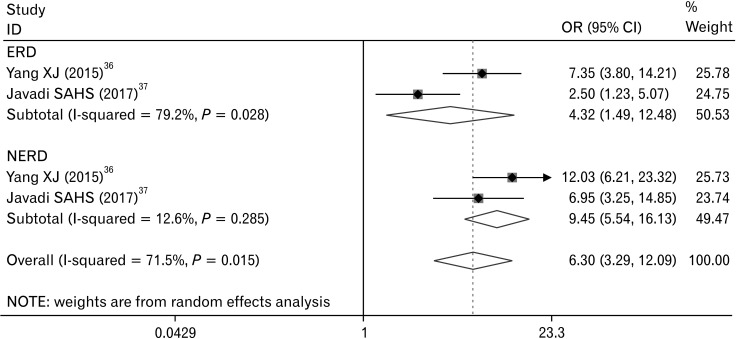

Next, we conducted a subgroup analysis according to the different types of GERD. Although individual studies showed an increased risk for depression in those with depression outcomes (Fig. 6), the combined study did not have any statistical significance (OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 0.96-10.84; I2 = 92.8%; P < 0.001). Compared to the health control group, the NERD group had a higher risk for depression (OR, 7.80; 95% CI, 2.32-26.24; I2 = 82.5%; P = 0.017). In studies with anxiety outcomes (Fig. 7), ERD increased the risk for anxiety, as compared with healthy controls (OR, 4.32; 95% CI, 1.49-12.48; I2 = 79.2%; P = 0.028). The NERD group had a higher increased risk for anxiety (OR, 9.45; 95% CI, 5.54-16.13; I2 = 12.6%; P = 0.285); the NERD group was more homogeneous.

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis of the associations between gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and depression according to the GERD type. ERD, erosive reflux disease; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease.

Figure 7.

Subgroup analysis of the associations between gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and anxiety according to GERD type. ERD, erosive reflux disease; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease.

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was carried out in which 1 study was sequentially omitted to assess the robustness of the pooled effects. After item-by-item elimination, the sensitivity analysis results show that the stability is good. The pooled ORs of the association between GERD and depression ranged from 2.10 (95% CI, 1.52-2.90) to 2.97 (95% CI, 1.81-4.87) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The pooled OR of the association between GERD and anxiety ranged from 2.69 (95% CI, 1.68-4.31) to 4.23 (95% CI, 2.67-6.72) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the association between psychosocial disorders and GERD. Overall, this meta-analysis based on 9 studies and 1 485 268 subjects found a significant positive association between psychosocial disorders and GERD. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the association between psychosocial disorders and GERD.

Previous studies have reported the relationships between psychosocial disorders and GERD. According to a cross-sectional study, the levels of depression and anxiety were significantly higher in the subjects with GERD, especially NERD, than in controls.45 Lee et al40 reported that patients with GERD had higher risks of psychological disorders than those without GERD (hazard ratio = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.07-1.47; P = 0.006).40 Jansson et al22 indicated that anxiety increased risk of reflux symptoms compared to the subjects without reflux symptoms (OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 2.7-3.8; P < 0.0001), and that depression led to a 1.7-fold increase of risk (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4-2.1; P < 0.0001).22 Despite many clinical studies demonstrating the association between GERD and mental illness, the sample size of individual studies was small, which can lead to the biased results. In this regard, meta-analysis methods can be used to increase sample size, reduce bias, and improve the level of evidence.

This meta-analysis of 9 observational studies provided evidence of an increased OR for GERD of 2.57 with the occurrence of psychosocial disorders (95% CI, 1.87-3.54). Individuals with GERD had a 2.63-fold higher risk of depression (OR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.75-3.95) and a 3.43-fold higher risk of anxiety (OR, 3.43; 95% CI, 1.95-6.03). This result proved that patients with GERD are more likely to experience anxiety than depression. In addition, individuals with psychosocial disorders had a 2.23-fold increased occurrence of GERD (95% CI, 1.42-3.51).

Due to the high heterogeneity of mergers, we further performed subgroup analysis and sensitivity analyses. The subgroup analysis showed that the risk for anxiety in NERD patients was significantly higher than that in ERD patients. In the sensitivity analysis, we found that the removal of Yang et al36 had a greater impact on the results. In this study, patients with NERD had significantly higher anxiety and depression scores than patients with ERD. These results indicated that NERD and ERD may have different pathogeneses.

We identified several possible explanations for the increased risk of psychosocial disorders caused by GERD. First, acid reflux events disrupts sleep architecture. More than half of patients with chronic GERD report nocturnal symptoms, which seriously affect rest and increase anxiety and tension.46,47 Second, the abnormal expression of inflammatory cytokines in the esophageal mucosa, such as interleukin IL-6, IL-8, IL-1beta, interferon-gamma, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) may also play a role.48 The mucosal barrier is damaged by the mediation of inflammatory chemokines, which, in turn, sensitizes nerve endings in the submucosa of the esophagus. Abnormal expression of inflammatory factors in the body is an important factor in the progression of RE. The more severe the illness, the stronger the inflammatory response.49 The occurrence of peripheral inflammation affects inflammation of the central nervous system (CNS)50; moreover, central inflammation can lead to mental illness.51

Psychosocial disorders may also increase the risk of developing GERD. Psychological disorders can regulate the sensation of esophageal pain. These factors often cause patients to feel hypersensitivity to internal organs; that is, pain sensation in response to stimulation below the threshold.17 The specific mechanisms are as follows. First, the tight junctions of the esophageal epithelium of psychologically stressed rats are destroyed, thereby weakening or reducing the barrier function of the esophageal mucosa.52 Second, mental states such as anxiety may impair esophageal motor function and cause esophageal motility disorders by reducing the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter.53 Third, psychological disorders can affect esophageal sensitivity through peripheral and central mechanisms; that is, peripheral sensitization and central sensitization. Central sensitization also plays a vital role in esophageal visceral hypersensitivity. Mechanical and chemical stimulation are converted into action potentials through the nociceptive receptors on the esophageal nerve and then transmitted to the CNS through the spinal or vagus nerves, causing excitatory synaptic responses that, in turn, amplify the patient’s sensitivity to physiological stimuli. When injured, central overexcitation persists when the stimulation is removed. This is because the nerve center has a high degree of plasticity during visceral pain, leading to continuous pain.54 Acid exposure in patients with GERD causes faster and greater brain activity compared to that in healthy controls.55 Fourth, psychological disorders increase the esophageal mucosal perception of stimuli in the esophagus through the interaction of the brain-gut axis, leading to small stimuli that can also cause pain and heartburn.52,56 In addition, stress can promote inflammation and increase the occurrence of reflux symptoms. Animal experiments have shown that 2 weeks of binding stress significantly increased the levels of inflammatory cytokines in the esophagus and plasma, including IL-6, IL-8, interferon, and TNF-α, indicating that stress can induce inflammation of the esophagus.57

This study had several limitations. First, it was difficult to address heterogeneity. Although subgroup analysis reduced this heterogeneity, it remained high. This may be due to the region or the number of people studied. Second, because of the small number of included studies, publication bias was not tested. Third, the included studies have different diagnostic criteria for GERD and psychosocial disorders, which can lead to bias. Fourth, the present study focused on GERD and psychosocial disorders. Additional studies are needed to analyze the relationships between RE, NERD, and psychosocial stress based on the classification of GERD.

In conclusion, the results of our meta-analysis showed a significant positive association between psychosocial disorders and GERD. GERD patients are more likely to develop psychosocial disorders than healthy people; at the same time, psychosocial disorders can also increase the risk of GERD. There was a positive interaction between the 2 variables. Therefore, we suggest that gastroenterologists and psychologists should pay attention to assess whether patients have both GERD and psychosocial disorders. If the 2 coexist, treatment should be considered at the same time in order to achieve a better outcome.

Supplementary Materials

Note: To access the supplementary tables and figures mentioned in this article, visit the online version of Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility at http://www.jnmjournal.org/, and at https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm21044.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Zhu Changtai, Dr Wang Zhe, and Dr Gong Ziqi for their generous help.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by the study on the Living Inheritance of Shengjing Spleen and Stomach Academic School (No. LiaoWeiZongHeZi[2021]19).

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Guang Bai conceived the research design and obtained the funding; Meijun He and Qun Wang collected the data; Meijun He drafted the manuscript; Da Yao, Qun Wang, and Jing Li analyzed and interpreted the data; and Jing Li revised the paper for important content. All authors approved the final paper.

References

- 1.Nirwan JS, Hasan SS, Babar ZU, Conway BR, Ghori MU. Global prevalence and risk factors of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD): systematic review with meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5814. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62795-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari AJ, Somerville AJ, Baxter AJ, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Psychol Med. 2013;43:471–481. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreescu C, Lee S. Anxiety disorders in the elderly. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:561–576. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the international consortium of psychiatric epidemiology (ICPE) surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12:3–21. doi: 10.1002/mpr.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hou Z, Jiang W, Yin Y, Zhang Z, Yuan Y. The current situation on major depressive disorder in China: research on mechanisms and clinical practice. Neurosci Bull. 2016;32:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0037-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SE, Kim N, Oh S, et al. Predictive factors of response to proton pump inhibitors in korean patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21:69–77. doi: 10.5056/jnm14078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro M, Simantov R, Yair M, et al. Comparison of central and intraesophageal factors between gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients and those with GERD-related noncardiac chest pain. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:702–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng Y, Kou F, Liu J, Dai Y, Li X, Li J. Systematic assessment of environmental factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:566–573. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R Global consensus group, author. The montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rehm J, Shield KD. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:10. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2013;43:897–910. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200147X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stasi C, Caserta A, Nisita C, et al. The complex interplay between gastrointestinal and psychiatric symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a longitudinal assessment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:713–719. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin HY, Cheng CW, Tang XD, Bian ZX. Impact of psychological stress on irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14126–14131. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wouters MM, Boeckxstaens GE. Is there a causal link between psychological disorders and functional gastrointestinal disorders? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10:5–8. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2016.1109446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamolz T, Velanovich V. Psychological and emotional aspects of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:199–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2002.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu JC, Mak AD, Chan Y, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is strongly associated with psychological disorders in the general population: a community-based study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S–725. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(11)63011-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley LA, Richter JE, Pulliam TJ, et al. The relationship between stress and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux: the influence of psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Giblovich H, Sontag SJ. Reflux symptoms are associated with psychiatric disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1907–1912. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh JH, Kim TS, Choi MG, et al. Relationship between psychological factors and quality of life in subtypes of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gut Liver. 2009;3:259–265. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Wallander MA, et al. Severe gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in relation to anxiety, depression and coping in a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:683–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessing BF, Bredenoord AJ, Saleh CM, Smout AJ. Effects of anxiety and depression in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1089–1095. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weijenborg PW, de Schepper HS, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Effects of antidepressants in patients with functional esophageal disorders or gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:251–259. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanger GJ, Lee K. Hormones of the gut-brain axis as targets for the treatment of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:241–254. doi: 10.1038/nrd2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anadure RK, Shankar S, Prasad AS. The gut-brain axis. Medicine Update. 2019 doi: 10.1016/c2014-0-02907-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ang TL, Fock KM, Ng TM, Teo EK, Chua TS, Tan J. A comparison of the clinical, demographic and psychiatric profiles among patients with erosive and non-erosive reflux disease in a multi-ethnic Asian country. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3558–3561. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i23.3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhong C, Liu K, Wang K, et al. Developing a diagnostic understanding of GERD phenotypes through the analysis of levels of mucosal injury, immune activation, and psychological comorbidity. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31:doy039. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Söderholm JD. Stress-related changes in oesophageal permeability: filling the gaps of GORD? Gut. 2007;56:1177–1180. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.120691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nojkov B, Rubenstein JH, Adlis SA, et al. The influence of co-morbid IBS and psychological distress on outcomes and quality of life following PPI therapy in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:473–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trimble KC, Pryde A, Heading RC. Lowered oesophageal sensory thresholds in patients with symptomatic but not excess gastro-oesophageal reflux: evidence for a spectrum of visceral sensitivity in GORD. Gut. 1995;37:7–12. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Miwa H, Pandolfino JE, Zerbib F. Section II: FGIDs: disagnostic groups. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1368–1379. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the newcastle-ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melsen WG, Bootsma MC, Rovers MM, Bonten MJ. The effects of clinical and statistical heterogeneity on the predictive values of results from meta-analyses. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:123–129. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang XJ, Jiang HM, Hou XH, Song J. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and their effect on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4302–4309. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Javadi SAHS, Shafikhani AA. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disorder. Electron Physician. 2017;9:5107–5112. doi: 10.19082/5107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denver P, Donnelly M, Murray LJ, Anderson LA. Psychosocial factors and their association with reflux oesophagitis, barrett's oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1770–1777. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SY, Kim HJ, Lim H, Kong IG, Kim M, Choi HG. Bidirectional association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and depression: two different nested case-control studies using a national sample cohort. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11748. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29629-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee YS, Jang BH, Ko SG, Chae Y. Comorbid risks of psychological disorders and gastroesophageal reflux disorder using the national health insurance service-national sample cohort: a STROBE-compliant article. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0153. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.On ZX, Grant J, Shi Z, et al. The association between gastroesophageal reflux disease with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in a cohort study of Australian men. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1170–1177. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.You ZH, Perng CL, Hu LY, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders following gastroesophageal reflux disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song EM, Jung HK, Jung JM. The association between reflux esophagitis and psychosocial stress. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:471–477. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2377-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chou PH, Lin CC, Lin CH, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in major depressive disorder: a population-based study. Psychosomatics. 2014;55:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi JM, Yang JI, Kang SJ, et al. Association between anxiety and depression and gastroesophageal reflux disease: results from a large cross-sectional study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:593–602. doi: 10.5056/jnm18069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerson LB, Fass R. A systematic review of the definitions, prevalence, and response to treatment of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harding SM. Sleep-related gastroesophageal reflux: evidence is mounting. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:919–920. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altomare A, Guarino MP, Cocca S, Emerenziani S, Cicala M. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: update on inflammation and symptom perception. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6523–6528. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Li G, Wang X, Zhu S. Effects of shugan hewei granule on depressive behavior and protein expression related to visceral sensitivity in a rat model of nonerosive reflux disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:1505693. doi: 10.1155/2019/1505693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lampa J, Westman M, Kadetoff D, et al. Peripheral inflammatory disease associated with centrally activated IL-1 system in humans and mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12728–12733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118748109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kivimäki M, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, et al. Long-term inflammation increases risk of common mental disorder: a cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:149–150. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farré R, De Vos R, Geboes K, et al. Critical role of stress in increased oesophageal mucosa permeability and dilated intercellular spaces. Gut. 2007;56:1191–1197. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.113688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richter JE, Bradley LC. Psychophysiological interactions in esophageal diseases. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1996;7:169–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Louwies T, Ligon CO, Johnson AC, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Targeting epigenetic mechanisms for chronic visceral pain: a valid approach for the development of novel therapeutics. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31:e13500. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herregods TV, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJ. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: new understanding in a new era. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1202–1213. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fass R, Tougas G. Functional heartburn: the stimulus, the pain, and the brain. Gut. 2002;51:885–892. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wulamu W, Yisireyili M, Aili A, et al. Chronic stress augments esophageal inflammation, and alters the expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 and protease activated receptor 2 in a murine model. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19:5386–5396. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.